User login

Removing barriers to high-value IBD care: Challenges and opportunities

Over the last several years, payer policies that dictate and restrict treatments for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) have proliferated. The implementation of new coverage restrictions, expansion of services and procedures requiring prior authorization (PA), and dosing and access restriction to covered drugs, and the requirement of repeated treatment reviews including nonmedical switching for stable patients are widespread. The AGA administered a member needs assessment survey in December 2021 to determine the extent to which these policies harm patients and overburden gastroenterologists and their staff.

Survey findings

Most of the 100 surveyed members reported facing administrative burdens that prevented timely access to patient care. Utilization management practices such as PA, step therapy, and nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions create critical barriers to high quality GI care for patients with chronic conditions and jeopardize the physician-patient relationship. At a time when physicians have faced unprecedented challenges because of the public health emergency from the COVID-19 pandemic, these burdens also contribute to increasing physician burnout.

Prior authorization: Among AGA members, 96% of members said that PA is burdensome, with 61% indicating that it is significantly burdensome. Almost 99% of members indicated that PA has a negative impact on patients’ access to clinically appropriate treatments; 89% reported that the burden associated with PA has increased over the last 5 years in their practice.

Step therapy: Among members, 87% described the impact step therapy has on their practice as burdensome. Almost 90% of members said step therapy negatively impacted patients’ access to clinically appropriate treatments. Almost 90% of members felt that there was an overall negative impact on patient clinical outcomes for those patients who were required to follow a step therapy protocol.

Nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions: Out of all members, 86% reported an increase in nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years; 79% of members noted that these restrictions had a negative impact on patient clinical outcomes.

An increasing number of insurance companies are restricting effective biologic therapy to Food and Drug Administration–labeled doses, in direct conflict with current established best practices. It is most concerning that many patients who had been stable on optimized dosing are suddenly notified that they will no longer be able to receive the dose or treatment frequency prescribed by their physician. The concept of optimizing drug therapy based on disease activity and therapeutic drug monitoring is well established, and artificial restrictions to FDA-labeled doses force unnecessary drug deescalation. This transparent effort to reduce costs lacks evidence for safety. Our sickest patients often require higher doses for induction in order to respond, given drug losses, yet some payers refuse to cover the doses these patients require. This new payer-centered effort prioritizes cost containment over the judgment of the treating physician. It causes direct patient harm risking efficacy or loss of response, and subsequent irreversible disease-related complications.

Medicare drug costs

Medicare patients receiving self-injectable or oral medications are not eligible for co-pay assistance programs through pharmaceutical companies because of federal rules. For non-Medicare patients, these programs reduce the co-pay costs to as low as $5 per month. Medicare patients are able to receive infusions like infliximab and vedolizumab at no cost. However, any self-injectable or oral agent can carry a co-pay of over $1,000. Other than for patients meeting income-based eligibility requirements (e.g., below the poverty line), these treatments become prohibitively expensive. Thousands of patients have had to discontinue their self-injectable and/or oral medications because of this cost or have been denied access to the therapy altogether because of cost.

Need for change

These recent changes in insurance policies have resulted in increased harm to our patients with IBD rather than improving the safety or quality of their care. These changes create barriers to disease treatment and have not improved quality of care, patient outcomes, or quality of life. The AGA and other societies have published multiple guidelines and literature on the management of patients with IBD that should serve as the foundation for insurers’ medication coverage policies. Additionally, insurance companies should seek input from panels of IBD experts when developing their medication coverage policies to ensure they are patient oriented and facilitate high-quality IBD care.

The following are opportunities for insurers to improve the IBD drug approval process:

- Simplify the appeal process.

- Guarantee rapid response/turnaround to appeal processes to avoid additional delays in care.

- Incorporate experienced expert review by a gastroenterologist.

- Ensure coverage of drug and disease monitoring.

- Integrate expert input in policy development.

Conclusion

Effective patient care in IBD, as well as in other chronic gastrointestinal diseases, requires a collaborative approach to maximize clinical outcomes. It is an exciting time in our field, with rapidly expanding therapeutic options to treat IBD that have the potential to modify the disease course and prevent long-term complications for patients. However, optimizing the use of these treatments to achieve disease remission is challenging and requires the ability to individualize the timely choice of medications at the right dose for each patient to capture and monitor response. The ability to provide individualized, data driven care is essential to improving the quality of life of our patients, as well as to reducing health care spending over time.

Achieving high-value care is a goal that benefits everyone involved in the health care system. Policies that interfere with the timely treatment of sick patients with the right therapies, optimized to achieve disease remission, hurt the very patients that our health care system exists to serve. We cannot stand by while impediments to treatment result in harm to our patients and worsen clinical outcomes. Collaboratively developing aligned incentives can lead us to patient-centered policies that fulfill a shared purpose to optimize the health of people with chronic digestive diseases.

The authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Dr. Feuerstein is with the Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and is an associate professor of medicine Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Sofia is an assistant professor of medicine with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. Dr. Guha is a professor of medicine at the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition and is codirector of the Center for Interventional Gastroenterology at UTHealth (iGUT) at UT Health Science Center, Houston. Dr. Streett is a clinical professor of medicine, gastroenterology, and hepatology and director of the IBD Education and Advanced IBD Fellowship at Stanford (Calif.) Medicine.

Over the last several years, payer policies that dictate and restrict treatments for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) have proliferated. The implementation of new coverage restrictions, expansion of services and procedures requiring prior authorization (PA), and dosing and access restriction to covered drugs, and the requirement of repeated treatment reviews including nonmedical switching for stable patients are widespread. The AGA administered a member needs assessment survey in December 2021 to determine the extent to which these policies harm patients and overburden gastroenterologists and their staff.

Survey findings

Most of the 100 surveyed members reported facing administrative burdens that prevented timely access to patient care. Utilization management practices such as PA, step therapy, and nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions create critical barriers to high quality GI care for patients with chronic conditions and jeopardize the physician-patient relationship. At a time when physicians have faced unprecedented challenges because of the public health emergency from the COVID-19 pandemic, these burdens also contribute to increasing physician burnout.

Prior authorization: Among AGA members, 96% of members said that PA is burdensome, with 61% indicating that it is significantly burdensome. Almost 99% of members indicated that PA has a negative impact on patients’ access to clinically appropriate treatments; 89% reported that the burden associated with PA has increased over the last 5 years in their practice.

Step therapy: Among members, 87% described the impact step therapy has on their practice as burdensome. Almost 90% of members said step therapy negatively impacted patients’ access to clinically appropriate treatments. Almost 90% of members felt that there was an overall negative impact on patient clinical outcomes for those patients who were required to follow a step therapy protocol.

Nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions: Out of all members, 86% reported an increase in nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years; 79% of members noted that these restrictions had a negative impact on patient clinical outcomes.

An increasing number of insurance companies are restricting effective biologic therapy to Food and Drug Administration–labeled doses, in direct conflict with current established best practices. It is most concerning that many patients who had been stable on optimized dosing are suddenly notified that they will no longer be able to receive the dose or treatment frequency prescribed by their physician. The concept of optimizing drug therapy based on disease activity and therapeutic drug monitoring is well established, and artificial restrictions to FDA-labeled doses force unnecessary drug deescalation. This transparent effort to reduce costs lacks evidence for safety. Our sickest patients often require higher doses for induction in order to respond, given drug losses, yet some payers refuse to cover the doses these patients require. This new payer-centered effort prioritizes cost containment over the judgment of the treating physician. It causes direct patient harm risking efficacy or loss of response, and subsequent irreversible disease-related complications.

Medicare drug costs

Medicare patients receiving self-injectable or oral medications are not eligible for co-pay assistance programs through pharmaceutical companies because of federal rules. For non-Medicare patients, these programs reduce the co-pay costs to as low as $5 per month. Medicare patients are able to receive infusions like infliximab and vedolizumab at no cost. However, any self-injectable or oral agent can carry a co-pay of over $1,000. Other than for patients meeting income-based eligibility requirements (e.g., below the poverty line), these treatments become prohibitively expensive. Thousands of patients have had to discontinue their self-injectable and/or oral medications because of this cost or have been denied access to the therapy altogether because of cost.

Need for change

These recent changes in insurance policies have resulted in increased harm to our patients with IBD rather than improving the safety or quality of their care. These changes create barriers to disease treatment and have not improved quality of care, patient outcomes, or quality of life. The AGA and other societies have published multiple guidelines and literature on the management of patients with IBD that should serve as the foundation for insurers’ medication coverage policies. Additionally, insurance companies should seek input from panels of IBD experts when developing their medication coverage policies to ensure they are patient oriented and facilitate high-quality IBD care.

The following are opportunities for insurers to improve the IBD drug approval process:

- Simplify the appeal process.

- Guarantee rapid response/turnaround to appeal processes to avoid additional delays in care.

- Incorporate experienced expert review by a gastroenterologist.

- Ensure coverage of drug and disease monitoring.

- Integrate expert input in policy development.

Conclusion

Effective patient care in IBD, as well as in other chronic gastrointestinal diseases, requires a collaborative approach to maximize clinical outcomes. It is an exciting time in our field, with rapidly expanding therapeutic options to treat IBD that have the potential to modify the disease course and prevent long-term complications for patients. However, optimizing the use of these treatments to achieve disease remission is challenging and requires the ability to individualize the timely choice of medications at the right dose for each patient to capture and monitor response. The ability to provide individualized, data driven care is essential to improving the quality of life of our patients, as well as to reducing health care spending over time.

Achieving high-value care is a goal that benefits everyone involved in the health care system. Policies that interfere with the timely treatment of sick patients with the right therapies, optimized to achieve disease remission, hurt the very patients that our health care system exists to serve. We cannot stand by while impediments to treatment result in harm to our patients and worsen clinical outcomes. Collaboratively developing aligned incentives can lead us to patient-centered policies that fulfill a shared purpose to optimize the health of people with chronic digestive diseases.

The authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Dr. Feuerstein is with the Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and is an associate professor of medicine Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Sofia is an assistant professor of medicine with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. Dr. Guha is a professor of medicine at the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition and is codirector of the Center for Interventional Gastroenterology at UTHealth (iGUT) at UT Health Science Center, Houston. Dr. Streett is a clinical professor of medicine, gastroenterology, and hepatology and director of the IBD Education and Advanced IBD Fellowship at Stanford (Calif.) Medicine.

Over the last several years, payer policies that dictate and restrict treatments for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) have proliferated. The implementation of new coverage restrictions, expansion of services and procedures requiring prior authorization (PA), and dosing and access restriction to covered drugs, and the requirement of repeated treatment reviews including nonmedical switching for stable patients are widespread. The AGA administered a member needs assessment survey in December 2021 to determine the extent to which these policies harm patients and overburden gastroenterologists and their staff.

Survey findings

Most of the 100 surveyed members reported facing administrative burdens that prevented timely access to patient care. Utilization management practices such as PA, step therapy, and nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions create critical barriers to high quality GI care for patients with chronic conditions and jeopardize the physician-patient relationship. At a time when physicians have faced unprecedented challenges because of the public health emergency from the COVID-19 pandemic, these burdens also contribute to increasing physician burnout.

Prior authorization: Among AGA members, 96% of members said that PA is burdensome, with 61% indicating that it is significantly burdensome. Almost 99% of members indicated that PA has a negative impact on patients’ access to clinically appropriate treatments; 89% reported that the burden associated with PA has increased over the last 5 years in their practice.

Step therapy: Among members, 87% described the impact step therapy has on their practice as burdensome. Almost 90% of members said step therapy negatively impacted patients’ access to clinically appropriate treatments. Almost 90% of members felt that there was an overall negative impact on patient clinical outcomes for those patients who were required to follow a step therapy protocol.

Nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions: Out of all members, 86% reported an increase in nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years; 79% of members noted that these restrictions had a negative impact on patient clinical outcomes.

An increasing number of insurance companies are restricting effective biologic therapy to Food and Drug Administration–labeled doses, in direct conflict with current established best practices. It is most concerning that many patients who had been stable on optimized dosing are suddenly notified that they will no longer be able to receive the dose or treatment frequency prescribed by their physician. The concept of optimizing drug therapy based on disease activity and therapeutic drug monitoring is well established, and artificial restrictions to FDA-labeled doses force unnecessary drug deescalation. This transparent effort to reduce costs lacks evidence for safety. Our sickest patients often require higher doses for induction in order to respond, given drug losses, yet some payers refuse to cover the doses these patients require. This new payer-centered effort prioritizes cost containment over the judgment of the treating physician. It causes direct patient harm risking efficacy or loss of response, and subsequent irreversible disease-related complications.

Medicare drug costs

Medicare patients receiving self-injectable or oral medications are not eligible for co-pay assistance programs through pharmaceutical companies because of federal rules. For non-Medicare patients, these programs reduce the co-pay costs to as low as $5 per month. Medicare patients are able to receive infusions like infliximab and vedolizumab at no cost. However, any self-injectable or oral agent can carry a co-pay of over $1,000. Other than for patients meeting income-based eligibility requirements (e.g., below the poverty line), these treatments become prohibitively expensive. Thousands of patients have had to discontinue their self-injectable and/or oral medications because of this cost or have been denied access to the therapy altogether because of cost.

Need for change

These recent changes in insurance policies have resulted in increased harm to our patients with IBD rather than improving the safety or quality of their care. These changes create barriers to disease treatment and have not improved quality of care, patient outcomes, or quality of life. The AGA and other societies have published multiple guidelines and literature on the management of patients with IBD that should serve as the foundation for insurers’ medication coverage policies. Additionally, insurance companies should seek input from panels of IBD experts when developing their medication coverage policies to ensure they are patient oriented and facilitate high-quality IBD care.

The following are opportunities for insurers to improve the IBD drug approval process:

- Simplify the appeal process.

- Guarantee rapid response/turnaround to appeal processes to avoid additional delays in care.

- Incorporate experienced expert review by a gastroenterologist.

- Ensure coverage of drug and disease monitoring.

- Integrate expert input in policy development.

Conclusion

Effective patient care in IBD, as well as in other chronic gastrointestinal diseases, requires a collaborative approach to maximize clinical outcomes. It is an exciting time in our field, with rapidly expanding therapeutic options to treat IBD that have the potential to modify the disease course and prevent long-term complications for patients. However, optimizing the use of these treatments to achieve disease remission is challenging and requires the ability to individualize the timely choice of medications at the right dose for each patient to capture and monitor response. The ability to provide individualized, data driven care is essential to improving the quality of life of our patients, as well as to reducing health care spending over time.

Achieving high-value care is a goal that benefits everyone involved in the health care system. Policies that interfere with the timely treatment of sick patients with the right therapies, optimized to achieve disease remission, hurt the very patients that our health care system exists to serve. We cannot stand by while impediments to treatment result in harm to our patients and worsen clinical outcomes. Collaboratively developing aligned incentives can lead us to patient-centered policies that fulfill a shared purpose to optimize the health of people with chronic digestive diseases.

The authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Dr. Feuerstein is with the Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and is an associate professor of medicine Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Sofia is an assistant professor of medicine with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. Dr. Guha is a professor of medicine at the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition and is codirector of the Center for Interventional Gastroenterology at UTHealth (iGUT) at UT Health Science Center, Houston. Dr. Streett is a clinical professor of medicine, gastroenterology, and hepatology and director of the IBD Education and Advanced IBD Fellowship at Stanford (Calif.) Medicine.

AGA helps break down barriers to CRC screening

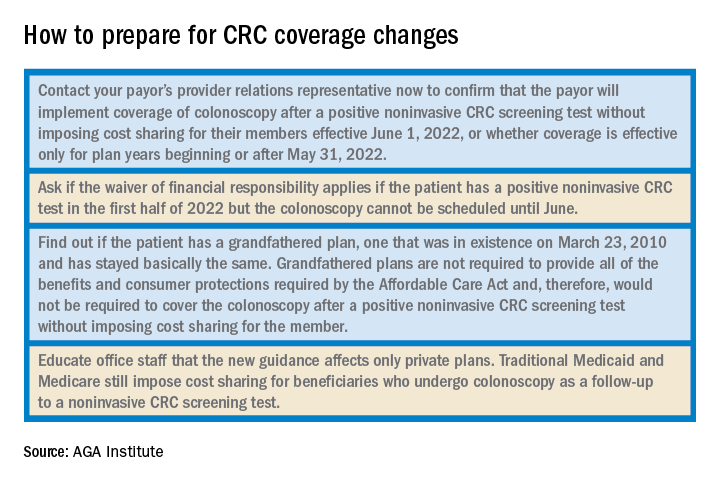

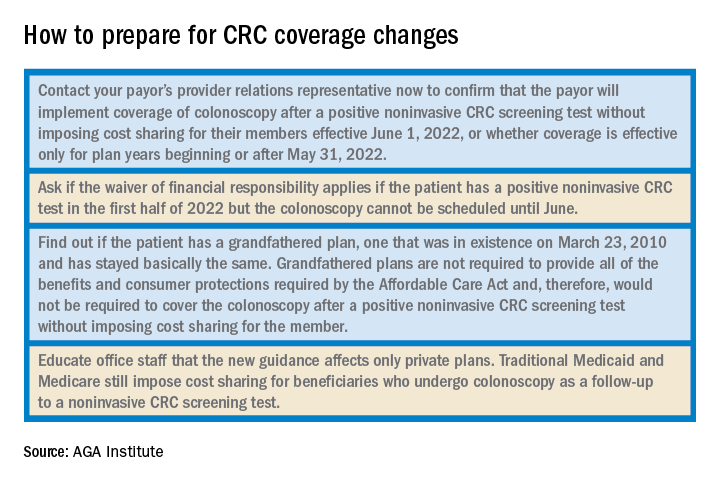

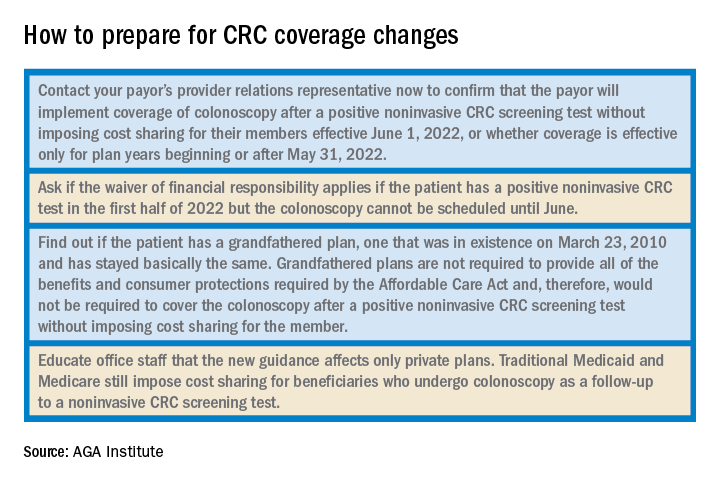

The new year has already marked major progress for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with the implementation of the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which will protect Medicare beneficiaries from an unexpected bill if a polyp is detected and removed during a screening colonoscopy, as well as new guidance from the federal government requiring private insurers to cover colonoscopy as a follow-up to a noninvasive CRC screening test without imposing cost sharing for patients.

The American Gastroenterological Association is strongly committed to reducing the incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer. There is strong evidence that CRC screening is effective, but only 65% of eligible individuals have been screened. A. Mark Fendrick, MD, and colleagues recently found that cost sharing for CRC screening occurred in 48.2% of patients with commercial insurance and 77.9% of patients with Medicare coverage. The elimination of these barriers to CRC screening should improve adherence and reduce the burden of CRC.

As one of AGA President John M. Inadomi’s initiatives, the AGA created the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee in 2021 to develop AGA Position Statements that highlight the continuum of CRC screening and identify barriers, as well as work with stakeholders to eliminate known barriers. Chaired by former AGA President, David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, and with public policy guidance from Kathleen Teixeira, AGA Vice President of Public Policy and Government Affairs at the AGA, the committee identified that, at that time, colonoscopies after positive stool tests had often been considered “diagnostic” and, therefore, were not covered in full the way a preventive screening is required to be covered by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The committee recognized that copays and deductibles are barriers to CRC screening and contribute to health inequity and socio-economic disparities. Noninvasive screening should be considered a part of programs with multiple steps, all of which – including follow-up colonoscopy if the test is positive – should be covered by payers without cost sharing as part of the screening continuum. Further, screening with high-quality colonoscopy should be covered by payers without cost sharing, consistent with the aims of the ACA. The committee recommended that the full cost of screening, including the bowel prep, facility and professional fees, anesthesia, and pathology, should be covered by payers without cost sharing.

Over the past decade, the AGA and other organizations have spent countless hours advocating for closing the gap. In September 2021, Dr. Inadomi and Dr. Lieberman, along with the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network and Fight CRC, met with Assistant Secretary of Labor, Ali Khawar, and representatives from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services and U.S. Department of Treasury to request they direct private health plans to cover colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive CRC screening. In January 2022, guidance from the United States Department of Labor, HHS, and the USDT clarified that private insurance plans must cover follow-up colonoscopies after a positive noninvasive stool test. In the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Affordable Care Act Implementation, Part 51, the departments affirmed that a plan or issuer must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test for colorectal cancer for individuals described in a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation from May 18, 2021. As stated in that USPSTF recommendation, the follow-up colonoscopy is an integral part of the preventive screening without which the screening would not be complete . The follow-up colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test is therefore required to be covered without cost sharing in accordance with the requirements of Public Health Service Act section 2713 and its implementing regulations.

Plans and issuers must provide coverage without cost sharing for plan or policy years beginning on or after May 31, 2022. While this new guidance will expand coverage of follow-up colonoscopies to many more individuals nationwide, including individuals who have coverage through Medicaid expansion, it does not apply to traditional Medicaid and Medicare plans.

The members of the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee includes Dr. Brill and Lieberman, as well as Uri Ladabaum, MD; Larry Kim, MD; Folasade May, MD, PhD, MPhil; Caitlin Murphy, MD; and Richard Wender, MD. Disclosures are on file with the AGA National Office.

Dr. Brill is chief medical officer, Predictive Health, Phoenix. Dr. Lieberman is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as well as a past president of the AGA. Dr. Brill discloses consulting for Accomplish Health, Alimetry, Allara Health, AnX Robotica, Arch Therapeutics, Biotax, Boomerang Medical, Brightline, Calyx, Capsovision, Check Cap, Clexio, Curology, Docbot, Echosens, Endogastric Solutions, evoEndo, Family First, FDNA, Food Marble, Freespira, Gala Therapeutics, Glaukos, gTech Medical, Gynesonics, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Innovative Health Solutions, IronRod Health, Johnson & Johnson, Lantheus, LeMinou, Lumen, Mainstay Medical, MaternaMed, Medtronic, Mightier, Motus GI, OncoSil Medical, Palette Life Sciences, Perry Health, Perspectum, Red Ventures, Reflexion, Respira Labs, Salaso, Smith+Nephew, SonarMD, Stage Zero Life Sciences, Steris, Sword Health, Tabula Rosa Health Care, Ultrasight, Vertos Medical, WL Gore, and holds options/warrants in Accomplish Health, AnX Robotica, Capsovision, Donsini Health, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Restech, Perry Health, StageZero Life Sciences, SonarMD. Dr. Lieberman is a consultant to Geneoscopy.

The new year has already marked major progress for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with the implementation of the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which will protect Medicare beneficiaries from an unexpected bill if a polyp is detected and removed during a screening colonoscopy, as well as new guidance from the federal government requiring private insurers to cover colonoscopy as a follow-up to a noninvasive CRC screening test without imposing cost sharing for patients.

The American Gastroenterological Association is strongly committed to reducing the incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer. There is strong evidence that CRC screening is effective, but only 65% of eligible individuals have been screened. A. Mark Fendrick, MD, and colleagues recently found that cost sharing for CRC screening occurred in 48.2% of patients with commercial insurance and 77.9% of patients with Medicare coverage. The elimination of these barriers to CRC screening should improve adherence and reduce the burden of CRC.

As one of AGA President John M. Inadomi’s initiatives, the AGA created the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee in 2021 to develop AGA Position Statements that highlight the continuum of CRC screening and identify barriers, as well as work with stakeholders to eliminate known barriers. Chaired by former AGA President, David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, and with public policy guidance from Kathleen Teixeira, AGA Vice President of Public Policy and Government Affairs at the AGA, the committee identified that, at that time, colonoscopies after positive stool tests had often been considered “diagnostic” and, therefore, were not covered in full the way a preventive screening is required to be covered by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The committee recognized that copays and deductibles are barriers to CRC screening and contribute to health inequity and socio-economic disparities. Noninvasive screening should be considered a part of programs with multiple steps, all of which – including follow-up colonoscopy if the test is positive – should be covered by payers without cost sharing as part of the screening continuum. Further, screening with high-quality colonoscopy should be covered by payers without cost sharing, consistent with the aims of the ACA. The committee recommended that the full cost of screening, including the bowel prep, facility and professional fees, anesthesia, and pathology, should be covered by payers without cost sharing.

Over the past decade, the AGA and other organizations have spent countless hours advocating for closing the gap. In September 2021, Dr. Inadomi and Dr. Lieberman, along with the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network and Fight CRC, met with Assistant Secretary of Labor, Ali Khawar, and representatives from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services and U.S. Department of Treasury to request they direct private health plans to cover colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive CRC screening. In January 2022, guidance from the United States Department of Labor, HHS, and the USDT clarified that private insurance plans must cover follow-up colonoscopies after a positive noninvasive stool test. In the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Affordable Care Act Implementation, Part 51, the departments affirmed that a plan or issuer must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test for colorectal cancer for individuals described in a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation from May 18, 2021. As stated in that USPSTF recommendation, the follow-up colonoscopy is an integral part of the preventive screening without which the screening would not be complete . The follow-up colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test is therefore required to be covered without cost sharing in accordance with the requirements of Public Health Service Act section 2713 and its implementing regulations.

Plans and issuers must provide coverage without cost sharing for plan or policy years beginning on or after May 31, 2022. While this new guidance will expand coverage of follow-up colonoscopies to many more individuals nationwide, including individuals who have coverage through Medicaid expansion, it does not apply to traditional Medicaid and Medicare plans.

The members of the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee includes Dr. Brill and Lieberman, as well as Uri Ladabaum, MD; Larry Kim, MD; Folasade May, MD, PhD, MPhil; Caitlin Murphy, MD; and Richard Wender, MD. Disclosures are on file with the AGA National Office.

Dr. Brill is chief medical officer, Predictive Health, Phoenix. Dr. Lieberman is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as well as a past president of the AGA. Dr. Brill discloses consulting for Accomplish Health, Alimetry, Allara Health, AnX Robotica, Arch Therapeutics, Biotax, Boomerang Medical, Brightline, Calyx, Capsovision, Check Cap, Clexio, Curology, Docbot, Echosens, Endogastric Solutions, evoEndo, Family First, FDNA, Food Marble, Freespira, Gala Therapeutics, Glaukos, gTech Medical, Gynesonics, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Innovative Health Solutions, IronRod Health, Johnson & Johnson, Lantheus, LeMinou, Lumen, Mainstay Medical, MaternaMed, Medtronic, Mightier, Motus GI, OncoSil Medical, Palette Life Sciences, Perry Health, Perspectum, Red Ventures, Reflexion, Respira Labs, Salaso, Smith+Nephew, SonarMD, Stage Zero Life Sciences, Steris, Sword Health, Tabula Rosa Health Care, Ultrasight, Vertos Medical, WL Gore, and holds options/warrants in Accomplish Health, AnX Robotica, Capsovision, Donsini Health, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Restech, Perry Health, StageZero Life Sciences, SonarMD. Dr. Lieberman is a consultant to Geneoscopy.

The new year has already marked major progress for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with the implementation of the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which will protect Medicare beneficiaries from an unexpected bill if a polyp is detected and removed during a screening colonoscopy, as well as new guidance from the federal government requiring private insurers to cover colonoscopy as a follow-up to a noninvasive CRC screening test without imposing cost sharing for patients.

The American Gastroenterological Association is strongly committed to reducing the incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer. There is strong evidence that CRC screening is effective, but only 65% of eligible individuals have been screened. A. Mark Fendrick, MD, and colleagues recently found that cost sharing for CRC screening occurred in 48.2% of patients with commercial insurance and 77.9% of patients with Medicare coverage. The elimination of these barriers to CRC screening should improve adherence and reduce the burden of CRC.

As one of AGA President John M. Inadomi’s initiatives, the AGA created the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee in 2021 to develop AGA Position Statements that highlight the continuum of CRC screening and identify barriers, as well as work with stakeholders to eliminate known barriers. Chaired by former AGA President, David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, and with public policy guidance from Kathleen Teixeira, AGA Vice President of Public Policy and Government Affairs at the AGA, the committee identified that, at that time, colonoscopies after positive stool tests had often been considered “diagnostic” and, therefore, were not covered in full the way a preventive screening is required to be covered by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The committee recognized that copays and deductibles are barriers to CRC screening and contribute to health inequity and socio-economic disparities. Noninvasive screening should be considered a part of programs with multiple steps, all of which – including follow-up colonoscopy if the test is positive – should be covered by payers without cost sharing as part of the screening continuum. Further, screening with high-quality colonoscopy should be covered by payers without cost sharing, consistent with the aims of the ACA. The committee recommended that the full cost of screening, including the bowel prep, facility and professional fees, anesthesia, and pathology, should be covered by payers without cost sharing.

Over the past decade, the AGA and other organizations have spent countless hours advocating for closing the gap. In September 2021, Dr. Inadomi and Dr. Lieberman, along with the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network and Fight CRC, met with Assistant Secretary of Labor, Ali Khawar, and representatives from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services and U.S. Department of Treasury to request they direct private health plans to cover colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive CRC screening. In January 2022, guidance from the United States Department of Labor, HHS, and the USDT clarified that private insurance plans must cover follow-up colonoscopies after a positive noninvasive stool test. In the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Affordable Care Act Implementation, Part 51, the departments affirmed that a plan or issuer must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test for colorectal cancer for individuals described in a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation from May 18, 2021. As stated in that USPSTF recommendation, the follow-up colonoscopy is an integral part of the preventive screening without which the screening would not be complete . The follow-up colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test is therefore required to be covered without cost sharing in accordance with the requirements of Public Health Service Act section 2713 and its implementing regulations.

Plans and issuers must provide coverage without cost sharing for plan or policy years beginning on or after May 31, 2022. While this new guidance will expand coverage of follow-up colonoscopies to many more individuals nationwide, including individuals who have coverage through Medicaid expansion, it does not apply to traditional Medicaid and Medicare plans.

The members of the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee includes Dr. Brill and Lieberman, as well as Uri Ladabaum, MD; Larry Kim, MD; Folasade May, MD, PhD, MPhil; Caitlin Murphy, MD; and Richard Wender, MD. Disclosures are on file with the AGA National Office.

Dr. Brill is chief medical officer, Predictive Health, Phoenix. Dr. Lieberman is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as well as a past president of the AGA. Dr. Brill discloses consulting for Accomplish Health, Alimetry, Allara Health, AnX Robotica, Arch Therapeutics, Biotax, Boomerang Medical, Brightline, Calyx, Capsovision, Check Cap, Clexio, Curology, Docbot, Echosens, Endogastric Solutions, evoEndo, Family First, FDNA, Food Marble, Freespira, Gala Therapeutics, Glaukos, gTech Medical, Gynesonics, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Innovative Health Solutions, IronRod Health, Johnson & Johnson, Lantheus, LeMinou, Lumen, Mainstay Medical, MaternaMed, Medtronic, Mightier, Motus GI, OncoSil Medical, Palette Life Sciences, Perry Health, Perspectum, Red Ventures, Reflexion, Respira Labs, Salaso, Smith+Nephew, SonarMD, Stage Zero Life Sciences, Steris, Sword Health, Tabula Rosa Health Care, Ultrasight, Vertos Medical, WL Gore, and holds options/warrants in Accomplish Health, AnX Robotica, Capsovision, Donsini Health, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Restech, Perry Health, StageZero Life Sciences, SonarMD. Dr. Lieberman is a consultant to Geneoscopy.

Quality measurement in gastroenterology: A vision for the future

Modern efforts to monitor and improve quality in health care can trace their roots to the early 20th century. At that time, hospitals initiated mechanisms to ensure standard practices for privileging clinicians, reporting medical records and clinical data, and establishing supervised diagnostic facilities. Years later, Avedis Donabedian published “Evaluating the Quality of Medical Care,” which outlined how health care should be measured across three areas – structure, process, and outcome – and became a foundational rubric for assessing quality in medicine.

Over the ensuing decades, with the rise of professional society guidelines and increasing government involvement in the reimbursement of health care, establishing benchmarks and tracking clinical performance has become increasingly important. The passage of the Affordable Care Act subsequently established a formal, legislative mandate for assessing clinical quality tied to reimbursement. Although the context, consequences, and details for reporting have evolved, quality tracking is now firmly entrenched across clinical practice, including gastroenterology. One such mechanism for this is the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), which is a quality payment program (QPP) administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Today, both government and private payers are assessing measurements and improvements of quality to satisfy the Quintuple Aim of achieving better health outcomes, seeking efficient cost of care, improving patient experience, improving provider experience, and enhancing equity through the reduction health inequalities.

As we transition from a fee-based to a value-based care model, several important developments relevant to the practicing gastroenterologist are likely to occur as the broader landscape of quality reporting will continue shifting. This article will outline a vision of the future in quality measurement for gastroenterology.

Gastroenterologists have relatively few specialty-specific measures on which to report. The widespread use of the adenoma detection rate for screening colonoscopy does represent a success in quality improvement because it is easily calculated, is reproducible, and has been consistently associated with clinical outcomes. But the overall measure set is limited to screening colonoscopy and the management of viral hepatitis, meaning large areas of our practice are not included in this set. Developing new metrics related to broader areas of practice will be necessary to address this current shortcoming and increase the impact of quality programs to clinicians. Indeed, a recent environmental scan performed by the Core Quality Measures Collaborative, a public-private coalition of leaders working to facilitate measure alignment, proposed future areas for development, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and medication management.

The American Gastroenterological Association, through its defined process of guideline-to-measure development, has responded by creating metrics for the management of acute pancreatitis, Lynch syndrome testing, and eradicating Helicobacter pylori in the context of gastric intestinal metaplasia; additionally, previously defined measures exist for Barrett’s esophagus and inflammatory bowel disease. Therefore, gastroenterologists can expect to report on an expanding collection of measures in the future.

However, recognizing that not all measures may be equally applicable across populations and acknowledging the importance of risk adjustment, incorporating at least an assessment for risk stratification in their future development is vital. Specifically, social risk factors will need to be accounted for during development in ways that might include risk adjustment or stratification by groups. Increasing data demonstrate that clinician performance can vary by population served and that social determinants of health (SDoH) should be incorporated into an assessment of outcomes. Risk stratification may allow clinicians or practices to report outcomes by group without jeopardy of incurring performance-based penalties. However, the ultimate goal should be reducing inequities and closing care gaps rather than inadvertently lowering the bar for clinicians who primarily treat disenfranchised populations. Eventually, any new measures aiming to be included in a QPP require formal validity testing, which can delay their inclusion in such a set. Yet including stratification in their development will provide a more robust and accurate assessment of quality of care delivered according to one’s catchment and help serve to minimize the effects of SDoH.

Another way that quality measurement may account for a more comprehensive assessment of care delivered is by bundling similarly provided services, even those across multiple specialties. Such a future model is the MIPS Value Pathways, currently under development by CMS. While the exact make-up and reporting structure remains to be determined, a group of related metrics – for example, for colonic health – would likely be grouped together. This model might include an evaluation of a practice’s performance in screening colonoscopy, Lynch testing practices, and inflammatory bowel disease management, which could also be relevant to surgeons, pathologists, and oncologists. This paradigm could serve to increase quality alignment across specialties and reinforce a commitment toward improving care delivery and fulfill a value-based mandate.

Within this framework, though, a shared challenge across specialties exists for the capture and reporting of clinical data. The financial and time costs for quality reporting are well documented, therefore any future vision of quality must address means to ease this reporting burden. Accounting for this would be especially impactful to independent as well as small- to moderate-sized practices, which must provide their own resources for collecting and reporting, with the QPP payment adjustments often insufficient to replace lost revenue or expenses. Some administrative relief has been provided by CMS during the current COVID-19 pandemic, but this focused on allowing select clinicians to avoid reporting rather than addressing the fundamental challenges presented by extracting and documenting quality measures. Moving forward, an increasing emphasis will likely be on the use of artificial intelligence (AI), such as natural language processing, combined with discrete code extraction for tracking performance. While AI has the advantage of a more hands-free approach, such a system would itself require monitoring for performance to avoid unintended consequences.

Ultimately, providing high-quality care and improving patient outcomes are universal goals, though demonstrating this aspiration by reporting on quality metrics can be challenging. Quality measurement, though, is now firmly integrated into the fabric of clinical medicine. In the future, more facets of practice will be measured, patient-level factors and cross specialty reporting will increasingly be emphasized, and administrative burdens will be reduced.

Dr. Leiman is assistant professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., cochair of the Core Quality Measure Collaborative Gastroenterology Workgroup, and chair of the AGA’s Quality Committee. Dr. Freedman is medical director, SE Territory, Aetna/CVS Health and cochair of the Core Quality Measure Collaborative Gastroenterology Workgroup. Dr. Anjou is a practicing clinical gastroenterologist at Connecticut GI, Torrington, and recent member of the AGA Quality Committee. The authors reported no conflicts related to this article.

Modern efforts to monitor and improve quality in health care can trace their roots to the early 20th century. At that time, hospitals initiated mechanisms to ensure standard practices for privileging clinicians, reporting medical records and clinical data, and establishing supervised diagnostic facilities. Years later, Avedis Donabedian published “Evaluating the Quality of Medical Care,” which outlined how health care should be measured across three areas – structure, process, and outcome – and became a foundational rubric for assessing quality in medicine.

Over the ensuing decades, with the rise of professional society guidelines and increasing government involvement in the reimbursement of health care, establishing benchmarks and tracking clinical performance has become increasingly important. The passage of the Affordable Care Act subsequently established a formal, legislative mandate for assessing clinical quality tied to reimbursement. Although the context, consequences, and details for reporting have evolved, quality tracking is now firmly entrenched across clinical practice, including gastroenterology. One such mechanism for this is the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), which is a quality payment program (QPP) administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Today, both government and private payers are assessing measurements and improvements of quality to satisfy the Quintuple Aim of achieving better health outcomes, seeking efficient cost of care, improving patient experience, improving provider experience, and enhancing equity through the reduction health inequalities.

As we transition from a fee-based to a value-based care model, several important developments relevant to the practicing gastroenterologist are likely to occur as the broader landscape of quality reporting will continue shifting. This article will outline a vision of the future in quality measurement for gastroenterology.

Gastroenterologists have relatively few specialty-specific measures on which to report. The widespread use of the adenoma detection rate for screening colonoscopy does represent a success in quality improvement because it is easily calculated, is reproducible, and has been consistently associated with clinical outcomes. But the overall measure set is limited to screening colonoscopy and the management of viral hepatitis, meaning large areas of our practice are not included in this set. Developing new metrics related to broader areas of practice will be necessary to address this current shortcoming and increase the impact of quality programs to clinicians. Indeed, a recent environmental scan performed by the Core Quality Measures Collaborative, a public-private coalition of leaders working to facilitate measure alignment, proposed future areas for development, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and medication management.

The American Gastroenterological Association, through its defined process of guideline-to-measure development, has responded by creating metrics for the management of acute pancreatitis, Lynch syndrome testing, and eradicating Helicobacter pylori in the context of gastric intestinal metaplasia; additionally, previously defined measures exist for Barrett’s esophagus and inflammatory bowel disease. Therefore, gastroenterologists can expect to report on an expanding collection of measures in the future.

However, recognizing that not all measures may be equally applicable across populations and acknowledging the importance of risk adjustment, incorporating at least an assessment for risk stratification in their future development is vital. Specifically, social risk factors will need to be accounted for during development in ways that might include risk adjustment or stratification by groups. Increasing data demonstrate that clinician performance can vary by population served and that social determinants of health (SDoH) should be incorporated into an assessment of outcomes. Risk stratification may allow clinicians or practices to report outcomes by group without jeopardy of incurring performance-based penalties. However, the ultimate goal should be reducing inequities and closing care gaps rather than inadvertently lowering the bar for clinicians who primarily treat disenfranchised populations. Eventually, any new measures aiming to be included in a QPP require formal validity testing, which can delay their inclusion in such a set. Yet including stratification in their development will provide a more robust and accurate assessment of quality of care delivered according to one’s catchment and help serve to minimize the effects of SDoH.

Another way that quality measurement may account for a more comprehensive assessment of care delivered is by bundling similarly provided services, even those across multiple specialties. Such a future model is the MIPS Value Pathways, currently under development by CMS. While the exact make-up and reporting structure remains to be determined, a group of related metrics – for example, for colonic health – would likely be grouped together. This model might include an evaluation of a practice’s performance in screening colonoscopy, Lynch testing practices, and inflammatory bowel disease management, which could also be relevant to surgeons, pathologists, and oncologists. This paradigm could serve to increase quality alignment across specialties and reinforce a commitment toward improving care delivery and fulfill a value-based mandate.

Within this framework, though, a shared challenge across specialties exists for the capture and reporting of clinical data. The financial and time costs for quality reporting are well documented, therefore any future vision of quality must address means to ease this reporting burden. Accounting for this would be especially impactful to independent as well as small- to moderate-sized practices, which must provide their own resources for collecting and reporting, with the QPP payment adjustments often insufficient to replace lost revenue or expenses. Some administrative relief has been provided by CMS during the current COVID-19 pandemic, but this focused on allowing select clinicians to avoid reporting rather than addressing the fundamental challenges presented by extracting and documenting quality measures. Moving forward, an increasing emphasis will likely be on the use of artificial intelligence (AI), such as natural language processing, combined with discrete code extraction for tracking performance. While AI has the advantage of a more hands-free approach, such a system would itself require monitoring for performance to avoid unintended consequences.

Ultimately, providing high-quality care and improving patient outcomes are universal goals, though demonstrating this aspiration by reporting on quality metrics can be challenging. Quality measurement, though, is now firmly integrated into the fabric of clinical medicine. In the future, more facets of practice will be measured, patient-level factors and cross specialty reporting will increasingly be emphasized, and administrative burdens will be reduced.

Dr. Leiman is assistant professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., cochair of the Core Quality Measure Collaborative Gastroenterology Workgroup, and chair of the AGA’s Quality Committee. Dr. Freedman is medical director, SE Territory, Aetna/CVS Health and cochair of the Core Quality Measure Collaborative Gastroenterology Workgroup. Dr. Anjou is a practicing clinical gastroenterologist at Connecticut GI, Torrington, and recent member of the AGA Quality Committee. The authors reported no conflicts related to this article.

Modern efforts to monitor and improve quality in health care can trace their roots to the early 20th century. At that time, hospitals initiated mechanisms to ensure standard practices for privileging clinicians, reporting medical records and clinical data, and establishing supervised diagnostic facilities. Years later, Avedis Donabedian published “Evaluating the Quality of Medical Care,” which outlined how health care should be measured across three areas – structure, process, and outcome – and became a foundational rubric for assessing quality in medicine.

Over the ensuing decades, with the rise of professional society guidelines and increasing government involvement in the reimbursement of health care, establishing benchmarks and tracking clinical performance has become increasingly important. The passage of the Affordable Care Act subsequently established a formal, legislative mandate for assessing clinical quality tied to reimbursement. Although the context, consequences, and details for reporting have evolved, quality tracking is now firmly entrenched across clinical practice, including gastroenterology. One such mechanism for this is the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), which is a quality payment program (QPP) administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Today, both government and private payers are assessing measurements and improvements of quality to satisfy the Quintuple Aim of achieving better health outcomes, seeking efficient cost of care, improving patient experience, improving provider experience, and enhancing equity through the reduction health inequalities.

As we transition from a fee-based to a value-based care model, several important developments relevant to the practicing gastroenterologist are likely to occur as the broader landscape of quality reporting will continue shifting. This article will outline a vision of the future in quality measurement for gastroenterology.

Gastroenterologists have relatively few specialty-specific measures on which to report. The widespread use of the adenoma detection rate for screening colonoscopy does represent a success in quality improvement because it is easily calculated, is reproducible, and has been consistently associated with clinical outcomes. But the overall measure set is limited to screening colonoscopy and the management of viral hepatitis, meaning large areas of our practice are not included in this set. Developing new metrics related to broader areas of practice will be necessary to address this current shortcoming and increase the impact of quality programs to clinicians. Indeed, a recent environmental scan performed by the Core Quality Measures Collaborative, a public-private coalition of leaders working to facilitate measure alignment, proposed future areas for development, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and medication management.

The American Gastroenterological Association, through its defined process of guideline-to-measure development, has responded by creating metrics for the management of acute pancreatitis, Lynch syndrome testing, and eradicating Helicobacter pylori in the context of gastric intestinal metaplasia; additionally, previously defined measures exist for Barrett’s esophagus and inflammatory bowel disease. Therefore, gastroenterologists can expect to report on an expanding collection of measures in the future.

However, recognizing that not all measures may be equally applicable across populations and acknowledging the importance of risk adjustment, incorporating at least an assessment for risk stratification in their future development is vital. Specifically, social risk factors will need to be accounted for during development in ways that might include risk adjustment or stratification by groups. Increasing data demonstrate that clinician performance can vary by population served and that social determinants of health (SDoH) should be incorporated into an assessment of outcomes. Risk stratification may allow clinicians or practices to report outcomes by group without jeopardy of incurring performance-based penalties. However, the ultimate goal should be reducing inequities and closing care gaps rather than inadvertently lowering the bar for clinicians who primarily treat disenfranchised populations. Eventually, any new measures aiming to be included in a QPP require formal validity testing, which can delay their inclusion in such a set. Yet including stratification in their development will provide a more robust and accurate assessment of quality of care delivered according to one’s catchment and help serve to minimize the effects of SDoH.

Another way that quality measurement may account for a more comprehensive assessment of care delivered is by bundling similarly provided services, even those across multiple specialties. Such a future model is the MIPS Value Pathways, currently under development by CMS. While the exact make-up and reporting structure remains to be determined, a group of related metrics – for example, for colonic health – would likely be grouped together. This model might include an evaluation of a practice’s performance in screening colonoscopy, Lynch testing practices, and inflammatory bowel disease management, which could also be relevant to surgeons, pathologists, and oncologists. This paradigm could serve to increase quality alignment across specialties and reinforce a commitment toward improving care delivery and fulfill a value-based mandate.

Within this framework, though, a shared challenge across specialties exists for the capture and reporting of clinical data. The financial and time costs for quality reporting are well documented, therefore any future vision of quality must address means to ease this reporting burden. Accounting for this would be especially impactful to independent as well as small- to moderate-sized practices, which must provide their own resources for collecting and reporting, with the QPP payment adjustments often insufficient to replace lost revenue or expenses. Some administrative relief has been provided by CMS during the current COVID-19 pandemic, but this focused on allowing select clinicians to avoid reporting rather than addressing the fundamental challenges presented by extracting and documenting quality measures. Moving forward, an increasing emphasis will likely be on the use of artificial intelligence (AI), such as natural language processing, combined with discrete code extraction for tracking performance. While AI has the advantage of a more hands-free approach, such a system would itself require monitoring for performance to avoid unintended consequences.

Ultimately, providing high-quality care and improving patient outcomes are universal goals, though demonstrating this aspiration by reporting on quality metrics can be challenging. Quality measurement, though, is now firmly integrated into the fabric of clinical medicine. In the future, more facets of practice will be measured, patient-level factors and cross specialty reporting will increasingly be emphasized, and administrative burdens will be reduced.

Dr. Leiman is assistant professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., cochair of the Core Quality Measure Collaborative Gastroenterology Workgroup, and chair of the AGA’s Quality Committee. Dr. Freedman is medical director, SE Territory, Aetna/CVS Health and cochair of the Core Quality Measure Collaborative Gastroenterology Workgroup. Dr. Anjou is a practicing clinical gastroenterologist at Connecticut GI, Torrington, and recent member of the AGA Quality Committee. The authors reported no conflicts related to this article.

Improving quality and return-on-investment: Provider onboarding

Physician and advanced practice provider (APP) (collectively, “provider”) onboarding into health care delivery settings requires careful planning and systematic integration. Assimilation into health care settings and cultures necessitates more than a 1- or 2-day orientation. Rather, an intentional, longitudinal onboarding program (starting with orientation) needs to be designed to assimilate providers into the unique culture of a medical practice.

Establishing mutual expectations

Communication concerning mutual expectations is a vital component of the agreement between provider and practice. Items that should be included in provider onboarding (likely addressed in either the practice visit or amplified in a contract) include the following:

- Committees: Committee orientation should include a discussion of provider preferences/expectations and why getting the new provider involved in the business of the practice is a priority of the group.

- Operations: Key clinical operations details should be reviewed with the incoming provider and reinforced through follow-up discussions with a physician mentor/coach (for example, call distribution; role of the senior nonclinical leadership team/accountants, fellow practice/group partners, and IT support; role definitions and expectations for duties, transitioning call, and EHR charting; revenue-sharing; supplies/preferences/adaptability to scope type).

- Interests: Specific provider interests (for example, clinical research, infusion, hemorrhoidal banding, weight loss/nutrition, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel disease, pathology) and productivity expectations (for example, number of procedures, number of new and return patient visits per day) should be communicated.

- Miscellaneous: Discussion about marketing the practice, importance of growing satellite programs and nuance of major referral groups to the practice are also key components of the assimilation process.

Leadership self-awareness and cultural alignment

Leadership self-awareness is a key element of provider onboarding. Physicians and APPs are trained to think independently and may be challenged to share decision-making and rely on others. The following are some no-cost self-assessment and awareness resources:

- Myers-Briggs Personality Profile Preferences:

- VIA Strengths:

- VARK Analysis:

Cultural alignment is also a critical consideration to ensure orderly assimilation into the practice/health care setting and with stakeholders. A shared commitment to embed a culture with shared values has relevance to merging cultures – not only when organizations come together – but with individuals as well. Time spent developing a better understanding of the customs, culture and traditions of the practice will be helpful if a practice must change its trajectory based on meeting an unmovable obstruction (for example, market forces requiring practice consolidation).

Improved quality

Transitioning a new provider into an existing practice culture can have a ripple effect on support staff and patient satisfaction and is, therefore, an important consideration in provider onboarding. Written standards, procedures, expectations, and practices are always advisable when possible. Attention to the demographics of the recruited physician is also important with shifts in interests and priorities from a practice. Millennials will constitute most of the workforce by 2025 and arrive with a mindset that the tenure in a role will be shorter than providers before them. Accordingly, the intentionality of the relationship is critical for successful bonding.

If current physician leaders want to achieve simultaneous succession planning and maintain the legacy of a patient-centric and resilient practice, these leaders must consider bridging the “cultural knowledge acumen gap.” James S. Hernandez, MD, MS, FCAP, and colleagues suggest a “connector” role between new and experienced providers. Reverse mentoring/distance/reciprocal mentoring is also mentioned as a two-way learning process between mentor and mentee.

Process structure considerations

Each new hire affects the culture of the practice. Best practices for the onboarding and orientation process should be followed. A written project master list with a timeline for completion of onboarding tasks with responsible and accountable persons, target dates for completion, and measurement should be established. Establishing mutual expectations up front can help practices tailor committee roles and clinical responsibilities to maximize provider engagement and longevity. A robust onboarding process may take up to 2 years depending on the size of the practice and the complexity of its structure and associated duties.

Desired outcomes

The desired outcome of the onboarding process is a satisfied provider whose passion and enthusiasm for quality patient care is demonstrated objectively through excellent performance on clinical quality measures and metrics of patient and referral source satisfaction.

Periodic reviews of how the onboarding process is progressing should be undertaken. These reviews can be modeled after the After-Action Review (AAR) process used in the military for measuring progress. Simply stated, what items went well with onboarding and why? What items did not go well with onboarding and why not? (Consider something like the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ “5 Whys” assessment to determine root cause for items that need correction.) What elements of the onboarding process could be further improved? Using a Delphi method during the AAR session is an excellent way for the group to hear from all participants ranging from senior partners to recently recruited providers.

Conclusion

Medical practices must recognize that assimilating a new provider into the practice through a robust onboarding process is not lost effort but rather a force multiplier. Effective provider onboarding gives the incoming provider a sense of purpose and resolve, which results in optimized clinical productivity and engagement because the new provider is invested in the future of the practice. Once successfully onboarded and integrated into the practice, new providers need to understand that the work effort invested in their onboarding comes with a “pay it forward” obligation for the next provider recruited by the group. Group members also need to realize that the baseline is always changing–the provider onboarding process needs to continually evolve and adapt as the practice changes and new providers are hired.

Mr. Rudnick is a visiting professor and program director healthcare quality, innovation, and strategy at St Thomas University, Miami. Mr. Turner is regional vice president for the Midatlantic market of Covenant Physician Partners.

References

“Best practices for onboarding physicians.” The Rheumatologist. 2019 Sep 17. Accessed 2021 Sep 6. https://www.the-rheumatologist.org/article/best-practices-for-onboarding-new-physicians/

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Five Whys Tool for Root Cause Analysis: QAPI. 2021. Accessed 2021 Sep 6. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/qapi/downloads/fivewhys.pdf.

DeIuliis ET, Saylor E. Open J Occup Ther. 2021;9(1):1-13.

Hernandez JS et al. “Discussion: Mentoring millennials for future leadership.” Physician Leadership Journal. 2018 May 14. Accessed 2021 Sep 6. https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/discussion-mentoring-millennials-future-leadership

Moore L et al. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 Jun;78(6):1168-75..

Klein CJ et al. West J Nurs Res. 2021 Feb;43(2):105-114.

Weinburger T, Gordon J. Health Prog. Nov-Dec 2013;94(6):76-9.

Wentlandt K et al. Healthc Q. 2016;18(4):36-41.

Physician and advanced practice provider (APP) (collectively, “provider”) onboarding into health care delivery settings requires careful planning and systematic integration. Assimilation into health care settings and cultures necessitates more than a 1- or 2-day orientation. Rather, an intentional, longitudinal onboarding program (starting with orientation) needs to be designed to assimilate providers into the unique culture of a medical practice.

Establishing mutual expectations

Communication concerning mutual expectations is a vital component of the agreement between provider and practice. Items that should be included in provider onboarding (likely addressed in either the practice visit or amplified in a contract) include the following:

- Committees: Committee orientation should include a discussion of provider preferences/expectations and why getting the new provider involved in the business of the practice is a priority of the group.

- Operations: Key clinical operations details should be reviewed with the incoming provider and reinforced through follow-up discussions with a physician mentor/coach (for example, call distribution; role of the senior nonclinical leadership team/accountants, fellow practice/group partners, and IT support; role definitions and expectations for duties, transitioning call, and EHR charting; revenue-sharing; supplies/preferences/adaptability to scope type).

- Interests: Specific provider interests (for example, clinical research, infusion, hemorrhoidal banding, weight loss/nutrition, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel disease, pathology) and productivity expectations (for example, number of procedures, number of new and return patient visits per day) should be communicated.

- Miscellaneous: Discussion about marketing the practice, importance of growing satellite programs and nuance of major referral groups to the practice are also key components of the assimilation process.

Leadership self-awareness and cultural alignment

Leadership self-awareness is a key element of provider onboarding. Physicians and APPs are trained to think independently and may be challenged to share decision-making and rely on others. The following are some no-cost self-assessment and awareness resources:

- Myers-Briggs Personality Profile Preferences:

- VIA Strengths:

- VARK Analysis:

Cultural alignment is also a critical consideration to ensure orderly assimilation into the practice/health care setting and with stakeholders. A shared commitment to embed a culture with shared values has relevance to merging cultures – not only when organizations come together – but with individuals as well. Time spent developing a better understanding of the customs, culture and traditions of the practice will be helpful if a practice must change its trajectory based on meeting an unmovable obstruction (for example, market forces requiring practice consolidation).

Improved quality

Transitioning a new provider into an existing practice culture can have a ripple effect on support staff and patient satisfaction and is, therefore, an important consideration in provider onboarding. Written standards, procedures, expectations, and practices are always advisable when possible. Attention to the demographics of the recruited physician is also important with shifts in interests and priorities from a practice. Millennials will constitute most of the workforce by 2025 and arrive with a mindset that the tenure in a role will be shorter than providers before them. Accordingly, the intentionality of the relationship is critical for successful bonding.

If current physician leaders want to achieve simultaneous succession planning and maintain the legacy of a patient-centric and resilient practice, these leaders must consider bridging the “cultural knowledge acumen gap.” James S. Hernandez, MD, MS, FCAP, and colleagues suggest a “connector” role between new and experienced providers. Reverse mentoring/distance/reciprocal mentoring is also mentioned as a two-way learning process between mentor and mentee.

Process structure considerations

Each new hire affects the culture of the practice. Best practices for the onboarding and orientation process should be followed. A written project master list with a timeline for completion of onboarding tasks with responsible and accountable persons, target dates for completion, and measurement should be established. Establishing mutual expectations up front can help practices tailor committee roles and clinical responsibilities to maximize provider engagement and longevity. A robust onboarding process may take up to 2 years depending on the size of the practice and the complexity of its structure and associated duties.

Desired outcomes

The desired outcome of the onboarding process is a satisfied provider whose passion and enthusiasm for quality patient care is demonstrated objectively through excellent performance on clinical quality measures and metrics of patient and referral source satisfaction.

Periodic reviews of how the onboarding process is progressing should be undertaken. These reviews can be modeled after the After-Action Review (AAR) process used in the military for measuring progress. Simply stated, what items went well with onboarding and why? What items did not go well with onboarding and why not? (Consider something like the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ “5 Whys” assessment to determine root cause for items that need correction.) What elements of the onboarding process could be further improved? Using a Delphi method during the AAR session is an excellent way for the group to hear from all participants ranging from senior partners to recently recruited providers.

Conclusion

Medical practices must recognize that assimilating a new provider into the practice through a robust onboarding process is not lost effort but rather a force multiplier. Effective provider onboarding gives the incoming provider a sense of purpose and resolve, which results in optimized clinical productivity and engagement because the new provider is invested in the future of the practice. Once successfully onboarded and integrated into the practice, new providers need to understand that the work effort invested in their onboarding comes with a “pay it forward” obligation for the next provider recruited by the group. Group members also need to realize that the baseline is always changing–the provider onboarding process needs to continually evolve and adapt as the practice changes and new providers are hired.

Mr. Rudnick is a visiting professor and program director healthcare quality, innovation, and strategy at St Thomas University, Miami. Mr. Turner is regional vice president for the Midatlantic market of Covenant Physician Partners.

References

“Best practices for onboarding physicians.” The Rheumatologist. 2019 Sep 17. Accessed 2021 Sep 6. https://www.the-rheumatologist.org/article/best-practices-for-onboarding-new-physicians/

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Five Whys Tool for Root Cause Analysis: QAPI. 2021. Accessed 2021 Sep 6. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/qapi/downloads/fivewhys.pdf.

DeIuliis ET, Saylor E. Open J Occup Ther. 2021;9(1):1-13.

Hernandez JS et al. “Discussion: Mentoring millennials for future leadership.” Physician Leadership Journal. 2018 May 14. Accessed 2021 Sep 6. https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/discussion-mentoring-millennials-future-leadership

Moore L et al. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 Jun;78(6):1168-75..

Klein CJ et al. West J Nurs Res. 2021 Feb;43(2):105-114.

Weinburger T, Gordon J. Health Prog. Nov-Dec 2013;94(6):76-9.

Wentlandt K et al. Healthc Q. 2016;18(4):36-41.