User login

Treatment-resistant OCD: There’s more we can do

Treatment-resistant OCD can be a debilitating condition. Diagnostic clarity is crucial to fully elicit symptoms and identify comorbid conditions in order to develop practical, evidence-based treatment strategies and improve the patient’s and family’s quality of life. In this article, we delineate first-line strategies for treatment-resistant OCD and then review augmentation strategies, with an emphasis on glutamate-modulating agents.

Making the diagnosis

The diagnosis of OCD is made when a patient meets DSM-5 criteria for the presence of obsessions and/or compulsions, which are defined as unwanted, distressing, intrusive, recurrent thoughts or images (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions).1 OCD is considered a chronic waxing and waning disorder; stress and lack of sleep lead to worsening symptoms. The hidden nature of symptoms and the reinforcement provided by the reduction in anxiety after performing a compulsion contribute to sustained illness. Eliciting symptoms from patients may be challenging due to the shame they may feel. When reviewing symptoms on the Y-BOCS, it is helpful to preface questions with statements such as “Many people report excessive concern or disgust with…” to help the patient feel understood and less anxious, rather than using direct queries, such as “Are you bothered by…?”

Consider comorbid conditions

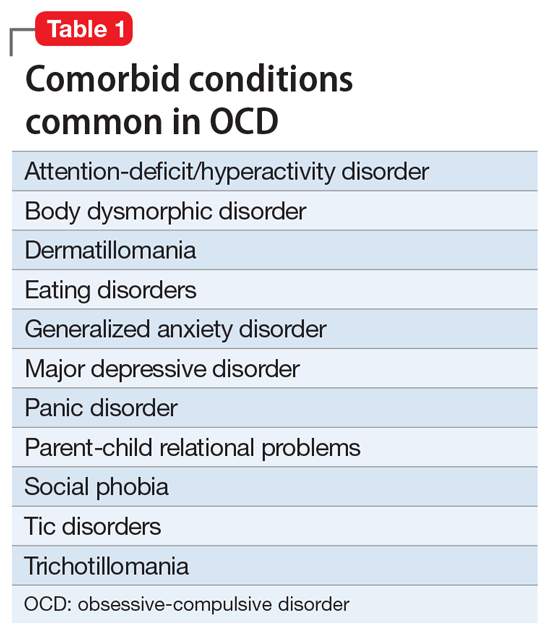

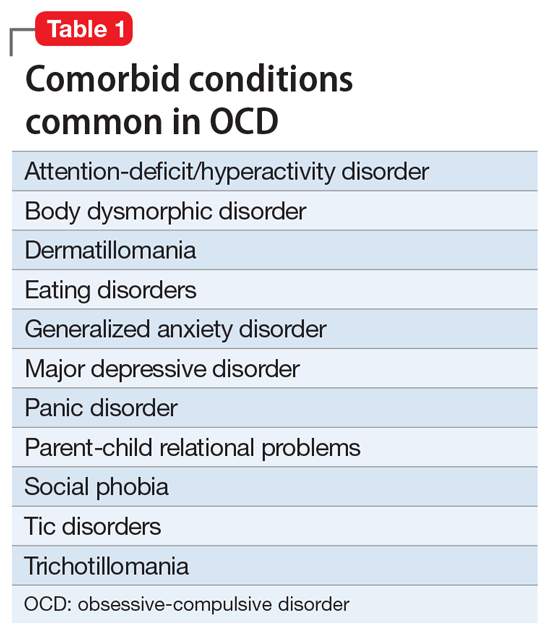

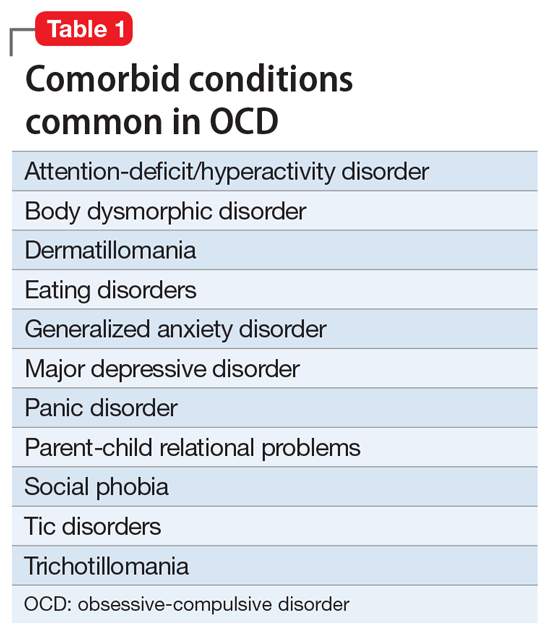

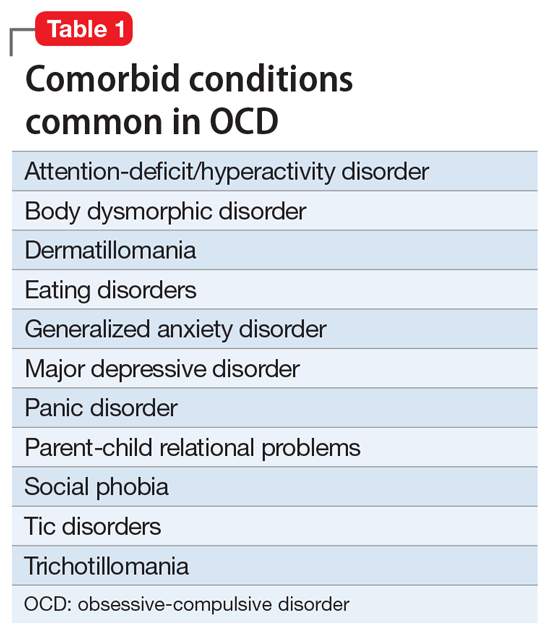

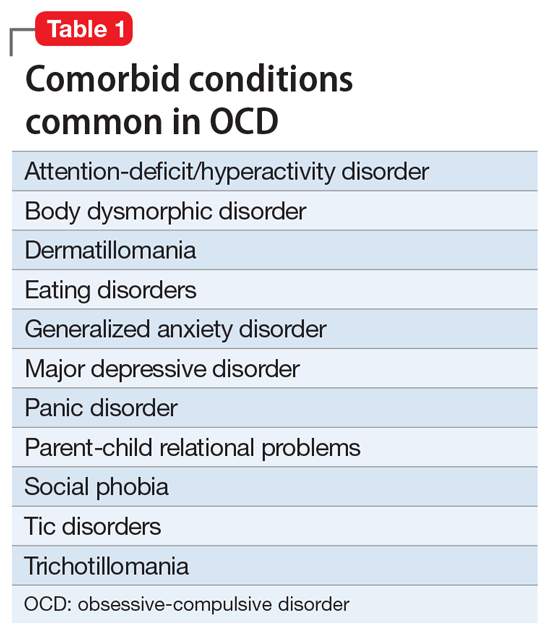

After making the initial diagnosis of OCD, it is important to assess whether the symptoms are better accounted for by another condition, and whether comorbid conditions are present (Table 1).

CASE CONTINUED

Ruling out other diagnoses

_

Initial treatment: CBT

Cognitive-behavioral therapy with exposures and response prevention (from here on referred to as CBT) has been established as a first-line, evidence-based treatment for OCD in both children and adults.2,3 For patients with treatment-resistant OCD, intensive daily CBT in a partial hospitalization or inpatient setting that is a tailor-made, patient-specific program is one of the most effective treatments, with response rates of up to 70%4-8 CBT’s advantages over medication include lower relapse rates and no known adverse effects. Unfortunately, CBT is underused9-11 due in part to a shortage of trained clinicians, and because patients may favor the ease of taking medication over the time, effort, and cost involved in CBT.

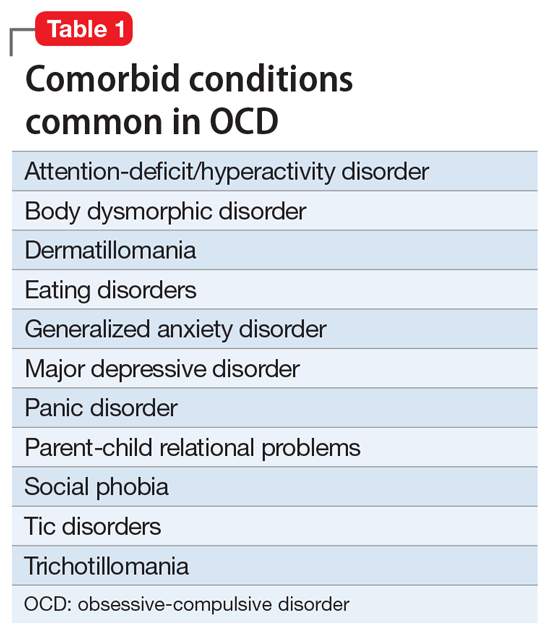

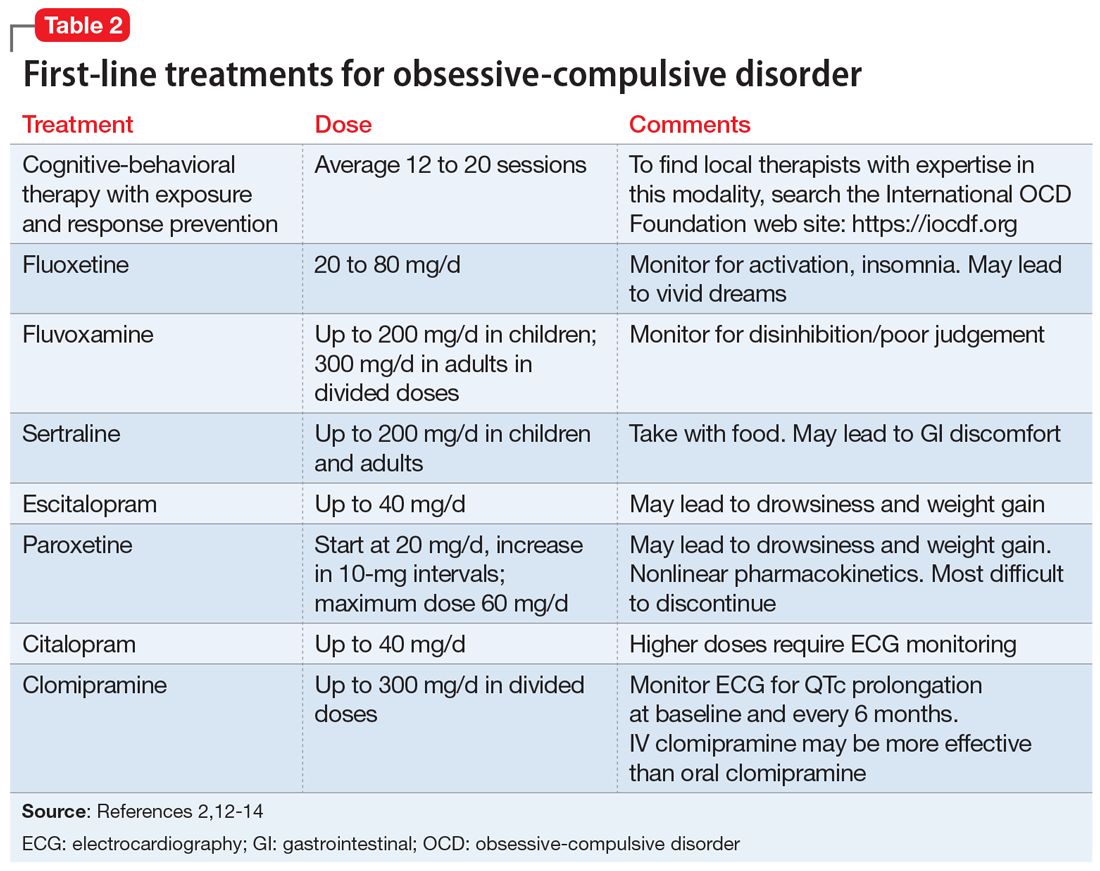

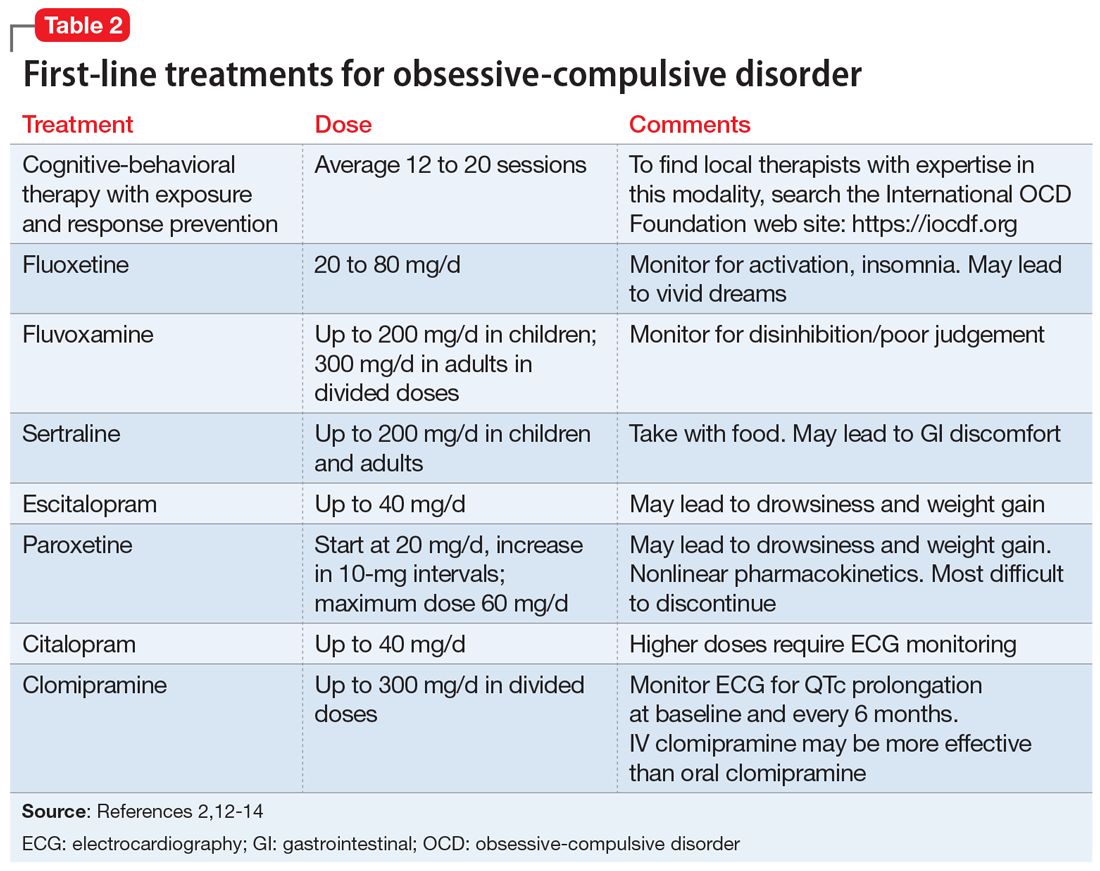

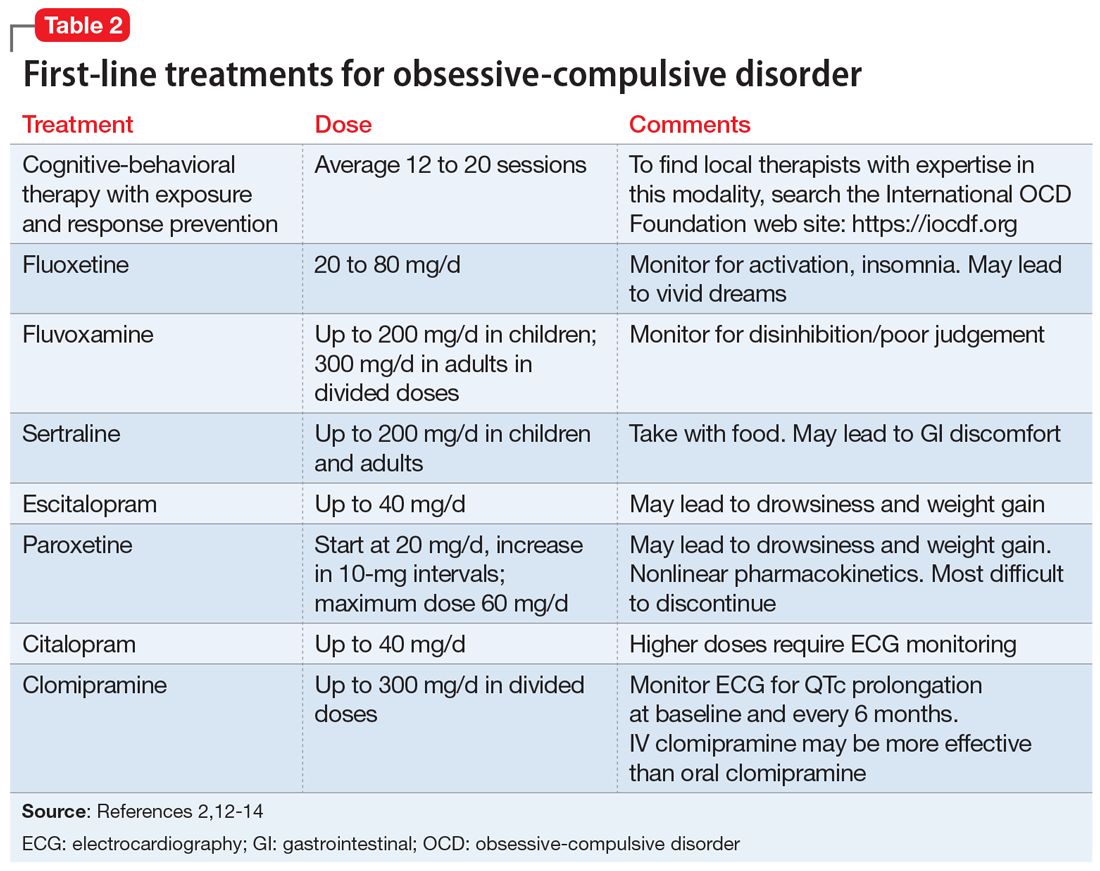

First-line pharmacologic options for treating OCD are SSRIs and clomipramine, as supported by multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, expert guidelines, and consensus statements (Table 22,12-14). No significant difference has been found among SSRIs for the treatment of OCD in a review of 17 studies that included more than 3,000 patients.15 Treatment with SSRIs or clomipramine is effective for 50% to 60% of patients.16 Many clinicians view the combination of an SSRI and CBT as the treatment of choice for OCD.2

Continue to: Reluctance to engage in CBT

CASE CONTINUED

Reluctance to engage in CBT

To determine the next course of action, you review Mr. S’s treatment history. He has received adequate doses of 2 SSRIs and currently is taking clomipramine, 100 mg twice daily. He recently began CBT, which includes homework to help face his fears; however, Mr. S is reluctant to complete the exposure assignments, and after pausing for a few seconds as he tries to resist sending an apology email to his coworkers, he then returns to his compulsive behavior.

Facing treatment resistance

Although currently there isn’t a cure to resolve all traces of OCD, the goal of treatment is to decrease distress, interference, and the frequency of symptoms to a minimal level such that only the patients themselves are aware of symptoms. In broad terms, “response” has been defined as a decrease in symptoms, and “remission” has been defined as minimal symptoms after treatment.

Close to half of adults treated for OCD respond well to standard-of-care treatment (CBT and/or an SSRI), while the other 50% are considered partial responders or nonresponders.2 For patients with OCD, researchers often define “treatment response” as a ≥25% reduction in symptom severity score on the Y-BOCS. Approximately 30% of adults with OCD do not respond substantially to the first-line treatments, and even those who are defined as “responders” in research studies typically continue to have significant symptoms that impact their quality of life.2 In children, a clinical definition for treatment-refractory OCD has been presented as failing to achieve adequate symptom relief despite receiving an adequate course of CBT and at least 2 adequate trials of an SSRI or clomipramine.17 In the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) trial, >46% of youth did not achieve remission from their OCD symptoms, even after receiving evidence-based care provided by experienced clinicians (combined treatment with CBT and an SSRI).18

_

Challenges in psychotherapy

Compassion is a key element in developing rapport with patients to help them face increasingly more challenging exposures. Making OCD the problem, not the person, is an essential element in helping patients move forward. Some clinicians may become frustrated with patients when treatment is not moving along well, referring to resistance, denial, or sabotage. According to March and Mulle,19 these terms lack the recognition and compassion that exposures are inherently difficult.19

Another challenge for therapists is if the patient’s presenting symptoms are personally offensive or a sensitive topic. For example, a therapist who is disgusted by public restrooms will find it difficult to tolerate the risks associated with exposure to germs and support a patient in touching objects in the restroom. Therapists also may be challenged when the patient’s fears align with the therapist’s religious beliefs. In these situations, consider transferring care to another therapist.

Family members need to learn about the nature of the illness and their roles in helping patients improve. Family members may unknowingly enable symptoms or criticize patients for their lack of motivation, which can lead to conflict in the home. Family dysfunction can in turn worsen OCD symptoms.

The most likely cause of lack of response to therapy is inexpert CBT.19 Deep breathing and relaxation training have been used as an active placebo in studies20; in a meta-analysis examining the effective components of CBT, studies that added relaxation training were not more effective than those that employed exposures alone.21 Patients receiving CBT should be able to articulate the hierarchical approach used to gradually face their fears.

Continue to: Pharmacologic augmentation strategies

Pharmacologic augmentation strategies

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. While most OCD research trials have assessed SSRIs in 12-week studies, clinicians may consider extending SSRI treatment for an additional 12 weeks for nonresponders because some patients will continue to make gains. In the past, it was generally believed that higher doses of SSRIs are needed for treating OCD than for treating major depressive disorder. For instance, greater improvement was seen with 250 to 400 mg/d of sertraline compared with 200 mg/d22 and with escitalopram after an increase of dose up to 50 mg/d.23 However, more recently, this notion of higher doses being necessary for treatment response has been called into question. For example, a study of escitalopram found similar responses to 10 mg/d vs 20 mg/d after 24 weeks.24 A meta-analysis of adult studies of SSRIs for OCD supported higher doses as being more effective, but noted that the drop-out rate from treatment was greater in patients treated with higher doses.25 As a note of caution, long-term, high-dose maintenance therapy increases the risk of adverse reactions.26

Following a failed treatment with a first SSRI, it remains debatable as to what ought to be the second pharmacologic treatment. Although clomipramine is often reserved for treatment after 2 failed trials of an SSRI due to its greater risk of adverse effects, in an open-label study, switching from an SSRI to clomipramine led to greater response than switching from one SSRI to another.27 On the other hand, while meta-analyses have reported greater treatment effect for oral clomipramine than for SSRIs, direct head-to-head comparisons have not supported this notion.28 To get the best of both worlds, some clinicians employ a strategy of combining clomipramine with an SSRI, while monitoring for adverse effects and interactions such as serotonin syndrome.29-31

Benzodiazepines. Although benzodiazepines are useful for brief treatment of an anxiety disorder (eg, for a person with a fear of heights who needs to take an airplane),32 they have not been shown to be effective for OCD33 or as augmentation to an SSRI.34

N-acetylcysteine (NAC). Two RCTs of adults with OCD who received adjunctive NAC, 3 g/d in divided doses, found no significant difference in the treatment arms by the conclusion of 16 weeks—either both groups improved, or both groups failed to improve.35,36 In a 10-week study of patients with moderate to severe OCD symptoms, NAC, 2 g/d, as augmentation to fluvoxamine, 200 mg/d, showed a significant time x interaction in the treatment group.37 No follow-up information is available, however.

In a multicenter RCT of NAC given to children and adolescents with OCD as augmentation to citalopram, symptoms decreased and the quality-of-life score improved, with a large treatment effect size in the NAC group.38 However, in a study aimed at examining NAC in youth with Tourette syndrome, OCD symptoms were measured as a secondary outcome and there was no benefit of NAC over placebo.39

Memantine. Four 8- to 12-week RCTs in adults with OCD favored adjunctive memantine, 20 mg/d, taken with an SSRI, over placebo.40-43 A small study suggests that patients with OCD may be more likely to respond to memantine than patients with generalized anxiety disorder.44 Case reports have noted that memantine has been beneficial for pediatric patients with refractory OCD.45

Continue to: Topiramate

Topiramate. Three 12-week RCTs examined topiramate augmentation at 100 to 400 mg/d in patients with OCD who had failed at least 1 previous trial of an SSRI. The earliest study was most encouraging: Y-BOCS scores decreased by 32% in the topiramate group but by only 2.4% in the placebo group.46 However, the other 2 studies found no difference in the final OCD symptom severity score between active treatment and placebo groups,47,48 and the use of topiramate, particularly at higher doses, was limited by its adverse effects.

Lamotrigine. Initially, lamotrigine augmentation of SSRIs in OCD did not appear to be helpful.49 More recently, several case studies reported that lamotrigine, 100 to 200 mg/d, added to paroxetine or clomipramine, resulted in dramatic improvement in Y-BOCS scores for patients with long-standing refractory symptoms.50,51 In a retrospective review of 22 patients who received augmentation with lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, 20 had a significant response; the mean decrease in Y-BOCS score was 67%.52 Finally, in a 16-week RCT, lamotrigine, 100 mg/d, added to an SSRI led to a significant decrease in both Y-BOCS score and depressive symptoms while also improving semantic fluency.53

Ketamine. Ketamine is drawing increased attention for its nearly instantaneous antidepressant effect that lasts for up to 2 weeks after a single infusion.54 In a study of 15 medication-free adults with continuous intrusive obsessions, 4 of 8 patients who received a single IV infusion of ketamine, 0.5 mg/kg, met the criteria for treatment response (>35% reduction in Y-BOCS score measured 1 week later); none of the patients who received a placebo infusion of saline met this criteria.55 A small open-label trial of 10 treatment-refractory patients found that an infusion of ketamine, 0.5 mg/kg, was beneficial for comorbid depression but had only a minimal effect on OCD symptoms measured 3 days post-infusion.56 A short-term follow-up on these patients revealed dysphoria in some responders.57

D-cycloserine. The idea of using a pharmacologic agent to increase the speed or efficacy of behavioral therapy is intriguing. Proof of concept was demonstrated in a study that found that giving D-cycloserine prior to computerized exposure therapy significantly improved clinical response in patients with acrophobia.58 However, using this approach to treating OCD netted mixed results; D-cycloserine was found to be most helpful during early stages of treatment.59,60

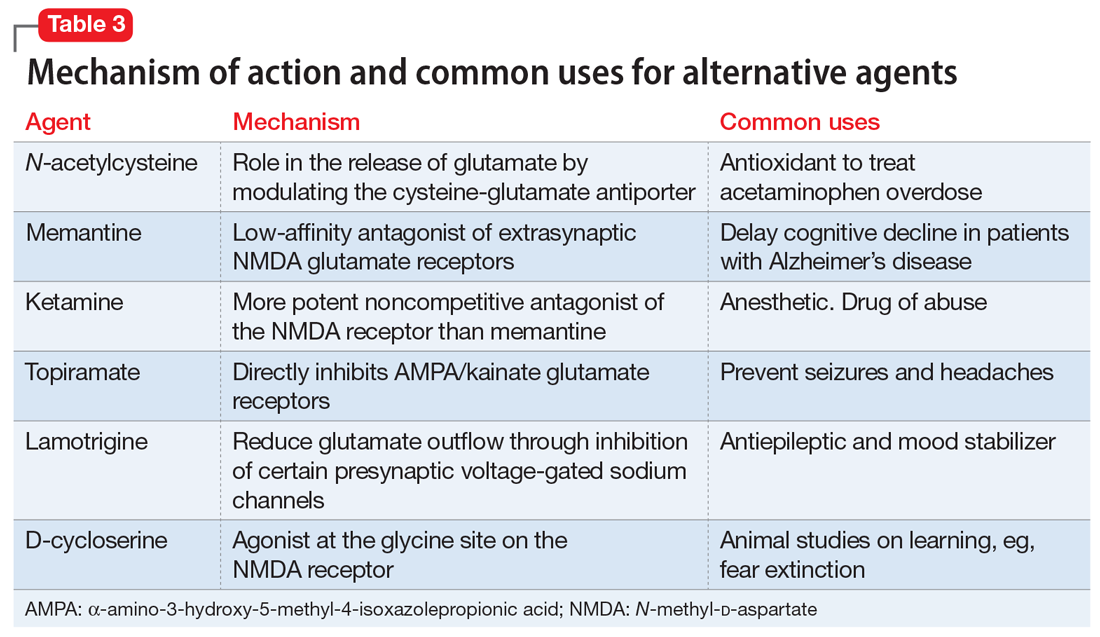

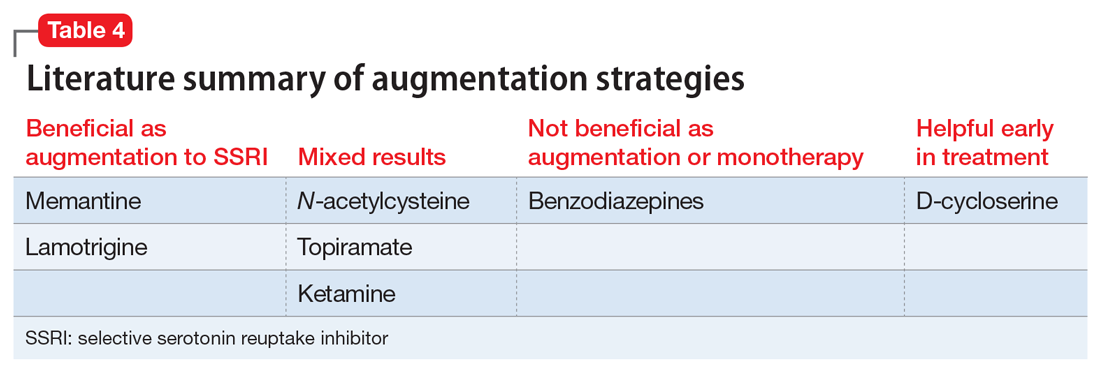

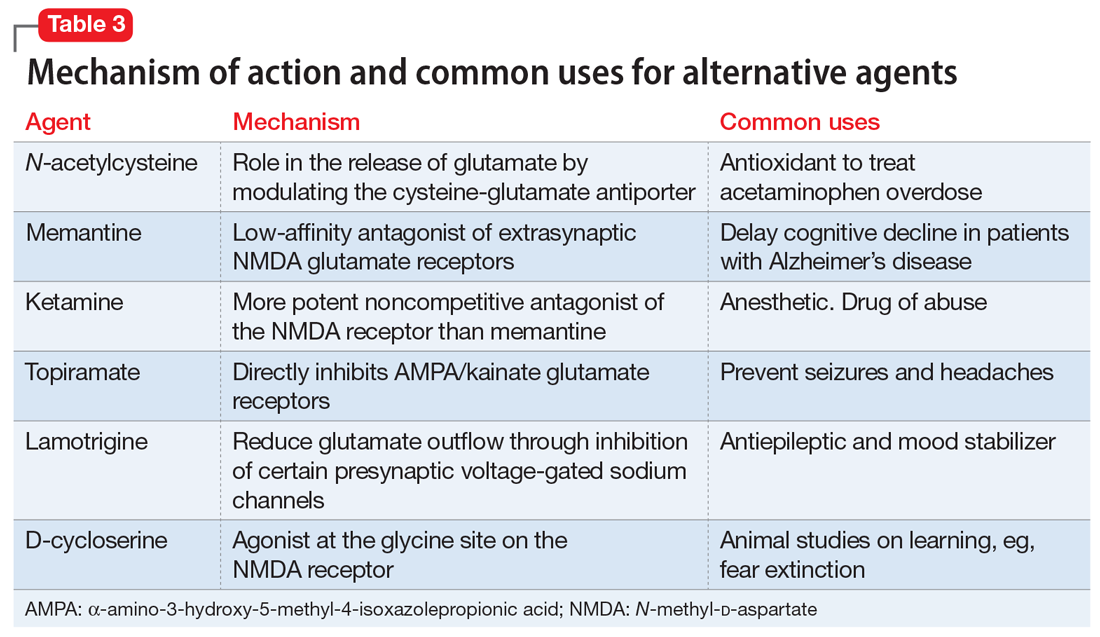

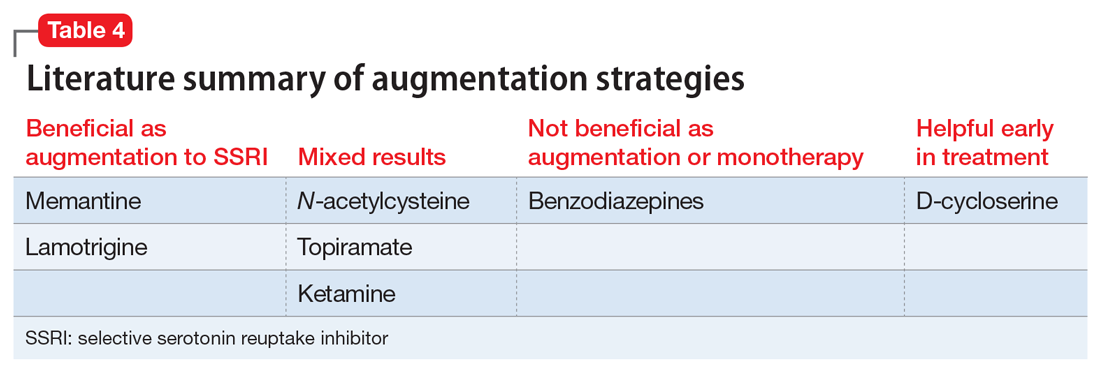

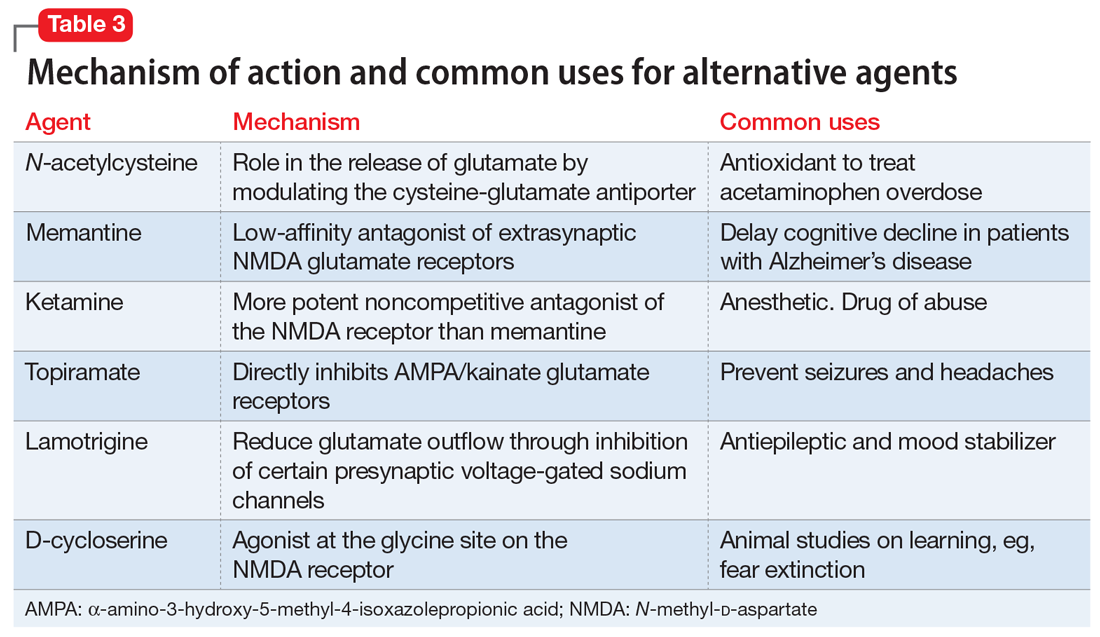

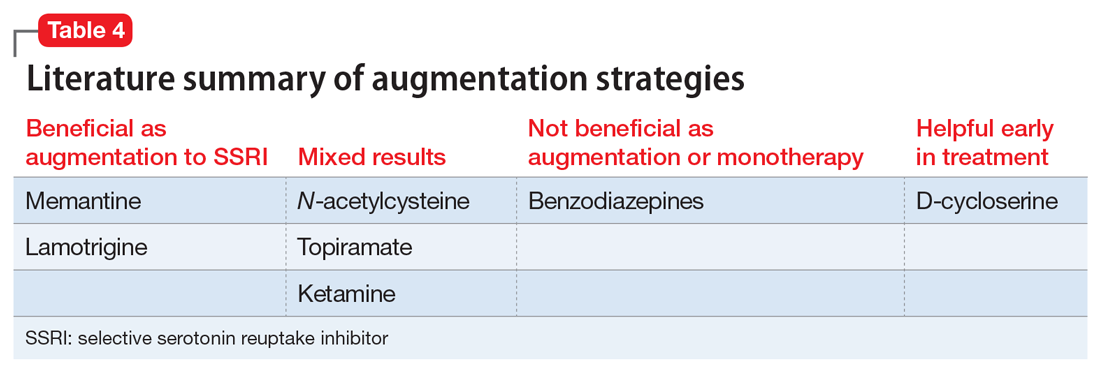

Table 3 outlines the mechanisms of action and common uses for NAC, memantine, ketamine, topiramate, lamotrigine, and D-cycloserine. Table 4 summarizes the literature on the efficacy of some of the augmentation strategies for treating OCD described in this article.

Continue to: Alternative strategies

Alternative strategies

Augmentation strategies with neuroleptics,61 transcranial magnetic stimulation,62 and deep brain stimulation63 have recently been reviewed. Space limitations preclude a comprehensive review of these strategies, but in a cross-sectional study of augmentation strategies in OCD, no difference was found in terms of symptom severity between those prescribed SSRI monotherapy or augmentation with neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, or antidepressants.64

CASE CONTINUED

Progress in CBT

Mr. S agrees to a trial of NAC as an augmentation strategy, but after 8 weeks of treatment with NAC, 600 mg twice daily, his Y-BOCS had declined by only 2 points. He also complains of nausea and does not want to increase the dose. You discontinue NAC and opt to further explore his reaction to CBT. Mr. S shares that he has been seeing his psychologist only once every 3 weeks because he does not want to miss work. You encourage him to increase to weekly CBT sessions, and you obtain his permission to contact his therapist and his family members. Fortunately, his therapist is highly qualified, but unfortunately, Mr. S’s father has been sending him multiple critical emails about not advancing at his job and for being “lazy” at work. You schedule a session with Mr. S and his father. Great progress is made after Mr. S and his father both share their frustrations and come to understand and appreciate each other’s struggles. Four weeks later, after weekly CBT appointments, Mr. S has a Y-BOCS of 18 and spends <2 hours/d checking emails for errors and apologizing.

Bottom Line

It is unrealistic to expect OCD symptoms to be cured. Many ‘treatment-resistant’ patients have not received properly delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy, and this first-line treatment modality should be considered in every eligible patient, and augmented with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) when needed. Glutamatergic agents, in turn, can augment SSRIs.

Related Resources

- Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. https://iocdf.org/ wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Assessment-Tools.pdf.

- The International OCD Foundation. https://iocdf.org.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Ketamine • Ketalar

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Memantine • Namenda

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Topiramate • Topomax

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Koran LM, Hanna GL, Hollander E, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry; 2007;164(suppl 7):5-53.

3. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98-113.

4. Bystritsky A, Munford PR, Rosen RM, et al. A preliminary study of partial hospital management of severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(2):170-174.

5. Calvocoressi L, McDougle CI, Wasylink S, et al. Inpatient treatment of patients with severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(12):1150-1154.

6. Eddy KT, Dutra L, Bradley R, et al. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(8):1011-1030.

7. Abramowitz JS. The psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(7):407-416.

8. Simpson HB, Huppert JD, Petkova E, et al. Response versus remission in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(2):269-276.

9. Marques L, LeBlanc NJ, Weingarden HM, et al. Barriers to treatment and service utilization in an internet sample of individuals with obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(5):470-475.

10. Goodwin R, Koenen KC, Hellman F, et al. Helpseeking and access to mental health treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(2):143-149.

11. Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, et al. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):858-866.

12. Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, et al. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(5):403-439.

13. Lovell K, Bee P. Implementing the NICE OCD/BDD guidelines. Psychol Psychother. 2008;81(Pt 4):365-376.

14. Bandelow B, Sher L, Bunevicius R, et al. Guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2012;16(2):77-84.

15. Soomro GM, Altman D, Rajagopal S, et al. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus placebo for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001765.

16. Pittenger C, Bloch MH. Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(3):375-391.

17. Bloch MH, Storch EA. Assessment and management of treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(4):251-262.

18. Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969-1976.

19. March JS, Mulle K. OCD in children and adolescents: a cognitive-behavioral treatment manual. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998.

20. Marks IM. Fears, phobias, and rituals: Panic, anxiety, and their disorders. 1987, New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1987.

21. Ale CM, McCarthy DM, Rothschild LM, et al. Components of cognitive behavioral therapy related to outcome in childhood anxiety disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2015;18(3):240-251.

22. Ninan PT, Koran LM, Kiev A, et al. High-dose sertraline strategy for nonresponders to acute treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a multicenter double-blind trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(1):15-22.

23. Rabinowitz I, Baruch Y, Barak Y. High-dose escitalopram for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(1):49-53.

24. Stein DJ, Andersen EW, Tonnoir B, et al. Escitalopram in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, paroxetine-referenced, fixed-dose, 24-week study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(4):701-711.

25. Bloch MH, McGuire J, Landeros-Weisenberger A, et al. Meta-analysis of the dose-response relationship of SSRI in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(8):850-855.

26. Sayyah M, Majzoob S, Sayyah M. Metabolic and toxicological considerations for obsessive-compulsive disorder drug therapy. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9(6):657-673.

27. Hollander E, Bienstock CA, Koran LM, et al. Refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: state-of-the-art treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(suppl 6):20-29.

28. Fineberg NA, Gale TM. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(1):107-129.

29. Marazziti D, Golia F, Consoli G, et al. Effectiveness of long-term augmentation with citalopram to clomipramine in treatment-resistant OCD patients. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):971-976.

30. Browne M, Horn E, Jones TT. The benefits of clomipramine-fluoxetine combination in obsessive compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 1993;38(4):242-243.

31. Ravizza L, Barzega G, Bellino S, et al. Drug treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): long-term trial with clomipramine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1996;32(1):167-173.

32. Koen N, Stein DJ. Pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders: a critical review. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(4):423-437.

33. Hollander E, Kaplan A, Stahl SM. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of clonazepam in obsessive-compulsive disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2003;4(1):30-34.

34. Crockett BA, Churchill E, Davidson JR. A double-blind combination study of clonazepam with sertraline in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16(3):127-132.

35. Costa DLC, Diniz JB, Requena G, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of n-acetylcysteine augmentation for treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(7):e766-e773.

36. Sarris J, Oliver G, Camfield DA, et al. N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a 16-week, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study. CNS Drugs. 2015;29(9):801-809.

37. Paydary K, Akamaloo A, Ahmadipour A, et al. N-acetylcysteine augmentation therapy for moderate-to-severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(2):214-219.

38. Ghanizadeh A, Mohammadi MR, Bahraini S, et al. Efficacy of N-acetylcysteine augmentation on obsessive compulsive disorder: a multicenter randomized double blind placebo controlled clinical trial. Iran J Psychiatry. 2017;12(2):134-141.

39. Bloch MH, Panza KE, Yaffa A, et al. N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of pediatric tourette syndrome: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled add-on trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(4):327-334.

40. Ghaleiha A, Entezari N, Modabbernia A, et al. Memantine add-on in moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(2):175-180.

41. Stewart SE, Jenike EA, Hezel DM, et al. A single-blinded case-control study of memantine in severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(1):34-39.

42. Modarresi A, Sayyah M, Razooghi S, et al. Memantine augmentation improves symptoms in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-120268. [Epub ahead of print].

43. Haghighi M, Jahangard L, Mohammad-Beigi H, et al. In a double-blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trial, adjuvant memantine improved symptoms in inpatients suffering from refractory obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD). Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;228(4):633-640.

44. Feusner JD, Kerwin L, Saxena S, et al. Differential efficacy of memantine for obsessive-compulsive disorder vs. generalized anxiety disorder: an open-label trial. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2009;42(1):81-93.

45. Hezel DM, Beattie K, Stewart SE. Memantine as an augmenting agent for severe pediatric OCD. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):237.

46. Mowla A, Khajeian AM, Sahraian A, et al. topiramate augmentation in resistant ocd: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(11):613-617.

47. Berlin H, Koran LM, Jenike MA, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):716-721.

48. Afshar H, Akuchekian S, Mahaky B, et al. Topiramate augmentation in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19(10):976-981.

49. Kumar TC, Khanna S. Lamotrigine augmentation of serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(3):527-528.

50. Arrojo-Romero M, Tajes Alonso M, de Leon J. Lamotrigine augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in severe and long-term treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2013;2013:612459.

51. Uzun O. Lamotrigine as an augmentation agent in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a case report. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(3):425-427.

52. Hussain A, Dar MA, Wani RA, et al. Role of lamotrigine augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: a retrospective case review from South Asia. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37(2):154-158.

53. Bruno A, Micò U, Pandolfo G, et al. Lamotrigine augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(11):1456-1462.

54. Krystal JH, Sanacora G, Duman RS. Rapid-acting glutamatergic antidepressants: the path to ketamine and beyond. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):113311-41.

55. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. Randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: proof-of-concept. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(12):2475-2483.

56. Bloch MH, Wasylink S, Landeros-Weisenberger A,, et al. Effects of ketamine in treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(11):964-970.

57. Niciu MJ, Grunschel BD, Corlett PR, et al. Two cases of delayed-onset suicidal ideation, dysphoria and anxiety after ketamine infusion in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and a history of major depressive disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(7):651-654.

58. Ressler KJ, Rothbaum BO, Tannenbaum L, et al. Cognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: use of D-cycloserine in phobic individuals to facilitate extinction of fear. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1136-1144.

59. Norberg MM, Krystal JH, Tolin DF. A meta-analysis of D-cycloserine and the facilitation of fear extinction and exposure therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(12):1118-1126.

60. Xia J, Du Y, Han J, et al. D-cycloserine augmentation in behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:2101-2117.

61. Veale D, Miles S, Smallcombe N, et al. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in SSRI treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:317.

62. Guo Q, Li C, Wang J. Updated review on the clinical use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in psychiatric disorders. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33(6):747-756.

63. Naesström, M, Blomstedt P, Bodlund O. A systematic review of psychiatric indications for deep brain stimulation, with focus on major depressive and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 2016;70(7):483-491.

64. Van Ameringen M, Simpson W, Patterson B, et al. Pharmacological treatment strategies in obsessive compulsive disorder: A cross-sectional view in nine international OCD centers. J Psychopharmacol, 2014;28(6):596-602.

Treatment-resistant OCD can be a debilitating condition. Diagnostic clarity is crucial to fully elicit symptoms and identify comorbid conditions in order to develop practical, evidence-based treatment strategies and improve the patient’s and family’s quality of life. In this article, we delineate first-line strategies for treatment-resistant OCD and then review augmentation strategies, with an emphasis on glutamate-modulating agents.

Making the diagnosis

The diagnosis of OCD is made when a patient meets DSM-5 criteria for the presence of obsessions and/or compulsions, which are defined as unwanted, distressing, intrusive, recurrent thoughts or images (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions).1 OCD is considered a chronic waxing and waning disorder; stress and lack of sleep lead to worsening symptoms. The hidden nature of symptoms and the reinforcement provided by the reduction in anxiety after performing a compulsion contribute to sustained illness. Eliciting symptoms from patients may be challenging due to the shame they may feel. When reviewing symptoms on the Y-BOCS, it is helpful to preface questions with statements such as “Many people report excessive concern or disgust with…” to help the patient feel understood and less anxious, rather than using direct queries, such as “Are you bothered by…?”

Consider comorbid conditions

After making the initial diagnosis of OCD, it is important to assess whether the symptoms are better accounted for by another condition, and whether comorbid conditions are present (Table 1).

CASE CONTINUED

Ruling out other diagnoses

_

Initial treatment: CBT

Cognitive-behavioral therapy with exposures and response prevention (from here on referred to as CBT) has been established as a first-line, evidence-based treatment for OCD in both children and adults.2,3 For patients with treatment-resistant OCD, intensive daily CBT in a partial hospitalization or inpatient setting that is a tailor-made, patient-specific program is one of the most effective treatments, with response rates of up to 70%4-8 CBT’s advantages over medication include lower relapse rates and no known adverse effects. Unfortunately, CBT is underused9-11 due in part to a shortage of trained clinicians, and because patients may favor the ease of taking medication over the time, effort, and cost involved in CBT.

First-line pharmacologic options for treating OCD are SSRIs and clomipramine, as supported by multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, expert guidelines, and consensus statements (Table 22,12-14). No significant difference has been found among SSRIs for the treatment of OCD in a review of 17 studies that included more than 3,000 patients.15 Treatment with SSRIs or clomipramine is effective for 50% to 60% of patients.16 Many clinicians view the combination of an SSRI and CBT as the treatment of choice for OCD.2

Continue to: Reluctance to engage in CBT

CASE CONTINUED

Reluctance to engage in CBT

To determine the next course of action, you review Mr. S’s treatment history. He has received adequate doses of 2 SSRIs and currently is taking clomipramine, 100 mg twice daily. He recently began CBT, which includes homework to help face his fears; however, Mr. S is reluctant to complete the exposure assignments, and after pausing for a few seconds as he tries to resist sending an apology email to his coworkers, he then returns to his compulsive behavior.

Facing treatment resistance

Although currently there isn’t a cure to resolve all traces of OCD, the goal of treatment is to decrease distress, interference, and the frequency of symptoms to a minimal level such that only the patients themselves are aware of symptoms. In broad terms, “response” has been defined as a decrease in symptoms, and “remission” has been defined as minimal symptoms after treatment.

Close to half of adults treated for OCD respond well to standard-of-care treatment (CBT and/or an SSRI), while the other 50% are considered partial responders or nonresponders.2 For patients with OCD, researchers often define “treatment response” as a ≥25% reduction in symptom severity score on the Y-BOCS. Approximately 30% of adults with OCD do not respond substantially to the first-line treatments, and even those who are defined as “responders” in research studies typically continue to have significant symptoms that impact their quality of life.2 In children, a clinical definition for treatment-refractory OCD has been presented as failing to achieve adequate symptom relief despite receiving an adequate course of CBT and at least 2 adequate trials of an SSRI or clomipramine.17 In the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) trial, >46% of youth did not achieve remission from their OCD symptoms, even after receiving evidence-based care provided by experienced clinicians (combined treatment with CBT and an SSRI).18

_

Challenges in psychotherapy

Compassion is a key element in developing rapport with patients to help them face increasingly more challenging exposures. Making OCD the problem, not the person, is an essential element in helping patients move forward. Some clinicians may become frustrated with patients when treatment is not moving along well, referring to resistance, denial, or sabotage. According to March and Mulle,19 these terms lack the recognition and compassion that exposures are inherently difficult.19

Another challenge for therapists is if the patient’s presenting symptoms are personally offensive or a sensitive topic. For example, a therapist who is disgusted by public restrooms will find it difficult to tolerate the risks associated with exposure to germs and support a patient in touching objects in the restroom. Therapists also may be challenged when the patient’s fears align with the therapist’s religious beliefs. In these situations, consider transferring care to another therapist.

Family members need to learn about the nature of the illness and their roles in helping patients improve. Family members may unknowingly enable symptoms or criticize patients for their lack of motivation, which can lead to conflict in the home. Family dysfunction can in turn worsen OCD symptoms.

The most likely cause of lack of response to therapy is inexpert CBT.19 Deep breathing and relaxation training have been used as an active placebo in studies20; in a meta-analysis examining the effective components of CBT, studies that added relaxation training were not more effective than those that employed exposures alone.21 Patients receiving CBT should be able to articulate the hierarchical approach used to gradually face their fears.

Continue to: Pharmacologic augmentation strategies

Pharmacologic augmentation strategies

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. While most OCD research trials have assessed SSRIs in 12-week studies, clinicians may consider extending SSRI treatment for an additional 12 weeks for nonresponders because some patients will continue to make gains. In the past, it was generally believed that higher doses of SSRIs are needed for treating OCD than for treating major depressive disorder. For instance, greater improvement was seen with 250 to 400 mg/d of sertraline compared with 200 mg/d22 and with escitalopram after an increase of dose up to 50 mg/d.23 However, more recently, this notion of higher doses being necessary for treatment response has been called into question. For example, a study of escitalopram found similar responses to 10 mg/d vs 20 mg/d after 24 weeks.24 A meta-analysis of adult studies of SSRIs for OCD supported higher doses as being more effective, but noted that the drop-out rate from treatment was greater in patients treated with higher doses.25 As a note of caution, long-term, high-dose maintenance therapy increases the risk of adverse reactions.26

Following a failed treatment with a first SSRI, it remains debatable as to what ought to be the second pharmacologic treatment. Although clomipramine is often reserved for treatment after 2 failed trials of an SSRI due to its greater risk of adverse effects, in an open-label study, switching from an SSRI to clomipramine led to greater response than switching from one SSRI to another.27 On the other hand, while meta-analyses have reported greater treatment effect for oral clomipramine than for SSRIs, direct head-to-head comparisons have not supported this notion.28 To get the best of both worlds, some clinicians employ a strategy of combining clomipramine with an SSRI, while monitoring for adverse effects and interactions such as serotonin syndrome.29-31

Benzodiazepines. Although benzodiazepines are useful for brief treatment of an anxiety disorder (eg, for a person with a fear of heights who needs to take an airplane),32 they have not been shown to be effective for OCD33 or as augmentation to an SSRI.34

N-acetylcysteine (NAC). Two RCTs of adults with OCD who received adjunctive NAC, 3 g/d in divided doses, found no significant difference in the treatment arms by the conclusion of 16 weeks—either both groups improved, or both groups failed to improve.35,36 In a 10-week study of patients with moderate to severe OCD symptoms, NAC, 2 g/d, as augmentation to fluvoxamine, 200 mg/d, showed a significant time x interaction in the treatment group.37 No follow-up information is available, however.

In a multicenter RCT of NAC given to children and adolescents with OCD as augmentation to citalopram, symptoms decreased and the quality-of-life score improved, with a large treatment effect size in the NAC group.38 However, in a study aimed at examining NAC in youth with Tourette syndrome, OCD symptoms were measured as a secondary outcome and there was no benefit of NAC over placebo.39

Memantine. Four 8- to 12-week RCTs in adults with OCD favored adjunctive memantine, 20 mg/d, taken with an SSRI, over placebo.40-43 A small study suggests that patients with OCD may be more likely to respond to memantine than patients with generalized anxiety disorder.44 Case reports have noted that memantine has been beneficial for pediatric patients with refractory OCD.45

Continue to: Topiramate

Topiramate. Three 12-week RCTs examined topiramate augmentation at 100 to 400 mg/d in patients with OCD who had failed at least 1 previous trial of an SSRI. The earliest study was most encouraging: Y-BOCS scores decreased by 32% in the topiramate group but by only 2.4% in the placebo group.46 However, the other 2 studies found no difference in the final OCD symptom severity score between active treatment and placebo groups,47,48 and the use of topiramate, particularly at higher doses, was limited by its adverse effects.

Lamotrigine. Initially, lamotrigine augmentation of SSRIs in OCD did not appear to be helpful.49 More recently, several case studies reported that lamotrigine, 100 to 200 mg/d, added to paroxetine or clomipramine, resulted in dramatic improvement in Y-BOCS scores for patients with long-standing refractory symptoms.50,51 In a retrospective review of 22 patients who received augmentation with lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, 20 had a significant response; the mean decrease in Y-BOCS score was 67%.52 Finally, in a 16-week RCT, lamotrigine, 100 mg/d, added to an SSRI led to a significant decrease in both Y-BOCS score and depressive symptoms while also improving semantic fluency.53

Ketamine. Ketamine is drawing increased attention for its nearly instantaneous antidepressant effect that lasts for up to 2 weeks after a single infusion.54 In a study of 15 medication-free adults with continuous intrusive obsessions, 4 of 8 patients who received a single IV infusion of ketamine, 0.5 mg/kg, met the criteria for treatment response (>35% reduction in Y-BOCS score measured 1 week later); none of the patients who received a placebo infusion of saline met this criteria.55 A small open-label trial of 10 treatment-refractory patients found that an infusion of ketamine, 0.5 mg/kg, was beneficial for comorbid depression but had only a minimal effect on OCD symptoms measured 3 days post-infusion.56 A short-term follow-up on these patients revealed dysphoria in some responders.57

D-cycloserine. The idea of using a pharmacologic agent to increase the speed or efficacy of behavioral therapy is intriguing. Proof of concept was demonstrated in a study that found that giving D-cycloserine prior to computerized exposure therapy significantly improved clinical response in patients with acrophobia.58 However, using this approach to treating OCD netted mixed results; D-cycloserine was found to be most helpful during early stages of treatment.59,60

Table 3 outlines the mechanisms of action and common uses for NAC, memantine, ketamine, topiramate, lamotrigine, and D-cycloserine. Table 4 summarizes the literature on the efficacy of some of the augmentation strategies for treating OCD described in this article.

Continue to: Alternative strategies

Alternative strategies

Augmentation strategies with neuroleptics,61 transcranial magnetic stimulation,62 and deep brain stimulation63 have recently been reviewed. Space limitations preclude a comprehensive review of these strategies, but in a cross-sectional study of augmentation strategies in OCD, no difference was found in terms of symptom severity between those prescribed SSRI monotherapy or augmentation with neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, or antidepressants.64

CASE CONTINUED

Progress in CBT

Mr. S agrees to a trial of NAC as an augmentation strategy, but after 8 weeks of treatment with NAC, 600 mg twice daily, his Y-BOCS had declined by only 2 points. He also complains of nausea and does not want to increase the dose. You discontinue NAC and opt to further explore his reaction to CBT. Mr. S shares that he has been seeing his psychologist only once every 3 weeks because he does not want to miss work. You encourage him to increase to weekly CBT sessions, and you obtain his permission to contact his therapist and his family members. Fortunately, his therapist is highly qualified, but unfortunately, Mr. S’s father has been sending him multiple critical emails about not advancing at his job and for being “lazy” at work. You schedule a session with Mr. S and his father. Great progress is made after Mr. S and his father both share their frustrations and come to understand and appreciate each other’s struggles. Four weeks later, after weekly CBT appointments, Mr. S has a Y-BOCS of 18 and spends <2 hours/d checking emails for errors and apologizing.

Bottom Line

It is unrealistic to expect OCD symptoms to be cured. Many ‘treatment-resistant’ patients have not received properly delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy, and this first-line treatment modality should be considered in every eligible patient, and augmented with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) when needed. Glutamatergic agents, in turn, can augment SSRIs.

Related Resources

- Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. https://iocdf.org/ wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Assessment-Tools.pdf.

- The International OCD Foundation. https://iocdf.org.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Ketamine • Ketalar

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Memantine • Namenda

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Topiramate • Topomax

Treatment-resistant OCD can be a debilitating condition. Diagnostic clarity is crucial to fully elicit symptoms and identify comorbid conditions in order to develop practical, evidence-based treatment strategies and improve the patient’s and family’s quality of life. In this article, we delineate first-line strategies for treatment-resistant OCD and then review augmentation strategies, with an emphasis on glutamate-modulating agents.

Making the diagnosis

The diagnosis of OCD is made when a patient meets DSM-5 criteria for the presence of obsessions and/or compulsions, which are defined as unwanted, distressing, intrusive, recurrent thoughts or images (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions).1 OCD is considered a chronic waxing and waning disorder; stress and lack of sleep lead to worsening symptoms. The hidden nature of symptoms and the reinforcement provided by the reduction in anxiety after performing a compulsion contribute to sustained illness. Eliciting symptoms from patients may be challenging due to the shame they may feel. When reviewing symptoms on the Y-BOCS, it is helpful to preface questions with statements such as “Many people report excessive concern or disgust with…” to help the patient feel understood and less anxious, rather than using direct queries, such as “Are you bothered by…?”

Consider comorbid conditions

After making the initial diagnosis of OCD, it is important to assess whether the symptoms are better accounted for by another condition, and whether comorbid conditions are present (Table 1).

CASE CONTINUED

Ruling out other diagnoses

_

Initial treatment: CBT

Cognitive-behavioral therapy with exposures and response prevention (from here on referred to as CBT) has been established as a first-line, evidence-based treatment for OCD in both children and adults.2,3 For patients with treatment-resistant OCD, intensive daily CBT in a partial hospitalization or inpatient setting that is a tailor-made, patient-specific program is one of the most effective treatments, with response rates of up to 70%4-8 CBT’s advantages over medication include lower relapse rates and no known adverse effects. Unfortunately, CBT is underused9-11 due in part to a shortage of trained clinicians, and because patients may favor the ease of taking medication over the time, effort, and cost involved in CBT.

First-line pharmacologic options for treating OCD are SSRIs and clomipramine, as supported by multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, expert guidelines, and consensus statements (Table 22,12-14). No significant difference has been found among SSRIs for the treatment of OCD in a review of 17 studies that included more than 3,000 patients.15 Treatment with SSRIs or clomipramine is effective for 50% to 60% of patients.16 Many clinicians view the combination of an SSRI and CBT as the treatment of choice for OCD.2

Continue to: Reluctance to engage in CBT

CASE CONTINUED

Reluctance to engage in CBT

To determine the next course of action, you review Mr. S’s treatment history. He has received adequate doses of 2 SSRIs and currently is taking clomipramine, 100 mg twice daily. He recently began CBT, which includes homework to help face his fears; however, Mr. S is reluctant to complete the exposure assignments, and after pausing for a few seconds as he tries to resist sending an apology email to his coworkers, he then returns to his compulsive behavior.

Facing treatment resistance

Although currently there isn’t a cure to resolve all traces of OCD, the goal of treatment is to decrease distress, interference, and the frequency of symptoms to a minimal level such that only the patients themselves are aware of symptoms. In broad terms, “response” has been defined as a decrease in symptoms, and “remission” has been defined as minimal symptoms after treatment.

Close to half of adults treated for OCD respond well to standard-of-care treatment (CBT and/or an SSRI), while the other 50% are considered partial responders or nonresponders.2 For patients with OCD, researchers often define “treatment response” as a ≥25% reduction in symptom severity score on the Y-BOCS. Approximately 30% of adults with OCD do not respond substantially to the first-line treatments, and even those who are defined as “responders” in research studies typically continue to have significant symptoms that impact their quality of life.2 In children, a clinical definition for treatment-refractory OCD has been presented as failing to achieve adequate symptom relief despite receiving an adequate course of CBT and at least 2 adequate trials of an SSRI or clomipramine.17 In the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) trial, >46% of youth did not achieve remission from their OCD symptoms, even after receiving evidence-based care provided by experienced clinicians (combined treatment with CBT and an SSRI).18

_

Challenges in psychotherapy

Compassion is a key element in developing rapport with patients to help them face increasingly more challenging exposures. Making OCD the problem, not the person, is an essential element in helping patients move forward. Some clinicians may become frustrated with patients when treatment is not moving along well, referring to resistance, denial, or sabotage. According to March and Mulle,19 these terms lack the recognition and compassion that exposures are inherently difficult.19

Another challenge for therapists is if the patient’s presenting symptoms are personally offensive or a sensitive topic. For example, a therapist who is disgusted by public restrooms will find it difficult to tolerate the risks associated with exposure to germs and support a patient in touching objects in the restroom. Therapists also may be challenged when the patient’s fears align with the therapist’s religious beliefs. In these situations, consider transferring care to another therapist.

Family members need to learn about the nature of the illness and their roles in helping patients improve. Family members may unknowingly enable symptoms or criticize patients for their lack of motivation, which can lead to conflict in the home. Family dysfunction can in turn worsen OCD symptoms.

The most likely cause of lack of response to therapy is inexpert CBT.19 Deep breathing and relaxation training have been used as an active placebo in studies20; in a meta-analysis examining the effective components of CBT, studies that added relaxation training were not more effective than those that employed exposures alone.21 Patients receiving CBT should be able to articulate the hierarchical approach used to gradually face their fears.

Continue to: Pharmacologic augmentation strategies

Pharmacologic augmentation strategies

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. While most OCD research trials have assessed SSRIs in 12-week studies, clinicians may consider extending SSRI treatment for an additional 12 weeks for nonresponders because some patients will continue to make gains. In the past, it was generally believed that higher doses of SSRIs are needed for treating OCD than for treating major depressive disorder. For instance, greater improvement was seen with 250 to 400 mg/d of sertraline compared with 200 mg/d22 and with escitalopram after an increase of dose up to 50 mg/d.23 However, more recently, this notion of higher doses being necessary for treatment response has been called into question. For example, a study of escitalopram found similar responses to 10 mg/d vs 20 mg/d after 24 weeks.24 A meta-analysis of adult studies of SSRIs for OCD supported higher doses as being more effective, but noted that the drop-out rate from treatment was greater in patients treated with higher doses.25 As a note of caution, long-term, high-dose maintenance therapy increases the risk of adverse reactions.26

Following a failed treatment with a first SSRI, it remains debatable as to what ought to be the second pharmacologic treatment. Although clomipramine is often reserved for treatment after 2 failed trials of an SSRI due to its greater risk of adverse effects, in an open-label study, switching from an SSRI to clomipramine led to greater response than switching from one SSRI to another.27 On the other hand, while meta-analyses have reported greater treatment effect for oral clomipramine than for SSRIs, direct head-to-head comparisons have not supported this notion.28 To get the best of both worlds, some clinicians employ a strategy of combining clomipramine with an SSRI, while monitoring for adverse effects and interactions such as serotonin syndrome.29-31

Benzodiazepines. Although benzodiazepines are useful for brief treatment of an anxiety disorder (eg, for a person with a fear of heights who needs to take an airplane),32 they have not been shown to be effective for OCD33 or as augmentation to an SSRI.34

N-acetylcysteine (NAC). Two RCTs of adults with OCD who received adjunctive NAC, 3 g/d in divided doses, found no significant difference in the treatment arms by the conclusion of 16 weeks—either both groups improved, or both groups failed to improve.35,36 In a 10-week study of patients with moderate to severe OCD symptoms, NAC, 2 g/d, as augmentation to fluvoxamine, 200 mg/d, showed a significant time x interaction in the treatment group.37 No follow-up information is available, however.

In a multicenter RCT of NAC given to children and adolescents with OCD as augmentation to citalopram, symptoms decreased and the quality-of-life score improved, with a large treatment effect size in the NAC group.38 However, in a study aimed at examining NAC in youth with Tourette syndrome, OCD symptoms were measured as a secondary outcome and there was no benefit of NAC over placebo.39

Memantine. Four 8- to 12-week RCTs in adults with OCD favored adjunctive memantine, 20 mg/d, taken with an SSRI, over placebo.40-43 A small study suggests that patients with OCD may be more likely to respond to memantine than patients with generalized anxiety disorder.44 Case reports have noted that memantine has been beneficial for pediatric patients with refractory OCD.45

Continue to: Topiramate

Topiramate. Three 12-week RCTs examined topiramate augmentation at 100 to 400 mg/d in patients with OCD who had failed at least 1 previous trial of an SSRI. The earliest study was most encouraging: Y-BOCS scores decreased by 32% in the topiramate group but by only 2.4% in the placebo group.46 However, the other 2 studies found no difference in the final OCD symptom severity score between active treatment and placebo groups,47,48 and the use of topiramate, particularly at higher doses, was limited by its adverse effects.

Lamotrigine. Initially, lamotrigine augmentation of SSRIs in OCD did not appear to be helpful.49 More recently, several case studies reported that lamotrigine, 100 to 200 mg/d, added to paroxetine or clomipramine, resulted in dramatic improvement in Y-BOCS scores for patients with long-standing refractory symptoms.50,51 In a retrospective review of 22 patients who received augmentation with lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, 20 had a significant response; the mean decrease in Y-BOCS score was 67%.52 Finally, in a 16-week RCT, lamotrigine, 100 mg/d, added to an SSRI led to a significant decrease in both Y-BOCS score and depressive symptoms while also improving semantic fluency.53

Ketamine. Ketamine is drawing increased attention for its nearly instantaneous antidepressant effect that lasts for up to 2 weeks after a single infusion.54 In a study of 15 medication-free adults with continuous intrusive obsessions, 4 of 8 patients who received a single IV infusion of ketamine, 0.5 mg/kg, met the criteria for treatment response (>35% reduction in Y-BOCS score measured 1 week later); none of the patients who received a placebo infusion of saline met this criteria.55 A small open-label trial of 10 treatment-refractory patients found that an infusion of ketamine, 0.5 mg/kg, was beneficial for comorbid depression but had only a minimal effect on OCD symptoms measured 3 days post-infusion.56 A short-term follow-up on these patients revealed dysphoria in some responders.57

D-cycloserine. The idea of using a pharmacologic agent to increase the speed or efficacy of behavioral therapy is intriguing. Proof of concept was demonstrated in a study that found that giving D-cycloserine prior to computerized exposure therapy significantly improved clinical response in patients with acrophobia.58 However, using this approach to treating OCD netted mixed results; D-cycloserine was found to be most helpful during early stages of treatment.59,60

Table 3 outlines the mechanisms of action and common uses for NAC, memantine, ketamine, topiramate, lamotrigine, and D-cycloserine. Table 4 summarizes the literature on the efficacy of some of the augmentation strategies for treating OCD described in this article.

Continue to: Alternative strategies

Alternative strategies

Augmentation strategies with neuroleptics,61 transcranial magnetic stimulation,62 and deep brain stimulation63 have recently been reviewed. Space limitations preclude a comprehensive review of these strategies, but in a cross-sectional study of augmentation strategies in OCD, no difference was found in terms of symptom severity between those prescribed SSRI monotherapy or augmentation with neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, or antidepressants.64

CASE CONTINUED

Progress in CBT

Mr. S agrees to a trial of NAC as an augmentation strategy, but after 8 weeks of treatment with NAC, 600 mg twice daily, his Y-BOCS had declined by only 2 points. He also complains of nausea and does not want to increase the dose. You discontinue NAC and opt to further explore his reaction to CBT. Mr. S shares that he has been seeing his psychologist only once every 3 weeks because he does not want to miss work. You encourage him to increase to weekly CBT sessions, and you obtain his permission to contact his therapist and his family members. Fortunately, his therapist is highly qualified, but unfortunately, Mr. S’s father has been sending him multiple critical emails about not advancing at his job and for being “lazy” at work. You schedule a session with Mr. S and his father. Great progress is made after Mr. S and his father both share their frustrations and come to understand and appreciate each other’s struggles. Four weeks later, after weekly CBT appointments, Mr. S has a Y-BOCS of 18 and spends <2 hours/d checking emails for errors and apologizing.

Bottom Line

It is unrealistic to expect OCD symptoms to be cured. Many ‘treatment-resistant’ patients have not received properly delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy, and this first-line treatment modality should be considered in every eligible patient, and augmented with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) when needed. Glutamatergic agents, in turn, can augment SSRIs.

Related Resources

- Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. https://iocdf.org/ wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Assessment-Tools.pdf.

- The International OCD Foundation. https://iocdf.org.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Ketamine • Ketalar

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Memantine • Namenda

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Topiramate • Topomax

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Koran LM, Hanna GL, Hollander E, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry; 2007;164(suppl 7):5-53.

3. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98-113.

4. Bystritsky A, Munford PR, Rosen RM, et al. A preliminary study of partial hospital management of severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(2):170-174.

5. Calvocoressi L, McDougle CI, Wasylink S, et al. Inpatient treatment of patients with severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(12):1150-1154.

6. Eddy KT, Dutra L, Bradley R, et al. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(8):1011-1030.

7. Abramowitz JS. The psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(7):407-416.

8. Simpson HB, Huppert JD, Petkova E, et al. Response versus remission in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(2):269-276.

9. Marques L, LeBlanc NJ, Weingarden HM, et al. Barriers to treatment and service utilization in an internet sample of individuals with obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(5):470-475.

10. Goodwin R, Koenen KC, Hellman F, et al. Helpseeking and access to mental health treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(2):143-149.

11. Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, et al. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):858-866.

12. Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, et al. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(5):403-439.

13. Lovell K, Bee P. Implementing the NICE OCD/BDD guidelines. Psychol Psychother. 2008;81(Pt 4):365-376.

14. Bandelow B, Sher L, Bunevicius R, et al. Guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2012;16(2):77-84.

15. Soomro GM, Altman D, Rajagopal S, et al. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus placebo for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001765.

16. Pittenger C, Bloch MH. Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(3):375-391.

17. Bloch MH, Storch EA. Assessment and management of treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(4):251-262.

18. Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969-1976.

19. March JS, Mulle K. OCD in children and adolescents: a cognitive-behavioral treatment manual. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998.

20. Marks IM. Fears, phobias, and rituals: Panic, anxiety, and their disorders. 1987, New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1987.

21. Ale CM, McCarthy DM, Rothschild LM, et al. Components of cognitive behavioral therapy related to outcome in childhood anxiety disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2015;18(3):240-251.

22. Ninan PT, Koran LM, Kiev A, et al. High-dose sertraline strategy for nonresponders to acute treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a multicenter double-blind trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(1):15-22.

23. Rabinowitz I, Baruch Y, Barak Y. High-dose escitalopram for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(1):49-53.

24. Stein DJ, Andersen EW, Tonnoir B, et al. Escitalopram in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, paroxetine-referenced, fixed-dose, 24-week study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(4):701-711.

25. Bloch MH, McGuire J, Landeros-Weisenberger A, et al. Meta-analysis of the dose-response relationship of SSRI in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(8):850-855.

26. Sayyah M, Majzoob S, Sayyah M. Metabolic and toxicological considerations for obsessive-compulsive disorder drug therapy. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9(6):657-673.

27. Hollander E, Bienstock CA, Koran LM, et al. Refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: state-of-the-art treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(suppl 6):20-29.

28. Fineberg NA, Gale TM. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(1):107-129.

29. Marazziti D, Golia F, Consoli G, et al. Effectiveness of long-term augmentation with citalopram to clomipramine in treatment-resistant OCD patients. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):971-976.

30. Browne M, Horn E, Jones TT. The benefits of clomipramine-fluoxetine combination in obsessive compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 1993;38(4):242-243.

31. Ravizza L, Barzega G, Bellino S, et al. Drug treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): long-term trial with clomipramine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1996;32(1):167-173.

32. Koen N, Stein DJ. Pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders: a critical review. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(4):423-437.

33. Hollander E, Kaplan A, Stahl SM. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of clonazepam in obsessive-compulsive disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2003;4(1):30-34.

34. Crockett BA, Churchill E, Davidson JR. A double-blind combination study of clonazepam with sertraline in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16(3):127-132.

35. Costa DLC, Diniz JB, Requena G, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of n-acetylcysteine augmentation for treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(7):e766-e773.

36. Sarris J, Oliver G, Camfield DA, et al. N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a 16-week, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study. CNS Drugs. 2015;29(9):801-809.

37. Paydary K, Akamaloo A, Ahmadipour A, et al. N-acetylcysteine augmentation therapy for moderate-to-severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(2):214-219.

38. Ghanizadeh A, Mohammadi MR, Bahraini S, et al. Efficacy of N-acetylcysteine augmentation on obsessive compulsive disorder: a multicenter randomized double blind placebo controlled clinical trial. Iran J Psychiatry. 2017;12(2):134-141.

39. Bloch MH, Panza KE, Yaffa A, et al. N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of pediatric tourette syndrome: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled add-on trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(4):327-334.

40. Ghaleiha A, Entezari N, Modabbernia A, et al. Memantine add-on in moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(2):175-180.

41. Stewart SE, Jenike EA, Hezel DM, et al. A single-blinded case-control study of memantine in severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(1):34-39.

42. Modarresi A, Sayyah M, Razooghi S, et al. Memantine augmentation improves symptoms in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-120268. [Epub ahead of print].

43. Haghighi M, Jahangard L, Mohammad-Beigi H, et al. In a double-blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trial, adjuvant memantine improved symptoms in inpatients suffering from refractory obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD). Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;228(4):633-640.

44. Feusner JD, Kerwin L, Saxena S, et al. Differential efficacy of memantine for obsessive-compulsive disorder vs. generalized anxiety disorder: an open-label trial. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2009;42(1):81-93.

45. Hezel DM, Beattie K, Stewart SE. Memantine as an augmenting agent for severe pediatric OCD. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):237.

46. Mowla A, Khajeian AM, Sahraian A, et al. topiramate augmentation in resistant ocd: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(11):613-617.

47. Berlin H, Koran LM, Jenike MA, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):716-721.

48. Afshar H, Akuchekian S, Mahaky B, et al. Topiramate augmentation in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19(10):976-981.

49. Kumar TC, Khanna S. Lamotrigine augmentation of serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(3):527-528.

50. Arrojo-Romero M, Tajes Alonso M, de Leon J. Lamotrigine augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in severe and long-term treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2013;2013:612459.

51. Uzun O. Lamotrigine as an augmentation agent in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a case report. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(3):425-427.

52. Hussain A, Dar MA, Wani RA, et al. Role of lamotrigine augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: a retrospective case review from South Asia. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37(2):154-158.

53. Bruno A, Micò U, Pandolfo G, et al. Lamotrigine augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(11):1456-1462.

54. Krystal JH, Sanacora G, Duman RS. Rapid-acting glutamatergic antidepressants: the path to ketamine and beyond. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):113311-41.

55. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. Randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: proof-of-concept. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(12):2475-2483.

56. Bloch MH, Wasylink S, Landeros-Weisenberger A,, et al. Effects of ketamine in treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(11):964-970.

57. Niciu MJ, Grunschel BD, Corlett PR, et al. Two cases of delayed-onset suicidal ideation, dysphoria and anxiety after ketamine infusion in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and a history of major depressive disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(7):651-654.

58. Ressler KJ, Rothbaum BO, Tannenbaum L, et al. Cognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: use of D-cycloserine in phobic individuals to facilitate extinction of fear. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1136-1144.

59. Norberg MM, Krystal JH, Tolin DF. A meta-analysis of D-cycloserine and the facilitation of fear extinction and exposure therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(12):1118-1126.

60. Xia J, Du Y, Han J, et al. D-cycloserine augmentation in behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:2101-2117.

61. Veale D, Miles S, Smallcombe N, et al. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in SSRI treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:317.

62. Guo Q, Li C, Wang J. Updated review on the clinical use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in psychiatric disorders. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33(6):747-756.

63. Naesström, M, Blomstedt P, Bodlund O. A systematic review of psychiatric indications for deep brain stimulation, with focus on major depressive and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 2016;70(7):483-491.

64. Van Ameringen M, Simpson W, Patterson B, et al. Pharmacological treatment strategies in obsessive compulsive disorder: A cross-sectional view in nine international OCD centers. J Psychopharmacol, 2014;28(6):596-602.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Koran LM, Hanna GL, Hollander E, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry; 2007;164(suppl 7):5-53.

3. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98-113.

4. Bystritsky A, Munford PR, Rosen RM, et al. A preliminary study of partial hospital management of severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(2):170-174.

5. Calvocoressi L, McDougle CI, Wasylink S, et al. Inpatient treatment of patients with severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(12):1150-1154.

6. Eddy KT, Dutra L, Bradley R, et al. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(8):1011-1030.

7. Abramowitz JS. The psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(7):407-416.

8. Simpson HB, Huppert JD, Petkova E, et al. Response versus remission in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(2):269-276.

9. Marques L, LeBlanc NJ, Weingarden HM, et al. Barriers to treatment and service utilization in an internet sample of individuals with obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(5):470-475.

10. Goodwin R, Koenen KC, Hellman F, et al. Helpseeking and access to mental health treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(2):143-149.

11. Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, et al. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):858-866.

12. Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, et al. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(5):403-439.

13. Lovell K, Bee P. Implementing the NICE OCD/BDD guidelines. Psychol Psychother. 2008;81(Pt 4):365-376.

14. Bandelow B, Sher L, Bunevicius R, et al. Guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2012;16(2):77-84.

15. Soomro GM, Altman D, Rajagopal S, et al. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus placebo for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001765.

16. Pittenger C, Bloch MH. Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(3):375-391.

17. Bloch MH, Storch EA. Assessment and management of treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(4):251-262.

18. Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969-1976.

19. March JS, Mulle K. OCD in children and adolescents: a cognitive-behavioral treatment manual. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998.

20. Marks IM. Fears, phobias, and rituals: Panic, anxiety, and their disorders. 1987, New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1987.

21. Ale CM, McCarthy DM, Rothschild LM, et al. Components of cognitive behavioral therapy related to outcome in childhood anxiety disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2015;18(3):240-251.

22. Ninan PT, Koran LM, Kiev A, et al. High-dose sertraline strategy for nonresponders to acute treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a multicenter double-blind trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(1):15-22.

23. Rabinowitz I, Baruch Y, Barak Y. High-dose escitalopram for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(1):49-53.

24. Stein DJ, Andersen EW, Tonnoir B, et al. Escitalopram in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, paroxetine-referenced, fixed-dose, 24-week study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(4):701-711.

25. Bloch MH, McGuire J, Landeros-Weisenberger A, et al. Meta-analysis of the dose-response relationship of SSRI in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(8):850-855.

26. Sayyah M, Majzoob S, Sayyah M. Metabolic and toxicological considerations for obsessive-compulsive disorder drug therapy. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9(6):657-673.

27. Hollander E, Bienstock CA, Koran LM, et al. Refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: state-of-the-art treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(suppl 6):20-29.

28. Fineberg NA, Gale TM. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(1):107-129.

29. Marazziti D, Golia F, Consoli G, et al. Effectiveness of long-term augmentation with citalopram to clomipramine in treatment-resistant OCD patients. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):971-976.

30. Browne M, Horn E, Jones TT. The benefits of clomipramine-fluoxetine combination in obsessive compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 1993;38(4):242-243.

31. Ravizza L, Barzega G, Bellino S, et al. Drug treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): long-term trial with clomipramine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1996;32(1):167-173.

32. Koen N, Stein DJ. Pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders: a critical review. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(4):423-437.

33. Hollander E, Kaplan A, Stahl SM. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of clonazepam in obsessive-compulsive disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2003;4(1):30-34.

34. Crockett BA, Churchill E, Davidson JR. A double-blind combination study of clonazepam with sertraline in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16(3):127-132.

35. Costa DLC, Diniz JB, Requena G, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of n-acetylcysteine augmentation for treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(7):e766-e773.

36. Sarris J, Oliver G, Camfield DA, et al. N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a 16-week, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study. CNS Drugs. 2015;29(9):801-809.

37. Paydary K, Akamaloo A, Ahmadipour A, et al. N-acetylcysteine augmentation therapy for moderate-to-severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(2):214-219.

38. Ghanizadeh A, Mohammadi MR, Bahraini S, et al. Efficacy of N-acetylcysteine augmentation on obsessive compulsive disorder: a multicenter randomized double blind placebo controlled clinical trial. Iran J Psychiatry. 2017;12(2):134-141.

39. Bloch MH, Panza KE, Yaffa A, et al. N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of pediatric tourette syndrome: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled add-on trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(4):327-334.

40. Ghaleiha A, Entezari N, Modabbernia A, et al. Memantine add-on in moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(2):175-180.

41. Stewart SE, Jenike EA, Hezel DM, et al. A single-blinded case-control study of memantine in severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(1):34-39.

42. Modarresi A, Sayyah M, Razooghi S, et al. Memantine augmentation improves symptoms in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-120268. [Epub ahead of print].

43. Haghighi M, Jahangard L, Mohammad-Beigi H, et al. In a double-blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trial, adjuvant memantine improved symptoms in inpatients suffering from refractory obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD). Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;228(4):633-640.