User login

Identifying Child Abuse

According to data from the US Department of Health and Human Services, child protection services received more than 3.3 million reports of alleged maltreatment in 2009 that involved about six million children, and about 62% of reports required subsequent action.1 Child abuse is an ever-growing problem that affects children of both genders and in all ages, races, and socioeconomic levels. Few issues generate the concern, anger, and frustration as the abuse or neglect of children.

Primary care providers and emergency department personnel are often the child’s initial point of entry into the health care system. Clinicians who see and treat young patients can play an essential role in the recognition and reporting of child abuse. By frequently reviewing the risk factors for child abuse, its signs and symptoms, and its typical and atypical presentations, clinicians can be prepared to act when appropriate and help break the cycle of child abuse.

LEGAL MANDATES, DEFINITIONS

A relatively new concept, child abuse has been designated as a major public health issue by the United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization.2-5 In 1874, when it was decided by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) to include children within the defined animal kingdom, the movement to protect children began in the United States.6

Both federal and state agencies have created definitions for child abuse and neglect. The key federal legislation to address child abuse and neglect, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), as Amended by the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003,7,8 defines child abuse and neglect as “any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation, or an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.”7 Although ongoing revisions of the CAPTA legislation (the most recent “reauthorization” published in 20109) become increasingly inclusive of both children’s and families’ concerns, this definition has remained consistent.

This is not the case with state definitions, however. Because these vary, it can be difficult to compare rates of reported maltreatment from state to state. Also varying among states, and among counties within some states, are recommendations for substantiation of child maltreatment. The validity of the reported data can be impaired by a lack of coordination or cooperation among different agencies and jurisdictions.

IDENTIFYING THE VICTIMS

The spectrum of child abuse includes multiple forms, which often overlap (see Table 11,9,10), and can almost always have the potential for death.11 According to findings from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, despite worsening economic conditions in 2009, the child maltreatment data compiled that year showed an overall 2% decline in cases of substantiated maltreatment from the previous year.1,11

However, during that same period, child maltreatment–associated fatalities rose 3%, from 1,628 deaths in 2008 to 1,671 in 2009,1 suggesting an increase in the severity of abuse. The emotional, social, and financial ramifications of child abuse affect the local and national community, as well as each child and each family.

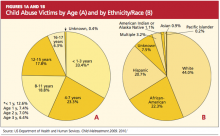

Children younger than 1 year, the most vulnerable to maltreatment, represent the largest proportion of substantiated abuse. One-third of all children reported as abused in 2009 were younger than 4, and children between ages 4 and 7 represented one-fifth of cases.1 Figure 1a1 categorizes the incidence of child abuse by age level, and Figure 1b1 by ethnicity/race.

Risk Factors

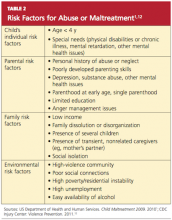

A number of factors, though not necessarily direct causes, have been shown to increase children’s risk for abuse or neglect. These include personal characteristics of the child and parent, and family- or environment-related factors1,12 (see Table 2,1). It is often combinations of risk factors (eg, characteristics of a parent or caregiver in addition to a specific social environment) that are most likely to increase the likelihood of abuse.

Children with special needs (physical disabilities or chronic illness, neurologic impairment, mental health issues) that increase the caregiver’s burden are at increased risk for abuse.1,12 Children with behavior disorders and mental retardation have been found at increased risk for various forms of abuse—neglect and physical or sexual maltreatment13—whereas children with speech or language disabilities are at increased risk for neglect (whether physical, emotional, or even educational14).

Children with physical limitations who experience physical abuse are reportedly subject to more serious injury than their healthier counterparts.14 Their inability to see, hear, move, or communicate, or to dress or bathe themselves independently may make them susceptible to rough, careless, or intrusive personal care, or neglect of their personal needs. Low self-esteem, whatever its cause, also appears to be a significant risk factor for intentional abuse.15

It is often the case that children with disabilities do not report abuse because they are unable to recognize an act as abusive. Depending on the severity of a child’s disability and his or her ordinarily atypical presentation, the abuse may never be discovered.15

Poverty appears to be a contributing factor. Children from families of low socioeconomic status are at least three times as likely as other children to be abused and seven times as likely to experience neglect.14 It has been conjectured that these children are more likely to have contact with social workers, law enforcement officers, and representatives of other agencies with an increased awareness of the manifestations of child abuse. Abuse within affluent families may be underreported, as such families have the wherewithal to protect themselves from detection and prosecution.16

PRESENTATION

There is no “gold standard” for making a confirmed diagnosis of child abuse,17 and no “typical” presentation of an abused child (see case study). Dress that is inappropriate for the season and consistently poor hygiene are indicative of neglect. Symptoms of abuse may be overt or silent, and signs of physical abuse are often hidden beneath clothing. Children who are physically abused often explain their injuries by saying “I fell,” or may even respond to questioning by saying, “I don’t know.” The parent or caregiver may attribute bruises or even broken bones to falls or rough play with other children. Bruises, the most common visible form of child abuse,18 may suggest the nature of injury by their location, patterns, and various stages of healing.

Fractures are the second most common presenting symptom among children experiencing physical abuse.17 According to findings from a meta-analysis by Kemp et al,19 determining whether fractures have occurred accidentally depends on three factors:

Age. Among children younger than 1 year, 25% to 56% of fractures are attributable to intentional harm. In one landmark study, one fracture in nine was found to have resulted from abuse, among children younger than 18 months—compared with one in 205 among children ages 19 months to 5 years.19,20

Site. In cases not involving a motor vehicle accident or other traumatic event, it has been determined in ongoing systematic reviews by Welsh researchers that rib fractures have a 71% probability of being inflicted, followed by humeral fractures (about 50% probability), then by femoral fractures or skull fractures (about 33% probability).19,21

Fracture type. Fracture types suggestive of abuse differ by site. Among humeral fractures, for example, a midshaft fracture is more likely to have been inflicted, whereas a supracondylar fracture is more likely the result of accidental injury. Both parietal and linear skull fractures may occur accidentally or through physical abuse.19 Epiphyseal-metaphyseal fractures, vertebral compression fractures, and lateral clavicle fractures have been associated with child abuse.22,23 Multiple or bilateral fractures have an increased association with abuse.19,20,24

Injuries that are inconsistent with the given history should raise red flags, and they should be carefully investigated, with findings documented. Minor falls cause minor injuries, not potentially life-threatening ones.

As with fractures, burns may have specific features that help the clinician distinguish between accidental and intentional. Uniform depth, well-defined edges, and multiple lesions are more likely to indicate nonaccidental contact burns, particularly when found in “protected” sites (eg, perineal and gluteal areas).18 Accidental cigarette burns are usually ovoid or irregular in shape and superficial, while those intentionally inflicted are round, deep, and well-demarcated and are often grouped on the hands, feet, or face.18,25 Burns on the chest, upper limbs, and palms of the hands are likely to be accidental; the face, the backs of the hands, the lower stomach, back, buttocks, legs, and feet are often the target of intentional burns.18,26

HISTORY

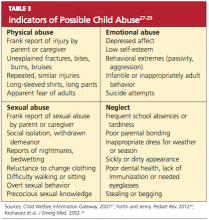

A key factor in suspected abuse is the child’s history. During history taking, clinicians should be alert to the evidence-based indicators of potential child abuse, as shown in Table 327-29. Not every child who exhibits these characteristics is an abused child, nor will every abused child exhibit any or all of these characteristics. Through artful, careful history taking and astute observation of the child, the clinician is usually able to distinguish between the heightened anxiety that may occur in any child during the history-taking process and the demeanor of a child who may have been coerced or threatened to maintain secrecy.

Engaging the child in a reassuring manner, the clinician can use a conversational style of questioning, such as, “Tell me how you got that bruise on your arm,” rather than a direct question: “Did [name] hit you on the arm with [his/her] fist?”

An observation of unusually sexualized behaviors or a report of excessive masturbation is more likely to be associated with sexual abuse than are genital findings (which are infrequently found).

Physical Examination

When a child presents with an acute injury or bruising is detected and the clinician’s findings are inconsistent with the given history, suspicion should be raised. The injuries inflicted by physical abuse are often hidden beneath the child’s clothing (specifically, underwear); for this reason, it is important to have children undressed during a physical exam.

The routine physical exam of an abused child may reveal defensive bruising or other wounds, trauma to the mouth, breasts, buttocks, genitalia, or anus, with possible bleeding or discharge. More commonly, the physical exam findings are normal—as is true in the majority of examinations for sexual abuse.30 In one large study, abnormal findings (eg, recent or healed genital injuries; presence of a sexually transmitted disease) were found in only about 4% of children who had been referred for an examination for suspected sexual abuse.18,31 Clearly, an appearance of “normal” does not mean “nothing happened.”32

According to CDC guidelines,33 investigation of suspected sexual abuse (for example, when a genital herpes infection is detected) should be conducted by appropriately trained, experienced clinicians—ideally, by a pediatric subspecialist in child abuse. Although the primary care clinician may examine the child briefly for visible bruises or wounds, it is essential for a specialist to perform the genital exam.33 Use of mild sedation with close monitoring may be advisable during the genital examination.30

Mimics of Child Abuse

Several conditions, including metabolic, genetic, and congenital disorders, have been reported to mimic the physical manifestations of child abuse and neglect17,22,34 (see Table 4,17,18,22,25,33-35). While health care professionals are legally and ethically bound to report abuse, conditions that may mimic abuse must be ruled out first, to avoid the mistaken removal of children from loving homes.

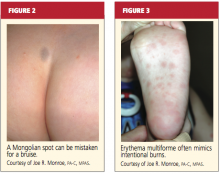

Mongolian spots, for example (see Figure 2), are frequently mistaken for bruising and reported to authorities, causing unnecessary disruption for both family and child.34,36 They typically appear as macular blue-gray pigmentation of the skin, usually on the sacrum. Resulting from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during fetal development, these “spots” may be present at birth or may appear during the neonatal period. Mongolian spots are most common in Native American, African-American, Asian, and Hispanic patients, are benign, and often disappear by age 4.

Other cutaneous manifestations that can mimic an intentional injury include molluscum contagiosum, a viral infection manifesting as a rash that may mimic the genital warts of human papillomavirus, and erythematous, edematous, and/or vesiculobullous lesions18,35 (see Figure 3). Severe diaper rash, photodermatitis, and certain allergic reactions can mimic intentional burns.25

Often mistaken for a nonaccidental injury is hair tourniquet syndrome—the circumferential strangulation of one or more appendages (eg, finger, toe, penis) by human hair or fibers.34 This uncommon condition, usually unintentional and of unknown incidence, can represent a surgical emergency; failure to recognize it in a timely fashion may lead to ischemia or necrosis, necessitating amputation of the affected appendage.37

Metabolic bone disease, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, can sometimes explain frequent fractures.17

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

In the primary care setting, the detection of child abuse is unexpected. However, it is often here that children are initially seen for an injury, or suspicions are raised during a routine physical.30 In the case of spontaneous disclosure of abuse, explicit, word-for-word documentation is required. The child, who may feel guilty, embarrassed, or ashamed, must be reassured that he or she is not at fault.

Either a child abuse specialist or the primary care clinician bases the ultimate diagnosis of child abuse on findings from the history and physical examination. These findings will direct the clinician’s decision to order diagnostic laboratory studies and/or diagnostic x-rays.

Diagnostic Studies

Depending on the child’s age and the type of presentation, recommended imaging studies include an x-ray skeletal survey of a child younger than 2 (see “Skeletal Survey Reading of 5-Month-Old Boy,”) or an older child with thoracoabdominal injuries that the history does not explain satisfactorily.23 For children ages 2 to 5, focused plain films of the area of suspected injury (eg, skull, chest, extremities) are considered appropriate.23,38

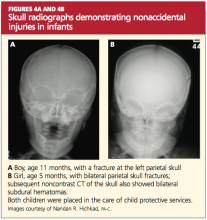

Noncontrast head CT may be appropriate in the presence of skull fractures, (as in Figures 4a and 4b) intracranial injuries, seizures, or other neurologic signs and symptoms (followed by MRI if further assessment is needed). CT with contrast may be considered when x-rays reveal certain abnormalities, the child is considered at high risk for abuse (for example, when inconsistencies are found in the history), or when soft-tissue injuries are suspected.23,39

About 5% of sexually abused children contract a sexually transmitted disease.30 Appropriate laboratory tests that can be performed in the office setting include:

- Urinalysis for presence of semen

- Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) for chlamydia and gonorrhea (with positive results requiring that sexual abuse be considered in children beyond neonatal age, according to CDC guidelines33); anorectal and pharyngeal infections with Neisseria gonorrhoeae are commonly found in sexually abused children

- Serologic testing for HIV33

- Urine pregnancy testing in patients of childbearing age.

As these lab specimens are collected, chain of custody must be maintained. Results may be used as evidence in the event of prosecution.

REFERRALS AND FOLLOW-UP

What referrals are made—to clinical specialists, law enforcement, social services, and other agencies—is based on the nature of the abuse, the dynamics of the family involved, the identity of the alleged perpetrator, and the perceived need to ensure the child’s safety. It is the role of these interrelated agencies to confirm the child’s diagnosis, provide for the child’s immediate safety, and ensure links within the systems involved to follow him or her into adulthood, if necessary.

Timely referral to specialized clinicians may spare the child from having to undergo multiple examinations or interviews.33 Although the burden of proof and identification of the perpetrator(s) lie with professional investigators, determination of the cause or possible causes of a child’s injury is often critical to the legal case. Specialists in child abuse, often teamed with a forensically trained interviewer to obtain a specialized history from the child who is verbal, are trained to provide the expert opinions required by the court.

Like referral options, follow-up will depend on the type of abuse that a child has experienced. Medical follow-up, as in the child in the case study, may involve orthopedists, ophthalmologists, or clinicians in other relevant specialties. A psychologist may manage counseling services for the patient and family or foster family.

A SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Recognition of child abuse is the first step to prevent further victimization. Comprehensive education is critical for health care providers, school nurses, teachers, or anyone who comes into contact with children on a daily basis; increased awareness has been universally identified as a means to prevent child abuse. It is also imperative to educate legislators regarding the extent of this problem and to garner their support for community prevention programs.

For the primary care clinician, it is unfortunate but true that a high level of suspicion for abuse must be maintained; the best available screening tools are the astute clinician’s eyes and brain. During routine annual exams, children should be observed for any indication of abuse, and their interactions with parents should be evaluated as well. Anticipatory guidance during well-child visits has been found to help build parents’ trust in the clinician’s knowledge and compassion, increasing their adherence to effective advice and improving their parenting behavior.40

Public policies and social programs can effectively enhance family functioning, playing a key role in the protection of children.41 Existing research into the causes and effects of child abuse should be used to formulate preventive programs for schools, churches, and local health care providers.

CONCLUSION

No recipe exists for the prevention of child abuse. Health care providers must not hesitate to report suspicion of abuse. This action does not always lead to removal of children from their homes; rather, involving families and children in “the system” can give them access to services of which they might otherwise remain unaware. Home visits, anger management programs, parenting classes, counseling services, and early childhood education can instill and reinforce more positive attitudes and action, for the benefit of all involved.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment 2009 (2010). www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/pubs/cm09. Accessed February 22, 2012.

2. UNICEF Child Protection Strategy (2008). www .unrol.org/files/CP%20Strategy_English.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

3. World Health Organization. Child maltreatment: Fact Sheet #150, August 2010. www.who .int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs150/en/index.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

4. World Health Organization. Preventing Child Maltreatment: A Guide to Taking Action and Generating Evidence. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publi cations/2006/9241594365_eng.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

5. Giardino AP. Child maltreatment: is the glass half full yet? J Forensic Nurs. 2009;5(1):1-4.

6. Barriere D. Child abuse: history, laws and the ASPCA (2005). www.resourcesforattorneys.com/childabuseandtheaspcaarticle.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

7. The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, Including Adoption Opportunities and the Abandoned Infants Assistance Act, as Amended by the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003. www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/laws_policies/cblaws/capta03/capta_manual.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

8. H.R. 14: Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003. www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd ?bill=h108-14&tab=summary. Accessed February 22, 2012.

9. S. 3817: CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010. www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=s

111-3817. Accessed February 22, 2012.

10. National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect. NCANDS State Level Data 2009: National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System. www .ndacan.cornell.edu/cmrlpostings/msg00195.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

11. Finkelhor D, Jones L, Shattuck A; Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire. Updated trends in child maltreatment, 2009. http://unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/Updated_Trends_in_Child_Maltreatment_2009.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

12. CDC Injury Center: Violence Prevention. Child Maltreatment: Risk and Protective Factors (2011). www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childmaltreat ment/riskprotectivefactors.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

13. Sullivan P, Knutson J. Maltreatment and disabilities: a population-based epidemiological study. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(10):1257-1273.

14. Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, et al. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress, Executive Summary. January 2010. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.

15. National Clearinghouse on Family Violence, Public Health Agency of Canada. Abuse of children with disabilities (2000). www.phac-aspc

.gc.ca/ncfv-cnivf/pdfs/nfnts-disabl-eng.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

16. Endorm EE. (2011, June 7, 2011). Physical abuse in children: epidemiology and clinical manifestations. www.uptodate.com/contents/physical-abuse-in-children-epidemiology-and-clinical-manifestations?source=search_result&

search=Phsical+abuse+i+children%3A+Epidemiology+and+clinical+manifestations&selectedTi

tle=1~150. Accessed February 22, 2012.

17. Pandya NK, Baldwin K, Kamath AF, et al. Unexplained fractures: child abuse or bone disease? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011; 469(3):805-812.

18. Gondim RM, Muñoz DR, Petri V. Child abuse: skin markers and differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(3):527-536.

19. Kemp AM, Dunstan F, Harrison S, et al. Patterns of skeletal fractures in child abuse: systematic review. BMJ. 2008;337:a1518.

20. Worlock P, Stower M, Barbor P. Patterns of fractures in accidental and non-accidental injury in children: a comparative study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293(6539):100-102.

21. Welsh Child Protection Systematic Review Group. www.core-info.cf.ac.uk. Accessed February 22, 2012.

22. Wardinsky TD. Genetic and congenital defect conditions that mimic child abuse. J Fam Pract. 1995;41(4):377-383.

23. American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria (2009). www.acr.org/SecondaryMainMenuCategories/quality_safety/app_criteria/pdf/ExpertPanelonPediatricImaging/Suspected PhysicalAbuseChildDoc9.aspx. Accessed February 22, 2012.

24. Meservy CJ, Towbin R, McLaurin RL, et al. Radiographic characteristics of skull fractures resulting from child abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149(1):173-175.

25. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Burn Injuries in Child Abuse (2001). www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/91190-6.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

26. Lane WG, Dubowitz H. Primary care pediatricians’ experience, comfort and competence in the evaluation and management of child maltreatment: do we need child abuse experts? Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(2):76-83.

27. Child Welfare Information Gateway, US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Recognizing child abuse and neglect: signs and symptoms (2007). www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/signs.cfm. Accessed February 22, 2012.

28. Fortin K, Jenny C. Sexual abuse. Pediatr Rev. 2012;33(1):19–32.

29. Keshavarz R, Kawashima R, Low C. Child abuse and neglect presentations to a pediatric emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2002;23(4): 341-345.

30. Kellogg N; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of sexual abuse in children. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):506-512.

31. Heger A, Ticson L, Velasquez O, Bernier R. Children referred for possible sexual abuse: medical findings in 2384 children. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26(6-7):645-659.

32. Kellogg ND, Menard SW, Santos A. Genital anatomy in pregnant adolescents: “normal” does not mean “nothing happened.” Pediatrics. 2004; 113(1):e67-e69.

33. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

34. Oates RK. Overturning the diagnosis of child abuse. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59(7):665-666.

35. Hornor G. Common conditions that mimic findings of sexual abuse. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23(5):283-288.

36. Asnes RS. Buttock bruises: Mongolian spot. Pediatrics. 1984;74(2):321.

37. Klusmann A, Lenard HG. Tourniquet syndrome: accident or abuse? Eur J Pediatr. 2004; 163(8):495-498.

38. Merten DF, Carpenter BL. Radiologic imaging of inflicted injury in the child abuse syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1990;37(4):815-837.

39. Mok JY. Non-accidental injury in children: an update. Injury. 2008;39(9):978-985.

40. Nelson CS, Higman SM, Sia C, et al. Medical homes for at-risk children: parental reports of clinician-parent relationships, anticipatory guidance, and behavior changes. Pediatrics. 2005; 115(1):48-56.

41. Dubowitz H. Prevention of child maltreatment: what is known. Pediatrics. 1989;83(4):570-577.

According to data from the US Department of Health and Human Services, child protection services received more than 3.3 million reports of alleged maltreatment in 2009 that involved about six million children, and about 62% of reports required subsequent action.1 Child abuse is an ever-growing problem that affects children of both genders and in all ages, races, and socioeconomic levels. Few issues generate the concern, anger, and frustration as the abuse or neglect of children.

Primary care providers and emergency department personnel are often the child’s initial point of entry into the health care system. Clinicians who see and treat young patients can play an essential role in the recognition and reporting of child abuse. By frequently reviewing the risk factors for child abuse, its signs and symptoms, and its typical and atypical presentations, clinicians can be prepared to act when appropriate and help break the cycle of child abuse.

LEGAL MANDATES, DEFINITIONS

A relatively new concept, child abuse has been designated as a major public health issue by the United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization.2-5 In 1874, when it was decided by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) to include children within the defined animal kingdom, the movement to protect children began in the United States.6

Both federal and state agencies have created definitions for child abuse and neglect. The key federal legislation to address child abuse and neglect, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), as Amended by the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003,7,8 defines child abuse and neglect as “any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation, or an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.”7 Although ongoing revisions of the CAPTA legislation (the most recent “reauthorization” published in 20109) become increasingly inclusive of both children’s and families’ concerns, this definition has remained consistent.

This is not the case with state definitions, however. Because these vary, it can be difficult to compare rates of reported maltreatment from state to state. Also varying among states, and among counties within some states, are recommendations for substantiation of child maltreatment. The validity of the reported data can be impaired by a lack of coordination or cooperation among different agencies and jurisdictions.

IDENTIFYING THE VICTIMS

The spectrum of child abuse includes multiple forms, which often overlap (see Table 11,9,10), and can almost always have the potential for death.11 According to findings from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, despite worsening economic conditions in 2009, the child maltreatment data compiled that year showed an overall 2% decline in cases of substantiated maltreatment from the previous year.1,11

However, during that same period, child maltreatment–associated fatalities rose 3%, from 1,628 deaths in 2008 to 1,671 in 2009,1 suggesting an increase in the severity of abuse. The emotional, social, and financial ramifications of child abuse affect the local and national community, as well as each child and each family.

Children younger than 1 year, the most vulnerable to maltreatment, represent the largest proportion of substantiated abuse. One-third of all children reported as abused in 2009 were younger than 4, and children between ages 4 and 7 represented one-fifth of cases.1 Figure 1a1 categorizes the incidence of child abuse by age level, and Figure 1b1 by ethnicity/race.

Risk Factors

A number of factors, though not necessarily direct causes, have been shown to increase children’s risk for abuse or neglect. These include personal characteristics of the child and parent, and family- or environment-related factors1,12 (see Table 2,1). It is often combinations of risk factors (eg, characteristics of a parent or caregiver in addition to a specific social environment) that are most likely to increase the likelihood of abuse.

Children with special needs (physical disabilities or chronic illness, neurologic impairment, mental health issues) that increase the caregiver’s burden are at increased risk for abuse.1,12 Children with behavior disorders and mental retardation have been found at increased risk for various forms of abuse—neglect and physical or sexual maltreatment13—whereas children with speech or language disabilities are at increased risk for neglect (whether physical, emotional, or even educational14).

Children with physical limitations who experience physical abuse are reportedly subject to more serious injury than their healthier counterparts.14 Their inability to see, hear, move, or communicate, or to dress or bathe themselves independently may make them susceptible to rough, careless, or intrusive personal care, or neglect of their personal needs. Low self-esteem, whatever its cause, also appears to be a significant risk factor for intentional abuse.15

It is often the case that children with disabilities do not report abuse because they are unable to recognize an act as abusive. Depending on the severity of a child’s disability and his or her ordinarily atypical presentation, the abuse may never be discovered.15

Poverty appears to be a contributing factor. Children from families of low socioeconomic status are at least three times as likely as other children to be abused and seven times as likely to experience neglect.14 It has been conjectured that these children are more likely to have contact with social workers, law enforcement officers, and representatives of other agencies with an increased awareness of the manifestations of child abuse. Abuse within affluent families may be underreported, as such families have the wherewithal to protect themselves from detection and prosecution.16

PRESENTATION

There is no “gold standard” for making a confirmed diagnosis of child abuse,17 and no “typical” presentation of an abused child (see case study). Dress that is inappropriate for the season and consistently poor hygiene are indicative of neglect. Symptoms of abuse may be overt or silent, and signs of physical abuse are often hidden beneath clothing. Children who are physically abused often explain their injuries by saying “I fell,” or may even respond to questioning by saying, “I don’t know.” The parent or caregiver may attribute bruises or even broken bones to falls or rough play with other children. Bruises, the most common visible form of child abuse,18 may suggest the nature of injury by their location, patterns, and various stages of healing.

Fractures are the second most common presenting symptom among children experiencing physical abuse.17 According to findings from a meta-analysis by Kemp et al,19 determining whether fractures have occurred accidentally depends on three factors:

Age. Among children younger than 1 year, 25% to 56% of fractures are attributable to intentional harm. In one landmark study, one fracture in nine was found to have resulted from abuse, among children younger than 18 months—compared with one in 205 among children ages 19 months to 5 years.19,20

Site. In cases not involving a motor vehicle accident or other traumatic event, it has been determined in ongoing systematic reviews by Welsh researchers that rib fractures have a 71% probability of being inflicted, followed by humeral fractures (about 50% probability), then by femoral fractures or skull fractures (about 33% probability).19,21

Fracture type. Fracture types suggestive of abuse differ by site. Among humeral fractures, for example, a midshaft fracture is more likely to have been inflicted, whereas a supracondylar fracture is more likely the result of accidental injury. Both parietal and linear skull fractures may occur accidentally or through physical abuse.19 Epiphyseal-metaphyseal fractures, vertebral compression fractures, and lateral clavicle fractures have been associated with child abuse.22,23 Multiple or bilateral fractures have an increased association with abuse.19,20,24

Injuries that are inconsistent with the given history should raise red flags, and they should be carefully investigated, with findings documented. Minor falls cause minor injuries, not potentially life-threatening ones.

As with fractures, burns may have specific features that help the clinician distinguish between accidental and intentional. Uniform depth, well-defined edges, and multiple lesions are more likely to indicate nonaccidental contact burns, particularly when found in “protected” sites (eg, perineal and gluteal areas).18 Accidental cigarette burns are usually ovoid or irregular in shape and superficial, while those intentionally inflicted are round, deep, and well-demarcated and are often grouped on the hands, feet, or face.18,25 Burns on the chest, upper limbs, and palms of the hands are likely to be accidental; the face, the backs of the hands, the lower stomach, back, buttocks, legs, and feet are often the target of intentional burns.18,26

HISTORY

A key factor in suspected abuse is the child’s history. During history taking, clinicians should be alert to the evidence-based indicators of potential child abuse, as shown in Table 327-29. Not every child who exhibits these characteristics is an abused child, nor will every abused child exhibit any or all of these characteristics. Through artful, careful history taking and astute observation of the child, the clinician is usually able to distinguish between the heightened anxiety that may occur in any child during the history-taking process and the demeanor of a child who may have been coerced or threatened to maintain secrecy.

Engaging the child in a reassuring manner, the clinician can use a conversational style of questioning, such as, “Tell me how you got that bruise on your arm,” rather than a direct question: “Did [name] hit you on the arm with [his/her] fist?”

An observation of unusually sexualized behaviors or a report of excessive masturbation is more likely to be associated with sexual abuse than are genital findings (which are infrequently found).

Physical Examination

When a child presents with an acute injury or bruising is detected and the clinician’s findings are inconsistent with the given history, suspicion should be raised. The injuries inflicted by physical abuse are often hidden beneath the child’s clothing (specifically, underwear); for this reason, it is important to have children undressed during a physical exam.

The routine physical exam of an abused child may reveal defensive bruising or other wounds, trauma to the mouth, breasts, buttocks, genitalia, or anus, with possible bleeding or discharge. More commonly, the physical exam findings are normal—as is true in the majority of examinations for sexual abuse.30 In one large study, abnormal findings (eg, recent or healed genital injuries; presence of a sexually transmitted disease) were found in only about 4% of children who had been referred for an examination for suspected sexual abuse.18,31 Clearly, an appearance of “normal” does not mean “nothing happened.”32

According to CDC guidelines,33 investigation of suspected sexual abuse (for example, when a genital herpes infection is detected) should be conducted by appropriately trained, experienced clinicians—ideally, by a pediatric subspecialist in child abuse. Although the primary care clinician may examine the child briefly for visible bruises or wounds, it is essential for a specialist to perform the genital exam.33 Use of mild sedation with close monitoring may be advisable during the genital examination.30

Mimics of Child Abuse

Several conditions, including metabolic, genetic, and congenital disorders, have been reported to mimic the physical manifestations of child abuse and neglect17,22,34 (see Table 4,17,18,22,25,33-35). While health care professionals are legally and ethically bound to report abuse, conditions that may mimic abuse must be ruled out first, to avoid the mistaken removal of children from loving homes.

Mongolian spots, for example (see Figure 2), are frequently mistaken for bruising and reported to authorities, causing unnecessary disruption for both family and child.34,36 They typically appear as macular blue-gray pigmentation of the skin, usually on the sacrum. Resulting from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during fetal development, these “spots” may be present at birth or may appear during the neonatal period. Mongolian spots are most common in Native American, African-American, Asian, and Hispanic patients, are benign, and often disappear by age 4.

Other cutaneous manifestations that can mimic an intentional injury include molluscum contagiosum, a viral infection manifesting as a rash that may mimic the genital warts of human papillomavirus, and erythematous, edematous, and/or vesiculobullous lesions18,35 (see Figure 3). Severe diaper rash, photodermatitis, and certain allergic reactions can mimic intentional burns.25

Often mistaken for a nonaccidental injury is hair tourniquet syndrome—the circumferential strangulation of one or more appendages (eg, finger, toe, penis) by human hair or fibers.34 This uncommon condition, usually unintentional and of unknown incidence, can represent a surgical emergency; failure to recognize it in a timely fashion may lead to ischemia or necrosis, necessitating amputation of the affected appendage.37

Metabolic bone disease, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, can sometimes explain frequent fractures.17

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

In the primary care setting, the detection of child abuse is unexpected. However, it is often here that children are initially seen for an injury, or suspicions are raised during a routine physical.30 In the case of spontaneous disclosure of abuse, explicit, word-for-word documentation is required. The child, who may feel guilty, embarrassed, or ashamed, must be reassured that he or she is not at fault.

Either a child abuse specialist or the primary care clinician bases the ultimate diagnosis of child abuse on findings from the history and physical examination. These findings will direct the clinician’s decision to order diagnostic laboratory studies and/or diagnostic x-rays.

Diagnostic Studies

Depending on the child’s age and the type of presentation, recommended imaging studies include an x-ray skeletal survey of a child younger than 2 (see “Skeletal Survey Reading of 5-Month-Old Boy,”) or an older child with thoracoabdominal injuries that the history does not explain satisfactorily.23 For children ages 2 to 5, focused plain films of the area of suspected injury (eg, skull, chest, extremities) are considered appropriate.23,38

Noncontrast head CT may be appropriate in the presence of skull fractures, (as in Figures 4a and 4b) intracranial injuries, seizures, or other neurologic signs and symptoms (followed by MRI if further assessment is needed). CT with contrast may be considered when x-rays reveal certain abnormalities, the child is considered at high risk for abuse (for example, when inconsistencies are found in the history), or when soft-tissue injuries are suspected.23,39

About 5% of sexually abused children contract a sexually transmitted disease.30 Appropriate laboratory tests that can be performed in the office setting include:

- Urinalysis for presence of semen

- Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) for chlamydia and gonorrhea (with positive results requiring that sexual abuse be considered in children beyond neonatal age, according to CDC guidelines33); anorectal and pharyngeal infections with Neisseria gonorrhoeae are commonly found in sexually abused children

- Serologic testing for HIV33

- Urine pregnancy testing in patients of childbearing age.

As these lab specimens are collected, chain of custody must be maintained. Results may be used as evidence in the event of prosecution.

REFERRALS AND FOLLOW-UP

What referrals are made—to clinical specialists, law enforcement, social services, and other agencies—is based on the nature of the abuse, the dynamics of the family involved, the identity of the alleged perpetrator, and the perceived need to ensure the child’s safety. It is the role of these interrelated agencies to confirm the child’s diagnosis, provide for the child’s immediate safety, and ensure links within the systems involved to follow him or her into adulthood, if necessary.

Timely referral to specialized clinicians may spare the child from having to undergo multiple examinations or interviews.33 Although the burden of proof and identification of the perpetrator(s) lie with professional investigators, determination of the cause or possible causes of a child’s injury is often critical to the legal case. Specialists in child abuse, often teamed with a forensically trained interviewer to obtain a specialized history from the child who is verbal, are trained to provide the expert opinions required by the court.

Like referral options, follow-up will depend on the type of abuse that a child has experienced. Medical follow-up, as in the child in the case study, may involve orthopedists, ophthalmologists, or clinicians in other relevant specialties. A psychologist may manage counseling services for the patient and family or foster family.

A SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Recognition of child abuse is the first step to prevent further victimization. Comprehensive education is critical for health care providers, school nurses, teachers, or anyone who comes into contact with children on a daily basis; increased awareness has been universally identified as a means to prevent child abuse. It is also imperative to educate legislators regarding the extent of this problem and to garner their support for community prevention programs.

For the primary care clinician, it is unfortunate but true that a high level of suspicion for abuse must be maintained; the best available screening tools are the astute clinician’s eyes and brain. During routine annual exams, children should be observed for any indication of abuse, and their interactions with parents should be evaluated as well. Anticipatory guidance during well-child visits has been found to help build parents’ trust in the clinician’s knowledge and compassion, increasing their adherence to effective advice and improving their parenting behavior.40

Public policies and social programs can effectively enhance family functioning, playing a key role in the protection of children.41 Existing research into the causes and effects of child abuse should be used to formulate preventive programs for schools, churches, and local health care providers.

CONCLUSION

No recipe exists for the prevention of child abuse. Health care providers must not hesitate to report suspicion of abuse. This action does not always lead to removal of children from their homes; rather, involving families and children in “the system” can give them access to services of which they might otherwise remain unaware. Home visits, anger management programs, parenting classes, counseling services, and early childhood education can instill and reinforce more positive attitudes and action, for the benefit of all involved.

According to data from the US Department of Health and Human Services, child protection services received more than 3.3 million reports of alleged maltreatment in 2009 that involved about six million children, and about 62% of reports required subsequent action.1 Child abuse is an ever-growing problem that affects children of both genders and in all ages, races, and socioeconomic levels. Few issues generate the concern, anger, and frustration as the abuse or neglect of children.

Primary care providers and emergency department personnel are often the child’s initial point of entry into the health care system. Clinicians who see and treat young patients can play an essential role in the recognition and reporting of child abuse. By frequently reviewing the risk factors for child abuse, its signs and symptoms, and its typical and atypical presentations, clinicians can be prepared to act when appropriate and help break the cycle of child abuse.

LEGAL MANDATES, DEFINITIONS

A relatively new concept, child abuse has been designated as a major public health issue by the United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization.2-5 In 1874, when it was decided by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) to include children within the defined animal kingdom, the movement to protect children began in the United States.6

Both federal and state agencies have created definitions for child abuse and neglect. The key federal legislation to address child abuse and neglect, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), as Amended by the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003,7,8 defines child abuse and neglect as “any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation, or an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.”7 Although ongoing revisions of the CAPTA legislation (the most recent “reauthorization” published in 20109) become increasingly inclusive of both children’s and families’ concerns, this definition has remained consistent.

This is not the case with state definitions, however. Because these vary, it can be difficult to compare rates of reported maltreatment from state to state. Also varying among states, and among counties within some states, are recommendations for substantiation of child maltreatment. The validity of the reported data can be impaired by a lack of coordination or cooperation among different agencies and jurisdictions.

IDENTIFYING THE VICTIMS

The spectrum of child abuse includes multiple forms, which often overlap (see Table 11,9,10), and can almost always have the potential for death.11 According to findings from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, despite worsening economic conditions in 2009, the child maltreatment data compiled that year showed an overall 2% decline in cases of substantiated maltreatment from the previous year.1,11

However, during that same period, child maltreatment–associated fatalities rose 3%, from 1,628 deaths in 2008 to 1,671 in 2009,1 suggesting an increase in the severity of abuse. The emotional, social, and financial ramifications of child abuse affect the local and national community, as well as each child and each family.

Children younger than 1 year, the most vulnerable to maltreatment, represent the largest proportion of substantiated abuse. One-third of all children reported as abused in 2009 were younger than 4, and children between ages 4 and 7 represented one-fifth of cases.1 Figure 1a1 categorizes the incidence of child abuse by age level, and Figure 1b1 by ethnicity/race.

Risk Factors

A number of factors, though not necessarily direct causes, have been shown to increase children’s risk for abuse or neglect. These include personal characteristics of the child and parent, and family- or environment-related factors1,12 (see Table 2,1). It is often combinations of risk factors (eg, characteristics of a parent or caregiver in addition to a specific social environment) that are most likely to increase the likelihood of abuse.

Children with special needs (physical disabilities or chronic illness, neurologic impairment, mental health issues) that increase the caregiver’s burden are at increased risk for abuse.1,12 Children with behavior disorders and mental retardation have been found at increased risk for various forms of abuse—neglect and physical or sexual maltreatment13—whereas children with speech or language disabilities are at increased risk for neglect (whether physical, emotional, or even educational14).

Children with physical limitations who experience physical abuse are reportedly subject to more serious injury than their healthier counterparts.14 Their inability to see, hear, move, or communicate, or to dress or bathe themselves independently may make them susceptible to rough, careless, or intrusive personal care, or neglect of their personal needs. Low self-esteem, whatever its cause, also appears to be a significant risk factor for intentional abuse.15

It is often the case that children with disabilities do not report abuse because they are unable to recognize an act as abusive. Depending on the severity of a child’s disability and his or her ordinarily atypical presentation, the abuse may never be discovered.15

Poverty appears to be a contributing factor. Children from families of low socioeconomic status are at least three times as likely as other children to be abused and seven times as likely to experience neglect.14 It has been conjectured that these children are more likely to have contact with social workers, law enforcement officers, and representatives of other agencies with an increased awareness of the manifestations of child abuse. Abuse within affluent families may be underreported, as such families have the wherewithal to protect themselves from detection and prosecution.16

PRESENTATION

There is no “gold standard” for making a confirmed diagnosis of child abuse,17 and no “typical” presentation of an abused child (see case study). Dress that is inappropriate for the season and consistently poor hygiene are indicative of neglect. Symptoms of abuse may be overt or silent, and signs of physical abuse are often hidden beneath clothing. Children who are physically abused often explain their injuries by saying “I fell,” or may even respond to questioning by saying, “I don’t know.” The parent or caregiver may attribute bruises or even broken bones to falls or rough play with other children. Bruises, the most common visible form of child abuse,18 may suggest the nature of injury by their location, patterns, and various stages of healing.

Fractures are the second most common presenting symptom among children experiencing physical abuse.17 According to findings from a meta-analysis by Kemp et al,19 determining whether fractures have occurred accidentally depends on three factors:

Age. Among children younger than 1 year, 25% to 56% of fractures are attributable to intentional harm. In one landmark study, one fracture in nine was found to have resulted from abuse, among children younger than 18 months—compared with one in 205 among children ages 19 months to 5 years.19,20

Site. In cases not involving a motor vehicle accident or other traumatic event, it has been determined in ongoing systematic reviews by Welsh researchers that rib fractures have a 71% probability of being inflicted, followed by humeral fractures (about 50% probability), then by femoral fractures or skull fractures (about 33% probability).19,21

Fracture type. Fracture types suggestive of abuse differ by site. Among humeral fractures, for example, a midshaft fracture is more likely to have been inflicted, whereas a supracondylar fracture is more likely the result of accidental injury. Both parietal and linear skull fractures may occur accidentally or through physical abuse.19 Epiphyseal-metaphyseal fractures, vertebral compression fractures, and lateral clavicle fractures have been associated with child abuse.22,23 Multiple or bilateral fractures have an increased association with abuse.19,20,24

Injuries that are inconsistent with the given history should raise red flags, and they should be carefully investigated, with findings documented. Minor falls cause minor injuries, not potentially life-threatening ones.

As with fractures, burns may have specific features that help the clinician distinguish between accidental and intentional. Uniform depth, well-defined edges, and multiple lesions are more likely to indicate nonaccidental contact burns, particularly when found in “protected” sites (eg, perineal and gluteal areas).18 Accidental cigarette burns are usually ovoid or irregular in shape and superficial, while those intentionally inflicted are round, deep, and well-demarcated and are often grouped on the hands, feet, or face.18,25 Burns on the chest, upper limbs, and palms of the hands are likely to be accidental; the face, the backs of the hands, the lower stomach, back, buttocks, legs, and feet are often the target of intentional burns.18,26

HISTORY

A key factor in suspected abuse is the child’s history. During history taking, clinicians should be alert to the evidence-based indicators of potential child abuse, as shown in Table 327-29. Not every child who exhibits these characteristics is an abused child, nor will every abused child exhibit any or all of these characteristics. Through artful, careful history taking and astute observation of the child, the clinician is usually able to distinguish between the heightened anxiety that may occur in any child during the history-taking process and the demeanor of a child who may have been coerced or threatened to maintain secrecy.

Engaging the child in a reassuring manner, the clinician can use a conversational style of questioning, such as, “Tell me how you got that bruise on your arm,” rather than a direct question: “Did [name] hit you on the arm with [his/her] fist?”

An observation of unusually sexualized behaviors or a report of excessive masturbation is more likely to be associated with sexual abuse than are genital findings (which are infrequently found).

Physical Examination

When a child presents with an acute injury or bruising is detected and the clinician’s findings are inconsistent with the given history, suspicion should be raised. The injuries inflicted by physical abuse are often hidden beneath the child’s clothing (specifically, underwear); for this reason, it is important to have children undressed during a physical exam.

The routine physical exam of an abused child may reveal defensive bruising or other wounds, trauma to the mouth, breasts, buttocks, genitalia, or anus, with possible bleeding or discharge. More commonly, the physical exam findings are normal—as is true in the majority of examinations for sexual abuse.30 In one large study, abnormal findings (eg, recent or healed genital injuries; presence of a sexually transmitted disease) were found in only about 4% of children who had been referred for an examination for suspected sexual abuse.18,31 Clearly, an appearance of “normal” does not mean “nothing happened.”32

According to CDC guidelines,33 investigation of suspected sexual abuse (for example, when a genital herpes infection is detected) should be conducted by appropriately trained, experienced clinicians—ideally, by a pediatric subspecialist in child abuse. Although the primary care clinician may examine the child briefly for visible bruises or wounds, it is essential for a specialist to perform the genital exam.33 Use of mild sedation with close monitoring may be advisable during the genital examination.30

Mimics of Child Abuse

Several conditions, including metabolic, genetic, and congenital disorders, have been reported to mimic the physical manifestations of child abuse and neglect17,22,34 (see Table 4,17,18,22,25,33-35). While health care professionals are legally and ethically bound to report abuse, conditions that may mimic abuse must be ruled out first, to avoid the mistaken removal of children from loving homes.

Mongolian spots, for example (see Figure 2), are frequently mistaken for bruising and reported to authorities, causing unnecessary disruption for both family and child.34,36 They typically appear as macular blue-gray pigmentation of the skin, usually on the sacrum. Resulting from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during fetal development, these “spots” may be present at birth or may appear during the neonatal period. Mongolian spots are most common in Native American, African-American, Asian, and Hispanic patients, are benign, and often disappear by age 4.

Other cutaneous manifestations that can mimic an intentional injury include molluscum contagiosum, a viral infection manifesting as a rash that may mimic the genital warts of human papillomavirus, and erythematous, edematous, and/or vesiculobullous lesions18,35 (see Figure 3). Severe diaper rash, photodermatitis, and certain allergic reactions can mimic intentional burns.25

Often mistaken for a nonaccidental injury is hair tourniquet syndrome—the circumferential strangulation of one or more appendages (eg, finger, toe, penis) by human hair or fibers.34 This uncommon condition, usually unintentional and of unknown incidence, can represent a surgical emergency; failure to recognize it in a timely fashion may lead to ischemia or necrosis, necessitating amputation of the affected appendage.37

Metabolic bone disease, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, can sometimes explain frequent fractures.17

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

In the primary care setting, the detection of child abuse is unexpected. However, it is often here that children are initially seen for an injury, or suspicions are raised during a routine physical.30 In the case of spontaneous disclosure of abuse, explicit, word-for-word documentation is required. The child, who may feel guilty, embarrassed, or ashamed, must be reassured that he or she is not at fault.

Either a child abuse specialist or the primary care clinician bases the ultimate diagnosis of child abuse on findings from the history and physical examination. These findings will direct the clinician’s decision to order diagnostic laboratory studies and/or diagnostic x-rays.

Diagnostic Studies

Depending on the child’s age and the type of presentation, recommended imaging studies include an x-ray skeletal survey of a child younger than 2 (see “Skeletal Survey Reading of 5-Month-Old Boy,”) or an older child with thoracoabdominal injuries that the history does not explain satisfactorily.23 For children ages 2 to 5, focused plain films of the area of suspected injury (eg, skull, chest, extremities) are considered appropriate.23,38

Noncontrast head CT may be appropriate in the presence of skull fractures, (as in Figures 4a and 4b) intracranial injuries, seizures, or other neurologic signs and symptoms (followed by MRI if further assessment is needed). CT with contrast may be considered when x-rays reveal certain abnormalities, the child is considered at high risk for abuse (for example, when inconsistencies are found in the history), or when soft-tissue injuries are suspected.23,39

About 5% of sexually abused children contract a sexually transmitted disease.30 Appropriate laboratory tests that can be performed in the office setting include:

- Urinalysis for presence of semen

- Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) for chlamydia and gonorrhea (with positive results requiring that sexual abuse be considered in children beyond neonatal age, according to CDC guidelines33); anorectal and pharyngeal infections with Neisseria gonorrhoeae are commonly found in sexually abused children

- Serologic testing for HIV33

- Urine pregnancy testing in patients of childbearing age.

As these lab specimens are collected, chain of custody must be maintained. Results may be used as evidence in the event of prosecution.

REFERRALS AND FOLLOW-UP

What referrals are made—to clinical specialists, law enforcement, social services, and other agencies—is based on the nature of the abuse, the dynamics of the family involved, the identity of the alleged perpetrator, and the perceived need to ensure the child’s safety. It is the role of these interrelated agencies to confirm the child’s diagnosis, provide for the child’s immediate safety, and ensure links within the systems involved to follow him or her into adulthood, if necessary.

Timely referral to specialized clinicians may spare the child from having to undergo multiple examinations or interviews.33 Although the burden of proof and identification of the perpetrator(s) lie with professional investigators, determination of the cause or possible causes of a child’s injury is often critical to the legal case. Specialists in child abuse, often teamed with a forensically trained interviewer to obtain a specialized history from the child who is verbal, are trained to provide the expert opinions required by the court.

Like referral options, follow-up will depend on the type of abuse that a child has experienced. Medical follow-up, as in the child in the case study, may involve orthopedists, ophthalmologists, or clinicians in other relevant specialties. A psychologist may manage counseling services for the patient and family or foster family.

A SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Recognition of child abuse is the first step to prevent further victimization. Comprehensive education is critical for health care providers, school nurses, teachers, or anyone who comes into contact with children on a daily basis; increased awareness has been universally identified as a means to prevent child abuse. It is also imperative to educate legislators regarding the extent of this problem and to garner their support for community prevention programs.

For the primary care clinician, it is unfortunate but true that a high level of suspicion for abuse must be maintained; the best available screening tools are the astute clinician’s eyes and brain. During routine annual exams, children should be observed for any indication of abuse, and their interactions with parents should be evaluated as well. Anticipatory guidance during well-child visits has been found to help build parents’ trust in the clinician’s knowledge and compassion, increasing their adherence to effective advice and improving their parenting behavior.40

Public policies and social programs can effectively enhance family functioning, playing a key role in the protection of children.41 Existing research into the causes and effects of child abuse should be used to formulate preventive programs for schools, churches, and local health care providers.

CONCLUSION

No recipe exists for the prevention of child abuse. Health care providers must not hesitate to report suspicion of abuse. This action does not always lead to removal of children from their homes; rather, involving families and children in “the system” can give them access to services of which they might otherwise remain unaware. Home visits, anger management programs, parenting classes, counseling services, and early childhood education can instill and reinforce more positive attitudes and action, for the benefit of all involved.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment 2009 (2010). www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/pubs/cm09. Accessed February 22, 2012.

2. UNICEF Child Protection Strategy (2008). www .unrol.org/files/CP%20Strategy_English.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

3. World Health Organization. Child maltreatment: Fact Sheet #150, August 2010. www.who .int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs150/en/index.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

4. World Health Organization. Preventing Child Maltreatment: A Guide to Taking Action and Generating Evidence. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publi cations/2006/9241594365_eng.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

5. Giardino AP. Child maltreatment: is the glass half full yet? J Forensic Nurs. 2009;5(1):1-4.

6. Barriere D. Child abuse: history, laws and the ASPCA (2005). www.resourcesforattorneys.com/childabuseandtheaspcaarticle.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

7. The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, Including Adoption Opportunities and the Abandoned Infants Assistance Act, as Amended by the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003. www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/laws_policies/cblaws/capta03/capta_manual.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

8. H.R. 14: Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003. www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd ?bill=h108-14&tab=summary. Accessed February 22, 2012.

9. S. 3817: CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010. www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=s

111-3817. Accessed February 22, 2012.

10. National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect. NCANDS State Level Data 2009: National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System. www .ndacan.cornell.edu/cmrlpostings/msg00195.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

11. Finkelhor D, Jones L, Shattuck A; Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire. Updated trends in child maltreatment, 2009. http://unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/Updated_Trends_in_Child_Maltreatment_2009.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

12. CDC Injury Center: Violence Prevention. Child Maltreatment: Risk and Protective Factors (2011). www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childmaltreat ment/riskprotectivefactors.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

13. Sullivan P, Knutson J. Maltreatment and disabilities: a population-based epidemiological study. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(10):1257-1273.

14. Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, et al. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress, Executive Summary. January 2010. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.

15. National Clearinghouse on Family Violence, Public Health Agency of Canada. Abuse of children with disabilities (2000). www.phac-aspc

.gc.ca/ncfv-cnivf/pdfs/nfnts-disabl-eng.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

16. Endorm EE. (2011, June 7, 2011). Physical abuse in children: epidemiology and clinical manifestations. www.uptodate.com/contents/physical-abuse-in-children-epidemiology-and-clinical-manifestations?source=search_result&

search=Phsical+abuse+i+children%3A+Epidemiology+and+clinical+manifestations&selectedTi

tle=1~150. Accessed February 22, 2012.

17. Pandya NK, Baldwin K, Kamath AF, et al. Unexplained fractures: child abuse or bone disease? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011; 469(3):805-812.

18. Gondim RM, Muñoz DR, Petri V. Child abuse: skin markers and differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(3):527-536.

19. Kemp AM, Dunstan F, Harrison S, et al. Patterns of skeletal fractures in child abuse: systematic review. BMJ. 2008;337:a1518.

20. Worlock P, Stower M, Barbor P. Patterns of fractures in accidental and non-accidental injury in children: a comparative study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293(6539):100-102.

21. Welsh Child Protection Systematic Review Group. www.core-info.cf.ac.uk. Accessed February 22, 2012.

22. Wardinsky TD. Genetic and congenital defect conditions that mimic child abuse. J Fam Pract. 1995;41(4):377-383.

23. American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria (2009). www.acr.org/SecondaryMainMenuCategories/quality_safety/app_criteria/pdf/ExpertPanelonPediatricImaging/Suspected PhysicalAbuseChildDoc9.aspx. Accessed February 22, 2012.

24. Meservy CJ, Towbin R, McLaurin RL, et al. Radiographic characteristics of skull fractures resulting from child abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149(1):173-175.

25. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Burn Injuries in Child Abuse (2001). www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/91190-6.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

26. Lane WG, Dubowitz H. Primary care pediatricians’ experience, comfort and competence in the evaluation and management of child maltreatment: do we need child abuse experts? Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(2):76-83.

27. Child Welfare Information Gateway, US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Recognizing child abuse and neglect: signs and symptoms (2007). www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/signs.cfm. Accessed February 22, 2012.

28. Fortin K, Jenny C. Sexual abuse. Pediatr Rev. 2012;33(1):19–32.

29. Keshavarz R, Kawashima R, Low C. Child abuse and neglect presentations to a pediatric emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2002;23(4): 341-345.

30. Kellogg N; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of sexual abuse in children. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):506-512.

31. Heger A, Ticson L, Velasquez O, Bernier R. Children referred for possible sexual abuse: medical findings in 2384 children. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26(6-7):645-659.

32. Kellogg ND, Menard SW, Santos A. Genital anatomy in pregnant adolescents: “normal” does not mean “nothing happened.” Pediatrics. 2004; 113(1):e67-e69.

33. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

34. Oates RK. Overturning the diagnosis of child abuse. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59(7):665-666.

35. Hornor G. Common conditions that mimic findings of sexual abuse. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23(5):283-288.

36. Asnes RS. Buttock bruises: Mongolian spot. Pediatrics. 1984;74(2):321.

37. Klusmann A, Lenard HG. Tourniquet syndrome: accident or abuse? Eur J Pediatr. 2004; 163(8):495-498.

38. Merten DF, Carpenter BL. Radiologic imaging of inflicted injury in the child abuse syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1990;37(4):815-837.

39. Mok JY. Non-accidental injury in children: an update. Injury. 2008;39(9):978-985.

40. Nelson CS, Higman SM, Sia C, et al. Medical homes for at-risk children: parental reports of clinician-parent relationships, anticipatory guidance, and behavior changes. Pediatrics. 2005; 115(1):48-56.

41. Dubowitz H. Prevention of child maltreatment: what is known. Pediatrics. 1989;83(4):570-577.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment 2009 (2010). www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/pubs/cm09. Accessed February 22, 2012.

2. UNICEF Child Protection Strategy (2008). www .unrol.org/files/CP%20Strategy_English.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

3. World Health Organization. Child maltreatment: Fact Sheet #150, August 2010. www.who .int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs150/en/index.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

4. World Health Organization. Preventing Child Maltreatment: A Guide to Taking Action and Generating Evidence. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publi cations/2006/9241594365_eng.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

5. Giardino AP. Child maltreatment: is the glass half full yet? J Forensic Nurs. 2009;5(1):1-4.

6. Barriere D. Child abuse: history, laws and the ASPCA (2005). www.resourcesforattorneys.com/childabuseandtheaspcaarticle.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

7. The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, Including Adoption Opportunities and the Abandoned Infants Assistance Act, as Amended by the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003. www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/laws_policies/cblaws/capta03/capta_manual.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

8. H.R. 14: Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003. www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd ?bill=h108-14&tab=summary. Accessed February 22, 2012.

9. S. 3817: CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010. www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=s

111-3817. Accessed February 22, 2012.

10. National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect. NCANDS State Level Data 2009: National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System. www .ndacan.cornell.edu/cmrlpostings/msg00195.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

11. Finkelhor D, Jones L, Shattuck A; Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire. Updated trends in child maltreatment, 2009. http://unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/Updated_Trends_in_Child_Maltreatment_2009.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

12. CDC Injury Center: Violence Prevention. Child Maltreatment: Risk and Protective Factors (2011). www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childmaltreat ment/riskprotectivefactors.html. Accessed February 22, 2012.

13. Sullivan P, Knutson J. Maltreatment and disabilities: a population-based epidemiological study. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(10):1257-1273.

14. Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, et al. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress, Executive Summary. January 2010. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.

15. National Clearinghouse on Family Violence, Public Health Agency of Canada. Abuse of children with disabilities (2000). www.phac-aspc

.gc.ca/ncfv-cnivf/pdfs/nfnts-disabl-eng.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

16. Endorm EE. (2011, June 7, 2011). Physical abuse in children: epidemiology and clinical manifestations. www.uptodate.com/contents/physical-abuse-in-children-epidemiology-and-clinical-manifestations?source=search_result&

search=Phsical+abuse+i+children%3A+Epidemiology+and+clinical+manifestations&selectedTi

tle=1~150. Accessed February 22, 2012.

17. Pandya NK, Baldwin K, Kamath AF, et al. Unexplained fractures: child abuse or bone disease? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011; 469(3):805-812.

18. Gondim RM, Muñoz DR, Petri V. Child abuse: skin markers and differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(3):527-536.

19. Kemp AM, Dunstan F, Harrison S, et al. Patterns of skeletal fractures in child abuse: systematic review. BMJ. 2008;337:a1518.

20. Worlock P, Stower M, Barbor P. Patterns of fractures in accidental and non-accidental injury in children: a comparative study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293(6539):100-102.

21. Welsh Child Protection Systematic Review Group. www.core-info.cf.ac.uk. Accessed February 22, 2012.

22. Wardinsky TD. Genetic and congenital defect conditions that mimic child abuse. J Fam Pract. 1995;41(4):377-383.

23. American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria (2009). www.acr.org/SecondaryMainMenuCategories/quality_safety/app_criteria/pdf/ExpertPanelonPediatricImaging/Suspected PhysicalAbuseChildDoc9.aspx. Accessed February 22, 2012.

24. Meservy CJ, Towbin R, McLaurin RL, et al. Radiographic characteristics of skull fractures resulting from child abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149(1):173-175.

25. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Burn Injuries in Child Abuse (2001). www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/91190-6.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2012.

26. Lane WG, Dubowitz H. Primary care pediatricians’ experience, comfort and competence in the evaluation and management of child maltreatment: do we need child abuse experts? Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(2):76-83.

27. Child Welfare Information Gateway, US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Recognizing child abuse and neglect: signs and symptoms (2007). www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/signs.cfm. Accessed February 22, 2012.

28. Fortin K, Jenny C. Sexual abuse. Pediatr Rev. 2012;33(1):19–32.

29. Keshavarz R, Kawashima R, Low C. Child abuse and neglect presentations to a pediatric emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2002;23(4): 341-345.

30. Kellogg N; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of sexual abuse in children. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):506-512.

31. Heger A, Ticson L, Velasquez O, Bernier R. Children referred for possible sexual abuse: medical findings in 2384 children. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26(6-7):645-659.

32. Kellogg ND, Menard SW, Santos A. Genital anatomy in pregnant adolescents: “normal” does not mean “nothing happened.” Pediatrics. 2004; 113(1):e67-e69.

33. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

34. Oates RK. Overturning the diagnosis of child abuse. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59(7):665-666.

35. Hornor G. Common conditions that mimic findings of sexual abuse. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23(5):283-288.

36. Asnes RS. Buttock bruises: Mongolian spot. Pediatrics. 1984;74(2):321.

37. Klusmann A, Lenard HG. Tourniquet syndrome: accident or abuse? Eur J Pediatr. 2004; 163(8):495-498.

38. Merten DF, Carpenter BL. Radiologic imaging of inflicted injury in the child abuse syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1990;37(4):815-837.

39. Mok JY. Non-accidental injury in children: an update. Injury. 2008;39(9):978-985.