User login

Surgical catastrophe: Offering a lifeline to the second victim

CASE A surgeon's story of patient loss

It was a Wednesday morning and Ms. M was my first case of the day. I knew her well, having delivered her 2 children. Now she had a 7-cm complex cyst on her right ovary, she was in pain, and she was possibly experiencing ovarian torsion. My resident took care of the paperwork, I met the patient in preop, answered her few questions, and reassured her husband that I would call him as soon as surgery was over. She was rolled to the operating room.

When I entered the OR, Ms. M was under general anesthesia, draped, and placed on the operating table in the usual position. I made a 5-mm incision at the umbilicus and inserted the trocar under direct visualization. There was blood and the camera became blurry. I removed the camera to clean it, and the anesthesiologist alerted me that there was sudden hypotension. I reinserted the camera and saw blood in the abdomen. I feared the worst—major vessel injury. I requested a scalpel and made a midline skin sub–umbilical incision, entered the peritoneal cavity, and observed blood everywhere. The massive transfusion protocol was activated and vascular surgery was called in. I could not find the source of the bleeding. Using a laparotomy towel I applied pressure on the aorta. The vascular surgeon arrived and pushed my resident away. He identified the source of the bleeding: The right common iliac artery was injured.

The patient coded, the anesthesiologist initiated CPR, bleeding continued, blood was being transfused, and after 20 long minutes of CPR the lifeless body of my patient could not hold any more. She was pronounced dead on the table.

At that moment, there were multiple victims: Ms. M lying on the surgical table; her family members, who did not know what was happening; and the surgical team members, who were looking at each other in denial and feeling that we had failed this patient, hoping that we would wake up from this nightmare.

Defining patient harm

Many patients experience harm each year because of an adverse medical event or preventable medical error.1 A 2013 report revealed that 210,000 to 440,000 deaths occur each year in the United States related to preventable patient harm.2 Although this fact is deeply disturbing, it is well known that modern health care is a high-risk industry.

Medical errors vary in terms of the degree of potential or actual damage. A “near miss” is any event that could have resulted in adverse consequences but did not (for example, an incorrect drug or dose ordered but not administered). On the other hand, an “adverse event” describes an error that resulted in some degree of patient harm or suffering.3

Related article:

Medical errors: Meeting ethical obligations and reducing liability with proper communication

For each patient who dies because of a medical error or a surgical complication, whether preventable or not, many clinicians are involved in the unfolding of the case. These events have a profound impact on well-intentioned, competent, and caring physicians, and they elicit intense emotional responses.4 When a patient experiences an unexpected adverse surgical outcome, the surgeons involved in their care may become “second victims.” They may feel that they have failed the patient and they second-guess their surgical skills and knowledge base; some express concern about their reputation and perhaps career choice.

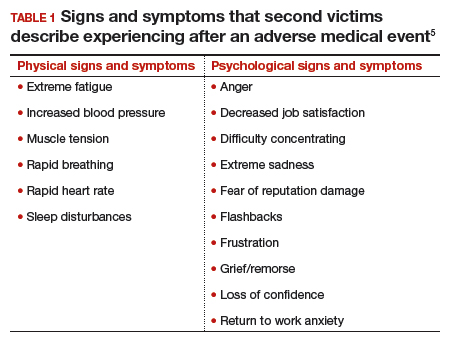

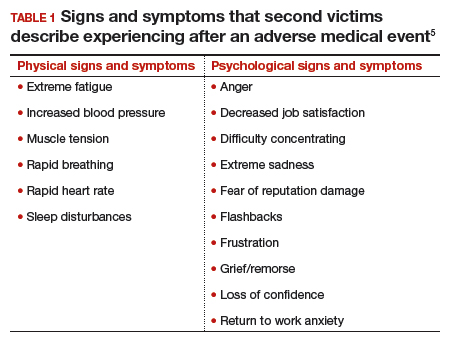

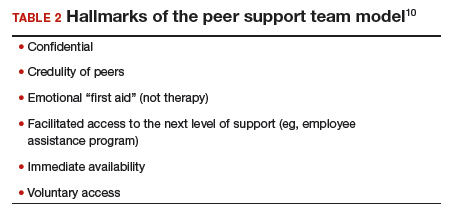

Psychological responses. It is importantto understand this process to ensure a healthy recovery. Psychological responses to an adverse medical event include guilt; distress, anxiety, and fear; frustration and anger; feelings of insufficiency; and long-standing suffering. Clinicians who experienced an adverse medical event have reported additional psychological as well as physical symptoms in the aftermath of the event (TABLE 1).5

Risk factors. Certain factors are associated with a greater emotional impact of an adverse medical event, including6:

- severity of the harm or leaving permanent sequelae

- death of a healthy patient or a child (for example, from a motor vehicle accident)

- self-blame for the error

- unexpected patient death (for example, a catastrophic complication after a relatively benign procedure)

- physicians-in-training responsible for the patient

- first death under a clinician’s watch.

While most research in the field of medical error focuses on systems or process improvement, it is important not to neglect the individual and personal aspects of the clinicians involved in the event. The health care system must include care for our injured colleagues, the so-called second victims.

Read about the steps to recovery for the second victim.

Steps in recovery for the second victim

Based on a semistructured interview of 31 physicians involved in adverse events, Scott and colleagues described the following 6 stages of healing5:

Chaos and accident response. Immediately after the event, the physician feels a sense of confusion, panic, and denial. How can this be happening to me? The physician is frequently distracted, immersed in self-reflection.

Intrusive reflections. This is a period of self-questioning. Thoughts of the event and different possible scenarios dominate the physician’s mind. What if I had done this or that?

Restoring personal integrity. During this phase, the physician seeks support from individuals with whom trusted relationships exist, such as colleagues, peers, close friends, and family members. Advice from a colleague who has your same level of expertise is precious. The second victim often fears that friends and family will not be understanding.

Enduring the inquisition. Root cause analysis and in-depth case review is an important part of the quality improvement process after an adverse event. A debriefing or departmental morbidity and mortality conference can trigger emotions and increase the sense of shame, guilt, and self-doubt. The second victim starts to wonder about repercussions that may affect job security, licensure, and future litigation.

Obtaining emotional first aid. At this stage, the second victim begins to heal, but it is important to obtain external help from a colleague, mentor, counselor, department chair, or loved ones. Many physicians express concerns about not knowing who is a “safe person” to trust in this situation. Often, second victims perceive that their loved ones just do not understand their professional life or should be protected from this situation.

Moving on. There is an urge to move forward with life and simply put the event behind. This is difficult, however. A second victim may follow one of these paths:

- drop out—stop practicing clinical medicine

- survive—maintain the same career but with significant residual emotional burden from the event

- thrive—make something good out of the unfortunate clinical experience.

Related article:

TRUST: How to build a support net for ObGyns affected by a medical error

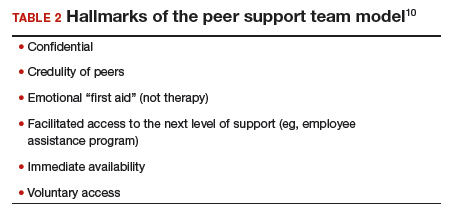

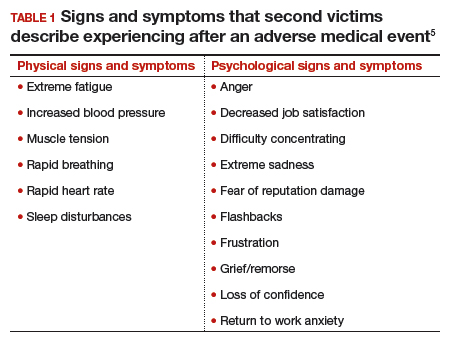

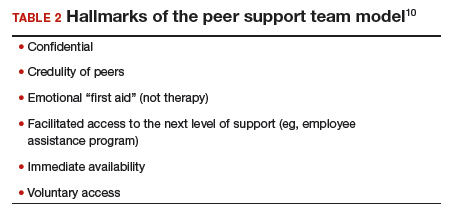

All these programs offer immediate help to any clinician in psychological distress. They provide confidentiality, and the individual is reassured that he or she can safely use the service without further consequences (TABLE 2).10

The normal human response to an adverse medical event can lead to significant psychological consequences, long-term emotional incapacity, impaired performance of clinical care, and feelings of guilt, fear, isolation, or even suicide. At some point during his or her career, almost every physician will be involved in a serious adverse medical event and is at risk of experiencing strong emotional reactions. Health care facilities should have a support system in place to help clinicians cope with these stressful circumstances.

Use these 5 strategies to facilitate recovery

- Be determined. No matter how bad you feel about the event, you need to get up and moving.

- Avoid isolation. Get outside and interact with people. Avoid long periods in isolation. Bring your team together and talk about the event.

- Sleep well. Most symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder occur at night. If you have trouble falling asleep or you wake up in the middle of the night with nightmares related to the event, attempt to regulate your body’s sleep schedule. Seek professional help if needed.

- Avoid negative coping habits. Sometimes people turn to alcohol, cigarettes, food, or drugs to cope. Although these strategies may help in the short term, they will do more harm than good over time.

- Enroll in activities that provide positive distraction. While the mind focuses on the traumatic event (this is normal), you need to get busy with such positive distractions as sports, going to the movies, and engaging in outdoor activities. Do things that you enjoy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kohn L. To err is human: an interview with the Institute of Medicine's Linda Kohn. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2000;26(4):227-234.

- James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128.

- Harrison R, Lawton R, Perlo J, Gardner P, Armitage G, Shapiro J. Emotion and coping in the aftermath of medical error: a cross-country exploration. J Patient Saf. 2015;11(1):28-35.

- Chan ST, Khong PC, Wang W. Psychological responses, coping and supporting needs of healthcare professionals as second victims. Int Nurs Rev. 2017;64(2):242-262.

- Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Brandt J, Hall LW. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider "second victim" after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(5):325-330.

- Waterman AD, Garbutt J, Hazel E, et al. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the United States and Canada. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(8):467-476.

- Shapiro J, Galowitz P. Peer support for clinicians: a programmatic approach. Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1200-1204.

- Edrees H, Connors C, Paine L, Norvell M, Taylor H, Wu AW. Implementing the RISE second victim support programme at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: a case study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011708.

- Johnson B. Code lavender: initiating holistic rapid response at the Cleveland Clinic. Beginnings. 2014;34(2):10-11.

- van Pelt F. Peer support: healthcare professionals supporting each other after adverse medical events. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(4):249-252.

CASE A surgeon's story of patient loss

It was a Wednesday morning and Ms. M was my first case of the day. I knew her well, having delivered her 2 children. Now she had a 7-cm complex cyst on her right ovary, she was in pain, and she was possibly experiencing ovarian torsion. My resident took care of the paperwork, I met the patient in preop, answered her few questions, and reassured her husband that I would call him as soon as surgery was over. She was rolled to the operating room.

When I entered the OR, Ms. M was under general anesthesia, draped, and placed on the operating table in the usual position. I made a 5-mm incision at the umbilicus and inserted the trocar under direct visualization. There was blood and the camera became blurry. I removed the camera to clean it, and the anesthesiologist alerted me that there was sudden hypotension. I reinserted the camera and saw blood in the abdomen. I feared the worst—major vessel injury. I requested a scalpel and made a midline skin sub–umbilical incision, entered the peritoneal cavity, and observed blood everywhere. The massive transfusion protocol was activated and vascular surgery was called in. I could not find the source of the bleeding. Using a laparotomy towel I applied pressure on the aorta. The vascular surgeon arrived and pushed my resident away. He identified the source of the bleeding: The right common iliac artery was injured.

The patient coded, the anesthesiologist initiated CPR, bleeding continued, blood was being transfused, and after 20 long minutes of CPR the lifeless body of my patient could not hold any more. She was pronounced dead on the table.

At that moment, there were multiple victims: Ms. M lying on the surgical table; her family members, who did not know what was happening; and the surgical team members, who were looking at each other in denial and feeling that we had failed this patient, hoping that we would wake up from this nightmare.

Defining patient harm

Many patients experience harm each year because of an adverse medical event or preventable medical error.1 A 2013 report revealed that 210,000 to 440,000 deaths occur each year in the United States related to preventable patient harm.2 Although this fact is deeply disturbing, it is well known that modern health care is a high-risk industry.

Medical errors vary in terms of the degree of potential or actual damage. A “near miss” is any event that could have resulted in adverse consequences but did not (for example, an incorrect drug or dose ordered but not administered). On the other hand, an “adverse event” describes an error that resulted in some degree of patient harm or suffering.3

Related article:

Medical errors: Meeting ethical obligations and reducing liability with proper communication

For each patient who dies because of a medical error or a surgical complication, whether preventable or not, many clinicians are involved in the unfolding of the case. These events have a profound impact on well-intentioned, competent, and caring physicians, and they elicit intense emotional responses.4 When a patient experiences an unexpected adverse surgical outcome, the surgeons involved in their care may become “second victims.” They may feel that they have failed the patient and they second-guess their surgical skills and knowledge base; some express concern about their reputation and perhaps career choice.

Psychological responses. It is importantto understand this process to ensure a healthy recovery. Psychological responses to an adverse medical event include guilt; distress, anxiety, and fear; frustration and anger; feelings of insufficiency; and long-standing suffering. Clinicians who experienced an adverse medical event have reported additional psychological as well as physical symptoms in the aftermath of the event (TABLE 1).5

Risk factors. Certain factors are associated with a greater emotional impact of an adverse medical event, including6:

- severity of the harm or leaving permanent sequelae

- death of a healthy patient or a child (for example, from a motor vehicle accident)

- self-blame for the error

- unexpected patient death (for example, a catastrophic complication after a relatively benign procedure)

- physicians-in-training responsible for the patient

- first death under a clinician’s watch.

While most research in the field of medical error focuses on systems or process improvement, it is important not to neglect the individual and personal aspects of the clinicians involved in the event. The health care system must include care for our injured colleagues, the so-called second victims.

Read about the steps to recovery for the second victim.

Steps in recovery for the second victim

Based on a semistructured interview of 31 physicians involved in adverse events, Scott and colleagues described the following 6 stages of healing5:

Chaos and accident response. Immediately after the event, the physician feels a sense of confusion, panic, and denial. How can this be happening to me? The physician is frequently distracted, immersed in self-reflection.

Intrusive reflections. This is a period of self-questioning. Thoughts of the event and different possible scenarios dominate the physician’s mind. What if I had done this or that?

Restoring personal integrity. During this phase, the physician seeks support from individuals with whom trusted relationships exist, such as colleagues, peers, close friends, and family members. Advice from a colleague who has your same level of expertise is precious. The second victim often fears that friends and family will not be understanding.

Enduring the inquisition. Root cause analysis and in-depth case review is an important part of the quality improvement process after an adverse event. A debriefing or departmental morbidity and mortality conference can trigger emotions and increase the sense of shame, guilt, and self-doubt. The second victim starts to wonder about repercussions that may affect job security, licensure, and future litigation.

Obtaining emotional first aid. At this stage, the second victim begins to heal, but it is important to obtain external help from a colleague, mentor, counselor, department chair, or loved ones. Many physicians express concerns about not knowing who is a “safe person” to trust in this situation. Often, second victims perceive that their loved ones just do not understand their professional life or should be protected from this situation.

Moving on. There is an urge to move forward with life and simply put the event behind. This is difficult, however. A second victim may follow one of these paths:

- drop out—stop practicing clinical medicine

- survive—maintain the same career but with significant residual emotional burden from the event

- thrive—make something good out of the unfortunate clinical experience.

Related article:

TRUST: How to build a support net for ObGyns affected by a medical error

All these programs offer immediate help to any clinician in psychological distress. They provide confidentiality, and the individual is reassured that he or she can safely use the service without further consequences (TABLE 2).10

The normal human response to an adverse medical event can lead to significant psychological consequences, long-term emotional incapacity, impaired performance of clinical care, and feelings of guilt, fear, isolation, or even suicide. At some point during his or her career, almost every physician will be involved in a serious adverse medical event and is at risk of experiencing strong emotional reactions. Health care facilities should have a support system in place to help clinicians cope with these stressful circumstances.

Use these 5 strategies to facilitate recovery

- Be determined. No matter how bad you feel about the event, you need to get up and moving.

- Avoid isolation. Get outside and interact with people. Avoid long periods in isolation. Bring your team together and talk about the event.

- Sleep well. Most symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder occur at night. If you have trouble falling asleep or you wake up in the middle of the night with nightmares related to the event, attempt to regulate your body’s sleep schedule. Seek professional help if needed.

- Avoid negative coping habits. Sometimes people turn to alcohol, cigarettes, food, or drugs to cope. Although these strategies may help in the short term, they will do more harm than good over time.

- Enroll in activities that provide positive distraction. While the mind focuses on the traumatic event (this is normal), you need to get busy with such positive distractions as sports, going to the movies, and engaging in outdoor activities. Do things that you enjoy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE A surgeon's story of patient loss

It was a Wednesday morning and Ms. M was my first case of the day. I knew her well, having delivered her 2 children. Now she had a 7-cm complex cyst on her right ovary, she was in pain, and she was possibly experiencing ovarian torsion. My resident took care of the paperwork, I met the patient in preop, answered her few questions, and reassured her husband that I would call him as soon as surgery was over. She was rolled to the operating room.

When I entered the OR, Ms. M was under general anesthesia, draped, and placed on the operating table in the usual position. I made a 5-mm incision at the umbilicus and inserted the trocar under direct visualization. There was blood and the camera became blurry. I removed the camera to clean it, and the anesthesiologist alerted me that there was sudden hypotension. I reinserted the camera and saw blood in the abdomen. I feared the worst—major vessel injury. I requested a scalpel and made a midline skin sub–umbilical incision, entered the peritoneal cavity, and observed blood everywhere. The massive transfusion protocol was activated and vascular surgery was called in. I could not find the source of the bleeding. Using a laparotomy towel I applied pressure on the aorta. The vascular surgeon arrived and pushed my resident away. He identified the source of the bleeding: The right common iliac artery was injured.

The patient coded, the anesthesiologist initiated CPR, bleeding continued, blood was being transfused, and after 20 long minutes of CPR the lifeless body of my patient could not hold any more. She was pronounced dead on the table.

At that moment, there were multiple victims: Ms. M lying on the surgical table; her family members, who did not know what was happening; and the surgical team members, who were looking at each other in denial and feeling that we had failed this patient, hoping that we would wake up from this nightmare.

Defining patient harm

Many patients experience harm each year because of an adverse medical event or preventable medical error.1 A 2013 report revealed that 210,000 to 440,000 deaths occur each year in the United States related to preventable patient harm.2 Although this fact is deeply disturbing, it is well known that modern health care is a high-risk industry.

Medical errors vary in terms of the degree of potential or actual damage. A “near miss” is any event that could have resulted in adverse consequences but did not (for example, an incorrect drug or dose ordered but not administered). On the other hand, an “adverse event” describes an error that resulted in some degree of patient harm or suffering.3

Related article:

Medical errors: Meeting ethical obligations and reducing liability with proper communication

For each patient who dies because of a medical error or a surgical complication, whether preventable or not, many clinicians are involved in the unfolding of the case. These events have a profound impact on well-intentioned, competent, and caring physicians, and they elicit intense emotional responses.4 When a patient experiences an unexpected adverse surgical outcome, the surgeons involved in their care may become “second victims.” They may feel that they have failed the patient and they second-guess their surgical skills and knowledge base; some express concern about their reputation and perhaps career choice.

Psychological responses. It is importantto understand this process to ensure a healthy recovery. Psychological responses to an adverse medical event include guilt; distress, anxiety, and fear; frustration and anger; feelings of insufficiency; and long-standing suffering. Clinicians who experienced an adverse medical event have reported additional psychological as well as physical symptoms in the aftermath of the event (TABLE 1).5

Risk factors. Certain factors are associated with a greater emotional impact of an adverse medical event, including6:

- severity of the harm or leaving permanent sequelae

- death of a healthy patient or a child (for example, from a motor vehicle accident)

- self-blame for the error

- unexpected patient death (for example, a catastrophic complication after a relatively benign procedure)

- physicians-in-training responsible for the patient

- first death under a clinician’s watch.

While most research in the field of medical error focuses on systems or process improvement, it is important not to neglect the individual and personal aspects of the clinicians involved in the event. The health care system must include care for our injured colleagues, the so-called second victims.

Read about the steps to recovery for the second victim.

Steps in recovery for the second victim

Based on a semistructured interview of 31 physicians involved in adverse events, Scott and colleagues described the following 6 stages of healing5:

Chaos and accident response. Immediately after the event, the physician feels a sense of confusion, panic, and denial. How can this be happening to me? The physician is frequently distracted, immersed in self-reflection.

Intrusive reflections. This is a period of self-questioning. Thoughts of the event and different possible scenarios dominate the physician’s mind. What if I had done this or that?

Restoring personal integrity. During this phase, the physician seeks support from individuals with whom trusted relationships exist, such as colleagues, peers, close friends, and family members. Advice from a colleague who has your same level of expertise is precious. The second victim often fears that friends and family will not be understanding.

Enduring the inquisition. Root cause analysis and in-depth case review is an important part of the quality improvement process after an adverse event. A debriefing or departmental morbidity and mortality conference can trigger emotions and increase the sense of shame, guilt, and self-doubt. The second victim starts to wonder about repercussions that may affect job security, licensure, and future litigation.

Obtaining emotional first aid. At this stage, the second victim begins to heal, but it is important to obtain external help from a colleague, mentor, counselor, department chair, or loved ones. Many physicians express concerns about not knowing who is a “safe person” to trust in this situation. Often, second victims perceive that their loved ones just do not understand their professional life or should be protected from this situation.

Moving on. There is an urge to move forward with life and simply put the event behind. This is difficult, however. A second victim may follow one of these paths:

- drop out—stop practicing clinical medicine

- survive—maintain the same career but with significant residual emotional burden from the event

- thrive—make something good out of the unfortunate clinical experience.

Related article:

TRUST: How to build a support net for ObGyns affected by a medical error

All these programs offer immediate help to any clinician in psychological distress. They provide confidentiality, and the individual is reassured that he or she can safely use the service without further consequences (TABLE 2).10

The normal human response to an adverse medical event can lead to significant psychological consequences, long-term emotional incapacity, impaired performance of clinical care, and feelings of guilt, fear, isolation, or even suicide. At some point during his or her career, almost every physician will be involved in a serious adverse medical event and is at risk of experiencing strong emotional reactions. Health care facilities should have a support system in place to help clinicians cope with these stressful circumstances.

Use these 5 strategies to facilitate recovery

- Be determined. No matter how bad you feel about the event, you need to get up and moving.

- Avoid isolation. Get outside and interact with people. Avoid long periods in isolation. Bring your team together and talk about the event.

- Sleep well. Most symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder occur at night. If you have trouble falling asleep or you wake up in the middle of the night with nightmares related to the event, attempt to regulate your body’s sleep schedule. Seek professional help if needed.

- Avoid negative coping habits. Sometimes people turn to alcohol, cigarettes, food, or drugs to cope. Although these strategies may help in the short term, they will do more harm than good over time.

- Enroll in activities that provide positive distraction. While the mind focuses on the traumatic event (this is normal), you need to get busy with such positive distractions as sports, going to the movies, and engaging in outdoor activities. Do things that you enjoy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kohn L. To err is human: an interview with the Institute of Medicine's Linda Kohn. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2000;26(4):227-234.

- James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128.

- Harrison R, Lawton R, Perlo J, Gardner P, Armitage G, Shapiro J. Emotion and coping in the aftermath of medical error: a cross-country exploration. J Patient Saf. 2015;11(1):28-35.

- Chan ST, Khong PC, Wang W. Psychological responses, coping and supporting needs of healthcare professionals as second victims. Int Nurs Rev. 2017;64(2):242-262.

- Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Brandt J, Hall LW. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider "second victim" after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(5):325-330.

- Waterman AD, Garbutt J, Hazel E, et al. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the United States and Canada. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(8):467-476.

- Shapiro J, Galowitz P. Peer support for clinicians: a programmatic approach. Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1200-1204.

- Edrees H, Connors C, Paine L, Norvell M, Taylor H, Wu AW. Implementing the RISE second victim support programme at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: a case study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011708.

- Johnson B. Code lavender: initiating holistic rapid response at the Cleveland Clinic. Beginnings. 2014;34(2):10-11.

- van Pelt F. Peer support: healthcare professionals supporting each other after adverse medical events. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(4):249-252.

- Kohn L. To err is human: an interview with the Institute of Medicine's Linda Kohn. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2000;26(4):227-234.

- James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128.

- Harrison R, Lawton R, Perlo J, Gardner P, Armitage G, Shapiro J. Emotion and coping in the aftermath of medical error: a cross-country exploration. J Patient Saf. 2015;11(1):28-35.

- Chan ST, Khong PC, Wang W. Psychological responses, coping and supporting needs of healthcare professionals as second victims. Int Nurs Rev. 2017;64(2):242-262.

- Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Brandt J, Hall LW. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider "second victim" after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(5):325-330.

- Waterman AD, Garbutt J, Hazel E, et al. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the United States and Canada. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(8):467-476.

- Shapiro J, Galowitz P. Peer support for clinicians: a programmatic approach. Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1200-1204.

- Edrees H, Connors C, Paine L, Norvell M, Taylor H, Wu AW. Implementing the RISE second victim support programme at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: a case study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011708.

- Johnson B. Code lavender: initiating holistic rapid response at the Cleveland Clinic. Beginnings. 2014;34(2):10-11.

- van Pelt F. Peer support: healthcare professionals supporting each other after adverse medical events. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(4):249-252.

Fast Tracks

- A "near miss" is any event that could have resulted in adverse consequences but did not. An "adverse event" describes an error that resulted in some degree of patient harm or suffering.

- At some point in his or her career, almost every physician will be involved in a serious adverse medical event and is at risk of experiencing strong emotional reactions