User login

How apps are changing family medicine

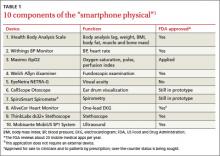

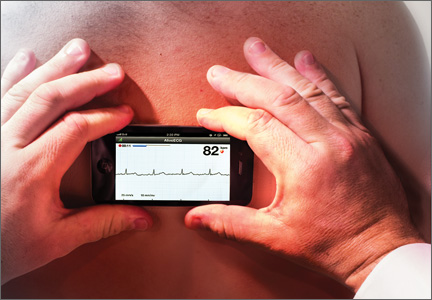

In April, hundreds of attendees at TEDMED, a conference on medical innovation, waited in line for a “smartphone physical.” Curated by Shiv Gaglani, a medical student and an editor at the medical technology journal Medgadget, the exam involved 10 apps that turn an ordinary smartphone into a medical device (TABLE 1).1 Among them were the AliveCor Heart Monitor (pictured at right), which produces a one-lead EKG in seconds when a patient’s fingers or chest are pressed against the electrodes embedded in the back of what is essentially a phone case2; a pulse oximeter, and an ultrasound that can capture images of the carotid arteries.1

All but one of the apps is paired with a physical component, such as an ultrasound wand or otoscope. The exception is SpiroSmart, an app that uses the phone’s The AliveCor app and Heart Monitor—a smartphone case fitted with sensors—can generate a one-lead EKG tracing in seconds.built-in microphone and lip reverberations to assess lung function. Shwetak Patel, PhD, of the University of Washington, one of its developers, told JFP that the accuracy of SpiroSmart has been found to be within 5% of traditional spirometry results.3

While smartphone physicals are not likely to be integrated into family practice for some time to come, Glen Stream, MD, board chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians, predicts that integration of some of their features is not too far away. “The spirometry application is an especially good one; it addresses one of the top 5 chronic conditions that contribute to health care costs,” Dr. Stream said. The apps will be beneficial, he added, as long as they “are used in a way that contributes, to, rather than detracts from, collaboration between patients and physicians.”

For now, Dr. Stream and many of his fellow FPs use mobile devices and medical apps primarily to access reference materials, both in and out of the exam room. Some have begun “prescribing” apps to tech-savvy patients. Still others have never used a medical app, either because they prefer a desktop or laptop computer to a smartphone or tablet or because, as one FP put it, "I have a dumb phone."

Wherever you fall on the spectrum, it’s a safe bet that you’re going to be increasingly inundated by the many manifestations of mobile health (mHealth).

Epocrates is No. 1 reference app

The number of medical/health apps for smart-phones or tablets is difficult to pin down; estimates range from 17,000 to more than 40,000, and growing.4 More is known about physician use of smartphones and tablets.

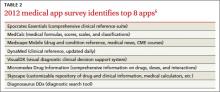

A March 2013 survey of nearly 3000 physicians found that 74% use smartphones at work and 43% use them to look up drug information.5 The favorite tool? A 2012 survey conducted by the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine to identify the best medical apps put Epocrates at the top of the list (TABLE 2).6 Epocrates was the very first app cited by virtually all the FPs interviewed for this article, as well.

Other drug references cited tend to be patient-specific. Colan Kennelly, MD, a clinical educator at the Good Samaritan Family Medicine Residency in Phoenix, finds LactMed particularly useful. Developed by the National Library of Medicine and part of its Toxicology Data Network, the app lets you pull up medications quickly and see whether and how they will affect breastfeeding.

Another favorite of Kennelly’s is the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s ePSS (electronic Preventive Services Selector) app designed to help primary care clinicians identify the preventive services that are appropriate for their patients. “You just plug in a patient’s age and sex”—(pregnancy, tobacco use, and whether the patient is sexually active are also considered)—“and it tells you what you should be checking for,” Dr. Kennelly said.

The benefits of mobile textbooks

Textbook apps and online texts are slowly gaining in popularity. A recent survey by Manhattan Research found that in 2013 for the first time, usage of electronic medical texts surpassed that of print editions.7 Part of the appeal is that mobile texts are easy to tote. “Apps make it possible to carry around information from a number of textbooks with no added weight,” said Richard Usatine, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and editor of JFP’s Photo Rounds column. Dr. Usatine is also a principal of Usatine Media, which turns medical reference materials into apps.

Dr. Usatine’s own experience is a case in point. He recently used a textbook app to prepare to take his boards (for the fifth time). “I’ve brushed up each time,” he said, “but this time I really studied because it was fun.

“With a print textbook you have to cover up the answers so you don’t see them. Here, you don’t get to see the answer until you commit to one of the multiple choice answers. Then you get told what the correct answer is and why you got it right or wrong,” Dr. Usatine said. Interactivity, including the opportunity to watch a video, say, of a procedure to review how it’s done before embarking on it yourself, is a big part of the value of apps, he said.

Rx: App

In January, Eric Topol, MD, a prominent cardiologist and chief academic officer of Scripps Health in La Jolla, Calif., demonstrated the AliveCor heart monitor and other mobile devices on NBC’s Rock Center.8 In March, he went on The Colbert Report and examined Stephen Colbert’s ear with an otoscope smartphone accessory (CellScope) like the one used in Gaglani’s smartphone physical.9 Dr. Topol’s use of the mobile heart monitor to assess an airplane passenger in distress midflight also received widespread news coverage.

In response to an interviewer’s question, Dr. Topol said he is now more likely to prescribe an app than a drug.8 While it’s unlikely that any FP could make such a claim, many have begun recommending apps to tech-savvy patients.

Smartphones as symptom trackers

A January 2013 Pew Internet study found that 7 in 10 US adults track at least one health indicator, for themselves or a loved one. Six in 10 reported tracking weight, diet, or exercise, and one in 3 said they track indicators of medical problems, such as blood pressure, glucose levels, headaches, or sleep patterns—usually without the aid of a smartphone.10

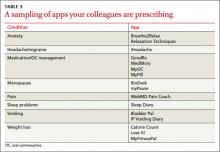

In fact, half of those who report tracking health measures said they keep the information “in their head,” and a third still use pencil and paper.10 That could change, of course, if their physicians suggest they do otherwise (TABLE 3).

Kelly M. Latimer, MD, an FP in the Navy stationed in Djibouti, Africa, routinely asks patients whether they have a smartphone and often recommends apps to those who do.

“It sounds like you have a lot of different symptoms,” she might say to a patient who complains of frequent headaches. “It will help me if you keep a headache diary.”

She used to give such patients paper and pen, Dr. Latimer noted. “Now I ask them to download the app (iHeadache, in this case) right then and there and do a quick review” so they’re ready to use it at home.

Apps are also a good way to help people with anxiety, Dr. Latimer has found. She frequently recommends apps like Relaxation Techniques and Breathe2Relax, and often suggests apps like Calorie Count and MyFitnessPal to boost patients’ efforts to lose weight and get in shape.

Abigail Lowther, MD, an FP at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, also recommends apps frequently. But she typically broaches the subject only with patients who have their smartphones out when she walks into the room.

Among the apps Dr. Lowther prescribes are myPause to track menopausal symptoms and Bladder Pal, a voiding diary for women struggling with incontinence. She advises women taking oral contraceptives to use the timer function on their phone to remember to take a pill at the same time every day. But there are apps (myPill, for one) that do that, too.

The upside of patient apps. A smartphone is ideal for keeping a symptom diary because it’s something that most people are never without. Anyone can use the notes function on a phone or tablet to jot down details about exacerbations, but those using disease-specific apps tend to capture more precise information. Some patients print out the information they’ve gathered and bring a hard copy to an office visit, while others simply show their physician what’s on their smartphone.

Can apps affect outcomes? There are few high-quality studies and the jury is still out, but “the smartphone has a very bright future in the world of medicine,” the authors of a review of smartphones in the medical arena concluded. After examining the use of apps to track (literally) wandering dementia patients; calculate and recommend insulin dosages for patients with type 1 diabetes; and teach yoga, to name a few, the researchers concluded that “the smartphone may one day be recognized as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool…as irreplaceable as the stethoscope.”11

Dr. Lowther recalls an obese patient who found MyFitnessPal to be helpful where other, more traditional diet programs had failed. The reason? He was less than truthful with the people overseeing the weight loss programs about what he’d eaten when he tried—and failed—to follow diets like Weight Watchers. He then ended up feeling so guilty that he abandoned the effort entirely. But, he told her, he “wouldn’t lie” to an app.

…and the downside. Even physicians who haven’t begun A weight loss app would be more likely to help this patient reach his goal than other diet programs because he "wouldn't lie" to an app.recommending apps to patients are aware that carefully tracking measures related to chronic conditions like hypertension or diabetes often results in better control. But in some cases, there may be too much of a good thing. Evidence suggests that for some patients with type 2 diabetes, glucose self-monitoring is associated with depression and may do more harm than good.12

Dr. Lowther has witnessed a similar phenomenon in patients using disease-tracking apps. “Sometimes people get too focused on the problem and drive themselves crazy,” she observed, adding that those with high blood pressure are particularly at risk. “I think sometimes it’s hard for patients to understand the concept of an average value and normal fluctuation,” Dr. Lowther said. When that happens, “I have to tell them to back off.”

Who's minding the (app) store?

The mHealth arena has been called “the wild West.”13 With at least one app for virtually every aspect of health and medicine you can think of, it’s not hard to understand why.

In an article on the use of symptom diaries in outpatient care, Bryan Hodge, DO, an FP in Hendersonville, NC, mentions mobile self-tracking apps as one of a number of ways for patients to keep symptom diaries.14 Given the fact that few of these apps have been validated, Dr. Hodge writes, “The best approach is to familiarize yourself with a few options that you can offer to your patients.”14

That depends on the nature of the app. An app that tracks calories consumed or simply keeps an organized file of patient symptoms may do little harm; an app that conveys physical measurements that a patient or physician may act on or calculates medication dosages requires a higher level of vigilance.

A recent study of smartphone apps that calculate opioid dosage conversion, for example, found a lack of consistency that raised a red flag about the reliability of information provided by unvalidated apps. Better regulation of medical apps is crucial to ensure that patient safety is maintained, the authors concluded.15

The FDA’s role

The US Food and Drug Administration, which has approved more than 75 medical apps, issued a proposed approach to its oversight of the apps in 2011.16

Under the proposed rules, the agency would regulate mobile apps that were either used as an accessory to a medical device already regulated by the FDA or that transform a smartphone or tablet into a regulated medical device. A final rule has not yet been issued, but a spokesperson told Congress that it will be forthcoming before the end of the year.17

False claims are a target of federal regulation, as well. In 2011, the Federal Trade Commission pulled 2 acne apps off the market because both advertised—without scientific evidence—that the light emitted by smartphones equipped with the apps could treat acne. “Smartphones make our lives easier in countless ways, but unfortunately, when it comes to curing acne, there’s no app for that,” the FTC chairman stated in a press release.18

In May 2013, the FDA sent an “It has come to our attention letter” to Biosense Technologies regarding its uChek urine analyzer app. The problem, the letter stated, is that the dipsticks that the app allows a mobile phone to analyze are cleared by the FDA only when interpreted by direct visual reading. But the phone and device together function “as an automated strip reader”—a urinalysis test system for which new FDA Smartphones make our lives easier in countless ways, but unfortunately, when it comes to curing acne, there's no app for that," the chairman of the Federal Trade Commission stated in a press release. clearance is required.19

Other ways of evaluating apps

Happtique, a mobile health solutions company, recently announced the launch of its Health App Certification Program—a voluntary program designed to help clinicians and patients easily identify apps that are credible and safe.20 “We will be certifying medical, health, and fitness apps, Corey Ackerman, president and CEO of Happtique, told JFP. The program is currently accepting medical education and nursing apps for review, and “discussions are underway with numerous other organizations that will provide experts for apps in additional subject matter areas,” Mr. Ackerman said.

There are other means of evaluating mobile medical apps that fall outside of the medical device realm, of course—starting by perusing the reviews posted at the app stores. Exchanging information with other clinicians using an app you’re interested in is another way to learn more about its efficacy. (Yes, there’s an app for that, too: Doximity, the professional network for clinicians.)

Other suggestions for safe use of apps:

- Peruse iMedicalApps (imedicalapps.com), the self-described leading physician publication on mobile medicine. Its physician editors and team of clinicians research and review medical apps.

- Consider the source. An app that has been developed by a medical society, federal agency, or prestigious medical school, for example, is more trustworthy than one from an unknown source (a point you would be wise to pass on to your patients).

- Try the app yourself before you recommend it to a patient.

Finally, keep the privacy provision in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in mind. Before using any app through which private patient health information can be transmitted or stored, ensure that the data will be encrypted and that your mobile device is password-protected, advises mHIMSS, the mobile branch of the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society.21

1. TEDMED. The smartphone physical. Available at: http://www.smartphonephysical.org/tedmed.html. Accessed June 14, 2013.

2. AliveCor. AliveCor heart monitor. Available at: http://www.alivecor.com/. Accessed June 14, 2013.

3. Ubiquitous Computing Lab, University of Washington. Mobile phone spirometry. Available at: http://ubicomplab.cs.washington.edu/wiki/SpiroSmart. Accessed June 19, 2013.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Explosive growth in health care apps raises oversight questions. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/october2012/308516/health-care-apps.html. Accessed June 14, 2013.

5. Alvarez A. How are physicians using smartphones for professional purposes? April 22, 2013. Available at: www.kantarmedia-healthcare.com/how-are-physicians-using-smartphones-for-professional-purposes. Accessed June 14, 2013.

6. Penn Medical Student Government. 2012 Medical app survey results. February 9, 2013. Available at: http://msg.med.upenn.edu/?p=17784. Accessed June 19, 2013.

7. Comstock J. Manhattan: 72% of physicians have tablets. April 18, 2013. Available at: http://mobihealthnews.com/21733/manhattan-72-percent-of-physicians-have-tablets/. Accessed June 19, 2013.

8. Dr. Eric Topol on NBC’s Rock Center. January 24, 2013. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0B-jUOOrtks. Accessed June 14, 2013.

9. Comstock J. Topol turns Colbert around on digital health. March 27, 2013. Available at: http://mobihealthnews.com/21263/topol-turns-colbert-around-on-digital-health/.Accessed June 14,2013.

10. Pew Research Center. Tracking for health. January 28, 2013. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Press-Releases/2013/Tracking-for-health. Accessed June 14, 2013.

11. Ozdalga E, Ozdalga A, Ahuja N. The smartphone in medicine: a review of current and potential use among physicians and students. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e128.

12. Mendoza M, Rosenberg T. Self-management of type 2 diabetes: a good idea or not? J Fam Pract. 2013;62:244-248.

13. McMillan R. iPad: ‘Wild West’ of medical apps seeks sheriff. December 12, 2011. Available at: http://www.wired.com/wiredenterprise/2011/12/fda_apps/. Accessed June 14, 2013.

14. Hodge B. The use of symptom diaries in outpatient care. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20:24-28.

15. Haffey F, Brady RR, Maxwell S. A comparison of the reliability of smartphone apps for opioid conversion. Drug Saf. 2013;36:111-117.

16. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA proposes health “app” guidelines. July 19, 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm263332.htm. Accessed June 14, 2013.

17. Pavlovic P. 10 issues that mobile medical app developers should keep in mind. April 18, 2013. Available at: http://www.mhimss.org/news/10-issues-mobile-medical-app-developers-should-keep-mind. Accessed June 14, 2013.

18. Federal Trade Commission. “Acne cure” mobile app marketers will drop baseless claims under FTC settlements. September 8, 2011. Available at: http://www.ftc.gov/opa/2011/09/acnecure.shtm. Accessed June 14, 2013.

19. FDA. Letter to Biosense Technologies Private Limited concerning the uChek urine analyzer. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ResourcesforYou/Industry/ucm353513.htm. Accessed June 14, 2013.

20. Happtique publishes final standards for mobile health app certification program. February 27, 2013. Available at: http://www.happtique.com/happtique-publishes-final-standards-for-mobile-health-app-certification-program/. Accessed June 19, 2013.

21. mHIMSS. Privacy and security. Available at: http://www.mhimss.org/resource-topics/privacy-security. Accessed June 14, 2013.

In April, hundreds of attendees at TEDMED, a conference on medical innovation, waited in line for a “smartphone physical.” Curated by Shiv Gaglani, a medical student and an editor at the medical technology journal Medgadget, the exam involved 10 apps that turn an ordinary smartphone into a medical device (TABLE 1).1 Among them were the AliveCor Heart Monitor (pictured at right), which produces a one-lead EKG in seconds when a patient’s fingers or chest are pressed against the electrodes embedded in the back of what is essentially a phone case2; a pulse oximeter, and an ultrasound that can capture images of the carotid arteries.1

All but one of the apps is paired with a physical component, such as an ultrasound wand or otoscope. The exception is SpiroSmart, an app that uses the phone’s The AliveCor app and Heart Monitor—a smartphone case fitted with sensors—can generate a one-lead EKG tracing in seconds.built-in microphone and lip reverberations to assess lung function. Shwetak Patel, PhD, of the University of Washington, one of its developers, told JFP that the accuracy of SpiroSmart has been found to be within 5% of traditional spirometry results.3

While smartphone physicals are not likely to be integrated into family practice for some time to come, Glen Stream, MD, board chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians, predicts that integration of some of their features is not too far away. “The spirometry application is an especially good one; it addresses one of the top 5 chronic conditions that contribute to health care costs,” Dr. Stream said. The apps will be beneficial, he added, as long as they “are used in a way that contributes, to, rather than detracts from, collaboration between patients and physicians.”

For now, Dr. Stream and many of his fellow FPs use mobile devices and medical apps primarily to access reference materials, both in and out of the exam room. Some have begun “prescribing” apps to tech-savvy patients. Still others have never used a medical app, either because they prefer a desktop or laptop computer to a smartphone or tablet or because, as one FP put it, "I have a dumb phone."

Wherever you fall on the spectrum, it’s a safe bet that you’re going to be increasingly inundated by the many manifestations of mobile health (mHealth).

Epocrates is No. 1 reference app

The number of medical/health apps for smart-phones or tablets is difficult to pin down; estimates range from 17,000 to more than 40,000, and growing.4 More is known about physician use of smartphones and tablets.

A March 2013 survey of nearly 3000 physicians found that 74% use smartphones at work and 43% use them to look up drug information.5 The favorite tool? A 2012 survey conducted by the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine to identify the best medical apps put Epocrates at the top of the list (TABLE 2).6 Epocrates was the very first app cited by virtually all the FPs interviewed for this article, as well.

Other drug references cited tend to be patient-specific. Colan Kennelly, MD, a clinical educator at the Good Samaritan Family Medicine Residency in Phoenix, finds LactMed particularly useful. Developed by the National Library of Medicine and part of its Toxicology Data Network, the app lets you pull up medications quickly and see whether and how they will affect breastfeeding.

Another favorite of Kennelly’s is the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s ePSS (electronic Preventive Services Selector) app designed to help primary care clinicians identify the preventive services that are appropriate for their patients. “You just plug in a patient’s age and sex”—(pregnancy, tobacco use, and whether the patient is sexually active are also considered)—“and it tells you what you should be checking for,” Dr. Kennelly said.

The benefits of mobile textbooks

Textbook apps and online texts are slowly gaining in popularity. A recent survey by Manhattan Research found that in 2013 for the first time, usage of electronic medical texts surpassed that of print editions.7 Part of the appeal is that mobile texts are easy to tote. “Apps make it possible to carry around information from a number of textbooks with no added weight,” said Richard Usatine, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and editor of JFP’s Photo Rounds column. Dr. Usatine is also a principal of Usatine Media, which turns medical reference materials into apps.

Dr. Usatine’s own experience is a case in point. He recently used a textbook app to prepare to take his boards (for the fifth time). “I’ve brushed up each time,” he said, “but this time I really studied because it was fun.

“With a print textbook you have to cover up the answers so you don’t see them. Here, you don’t get to see the answer until you commit to one of the multiple choice answers. Then you get told what the correct answer is and why you got it right or wrong,” Dr. Usatine said. Interactivity, including the opportunity to watch a video, say, of a procedure to review how it’s done before embarking on it yourself, is a big part of the value of apps, he said.

Rx: App

In January, Eric Topol, MD, a prominent cardiologist and chief academic officer of Scripps Health in La Jolla, Calif., demonstrated the AliveCor heart monitor and other mobile devices on NBC’s Rock Center.8 In March, he went on The Colbert Report and examined Stephen Colbert’s ear with an otoscope smartphone accessory (CellScope) like the one used in Gaglani’s smartphone physical.9 Dr. Topol’s use of the mobile heart monitor to assess an airplane passenger in distress midflight also received widespread news coverage.

In response to an interviewer’s question, Dr. Topol said he is now more likely to prescribe an app than a drug.8 While it’s unlikely that any FP could make such a claim, many have begun recommending apps to tech-savvy patients.

Smartphones as symptom trackers

A January 2013 Pew Internet study found that 7 in 10 US adults track at least one health indicator, for themselves or a loved one. Six in 10 reported tracking weight, diet, or exercise, and one in 3 said they track indicators of medical problems, such as blood pressure, glucose levels, headaches, or sleep patterns—usually without the aid of a smartphone.10

In fact, half of those who report tracking health measures said they keep the information “in their head,” and a third still use pencil and paper.10 That could change, of course, if their physicians suggest they do otherwise (TABLE 3).

Kelly M. Latimer, MD, an FP in the Navy stationed in Djibouti, Africa, routinely asks patients whether they have a smartphone and often recommends apps to those who do.

“It sounds like you have a lot of different symptoms,” she might say to a patient who complains of frequent headaches. “It will help me if you keep a headache diary.”

She used to give such patients paper and pen, Dr. Latimer noted. “Now I ask them to download the app (iHeadache, in this case) right then and there and do a quick review” so they’re ready to use it at home.

Apps are also a good way to help people with anxiety, Dr. Latimer has found. She frequently recommends apps like Relaxation Techniques and Breathe2Relax, and often suggests apps like Calorie Count and MyFitnessPal to boost patients’ efforts to lose weight and get in shape.

Abigail Lowther, MD, an FP at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, also recommends apps frequently. But she typically broaches the subject only with patients who have their smartphones out when she walks into the room.

Among the apps Dr. Lowther prescribes are myPause to track menopausal symptoms and Bladder Pal, a voiding diary for women struggling with incontinence. She advises women taking oral contraceptives to use the timer function on their phone to remember to take a pill at the same time every day. But there are apps (myPill, for one) that do that, too.

The upside of patient apps. A smartphone is ideal for keeping a symptom diary because it’s something that most people are never without. Anyone can use the notes function on a phone or tablet to jot down details about exacerbations, but those using disease-specific apps tend to capture more precise information. Some patients print out the information they’ve gathered and bring a hard copy to an office visit, while others simply show their physician what’s on their smartphone.

Can apps affect outcomes? There are few high-quality studies and the jury is still out, but “the smartphone has a very bright future in the world of medicine,” the authors of a review of smartphones in the medical arena concluded. After examining the use of apps to track (literally) wandering dementia patients; calculate and recommend insulin dosages for patients with type 1 diabetes; and teach yoga, to name a few, the researchers concluded that “the smartphone may one day be recognized as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool…as irreplaceable as the stethoscope.”11

Dr. Lowther recalls an obese patient who found MyFitnessPal to be helpful where other, more traditional diet programs had failed. The reason? He was less than truthful with the people overseeing the weight loss programs about what he’d eaten when he tried—and failed—to follow diets like Weight Watchers. He then ended up feeling so guilty that he abandoned the effort entirely. But, he told her, he “wouldn’t lie” to an app.

…and the downside. Even physicians who haven’t begun A weight loss app would be more likely to help this patient reach his goal than other diet programs because he "wouldn't lie" to an app.recommending apps to patients are aware that carefully tracking measures related to chronic conditions like hypertension or diabetes often results in better control. But in some cases, there may be too much of a good thing. Evidence suggests that for some patients with type 2 diabetes, glucose self-monitoring is associated with depression and may do more harm than good.12

Dr. Lowther has witnessed a similar phenomenon in patients using disease-tracking apps. “Sometimes people get too focused on the problem and drive themselves crazy,” she observed, adding that those with high blood pressure are particularly at risk. “I think sometimes it’s hard for patients to understand the concept of an average value and normal fluctuation,” Dr. Lowther said. When that happens, “I have to tell them to back off.”

Who's minding the (app) store?

The mHealth arena has been called “the wild West.”13 With at least one app for virtually every aspect of health and medicine you can think of, it’s not hard to understand why.

In an article on the use of symptom diaries in outpatient care, Bryan Hodge, DO, an FP in Hendersonville, NC, mentions mobile self-tracking apps as one of a number of ways for patients to keep symptom diaries.14 Given the fact that few of these apps have been validated, Dr. Hodge writes, “The best approach is to familiarize yourself with a few options that you can offer to your patients.”14

That depends on the nature of the app. An app that tracks calories consumed or simply keeps an organized file of patient symptoms may do little harm; an app that conveys physical measurements that a patient or physician may act on or calculates medication dosages requires a higher level of vigilance.

A recent study of smartphone apps that calculate opioid dosage conversion, for example, found a lack of consistency that raised a red flag about the reliability of information provided by unvalidated apps. Better regulation of medical apps is crucial to ensure that patient safety is maintained, the authors concluded.15

The FDA’s role

The US Food and Drug Administration, which has approved more than 75 medical apps, issued a proposed approach to its oversight of the apps in 2011.16

Under the proposed rules, the agency would regulate mobile apps that were either used as an accessory to a medical device already regulated by the FDA or that transform a smartphone or tablet into a regulated medical device. A final rule has not yet been issued, but a spokesperson told Congress that it will be forthcoming before the end of the year.17

False claims are a target of federal regulation, as well. In 2011, the Federal Trade Commission pulled 2 acne apps off the market because both advertised—without scientific evidence—that the light emitted by smartphones equipped with the apps could treat acne. “Smartphones make our lives easier in countless ways, but unfortunately, when it comes to curing acne, there’s no app for that,” the FTC chairman stated in a press release.18

In May 2013, the FDA sent an “It has come to our attention letter” to Biosense Technologies regarding its uChek urine analyzer app. The problem, the letter stated, is that the dipsticks that the app allows a mobile phone to analyze are cleared by the FDA only when interpreted by direct visual reading. But the phone and device together function “as an automated strip reader”—a urinalysis test system for which new FDA Smartphones make our lives easier in countless ways, but unfortunately, when it comes to curing acne, there's no app for that," the chairman of the Federal Trade Commission stated in a press release. clearance is required.19

Other ways of evaluating apps

Happtique, a mobile health solutions company, recently announced the launch of its Health App Certification Program—a voluntary program designed to help clinicians and patients easily identify apps that are credible and safe.20 “We will be certifying medical, health, and fitness apps, Corey Ackerman, president and CEO of Happtique, told JFP. The program is currently accepting medical education and nursing apps for review, and “discussions are underway with numerous other organizations that will provide experts for apps in additional subject matter areas,” Mr. Ackerman said.

There are other means of evaluating mobile medical apps that fall outside of the medical device realm, of course—starting by perusing the reviews posted at the app stores. Exchanging information with other clinicians using an app you’re interested in is another way to learn more about its efficacy. (Yes, there’s an app for that, too: Doximity, the professional network for clinicians.)

Other suggestions for safe use of apps:

- Peruse iMedicalApps (imedicalapps.com), the self-described leading physician publication on mobile medicine. Its physician editors and team of clinicians research and review medical apps.

- Consider the source. An app that has been developed by a medical society, federal agency, or prestigious medical school, for example, is more trustworthy than one from an unknown source (a point you would be wise to pass on to your patients).

- Try the app yourself before you recommend it to a patient.

Finally, keep the privacy provision in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in mind. Before using any app through which private patient health information can be transmitted or stored, ensure that the data will be encrypted and that your mobile device is password-protected, advises mHIMSS, the mobile branch of the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society.21

In April, hundreds of attendees at TEDMED, a conference on medical innovation, waited in line for a “smartphone physical.” Curated by Shiv Gaglani, a medical student and an editor at the medical technology journal Medgadget, the exam involved 10 apps that turn an ordinary smartphone into a medical device (TABLE 1).1 Among them were the AliveCor Heart Monitor (pictured at right), which produces a one-lead EKG in seconds when a patient’s fingers or chest are pressed against the electrodes embedded in the back of what is essentially a phone case2; a pulse oximeter, and an ultrasound that can capture images of the carotid arteries.1

All but one of the apps is paired with a physical component, such as an ultrasound wand or otoscope. The exception is SpiroSmart, an app that uses the phone’s The AliveCor app and Heart Monitor—a smartphone case fitted with sensors—can generate a one-lead EKG tracing in seconds.built-in microphone and lip reverberations to assess lung function. Shwetak Patel, PhD, of the University of Washington, one of its developers, told JFP that the accuracy of SpiroSmart has been found to be within 5% of traditional spirometry results.3

While smartphone physicals are not likely to be integrated into family practice for some time to come, Glen Stream, MD, board chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians, predicts that integration of some of their features is not too far away. “The spirometry application is an especially good one; it addresses one of the top 5 chronic conditions that contribute to health care costs,” Dr. Stream said. The apps will be beneficial, he added, as long as they “are used in a way that contributes, to, rather than detracts from, collaboration between patients and physicians.”

For now, Dr. Stream and many of his fellow FPs use mobile devices and medical apps primarily to access reference materials, both in and out of the exam room. Some have begun “prescribing” apps to tech-savvy patients. Still others have never used a medical app, either because they prefer a desktop or laptop computer to a smartphone or tablet or because, as one FP put it, "I have a dumb phone."

Wherever you fall on the spectrum, it’s a safe bet that you’re going to be increasingly inundated by the many manifestations of mobile health (mHealth).

Epocrates is No. 1 reference app

The number of medical/health apps for smart-phones or tablets is difficult to pin down; estimates range from 17,000 to more than 40,000, and growing.4 More is known about physician use of smartphones and tablets.

A March 2013 survey of nearly 3000 physicians found that 74% use smartphones at work and 43% use them to look up drug information.5 The favorite tool? A 2012 survey conducted by the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine to identify the best medical apps put Epocrates at the top of the list (TABLE 2).6 Epocrates was the very first app cited by virtually all the FPs interviewed for this article, as well.

Other drug references cited tend to be patient-specific. Colan Kennelly, MD, a clinical educator at the Good Samaritan Family Medicine Residency in Phoenix, finds LactMed particularly useful. Developed by the National Library of Medicine and part of its Toxicology Data Network, the app lets you pull up medications quickly and see whether and how they will affect breastfeeding.

Another favorite of Kennelly’s is the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s ePSS (electronic Preventive Services Selector) app designed to help primary care clinicians identify the preventive services that are appropriate for their patients. “You just plug in a patient’s age and sex”—(pregnancy, tobacco use, and whether the patient is sexually active are also considered)—“and it tells you what you should be checking for,” Dr. Kennelly said.

The benefits of mobile textbooks

Textbook apps and online texts are slowly gaining in popularity. A recent survey by Manhattan Research found that in 2013 for the first time, usage of electronic medical texts surpassed that of print editions.7 Part of the appeal is that mobile texts are easy to tote. “Apps make it possible to carry around information from a number of textbooks with no added weight,” said Richard Usatine, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and editor of JFP’s Photo Rounds column. Dr. Usatine is also a principal of Usatine Media, which turns medical reference materials into apps.

Dr. Usatine’s own experience is a case in point. He recently used a textbook app to prepare to take his boards (for the fifth time). “I’ve brushed up each time,” he said, “but this time I really studied because it was fun.

“With a print textbook you have to cover up the answers so you don’t see them. Here, you don’t get to see the answer until you commit to one of the multiple choice answers. Then you get told what the correct answer is and why you got it right or wrong,” Dr. Usatine said. Interactivity, including the opportunity to watch a video, say, of a procedure to review how it’s done before embarking on it yourself, is a big part of the value of apps, he said.

Rx: App

In January, Eric Topol, MD, a prominent cardiologist and chief academic officer of Scripps Health in La Jolla, Calif., demonstrated the AliveCor heart monitor and other mobile devices on NBC’s Rock Center.8 In March, he went on The Colbert Report and examined Stephen Colbert’s ear with an otoscope smartphone accessory (CellScope) like the one used in Gaglani’s smartphone physical.9 Dr. Topol’s use of the mobile heart monitor to assess an airplane passenger in distress midflight also received widespread news coverage.

In response to an interviewer’s question, Dr. Topol said he is now more likely to prescribe an app than a drug.8 While it’s unlikely that any FP could make such a claim, many have begun recommending apps to tech-savvy patients.

Smartphones as symptom trackers

A January 2013 Pew Internet study found that 7 in 10 US adults track at least one health indicator, for themselves or a loved one. Six in 10 reported tracking weight, diet, or exercise, and one in 3 said they track indicators of medical problems, such as blood pressure, glucose levels, headaches, or sleep patterns—usually without the aid of a smartphone.10

In fact, half of those who report tracking health measures said they keep the information “in their head,” and a third still use pencil and paper.10 That could change, of course, if their physicians suggest they do otherwise (TABLE 3).

Kelly M. Latimer, MD, an FP in the Navy stationed in Djibouti, Africa, routinely asks patients whether they have a smartphone and often recommends apps to those who do.

“It sounds like you have a lot of different symptoms,” she might say to a patient who complains of frequent headaches. “It will help me if you keep a headache diary.”

She used to give such patients paper and pen, Dr. Latimer noted. “Now I ask them to download the app (iHeadache, in this case) right then and there and do a quick review” so they’re ready to use it at home.

Apps are also a good way to help people with anxiety, Dr. Latimer has found. She frequently recommends apps like Relaxation Techniques and Breathe2Relax, and often suggests apps like Calorie Count and MyFitnessPal to boost patients’ efforts to lose weight and get in shape.

Abigail Lowther, MD, an FP at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, also recommends apps frequently. But she typically broaches the subject only with patients who have their smartphones out when she walks into the room.

Among the apps Dr. Lowther prescribes are myPause to track menopausal symptoms and Bladder Pal, a voiding diary for women struggling with incontinence. She advises women taking oral contraceptives to use the timer function on their phone to remember to take a pill at the same time every day. But there are apps (myPill, for one) that do that, too.

The upside of patient apps. A smartphone is ideal for keeping a symptom diary because it’s something that most people are never without. Anyone can use the notes function on a phone or tablet to jot down details about exacerbations, but those using disease-specific apps tend to capture more precise information. Some patients print out the information they’ve gathered and bring a hard copy to an office visit, while others simply show their physician what’s on their smartphone.

Can apps affect outcomes? There are few high-quality studies and the jury is still out, but “the smartphone has a very bright future in the world of medicine,” the authors of a review of smartphones in the medical arena concluded. After examining the use of apps to track (literally) wandering dementia patients; calculate and recommend insulin dosages for patients with type 1 diabetes; and teach yoga, to name a few, the researchers concluded that “the smartphone may one day be recognized as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool…as irreplaceable as the stethoscope.”11

Dr. Lowther recalls an obese patient who found MyFitnessPal to be helpful where other, more traditional diet programs had failed. The reason? He was less than truthful with the people overseeing the weight loss programs about what he’d eaten when he tried—and failed—to follow diets like Weight Watchers. He then ended up feeling so guilty that he abandoned the effort entirely. But, he told her, he “wouldn’t lie” to an app.

…and the downside. Even physicians who haven’t begun A weight loss app would be more likely to help this patient reach his goal than other diet programs because he "wouldn't lie" to an app.recommending apps to patients are aware that carefully tracking measures related to chronic conditions like hypertension or diabetes often results in better control. But in some cases, there may be too much of a good thing. Evidence suggests that for some patients with type 2 diabetes, glucose self-monitoring is associated with depression and may do more harm than good.12

Dr. Lowther has witnessed a similar phenomenon in patients using disease-tracking apps. “Sometimes people get too focused on the problem and drive themselves crazy,” she observed, adding that those with high blood pressure are particularly at risk. “I think sometimes it’s hard for patients to understand the concept of an average value and normal fluctuation,” Dr. Lowther said. When that happens, “I have to tell them to back off.”

Who's minding the (app) store?

The mHealth arena has been called “the wild West.”13 With at least one app for virtually every aspect of health and medicine you can think of, it’s not hard to understand why.

In an article on the use of symptom diaries in outpatient care, Bryan Hodge, DO, an FP in Hendersonville, NC, mentions mobile self-tracking apps as one of a number of ways for patients to keep symptom diaries.14 Given the fact that few of these apps have been validated, Dr. Hodge writes, “The best approach is to familiarize yourself with a few options that you can offer to your patients.”14

That depends on the nature of the app. An app that tracks calories consumed or simply keeps an organized file of patient symptoms may do little harm; an app that conveys physical measurements that a patient or physician may act on or calculates medication dosages requires a higher level of vigilance.

A recent study of smartphone apps that calculate opioid dosage conversion, for example, found a lack of consistency that raised a red flag about the reliability of information provided by unvalidated apps. Better regulation of medical apps is crucial to ensure that patient safety is maintained, the authors concluded.15

The FDA’s role

The US Food and Drug Administration, which has approved more than 75 medical apps, issued a proposed approach to its oversight of the apps in 2011.16

Under the proposed rules, the agency would regulate mobile apps that were either used as an accessory to a medical device already regulated by the FDA or that transform a smartphone or tablet into a regulated medical device. A final rule has not yet been issued, but a spokesperson told Congress that it will be forthcoming before the end of the year.17

False claims are a target of federal regulation, as well. In 2011, the Federal Trade Commission pulled 2 acne apps off the market because both advertised—without scientific evidence—that the light emitted by smartphones equipped with the apps could treat acne. “Smartphones make our lives easier in countless ways, but unfortunately, when it comes to curing acne, there’s no app for that,” the FTC chairman stated in a press release.18

In May 2013, the FDA sent an “It has come to our attention letter” to Biosense Technologies regarding its uChek urine analyzer app. The problem, the letter stated, is that the dipsticks that the app allows a mobile phone to analyze are cleared by the FDA only when interpreted by direct visual reading. But the phone and device together function “as an automated strip reader”—a urinalysis test system for which new FDA Smartphones make our lives easier in countless ways, but unfortunately, when it comes to curing acne, there's no app for that," the chairman of the Federal Trade Commission stated in a press release. clearance is required.19

Other ways of evaluating apps

Happtique, a mobile health solutions company, recently announced the launch of its Health App Certification Program—a voluntary program designed to help clinicians and patients easily identify apps that are credible and safe.20 “We will be certifying medical, health, and fitness apps, Corey Ackerman, president and CEO of Happtique, told JFP. The program is currently accepting medical education and nursing apps for review, and “discussions are underway with numerous other organizations that will provide experts for apps in additional subject matter areas,” Mr. Ackerman said.

There are other means of evaluating mobile medical apps that fall outside of the medical device realm, of course—starting by perusing the reviews posted at the app stores. Exchanging information with other clinicians using an app you’re interested in is another way to learn more about its efficacy. (Yes, there’s an app for that, too: Doximity, the professional network for clinicians.)

Other suggestions for safe use of apps:

- Peruse iMedicalApps (imedicalapps.com), the self-described leading physician publication on mobile medicine. Its physician editors and team of clinicians research and review medical apps.

- Consider the source. An app that has been developed by a medical society, federal agency, or prestigious medical school, for example, is more trustworthy than one from an unknown source (a point you would be wise to pass on to your patients).

- Try the app yourself before you recommend it to a patient.

Finally, keep the privacy provision in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in mind. Before using any app through which private patient health information can be transmitted or stored, ensure that the data will be encrypted and that your mobile device is password-protected, advises mHIMSS, the mobile branch of the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society.21

1. TEDMED. The smartphone physical. Available at: http://www.smartphonephysical.org/tedmed.html. Accessed June 14, 2013.

2. AliveCor. AliveCor heart monitor. Available at: http://www.alivecor.com/. Accessed June 14, 2013.

3. Ubiquitous Computing Lab, University of Washington. Mobile phone spirometry. Available at: http://ubicomplab.cs.washington.edu/wiki/SpiroSmart. Accessed June 19, 2013.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Explosive growth in health care apps raises oversight questions. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/october2012/308516/health-care-apps.html. Accessed June 14, 2013.

5. Alvarez A. How are physicians using smartphones for professional purposes? April 22, 2013. Available at: www.kantarmedia-healthcare.com/how-are-physicians-using-smartphones-for-professional-purposes. Accessed June 14, 2013.

6. Penn Medical Student Government. 2012 Medical app survey results. February 9, 2013. Available at: http://msg.med.upenn.edu/?p=17784. Accessed June 19, 2013.

7. Comstock J. Manhattan: 72% of physicians have tablets. April 18, 2013. Available at: http://mobihealthnews.com/21733/manhattan-72-percent-of-physicians-have-tablets/. Accessed June 19, 2013.

8. Dr. Eric Topol on NBC’s Rock Center. January 24, 2013. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0B-jUOOrtks. Accessed June 14, 2013.

9. Comstock J. Topol turns Colbert around on digital health. March 27, 2013. Available at: http://mobihealthnews.com/21263/topol-turns-colbert-around-on-digital-health/.Accessed June 14,2013.

10. Pew Research Center. Tracking for health. January 28, 2013. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Press-Releases/2013/Tracking-for-health. Accessed June 14, 2013.

11. Ozdalga E, Ozdalga A, Ahuja N. The smartphone in medicine: a review of current and potential use among physicians and students. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e128.

12. Mendoza M, Rosenberg T. Self-management of type 2 diabetes: a good idea or not? J Fam Pract. 2013;62:244-248.

13. McMillan R. iPad: ‘Wild West’ of medical apps seeks sheriff. December 12, 2011. Available at: http://www.wired.com/wiredenterprise/2011/12/fda_apps/. Accessed June 14, 2013.

14. Hodge B. The use of symptom diaries in outpatient care. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20:24-28.

15. Haffey F, Brady RR, Maxwell S. A comparison of the reliability of smartphone apps for opioid conversion. Drug Saf. 2013;36:111-117.

16. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA proposes health “app” guidelines. July 19, 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm263332.htm. Accessed June 14, 2013.

17. Pavlovic P. 10 issues that mobile medical app developers should keep in mind. April 18, 2013. Available at: http://www.mhimss.org/news/10-issues-mobile-medical-app-developers-should-keep-mind. Accessed June 14, 2013.

18. Federal Trade Commission. “Acne cure” mobile app marketers will drop baseless claims under FTC settlements. September 8, 2011. Available at: http://www.ftc.gov/opa/2011/09/acnecure.shtm. Accessed June 14, 2013.

19. FDA. Letter to Biosense Technologies Private Limited concerning the uChek urine analyzer. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ResourcesforYou/Industry/ucm353513.htm. Accessed June 14, 2013.

20. Happtique publishes final standards for mobile health app certification program. February 27, 2013. Available at: http://www.happtique.com/happtique-publishes-final-standards-for-mobile-health-app-certification-program/. Accessed June 19, 2013.

21. mHIMSS. Privacy and security. Available at: http://www.mhimss.org/resource-topics/privacy-security. Accessed June 14, 2013.

1. TEDMED. The smartphone physical. Available at: http://www.smartphonephysical.org/tedmed.html. Accessed June 14, 2013.

2. AliveCor. AliveCor heart monitor. Available at: http://www.alivecor.com/. Accessed June 14, 2013.

3. Ubiquitous Computing Lab, University of Washington. Mobile phone spirometry. Available at: http://ubicomplab.cs.washington.edu/wiki/SpiroSmart. Accessed June 19, 2013.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Explosive growth in health care apps raises oversight questions. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/october2012/308516/health-care-apps.html. Accessed June 14, 2013.

5. Alvarez A. How are physicians using smartphones for professional purposes? April 22, 2013. Available at: www.kantarmedia-healthcare.com/how-are-physicians-using-smartphones-for-professional-purposes. Accessed June 14, 2013.

6. Penn Medical Student Government. 2012 Medical app survey results. February 9, 2013. Available at: http://msg.med.upenn.edu/?p=17784. Accessed June 19, 2013.

7. Comstock J. Manhattan: 72% of physicians have tablets. April 18, 2013. Available at: http://mobihealthnews.com/21733/manhattan-72-percent-of-physicians-have-tablets/. Accessed June 19, 2013.

8. Dr. Eric Topol on NBC’s Rock Center. January 24, 2013. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0B-jUOOrtks. Accessed June 14, 2013.

9. Comstock J. Topol turns Colbert around on digital health. March 27, 2013. Available at: http://mobihealthnews.com/21263/topol-turns-colbert-around-on-digital-health/.Accessed June 14,2013.

10. Pew Research Center. Tracking for health. January 28, 2013. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Press-Releases/2013/Tracking-for-health. Accessed June 14, 2013.

11. Ozdalga E, Ozdalga A, Ahuja N. The smartphone in medicine: a review of current and potential use among physicians and students. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e128.

12. Mendoza M, Rosenberg T. Self-management of type 2 diabetes: a good idea or not? J Fam Pract. 2013;62:244-248.

13. McMillan R. iPad: ‘Wild West’ of medical apps seeks sheriff. December 12, 2011. Available at: http://www.wired.com/wiredenterprise/2011/12/fda_apps/. Accessed June 14, 2013.

14. Hodge B. The use of symptom diaries in outpatient care. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20:24-28.

15. Haffey F, Brady RR, Maxwell S. A comparison of the reliability of smartphone apps for opioid conversion. Drug Saf. 2013;36:111-117.

16. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA proposes health “app” guidelines. July 19, 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm263332.htm. Accessed June 14, 2013.

17. Pavlovic P. 10 issues that mobile medical app developers should keep in mind. April 18, 2013. Available at: http://www.mhimss.org/news/10-issues-mobile-medical-app-developers-should-keep-mind. Accessed June 14, 2013.

18. Federal Trade Commission. “Acne cure” mobile app marketers will drop baseless claims under FTC settlements. September 8, 2011. Available at: http://www.ftc.gov/opa/2011/09/acnecure.shtm. Accessed June 14, 2013.

19. FDA. Letter to Biosense Technologies Private Limited concerning the uChek urine analyzer. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ResourcesforYou/Industry/ucm353513.htm. Accessed June 14, 2013.

20. Happtique publishes final standards for mobile health app certification program. February 27, 2013. Available at: http://www.happtique.com/happtique-publishes-final-standards-for-mobile-health-app-certification-program/. Accessed June 19, 2013.

21. mHIMSS. Privacy and security. Available at: http://www.mhimss.org/resource-topics/privacy-security. Accessed June 14, 2013.

Is your patient sick—or hungry?

Late last year, news outlets nationwide confirmed what many had long suspected: America’s middle class is shrinking. The latest data from the US Census Bureau found that nearly half (48%) of Americans are poor or low income.1,2

That means 46.2 million people—more than 15% of US citizens—are living below the federal poverty level (FPL), which is $23,050 for a family of 4. Another 97.3 million (about 33%) meet the criterion for low income—earning between $23,050 and $45,869 for a family of 4.1,2 These numbers are based on the Census Bureau’s new supplemental poverty measure, which considers costs like medical and housing and benefits such as food stamps in calculating poverty.3

The way that census data are analyzed is a key consideration for policy makers and legislators. For primary care physicians, the findings simply serve as a critical reminder that millions of Americans—including some of your patients—are struggling to stay afloat.

In some cases, the problems patients face will be so severe that there won’t be much you can do about them. In others, there are steps you can take to lend a helping hand (TABLE).

TABLE

Help the poor and uninsured: 9 things you can do

|

Death by poverty?

That’s the title of a summary of a recent study, posted on the Web site of Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.4 The researchers found that poverty, low levels of education, and a lack of social support, among other “social” factors, account for as many deaths as heart attack, stroke, and lung cancer.5

A related study, also by researchers at Columbia, attempted to quantify the health impact of some leading medical and nonmedical factors. Their findings: The detrimental effects of poverty, smoking, and being a high school dropout exceed those of binge drinking, being overweight or obese, and being uninsured.6 The average low-income individual loses 8.2 years of good health simply because of his or her economic status, the lead researcher reported. In contrast, the average loss associated with obesity is 4.2 years and 6.6 years with smoking. The overall health of the US population won’t improve until poverty rates are reduced and educational deficits are addressed, the lead researcher concluded.7

That’s not to negate the importance of health coverage, however: A Kaiser Family Foundation study of low-income adults found that fully half (51%) of those who lacked health insurance had not gone to a doctor or clinic in the previous 12 months—and 69% had received no preventive care in the course of the year.8

Another survey, completed in 2007, asked adults younger than 65 about their use of medication. About 1 in 7 (13.9%) said they had failed to fill a prescription in the previous year because they couldn’t afford it. Four years earlier, 10.3% had done so.9

Recently, however, the situation appears to have gotten even worse. In a 2011 Consumer Reports survey, just under half of adults taking prescription medication reported that they had cut costs by engaging in what the surveyors described as “risky health care tradeoffs”—eg, not filling a prescription, skipping doses, or taking an expired medication.10

Poverty in childhood has long-lasting effects

Children may be less likely than adults to require prescription drugs, but they are typically the hardest hit by poverty—both in numbers and long-term effects. The poverty rate for those younger than 18 is 22%, according to the National Center for Children in Poverty.11 For kids under the age of 5, it’s more than 25%.12

Children of poor, uneducated parents have worse health and die earlier than those whose families are wealthier and better educated, research suggests.13-16 Even kids from middle class families fall short on measures of health and well-being compared with children whose families are more affluent. What’s more, being poor in early childhood appears to have lasting effects. Regardless of social or economic status or individual behavior later in life, studies suggest that the stress of poverty in the early years is associated with chronic illness and disability in adulthood.13-16

The bottom line, according to the Robert Wood Johnson Commission to Build a Healthier America: “For the first time in our history, the United States is raising a generation of children who may live sicker, shorter lives than their parents.”13 Hunger, or the lack of an adequate supply of nutritious food, is a key factor.17

Hunger hits home

In an op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle, family physician Laura Gottlieb told the story of an 8-year-old boy whose family she’d known for years. Brought to her office because of abdominal pain, the boy underwent multiple tests, including urine and stool examinations, blood work, and imaging studies. As soon as one test came back, Dr. Gottlieb ordered another. All were negative, and no cause for GI distress was found.18

Only later did she discover that hunger was the source of the pain. “It had never even occurred to me to ask his mother about how much food there was in the house,” Dr. Gottlieb wrote.18

In a similar vein, CBS News recently ran a story about a high school football team that seemed to be down on its luck. Besides being on a losing streak, many of the players were lethargic. Eventually, an astute coach realized that a mental pickup wasn’t what the team members needed—nutrition was. In this impoverished Burke County, Georgia school, about 85% of the student body qualify for in-school breakfast and lunch. But for many kids, those 2 meals were all they had to eat.19

With the help of a school nutritionist and the federal Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act, hundreds of students now receive dinner, too. And last season, in late 2011, the properly fueled team members went on to win the state championship.19

Who is “food insecure”? In 2010, the latest year for which figures are available, 14.5% of US households (representing a total of 48.8 million people) were “food insecure,” as the problem of having too little to eat is officially known.20 Most of these families managed without substantially disrupting their normal eating patterns or reducing their intake, the US Department of Agriculture reports. This was accomplished by cutting back on the variety of foods they ate, getting federal food assistance, or getting food from food banks, among other coping strategies. But for 6.4 million households, the problem was severe enough to disrupt normal eating patterns and cause those affected to eat less than usual at least part of the time in the course of the year.20

Here, too, the toll on children is especially high. Twenty percent of households with children face food insecurity, nearly twice the rate of childless households.20 In a child’s earliest years, too little energy, protein, and other nutrients can result in long-lasting deficits in social, cognitive, and emotional development; malnutrition and deficiencies in vitamins and minerals may even result in brain impairment.18 In addition, school-age children who don’t have enough to eat have more behavioral problems and are more likely than those who are not struggling with hunger to be in special education classes.17

The hunger and obesity link

Ironically, hunger is also associated with obesity. High calorie, high carbohydrate foods like pasta and bread typically cost considerably less than nutrient-rich low-carb foods like cheese, fruit, fish, and vegetables, and are more filling. And in poor neighborhoods, food that is high in carbohydrates and low in protein and other nutrients tends to be more available than fresh, healthy—and more perishable—food.21

What’s more, people living in poverty may find it especially difficult to exercise. In many neighborhoods, exercising outdoors can be dangerous, gyms are unaffordable, and safe parks and playgrounds may be few and far between.21

Identifying poor and hungry patients

In a survey conducted by the Childhood Hunger Initiative of Oregon, most of the nearly 200 physicians and nurse practitioners who responded expressed a desire to learn more about the consequences of hunger and how to address them. Besides being uncomfortable broaching the subject of hunger and other poverty-related issues, the providers cited time constraints as a barrier to doing so.22

Ask this question

Citing similar obstacles, Canadian researchers conducted a pilot study in search of an easy-to-use, evidence-based “case-finding” tool. They offered questionnaires to patients at 4 clinics in British Columbia to determine which questions had the highest likelihood of determining whether an individual was struggling with hunger, poverty, or homelessness. Participants, which included patients above (n=94) and below (n=51) the poverty line, were also asked how they felt about being asked such questions.23

One particular question—“Do you (ever) have difficulty making ends meet at the end of the month?”—proved to be the best predictor of poverty. Although 2 additional questions about food and housing were identified as suitable for a 3-item screening tool, this single question alone had 98% sensitivity and 60% specificity (odds ratio, 32.3; 95% confidence interval, 5.4-191.5). Equally important, 85% of study participants with income below the poverty level thought that poverty screening was important, and 67% said they felt comfortable talking to their family physician about it.23

Take this course

In response to the results of the provider survey conducted by the Childhood Hunger Initiative of Oregon, a team at the Oregon State University Extension Service developed an online training program. The free 5-module course, available at http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/dce/chi/modules.html, addresses the impact of childhood hunger and provides screening and intervention tips.24

A recommended strategy is to incorporate a question related to hunger and food insecurity into the medical history or physical assessment. Noting that you’ll learn more by asking whether a family has sufficient resources to provide a healthy diet than by simply inquiring about a balanced diet, a narrator uses this wording:

“In the past month, was there any day when you or anyone in your family went hungry because you didn’t have enough money for food?”24

What you can do to help needy patients

Some patients who are out of work, uninsured, and barely able to pay for food and shelter will simply put off doctor visits—or come in only after their condition is so dire that you have no recourse but to send them to the emergency department (ED). The result, of course, is just the opposite of what they had hoped for. They end up with a much larger bill—or, if they have coverage, with a much bigger copay—not to mention a far more serious condition than they would likely have had if they’d come in sooner.

Here are some ways you can help.

Discuss costs with uninsured patients. To encourage uninsured patients to come in before their condition worsens, make them aware of the comparatively low cost of a visit to your office vs that of, say, imaging studies, specialist visits, and lab tests, as well as ED costs. That’s one of the interventions recommended by Robert A. Forester, MD, and Richard J. Heck, MD, the authors of “What You Can Do to Help Your Uninsured Patients.”25 Consider offering discounts to low-income patients (within the bounds of Medicare and other insurance provisions), they also suggest.

Use fewer diagnostic tests. Ordering a battery of tests when a diagnosis is not readily apparent is a “cost-insensitive” way to practice medicine, authors Forester and Heck observe. Spending additional time with such patients, using your cognitive and diagnostic skills and performing a complete history and physical, frequently results in a diagnosis and treatment plan, they note.25 If patients are aware that you’re trying to minimize costs, they’ll often consent to a step-by-step diagnostic work-up that can be stopped at any time it is appropriate.

Do it yourself. Expand your practice to include a variety of minor procedures, such as removal or biopsy of common skin lesions, colposcopy, or setting simple fractures. These measures can help keep costs down to better serve poor and low-income patients. The American Academy of Family Physicians offers courses and training in various procedures that family physicians can competently perform in their own offices.

Request a courtesy consult. On occasion, you may be able to avoid a costly referral by calling a colleague and asking for a courtesy consult. The specialist will often tell you how he or she would handle a clinical presentation like the one you describe and suggest you try a similar approach, suggests Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA. Dr. Campos-Outcalt, a faculty member at the University of Arizona College of Medicine and the author of JFP’s bimonthly Practice Alert column, has extensive experience working with underserved communities.

Connect patients with community services. Poor patients typically have many social and psychological needs, as well as the need for medical care, and integrated care is particularly important for those facing hunger, homelessness, and chronic illness, says Jonathan Cartsonis, MD, medical director of Healthcare for the Homeless in Phoenix. Maintain contact with hospital social services and emergency psychiatric services, and have information—and handouts—about local food banks, homeless shelters, and community clinics, among other resources. (See the resources listed in the box.)

Feeding America Food Bank Locator

http://feedingamerica.org/foodbank-results.aspx

Insure Kids Now

http://www.insurekidsnow.gov/state/index.html/

National Association of Free and Charitable Clinics

http://www.freemedicalcamps.com

Nutrition Standards for School Meals (Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act)

http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/Governance/Legislation/nutritionstandards.htm

Partnership for Prescription Assistance

www.pparx.org

Rx Outreach

http://rxoutreach.com/

SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program)

http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/applicant_recipients/eligibility.htm#income

WIC (Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children)

http://stars.fns.usda.gov/wps/pages/start.jsf

In Seattle, for example, “Project Access” is an organization that helps give the underserved access to specialists. And in many parts of the country, local Rotary clubs sponsor free clinics staffed with volunteer and retired physicians, working cooperatively with local pharmacies to provide at-cost generic drugs.

Keep drug costs down

Physicians can help to insulate their poor and low-income patients from high drug costs in a number of ways:

Reduce polypharmacy. Half of Americans take at least one prescription drug, according to the 2011 Consumer Reports survey. Among this group, people with limited income—those earning less than $40,000—take, on average, 5.7 different drugs.10 Eliminating unnecessary medications, including supplements, herbs, and any other over-the-counter products, can lead to substantial savings. To determine what can be eliminated, ask patients to bring in everything they’re taking and conduct a brown bag medication review. To learn more, see “Help your patient ‘get’ what you just said: A health literacy guide” (J Fam Pract. 2012;61:190-196).

Prescribe generics. Newer brand-name drugs may not be markedly better than older, established agents. And many generics are available at major retailers like Wal-Mart for just a few dollars for a 30-day supply or at CVS for $9.99 for a 3-month supply.26 Yet some physicians routinely order newer medications, even for indigent patients.

Be upfront about drug costs. When you prescribe a new drug, whether generic or branded, it is important to discuss the cost (easily accessible online and in many electronic medical record systems) with the patient. Yet only 5% of respondents to the 2011 Consumer Reports survey said their health care providers had done so. Two-thirds of those surveyed (64%) did not discover the cost of a drug until they went to a pharmacy to pick it up.10

Think twice before handing out samples. Drug samples would appear to benefit the poor and the uninsured, but evidence suggests otherwise.27,28 In a study that assessed out-of-pocket costs associated with the use of samples, patients who had never received samples had lower out-of-pocket costs.28 That’s partly because most samples are newer, more expensive drugs, and patients who start taking them are often unable to afford the cost of a prescription. Another study found that the use of generic drugs for uninsured patients rose (from 12% to 30%) after the clinic discontinued the use of samples.27

CORRESPONDENCE Laura C. Lippman, MD, 2311 North 45th Street, No. 171, Seattle, WA 98103; [email protected]

1. Tavernise S, Gebeloff R. New way to tally poor recasts view of poverty. New York Times. November 7, 2011. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/08/us/poverty-gets-new-measure-at-census-bureau.html?_r=2&scp=1&sq=poverty&st=cse. Accessed March 12, 2012.

2. Income poverty and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010 [press release]. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; September 13, 2011. Available at: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/income_wealth/cb11-157.html. Accessed March 12, 2012.

3. Short K. The research supplemental poverty measure: 2010. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; November 2011. Available at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/povmeas/methodology/supplemental/research/Short_ResearchSPM2010.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2012.

4. University Mailman School of Public Health. Death by poverty? June 16, 2011. Available at: http://www.mailman.columbia.edu/academic-departments/epidemiology/research-service/death-poverty. Accessed March 5, 2012.

5. Galea S, Tracy M, Hoggatt KJ, et al. Estimated deaths attributable to social factors in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1456-1465

6. Muennig P, Fiscella K, Tancredi D, et al. The relative health burden of selected social and behavioral risk factors in the United States: implications for policy. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1758-1764.

7. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Poor face greater health burden than smokers or the obese. Available at: http://www.mailman.columbia.edu/academic-departments/health-policy/news-events/poor-face-greater-health-burden-smokers-or-obese. Accessed March 13, 2012.

8. Schwartz K. How trends in the health care system affect low-income adults: identifying access problems and financial burdens. December 21, 2007. Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at: http://www.kff.org/uninsured/7705.cfm. Accessed March 2, 2012.

9. Felland LE, Reschovsky JD. More nonelderly Americans face problems affording prescription drugs. Tracking report no. 22. January 2009. Center for Studying Health System Change. Available at: http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/1039/. Accessed January 25, 2012.

10. Consumer Reports poll: 48 percent of Americans on meds making risky health care tradeoffs [press release]. Yonkers, NY: Consumer Reports; September 27, 2011. Available at: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/consumer-reports-poll—48-percent-of-americans-on-meds-making-risky-health-care-tradeoffs-130618778.html. Accessed January 3, 2012.

11. A job-loss recovery hurts children most: statistics tell an alarming story [press release] New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty; September 15, 2011. Available at: http://www.nccp.org/media/releases/release_135.html. Accessed January 24, 2012.

12. Child Trends Data Bank. Children in poverty. Updated September 2011. Available at: http://www.childtrendsdatabank.org/?q=node/221. Accessed March 13, 2012.

13. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Overcoming obstacles to health. Princeton, NJ: RWJF Commission to Build a Healthier America; February 2008. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/files/research/obstaclestohealth.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2012.

14. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e232-e246.

15. Stein DJ, Scott K, Haro Abad JM, et al. Early childhood adversity and later hypertension: data from the World Mental Health Survey. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2010;22:19-28.

16. O’Rand AM, Hamil-Luker J. Processes of cumulative adversity: childhood disadvantage and increased risk of heart attack across the life course. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(spec no 2):117-124.

17. American Psychological Association. Effects of poverty, hunger, and homelessness on children and youth. Available at: http://www.apa.org/pi/families/poverty.aspx. Accessed November 29, 2011.

18. Gottlieb L. Funding healthy society helps cure health care. San Francisco Chronicle. August 23, 2010:A-8.

19. Doane S. High school football team battles malnutrition. December 20, 2011. CBS News. Available at: http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-18563_162-57345857/high-school-football-team-battles-malnutrition/. Accessed March 13, 2012.

20. US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Food security in the United States: key statistics and graphics. Updated September 7, 2011. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/FoodSecurity/stats_graphs.htm. Accessed March 1, 2012.

21. Drewnowski A, Damon N. Food choices and diet costs: an economic analysis. J Nutr. 2005;135:900-904.

22. Survey helps doctors help hungry patients [press release]. Portland, Ore: Oregon State University Extension Service; May 27, 2008. Available at: http://extension.oregonstate.edu/news/release/2008/05/survey-helps-doctors-help-hungry-patients. Accessed February 29, 2012.

23. Brcic V, Eberdt C, Kaczorowski J. Development of a tool to identify poverty in a family practice setting: a pilot study. Int J Family Med. 2011;2011:812182.