User login

In reply: Insulin before surgery

In Reply: We appreciate the kind words of Drs. Ditch and Moore, as well as their opinion.

Our article was intentionally brief—a 1-Minute Consult—and so could not cover all specific situations we encounter in clinical practice. We meant only to provide a general approach in this matter.

Quite often before surgery, patients receive less basal insulin than needed, or none at all, rather than too much. It has to be borne in mind that perioperative hyperglycemia—not just hypoglycemia—is linked with poor outcomes in cardiac1 and noncardiac surgery.2,3

Through our scenarios and suggestions, we have taken steps to err on the side of preventing hypoglycemia while averting hyperglycemia, at the same time making it easy to calculate the dose. In a scenario in which the basal insulin dose is about the same as the total of the prandial boluses, we have not yet seen evidence that raises concern for hypoglycemia, maybe because many of the patients with type 2 diabetes seen in our institution for surgery take, in addition to insulin, oral agents or noninsulin injections (which are appropriately withheld before surgery), and have suboptimal glycemic control on their home regimen. But if a physician has concerns for hypoglycemia, a dose reduction should be made.

There were some differences between the RABBIT 2 trial in medical patients4 and the RABBIT 2 Surgery trial5 that would make the results not completely comparable. In RABBIT 2, the medical patients included were on diet alone or any combination of oral antidiabetic agents (not on insulin), and they were started on a total daily dose of insulin of either 0.4 or 0.5 U/kg/day, depending on the glucose level. In RABBIT 2 Surgery, patients who were on insulin at home with a total daily dose of 0.4 U/kg or less were also included, and the starting daily dose of insulin was 0.5 U/kg (unless they were older or had a high serum creatinine).

In view of all the above, we agree with Drs. Ditch and Moore that if there is concern for hypoglycemia, the clinician should reduce the insulin dose in the manner that evidence from the local practice suggests, without causing undue hyperglycemia and postsurgical complications.

- Furnary AP, Gao G, Grunkemeier GL, et al. Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003; 125:1007–1021.

- King JT, Goulet JL, Perkal MF, Rosenthal RA. Glycemic control and infections in patients with diabetes undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Surg 2011; 253:158–165.

- Frisch A, Chandra P, Smiley D, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of hyperglycemia in the perioperative period in noncardiac surgery. Diabetes Care 2010; 33:1783–1788.

- Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Zisman A, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 trial). Diabetes Care 2007; 30:2181–2186.

- Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Jacobs S, Peng L, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing general surgery (RABBIT 2 surgery). Diabetes Care 2011; 34:256–261.

In Reply: We appreciate the kind words of Drs. Ditch and Moore, as well as their opinion.

Our article was intentionally brief—a 1-Minute Consult—and so could not cover all specific situations we encounter in clinical practice. We meant only to provide a general approach in this matter.

Quite often before surgery, patients receive less basal insulin than needed, or none at all, rather than too much. It has to be borne in mind that perioperative hyperglycemia—not just hypoglycemia—is linked with poor outcomes in cardiac1 and noncardiac surgery.2,3

Through our scenarios and suggestions, we have taken steps to err on the side of preventing hypoglycemia while averting hyperglycemia, at the same time making it easy to calculate the dose. In a scenario in which the basal insulin dose is about the same as the total of the prandial boluses, we have not yet seen evidence that raises concern for hypoglycemia, maybe because many of the patients with type 2 diabetes seen in our institution for surgery take, in addition to insulin, oral agents or noninsulin injections (which are appropriately withheld before surgery), and have suboptimal glycemic control on their home regimen. But if a physician has concerns for hypoglycemia, a dose reduction should be made.

There were some differences between the RABBIT 2 trial in medical patients4 and the RABBIT 2 Surgery trial5 that would make the results not completely comparable. In RABBIT 2, the medical patients included were on diet alone or any combination of oral antidiabetic agents (not on insulin), and they were started on a total daily dose of insulin of either 0.4 or 0.5 U/kg/day, depending on the glucose level. In RABBIT 2 Surgery, patients who were on insulin at home with a total daily dose of 0.4 U/kg or less were also included, and the starting daily dose of insulin was 0.5 U/kg (unless they were older or had a high serum creatinine).

In view of all the above, we agree with Drs. Ditch and Moore that if there is concern for hypoglycemia, the clinician should reduce the insulin dose in the manner that evidence from the local practice suggests, without causing undue hyperglycemia and postsurgical complications.

In Reply: We appreciate the kind words of Drs. Ditch and Moore, as well as their opinion.

Our article was intentionally brief—a 1-Minute Consult—and so could not cover all specific situations we encounter in clinical practice. We meant only to provide a general approach in this matter.

Quite often before surgery, patients receive less basal insulin than needed, or none at all, rather than too much. It has to be borne in mind that perioperative hyperglycemia—not just hypoglycemia—is linked with poor outcomes in cardiac1 and noncardiac surgery.2,3

Through our scenarios and suggestions, we have taken steps to err on the side of preventing hypoglycemia while averting hyperglycemia, at the same time making it easy to calculate the dose. In a scenario in which the basal insulin dose is about the same as the total of the prandial boluses, we have not yet seen evidence that raises concern for hypoglycemia, maybe because many of the patients with type 2 diabetes seen in our institution for surgery take, in addition to insulin, oral agents or noninsulin injections (which are appropriately withheld before surgery), and have suboptimal glycemic control on their home regimen. But if a physician has concerns for hypoglycemia, a dose reduction should be made.

There were some differences between the RABBIT 2 trial in medical patients4 and the RABBIT 2 Surgery trial5 that would make the results not completely comparable. In RABBIT 2, the medical patients included were on diet alone or any combination of oral antidiabetic agents (not on insulin), and they were started on a total daily dose of insulin of either 0.4 or 0.5 U/kg/day, depending on the glucose level. In RABBIT 2 Surgery, patients who were on insulin at home with a total daily dose of 0.4 U/kg or less were also included, and the starting daily dose of insulin was 0.5 U/kg (unless they were older or had a high serum creatinine).

In view of all the above, we agree with Drs. Ditch and Moore that if there is concern for hypoglycemia, the clinician should reduce the insulin dose in the manner that evidence from the local practice suggests, without causing undue hyperglycemia and postsurgical complications.

- Furnary AP, Gao G, Grunkemeier GL, et al. Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003; 125:1007–1021.

- King JT, Goulet JL, Perkal MF, Rosenthal RA. Glycemic control and infections in patients with diabetes undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Surg 2011; 253:158–165.

- Frisch A, Chandra P, Smiley D, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of hyperglycemia in the perioperative period in noncardiac surgery. Diabetes Care 2010; 33:1783–1788.

- Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Zisman A, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 trial). Diabetes Care 2007; 30:2181–2186.

- Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Jacobs S, Peng L, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing general surgery (RABBIT 2 surgery). Diabetes Care 2011; 34:256–261.

- Furnary AP, Gao G, Grunkemeier GL, et al. Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003; 125:1007–1021.

- King JT, Goulet JL, Perkal MF, Rosenthal RA. Glycemic control and infections in patients with diabetes undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Surg 2011; 253:158–165.

- Frisch A, Chandra P, Smiley D, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of hyperglycemia in the perioperative period in noncardiac surgery. Diabetes Care 2010; 33:1783–1788.

- Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Zisman A, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 trial). Diabetes Care 2007; 30:2181–2186.

- Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Jacobs S, Peng L, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing general surgery (RABBIT 2 surgery). Diabetes Care 2011; 34:256–261.

How should we manage insulin therapy before surgery?

Continuing at least part of the basal insulin is the reasonable, physiologic approach to controlling glucose levels before surgery in patients with diabetes. The process involves three basic steps:

- Ascertaining the type of diabetes

- Adjusting the basal insulin dosage

- Stopping the prandial insulin.

The steps are the same whether the surgery is major or minor. These recommendations are based on general principles of insulin action, data from large databases of surgical inpatients, and expert clinical experience translated into standardized protocols.1,2

WHY CONTINUE THE INSULIN?

Stopping or decreasing insulin because of a fear of hypoglycemia is not appropriate, as the resulting hyperglycemia can lead to delayed wound healing, wound infection, fluid and electrolyte shifts, diabetic ketoacidosis, and hyperosmolar states.

Insulin inhibits both gluconeogenesis and conversion of glycogen to glucose, processes that occur regardless of food intake. It also inhibits degradation of fats to fatty acids and of fatty acids to ketones. This is why inadequate insulin dosing can lead to uncontrolled hyperglycemia and even ketoacidosis, and thus why long-acting insulin is needed in a fasting state.

STEP 1: ASCERTAIN THE TYPE OF DIABETES

Does the patient have type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and does that even matter?

The type of diabetes should not matter, since ideally the insulin should be dosed the same for both types. However, the consequences of inappropriate insulin management may be different.

Usually, the type of diabetes can be ascertained by the history. If the patient was diagnosed at age 40 or later and was on oral medication for years before insulin was started, then he or she most likely has type 2. If the patient was younger than 40 at the time of diagnosis, was lean, and was started on insulin within a year of diagnosis, then he or she likely has type 1.

If this information is not available or is unreliable and the patient has been on insulin for many years, we recommend viewing the patient as being insulinopenic, ie, not producing enough insulin endogenously and thus requiring insulin at all times.

Though checking for antibody markers of type 1 diabetes might give a more definitive answer, it is not practical before surgery.

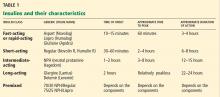

In the setting of surgical stress, withholding the basal insulin preoperatively and just giving a small dose of fast-acting (see Table 1 for the different classes of insulin) or shortacting insulin as part of a sliding scale (ie, insulin given only when the blood glucose reaches a certain high level) can send a patient with type 1 diabetes into diabetic ketoacidosis by the end of the day. This is less likely to occur in a patient with type 2 diabetes with some endogenous insulin secretion.

STEP 2: ADJUST THE BASAL INSULIN

Basal insulin is the insulin that the healthy person’s body produces when fasting. For a diabetic patient already on insulin, basal insulin is insulin injected to prevent ketogenesis, glycogenolysis, and gluconeogenesis in the fasting state.

If the basal insulin is long-acting

Long-acting insulins have a relatively peakless profile and, when properly dosed, should not result in hypoglycemia when a patient is fasting.

Preoperatively, the patient should take it as close as possible to the usual time of injection. This could be at home either at bedtime the night before surgery or the morning of surgery. If there is concern for hypoglycemia, the injection can be given when the patient is at the hospital.

- If the patient does not tend to have hypoglycemic episodes and the total daily basal insulin dose is roughly the same as the total daily mealtime (prandial) dose (eg, 50% basal, 50% prandial ratio), the full dose of basal insulin can be given.3

Example: If the patient is on insulin glargine 30 U at bedtime and insulin lispro 10 U with each meal and does not have hypoglycemic episodes, then insulin glargine 30 U should be taken at bedtime.

- If the patient has hypoglycemic episodes at home, then the basal insulin can be reduced by 25%.3

Example: If the patient is on insulin glargine 30 U at bedtime and insulin glulisine 10 U with each meal (appropriate proportion of doses, similar to the example above) but has hypoglycemic episodes at home on this regimen, then only 22 U of insulin glargine should be taken at bedtime.

- If the patient’s regimen has disproportionately more basal insulin than mealtime insulin, then the total daily doses can be added and half can be given as the basal insulin.

Example: If the patient is on insulin detemir 30 U every morning at 6 am and insulin aspart 6 U with each meal and has no hypoglycemic episodes, then 24 U of insulin detemir should be taken in the morning (ie, half of the total of 30 + 6 + 6 + 6).

- In the less common scenario of diabetes managed only with basal insulin (no other diabetes injections or oral agents), then half of the dose can be given.

- If the patient is on twice-daily long-acting basal insulin, then both the dose the night before surgery and the dose the morning of surgery should be adjusted.

If the basal insulin is intermediate-acting

The intermediate-acting insulin neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) is usually given twice a day because of its profile (Table 1).

- On the night before surgery, the full dose of NPH insulin should be taken, unless the patient will now skip a nighttime meal because of taking nothing by mouth, in which case the dose can be decreased by 25%.1

- On the morning of surgery, since the patient will be skipping breakfast and probably also lunch, the dose should be reduced by 50%.3,4

Special situation: Premixed insulins

Premixed insulins (70/30, 75/25) are a combination of intermediate-acting insulin and either fast-acting or short-acting insulin. In other words, they are combinations of basal and prandial insulin. Their use is thus not ideal in the preoperative period. There are two options in these situations.

One option is to switch to a regimen that includes long-acting insulin. If the patient is admitted for surgery, then the hospital staff can change the insulin regimen to long-acting basal insulin. A quick formula for conversion is to add all the premixed insulin doses and give half as basal insulin on the morning of surgery, similar to the scenario above for the patient with long-acting basal insulin that was out of proportion to the prandial insulin injections.

For example, if the usual regimen is insulin 70/30 NPH/Regular, 60 U with breakfast, 30 U with dinner, then the patient can take 45 U of insulin glargine (which is half of 60 + 30) in the morning or evening before surgery.

Another option is to adjust the dose of pre-mixed insulin. Sometimes it is not feasible or economical to change the patient’s premixed insulin just before surgery. In these situations, the patient can take half of the morning dose, followed by dextrose-containing intravenous fluids and blood glucose checks.

We recommend preoperatively giving at least part of the patient’s previous basal insulin, regardless of the type of diabetes, the type of surgery, or the fasting period.

STEP 3: STOP THE PRANDIAL INSULIN

Prandial insulin—given before each meal to cover the carbohydrates to be consumed—should be stopped the morning of surgery.3,4

WHAT ABOUT SLIDING SCALE INSULIN?

Using a sliding scale alone has no known benefit. Although it can be a quick fix to correct a high glucose level, it should be added to the basal insulin and not used as the sole insulin therapy. If a sliding scale is used, fast-acting insulin (aspart, glulisine, lispro) is preferred over regular insulin because of the more rapid onset and shorter duration of action.

Patients already using a supplemental insulin scale can apply it to correct a blood glucose above 200 mg/dL on the morning of surgery.

MAINTENANCE FLUIDS

As long as glucose levels are not very elevated (ie, > 200 mg/dL), after 12 hours on a nothing-by-mouth regimen, provide dextrose in the IV fluid to prevent hypoglycemia (eg, the patient received long-acting insulin and the glucose levels are running low) or to prevent starvation ketosis, which may result in ketones in the blood or urine. We recommend 5% dextrose in half-normal (0.45%) saline at 50 to 75 mL/hour as maintenance fluid; the infusion rate should be lower if fluid overload is a concern.

POSTOPERATIVE INSULIN MANAGEMENT

Once patients are discharged and can go back to their previous routine, they can restart their usual insulin regimen the same evening. The prandial insulin will be resumed when the regular diet is reintroduced, and the doses will be adjusted according to food intake.

- Joshi GP, Chung F, Vann MA, et al; Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia. Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia consensus statement on perioperative blood glucose management in diabetic patients undergoing ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 2010; 111:1378–1387.

- DiNardo M, Donihi AC, Forte P, Gieraltowski L, Korytkowski M. Standardized glycemic management and perioperative glycemic outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus who undergo same-day surgery. Endocr Pract 2011; 17:404–411.

- Vann MA. Perioperative management of ambulatory surgical patients with diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009; 22:718–724.

- Meneghini LF. Perioperative management of diabetes: translating evidence into practice. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76(suppl 4):S53–S59.

Continuing at least part of the basal insulin is the reasonable, physiologic approach to controlling glucose levels before surgery in patients with diabetes. The process involves three basic steps:

- Ascertaining the type of diabetes

- Adjusting the basal insulin dosage

- Stopping the prandial insulin.

The steps are the same whether the surgery is major or minor. These recommendations are based on general principles of insulin action, data from large databases of surgical inpatients, and expert clinical experience translated into standardized protocols.1,2

WHY CONTINUE THE INSULIN?

Stopping or decreasing insulin because of a fear of hypoglycemia is not appropriate, as the resulting hyperglycemia can lead to delayed wound healing, wound infection, fluid and electrolyte shifts, diabetic ketoacidosis, and hyperosmolar states.

Insulin inhibits both gluconeogenesis and conversion of glycogen to glucose, processes that occur regardless of food intake. It also inhibits degradation of fats to fatty acids and of fatty acids to ketones. This is why inadequate insulin dosing can lead to uncontrolled hyperglycemia and even ketoacidosis, and thus why long-acting insulin is needed in a fasting state.

STEP 1: ASCERTAIN THE TYPE OF DIABETES

Does the patient have type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and does that even matter?

The type of diabetes should not matter, since ideally the insulin should be dosed the same for both types. However, the consequences of inappropriate insulin management may be different.

Usually, the type of diabetes can be ascertained by the history. If the patient was diagnosed at age 40 or later and was on oral medication for years before insulin was started, then he or she most likely has type 2. If the patient was younger than 40 at the time of diagnosis, was lean, and was started on insulin within a year of diagnosis, then he or she likely has type 1.

If this information is not available or is unreliable and the patient has been on insulin for many years, we recommend viewing the patient as being insulinopenic, ie, not producing enough insulin endogenously and thus requiring insulin at all times.

Though checking for antibody markers of type 1 diabetes might give a more definitive answer, it is not practical before surgery.

In the setting of surgical stress, withholding the basal insulin preoperatively and just giving a small dose of fast-acting (see Table 1 for the different classes of insulin) or shortacting insulin as part of a sliding scale (ie, insulin given only when the blood glucose reaches a certain high level) can send a patient with type 1 diabetes into diabetic ketoacidosis by the end of the day. This is less likely to occur in a patient with type 2 diabetes with some endogenous insulin secretion.

STEP 2: ADJUST THE BASAL INSULIN

Basal insulin is the insulin that the healthy person’s body produces when fasting. For a diabetic patient already on insulin, basal insulin is insulin injected to prevent ketogenesis, glycogenolysis, and gluconeogenesis in the fasting state.

If the basal insulin is long-acting

Long-acting insulins have a relatively peakless profile and, when properly dosed, should not result in hypoglycemia when a patient is fasting.

Preoperatively, the patient should take it as close as possible to the usual time of injection. This could be at home either at bedtime the night before surgery or the morning of surgery. If there is concern for hypoglycemia, the injection can be given when the patient is at the hospital.

- If the patient does not tend to have hypoglycemic episodes and the total daily basal insulin dose is roughly the same as the total daily mealtime (prandial) dose (eg, 50% basal, 50% prandial ratio), the full dose of basal insulin can be given.3

Example: If the patient is on insulin glargine 30 U at bedtime and insulin lispro 10 U with each meal and does not have hypoglycemic episodes, then insulin glargine 30 U should be taken at bedtime.

- If the patient has hypoglycemic episodes at home, then the basal insulin can be reduced by 25%.3

Example: If the patient is on insulin glargine 30 U at bedtime and insulin glulisine 10 U with each meal (appropriate proportion of doses, similar to the example above) but has hypoglycemic episodes at home on this regimen, then only 22 U of insulin glargine should be taken at bedtime.

- If the patient’s regimen has disproportionately more basal insulin than mealtime insulin, then the total daily doses can be added and half can be given as the basal insulin.

Example: If the patient is on insulin detemir 30 U every morning at 6 am and insulin aspart 6 U with each meal and has no hypoglycemic episodes, then 24 U of insulin detemir should be taken in the morning (ie, half of the total of 30 + 6 + 6 + 6).

- In the less common scenario of diabetes managed only with basal insulin (no other diabetes injections or oral agents), then half of the dose can be given.

- If the patient is on twice-daily long-acting basal insulin, then both the dose the night before surgery and the dose the morning of surgery should be adjusted.

If the basal insulin is intermediate-acting

The intermediate-acting insulin neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) is usually given twice a day because of its profile (Table 1).

- On the night before surgery, the full dose of NPH insulin should be taken, unless the patient will now skip a nighttime meal because of taking nothing by mouth, in which case the dose can be decreased by 25%.1

- On the morning of surgery, since the patient will be skipping breakfast and probably also lunch, the dose should be reduced by 50%.3,4

Special situation: Premixed insulins

Premixed insulins (70/30, 75/25) are a combination of intermediate-acting insulin and either fast-acting or short-acting insulin. In other words, they are combinations of basal and prandial insulin. Their use is thus not ideal in the preoperative period. There are two options in these situations.

One option is to switch to a regimen that includes long-acting insulin. If the patient is admitted for surgery, then the hospital staff can change the insulin regimen to long-acting basal insulin. A quick formula for conversion is to add all the premixed insulin doses and give half as basal insulin on the morning of surgery, similar to the scenario above for the patient with long-acting basal insulin that was out of proportion to the prandial insulin injections.

For example, if the usual regimen is insulin 70/30 NPH/Regular, 60 U with breakfast, 30 U with dinner, then the patient can take 45 U of insulin glargine (which is half of 60 + 30) in the morning or evening before surgery.

Another option is to adjust the dose of pre-mixed insulin. Sometimes it is not feasible or economical to change the patient’s premixed insulin just before surgery. In these situations, the patient can take half of the morning dose, followed by dextrose-containing intravenous fluids and blood glucose checks.

We recommend preoperatively giving at least part of the patient’s previous basal insulin, regardless of the type of diabetes, the type of surgery, or the fasting period.

STEP 3: STOP THE PRANDIAL INSULIN

Prandial insulin—given before each meal to cover the carbohydrates to be consumed—should be stopped the morning of surgery.3,4

WHAT ABOUT SLIDING SCALE INSULIN?

Using a sliding scale alone has no known benefit. Although it can be a quick fix to correct a high glucose level, it should be added to the basal insulin and not used as the sole insulin therapy. If a sliding scale is used, fast-acting insulin (aspart, glulisine, lispro) is preferred over regular insulin because of the more rapid onset and shorter duration of action.

Patients already using a supplemental insulin scale can apply it to correct a blood glucose above 200 mg/dL on the morning of surgery.

MAINTENANCE FLUIDS

As long as glucose levels are not very elevated (ie, > 200 mg/dL), after 12 hours on a nothing-by-mouth regimen, provide dextrose in the IV fluid to prevent hypoglycemia (eg, the patient received long-acting insulin and the glucose levels are running low) or to prevent starvation ketosis, which may result in ketones in the blood or urine. We recommend 5% dextrose in half-normal (0.45%) saline at 50 to 75 mL/hour as maintenance fluid; the infusion rate should be lower if fluid overload is a concern.

POSTOPERATIVE INSULIN MANAGEMENT

Once patients are discharged and can go back to their previous routine, they can restart their usual insulin regimen the same evening. The prandial insulin will be resumed when the regular diet is reintroduced, and the doses will be adjusted according to food intake.

Continuing at least part of the basal insulin is the reasonable, physiologic approach to controlling glucose levels before surgery in patients with diabetes. The process involves three basic steps:

- Ascertaining the type of diabetes

- Adjusting the basal insulin dosage

- Stopping the prandial insulin.

The steps are the same whether the surgery is major or minor. These recommendations are based on general principles of insulin action, data from large databases of surgical inpatients, and expert clinical experience translated into standardized protocols.1,2

WHY CONTINUE THE INSULIN?

Stopping or decreasing insulin because of a fear of hypoglycemia is not appropriate, as the resulting hyperglycemia can lead to delayed wound healing, wound infection, fluid and electrolyte shifts, diabetic ketoacidosis, and hyperosmolar states.

Insulin inhibits both gluconeogenesis and conversion of glycogen to glucose, processes that occur regardless of food intake. It also inhibits degradation of fats to fatty acids and of fatty acids to ketones. This is why inadequate insulin dosing can lead to uncontrolled hyperglycemia and even ketoacidosis, and thus why long-acting insulin is needed in a fasting state.

STEP 1: ASCERTAIN THE TYPE OF DIABETES

Does the patient have type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and does that even matter?

The type of diabetes should not matter, since ideally the insulin should be dosed the same for both types. However, the consequences of inappropriate insulin management may be different.

Usually, the type of diabetes can be ascertained by the history. If the patient was diagnosed at age 40 or later and was on oral medication for years before insulin was started, then he or she most likely has type 2. If the patient was younger than 40 at the time of diagnosis, was lean, and was started on insulin within a year of diagnosis, then he or she likely has type 1.

If this information is not available or is unreliable and the patient has been on insulin for many years, we recommend viewing the patient as being insulinopenic, ie, not producing enough insulin endogenously and thus requiring insulin at all times.

Though checking for antibody markers of type 1 diabetes might give a more definitive answer, it is not practical before surgery.

In the setting of surgical stress, withholding the basal insulin preoperatively and just giving a small dose of fast-acting (see Table 1 for the different classes of insulin) or shortacting insulin as part of a sliding scale (ie, insulin given only when the blood glucose reaches a certain high level) can send a patient with type 1 diabetes into diabetic ketoacidosis by the end of the day. This is less likely to occur in a patient with type 2 diabetes with some endogenous insulin secretion.

STEP 2: ADJUST THE BASAL INSULIN

Basal insulin is the insulin that the healthy person’s body produces when fasting. For a diabetic patient already on insulin, basal insulin is insulin injected to prevent ketogenesis, glycogenolysis, and gluconeogenesis in the fasting state.

If the basal insulin is long-acting

Long-acting insulins have a relatively peakless profile and, when properly dosed, should not result in hypoglycemia when a patient is fasting.

Preoperatively, the patient should take it as close as possible to the usual time of injection. This could be at home either at bedtime the night before surgery or the morning of surgery. If there is concern for hypoglycemia, the injection can be given when the patient is at the hospital.

- If the patient does not tend to have hypoglycemic episodes and the total daily basal insulin dose is roughly the same as the total daily mealtime (prandial) dose (eg, 50% basal, 50% prandial ratio), the full dose of basal insulin can be given.3

Example: If the patient is on insulin glargine 30 U at bedtime and insulin lispro 10 U with each meal and does not have hypoglycemic episodes, then insulin glargine 30 U should be taken at bedtime.

- If the patient has hypoglycemic episodes at home, then the basal insulin can be reduced by 25%.3

Example: If the patient is on insulin glargine 30 U at bedtime and insulin glulisine 10 U with each meal (appropriate proportion of doses, similar to the example above) but has hypoglycemic episodes at home on this regimen, then only 22 U of insulin glargine should be taken at bedtime.

- If the patient’s regimen has disproportionately more basal insulin than mealtime insulin, then the total daily doses can be added and half can be given as the basal insulin.

Example: If the patient is on insulin detemir 30 U every morning at 6 am and insulin aspart 6 U with each meal and has no hypoglycemic episodes, then 24 U of insulin detemir should be taken in the morning (ie, half of the total of 30 + 6 + 6 + 6).

- In the less common scenario of diabetes managed only with basal insulin (no other diabetes injections or oral agents), then half of the dose can be given.

- If the patient is on twice-daily long-acting basal insulin, then both the dose the night before surgery and the dose the morning of surgery should be adjusted.

If the basal insulin is intermediate-acting

The intermediate-acting insulin neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) is usually given twice a day because of its profile (Table 1).

- On the night before surgery, the full dose of NPH insulin should be taken, unless the patient will now skip a nighttime meal because of taking nothing by mouth, in which case the dose can be decreased by 25%.1

- On the morning of surgery, since the patient will be skipping breakfast and probably also lunch, the dose should be reduced by 50%.3,4

Special situation: Premixed insulins

Premixed insulins (70/30, 75/25) are a combination of intermediate-acting insulin and either fast-acting or short-acting insulin. In other words, they are combinations of basal and prandial insulin. Their use is thus not ideal in the preoperative period. There are two options in these situations.

One option is to switch to a regimen that includes long-acting insulin. If the patient is admitted for surgery, then the hospital staff can change the insulin regimen to long-acting basal insulin. A quick formula for conversion is to add all the premixed insulin doses and give half as basal insulin on the morning of surgery, similar to the scenario above for the patient with long-acting basal insulin that was out of proportion to the prandial insulin injections.

For example, if the usual regimen is insulin 70/30 NPH/Regular, 60 U with breakfast, 30 U with dinner, then the patient can take 45 U of insulin glargine (which is half of 60 + 30) in the morning or evening before surgery.

Another option is to adjust the dose of pre-mixed insulin. Sometimes it is not feasible or economical to change the patient’s premixed insulin just before surgery. In these situations, the patient can take half of the morning dose, followed by dextrose-containing intravenous fluids and blood glucose checks.

We recommend preoperatively giving at least part of the patient’s previous basal insulin, regardless of the type of diabetes, the type of surgery, or the fasting period.

STEP 3: STOP THE PRANDIAL INSULIN

Prandial insulin—given before each meal to cover the carbohydrates to be consumed—should be stopped the morning of surgery.3,4

WHAT ABOUT SLIDING SCALE INSULIN?

Using a sliding scale alone has no known benefit. Although it can be a quick fix to correct a high glucose level, it should be added to the basal insulin and not used as the sole insulin therapy. If a sliding scale is used, fast-acting insulin (aspart, glulisine, lispro) is preferred over regular insulin because of the more rapid onset and shorter duration of action.

Patients already using a supplemental insulin scale can apply it to correct a blood glucose above 200 mg/dL on the morning of surgery.

MAINTENANCE FLUIDS

As long as glucose levels are not very elevated (ie, > 200 mg/dL), after 12 hours on a nothing-by-mouth regimen, provide dextrose in the IV fluid to prevent hypoglycemia (eg, the patient received long-acting insulin and the glucose levels are running low) or to prevent starvation ketosis, which may result in ketones in the blood or urine. We recommend 5% dextrose in half-normal (0.45%) saline at 50 to 75 mL/hour as maintenance fluid; the infusion rate should be lower if fluid overload is a concern.

POSTOPERATIVE INSULIN MANAGEMENT

Once patients are discharged and can go back to their previous routine, they can restart their usual insulin regimen the same evening. The prandial insulin will be resumed when the regular diet is reintroduced, and the doses will be adjusted according to food intake.

- Joshi GP, Chung F, Vann MA, et al; Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia. Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia consensus statement on perioperative blood glucose management in diabetic patients undergoing ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 2010; 111:1378–1387.

- DiNardo M, Donihi AC, Forte P, Gieraltowski L, Korytkowski M. Standardized glycemic management and perioperative glycemic outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus who undergo same-day surgery. Endocr Pract 2011; 17:404–411.

- Vann MA. Perioperative management of ambulatory surgical patients with diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009; 22:718–724.

- Meneghini LF. Perioperative management of diabetes: translating evidence into practice. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76(suppl 4):S53–S59.

- Joshi GP, Chung F, Vann MA, et al; Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia. Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia consensus statement on perioperative blood glucose management in diabetic patients undergoing ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 2010; 111:1378–1387.

- DiNardo M, Donihi AC, Forte P, Gieraltowski L, Korytkowski M. Standardized glycemic management and perioperative glycemic outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus who undergo same-day surgery. Endocr Pract 2011; 17:404–411.

- Vann MA. Perioperative management of ambulatory surgical patients with diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009; 22:718–724.

- Meneghini LF. Perioperative management of diabetes: translating evidence into practice. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76(suppl 4):S53–S59.