User login

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

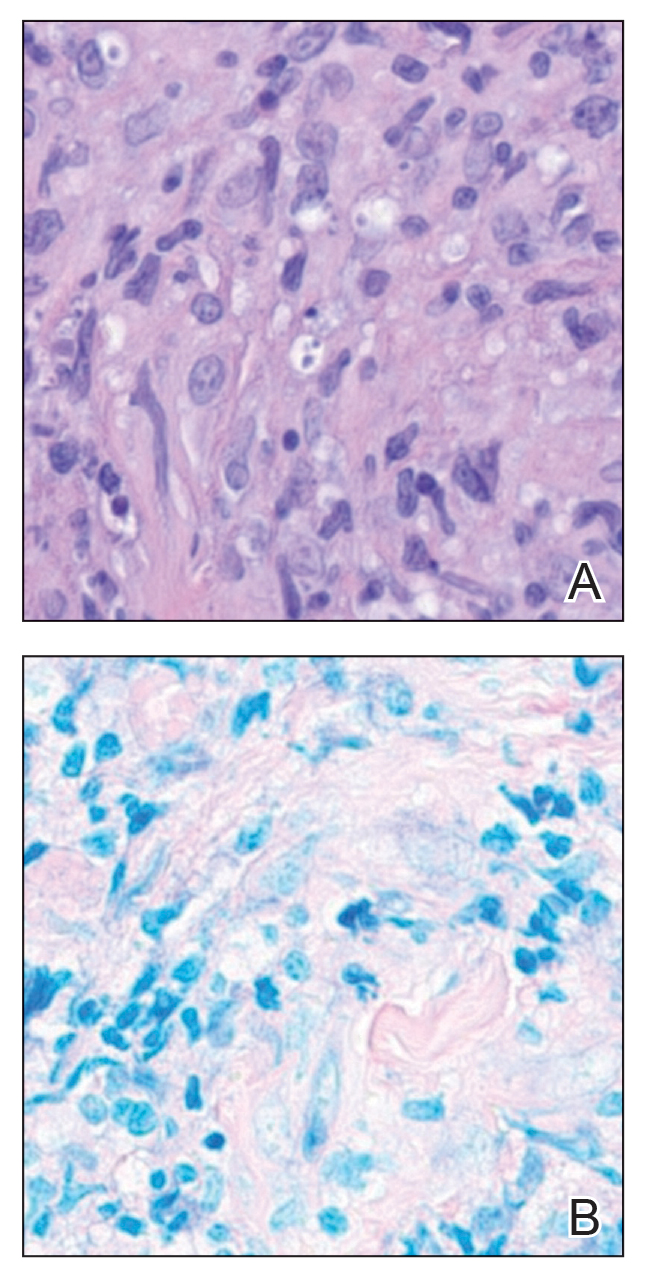

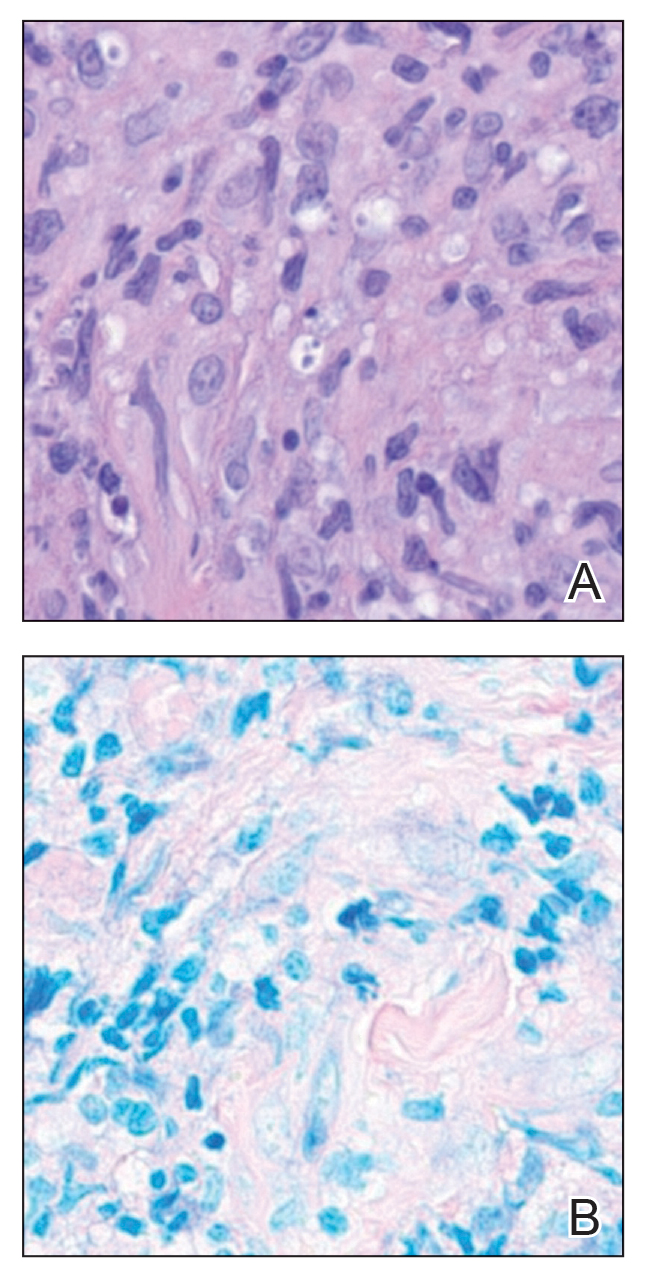

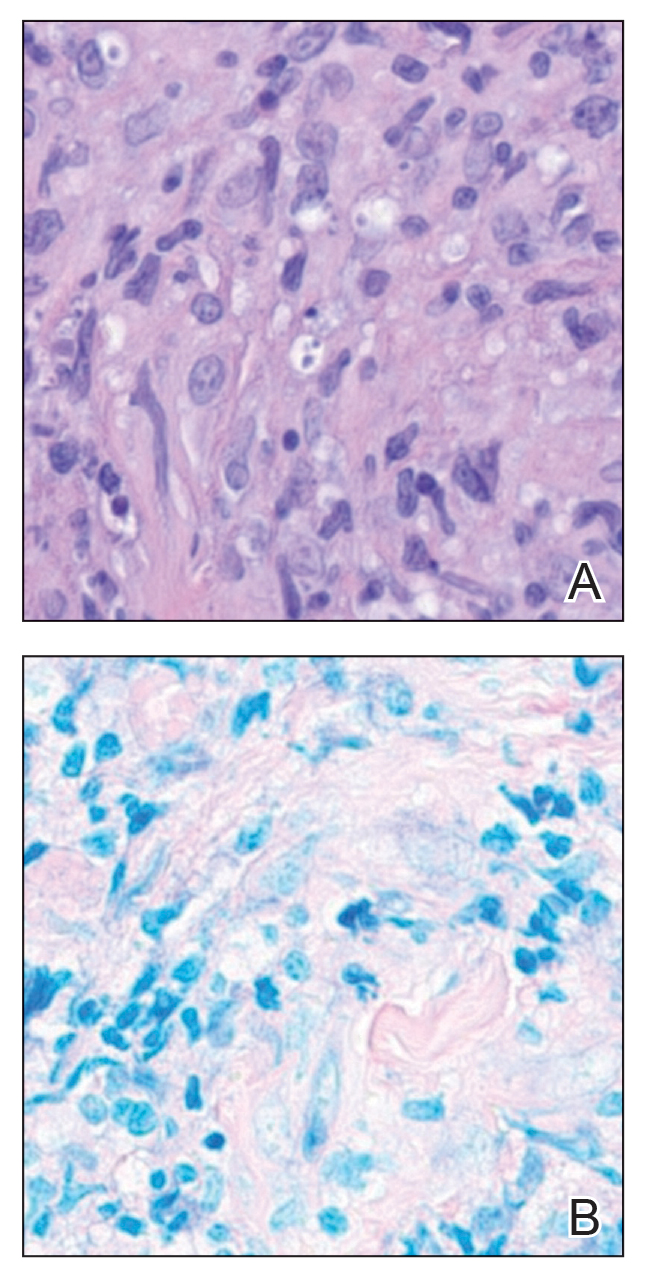

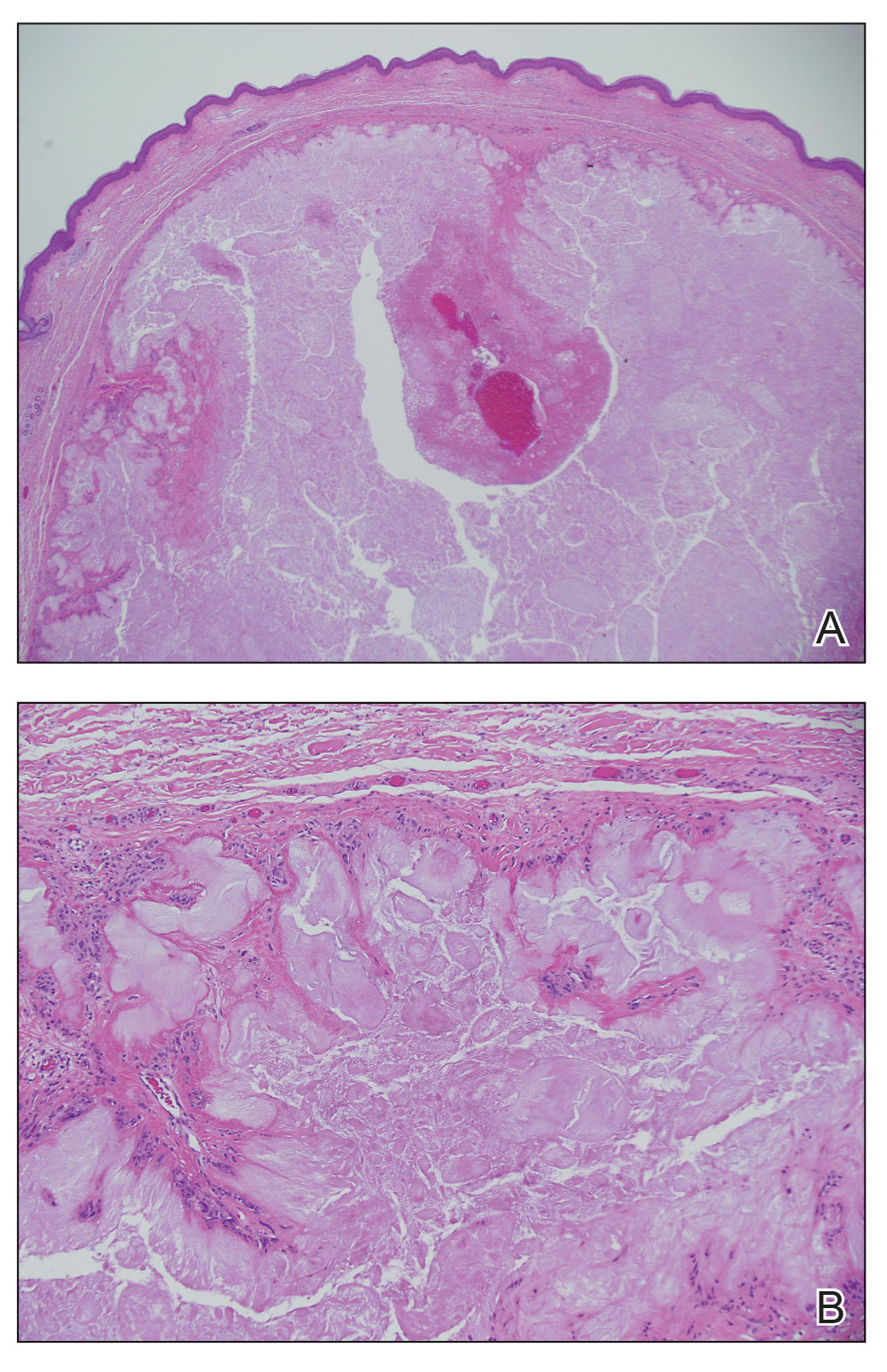

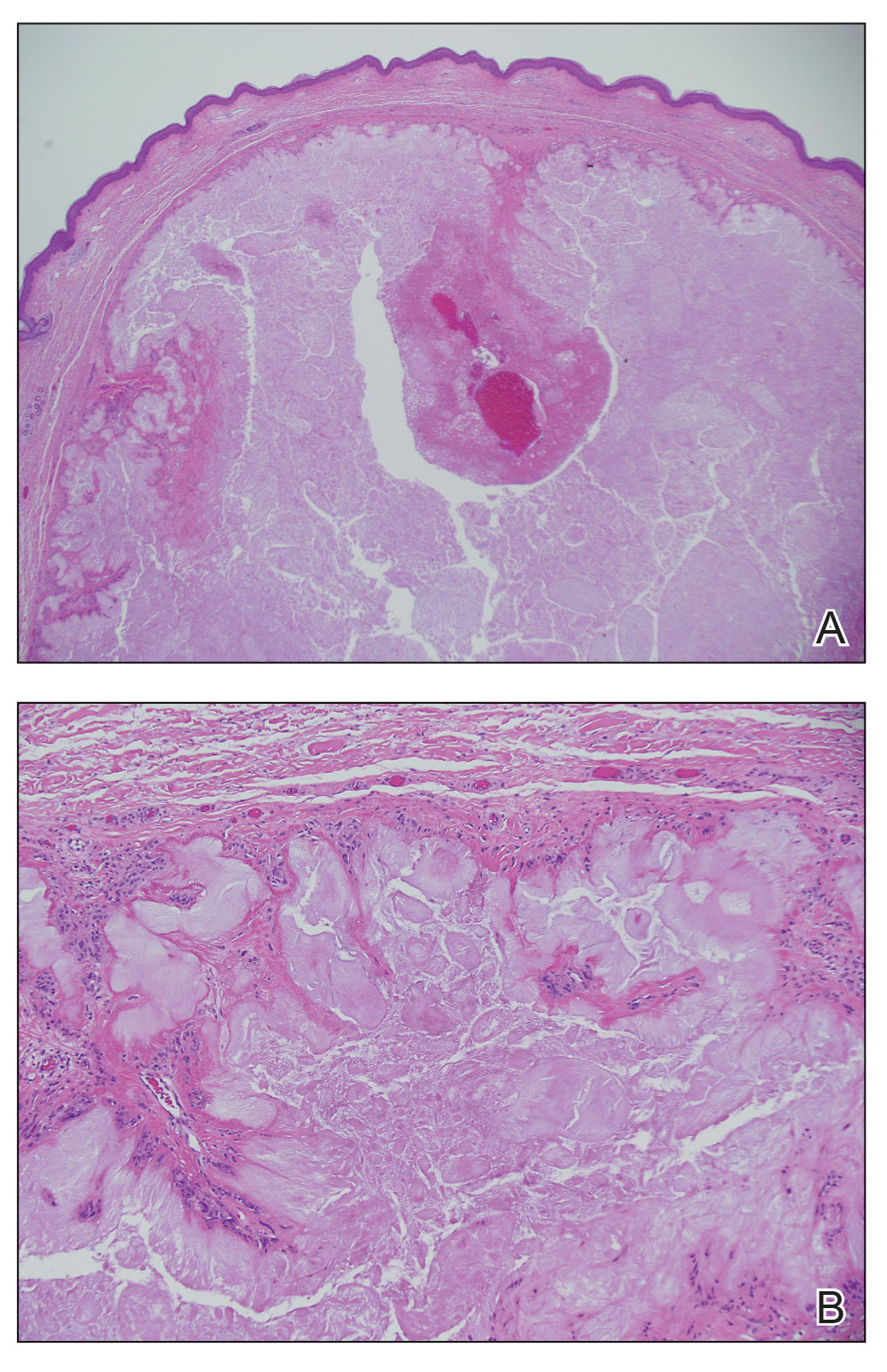

The biopsy results revealed amastigotes at the periphery of parasitized histiocytes, consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed Leishmania guyanensis species complex, which includes both L guyanensis and Leishmania panamensis. In this case of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis (Figure 1), our patient received a prolonged course of systemic therapy with oral miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. At the most recent follow-up appointment, she showed ongoing resolution of ulcerations, subcutaneous plaques, and lymphadenopathy on the trunk and face, but development of subcutaneous nodules continued on the arms and legs. At the next follow-up, physical examination revealed that the lesions slowly started to fade.

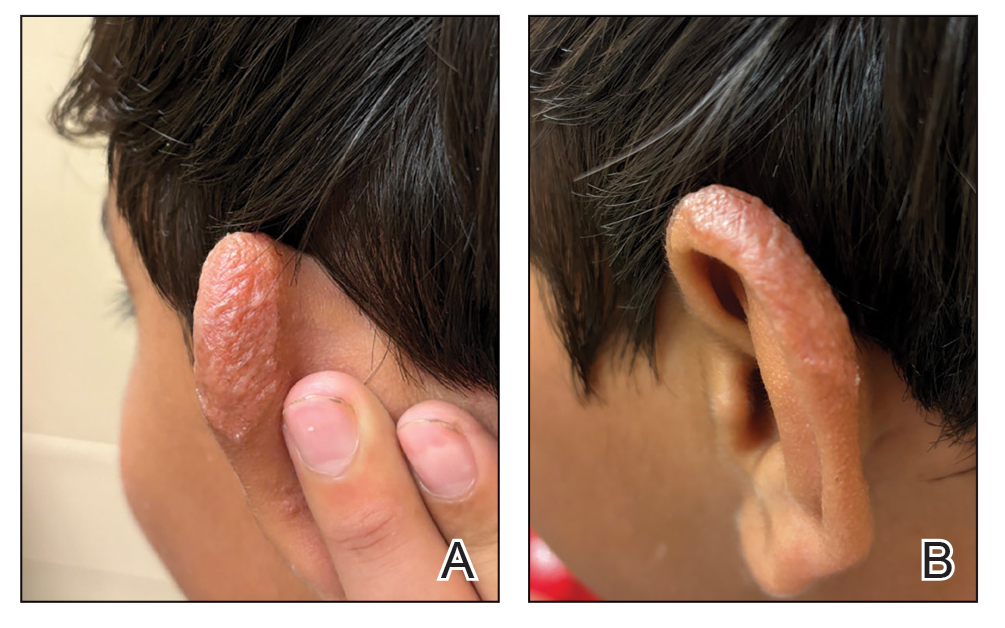

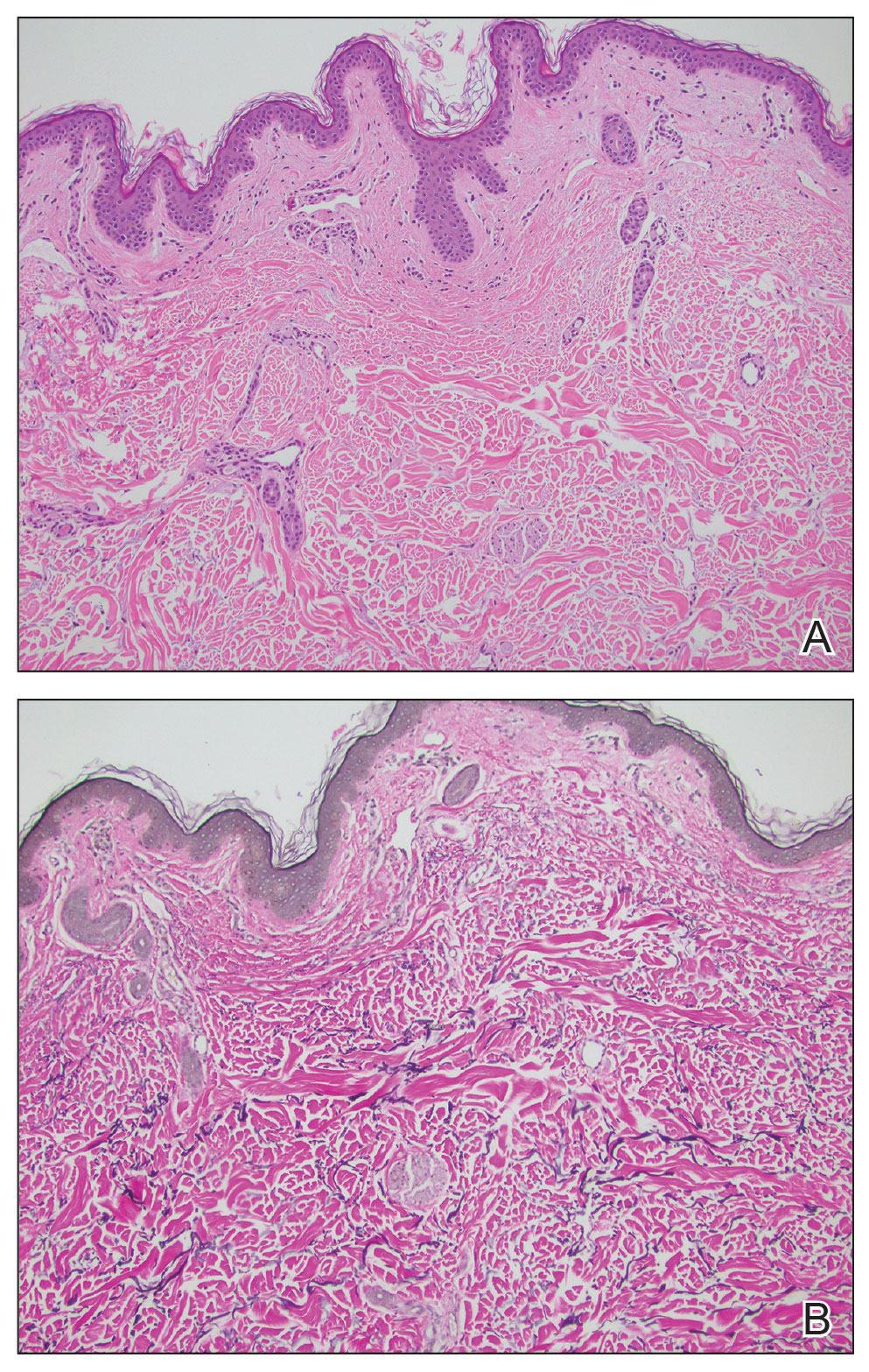

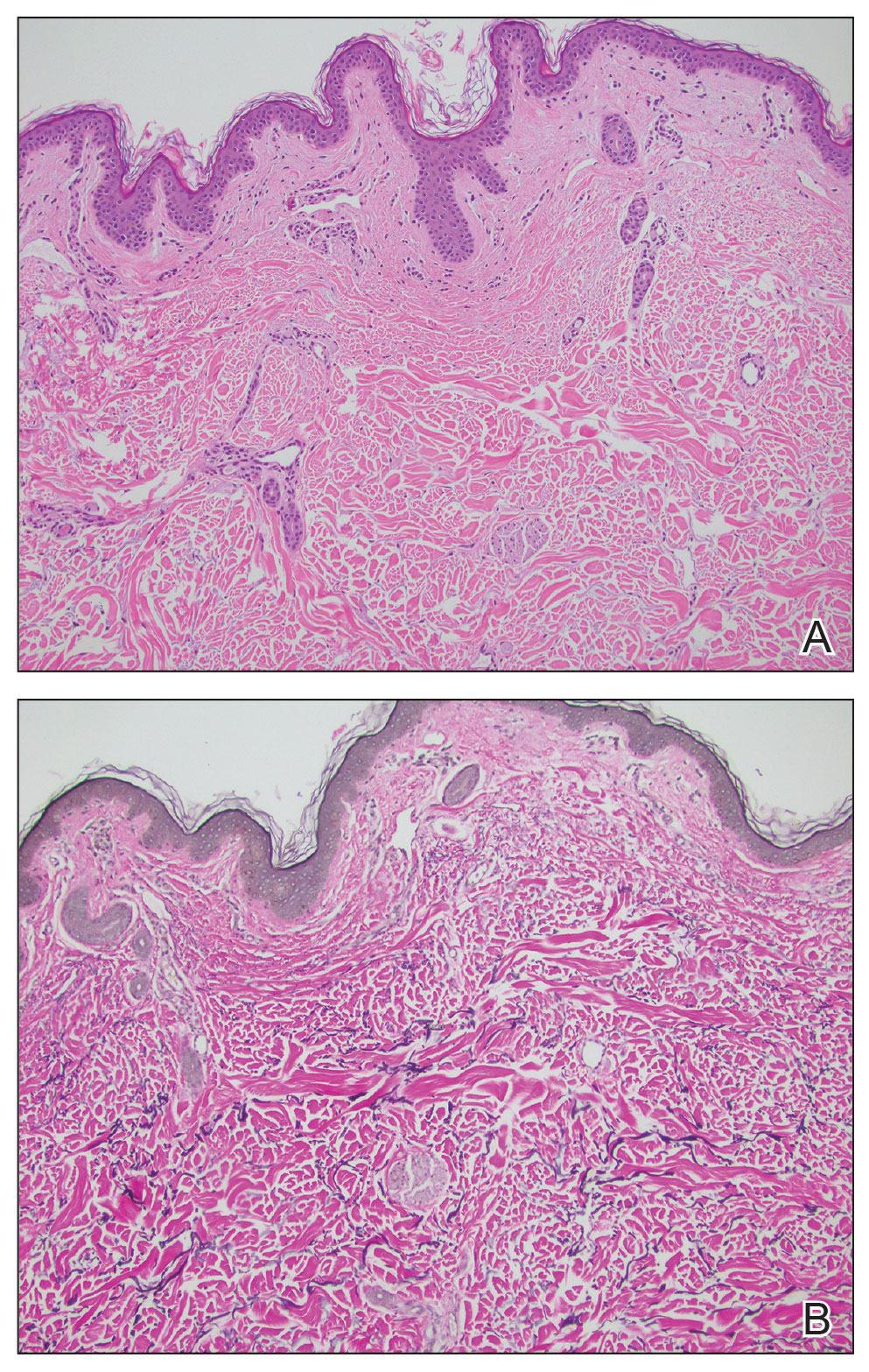

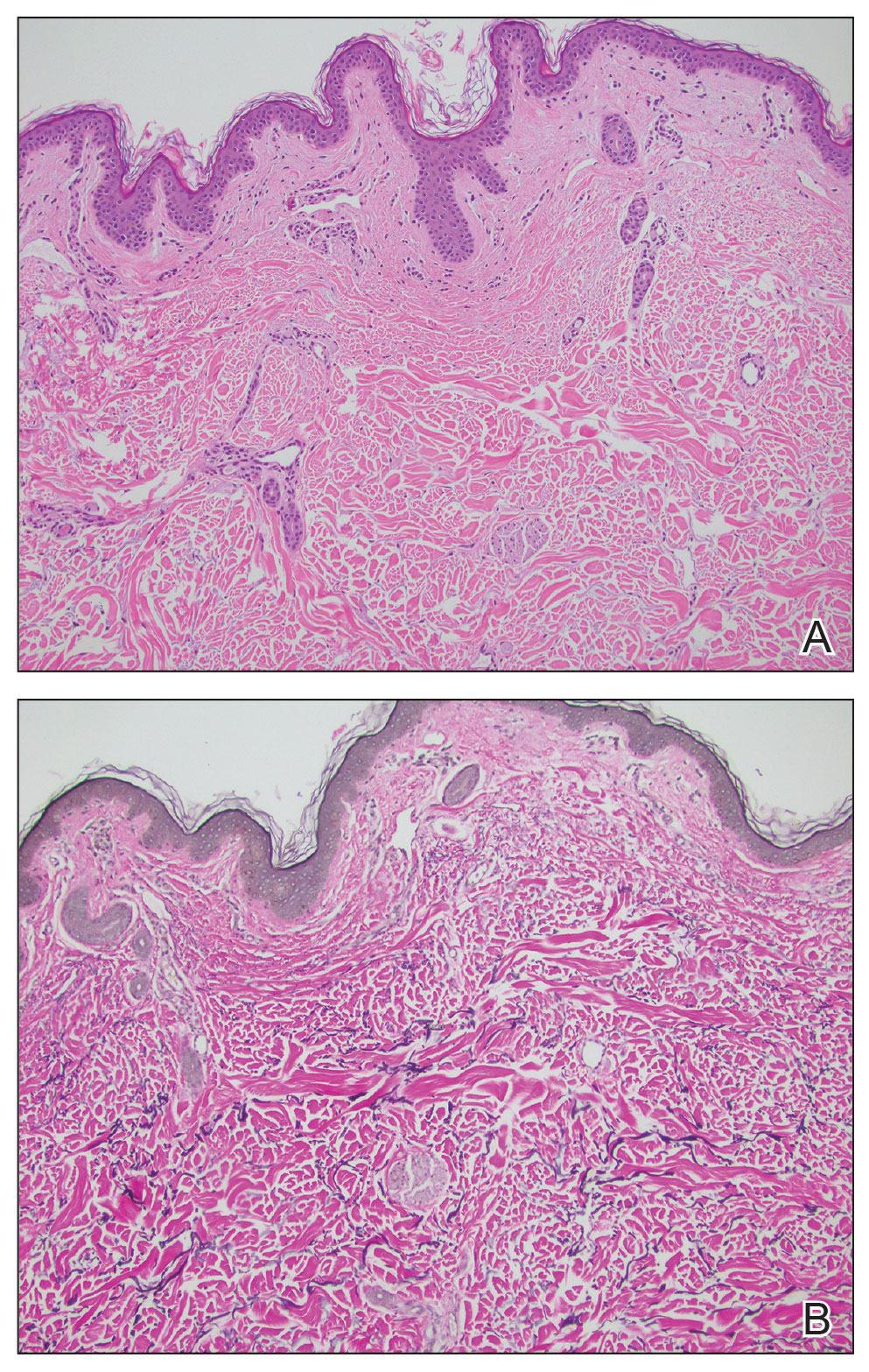

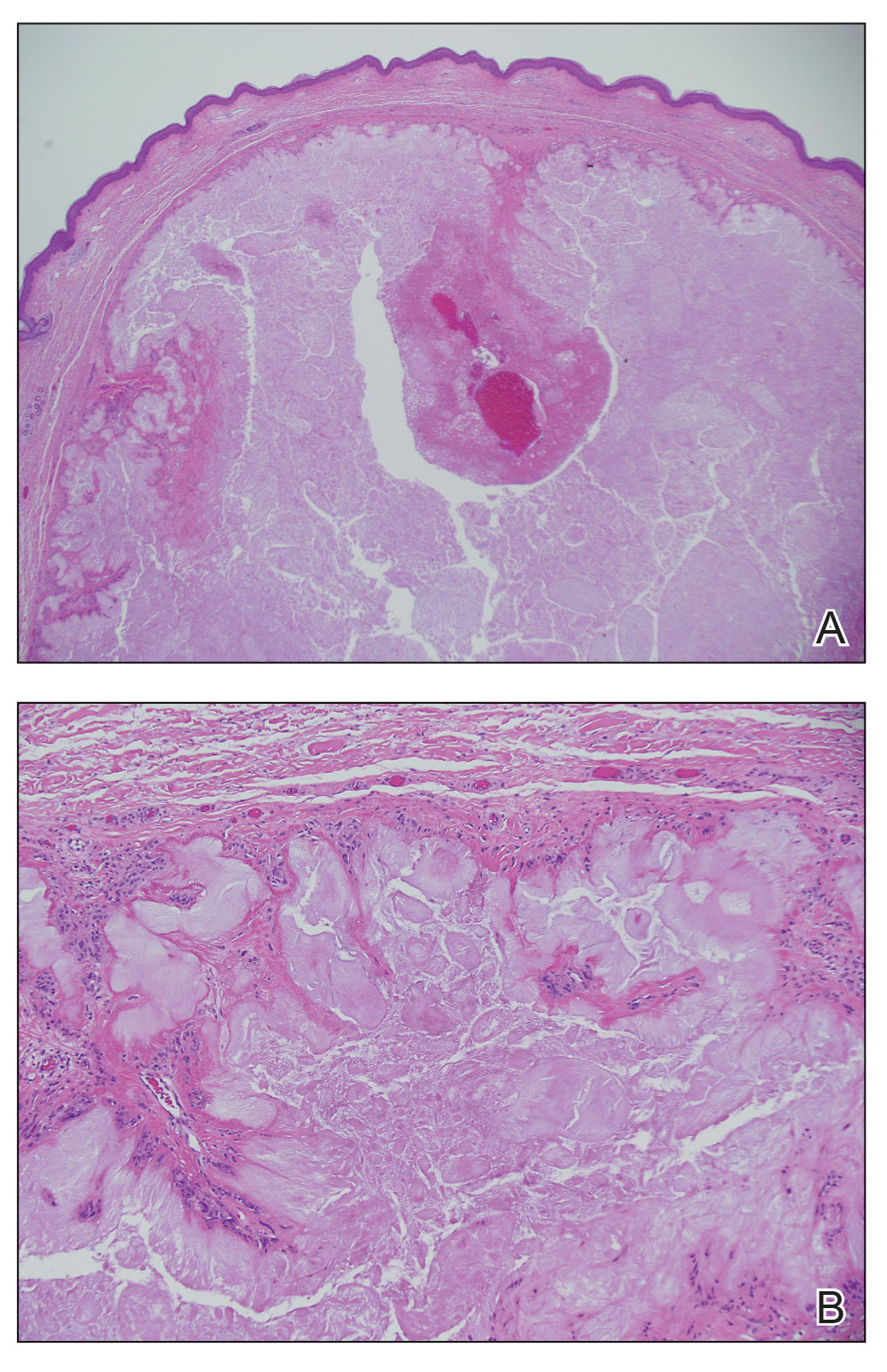

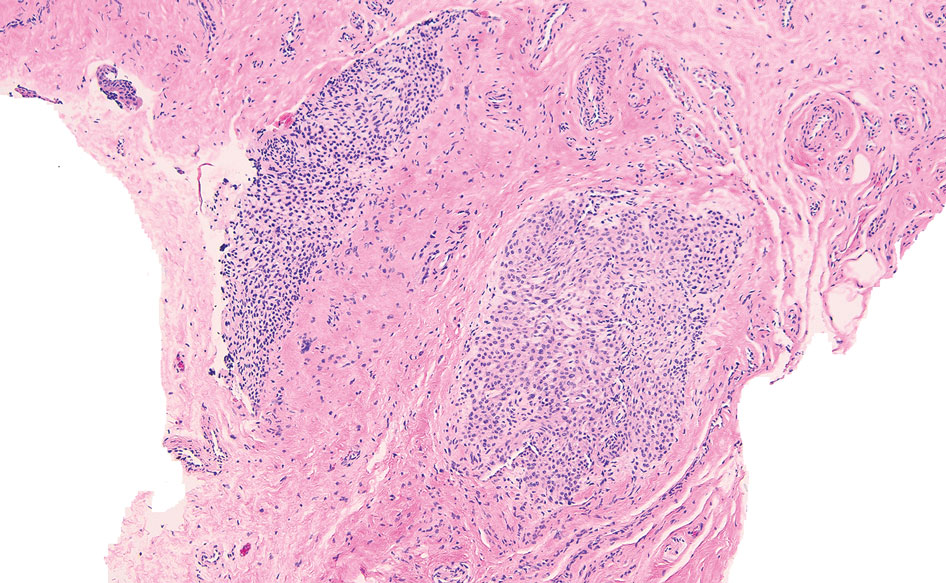

Leishmania species are parasites transmitted by bites of female sand flies, which belong to the genera Phlebotomus (Old World, Eastern Hemisphere) and Lutzomyia (New World, Western Hemisphere) genera.1 Leishmania species have a complex life cycle, propagating within human macrophages, ultimately leading to cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease manifestations.2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis manifests classically as scattered, painless, slow-healing ulcers.3 A biopsy taken from the edge of a cutaneous ulcer for hematoxylin and eosin processing is recommended for initial diagnosis, and subsequent polymerase chain reaction of the sample is required for speciation, which guides therapeutic options.4,5 Classic hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stain findings include amastigotes lining the edges of parasitized histiocytes (Figure 2).

Systemic treatment options include sodium stibogluconate, amphotericin B, pentamidine, paromomycin, miltefosine, and azole antifungals.2,5 Geography often plays a critical role in selecting treatment options due to resistance rates of individual Leishmania species; for example, paromomycin compounds are more effective for cutaneous disease caused by Leishmania major than Leishmania tropica. Miltefosine is not effective for treating Leishmania braziliensis which can be acquired outside Guatemala, and higher doses of amphotericin B are recommended for visceral disease from East Africa.2,5 In patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L guyanensis, miltefosine remains a first-line option due to its oral formulation and long half-life within organisms, though there is a risk for teratogenicity.2 Amphotericin B remains the most effective treatment for visceral leishmaniasis and can be used off label to treat mucocutaneous disease or when cutaneous disease is refractory to other treatment options.3

Given the potential of L guyanensis to progress to mucocutaneous disease, monitoring for mucosal involvement should be performed at regular intervals for 6 months to 1 year.2 Treatment may be considered efficacious if no new skin lesions occur after 4 to 6 weeks of therapy; existing skin lesions should be re-epithelializing and reduced by 50% in size, with most cutaneous disease adequately controlled after 3 months of therapy.2

- Olivier M, Minguez-Menendez A, Fernandez-Prada C. Leishmania viannia guyanensis. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:1018-1019. doi:10.1016 /j.pt.2019.06.008

- Singh R, Kashif M, Srivastava P, et al. Recent advances in chemotherapeutics for leishmaniasis: importance of the cellular biochemistry of the parasite and its molecular interaction with the host. Pathogens. 2023;12:706. doi:10.3390/pathogens12050706

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63: 1539-1557. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw742

- Specimen Collection Guide for Laboratory Diagnosis of Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticprocedures /other/leish.html

- Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: updates in diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:101-117. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.004

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results revealed amastigotes at the periphery of parasitized histiocytes, consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed Leishmania guyanensis species complex, which includes both L guyanensis and Leishmania panamensis. In this case of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis (Figure 1), our patient received a prolonged course of systemic therapy with oral miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. At the most recent follow-up appointment, she showed ongoing resolution of ulcerations, subcutaneous plaques, and lymphadenopathy on the trunk and face, but development of subcutaneous nodules continued on the arms and legs. At the next follow-up, physical examination revealed that the lesions slowly started to fade.

Leishmania species are parasites transmitted by bites of female sand flies, which belong to the genera Phlebotomus (Old World, Eastern Hemisphere) and Lutzomyia (New World, Western Hemisphere) genera.1 Leishmania species have a complex life cycle, propagating within human macrophages, ultimately leading to cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease manifestations.2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis manifests classically as scattered, painless, slow-healing ulcers.3 A biopsy taken from the edge of a cutaneous ulcer for hematoxylin and eosin processing is recommended for initial diagnosis, and subsequent polymerase chain reaction of the sample is required for speciation, which guides therapeutic options.4,5 Classic hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stain findings include amastigotes lining the edges of parasitized histiocytes (Figure 2).

Systemic treatment options include sodium stibogluconate, amphotericin B, pentamidine, paromomycin, miltefosine, and azole antifungals.2,5 Geography often plays a critical role in selecting treatment options due to resistance rates of individual Leishmania species; for example, paromomycin compounds are more effective for cutaneous disease caused by Leishmania major than Leishmania tropica. Miltefosine is not effective for treating Leishmania braziliensis which can be acquired outside Guatemala, and higher doses of amphotericin B are recommended for visceral disease from East Africa.2,5 In patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L guyanensis, miltefosine remains a first-line option due to its oral formulation and long half-life within organisms, though there is a risk for teratogenicity.2 Amphotericin B remains the most effective treatment for visceral leishmaniasis and can be used off label to treat mucocutaneous disease or when cutaneous disease is refractory to other treatment options.3

Given the potential of L guyanensis to progress to mucocutaneous disease, monitoring for mucosal involvement should be performed at regular intervals for 6 months to 1 year.2 Treatment may be considered efficacious if no new skin lesions occur after 4 to 6 weeks of therapy; existing skin lesions should be re-epithelializing and reduced by 50% in size, with most cutaneous disease adequately controlled after 3 months of therapy.2

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results revealed amastigotes at the periphery of parasitized histiocytes, consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed Leishmania guyanensis species complex, which includes both L guyanensis and Leishmania panamensis. In this case of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis (Figure 1), our patient received a prolonged course of systemic therapy with oral miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. At the most recent follow-up appointment, she showed ongoing resolution of ulcerations, subcutaneous plaques, and lymphadenopathy on the trunk and face, but development of subcutaneous nodules continued on the arms and legs. At the next follow-up, physical examination revealed that the lesions slowly started to fade.

Leishmania species are parasites transmitted by bites of female sand flies, which belong to the genera Phlebotomus (Old World, Eastern Hemisphere) and Lutzomyia (New World, Western Hemisphere) genera.1 Leishmania species have a complex life cycle, propagating within human macrophages, ultimately leading to cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease manifestations.2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis manifests classically as scattered, painless, slow-healing ulcers.3 A biopsy taken from the edge of a cutaneous ulcer for hematoxylin and eosin processing is recommended for initial diagnosis, and subsequent polymerase chain reaction of the sample is required for speciation, which guides therapeutic options.4,5 Classic hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stain findings include amastigotes lining the edges of parasitized histiocytes (Figure 2).

Systemic treatment options include sodium stibogluconate, amphotericin B, pentamidine, paromomycin, miltefosine, and azole antifungals.2,5 Geography often plays a critical role in selecting treatment options due to resistance rates of individual Leishmania species; for example, paromomycin compounds are more effective for cutaneous disease caused by Leishmania major than Leishmania tropica. Miltefosine is not effective for treating Leishmania braziliensis which can be acquired outside Guatemala, and higher doses of amphotericin B are recommended for visceral disease from East Africa.2,5 In patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L guyanensis, miltefosine remains a first-line option due to its oral formulation and long half-life within organisms, though there is a risk for teratogenicity.2 Amphotericin B remains the most effective treatment for visceral leishmaniasis and can be used off label to treat mucocutaneous disease or when cutaneous disease is refractory to other treatment options.3

Given the potential of L guyanensis to progress to mucocutaneous disease, monitoring for mucosal involvement should be performed at regular intervals for 6 months to 1 year.2 Treatment may be considered efficacious if no new skin lesions occur after 4 to 6 weeks of therapy; existing skin lesions should be re-epithelializing and reduced by 50% in size, with most cutaneous disease adequately controlled after 3 months of therapy.2

- Olivier M, Minguez-Menendez A, Fernandez-Prada C. Leishmania viannia guyanensis. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:1018-1019. doi:10.1016 /j.pt.2019.06.008

- Singh R, Kashif M, Srivastava P, et al. Recent advances in chemotherapeutics for leishmaniasis: importance of the cellular biochemistry of the parasite and its molecular interaction with the host. Pathogens. 2023;12:706. doi:10.3390/pathogens12050706

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63: 1539-1557. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw742

- Specimen Collection Guide for Laboratory Diagnosis of Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticprocedures /other/leish.html

- Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: updates in diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:101-117. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.004

- Olivier M, Minguez-Menendez A, Fernandez-Prada C. Leishmania viannia guyanensis. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:1018-1019. doi:10.1016 /j.pt.2019.06.008

- Singh R, Kashif M, Srivastava P, et al. Recent advances in chemotherapeutics for leishmaniasis: importance of the cellular biochemistry of the parasite and its molecular interaction with the host. Pathogens. 2023;12:706. doi:10.3390/pathogens12050706

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63: 1539-1557. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw742

- Specimen Collection Guide for Laboratory Diagnosis of Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticprocedures /other/leish.html

- Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: updates in diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:101-117. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.004

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

A 43-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with widespread scaly plaques and ulcerations of 2 months’ duration. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable. The patient reported that the eruption began after returning from a vacation to Costa Rica, during which she spent time on the beach and white-water rafting. She noted that she had been exposed to numerous insects during her trip, and that her roommate, who had accompanied her, had similar exposure history and lesions. The plaques were refractory to multiple oral antibiotics previously prescribed by primary care. Physical examination revealed submental lymphadenopathy and painless ulcerations with indurated borders without purulent drainage alongside scattered scaly papules and plaques on the face, neck, arms, and legs. A biopsy was taken from an ulceration edge on the left thigh.

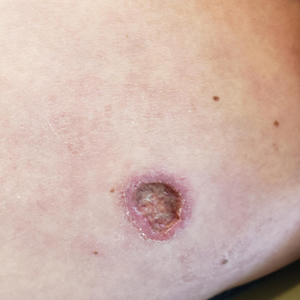

Crusted Lesion at the Implantation Site of a Pacemaker

Crusted Lesion at the Implantation Site of a Pacemaker

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pacemaker Extrusion

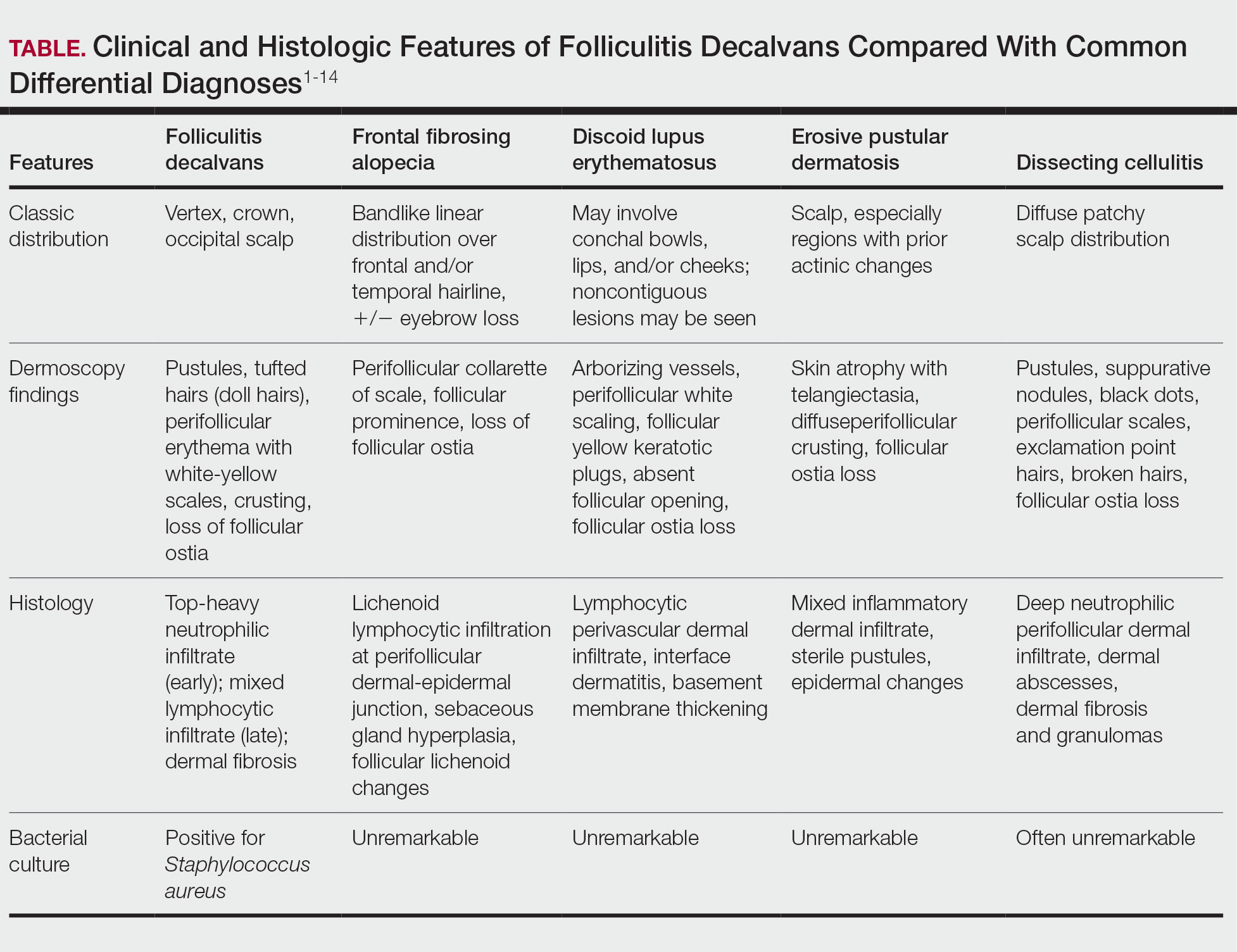

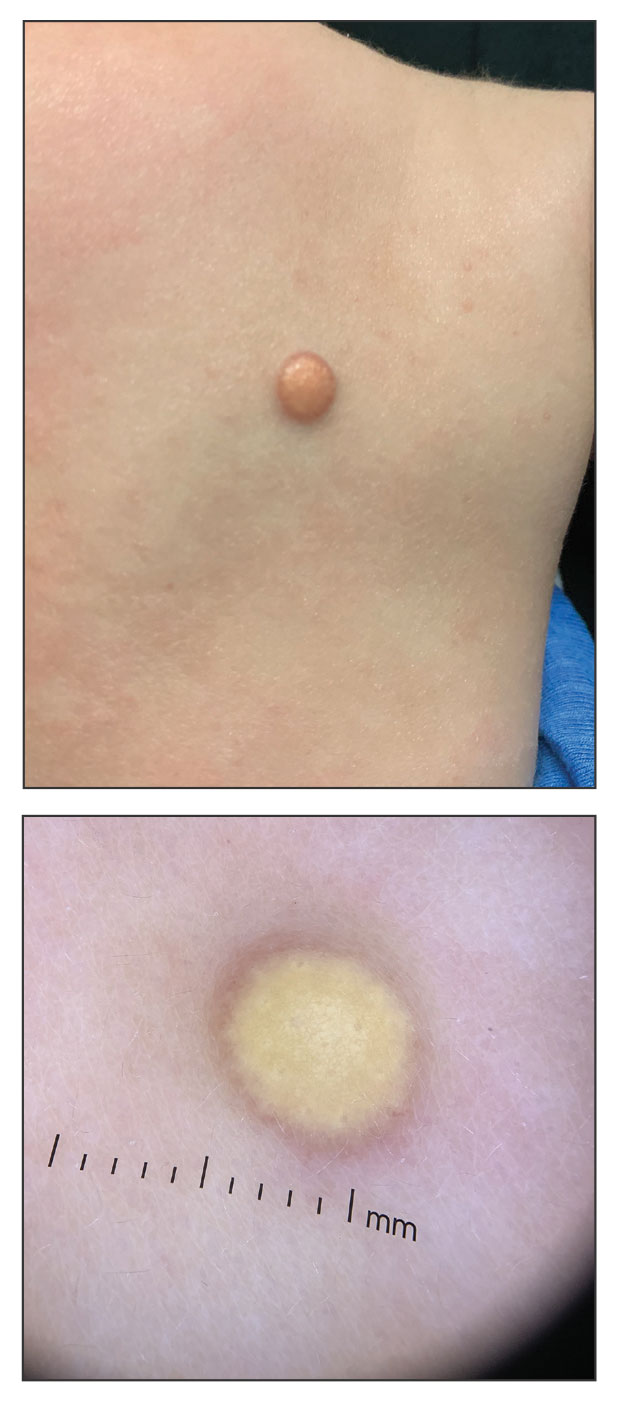

The lesion crust was easily scraped away to reveal extrusion of the permanent pacemaker (PPM) through the skin with a visible overlying gelatinous biofilm (Figure). The patient subsequently completed a 2-week course of clindamycin 300 mg 3 times daily followed by generator and lead removal, with reimplantation of the PPM into the right chest, as is the standard of care in the treatment of pacemaker extrusion.1

Ours is the first known reported case of pacemaker extrusion referred to dermatology with a primary concern for cutaneous malignancy. Pacemaker extrusion through the skin is not common, but it is the most common complication of PPM implantation, followed by infection.1 Pacemaker extrusion results from pressure necrosis and occurs when the PPM emerges through erythematous skin.1,2 Pacemaker extrusions generally are diagnosed by cardiology; however, it is important for dermatologists to recognize this phenomenon and differentiate it from other cutaneous pathologies, as the morphology of skin changes related to pacemaker extrusion through the skin can mimic cutaneous malignancy or other primary skin disease, especially if the outer layer of a biofilm that forms around the PPM hardens to form a crust. Our case emphasizes the importance of removing crusts when evaluating lesions.3

- Harcombe AA, Newell SA, Ludman PF, et al. Late complications following permanent pacemaker implantation or elective unit replacement. Heart. 1998;80:240-244. doi:10.1136/hrt.80.3.240

- Sanderson A, Hahn B. Pacemaker extrusion. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62:648. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.04.022

- Andrade AC, Hayashida MZ, Enokihara MMSES, et al. Dermoscopy of crusted lesion: diagnostic challenge and choice of technique for the analysis. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:387-388. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.06.016

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pacemaker Extrusion

The lesion crust was easily scraped away to reveal extrusion of the permanent pacemaker (PPM) through the skin with a visible overlying gelatinous biofilm (Figure). The patient subsequently completed a 2-week course of clindamycin 300 mg 3 times daily followed by generator and lead removal, with reimplantation of the PPM into the right chest, as is the standard of care in the treatment of pacemaker extrusion.1

Ours is the first known reported case of pacemaker extrusion referred to dermatology with a primary concern for cutaneous malignancy. Pacemaker extrusion through the skin is not common, but it is the most common complication of PPM implantation, followed by infection.1 Pacemaker extrusion results from pressure necrosis and occurs when the PPM emerges through erythematous skin.1,2 Pacemaker extrusions generally are diagnosed by cardiology; however, it is important for dermatologists to recognize this phenomenon and differentiate it from other cutaneous pathologies, as the morphology of skin changes related to pacemaker extrusion through the skin can mimic cutaneous malignancy or other primary skin disease, especially if the outer layer of a biofilm that forms around the PPM hardens to form a crust. Our case emphasizes the importance of removing crusts when evaluating lesions.3

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pacemaker Extrusion

The lesion crust was easily scraped away to reveal extrusion of the permanent pacemaker (PPM) through the skin with a visible overlying gelatinous biofilm (Figure). The patient subsequently completed a 2-week course of clindamycin 300 mg 3 times daily followed by generator and lead removal, with reimplantation of the PPM into the right chest, as is the standard of care in the treatment of pacemaker extrusion.1

Ours is the first known reported case of pacemaker extrusion referred to dermatology with a primary concern for cutaneous malignancy. Pacemaker extrusion through the skin is not common, but it is the most common complication of PPM implantation, followed by infection.1 Pacemaker extrusion results from pressure necrosis and occurs when the PPM emerges through erythematous skin.1,2 Pacemaker extrusions generally are diagnosed by cardiology; however, it is important for dermatologists to recognize this phenomenon and differentiate it from other cutaneous pathologies, as the morphology of skin changes related to pacemaker extrusion through the skin can mimic cutaneous malignancy or other primary skin disease, especially if the outer layer of a biofilm that forms around the PPM hardens to form a crust. Our case emphasizes the importance of removing crusts when evaluating lesions.3

- Harcombe AA, Newell SA, Ludman PF, et al. Late complications following permanent pacemaker implantation or elective unit replacement. Heart. 1998;80:240-244. doi:10.1136/hrt.80.3.240

- Sanderson A, Hahn B. Pacemaker extrusion. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62:648. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.04.022

- Andrade AC, Hayashida MZ, Enokihara MMSES, et al. Dermoscopy of crusted lesion: diagnostic challenge and choice of technique for the analysis. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:387-388. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.06.016

- Harcombe AA, Newell SA, Ludman PF, et al. Late complications following permanent pacemaker implantation or elective unit replacement. Heart. 1998;80:240-244. doi:10.1136/hrt.80.3.240

- Sanderson A, Hahn B. Pacemaker extrusion. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62:648. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.04.022

- Andrade AC, Hayashida MZ, Enokihara MMSES, et al. Dermoscopy of crusted lesion: diagnostic challenge and choice of technique for the analysis. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:387-388. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.06.016

Crusted Lesion at the Implantation Site of a Pacemaker

Crusted Lesion at the Implantation Site of a Pacemaker

A 78-year-old woman was referred to dermatology from the cardiology clinic with concerns of a nonhealing, scablike lesion on the left chest over the implantation site of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker (PPM). Eight months prior, the patient underwent successful PPM implantation for symptomatic bradycardia and second-degree atrioventricular block. Her cardiologists subsequently noticed an oozing crusting scab at the site of implantation and eventually referred her to dermatology with concerns for squamous cell carcinoma. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed an exophytic serous crust overlying the PPM implantation site on the left chest.

Nonhealing Lesion on the Ear in a Child

Nonhealing Lesion on the Ear in a Child

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

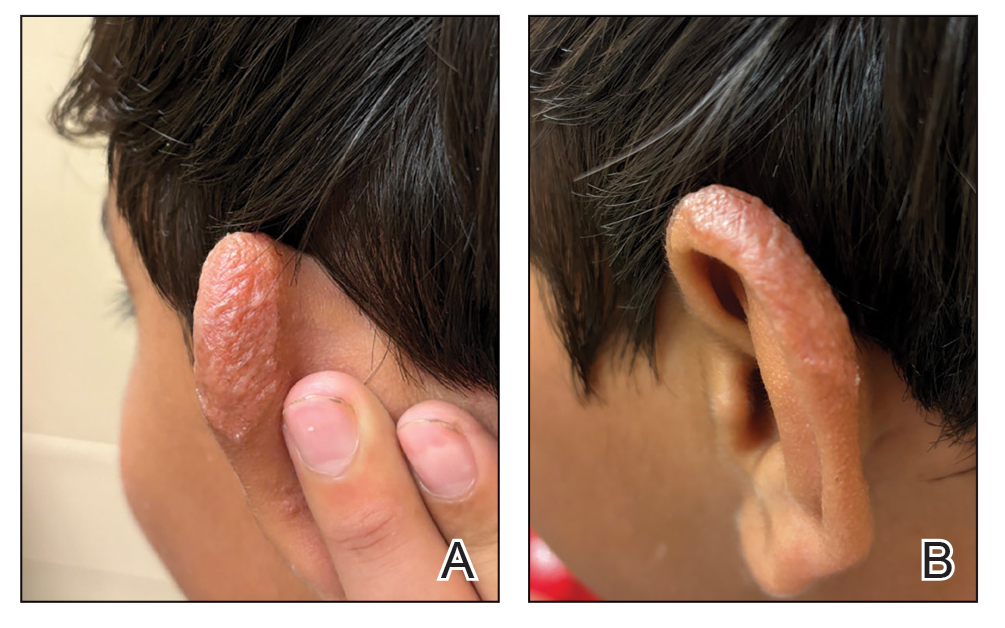

The biopsy results demonstrated a nonspecific chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, including few multinucleated histiocytes, a surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate, mostly mature lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and fragmented neutrophils. A special stain panel was negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff for fungi. Bacterial cultures from biopsy tissue grew normal skin flora, and both fungal and AFB cultures were negative. A second punch biopsy was recommended by infectious disease due to clinical suspicion of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Histopathology showed nonnecrotizing granulomas with dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and negative Giemsa staining for Leishmania amastigotes; however, it was concluded by pathology that the reason for the negative Leishmania staining was the late stage of the disease, indicated by the presence of granulomas, which can make visualization of organisms difficult. Nonetheless, universal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was positive for Leishmania tropica. Thus, although microscopic analysis was negative for visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, molecular analysis via PCR ultimately demonstrated a positive result and confirmed the diagnosis of CL (Figure 1). The variance in diagnostic accuracy exemplified in our case reinforces the need for multimodal diagnosis.

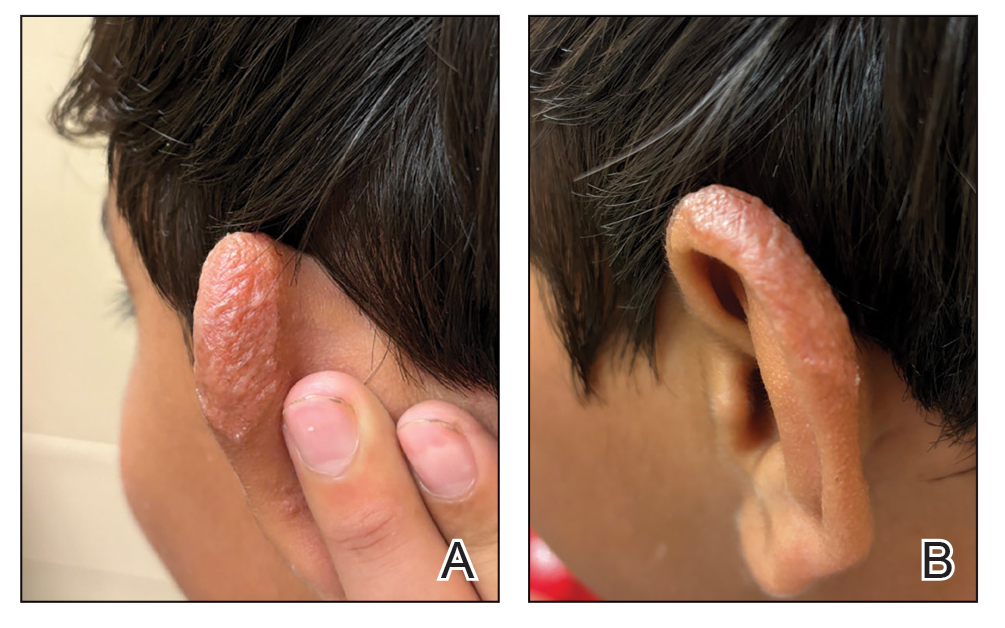

Multiple factors needed to be considered with regard to treatment in our patient, including but not limited to the location of the lesion on a slow-healing cartilaginous surface and the patient’s age. Considering the recalcitrant nature of the lesion and the L tropica strain exhibiting resistance to topical treatments, systemic therapies were the only option. Furthermore, parenteral routes of administration were confounded by the patient’s age, decreasing the likelihood of compliance with therapy. With these variables in mind and recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the best treatment for our patient was deemed to be a 28-day course of oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily. Compared to the initial presentation, a 1-month follow-up visit after completing the 28-day course of treatment demonstrated flattening of the lesion (Figure 2).

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by a protozoan parasite of the Leishmania genus, spread via inoculation from the bite of sandfly vectors.1 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common clinical manifestation of leishmaniasis. Other clinical manifestations include mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis.1,2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis typically manifests as open wounds on areas of skin that may have been exposed to sandfly bites.3 The lesion may not appear until weeks to months or even years after the initial inoculation.2 Initially, CL manifests as papules that may progress to nodular plaques, with eventual evolution to volcanic ulcerations with raised borders and central crateriform indentations covered by scabs or crusting.2,3 The infection may be localized or diffuse—in either case, development of satellite lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, and/or nodular lymphangitis is not uncommon. Generally, CL is not lethal, but the severity of the lesions may vary and can lead to permanent scarring and atrophy.2 Many cases of CL remain undiagnosed because of its appearance as a nonspecific ulcer that can mimic many other cutaneous lesions and because it generally heals spontaneously, leaving only scarring as an indicator of prior infection.4 Thus, CL requires a high diagnostic suspicion, as it can have a nonspecific presentation and is rare in nonendemic regions.

Diagnosis of CL is accomplished via microscopy, isoenzyme analysis, or serology or is made molecularly.3 Microscopic diagnosis includes visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, the stage of replication that occurs after the promastigote stage is phagocytosed by macrophages.3 Amastigote is the only stage that can be visualized in human tissue and is stained via Giemsa and/or hematoxylin and eosin.3 However, Leishmania amastigotes are morphologically indistinguishable from Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes on microscopy, thus limiting diagnostic accuracy.3 Moreover, there is potential for missed diagnosis of persistent CL caused by L tropica due to fewer parasites being present, further complicating the diagnosis.5 In these cases, molecular diagnostics are helpful as they have higher sensitivity and quicker results. Additionally, DNA technologies can differentiate strains, which is beneficial for guiding treatment. Isoenzyme analysis also can help identify Leishmania species, although results can take weeks to return.3 Serologic testing is useful for suspected visceral leishmaniasis despite negative definitive diagnoses or conflicts with conducting definitive studies; however, there is not a strong antibody response in CL, thus serology is ineffective.3,5 Furthermore, serology can have cross-reactivity with T cruzi and cannot be used to assess for treatment response.3,5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for diagnosis of leishmaniasis recommend using multiple methods to ensure a positive result, with molecular assays being the most sensitive.5

Differential diagnoses include any cause of cutaneous ulcerated lesions, including but not limited to mycobacterial or fungal infections. Leprosy often initially manifests with a hypopigmented macule with a raised border, although there often are associated neuropathic symptoms.6 Cutaneous tuberculosis is an extremely rare manifestation that occurs via direct inoculation of the mycobacterium, occurring primarily in children. Initially, it may manifest as a firm red papule that progresses to a painless shallow ulcer with a granular base.7 Cutaneous chromoblastomycosis is a fungal infection resulting from an initial cutaneous injury, similar to our patient, followed by a slow-developing warty lesion that may heal into ivory scars or spread as plaques on normal skin.8 The verrucous lesions seen in cutaneous chromoblastomycosis tend to manifest on the lower extremities and are unlikely to manifest on the head. Sarcoidosis is another granulomatous skin eruption that can be clinically nonspecific.9 Histologically, lesions may demonstrate noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, as seen with cutaneous leishmaniasis, with a broad presentation; for example, lupus pernio, a sarcoid variant, manifests as large blue-red dusky nodules/plaques on the face, ears, or digits.9 Other sarcoid lesions include red/brown, thickened, circular plaques; variably discolored papulonodular lesions; or mucosal involvement.9 Ultimately, it is important to differentiate these nonspecific and similarly appearing lesions through diagnostic techniques such as AFB culture and smear, fungal staining, tuberculosis testing, and PCR in more challenging cases.

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis should be individualized to each case.5 A more than 50% reduction in lesion size within 4 to 6 weeks indicates successful treatment. Ulcerated lesions should be fully re-epithelialized and healed by 3 months posttreatment. Treatment failure is categorized by failure of reepithelization, incomplete healing by 3 months, or worsening of the lesion at any time, each necessitating additional treatment, such as a second course of miltefosine or a different medication regimen.5 Careful monitoring is required throughout treatment, assessing for treatment failure, adding to the challenges of leishmaniasis.

In conclusion, CL requires a high index of suspicion in nonendemic areas to ensure successful diagnosis and treatment. Our case highlights the importance of using multimodal diagnostic techniques for CL, as a single modality may not exhibit a positive result due to variations in diagnostic accuracy. Our case also exhibits the complex treatment of CL, and the considerations that should be made when choosing a treatment modality.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Clinical overview of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/leishmaniasis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- CDC DPDx Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/leishmaniasis/index.html

- Stark CG. Leishmaniasis differential diagnoses. Medscape. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/220298-differential

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:E202-E264. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw670

- Lewis FS. Dermatologic manifestations of leprosy. Medscape. June 19, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104977-overview

- Ngan V. Cutaneous tuberculosis. DermNet. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-tuberculosis

- Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis. Medscape. May 13, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-overview#a4

- Elyoussfi S, Coulson I. Sarcoidosis. DermNet. May 31, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/sarcoidosis

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results demonstrated a nonspecific chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, including few multinucleated histiocytes, a surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate, mostly mature lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and fragmented neutrophils. A special stain panel was negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff for fungi. Bacterial cultures from biopsy tissue grew normal skin flora, and both fungal and AFB cultures were negative. A second punch biopsy was recommended by infectious disease due to clinical suspicion of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Histopathology showed nonnecrotizing granulomas with dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and negative Giemsa staining for Leishmania amastigotes; however, it was concluded by pathology that the reason for the negative Leishmania staining was the late stage of the disease, indicated by the presence of granulomas, which can make visualization of organisms difficult. Nonetheless, universal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was positive for Leishmania tropica. Thus, although microscopic analysis was negative for visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, molecular analysis via PCR ultimately demonstrated a positive result and confirmed the diagnosis of CL (Figure 1). The variance in diagnostic accuracy exemplified in our case reinforces the need for multimodal diagnosis.

Multiple factors needed to be considered with regard to treatment in our patient, including but not limited to the location of the lesion on a slow-healing cartilaginous surface and the patient’s age. Considering the recalcitrant nature of the lesion and the L tropica strain exhibiting resistance to topical treatments, systemic therapies were the only option. Furthermore, parenteral routes of administration were confounded by the patient’s age, decreasing the likelihood of compliance with therapy. With these variables in mind and recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the best treatment for our patient was deemed to be a 28-day course of oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily. Compared to the initial presentation, a 1-month follow-up visit after completing the 28-day course of treatment demonstrated flattening of the lesion (Figure 2).

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by a protozoan parasite of the Leishmania genus, spread via inoculation from the bite of sandfly vectors.1 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common clinical manifestation of leishmaniasis. Other clinical manifestations include mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis.1,2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis typically manifests as open wounds on areas of skin that may have been exposed to sandfly bites.3 The lesion may not appear until weeks to months or even years after the initial inoculation.2 Initially, CL manifests as papules that may progress to nodular plaques, with eventual evolution to volcanic ulcerations with raised borders and central crateriform indentations covered by scabs or crusting.2,3 The infection may be localized or diffuse—in either case, development of satellite lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, and/or nodular lymphangitis is not uncommon. Generally, CL is not lethal, but the severity of the lesions may vary and can lead to permanent scarring and atrophy.2 Many cases of CL remain undiagnosed because of its appearance as a nonspecific ulcer that can mimic many other cutaneous lesions and because it generally heals spontaneously, leaving only scarring as an indicator of prior infection.4 Thus, CL requires a high diagnostic suspicion, as it can have a nonspecific presentation and is rare in nonendemic regions.

Diagnosis of CL is accomplished via microscopy, isoenzyme analysis, or serology or is made molecularly.3 Microscopic diagnosis includes visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, the stage of replication that occurs after the promastigote stage is phagocytosed by macrophages.3 Amastigote is the only stage that can be visualized in human tissue and is stained via Giemsa and/or hematoxylin and eosin.3 However, Leishmania amastigotes are morphologically indistinguishable from Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes on microscopy, thus limiting diagnostic accuracy.3 Moreover, there is potential for missed diagnosis of persistent CL caused by L tropica due to fewer parasites being present, further complicating the diagnosis.5 In these cases, molecular diagnostics are helpful as they have higher sensitivity and quicker results. Additionally, DNA technologies can differentiate strains, which is beneficial for guiding treatment. Isoenzyme analysis also can help identify Leishmania species, although results can take weeks to return.3 Serologic testing is useful for suspected visceral leishmaniasis despite negative definitive diagnoses or conflicts with conducting definitive studies; however, there is not a strong antibody response in CL, thus serology is ineffective.3,5 Furthermore, serology can have cross-reactivity with T cruzi and cannot be used to assess for treatment response.3,5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for diagnosis of leishmaniasis recommend using multiple methods to ensure a positive result, with molecular assays being the most sensitive.5

Differential diagnoses include any cause of cutaneous ulcerated lesions, including but not limited to mycobacterial or fungal infections. Leprosy often initially manifests with a hypopigmented macule with a raised border, although there often are associated neuropathic symptoms.6 Cutaneous tuberculosis is an extremely rare manifestation that occurs via direct inoculation of the mycobacterium, occurring primarily in children. Initially, it may manifest as a firm red papule that progresses to a painless shallow ulcer with a granular base.7 Cutaneous chromoblastomycosis is a fungal infection resulting from an initial cutaneous injury, similar to our patient, followed by a slow-developing warty lesion that may heal into ivory scars or spread as plaques on normal skin.8 The verrucous lesions seen in cutaneous chromoblastomycosis tend to manifest on the lower extremities and are unlikely to manifest on the head. Sarcoidosis is another granulomatous skin eruption that can be clinically nonspecific.9 Histologically, lesions may demonstrate noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, as seen with cutaneous leishmaniasis, with a broad presentation; for example, lupus pernio, a sarcoid variant, manifests as large blue-red dusky nodules/plaques on the face, ears, or digits.9 Other sarcoid lesions include red/brown, thickened, circular plaques; variably discolored papulonodular lesions; or mucosal involvement.9 Ultimately, it is important to differentiate these nonspecific and similarly appearing lesions through diagnostic techniques such as AFB culture and smear, fungal staining, tuberculosis testing, and PCR in more challenging cases.

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis should be individualized to each case.5 A more than 50% reduction in lesion size within 4 to 6 weeks indicates successful treatment. Ulcerated lesions should be fully re-epithelialized and healed by 3 months posttreatment. Treatment failure is categorized by failure of reepithelization, incomplete healing by 3 months, or worsening of the lesion at any time, each necessitating additional treatment, such as a second course of miltefosine or a different medication regimen.5 Careful monitoring is required throughout treatment, assessing for treatment failure, adding to the challenges of leishmaniasis.

In conclusion, CL requires a high index of suspicion in nonendemic areas to ensure successful diagnosis and treatment. Our case highlights the importance of using multimodal diagnostic techniques for CL, as a single modality may not exhibit a positive result due to variations in diagnostic accuracy. Our case also exhibits the complex treatment of CL, and the considerations that should be made when choosing a treatment modality.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results demonstrated a nonspecific chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, including few multinucleated histiocytes, a surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate, mostly mature lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and fragmented neutrophils. A special stain panel was negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff for fungi. Bacterial cultures from biopsy tissue grew normal skin flora, and both fungal and AFB cultures were negative. A second punch biopsy was recommended by infectious disease due to clinical suspicion of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Histopathology showed nonnecrotizing granulomas with dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and negative Giemsa staining for Leishmania amastigotes; however, it was concluded by pathology that the reason for the negative Leishmania staining was the late stage of the disease, indicated by the presence of granulomas, which can make visualization of organisms difficult. Nonetheless, universal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was positive for Leishmania tropica. Thus, although microscopic analysis was negative for visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, molecular analysis via PCR ultimately demonstrated a positive result and confirmed the diagnosis of CL (Figure 1). The variance in diagnostic accuracy exemplified in our case reinforces the need for multimodal diagnosis.

Multiple factors needed to be considered with regard to treatment in our patient, including but not limited to the location of the lesion on a slow-healing cartilaginous surface and the patient’s age. Considering the recalcitrant nature of the lesion and the L tropica strain exhibiting resistance to topical treatments, systemic therapies were the only option. Furthermore, parenteral routes of administration were confounded by the patient’s age, decreasing the likelihood of compliance with therapy. With these variables in mind and recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the best treatment for our patient was deemed to be a 28-day course of oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily. Compared to the initial presentation, a 1-month follow-up visit after completing the 28-day course of treatment demonstrated flattening of the lesion (Figure 2).

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by a protozoan parasite of the Leishmania genus, spread via inoculation from the bite of sandfly vectors.1 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common clinical manifestation of leishmaniasis. Other clinical manifestations include mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis.1,2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis typically manifests as open wounds on areas of skin that may have been exposed to sandfly bites.3 The lesion may not appear until weeks to months or even years after the initial inoculation.2 Initially, CL manifests as papules that may progress to nodular plaques, with eventual evolution to volcanic ulcerations with raised borders and central crateriform indentations covered by scabs or crusting.2,3 The infection may be localized or diffuse—in either case, development of satellite lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, and/or nodular lymphangitis is not uncommon. Generally, CL is not lethal, but the severity of the lesions may vary and can lead to permanent scarring and atrophy.2 Many cases of CL remain undiagnosed because of its appearance as a nonspecific ulcer that can mimic many other cutaneous lesions and because it generally heals spontaneously, leaving only scarring as an indicator of prior infection.4 Thus, CL requires a high diagnostic suspicion, as it can have a nonspecific presentation and is rare in nonendemic regions.

Diagnosis of CL is accomplished via microscopy, isoenzyme analysis, or serology or is made molecularly.3 Microscopic diagnosis includes visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, the stage of replication that occurs after the promastigote stage is phagocytosed by macrophages.3 Amastigote is the only stage that can be visualized in human tissue and is stained via Giemsa and/or hematoxylin and eosin.3 However, Leishmania amastigotes are morphologically indistinguishable from Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes on microscopy, thus limiting diagnostic accuracy.3 Moreover, there is potential for missed diagnosis of persistent CL caused by L tropica due to fewer parasites being present, further complicating the diagnosis.5 In these cases, molecular diagnostics are helpful as they have higher sensitivity and quicker results. Additionally, DNA technologies can differentiate strains, which is beneficial for guiding treatment. Isoenzyme analysis also can help identify Leishmania species, although results can take weeks to return.3 Serologic testing is useful for suspected visceral leishmaniasis despite negative definitive diagnoses or conflicts with conducting definitive studies; however, there is not a strong antibody response in CL, thus serology is ineffective.3,5 Furthermore, serology can have cross-reactivity with T cruzi and cannot be used to assess for treatment response.3,5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for diagnosis of leishmaniasis recommend using multiple methods to ensure a positive result, with molecular assays being the most sensitive.5

Differential diagnoses include any cause of cutaneous ulcerated lesions, including but not limited to mycobacterial or fungal infections. Leprosy often initially manifests with a hypopigmented macule with a raised border, although there often are associated neuropathic symptoms.6 Cutaneous tuberculosis is an extremely rare manifestation that occurs via direct inoculation of the mycobacterium, occurring primarily in children. Initially, it may manifest as a firm red papule that progresses to a painless shallow ulcer with a granular base.7 Cutaneous chromoblastomycosis is a fungal infection resulting from an initial cutaneous injury, similar to our patient, followed by a slow-developing warty lesion that may heal into ivory scars or spread as plaques on normal skin.8 The verrucous lesions seen in cutaneous chromoblastomycosis tend to manifest on the lower extremities and are unlikely to manifest on the head. Sarcoidosis is another granulomatous skin eruption that can be clinically nonspecific.9 Histologically, lesions may demonstrate noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, as seen with cutaneous leishmaniasis, with a broad presentation; for example, lupus pernio, a sarcoid variant, manifests as large blue-red dusky nodules/plaques on the face, ears, or digits.9 Other sarcoid lesions include red/brown, thickened, circular plaques; variably discolored papulonodular lesions; or mucosal involvement.9 Ultimately, it is important to differentiate these nonspecific and similarly appearing lesions through diagnostic techniques such as AFB culture and smear, fungal staining, tuberculosis testing, and PCR in more challenging cases.

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis should be individualized to each case.5 A more than 50% reduction in lesion size within 4 to 6 weeks indicates successful treatment. Ulcerated lesions should be fully re-epithelialized and healed by 3 months posttreatment. Treatment failure is categorized by failure of reepithelization, incomplete healing by 3 months, or worsening of the lesion at any time, each necessitating additional treatment, such as a second course of miltefosine or a different medication regimen.5 Careful monitoring is required throughout treatment, assessing for treatment failure, adding to the challenges of leishmaniasis.

In conclusion, CL requires a high index of suspicion in nonendemic areas to ensure successful diagnosis and treatment. Our case highlights the importance of using multimodal diagnostic techniques for CL, as a single modality may not exhibit a positive result due to variations in diagnostic accuracy. Our case also exhibits the complex treatment of CL, and the considerations that should be made when choosing a treatment modality.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Clinical overview of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/leishmaniasis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- CDC DPDx Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/leishmaniasis/index.html

- Stark CG. Leishmaniasis differential diagnoses. Medscape. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/220298-differential

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:E202-E264. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw670

- Lewis FS. Dermatologic manifestations of leprosy. Medscape. June 19, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104977-overview

- Ngan V. Cutaneous tuberculosis. DermNet. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-tuberculosis

- Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis. Medscape. May 13, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-overview#a4

- Elyoussfi S, Coulson I. Sarcoidosis. DermNet. May 31, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/sarcoidosis

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Clinical overview of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/leishmaniasis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- CDC DPDx Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/leishmaniasis/index.html

- Stark CG. Leishmaniasis differential diagnoses. Medscape. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/220298-differential

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:E202-E264. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw670

- Lewis FS. Dermatologic manifestations of leprosy. Medscape. June 19, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104977-overview

- Ngan V. Cutaneous tuberculosis. DermNet. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-tuberculosis

- Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis. Medscape. May 13, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-overview#a4

- Elyoussfi S, Coulson I. Sarcoidosis. DermNet. May 31, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/sarcoidosis

Nonhealing Lesion on the Ear in a Child

Nonhealing Lesion on the Ear in a Child

A 10-year-old boy who recently emigrated from Afghanistan presented to his pediatrician for evaluation of a painless nonhealing plaque on the posterior left pinna of more than 1 year's duration. The lesion reportedly started as a small scratch following an ear injury, initially improved with an unknown topical treatment administered in Afghanistan, and then recurred with no other associated lesions and no known insect bite. The lesion persisted for more than 1 year postemigration before the patient presented to his pediatrician, who noted signs of excoriation, which was confirmed by the patient's father. The patient was started on a 7-day course of cephalexin oral suspension and topical mupirocin 2%. After 2 months without improvement, a 2-week course of oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was initiated; however, the lesion continued to grow with no signs of healing, and he was referred to dermatology.

The patient presented to pediatric dermatology 3 months after the initial presentation to his pediatrician and 2 weeks after he completed the course of oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Physical examination demonstrated a papulosquamous eruption with swelling and blistering on the helix of the left ear. Based on these findings, the patient was started on a 1-month trial of topical triamcinolone 1% followed by the addition of topical pimecrolimus 1%. Due to no improvement of the lesion and subsequent progression to ulceration, a punch biopsy was performed.

Progressive Dystrophy of the Fingernails and Toenails

Progressive Dystrophy of the Fingernails and Toenails

THE DIAGNOSIS: Nail Lichen Planus

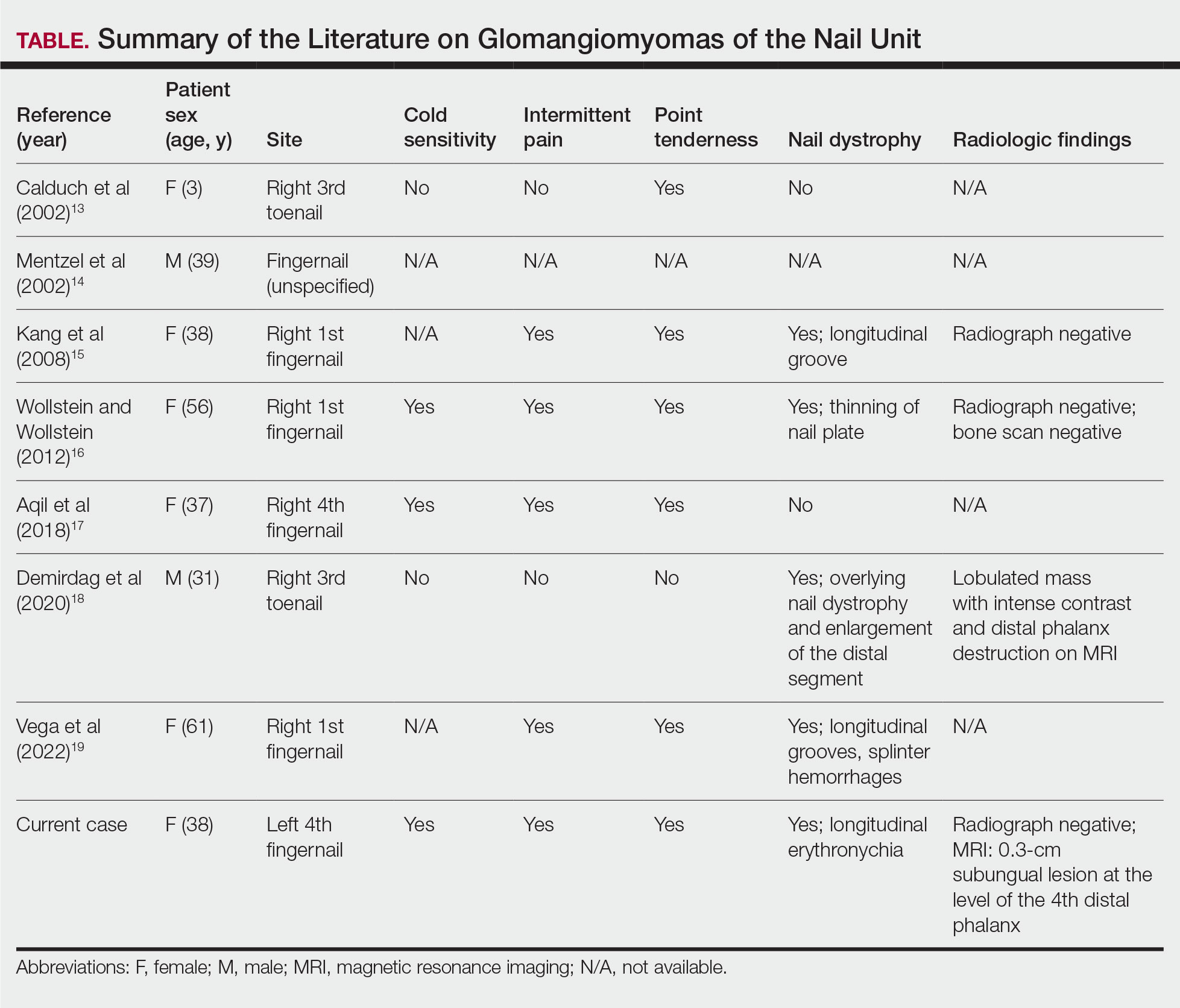

The biopsy results showed features of hypergranulosis of the matricial epithelium, irregular acanthosis, apoptotic keratinocytes along the basal layer, and a lichenoid infiltrate consistent with nail lichen planus. The patient was started on topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% applied once daily under overnight occlusion. Additionally, intramatricial triamcinolone acetonide (2.5 mg/mL; 0.1 mL per injection) was administered into the affected nail matrix at 4-week intervals for a total of 2 sessions. At the 2-month follow-up visit, the patient reported improvement in longitudinal ridging; however, he subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Nail lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disorder that occurs in 10% to 15% of patients with lichen planus worldwide and is more common in adults than children.1 It can manifest independently or concurrently with cutaneous and/or oral mucosal involvement. The fingernails are more commonly affected than the toenails.2 The clinical features of nail lichen planus can be classified based on involvement of the nail matrix (longitudinal ridging, red lunula, thinning of the nail plate, koilonychia, trachyonychia, pterygium, and anonychia) or nail bed (onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhages).1

In our patient, who presented with chronic progressive nail dystrophy affecting all 20 nails, onychomycosis, nail psoriasis, onychotillomania, and idiopathic trachyonychia were included in the differential.1

Onychomycosis manifests as white or yellow-brown discoloration of the nail, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and thickening of the nail plate. Diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of septate hyphae (dermatophytes) or budding yeast cells (Candida species) on a potassium hydroxide mount. Other diagnostic modalities include dermoscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology of nail clippings, with demonstration of fungal elements identified on periodic acid-Schiff staining (eFigure 1).3

Nail psoriasis characteristically manifests as deep irregular pitting of the nails. Other features favoring psoriasis include involvement of the nail matrix manifesting as leukonychia, red lunula, and crumbling, as well as involvement of the nail bed manifesting as onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, salmon patches/oil spots, and splinter hemorrhages (eFigure 2).4 Diagnosis primarily is clinical, supported by histopathology when uncertainty exists.

Onychotillomania is a behavioral disorder characterized by an irresistible urge or impulse in patients to either pick or pull at their fingernails and/or toenails. Clinicopathologic features of the involved nails are nonspecific and atypical, with possible involvement of periungual and digital skin. Diagnosis of onychotillomania is challenging.5 Dermoscopic features including anonychia with multiple obliquely arranged nail bed hemorrhages, gray pigmentation of the nail bed, and wavy lines, has been proposed to aid the diagnosis of onychotillomania.6

Idiopathic trachyonychia is isolated nail involvement characterized by rough, ridged, and thin nails affecting multiple or all of the fingernails and toenails without an underlying systemic or dermatologic condition (eFigure 3). The terms trachyonychia and 20-nail dystrophy have been used interchangeably in the literature; however, trachyonychia does not always involve all 20 nails. Other conditions causing widespread dystrophy of all 20 nails cannot be diagnosed as 20-nail dystrophy or trachyonychia without the distinct morphologic features of thin brittle nails with pronounced longitudinal ridging.7

Prompt diagnosis and early intervention in nail lichen planus is crucial due to the potential for irreversible scarring. First-line treatment options include intramatricial and intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide for 3 to 6 months.4 Second-line therapies include oral retinoids such as acitretin and alitretinoin and immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine. Other reported treatment options include clobetasol propionate, tacrolimus, dapsone, griseofulvin, etanercept, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, and UV therapy.4

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Onychomycosis: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2020;14:32-45. doi:10.2174/1872213X13666191026090713

- Hwang JK, Grover C, Iorizzo M, et al. Nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus: updates on diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:585-596. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.11.024

- Sidiropoulou P, Sgouros D, Theodoropoulos K, et al. Onychotillomania: a chameleon-like disorder: case report and review of literature. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:104-107. doi:10.1159/000489941

- Maddy AJ, Tosti A. Dermoscopic features of onychotillomania: a study of 36 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:702-705. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2018.04.015

- Haber JS, Chairatchaneeboon M, Rubin AI. Trachyonychia: review and update on clinical aspects, histology, and therapy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2:109-115. doi:10.1159/000449063

THE DIAGNOSIS: Nail Lichen Planus

The biopsy results showed features of hypergranulosis of the matricial epithelium, irregular acanthosis, apoptotic keratinocytes along the basal layer, and a lichenoid infiltrate consistent with nail lichen planus. The patient was started on topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% applied once daily under overnight occlusion. Additionally, intramatricial triamcinolone acetonide (2.5 mg/mL; 0.1 mL per injection) was administered into the affected nail matrix at 4-week intervals for a total of 2 sessions. At the 2-month follow-up visit, the patient reported improvement in longitudinal ridging; however, he subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Nail lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disorder that occurs in 10% to 15% of patients with lichen planus worldwide and is more common in adults than children.1 It can manifest independently or concurrently with cutaneous and/or oral mucosal involvement. The fingernails are more commonly affected than the toenails.2 The clinical features of nail lichen planus can be classified based on involvement of the nail matrix (longitudinal ridging, red lunula, thinning of the nail plate, koilonychia, trachyonychia, pterygium, and anonychia) or nail bed (onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhages).1

In our patient, who presented with chronic progressive nail dystrophy affecting all 20 nails, onychomycosis, nail psoriasis, onychotillomania, and idiopathic trachyonychia were included in the differential.1

Onychomycosis manifests as white or yellow-brown discoloration of the nail, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and thickening of the nail plate. Diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of septate hyphae (dermatophytes) or budding yeast cells (Candida species) on a potassium hydroxide mount. Other diagnostic modalities include dermoscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology of nail clippings, with demonstration of fungal elements identified on periodic acid-Schiff staining (eFigure 1).3

Nail psoriasis characteristically manifests as deep irregular pitting of the nails. Other features favoring psoriasis include involvement of the nail matrix manifesting as leukonychia, red lunula, and crumbling, as well as involvement of the nail bed manifesting as onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, salmon patches/oil spots, and splinter hemorrhages (eFigure 2).4 Diagnosis primarily is clinical, supported by histopathology when uncertainty exists.

Onychotillomania is a behavioral disorder characterized by an irresistible urge or impulse in patients to either pick or pull at their fingernails and/or toenails. Clinicopathologic features of the involved nails are nonspecific and atypical, with possible involvement of periungual and digital skin. Diagnosis of onychotillomania is challenging.5 Dermoscopic features including anonychia with multiple obliquely arranged nail bed hemorrhages, gray pigmentation of the nail bed, and wavy lines, has been proposed to aid the diagnosis of onychotillomania.6

Idiopathic trachyonychia is isolated nail involvement characterized by rough, ridged, and thin nails affecting multiple or all of the fingernails and toenails without an underlying systemic or dermatologic condition (eFigure 3). The terms trachyonychia and 20-nail dystrophy have been used interchangeably in the literature; however, trachyonychia does not always involve all 20 nails. Other conditions causing widespread dystrophy of all 20 nails cannot be diagnosed as 20-nail dystrophy or trachyonychia without the distinct morphologic features of thin brittle nails with pronounced longitudinal ridging.7

Prompt diagnosis and early intervention in nail lichen planus is crucial due to the potential for irreversible scarring. First-line treatment options include intramatricial and intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide for 3 to 6 months.4 Second-line therapies include oral retinoids such as acitretin and alitretinoin and immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine. Other reported treatment options include clobetasol propionate, tacrolimus, dapsone, griseofulvin, etanercept, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, and UV therapy.4

THE DIAGNOSIS: Nail Lichen Planus

The biopsy results showed features of hypergranulosis of the matricial epithelium, irregular acanthosis, apoptotic keratinocytes along the basal layer, and a lichenoid infiltrate consistent with nail lichen planus. The patient was started on topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% applied once daily under overnight occlusion. Additionally, intramatricial triamcinolone acetonide (2.5 mg/mL; 0.1 mL per injection) was administered into the affected nail matrix at 4-week intervals for a total of 2 sessions. At the 2-month follow-up visit, the patient reported improvement in longitudinal ridging; however, he subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Nail lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disorder that occurs in 10% to 15% of patients with lichen planus worldwide and is more common in adults than children.1 It can manifest independently or concurrently with cutaneous and/or oral mucosal involvement. The fingernails are more commonly affected than the toenails.2 The clinical features of nail lichen planus can be classified based on involvement of the nail matrix (longitudinal ridging, red lunula, thinning of the nail plate, koilonychia, trachyonychia, pterygium, and anonychia) or nail bed (onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhages).1

In our patient, who presented with chronic progressive nail dystrophy affecting all 20 nails, onychomycosis, nail psoriasis, onychotillomania, and idiopathic trachyonychia were included in the differential.1

Onychomycosis manifests as white or yellow-brown discoloration of the nail, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and thickening of the nail plate. Diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of septate hyphae (dermatophytes) or budding yeast cells (Candida species) on a potassium hydroxide mount. Other diagnostic modalities include dermoscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology of nail clippings, with demonstration of fungal elements identified on periodic acid-Schiff staining (eFigure 1).3

Nail psoriasis characteristically manifests as deep irregular pitting of the nails. Other features favoring psoriasis include involvement of the nail matrix manifesting as leukonychia, red lunula, and crumbling, as well as involvement of the nail bed manifesting as onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, salmon patches/oil spots, and splinter hemorrhages (eFigure 2).4 Diagnosis primarily is clinical, supported by histopathology when uncertainty exists.

Onychotillomania is a behavioral disorder characterized by an irresistible urge or impulse in patients to either pick or pull at their fingernails and/or toenails. Clinicopathologic features of the involved nails are nonspecific and atypical, with possible involvement of periungual and digital skin. Diagnosis of onychotillomania is challenging.5 Dermoscopic features including anonychia with multiple obliquely arranged nail bed hemorrhages, gray pigmentation of the nail bed, and wavy lines, has been proposed to aid the diagnosis of onychotillomania.6

Idiopathic trachyonychia is isolated nail involvement characterized by rough, ridged, and thin nails affecting multiple or all of the fingernails and toenails without an underlying systemic or dermatologic condition (eFigure 3). The terms trachyonychia and 20-nail dystrophy have been used interchangeably in the literature; however, trachyonychia does not always involve all 20 nails. Other conditions causing widespread dystrophy of all 20 nails cannot be diagnosed as 20-nail dystrophy or trachyonychia without the distinct morphologic features of thin brittle nails with pronounced longitudinal ridging.7

Prompt diagnosis and early intervention in nail lichen planus is crucial due to the potential for irreversible scarring. First-line treatment options include intramatricial and intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide for 3 to 6 months.4 Second-line therapies include oral retinoids such as acitretin and alitretinoin and immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine. Other reported treatment options include clobetasol propionate, tacrolimus, dapsone, griseofulvin, etanercept, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, and UV therapy.4

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Onychomycosis: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2020;14:32-45. doi:10.2174/1872213X13666191026090713

- Hwang JK, Grover C, Iorizzo M, et al. Nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus: updates on diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:585-596. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.11.024

- Sidiropoulou P, Sgouros D, Theodoropoulos K, et al. Onychotillomania: a chameleon-like disorder: case report and review of literature. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:104-107. doi:10.1159/000489941

- Maddy AJ, Tosti A. Dermoscopic features of onychotillomania: a study of 36 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:702-705. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2018.04.015

- Haber JS, Chairatchaneeboon M, Rubin AI. Trachyonychia: review and update on clinical aspects, histology, and therapy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2:109-115. doi:10.1159/000449063

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Onychomycosis: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2020;14:32-45. doi:10.2174/1872213X13666191026090713

- Hwang JK, Grover C, Iorizzo M, et al. Nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus: updates on diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:585-596. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.11.024

- Sidiropoulou P, Sgouros D, Theodoropoulos K, et al. Onychotillomania: a chameleon-like disorder: case report and review of literature. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:104-107. doi:10.1159/000489941

- Maddy AJ, Tosti A. Dermoscopic features of onychotillomania: a study of 36 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:702-705. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2018.04.015

- Haber JS, Chairatchaneeboon M, Rubin AI. Trachyonychia: review and update on clinical aspects, histology, and therapy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2:109-115. doi:10.1159/000449063

Progressive Dystrophy of the Fingernails and Toenails

Progressive Dystrophy of the Fingernails and Toenails

A 35-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with gradually progressive dystrophy of the fingernails and toenails of 20 years’ duration. The patient reported no history of other dermatologic conditions. Physical examination revealed longitudinal ridging of all 20 nails and discoloration of the nail plates, as well as a few nails showing pterygium and anonychia; the skin and mucosal surfaces were otherwise normal, and nail plate thinning was not observed. A potassium hydroxide mount was negative. A biopsy of the nail matrix on the left thumbnail was performed.

Cobblestonelike Papules on the Neck

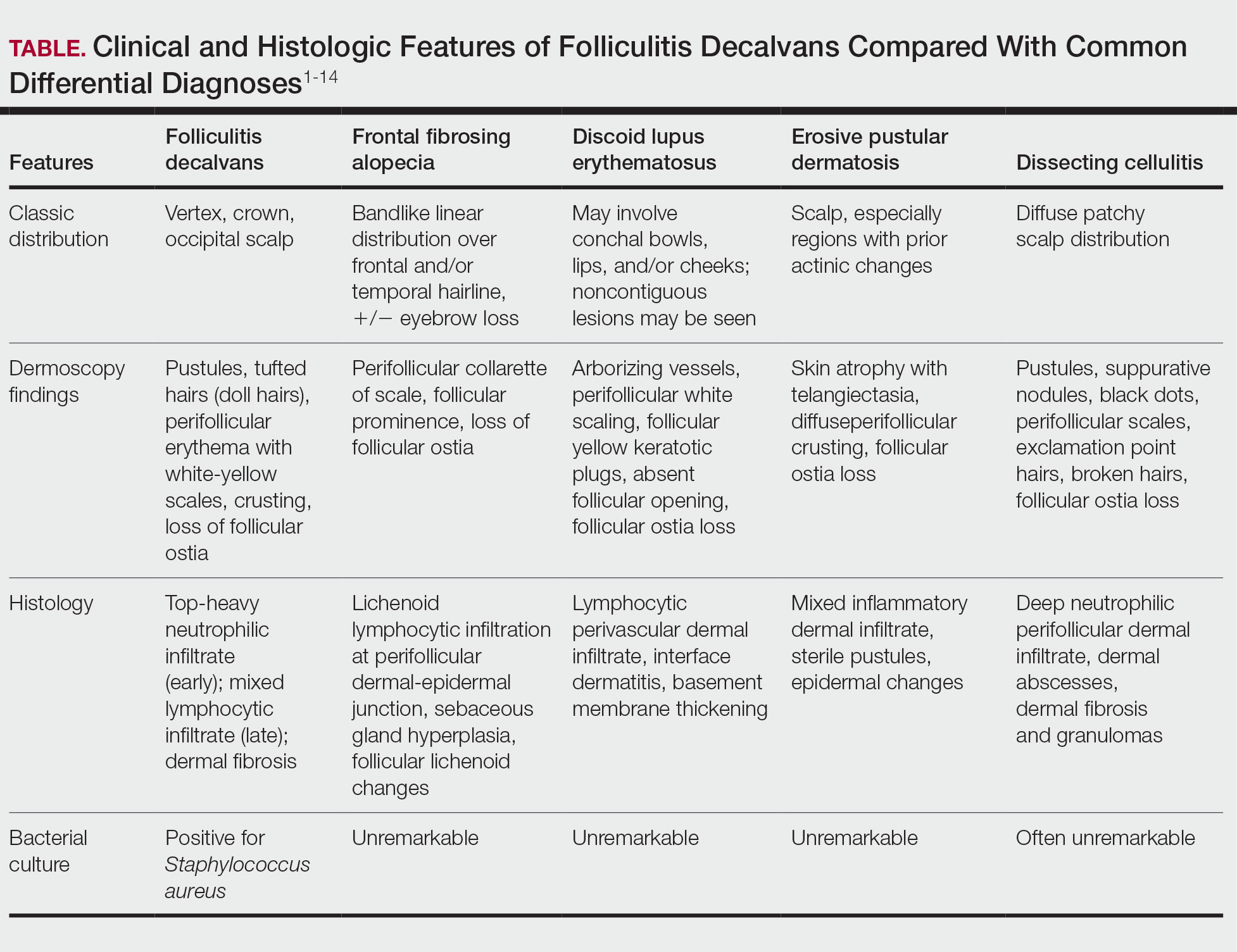

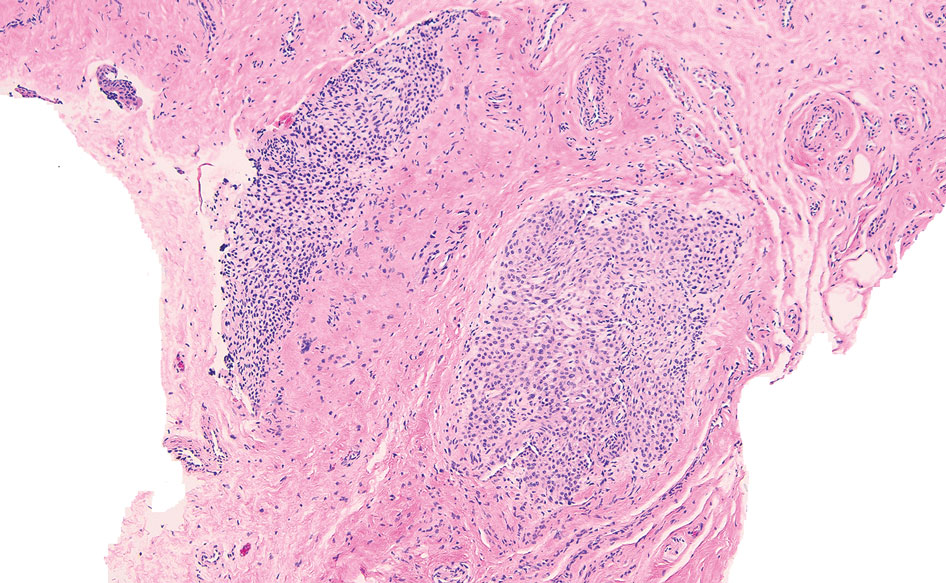

The Diagnosis: Fibroelastolytic Papulosis

Histopathology demonstrated decreased density and fragmentation of elastic fibers in the superficial reticular and papillary dermis consistent with an elastolytic disease process (Figure). Of note, elastolysis typically is visualized with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain but cannot be visualized well with standard hematoxylin and eosin staining. Additional staining with Congo red was negative for amyloid, and colloidal iron did not show any increase in dermal mucin, ruling out amyloidosis and scleromyxedema, respectively. Based on the histopathologic findings and the clinical history, a diagnosis of fibroelastolytic papulosis (FP) was made. Given the benign nature of the condition, the patient was prescribed a topical steroid (clobetasol 0.05%) for symptomatic relief.

Cutaneous conditions can arise from abnormalities in the elastin composition of connective tissue due to abnormal elastin formation or degradation (elastolysis).1 Fibroelastolytic papulosis is a distinct elastolytic disorder diagnosed histologically by a notable loss of elastic fibers localized to the papillary dermis.2 Fibroelastolytic papulosis is an acquired condition linked to exposure to UV radiation, abnormal elastogenesis, and hormonal factors that commonly involves the neck, supraclavicular area, and upper back.1-3 Predominantly affecting elderly women, FP is characterized by soft white papules that often coalesce into a cobblestonelike plaque.2 Because the condition rarely is seen in men, there is speculation that it may involve genetic, hereditary, and hormonal factors that have yet to be identified.1

Fibroelastolytic papulosis can be classified as either pseudoxanthoma elasticum–like papillary dermal elastolysis or white fibrous papulosis.2,3 White fibrous papulosis manifests with haphazardly arranged collagen fibers in the reticular and deep dermis with papillary dermal elastolysis and most commonly develops on the neck.3 Although our patient’s lesion was on the neck, the absence of thickened collagen bands on histology supported classification as the pseudoxanthoma elasticum– like papillary dermal elastolysis subtype.

Fibroelastolytic papulosis can be distinguished from other elastic abnormalities by its characteristic clinical appearance, demographic distribution, and associated histopathologic findings. The differential diagnosis of FP includes pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), anetoderma, scleromyxedema, and lichen amyloidosis.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a hereditary or acquired multisystem disease characterized by fragmentation and calcification of elastic fibers in the mid dermis.1,4 Its clinical presentation resembles that of FP, appearing as small, asymptomatic, yellowish or flesh-colored papules in a reticular pattern that progressively coalesce into larger plaques with a cobblestonelike appearance.1 Like FP, PXE commonly affects the flexural creases in women but in contrast may manifest earlier (ie, second or third decades of life). Additionally, the pathogenesis of PXE is not related to UV radiation exposure. The hereditary form develops due to a gene variation, whereas the acquired form may be due to conditions associated with physiologic and/or mechanical stress.1

Anetoderma, also known as macular atrophy, is another condition that demonstrates elastic tissue loss in the dermis on histopathology.1 Anetoderma commonly is seen in younger patients and can be differentiated from FP by the antecedent presence of an inflammatory process. Anetoderma is classified as primary or secondary. Primary anetoderma is associated with prothrombotic abnormalities, while secondary anetoderma is associated with systemic disease including but not limited to sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematous, and Graves disease.1

Neither lichen myxedematosus (LM) nor lichen amyloidosis (LA) are true elastolytic conditions. Lichen myxedematosus is considered in the differential diagnosis of FP due to the associated loss of elastin observed with disease progression. An idiopathic cutaneous mucinosis, LM is a localized form of scleromyxedema, which is characterized by small, firm, waxy papules; mucin deposition in the skin; fibroblast proliferation; and fibrosis. On histologic analysis, typical findings of LM include irregularly arranged fibroblasts, diffuse mucin deposition within the upper and mid reticular dermis, increased collagen deposition, and a decrease in elastin fibers.5

Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare condition characterized by the extracellular deposition of amyloid proteins in the skin and a lack of systemic involvement. Although it is not an elastolytic condition, LA is clinically similar to FP, often manifesting as multiple localized, pruritic, hyperpigmented papules that can coalesce into larger plaques; it tends to develop on the shins, calves, ankles, and thighs.6,7 The condition commonly manifests in the fifth and sixth decades of life; however, in contrast to FP, LA is more prevalent in men and individuals from Central and South American as well as Middle Eastern and non-Chinese Asian populations.8 Lichen amyloidosis is a keratin-derived amyloidosis with cytokeratin-based amyloid precursors that only deposit in the dermis.6 Histopathology reveals colloid bodies due to the presence of apoptotic basal keratinocytes. The etiology of LA is unknown, but on rare occasions it has been associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia 2A rearranged during transfection mutations.6

In summary, FP is an uncommonly diagnosed elastolytic condition that often is asymptomatic or associated with mild pruritus. Biopsy is warranted to help differentiate it from mimicker conditions that may be associated with systemic disease. Currently, there is no established therapy that provides successful treatment. Research suggests unsatisfactory results with the use of topical tretinoin or topical antioxidants.3 More recently, nonablative fractional resurfacing lasers have been evaluated as a possible therapeutic strategy of promise for elastic disorders.9

- Andrés-Ramos I, Alegría-Landa V, Gimeno I, et al. Cutaneous elastic tissue anomalies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:85-117. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001275

- Valbuena V, Assaad D, Yeung J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like papillary dermal elastolysis: a single case report. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:345-347. doi:10.1177/1203475417699407

- Dokic Y, Tschen J. White fibrous papulosis of the axillae and neck. Cureus. 2020;12:E7635. doi:10.7759/cureus.7635

- Recio-Monescillo M, Torre-Castro J, Manzanas C, et al. Papillary dermal elastolysis histopathology mimicking folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:430-433. doi:10.1111/cup.14402

- Cokonis Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.011

- Weidner T, Illing T, Elsner P. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: a systematic treatment review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:629-642. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0278-9

- Ladizinski B, Lee KC. Lichen amyloidosis. CMAJ. 2014;186:532. doi:10.1503/cmaj.130698

- Chen JF, Chen YF. Answer: can you identify this condition? Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:1234-1235.

- Foering K, Torbeck RL, Frank MP, et al. Treatment of pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like papillary dermal elastolysis with nonablative fractional resurfacing laser resulting in clinical and histologic improvement in elastin and collagen. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:382-384. doi:10.1080/14764172.2017.1358457

The Diagnosis: Fibroelastolytic Papulosis

Histopathology demonstrated decreased density and fragmentation of elastic fibers in the superficial reticular and papillary dermis consistent with an elastolytic disease process (Figure). Of note, elastolysis typically is visualized with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain but cannot be visualized well with standard hematoxylin and eosin staining. Additional staining with Congo red was negative for amyloid, and colloidal iron did not show any increase in dermal mucin, ruling out amyloidosis and scleromyxedema, respectively. Based on the histopathologic findings and the clinical history, a diagnosis of fibroelastolytic papulosis (FP) was made. Given the benign nature of the condition, the patient was prescribed a topical steroid (clobetasol 0.05%) for symptomatic relief.

Cutaneous conditions can arise from abnormalities in the elastin composition of connective tissue due to abnormal elastin formation or degradation (elastolysis).1 Fibroelastolytic papulosis is a distinct elastolytic disorder diagnosed histologically by a notable loss of elastic fibers localized to the papillary dermis.2 Fibroelastolytic papulosis is an acquired condition linked to exposure to UV radiation, abnormal elastogenesis, and hormonal factors that commonly involves the neck, supraclavicular area, and upper back.1-3 Predominantly affecting elderly women, FP is characterized by soft white papules that often coalesce into a cobblestonelike plaque.2 Because the condition rarely is seen in men, there is speculation that it may involve genetic, hereditary, and hormonal factors that have yet to be identified.1

Fibroelastolytic papulosis can be classified as either pseudoxanthoma elasticum–like papillary dermal elastolysis or white fibrous papulosis.2,3 White fibrous papulosis manifests with haphazardly arranged collagen fibers in the reticular and deep dermis with papillary dermal elastolysis and most commonly develops on the neck.3 Although our patient’s lesion was on the neck, the absence of thickened collagen bands on histology supported classification as the pseudoxanthoma elasticum– like papillary dermal elastolysis subtype.

Fibroelastolytic papulosis can be distinguished from other elastic abnormalities by its characteristic clinical appearance, demographic distribution, and associated histopathologic findings. The differential diagnosis of FP includes pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), anetoderma, scleromyxedema, and lichen amyloidosis.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a hereditary or acquired multisystem disease characterized by fragmentation and calcification of elastic fibers in the mid dermis.1,4 Its clinical presentation resembles that of FP, appearing as small, asymptomatic, yellowish or flesh-colored papules in a reticular pattern that progressively coalesce into larger plaques with a cobblestonelike appearance.1 Like FP, PXE commonly affects the flexural creases in women but in contrast may manifest earlier (ie, second or third decades of life). Additionally, the pathogenesis of PXE is not related to UV radiation exposure. The hereditary form develops due to a gene variation, whereas the acquired form may be due to conditions associated with physiologic and/or mechanical stress.1

Anetoderma, also known as macular atrophy, is another condition that demonstrates elastic tissue loss in the dermis on histopathology.1 Anetoderma commonly is seen in younger patients and can be differentiated from FP by the antecedent presence of an inflammatory process. Anetoderma is classified as primary or secondary. Primary anetoderma is associated with prothrombotic abnormalities, while secondary anetoderma is associated with systemic disease including but not limited to sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematous, and Graves disease.1