User login

E-cigarettes: Who’s using them and why?

ABSTRACT

Background Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are often marketed as safe and effective aids for quitting cigarette smoking, but concerns remain that use of e-cigarettes might actually reduce the number of quit attempts. To address these issues, we characterized the utilization and demographic correlates of dual use of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes (referred to here as simply “cigarettes”) among smokers in a rural population of Illinois.

Methods The majority of survey participants were recruited from the 2014 Illinois State Fair and from another event—the Springfield Mile (a motorcycle racing event)—in Springfield, Ill. Survey questions explored participant demographics and cigarette and e-cigarette use history.

Results Of 201 total cigarette smokers, 79 smoked only tobacco cigarettes (smokers), while 122 also used e-cigarettes (dual users). Dual users did not differ significantly from smokers in gender, age, income, or education. Compared to smokers, dual users were more likely to smoke within 30 minutes of awakening (odds ratio [OR]=3.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.8-6.3), but did not smoke more cigarettes per day or perceive a greater likelihood of quit success. Non-white dual users smoked fewer cigarettes per day than smokers. In addition, 79.5% of all dual users reported that they were using e-cigarettes to quit smoking or reduce the number of cigarettes smoked, and white respondents were 6 times more likely than non-whites to use e-cigarettes for ‘trying to quit smoking’ (OR=6.0; 95% CI, 1.1-32.9). Males and respondents with lower income were less likely to say they were using e-cigarettes to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked than females or participants with higher income (OR=0.2; 95% CI, 0.1-0.8 and OR=0.1; 95% CI, 0.0-0.5, respectively).

Conclusions E-cigarettes may significantly alter the landscape of nicotine physical dependence, and local influences likely are associated with use patterns. Future research should continue to examine whether dual use of traditional and electronic cigarettes impacts smoking cessation, and clinicians should be aware that local norms may create differences from national level data.

Approximately 21% of US adults use tobacco products at least occasionally.1 Although smoking prevalence has declined in recent years (from 21% in 2005 to 18% in 2013), it remains high among certain groups (eg, males and those with a high school education or less).2 As we know, the health burden of smoking—as a cause of death from cancer, pulmonary disease, and heart disease—is substantial,3,4 and rural areas experience a significantly higher prevalence of smoking compared to urban areas.2,5,6

However, it is unknown if the context and habits surrounding tobacco use in rural and/or Midwestern areas are similar to those of urban or nationally-representative populations. For example, while many urban residents may encounter a multitude of media messages encouraging smoking cessation resulting in less community acceptance of smoking, rural residents may be exposed to substantially fewer messages (eg, no city bus signs, billboards, subway posters, etc.) and the community may be more accommodating and tolerant of smoking.

Do e-cigarettes increase cigarette smoking?

Public health professionals are concerned about the increased use of e-cigarettes, particularly among young people, and whether this use increases the likelihood that individuals will start smoking tobacco cigarettes.7(Throughout this paper, we will use “cigarettes” and “smoking” to refer to the use of traditional tobacco cigarettes.) A recent study found that adolescents who used electronic nicotine delivery systems were twice as likely as non-users to have tried cigarettes in the past year.8

An onslaught of advertising. There are also concerns that e-cigarettes may serve to ‘renormalize’ nicotine addiction, in part through large-scale advertising, which was seen by nearly 70% of the participants in the 2014 National Youth Tobacco Survey.9 Largely as a result of that advertising, e-cigarette sales exceed $1.7 billion in the United States alone.10 With 15% of all US adults having ever tried electronic nicotine delivery systems and more than half (52%) of smokers having done so, questions regarding their health impact cannot be taken lightly.11

Do e-cigarettes help people quit smoking? E-cigarettes are often marketed as a safe and effective means for quitting cigarette smoking.12-14 (See "E-cigarettes: How "safe" are they?") Nearly two-thirds of physicians report being asked about e-cigarettes by their patients and approximately one-third of physicians recommend using them as a smoking cessation aid.15

Claims regarding the usefulness of e-cigarettes in smoking cessation, however, have not been substantiated by high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In fact, no RCTs have shown them to be safer or more effective than cessation treatments currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.16,17

Two studies reflect the conflicting data that are currently available. One small study found intensive e-cigarette users were 6 times more likely than non-users/triers to report successful smoking cessation.18 However, researchers surveying callers of a cigarette quit line found that smokers who used e-cigarettes (dual users) were less likely to quit smoking than non-users.19

The lack of good-quality data substantiates the concern that dual use might discourage quitting by normalizing cigarette use and reducing perceptions of harm.20,21 Dual use may also hamper smoking cessation efforts by increasing nicotine physical dependence and associated withdrawal symptoms when trying to quit.22 And finally, dual use may expose users to more carcinogens and toxins than those who use only one product, and the average number of cigarettes smoked per day may be significantly higher among dual users.23

Unique demographic factors at work? Finally, the social and community context within which smoking occurs, and the prevalence of smoking-associated demographic risk factors, may vary significantly between rural and urban areas and between seemingly similar rural areas.24-27 Few studies have examined differences in e-cigarette use between rural and urban areas. Those that have are contradictory, reporting that rural residents use e-cigarettes both more and less than their urban peers,28,29 but many of these studies were conducted outside the United States, where the context and norms associated with smoking and e-cigarette use likely vary.

For these reasons, we sought to examine e-cigarette use among residents of Illinois, the nation’s fifth largest state and one with a rural population exceeding 1.5 million.30 We compared dual users of e-cigarettes and cigarettes to smokers of cigarettes only in terms of demographic characteristics, nicotine physical dependence, and smoking cessation beliefs, and explored dual smokers' reasons for using both types of cigarettes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A survey was fielded during August and September 2014 in Springfield, Ill. To obtain responses, a booth was set up at both the Illinois State Fair and the Springfield Mile (a motorcycle racing event), and participants were recruited via direct solicitation by project staff. This was supplemented by an email invitation to all employees of the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. The 2 venues and the email strategy were chosen because they draw from a large area of central and southern Illinois and were convenient to the location of the study team. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were ≥18 years of age and used any tobacco product or e-cigarettes. Survey elements were derived from 2 national surveys of health and behavior—the Minnesota Adult Tobacco Survey 201031 and the Brief Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult.32

Survey questions assessed cigarette use, nicotine physical dependence, social norms, perceived risks and benefits, and smoking cessation beliefs and behaviors. Questions were slightly reworded to address not only the use of traditional cigarettes, but the use of e-cigarettes, as well. Ultimately, each participant answered a similarly-worded set of questions for both regular and e-cigarettes. Dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes was also assessed. Participants self-reported all data and survey responses on an electronic tablet and received a $10 (cash or gift card) incentive. This project was reviewed and approved by the Springfield Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects.

Stratification of results. Race was dichotomized into white and non-white. Education was stratified into 3 categories: up to and including high school graduation, some college but not a Bachelor’s degree, and Bachelor’s degree and above. Income was divided as being ≤$20,000 or >$20,000, and age was split into 2 groups by the median value. Analyses included descriptions of participant demographics, dual use status, measures of nicotine physical dependence, quit attempts, and e-cigarette use motivations. Bivariate relationships between dual use status and demographic characteristics, nicotine physical dependence, and smoking cessation beliefs were analyzed by chi-square (categorical variables) and ANOVA (continuous/Likert variables).

Multivariable logistic regression modeling of the demographic variables and dual use status (cigarette smoker only vs dual user) was performed to predict 3 factors: number of cigarettes smoked per day (≤10 vs 11+); time to first cigarette (≤30 vs 31+ minutes from waking); and perceived likelihood of quit attempt success (very/somewhat likely vs very/somewhat unlikely). Multivariable models examining the reasons for dual use included the demographic, nicotine physical dependence, and cessation belief items described previously.

RESULTS

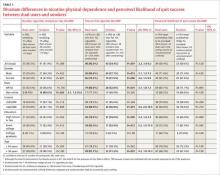

Of 309 total survey participants (Fair=288; Race=12; Email=9), there were 235 current cigarette smokers consisting of 79 who smoked only cigarettes (smokers); 122 who used both cigarettes and e-cigarettes (dual users); and 34 former e-cigarette users. Only smokers and dual users were included in this analysis (N=201, although for the purposes of TABLE 1, N=200 or 199 because at least one participant did not provide answers to all of the questions). Approximately 51% of the smokers were male, 78% were white, 12% were 4-year college graduates, and 57% reported incomes >$20,000. The mean age was 37.7 years (SD=14.4); 50% of respondents were <35 years of age. Dual users did not vary significantly from smokers in terms of gender, age, education, or income (all P>.05). However, a greater proportion of whites vs non-whites were dual users (54.9% vs 42.3%; P=.035).

Click here to see an enlarged version of the table.

No big quit differences. Bivariate analyses revealed that dual users were no more likely than smokers to have attempted to quit smoking within the past year (X2=2.3; P=.14), consider quitting in the next one or 6 months (X2=1.1; P=.34), or differ in perceived likelihood of cessation success (X2=0.0; P=1.00). The proportion of dual users who smoked 11+ cigarettes per day did not differ from that of cigarette smokers for the group as a whole or when the group was stratified by gender, income, education, or age. However, among non-whites, dual users smoked fewer cigarettes than cigarette smokers (TABLE 1).

Predicting physical dependence. Significant differences also were observed regarding the timing of the first cigarette of the day, with dual users approximately 3 times more likely than smokers to smoke within 30 minutes of awakening (80% vs 54.4%; OR=3.3; 95% CI, 1.8-6.3), and this difference was upheld among males, females, whites, those with an income >$20,000, those with a high school education or less and those with some college education, and age >34 years. There was no association, however, between dual use and perceived likelihood of quit success.

We then performed multivariable logistic modeling on dual users to determine which variables might predict 3 measures of physical dependence: number of cigarettes smoked per day (≤10 vs 11+), time between waking and smoking the first cigarette of the day (≤30 vs 31+ minutes), and perceived likelihood of cessation success (TABLE 2). Male gender (OR=3.4; 95% CI, 1.8-6.5) and white race (OR=4.4; 95% CI, 1.9-10.1) were significant for predicting smoking 11+ cigarettes a day, while dual use status was insignificant (P=.104). Regarding time to first cigarette, only dual use was significant (OR=3.1; 95% CI, 1.6-5.9), with dual users approximately 3 times more likely than smokers to have their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking. No variables were significant in predicting perceived likelihood of quit success.

Reasons for dual use. We examined reasons for dual use with the question: Do you use e-cigarettes to reduce your regular tobacco use? Here, 79.5% of smokers reported using e-cigarettes to quit smoking or reduce the number of cigarettes smoked.

A multivariable polynomial logistic regression that included only dual users was performed to examine which variables might predict use for tobacco cessation (“trying to quit smoking”) vs reduction in smoking intensity (“trying to reduce the number of regular cigarettes I smoke per day”) vs no change (“use the same amount of tobacco as always”) (TABLE 2). Whites were approximately 6 times more likely than non-whites to indicate they engage in dual use to try to quit smoking (OR=6.0; 95% CI, 1.1-32.9). Males and people with lower incomes were much less likely to indicate they engaged in dual use to try to reduce the number of regular cigarettes smoked than females or those with higher incomes (OR=0.2; 95% CI, 0.1-0.8 and OR=0.1, 95% CI, 0.0-0.5, respectively). No other demographic variables or measures of nicotine physical dependence were significantly different between dual users and smokers.

Click here to see an enlarged version of the table.

DISCUSSION

E-cigarettes are used by approximately half of smokers (52%), which is much higher than that reported by Delnevo, et al, in their analysis of the National Health Interview Study.33 There, prevalence of dual use of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes ranged from 3.4% to 12.7%. This substantial difference raises important questions regarding study population characterization. Were participants in our study representative of central Illinois, state fair attendees, or the agricultural profession? Further work to identify this group with an increased propensity for dual use will assist clinicians in developing appropriate intervention strategies.

Dual use in our study did not vary by many customary demographic variables. Nor was it associated with different rates of past or future quit attempts or perceived ability to successfully quit if quitting was attempted. These factors—high rates of dual use and insignificant effect on quit attempts—may have implications for local physicians counseling patients who smoke.

In our study, the majority of smokers already use e-cigarettes, and this does not seem to increase their ability/likelihood to quit smoking. Further, dual use did not seem to be associated with overall cigarette consumption; males and white participants smoked more cigarettes than females and non-whites. But dual use was associated with a measure of increased nicotine physical dependence (earlier first cigarette of the day). As a result, physicians may want to think twice before recommending e-cigarette use as a means of smoking cessation.

In addition to the high prevalence of e-cigarette use among smokers, a number of other interesting findings surfaced that run counter to some of the current literature. First, dual users are no more likely than smokers to have tried to quit in the past or to try to quit in the future.21,22,34 It could be that for the relatively small geographical area from which our participants were recruited (central Illinois; ~77% of participants from Sangamon County alone), the local context and culture of smoking differs from that associated with participants in other studies, who were mostly recruited from national and regional online surveys. However, there is no a priori reason to suspect Sangamon County is especially different, as it is quite similar to Illinois as a whole by many measures (eg, percentage rural: 14.1% vs 11.5%; percentage black (only): 12.4% vs 14.7%; education to at least a Bachelor’s degree: 33.0% vs 31.9%; and median household income: $55,565 vs $57,166).30

While we found that dual users did have one measure of increased nicotine physical dependence, the total number of cigarettes consumed per day was not significantly different from that of smokers.23-25 This is contrary to another study of nicotine physical dependence, but, unlike that study, we did not assess length of time of concurrent use.35 There is much uncertainty surrounding the issue of nicotine physical dependence and e-cigarette use, largely because the level of nicotine delivered by various e-products varies significantly.36

Cross-sectional nature, small sample size limit utility of data

There are significant limitations to this study, including the cross-sectional nature of the data, the small sample size, the use of self-report, and the limited scope of recruitment. The relatively small sample size limits our ability to observe small differences and effect sizes. However, small differences often lack practical significance. Finally, participation was limited to those attending a state fair or a local sporting event and those employed by a local medical school. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to populations outside central Illinois. On the other hand, the very low income sample recruited from the Midwestern US, which is underrepresented in prior e-cigarette research, might represent some of the strengths of this work.

Future investigations. Future studies should more closely examine e-cigarette use prevalence on smaller geographic scales and especially in rural areas where there is a paucity of research. As the majority of our respondents came from a single county in central Illinois, one has to ask the questions, “Is this a ‘hot spot’ for e-cigarette use?" And "Do other rural areas experience similar use?” It may be important to know if national surveys are sensitive enough to observe significant local variations. Research also should examine how e-cigarette use and the influence of local culture vary across wider areas.

Several specific areas of study would help to inform policy and intervention development. For example, is tobacco cigarette quit success impacted by concurrent e-cigarette use? While our study showed no difference in past or possible future quit attempts among dual users as compared with smokers, we did not assess actual quit success, and multiple participants in our study anecdotally described using e-cigarettes to successfully quit smoking.

In the end, the rapid increase in the use of e-cigarettes has the potential to significantly alter the landscape of nicotine physical dependence, and local culture and other influences are likely associated with use patterns.

CORRESPONDENCE

Wiley D. Jenkins, PhD, MPH, Science Director, Population Health Science Program, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, 201 E. Madison St., Springfield, IL 62794-9664; [email protected].

1. Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2012-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:542-547.

2. Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1108-1112.

3. Siegel RL, Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, et al. Deaths due to cigarette smoking for 12 smoking-related cancers in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1574-1576.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/index.html. Accessed January 22, 2014.

5. Gamm LD, Hutchison LL, Dabney BJ, et al, eds. (2003). Rural Healthy People 2010: A companion document to Healthy People 2010. Volume 2. College Station, TX: The Texas A&M University System Health Science Center, School of Rural Public Health, Southwest Rural Health Research Center.

6. Doescher MP, Jackson JE, Jerant A, et al. Prevalence and trends in smoking: a national rural study. J Rural Health. 2006;22:112-118.

7. Bunnell RE, Agaku IT, Arrazola RA, et al. Intentions to smoke cigarettes among never-smoking US middle and high school electronic cigarette users: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:228-235.

8. Cardenas VM, Evans VL, Balamurugan A, et al. Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems and recent initiation of smoking among US youth. Int J Public Health. 2016;61:237-241.

9. Auf R, Trepka MJ, Cano MA, et al. Electronic cigarettes: the renormalisation of nicotine use. BMJ. 2016;352:i425.

10. CNBC. E-cigarette sales are smoking hot, set to hit $1.7 billion. Available at: http://www.cnbc.com/id/100991511. Accessed April 5, 2016.

11. Weaver SR, Majeed BA, Pechacek TF, et al. Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems and other tobacco products among USA adults, 2014: results from a national survey. Int J Public Health. 2016;61:177-188.

12. Richardson A, Ganz O, Vallone D. Tobacco on the web: surveillance and characterisation of online tobacco and e-cigarette advertising. Tob Control. 2015;24:341-347.

13. Paek HJ, Kim S, Hove T, et al. Reduced harm or another gateway to smoking? source, message, and information characteristics of E-cigarette videos on YouTube. J Health Commun. 2014;19:545-560.

14. Kim AE, Arnold KY, Makarenko O. E-cigarette advertising expenditures in the U.S., 2011-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:409-412.

15. Steinberg MB, Giovenco DP, Delnevo CD. Patient-physician communication regarding electronic cigarettes. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:96-98.

16. Gualano MR, Passi S, Bert F, et al. Electronic cigarettes: assessing the efficacy and the adverse effects through a systematic review of published studies. J Public Health (Oxf). 2015:37:488-497.

17. U.S. National Institutes of Health. ClinicalTrials.gov. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=%22electronic+cigarette%22&Search=Search. Accessed July 10, 2015.

18. Biener L, Hargraves JL. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use among a population-based sample of adult smokers: association with smoking cessation and motivation to quit. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:127-133.

19. Vickerman KA, Carpenter KM, Altman T, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes among state tobacco cessation quitline callers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1787-1791.

20. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Press Release February 28,2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2013/p0228_electronic_cigarettes.html. Accessed July 8, 2015.

21. Pisinger C. Why public health people are more worried than excited over e-cigarettes. BMC Med. 2014;12:226.

22. Post A, Gilljam H, Rosendahl I, et al. Symptoms of nicotine dependence in a cohort of Swedish youths: a comparison between smokers, smokeless tobacco users and dual tobacco users. Addiction. 2010;105:740-746.

23. Mazurek JM, Syamlal G, King BA, et al; Division of Respiratory Disease Studies, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, CDC. Smokeless tobacco use among working adults—United States, 2005 and 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:477-482.

24. Hutcheson TD, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Understanding smoking cessation in rural communities. J Rural Health. 2008;24:116-124.

25. McMillen R, Breen J, Cosby AG. Rural-urban differences in the social climate surrounding environmental tobacco smoke: a report from the 2002 Social Climate Survey of Tobacco Control. J Rural Health. 2004;20:7-16.

26. Butler KM, Rayens MK, Adkins S, et al. Culturally-specific smoking cessation outreach in a rural community. Public Health Nurs. 2014;31:44-54.

27. Butler KM, Hedgecock S, Record RA, et al. An evidence-based cessation strategy using rural smokers’ experiences with tobacco. Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47:31-43.

28. Hamilton HA, Ferrence R, Boak A, et al. Ever use of nicotine and nonnicotine electronic cigarettes among high school students in Ontario, Canada. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:1212-1218.

29. Goniewicz ML, Zielinska-Danch W. Electronic cigarette use among teenagers and young adults in Poland. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e879-e885.

30. US Census Bureau. 2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. Available at: http://www.census.gov/geo/reference/ua/urban-rural-2010.html. Accessed March 13, 2016.

31. Minnesota Adult Tobacco Survey. Tobacco use in Minnesota: 1999-2014. Available at: http://www.mnadulttobaccosurvey.org/. Accessed April 27, 2016.

32. Rash CJ, Copeland AL. The Brief Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult (BSCQ-A): development of a short form of the SCQ-A. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1633-1643.

33. Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Steinberg MB, et al. Patterns of electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:715-719.

34. Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, et al. Multiple tobacco product use among adults in the United States: cigarettes, cigars, electronic cigarettes, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus. Prev Med. 2014;62:14-19.

35. Etter JF, Eissenberg T. Dependence levels in users of electronic cigarettes, nicotine gums and tobacco cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:68-75.

36. Cobb CO, Hendricks PS, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes and nicotine dependence: evolving products, evolving problems. BMC Med. 2015;13:119.

ABSTRACT

Background Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are often marketed as safe and effective aids for quitting cigarette smoking, but concerns remain that use of e-cigarettes might actually reduce the number of quit attempts. To address these issues, we characterized the utilization and demographic correlates of dual use of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes (referred to here as simply “cigarettes”) among smokers in a rural population of Illinois.

Methods The majority of survey participants were recruited from the 2014 Illinois State Fair and from another event—the Springfield Mile (a motorcycle racing event)—in Springfield, Ill. Survey questions explored participant demographics and cigarette and e-cigarette use history.

Results Of 201 total cigarette smokers, 79 smoked only tobacco cigarettes (smokers), while 122 also used e-cigarettes (dual users). Dual users did not differ significantly from smokers in gender, age, income, or education. Compared to smokers, dual users were more likely to smoke within 30 minutes of awakening (odds ratio [OR]=3.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.8-6.3), but did not smoke more cigarettes per day or perceive a greater likelihood of quit success. Non-white dual users smoked fewer cigarettes per day than smokers. In addition, 79.5% of all dual users reported that they were using e-cigarettes to quit smoking or reduce the number of cigarettes smoked, and white respondents were 6 times more likely than non-whites to use e-cigarettes for ‘trying to quit smoking’ (OR=6.0; 95% CI, 1.1-32.9). Males and respondents with lower income were less likely to say they were using e-cigarettes to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked than females or participants with higher income (OR=0.2; 95% CI, 0.1-0.8 and OR=0.1; 95% CI, 0.0-0.5, respectively).

Conclusions E-cigarettes may significantly alter the landscape of nicotine physical dependence, and local influences likely are associated with use patterns. Future research should continue to examine whether dual use of traditional and electronic cigarettes impacts smoking cessation, and clinicians should be aware that local norms may create differences from national level data.

Approximately 21% of US adults use tobacco products at least occasionally.1 Although smoking prevalence has declined in recent years (from 21% in 2005 to 18% in 2013), it remains high among certain groups (eg, males and those with a high school education or less).2 As we know, the health burden of smoking—as a cause of death from cancer, pulmonary disease, and heart disease—is substantial,3,4 and rural areas experience a significantly higher prevalence of smoking compared to urban areas.2,5,6

However, it is unknown if the context and habits surrounding tobacco use in rural and/or Midwestern areas are similar to those of urban or nationally-representative populations. For example, while many urban residents may encounter a multitude of media messages encouraging smoking cessation resulting in less community acceptance of smoking, rural residents may be exposed to substantially fewer messages (eg, no city bus signs, billboards, subway posters, etc.) and the community may be more accommodating and tolerant of smoking.

Do e-cigarettes increase cigarette smoking?

Public health professionals are concerned about the increased use of e-cigarettes, particularly among young people, and whether this use increases the likelihood that individuals will start smoking tobacco cigarettes.7(Throughout this paper, we will use “cigarettes” and “smoking” to refer to the use of traditional tobacco cigarettes.) A recent study found that adolescents who used electronic nicotine delivery systems were twice as likely as non-users to have tried cigarettes in the past year.8

An onslaught of advertising. There are also concerns that e-cigarettes may serve to ‘renormalize’ nicotine addiction, in part through large-scale advertising, which was seen by nearly 70% of the participants in the 2014 National Youth Tobacco Survey.9 Largely as a result of that advertising, e-cigarette sales exceed $1.7 billion in the United States alone.10 With 15% of all US adults having ever tried electronic nicotine delivery systems and more than half (52%) of smokers having done so, questions regarding their health impact cannot be taken lightly.11

Do e-cigarettes help people quit smoking? E-cigarettes are often marketed as a safe and effective means for quitting cigarette smoking.12-14 (See "E-cigarettes: How "safe" are they?") Nearly two-thirds of physicians report being asked about e-cigarettes by their patients and approximately one-third of physicians recommend using them as a smoking cessation aid.15

Claims regarding the usefulness of e-cigarettes in smoking cessation, however, have not been substantiated by high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In fact, no RCTs have shown them to be safer or more effective than cessation treatments currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.16,17

Two studies reflect the conflicting data that are currently available. One small study found intensive e-cigarette users were 6 times more likely than non-users/triers to report successful smoking cessation.18 However, researchers surveying callers of a cigarette quit line found that smokers who used e-cigarettes (dual users) were less likely to quit smoking than non-users.19

The lack of good-quality data substantiates the concern that dual use might discourage quitting by normalizing cigarette use and reducing perceptions of harm.20,21 Dual use may also hamper smoking cessation efforts by increasing nicotine physical dependence and associated withdrawal symptoms when trying to quit.22 And finally, dual use may expose users to more carcinogens and toxins than those who use only one product, and the average number of cigarettes smoked per day may be significantly higher among dual users.23

Unique demographic factors at work? Finally, the social and community context within which smoking occurs, and the prevalence of smoking-associated demographic risk factors, may vary significantly between rural and urban areas and between seemingly similar rural areas.24-27 Few studies have examined differences in e-cigarette use between rural and urban areas. Those that have are contradictory, reporting that rural residents use e-cigarettes both more and less than their urban peers,28,29 but many of these studies were conducted outside the United States, where the context and norms associated with smoking and e-cigarette use likely vary.

For these reasons, we sought to examine e-cigarette use among residents of Illinois, the nation’s fifth largest state and one with a rural population exceeding 1.5 million.30 We compared dual users of e-cigarettes and cigarettes to smokers of cigarettes only in terms of demographic characteristics, nicotine physical dependence, and smoking cessation beliefs, and explored dual smokers' reasons for using both types of cigarettes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A survey was fielded during August and September 2014 in Springfield, Ill. To obtain responses, a booth was set up at both the Illinois State Fair and the Springfield Mile (a motorcycle racing event), and participants were recruited via direct solicitation by project staff. This was supplemented by an email invitation to all employees of the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. The 2 venues and the email strategy were chosen because they draw from a large area of central and southern Illinois and were convenient to the location of the study team. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were ≥18 years of age and used any tobacco product or e-cigarettes. Survey elements were derived from 2 national surveys of health and behavior—the Minnesota Adult Tobacco Survey 201031 and the Brief Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult.32

Survey questions assessed cigarette use, nicotine physical dependence, social norms, perceived risks and benefits, and smoking cessation beliefs and behaviors. Questions were slightly reworded to address not only the use of traditional cigarettes, but the use of e-cigarettes, as well. Ultimately, each participant answered a similarly-worded set of questions for both regular and e-cigarettes. Dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes was also assessed. Participants self-reported all data and survey responses on an electronic tablet and received a $10 (cash or gift card) incentive. This project was reviewed and approved by the Springfield Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects.

Stratification of results. Race was dichotomized into white and non-white. Education was stratified into 3 categories: up to and including high school graduation, some college but not a Bachelor’s degree, and Bachelor’s degree and above. Income was divided as being ≤$20,000 or >$20,000, and age was split into 2 groups by the median value. Analyses included descriptions of participant demographics, dual use status, measures of nicotine physical dependence, quit attempts, and e-cigarette use motivations. Bivariate relationships between dual use status and demographic characteristics, nicotine physical dependence, and smoking cessation beliefs were analyzed by chi-square (categorical variables) and ANOVA (continuous/Likert variables).

Multivariable logistic regression modeling of the demographic variables and dual use status (cigarette smoker only vs dual user) was performed to predict 3 factors: number of cigarettes smoked per day (≤10 vs 11+); time to first cigarette (≤30 vs 31+ minutes from waking); and perceived likelihood of quit attempt success (very/somewhat likely vs very/somewhat unlikely). Multivariable models examining the reasons for dual use included the demographic, nicotine physical dependence, and cessation belief items described previously.

RESULTS

Of 309 total survey participants (Fair=288; Race=12; Email=9), there were 235 current cigarette smokers consisting of 79 who smoked only cigarettes (smokers); 122 who used both cigarettes and e-cigarettes (dual users); and 34 former e-cigarette users. Only smokers and dual users were included in this analysis (N=201, although for the purposes of TABLE 1, N=200 or 199 because at least one participant did not provide answers to all of the questions). Approximately 51% of the smokers were male, 78% were white, 12% were 4-year college graduates, and 57% reported incomes >$20,000. The mean age was 37.7 years (SD=14.4); 50% of respondents were <35 years of age. Dual users did not vary significantly from smokers in terms of gender, age, education, or income (all P>.05). However, a greater proportion of whites vs non-whites were dual users (54.9% vs 42.3%; P=.035).

Click here to see an enlarged version of the table.

No big quit differences. Bivariate analyses revealed that dual users were no more likely than smokers to have attempted to quit smoking within the past year (X2=2.3; P=.14), consider quitting in the next one or 6 months (X2=1.1; P=.34), or differ in perceived likelihood of cessation success (X2=0.0; P=1.00). The proportion of dual users who smoked 11+ cigarettes per day did not differ from that of cigarette smokers for the group as a whole or when the group was stratified by gender, income, education, or age. However, among non-whites, dual users smoked fewer cigarettes than cigarette smokers (TABLE 1).

Predicting physical dependence. Significant differences also were observed regarding the timing of the first cigarette of the day, with dual users approximately 3 times more likely than smokers to smoke within 30 minutes of awakening (80% vs 54.4%; OR=3.3; 95% CI, 1.8-6.3), and this difference was upheld among males, females, whites, those with an income >$20,000, those with a high school education or less and those with some college education, and age >34 years. There was no association, however, between dual use and perceived likelihood of quit success.

We then performed multivariable logistic modeling on dual users to determine which variables might predict 3 measures of physical dependence: number of cigarettes smoked per day (≤10 vs 11+), time between waking and smoking the first cigarette of the day (≤30 vs 31+ minutes), and perceived likelihood of cessation success (TABLE 2). Male gender (OR=3.4; 95% CI, 1.8-6.5) and white race (OR=4.4; 95% CI, 1.9-10.1) were significant for predicting smoking 11+ cigarettes a day, while dual use status was insignificant (P=.104). Regarding time to first cigarette, only dual use was significant (OR=3.1; 95% CI, 1.6-5.9), with dual users approximately 3 times more likely than smokers to have their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking. No variables were significant in predicting perceived likelihood of quit success.

Reasons for dual use. We examined reasons for dual use with the question: Do you use e-cigarettes to reduce your regular tobacco use? Here, 79.5% of smokers reported using e-cigarettes to quit smoking or reduce the number of cigarettes smoked.

A multivariable polynomial logistic regression that included only dual users was performed to examine which variables might predict use for tobacco cessation (“trying to quit smoking”) vs reduction in smoking intensity (“trying to reduce the number of regular cigarettes I smoke per day”) vs no change (“use the same amount of tobacco as always”) (TABLE 2). Whites were approximately 6 times more likely than non-whites to indicate they engage in dual use to try to quit smoking (OR=6.0; 95% CI, 1.1-32.9). Males and people with lower incomes were much less likely to indicate they engaged in dual use to try to reduce the number of regular cigarettes smoked than females or those with higher incomes (OR=0.2; 95% CI, 0.1-0.8 and OR=0.1, 95% CI, 0.0-0.5, respectively). No other demographic variables or measures of nicotine physical dependence were significantly different between dual users and smokers.

Click here to see an enlarged version of the table.

DISCUSSION

E-cigarettes are used by approximately half of smokers (52%), which is much higher than that reported by Delnevo, et al, in their analysis of the National Health Interview Study.33 There, prevalence of dual use of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes ranged from 3.4% to 12.7%. This substantial difference raises important questions regarding study population characterization. Were participants in our study representative of central Illinois, state fair attendees, or the agricultural profession? Further work to identify this group with an increased propensity for dual use will assist clinicians in developing appropriate intervention strategies.

Dual use in our study did not vary by many customary demographic variables. Nor was it associated with different rates of past or future quit attempts or perceived ability to successfully quit if quitting was attempted. These factors—high rates of dual use and insignificant effect on quit attempts—may have implications for local physicians counseling patients who smoke.

In our study, the majority of smokers already use e-cigarettes, and this does not seem to increase their ability/likelihood to quit smoking. Further, dual use did not seem to be associated with overall cigarette consumption; males and white participants smoked more cigarettes than females and non-whites. But dual use was associated with a measure of increased nicotine physical dependence (earlier first cigarette of the day). As a result, physicians may want to think twice before recommending e-cigarette use as a means of smoking cessation.

In addition to the high prevalence of e-cigarette use among smokers, a number of other interesting findings surfaced that run counter to some of the current literature. First, dual users are no more likely than smokers to have tried to quit in the past or to try to quit in the future.21,22,34 It could be that for the relatively small geographical area from which our participants were recruited (central Illinois; ~77% of participants from Sangamon County alone), the local context and culture of smoking differs from that associated with participants in other studies, who were mostly recruited from national and regional online surveys. However, there is no a priori reason to suspect Sangamon County is especially different, as it is quite similar to Illinois as a whole by many measures (eg, percentage rural: 14.1% vs 11.5%; percentage black (only): 12.4% vs 14.7%; education to at least a Bachelor’s degree: 33.0% vs 31.9%; and median household income: $55,565 vs $57,166).30

While we found that dual users did have one measure of increased nicotine physical dependence, the total number of cigarettes consumed per day was not significantly different from that of smokers.23-25 This is contrary to another study of nicotine physical dependence, but, unlike that study, we did not assess length of time of concurrent use.35 There is much uncertainty surrounding the issue of nicotine physical dependence and e-cigarette use, largely because the level of nicotine delivered by various e-products varies significantly.36

Cross-sectional nature, small sample size limit utility of data

There are significant limitations to this study, including the cross-sectional nature of the data, the small sample size, the use of self-report, and the limited scope of recruitment. The relatively small sample size limits our ability to observe small differences and effect sizes. However, small differences often lack practical significance. Finally, participation was limited to those attending a state fair or a local sporting event and those employed by a local medical school. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to populations outside central Illinois. On the other hand, the very low income sample recruited from the Midwestern US, which is underrepresented in prior e-cigarette research, might represent some of the strengths of this work.

Future investigations. Future studies should more closely examine e-cigarette use prevalence on smaller geographic scales and especially in rural areas where there is a paucity of research. As the majority of our respondents came from a single county in central Illinois, one has to ask the questions, “Is this a ‘hot spot’ for e-cigarette use?" And "Do other rural areas experience similar use?” It may be important to know if national surveys are sensitive enough to observe significant local variations. Research also should examine how e-cigarette use and the influence of local culture vary across wider areas.

Several specific areas of study would help to inform policy and intervention development. For example, is tobacco cigarette quit success impacted by concurrent e-cigarette use? While our study showed no difference in past or possible future quit attempts among dual users as compared with smokers, we did not assess actual quit success, and multiple participants in our study anecdotally described using e-cigarettes to successfully quit smoking.

In the end, the rapid increase in the use of e-cigarettes has the potential to significantly alter the landscape of nicotine physical dependence, and local culture and other influences are likely associated with use patterns.

CORRESPONDENCE

Wiley D. Jenkins, PhD, MPH, Science Director, Population Health Science Program, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, 201 E. Madison St., Springfield, IL 62794-9664; [email protected].

ABSTRACT

Background Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are often marketed as safe and effective aids for quitting cigarette smoking, but concerns remain that use of e-cigarettes might actually reduce the number of quit attempts. To address these issues, we characterized the utilization and demographic correlates of dual use of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes (referred to here as simply “cigarettes”) among smokers in a rural population of Illinois.

Methods The majority of survey participants were recruited from the 2014 Illinois State Fair and from another event—the Springfield Mile (a motorcycle racing event)—in Springfield, Ill. Survey questions explored participant demographics and cigarette and e-cigarette use history.

Results Of 201 total cigarette smokers, 79 smoked only tobacco cigarettes (smokers), while 122 also used e-cigarettes (dual users). Dual users did not differ significantly from smokers in gender, age, income, or education. Compared to smokers, dual users were more likely to smoke within 30 minutes of awakening (odds ratio [OR]=3.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.8-6.3), but did not smoke more cigarettes per day or perceive a greater likelihood of quit success. Non-white dual users smoked fewer cigarettes per day than smokers. In addition, 79.5% of all dual users reported that they were using e-cigarettes to quit smoking or reduce the number of cigarettes smoked, and white respondents were 6 times more likely than non-whites to use e-cigarettes for ‘trying to quit smoking’ (OR=6.0; 95% CI, 1.1-32.9). Males and respondents with lower income were less likely to say they were using e-cigarettes to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked than females or participants with higher income (OR=0.2; 95% CI, 0.1-0.8 and OR=0.1; 95% CI, 0.0-0.5, respectively).

Conclusions E-cigarettes may significantly alter the landscape of nicotine physical dependence, and local influences likely are associated with use patterns. Future research should continue to examine whether dual use of traditional and electronic cigarettes impacts smoking cessation, and clinicians should be aware that local norms may create differences from national level data.

Approximately 21% of US adults use tobacco products at least occasionally.1 Although smoking prevalence has declined in recent years (from 21% in 2005 to 18% in 2013), it remains high among certain groups (eg, males and those with a high school education or less).2 As we know, the health burden of smoking—as a cause of death from cancer, pulmonary disease, and heart disease—is substantial,3,4 and rural areas experience a significantly higher prevalence of smoking compared to urban areas.2,5,6

However, it is unknown if the context and habits surrounding tobacco use in rural and/or Midwestern areas are similar to those of urban or nationally-representative populations. For example, while many urban residents may encounter a multitude of media messages encouraging smoking cessation resulting in less community acceptance of smoking, rural residents may be exposed to substantially fewer messages (eg, no city bus signs, billboards, subway posters, etc.) and the community may be more accommodating and tolerant of smoking.

Do e-cigarettes increase cigarette smoking?

Public health professionals are concerned about the increased use of e-cigarettes, particularly among young people, and whether this use increases the likelihood that individuals will start smoking tobacco cigarettes.7(Throughout this paper, we will use “cigarettes” and “smoking” to refer to the use of traditional tobacco cigarettes.) A recent study found that adolescents who used electronic nicotine delivery systems were twice as likely as non-users to have tried cigarettes in the past year.8

An onslaught of advertising. There are also concerns that e-cigarettes may serve to ‘renormalize’ nicotine addiction, in part through large-scale advertising, which was seen by nearly 70% of the participants in the 2014 National Youth Tobacco Survey.9 Largely as a result of that advertising, e-cigarette sales exceed $1.7 billion in the United States alone.10 With 15% of all US adults having ever tried electronic nicotine delivery systems and more than half (52%) of smokers having done so, questions regarding their health impact cannot be taken lightly.11

Do e-cigarettes help people quit smoking? E-cigarettes are often marketed as a safe and effective means for quitting cigarette smoking.12-14 (See "E-cigarettes: How "safe" are they?") Nearly two-thirds of physicians report being asked about e-cigarettes by their patients and approximately one-third of physicians recommend using them as a smoking cessation aid.15

Claims regarding the usefulness of e-cigarettes in smoking cessation, however, have not been substantiated by high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In fact, no RCTs have shown them to be safer or more effective than cessation treatments currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.16,17

Two studies reflect the conflicting data that are currently available. One small study found intensive e-cigarette users were 6 times more likely than non-users/triers to report successful smoking cessation.18 However, researchers surveying callers of a cigarette quit line found that smokers who used e-cigarettes (dual users) were less likely to quit smoking than non-users.19

The lack of good-quality data substantiates the concern that dual use might discourage quitting by normalizing cigarette use and reducing perceptions of harm.20,21 Dual use may also hamper smoking cessation efforts by increasing nicotine physical dependence and associated withdrawal symptoms when trying to quit.22 And finally, dual use may expose users to more carcinogens and toxins than those who use only one product, and the average number of cigarettes smoked per day may be significantly higher among dual users.23

Unique demographic factors at work? Finally, the social and community context within which smoking occurs, and the prevalence of smoking-associated demographic risk factors, may vary significantly between rural and urban areas and between seemingly similar rural areas.24-27 Few studies have examined differences in e-cigarette use between rural and urban areas. Those that have are contradictory, reporting that rural residents use e-cigarettes both more and less than their urban peers,28,29 but many of these studies were conducted outside the United States, where the context and norms associated with smoking and e-cigarette use likely vary.

For these reasons, we sought to examine e-cigarette use among residents of Illinois, the nation’s fifth largest state and one with a rural population exceeding 1.5 million.30 We compared dual users of e-cigarettes and cigarettes to smokers of cigarettes only in terms of demographic characteristics, nicotine physical dependence, and smoking cessation beliefs, and explored dual smokers' reasons for using both types of cigarettes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A survey was fielded during August and September 2014 in Springfield, Ill. To obtain responses, a booth was set up at both the Illinois State Fair and the Springfield Mile (a motorcycle racing event), and participants were recruited via direct solicitation by project staff. This was supplemented by an email invitation to all employees of the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. The 2 venues and the email strategy were chosen because they draw from a large area of central and southern Illinois and were convenient to the location of the study team. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were ≥18 years of age and used any tobacco product or e-cigarettes. Survey elements were derived from 2 national surveys of health and behavior—the Minnesota Adult Tobacco Survey 201031 and the Brief Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult.32

Survey questions assessed cigarette use, nicotine physical dependence, social norms, perceived risks and benefits, and smoking cessation beliefs and behaviors. Questions were slightly reworded to address not only the use of traditional cigarettes, but the use of e-cigarettes, as well. Ultimately, each participant answered a similarly-worded set of questions for both regular and e-cigarettes. Dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes was also assessed. Participants self-reported all data and survey responses on an electronic tablet and received a $10 (cash or gift card) incentive. This project was reviewed and approved by the Springfield Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects.

Stratification of results. Race was dichotomized into white and non-white. Education was stratified into 3 categories: up to and including high school graduation, some college but not a Bachelor’s degree, and Bachelor’s degree and above. Income was divided as being ≤$20,000 or >$20,000, and age was split into 2 groups by the median value. Analyses included descriptions of participant demographics, dual use status, measures of nicotine physical dependence, quit attempts, and e-cigarette use motivations. Bivariate relationships between dual use status and demographic characteristics, nicotine physical dependence, and smoking cessation beliefs were analyzed by chi-square (categorical variables) and ANOVA (continuous/Likert variables).

Multivariable logistic regression modeling of the demographic variables and dual use status (cigarette smoker only vs dual user) was performed to predict 3 factors: number of cigarettes smoked per day (≤10 vs 11+); time to first cigarette (≤30 vs 31+ minutes from waking); and perceived likelihood of quit attempt success (very/somewhat likely vs very/somewhat unlikely). Multivariable models examining the reasons for dual use included the demographic, nicotine physical dependence, and cessation belief items described previously.

RESULTS

Of 309 total survey participants (Fair=288; Race=12; Email=9), there were 235 current cigarette smokers consisting of 79 who smoked only cigarettes (smokers); 122 who used both cigarettes and e-cigarettes (dual users); and 34 former e-cigarette users. Only smokers and dual users were included in this analysis (N=201, although for the purposes of TABLE 1, N=200 or 199 because at least one participant did not provide answers to all of the questions). Approximately 51% of the smokers were male, 78% were white, 12% were 4-year college graduates, and 57% reported incomes >$20,000. The mean age was 37.7 years (SD=14.4); 50% of respondents were <35 years of age. Dual users did not vary significantly from smokers in terms of gender, age, education, or income (all P>.05). However, a greater proportion of whites vs non-whites were dual users (54.9% vs 42.3%; P=.035).

Click here to see an enlarged version of the table.

No big quit differences. Bivariate analyses revealed that dual users were no more likely than smokers to have attempted to quit smoking within the past year (X2=2.3; P=.14), consider quitting in the next one or 6 months (X2=1.1; P=.34), or differ in perceived likelihood of cessation success (X2=0.0; P=1.00). The proportion of dual users who smoked 11+ cigarettes per day did not differ from that of cigarette smokers for the group as a whole or when the group was stratified by gender, income, education, or age. However, among non-whites, dual users smoked fewer cigarettes than cigarette smokers (TABLE 1).

Predicting physical dependence. Significant differences also were observed regarding the timing of the first cigarette of the day, with dual users approximately 3 times more likely than smokers to smoke within 30 minutes of awakening (80% vs 54.4%; OR=3.3; 95% CI, 1.8-6.3), and this difference was upheld among males, females, whites, those with an income >$20,000, those with a high school education or less and those with some college education, and age >34 years. There was no association, however, between dual use and perceived likelihood of quit success.

We then performed multivariable logistic modeling on dual users to determine which variables might predict 3 measures of physical dependence: number of cigarettes smoked per day (≤10 vs 11+), time between waking and smoking the first cigarette of the day (≤30 vs 31+ minutes), and perceived likelihood of cessation success (TABLE 2). Male gender (OR=3.4; 95% CI, 1.8-6.5) and white race (OR=4.4; 95% CI, 1.9-10.1) were significant for predicting smoking 11+ cigarettes a day, while dual use status was insignificant (P=.104). Regarding time to first cigarette, only dual use was significant (OR=3.1; 95% CI, 1.6-5.9), with dual users approximately 3 times more likely than smokers to have their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking. No variables were significant in predicting perceived likelihood of quit success.

Reasons for dual use. We examined reasons for dual use with the question: Do you use e-cigarettes to reduce your regular tobacco use? Here, 79.5% of smokers reported using e-cigarettes to quit smoking or reduce the number of cigarettes smoked.

A multivariable polynomial logistic regression that included only dual users was performed to examine which variables might predict use for tobacco cessation (“trying to quit smoking”) vs reduction in smoking intensity (“trying to reduce the number of regular cigarettes I smoke per day”) vs no change (“use the same amount of tobacco as always”) (TABLE 2). Whites were approximately 6 times more likely than non-whites to indicate they engage in dual use to try to quit smoking (OR=6.0; 95% CI, 1.1-32.9). Males and people with lower incomes were much less likely to indicate they engaged in dual use to try to reduce the number of regular cigarettes smoked than females or those with higher incomes (OR=0.2; 95% CI, 0.1-0.8 and OR=0.1, 95% CI, 0.0-0.5, respectively). No other demographic variables or measures of nicotine physical dependence were significantly different between dual users and smokers.

Click here to see an enlarged version of the table.

DISCUSSION

E-cigarettes are used by approximately half of smokers (52%), which is much higher than that reported by Delnevo, et al, in their analysis of the National Health Interview Study.33 There, prevalence of dual use of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes ranged from 3.4% to 12.7%. This substantial difference raises important questions regarding study population characterization. Were participants in our study representative of central Illinois, state fair attendees, or the agricultural profession? Further work to identify this group with an increased propensity for dual use will assist clinicians in developing appropriate intervention strategies.

Dual use in our study did not vary by many customary demographic variables. Nor was it associated with different rates of past or future quit attempts or perceived ability to successfully quit if quitting was attempted. These factors—high rates of dual use and insignificant effect on quit attempts—may have implications for local physicians counseling patients who smoke.

In our study, the majority of smokers already use e-cigarettes, and this does not seem to increase their ability/likelihood to quit smoking. Further, dual use did not seem to be associated with overall cigarette consumption; males and white participants smoked more cigarettes than females and non-whites. But dual use was associated with a measure of increased nicotine physical dependence (earlier first cigarette of the day). As a result, physicians may want to think twice before recommending e-cigarette use as a means of smoking cessation.

In addition to the high prevalence of e-cigarette use among smokers, a number of other interesting findings surfaced that run counter to some of the current literature. First, dual users are no more likely than smokers to have tried to quit in the past or to try to quit in the future.21,22,34 It could be that for the relatively small geographical area from which our participants were recruited (central Illinois; ~77% of participants from Sangamon County alone), the local context and culture of smoking differs from that associated with participants in other studies, who were mostly recruited from national and regional online surveys. However, there is no a priori reason to suspect Sangamon County is especially different, as it is quite similar to Illinois as a whole by many measures (eg, percentage rural: 14.1% vs 11.5%; percentage black (only): 12.4% vs 14.7%; education to at least a Bachelor’s degree: 33.0% vs 31.9%; and median household income: $55,565 vs $57,166).30

While we found that dual users did have one measure of increased nicotine physical dependence, the total number of cigarettes consumed per day was not significantly different from that of smokers.23-25 This is contrary to another study of nicotine physical dependence, but, unlike that study, we did not assess length of time of concurrent use.35 There is much uncertainty surrounding the issue of nicotine physical dependence and e-cigarette use, largely because the level of nicotine delivered by various e-products varies significantly.36

Cross-sectional nature, small sample size limit utility of data

There are significant limitations to this study, including the cross-sectional nature of the data, the small sample size, the use of self-report, and the limited scope of recruitment. The relatively small sample size limits our ability to observe small differences and effect sizes. However, small differences often lack practical significance. Finally, participation was limited to those attending a state fair or a local sporting event and those employed by a local medical school. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to populations outside central Illinois. On the other hand, the very low income sample recruited from the Midwestern US, which is underrepresented in prior e-cigarette research, might represent some of the strengths of this work.

Future investigations. Future studies should more closely examine e-cigarette use prevalence on smaller geographic scales and especially in rural areas where there is a paucity of research. As the majority of our respondents came from a single county in central Illinois, one has to ask the questions, “Is this a ‘hot spot’ for e-cigarette use?" And "Do other rural areas experience similar use?” It may be important to know if national surveys are sensitive enough to observe significant local variations. Research also should examine how e-cigarette use and the influence of local culture vary across wider areas.

Several specific areas of study would help to inform policy and intervention development. For example, is tobacco cigarette quit success impacted by concurrent e-cigarette use? While our study showed no difference in past or possible future quit attempts among dual users as compared with smokers, we did not assess actual quit success, and multiple participants in our study anecdotally described using e-cigarettes to successfully quit smoking.

In the end, the rapid increase in the use of e-cigarettes has the potential to significantly alter the landscape of nicotine physical dependence, and local culture and other influences are likely associated with use patterns.

CORRESPONDENCE

Wiley D. Jenkins, PhD, MPH, Science Director, Population Health Science Program, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, 201 E. Madison St., Springfield, IL 62794-9664; [email protected].

1. Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2012-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:542-547.

2. Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1108-1112.

3. Siegel RL, Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, et al. Deaths due to cigarette smoking for 12 smoking-related cancers in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1574-1576.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/index.html. Accessed January 22, 2014.

5. Gamm LD, Hutchison LL, Dabney BJ, et al, eds. (2003). Rural Healthy People 2010: A companion document to Healthy People 2010. Volume 2. College Station, TX: The Texas A&M University System Health Science Center, School of Rural Public Health, Southwest Rural Health Research Center.

6. Doescher MP, Jackson JE, Jerant A, et al. Prevalence and trends in smoking: a national rural study. J Rural Health. 2006;22:112-118.

7. Bunnell RE, Agaku IT, Arrazola RA, et al. Intentions to smoke cigarettes among never-smoking US middle and high school electronic cigarette users: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:228-235.

8. Cardenas VM, Evans VL, Balamurugan A, et al. Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems and recent initiation of smoking among US youth. Int J Public Health. 2016;61:237-241.

9. Auf R, Trepka MJ, Cano MA, et al. Electronic cigarettes: the renormalisation of nicotine use. BMJ. 2016;352:i425.

10. CNBC. E-cigarette sales are smoking hot, set to hit $1.7 billion. Available at: http://www.cnbc.com/id/100991511. Accessed April 5, 2016.

11. Weaver SR, Majeed BA, Pechacek TF, et al. Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems and other tobacco products among USA adults, 2014: results from a national survey. Int J Public Health. 2016;61:177-188.

12. Richardson A, Ganz O, Vallone D. Tobacco on the web: surveillance and characterisation of online tobacco and e-cigarette advertising. Tob Control. 2015;24:341-347.

13. Paek HJ, Kim S, Hove T, et al. Reduced harm or another gateway to smoking? source, message, and information characteristics of E-cigarette videos on YouTube. J Health Commun. 2014;19:545-560.

14. Kim AE, Arnold KY, Makarenko O. E-cigarette advertising expenditures in the U.S., 2011-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:409-412.

15. Steinberg MB, Giovenco DP, Delnevo CD. Patient-physician communication regarding electronic cigarettes. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:96-98.

16. Gualano MR, Passi S, Bert F, et al. Electronic cigarettes: assessing the efficacy and the adverse effects through a systematic review of published studies. J Public Health (Oxf). 2015:37:488-497.

17. U.S. National Institutes of Health. ClinicalTrials.gov. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=%22electronic+cigarette%22&Search=Search. Accessed July 10, 2015.

18. Biener L, Hargraves JL. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use among a population-based sample of adult smokers: association with smoking cessation and motivation to quit. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:127-133.

19. Vickerman KA, Carpenter KM, Altman T, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes among state tobacco cessation quitline callers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1787-1791.

20. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Press Release February 28,2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2013/p0228_electronic_cigarettes.html. Accessed July 8, 2015.

21. Pisinger C. Why public health people are more worried than excited over e-cigarettes. BMC Med. 2014;12:226.

22. Post A, Gilljam H, Rosendahl I, et al. Symptoms of nicotine dependence in a cohort of Swedish youths: a comparison between smokers, smokeless tobacco users and dual tobacco users. Addiction. 2010;105:740-746.

23. Mazurek JM, Syamlal G, King BA, et al; Division of Respiratory Disease Studies, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, CDC. Smokeless tobacco use among working adults—United States, 2005 and 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:477-482.

24. Hutcheson TD, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Understanding smoking cessation in rural communities. J Rural Health. 2008;24:116-124.

25. McMillen R, Breen J, Cosby AG. Rural-urban differences in the social climate surrounding environmental tobacco smoke: a report from the 2002 Social Climate Survey of Tobacco Control. J Rural Health. 2004;20:7-16.

26. Butler KM, Rayens MK, Adkins S, et al. Culturally-specific smoking cessation outreach in a rural community. Public Health Nurs. 2014;31:44-54.

27. Butler KM, Hedgecock S, Record RA, et al. An evidence-based cessation strategy using rural smokers’ experiences with tobacco. Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47:31-43.

28. Hamilton HA, Ferrence R, Boak A, et al. Ever use of nicotine and nonnicotine electronic cigarettes among high school students in Ontario, Canada. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:1212-1218.

29. Goniewicz ML, Zielinska-Danch W. Electronic cigarette use among teenagers and young adults in Poland. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e879-e885.

30. US Census Bureau. 2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. Available at: http://www.census.gov/geo/reference/ua/urban-rural-2010.html. Accessed March 13, 2016.

31. Minnesota Adult Tobacco Survey. Tobacco use in Minnesota: 1999-2014. Available at: http://www.mnadulttobaccosurvey.org/. Accessed April 27, 2016.

32. Rash CJ, Copeland AL. The Brief Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult (BSCQ-A): development of a short form of the SCQ-A. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1633-1643.

33. Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Steinberg MB, et al. Patterns of electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:715-719.

34. Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, et al. Multiple tobacco product use among adults in the United States: cigarettes, cigars, electronic cigarettes, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus. Prev Med. 2014;62:14-19.

35. Etter JF, Eissenberg T. Dependence levels in users of electronic cigarettes, nicotine gums and tobacco cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:68-75.

36. Cobb CO, Hendricks PS, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes and nicotine dependence: evolving products, evolving problems. BMC Med. 2015;13:119.

1. Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2012-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:542-547.

2. Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1108-1112.

3. Siegel RL, Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, et al. Deaths due to cigarette smoking for 12 smoking-related cancers in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1574-1576.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/index.html. Accessed January 22, 2014.

5. Gamm LD, Hutchison LL, Dabney BJ, et al, eds. (2003). Rural Healthy People 2010: A companion document to Healthy People 2010. Volume 2. College Station, TX: The Texas A&M University System Health Science Center, School of Rural Public Health, Southwest Rural Health Research Center.

6. Doescher MP, Jackson JE, Jerant A, et al. Prevalence and trends in smoking: a national rural study. J Rural Health. 2006;22:112-118.

7. Bunnell RE, Agaku IT, Arrazola RA, et al. Intentions to smoke cigarettes among never-smoking US middle and high school electronic cigarette users: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:228-235.

8. Cardenas VM, Evans VL, Balamurugan A, et al. Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems and recent initiation of smoking among US youth. Int J Public Health. 2016;61:237-241.

9. Auf R, Trepka MJ, Cano MA, et al. Electronic cigarettes: the renormalisation of nicotine use. BMJ. 2016;352:i425.

10. CNBC. E-cigarette sales are smoking hot, set to hit $1.7 billion. Available at: http://www.cnbc.com/id/100991511. Accessed April 5, 2016.

11. Weaver SR, Majeed BA, Pechacek TF, et al. Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems and other tobacco products among USA adults, 2014: results from a national survey. Int J Public Health. 2016;61:177-188.

12. Richardson A, Ganz O, Vallone D. Tobacco on the web: surveillance and characterisation of online tobacco and e-cigarette advertising. Tob Control. 2015;24:341-347.

13. Paek HJ, Kim S, Hove T, et al. Reduced harm or another gateway to smoking? source, message, and information characteristics of E-cigarette videos on YouTube. J Health Commun. 2014;19:545-560.

14. Kim AE, Arnold KY, Makarenko O. E-cigarette advertising expenditures in the U.S., 2011-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:409-412.

15. Steinberg MB, Giovenco DP, Delnevo CD. Patient-physician communication regarding electronic cigarettes. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:96-98.

16. Gualano MR, Passi S, Bert F, et al. Electronic cigarettes: assessing the efficacy and the adverse effects through a systematic review of published studies. J Public Health (Oxf). 2015:37:488-497.

17. U.S. National Institutes of Health. ClinicalTrials.gov. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=%22electronic+cigarette%22&Search=Search. Accessed July 10, 2015.

18. Biener L, Hargraves JL. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use among a population-based sample of adult smokers: association with smoking cessation and motivation to quit. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:127-133.

19. Vickerman KA, Carpenter KM, Altman T, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes among state tobacco cessation quitline callers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1787-1791.

20. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Press Release February 28,2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2013/p0228_electronic_cigarettes.html. Accessed July 8, 2015.

21. Pisinger C. Why public health people are more worried than excited over e-cigarettes. BMC Med. 2014;12:226.

22. Post A, Gilljam H, Rosendahl I, et al. Symptoms of nicotine dependence in a cohort of Swedish youths: a comparison between smokers, smokeless tobacco users and dual tobacco users. Addiction. 2010;105:740-746.

23. Mazurek JM, Syamlal G, King BA, et al; Division of Respiratory Disease Studies, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, CDC. Smokeless tobacco use among working adults—United States, 2005 and 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:477-482.

24. Hutcheson TD, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Understanding smoking cessation in rural communities. J Rural Health. 2008;24:116-124.

25. McMillen R, Breen J, Cosby AG. Rural-urban differences in the social climate surrounding environmental tobacco smoke: a report from the 2002 Social Climate Survey of Tobacco Control. J Rural Health. 2004;20:7-16.

26. Butler KM, Rayens MK, Adkins S, et al. Culturally-specific smoking cessation outreach in a rural community. Public Health Nurs. 2014;31:44-54.

27. Butler KM, Hedgecock S, Record RA, et al. An evidence-based cessation strategy using rural smokers’ experiences with tobacco. Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47:31-43.

28. Hamilton HA, Ferrence R, Boak A, et al. Ever use of nicotine and nonnicotine electronic cigarettes among high school students in Ontario, Canada. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:1212-1218.

29. Goniewicz ML, Zielinska-Danch W. Electronic cigarette use among teenagers and young adults in Poland. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e879-e885.

30. US Census Bureau. 2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. Available at: http://www.census.gov/geo/reference/ua/urban-rural-2010.html. Accessed March 13, 2016.

31. Minnesota Adult Tobacco Survey. Tobacco use in Minnesota: 1999-2014. Available at: http://www.mnadulttobaccosurvey.org/. Accessed April 27, 2016.

32. Rash CJ, Copeland AL. The Brief Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult (BSCQ-A): development of a short form of the SCQ-A. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1633-1643.

33. Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Steinberg MB, et al. Patterns of electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:715-719.

34. Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, et al. Multiple tobacco product use among adults in the United States: cigarettes, cigars, electronic cigarettes, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus. Prev Med. 2014;62:14-19.

35. Etter JF, Eissenberg T. Dependence levels in users of electronic cigarettes, nicotine gums and tobacco cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:68-75.

36. Cobb CO, Hendricks PS, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes and nicotine dependence: evolving products, evolving problems. BMC Med. 2015;13:119.