User login

2021 Update on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery

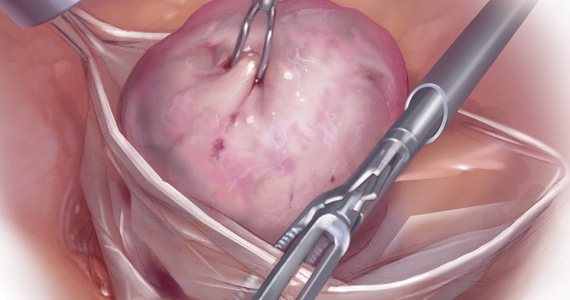

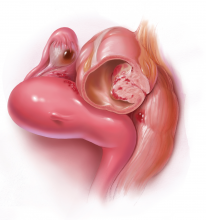

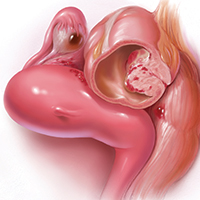

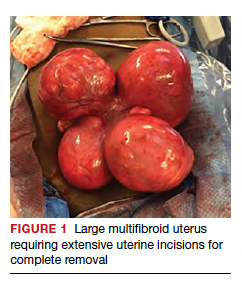

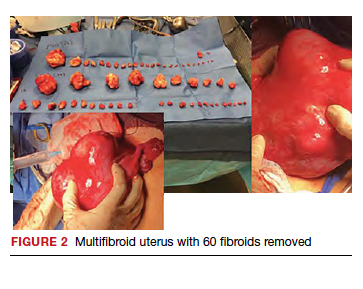

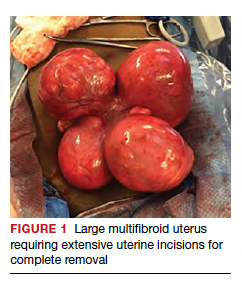

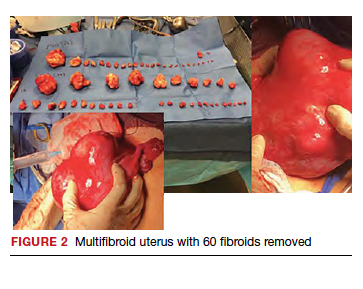

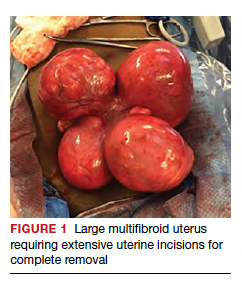

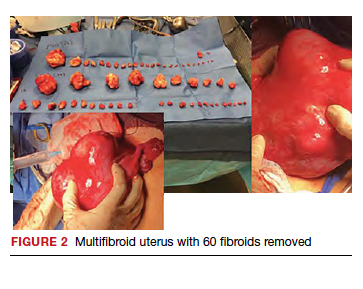

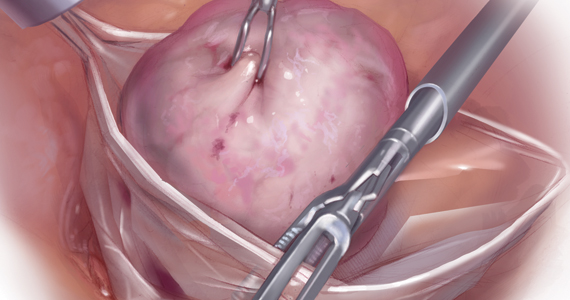

Uterine fibroids are a common condition that affects up to 80% of reproductive-age women.1 Many women with fibroids are asymptomatic, but some experience symptoms that profoundly disrupt their lives, such as abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, and bulk symptoms including bladder and bowel dysfunction.2 Although hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment for symptomatic fibroids, many women seek more conservative management. Hormonal treatment, such as contraceptive pills, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, can improve heavy menstrual bleeding and anemia.3 Additionally, uterine artery embolization is a nonsurgical uterine-sparing option. However, these treatments are not ideal options for women who want to conceive.4 For reproductive-age women who desire future fertility, myomectomy has been the standard of care. Unfortunately, by the time patients become symptomatic from their fibroids and seek care, they may have numerous and/or sizable fibroids that result in high blood loss, surgical scarring, and the probable need for cesarean delivery (FIGURES 1 and 2).5

For patients who desire future conception, treatment of uterine fibroids poses a challenge in which optimizing symptomatic improvement must be balanced with protecting fertility and improving reproductive outcomes. In recent years, high-intensity focused ultrasound (FUS) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) have been presented as less invasive, uterine-sparing alternatives for fibroid treatment that could potentially provide that balance.

In this article, we briefly review the available uterine-sparing fibroid treatments and their outcomes and then focus specifically on RFA as a possible option to address the fibroid treatment gap for reproductive-age women who desire future fertility.

Overview of uterine-sparing treatments

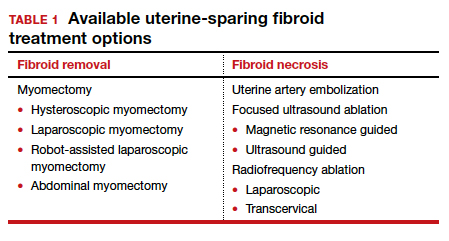

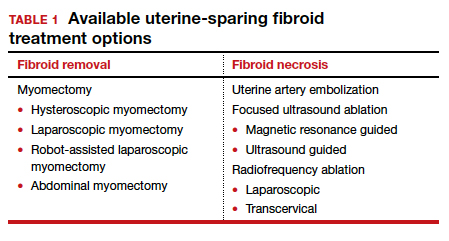

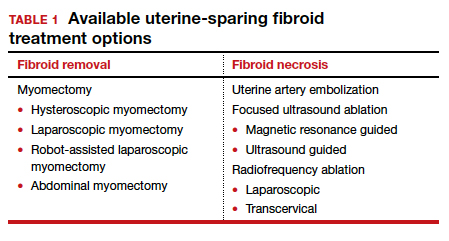

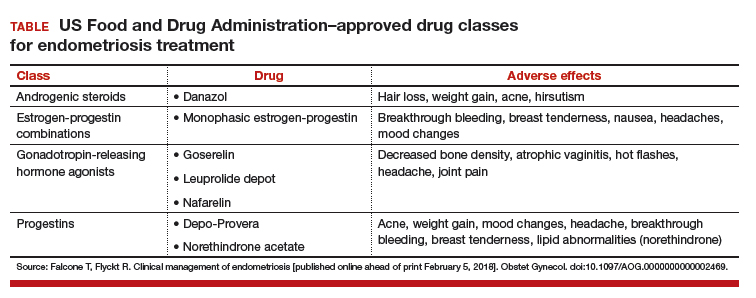

Two approaches can be pursued for conservative fibroid treatment: fibroid removal and fibroid necrosis (TABLE 1). We focus this review on outcomes for the most widely available of these treatments.

Myomectomy

For reproductive-age women who wish to conceive, surgical removal of fibroids has been the standard of care for symptomatic patients. Myomectomy can be performed via laparotomy, laparoscopy, robot-assisted surgery, and hysteroscopy. The mode of surgery depends on the fibroid characteristics (size, number, and location) and the surgeon’s skill set. Although some variation in the data exists, overall surgical outcomes, including blood loss, postoperative pain, and length of stay, are generally more favorable for minimally invasive approaches compared with laparotomy, with no significant differences in fibroid recurrence or reproductive outcomes (live birth rate, miscarriage rate, and cesarean delivery rate).6 This comes at the expense of longer operating time compared with laparotomy.7

While improvement in abnormal uterine bleeding and pelvic pain is reliable and usually significant after myomectomy,8 reproductive implications also warrant consideration. Myomectomy is associated with subsequent uterine adhesion formation, with some studies finding rates up to 83% to 94% depending on the surgical approach and the number of fibroids removed.9 These adhesions can impair fertility success.10 Myomectomy also is associated with high rates of cesarean delivery,5 invasive placentation (including placenta accreta spectrum),11 and uterine rupture.12 While the latter 2 complications are rare, they potentially can be catastrophic and should be kept in mind.

Continue to: Uterine artery embolization...

Uterine artery embolization

As a nonsurgical alternative to myomectomy, uterine artery embolization (UAE) has gained popularity as a conservative fibroid treatment since it was introduced in 1995. It is less invasive than myomectomy, a benefit for patients who decline surgery or are not ideal candidates for surgery.13 Evidence suggests that UAE produces overall comparable symptomatic improvement compared with myomectomy. One study showed no significant differences between UAE and myomectomy in terms of decreased uterine volume and menstrual bleeding at 6-month follow-up.14 In terms of long-term outcomes, a large multicenter study showed no significant difference in reintervention rates at 7 years posttreatment between UAE and myomectomy (8.9% vs 11.2%, respectively), and a significantly higher rate of improved menstrual bleeding with UAE (79.4% vs 49.5%), with no significant difference in bulk symptoms.15 The evidence is not entirely consistent, as other studies have shown increased rates of reintervention with UAE,8,16 but overall UAE can be considered a reasonable alternative to myomectomy in terms of symptomatic improvement.

Pregnancy outcomes data, however, are mixed, and UAE often is not recommended for patients with future fertility plans. In a large review article that compared minimally invasive fibroid treatments, UAE was associated with a lower live birth rate compared with myomectomy and ablation techniques (60.6% for UAE, 75.6% for myomectomy, and 70.5% for ablation), and it also had the highest rate of miscarriage (27.4% for UAE vs 19.0% for myomectomy and 11.9% for ablation) and abnormal placentation.12 While UAE remains an effective option for conservative treatment of symptomatic fibroids, it appears to have a worse impact on reproductive outcomes compared with myomectomy or ablative treatments.

Magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound

Emerging as a noninvasive ablation treatment for fibroids, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) uses targeted high-intensity ultrasound pulses to cause thermal and mechanical fibroid tissue disruption.17 Data on this treatment are less robust given that it is newer than myomectomy or UAE. One study showed a decrease in fibroid volume by 12% at 1 month and 15% at 6 months, with 37.1% of patients reporting marked improvement in symptoms and an additional 31.4% reporting partial improvement; these are modest numbers compared with other treatment approaches.18 Another study showed more favorable outcomes, with 74% of patients reporting clinically significant improvement in bleeding and pain, and a 12.7% reintervention rate, comparable to rates reported for UAE and myomectomy.19

Because MRgFUS is newer than UAE or myomectomy, data are limited in terms of pregnancy outcomes, particularly because initial trials excluded women with future fertility plans due to lack of knowledge regarding pregnancy safety. A follow-up case series from one of the initial studies showed a decreased miscarriage rate compared with UAE, a term delivery rate of 93%, and a similar rate of abnormal placentation.20 A more recent systematic review concluded that reproductive outcomes were noninferior to myomectomy; however, the outcomes data for MRgFUS were heterogenous and many studies did not report pregnancy rates.21

Overall, MRgFUS appears to be an effective alternative approach for symptomatic fibroids, but the long-term data are not yet conclusive and information on pregnancy safety and outcomes largely is lacking. Recent reviews have not made definitive statements on whether MRgFUS should be offered to patients desiring future fertility.

Continue to: RFA is a promising option...

RFA is a promising option

RFA is another noninvasive fibroid ablation technique that has become more widely adopted in recent years. Here, we describe the basics of RFA and its impact on fibroid symptoms and reproductive outcomes.

The RFA technique

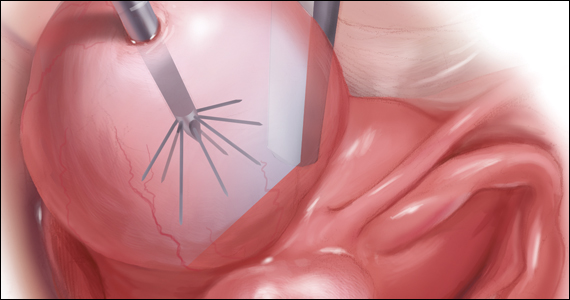

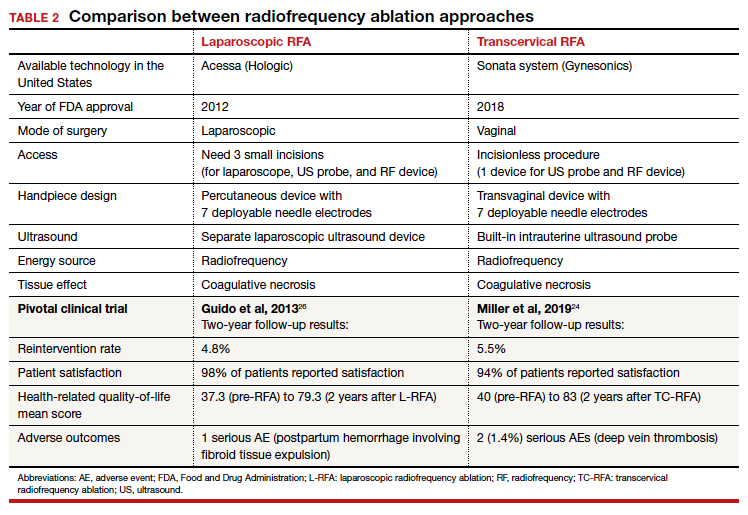

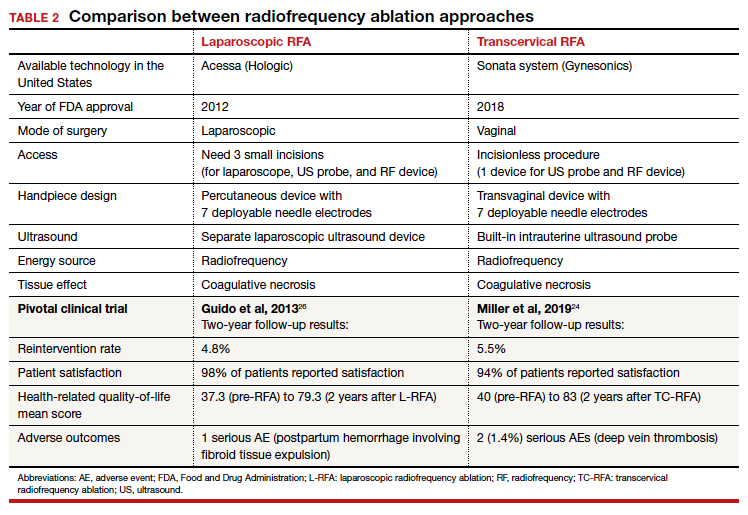

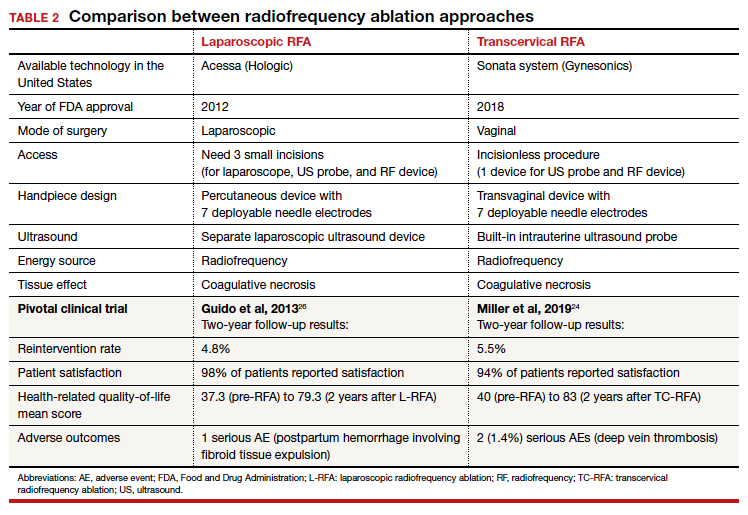

RFA uses hyperthermic energy from a handpiece and real-time ultrasound for targeted coagulative necrosis via a laparoscopic (L-RFA) or transcervical (TC-RFA) approach.22 A comparison between the 2 devices available on the market in the United States is shown in TABLE 2. Ultrasound guidance allows placement of radiofrequency needles directly into the fibroid to target local treatment to the fibroid tissue only. Once the fibroid undergoes coagulative necrosis, the process of fibroid resorption and volume reduction occurs over weeks to months, depending on the fibroid size.

Impact on fibroid symptoms

Both laparoscopic and transcervical RFA approaches have shown significant decreases in pelvic pain and heavy menstrual bleeding associated with fibroids and a low reintervention rate that emphasizes the durability of their impact.

A feasibility and safety study of a TC-RFA device prior to the primary clinical trials found only a 4.3% reintervention rate in the first 18 months postprocedure.23 The pivotal clinical trial of a TC-RFA device that followed also reported a low 5.5% reintervention rate in the first 24 months postprocedure, with significant improvement in health-related quality-of-life and high patient satisfaction24 (results shown in TABLE 2, along with trial results for an L-RFA device). A subsequent study of TC-RFA reported that symptomatic improvement persisted at 3-year follow-up, with a 9.2% reintervention rate comparable to existing fibroid treatments such as myomectomy and UAE.25 The original L-RFA trial also has shown similar positive results at 2-year follow-up, with a low reintervention rate of 4.8% after treatment, and similar patient satisfaction and quality-of-life improvements as TC-RFA.26 While long-term data are limited by only recent approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of a TC-RFA device in 2018, one study followed clinical trial patients for a mean duration of 64 months. This study found no surgical reinterventions in the first 3.5 years posttreatment and a persistent reduction in fibroid symptoms from baseline 64.9 points to 27.6 points, as assessed by a validated symptom severity scale (out of 100 points).27 Similar improvements in health-related quality-of life-were also found to persist for years posttreatment.4

In a large systematic review that compared L-RFA, MRgFUS, UAE, and myomectomy, L-RFA had similar improvement rates in quality-of-life and symptom severity scores compared with myomectomy, with no significant difference in reintervention rates.28 This review also noted minimal heterogeneity among RFA meta-analyses data in contrast to significant heterogeneity among UAE and myomectomy data.

Reproductive outcomes

Similar to MRgFUS, the initial studies of RFA devices largely excluded women with future fertility plans, as data on safety were lacking. However, many RFA devices are now on the market across the globe, and subsequent pregnancies have been tracked and reported.

A large case series that included clinical trials and commercial settings reported a miscarriage rate (13.3%) similar to that of the general obstetric population and no cases of uterine rupture, invasive placentation, preterm delivery, or placental abruption.29 Other case series have reported live birth rates similar those with myomectomy, and safe and favorable pregnancy outcomes with RFA have been supported by larger systematic reviews of all ablation techniques.12

Continue to: Uterine impact...

Uterine impact

One study of TC-RFA patients showed a greater than 65% reduction in fibroid volume (with a 90% reduction in fibroid volume for fibroids larger than 6 cm prior to RFA), and 54% of patients reported complete resolution of symptoms, with another 36% reporting decreased symptoms.30 Similar decreases in fibroid volume, ranging from 65% to 84%, have been reported in numerous follow-up studies, with significant decreases in bleeding and pain in 78% to 88% of patients.23,31-33 Additionally, a large secondary analysis of a TC-RFA clinical trial showed that patients did not have any significant decrease in uterine wall thickness or integrity on follow-up with magnetic resonance imaging compared with baseline measurements, and they did not have any new myometrial scars (assessed as nonperfused linear areas).22

As with other ablation techniques, most data on RFA pregnancy outcomes come from case series, and further research and evaluation are needed. Existing studies, however, have demonstrated promising aspects of RFA that argue its usefulness in women with fertility plans.

A prospective trial that evaluated intrauterine adhesion formation with use of a TC-RFA device found no new adhesions on 6-week follow-up hysteroscopy compared with baseline pre-RFA hysteroscopy.34 Because intrauterine adhesion formation and uterine rupture are both significant concerns with other uterine-sparing fibroid treatment approaches such as myomectomy, these findings suggest that RFA may be a better alternative for women who are planning future pregnancies, as they may have increased fertility success and decreased catastrophic complications.

The consensus is growing that RFA is a safe and effective option for women who desire minimally invasive fibroid treatment and want to preserve fertility.

Unique benefits of RFA

In this article, we highlight RFA as an emerging treatment option for fibroid management, particularly for women who desire a uterine-sparing approach to preserve their reproductive options. Although myomectomy has been the standard of care for many years, with UAE as the alternative nonsurgical treatment, neither approach provides the best balance between symptomatic improvement and reproductive outcomes, and neither is without pregnancy risks. In addition, many women with symptomatic fibroids do not desire future conception but decline fibroid removal for religious or personal reasons. RFA offers these women an alternative minimally invasive option for uterine-sparing fibroid treatment.

RFA presents a unique “incision-free” fibroid treatment that is truly minimally invasive. This technique minimizes the risks associated with myomectomy, such as intra-abdominal adhesions, intrauterine adhesions (Asherman syndrome), need for cesarean delivery, and pregnancy complications such as uterine rupture or invasive placentation. Furthermore, the evolution of an RFA transcervical approach has enabled treatment with no abdominal or uterine incisions, thus offering all the above reproductive benefits as well as the operative benefits of a faster recovery, less pain, and less risk of intraperitoneal surgical complications.

While many women desire uterine-sparing fibroid treatment even without future fertility plans, the larger question is whether we should treat fibroids more strategically for women who desire future fertility. Myomectomy and UAE are effective and reliable in terms of fibroid symptomatic improvement, but RFA promises more beneficial reproductive outcomes. The ability to avoid uterine myometrial incisions and still attain significant symptomatic improvement should be prioritized in these patients.

Currently, RFA is not approved by the FDA as a fertility-enabling treatment, and these patients have been largely excluded from RFA studies. However, the reproductive-age patient who desires future conception may benefit most from RFA. Furthermore, RFA technology also could address the gap in uterine-sparing treatment for reproductive-age women with adenomyosis. Although a complete review of adenomyosis treatment is beyond the scope of this article, recent studies show that RFA produces similar improvement in both uterine volume and symptom severity in women with adenomyosis.35-37 ●

The RFA data suggest that both laparoscopic and transcervical RFA offer a safe and effective alternative treatment option for patients with symptomatic fibroids who seek uterine-sparing treatment, and transcervical RFA offers the least invasive treatment option. Women with fibroids who wish to conceive currently face a challenging treatment gap in clinical medicine, and future research is needed to address this concern in these patients. RFA is promising and appears to be a better fertility-enabling conservative fibroid treatment than the current options of myomectomy or UAE.

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

- Stewart EA. Clinical practice. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1646-1655.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 96: alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387-400.

- Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, et al. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD005073.

- Paul GP, Naik SA, Madhu KN, et al. Complications of laparoscopic myomectomy: a single surgeon’s series of 1001 cases. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50:385-390.

- Flyckt R, Coyne K, Falcone T. Minimally invasive myomectomy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60:252-272.

- Bean EM, Cutner A, Holland T, et al. Laparoscopic myomectomy: a single-center retrospective review of 514 patients. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:485-493.

- Broder MS, Goodwin S, Chen G, et al. Comparison of longterm outcomes of myomectomy and uterine artery embolization. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(5 pt 1):864-868.

- Torng PL. Adhesion prevention in laparoscopic myomectomy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:7-11.

- Herrmann A, Torres-de la Roche LA, Krentel H, et al. Adhesions after laparoscopic myomectomy: incidence, risk factors, complications, and prevention. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2020;9:190-197.

- Pitter MC, Gargiulo AR, Bonaventura LM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following robot-assisted myomectomy. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:99-108.

- Khaw SC, Anderson RA, Lui MW. Systematic review of pregnancy outcomes after fertility-preserving treatment of uterine fibroids. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;40:429-444.

- Spies JB, Ascher SA, Roth AR, et al. Uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:29-34.

- Goodwin SC, Bradley LD, Lipman JC, et al. Uterine artery embolization versus myomectomy: a multicenter comparative study. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:14-21

- Jia JB, Nguyen ET, Ravilla A, et al. Comparison of uterine artery embolization and myomectomy: a long-term analysis of 863 patients. Am J Interv Radiol. 2020;5:1.

- Huang JY, Kafy S, Dugas A, et al. Failure of uterine fibroid embolization. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:30-35.

- Hesley GK, Gorny KR, Woodrum DA. MR-guided focused ultrasound for the treatment of uterine fibroids. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36:5-13.

- Rabinovici J, Inbar Y, Revel A, et al. Clinical improvement and shrinkage of uterine fibroids after thermal ablation by magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:771-777.

- Mindjuk I, Trumm CG, Herzog P, et al. MRI predictors of clinical success in MR-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) treatments of uterine fibroids: results from a single centre. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:1317-1328.

- Rabinovici J, David M, Fukunishi H, et al; MRgFUS Study Group. Pregnancy outcome after magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) for conservative treatment of uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:199-209.

- Anneveldt KJ, Oever HJV, Nijholt IM, et al. Systematic review of reproductive outcomes after high intensity focused ultrasound treatment of uterine fibroids. Eur J Radiol. 2021;141:109801.

- Bongers M, Gupta J, Garza-Leal JG, et al. The INTEGRITY trial: preservation of uterine-wall integrity 12 months after transcervical fibroid ablation with the Sonata system. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:299-303.

- Kim CH, Kim SR, Lee HA, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided radiofrequency myolysis for uterine myomas. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:559–563.

- Miller CE, Osman KM. Transcervical radiofrequency ablation of symptomatic uterine fibroids: 2-year results of the Sonata pivotal trial. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:345-349.

- Lukes A, Green MA. Three-year results of the Sonata pivotal trial of transcervical fibroid ablation for symptomatic uterine myomata. J Gynecol Surg. 2020;36:228-233.

- Guido RS, Macer JA, Abbott K, et al. Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation of fibroids: a prospective, clinical analysis of two years’ outcome from the Halt trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:139.

- Garza-Leal JG. Long-term clinical outcomes of transcervical radiofrequency ablation of uterine fibroids: the VITALITY study. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:19-23.

- Cope AG, Young RJ, Stewart EA. Non-extirpative treatments for uterine myomas: measuring success. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:442-452.e4.

- Berman JM, Shashoua A, Olson C, et al. Case series of reproductive outcomes after laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation of symptomatic myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:639-645.

- Jones S, O’Donovan P, Toub D. Radiofrequency ablation for treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:194839.

- Bergamini V, Ghezzi F, Cromi A, et al. Laparoscopic radiofrequency thermal ablation: a new approach to symptomatic uterine myomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:768-773.

- Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Bergamini V, et al. Midterm outcome of radiofrequency thermal ablation for symptomatic uterine myomas. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2081-2085.

- Szydłowska I, Starczewski A. Laparoscopic coagulation of uterine myomas with the use of a unipolar electrode. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:99-103.

- Bongers M, Quinn SD, Mueller MD et al. Evaluation of uterine patency following transcervical uterine fibroid ablation with the Sonata system (the OPEN clinical trial). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;242:122-125.

- Hai N, Hou Q, Ding X, et al. Ultrasound-guided transcervical radiofrequency ablation for symptomatic uterine adenomyosis. Br J Radiol. 2017;90:201601132.

- Polin M, Krenitsky N, Hur HC. Transcervical radiofrequency ablation for symptomatic adenomyosis: a case report. J Minim Invasive Gyn. 2021;28:S152-S153.

- Scarperi S, Pontrelli G, Campana C, et al. Laparoscopic radiofrequency thermal ablation for uterine adenomyosis. JSLS. 2015;19:e2015.00071.

Uterine fibroids are a common condition that affects up to 80% of reproductive-age women.1 Many women with fibroids are asymptomatic, but some experience symptoms that profoundly disrupt their lives, such as abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, and bulk symptoms including bladder and bowel dysfunction.2 Although hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment for symptomatic fibroids, many women seek more conservative management. Hormonal treatment, such as contraceptive pills, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, can improve heavy menstrual bleeding and anemia.3 Additionally, uterine artery embolization is a nonsurgical uterine-sparing option. However, these treatments are not ideal options for women who want to conceive.4 For reproductive-age women who desire future fertility, myomectomy has been the standard of care. Unfortunately, by the time patients become symptomatic from their fibroids and seek care, they may have numerous and/or sizable fibroids that result in high blood loss, surgical scarring, and the probable need for cesarean delivery (FIGURES 1 and 2).5

For patients who desire future conception, treatment of uterine fibroids poses a challenge in which optimizing symptomatic improvement must be balanced with protecting fertility and improving reproductive outcomes. In recent years, high-intensity focused ultrasound (FUS) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) have been presented as less invasive, uterine-sparing alternatives for fibroid treatment that could potentially provide that balance.

In this article, we briefly review the available uterine-sparing fibroid treatments and their outcomes and then focus specifically on RFA as a possible option to address the fibroid treatment gap for reproductive-age women who desire future fertility.

Overview of uterine-sparing treatments

Two approaches can be pursued for conservative fibroid treatment: fibroid removal and fibroid necrosis (TABLE 1). We focus this review on outcomes for the most widely available of these treatments.

Myomectomy

For reproductive-age women who wish to conceive, surgical removal of fibroids has been the standard of care for symptomatic patients. Myomectomy can be performed via laparotomy, laparoscopy, robot-assisted surgery, and hysteroscopy. The mode of surgery depends on the fibroid characteristics (size, number, and location) and the surgeon’s skill set. Although some variation in the data exists, overall surgical outcomes, including blood loss, postoperative pain, and length of stay, are generally more favorable for minimally invasive approaches compared with laparotomy, with no significant differences in fibroid recurrence or reproductive outcomes (live birth rate, miscarriage rate, and cesarean delivery rate).6 This comes at the expense of longer operating time compared with laparotomy.7

While improvement in abnormal uterine bleeding and pelvic pain is reliable and usually significant after myomectomy,8 reproductive implications also warrant consideration. Myomectomy is associated with subsequent uterine adhesion formation, with some studies finding rates up to 83% to 94% depending on the surgical approach and the number of fibroids removed.9 These adhesions can impair fertility success.10 Myomectomy also is associated with high rates of cesarean delivery,5 invasive placentation (including placenta accreta spectrum),11 and uterine rupture.12 While the latter 2 complications are rare, they potentially can be catastrophic and should be kept in mind.

Continue to: Uterine artery embolization...

Uterine artery embolization

As a nonsurgical alternative to myomectomy, uterine artery embolization (UAE) has gained popularity as a conservative fibroid treatment since it was introduced in 1995. It is less invasive than myomectomy, a benefit for patients who decline surgery or are not ideal candidates for surgery.13 Evidence suggests that UAE produces overall comparable symptomatic improvement compared with myomectomy. One study showed no significant differences between UAE and myomectomy in terms of decreased uterine volume and menstrual bleeding at 6-month follow-up.14 In terms of long-term outcomes, a large multicenter study showed no significant difference in reintervention rates at 7 years posttreatment between UAE and myomectomy (8.9% vs 11.2%, respectively), and a significantly higher rate of improved menstrual bleeding with UAE (79.4% vs 49.5%), with no significant difference in bulk symptoms.15 The evidence is not entirely consistent, as other studies have shown increased rates of reintervention with UAE,8,16 but overall UAE can be considered a reasonable alternative to myomectomy in terms of symptomatic improvement.

Pregnancy outcomes data, however, are mixed, and UAE often is not recommended for patients with future fertility plans. In a large review article that compared minimally invasive fibroid treatments, UAE was associated with a lower live birth rate compared with myomectomy and ablation techniques (60.6% for UAE, 75.6% for myomectomy, and 70.5% for ablation), and it also had the highest rate of miscarriage (27.4% for UAE vs 19.0% for myomectomy and 11.9% for ablation) and abnormal placentation.12 While UAE remains an effective option for conservative treatment of symptomatic fibroids, it appears to have a worse impact on reproductive outcomes compared with myomectomy or ablative treatments.

Magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound

Emerging as a noninvasive ablation treatment for fibroids, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) uses targeted high-intensity ultrasound pulses to cause thermal and mechanical fibroid tissue disruption.17 Data on this treatment are less robust given that it is newer than myomectomy or UAE. One study showed a decrease in fibroid volume by 12% at 1 month and 15% at 6 months, with 37.1% of patients reporting marked improvement in symptoms and an additional 31.4% reporting partial improvement; these are modest numbers compared with other treatment approaches.18 Another study showed more favorable outcomes, with 74% of patients reporting clinically significant improvement in bleeding and pain, and a 12.7% reintervention rate, comparable to rates reported for UAE and myomectomy.19

Because MRgFUS is newer than UAE or myomectomy, data are limited in terms of pregnancy outcomes, particularly because initial trials excluded women with future fertility plans due to lack of knowledge regarding pregnancy safety. A follow-up case series from one of the initial studies showed a decreased miscarriage rate compared with UAE, a term delivery rate of 93%, and a similar rate of abnormal placentation.20 A more recent systematic review concluded that reproductive outcomes were noninferior to myomectomy; however, the outcomes data for MRgFUS were heterogenous and many studies did not report pregnancy rates.21

Overall, MRgFUS appears to be an effective alternative approach for symptomatic fibroids, but the long-term data are not yet conclusive and information on pregnancy safety and outcomes largely is lacking. Recent reviews have not made definitive statements on whether MRgFUS should be offered to patients desiring future fertility.

Continue to: RFA is a promising option...

RFA is a promising option

RFA is another noninvasive fibroid ablation technique that has become more widely adopted in recent years. Here, we describe the basics of RFA and its impact on fibroid symptoms and reproductive outcomes.

The RFA technique

RFA uses hyperthermic energy from a handpiece and real-time ultrasound for targeted coagulative necrosis via a laparoscopic (L-RFA) or transcervical (TC-RFA) approach.22 A comparison between the 2 devices available on the market in the United States is shown in TABLE 2. Ultrasound guidance allows placement of radiofrequency needles directly into the fibroid to target local treatment to the fibroid tissue only. Once the fibroid undergoes coagulative necrosis, the process of fibroid resorption and volume reduction occurs over weeks to months, depending on the fibroid size.

Impact on fibroid symptoms

Both laparoscopic and transcervical RFA approaches have shown significant decreases in pelvic pain and heavy menstrual bleeding associated with fibroids and a low reintervention rate that emphasizes the durability of their impact.

A feasibility and safety study of a TC-RFA device prior to the primary clinical trials found only a 4.3% reintervention rate in the first 18 months postprocedure.23 The pivotal clinical trial of a TC-RFA device that followed also reported a low 5.5% reintervention rate in the first 24 months postprocedure, with significant improvement in health-related quality-of-life and high patient satisfaction24 (results shown in TABLE 2, along with trial results for an L-RFA device). A subsequent study of TC-RFA reported that symptomatic improvement persisted at 3-year follow-up, with a 9.2% reintervention rate comparable to existing fibroid treatments such as myomectomy and UAE.25 The original L-RFA trial also has shown similar positive results at 2-year follow-up, with a low reintervention rate of 4.8% after treatment, and similar patient satisfaction and quality-of-life improvements as TC-RFA.26 While long-term data are limited by only recent approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of a TC-RFA device in 2018, one study followed clinical trial patients for a mean duration of 64 months. This study found no surgical reinterventions in the first 3.5 years posttreatment and a persistent reduction in fibroid symptoms from baseline 64.9 points to 27.6 points, as assessed by a validated symptom severity scale (out of 100 points).27 Similar improvements in health-related quality-of life-were also found to persist for years posttreatment.4

In a large systematic review that compared L-RFA, MRgFUS, UAE, and myomectomy, L-RFA had similar improvement rates in quality-of-life and symptom severity scores compared with myomectomy, with no significant difference in reintervention rates.28 This review also noted minimal heterogeneity among RFA meta-analyses data in contrast to significant heterogeneity among UAE and myomectomy data.

Reproductive outcomes

Similar to MRgFUS, the initial studies of RFA devices largely excluded women with future fertility plans, as data on safety were lacking. However, many RFA devices are now on the market across the globe, and subsequent pregnancies have been tracked and reported.

A large case series that included clinical trials and commercial settings reported a miscarriage rate (13.3%) similar to that of the general obstetric population and no cases of uterine rupture, invasive placentation, preterm delivery, or placental abruption.29 Other case series have reported live birth rates similar those with myomectomy, and safe and favorable pregnancy outcomes with RFA have been supported by larger systematic reviews of all ablation techniques.12

Continue to: Uterine impact...

Uterine impact

One study of TC-RFA patients showed a greater than 65% reduction in fibroid volume (with a 90% reduction in fibroid volume for fibroids larger than 6 cm prior to RFA), and 54% of patients reported complete resolution of symptoms, with another 36% reporting decreased symptoms.30 Similar decreases in fibroid volume, ranging from 65% to 84%, have been reported in numerous follow-up studies, with significant decreases in bleeding and pain in 78% to 88% of patients.23,31-33 Additionally, a large secondary analysis of a TC-RFA clinical trial showed that patients did not have any significant decrease in uterine wall thickness or integrity on follow-up with magnetic resonance imaging compared with baseline measurements, and they did not have any new myometrial scars (assessed as nonperfused linear areas).22

As with other ablation techniques, most data on RFA pregnancy outcomes come from case series, and further research and evaluation are needed. Existing studies, however, have demonstrated promising aspects of RFA that argue its usefulness in women with fertility plans.

A prospective trial that evaluated intrauterine adhesion formation with use of a TC-RFA device found no new adhesions on 6-week follow-up hysteroscopy compared with baseline pre-RFA hysteroscopy.34 Because intrauterine adhesion formation and uterine rupture are both significant concerns with other uterine-sparing fibroid treatment approaches such as myomectomy, these findings suggest that RFA may be a better alternative for women who are planning future pregnancies, as they may have increased fertility success and decreased catastrophic complications.

The consensus is growing that RFA is a safe and effective option for women who desire minimally invasive fibroid treatment and want to preserve fertility.

Unique benefits of RFA

In this article, we highlight RFA as an emerging treatment option for fibroid management, particularly for women who desire a uterine-sparing approach to preserve their reproductive options. Although myomectomy has been the standard of care for many years, with UAE as the alternative nonsurgical treatment, neither approach provides the best balance between symptomatic improvement and reproductive outcomes, and neither is without pregnancy risks. In addition, many women with symptomatic fibroids do not desire future conception but decline fibroid removal for religious or personal reasons. RFA offers these women an alternative minimally invasive option for uterine-sparing fibroid treatment.

RFA presents a unique “incision-free” fibroid treatment that is truly minimally invasive. This technique minimizes the risks associated with myomectomy, such as intra-abdominal adhesions, intrauterine adhesions (Asherman syndrome), need for cesarean delivery, and pregnancy complications such as uterine rupture or invasive placentation. Furthermore, the evolution of an RFA transcervical approach has enabled treatment with no abdominal or uterine incisions, thus offering all the above reproductive benefits as well as the operative benefits of a faster recovery, less pain, and less risk of intraperitoneal surgical complications.

While many women desire uterine-sparing fibroid treatment even without future fertility plans, the larger question is whether we should treat fibroids more strategically for women who desire future fertility. Myomectomy and UAE are effective and reliable in terms of fibroid symptomatic improvement, but RFA promises more beneficial reproductive outcomes. The ability to avoid uterine myometrial incisions and still attain significant symptomatic improvement should be prioritized in these patients.

Currently, RFA is not approved by the FDA as a fertility-enabling treatment, and these patients have been largely excluded from RFA studies. However, the reproductive-age patient who desires future conception may benefit most from RFA. Furthermore, RFA technology also could address the gap in uterine-sparing treatment for reproductive-age women with adenomyosis. Although a complete review of adenomyosis treatment is beyond the scope of this article, recent studies show that RFA produces similar improvement in both uterine volume and symptom severity in women with adenomyosis.35-37 ●

The RFA data suggest that both laparoscopic and transcervical RFA offer a safe and effective alternative treatment option for patients with symptomatic fibroids who seek uterine-sparing treatment, and transcervical RFA offers the least invasive treatment option. Women with fibroids who wish to conceive currently face a challenging treatment gap in clinical medicine, and future research is needed to address this concern in these patients. RFA is promising and appears to be a better fertility-enabling conservative fibroid treatment than the current options of myomectomy or UAE.

Uterine fibroids are a common condition that affects up to 80% of reproductive-age women.1 Many women with fibroids are asymptomatic, but some experience symptoms that profoundly disrupt their lives, such as abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, and bulk symptoms including bladder and bowel dysfunction.2 Although hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment for symptomatic fibroids, many women seek more conservative management. Hormonal treatment, such as contraceptive pills, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, can improve heavy menstrual bleeding and anemia.3 Additionally, uterine artery embolization is a nonsurgical uterine-sparing option. However, these treatments are not ideal options for women who want to conceive.4 For reproductive-age women who desire future fertility, myomectomy has been the standard of care. Unfortunately, by the time patients become symptomatic from their fibroids and seek care, they may have numerous and/or sizable fibroids that result in high blood loss, surgical scarring, and the probable need for cesarean delivery (FIGURES 1 and 2).5

For patients who desire future conception, treatment of uterine fibroids poses a challenge in which optimizing symptomatic improvement must be balanced with protecting fertility and improving reproductive outcomes. In recent years, high-intensity focused ultrasound (FUS) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) have been presented as less invasive, uterine-sparing alternatives for fibroid treatment that could potentially provide that balance.

In this article, we briefly review the available uterine-sparing fibroid treatments and their outcomes and then focus specifically on RFA as a possible option to address the fibroid treatment gap for reproductive-age women who desire future fertility.

Overview of uterine-sparing treatments

Two approaches can be pursued for conservative fibroid treatment: fibroid removal and fibroid necrosis (TABLE 1). We focus this review on outcomes for the most widely available of these treatments.

Myomectomy

For reproductive-age women who wish to conceive, surgical removal of fibroids has been the standard of care for symptomatic patients. Myomectomy can be performed via laparotomy, laparoscopy, robot-assisted surgery, and hysteroscopy. The mode of surgery depends on the fibroid characteristics (size, number, and location) and the surgeon’s skill set. Although some variation in the data exists, overall surgical outcomes, including blood loss, postoperative pain, and length of stay, are generally more favorable for minimally invasive approaches compared with laparotomy, with no significant differences in fibroid recurrence or reproductive outcomes (live birth rate, miscarriage rate, and cesarean delivery rate).6 This comes at the expense of longer operating time compared with laparotomy.7

While improvement in abnormal uterine bleeding and pelvic pain is reliable and usually significant after myomectomy,8 reproductive implications also warrant consideration. Myomectomy is associated with subsequent uterine adhesion formation, with some studies finding rates up to 83% to 94% depending on the surgical approach and the number of fibroids removed.9 These adhesions can impair fertility success.10 Myomectomy also is associated with high rates of cesarean delivery,5 invasive placentation (including placenta accreta spectrum),11 and uterine rupture.12 While the latter 2 complications are rare, they potentially can be catastrophic and should be kept in mind.

Continue to: Uterine artery embolization...

Uterine artery embolization

As a nonsurgical alternative to myomectomy, uterine artery embolization (UAE) has gained popularity as a conservative fibroid treatment since it was introduced in 1995. It is less invasive than myomectomy, a benefit for patients who decline surgery or are not ideal candidates for surgery.13 Evidence suggests that UAE produces overall comparable symptomatic improvement compared with myomectomy. One study showed no significant differences between UAE and myomectomy in terms of decreased uterine volume and menstrual bleeding at 6-month follow-up.14 In terms of long-term outcomes, a large multicenter study showed no significant difference in reintervention rates at 7 years posttreatment between UAE and myomectomy (8.9% vs 11.2%, respectively), and a significantly higher rate of improved menstrual bleeding with UAE (79.4% vs 49.5%), with no significant difference in bulk symptoms.15 The evidence is not entirely consistent, as other studies have shown increased rates of reintervention with UAE,8,16 but overall UAE can be considered a reasonable alternative to myomectomy in terms of symptomatic improvement.

Pregnancy outcomes data, however, are mixed, and UAE often is not recommended for patients with future fertility plans. In a large review article that compared minimally invasive fibroid treatments, UAE was associated with a lower live birth rate compared with myomectomy and ablation techniques (60.6% for UAE, 75.6% for myomectomy, and 70.5% for ablation), and it also had the highest rate of miscarriage (27.4% for UAE vs 19.0% for myomectomy and 11.9% for ablation) and abnormal placentation.12 While UAE remains an effective option for conservative treatment of symptomatic fibroids, it appears to have a worse impact on reproductive outcomes compared with myomectomy or ablative treatments.

Magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound

Emerging as a noninvasive ablation treatment for fibroids, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) uses targeted high-intensity ultrasound pulses to cause thermal and mechanical fibroid tissue disruption.17 Data on this treatment are less robust given that it is newer than myomectomy or UAE. One study showed a decrease in fibroid volume by 12% at 1 month and 15% at 6 months, with 37.1% of patients reporting marked improvement in symptoms and an additional 31.4% reporting partial improvement; these are modest numbers compared with other treatment approaches.18 Another study showed more favorable outcomes, with 74% of patients reporting clinically significant improvement in bleeding and pain, and a 12.7% reintervention rate, comparable to rates reported for UAE and myomectomy.19

Because MRgFUS is newer than UAE or myomectomy, data are limited in terms of pregnancy outcomes, particularly because initial trials excluded women with future fertility plans due to lack of knowledge regarding pregnancy safety. A follow-up case series from one of the initial studies showed a decreased miscarriage rate compared with UAE, a term delivery rate of 93%, and a similar rate of abnormal placentation.20 A more recent systematic review concluded that reproductive outcomes were noninferior to myomectomy; however, the outcomes data for MRgFUS were heterogenous and many studies did not report pregnancy rates.21

Overall, MRgFUS appears to be an effective alternative approach for symptomatic fibroids, but the long-term data are not yet conclusive and information on pregnancy safety and outcomes largely is lacking. Recent reviews have not made definitive statements on whether MRgFUS should be offered to patients desiring future fertility.

Continue to: RFA is a promising option...

RFA is a promising option

RFA is another noninvasive fibroid ablation technique that has become more widely adopted in recent years. Here, we describe the basics of RFA and its impact on fibroid symptoms and reproductive outcomes.

The RFA technique

RFA uses hyperthermic energy from a handpiece and real-time ultrasound for targeted coagulative necrosis via a laparoscopic (L-RFA) or transcervical (TC-RFA) approach.22 A comparison between the 2 devices available on the market in the United States is shown in TABLE 2. Ultrasound guidance allows placement of radiofrequency needles directly into the fibroid to target local treatment to the fibroid tissue only. Once the fibroid undergoes coagulative necrosis, the process of fibroid resorption and volume reduction occurs over weeks to months, depending on the fibroid size.

Impact on fibroid symptoms

Both laparoscopic and transcervical RFA approaches have shown significant decreases in pelvic pain and heavy menstrual bleeding associated with fibroids and a low reintervention rate that emphasizes the durability of their impact.

A feasibility and safety study of a TC-RFA device prior to the primary clinical trials found only a 4.3% reintervention rate in the first 18 months postprocedure.23 The pivotal clinical trial of a TC-RFA device that followed also reported a low 5.5% reintervention rate in the first 24 months postprocedure, with significant improvement in health-related quality-of-life and high patient satisfaction24 (results shown in TABLE 2, along with trial results for an L-RFA device). A subsequent study of TC-RFA reported that symptomatic improvement persisted at 3-year follow-up, with a 9.2% reintervention rate comparable to existing fibroid treatments such as myomectomy and UAE.25 The original L-RFA trial also has shown similar positive results at 2-year follow-up, with a low reintervention rate of 4.8% after treatment, and similar patient satisfaction and quality-of-life improvements as TC-RFA.26 While long-term data are limited by only recent approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of a TC-RFA device in 2018, one study followed clinical trial patients for a mean duration of 64 months. This study found no surgical reinterventions in the first 3.5 years posttreatment and a persistent reduction in fibroid symptoms from baseline 64.9 points to 27.6 points, as assessed by a validated symptom severity scale (out of 100 points).27 Similar improvements in health-related quality-of life-were also found to persist for years posttreatment.4

In a large systematic review that compared L-RFA, MRgFUS, UAE, and myomectomy, L-RFA had similar improvement rates in quality-of-life and symptom severity scores compared with myomectomy, with no significant difference in reintervention rates.28 This review also noted minimal heterogeneity among RFA meta-analyses data in contrast to significant heterogeneity among UAE and myomectomy data.

Reproductive outcomes

Similar to MRgFUS, the initial studies of RFA devices largely excluded women with future fertility plans, as data on safety were lacking. However, many RFA devices are now on the market across the globe, and subsequent pregnancies have been tracked and reported.

A large case series that included clinical trials and commercial settings reported a miscarriage rate (13.3%) similar to that of the general obstetric population and no cases of uterine rupture, invasive placentation, preterm delivery, or placental abruption.29 Other case series have reported live birth rates similar those with myomectomy, and safe and favorable pregnancy outcomes with RFA have been supported by larger systematic reviews of all ablation techniques.12

Continue to: Uterine impact...

Uterine impact

One study of TC-RFA patients showed a greater than 65% reduction in fibroid volume (with a 90% reduction in fibroid volume for fibroids larger than 6 cm prior to RFA), and 54% of patients reported complete resolution of symptoms, with another 36% reporting decreased symptoms.30 Similar decreases in fibroid volume, ranging from 65% to 84%, have been reported in numerous follow-up studies, with significant decreases in bleeding and pain in 78% to 88% of patients.23,31-33 Additionally, a large secondary analysis of a TC-RFA clinical trial showed that patients did not have any significant decrease in uterine wall thickness or integrity on follow-up with magnetic resonance imaging compared with baseline measurements, and they did not have any new myometrial scars (assessed as nonperfused linear areas).22

As with other ablation techniques, most data on RFA pregnancy outcomes come from case series, and further research and evaluation are needed. Existing studies, however, have demonstrated promising aspects of RFA that argue its usefulness in women with fertility plans.

A prospective trial that evaluated intrauterine adhesion formation with use of a TC-RFA device found no new adhesions on 6-week follow-up hysteroscopy compared with baseline pre-RFA hysteroscopy.34 Because intrauterine adhesion formation and uterine rupture are both significant concerns with other uterine-sparing fibroid treatment approaches such as myomectomy, these findings suggest that RFA may be a better alternative for women who are planning future pregnancies, as they may have increased fertility success and decreased catastrophic complications.

The consensus is growing that RFA is a safe and effective option for women who desire minimally invasive fibroid treatment and want to preserve fertility.

Unique benefits of RFA

In this article, we highlight RFA as an emerging treatment option for fibroid management, particularly for women who desire a uterine-sparing approach to preserve their reproductive options. Although myomectomy has been the standard of care for many years, with UAE as the alternative nonsurgical treatment, neither approach provides the best balance between symptomatic improvement and reproductive outcomes, and neither is without pregnancy risks. In addition, many women with symptomatic fibroids do not desire future conception but decline fibroid removal for religious or personal reasons. RFA offers these women an alternative minimally invasive option for uterine-sparing fibroid treatment.

RFA presents a unique “incision-free” fibroid treatment that is truly minimally invasive. This technique minimizes the risks associated with myomectomy, such as intra-abdominal adhesions, intrauterine adhesions (Asherman syndrome), need for cesarean delivery, and pregnancy complications such as uterine rupture or invasive placentation. Furthermore, the evolution of an RFA transcervical approach has enabled treatment with no abdominal or uterine incisions, thus offering all the above reproductive benefits as well as the operative benefits of a faster recovery, less pain, and less risk of intraperitoneal surgical complications.

While many women desire uterine-sparing fibroid treatment even without future fertility plans, the larger question is whether we should treat fibroids more strategically for women who desire future fertility. Myomectomy and UAE are effective and reliable in terms of fibroid symptomatic improvement, but RFA promises more beneficial reproductive outcomes. The ability to avoid uterine myometrial incisions and still attain significant symptomatic improvement should be prioritized in these patients.

Currently, RFA is not approved by the FDA as a fertility-enabling treatment, and these patients have been largely excluded from RFA studies. However, the reproductive-age patient who desires future conception may benefit most from RFA. Furthermore, RFA technology also could address the gap in uterine-sparing treatment for reproductive-age women with adenomyosis. Although a complete review of adenomyosis treatment is beyond the scope of this article, recent studies show that RFA produces similar improvement in both uterine volume and symptom severity in women with adenomyosis.35-37 ●

The RFA data suggest that both laparoscopic and transcervical RFA offer a safe and effective alternative treatment option for patients with symptomatic fibroids who seek uterine-sparing treatment, and transcervical RFA offers the least invasive treatment option. Women with fibroids who wish to conceive currently face a challenging treatment gap in clinical medicine, and future research is needed to address this concern in these patients. RFA is promising and appears to be a better fertility-enabling conservative fibroid treatment than the current options of myomectomy or UAE.

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

- Stewart EA. Clinical practice. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1646-1655.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 96: alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387-400.

- Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, et al. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD005073.

- Paul GP, Naik SA, Madhu KN, et al. Complications of laparoscopic myomectomy: a single surgeon’s series of 1001 cases. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50:385-390.

- Flyckt R, Coyne K, Falcone T. Minimally invasive myomectomy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60:252-272.

- Bean EM, Cutner A, Holland T, et al. Laparoscopic myomectomy: a single-center retrospective review of 514 patients. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:485-493.

- Broder MS, Goodwin S, Chen G, et al. Comparison of longterm outcomes of myomectomy and uterine artery embolization. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(5 pt 1):864-868.

- Torng PL. Adhesion prevention in laparoscopic myomectomy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:7-11.

- Herrmann A, Torres-de la Roche LA, Krentel H, et al. Adhesions after laparoscopic myomectomy: incidence, risk factors, complications, and prevention. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2020;9:190-197.

- Pitter MC, Gargiulo AR, Bonaventura LM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following robot-assisted myomectomy. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:99-108.

- Khaw SC, Anderson RA, Lui MW. Systematic review of pregnancy outcomes after fertility-preserving treatment of uterine fibroids. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;40:429-444.

- Spies JB, Ascher SA, Roth AR, et al. Uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:29-34.

- Goodwin SC, Bradley LD, Lipman JC, et al. Uterine artery embolization versus myomectomy: a multicenter comparative study. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:14-21

- Jia JB, Nguyen ET, Ravilla A, et al. Comparison of uterine artery embolization and myomectomy: a long-term analysis of 863 patients. Am J Interv Radiol. 2020;5:1.

- Huang JY, Kafy S, Dugas A, et al. Failure of uterine fibroid embolization. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:30-35.

- Hesley GK, Gorny KR, Woodrum DA. MR-guided focused ultrasound for the treatment of uterine fibroids. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36:5-13.

- Rabinovici J, Inbar Y, Revel A, et al. Clinical improvement and shrinkage of uterine fibroids after thermal ablation by magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:771-777.

- Mindjuk I, Trumm CG, Herzog P, et al. MRI predictors of clinical success in MR-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) treatments of uterine fibroids: results from a single centre. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:1317-1328.

- Rabinovici J, David M, Fukunishi H, et al; MRgFUS Study Group. Pregnancy outcome after magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) for conservative treatment of uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:199-209.

- Anneveldt KJ, Oever HJV, Nijholt IM, et al. Systematic review of reproductive outcomes after high intensity focused ultrasound treatment of uterine fibroids. Eur J Radiol. 2021;141:109801.

- Bongers M, Gupta J, Garza-Leal JG, et al. The INTEGRITY trial: preservation of uterine-wall integrity 12 months after transcervical fibroid ablation with the Sonata system. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:299-303.

- Kim CH, Kim SR, Lee HA, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided radiofrequency myolysis for uterine myomas. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:559–563.

- Miller CE, Osman KM. Transcervical radiofrequency ablation of symptomatic uterine fibroids: 2-year results of the Sonata pivotal trial. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:345-349.

- Lukes A, Green MA. Three-year results of the Sonata pivotal trial of transcervical fibroid ablation for symptomatic uterine myomata. J Gynecol Surg. 2020;36:228-233.

- Guido RS, Macer JA, Abbott K, et al. Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation of fibroids: a prospective, clinical analysis of two years’ outcome from the Halt trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:139.

- Garza-Leal JG. Long-term clinical outcomes of transcervical radiofrequency ablation of uterine fibroids: the VITALITY study. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:19-23.

- Cope AG, Young RJ, Stewart EA. Non-extirpative treatments for uterine myomas: measuring success. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:442-452.e4.

- Berman JM, Shashoua A, Olson C, et al. Case series of reproductive outcomes after laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation of symptomatic myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:639-645.

- Jones S, O’Donovan P, Toub D. Radiofrequency ablation for treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:194839.

- Bergamini V, Ghezzi F, Cromi A, et al. Laparoscopic radiofrequency thermal ablation: a new approach to symptomatic uterine myomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:768-773.

- Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Bergamini V, et al. Midterm outcome of radiofrequency thermal ablation for symptomatic uterine myomas. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2081-2085.

- Szydłowska I, Starczewski A. Laparoscopic coagulation of uterine myomas with the use of a unipolar electrode. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:99-103.

- Bongers M, Quinn SD, Mueller MD et al. Evaluation of uterine patency following transcervical uterine fibroid ablation with the Sonata system (the OPEN clinical trial). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;242:122-125.

- Hai N, Hou Q, Ding X, et al. Ultrasound-guided transcervical radiofrequency ablation for symptomatic uterine adenomyosis. Br J Radiol. 2017;90:201601132.

- Polin M, Krenitsky N, Hur HC. Transcervical radiofrequency ablation for symptomatic adenomyosis: a case report. J Minim Invasive Gyn. 2021;28:S152-S153.

- Scarperi S, Pontrelli G, Campana C, et al. Laparoscopic radiofrequency thermal ablation for uterine adenomyosis. JSLS. 2015;19:e2015.00071.

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

- Stewart EA. Clinical practice. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1646-1655.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 96: alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387-400.

- Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, et al. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD005073.

- Paul GP, Naik SA, Madhu KN, et al. Complications of laparoscopic myomectomy: a single surgeon’s series of 1001 cases. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50:385-390.

- Flyckt R, Coyne K, Falcone T. Minimally invasive myomectomy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60:252-272.

- Bean EM, Cutner A, Holland T, et al. Laparoscopic myomectomy: a single-center retrospective review of 514 patients. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:485-493.

- Broder MS, Goodwin S, Chen G, et al. Comparison of longterm outcomes of myomectomy and uterine artery embolization. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(5 pt 1):864-868.

- Torng PL. Adhesion prevention in laparoscopic myomectomy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:7-11.

- Herrmann A, Torres-de la Roche LA, Krentel H, et al. Adhesions after laparoscopic myomectomy: incidence, risk factors, complications, and prevention. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2020;9:190-197.

- Pitter MC, Gargiulo AR, Bonaventura LM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following robot-assisted myomectomy. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:99-108.

- Khaw SC, Anderson RA, Lui MW. Systematic review of pregnancy outcomes after fertility-preserving treatment of uterine fibroids. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;40:429-444.

- Spies JB, Ascher SA, Roth AR, et al. Uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:29-34.

- Goodwin SC, Bradley LD, Lipman JC, et al. Uterine artery embolization versus myomectomy: a multicenter comparative study. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:14-21

- Jia JB, Nguyen ET, Ravilla A, et al. Comparison of uterine artery embolization and myomectomy: a long-term analysis of 863 patients. Am J Interv Radiol. 2020;5:1.

- Huang JY, Kafy S, Dugas A, et al. Failure of uterine fibroid embolization. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:30-35.

- Hesley GK, Gorny KR, Woodrum DA. MR-guided focused ultrasound for the treatment of uterine fibroids. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36:5-13.

- Rabinovici J, Inbar Y, Revel A, et al. Clinical improvement and shrinkage of uterine fibroids after thermal ablation by magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:771-777.

- Mindjuk I, Trumm CG, Herzog P, et al. MRI predictors of clinical success in MR-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) treatments of uterine fibroids: results from a single centre. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:1317-1328.

- Rabinovici J, David M, Fukunishi H, et al; MRgFUS Study Group. Pregnancy outcome after magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) for conservative treatment of uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:199-209.

- Anneveldt KJ, Oever HJV, Nijholt IM, et al. Systematic review of reproductive outcomes after high intensity focused ultrasound treatment of uterine fibroids. Eur J Radiol. 2021;141:109801.

- Bongers M, Gupta J, Garza-Leal JG, et al. The INTEGRITY trial: preservation of uterine-wall integrity 12 months after transcervical fibroid ablation with the Sonata system. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:299-303.

- Kim CH, Kim SR, Lee HA, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided radiofrequency myolysis for uterine myomas. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:559–563.

- Miller CE, Osman KM. Transcervical radiofrequency ablation of symptomatic uterine fibroids: 2-year results of the Sonata pivotal trial. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:345-349.

- Lukes A, Green MA. Three-year results of the Sonata pivotal trial of transcervical fibroid ablation for symptomatic uterine myomata. J Gynecol Surg. 2020;36:228-233.

- Guido RS, Macer JA, Abbott K, et al. Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation of fibroids: a prospective, clinical analysis of two years’ outcome from the Halt trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:139.

- Garza-Leal JG. Long-term clinical outcomes of transcervical radiofrequency ablation of uterine fibroids: the VITALITY study. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:19-23.

- Cope AG, Young RJ, Stewart EA. Non-extirpative treatments for uterine myomas: measuring success. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:442-452.e4.

- Berman JM, Shashoua A, Olson C, et al. Case series of reproductive outcomes after laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation of symptomatic myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:639-645.

- Jones S, O’Donovan P, Toub D. Radiofrequency ablation for treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:194839.

- Bergamini V, Ghezzi F, Cromi A, et al. Laparoscopic radiofrequency thermal ablation: a new approach to symptomatic uterine myomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:768-773.

- Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Bergamini V, et al. Midterm outcome of radiofrequency thermal ablation for symptomatic uterine myomas. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2081-2085.

- Szydłowska I, Starczewski A. Laparoscopic coagulation of uterine myomas with the use of a unipolar electrode. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:99-103.

- Bongers M, Quinn SD, Mueller MD et al. Evaluation of uterine patency following transcervical uterine fibroid ablation with the Sonata system (the OPEN clinical trial). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;242:122-125.

- Hai N, Hou Q, Ding X, et al. Ultrasound-guided transcervical radiofrequency ablation for symptomatic uterine adenomyosis. Br J Radiol. 2017;90:201601132.

- Polin M, Krenitsky N, Hur HC. Transcervical radiofrequency ablation for symptomatic adenomyosis: a case report. J Minim Invasive Gyn. 2021;28:S152-S153.

- Scarperi S, Pontrelli G, Campana C, et al. Laparoscopic radiofrequency thermal ablation for uterine adenomyosis. JSLS. 2015;19:e2015.00071.

Electrosurgical hysteroscopy: Principles and expert techniques for optimizing the resectoscope loop

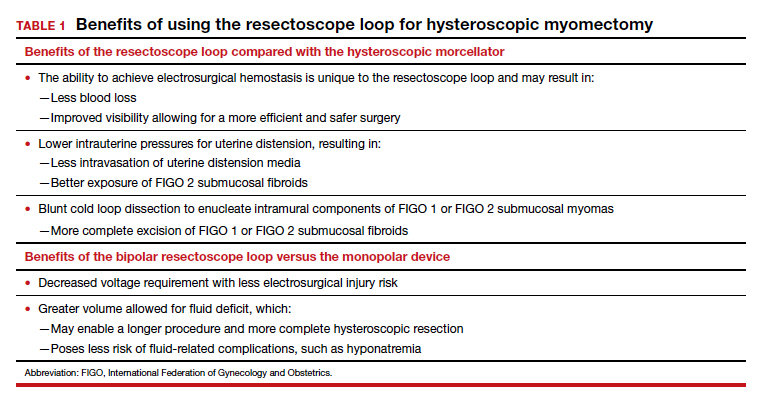

Hysteroscopic mechanical morcellators have gained popularity given their ease of use. Consequently, the resectoscope loop is being used less frequently, which has resulted in less familiarity with this device. The resectoscope loop, however, not only is cost effective but also allows for multiple distinct advantages, such as cold loop dissection of myomas and the ability to obtain electrosurgical hemostasis during operative hysteroscopy.

In this article, we review the basics of electrosurgical principles, compare outcomes associated with monopolar and bipolar resectoscopes, and discuss tips and tricks for optimizing surgical techniques when using the resectoscope loop for hysteroscopic myomectomy.

Evolution of hysteroscopy

The term hysteroscopy comes from the Greek words hystera, for uterus, and skopeo, meaning “to see.” The idea to investigate the uterus dates back to the year 1000 when physicians used a mirror with light to peer into the vaginal vault.

The first known successful hysteroscopy occurred in 1869 when Pantaleoni used an endoscope with a light source to identify uterine polyps in a 60-year-old woman with abnormal uterine bleeding. In 1898, Simon Duplay and Spiro Clado published the first textbook on hysteroscopy in which they described several models of hysteroscopic instruments and techniques.

In the 1950s, Harold Horace Hopkins and Karl Storz modified the shape and length of lenses within the endoscope by substituting longer cylindrical lenses for the old spherical lenses; this permitted improved image brightness and sharpness as well as a smaller diameter of the hysteroscope. Between the 1970s and 1980s, technological improvements allowed for the creation of practical and usable hysteroscopic instruments such as the resectoscope. The resectoscope, originally used in urology for transurethral resection of the prostate, was modified for hysteroscopy by incorporating the use of electrosurgical currents to aid in procedures.

Over the past few decades, continued refinements in technology have improved visualization and surgical techniques. For example, image clarity has been markedly improved, and narrow hysteroscope diameters, as small as 3 to 5 mm, require minimal to no cervical dilation.

Monopolar and bipolar resectoscopes

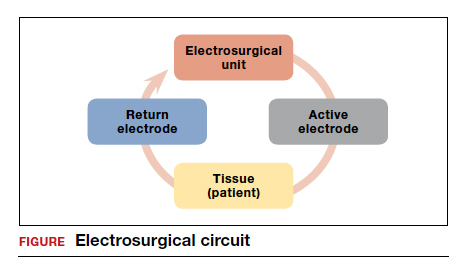

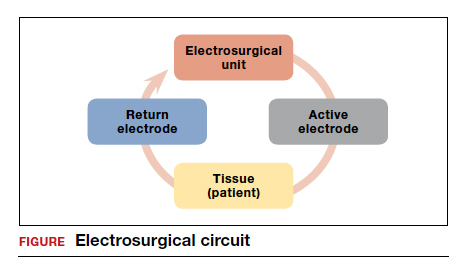

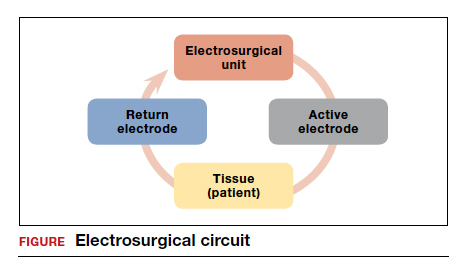

Electrosurgery is the application of an alternating electrical current to tissue to achieve the clinical effects of surgical cutting or hemostasis via cell vaporization or coagulation. Current runs from the electrosurgical unit (ESU) to the active electrode of the surgical instrument, then goes from the active electrode through the patient’s tissue to the return electrode, and then travels back to the ESU. This flow of current creates an electrical circuit (FIGURE).

All electrosurgical devices have an active and a return electrode. The difference between monopolar and bipolar resectoscope devices lies in how the resectoscope loop is constructed. Bipolar resectoscope loops house the active and return electrodes on the same tip of the surgical device, which limits how much of the current flows through the patient. Alternatively, monopolar resectoscopes have only the active electrode on the tip of the device and the return electrode is off the surgical field, so the current flows through more of the patient. On monopolar electrosurgical devices, the current runs from the ESU to the active electrode (monopolar loop), which is then applied to tissue to produce the desired tissue effect. The current then travels via a path of least resistance from the surgical field through the patient to the return electrode, which is usually placed on the patient’s thigh, and then back to the ESU. The return electrode is often referred to as the grounding pad.

Continue to: How monopolar energy works...

How monopolar energy works

When first developed, all resectoscopes used monopolar energy. As such, throughout the 1990s, the monopolar resectoscope was the gold standard for performing electrosurgical hysteroscopy. Because the current travels a long distance between the active and the return electrode in a monopolar setup, a hypotonic, nonelectrolyte-rich medium (a poor conductor), such as glycine 1.5%, mannitol 5%, or sorbitol 3%, must be used. If an electrolyte-rich medium, such as normal saline, is used with a monopolar device, the current would be dispersed throughout the medium outside the operative field, causing unwanted tissue effects.

Although nonelectrolyte distension media improve visibility when encountering bleeding, they can be associated with hyponatremia, hyperglycemia, and even lifethreatening cerebral edema. Furthermore, glycine use is contraindicated in patients with renal or hepatic failure since oxidative deamination may cause hyperammonemia. Because of these numerous risk factors, the fluid deficit for hypotonic, nonelectrolyte distension media is limited to 1,000 mL, with a suggested maximum fluid deficit of 750 mL for elderly or fragile patients. Additionally, because the return electrode is off the surgical field in monopolar surgery, there is a risk of current diversion to the cervix, vagina, or vulva because the current travels between the active electrode on the surgical field to the return electrode on the patient’s thigh. The risk of current diversion is greater if there is damage to electrode insulation, loss of contact between the external sheath and the cervix, or direct coupling between the electrode and the surrounding tissue.

Advantages of the bipolar resectoscope

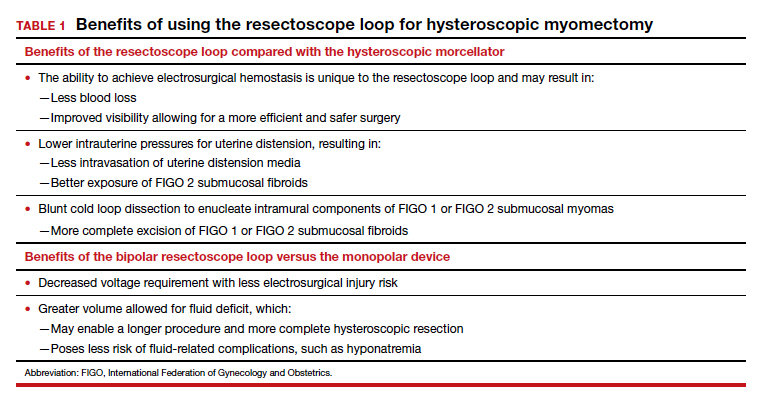

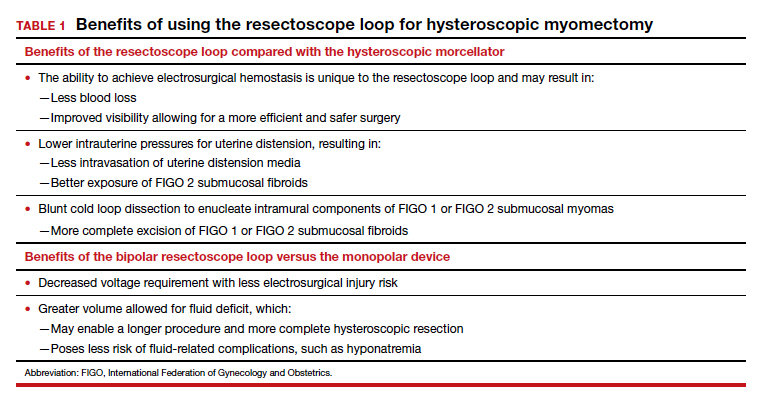

Because of the potential risks associated with the monopolar resectoscope, over the past 25 years the bipolar resectoscope emerged as an alternative due to its numerous benefits (TABLE 1).

Unlike monopolar resectoscopes, bipolar resectoscopes require an electrolyte-rich distension medium such as 0.9% normal saline or lactated Ringer’s. These isotonic distension media allow a much higher fluid deficit (2,500 mL for healthy patients, 1,500 mL for elderly patients or patients with comorbidities) as the isotonic solution is safer to use. Furthermore, it allows for lower voltage settings and decreased electrical spread compared to the monopolar resectoscope since the current stays between the 2 electrodes. Because isotonic media are miscible with blood, however, a potential drawback is that in cases with bleeding, visibility may be more limited compared to hypotonic distension media.

Evidence on fertility outcomes

Several studies have compared operative and fertility outcomes with the use of monopolar versus bipolar hysteroscopy.

In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing outcomes after hysteroscopy with a monopolar (glycine 1.5%) versus bipolar (0.9% normal saline) 26 French resectoscope loop, Berg and colleagues found that the only significant difference between the 2 groups was that the change in serum sodium pre and postoperatively was greater in the monopolar group despite having a smaller mean fluid deficit (765 mL vs 1,227 mL).1

Similarly, in a study of fertility outcomes after monopolar versus bipolar hysteroscopic myomectomy with use of a 26 French resectoscope Collins knife, Roy and colleagues found no significant differences in postoperative pregnancy rates or successful pregnancy outcomes, operative time, fluid deficit, or improvement in menstrual symptoms.2 However, the monopolar group had a much higher incidence of postoperative hyponatremia (30% vs 0%) that required additional days of hospitalization despite similar fluid deficits of between 600 and 700 mL.2

Similar findings were noted in another RCT that compared operative outcomes between monopolar and bipolar resectoscope usage during metroplasty for infertility, with a postoperative hyponatremia incidence of 17.1% in the monopolar group versus 0% in the bipolar group despite similar fluid deficits.3 Energy type had no effect on reproductive outcomes in either group.3

Continue to: How does the resectoscope compare with mechanical tissue removal systems?...

How does the resectoscope compare with mechanical tissue removal systems?

In 2005, the first hysteroscopic mechanical tissue removal system was introduced in the United States, providing an additional treatment method for such intrauterine masses as fibroids and polyps.

Advantages. Rather than using an electrical current, these tissue removal systems use a rotating blade with suction that is introduced through a specially designed rigid hysteroscopic sheath. As the instrument incises the pathology, the tissue is removed from the intrauterine cavity and collected in a specimen bag inside the fluid management system. This immediate removal of tissue allows for insertion of the device only once during initial entry, decreasing both the risk of perforation and operative times. Furthermore, mechanical tissue removal systems can be used with isotonic media, negating the risks associated with hypotonic media. Currently, the 2 mechanical tissue removal systems available in the United States are the TruClear and the MyoSure hysteroscopic tissue removal systems.

Studies comparing mechanical tissue removal of polyps and myomas with conventional resectoscope resection have found that mechanical tissue removal is associated with reduced operative time, fluid deficit, and number of instrument insertions.4-8 However, studies have found no significant difference in postoperative patient satisfaction.7,9

Additionally, hysteroscopic tissue removal systems have an easier learning curve. Van Dongen and colleagues conducted an RCT to compare resident-in-training comfort levels when learning to use both a mechanical tissue removal system and a traditional resectoscope; they found increased comfort with the hysteroscopic tissue removal system, suggesting greater ease of use.10

Drawbacks. Despite their many benefits, mechanical tissue removal systems have some disadvantages when compared with the resectoscope. First, mechanical tissue removal systems are associated with higher instrument costs. In addition, they have extremely limited ability to achieve hemostasis when encountering blood vessels during resection, resulting in poor visibility especially when resecting large myomas with feeding vessels.

Hysteroscopic mechanical tissue removal systems typically use higher intrauterine pressures for uterine distension compared with the resectoscope, especially when trying to improve visibility in a bloody surgical field. Increasing the intrauterine pressure with the distension media allows for compression of the blood vessels. As a result, however, submucosal fibroids classified as FIGO 2 (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) may be less visible since the higher intrauterine pressure can compress both blood vessels and submucosal fibroids

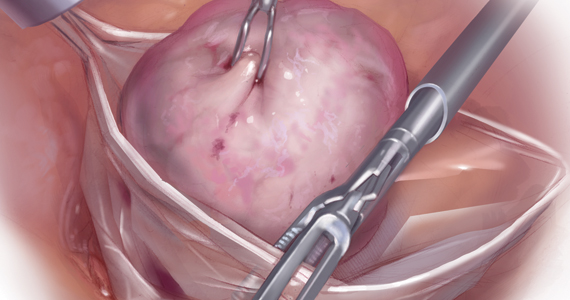

Additionally, mechanical tissue removal systems have limited ability to resect the intramural component of FIGO 1 or FIGO 2 submucosal fibroids since the intramural portion is embedded in the myometrium. Use of the resectoscope loop instead allows for a technique called the cold loop dissection, which uses the resectoscope loop to bluntly dissect and enucleate the intramural component of FIGO 1 and FIGO 2 submucosal myomas from the surrounding myometrium without activating the current. This blunt cold loop dissection technique allows for a deeper and more thorough resection. Often, if the pseudocapsule plane is identified, even the intramural component of FIGO 1 or FIGO 2 submucosal fibroids can be resected, enabling complete removal.

Lastly, mechanical tissue removal systems are not always faster than resectoscopes for all pathology. We prefer using the resectoscope for larger myomas (>3 cm) as the resectoscope allows for resection and removal of larger myoma chips, helping to decrease operative times. Given the many benefits of the resectoscope, we argue that the resectoscope loop remains a crucial instrument in operative gynecology and that learners should continue to hone their hysteroscopic skills with both the resectoscope and mechanical tissue removal systems.

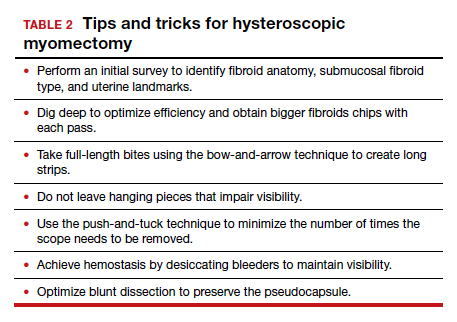

Tips and tricks for hysteroscopic myomectomy with the resectoscope loop

In the video below, "Bipolar resectoscope: Optimizing safe myomectomy," we review specific surgical techniques for optimizing outcomes and safety with the resectoscope loop. These include:

- bow-and-arrow technique

- identification of the fibroid anatomy (pseudocapsule plane)

- blunt cold loop dissection

- the push-and-tuck method

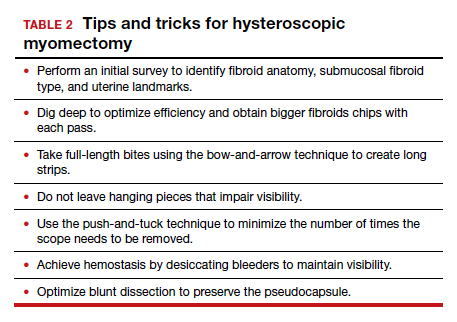

- efficient electrosurgical hemostasis (TABLE 2).

Although we use bipolar energy during this resection, the resection technique using the monopolar loop is the same.

The takeaway