User login

Evaluation of a Stress, Coping, and Resourcefulness Program for VA Nurses During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Nurses are recognized among the most trusted professions in the United States.1 Since the time of Florence Nightingale, nurses have been challenged to provide care to patients and soldiers with complex needs, including acute and chronic physical illness, as well as mental health issues. Nurses have traditionally met those challenges with perseverance and creativity but have also experienced stress and burnout.

A shortage of nurses has been linked to many interrelated factors including the retirement of bedside caregivers and educators, diverse care settings, expanding roles for nurses, and nurse burnout.2-4 Therefore, there is a critical need to better understand of how nurses can be supported while they care for patients, cope with stress, and maintain positive personal and professional outcomes. The objective of this pilot project was to assess US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) nurses’ levels of burnout and test an intervention to enhance resourcefulness skills during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background

Stress has many definitions. Hans Selye described it as a biological response of the body to any demand.5,6 Occupational stress is a process that occurs in which work environment stressors result in the development of psychological, behavioral, or physiological effects that can contribute to health.6 Occupational stress has been observed as prevalent among nurses.6 In 1960, Menzies identified sources of stress among nurses that include complex decision-making within a dynamic environment.7 Since the mid-1980s, nurses’ stress at work has increased because of legal, accreditation, ethical issues, fiscal pressures, staffing shortages, and the increasing integration of technology associated with clinical care.8

Sustained stress can lead to emotional exhaustion or burnout, which has been associated with nursing turnover, lower patient satisfaction, and patient safety risk.2,9 An American Nurses Foundation survey reported that 51% of US nurses feel exhausted, 43% overwhelmed, and 36% anxious; 28% express willingness to leave the profession.2 Burnout has been described as a response to physical or emotional stress leading to exhaustion, self-doubt, cynicism, and ineffectiveness.10 Employees with burnout are more likely to leave their jobs, take sick leave, and suffer from depression and relationship problems, and it affects nearly half of all US nurses, especially among critical care, pediatric, and oncology specialities.10,11 It has been well documented that unmitigated stress can lead to burnout and contribute to nurses leaving bedside care and the health care profession.2,3 Several studies on nursing stress and burnout have focused on its prevalence and negative outcomes.4,7,9 However, few studies have addressed building resiliency and resourcefulness for nurses.10,12,13

A 2021 National Academy of Medicine report advocated a multilevel approach to managing burnout and building resiliency among nurses.14 Taylor further identified specific interventions, ranging from primary prevention to treatment.15 Primary prevention could include educating nurses on self-awareness, coping strategies, and communication skills. Screening for burnout and providing resources for support would be a secondary level of intervention. For nurses who experienced severe burnout symptoms and left the workplace, strategies are sorely needed to provide healing and a return-to-work plan.15 This may include adjusting nurse schedules and nursing roles (such as admitting/discharge nurse or resource nurse).

RESILIENCY AND RESOURCEFULNESS

Rushton and colleagues describe resiliency as the “ability to face adverse situations, remain focused, and continue to be optimistic for the future.”4 For nurses in complex health care systems, resiliency is associated with reduced turnover and symptoms of burnout and improved mental health. Humans are thought to have an innate resiliency potential that evolves over time and fluctuates depending on the context (eg, societal conditions, moral/ethical values, commitments).4 It is believed that resiliency can contribute to the development of new neuropathways that can be used to manage and cope with stress, prevent burnout, and improve quality of life. However, it appears these adaptations are individualized and contingent on situations, available resources, and changing priorities.16 Consequently, resiliency may be an essential tool for nurses to combat burnout in today’s complex health care systems.17

Although resilience and resourcefulness are conceptually related, each has distinctive features.18 Celinski frames resilience as transcendence and resourcefulness as transformation.19 Thus, while resilience suggests transcendence in terms of rising above, going beyond, exceeding, or excelling; resourcefulness reflects transformation, such as making changes in thoughts, feelings, behaviors, actions, or reactions. Resourcefulness has been conceptualized as an indicator of resilience.18

Resourcefulness comprises 2 dimensions, including the use of self-help strategies (personal resourcefulness) and seeking help from others (social resourcefulness), to self-regulate one’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to cope with high levels of stress, anxiety, or depression.18,20,21 Personal resourcefulness skills include the use of cognitive reframing, positive thinking, problem-solving, priority-setting, and planning ahead. Social resourcefulness involves actively seeking help from others. Formal sources of help include, but are not limited to, nursing and medical care practitioners and community organizations such as hospitals and clinics. Informal sources of help include family members, friends, peers, and coworkers.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses were especially challenged to provide support for each other because of limited nursing staff and treatment options, increased complex patient assignments, shortages of supplies, and reduced support services. Many nurses, however, were able to find innovative, peer-supported strategies for coping.13 Nurses’ use of resourcefulness skills is believed to be indicative of their resilience. This pilot project aimed to identify and evaluate some of these strategies and resourcefulness skills.

INTERVENTION

This pilot study among VA Northeast Ohio Health Care System (VANEOHS) nurses was designed to assess nursing burnout and resourcefulness during the pandemic. Those who agreed to participate completed a baseline survey on burnout and resourcefulness. Participants agreed to review a training video on resourcefulness skills (eg, relying on and exchanging ideas with others, and reframing and using ‘positive self-talk’). They were encouraged to document their experience with familiar and new resourcefulness skills. Weekly reminders (eg, emails and phone messages) reminded and coached participants in their journey.

The study identified and implemented an existing Resourcefulness Training (RT) intervention, which was developed for informal family caregivers and found to be effective.22 We measured burnout and resourcefulness preintervention and postintervention.23 This survey and educational intervention were reviewed by the VANEOHS institutional review board and ruled exempt. The survey also gathered information on nurses' contact with individuals infected with COVID-19.

Despite the many staffing and resource challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, a convenience sample of 12 nurses was recruited from nursing committees that continued to have scheduled meetings. These meetings allowed time to answer questions and provide information about the study. The majority of nurses queried declined to participate, citing no time, interest, or burnout. Participants completed a baseline survey, reviewed a 30-minute RT video, and tracked their experience for 28 days. Participants completed postintervention surveys 6 weeks after the video. Details of the survey and measures can be found in previous studies.20,21

RT is an online cognitive-behavioral intervention that teaches and reinforces personal (self-help) and social (help-seeking) resourcefulness skills that have not yet been tested in nurses or other health care professionals.22,24 The training included social resourcefulness (eg, from family, friends, others, and professionals) and personal resourcefulness (eg, problem-solving, positive thinking, self-control, organization skills). Participants were encouraged to review the videos as often as they preferred during these 4 weeks.

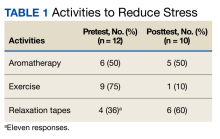

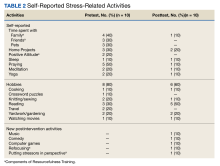

All 12 survey respondents were female and had received COVID-19 vaccinations according to the federal policy at the time of data collection. The number of patients cared for with COVID-19 infections varied widely (range, 1-1000). The baseline burnout score ranged from 1 (no burnout) to 3 (1 symptom of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion), with a mean score of 2.2. In the follow-up survey, the mean score was 2.0. At baseline, participants reported a variety of activities to manage stress and burnout, including times with friends and family, engaging in hobbies, and prayer. Postintervention, some participants mentioned using skills learned from RT, including reframing the situation positively by refocusing and putting stressors in perspective (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Recent American Nurses Association efforts to develop organizational and professional goals include the importance of nurses to recognize and manage stress to prevent burnout.25 The American Nurses Association Code of Ethics notes that nurses have the same duties to care for themselves as they do for others.25 Nurses have demonstrated the ability to adapt and remain resilient during stressful times. VA nurses are a resourceful group. Many used resourcefulness skills to manage stress and burnout even before the pandemic. For example, nurses identified using family/friends for support and validation, as well as prayer and meditation. Some of the new activities may have been influenced/inspired by RT, such as organizing schedules for problem-solving and distraction.

Relying on family and peers emerged as an essential resourcefulness skill. Support from peers—battle buddies—has been recognized as a key strategy among combat soldiers. A battle buddy is paired with a fellow soldier for support to keep each other informed about key instructions and information. This promotes cooperative problem-solving. Outcomes associated with battle buddies include increased morale and confidence, and decreased stress.25 Over time, it is hoped that these coaching/mentoring relationships will result in enhanced leadership skills. Battle buddy strategies are currently being adapted into health care environments.12,26 Such programs need to be further evaluated and information disseminated.

Findings from this pilot program support the use of interventions such as RT to decrease burnout among nurses. This study suggests that RT should be tested in a larger more representative sample to determine efficacy.

Limitations

This pilot study was limited by its small sample size, single facility, and female-only participants; the findings are not generalizable. Nurses were recruited from VA nursing committees and may not be representative of nurses in the general population. In addition, the RT intervention may require a longer time commitment to adequately determine efficacy. Another limitation was that personal or family exposure to COVID-19 was not measured, but may be a confounding variable. An additional limitation may have been the time interval. A baseline survey was completed prior to watching the teaching video. Daily logs were to be completed for 28 days. A post survey followed at 6 weeks. It is possible that there was insufficient time for the nurses to have the opportunity to use their resourcefulness skills within the short time frame of the study. While it supports the need for further studies, findings should be interpreted cautiously and not generalized. It may be premature based on these findings to conclude that the intervention will be effective for other populations. Further studies are needed to assess nurses’ preferences for healthy coping mechanisms, including RT.

Conclusions

As the nursing shortage continues, efforts to support diverse, innovative coping strategies remain a priority postpandemic. Nurses must be vigilant in appraising and managing their ability to cope and adapt to individual stress, while also being aware of the stress their colleagues are experiencing. Educational institutions, professional organizations, and health care facilities must strive to educate and support nurses to identify not only stress, but healthy coping mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office rapid response COVID-19 funding initiative, the Veteran Affairs Northeast Ohio Health Care System, and Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC). The Resourcefulness Scale, Resourcefulness Skills Scale, and the Resourcefulness Training intervention are copyrighted and were used with permission of the copyright holder, Jaclene A. Zauszniewski, PhD, RN-BC.

1. Walker A. Nursing ranked as the most trusted profession for 22nd year in a row. January 23, 2024. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://nurse.org/articles/nursing-ranked-most-honest-profession

2. Mental health and wellness survey 1. American Nurses Foundation. August 2020. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/mental-health-and-wellbeing-survey/

3. Healthy nurse, healthy nation. American Nurses Association. May 1, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://www.healthynursehealthynation.org/

4. Rushton CH, Batcheller J, Schroeder K, Donohue P. Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high-intensity settings. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(5):412-420. doi:10.4037/ajcc2015291

5. Selye HA. History and general outline of the stress concept. Stress in Health and Disease. Butterworths; 1976:3-34.

6. Levy BS, Wegman DH, Baron SL, Sokas RK. Recognizing and preventing occupational and environmental disease and injury. Occupational and Environmental Health: Recognizing and Preventing Disease and Injury. 6th ed. Oxford University Press; 2011:59-77.

7. Menzies IEP. Nurses under stress. Int Nurs Rev. 1960;7:9-16.

8. Jennings BM. Turbulence. In: Hughes RG, ed. Advances in Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. 3rd ed. AHRQ Publication; 2007;2;193-202.

9. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987-1993. doi:10.1001/jama.288.16.1987

10. Magtibay DL, Chesak SS, Coughlin K, Sood A. Decreasing stress and burnout in nurses: efficacy of blended learning with stress management and resilience training program. J Nurs Adm. 2017;47(7-8):391-395. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000501

11. Halbesleben JR, Wakefield BJ, Wakefield DS, Cooper LB. Nurse burnout and patient safety outcomes: nurse safety perception versus reporting behavior. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30(5):560-577. doi:10.1177/0193945907311322

12. Sherman RO. Creating a Battle Buddy program. September 2, 2021. Accessed September 27, 2022. https://www.emergingrnleader.com/creating-a-battle-buddy-program

13. Godfrey KM, Scott SD. At the heart of the pandemic: nursing peer support. Nurse Leader. 2021:19(2),188-193. doi:10.1016/j.mnl.2020.09.006

14. Wakefield M, Williams DR, Le Menestrel S, and Flaubert JL, Editors; Committee on the future of nursing 2020 2030; National Academy of Medicine; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Institute of Medicine 2008. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/12089

15. Taylor RA. Contemporary issues: resilience training alone is an incomplete intervention. Nurs Educ Today. 2019;78:10-13. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2019.03.014

16. Hofmann SG, Gómez AF. Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):739-749. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.008

17. Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:598-611. doi:10.1192/bjp.147.6.598

18. Zauszniewski JA, Bekhet AK, Suresky MJ. Indicators of resilience in family members of persons with serious mental Illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2015;38(1):131-146. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2014.11.009

19. Celinski MJ. Framing resilience as transcendence and resourcefulness as transformation. In: Celinski MJ, Gow KM, eds. Continuity Versus Creative Response to Challenge: The Primacy of Resilience and Resourcefulness in Life and Therapy. Nova Science Pub Inc; 2011:11-30.

20. Zauszniewski JA, Lai CY, Tithiphontumrong S. Development and testing of the Resourcefulness Scale for Older Adults. J Nurs Meas. 2006:14(1):57-68. doi:10.1891.jnum.14.1.57

21. Zauszniewski JA, Bekhet AK. Measuring use of resourcefulness skills: psychometric testing of a new scale. ISRN Nurs. 2011;2011:787363. doi:10.5402/2011/787363

22. Zauszniewski JA, Lekhak N, Burant CJ, Variath M, Morris DL. preliminary evidence for effectiveness of resourcefulness training for women dementia caregivers. J Fam Med. 2016:3(5):1069.

23. Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):582-587. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3112-6

24. Zauszniewski JA Resourcefulness. In: Fitzpatrick JJ, ed. Encyclopedia of Nursing Research. 4th ed. 2018:632-634.

25. Combating Stress. American Nurses Association. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/combating-stress/

26. Albott CS, Wozniak JR, McGlinch BP, Wall MH, Gold BS, Vinogradov S. Battle Buddies: Rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(1):43-54. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912

Nurses are recognized among the most trusted professions in the United States.1 Since the time of Florence Nightingale, nurses have been challenged to provide care to patients and soldiers with complex needs, including acute and chronic physical illness, as well as mental health issues. Nurses have traditionally met those challenges with perseverance and creativity but have also experienced stress and burnout.

A shortage of nurses has been linked to many interrelated factors including the retirement of bedside caregivers and educators, diverse care settings, expanding roles for nurses, and nurse burnout.2-4 Therefore, there is a critical need to better understand of how nurses can be supported while they care for patients, cope with stress, and maintain positive personal and professional outcomes. The objective of this pilot project was to assess US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) nurses’ levels of burnout and test an intervention to enhance resourcefulness skills during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background

Stress has many definitions. Hans Selye described it as a biological response of the body to any demand.5,6 Occupational stress is a process that occurs in which work environment stressors result in the development of psychological, behavioral, or physiological effects that can contribute to health.6 Occupational stress has been observed as prevalent among nurses.6 In 1960, Menzies identified sources of stress among nurses that include complex decision-making within a dynamic environment.7 Since the mid-1980s, nurses’ stress at work has increased because of legal, accreditation, ethical issues, fiscal pressures, staffing shortages, and the increasing integration of technology associated with clinical care.8

Sustained stress can lead to emotional exhaustion or burnout, which has been associated with nursing turnover, lower patient satisfaction, and patient safety risk.2,9 An American Nurses Foundation survey reported that 51% of US nurses feel exhausted, 43% overwhelmed, and 36% anxious; 28% express willingness to leave the profession.2 Burnout has been described as a response to physical or emotional stress leading to exhaustion, self-doubt, cynicism, and ineffectiveness.10 Employees with burnout are more likely to leave their jobs, take sick leave, and suffer from depression and relationship problems, and it affects nearly half of all US nurses, especially among critical care, pediatric, and oncology specialities.10,11 It has been well documented that unmitigated stress can lead to burnout and contribute to nurses leaving bedside care and the health care profession.2,3 Several studies on nursing stress and burnout have focused on its prevalence and negative outcomes.4,7,9 However, few studies have addressed building resiliency and resourcefulness for nurses.10,12,13

A 2021 National Academy of Medicine report advocated a multilevel approach to managing burnout and building resiliency among nurses.14 Taylor further identified specific interventions, ranging from primary prevention to treatment.15 Primary prevention could include educating nurses on self-awareness, coping strategies, and communication skills. Screening for burnout and providing resources for support would be a secondary level of intervention. For nurses who experienced severe burnout symptoms and left the workplace, strategies are sorely needed to provide healing and a return-to-work plan.15 This may include adjusting nurse schedules and nursing roles (such as admitting/discharge nurse or resource nurse).

RESILIENCY AND RESOURCEFULNESS

Rushton and colleagues describe resiliency as the “ability to face adverse situations, remain focused, and continue to be optimistic for the future.”4 For nurses in complex health care systems, resiliency is associated with reduced turnover and symptoms of burnout and improved mental health. Humans are thought to have an innate resiliency potential that evolves over time and fluctuates depending on the context (eg, societal conditions, moral/ethical values, commitments).4 It is believed that resiliency can contribute to the development of new neuropathways that can be used to manage and cope with stress, prevent burnout, and improve quality of life. However, it appears these adaptations are individualized and contingent on situations, available resources, and changing priorities.16 Consequently, resiliency may be an essential tool for nurses to combat burnout in today’s complex health care systems.17

Although resilience and resourcefulness are conceptually related, each has distinctive features.18 Celinski frames resilience as transcendence and resourcefulness as transformation.19 Thus, while resilience suggests transcendence in terms of rising above, going beyond, exceeding, or excelling; resourcefulness reflects transformation, such as making changes in thoughts, feelings, behaviors, actions, or reactions. Resourcefulness has been conceptualized as an indicator of resilience.18

Resourcefulness comprises 2 dimensions, including the use of self-help strategies (personal resourcefulness) and seeking help from others (social resourcefulness), to self-regulate one’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to cope with high levels of stress, anxiety, or depression.18,20,21 Personal resourcefulness skills include the use of cognitive reframing, positive thinking, problem-solving, priority-setting, and planning ahead. Social resourcefulness involves actively seeking help from others. Formal sources of help include, but are not limited to, nursing and medical care practitioners and community organizations such as hospitals and clinics. Informal sources of help include family members, friends, peers, and coworkers.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses were especially challenged to provide support for each other because of limited nursing staff and treatment options, increased complex patient assignments, shortages of supplies, and reduced support services. Many nurses, however, were able to find innovative, peer-supported strategies for coping.13 Nurses’ use of resourcefulness skills is believed to be indicative of their resilience. This pilot project aimed to identify and evaluate some of these strategies and resourcefulness skills.

INTERVENTION

This pilot study among VA Northeast Ohio Health Care System (VANEOHS) nurses was designed to assess nursing burnout and resourcefulness during the pandemic. Those who agreed to participate completed a baseline survey on burnout and resourcefulness. Participants agreed to review a training video on resourcefulness skills (eg, relying on and exchanging ideas with others, and reframing and using ‘positive self-talk’). They were encouraged to document their experience with familiar and new resourcefulness skills. Weekly reminders (eg, emails and phone messages) reminded and coached participants in their journey.

The study identified and implemented an existing Resourcefulness Training (RT) intervention, which was developed for informal family caregivers and found to be effective.22 We measured burnout and resourcefulness preintervention and postintervention.23 This survey and educational intervention were reviewed by the VANEOHS institutional review board and ruled exempt. The survey also gathered information on nurses' contact with individuals infected with COVID-19.

Despite the many staffing and resource challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, a convenience sample of 12 nurses was recruited from nursing committees that continued to have scheduled meetings. These meetings allowed time to answer questions and provide information about the study. The majority of nurses queried declined to participate, citing no time, interest, or burnout. Participants completed a baseline survey, reviewed a 30-minute RT video, and tracked their experience for 28 days. Participants completed postintervention surveys 6 weeks after the video. Details of the survey and measures can be found in previous studies.20,21

RT is an online cognitive-behavioral intervention that teaches and reinforces personal (self-help) and social (help-seeking) resourcefulness skills that have not yet been tested in nurses or other health care professionals.22,24 The training included social resourcefulness (eg, from family, friends, others, and professionals) and personal resourcefulness (eg, problem-solving, positive thinking, self-control, organization skills). Participants were encouraged to review the videos as often as they preferred during these 4 weeks.

All 12 survey respondents were female and had received COVID-19 vaccinations according to the federal policy at the time of data collection. The number of patients cared for with COVID-19 infections varied widely (range, 1-1000). The baseline burnout score ranged from 1 (no burnout) to 3 (1 symptom of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion), with a mean score of 2.2. In the follow-up survey, the mean score was 2.0. At baseline, participants reported a variety of activities to manage stress and burnout, including times with friends and family, engaging in hobbies, and prayer. Postintervention, some participants mentioned using skills learned from RT, including reframing the situation positively by refocusing and putting stressors in perspective (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Recent American Nurses Association efforts to develop organizational and professional goals include the importance of nurses to recognize and manage stress to prevent burnout.25 The American Nurses Association Code of Ethics notes that nurses have the same duties to care for themselves as they do for others.25 Nurses have demonstrated the ability to adapt and remain resilient during stressful times. VA nurses are a resourceful group. Many used resourcefulness skills to manage stress and burnout even before the pandemic. For example, nurses identified using family/friends for support and validation, as well as prayer and meditation. Some of the new activities may have been influenced/inspired by RT, such as organizing schedules for problem-solving and distraction.

Relying on family and peers emerged as an essential resourcefulness skill. Support from peers—battle buddies—has been recognized as a key strategy among combat soldiers. A battle buddy is paired with a fellow soldier for support to keep each other informed about key instructions and information. This promotes cooperative problem-solving. Outcomes associated with battle buddies include increased morale and confidence, and decreased stress.25 Over time, it is hoped that these coaching/mentoring relationships will result in enhanced leadership skills. Battle buddy strategies are currently being adapted into health care environments.12,26 Such programs need to be further evaluated and information disseminated.

Findings from this pilot program support the use of interventions such as RT to decrease burnout among nurses. This study suggests that RT should be tested in a larger more representative sample to determine efficacy.

Limitations

This pilot study was limited by its small sample size, single facility, and female-only participants; the findings are not generalizable. Nurses were recruited from VA nursing committees and may not be representative of nurses in the general population. In addition, the RT intervention may require a longer time commitment to adequately determine efficacy. Another limitation was that personal or family exposure to COVID-19 was not measured, but may be a confounding variable. An additional limitation may have been the time interval. A baseline survey was completed prior to watching the teaching video. Daily logs were to be completed for 28 days. A post survey followed at 6 weeks. It is possible that there was insufficient time for the nurses to have the opportunity to use their resourcefulness skills within the short time frame of the study. While it supports the need for further studies, findings should be interpreted cautiously and not generalized. It may be premature based on these findings to conclude that the intervention will be effective for other populations. Further studies are needed to assess nurses’ preferences for healthy coping mechanisms, including RT.

Conclusions

As the nursing shortage continues, efforts to support diverse, innovative coping strategies remain a priority postpandemic. Nurses must be vigilant in appraising and managing their ability to cope and adapt to individual stress, while also being aware of the stress their colleagues are experiencing. Educational institutions, professional organizations, and health care facilities must strive to educate and support nurses to identify not only stress, but healthy coping mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office rapid response COVID-19 funding initiative, the Veteran Affairs Northeast Ohio Health Care System, and Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC). The Resourcefulness Scale, Resourcefulness Skills Scale, and the Resourcefulness Training intervention are copyrighted and were used with permission of the copyright holder, Jaclene A. Zauszniewski, PhD, RN-BC.

Nurses are recognized among the most trusted professions in the United States.1 Since the time of Florence Nightingale, nurses have been challenged to provide care to patients and soldiers with complex needs, including acute and chronic physical illness, as well as mental health issues. Nurses have traditionally met those challenges with perseverance and creativity but have also experienced stress and burnout.

A shortage of nurses has been linked to many interrelated factors including the retirement of bedside caregivers and educators, diverse care settings, expanding roles for nurses, and nurse burnout.2-4 Therefore, there is a critical need to better understand of how nurses can be supported while they care for patients, cope with stress, and maintain positive personal and professional outcomes. The objective of this pilot project was to assess US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) nurses’ levels of burnout and test an intervention to enhance resourcefulness skills during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background

Stress has many definitions. Hans Selye described it as a biological response of the body to any demand.5,6 Occupational stress is a process that occurs in which work environment stressors result in the development of psychological, behavioral, or physiological effects that can contribute to health.6 Occupational stress has been observed as prevalent among nurses.6 In 1960, Menzies identified sources of stress among nurses that include complex decision-making within a dynamic environment.7 Since the mid-1980s, nurses’ stress at work has increased because of legal, accreditation, ethical issues, fiscal pressures, staffing shortages, and the increasing integration of technology associated with clinical care.8

Sustained stress can lead to emotional exhaustion or burnout, which has been associated with nursing turnover, lower patient satisfaction, and patient safety risk.2,9 An American Nurses Foundation survey reported that 51% of US nurses feel exhausted, 43% overwhelmed, and 36% anxious; 28% express willingness to leave the profession.2 Burnout has been described as a response to physical or emotional stress leading to exhaustion, self-doubt, cynicism, and ineffectiveness.10 Employees with burnout are more likely to leave their jobs, take sick leave, and suffer from depression and relationship problems, and it affects nearly half of all US nurses, especially among critical care, pediatric, and oncology specialities.10,11 It has been well documented that unmitigated stress can lead to burnout and contribute to nurses leaving bedside care and the health care profession.2,3 Several studies on nursing stress and burnout have focused on its prevalence and negative outcomes.4,7,9 However, few studies have addressed building resiliency and resourcefulness for nurses.10,12,13

A 2021 National Academy of Medicine report advocated a multilevel approach to managing burnout and building resiliency among nurses.14 Taylor further identified specific interventions, ranging from primary prevention to treatment.15 Primary prevention could include educating nurses on self-awareness, coping strategies, and communication skills. Screening for burnout and providing resources for support would be a secondary level of intervention. For nurses who experienced severe burnout symptoms and left the workplace, strategies are sorely needed to provide healing and a return-to-work plan.15 This may include adjusting nurse schedules and nursing roles (such as admitting/discharge nurse or resource nurse).

RESILIENCY AND RESOURCEFULNESS

Rushton and colleagues describe resiliency as the “ability to face adverse situations, remain focused, and continue to be optimistic for the future.”4 For nurses in complex health care systems, resiliency is associated with reduced turnover and symptoms of burnout and improved mental health. Humans are thought to have an innate resiliency potential that evolves over time and fluctuates depending on the context (eg, societal conditions, moral/ethical values, commitments).4 It is believed that resiliency can contribute to the development of new neuropathways that can be used to manage and cope with stress, prevent burnout, and improve quality of life. However, it appears these adaptations are individualized and contingent on situations, available resources, and changing priorities.16 Consequently, resiliency may be an essential tool for nurses to combat burnout in today’s complex health care systems.17

Although resilience and resourcefulness are conceptually related, each has distinctive features.18 Celinski frames resilience as transcendence and resourcefulness as transformation.19 Thus, while resilience suggests transcendence in terms of rising above, going beyond, exceeding, or excelling; resourcefulness reflects transformation, such as making changes in thoughts, feelings, behaviors, actions, or reactions. Resourcefulness has been conceptualized as an indicator of resilience.18

Resourcefulness comprises 2 dimensions, including the use of self-help strategies (personal resourcefulness) and seeking help from others (social resourcefulness), to self-regulate one’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to cope with high levels of stress, anxiety, or depression.18,20,21 Personal resourcefulness skills include the use of cognitive reframing, positive thinking, problem-solving, priority-setting, and planning ahead. Social resourcefulness involves actively seeking help from others. Formal sources of help include, but are not limited to, nursing and medical care practitioners and community organizations such as hospitals and clinics. Informal sources of help include family members, friends, peers, and coworkers.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses were especially challenged to provide support for each other because of limited nursing staff and treatment options, increased complex patient assignments, shortages of supplies, and reduced support services. Many nurses, however, were able to find innovative, peer-supported strategies for coping.13 Nurses’ use of resourcefulness skills is believed to be indicative of their resilience. This pilot project aimed to identify and evaluate some of these strategies and resourcefulness skills.

INTERVENTION

This pilot study among VA Northeast Ohio Health Care System (VANEOHS) nurses was designed to assess nursing burnout and resourcefulness during the pandemic. Those who agreed to participate completed a baseline survey on burnout and resourcefulness. Participants agreed to review a training video on resourcefulness skills (eg, relying on and exchanging ideas with others, and reframing and using ‘positive self-talk’). They were encouraged to document their experience with familiar and new resourcefulness skills. Weekly reminders (eg, emails and phone messages) reminded and coached participants in their journey.

The study identified and implemented an existing Resourcefulness Training (RT) intervention, which was developed for informal family caregivers and found to be effective.22 We measured burnout and resourcefulness preintervention and postintervention.23 This survey and educational intervention were reviewed by the VANEOHS institutional review board and ruled exempt. The survey also gathered information on nurses' contact with individuals infected with COVID-19.

Despite the many staffing and resource challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, a convenience sample of 12 nurses was recruited from nursing committees that continued to have scheduled meetings. These meetings allowed time to answer questions and provide information about the study. The majority of nurses queried declined to participate, citing no time, interest, or burnout. Participants completed a baseline survey, reviewed a 30-minute RT video, and tracked their experience for 28 days. Participants completed postintervention surveys 6 weeks after the video. Details of the survey and measures can be found in previous studies.20,21

RT is an online cognitive-behavioral intervention that teaches and reinforces personal (self-help) and social (help-seeking) resourcefulness skills that have not yet been tested in nurses or other health care professionals.22,24 The training included social resourcefulness (eg, from family, friends, others, and professionals) and personal resourcefulness (eg, problem-solving, positive thinking, self-control, organization skills). Participants were encouraged to review the videos as often as they preferred during these 4 weeks.

All 12 survey respondents were female and had received COVID-19 vaccinations according to the federal policy at the time of data collection. The number of patients cared for with COVID-19 infections varied widely (range, 1-1000). The baseline burnout score ranged from 1 (no burnout) to 3 (1 symptom of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion), with a mean score of 2.2. In the follow-up survey, the mean score was 2.0. At baseline, participants reported a variety of activities to manage stress and burnout, including times with friends and family, engaging in hobbies, and prayer. Postintervention, some participants mentioned using skills learned from RT, including reframing the situation positively by refocusing and putting stressors in perspective (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Recent American Nurses Association efforts to develop organizational and professional goals include the importance of nurses to recognize and manage stress to prevent burnout.25 The American Nurses Association Code of Ethics notes that nurses have the same duties to care for themselves as they do for others.25 Nurses have demonstrated the ability to adapt and remain resilient during stressful times. VA nurses are a resourceful group. Many used resourcefulness skills to manage stress and burnout even before the pandemic. For example, nurses identified using family/friends for support and validation, as well as prayer and meditation. Some of the new activities may have been influenced/inspired by RT, such as organizing schedules for problem-solving and distraction.

Relying on family and peers emerged as an essential resourcefulness skill. Support from peers—battle buddies—has been recognized as a key strategy among combat soldiers. A battle buddy is paired with a fellow soldier for support to keep each other informed about key instructions and information. This promotes cooperative problem-solving. Outcomes associated with battle buddies include increased morale and confidence, and decreased stress.25 Over time, it is hoped that these coaching/mentoring relationships will result in enhanced leadership skills. Battle buddy strategies are currently being adapted into health care environments.12,26 Such programs need to be further evaluated and information disseminated.

Findings from this pilot program support the use of interventions such as RT to decrease burnout among nurses. This study suggests that RT should be tested in a larger more representative sample to determine efficacy.

Limitations

This pilot study was limited by its small sample size, single facility, and female-only participants; the findings are not generalizable. Nurses were recruited from VA nursing committees and may not be representative of nurses in the general population. In addition, the RT intervention may require a longer time commitment to adequately determine efficacy. Another limitation was that personal or family exposure to COVID-19 was not measured, but may be a confounding variable. An additional limitation may have been the time interval. A baseline survey was completed prior to watching the teaching video. Daily logs were to be completed for 28 days. A post survey followed at 6 weeks. It is possible that there was insufficient time for the nurses to have the opportunity to use their resourcefulness skills within the short time frame of the study. While it supports the need for further studies, findings should be interpreted cautiously and not generalized. It may be premature based on these findings to conclude that the intervention will be effective for other populations. Further studies are needed to assess nurses’ preferences for healthy coping mechanisms, including RT.

Conclusions

As the nursing shortage continues, efforts to support diverse, innovative coping strategies remain a priority postpandemic. Nurses must be vigilant in appraising and managing their ability to cope and adapt to individual stress, while also being aware of the stress their colleagues are experiencing. Educational institutions, professional organizations, and health care facilities must strive to educate and support nurses to identify not only stress, but healthy coping mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office rapid response COVID-19 funding initiative, the Veteran Affairs Northeast Ohio Health Care System, and Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC). The Resourcefulness Scale, Resourcefulness Skills Scale, and the Resourcefulness Training intervention are copyrighted and were used with permission of the copyright holder, Jaclene A. Zauszniewski, PhD, RN-BC.

1. Walker A. Nursing ranked as the most trusted profession for 22nd year in a row. January 23, 2024. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://nurse.org/articles/nursing-ranked-most-honest-profession

2. Mental health and wellness survey 1. American Nurses Foundation. August 2020. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/mental-health-and-wellbeing-survey/

3. Healthy nurse, healthy nation. American Nurses Association. May 1, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://www.healthynursehealthynation.org/

4. Rushton CH, Batcheller J, Schroeder K, Donohue P. Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high-intensity settings. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(5):412-420. doi:10.4037/ajcc2015291

5. Selye HA. History and general outline of the stress concept. Stress in Health and Disease. Butterworths; 1976:3-34.

6. Levy BS, Wegman DH, Baron SL, Sokas RK. Recognizing and preventing occupational and environmental disease and injury. Occupational and Environmental Health: Recognizing and Preventing Disease and Injury. 6th ed. Oxford University Press; 2011:59-77.

7. Menzies IEP. Nurses under stress. Int Nurs Rev. 1960;7:9-16.

8. Jennings BM. Turbulence. In: Hughes RG, ed. Advances in Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. 3rd ed. AHRQ Publication; 2007;2;193-202.

9. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987-1993. doi:10.1001/jama.288.16.1987

10. Magtibay DL, Chesak SS, Coughlin K, Sood A. Decreasing stress and burnout in nurses: efficacy of blended learning with stress management and resilience training program. J Nurs Adm. 2017;47(7-8):391-395. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000501

11. Halbesleben JR, Wakefield BJ, Wakefield DS, Cooper LB. Nurse burnout and patient safety outcomes: nurse safety perception versus reporting behavior. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30(5):560-577. doi:10.1177/0193945907311322

12. Sherman RO. Creating a Battle Buddy program. September 2, 2021. Accessed September 27, 2022. https://www.emergingrnleader.com/creating-a-battle-buddy-program

13. Godfrey KM, Scott SD. At the heart of the pandemic: nursing peer support. Nurse Leader. 2021:19(2),188-193. doi:10.1016/j.mnl.2020.09.006

14. Wakefield M, Williams DR, Le Menestrel S, and Flaubert JL, Editors; Committee on the future of nursing 2020 2030; National Academy of Medicine; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Institute of Medicine 2008. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/12089

15. Taylor RA. Contemporary issues: resilience training alone is an incomplete intervention. Nurs Educ Today. 2019;78:10-13. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2019.03.014

16. Hofmann SG, Gómez AF. Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):739-749. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.008

17. Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:598-611. doi:10.1192/bjp.147.6.598

18. Zauszniewski JA, Bekhet AK, Suresky MJ. Indicators of resilience in family members of persons with serious mental Illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2015;38(1):131-146. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2014.11.009

19. Celinski MJ. Framing resilience as transcendence and resourcefulness as transformation. In: Celinski MJ, Gow KM, eds. Continuity Versus Creative Response to Challenge: The Primacy of Resilience and Resourcefulness in Life and Therapy. Nova Science Pub Inc; 2011:11-30.

20. Zauszniewski JA, Lai CY, Tithiphontumrong S. Development and testing of the Resourcefulness Scale for Older Adults. J Nurs Meas. 2006:14(1):57-68. doi:10.1891.jnum.14.1.57

21. Zauszniewski JA, Bekhet AK. Measuring use of resourcefulness skills: psychometric testing of a new scale. ISRN Nurs. 2011;2011:787363. doi:10.5402/2011/787363

22. Zauszniewski JA, Lekhak N, Burant CJ, Variath M, Morris DL. preliminary evidence for effectiveness of resourcefulness training for women dementia caregivers. J Fam Med. 2016:3(5):1069.

23. Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):582-587. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3112-6

24. Zauszniewski JA Resourcefulness. In: Fitzpatrick JJ, ed. Encyclopedia of Nursing Research. 4th ed. 2018:632-634.

25. Combating Stress. American Nurses Association. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/combating-stress/

26. Albott CS, Wozniak JR, McGlinch BP, Wall MH, Gold BS, Vinogradov S. Battle Buddies: Rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(1):43-54. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912

1. Walker A. Nursing ranked as the most trusted profession for 22nd year in a row. January 23, 2024. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://nurse.org/articles/nursing-ranked-most-honest-profession

2. Mental health and wellness survey 1. American Nurses Foundation. August 2020. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/mental-health-and-wellbeing-survey/

3. Healthy nurse, healthy nation. American Nurses Association. May 1, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://www.healthynursehealthynation.org/

4. Rushton CH, Batcheller J, Schroeder K, Donohue P. Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high-intensity settings. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(5):412-420. doi:10.4037/ajcc2015291

5. Selye HA. History and general outline of the stress concept. Stress in Health and Disease. Butterworths; 1976:3-34.

6. Levy BS, Wegman DH, Baron SL, Sokas RK. Recognizing and preventing occupational and environmental disease and injury. Occupational and Environmental Health: Recognizing and Preventing Disease and Injury. 6th ed. Oxford University Press; 2011:59-77.

7. Menzies IEP. Nurses under stress. Int Nurs Rev. 1960;7:9-16.

8. Jennings BM. Turbulence. In: Hughes RG, ed. Advances in Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. 3rd ed. AHRQ Publication; 2007;2;193-202.

9. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987-1993. doi:10.1001/jama.288.16.1987

10. Magtibay DL, Chesak SS, Coughlin K, Sood A. Decreasing stress and burnout in nurses: efficacy of blended learning with stress management and resilience training program. J Nurs Adm. 2017;47(7-8):391-395. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000501

11. Halbesleben JR, Wakefield BJ, Wakefield DS, Cooper LB. Nurse burnout and patient safety outcomes: nurse safety perception versus reporting behavior. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30(5):560-577. doi:10.1177/0193945907311322

12. Sherman RO. Creating a Battle Buddy program. September 2, 2021. Accessed September 27, 2022. https://www.emergingrnleader.com/creating-a-battle-buddy-program

13. Godfrey KM, Scott SD. At the heart of the pandemic: nursing peer support. Nurse Leader. 2021:19(2),188-193. doi:10.1016/j.mnl.2020.09.006

14. Wakefield M, Williams DR, Le Menestrel S, and Flaubert JL, Editors; Committee on the future of nursing 2020 2030; National Academy of Medicine; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Institute of Medicine 2008. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/12089

15. Taylor RA. Contemporary issues: resilience training alone is an incomplete intervention. Nurs Educ Today. 2019;78:10-13. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2019.03.014

16. Hofmann SG, Gómez AF. Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):739-749. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.008

17. Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:598-611. doi:10.1192/bjp.147.6.598

18. Zauszniewski JA, Bekhet AK, Suresky MJ. Indicators of resilience in family members of persons with serious mental Illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2015;38(1):131-146. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2014.11.009

19. Celinski MJ. Framing resilience as transcendence and resourcefulness as transformation. In: Celinski MJ, Gow KM, eds. Continuity Versus Creative Response to Challenge: The Primacy of Resilience and Resourcefulness in Life and Therapy. Nova Science Pub Inc; 2011:11-30.

20. Zauszniewski JA, Lai CY, Tithiphontumrong S. Development and testing of the Resourcefulness Scale for Older Adults. J Nurs Meas. 2006:14(1):57-68. doi:10.1891.jnum.14.1.57

21. Zauszniewski JA, Bekhet AK. Measuring use of resourcefulness skills: psychometric testing of a new scale. ISRN Nurs. 2011;2011:787363. doi:10.5402/2011/787363

22. Zauszniewski JA, Lekhak N, Burant CJ, Variath M, Morris DL. preliminary evidence for effectiveness of resourcefulness training for women dementia caregivers. J Fam Med. 2016:3(5):1069.

23. Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):582-587. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3112-6

24. Zauszniewski JA Resourcefulness. In: Fitzpatrick JJ, ed. Encyclopedia of Nursing Research. 4th ed. 2018:632-634.

25. Combating Stress. American Nurses Association. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/combating-stress/

26. Albott CS, Wozniak JR, McGlinch BP, Wall MH, Gold BS, Vinogradov S. Battle Buddies: Rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(1):43-54. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912