User login

Value-based payment: What does it mean, and how can ObGyns get out ahead?

For ObGyns to be successful, understanding the basics of quality and cost measurement is essential, along with devoting more attention to what they are being evaluated on and held accountable for. But how will ObGyns be impacted by the push to incentivize them for delivering value in their work?

Although much of health care policy has become politically divisive lately, one area of agreement is that, in the United States, we have unsustainable health costs and the exorbitant amount our country pays for health care does not translate to improved outcomes. The United States spends more than most other developed nations on health care (roughly, $9,403 per capita in 2014) but has some of the lowest life expectancies, along with the highest maternal and infant mortality rates, compared with peer nations.1–4

One of the key culprits in our health system’s inefficiencies is the fee-for-service payment model. Fee-for-service incentivizes the delivery of a high volume of care without any way to determine whether that care is achieving the desired outcomes of improved health and quality of life. Not only does fee-for-service drive up the volume of care but it also rewards the delivery of high-cost services, regardless of whether those services provide what is best for the patient.

During the previous administration, Secretary of Health and Human Services Sylvia Mathews Burwell set goals for moving away from fee-for-service in Medicare and in the health system more broadly. Congress also passed legislation that provides incentives for Medicare providers to transition away from fee-for-service with the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA). While fee-for-service remains the predominant form of payment for many physicians, value-based payment arrangements are gaining a toehold. In 2014, 86% of physicians reported working in a practice receiving fee-for-service. Those fees accounted for nearly 72% of revenue.5 This percentage likely will continue to decrease over the next few years as government and private payers seek to promote value-based payment systems.

Assessing quality

“Value” in the context of health care is often defined as quality or outcomes relative to costs.6 Before payers can reward value, there must be measurement of performance to determine the quality of care being delivered. Quality measures are tools to help quantify access to care, processes, outcomes, patient experience, and organizational structure within the health care system. ObGyns likely encounter process, outcome, and patient experience measures most frequently in their practice.

Although outcome measures are generally held as the gold standard for quality measurement, they are often hard to obtain—either because of issues of temporality and rarity of events or because the data are hard to capture through existing formats. In lieu of measuring outcomes, process measures are often used to determine whether certain services that are known to be tied to desired health outcomes were delivered. Patient experience measures are also rising in popularity and are seen as a critical tool to ensuring that care that purports to be patient-centered actually is so.

Measures are specified to different levels of accountability, ranging from the individual physician all the way to the population. Some measures also can be specified at multiple levels. One major concern is the problem of attribution—that is, the difficulty of assigning who is primarily responsible for a specific quality metric result. Because obstetrics and gynecology is an increasingly team-based specialty, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that measures that are used to reward or penalize providers should reflect performance at the care team or practice level, not at the individual physician or health care provider level.7 As consolidation of providers continues, it is expected that team-based care will increase and that the use of advanced practice providers will increase.8

Data to determine performance can come from a variety of sources, including claims, electronic health records (EHRs), paper medical record abstraction, birth certificates, registries, surveys, and separate reporting mechanisms. There are pros and cons of these various sources. Because administrative claims data are so easily obtainable, many measures have been developed based on this data source, but there are significant limitations to assessments made with such data. These limitations include inherent problems with translating clinical diagnoses into specific codes and inadequate documentation to support particular diagnoses and procedure codes.9 Claims data are limited by what physicians and other health care providers code for in their claims, making proper coding an essential skill for ObGyns to master.

Although there has been an increase in measures that rely on clinical data found in EHRs and registries—which are more robust and capture a wider breadth of indicators—claims-based measures still form the basis for many reporting programs because of standardization and ease of access to data. Data quality will become increasingly more important in a value-based payment world because completeness, risk adjustment, and specificity will be determined by the data recorded. This need for data quality will require that improvements be made in the user interface of EHRs and that providers pay specific attention to making sure their documentation is complete. New designs for EHRs should assist in that task, and data extraction should become a by-product of documentation.10

Read about alternative payment models and how ObGyns can succeed.

Paying for value

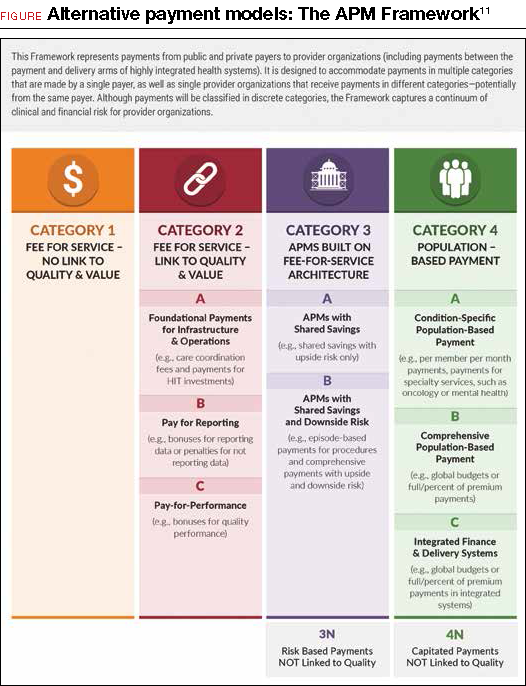

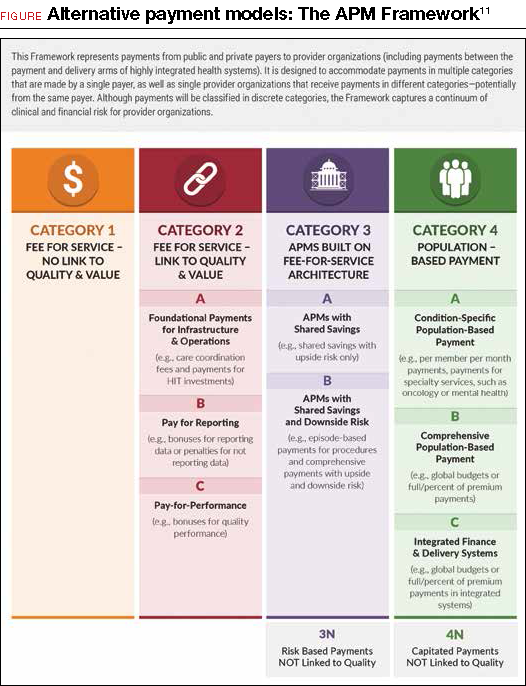

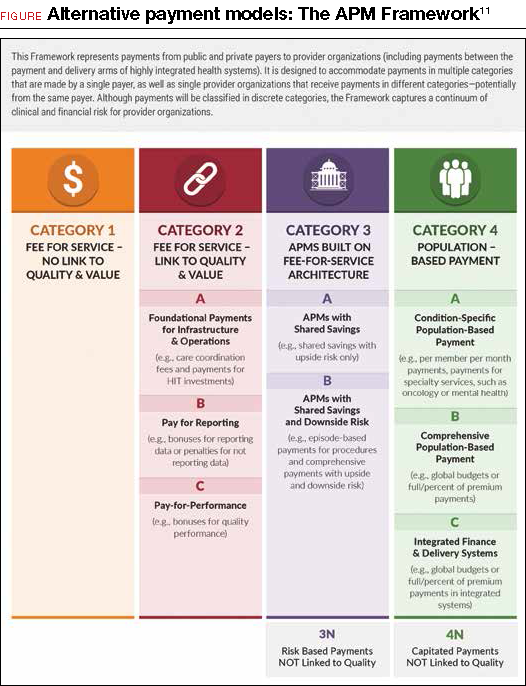

In an attempt to move away from fee-for-service medicine, payers and employers are adopting alternative payment models (APMs) that are intended to reward physicians and other health care providers for delivering value. Although APMs can be a catchall term, the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network (LAN), a multi-stakeholder collaborative convened by the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, has laid out a framework for the different types of APMs11 (FIGURE). This framework provides a common reference point for concepts related to value-based care.

Although ACOG does not endorse all the concepts and principles included in the LAN white paper, it does support moving away from fee-for-service payments that lack any link to quality or outcomes. Originally, the LAN envisioned that all physicians, providers, and hospital systems would move in the direction of adopting Category 4 APMs, but in the recent “refresh” of the LAN’s white paper, the authors recognized that not all entities will be able to move toward population-based payments—nor will it be beneficial for all providers to do so. ACOG agrees that not all ObGyns will be able to thrive under population-based payments, so we must lead the way in developing models and measures that appropriately assess value in the care that ObGyns provide.

ACOG has undertaken its first foray into value-based payments by developing an “episode group” related to benign hysterectomy, with attendant quality measures. (An episode group is a collection of services associated with treating a condition or performing a procedure that are both clinically and temporally related.) The goal in creating episode groups is to create alignment across payers so that ObGyns are not faced with multitudinous payer-specific metrics and reporting requirements. As the benign hysterectomy episode group is refined and adopted by payers, ACOG plans to expand to other treatments and, eventually, develop condition-based episode groups that incentivize the most appropriate treatment options for patients.

Current forms of APMs are mostly Category 2 and 3 models. Rates of proper screening for cervical and breast cancer have been used as performance metrics for bonus payments. Major payers have pushed specific metrics as cutoffs for limiting narrow networks.12 For example, Covered California, the state health care exchange, has set a nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean rate of 23.9% by 2018 as a necessary standard for inclusion of a hospital’s entire services (obstetric and nonobstetric) in their network. Episode group payments for total obstetric care included in the episode routine services, such as ultrasonography, have been previously utilized to discourage overutilization.

Such payment incentives can lead to underutilization of resources, however, which might lead to poorer outcomes and therefore result in overall greater cost. For example, poor screening for fetal anomalies or poorly managed medical conditions such as diabetes can lead to markedly increased costs in neonatal management. Therefore, some authorities have proposed tying incentives for obstetric care to performance outcome measures in neonatal care as a method of finding “sweet spots” for utilization of complex services and episode groups. Such models will depend on more robust clinical information sources and standardization.8

How can ObGyns succeed?

So what does success look like under these value-based payments for ObGyns? This is new territory, in a rapidly changing environment in which providers who flourished under the fee-for-service system will only survive under the new system if they become knowledgeable about the nuances of the new payment methods. Providers should understand that success is going to be defined as reaching the “Triple Aim”13 of improving the health of the population, containing costs, and improving the experience of health care.

Practice patient-centered care. One way to better position yourself is to focus on delivering patient-centered care and improving customer service in your practice. By implementing patient satisfaction surveys, you can identify where you are most vulnerable. One option is to utilize the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Clinician and Group Survey, developed by the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. However, there are other assessment tools available, and you should investigate what works best for your practice.

Code properly. Another key to making sure you are in an optimal position is to properly document and code the services you deliver. Accurately capturing the clinical complexity of your patients will help down the road with risk adjustment and risk stratification for cost and quality measures. Many payment models, including episode groups, are built on the fee-for-service system, so coding for services is still important in the transition to alternative models. Modern EHRs are building new tools to assist clinician documentation, such as tools that aid coding. Carefully groomed and up-to-date problem lists can help providers keep track of appropriate testing and screening by enabling decision support tools that are imbedded in the systems. Although upgrading can be expensive, especially for small group practices, the development of “software as a service” or cloud-based EHRs will likely drive individual costs down.10

One example of point-of-care decision support that ACOG is spearheading to support our Fellows is the ACOG Prenatal Record (APR) by Dorsata.14 The APR is an application designed by ObGyns to work seamlessly with an existing EHR system to improve clinical workflow, save time, and help ObGyns support high-quality prenatal outcomes. The APR uses the same simplicity, flexibility, and familiarity of the original paper-based flowsheet, but in an electronic format to integrate ACOG guidance, which provides a more robust solution. The APR uses information such as gestational age, pregnancy history, the problem list, and other risk factors to provide patient and visit-specific care plans based on ACOG clinical practice guidelines. It was designed to help reduce physician burden by creating an easy-to-navigate electronic flowsheet that provides everything ObGyns need to know about each patient, succinctly captured in a single view.

ACOG also offers comprehensive coding workshops across the country and webinars on special coding topics to help Fellows learn to properly code their services. Availing yourself of these educational opportunities now so that you are better prepared to transition to value-based payment is a great way to ensure success in the future.

Chances are that some of your payers are already requiring you to report on metrics or tracking your performance using claims data. Pay attention to the performance measures that you are being held accountable for by payers when you review your payer contracts. Make sure you understand how your patients may fall into and out of the measure numerators and denominators. Ask yourself whether these metrics are ones that you can reasonably influence and that are within your control.

Of course, you can also reach out to ACOG for help. We are here to educate, inform, and guide you on these changes and provide assistance to ensure your success. Send inquiries to: [email protected].

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- The World Bank. Health expenditure per capita (current US $). 2017. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.PCAP?year_high_desc=true. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Gonzales S, Sawyer B. How does U.S. life expectancy compare to other countries? Peterson Center on Healthcare and the Kaiser Family Foundation. 2017. http://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/u-s-life-expectancy-compare-countries/?_sf_s=life#item-start. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/194254/1/9789241565141_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- MacDorman MF, Mathews TJ, Mohangoo AD, Zeitlin J. International comparisons of infant mortality and related factors: United States and Europe, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63(5):1-6.

- Kane, CK. American Medical Association Policy Research Perspectives. Payment and delivery in 2014: The prevalence of new models reported by physicians. 2015. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/member/health-policy/practicepay-prp2015_0.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477-2481.

- Task Force on Collaborative Practice. Collaboration in practice: Implementing team-based care. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2016. https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Collaboration-in-Practice-Implementing-Team-Based-Care. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Lagrew DC Jr, Jenkins TR. The future of obstetrics/gynecology in 2020: a clearer vision: finding true north and the forces of change. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):617-622.

- Riley GF. Administrative and claims records as sources of health care cost data. Med Care. 2009;47(7 suppl 1):S51-S55.

- Lagrew DC Jr, Jenkins TR. The future of obstetrics/gynecology in 2020: a clearer vision. Transformational forces and thriving in the new system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(1):28-33.

- US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network. Alternative Payment Models (APM) Framework. 2017. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Health-Care-Payment-Learning-and-Action-Network/. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Morse S. Covered California will exclude hospitals with high rates of C-sections. Healthcare Finance. 2016. http://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/covered-california-will-exclude-hospitals-high-rates-c-sections. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim. 2017. http://www.ihi.org/engage/initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- A pregnancy app for your EHR. 2017. https://www.dorsata.com/. Accessed December 4, 2017.

For ObGyns to be successful, understanding the basics of quality and cost measurement is essential, along with devoting more attention to what they are being evaluated on and held accountable for. But how will ObGyns be impacted by the push to incentivize them for delivering value in their work?

Although much of health care policy has become politically divisive lately, one area of agreement is that, in the United States, we have unsustainable health costs and the exorbitant amount our country pays for health care does not translate to improved outcomes. The United States spends more than most other developed nations on health care (roughly, $9,403 per capita in 2014) but has some of the lowest life expectancies, along with the highest maternal and infant mortality rates, compared with peer nations.1–4

One of the key culprits in our health system’s inefficiencies is the fee-for-service payment model. Fee-for-service incentivizes the delivery of a high volume of care without any way to determine whether that care is achieving the desired outcomes of improved health and quality of life. Not only does fee-for-service drive up the volume of care but it also rewards the delivery of high-cost services, regardless of whether those services provide what is best for the patient.

During the previous administration, Secretary of Health and Human Services Sylvia Mathews Burwell set goals for moving away from fee-for-service in Medicare and in the health system more broadly. Congress also passed legislation that provides incentives for Medicare providers to transition away from fee-for-service with the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA). While fee-for-service remains the predominant form of payment for many physicians, value-based payment arrangements are gaining a toehold. In 2014, 86% of physicians reported working in a practice receiving fee-for-service. Those fees accounted for nearly 72% of revenue.5 This percentage likely will continue to decrease over the next few years as government and private payers seek to promote value-based payment systems.

Assessing quality

“Value” in the context of health care is often defined as quality or outcomes relative to costs.6 Before payers can reward value, there must be measurement of performance to determine the quality of care being delivered. Quality measures are tools to help quantify access to care, processes, outcomes, patient experience, and organizational structure within the health care system. ObGyns likely encounter process, outcome, and patient experience measures most frequently in their practice.

Although outcome measures are generally held as the gold standard for quality measurement, they are often hard to obtain—either because of issues of temporality and rarity of events or because the data are hard to capture through existing formats. In lieu of measuring outcomes, process measures are often used to determine whether certain services that are known to be tied to desired health outcomes were delivered. Patient experience measures are also rising in popularity and are seen as a critical tool to ensuring that care that purports to be patient-centered actually is so.

Measures are specified to different levels of accountability, ranging from the individual physician all the way to the population. Some measures also can be specified at multiple levels. One major concern is the problem of attribution—that is, the difficulty of assigning who is primarily responsible for a specific quality metric result. Because obstetrics and gynecology is an increasingly team-based specialty, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that measures that are used to reward or penalize providers should reflect performance at the care team or practice level, not at the individual physician or health care provider level.7 As consolidation of providers continues, it is expected that team-based care will increase and that the use of advanced practice providers will increase.8

Data to determine performance can come from a variety of sources, including claims, electronic health records (EHRs), paper medical record abstraction, birth certificates, registries, surveys, and separate reporting mechanisms. There are pros and cons of these various sources. Because administrative claims data are so easily obtainable, many measures have been developed based on this data source, but there are significant limitations to assessments made with such data. These limitations include inherent problems with translating clinical diagnoses into specific codes and inadequate documentation to support particular diagnoses and procedure codes.9 Claims data are limited by what physicians and other health care providers code for in their claims, making proper coding an essential skill for ObGyns to master.

Although there has been an increase in measures that rely on clinical data found in EHRs and registries—which are more robust and capture a wider breadth of indicators—claims-based measures still form the basis for many reporting programs because of standardization and ease of access to data. Data quality will become increasingly more important in a value-based payment world because completeness, risk adjustment, and specificity will be determined by the data recorded. This need for data quality will require that improvements be made in the user interface of EHRs and that providers pay specific attention to making sure their documentation is complete. New designs for EHRs should assist in that task, and data extraction should become a by-product of documentation.10

Read about alternative payment models and how ObGyns can succeed.

Paying for value

In an attempt to move away from fee-for-service medicine, payers and employers are adopting alternative payment models (APMs) that are intended to reward physicians and other health care providers for delivering value. Although APMs can be a catchall term, the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network (LAN), a multi-stakeholder collaborative convened by the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, has laid out a framework for the different types of APMs11 (FIGURE). This framework provides a common reference point for concepts related to value-based care.

Although ACOG does not endorse all the concepts and principles included in the LAN white paper, it does support moving away from fee-for-service payments that lack any link to quality or outcomes. Originally, the LAN envisioned that all physicians, providers, and hospital systems would move in the direction of adopting Category 4 APMs, but in the recent “refresh” of the LAN’s white paper, the authors recognized that not all entities will be able to move toward population-based payments—nor will it be beneficial for all providers to do so. ACOG agrees that not all ObGyns will be able to thrive under population-based payments, so we must lead the way in developing models and measures that appropriately assess value in the care that ObGyns provide.

ACOG has undertaken its first foray into value-based payments by developing an “episode group” related to benign hysterectomy, with attendant quality measures. (An episode group is a collection of services associated with treating a condition or performing a procedure that are both clinically and temporally related.) The goal in creating episode groups is to create alignment across payers so that ObGyns are not faced with multitudinous payer-specific metrics and reporting requirements. As the benign hysterectomy episode group is refined and adopted by payers, ACOG plans to expand to other treatments and, eventually, develop condition-based episode groups that incentivize the most appropriate treatment options for patients.

Current forms of APMs are mostly Category 2 and 3 models. Rates of proper screening for cervical and breast cancer have been used as performance metrics for bonus payments. Major payers have pushed specific metrics as cutoffs for limiting narrow networks.12 For example, Covered California, the state health care exchange, has set a nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean rate of 23.9% by 2018 as a necessary standard for inclusion of a hospital’s entire services (obstetric and nonobstetric) in their network. Episode group payments for total obstetric care included in the episode routine services, such as ultrasonography, have been previously utilized to discourage overutilization.

Such payment incentives can lead to underutilization of resources, however, which might lead to poorer outcomes and therefore result in overall greater cost. For example, poor screening for fetal anomalies or poorly managed medical conditions such as diabetes can lead to markedly increased costs in neonatal management. Therefore, some authorities have proposed tying incentives for obstetric care to performance outcome measures in neonatal care as a method of finding “sweet spots” for utilization of complex services and episode groups. Such models will depend on more robust clinical information sources and standardization.8

How can ObGyns succeed?

So what does success look like under these value-based payments for ObGyns? This is new territory, in a rapidly changing environment in which providers who flourished under the fee-for-service system will only survive under the new system if they become knowledgeable about the nuances of the new payment methods. Providers should understand that success is going to be defined as reaching the “Triple Aim”13 of improving the health of the population, containing costs, and improving the experience of health care.

Practice patient-centered care. One way to better position yourself is to focus on delivering patient-centered care and improving customer service in your practice. By implementing patient satisfaction surveys, you can identify where you are most vulnerable. One option is to utilize the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Clinician and Group Survey, developed by the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. However, there are other assessment tools available, and you should investigate what works best for your practice.

Code properly. Another key to making sure you are in an optimal position is to properly document and code the services you deliver. Accurately capturing the clinical complexity of your patients will help down the road with risk adjustment and risk stratification for cost and quality measures. Many payment models, including episode groups, are built on the fee-for-service system, so coding for services is still important in the transition to alternative models. Modern EHRs are building new tools to assist clinician documentation, such as tools that aid coding. Carefully groomed and up-to-date problem lists can help providers keep track of appropriate testing and screening by enabling decision support tools that are imbedded in the systems. Although upgrading can be expensive, especially for small group practices, the development of “software as a service” or cloud-based EHRs will likely drive individual costs down.10

One example of point-of-care decision support that ACOG is spearheading to support our Fellows is the ACOG Prenatal Record (APR) by Dorsata.14 The APR is an application designed by ObGyns to work seamlessly with an existing EHR system to improve clinical workflow, save time, and help ObGyns support high-quality prenatal outcomes. The APR uses the same simplicity, flexibility, and familiarity of the original paper-based flowsheet, but in an electronic format to integrate ACOG guidance, which provides a more robust solution. The APR uses information such as gestational age, pregnancy history, the problem list, and other risk factors to provide patient and visit-specific care plans based on ACOG clinical practice guidelines. It was designed to help reduce physician burden by creating an easy-to-navigate electronic flowsheet that provides everything ObGyns need to know about each patient, succinctly captured in a single view.

ACOG also offers comprehensive coding workshops across the country and webinars on special coding topics to help Fellows learn to properly code their services. Availing yourself of these educational opportunities now so that you are better prepared to transition to value-based payment is a great way to ensure success in the future.

Chances are that some of your payers are already requiring you to report on metrics or tracking your performance using claims data. Pay attention to the performance measures that you are being held accountable for by payers when you review your payer contracts. Make sure you understand how your patients may fall into and out of the measure numerators and denominators. Ask yourself whether these metrics are ones that you can reasonably influence and that are within your control.

Of course, you can also reach out to ACOG for help. We are here to educate, inform, and guide you on these changes and provide assistance to ensure your success. Send inquiries to: [email protected].

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

For ObGyns to be successful, understanding the basics of quality and cost measurement is essential, along with devoting more attention to what they are being evaluated on and held accountable for. But how will ObGyns be impacted by the push to incentivize them for delivering value in their work?

Although much of health care policy has become politically divisive lately, one area of agreement is that, in the United States, we have unsustainable health costs and the exorbitant amount our country pays for health care does not translate to improved outcomes. The United States spends more than most other developed nations on health care (roughly, $9,403 per capita in 2014) but has some of the lowest life expectancies, along with the highest maternal and infant mortality rates, compared with peer nations.1–4

One of the key culprits in our health system’s inefficiencies is the fee-for-service payment model. Fee-for-service incentivizes the delivery of a high volume of care without any way to determine whether that care is achieving the desired outcomes of improved health and quality of life. Not only does fee-for-service drive up the volume of care but it also rewards the delivery of high-cost services, regardless of whether those services provide what is best for the patient.

During the previous administration, Secretary of Health and Human Services Sylvia Mathews Burwell set goals for moving away from fee-for-service in Medicare and in the health system more broadly. Congress also passed legislation that provides incentives for Medicare providers to transition away from fee-for-service with the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA). While fee-for-service remains the predominant form of payment for many physicians, value-based payment arrangements are gaining a toehold. In 2014, 86% of physicians reported working in a practice receiving fee-for-service. Those fees accounted for nearly 72% of revenue.5 This percentage likely will continue to decrease over the next few years as government and private payers seek to promote value-based payment systems.

Assessing quality

“Value” in the context of health care is often defined as quality or outcomes relative to costs.6 Before payers can reward value, there must be measurement of performance to determine the quality of care being delivered. Quality measures are tools to help quantify access to care, processes, outcomes, patient experience, and organizational structure within the health care system. ObGyns likely encounter process, outcome, and patient experience measures most frequently in their practice.

Although outcome measures are generally held as the gold standard for quality measurement, they are often hard to obtain—either because of issues of temporality and rarity of events or because the data are hard to capture through existing formats. In lieu of measuring outcomes, process measures are often used to determine whether certain services that are known to be tied to desired health outcomes were delivered. Patient experience measures are also rising in popularity and are seen as a critical tool to ensuring that care that purports to be patient-centered actually is so.

Measures are specified to different levels of accountability, ranging from the individual physician all the way to the population. Some measures also can be specified at multiple levels. One major concern is the problem of attribution—that is, the difficulty of assigning who is primarily responsible for a specific quality metric result. Because obstetrics and gynecology is an increasingly team-based specialty, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that measures that are used to reward or penalize providers should reflect performance at the care team or practice level, not at the individual physician or health care provider level.7 As consolidation of providers continues, it is expected that team-based care will increase and that the use of advanced practice providers will increase.8

Data to determine performance can come from a variety of sources, including claims, electronic health records (EHRs), paper medical record abstraction, birth certificates, registries, surveys, and separate reporting mechanisms. There are pros and cons of these various sources. Because administrative claims data are so easily obtainable, many measures have been developed based on this data source, but there are significant limitations to assessments made with such data. These limitations include inherent problems with translating clinical diagnoses into specific codes and inadequate documentation to support particular diagnoses and procedure codes.9 Claims data are limited by what physicians and other health care providers code for in their claims, making proper coding an essential skill for ObGyns to master.

Although there has been an increase in measures that rely on clinical data found in EHRs and registries—which are more robust and capture a wider breadth of indicators—claims-based measures still form the basis for many reporting programs because of standardization and ease of access to data. Data quality will become increasingly more important in a value-based payment world because completeness, risk adjustment, and specificity will be determined by the data recorded. This need for data quality will require that improvements be made in the user interface of EHRs and that providers pay specific attention to making sure their documentation is complete. New designs for EHRs should assist in that task, and data extraction should become a by-product of documentation.10

Read about alternative payment models and how ObGyns can succeed.

Paying for value

In an attempt to move away from fee-for-service medicine, payers and employers are adopting alternative payment models (APMs) that are intended to reward physicians and other health care providers for delivering value. Although APMs can be a catchall term, the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network (LAN), a multi-stakeholder collaborative convened by the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, has laid out a framework for the different types of APMs11 (FIGURE). This framework provides a common reference point for concepts related to value-based care.

Although ACOG does not endorse all the concepts and principles included in the LAN white paper, it does support moving away from fee-for-service payments that lack any link to quality or outcomes. Originally, the LAN envisioned that all physicians, providers, and hospital systems would move in the direction of adopting Category 4 APMs, but in the recent “refresh” of the LAN’s white paper, the authors recognized that not all entities will be able to move toward population-based payments—nor will it be beneficial for all providers to do so. ACOG agrees that not all ObGyns will be able to thrive under population-based payments, so we must lead the way in developing models and measures that appropriately assess value in the care that ObGyns provide.

ACOG has undertaken its first foray into value-based payments by developing an “episode group” related to benign hysterectomy, with attendant quality measures. (An episode group is a collection of services associated with treating a condition or performing a procedure that are both clinically and temporally related.) The goal in creating episode groups is to create alignment across payers so that ObGyns are not faced with multitudinous payer-specific metrics and reporting requirements. As the benign hysterectomy episode group is refined and adopted by payers, ACOG plans to expand to other treatments and, eventually, develop condition-based episode groups that incentivize the most appropriate treatment options for patients.

Current forms of APMs are mostly Category 2 and 3 models. Rates of proper screening for cervical and breast cancer have been used as performance metrics for bonus payments. Major payers have pushed specific metrics as cutoffs for limiting narrow networks.12 For example, Covered California, the state health care exchange, has set a nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean rate of 23.9% by 2018 as a necessary standard for inclusion of a hospital’s entire services (obstetric and nonobstetric) in their network. Episode group payments for total obstetric care included in the episode routine services, such as ultrasonography, have been previously utilized to discourage overutilization.

Such payment incentives can lead to underutilization of resources, however, which might lead to poorer outcomes and therefore result in overall greater cost. For example, poor screening for fetal anomalies or poorly managed medical conditions such as diabetes can lead to markedly increased costs in neonatal management. Therefore, some authorities have proposed tying incentives for obstetric care to performance outcome measures in neonatal care as a method of finding “sweet spots” for utilization of complex services and episode groups. Such models will depend on more robust clinical information sources and standardization.8

How can ObGyns succeed?

So what does success look like under these value-based payments for ObGyns? This is new territory, in a rapidly changing environment in which providers who flourished under the fee-for-service system will only survive under the new system if they become knowledgeable about the nuances of the new payment methods. Providers should understand that success is going to be defined as reaching the “Triple Aim”13 of improving the health of the population, containing costs, and improving the experience of health care.

Practice patient-centered care. One way to better position yourself is to focus on delivering patient-centered care and improving customer service in your practice. By implementing patient satisfaction surveys, you can identify where you are most vulnerable. One option is to utilize the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Clinician and Group Survey, developed by the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. However, there are other assessment tools available, and you should investigate what works best for your practice.

Code properly. Another key to making sure you are in an optimal position is to properly document and code the services you deliver. Accurately capturing the clinical complexity of your patients will help down the road with risk adjustment and risk stratification for cost and quality measures. Many payment models, including episode groups, are built on the fee-for-service system, so coding for services is still important in the transition to alternative models. Modern EHRs are building new tools to assist clinician documentation, such as tools that aid coding. Carefully groomed and up-to-date problem lists can help providers keep track of appropriate testing and screening by enabling decision support tools that are imbedded in the systems. Although upgrading can be expensive, especially for small group practices, the development of “software as a service” or cloud-based EHRs will likely drive individual costs down.10

One example of point-of-care decision support that ACOG is spearheading to support our Fellows is the ACOG Prenatal Record (APR) by Dorsata.14 The APR is an application designed by ObGyns to work seamlessly with an existing EHR system to improve clinical workflow, save time, and help ObGyns support high-quality prenatal outcomes. The APR uses the same simplicity, flexibility, and familiarity of the original paper-based flowsheet, but in an electronic format to integrate ACOG guidance, which provides a more robust solution. The APR uses information such as gestational age, pregnancy history, the problem list, and other risk factors to provide patient and visit-specific care plans based on ACOG clinical practice guidelines. It was designed to help reduce physician burden by creating an easy-to-navigate electronic flowsheet that provides everything ObGyns need to know about each patient, succinctly captured in a single view.

ACOG also offers comprehensive coding workshops across the country and webinars on special coding topics to help Fellows learn to properly code their services. Availing yourself of these educational opportunities now so that you are better prepared to transition to value-based payment is a great way to ensure success in the future.

Chances are that some of your payers are already requiring you to report on metrics or tracking your performance using claims data. Pay attention to the performance measures that you are being held accountable for by payers when you review your payer contracts. Make sure you understand how your patients may fall into and out of the measure numerators and denominators. Ask yourself whether these metrics are ones that you can reasonably influence and that are within your control.

Of course, you can also reach out to ACOG for help. We are here to educate, inform, and guide you on these changes and provide assistance to ensure your success. Send inquiries to: [email protected].

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- The World Bank. Health expenditure per capita (current US $). 2017. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.PCAP?year_high_desc=true. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Gonzales S, Sawyer B. How does U.S. life expectancy compare to other countries? Peterson Center on Healthcare and the Kaiser Family Foundation. 2017. http://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/u-s-life-expectancy-compare-countries/?_sf_s=life#item-start. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/194254/1/9789241565141_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- MacDorman MF, Mathews TJ, Mohangoo AD, Zeitlin J. International comparisons of infant mortality and related factors: United States and Europe, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63(5):1-6.

- Kane, CK. American Medical Association Policy Research Perspectives. Payment and delivery in 2014: The prevalence of new models reported by physicians. 2015. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/member/health-policy/practicepay-prp2015_0.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477-2481.

- Task Force on Collaborative Practice. Collaboration in practice: Implementing team-based care. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2016. https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Collaboration-in-Practice-Implementing-Team-Based-Care. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Lagrew DC Jr, Jenkins TR. The future of obstetrics/gynecology in 2020: a clearer vision: finding true north and the forces of change. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):617-622.

- Riley GF. Administrative and claims records as sources of health care cost data. Med Care. 2009;47(7 suppl 1):S51-S55.

- Lagrew DC Jr, Jenkins TR. The future of obstetrics/gynecology in 2020: a clearer vision. Transformational forces and thriving in the new system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(1):28-33.

- US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network. Alternative Payment Models (APM) Framework. 2017. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Health-Care-Payment-Learning-and-Action-Network/. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Morse S. Covered California will exclude hospitals with high rates of C-sections. Healthcare Finance. 2016. http://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/covered-california-will-exclude-hospitals-high-rates-c-sections. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim. 2017. http://www.ihi.org/engage/initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- A pregnancy app for your EHR. 2017. https://www.dorsata.com/. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- The World Bank. Health expenditure per capita (current US $). 2017. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.PCAP?year_high_desc=true. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Gonzales S, Sawyer B. How does U.S. life expectancy compare to other countries? Peterson Center on Healthcare and the Kaiser Family Foundation. 2017. http://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/u-s-life-expectancy-compare-countries/?_sf_s=life#item-start. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/194254/1/9789241565141_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- MacDorman MF, Mathews TJ, Mohangoo AD, Zeitlin J. International comparisons of infant mortality and related factors: United States and Europe, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63(5):1-6.

- Kane, CK. American Medical Association Policy Research Perspectives. Payment and delivery in 2014: The prevalence of new models reported by physicians. 2015. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/member/health-policy/practicepay-prp2015_0.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477-2481.

- Task Force on Collaborative Practice. Collaboration in practice: Implementing team-based care. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2016. https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Collaboration-in-Practice-Implementing-Team-Based-Care. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Lagrew DC Jr, Jenkins TR. The future of obstetrics/gynecology in 2020: a clearer vision: finding true north and the forces of change. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):617-622.

- Riley GF. Administrative and claims records as sources of health care cost data. Med Care. 2009;47(7 suppl 1):S51-S55.

- Lagrew DC Jr, Jenkins TR. The future of obstetrics/gynecology in 2020: a clearer vision. Transformational forces and thriving in the new system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(1):28-33.

- US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network. Alternative Payment Models (APM) Framework. 2017. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Health-Care-Payment-Learning-and-Action-Network/. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Morse S. Covered California will exclude hospitals with high rates of C-sections. Healthcare Finance. 2016. http://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/covered-california-will-exclude-hospitals-high-rates-c-sections. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim. 2017. http://www.ihi.org/engage/initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- A pregnancy app for your EHR. 2017. https://www.dorsata.com/. Accessed December 4, 2017.

Read all parts of this series

PART 1 Value-based payment: What does it mean and how can ObGyns get out ahead

PART 2 What makes a “quality” quality measure?

PART 3 The role of patient-reported outcomes in women’s health

PART 4 It costs what?! How we can educate residents and students on how much things cost