User login

Asymptomatic Annular Plaques on the Neck

The Diagnosis: D-Penicillamine–Induced Elastosis Perforans Serpiginosa

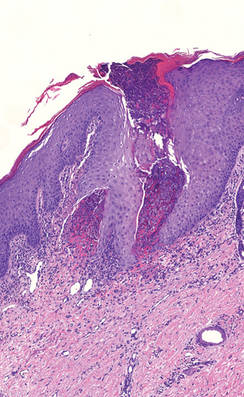

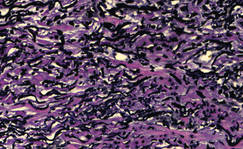

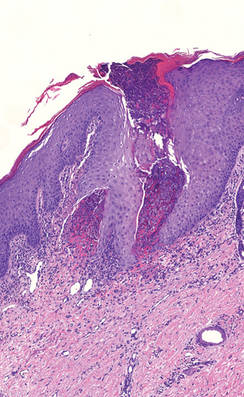

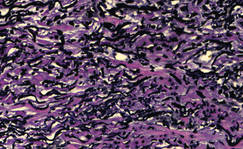

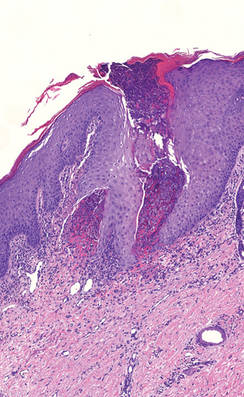

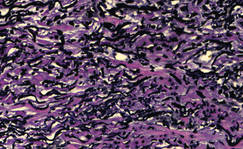

A 27-year-old woman was referred to our clinic by her rheumatologist with a 2×5-cm annular plaque on the right side of the lateral neck along with nummular plaques on the left side of 1 year’s duration (Figure 1). Her medical history was notable for systemic sclerosis that had been treated with oral D-penicillamine (750 mg daily) for the last 10 years. Histopathologic examination of the skin biopsy specimen revealed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (Figure 3), which confirmed the diagnosis of D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS).

|

Figure 1. Nummular plaques on the left side of the |

|

Figure 2. A punch biopsy specimen showed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (H&E, original magnification ×10). |

|

Figure 3. Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (original magnification ×40). |

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is a rare entity that may present in many different settings. Some associated genetic conditions include Down syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, acrogeria, osteogenesis imperfecta, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, and moya-moya disease. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa also may be inherited in rare cases in an autosomal-dominant pattern.1 There are solitary reports of EPS in the setting of renal disease, morphea, and systemic sclerosis. Most cases of EPS are iatrogenically acquired. As first reported in 1973, long-term D-penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease has been classically associated with the rare development of EPS.2 Putative mechanisms include copper chelation by D-penicillamine in the setting of altered copper homeostasis in Wilson disease and subsequent inhibition of elastic fiber cross-linking by copper-dependent lysyl oxidase. Another proposed mechanism is the direct inhibition of collagen cross-linking by D-penicillamine resulting in abnormal elastic fiber maturation.3 Outside of the context of Wilson disease, D-penicillamine–induced EPS also has developed during the treatment of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and cystinuria.4 Our patient withsystemic sclerosis also exemplifies the possibility of developing EPS from long-term D-penicillamine therapy even in the absence of coexisting Wilson disease.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa lesions classically present as asymptomatic, serpiginously arranged, hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, and annular plaques in young adults and children. Lesions usually present on the neck, though other locations have been described. Histologically, transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers, degenerated keratinocytes, and collagen is seen in the background of a foreign-body reaction with hematoxylin and eosin stain. Elastin stains show increased thickened elastic fibers in the dermis underlying the perforation. The histology of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is distinctive in that the elastic fibers are arranged in a bramble bush pattern with lateral buds.

The clinical course of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is variable, ranging from slow to no resolution after drug discontinuation, with residual scarring, atrophy, and concern for systemic elastosis. Adjunctive therapies include oral and topical retinoids, cryotherapy, imiquimod, and CO2 laser.5 For our patient, tazarotene gel 0.1% was recommended, but the patient became pregnant soon after the diagnosis was made. Despite being untreated, her lesions have remarkably improved during her pregnancy.

1. Langeveld-Wildschut EG, Toonstra J, van Vloten WA, et al. Familial elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:205-207.

2. Pass F, Goldfischer S, Sternlieb I, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa during penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:713-715.

3. Deguti MM, Mucenic M, Cancado EL, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa secondary to D-penicillamine treatment in a Wilson’s disease patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2153-2154.

4. Sahn EE, Maize JC, Garen PD, et al. D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa in a child with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:979-988.

5. Atzori L, Pinna AL, Pau M, et al. D-penicillamine elastosis perforans serpiginosa: description of two cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:3.

The Diagnosis: D-Penicillamine–Induced Elastosis Perforans Serpiginosa

A 27-year-old woman was referred to our clinic by her rheumatologist with a 2×5-cm annular plaque on the right side of the lateral neck along with nummular plaques on the left side of 1 year’s duration (Figure 1). Her medical history was notable for systemic sclerosis that had been treated with oral D-penicillamine (750 mg daily) for the last 10 years. Histopathologic examination of the skin biopsy specimen revealed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (Figure 3), which confirmed the diagnosis of D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS).

|

Figure 1. Nummular plaques on the left side of the |

|

Figure 2. A punch biopsy specimen showed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (H&E, original magnification ×10). |

|

Figure 3. Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (original magnification ×40). |

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is a rare entity that may present in many different settings. Some associated genetic conditions include Down syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, acrogeria, osteogenesis imperfecta, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, and moya-moya disease. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa also may be inherited in rare cases in an autosomal-dominant pattern.1 There are solitary reports of EPS in the setting of renal disease, morphea, and systemic sclerosis. Most cases of EPS are iatrogenically acquired. As first reported in 1973, long-term D-penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease has been classically associated with the rare development of EPS.2 Putative mechanisms include copper chelation by D-penicillamine in the setting of altered copper homeostasis in Wilson disease and subsequent inhibition of elastic fiber cross-linking by copper-dependent lysyl oxidase. Another proposed mechanism is the direct inhibition of collagen cross-linking by D-penicillamine resulting in abnormal elastic fiber maturation.3 Outside of the context of Wilson disease, D-penicillamine–induced EPS also has developed during the treatment of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and cystinuria.4 Our patient withsystemic sclerosis also exemplifies the possibility of developing EPS from long-term D-penicillamine therapy even in the absence of coexisting Wilson disease.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa lesions classically present as asymptomatic, serpiginously arranged, hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, and annular plaques in young adults and children. Lesions usually present on the neck, though other locations have been described. Histologically, transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers, degenerated keratinocytes, and collagen is seen in the background of a foreign-body reaction with hematoxylin and eosin stain. Elastin stains show increased thickened elastic fibers in the dermis underlying the perforation. The histology of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is distinctive in that the elastic fibers are arranged in a bramble bush pattern with lateral buds.

The clinical course of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is variable, ranging from slow to no resolution after drug discontinuation, with residual scarring, atrophy, and concern for systemic elastosis. Adjunctive therapies include oral and topical retinoids, cryotherapy, imiquimod, and CO2 laser.5 For our patient, tazarotene gel 0.1% was recommended, but the patient became pregnant soon after the diagnosis was made. Despite being untreated, her lesions have remarkably improved during her pregnancy.

The Diagnosis: D-Penicillamine–Induced Elastosis Perforans Serpiginosa

A 27-year-old woman was referred to our clinic by her rheumatologist with a 2×5-cm annular plaque on the right side of the lateral neck along with nummular plaques on the left side of 1 year’s duration (Figure 1). Her medical history was notable for systemic sclerosis that had been treated with oral D-penicillamine (750 mg daily) for the last 10 years. Histopathologic examination of the skin biopsy specimen revealed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (Figure 3), which confirmed the diagnosis of D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS).

|

Figure 1. Nummular plaques on the left side of the |

|

Figure 2. A punch biopsy specimen showed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (H&E, original magnification ×10). |

|

Figure 3. Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (original magnification ×40). |

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is a rare entity that may present in many different settings. Some associated genetic conditions include Down syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, acrogeria, osteogenesis imperfecta, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, and moya-moya disease. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa also may be inherited in rare cases in an autosomal-dominant pattern.1 There are solitary reports of EPS in the setting of renal disease, morphea, and systemic sclerosis. Most cases of EPS are iatrogenically acquired. As first reported in 1973, long-term D-penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease has been classically associated with the rare development of EPS.2 Putative mechanisms include copper chelation by D-penicillamine in the setting of altered copper homeostasis in Wilson disease and subsequent inhibition of elastic fiber cross-linking by copper-dependent lysyl oxidase. Another proposed mechanism is the direct inhibition of collagen cross-linking by D-penicillamine resulting in abnormal elastic fiber maturation.3 Outside of the context of Wilson disease, D-penicillamine–induced EPS also has developed during the treatment of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and cystinuria.4 Our patient withsystemic sclerosis also exemplifies the possibility of developing EPS from long-term D-penicillamine therapy even in the absence of coexisting Wilson disease.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa lesions classically present as asymptomatic, serpiginously arranged, hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, and annular plaques in young adults and children. Lesions usually present on the neck, though other locations have been described. Histologically, transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers, degenerated keratinocytes, and collagen is seen in the background of a foreign-body reaction with hematoxylin and eosin stain. Elastin stains show increased thickened elastic fibers in the dermis underlying the perforation. The histology of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is distinctive in that the elastic fibers are arranged in a bramble bush pattern with lateral buds.

The clinical course of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is variable, ranging from slow to no resolution after drug discontinuation, with residual scarring, atrophy, and concern for systemic elastosis. Adjunctive therapies include oral and topical retinoids, cryotherapy, imiquimod, and CO2 laser.5 For our patient, tazarotene gel 0.1% was recommended, but the patient became pregnant soon after the diagnosis was made. Despite being untreated, her lesions have remarkably improved during her pregnancy.

1. Langeveld-Wildschut EG, Toonstra J, van Vloten WA, et al. Familial elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:205-207.

2. Pass F, Goldfischer S, Sternlieb I, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa during penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:713-715.

3. Deguti MM, Mucenic M, Cancado EL, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa secondary to D-penicillamine treatment in a Wilson’s disease patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2153-2154.

4. Sahn EE, Maize JC, Garen PD, et al. D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa in a child with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:979-988.

5. Atzori L, Pinna AL, Pau M, et al. D-penicillamine elastosis perforans serpiginosa: description of two cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:3.

1. Langeveld-Wildschut EG, Toonstra J, van Vloten WA, et al. Familial elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:205-207.

2. Pass F, Goldfischer S, Sternlieb I, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa during penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:713-715.

3. Deguti MM, Mucenic M, Cancado EL, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa secondary to D-penicillamine treatment in a Wilson’s disease patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2153-2154.

4. Sahn EE, Maize JC, Garen PD, et al. D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa in a child with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:979-988.

5. Atzori L, Pinna AL, Pau M, et al. D-penicillamine elastosis perforans serpiginosa: description of two cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:3.