User login

Study of Antimicrobial Scrubs

Healthcare workers' (HCWs) attire becomes contaminated with bacterial pathogens during the course of the workday,[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12] and Munoz‐Price et al.[13] recently demonstrated that finding bacterial pathogens on HCWs' white coats correlated with finding the same pathogens on their hands. Because of concern for an association between attire colonization and nosocomial infection, governmental agencies in England and Scotland banned HCWs from wearing white coats or long‐sleeve garments,[14, 15] despite evidence that such an approach does not reduce contamination.[12]

Newly developed antimicrobial textiles have been incorporated into HCW scrubs,[16, 17, 18, 19, 20] and commercial Web sites and product inserts report that these products can reduce bacterial contamination by 80.9% at 8 hours to greater than 99% under laboratory conditions depending on the product and microbe studied.[16, 17, 19] Because there are limited clinical data pertaining to the effectiveness of antimicrobial scrubs, we performed a prospective study designed to determine whether wearing these products reduced bacterial contamination of HCWs' scrubs or skin at the end of an 8‐hour workday.

METHODS

Design

The study was a prospective, unblinded, randomized, controlled trial that was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and conducted at Denver Health, a university‐affiliated public safety net hospital. No protocol changes occurred during the study.

Participants

Participants included hospitalist physicians, internal medicine residents, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and nurses who directly cared for patients hospitalized on internal medicine units between March 12, 2012 and August 28, 2012. Participants known to be pregnant or those who refused to participate in the study were excluded.

Intervention

Standard scrubs issued by the hospital were tested along with 2 different antimicrobial scrubs (scrub A and scrub B). Scrub A was made with a polyester microfiber material embedded with a proprietary antimicrobial chemical. Scrub B was a polyestercotton blend scrub that included 2 proprietary antimicrobial chemicals and silver embedded into the fabric. The standard scrub was made of a polyestercotton blend with no antimicrobial properties. All scrubs consisted of pants and a short‐sleeved shirt, with either a pocket at the left breast or lower front surface, and all were tested new prior to any washing or wear. Preliminary cultures were done on 2 scrubs in each group to assess the extent of preuse contamination. All providers were instructed not to wear white coats at any time during the day that they were wearing the scrubs. Providers were not told the type of scrub they received, but the antimicrobial scrubs had a different appearance and texture than the standard scrubs, so blinding was not possible.

Outcomes

The primary end point was the total bacterial colony count of samples obtained from the breast or lower front pocket, the sleeve cuff of the dominant hand, and the pant leg at the midthigh of the dominant leg on all scrubs after an 8‐hour workday. Secondary outcomes were the bacterial colony counts of cultures obtained from the volar surface of the wrists of the HCWs' dominant arm, and the colony counts of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin‐resistant enterococci (VRE), and resistant Gram‐negative bacteria on the 3 scrub types, all obtained after the 8‐hour workday.

Cultures were collected using a standardized RODAC imprint method[21] with BBL RODAC plates containing blood agar (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD). Cultures were incubated in ambient air at 35 to 37C for 18 to 22 hours. After incubation, visible colonies were counted using a dissecting microscope to a maximum of 200 colonies as recommended by the manufacturer. Colonies morphologically consistent with Staphylococcus species were subsequently tested for coagulase using a BactiStaph rapid latex agglutination test (Remel, Lenexa, KS). If positive, these colonies were subcultured to sheep blood agar (Remel) and BBL MRSA CHROMagar (Becton Dickinson) and incubated for an additional 18 to 24 hours. Characteristic growth on blood agar that also produced mauve‐colored colonies on CHROMagar was taken to indicate MRSA. Colonies morphologically suspicious for being VRE were identified and confirmed as VRE using a positive identification and susceptibility panel (Microscan; Siemens, Deerfield, IL). A negative combination panel (Microscan, Siemens) was also used to identify and confirm resistant Gram‐negative rods.

Each participant completed a survey that included questions that identified their occupation, whether they had had contact with patients who were known to be colonized or infected with MRSA, VRE, or resistant Gram‐negative rods during the testing period, and whether they experienced any adverse events that might relate to wearing the uniform.

Sample Size

We assumed that cultures taken from the sleeve of the control scrubs would have a mean ( standard deviation) colony count of 69 (67) based on data from our previous study.[12] Although the companies making the antimicrobial scrubs indicated that their respective products provided between 80.9% at 8 hours and >99% reduction in bacterial colony counts in laboratory settings, we assumed that a 70% decrease in colony count compared with standard scrubs could be clinically important. After adjusting for multiple comparisons and accounting for using nonparametric analyses with an unknown distribution, we estimated a need to recruit 35 subjects in each of 3 groups.

Randomization

The principal investigator and coinvestigators enrolled and consented participants. After obtaining consent, block randomization, stratified by occupation, occurred 1 day prior to the study using a computer‐generated table of random numbers.

Statistics

Data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt UniversityThe Institute for Medicine and Public Health, Nashville, TN) electronic data capture tools hosted at Denver Health. REDCap is a secure Web‐based application designed to support data collection for research studies, providing: (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry, (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures, (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages, and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources.[22]

Colony counts were compared using a Kruskal‐Wallis 1‐way analysis of variance by ranks. Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons resulted in a P<0.01 as indicating statistical significance. Proportions were compared using [2] analysis. All data are presented as medians with interquartile range (IQR) or proportions.

RESULTS

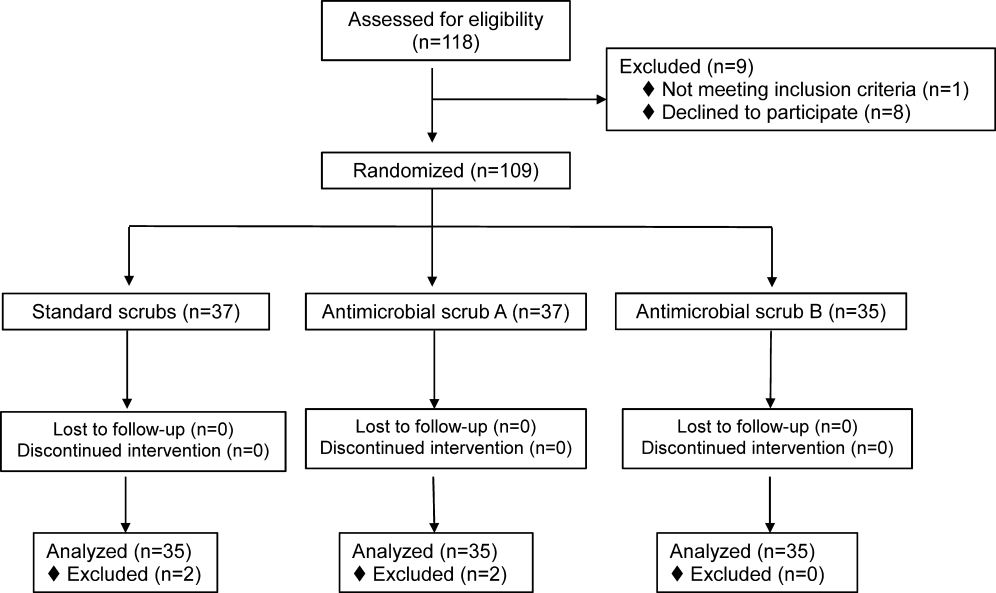

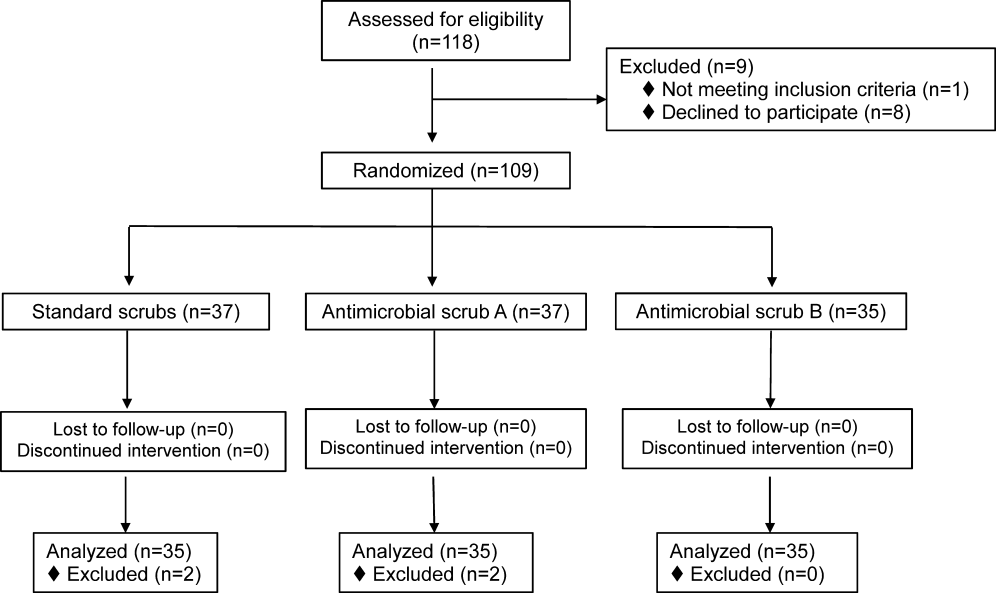

We screened 118 HCWs for participation and randomized 109, 37 in the control and antimicrobial scrub group A, and 35 in antimicrobial scrub group B (during the course of the study we neglected to culture the pockets of 2 participants in the standard scrub group and 2 in antimicrobial scrub group A). Because our primary end point was total colony count from cultures taken from 3 sites, data from these 4 subjects could not be used, and all the data from these 4 subjects were excluded from the primary analysis; 4 additional subjects were subsequently recruited allowing us to meet our block enrollment target (Figure 1). The first and last participants were studied on March 12, 2012 and August 28, 2012, respectively. The trial ended once the defined number of participants was enrolled. The occupations of the 105 participants are summarized in Table 1.

| All Subjects, N=105 | Standard Scrub, n=35 | Antimicrobial Scrub A, n=35 | Antimicrobial Scrub B, n=35 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare worker type, n (%) | ||||

| Attending physician | 11 (10) | 5 (14) | 3 (9) | 3 (9) |

| Intern/resident | 51 (49) | 17 (49) | 16 (46) | 18 (51) |

| Midlevels | 6 (6) | 2 (6) | 2 (6) | 2 (6) |

| Nurse | 37 (35) | 11 (31) | 14 (40) | 12 (34) |

| Cared for colonized or infected patient with antibiotic resistant organism, n (%) | 55 (52) | 16 (46) | 20 (57) | 19 (54) |

| Number of colonized or infected patients cared for, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 37 (67) | 10 (63) | 13 (65) | 14 (74) |

| 2 | 11 (20) | 4 (25) | 6 (30) | 1 (5) |

| 3 or more | 6 (11) | 2 (12) | 1 (5) | 3 (16) |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

Colony counts of all scrubs cultured prior to use never exceeded 10 colonies. The median (IQR) total colony counts from all sites on the scrubs was 99 (66182) for standard scrubs, 137 (84289) for antimicrobial scrub type A, and 138 (62274) for antimicrobial scrub type B (P=0.36). We found no significant differences between the colony counts cultured from any of the individual sites among the 3 groups, regardless of occupation (Table 2). No significant difference was observed with respect to colony counts cultured from the wrist among the 3 study groups (Table 2). Comparisons between groups were planned a priori if a difference across all groups was found. Given the nonsignificant P values across all scrub groups, no further comparisons were made.

| Total (From All Sites on Scrubs) | Sleeve Cuff | Thigh | Wrist | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| All subjects, N=105 | |||||

| Standard scrub | 99 (66182) | 41 (2070) | 20 (944) | 32 (2161) | 16 (540) |

| Antimicrobial scrub A | 137 (84289) | 65 (35117) | 33 (16124) | 41 (1586) | 23 (442) |

| Antimicrobial scrub B | 138 (62274) | 41 (2299) | 21 (941) | 40 (18107) | 15 (654) |

| P value | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.92 |

| Physicians and midlevels, n=68 | |||||

| Standard scrub | 115.5 (72.5173.5) | 44.5 (2270.5) | 27.5 (10.538.5) | 35 (2362.5) | 24.5 (755) |

| Antimicrobial scrub A | 210 (114289) | 86 (64120) | 39 (18129) | 49 (2486) | 24 (342) |

| Antimicrobial scrub B | 149 (68295) | 52 (26126) | 21 (1069) | 37 (18141) | 19 (872) |

| P value | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.85 | 0.76 |

| Nurses, n=37 | |||||

| Standard scrub | 89 (31236) | 37 (1348) | 13 (552) | 28 (1342) | 9 (321) |

| Antimicrobial scrub A | 105 (43256) | 45.5 (2258) | 21.5 (1654) | 38.5 (1268) | 17 (643) |

| Antimicrobial scrub B | 91.5 (60174.5) | 27 (1340) | 16 (7.526) | 51 (2186.5) | 10 (3.543.5) |

| P value | 0.86 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 0.41 |

Fifty‐five participants (52%) reported caring for patients who were known to be colonized or infected with an antibiotic‐resistant organism, 16 (46%) randomized to wear standard scrubs, and 20 (57%) and 19 (54%) randomized to wear antimicrobial scrub A or B, respectively (P=0.61). Of these, however, antibiotic‐resistant organisms were only cultured from the scrubs of 2 providers (1 with 1 colony of MRSA from the breast pocket of antimicrobial scrub A, 1 with 1 colony of MRSA cultured from the pocket of antimicrobial scrub B [P=0.55]), and from the wrist of only 1 provider (a multiresistant Gram‐negative rod who wore antimicrobial scrub B).

Adverse Events

Six subjects (5.7%) reported adverse events, all of whom were wearing antimicrobial scrubs (P=0.18). For participants wearing antimicrobial scrub A, 1 (3%) reported itchiness and 2 (6%) reported heaviness or poor breathability. For participants wearing antimicrobial scrub B, 1 (3%) reported redness, 1 (3%) reported itchiness, and 1 (3%) reported heaviness or poor breathability.

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this study are that we found no evidence indicating that either of the 2 antimicrobial scrubs tested reduced bacterial contamination or antibiotic‐resistant contamination on HCWs' scrubs or wrists compared with standard scrubs at the end of an 8‐hour workday, and that despite many HCWs being exposed to patients who were colonized or infected with antibiotic‐resistant bacteria, these organisms were only rarely cultured from their uniforms.

We found that HCWs in all 3 arms of the study had bacterial contamination on their scrubs and skin, consistent with previous studies showing that HCWs' uniforms are frequently contaminated with bacteria, including MRSA, VRE, and other pathogens.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12] We previously found that bacterial contamination of HCWs' uniforms occurs within hours of putting on newly laundered uniforms.[12]

Literature on the effectiveness of antimicrobial HCW uniforms when tested in clinical settings is limited. Bearman and colleagues[23] recently published the results of a study of 31 subjects who wore either standard or antimicrobial scrubs, crossing over every 4 weeks for 4 months, with random culturing done weekly at the beginning and end of a work shift. Scrubs were laundered an average of 1.5 times/week, but the timing of the laundering relative to when cultures were obtained was not reported. Very few isolates of MRSA, Gram‐negative rods, or VRE were found (only 3.9%, 0.4%, and 0.05% of the 2000 samples obtained, respectively), and no differences were observed with respect to the number of HCWs who had antibiotic‐resistant organisms cultured when they were wearing standard versus antimicrobial scrubs. Those who had MRSA cultured, however, had lower mean log colony counts when they were wearing the antimicrobial scrubs. The small number of samples with positive isolates, together with differences in the extent of before‐shift contamination among groups complicates interpreting these data. The authors concluded that a prospective trial was needed. We attempted to include the scrub studied by Bearman and colleagues[23] in our study, but the company had insufficient stock available at the time we tried to purchase the product.

Gross and colleagues[24] found no difference in the mean colony counts of cultures taken from silver‐impregnated versus standard scrubs in a pilot crossover study done with 10 HCWs (although there were trends toward higher colony counts when the subjects wore antimicrobial scrubs).

Antibiotic‐resistant bacteria were only cultured from 3 participants (2.9%) in our current study, compared to 16% of those randomized to wearing white coats in our previous study and 20% of those randomized to wearing standard scrubs.[12] This difference may be explained by several recent studies reporting that rates of MRSA infections in hospitals are decreasing.[25, 26] The rate of hospital‐acquired MRSA infection or colonization at our own institution decreased 80% from 2007 to 2012. At the times of our previous and current studies, providers were expected to wear gowns and gloves when caring for patients as per standard contact precautions. Rates of infection and colonization of VRE and resistant Gram‐negative rods have remained low at our hospital, and our data are consistent with the rates reported on HCWs' uniforms in other studies.[2, 5, 10]

Only 6 of our subjects reported adverse reactions, but all were wearing antimicrobial scrubs (P=0.18). Several of the participants described that the fabrics of the 2 antimicrobial scrubs were heavier and less breathable than the standard scrubs. We believe this difference is more likely to explain the adverse reactions reported than is any type of reaction to the specific chemicals in the fabrics.

Our study has several limitations. Because it was conducted on the general internal medicine units of a single university‐affiliated public hospital, the results may not generalize to other types of institutions or other inpatient services.

As we previously described,[12] the RODAC imprint method only samples a small area of HCWs' uniforms and thus does not represent total bacterial contamination.[21] We specifically cultured areas that are known to be highly contaminated (ie, sleeve cuffs and pockets). Although imprint methods have limitations (as do other methods for culturing clothing), they have been commonly utilized in studies assessing bacterial contamination of HCW clothing.[2, 3, 5]

Although some of the bacterial load we cultured could have come from the providers themselves, previous studies have shown that 80% to 90% of the resistant bacteria cultured from HCWs' attire come from other sources.[1, 2]

Because our sample size was calculated on the basis of being able to detect a difference of 70% in total bacterial colony count, our study was not large enough to exclude a lower level of effectiveness. However, we saw no trends suggesting the antimicrobial products might have a lower level of effectiveness.

We did not observe the hand‐washing practices of the participants, and accordingly, cannot confirm that these practices were the same in each of our 3 study groups. Intermittent, surreptitious monitoring of hand‐washing practices on our internal medicine units over the last several years has found compliance with hand hygiene recommendations varying from 70% to 90%.

Although the participants in our study were not explicitly told to which scrub they were randomized, the colors, appearances, and textures of the antimicrobial fabrics were different from the standard scrubs such that blinding was impossible. Participants wearing antimicrobial scrubs could have changed their hand hygiene practices (ie, less careful hand hygiene). Lack of blinding could also have led to over‐reporting of adverse events by the subjects randomized to wear the antimicrobial scrubs.

In an effort to treat all the scrubs in the same fashion, all were tested new, prior to being washed or previously worn. Studying the scrubs prior to washing or wearing could have increased the reports of adverse effects, as the fabrics could have been stiffer and more uncomfortable than they might have been at a later stage in their use.

Our study also has some strengths. Our participants included physicians, residents, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. Accordingly, our results should be generalizable to most HCWs. We also confirmed that the scrubs that were tested were nearly sterile prior to use.

In conclusion, we found no evidence suggesting that either of 2 antimicrobial scrubs tested decreased bacterial contamination of HCWs' scrubs or skin after an 8‐hour workday compared to standard scrubs. We also found that, although HCWs are frequently exposed to patients harboring antibiotic‐resistant bacteria, these bacteria were only rarely cultured from HCWs' scrubs or skin.

- , , , . Contamination of nurses' uniforms with Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 1969;2:233–235.

- , , . Contamination of protective clothing and nurses' uniforms in an isolation ward. J Hosp Infect. 1983;4:149–157.

- , , . Microbial flora on doctors' white coats. BMJ. 1991;303:1602–1604.

- . Bacterial contamination of nurses' uniforms: a study. Nursing Stand. 1998;13:37–42.

- , , . Bacterial flora on the white coats of medical students. J Hosp Infect. 2000;45:65–68.

- , , . Bacterial contamination of uniforms. J Hosp Infect. 2001;48:238–241.

- , , , et al. Significance of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) survey in a university teaching hospital. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:172–177.

- . Environmental contamination makes an important contribution to hospital infection. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65(suppl 2):50–54.

- , , , et al. Detection of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin‐resistant enterococci on the gowns and gloves of healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:583–589.

- , , , , , . Bacterial contamination of health care workers' white coats. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:101–105.

- , , , , , . Nursing and physician attire as possible source of nosocomial infections. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39:555–559.

- , , , , , . Newly cleaned physician uniforms and infrequently washed white coats have similar rates of bacterial contamination after an 8‐hour workday: a randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:177–182.

- , , , et al. Associations between bacterial contamination of health care workers' hands and contamination of white coats and scrubs. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:e245–e248.

- Department of Health. Uniforms and workwear: an evidence base for developing local policy. National Health Service, 17 September 2007. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/Publicationspolicyandguidance/DH_078433. Accessed January 29, 2010.

- Scottish Government Health Directorates. NHS Scotland dress code. Available at: http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/mels/CEL2008_53.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2010.

- Bio Shield Tech Web site. Bio Gardz–unisex scrub top–antimicrobial treatment. Available at: http://www.bioshieldtech.com/Bio_Gardz_Unisex_Scrub_Top_Antimicrobial_Tre_p/sbt01‐r‐p.htm. Accessed January 9, 2013.

- Doc Froc Web site and informational packet. Available at: http://www.docfroc.com. Accessed July 22, 2011.

- Vestagen Web site and informational packet. Available at: http://www.vestagen.com. Accessed July 22, 2011.

- Under Scrub apparel Web site. Testing. Available at: http://underscrub.com/testing. Accessed March 21, 2013.

- MediThreads Web site. Microban FAQ's. Available at: http://medithreads.com/faq/microban‐faqs. Accessed March 21, 2013.

- , , , , . Comparison of the Rodac imprint method to selective enrichment broth for recovery of vancomycin‐resistant enterococci and drug‐resistant Enterobacteriaceae from environmental surfaces. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4646–4648.

- , , , , , . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381.

- , , , et al. A crossover trial of antimicrobial scrubs to reduce methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus burden on healthcare worker apparel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:268–275.

- , , , , . Pilot study on the microbial contamination of conventional vs. silver‐impregnated uniforms worn by ambulance personnel during one week of emergency medical service. GMS Krankenhhyg Interdiszip. 2010;5.pii: Doc09.

- , , , et al. Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus blood and skin and soft tissue infections in the US military health system, 2005–2010. JAMA. 2012;308:50–59.

- , , , et al. Health care‐associated invasive MRSA infections, 2005–2008. JAMA. 2010;304:641–648.

Healthcare workers' (HCWs) attire becomes contaminated with bacterial pathogens during the course of the workday,[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12] and Munoz‐Price et al.[13] recently demonstrated that finding bacterial pathogens on HCWs' white coats correlated with finding the same pathogens on their hands. Because of concern for an association between attire colonization and nosocomial infection, governmental agencies in England and Scotland banned HCWs from wearing white coats or long‐sleeve garments,[14, 15] despite evidence that such an approach does not reduce contamination.[12]

Newly developed antimicrobial textiles have been incorporated into HCW scrubs,[16, 17, 18, 19, 20] and commercial Web sites and product inserts report that these products can reduce bacterial contamination by 80.9% at 8 hours to greater than 99% under laboratory conditions depending on the product and microbe studied.[16, 17, 19] Because there are limited clinical data pertaining to the effectiveness of antimicrobial scrubs, we performed a prospective study designed to determine whether wearing these products reduced bacterial contamination of HCWs' scrubs or skin at the end of an 8‐hour workday.

METHODS

Design

The study was a prospective, unblinded, randomized, controlled trial that was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and conducted at Denver Health, a university‐affiliated public safety net hospital. No protocol changes occurred during the study.

Participants

Participants included hospitalist physicians, internal medicine residents, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and nurses who directly cared for patients hospitalized on internal medicine units between March 12, 2012 and August 28, 2012. Participants known to be pregnant or those who refused to participate in the study were excluded.

Intervention

Standard scrubs issued by the hospital were tested along with 2 different antimicrobial scrubs (scrub A and scrub B). Scrub A was made with a polyester microfiber material embedded with a proprietary antimicrobial chemical. Scrub B was a polyestercotton blend scrub that included 2 proprietary antimicrobial chemicals and silver embedded into the fabric. The standard scrub was made of a polyestercotton blend with no antimicrobial properties. All scrubs consisted of pants and a short‐sleeved shirt, with either a pocket at the left breast or lower front surface, and all were tested new prior to any washing or wear. Preliminary cultures were done on 2 scrubs in each group to assess the extent of preuse contamination. All providers were instructed not to wear white coats at any time during the day that they were wearing the scrubs. Providers were not told the type of scrub they received, but the antimicrobial scrubs had a different appearance and texture than the standard scrubs, so blinding was not possible.

Outcomes

The primary end point was the total bacterial colony count of samples obtained from the breast or lower front pocket, the sleeve cuff of the dominant hand, and the pant leg at the midthigh of the dominant leg on all scrubs after an 8‐hour workday. Secondary outcomes were the bacterial colony counts of cultures obtained from the volar surface of the wrists of the HCWs' dominant arm, and the colony counts of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin‐resistant enterococci (VRE), and resistant Gram‐negative bacteria on the 3 scrub types, all obtained after the 8‐hour workday.

Cultures were collected using a standardized RODAC imprint method[21] with BBL RODAC plates containing blood agar (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD). Cultures were incubated in ambient air at 35 to 37C for 18 to 22 hours. After incubation, visible colonies were counted using a dissecting microscope to a maximum of 200 colonies as recommended by the manufacturer. Colonies morphologically consistent with Staphylococcus species were subsequently tested for coagulase using a BactiStaph rapid latex agglutination test (Remel, Lenexa, KS). If positive, these colonies were subcultured to sheep blood agar (Remel) and BBL MRSA CHROMagar (Becton Dickinson) and incubated for an additional 18 to 24 hours. Characteristic growth on blood agar that also produced mauve‐colored colonies on CHROMagar was taken to indicate MRSA. Colonies morphologically suspicious for being VRE were identified and confirmed as VRE using a positive identification and susceptibility panel (Microscan; Siemens, Deerfield, IL). A negative combination panel (Microscan, Siemens) was also used to identify and confirm resistant Gram‐negative rods.

Each participant completed a survey that included questions that identified their occupation, whether they had had contact with patients who were known to be colonized or infected with MRSA, VRE, or resistant Gram‐negative rods during the testing period, and whether they experienced any adverse events that might relate to wearing the uniform.

Sample Size

We assumed that cultures taken from the sleeve of the control scrubs would have a mean ( standard deviation) colony count of 69 (67) based on data from our previous study.[12] Although the companies making the antimicrobial scrubs indicated that their respective products provided between 80.9% at 8 hours and >99% reduction in bacterial colony counts in laboratory settings, we assumed that a 70% decrease in colony count compared with standard scrubs could be clinically important. After adjusting for multiple comparisons and accounting for using nonparametric analyses with an unknown distribution, we estimated a need to recruit 35 subjects in each of 3 groups.

Randomization

The principal investigator and coinvestigators enrolled and consented participants. After obtaining consent, block randomization, stratified by occupation, occurred 1 day prior to the study using a computer‐generated table of random numbers.

Statistics

Data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt UniversityThe Institute for Medicine and Public Health, Nashville, TN) electronic data capture tools hosted at Denver Health. REDCap is a secure Web‐based application designed to support data collection for research studies, providing: (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry, (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures, (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages, and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources.[22]

Colony counts were compared using a Kruskal‐Wallis 1‐way analysis of variance by ranks. Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons resulted in a P<0.01 as indicating statistical significance. Proportions were compared using [2] analysis. All data are presented as medians with interquartile range (IQR) or proportions.

RESULTS

We screened 118 HCWs for participation and randomized 109, 37 in the control and antimicrobial scrub group A, and 35 in antimicrobial scrub group B (during the course of the study we neglected to culture the pockets of 2 participants in the standard scrub group and 2 in antimicrobial scrub group A). Because our primary end point was total colony count from cultures taken from 3 sites, data from these 4 subjects could not be used, and all the data from these 4 subjects were excluded from the primary analysis; 4 additional subjects were subsequently recruited allowing us to meet our block enrollment target (Figure 1). The first and last participants were studied on March 12, 2012 and August 28, 2012, respectively. The trial ended once the defined number of participants was enrolled. The occupations of the 105 participants are summarized in Table 1.

| All Subjects, N=105 | Standard Scrub, n=35 | Antimicrobial Scrub A, n=35 | Antimicrobial Scrub B, n=35 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare worker type, n (%) | ||||

| Attending physician | 11 (10) | 5 (14) | 3 (9) | 3 (9) |

| Intern/resident | 51 (49) | 17 (49) | 16 (46) | 18 (51) |

| Midlevels | 6 (6) | 2 (6) | 2 (6) | 2 (6) |

| Nurse | 37 (35) | 11 (31) | 14 (40) | 12 (34) |

| Cared for colonized or infected patient with antibiotic resistant organism, n (%) | 55 (52) | 16 (46) | 20 (57) | 19 (54) |

| Number of colonized or infected patients cared for, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 37 (67) | 10 (63) | 13 (65) | 14 (74) |

| 2 | 11 (20) | 4 (25) | 6 (30) | 1 (5) |

| 3 or more | 6 (11) | 2 (12) | 1 (5) | 3 (16) |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

Colony counts of all scrubs cultured prior to use never exceeded 10 colonies. The median (IQR) total colony counts from all sites on the scrubs was 99 (66182) for standard scrubs, 137 (84289) for antimicrobial scrub type A, and 138 (62274) for antimicrobial scrub type B (P=0.36). We found no significant differences between the colony counts cultured from any of the individual sites among the 3 groups, regardless of occupation (Table 2). No significant difference was observed with respect to colony counts cultured from the wrist among the 3 study groups (Table 2). Comparisons between groups were planned a priori if a difference across all groups was found. Given the nonsignificant P values across all scrub groups, no further comparisons were made.

| Total (From All Sites on Scrubs) | Sleeve Cuff | Thigh | Wrist | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| All subjects, N=105 | |||||

| Standard scrub | 99 (66182) | 41 (2070) | 20 (944) | 32 (2161) | 16 (540) |

| Antimicrobial scrub A | 137 (84289) | 65 (35117) | 33 (16124) | 41 (1586) | 23 (442) |

| Antimicrobial scrub B | 138 (62274) | 41 (2299) | 21 (941) | 40 (18107) | 15 (654) |

| P value | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.92 |

| Physicians and midlevels, n=68 | |||||

| Standard scrub | 115.5 (72.5173.5) | 44.5 (2270.5) | 27.5 (10.538.5) | 35 (2362.5) | 24.5 (755) |

| Antimicrobial scrub A | 210 (114289) | 86 (64120) | 39 (18129) | 49 (2486) | 24 (342) |

| Antimicrobial scrub B | 149 (68295) | 52 (26126) | 21 (1069) | 37 (18141) | 19 (872) |

| P value | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.85 | 0.76 |

| Nurses, n=37 | |||||

| Standard scrub | 89 (31236) | 37 (1348) | 13 (552) | 28 (1342) | 9 (321) |

| Antimicrobial scrub A | 105 (43256) | 45.5 (2258) | 21.5 (1654) | 38.5 (1268) | 17 (643) |

| Antimicrobial scrub B | 91.5 (60174.5) | 27 (1340) | 16 (7.526) | 51 (2186.5) | 10 (3.543.5) |

| P value | 0.86 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 0.41 |

Fifty‐five participants (52%) reported caring for patients who were known to be colonized or infected with an antibiotic‐resistant organism, 16 (46%) randomized to wear standard scrubs, and 20 (57%) and 19 (54%) randomized to wear antimicrobial scrub A or B, respectively (P=0.61). Of these, however, antibiotic‐resistant organisms were only cultured from the scrubs of 2 providers (1 with 1 colony of MRSA from the breast pocket of antimicrobial scrub A, 1 with 1 colony of MRSA cultured from the pocket of antimicrobial scrub B [P=0.55]), and from the wrist of only 1 provider (a multiresistant Gram‐negative rod who wore antimicrobial scrub B).

Adverse Events

Six subjects (5.7%) reported adverse events, all of whom were wearing antimicrobial scrubs (P=0.18). For participants wearing antimicrobial scrub A, 1 (3%) reported itchiness and 2 (6%) reported heaviness or poor breathability. For participants wearing antimicrobial scrub B, 1 (3%) reported redness, 1 (3%) reported itchiness, and 1 (3%) reported heaviness or poor breathability.

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this study are that we found no evidence indicating that either of the 2 antimicrobial scrubs tested reduced bacterial contamination or antibiotic‐resistant contamination on HCWs' scrubs or wrists compared with standard scrubs at the end of an 8‐hour workday, and that despite many HCWs being exposed to patients who were colonized or infected with antibiotic‐resistant bacteria, these organisms were only rarely cultured from their uniforms.

We found that HCWs in all 3 arms of the study had bacterial contamination on their scrubs and skin, consistent with previous studies showing that HCWs' uniforms are frequently contaminated with bacteria, including MRSA, VRE, and other pathogens.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12] We previously found that bacterial contamination of HCWs' uniforms occurs within hours of putting on newly laundered uniforms.[12]

Literature on the effectiveness of antimicrobial HCW uniforms when tested in clinical settings is limited. Bearman and colleagues[23] recently published the results of a study of 31 subjects who wore either standard or antimicrobial scrubs, crossing over every 4 weeks for 4 months, with random culturing done weekly at the beginning and end of a work shift. Scrubs were laundered an average of 1.5 times/week, but the timing of the laundering relative to when cultures were obtained was not reported. Very few isolates of MRSA, Gram‐negative rods, or VRE were found (only 3.9%, 0.4%, and 0.05% of the 2000 samples obtained, respectively), and no differences were observed with respect to the number of HCWs who had antibiotic‐resistant organisms cultured when they were wearing standard versus antimicrobial scrubs. Those who had MRSA cultured, however, had lower mean log colony counts when they were wearing the antimicrobial scrubs. The small number of samples with positive isolates, together with differences in the extent of before‐shift contamination among groups complicates interpreting these data. The authors concluded that a prospective trial was needed. We attempted to include the scrub studied by Bearman and colleagues[23] in our study, but the company had insufficient stock available at the time we tried to purchase the product.

Gross and colleagues[24] found no difference in the mean colony counts of cultures taken from silver‐impregnated versus standard scrubs in a pilot crossover study done with 10 HCWs (although there were trends toward higher colony counts when the subjects wore antimicrobial scrubs).

Antibiotic‐resistant bacteria were only cultured from 3 participants (2.9%) in our current study, compared to 16% of those randomized to wearing white coats in our previous study and 20% of those randomized to wearing standard scrubs.[12] This difference may be explained by several recent studies reporting that rates of MRSA infections in hospitals are decreasing.[25, 26] The rate of hospital‐acquired MRSA infection or colonization at our own institution decreased 80% from 2007 to 2012. At the times of our previous and current studies, providers were expected to wear gowns and gloves when caring for patients as per standard contact precautions. Rates of infection and colonization of VRE and resistant Gram‐negative rods have remained low at our hospital, and our data are consistent with the rates reported on HCWs' uniforms in other studies.[2, 5, 10]

Only 6 of our subjects reported adverse reactions, but all were wearing antimicrobial scrubs (P=0.18). Several of the participants described that the fabrics of the 2 antimicrobial scrubs were heavier and less breathable than the standard scrubs. We believe this difference is more likely to explain the adverse reactions reported than is any type of reaction to the specific chemicals in the fabrics.

Our study has several limitations. Because it was conducted on the general internal medicine units of a single university‐affiliated public hospital, the results may not generalize to other types of institutions or other inpatient services.

As we previously described,[12] the RODAC imprint method only samples a small area of HCWs' uniforms and thus does not represent total bacterial contamination.[21] We specifically cultured areas that are known to be highly contaminated (ie, sleeve cuffs and pockets). Although imprint methods have limitations (as do other methods for culturing clothing), they have been commonly utilized in studies assessing bacterial contamination of HCW clothing.[2, 3, 5]

Although some of the bacterial load we cultured could have come from the providers themselves, previous studies have shown that 80% to 90% of the resistant bacteria cultured from HCWs' attire come from other sources.[1, 2]

Because our sample size was calculated on the basis of being able to detect a difference of 70% in total bacterial colony count, our study was not large enough to exclude a lower level of effectiveness. However, we saw no trends suggesting the antimicrobial products might have a lower level of effectiveness.

We did not observe the hand‐washing practices of the participants, and accordingly, cannot confirm that these practices were the same in each of our 3 study groups. Intermittent, surreptitious monitoring of hand‐washing practices on our internal medicine units over the last several years has found compliance with hand hygiene recommendations varying from 70% to 90%.

Although the participants in our study were not explicitly told to which scrub they were randomized, the colors, appearances, and textures of the antimicrobial fabrics were different from the standard scrubs such that blinding was impossible. Participants wearing antimicrobial scrubs could have changed their hand hygiene practices (ie, less careful hand hygiene). Lack of blinding could also have led to over‐reporting of adverse events by the subjects randomized to wear the antimicrobial scrubs.

In an effort to treat all the scrubs in the same fashion, all were tested new, prior to being washed or previously worn. Studying the scrubs prior to washing or wearing could have increased the reports of adverse effects, as the fabrics could have been stiffer and more uncomfortable than they might have been at a later stage in their use.

Our study also has some strengths. Our participants included physicians, residents, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. Accordingly, our results should be generalizable to most HCWs. We also confirmed that the scrubs that were tested were nearly sterile prior to use.

In conclusion, we found no evidence suggesting that either of 2 antimicrobial scrubs tested decreased bacterial contamination of HCWs' scrubs or skin after an 8‐hour workday compared to standard scrubs. We also found that, although HCWs are frequently exposed to patients harboring antibiotic‐resistant bacteria, these bacteria were only rarely cultured from HCWs' scrubs or skin.

Healthcare workers' (HCWs) attire becomes contaminated with bacterial pathogens during the course of the workday,[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12] and Munoz‐Price et al.[13] recently demonstrated that finding bacterial pathogens on HCWs' white coats correlated with finding the same pathogens on their hands. Because of concern for an association between attire colonization and nosocomial infection, governmental agencies in England and Scotland banned HCWs from wearing white coats or long‐sleeve garments,[14, 15] despite evidence that such an approach does not reduce contamination.[12]

Newly developed antimicrobial textiles have been incorporated into HCW scrubs,[16, 17, 18, 19, 20] and commercial Web sites and product inserts report that these products can reduce bacterial contamination by 80.9% at 8 hours to greater than 99% under laboratory conditions depending on the product and microbe studied.[16, 17, 19] Because there are limited clinical data pertaining to the effectiveness of antimicrobial scrubs, we performed a prospective study designed to determine whether wearing these products reduced bacterial contamination of HCWs' scrubs or skin at the end of an 8‐hour workday.

METHODS

Design

The study was a prospective, unblinded, randomized, controlled trial that was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and conducted at Denver Health, a university‐affiliated public safety net hospital. No protocol changes occurred during the study.

Participants

Participants included hospitalist physicians, internal medicine residents, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and nurses who directly cared for patients hospitalized on internal medicine units between March 12, 2012 and August 28, 2012. Participants known to be pregnant or those who refused to participate in the study were excluded.

Intervention

Standard scrubs issued by the hospital were tested along with 2 different antimicrobial scrubs (scrub A and scrub B). Scrub A was made with a polyester microfiber material embedded with a proprietary antimicrobial chemical. Scrub B was a polyestercotton blend scrub that included 2 proprietary antimicrobial chemicals and silver embedded into the fabric. The standard scrub was made of a polyestercotton blend with no antimicrobial properties. All scrubs consisted of pants and a short‐sleeved shirt, with either a pocket at the left breast or lower front surface, and all were tested new prior to any washing or wear. Preliminary cultures were done on 2 scrubs in each group to assess the extent of preuse contamination. All providers were instructed not to wear white coats at any time during the day that they were wearing the scrubs. Providers were not told the type of scrub they received, but the antimicrobial scrubs had a different appearance and texture than the standard scrubs, so blinding was not possible.

Outcomes

The primary end point was the total bacterial colony count of samples obtained from the breast or lower front pocket, the sleeve cuff of the dominant hand, and the pant leg at the midthigh of the dominant leg on all scrubs after an 8‐hour workday. Secondary outcomes were the bacterial colony counts of cultures obtained from the volar surface of the wrists of the HCWs' dominant arm, and the colony counts of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin‐resistant enterococci (VRE), and resistant Gram‐negative bacteria on the 3 scrub types, all obtained after the 8‐hour workday.

Cultures were collected using a standardized RODAC imprint method[21] with BBL RODAC plates containing blood agar (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD). Cultures were incubated in ambient air at 35 to 37C for 18 to 22 hours. After incubation, visible colonies were counted using a dissecting microscope to a maximum of 200 colonies as recommended by the manufacturer. Colonies morphologically consistent with Staphylococcus species were subsequently tested for coagulase using a BactiStaph rapid latex agglutination test (Remel, Lenexa, KS). If positive, these colonies were subcultured to sheep blood agar (Remel) and BBL MRSA CHROMagar (Becton Dickinson) and incubated for an additional 18 to 24 hours. Characteristic growth on blood agar that also produced mauve‐colored colonies on CHROMagar was taken to indicate MRSA. Colonies morphologically suspicious for being VRE were identified and confirmed as VRE using a positive identification and susceptibility panel (Microscan; Siemens, Deerfield, IL). A negative combination panel (Microscan, Siemens) was also used to identify and confirm resistant Gram‐negative rods.

Each participant completed a survey that included questions that identified their occupation, whether they had had contact with patients who were known to be colonized or infected with MRSA, VRE, or resistant Gram‐negative rods during the testing period, and whether they experienced any adverse events that might relate to wearing the uniform.

Sample Size

We assumed that cultures taken from the sleeve of the control scrubs would have a mean ( standard deviation) colony count of 69 (67) based on data from our previous study.[12] Although the companies making the antimicrobial scrubs indicated that their respective products provided between 80.9% at 8 hours and >99% reduction in bacterial colony counts in laboratory settings, we assumed that a 70% decrease in colony count compared with standard scrubs could be clinically important. After adjusting for multiple comparisons and accounting for using nonparametric analyses with an unknown distribution, we estimated a need to recruit 35 subjects in each of 3 groups.

Randomization

The principal investigator and coinvestigators enrolled and consented participants. After obtaining consent, block randomization, stratified by occupation, occurred 1 day prior to the study using a computer‐generated table of random numbers.

Statistics

Data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt UniversityThe Institute for Medicine and Public Health, Nashville, TN) electronic data capture tools hosted at Denver Health. REDCap is a secure Web‐based application designed to support data collection for research studies, providing: (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry, (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures, (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages, and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources.[22]

Colony counts were compared using a Kruskal‐Wallis 1‐way analysis of variance by ranks. Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons resulted in a P<0.01 as indicating statistical significance. Proportions were compared using [2] analysis. All data are presented as medians with interquartile range (IQR) or proportions.

RESULTS

We screened 118 HCWs for participation and randomized 109, 37 in the control and antimicrobial scrub group A, and 35 in antimicrobial scrub group B (during the course of the study we neglected to culture the pockets of 2 participants in the standard scrub group and 2 in antimicrobial scrub group A). Because our primary end point was total colony count from cultures taken from 3 sites, data from these 4 subjects could not be used, and all the data from these 4 subjects were excluded from the primary analysis; 4 additional subjects were subsequently recruited allowing us to meet our block enrollment target (Figure 1). The first and last participants were studied on March 12, 2012 and August 28, 2012, respectively. The trial ended once the defined number of participants was enrolled. The occupations of the 105 participants are summarized in Table 1.

| All Subjects, N=105 | Standard Scrub, n=35 | Antimicrobial Scrub A, n=35 | Antimicrobial Scrub B, n=35 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare worker type, n (%) | ||||

| Attending physician | 11 (10) | 5 (14) | 3 (9) | 3 (9) |

| Intern/resident | 51 (49) | 17 (49) | 16 (46) | 18 (51) |

| Midlevels | 6 (6) | 2 (6) | 2 (6) | 2 (6) |

| Nurse | 37 (35) | 11 (31) | 14 (40) | 12 (34) |

| Cared for colonized or infected patient with antibiotic resistant organism, n (%) | 55 (52) | 16 (46) | 20 (57) | 19 (54) |

| Number of colonized or infected patients cared for, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 37 (67) | 10 (63) | 13 (65) | 14 (74) |

| 2 | 11 (20) | 4 (25) | 6 (30) | 1 (5) |

| 3 or more | 6 (11) | 2 (12) | 1 (5) | 3 (16) |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

Colony counts of all scrubs cultured prior to use never exceeded 10 colonies. The median (IQR) total colony counts from all sites on the scrubs was 99 (66182) for standard scrubs, 137 (84289) for antimicrobial scrub type A, and 138 (62274) for antimicrobial scrub type B (P=0.36). We found no significant differences between the colony counts cultured from any of the individual sites among the 3 groups, regardless of occupation (Table 2). No significant difference was observed with respect to colony counts cultured from the wrist among the 3 study groups (Table 2). Comparisons between groups were planned a priori if a difference across all groups was found. Given the nonsignificant P values across all scrub groups, no further comparisons were made.

| Total (From All Sites on Scrubs) | Sleeve Cuff | Thigh | Wrist | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| All subjects, N=105 | |||||

| Standard scrub | 99 (66182) | 41 (2070) | 20 (944) | 32 (2161) | 16 (540) |

| Antimicrobial scrub A | 137 (84289) | 65 (35117) | 33 (16124) | 41 (1586) | 23 (442) |

| Antimicrobial scrub B | 138 (62274) | 41 (2299) | 21 (941) | 40 (18107) | 15 (654) |

| P value | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.92 |

| Physicians and midlevels, n=68 | |||||

| Standard scrub | 115.5 (72.5173.5) | 44.5 (2270.5) | 27.5 (10.538.5) | 35 (2362.5) | 24.5 (755) |

| Antimicrobial scrub A | 210 (114289) | 86 (64120) | 39 (18129) | 49 (2486) | 24 (342) |

| Antimicrobial scrub B | 149 (68295) | 52 (26126) | 21 (1069) | 37 (18141) | 19 (872) |

| P value | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.85 | 0.76 |

| Nurses, n=37 | |||||

| Standard scrub | 89 (31236) | 37 (1348) | 13 (552) | 28 (1342) | 9 (321) |

| Antimicrobial scrub A | 105 (43256) | 45.5 (2258) | 21.5 (1654) | 38.5 (1268) | 17 (643) |

| Antimicrobial scrub B | 91.5 (60174.5) | 27 (1340) | 16 (7.526) | 51 (2186.5) | 10 (3.543.5) |

| P value | 0.86 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 0.41 |

Fifty‐five participants (52%) reported caring for patients who were known to be colonized or infected with an antibiotic‐resistant organism, 16 (46%) randomized to wear standard scrubs, and 20 (57%) and 19 (54%) randomized to wear antimicrobial scrub A or B, respectively (P=0.61). Of these, however, antibiotic‐resistant organisms were only cultured from the scrubs of 2 providers (1 with 1 colony of MRSA from the breast pocket of antimicrobial scrub A, 1 with 1 colony of MRSA cultured from the pocket of antimicrobial scrub B [P=0.55]), and from the wrist of only 1 provider (a multiresistant Gram‐negative rod who wore antimicrobial scrub B).

Adverse Events

Six subjects (5.7%) reported adverse events, all of whom were wearing antimicrobial scrubs (P=0.18). For participants wearing antimicrobial scrub A, 1 (3%) reported itchiness and 2 (6%) reported heaviness or poor breathability. For participants wearing antimicrobial scrub B, 1 (3%) reported redness, 1 (3%) reported itchiness, and 1 (3%) reported heaviness or poor breathability.

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this study are that we found no evidence indicating that either of the 2 antimicrobial scrubs tested reduced bacterial contamination or antibiotic‐resistant contamination on HCWs' scrubs or wrists compared with standard scrubs at the end of an 8‐hour workday, and that despite many HCWs being exposed to patients who were colonized or infected with antibiotic‐resistant bacteria, these organisms were only rarely cultured from their uniforms.

We found that HCWs in all 3 arms of the study had bacterial contamination on their scrubs and skin, consistent with previous studies showing that HCWs' uniforms are frequently contaminated with bacteria, including MRSA, VRE, and other pathogens.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12] We previously found that bacterial contamination of HCWs' uniforms occurs within hours of putting on newly laundered uniforms.[12]

Literature on the effectiveness of antimicrobial HCW uniforms when tested in clinical settings is limited. Bearman and colleagues[23] recently published the results of a study of 31 subjects who wore either standard or antimicrobial scrubs, crossing over every 4 weeks for 4 months, with random culturing done weekly at the beginning and end of a work shift. Scrubs were laundered an average of 1.5 times/week, but the timing of the laundering relative to when cultures were obtained was not reported. Very few isolates of MRSA, Gram‐negative rods, or VRE were found (only 3.9%, 0.4%, and 0.05% of the 2000 samples obtained, respectively), and no differences were observed with respect to the number of HCWs who had antibiotic‐resistant organisms cultured when they were wearing standard versus antimicrobial scrubs. Those who had MRSA cultured, however, had lower mean log colony counts when they were wearing the antimicrobial scrubs. The small number of samples with positive isolates, together with differences in the extent of before‐shift contamination among groups complicates interpreting these data. The authors concluded that a prospective trial was needed. We attempted to include the scrub studied by Bearman and colleagues[23] in our study, but the company had insufficient stock available at the time we tried to purchase the product.

Gross and colleagues[24] found no difference in the mean colony counts of cultures taken from silver‐impregnated versus standard scrubs in a pilot crossover study done with 10 HCWs (although there were trends toward higher colony counts when the subjects wore antimicrobial scrubs).

Antibiotic‐resistant bacteria were only cultured from 3 participants (2.9%) in our current study, compared to 16% of those randomized to wearing white coats in our previous study and 20% of those randomized to wearing standard scrubs.[12] This difference may be explained by several recent studies reporting that rates of MRSA infections in hospitals are decreasing.[25, 26] The rate of hospital‐acquired MRSA infection or colonization at our own institution decreased 80% from 2007 to 2012. At the times of our previous and current studies, providers were expected to wear gowns and gloves when caring for patients as per standard contact precautions. Rates of infection and colonization of VRE and resistant Gram‐negative rods have remained low at our hospital, and our data are consistent with the rates reported on HCWs' uniforms in other studies.[2, 5, 10]

Only 6 of our subjects reported adverse reactions, but all were wearing antimicrobial scrubs (P=0.18). Several of the participants described that the fabrics of the 2 antimicrobial scrubs were heavier and less breathable than the standard scrubs. We believe this difference is more likely to explain the adverse reactions reported than is any type of reaction to the specific chemicals in the fabrics.

Our study has several limitations. Because it was conducted on the general internal medicine units of a single university‐affiliated public hospital, the results may not generalize to other types of institutions or other inpatient services.

As we previously described,[12] the RODAC imprint method only samples a small area of HCWs' uniforms and thus does not represent total bacterial contamination.[21] We specifically cultured areas that are known to be highly contaminated (ie, sleeve cuffs and pockets). Although imprint methods have limitations (as do other methods for culturing clothing), they have been commonly utilized in studies assessing bacterial contamination of HCW clothing.[2, 3, 5]

Although some of the bacterial load we cultured could have come from the providers themselves, previous studies have shown that 80% to 90% of the resistant bacteria cultured from HCWs' attire come from other sources.[1, 2]

Because our sample size was calculated on the basis of being able to detect a difference of 70% in total bacterial colony count, our study was not large enough to exclude a lower level of effectiveness. However, we saw no trends suggesting the antimicrobial products might have a lower level of effectiveness.

We did not observe the hand‐washing practices of the participants, and accordingly, cannot confirm that these practices were the same in each of our 3 study groups. Intermittent, surreptitious monitoring of hand‐washing practices on our internal medicine units over the last several years has found compliance with hand hygiene recommendations varying from 70% to 90%.

Although the participants in our study were not explicitly told to which scrub they were randomized, the colors, appearances, and textures of the antimicrobial fabrics were different from the standard scrubs such that blinding was impossible. Participants wearing antimicrobial scrubs could have changed their hand hygiene practices (ie, less careful hand hygiene). Lack of blinding could also have led to over‐reporting of adverse events by the subjects randomized to wear the antimicrobial scrubs.

In an effort to treat all the scrubs in the same fashion, all were tested new, prior to being washed or previously worn. Studying the scrubs prior to washing or wearing could have increased the reports of adverse effects, as the fabrics could have been stiffer and more uncomfortable than they might have been at a later stage in their use.

Our study also has some strengths. Our participants included physicians, residents, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. Accordingly, our results should be generalizable to most HCWs. We also confirmed that the scrubs that were tested were nearly sterile prior to use.

In conclusion, we found no evidence suggesting that either of 2 antimicrobial scrubs tested decreased bacterial contamination of HCWs' scrubs or skin after an 8‐hour workday compared to standard scrubs. We also found that, although HCWs are frequently exposed to patients harboring antibiotic‐resistant bacteria, these bacteria were only rarely cultured from HCWs' scrubs or skin.

- , , , . Contamination of nurses' uniforms with Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 1969;2:233–235.

- , , . Contamination of protective clothing and nurses' uniforms in an isolation ward. J Hosp Infect. 1983;4:149–157.

- , , . Microbial flora on doctors' white coats. BMJ. 1991;303:1602–1604.

- . Bacterial contamination of nurses' uniforms: a study. Nursing Stand. 1998;13:37–42.

- , , . Bacterial flora on the white coats of medical students. J Hosp Infect. 2000;45:65–68.

- , , . Bacterial contamination of uniforms. J Hosp Infect. 2001;48:238–241.

- , , , et al. Significance of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) survey in a university teaching hospital. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:172–177.

- . Environmental contamination makes an important contribution to hospital infection. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65(suppl 2):50–54.

- , , , et al. Detection of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin‐resistant enterococci on the gowns and gloves of healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:583–589.

- , , , , , . Bacterial contamination of health care workers' white coats. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:101–105.

- , , , , , . Nursing and physician attire as possible source of nosocomial infections. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39:555–559.

- , , , , , . Newly cleaned physician uniforms and infrequently washed white coats have similar rates of bacterial contamination after an 8‐hour workday: a randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:177–182.

- , , , et al. Associations between bacterial contamination of health care workers' hands and contamination of white coats and scrubs. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:e245–e248.

- Department of Health. Uniforms and workwear: an evidence base for developing local policy. National Health Service, 17 September 2007. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/Publicationspolicyandguidance/DH_078433. Accessed January 29, 2010.

- Scottish Government Health Directorates. NHS Scotland dress code. Available at: http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/mels/CEL2008_53.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2010.

- Bio Shield Tech Web site. Bio Gardz–unisex scrub top–antimicrobial treatment. Available at: http://www.bioshieldtech.com/Bio_Gardz_Unisex_Scrub_Top_Antimicrobial_Tre_p/sbt01‐r‐p.htm. Accessed January 9, 2013.

- Doc Froc Web site and informational packet. Available at: http://www.docfroc.com. Accessed July 22, 2011.

- Vestagen Web site and informational packet. Available at: http://www.vestagen.com. Accessed July 22, 2011.

- Under Scrub apparel Web site. Testing. Available at: http://underscrub.com/testing. Accessed March 21, 2013.

- MediThreads Web site. Microban FAQ's. Available at: http://medithreads.com/faq/microban‐faqs. Accessed March 21, 2013.

- , , , , . Comparison of the Rodac imprint method to selective enrichment broth for recovery of vancomycin‐resistant enterococci and drug‐resistant Enterobacteriaceae from environmental surfaces. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4646–4648.

- , , , , , . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381.

- , , , et al. A crossover trial of antimicrobial scrubs to reduce methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus burden on healthcare worker apparel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:268–275.

- , , , , . Pilot study on the microbial contamination of conventional vs. silver‐impregnated uniforms worn by ambulance personnel during one week of emergency medical service. GMS Krankenhhyg Interdiszip. 2010;5.pii: Doc09.

- , , , et al. Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus blood and skin and soft tissue infections in the US military health system, 2005–2010. JAMA. 2012;308:50–59.

- , , , et al. Health care‐associated invasive MRSA infections, 2005–2008. JAMA. 2010;304:641–648.

- , , , . Contamination of nurses' uniforms with Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 1969;2:233–235.

- , , . Contamination of protective clothing and nurses' uniforms in an isolation ward. J Hosp Infect. 1983;4:149–157.

- , , . Microbial flora on doctors' white coats. BMJ. 1991;303:1602–1604.

- . Bacterial contamination of nurses' uniforms: a study. Nursing Stand. 1998;13:37–42.

- , , . Bacterial flora on the white coats of medical students. J Hosp Infect. 2000;45:65–68.

- , , . Bacterial contamination of uniforms. J Hosp Infect. 2001;48:238–241.

- , , , et al. Significance of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) survey in a university teaching hospital. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:172–177.

- . Environmental contamination makes an important contribution to hospital infection. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65(suppl 2):50–54.

- , , , et al. Detection of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin‐resistant enterococci on the gowns and gloves of healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:583–589.

- , , , , , . Bacterial contamination of health care workers' white coats. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:101–105.

- , , , , , . Nursing and physician attire as possible source of nosocomial infections. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39:555–559.

- , , , , , . Newly cleaned physician uniforms and infrequently washed white coats have similar rates of bacterial contamination after an 8‐hour workday: a randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:177–182.

- , , , et al. Associations between bacterial contamination of health care workers' hands and contamination of white coats and scrubs. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:e245–e248.

- Department of Health. Uniforms and workwear: an evidence base for developing local policy. National Health Service, 17 September 2007. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/Publicationspolicyandguidance/DH_078433. Accessed January 29, 2010.

- Scottish Government Health Directorates. NHS Scotland dress code. Available at: http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/mels/CEL2008_53.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2010.

- Bio Shield Tech Web site. Bio Gardz–unisex scrub top–antimicrobial treatment. Available at: http://www.bioshieldtech.com/Bio_Gardz_Unisex_Scrub_Top_Antimicrobial_Tre_p/sbt01‐r‐p.htm. Accessed January 9, 2013.

- Doc Froc Web site and informational packet. Available at: http://www.docfroc.com. Accessed July 22, 2011.

- Vestagen Web site and informational packet. Available at: http://www.vestagen.com. Accessed July 22, 2011.

- Under Scrub apparel Web site. Testing. Available at: http://underscrub.com/testing. Accessed March 21, 2013.

- MediThreads Web site. Microban FAQ's. Available at: http://medithreads.com/faq/microban‐faqs. Accessed March 21, 2013.

- , , , , . Comparison of the Rodac imprint method to selective enrichment broth for recovery of vancomycin‐resistant enterococci and drug‐resistant Enterobacteriaceae from environmental surfaces. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4646–4648.

- , , , , , . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381.

- , , , et al. A crossover trial of antimicrobial scrubs to reduce methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus burden on healthcare worker apparel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:268–275.

- , , , , . Pilot study on the microbial contamination of conventional vs. silver‐impregnated uniforms worn by ambulance personnel during one week of emergency medical service. GMS Krankenhhyg Interdiszip. 2010;5.pii: Doc09.

- , , , et al. Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus blood and skin and soft tissue infections in the US military health system, 2005–2010. JAMA. 2012;308:50–59.

- , , , et al. Health care‐associated invasive MRSA infections, 2005–2008. JAMA. 2010;304:641–648.

© 2013 Society of Hospital Medicine

Bacterial Contamination of Work Wear

In September 2007, the British Department of Health developed guidelines for health care workers regarding uniforms and work wear that banned the traditional white coat and other long‐sleeved garments in an attempt to decrease nosocomial bacterial transmission.1 Similar policies have recently been adopted in Scotland.2 Interestingly, the National Health Service report acknowledged that evidence was lacking that would support that white coats and long‐sleeved garments caused nosocomial infection.1, 3 Although many studies have documented that health care work clothes are contaminated with bacteria, including methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcal aureus (MRSA) and other pathogenic species,413 none have determined whether avoiding white coats and switching to short‐sleeved garments decreases bacterial contamination.

We performed a prospective, randomized, controlled trial designed to compare the extent of bacterial contamination of physicians' white coats with that of newly laundered, standardized short‐sleeved uniforms. Our hypotheses were that infrequently cleaned white coats would have greater bacterial contamination than uniforms, that the extent of contamination would be inversely related to the frequency with which the coats were washed, and that the increased contamination of the cuffs of the white coats would result in increased contamination of the skin of the wrists. Our results led us also to assess the rate at which bacterial contamination of short‐sleeved uniforms occurs during the workday.

Methods

The study was conducted at Denver Health, a university‐affiliated public safety‐net hospital and was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Trial Design

The study was a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. No protocol changes occurred during the study.

Participants

Participants included residents and hospitalists directly caring for patients on internal medicine units between August 1, 2008 and November 15, 2009.

Intervention

Subjects wore either a standard, newly laundered, short‐sleeved uniform or continued to wear their own white coats.

Outcomes

The primary end point was the percentage of subjects contaminated with MRSA. Cultures were collected using a standardized RODAC imprint method14 with BBL RODAC plates containing trypticase soy agar with lecithin and polysorbate 80 (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) 8 hours after the physicians started their work day. All physicians had cultures obtained from the breast pocket and sleeve cuff (long‐sleeved for the white coats, short‐sleeved for the uniforms) and from the skin of the volar surface of the wrist of their dominant hand. Those wearing white coats also had cultures obtained from the mid‐biceps level of the sleeve of the dominant hand, as this location closely approximated the location of the cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms.

Cultures were incubated in ambient air at 35C‐37C for 1822 hours. After incubation, visible colonies were counted using a dissecting microscope to a maximum of 200 colonies at the recommendation of the manufacturer. Colonies that were morphologically consistent with Staphylococcus species by colony growth and Gram stain were further tested for coagulase using a BactiStaph rapid latex agglutination test (Remel, Lenexa, KS). If positive, these colonies were subcultured to sheep blood agar (Remel, Lenexa, KS) and BBL MRSA Chromagar (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) and incubated for an additional 1824 hours. Characteristic growth on blood agar that also produced mauve‐colored colonies on chromagar was taken to indicate MRSA.

A separate set of 10 physicians donned newly laundered, short‐sleeved uniforms at 6:30 AM for culturing from the breast pocket and sleeve cuff of the dominant hand prior to and 2.5, 5, and 8 hours after they were donned by the participants (with culturing of each site done on separate days to avoid the effects of obtaining multiple cultures at the same site on the same day). These cultures were not assessed for MRSA.

At the time that consent was obtained, all participants completed an anonymous survey that assessed the frequency with which they normally washed or changed their white coats.

Sample Size

Based on the finding that 20% of our first 20 participants were colonized with MRSA, we determined that to find a 25% difference in the percentage of subjects colonized with MRSA in the 2 groups, with a power of 0.8 and P < 0.05 being significant (2‐sided Fisher's exact test), 50 subjects would be needed in each group.

Randomization

Randomization of potential participants occurred 1 day prior to the study using a computer‐generated table of random numbers. The principal investigator and a coinvestigator enrolled participants. Consent was obtained from those randomized to wear a newly laundered standard short‐sleeved uniform at the time of randomization so that they could don the uniforms when arriving at the hospital the following morning (at approximately 6:30 AM). Physicians in this group were also instructed not to wear their white coats at any time during the day they were wearing the uniforms. Physicians randomized to wear their own white coats were not notified or consented until the day of the study, a few hours prior to the time the cultures were obtained. This approach prevented them from either changing their white coats or washing them prior to the time the cultures were taken.

Because our study included both employees of the hospital and trainees, a number of protection measures were required. No information of any sort was collected about those who agreed or refused to participate in the study. In addition, the request to participate in the study did not come from the person's direct supervisor.

Statistical Methods

All data were collected and entered using Excel for Mac 2004 version 11.5.4. All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 4.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

The Wilcoxon rank‐sum test and chi square analysis were used to seek differences in colony count and percentage of cultures with MRSA, respectively, in cultures obtained: (1) from the sleeve cuffs and pockets of the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs and pockets of the uniforms, (2) from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms, (3) from the mid‐biceps area of the sleeve sof the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs of the uniforms, and (4) from the skin of the wrists of those wearing white coats compared with those wearing the uniforms. Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons was applied, with a P < 0.125 indicating significance.

Friedman's test and repeated‐measures logistic regression were used to seek differences in colony count or of the percentage of cultures with MRSA, respectively, on white coats or uniforms by site of culture on both garments. A P < 0.05 indicated significance for these analyses.

The Kruskal‐Wallis and chi‐square tests were utilized to test the effect of white coat wash frequency on colony count and MRSA contamination, respectively.

All data are presented as medians with 95% confidence intervals or proportions.

Results

Participant Flow

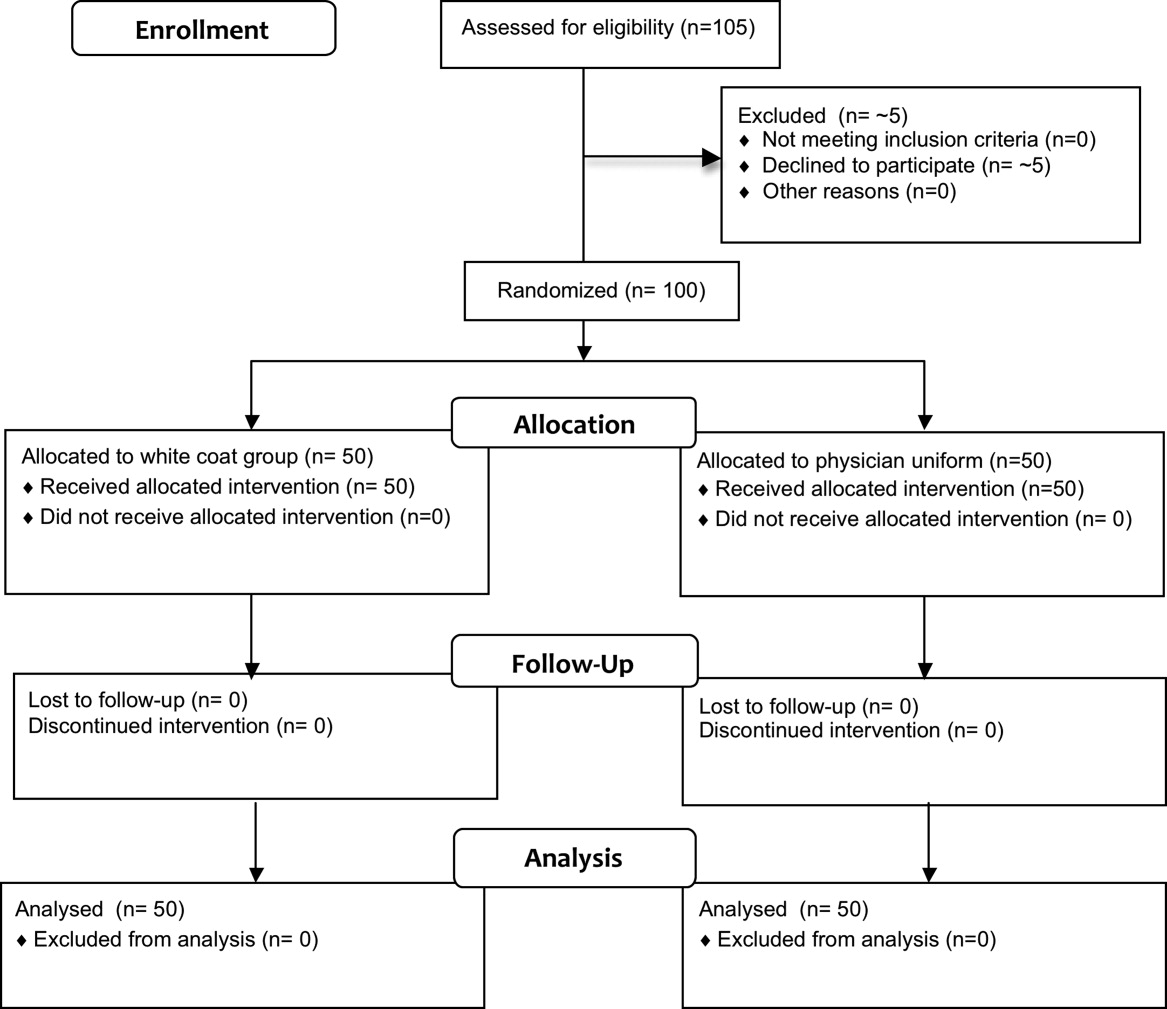

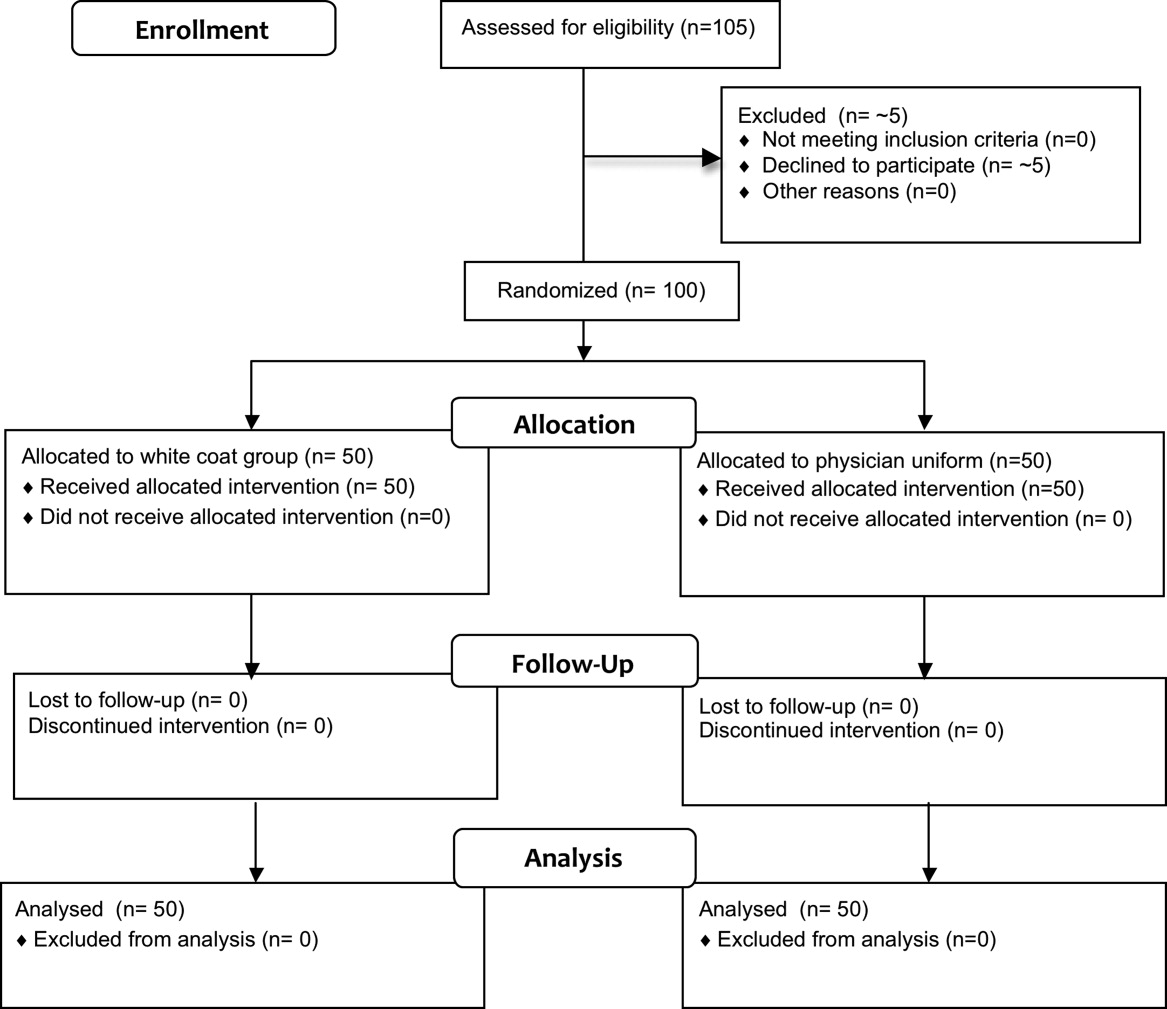

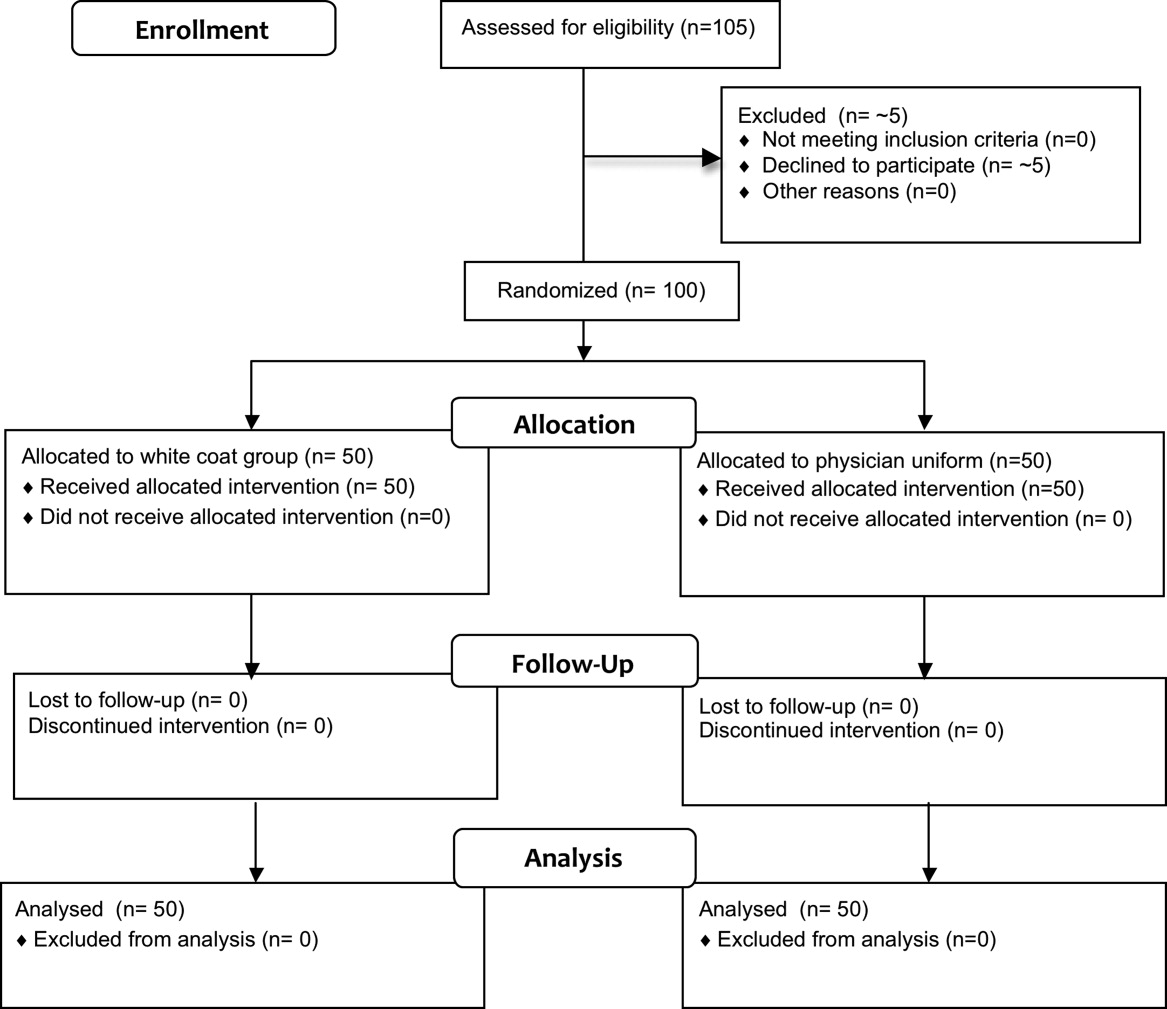

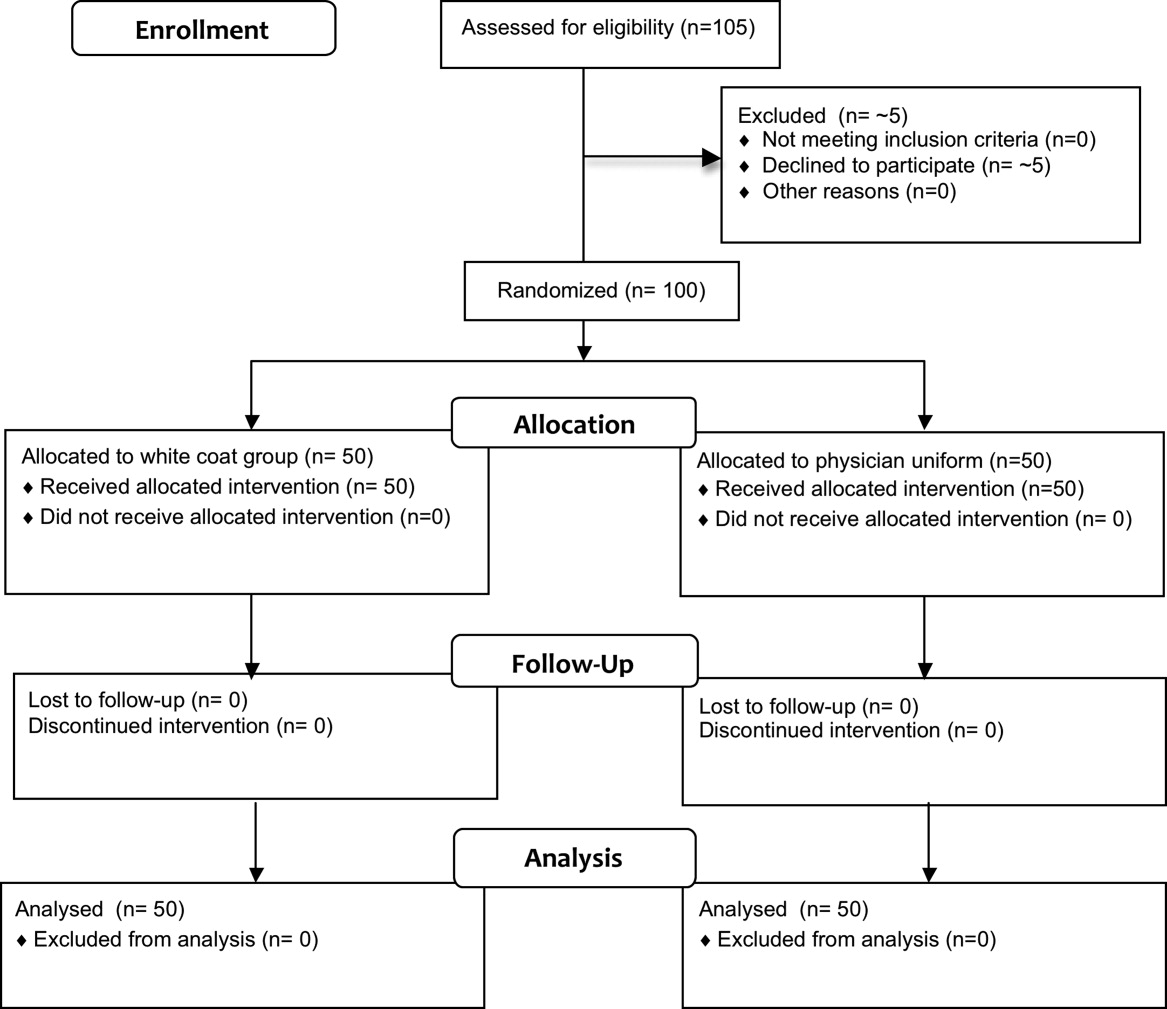

Fifty physicians were studied in each group, all of whom completed the survey. In general, more than 95% of potential participants approached agreed to participate in the study (Figure 1).

Recruitment

The first and last physicians were studied in August 2008 and November 2009, respectively. The trial ended when the specified number of participants (50 in each group) had been enrolled.

Data on Entry

No data were recorded from the participants at the time of randomization in compliance with institutional review board regulations pertaining to employment issues that could arise when studying members of the workforce.

Outcomes

No significant differences were found between the colony counts cultured from white coats (104 [80127]) versus newly laundered uniforms (142 [83213]), P = 0.61. No significant differences were found between the colony counts cultured from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats (58.5 [4866]) versus the uniforms (37 [2768]), P = 0.07, or between the colony counts cultured from the pockets of the white coats (45.5 [3254]) versus the uniforms (74.5 [4897], P = 0.040. Bonferroni corrections were used for multiple comparisons such that a P < 0.0125 was considered significant. Cultures from at least 1 site of 8 of 50 physicians (16%) wearing white coats and 10 of 50 physicians (20%) wearing short‐sleeved uniforms were positive for MRSA (P = .60).

Colony counts were greater in cultures obtained from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats compared with the pockets or mid‐biceps area (Table 1). For the uniforms, no difference in colony count in cultures from the pockets versus sleeve cuffs was observed. No difference was found when comparing the number of subjects with MRSA contamination of the 3 sites of the white coats or the 2 sites of the uniforms (Table 1).

| White Coat (n = 50) | P | Uniforms (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | ||||

| Sleeve cuff | 58.5 (4866) | < 0.0001 | 37.0 (2768) | 0.25 |

| 45.5 (3254) | 74.5 (4897) | |||

| Mid‐biceps area of sleeve | 25.5 (2029) | |||

| MRSA contamination, n (%) | ||||

| Sleeve cuff | 4 (8%) | 0.71 | 6 (12%) | 0.18 |

| 5 (10%) | 9 (18%) | |||

| Mid‐biceps area of sleeve | 3 (6%) |

No difference was observed with respect to colony count or the percentage of subjects positive for MRSA in cultures obtained from the mid‐biceps area of the white coats versus those from the cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms (Table 2).

| White Coat Mid‐Biceps (n = 50) | Uniform Sleeve Cuff (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | 25.5 (2029) | 37.0 (2768) | 0.07 |

| MRSA contamination, n (%) | 3 (6%) | 6 (12%) | 0.49 |

No difference was observed with respect to colony count or the percentage of subjects positive for MRSA in cultures obtained from the volar surface of the wrists of subjects wearing either of the 2 garments (Table 3).

| White Coat (n = 50) | Uniform (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | 23.5 (1740) | 40.5 (2859) | 0.09 |

| MRSA Contamination, n (% of subjects) | 3 (6%) | 5 (10%) | 0.72 |

The frequency with which physicians randomized to wearing their white coats admitted to washing or changing their coats varied markedly (Table 4). No significant differences were found with respect to total colony count (P = 0.81), colony count by site (data not shown), or percentage of physicians contaminated with MRSA (P = 0.22) as a function of washing or changing frequency (Table 4).

| White Coat Washing Frequency | Number of Subjects (%) | Total Colony Count (All Sites), Median (95% CI) | Number with MRSA Contamination, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly | 15 (30%) | 124 (107229) | 1 (7%) |

| Every 2 weeks | 21 (42%) | 156 (90237) | 6 (29%) |

| Every 4 weeks | 8 (16%) | 89 (41206) | 0 (0%) |

| Every 8 weeks | 5 (10%) | 140 (58291) | 2 (40%) |

| Rarely | 1 (2%) | 150 | 0 (0%) |