User login

Exploring multidisciplinary treatments in the traumatizing aspects of chronic abdominal pain

Introduction

Abdominal pain is a complex phenomenon that involves unpleasant sensory and emotional experiences caused by actual or potential visceral tissue damage. As pain becomes chronic, there is a functional reorganization of the brain involved in emotional and cognitive processing leading to amplification of pain perception and associated pain suffering.1,2 With the rising recognition of the complexity of pain management in the 1960s, the treatment of pain became a recognized field of study, leading to the formation of interdisciplinary teams to treat pain. However, although efficacious, this model lacked adequate reimbursement structures and eventually subsided as opioids (which at the time were widely believed to be nonaddictive) become more prevalent.3 Not only is there a lack of empirical evidence for opioids in the management of chronic abdominal pain, there is a growing list of adverse consequences of prolonged opioid use for both the brain and gastrointestinal tract.4

Recently, there has been more clinical focus on behavioral interventions that can modulate gut pain signals and associated behaviors by reversing maladaptive emotional and cognitive brain processes.5 One such psychological process that has received little attention is the traumatizing nature of chronic abdominal pain. Chronic pain, particularly when it feels uncontrollable to patients, activates the brain’s fear circuitry and drives hyperarousal, emotional numbing, and consolidation of painful somatic memories, which become habitual and further amplify negative visceral signals.6,7 These processes are identical to the symptom manifestations of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as intrusiveness, avoidance, negative mood and cognitions, and hyperarousal from life events. In fact, individuals with a history of other traumatizing exposures have an even higher risk of developing chronic pain disorders.8 This review has two objectives: to provide a theoretical framework for understanding chronic pain as a traumatizing experience with posttraumatic manifestations and to discuss behavioral interventions and adjunctive nonopioid pharmacotherapy embedded in multidisciplinary care models essential to reversing this negative brain-gut cycle and reducing pain-related suffering.

Trauma and chronic abdominal pain

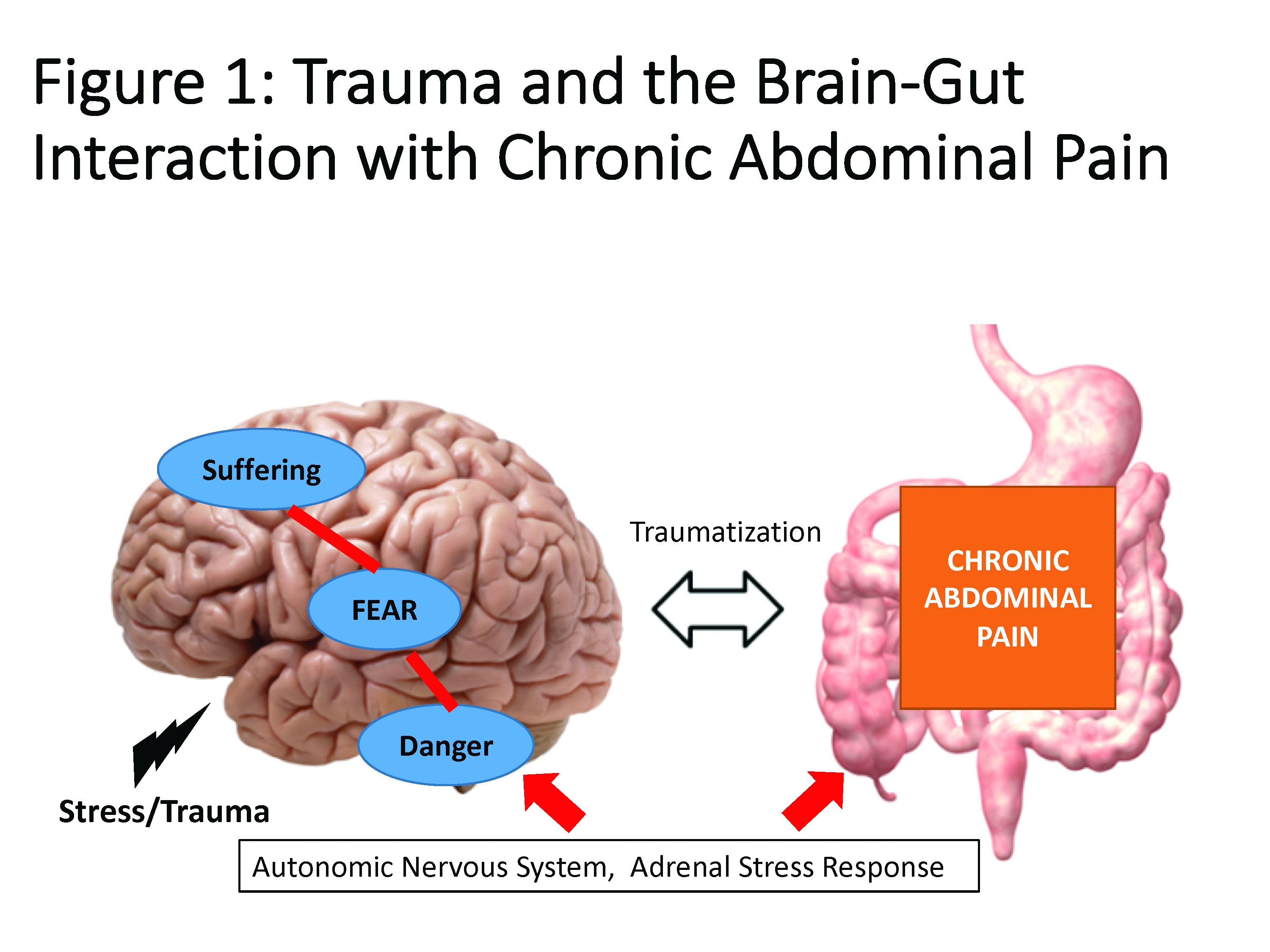

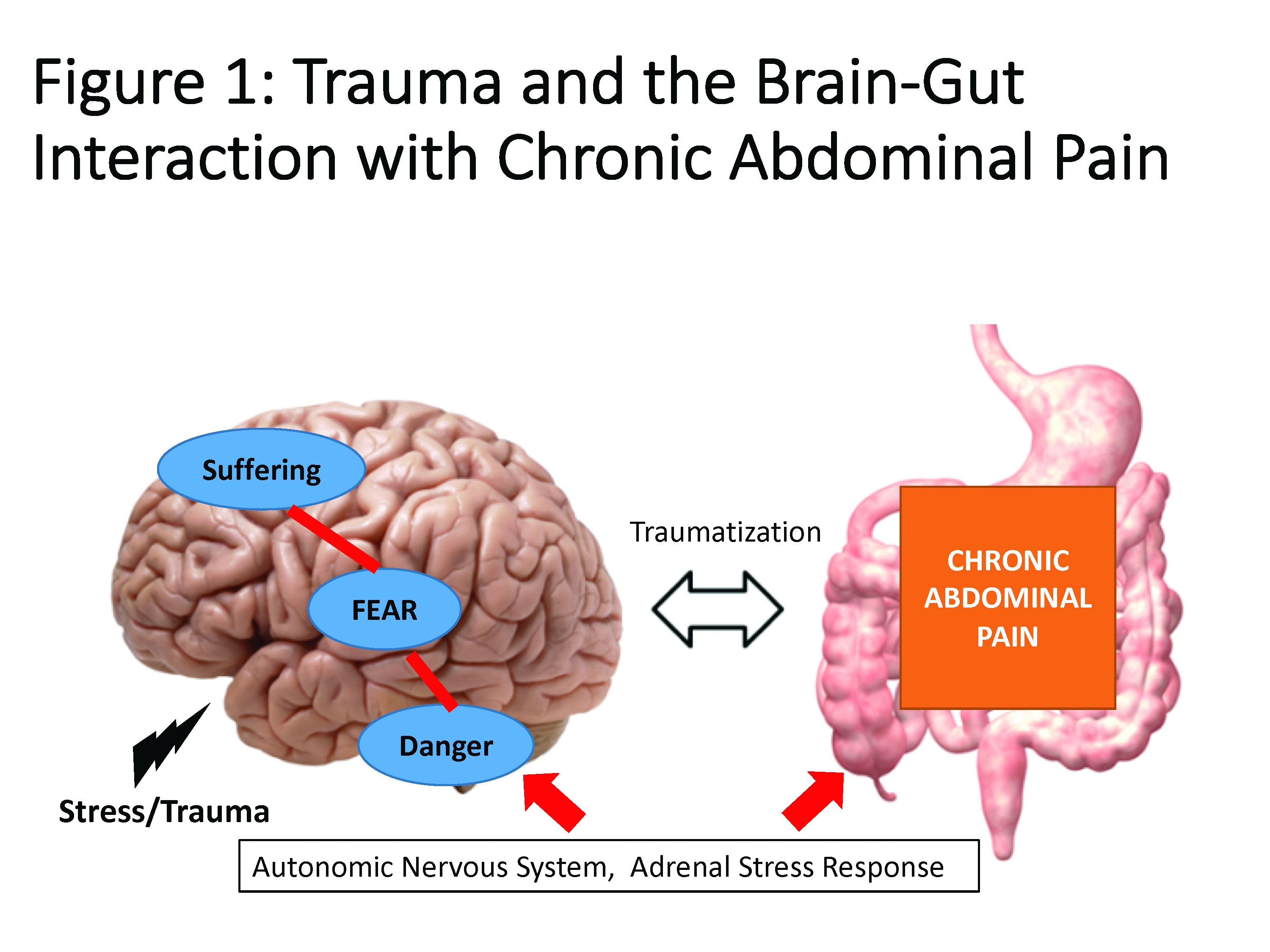

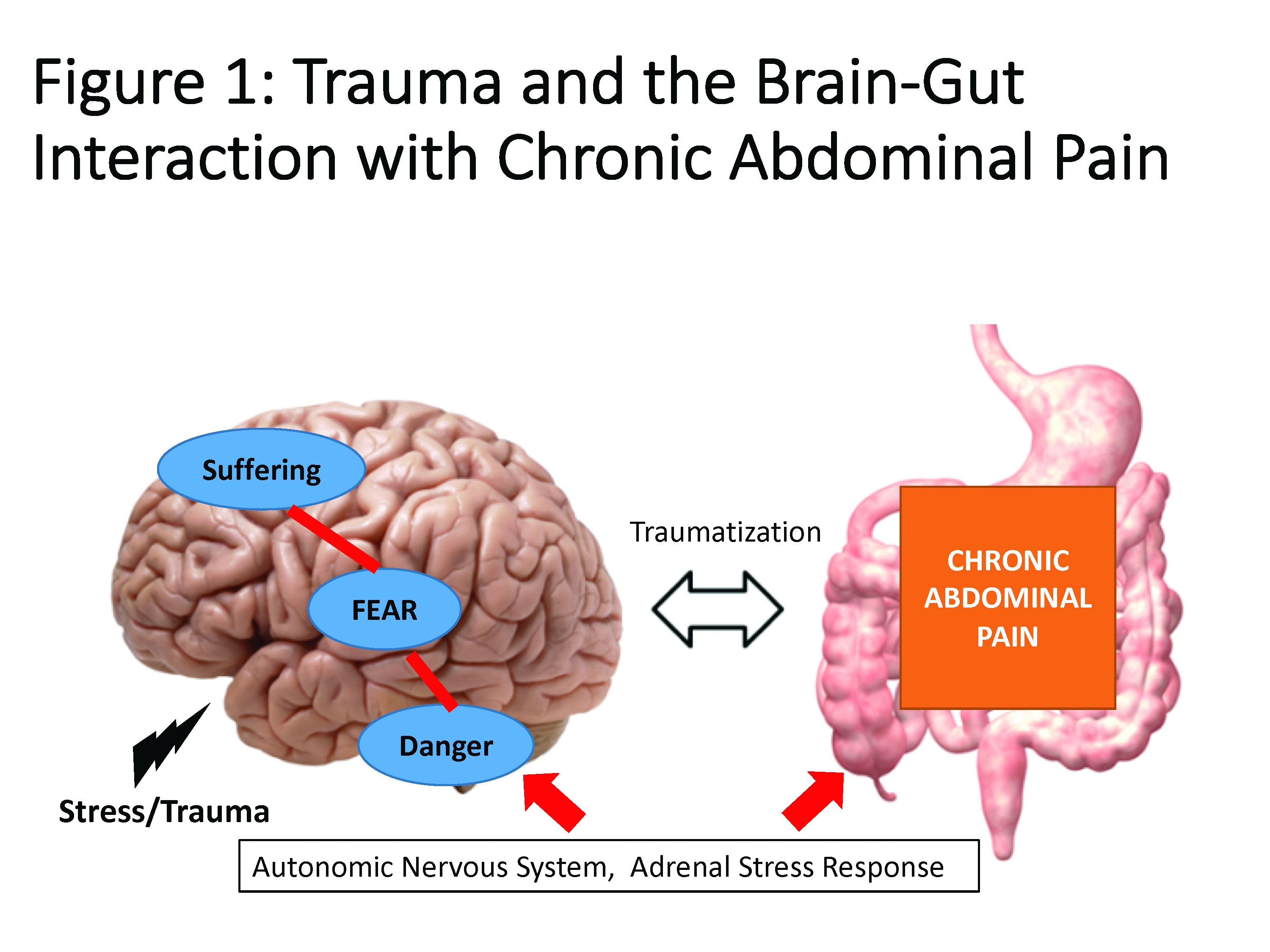

Trauma is defined as an individual’s response to a threat to safety. Traumatized patients or those with PTSD are at higher risk for chronic abdominal pain.9 Given the strong neurobiological connection between the brain and gut that has been phylogenetically preserved, emotional (e.g., fear, terror) or physical (e.g., pain) signals represent danger, and with chronicity, there can be a kindling-related consolidation of these maladaptive neurobiological pathways leading to suffering (e.g., hopelessness, sense of failure) and disability (Figure 1).

The interrelationship between chronic pain and trauma is multifaceted and is further complicated by the traumatizing nature of chronic pain itself, when pain is interpreted as a signal that the body is sick or even dangerously ill. Patients with chronic abdominal pain may seek multiple medical opinions and often undergo extensive, unnecessary, and sometimes harmful interventions to find the cause of their pain, with fear of disability and even death driving this search for answers.

The degree to which an individual with long-lasting pain interprets their discomfort as a risk to their well-being is related to the degree of trauma they experience because of their pain.10 Indeed, many of the negative symptoms associated with posttraumatic stress are also found in those with chronic abdominal pain. Trauma impacts the fear circuitry centers of the brain, leading to altered activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the amygdala, as well as chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system and stress-released hormones, all of which are potential pathways that dysregulate the brain-gut relationship.11-13 Worries for safety, which are reactivated by physiological cues (e.g., GI symptoms, pain), as well as avoidance of potential triggers of GI symptoms (e.g., food, exercise, medications, and situations such as travel or scheduled events, and fear of being trapped without bathroom access), are common. Traumatized individuals can experience a foreshortened sense of the future, which may lead to decreased investment in long-term determinants of health (e.g., balanced diet, exercise, social support) and have higher rates of functional impairment and higher health care utilization.14 Negative mood, including irritability, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and impaired concentration are common in those with trauma and chronic pain and can be accompanied by internalized blame (e.g., depression, substance abuse, suicidality) or externalized blame (e.g., negative relationships with health care providers, rejection from their support or faith system). These can be worsened by an impaired sense of trust, which impacts the patient-provider relationship and other sources of social support leading to lack of behavioral activation, anhedonia, and isolation.

Another commonality is hypervigilance, as those with chronic abdominal pain are often hyperaware of physical symptoms and always “on alert” for a signal indicative of a pain flare. Anxiety and depression frequently co-occur in populations with trauma and chronic pain; these diagnoses are associated with higher rates of catastrophizing and learned helplessness, which may be exacerbated by lack of a “cure” for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) and chronic pain.15 These factors could potentially lead to lack of engagement with treatment or, alternatively, risky or destructive attempts to cure pain including dangerous complementary alternative treatments or substance abuse to numb sensations. Another feature of trauma in chronic pain is the sense of dissociation from and lack of control over the body, sometimes induced by negative medical experiences (e.g., unwanted physical examinations, medication side effects, traumatic procedures, or hospitalizations).16,17

The importance of treating trauma in the management of chronic pain

Behavioral treatment is increasingly being recognized as an essential component in the management of any chronic pain syndrome.18 The most studied psychosocial interventions for chronic abdominal pain are cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and gut-focused hypnosis. CBT is usually a problem-focused, short-term intervention that can be delivered individually in the office, via group therapy, or through virtual platforms. CBT is most effective when cognitive distortions and ineffective behaviors create emotional distress, and the therapy targets patient’s stress reactivity, visceral anxiety, catastrophizing, and inflexible coping styles.5 Gut-focused hypnosis is the second most–studied behavioral treatment for chronic abdominal pain and utilizes the trance state to make positive suggestions leading to broad and lasting physiological and psychological improvement.19 In addition to pain management, both CBT and hypnosis are efficacious treatments for PTSD.20,21

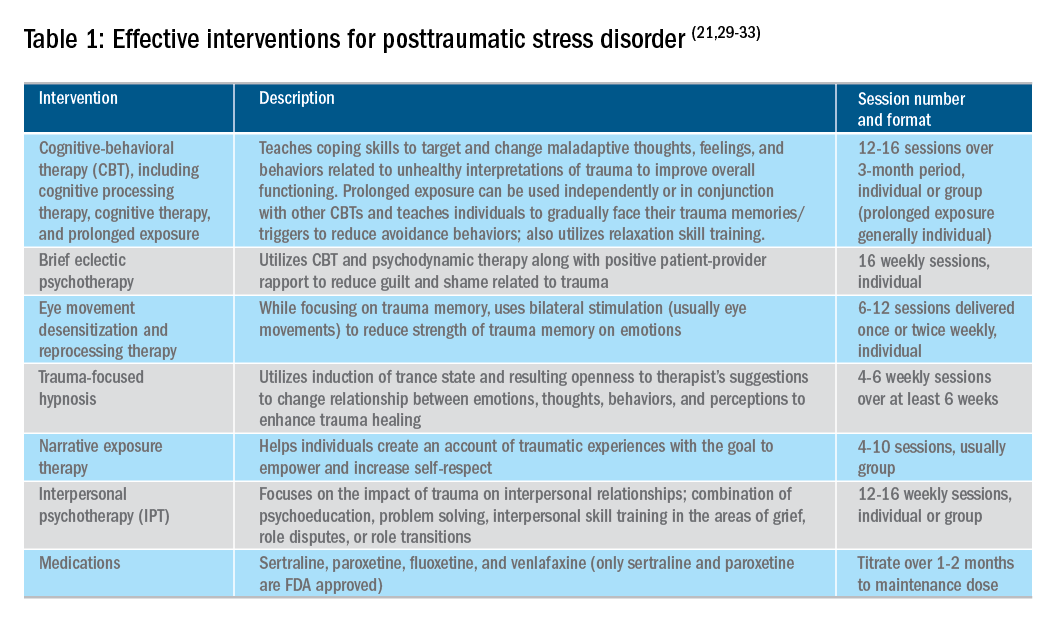

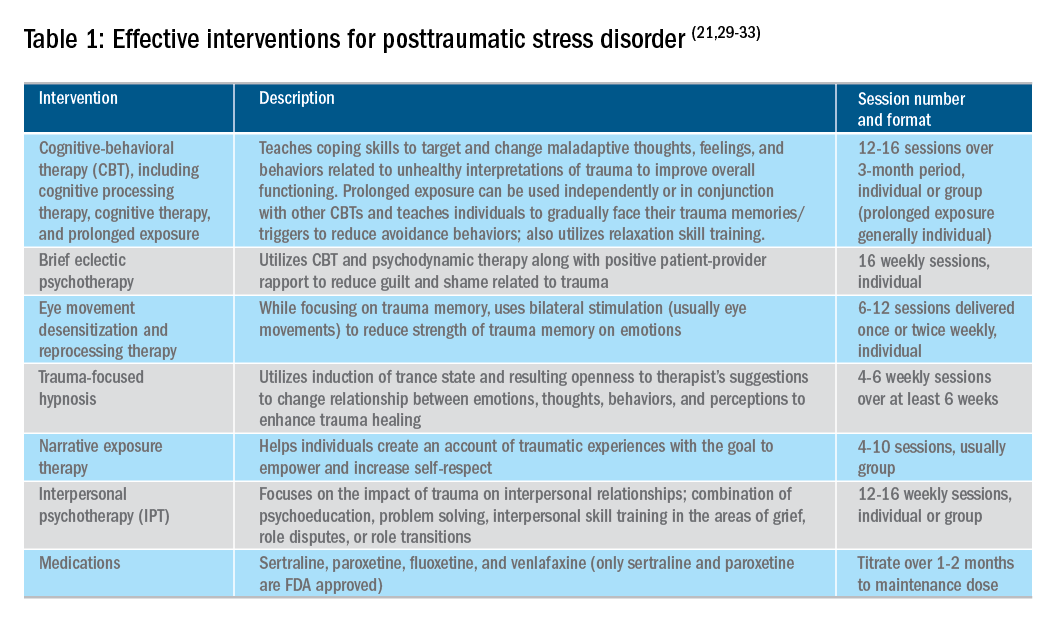

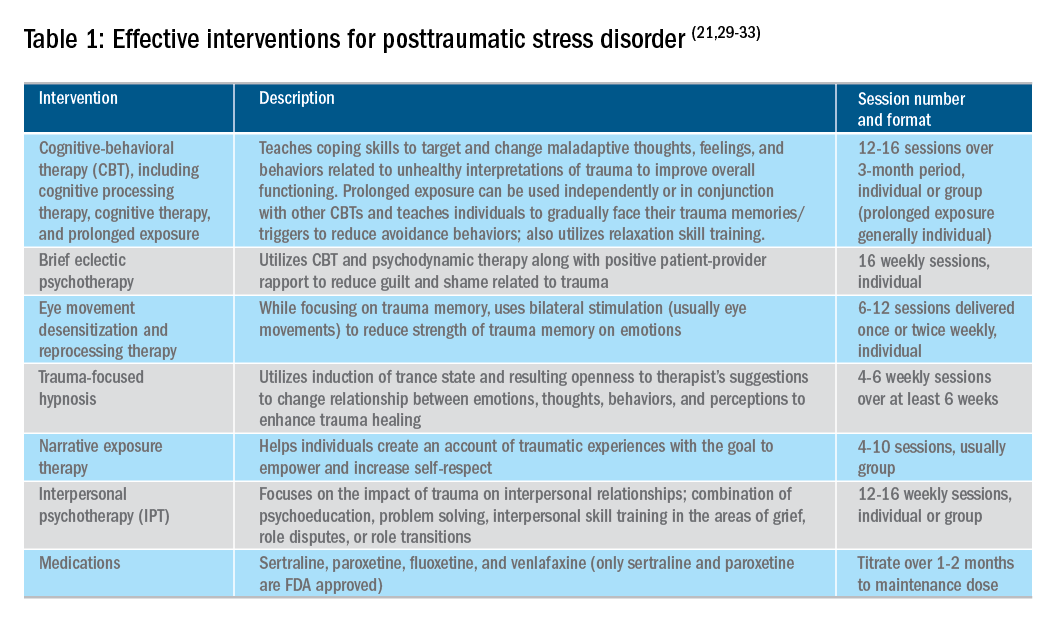

Utilizing a multidisciplinary medical team including integrated behavioral experts, such as in a patient-centered medical home, is considered the standard of care for treatment of chronic pain. The patient-provider relationship is essential, as is consistent follow-up to ensure effective symptom management and improvements in quality of life. Additionally, patient education, including a positive (i.e., clear) diagnosis and information on the brain-gut relationship, is associated with symptom improvement. In our subspecialty medical home for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), we found that, in our patients who were on opioids for their chronic pain, engagement with our embedded behavioral and pain specialists resulted in significant reduction in opioid use and depression as well as improved self-reported quality of life.22 Gastroenterologists and advanced-practice providers operating without embedded behavioral therapists can consider referring patients to behavioral treatment (e.g., licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, marriage and family therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists; the latter often specialize in medication management and may not offer behavioral therapy) for trauma if patients have undergone a traumatic event (e.g., exposure to any potentially life-threatening event, serious injury, or violence) at any point in their lifetime and are experiencing intrusive symptoms (e.g., memories, dreams, or flashbacks to trauma), avoidance of trauma reminders, and negative mood or hyperarousal related to traumatic events (Table 1).23

With the traumatization component of chronic abdominal pain, which can further drive maladaptive coping cycles, incorporation of trauma-informed treatment into gastroenterology clinics is an avenue toward more effective treatment. The core principles of trauma-informed care include safety, choice, collaboration, trustworthiness, and empowerment,24 and are easily aligned with patient-centered models of care such as the interdisciplinary medical home model. Incorporation of screening techniques, interdisciplinary training of clinicians, and use of behavioral providers with experience in evidenced-based treatments of trauma enhance a clinic’s ability to effectively identify and treat individuals who have trauma because of their abdominal pain.25 Additionally, the most common behavioral interventions for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are also efficacious in the treatment of trauma. CBT is a well-validated treatment for PTSD that utilizes exposure therapy to help individuals restructure negative beliefs shaped by their negative experience and develop relaxation skills. Hypnosis is also validated in the treatment of trauma, with the possible mechanism of action being the replacement of the negative or dissociated traumatic trance with a healthy, adaptive trance facilitated by the hypnotherapist.21

Adjunctive nonopioid medications for chronic abdominal pain

While there are few randomized controlled trials establishing efficacy of pharmacotherapy for sustained improvement of abdominal pain or related suffering, several small trials and consensus clinical expert opinion suggest partial improvement in these domains.26,27 Central neuromodulators that can attenuate chronic visceral pain include antidepressants, antipsychotics, and other central nervous system–targeted medications.26 Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine) are often first-line treatment for FGIDs.28 Serotonin noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (e.g., duloxetine, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, milnacipran) are also effective in pain management. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) can be used, especially when comorbid depression, anxiety, and phobic disorders are present. Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., mirtazapine, mianserin, trazodone) are effective treatments for early satiety, nausea/vomiting, insomnia, and low weight. Augmenting agents are utilized when single agents do not provide maximum benefit, including quetiapine (disturbed sleep), bupropion (fatigue), aripiprazole, buspirone, and tandospirone (dyspeptic features and anxiety). Delta ligands including gabapentin and pregabalin are helpful for abdominal wall pain or fibromyalgia. Ketamine is a newer but promising pathway for treatment of pain and depression and is increasingly being utilized in outpatient settings. Additionally, partial opioid-receptor agonists including methadone and suboxone have been reported to decrease pain in addition to their efficacy in addiction recovery. Medical marijuana is another area of growing interest, and while research has yet to show a clear effect in pain management, it does appear helpful in nausea and appetite stimulation. Obtaining a therapeutic response is the first treatment goal, after which a patient should be monitored in at least 6-month intervals to ensure sustained benefits and tolerability, and if these are not met, enhancement of treatment or a slow taper is indicated. As in all treatments, a positive patient-provider relationship predicts improved treatment adherence and outcomes.26 However, while these pharmacological interventions can reduce symptom severity, there is little evidence that they reduce traumatization without adjunctive psychotherapy.29

Summary

Both behavioral and pharmacological treatment options are available for chronic abdominal pain and most useful if traumatic manifestations are assessed and included as treatment targets. A multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of chronic abdominal pain with increased screening and treatment of trauma is a promising pathway to improved care and management for patients with chronic pain. If trauma is left untreated, the benefits of otherwise effective treatments are likely to be significantly limited.

References

1. Apkarian AV et al. Prog Neurobiol. 2009 Feb;87(2):81-97.

2. Gallagher RM et al. Pain Med. 2011 Jan;12(1):1-2.

3. Collier R et al. CMAJ. 2018 Jan 8;190(1):E26-7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-5523.

4. Szigethy E et al. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2018;15:168-80.

5. Ballou S et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017 Jan;8(1):e214.

6. Egloff N et al. J Pain Res. 2013 Nov 5;6:765-70.

7. Fashler S et al. J Pain Res. 2016 Aug 10;9:551-61.

8. McKernan LC et al. Clin J Pain. 2019 May;35(5):385-93.

9. Ju T et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018 Dec 19. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001153.

10. Fishbain DA et al. Pain Med. 2017 Apr 1;18(4):711-35.

11. Martin CR et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;6(2):133-48.

12. Osadchiy V et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jan;17(2):322-32.

13. Brzozowski B et al. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016 Nov;14(8):892-900.

14. Outclat SD et al. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1872-9.

15. Asmundson GJ et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;Dec;47(10):930-7.

16. Taft TH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar 7. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz032.

17. Duckworth MP et al. International Journal of Rehabilitation and Health, 2000 Apr;5(2):129-39.

18. Scascighini L et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 May;47(5):670-8.

19. Palsson O et al. European Gastroenterology & Hepatology Review. 2010;6(1):42-6.

20. Watkins LE et al. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2018;12:1-9.

21. O’Toole SK et al. J Trauma Stress. 2016 Feb;29(1):97-100.

22. Goldblum Y et al. Digestive Disease Week. San Diego. 2019. Abstract in press.

23. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (of Mental Disorders), Fifth Edition. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

24. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2018. Trauma-informed approach and trauma-specific interventions. Retrieved from samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions.

25. Click BH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(5):681-94.

26. Drossman DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1140-71.

27. Thorkelson G et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Jun 1;22(6):1509-22.

28. Törnblom H et al. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2018;20(12):58.

29. Watkins LE et al. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:258.

30. American Psychiatric Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults. 2017.

31. Bisson JI et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Dec 13;(12):CD003388.

32. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DOD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. 2017.

33. Karatzias T et al. Psychol Med. 2019 Mar 12:1-15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719000436. Advance online publication.

Emily Weaver, LCSW, is a UPMC Total Care–IBD program senior social worker, Eva Szigethy, MD, PhD, is professor of psychiatry and medicine, codirector, IBD Total Care Medical Home, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, departments of medicine and psychiatry.

Introduction

Abdominal pain is a complex phenomenon that involves unpleasant sensory and emotional experiences caused by actual or potential visceral tissue damage. As pain becomes chronic, there is a functional reorganization of the brain involved in emotional and cognitive processing leading to amplification of pain perception and associated pain suffering.1,2 With the rising recognition of the complexity of pain management in the 1960s, the treatment of pain became a recognized field of study, leading to the formation of interdisciplinary teams to treat pain. However, although efficacious, this model lacked adequate reimbursement structures and eventually subsided as opioids (which at the time were widely believed to be nonaddictive) become more prevalent.3 Not only is there a lack of empirical evidence for opioids in the management of chronic abdominal pain, there is a growing list of adverse consequences of prolonged opioid use for both the brain and gastrointestinal tract.4

Recently, there has been more clinical focus on behavioral interventions that can modulate gut pain signals and associated behaviors by reversing maladaptive emotional and cognitive brain processes.5 One such psychological process that has received little attention is the traumatizing nature of chronic abdominal pain. Chronic pain, particularly when it feels uncontrollable to patients, activates the brain’s fear circuitry and drives hyperarousal, emotional numbing, and consolidation of painful somatic memories, which become habitual and further amplify negative visceral signals.6,7 These processes are identical to the symptom manifestations of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as intrusiveness, avoidance, negative mood and cognitions, and hyperarousal from life events. In fact, individuals with a history of other traumatizing exposures have an even higher risk of developing chronic pain disorders.8 This review has two objectives: to provide a theoretical framework for understanding chronic pain as a traumatizing experience with posttraumatic manifestations and to discuss behavioral interventions and adjunctive nonopioid pharmacotherapy embedded in multidisciplinary care models essential to reversing this negative brain-gut cycle and reducing pain-related suffering.

Trauma and chronic abdominal pain

Trauma is defined as an individual’s response to a threat to safety. Traumatized patients or those with PTSD are at higher risk for chronic abdominal pain.9 Given the strong neurobiological connection between the brain and gut that has been phylogenetically preserved, emotional (e.g., fear, terror) or physical (e.g., pain) signals represent danger, and with chronicity, there can be a kindling-related consolidation of these maladaptive neurobiological pathways leading to suffering (e.g., hopelessness, sense of failure) and disability (Figure 1).

The interrelationship between chronic pain and trauma is multifaceted and is further complicated by the traumatizing nature of chronic pain itself, when pain is interpreted as a signal that the body is sick or even dangerously ill. Patients with chronic abdominal pain may seek multiple medical opinions and often undergo extensive, unnecessary, and sometimes harmful interventions to find the cause of their pain, with fear of disability and even death driving this search for answers.

The degree to which an individual with long-lasting pain interprets their discomfort as a risk to their well-being is related to the degree of trauma they experience because of their pain.10 Indeed, many of the negative symptoms associated with posttraumatic stress are also found in those with chronic abdominal pain. Trauma impacts the fear circuitry centers of the brain, leading to altered activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the amygdala, as well as chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system and stress-released hormones, all of which are potential pathways that dysregulate the brain-gut relationship.11-13 Worries for safety, which are reactivated by physiological cues (e.g., GI symptoms, pain), as well as avoidance of potential triggers of GI symptoms (e.g., food, exercise, medications, and situations such as travel or scheduled events, and fear of being trapped without bathroom access), are common. Traumatized individuals can experience a foreshortened sense of the future, which may lead to decreased investment in long-term determinants of health (e.g., balanced diet, exercise, social support) and have higher rates of functional impairment and higher health care utilization.14 Negative mood, including irritability, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and impaired concentration are common in those with trauma and chronic pain and can be accompanied by internalized blame (e.g., depression, substance abuse, suicidality) or externalized blame (e.g., negative relationships with health care providers, rejection from their support or faith system). These can be worsened by an impaired sense of trust, which impacts the patient-provider relationship and other sources of social support leading to lack of behavioral activation, anhedonia, and isolation.

Another commonality is hypervigilance, as those with chronic abdominal pain are often hyperaware of physical symptoms and always “on alert” for a signal indicative of a pain flare. Anxiety and depression frequently co-occur in populations with trauma and chronic pain; these diagnoses are associated with higher rates of catastrophizing and learned helplessness, which may be exacerbated by lack of a “cure” for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) and chronic pain.15 These factors could potentially lead to lack of engagement with treatment or, alternatively, risky or destructive attempts to cure pain including dangerous complementary alternative treatments or substance abuse to numb sensations. Another feature of trauma in chronic pain is the sense of dissociation from and lack of control over the body, sometimes induced by negative medical experiences (e.g., unwanted physical examinations, medication side effects, traumatic procedures, or hospitalizations).16,17

The importance of treating trauma in the management of chronic pain

Behavioral treatment is increasingly being recognized as an essential component in the management of any chronic pain syndrome.18 The most studied psychosocial interventions for chronic abdominal pain are cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and gut-focused hypnosis. CBT is usually a problem-focused, short-term intervention that can be delivered individually in the office, via group therapy, or through virtual platforms. CBT is most effective when cognitive distortions and ineffective behaviors create emotional distress, and the therapy targets patient’s stress reactivity, visceral anxiety, catastrophizing, and inflexible coping styles.5 Gut-focused hypnosis is the second most–studied behavioral treatment for chronic abdominal pain and utilizes the trance state to make positive suggestions leading to broad and lasting physiological and psychological improvement.19 In addition to pain management, both CBT and hypnosis are efficacious treatments for PTSD.20,21

Utilizing a multidisciplinary medical team including integrated behavioral experts, such as in a patient-centered medical home, is considered the standard of care for treatment of chronic pain. The patient-provider relationship is essential, as is consistent follow-up to ensure effective symptom management and improvements in quality of life. Additionally, patient education, including a positive (i.e., clear) diagnosis and information on the brain-gut relationship, is associated with symptom improvement. In our subspecialty medical home for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), we found that, in our patients who were on opioids for their chronic pain, engagement with our embedded behavioral and pain specialists resulted in significant reduction in opioid use and depression as well as improved self-reported quality of life.22 Gastroenterologists and advanced-practice providers operating without embedded behavioral therapists can consider referring patients to behavioral treatment (e.g., licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, marriage and family therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists; the latter often specialize in medication management and may not offer behavioral therapy) for trauma if patients have undergone a traumatic event (e.g., exposure to any potentially life-threatening event, serious injury, or violence) at any point in their lifetime and are experiencing intrusive symptoms (e.g., memories, dreams, or flashbacks to trauma), avoidance of trauma reminders, and negative mood or hyperarousal related to traumatic events (Table 1).23

With the traumatization component of chronic abdominal pain, which can further drive maladaptive coping cycles, incorporation of trauma-informed treatment into gastroenterology clinics is an avenue toward more effective treatment. The core principles of trauma-informed care include safety, choice, collaboration, trustworthiness, and empowerment,24 and are easily aligned with patient-centered models of care such as the interdisciplinary medical home model. Incorporation of screening techniques, interdisciplinary training of clinicians, and use of behavioral providers with experience in evidenced-based treatments of trauma enhance a clinic’s ability to effectively identify and treat individuals who have trauma because of their abdominal pain.25 Additionally, the most common behavioral interventions for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are also efficacious in the treatment of trauma. CBT is a well-validated treatment for PTSD that utilizes exposure therapy to help individuals restructure negative beliefs shaped by their negative experience and develop relaxation skills. Hypnosis is also validated in the treatment of trauma, with the possible mechanism of action being the replacement of the negative or dissociated traumatic trance with a healthy, adaptive trance facilitated by the hypnotherapist.21

Adjunctive nonopioid medications for chronic abdominal pain

While there are few randomized controlled trials establishing efficacy of pharmacotherapy for sustained improvement of abdominal pain or related suffering, several small trials and consensus clinical expert opinion suggest partial improvement in these domains.26,27 Central neuromodulators that can attenuate chronic visceral pain include antidepressants, antipsychotics, and other central nervous system–targeted medications.26 Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine) are often first-line treatment for FGIDs.28 Serotonin noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (e.g., duloxetine, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, milnacipran) are also effective in pain management. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) can be used, especially when comorbid depression, anxiety, and phobic disorders are present. Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., mirtazapine, mianserin, trazodone) are effective treatments for early satiety, nausea/vomiting, insomnia, and low weight. Augmenting agents are utilized when single agents do not provide maximum benefit, including quetiapine (disturbed sleep), bupropion (fatigue), aripiprazole, buspirone, and tandospirone (dyspeptic features and anxiety). Delta ligands including gabapentin and pregabalin are helpful for abdominal wall pain or fibromyalgia. Ketamine is a newer but promising pathway for treatment of pain and depression and is increasingly being utilized in outpatient settings. Additionally, partial opioid-receptor agonists including methadone and suboxone have been reported to decrease pain in addition to their efficacy in addiction recovery. Medical marijuana is another area of growing interest, and while research has yet to show a clear effect in pain management, it does appear helpful in nausea and appetite stimulation. Obtaining a therapeutic response is the first treatment goal, after which a patient should be monitored in at least 6-month intervals to ensure sustained benefits and tolerability, and if these are not met, enhancement of treatment or a slow taper is indicated. As in all treatments, a positive patient-provider relationship predicts improved treatment adherence and outcomes.26 However, while these pharmacological interventions can reduce symptom severity, there is little evidence that they reduce traumatization without adjunctive psychotherapy.29

Summary

Both behavioral and pharmacological treatment options are available for chronic abdominal pain and most useful if traumatic manifestations are assessed and included as treatment targets. A multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of chronic abdominal pain with increased screening and treatment of trauma is a promising pathway to improved care and management for patients with chronic pain. If trauma is left untreated, the benefits of otherwise effective treatments are likely to be significantly limited.

References

1. Apkarian AV et al. Prog Neurobiol. 2009 Feb;87(2):81-97.

2. Gallagher RM et al. Pain Med. 2011 Jan;12(1):1-2.

3. Collier R et al. CMAJ. 2018 Jan 8;190(1):E26-7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-5523.

4. Szigethy E et al. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2018;15:168-80.

5. Ballou S et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017 Jan;8(1):e214.

6. Egloff N et al. J Pain Res. 2013 Nov 5;6:765-70.

7. Fashler S et al. J Pain Res. 2016 Aug 10;9:551-61.

8. McKernan LC et al. Clin J Pain. 2019 May;35(5):385-93.

9. Ju T et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018 Dec 19. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001153.

10. Fishbain DA et al. Pain Med. 2017 Apr 1;18(4):711-35.

11. Martin CR et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;6(2):133-48.

12. Osadchiy V et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jan;17(2):322-32.

13. Brzozowski B et al. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016 Nov;14(8):892-900.

14. Outclat SD et al. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1872-9.

15. Asmundson GJ et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;Dec;47(10):930-7.

16. Taft TH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar 7. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz032.

17. Duckworth MP et al. International Journal of Rehabilitation and Health, 2000 Apr;5(2):129-39.

18. Scascighini L et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 May;47(5):670-8.

19. Palsson O et al. European Gastroenterology & Hepatology Review. 2010;6(1):42-6.

20. Watkins LE et al. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2018;12:1-9.

21. O’Toole SK et al. J Trauma Stress. 2016 Feb;29(1):97-100.

22. Goldblum Y et al. Digestive Disease Week. San Diego. 2019. Abstract in press.

23. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (of Mental Disorders), Fifth Edition. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

24. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2018. Trauma-informed approach and trauma-specific interventions. Retrieved from samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions.

25. Click BH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(5):681-94.

26. Drossman DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1140-71.

27. Thorkelson G et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Jun 1;22(6):1509-22.

28. Törnblom H et al. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2018;20(12):58.

29. Watkins LE et al. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:258.

30. American Psychiatric Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults. 2017.

31. Bisson JI et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Dec 13;(12):CD003388.

32. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DOD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. 2017.

33. Karatzias T et al. Psychol Med. 2019 Mar 12:1-15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719000436. Advance online publication.

Emily Weaver, LCSW, is a UPMC Total Care–IBD program senior social worker, Eva Szigethy, MD, PhD, is professor of psychiatry and medicine, codirector, IBD Total Care Medical Home, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, departments of medicine and psychiatry.

Introduction

Abdominal pain is a complex phenomenon that involves unpleasant sensory and emotional experiences caused by actual or potential visceral tissue damage. As pain becomes chronic, there is a functional reorganization of the brain involved in emotional and cognitive processing leading to amplification of pain perception and associated pain suffering.1,2 With the rising recognition of the complexity of pain management in the 1960s, the treatment of pain became a recognized field of study, leading to the formation of interdisciplinary teams to treat pain. However, although efficacious, this model lacked adequate reimbursement structures and eventually subsided as opioids (which at the time were widely believed to be nonaddictive) become more prevalent.3 Not only is there a lack of empirical evidence for opioids in the management of chronic abdominal pain, there is a growing list of adverse consequences of prolonged opioid use for both the brain and gastrointestinal tract.4

Recently, there has been more clinical focus on behavioral interventions that can modulate gut pain signals and associated behaviors by reversing maladaptive emotional and cognitive brain processes.5 One such psychological process that has received little attention is the traumatizing nature of chronic abdominal pain. Chronic pain, particularly when it feels uncontrollable to patients, activates the brain’s fear circuitry and drives hyperarousal, emotional numbing, and consolidation of painful somatic memories, which become habitual and further amplify negative visceral signals.6,7 These processes are identical to the symptom manifestations of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as intrusiveness, avoidance, negative mood and cognitions, and hyperarousal from life events. In fact, individuals with a history of other traumatizing exposures have an even higher risk of developing chronic pain disorders.8 This review has two objectives: to provide a theoretical framework for understanding chronic pain as a traumatizing experience with posttraumatic manifestations and to discuss behavioral interventions and adjunctive nonopioid pharmacotherapy embedded in multidisciplinary care models essential to reversing this negative brain-gut cycle and reducing pain-related suffering.

Trauma and chronic abdominal pain

Trauma is defined as an individual’s response to a threat to safety. Traumatized patients or those with PTSD are at higher risk for chronic abdominal pain.9 Given the strong neurobiological connection between the brain and gut that has been phylogenetically preserved, emotional (e.g., fear, terror) or physical (e.g., pain) signals represent danger, and with chronicity, there can be a kindling-related consolidation of these maladaptive neurobiological pathways leading to suffering (e.g., hopelessness, sense of failure) and disability (Figure 1).

The interrelationship between chronic pain and trauma is multifaceted and is further complicated by the traumatizing nature of chronic pain itself, when pain is interpreted as a signal that the body is sick or even dangerously ill. Patients with chronic abdominal pain may seek multiple medical opinions and often undergo extensive, unnecessary, and sometimes harmful interventions to find the cause of their pain, with fear of disability and even death driving this search for answers.

The degree to which an individual with long-lasting pain interprets their discomfort as a risk to their well-being is related to the degree of trauma they experience because of their pain.10 Indeed, many of the negative symptoms associated with posttraumatic stress are also found in those with chronic abdominal pain. Trauma impacts the fear circuitry centers of the brain, leading to altered activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the amygdala, as well as chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system and stress-released hormones, all of which are potential pathways that dysregulate the brain-gut relationship.11-13 Worries for safety, which are reactivated by physiological cues (e.g., GI symptoms, pain), as well as avoidance of potential triggers of GI symptoms (e.g., food, exercise, medications, and situations such as travel or scheduled events, and fear of being trapped without bathroom access), are common. Traumatized individuals can experience a foreshortened sense of the future, which may lead to decreased investment in long-term determinants of health (e.g., balanced diet, exercise, social support) and have higher rates of functional impairment and higher health care utilization.14 Negative mood, including irritability, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and impaired concentration are common in those with trauma and chronic pain and can be accompanied by internalized blame (e.g., depression, substance abuse, suicidality) or externalized blame (e.g., negative relationships with health care providers, rejection from their support or faith system). These can be worsened by an impaired sense of trust, which impacts the patient-provider relationship and other sources of social support leading to lack of behavioral activation, anhedonia, and isolation.

Another commonality is hypervigilance, as those with chronic abdominal pain are often hyperaware of physical symptoms and always “on alert” for a signal indicative of a pain flare. Anxiety and depression frequently co-occur in populations with trauma and chronic pain; these diagnoses are associated with higher rates of catastrophizing and learned helplessness, which may be exacerbated by lack of a “cure” for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) and chronic pain.15 These factors could potentially lead to lack of engagement with treatment or, alternatively, risky or destructive attempts to cure pain including dangerous complementary alternative treatments or substance abuse to numb sensations. Another feature of trauma in chronic pain is the sense of dissociation from and lack of control over the body, sometimes induced by negative medical experiences (e.g., unwanted physical examinations, medication side effects, traumatic procedures, or hospitalizations).16,17

The importance of treating trauma in the management of chronic pain

Behavioral treatment is increasingly being recognized as an essential component in the management of any chronic pain syndrome.18 The most studied psychosocial interventions for chronic abdominal pain are cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and gut-focused hypnosis. CBT is usually a problem-focused, short-term intervention that can be delivered individually in the office, via group therapy, or through virtual platforms. CBT is most effective when cognitive distortions and ineffective behaviors create emotional distress, and the therapy targets patient’s stress reactivity, visceral anxiety, catastrophizing, and inflexible coping styles.5 Gut-focused hypnosis is the second most–studied behavioral treatment for chronic abdominal pain and utilizes the trance state to make positive suggestions leading to broad and lasting physiological and psychological improvement.19 In addition to pain management, both CBT and hypnosis are efficacious treatments for PTSD.20,21

Utilizing a multidisciplinary medical team including integrated behavioral experts, such as in a patient-centered medical home, is considered the standard of care for treatment of chronic pain. The patient-provider relationship is essential, as is consistent follow-up to ensure effective symptom management and improvements in quality of life. Additionally, patient education, including a positive (i.e., clear) diagnosis and information on the brain-gut relationship, is associated with symptom improvement. In our subspecialty medical home for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), we found that, in our patients who were on opioids for their chronic pain, engagement with our embedded behavioral and pain specialists resulted in significant reduction in opioid use and depression as well as improved self-reported quality of life.22 Gastroenterologists and advanced-practice providers operating without embedded behavioral therapists can consider referring patients to behavioral treatment (e.g., licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, marriage and family therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists; the latter often specialize in medication management and may not offer behavioral therapy) for trauma if patients have undergone a traumatic event (e.g., exposure to any potentially life-threatening event, serious injury, or violence) at any point in their lifetime and are experiencing intrusive symptoms (e.g., memories, dreams, or flashbacks to trauma), avoidance of trauma reminders, and negative mood or hyperarousal related to traumatic events (Table 1).23

With the traumatization component of chronic abdominal pain, which can further drive maladaptive coping cycles, incorporation of trauma-informed treatment into gastroenterology clinics is an avenue toward more effective treatment. The core principles of trauma-informed care include safety, choice, collaboration, trustworthiness, and empowerment,24 and are easily aligned with patient-centered models of care such as the interdisciplinary medical home model. Incorporation of screening techniques, interdisciplinary training of clinicians, and use of behavioral providers with experience in evidenced-based treatments of trauma enhance a clinic’s ability to effectively identify and treat individuals who have trauma because of their abdominal pain.25 Additionally, the most common behavioral interventions for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are also efficacious in the treatment of trauma. CBT is a well-validated treatment for PTSD that utilizes exposure therapy to help individuals restructure negative beliefs shaped by their negative experience and develop relaxation skills. Hypnosis is also validated in the treatment of trauma, with the possible mechanism of action being the replacement of the negative or dissociated traumatic trance with a healthy, adaptive trance facilitated by the hypnotherapist.21

Adjunctive nonopioid medications for chronic abdominal pain

While there are few randomized controlled trials establishing efficacy of pharmacotherapy for sustained improvement of abdominal pain or related suffering, several small trials and consensus clinical expert opinion suggest partial improvement in these domains.26,27 Central neuromodulators that can attenuate chronic visceral pain include antidepressants, antipsychotics, and other central nervous system–targeted medications.26 Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine) are often first-line treatment for FGIDs.28 Serotonin noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (e.g., duloxetine, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, milnacipran) are also effective in pain management. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) can be used, especially when comorbid depression, anxiety, and phobic disorders are present. Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., mirtazapine, mianserin, trazodone) are effective treatments for early satiety, nausea/vomiting, insomnia, and low weight. Augmenting agents are utilized when single agents do not provide maximum benefit, including quetiapine (disturbed sleep), bupropion (fatigue), aripiprazole, buspirone, and tandospirone (dyspeptic features and anxiety). Delta ligands including gabapentin and pregabalin are helpful for abdominal wall pain or fibromyalgia. Ketamine is a newer but promising pathway for treatment of pain and depression and is increasingly being utilized in outpatient settings. Additionally, partial opioid-receptor agonists including methadone and suboxone have been reported to decrease pain in addition to their efficacy in addiction recovery. Medical marijuana is another area of growing interest, and while research has yet to show a clear effect in pain management, it does appear helpful in nausea and appetite stimulation. Obtaining a therapeutic response is the first treatment goal, after which a patient should be monitored in at least 6-month intervals to ensure sustained benefits and tolerability, and if these are not met, enhancement of treatment or a slow taper is indicated. As in all treatments, a positive patient-provider relationship predicts improved treatment adherence and outcomes.26 However, while these pharmacological interventions can reduce symptom severity, there is little evidence that they reduce traumatization without adjunctive psychotherapy.29

Summary

Both behavioral and pharmacological treatment options are available for chronic abdominal pain and most useful if traumatic manifestations are assessed and included as treatment targets. A multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of chronic abdominal pain with increased screening and treatment of trauma is a promising pathway to improved care and management for patients with chronic pain. If trauma is left untreated, the benefits of otherwise effective treatments are likely to be significantly limited.

References

1. Apkarian AV et al. Prog Neurobiol. 2009 Feb;87(2):81-97.

2. Gallagher RM et al. Pain Med. 2011 Jan;12(1):1-2.

3. Collier R et al. CMAJ. 2018 Jan 8;190(1):E26-7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-5523.

4. Szigethy E et al. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2018;15:168-80.

5. Ballou S et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017 Jan;8(1):e214.

6. Egloff N et al. J Pain Res. 2013 Nov 5;6:765-70.

7. Fashler S et al. J Pain Res. 2016 Aug 10;9:551-61.

8. McKernan LC et al. Clin J Pain. 2019 May;35(5):385-93.

9. Ju T et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018 Dec 19. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001153.

10. Fishbain DA et al. Pain Med. 2017 Apr 1;18(4):711-35.

11. Martin CR et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;6(2):133-48.

12. Osadchiy V et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jan;17(2):322-32.

13. Brzozowski B et al. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016 Nov;14(8):892-900.

14. Outclat SD et al. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1872-9.

15. Asmundson GJ et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;Dec;47(10):930-7.

16. Taft TH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar 7. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz032.

17. Duckworth MP et al. International Journal of Rehabilitation and Health, 2000 Apr;5(2):129-39.

18. Scascighini L et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 May;47(5):670-8.

19. Palsson O et al. European Gastroenterology & Hepatology Review. 2010;6(1):42-6.

20. Watkins LE et al. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2018;12:1-9.

21. O’Toole SK et al. J Trauma Stress. 2016 Feb;29(1):97-100.

22. Goldblum Y et al. Digestive Disease Week. San Diego. 2019. Abstract in press.

23. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (of Mental Disorders), Fifth Edition. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

24. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2018. Trauma-informed approach and trauma-specific interventions. Retrieved from samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions.

25. Click BH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(5):681-94.

26. Drossman DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1140-71.

27. Thorkelson G et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Jun 1;22(6):1509-22.

28. Törnblom H et al. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2018;20(12):58.

29. Watkins LE et al. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:258.

30. American Psychiatric Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults. 2017.

31. Bisson JI et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Dec 13;(12):CD003388.

32. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DOD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. 2017.

33. Karatzias T et al. Psychol Med. 2019 Mar 12:1-15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719000436. Advance online publication.

Emily Weaver, LCSW, is a UPMC Total Care–IBD program senior social worker, Eva Szigethy, MD, PhD, is professor of psychiatry and medicine, codirector, IBD Total Care Medical Home, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, departments of medicine and psychiatry.

Constructing an inflammatory bowel disease patient–centered medical home

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are life-long chronic diseases with high morbidity. There has been remarkable progress in the understanding of disease pathophysiology, leading to new medical therapies and surgical approaches for the management of IBD. These trends have resulted in a marked increase in the cost of IBD care, with current estimates ranging from $14 to $31 billion in both direct and indirect costs in the United States.1

IBD patients have unique behavioral, preventive, and therapeutic care requirements.2,3 Because of the complexity of care, there is a large degree of segmentation and fragmentation of IBD management across health care systems and among multiple providers. This siloed approach often falls short of seamless, efficient, high-quality, patient-centered care.

To address the increasing costs and fragmentation of chronic disease management, population-based health care has emerged as a new concept with an emphasis on reward for value, not volume. Two such examples of population-based health care include accountable care organizations and patient-centered medical homes. This concept relies on the development of new payment models and shifts the risk to the providers.4,5 Primary care providers play a central coordinating role in these new models.6,7 However, the role of specialists is less well defined, with limited sharing of risk for the care and costs of populations.

The IBD specialty medical home (SMH) implemented at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) is an example of a new model of care. The IBD SMH is constructed to align incentives and provide up-front resources to manage a population of patients with IBD optimally – including treatment of their inflammatory disease, coexisting pain, and psychological issues.8-10 In the case of the IBD SMH, the gastroenterologist is the principal provider for a cohort of IBD patients. The gastroenterologist is responsible for the coordination and management of health care of this population and places the IBD patient at the center of the medical universe.

In this article, we draw from our rich partnership between the UPMC Health Plan (HP) and Health System to describe the construction and deployment of the IBD SMH. Although this model is new and we still are learning, we already have seen an improvement in the overall quality of life, decreased utilization, and reduction in total cost of care for this IBD SMH population.

Constructing an IBD medical home: where to begin?

In conjunction with the UPMC HP, we designed and established an IBD patient-centered SMH, designated in July 2015 as UPMC Total Care–Inflammatory Bowel Disease.11 The development of the medical home was facilitated by our unique integrated delivery and finance system. The UPMC HP provided important utilization data on their IBD population, which allowed for focused enrollment of the highest-utilizer patients. In addition, the UPMC HP funded positions that we hired directly as employees of our IBD SMH. These positions included the following: two nurse coordinators, two certified nurse practitioners, a dietitian, a social worker, and a psychiatrist. The UPMC HP also provided their own HP employees to work with our IBD SMH: The rare and chronic disease team included two nurses and a social worker who made house calls for a select group of patients (identified based on the frequency of their health care use). The HP also provided health coaches who worked directly with our patients on lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and exercise programs. Finally, the UPMC HP worked with the IBD SMH to provide support for a variety of operational functions. Examples of these important efforts included data analytics through their department of health economics, regular collaboration to assist the provider team in modifying the program, publicizing the IBD SMH to their members, and facilitating approval of IBD medications through their pharmacy department.

We acknowledge that the development and implementation of an IBD SMH will vary from region to region and depend on the relationship of payers and providers. Thus, the blueprint of our UPMC IBD Medical Home may not be replicated readily in other centers or regions. However, there are several core elements that we believe are necessary in constructing any SMH: 1) a payer willing to partner with the provider, 2) a patient population with specific characteristics, 3) a physician champion, and 4) prespecified goals and measures of success.

Payer or health plan

A SMH is based on the premise that providers and payers working together can achieve more efficient, high-quality care for patients than either party working alone. Payers have essential resources for infrastructure support, preventive services delivery, marketing and engagement expertise, large databases for risk stratification and gap closure, and care management capacity to be a valuable partner. In the short term, philanthropy, grants, and crowd-sourcing options can be used to provide initial support for components of the SMH; however, these rarely are sustainable long-term options. Thus, the most critical collaboration necessary to considering a SMH is between payer(s) (insurance company or health plan) and the specialty provider.

Ideally, the local environment should consist of a single or a few large payers to ease SMH implementation. UPMC is a large integrated delivery (25 hospitals and more than 600 clinics) and financing system (more than 3 million members and is the dominant payer in the region), with a history of leveraging payer–provider partnerships to achieve better patient care, education, and research, and thus served as an ideal collaborator in the design and launch of the IBD SMH. Most physicians in the United States do not work in an integrated payer–provider health delivery system, and partnering with a large regional payer with an interest in specialty population-based chronic care is reasonable for constructing an SMH in your medical neighborhood.

Patient population

In addition to having a collaborative health plan with large population coverage, there must exist a substantial IBD population managed by gastroenterologists. There must be a sufficient number of high-utilizer, high-cost members to justify up-front capital expenditure and return on investment. To determine the feasibility and utility of creating an IBD SMH at UPMC, we collected baseline data on the following: 1) the number of IBD patients within our IBD center and health plan, 2) a hotspotting analysis for our Pennsylvania counties, and 3) health care utilization of the IBD population of interest. At the time of the SMH inception, there were 6,319 Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patients (including all insurance plans) in our center, with more than 3,500 members insured by our HP. There was a 30% increase in new IBD patients to our center in the 3 years before starting the IBD SMH, and the HP had a 27% increase in overall IBD members. Based on a regional hotspotting analysis, $24.3 million of the annual total of $36.9 million was related to hospitalization costs from our IBD patients. The high-utilizer patients accounted for most of the total cost of care for our HP; 16% accounted for 48% of the per-member per-month cost and 29% accounted for 79% of the total annual cost. These baseline data supported justification for an IBD SMH.

Although there is no absolute minimum number of members (patients) required, and the SMH model can be scaled to various IBD populations, we believe that at least 1,000 patients covered by a single insurer must exist. The justification for the 1,000 patients is an estimate of the number of high-utilizer patients who would be required to justify a cost savings, and ultimately a return on investment. We calculated that at least 300 high-utilizer patients would need to be included in our IBD SMH to show a reduction in health care utilization and total cost of care. Therefore, if we assume that approximately 30% of any chronic disease population drives the majority of cost and represents the highest utilizers, we estimated that at least 1,000 patients should be covered by a single insurer.

For development of an SMH, there are two approaches that may be taken: Design the medical home for the entire Health Plan’s population of patients with the disease of interest, or focus only on the high-utilizing, most expensive patients. The latter will include a more complex and challenging cohort of patients, but likely will provide the opportunity to show a reduction in utilization and total cost of care than a broader all-comers population approach.

Physician champions

A successful SMH requires a physician (or health care provider) champion. IBD care within the SMH is unique and distinct from gastroenterologists’ classic training and specialty care. In addition to addressing the biologic disease, the emphasis is on whole-patient care: preventive care, behavioral medicine, socioeconomic considerations of the patient, and provision of care for nongastrointestinal symptoms and diseases. In an SMH, the specialist must be willing to incorporate and address all facets of health care to improve patient outcomes.

Goals and measures of success

To ensure successful deployment of an SMH, it is important to establish shared payer–provider goals and metrics during the construction phase of the medical home. These goals should include an enrollment target number for each year, quality improvement metrics, patient experience outcomes, and metrics for a reduction in health care utilization and total cost of care. Examples of our IBD SMH year 1 and year 2 goals are outlined in Supplementary Table 1 (at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.026). In the first year of our IBD SMH, we were able to achieve our goals, and publication of our results is forthcoming. We have enrolled more than 325 patients, retained 90%, reduced emergency room visits and hospitalizations by 50%, and significantly improved quality of life. Most of our patients have been assigned an HP coach and use the electronic medical portal to communicate with the medical home. Our patient satisfaction for physician communication was 99%.

Key components of the IBD medical home

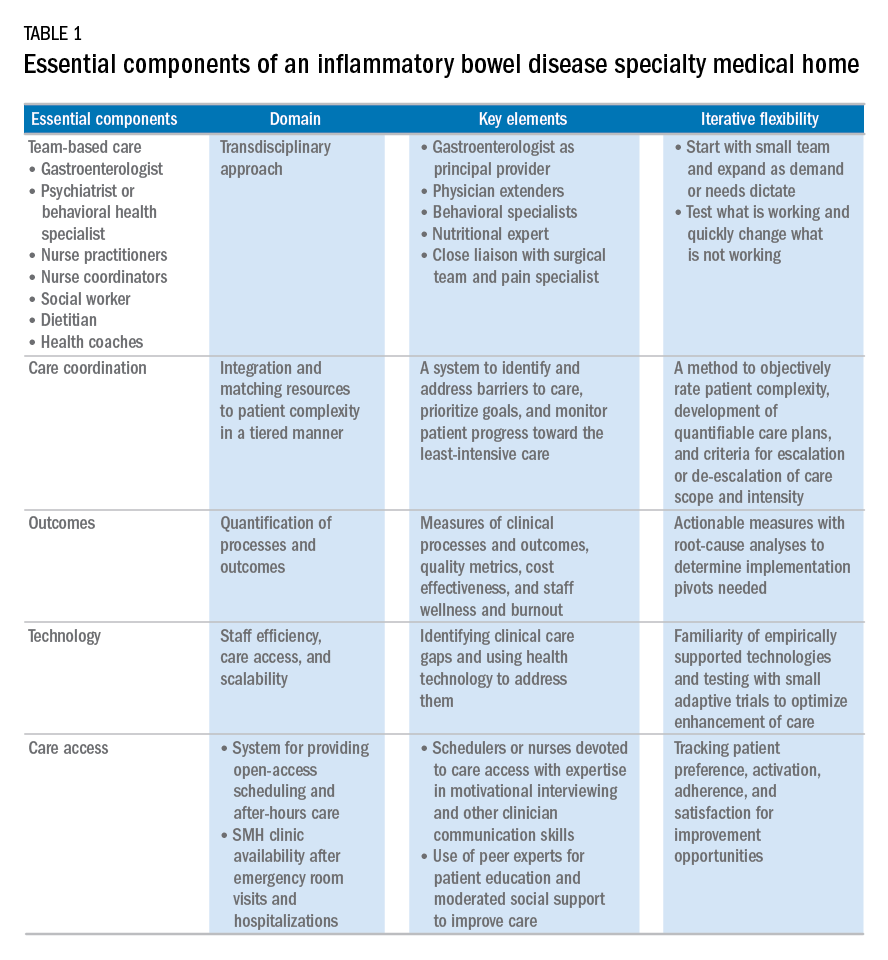

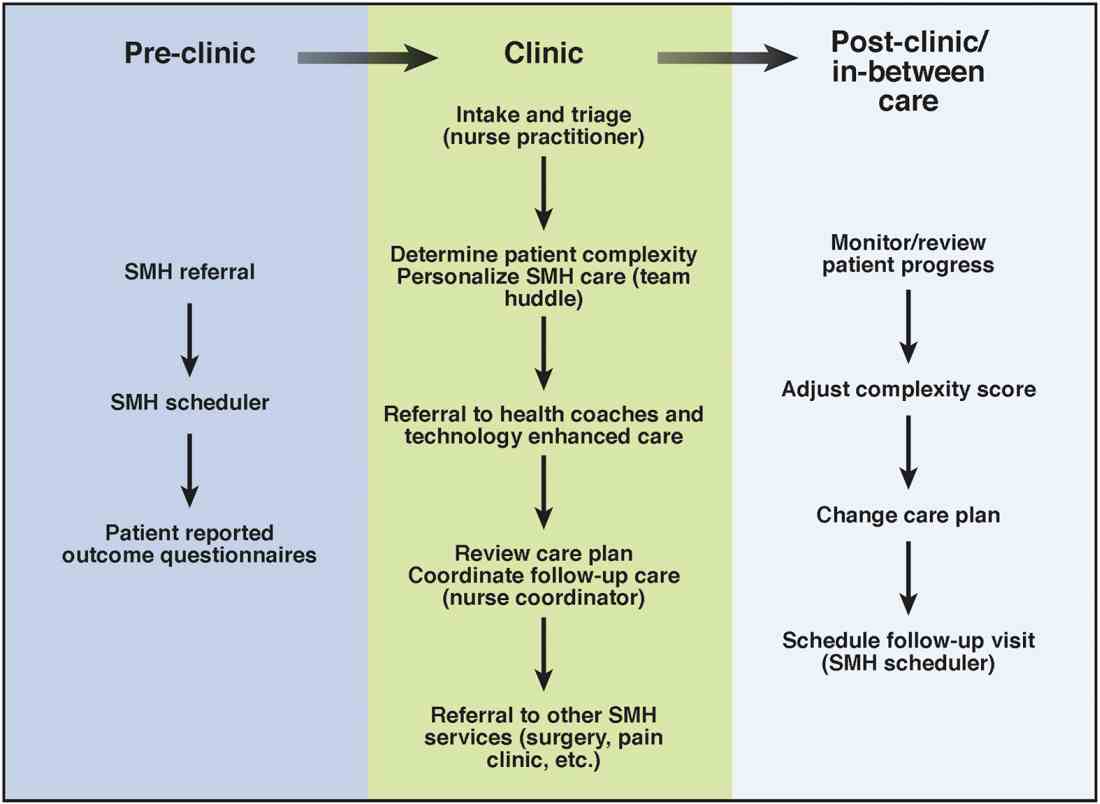

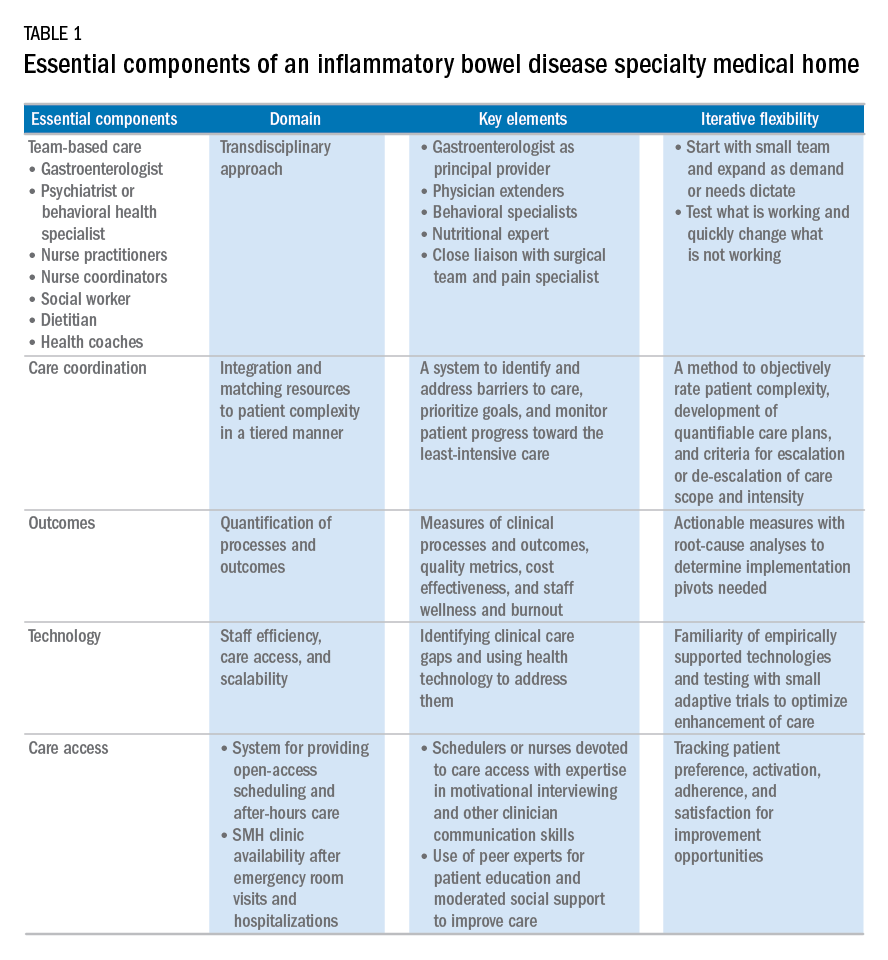

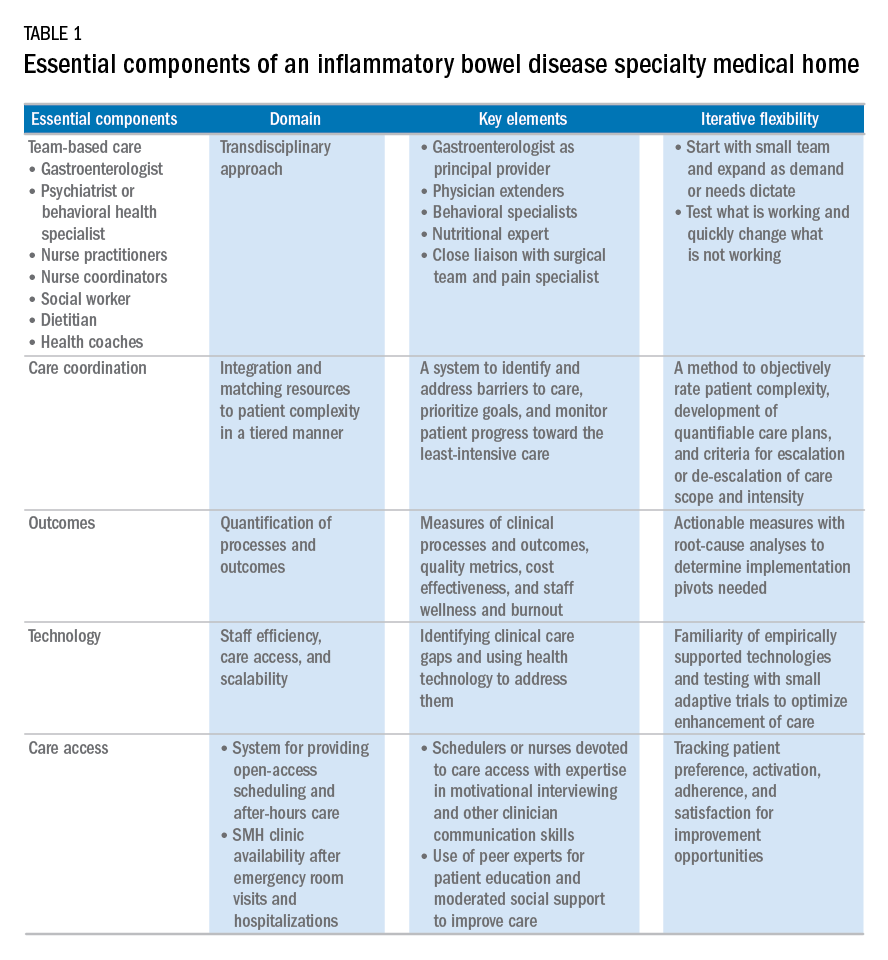

Based on our experience, we believe the following are key components of a successful IBD SMH: 1) team-based care with physician extenders, nurse coordinators, schedulers, social workers, and dietitians as essential members of the IBD SMH; 2) effective care coordination to reduce barriers to comprehensive biopsychosocial care; 3) tracking of process and outcome metrics of interest; 4) appropriate use of technology to enhance clinical care; and 5) care access (e.g., open-access appointments), after-hours care, and follow-up care after emergency room visits and hospitalizations (Table 1).

Although the eventual goal of an IBD SMH is to consolidate health care for all IBD patients, the initial launch stages are more likely to succeed if the SMH focuses on the subgroup of IBD patients who use health care excessively, often in an unplanned fashion (e.g., emergency department visits or hospitalizations). In conjunction with a payer, it is easy to identify the most costly IBD patients in a cohort. For example, for initial enrollment, the UPMC IBD SMH selected patients between the ages of 18 and 55 years, with confirmed Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, and evidence that IBD was a primary driver of patients’ health care utilization; the latter was defined if the majority of health care expenditures in the prior year was related to IBD (as judged by International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th revisions, primary and secondary diagnoses).

Team-based care

A central component to our IBD SMH was the creation of an integrated team. Supplementary Table 2 (at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.026) describes various positions that are vital for a successful SMH. For a team approach to be most effective, there needs to be clear definitions or roles and role overlaps so that team members can work as a cohesive, organized, and efficient unit. Physician extenders are critical to the model’s success and are trained to make routine IBD care decisions, provide basic primary care, and coordinate care with the gastroenterologist to meet patient needs. The staff-to-patient ratio requirements may vary from region to region and from SMH to SMH. The nurse coordinators and physician extenders assume the burden of day-to-day patient care, and are supervised by the gastroenterologist and psychiatrist. In our UPMC IBD SMH, the ratio of one nurse coordinator and one certified nurse practitioner per 500 patients is sufficient. In addition, one social worker, one dietitian, one scheduler, one gastroenterologist, and one psychiatrist per 1,000 patients is our current model. To date, we have enrolled more than 500 patients, and through funding from our UPMC HP, we have just hired our second nurse coordinator and second nurse practitioner in anticipation of 1,000 patients by year 4.

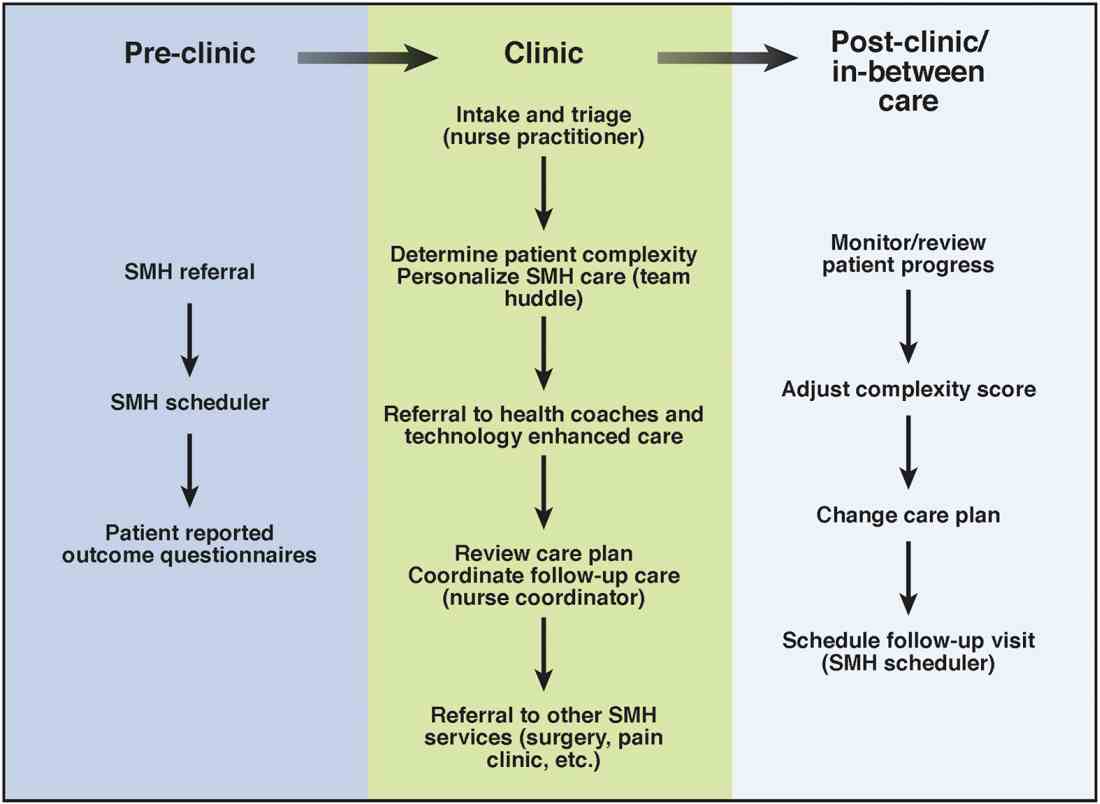

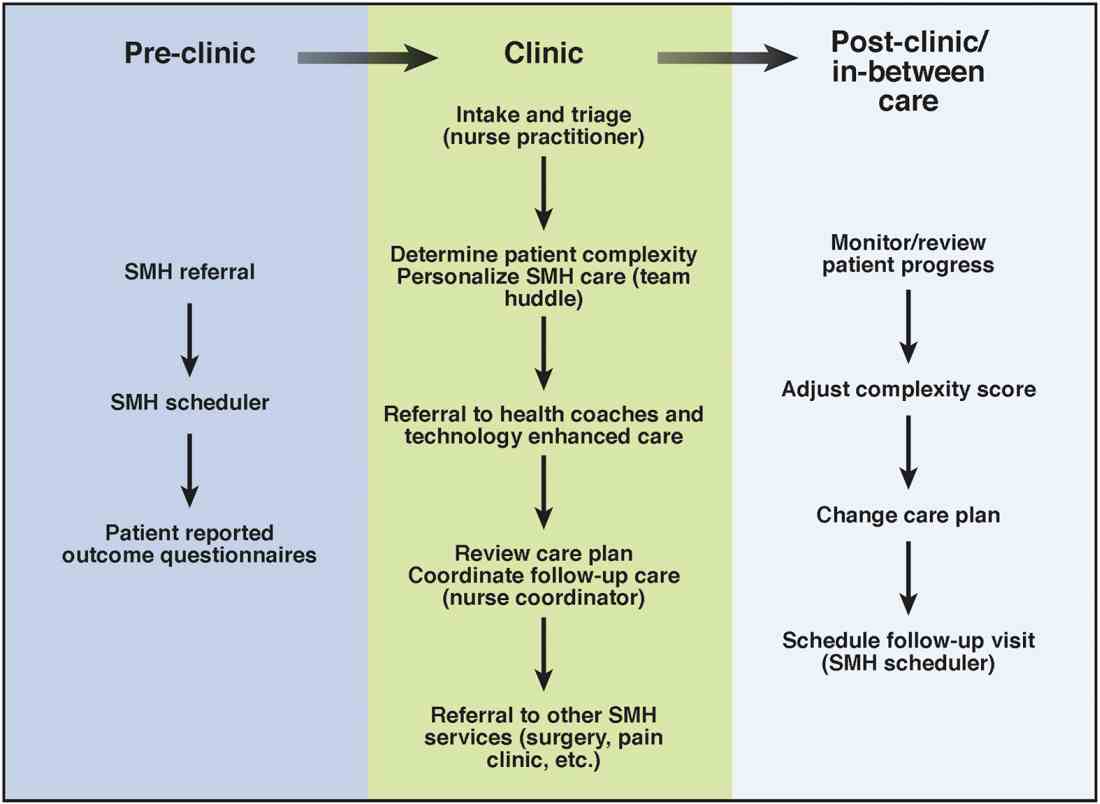

Care coordination and incorporation of technology

The team composition is organized to provide tiered care for optimal efficiency. For such a stepped care model to be effective and scalable, two components are essential. The first component is a care coordination system that allows for the reliable classification of the biological, psychological, social, and health systems barriers faced by patients. To this end, our SMH developed an IBD-specific complexity grid (Supplementary Table 3; at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.026) that was derived from a primary care model.12 The second component is the use of technology-enhanced care to scale delivery of services in a population health model. Examples of technology in our SMH include the use of telemedicine/telepsychiatry by secure video, health coach virtual visits, remote monitoring, and provider-assisted behavioral interventions that patients can access on their smart phones.

New payment models for specialty medical homes

The SMH transitions away from relative value unit–based reimbursement and toward a value-based paradigm. In the SMH, the gastroenterologist serves as the principal medical provider for the IBD patient. Both providers and payers will be able to refer patients to the SMH. Data on quality metrics will be tracked and physician extenders and nurse coordinators will help ensure that goals are met. Quality improvement, preventive medicine, telemedicine, and point-of-contact mental health care will replace the volume-based relative value unit system.

Alternative payment models will be required to support the SMH. Because of the novel nature of the SMH, the optimal payment model has yet to be determined, but probably will include either a shared savings or global cap approach, with an emphasis on the total cost of care reduction. This means that the specialist in the SMH must be aware of all care, and the cost of care, that the patient receives. Biologics and other IBD therapy costs are high and will continue to increase. The sustainable model must be sufficiently supple to not disincentivize the provider to use proven and effective, albeit expensive, therapy for patients who need it most. A close working relationship between the SMH providers and the health plan chief pharmacy officer will be essential. We expect that appropriate use of medications will lead to a medical cost offset with improved IBD outcomes, a reduction in health care utilization, and optimized work and life productivity.

Conclusions

In new models of care, specialty providers partner with payers in a patient-centered system to provide principal care for patients with chronic diseases, including IBD, in an effort to reduce costs and provide efficient, high-quality care. These models will require close collaborations with payers, a sufficiently large patient population, a physician champion, and a multidisciplinary staff targeting various aspects of health care. Successful implementation of such models will help reduce costs of care while improving the patient-centered experience and outcomes.

Supplementary material

To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology at www.cghjournal.org, and at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.026.

References

1. Mehta F. Report: economic implications of inflammatory bowel disease and its management. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(Suppl):s51-60.

2. Mikocka-Walus A., Knowles S.R., Keefer L., et al. Controversies revisited: a systematic review of the comorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:752-62.

3. Regueiro M., Greer J.B., Szigethy E. Etiology and treatment of pain and psychosocial issues in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:430-9.e4.

4. Silow-Carroll S., Edwards J.N., Rodin D. How Colorado, Minnesota, and Vermont are reforming care delivery and payment to improve health and lower costs. Issue Brief. (Commonw Fund) 2013;10:1-9.

5. Fogelman C., Gates T. A primary care perspective on U.S. health care: part 2: thinking globally, acting locally. J Lancaster Gen Hospital. 2013;8:101-5.

6. Rosenthal M.B., Sinaiko A.D., Eastman D., et al. Impact of the Rochester medical home initiative on primary care practices, quality, utilization, and costs. Med Care. 2015;53:967-73.

7. Friedberg M.W., Rosenthal M.B., Werner R.M., et al. Effects of a medical home and shared savings intervention on quality and utilization of care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1362-8.

8. Fernandes S.M., Sanders L.M. Patient-centered medical home for patients with complex congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27:581-6.

9. Mikocka-Walus A.A., Andrews J.M., Bernstein C.N., et al. Integrated models of care in managing inflammatory bowel disease: a discussion. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1582-7.

10. Kessler R., Miller B.F., Kelly M., et al. Mental health, substance abuse, and health behavior services in patient-centered medical homes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27:637-44.

11. Regueiro M.D., McAnallen S.E., Greer J.B., et al. The inflammatory bowel disease specialty medical home: a new model of patient centered care. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1971-80.

12. Lobo E., Ventura T., Navio M., et al. Identification of components of health complexity on internal medicine units by means of the INTERMED method. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69:1377-86.

Dr. Regueiro and Dr. Click are in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; Ms. Holder, Dr. Shrank, and Ms. McAnAllen are in the Insurance Services Division, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and Dr. Szigethy is in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Dr. Regueiro serves as a consultant for, on advisory boards for, and receives research support from Abbvie, Janssen, and Takeda; and Dr. Szigethy serves as a consultant for Abbvie. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are life-long chronic diseases with high morbidity. There has been remarkable progress in the understanding of disease pathophysiology, leading to new medical therapies and surgical approaches for the management of IBD. These trends have resulted in a marked increase in the cost of IBD care, with current estimates ranging from $14 to $31 billion in both direct and indirect costs in the United States.1

IBD patients have unique behavioral, preventive, and therapeutic care requirements.2,3 Because of the complexity of care, there is a large degree of segmentation and fragmentation of IBD management across health care systems and among multiple providers. This siloed approach often falls short of seamless, efficient, high-quality, patient-centered care.

To address the increasing costs and fragmentation of chronic disease management, population-based health care has emerged as a new concept with an emphasis on reward for value, not volume. Two such examples of population-based health care include accountable care organizations and patient-centered medical homes. This concept relies on the development of new payment models and shifts the risk to the providers.4,5 Primary care providers play a central coordinating role in these new models.6,7 However, the role of specialists is less well defined, with limited sharing of risk for the care and costs of populations.

The IBD specialty medical home (SMH) implemented at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) is an example of a new model of care. The IBD SMH is constructed to align incentives and provide up-front resources to manage a population of patients with IBD optimally – including treatment of their inflammatory disease, coexisting pain, and psychological issues.8-10 In the case of the IBD SMH, the gastroenterologist is the principal provider for a cohort of IBD patients. The gastroenterologist is responsible for the coordination and management of health care of this population and places the IBD patient at the center of the medical universe.

In this article, we draw from our rich partnership between the UPMC Health Plan (HP) and Health System to describe the construction and deployment of the IBD SMH. Although this model is new and we still are learning, we already have seen an improvement in the overall quality of life, decreased utilization, and reduction in total cost of care for this IBD SMH population.

Constructing an IBD medical home: where to begin?

In conjunction with the UPMC HP, we designed and established an IBD patient-centered SMH, designated in July 2015 as UPMC Total Care–Inflammatory Bowel Disease.11 The development of the medical home was facilitated by our unique integrated delivery and finance system. The UPMC HP provided important utilization data on their IBD population, which allowed for focused enrollment of the highest-utilizer patients. In addition, the UPMC HP funded positions that we hired directly as employees of our IBD SMH. These positions included the following: two nurse coordinators, two certified nurse practitioners, a dietitian, a social worker, and a psychiatrist. The UPMC HP also provided their own HP employees to work with our IBD SMH: The rare and chronic disease team included two nurses and a social worker who made house calls for a select group of patients (identified based on the frequency of their health care use). The HP also provided health coaches who worked directly with our patients on lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and exercise programs. Finally, the UPMC HP worked with the IBD SMH to provide support for a variety of operational functions. Examples of these important efforts included data analytics through their department of health economics, regular collaboration to assist the provider team in modifying the program, publicizing the IBD SMH to their members, and facilitating approval of IBD medications through their pharmacy department.

We acknowledge that the development and implementation of an IBD SMH will vary from region to region and depend on the relationship of payers and providers. Thus, the blueprint of our UPMC IBD Medical Home may not be replicated readily in other centers or regions. However, there are several core elements that we believe are necessary in constructing any SMH: 1) a payer willing to partner with the provider, 2) a patient population with specific characteristics, 3) a physician champion, and 4) prespecified goals and measures of success.

Payer or health plan

A SMH is based on the premise that providers and payers working together can achieve more efficient, high-quality care for patients than either party working alone. Payers have essential resources for infrastructure support, preventive services delivery, marketing and engagement expertise, large databases for risk stratification and gap closure, and care management capacity to be a valuable partner. In the short term, philanthropy, grants, and crowd-sourcing options can be used to provide initial support for components of the SMH; however, these rarely are sustainable long-term options. Thus, the most critical collaboration necessary to considering a SMH is between payer(s) (insurance company or health plan) and the specialty provider.

Ideally, the local environment should consist of a single or a few large payers to ease SMH implementation. UPMC is a large integrated delivery (25 hospitals and more than 600 clinics) and financing system (more than 3 million members and is the dominant payer in the region), with a history of leveraging payer–provider partnerships to achieve better patient care, education, and research, and thus served as an ideal collaborator in the design and launch of the IBD SMH. Most physicians in the United States do not work in an integrated payer–provider health delivery system, and partnering with a large regional payer with an interest in specialty population-based chronic care is reasonable for constructing an SMH in your medical neighborhood.

Patient population

In addition to having a collaborative health plan with large population coverage, there must exist a substantial IBD population managed by gastroenterologists. There must be a sufficient number of high-utilizer, high-cost members to justify up-front capital expenditure and return on investment. To determine the feasibility and utility of creating an IBD SMH at UPMC, we collected baseline data on the following: 1) the number of IBD patients within our IBD center and health plan, 2) a hotspotting analysis for our Pennsylvania counties, and 3) health care utilization of the IBD population of interest. At the time of the SMH inception, there were 6,319 Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patients (including all insurance plans) in our center, with more than 3,500 members insured by our HP. There was a 30% increase in new IBD patients to our center in the 3 years before starting the IBD SMH, and the HP had a 27% increase in overall IBD members. Based on a regional hotspotting analysis, $24.3 million of the annual total of $36.9 million was related to hospitalization costs from our IBD patients. The high-utilizer patients accounted for most of the total cost of care for our HP; 16% accounted for 48% of the per-member per-month cost and 29% accounted for 79% of the total annual cost. These baseline data supported justification for an IBD SMH.

Although there is no absolute minimum number of members (patients) required, and the SMH model can be scaled to various IBD populations, we believe that at least 1,000 patients covered by a single insurer must exist. The justification for the 1,000 patients is an estimate of the number of high-utilizer patients who would be required to justify a cost savings, and ultimately a return on investment. We calculated that at least 300 high-utilizer patients would need to be included in our IBD SMH to show a reduction in health care utilization and total cost of care. Therefore, if we assume that approximately 30% of any chronic disease population drives the majority of cost and represents the highest utilizers, we estimated that at least 1,000 patients should be covered by a single insurer.

For development of an SMH, there are two approaches that may be taken: Design the medical home for the entire Health Plan’s population of patients with the disease of interest, or focus only on the high-utilizing, most expensive patients. The latter will include a more complex and challenging cohort of patients, but likely will provide the opportunity to show a reduction in utilization and total cost of care than a broader all-comers population approach.

Physician champions

A successful SMH requires a physician (or health care provider) champion. IBD care within the SMH is unique and distinct from gastroenterologists’ classic training and specialty care. In addition to addressing the biologic disease, the emphasis is on whole-patient care: preventive care, behavioral medicine, socioeconomic considerations of the patient, and provision of care for nongastrointestinal symptoms and diseases. In an SMH, the specialist must be willing to incorporate and address all facets of health care to improve patient outcomes.

Goals and measures of success

To ensure successful deployment of an SMH, it is important to establish shared payer–provider goals and metrics during the construction phase of the medical home. These goals should include an enrollment target number for each year, quality improvement metrics, patient experience outcomes, and metrics for a reduction in health care utilization and total cost of care. Examples of our IBD SMH year 1 and year 2 goals are outlined in Supplementary Table 1 (at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.026). In the first year of our IBD SMH, we were able to achieve our goals, and publication of our results is forthcoming. We have enrolled more than 325 patients, retained 90%, reduced emergency room visits and hospitalizations by 50%, and significantly improved quality of life. Most of our patients have been assigned an HP coach and use the electronic medical portal to communicate with the medical home. Our patient satisfaction for physician communication was 99%.

Key components of the IBD medical home

Based on our experience, we believe the following are key components of a successful IBD SMH: 1) team-based care with physician extenders, nurse coordinators, schedulers, social workers, and dietitians as essential members of the IBD SMH; 2) effective care coordination to reduce barriers to comprehensive biopsychosocial care; 3) tracking of process and outcome metrics of interest; 4) appropriate use of technology to enhance clinical care; and 5) care access (e.g., open-access appointments), after-hours care, and follow-up care after emergency room visits and hospitalizations (Table 1).