User login

Caribbean itch

A 25-year-old man came to the office in July after awakening with a pruritic rash on his chest, back, and abdomen. He reported feeling feverish with chills and malaise, but had no symptoms of respiratory distress and his vital signs were normal. He mentioned that he had gone snorkeling in the Caribbean the previous day, but did not remember being stung by any marine life. He said he was wearing swimming trunks and a t-shirt while in the ocean.

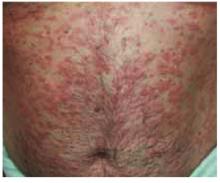

The patient had a diffuse erythematous maculopapular rash on his neck, chest, back, abdomen, shoulders, and axillae (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

FIGURE 1

Rash on abdomen

FIGURE 2

Macules

What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Listen to local beach reports and observe posted beach messages in affected areas.

- Avoid ocean activities in areas where cases have been reported, especially during the peak season, April through July.

- Avoid wearing t-shirts while swimming. Women should consider wearing 2-piece bathing suits.These measures decrease the surface area over which larvae can be trapped. (Of course, swimmers should use potent sunscreens and carefully limit sun exposure to avoid sunburns when more skin is exposed to the sun. Some evidence suggests that the use of a sunscreen may actually protect skin from penetration by the nematocysts.)8

- Wetsuits with restrictive cuffs may be of benefit when surfing or diving.

- When swimming in areas where recent cases have occurred, change swimwear quickly after exiting the water. Do not shower with fresh water while still wearing the suit, because this may cause nematocysts trapped inside to discharge.Wash swimwear with detergent and heat-dry before wearing again. Air-dried nematocysts may still be able to fire.4,8

Diagnosis: Seabather’s eruption

Seabather’s eruption is a pruritic dermatitis that occurs predominantly on areas covered by a bathing suit or shirt after swimming in saltwater. Cases have been reported in Florida, Bermuda, the Caribbean, and as far north as Long Island, New York.

Larvae of members of the phylum Cnidaria are believed to be the cause of this dermatitis.1,2 Cnidaria include hydrozoans (fire coral and Portuguese man-of-war), scyphozoans (true jellyfish), and anthozoans (sea anemones). The condition is sometimes called sea lice, although the organisms have no relationship to lice.

All Cnidaria have microscopic envenomation capsules called nematocysts. Each capsule contains a folded, eversible tubule containing a variety of toxins. Skin contact or chemical stimulation of the triggering apparatus leads to a build-up of hydrostatic force, resulting in eversion of the tubule. Toxins pass across the tubule membrane and are deposited into the skin.

Clinical Course

Onset of seabather’s eruption generally occurs within a few minutes to several hours after the swimmer leaves the water. A pruritic maculopapular rash, occasionally with urticaria, spreads across the skin of the chest, abdomen, neck, axillae, and the flexor surfaces of the arms and legs. The rash may be accompanied by systemic symptoms of malaise, headache, fever, chills, nausea, and vomiting. The dermatitis often lasts 3 to 7 days, but more severe reactions can last up to 6 weeks.3

Are immunological mechanisms responsible?

Tomchik et al4 observed several cases of secondary eruptions that occurred 5 to 10 days after initial exposure. They also reported cases in which urticarial lesions developed 3 weeks after onset of illness, following a disease-free interval during which there was no re-exposure to ocean water. The lesions were seen in the same areas as the initial eruption.

This suggests that immunological mechanisms are responsible for the various clinical courses observed, which would explain the lack of symptoms immediately after exposure, delayed onset of the dermatitis, urticaria among sensitized individuals, and the ability of steroids to suppress the reaction.

A prospective cohort study of cases in Palm Beach County, Florida, concluded that persons with a history of exposure to the condition, children, and surfers were at greatest risk for seabather’s eruption.5

Culprit: the thimble jellyfish

The cause of seabather’s eruption in South Florida and the Caribbean has been identified as the larvae of Linuche unguiculata, or the thimble jellyfish. The adult Linuche (Figure 3) measure 5 mm to 20 mm. They breed between March and September, and the larvae measure about 0.5 mm in diameter, making them invisible to the naked eye.4

These larvae are washed toward the shore by high tides or strong winds. They are small enough to pass through the weave of most swimwear, becoming trapped against the skin. Pressure applied to the skin or changes in osmotic pressure—by evaporation of seawater or showering in fresh water—cause the larvae to discharge their toxin into the skin.6

In a study of cases of seabather’s eruption in the Mexican Caribbean, Segura-Puertas et al7 found that all 3 swimming stages of Linuche (ephyrae, medusae, and larvae) to cause the eruption.

Treatment: antihistamines, topical steroids

Seabather’s eruption can be treated with sedating or nonsedating antihistamines (level of evidence [LOE]=5). While sedating antihistamines may be more antipruritic and less expensive, they should be used with caution if sedation may pose a danger to the patient.

Topical steroids, such as hydrocortisone, may be beneficial. Systemic steroids are reserved for only the most severe reactions. Comfort measures, such as oatmeal baths, may provide some relief of the itching (LOE=5).4

FIGURE 3

Thimble jellyfish

1. Habif TB. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 3rd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby–Year Book; 1996;486-494.

2. Basler RSW, Basler GC, Palmer AH, Garcia MA. Special skin symptoms seen in swimmers. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:299-305.

3. Freudenthal AR, Joseph PR. Seabather’s eruption. N Engl J Med 1993;329:542-544.

4. Tomchik RS, Russell MT, Szmant AM, Black NA. Clinical perspectives on seabather’s eruption, also known as “sea lice.” JAMA 1993;269:1669-1672.

5. Kumar S, Hlady WG, Malecki JM. Risk factors for seabather’s eruption: a prospective cohort study. Public Health Rep 1997;112:59-62.

6. MacSween RM, Williams HC. Lesson of the week: seabather’s eruption-a case of Caribbean itch. Br Med J 1996;312:957-958.

7. Segura-Puertas L, Ramos ME, Aramburo C, Heimer De La Cotera EP, Burnett JW. One Linuche mystery solved: all 3 stages of the coronate scyphomedusa Linuche unguiculata cause seabather’s eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:624-628.

8. Russell MT, Tomchik RS. Clinical articles seabather’s eruption or “sea lice”: New findings and clinical implications [Florida Atlantic University Web site].1995. Available at: www.fau.edu/safe/sea-lice.html. Accessed on July 1, 2003.

A 25-year-old man came to the office in July after awakening with a pruritic rash on his chest, back, and abdomen. He reported feeling feverish with chills and malaise, but had no symptoms of respiratory distress and his vital signs were normal. He mentioned that he had gone snorkeling in the Caribbean the previous day, but did not remember being stung by any marine life. He said he was wearing swimming trunks and a t-shirt while in the ocean.

The patient had a diffuse erythematous maculopapular rash on his neck, chest, back, abdomen, shoulders, and axillae (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

FIGURE 1

Rash on abdomen

FIGURE 2

Macules

What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Listen to local beach reports and observe posted beach messages in affected areas.

- Avoid ocean activities in areas where cases have been reported, especially during the peak season, April through July.

- Avoid wearing t-shirts while swimming. Women should consider wearing 2-piece bathing suits.These measures decrease the surface area over which larvae can be trapped. (Of course, swimmers should use potent sunscreens and carefully limit sun exposure to avoid sunburns when more skin is exposed to the sun. Some evidence suggests that the use of a sunscreen may actually protect skin from penetration by the nematocysts.)8

- Wetsuits with restrictive cuffs may be of benefit when surfing or diving.

- When swimming in areas where recent cases have occurred, change swimwear quickly after exiting the water. Do not shower with fresh water while still wearing the suit, because this may cause nematocysts trapped inside to discharge.Wash swimwear with detergent and heat-dry before wearing again. Air-dried nematocysts may still be able to fire.4,8

Diagnosis: Seabather’s eruption

Seabather’s eruption is a pruritic dermatitis that occurs predominantly on areas covered by a bathing suit or shirt after swimming in saltwater. Cases have been reported in Florida, Bermuda, the Caribbean, and as far north as Long Island, New York.

Larvae of members of the phylum Cnidaria are believed to be the cause of this dermatitis.1,2 Cnidaria include hydrozoans (fire coral and Portuguese man-of-war), scyphozoans (true jellyfish), and anthozoans (sea anemones). The condition is sometimes called sea lice, although the organisms have no relationship to lice.

All Cnidaria have microscopic envenomation capsules called nematocysts. Each capsule contains a folded, eversible tubule containing a variety of toxins. Skin contact or chemical stimulation of the triggering apparatus leads to a build-up of hydrostatic force, resulting in eversion of the tubule. Toxins pass across the tubule membrane and are deposited into the skin.

Clinical Course

Onset of seabather’s eruption generally occurs within a few minutes to several hours after the swimmer leaves the water. A pruritic maculopapular rash, occasionally with urticaria, spreads across the skin of the chest, abdomen, neck, axillae, and the flexor surfaces of the arms and legs. The rash may be accompanied by systemic symptoms of malaise, headache, fever, chills, nausea, and vomiting. The dermatitis often lasts 3 to 7 days, but more severe reactions can last up to 6 weeks.3

Are immunological mechanisms responsible?

Tomchik et al4 observed several cases of secondary eruptions that occurred 5 to 10 days after initial exposure. They also reported cases in which urticarial lesions developed 3 weeks after onset of illness, following a disease-free interval during which there was no re-exposure to ocean water. The lesions were seen in the same areas as the initial eruption.

This suggests that immunological mechanisms are responsible for the various clinical courses observed, which would explain the lack of symptoms immediately after exposure, delayed onset of the dermatitis, urticaria among sensitized individuals, and the ability of steroids to suppress the reaction.

A prospective cohort study of cases in Palm Beach County, Florida, concluded that persons with a history of exposure to the condition, children, and surfers were at greatest risk for seabather’s eruption.5

Culprit: the thimble jellyfish

The cause of seabather’s eruption in South Florida and the Caribbean has been identified as the larvae of Linuche unguiculata, or the thimble jellyfish. The adult Linuche (Figure 3) measure 5 mm to 20 mm. They breed between March and September, and the larvae measure about 0.5 mm in diameter, making them invisible to the naked eye.4

These larvae are washed toward the shore by high tides or strong winds. They are small enough to pass through the weave of most swimwear, becoming trapped against the skin. Pressure applied to the skin or changes in osmotic pressure—by evaporation of seawater or showering in fresh water—cause the larvae to discharge their toxin into the skin.6

In a study of cases of seabather’s eruption in the Mexican Caribbean, Segura-Puertas et al7 found that all 3 swimming stages of Linuche (ephyrae, medusae, and larvae) to cause the eruption.

Treatment: antihistamines, topical steroids

Seabather’s eruption can be treated with sedating or nonsedating antihistamines (level of evidence [LOE]=5). While sedating antihistamines may be more antipruritic and less expensive, they should be used with caution if sedation may pose a danger to the patient.

Topical steroids, such as hydrocortisone, may be beneficial. Systemic steroids are reserved for only the most severe reactions. Comfort measures, such as oatmeal baths, may provide some relief of the itching (LOE=5).4

FIGURE 3

Thimble jellyfish

A 25-year-old man came to the office in July after awakening with a pruritic rash on his chest, back, and abdomen. He reported feeling feverish with chills and malaise, but had no symptoms of respiratory distress and his vital signs were normal. He mentioned that he had gone snorkeling in the Caribbean the previous day, but did not remember being stung by any marine life. He said he was wearing swimming trunks and a t-shirt while in the ocean.

The patient had a diffuse erythematous maculopapular rash on his neck, chest, back, abdomen, shoulders, and axillae (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

FIGURE 1

Rash on abdomen

FIGURE 2

Macules

What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Listen to local beach reports and observe posted beach messages in affected areas.

- Avoid ocean activities in areas where cases have been reported, especially during the peak season, April through July.

- Avoid wearing t-shirts while swimming. Women should consider wearing 2-piece bathing suits.These measures decrease the surface area over which larvae can be trapped. (Of course, swimmers should use potent sunscreens and carefully limit sun exposure to avoid sunburns when more skin is exposed to the sun. Some evidence suggests that the use of a sunscreen may actually protect skin from penetration by the nematocysts.)8

- Wetsuits with restrictive cuffs may be of benefit when surfing or diving.

- When swimming in areas where recent cases have occurred, change swimwear quickly after exiting the water. Do not shower with fresh water while still wearing the suit, because this may cause nematocysts trapped inside to discharge.Wash swimwear with detergent and heat-dry before wearing again. Air-dried nematocysts may still be able to fire.4,8

Diagnosis: Seabather’s eruption

Seabather’s eruption is a pruritic dermatitis that occurs predominantly on areas covered by a bathing suit or shirt after swimming in saltwater. Cases have been reported in Florida, Bermuda, the Caribbean, and as far north as Long Island, New York.

Larvae of members of the phylum Cnidaria are believed to be the cause of this dermatitis.1,2 Cnidaria include hydrozoans (fire coral and Portuguese man-of-war), scyphozoans (true jellyfish), and anthozoans (sea anemones). The condition is sometimes called sea lice, although the organisms have no relationship to lice.

All Cnidaria have microscopic envenomation capsules called nematocysts. Each capsule contains a folded, eversible tubule containing a variety of toxins. Skin contact or chemical stimulation of the triggering apparatus leads to a build-up of hydrostatic force, resulting in eversion of the tubule. Toxins pass across the tubule membrane and are deposited into the skin.

Clinical Course

Onset of seabather’s eruption generally occurs within a few minutes to several hours after the swimmer leaves the water. A pruritic maculopapular rash, occasionally with urticaria, spreads across the skin of the chest, abdomen, neck, axillae, and the flexor surfaces of the arms and legs. The rash may be accompanied by systemic symptoms of malaise, headache, fever, chills, nausea, and vomiting. The dermatitis often lasts 3 to 7 days, but more severe reactions can last up to 6 weeks.3

Are immunological mechanisms responsible?

Tomchik et al4 observed several cases of secondary eruptions that occurred 5 to 10 days after initial exposure. They also reported cases in which urticarial lesions developed 3 weeks after onset of illness, following a disease-free interval during which there was no re-exposure to ocean water. The lesions were seen in the same areas as the initial eruption.

This suggests that immunological mechanisms are responsible for the various clinical courses observed, which would explain the lack of symptoms immediately after exposure, delayed onset of the dermatitis, urticaria among sensitized individuals, and the ability of steroids to suppress the reaction.

A prospective cohort study of cases in Palm Beach County, Florida, concluded that persons with a history of exposure to the condition, children, and surfers were at greatest risk for seabather’s eruption.5

Culprit: the thimble jellyfish

The cause of seabather’s eruption in South Florida and the Caribbean has been identified as the larvae of Linuche unguiculata, or the thimble jellyfish. The adult Linuche (Figure 3) measure 5 mm to 20 mm. They breed between March and September, and the larvae measure about 0.5 mm in diameter, making them invisible to the naked eye.4

These larvae are washed toward the shore by high tides or strong winds. They are small enough to pass through the weave of most swimwear, becoming trapped against the skin. Pressure applied to the skin or changes in osmotic pressure—by evaporation of seawater or showering in fresh water—cause the larvae to discharge their toxin into the skin.6

In a study of cases of seabather’s eruption in the Mexican Caribbean, Segura-Puertas et al7 found that all 3 swimming stages of Linuche (ephyrae, medusae, and larvae) to cause the eruption.

Treatment: antihistamines, topical steroids

Seabather’s eruption can be treated with sedating or nonsedating antihistamines (level of evidence [LOE]=5). While sedating antihistamines may be more antipruritic and less expensive, they should be used with caution if sedation may pose a danger to the patient.

Topical steroids, such as hydrocortisone, may be beneficial. Systemic steroids are reserved for only the most severe reactions. Comfort measures, such as oatmeal baths, may provide some relief of the itching (LOE=5).4

FIGURE 3

Thimble jellyfish

1. Habif TB. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 3rd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby–Year Book; 1996;486-494.

2. Basler RSW, Basler GC, Palmer AH, Garcia MA. Special skin symptoms seen in swimmers. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:299-305.

3. Freudenthal AR, Joseph PR. Seabather’s eruption. N Engl J Med 1993;329:542-544.

4. Tomchik RS, Russell MT, Szmant AM, Black NA. Clinical perspectives on seabather’s eruption, also known as “sea lice.” JAMA 1993;269:1669-1672.

5. Kumar S, Hlady WG, Malecki JM. Risk factors for seabather’s eruption: a prospective cohort study. Public Health Rep 1997;112:59-62.

6. MacSween RM, Williams HC. Lesson of the week: seabather’s eruption-a case of Caribbean itch. Br Med J 1996;312:957-958.

7. Segura-Puertas L, Ramos ME, Aramburo C, Heimer De La Cotera EP, Burnett JW. One Linuche mystery solved: all 3 stages of the coronate scyphomedusa Linuche unguiculata cause seabather’s eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:624-628.

8. Russell MT, Tomchik RS. Clinical articles seabather’s eruption or “sea lice”: New findings and clinical implications [Florida Atlantic University Web site].1995. Available at: www.fau.edu/safe/sea-lice.html. Accessed on July 1, 2003.

1. Habif TB. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 3rd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby–Year Book; 1996;486-494.

2. Basler RSW, Basler GC, Palmer AH, Garcia MA. Special skin symptoms seen in swimmers. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:299-305.

3. Freudenthal AR, Joseph PR. Seabather’s eruption. N Engl J Med 1993;329:542-544.

4. Tomchik RS, Russell MT, Szmant AM, Black NA. Clinical perspectives on seabather’s eruption, also known as “sea lice.” JAMA 1993;269:1669-1672.

5. Kumar S, Hlady WG, Malecki JM. Risk factors for seabather’s eruption: a prospective cohort study. Public Health Rep 1997;112:59-62.

6. MacSween RM, Williams HC. Lesson of the week: seabather’s eruption-a case of Caribbean itch. Br Med J 1996;312:957-958.

7. Segura-Puertas L, Ramos ME, Aramburo C, Heimer De La Cotera EP, Burnett JW. One Linuche mystery solved: all 3 stages of the coronate scyphomedusa Linuche unguiculata cause seabather’s eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:624-628.

8. Russell MT, Tomchik RS. Clinical articles seabather’s eruption or “sea lice”: New findings and clinical implications [Florida Atlantic University Web site].1995. Available at: www.fau.edu/safe/sea-lice.html. Accessed on July 1, 2003.