User login

Combine these screening tools to detect bipolar depression

THE CASE

A 35-year-old police officer visited his family physician (FP) with complaints of low energy, trouble sleeping, a lack of enjoyment in life, and feelings of hopelessness that have persisted for several months. He was worried about the impact they were having on his marriage and work. He had not experienced suicidal thoughts. His Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) score was 18 (moderately severe depression). He had been seen intermittently for similar complaints and had tried several medications (fluoxetine, bupropion, and citalopram) without much effect. He was taking no medications now other than an over-the-counter multivitamin. He had one brother with anxiety and depression. He said his marriage counselor expressed concerns that he might have bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder.

How would you proceed with this patient?

The prevalence of a spectrum of bipolarity in the community has been shown to be 6.4%.1 Depressive episodes predominate in bipolar disorder (BPD),2 with patients spending less time in manic or hypomanic states.3 Not surprisingly, then, depressive episodes are the most common presentation of BPD.

The depressive symptoms of BPD and unipolar depression, or major depressive disorder (MDD), are similar, making it difficult to distinguish between the disorders.3 As a result, BPD is often misdiagnosed as MDD.4,5 Zimmerman et al point out that “bipolar disorder is prone to being overlooked because its diagnosis is more often based on retrospective report rather than presenting symptoms of mania or hypomania assessment.”6

Accurately recognizing BPD is essential in selecting effective treatment. It’s estimated that approximately one-third of patients given antidepressants for major depression show no treatment response,7 possibly due in part to undiagnosed BPD being more prevalent than previously thought.4,8 Failure to distinguish between depressive episodes of BPD and MDD before prescribing medication introduces the risk of ineffective or suboptimal treatment. Inappropriate treatment can worsen or destabilize the course of bipolar illness by, for instance, inducing rapid cycling or, less commonly, manic symptoms.

Screen for BPD when depressive symptoms are present

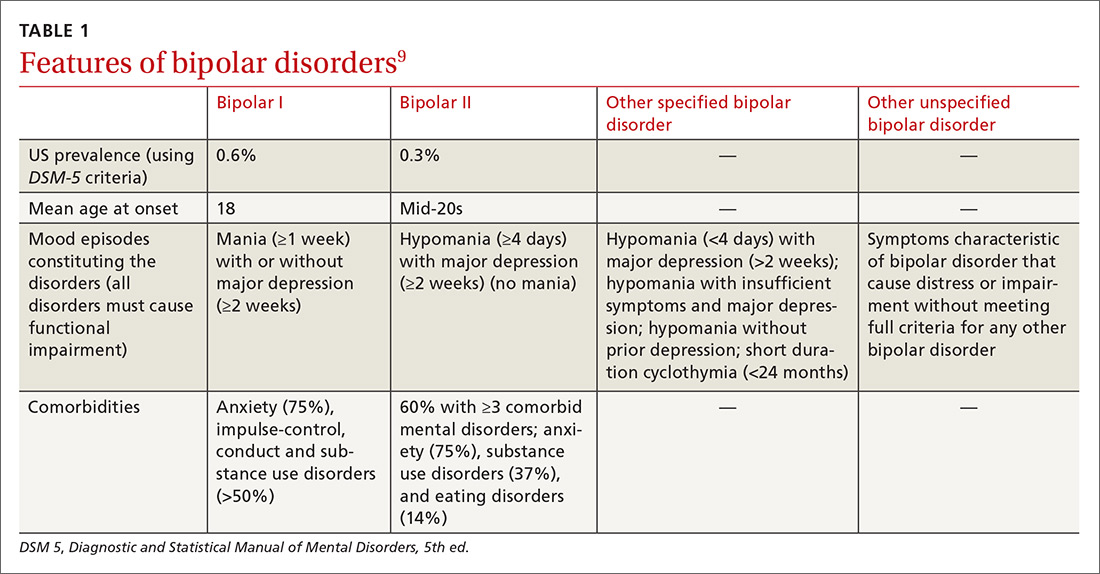

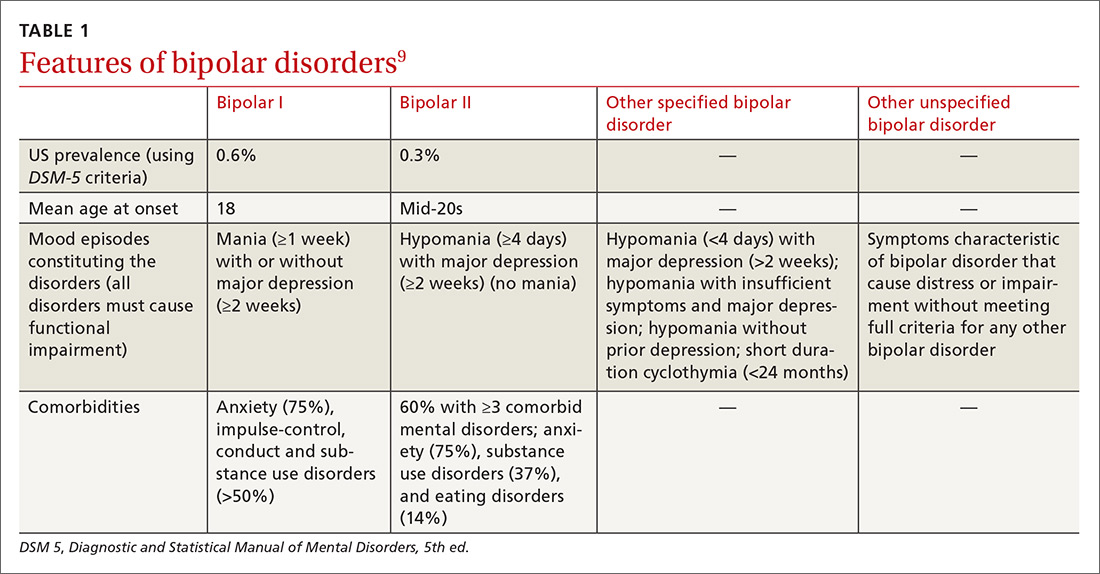

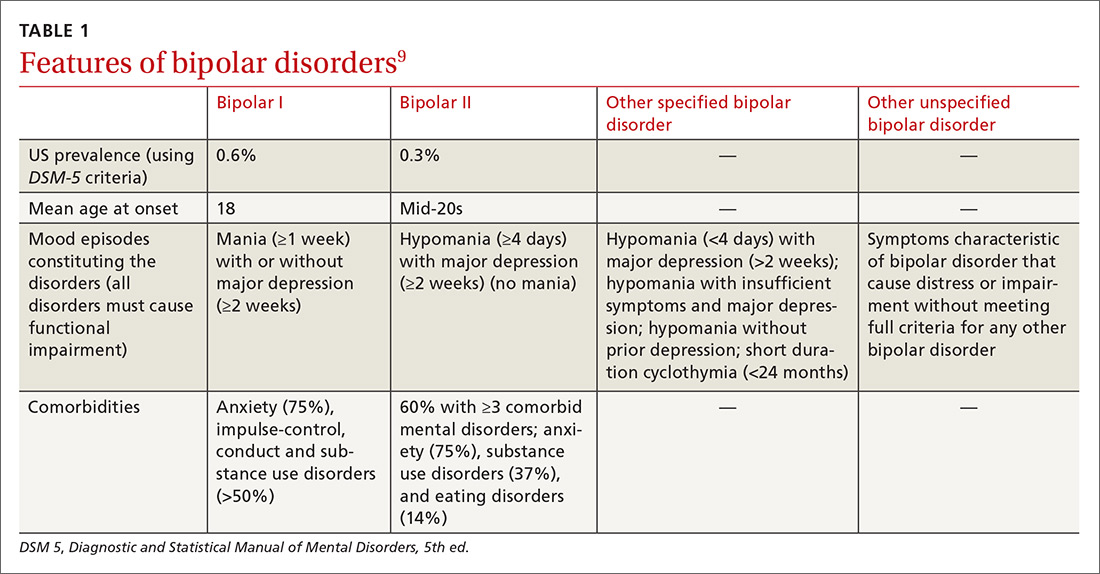

Identifying BPD in a patient with current or past depressive symptoms requires screening for manic, hypomanic, and mixed episodes (TABLE 19). Two brief, complementary screening tools — the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) and the 9-item PHQ9—are helpful in this assessment. Both questionnaires (TABLE 28,10-14) can be conveniently completed by the patient in the waiting room or with staff assistance before the physician encounter.

The MDQ screen is for past/lifetime or current manic/hypomanic symptoms (https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/MDQ.pdf). A positive screen requires answering “Yes” to at least 7 of the 13 items on question 1, answering “yes” on question 2, and answering “moderate problems” or “serious problems” on question 3.

Continue to: The PHQ9 screens for...

The PHQ9 screens for current depressive symptoms/episodes (https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/218).

The value of combining the MDQ and PHQ9. The PHQ9 screens for and assesses the severity of depressive episodes along with clinician assessment, but it cannot distinguish between depressive episodes of MDD or BPD. A brief instrument, such as MDQ, screens for current or past manic or hypomanic symptoms, which, when combined with the clinical interview and patient history, enables detection of BPD if present and avoids erroneously assigning depressive symptoms to MDD.

One cross-sectional study found that the combined MDQ and PHQ9 questionnaires have a higher sensitivity in detecting mood disorder than does routine assessment by general practitioners (0.8 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.71-0.81] vs 0.2 [95% CI, 0.12- 0.25]) and without loss of specificity (0.9 [95% CI, 0.86-0.96] vs 0.9 [95% CI, 0.88-0.97]).15 In this same study, using a structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) as the gold standard, researchers also found the screening tools to be more accurate (Cohen’s Kappa 0.7 [SE=0.05; 95% CI, 0.5-0.7]) than the general practitioner assessment (Cohen’s Kappa 0.2 [SE=0.07 (95% CI, 0.12-0.27]).15

Delve deeper with a patient interview

Use targeted questions and laboratory tests to rule out other possible causes of depressed mood, such as substance abuse or medical conditions (eg, hypothyroidism). Keep in mind that even when MDD or BPD is present, other medical disorders or substance abuse could be coexistent. Also ask about a personal or family psychiatric history and assess for suicidality. If family members are available, they may be able to help in identifying the patient’s age when symptoms first appeared or in adding information about the affective episode or behavior that the patient may not recollect.

Beyond a history of manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes, other symptoms and features may assist in distinguishing between bipolar and unipolar depression or in helping the clinician identify depressed patients who may be at higher risk for, or have, BPD. One meta-analysis of 3 multicenter clinical trials assessed sociodemographic factors and clinical features of BPD compared with unipolar depression. The average age of onset of mood symptoms in individuals with BPD was significantly younger (21.2 years) than that of patients with MDD (29.7 years).16 Another study found that patients with either bipolar I or bipolar II similarly experienced their first mood disorder episode 10 years earlier than those with MDD.17

Continue to: BPD is often associated with...

BPD is often associated with more frequent depressive episodes and a higher number of depressive symptoms per episode than is MDD, as well as more frequent family psychiatric histories (especially of mood disorders), anxiety disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders, and personality disorders.17 Other factors more closely associated with BPD than MDD include atypical features such as hypersomnia and psychomotor retardation, psychotic symptoms during the depressive episode, and more frequent recurrences of depressive episodes.18-22 Also, depressive episodes during the postpartum period indicate a higher risk of BPD than do episodes in women outside the postpartum period, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.66 (95% CI, 1.12-2.48).23 The risk is much greater when postpartum depressive episodes are associated with anxiety symptoms (HR=10.15; 95% CI, 7.13-14.46).23

Final thoughts

Increased awareness and screening for BPD in primary care—where most individuals with depressive symptoms are first encountered—should lead to more accurate diagnoses and decrease the years-long gaps between symptom onset and detection of BPD,4,5 thereby improving treatment and patient outcomes. Still, some cases of BPD may be difficult to recognize—particularly patients who present predominantly with depression with past irritability and other hypomanic symptoms (but not euphoria).

A positive MDQ screen should also prompt, if possible, a more detailed clinical interview by a mental health care professional, particularly if there is uncertainty about the diagnosis. Complex cases of BPD may require the expertise of a psychiatrist.

THE CASE

The patient’s FP referred him to a psychiatrist colleague, whose inquiry also revealed low mood, anhedonia, hopelessness, difficulty sleeping, low energy, poor appetite, guilt, poor concentration, and psychomotor retardation. The patient had experienced multiple depressive episodes over the past 20 years. Significant interpersonal conflicts frequently triggered his depressive episodes, which were accompanied by mood irritability, racing thoughts, distractibility, increased libido, excessive spending, increased energy, and engagement in risky behaviors.

The patient’s score on the MDQ administered by the psychiatrist was positive, with 7 points on question 1. He also had posttraumatic symptoms related to his police work, which were not the main reason for the visit. He had been divorced 3 times. In prior manic episodes, he had not displayed euphoria, grandiosity, psychotic symptoms, or anxiety, but rather irritability with other manic symptoms.

Continue to: Based on his MDQ results...

Based on his MDQ results, the clinical interview, and current episode with mixed features, the patient was given a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. The psychiatrist prescribed divalproex 500 mg at bedtime and scheduled a return visit with a plan for further laboratory monitoring and up-titration if needed. He was also encouraged to follow up with his FP.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nagy A. Youssef, MD, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, 997 St. Sebastian Way, Augusta, GA 30912; [email protected].

SUPPORT AND ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Dr. Youssef’s work on this paper was supported by the Office of Academic Affairs, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University. We thank Mark Yassa, BS, for his assistance in editing.

1. Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:123-131.

2. Yatham LN, Lecrubier Y, Fieve RR, et al. Quality of life in patients with bipolar I depression: data from 920 patients. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:379-385.

3. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530-537.

4. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999;52:135-144.

5. Cha B, Kim JH, Ha TH, et al. Polarity of the first episode and time to diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2009;6:96-101. Available at: http://psychiatryinvestigation.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.4306/pi.2009.6.2.96. Accessed June 25, 2018.

6. Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Chelminski I, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses in patients who screen positive on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: implications for using the scale as a case-finding instrument for bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:444-449.

7. Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:369-388.

8. Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:233-239.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013.

10. Poon Y, Chung KF, Tso KC, et al. The use of Mood Disorder Questionnaire, Hypomania Checklist-32 and clinical predictors for screening previously unrecognised bipolar disorder in a general psychiatric setting. Psychiatry Res. 2012;195:111-117.

11. Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, et al. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1596-1602.

12. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.

13. Miller CJ, Klugman J, Berv DA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for detecting bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;81:167-171.

14. Sasdelli A, Lia L, Luciano CC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder symptoms in depressed primary care attenders: comparison between Mood Disorder Questionnaire and Hypomania Checklist (HCL-32). Psychiatry J. 2013;2013:548349.

15. Vohringer PA, Jimenez MI, Igor MA, et al. Detecting mood disorder in resource-limited primary care settings: comparison of a self-administered screening tool to general practitioner assessment. J Med Screen. 2013;20:118-124.

16. Perlis RH, Brown E, Baker RW, et al. Clinical features of bipolar depression versus major depressive disorder in large multicenter trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:225-231.

17. Moreno C, Hasin DS, Arango C, et al. Depression in bipolar disorder versus major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:271-282.

18. Mitchell PB, Malhi GS. Bipolar depression: phenomenological overview and clinical characteristics. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:530-539.

19. Solomon DA, Leon AC, Maser JD, et al. Distinguishing bipolar major depression from unipolar major depression with the screening assessment of depression-polarity (SAD-P). J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:434-442.

20. Bowden CL. A different depression: clinical distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:117-125.

21. Goes FS, Sadler B, Toolan J, et al. Psychotic features in bipolar and unipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:901-906.

22. Buzuk G, Lojko D, Owecki M, et al. Depression with atypical features in various kinds of affective disorders. Psychiatr Pol. 2016;50:827-838.

23. Liu X, Agerbo E, Li J, et al. Depression and anxiety in the postpartum period and risk of bipolar disorder: a Danish Nationwide Register-Based Cohort Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:e469-e476.

THE CASE

A 35-year-old police officer visited his family physician (FP) with complaints of low energy, trouble sleeping, a lack of enjoyment in life, and feelings of hopelessness that have persisted for several months. He was worried about the impact they were having on his marriage and work. He had not experienced suicidal thoughts. His Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) score was 18 (moderately severe depression). He had been seen intermittently for similar complaints and had tried several medications (fluoxetine, bupropion, and citalopram) without much effect. He was taking no medications now other than an over-the-counter multivitamin. He had one brother with anxiety and depression. He said his marriage counselor expressed concerns that he might have bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder.

How would you proceed with this patient?

The prevalence of a spectrum of bipolarity in the community has been shown to be 6.4%.1 Depressive episodes predominate in bipolar disorder (BPD),2 with patients spending less time in manic or hypomanic states.3 Not surprisingly, then, depressive episodes are the most common presentation of BPD.

The depressive symptoms of BPD and unipolar depression, or major depressive disorder (MDD), are similar, making it difficult to distinguish between the disorders.3 As a result, BPD is often misdiagnosed as MDD.4,5 Zimmerman et al point out that “bipolar disorder is prone to being overlooked because its diagnosis is more often based on retrospective report rather than presenting symptoms of mania or hypomania assessment.”6

Accurately recognizing BPD is essential in selecting effective treatment. It’s estimated that approximately one-third of patients given antidepressants for major depression show no treatment response,7 possibly due in part to undiagnosed BPD being more prevalent than previously thought.4,8 Failure to distinguish between depressive episodes of BPD and MDD before prescribing medication introduces the risk of ineffective or suboptimal treatment. Inappropriate treatment can worsen or destabilize the course of bipolar illness by, for instance, inducing rapid cycling or, less commonly, manic symptoms.

Screen for BPD when depressive symptoms are present

Identifying BPD in a patient with current or past depressive symptoms requires screening for manic, hypomanic, and mixed episodes (TABLE 19). Two brief, complementary screening tools — the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) and the 9-item PHQ9—are helpful in this assessment. Both questionnaires (TABLE 28,10-14) can be conveniently completed by the patient in the waiting room or with staff assistance before the physician encounter.

The MDQ screen is for past/lifetime or current manic/hypomanic symptoms (https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/MDQ.pdf). A positive screen requires answering “Yes” to at least 7 of the 13 items on question 1, answering “yes” on question 2, and answering “moderate problems” or “serious problems” on question 3.

Continue to: The PHQ9 screens for...

The PHQ9 screens for current depressive symptoms/episodes (https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/218).

The value of combining the MDQ and PHQ9. The PHQ9 screens for and assesses the severity of depressive episodes along with clinician assessment, but it cannot distinguish between depressive episodes of MDD or BPD. A brief instrument, such as MDQ, screens for current or past manic or hypomanic symptoms, which, when combined with the clinical interview and patient history, enables detection of BPD if present and avoids erroneously assigning depressive symptoms to MDD.

One cross-sectional study found that the combined MDQ and PHQ9 questionnaires have a higher sensitivity in detecting mood disorder than does routine assessment by general practitioners (0.8 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.71-0.81] vs 0.2 [95% CI, 0.12- 0.25]) and without loss of specificity (0.9 [95% CI, 0.86-0.96] vs 0.9 [95% CI, 0.88-0.97]).15 In this same study, using a structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) as the gold standard, researchers also found the screening tools to be more accurate (Cohen’s Kappa 0.7 [SE=0.05; 95% CI, 0.5-0.7]) than the general practitioner assessment (Cohen’s Kappa 0.2 [SE=0.07 (95% CI, 0.12-0.27]).15

Delve deeper with a patient interview

Use targeted questions and laboratory tests to rule out other possible causes of depressed mood, such as substance abuse or medical conditions (eg, hypothyroidism). Keep in mind that even when MDD or BPD is present, other medical disorders or substance abuse could be coexistent. Also ask about a personal or family psychiatric history and assess for suicidality. If family members are available, they may be able to help in identifying the patient’s age when symptoms first appeared or in adding information about the affective episode or behavior that the patient may not recollect.

Beyond a history of manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes, other symptoms and features may assist in distinguishing between bipolar and unipolar depression or in helping the clinician identify depressed patients who may be at higher risk for, or have, BPD. One meta-analysis of 3 multicenter clinical trials assessed sociodemographic factors and clinical features of BPD compared with unipolar depression. The average age of onset of mood symptoms in individuals with BPD was significantly younger (21.2 years) than that of patients with MDD (29.7 years).16 Another study found that patients with either bipolar I or bipolar II similarly experienced their first mood disorder episode 10 years earlier than those with MDD.17

Continue to: BPD is often associated with...

BPD is often associated with more frequent depressive episodes and a higher number of depressive symptoms per episode than is MDD, as well as more frequent family psychiatric histories (especially of mood disorders), anxiety disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders, and personality disorders.17 Other factors more closely associated with BPD than MDD include atypical features such as hypersomnia and psychomotor retardation, psychotic symptoms during the depressive episode, and more frequent recurrences of depressive episodes.18-22 Also, depressive episodes during the postpartum period indicate a higher risk of BPD than do episodes in women outside the postpartum period, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.66 (95% CI, 1.12-2.48).23 The risk is much greater when postpartum depressive episodes are associated with anxiety symptoms (HR=10.15; 95% CI, 7.13-14.46).23

Final thoughts

Increased awareness and screening for BPD in primary care—where most individuals with depressive symptoms are first encountered—should lead to more accurate diagnoses and decrease the years-long gaps between symptom onset and detection of BPD,4,5 thereby improving treatment and patient outcomes. Still, some cases of BPD may be difficult to recognize—particularly patients who present predominantly with depression with past irritability and other hypomanic symptoms (but not euphoria).

A positive MDQ screen should also prompt, if possible, a more detailed clinical interview by a mental health care professional, particularly if there is uncertainty about the diagnosis. Complex cases of BPD may require the expertise of a psychiatrist.

THE CASE

The patient’s FP referred him to a psychiatrist colleague, whose inquiry also revealed low mood, anhedonia, hopelessness, difficulty sleeping, low energy, poor appetite, guilt, poor concentration, and psychomotor retardation. The patient had experienced multiple depressive episodes over the past 20 years. Significant interpersonal conflicts frequently triggered his depressive episodes, which were accompanied by mood irritability, racing thoughts, distractibility, increased libido, excessive spending, increased energy, and engagement in risky behaviors.

The patient’s score on the MDQ administered by the psychiatrist was positive, with 7 points on question 1. He also had posttraumatic symptoms related to his police work, which were not the main reason for the visit. He had been divorced 3 times. In prior manic episodes, he had not displayed euphoria, grandiosity, psychotic symptoms, or anxiety, but rather irritability with other manic symptoms.

Continue to: Based on his MDQ results...

Based on his MDQ results, the clinical interview, and current episode with mixed features, the patient was given a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. The psychiatrist prescribed divalproex 500 mg at bedtime and scheduled a return visit with a plan for further laboratory monitoring and up-titration if needed. He was also encouraged to follow up with his FP.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nagy A. Youssef, MD, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, 997 St. Sebastian Way, Augusta, GA 30912; [email protected].

SUPPORT AND ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Dr. Youssef’s work on this paper was supported by the Office of Academic Affairs, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University. We thank Mark Yassa, BS, for his assistance in editing.

THE CASE

A 35-year-old police officer visited his family physician (FP) with complaints of low energy, trouble sleeping, a lack of enjoyment in life, and feelings of hopelessness that have persisted for several months. He was worried about the impact they were having on his marriage and work. He had not experienced suicidal thoughts. His Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) score was 18 (moderately severe depression). He had been seen intermittently for similar complaints and had tried several medications (fluoxetine, bupropion, and citalopram) without much effect. He was taking no medications now other than an over-the-counter multivitamin. He had one brother with anxiety and depression. He said his marriage counselor expressed concerns that he might have bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder.

How would you proceed with this patient?

The prevalence of a spectrum of bipolarity in the community has been shown to be 6.4%.1 Depressive episodes predominate in bipolar disorder (BPD),2 with patients spending less time in manic or hypomanic states.3 Not surprisingly, then, depressive episodes are the most common presentation of BPD.

The depressive symptoms of BPD and unipolar depression, or major depressive disorder (MDD), are similar, making it difficult to distinguish between the disorders.3 As a result, BPD is often misdiagnosed as MDD.4,5 Zimmerman et al point out that “bipolar disorder is prone to being overlooked because its diagnosis is more often based on retrospective report rather than presenting symptoms of mania or hypomania assessment.”6

Accurately recognizing BPD is essential in selecting effective treatment. It’s estimated that approximately one-third of patients given antidepressants for major depression show no treatment response,7 possibly due in part to undiagnosed BPD being more prevalent than previously thought.4,8 Failure to distinguish between depressive episodes of BPD and MDD before prescribing medication introduces the risk of ineffective or suboptimal treatment. Inappropriate treatment can worsen or destabilize the course of bipolar illness by, for instance, inducing rapid cycling or, less commonly, manic symptoms.

Screen for BPD when depressive symptoms are present

Identifying BPD in a patient with current or past depressive symptoms requires screening for manic, hypomanic, and mixed episodes (TABLE 19). Two brief, complementary screening tools — the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) and the 9-item PHQ9—are helpful in this assessment. Both questionnaires (TABLE 28,10-14) can be conveniently completed by the patient in the waiting room or with staff assistance before the physician encounter.

The MDQ screen is for past/lifetime or current manic/hypomanic symptoms (https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/MDQ.pdf). A positive screen requires answering “Yes” to at least 7 of the 13 items on question 1, answering “yes” on question 2, and answering “moderate problems” or “serious problems” on question 3.

Continue to: The PHQ9 screens for...

The PHQ9 screens for current depressive symptoms/episodes (https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/218).

The value of combining the MDQ and PHQ9. The PHQ9 screens for and assesses the severity of depressive episodes along with clinician assessment, but it cannot distinguish between depressive episodes of MDD or BPD. A brief instrument, such as MDQ, screens for current or past manic or hypomanic symptoms, which, when combined with the clinical interview and patient history, enables detection of BPD if present and avoids erroneously assigning depressive symptoms to MDD.

One cross-sectional study found that the combined MDQ and PHQ9 questionnaires have a higher sensitivity in detecting mood disorder than does routine assessment by general practitioners (0.8 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.71-0.81] vs 0.2 [95% CI, 0.12- 0.25]) and without loss of specificity (0.9 [95% CI, 0.86-0.96] vs 0.9 [95% CI, 0.88-0.97]).15 In this same study, using a structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) as the gold standard, researchers also found the screening tools to be more accurate (Cohen’s Kappa 0.7 [SE=0.05; 95% CI, 0.5-0.7]) than the general practitioner assessment (Cohen’s Kappa 0.2 [SE=0.07 (95% CI, 0.12-0.27]).15

Delve deeper with a patient interview

Use targeted questions and laboratory tests to rule out other possible causes of depressed mood, such as substance abuse or medical conditions (eg, hypothyroidism). Keep in mind that even when MDD or BPD is present, other medical disorders or substance abuse could be coexistent. Also ask about a personal or family psychiatric history and assess for suicidality. If family members are available, they may be able to help in identifying the patient’s age when symptoms first appeared or in adding information about the affective episode or behavior that the patient may not recollect.

Beyond a history of manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes, other symptoms and features may assist in distinguishing between bipolar and unipolar depression or in helping the clinician identify depressed patients who may be at higher risk for, or have, BPD. One meta-analysis of 3 multicenter clinical trials assessed sociodemographic factors and clinical features of BPD compared with unipolar depression. The average age of onset of mood symptoms in individuals with BPD was significantly younger (21.2 years) than that of patients with MDD (29.7 years).16 Another study found that patients with either bipolar I or bipolar II similarly experienced their first mood disorder episode 10 years earlier than those with MDD.17

Continue to: BPD is often associated with...

BPD is often associated with more frequent depressive episodes and a higher number of depressive symptoms per episode than is MDD, as well as more frequent family psychiatric histories (especially of mood disorders), anxiety disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders, and personality disorders.17 Other factors more closely associated with BPD than MDD include atypical features such as hypersomnia and psychomotor retardation, psychotic symptoms during the depressive episode, and more frequent recurrences of depressive episodes.18-22 Also, depressive episodes during the postpartum period indicate a higher risk of BPD than do episodes in women outside the postpartum period, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.66 (95% CI, 1.12-2.48).23 The risk is much greater when postpartum depressive episodes are associated with anxiety symptoms (HR=10.15; 95% CI, 7.13-14.46).23

Final thoughts

Increased awareness and screening for BPD in primary care—where most individuals with depressive symptoms are first encountered—should lead to more accurate diagnoses and decrease the years-long gaps between symptom onset and detection of BPD,4,5 thereby improving treatment and patient outcomes. Still, some cases of BPD may be difficult to recognize—particularly patients who present predominantly with depression with past irritability and other hypomanic symptoms (but not euphoria).

A positive MDQ screen should also prompt, if possible, a more detailed clinical interview by a mental health care professional, particularly if there is uncertainty about the diagnosis. Complex cases of BPD may require the expertise of a psychiatrist.

THE CASE

The patient’s FP referred him to a psychiatrist colleague, whose inquiry also revealed low mood, anhedonia, hopelessness, difficulty sleeping, low energy, poor appetite, guilt, poor concentration, and psychomotor retardation. The patient had experienced multiple depressive episodes over the past 20 years. Significant interpersonal conflicts frequently triggered his depressive episodes, which were accompanied by mood irritability, racing thoughts, distractibility, increased libido, excessive spending, increased energy, and engagement in risky behaviors.

The patient’s score on the MDQ administered by the psychiatrist was positive, with 7 points on question 1. He also had posttraumatic symptoms related to his police work, which were not the main reason for the visit. He had been divorced 3 times. In prior manic episodes, he had not displayed euphoria, grandiosity, psychotic symptoms, or anxiety, but rather irritability with other manic symptoms.

Continue to: Based on his MDQ results...

Based on his MDQ results, the clinical interview, and current episode with mixed features, the patient was given a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. The psychiatrist prescribed divalproex 500 mg at bedtime and scheduled a return visit with a plan for further laboratory monitoring and up-titration if needed. He was also encouraged to follow up with his FP.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nagy A. Youssef, MD, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, 997 St. Sebastian Way, Augusta, GA 30912; [email protected].

SUPPORT AND ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Dr. Youssef’s work on this paper was supported by the Office of Academic Affairs, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University. We thank Mark Yassa, BS, for his assistance in editing.

1. Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:123-131.

2. Yatham LN, Lecrubier Y, Fieve RR, et al. Quality of life in patients with bipolar I depression: data from 920 patients. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:379-385.

3. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530-537.

4. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999;52:135-144.

5. Cha B, Kim JH, Ha TH, et al. Polarity of the first episode and time to diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2009;6:96-101. Available at: http://psychiatryinvestigation.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.4306/pi.2009.6.2.96. Accessed June 25, 2018.

6. Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Chelminski I, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses in patients who screen positive on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: implications for using the scale as a case-finding instrument for bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:444-449.

7. Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:369-388.

8. Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:233-239.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013.

10. Poon Y, Chung KF, Tso KC, et al. The use of Mood Disorder Questionnaire, Hypomania Checklist-32 and clinical predictors for screening previously unrecognised bipolar disorder in a general psychiatric setting. Psychiatry Res. 2012;195:111-117.

11. Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, et al. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1596-1602.

12. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.

13. Miller CJ, Klugman J, Berv DA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for detecting bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;81:167-171.

14. Sasdelli A, Lia L, Luciano CC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder symptoms in depressed primary care attenders: comparison between Mood Disorder Questionnaire and Hypomania Checklist (HCL-32). Psychiatry J. 2013;2013:548349.

15. Vohringer PA, Jimenez MI, Igor MA, et al. Detecting mood disorder in resource-limited primary care settings: comparison of a self-administered screening tool to general practitioner assessment. J Med Screen. 2013;20:118-124.

16. Perlis RH, Brown E, Baker RW, et al. Clinical features of bipolar depression versus major depressive disorder in large multicenter trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:225-231.

17. Moreno C, Hasin DS, Arango C, et al. Depression in bipolar disorder versus major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:271-282.

18. Mitchell PB, Malhi GS. Bipolar depression: phenomenological overview and clinical characteristics. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:530-539.

19. Solomon DA, Leon AC, Maser JD, et al. Distinguishing bipolar major depression from unipolar major depression with the screening assessment of depression-polarity (SAD-P). J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:434-442.

20. Bowden CL. A different depression: clinical distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:117-125.

21. Goes FS, Sadler B, Toolan J, et al. Psychotic features in bipolar and unipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:901-906.

22. Buzuk G, Lojko D, Owecki M, et al. Depression with atypical features in various kinds of affective disorders. Psychiatr Pol. 2016;50:827-838.

23. Liu X, Agerbo E, Li J, et al. Depression and anxiety in the postpartum period and risk of bipolar disorder: a Danish Nationwide Register-Based Cohort Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:e469-e476.

1. Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:123-131.

2. Yatham LN, Lecrubier Y, Fieve RR, et al. Quality of life in patients with bipolar I depression: data from 920 patients. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:379-385.

3. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530-537.

4. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999;52:135-144.

5. Cha B, Kim JH, Ha TH, et al. Polarity of the first episode and time to diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2009;6:96-101. Available at: http://psychiatryinvestigation.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.4306/pi.2009.6.2.96. Accessed June 25, 2018.

6. Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Chelminski I, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses in patients who screen positive on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: implications for using the scale as a case-finding instrument for bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:444-449.

7. Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:369-388.

8. Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:233-239.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013.

10. Poon Y, Chung KF, Tso KC, et al. The use of Mood Disorder Questionnaire, Hypomania Checklist-32 and clinical predictors for screening previously unrecognised bipolar disorder in a general psychiatric setting. Psychiatry Res. 2012;195:111-117.

11. Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, et al. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1596-1602.

12. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.

13. Miller CJ, Klugman J, Berv DA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for detecting bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;81:167-171.

14. Sasdelli A, Lia L, Luciano CC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder symptoms in depressed primary care attenders: comparison between Mood Disorder Questionnaire and Hypomania Checklist (HCL-32). Psychiatry J. 2013;2013:548349.

15. Vohringer PA, Jimenez MI, Igor MA, et al. Detecting mood disorder in resource-limited primary care settings: comparison of a self-administered screening tool to general practitioner assessment. J Med Screen. 2013;20:118-124.

16. Perlis RH, Brown E, Baker RW, et al. Clinical features of bipolar depression versus major depressive disorder in large multicenter trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:225-231.

17. Moreno C, Hasin DS, Arango C, et al. Depression in bipolar disorder versus major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:271-282.

18. Mitchell PB, Malhi GS. Bipolar depression: phenomenological overview and clinical characteristics. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:530-539.

19. Solomon DA, Leon AC, Maser JD, et al. Distinguishing bipolar major depression from unipolar major depression with the screening assessment of depression-polarity (SAD-P). J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:434-442.

20. Bowden CL. A different depression: clinical distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:117-125.

21. Goes FS, Sadler B, Toolan J, et al. Psychotic features in bipolar and unipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:901-906.

22. Buzuk G, Lojko D, Owecki M, et al. Depression with atypical features in various kinds of affective disorders. Psychiatr Pol. 2016;50:827-838.

23. Liu X, Agerbo E, Li J, et al. Depression and anxiety in the postpartum period and risk of bipolar disorder: a Danish Nationwide Register-Based Cohort Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:e469-e476.