User login

Rochelle Walensky to Lead CDC Amid Challenges

Rochelle Walensky’s, MD, MPH, Twitter bio includes her current job—chief of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital—and her private job: “mother of boys,” referring to her 3 sons. That experience will be critical as she takes on one of the most contentious jobs in recent months. On Dec. 7, 2020, President-elect Biden appointed her to take over from Robert Redfield, MD, as the next head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Unlike many of President-elect Biden’s nominees, including California Attorney General Xavier Becerra who has been tapped for Secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services, Walensky will not require Senate confirmation, meaning she can hit the ground running on Jan. 20—and she plans to. She’ll be taking over a CDC that has come under fire for caving to political interference and vacillated on guidance and testing guidelines as it struggled to maintain credibility amid the worst public health crisis in a century.

Although Walensky is not an expert in respiratory diseases or coronaviruses her Twitter bio contains some of the most reassuring words Americans in the midst of a pandemic could see: “Decision science researcher.”

“On January. 20, I will begin leading the CDC, which was founded in 1946 to meet precisely the kinds of challenges posed by this pandemic,” she wrote in a New York Times op-ed. “I agreed to serve as CDC. director because I believe in the agency’s mission and commitment to knowledge, statistics and guidance. I will do so by leading with facts, science and integrity — and being accountable for them, as the CDC. has done since its founding 75 years ago.”

She went on to insist that as CDC Director, “it will be my responsibility to make sure that the public trusts the agency’s guidance and that its staff feels supported.”

When President-elect Biden introduced her, she addressed the challenges facing the US. “The pandemic that brought me here today is one that struck America and the world more than 30 years ago because my medical training happened to coincide with some of the most harrowing years of the HIV/AIDS crisis. As a medical student, I saw firsthand how the virus ravaged bodies and communities. Inside the hospital, I witnessed people lose strength and hope. While outside the hospital, I witnessed those same patients, mostly gay men and members of vulnerable communities, be stigmatized and marginalized by their nation and many of its leaders.

“Now, a new virus is ravaging us. It’s striking hardest, once again, at the most vulnerable, the marginalized, the underserved. I’m honored to work with an administration that understands that leading with science is the only way to deliver breakthroughs, to deliver hope, and to bring our nation back to full strength. To the American people and to each and every one of you at the CDC, I promise to work with you, to harness the power of American science, to fight this virus and prevent unnecessary illness and deaths so that we can all get back to our lives.”

Among the tools she will have that her predecessor did not (for long) are not 1 but 2 vaccines, and possibly more soon. However, in a paper published in Health Affairs in November, Walensky and her co-authors reported on their mathematical simulation of vaccination that showed factors related to implementation “will contribute more to the success of vaccination programs than a vaccine’s efficacy as determined in clinical trials.” The benefits of a vaccine decline substantially, they add, in the event of manufacturing or deployment delays, or greater epidemic severity. Equally important, they note, is the need to address vaccine hesitancy. “Our findings demonstrate the need,” they wrote, “…to redouble efforts to promote public confidence in COVID-19 vaccines, and to encourage continued adherence to other mitigation approaches, even after a vaccine becomes available.”

In a Facebook Live event sponsored by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, where Walensky received her MPH degree, she said there are other “substantial challenges” in distributing a coronavirus vaccine, including the fact that one quarter of Americans don’t have a primary care physician to guide their care.

Her appointment has won praise from health experts around the world not only for her extensive scientific background (BS degree in biochemistry and molecular biology from Washington University and a MD degree from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine) and experience but also for her communication skills. She regularly appears on CNN and has more than 50,000 followers on social media.

She will need those communication skills to undo the knot of suspicion and resistance surrounding the COVID vaccines. The year is young, but since January 1st, the 7-day average of deaths has exceeded 2,500 deaths every day and is continuing to rise. Hospitals are running out of room to care for those patients, and the many others with other needs. In 2019, according to the CDC’s latest data, more than 30 million people in the US had no health insurance; thousands of Americans now struggling financially are swelling those numbers.

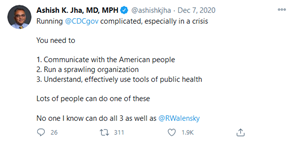

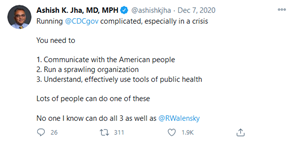

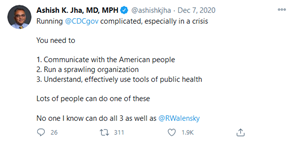

Walensky definitely has her tasks cut out for her—and those are just the ones we know about now. But Ashish Jha, MD, MPH, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, who is also a renowned public health researcher, has no doubts about her capability. In December, he tweeted: “Running @CDCgov complicated, especially in a crisis. You need to 1. Communicate with the American people, 2. Run a sprawling organization, 3. Understand, effectively use tools of public health. Lots of people can do one of these. No one I know can do all 3 as well as @RWalensky.”

Rochelle Walensky’s, MD, MPH, Twitter bio includes her current job—chief of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital—and her private job: “mother of boys,” referring to her 3 sons. That experience will be critical as she takes on one of the most contentious jobs in recent months. On Dec. 7, 2020, President-elect Biden appointed her to take over from Robert Redfield, MD, as the next head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Unlike many of President-elect Biden’s nominees, including California Attorney General Xavier Becerra who has been tapped for Secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services, Walensky will not require Senate confirmation, meaning she can hit the ground running on Jan. 20—and she plans to. She’ll be taking over a CDC that has come under fire for caving to political interference and vacillated on guidance and testing guidelines as it struggled to maintain credibility amid the worst public health crisis in a century.

Although Walensky is not an expert in respiratory diseases or coronaviruses her Twitter bio contains some of the most reassuring words Americans in the midst of a pandemic could see: “Decision science researcher.”

“On January. 20, I will begin leading the CDC, which was founded in 1946 to meet precisely the kinds of challenges posed by this pandemic,” she wrote in a New York Times op-ed. “I agreed to serve as CDC. director because I believe in the agency’s mission and commitment to knowledge, statistics and guidance. I will do so by leading with facts, science and integrity — and being accountable for them, as the CDC. has done since its founding 75 years ago.”

She went on to insist that as CDC Director, “it will be my responsibility to make sure that the public trusts the agency’s guidance and that its staff feels supported.”

When President-elect Biden introduced her, she addressed the challenges facing the US. “The pandemic that brought me here today is one that struck America and the world more than 30 years ago because my medical training happened to coincide with some of the most harrowing years of the HIV/AIDS crisis. As a medical student, I saw firsthand how the virus ravaged bodies and communities. Inside the hospital, I witnessed people lose strength and hope. While outside the hospital, I witnessed those same patients, mostly gay men and members of vulnerable communities, be stigmatized and marginalized by their nation and many of its leaders.

“Now, a new virus is ravaging us. It’s striking hardest, once again, at the most vulnerable, the marginalized, the underserved. I’m honored to work with an administration that understands that leading with science is the only way to deliver breakthroughs, to deliver hope, and to bring our nation back to full strength. To the American people and to each and every one of you at the CDC, I promise to work with you, to harness the power of American science, to fight this virus and prevent unnecessary illness and deaths so that we can all get back to our lives.”

Among the tools she will have that her predecessor did not (for long) are not 1 but 2 vaccines, and possibly more soon. However, in a paper published in Health Affairs in November, Walensky and her co-authors reported on their mathematical simulation of vaccination that showed factors related to implementation “will contribute more to the success of vaccination programs than a vaccine’s efficacy as determined in clinical trials.” The benefits of a vaccine decline substantially, they add, in the event of manufacturing or deployment delays, or greater epidemic severity. Equally important, they note, is the need to address vaccine hesitancy. “Our findings demonstrate the need,” they wrote, “…to redouble efforts to promote public confidence in COVID-19 vaccines, and to encourage continued adherence to other mitigation approaches, even after a vaccine becomes available.”

In a Facebook Live event sponsored by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, where Walensky received her MPH degree, she said there are other “substantial challenges” in distributing a coronavirus vaccine, including the fact that one quarter of Americans don’t have a primary care physician to guide their care.

Her appointment has won praise from health experts around the world not only for her extensive scientific background (BS degree in biochemistry and molecular biology from Washington University and a MD degree from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine) and experience but also for her communication skills. She regularly appears on CNN and has more than 50,000 followers on social media.

She will need those communication skills to undo the knot of suspicion and resistance surrounding the COVID vaccines. The year is young, but since January 1st, the 7-day average of deaths has exceeded 2,500 deaths every day and is continuing to rise. Hospitals are running out of room to care for those patients, and the many others with other needs. In 2019, according to the CDC’s latest data, more than 30 million people in the US had no health insurance; thousands of Americans now struggling financially are swelling those numbers.

Walensky definitely has her tasks cut out for her—and those are just the ones we know about now. But Ashish Jha, MD, MPH, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, who is also a renowned public health researcher, has no doubts about her capability. In December, he tweeted: “Running @CDCgov complicated, especially in a crisis. You need to 1. Communicate with the American people, 2. Run a sprawling organization, 3. Understand, effectively use tools of public health. Lots of people can do one of these. No one I know can do all 3 as well as @RWalensky.”

Rochelle Walensky’s, MD, MPH, Twitter bio includes her current job—chief of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital—and her private job: “mother of boys,” referring to her 3 sons. That experience will be critical as she takes on one of the most contentious jobs in recent months. On Dec. 7, 2020, President-elect Biden appointed her to take over from Robert Redfield, MD, as the next head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Unlike many of President-elect Biden’s nominees, including California Attorney General Xavier Becerra who has been tapped for Secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services, Walensky will not require Senate confirmation, meaning she can hit the ground running on Jan. 20—and she plans to. She’ll be taking over a CDC that has come under fire for caving to political interference and vacillated on guidance and testing guidelines as it struggled to maintain credibility amid the worst public health crisis in a century.

Although Walensky is not an expert in respiratory diseases or coronaviruses her Twitter bio contains some of the most reassuring words Americans in the midst of a pandemic could see: “Decision science researcher.”

“On January. 20, I will begin leading the CDC, which was founded in 1946 to meet precisely the kinds of challenges posed by this pandemic,” she wrote in a New York Times op-ed. “I agreed to serve as CDC. director because I believe in the agency’s mission and commitment to knowledge, statistics and guidance. I will do so by leading with facts, science and integrity — and being accountable for them, as the CDC. has done since its founding 75 years ago.”

She went on to insist that as CDC Director, “it will be my responsibility to make sure that the public trusts the agency’s guidance and that its staff feels supported.”

When President-elect Biden introduced her, she addressed the challenges facing the US. “The pandemic that brought me here today is one that struck America and the world more than 30 years ago because my medical training happened to coincide with some of the most harrowing years of the HIV/AIDS crisis. As a medical student, I saw firsthand how the virus ravaged bodies and communities. Inside the hospital, I witnessed people lose strength and hope. While outside the hospital, I witnessed those same patients, mostly gay men and members of vulnerable communities, be stigmatized and marginalized by their nation and many of its leaders.

“Now, a new virus is ravaging us. It’s striking hardest, once again, at the most vulnerable, the marginalized, the underserved. I’m honored to work with an administration that understands that leading with science is the only way to deliver breakthroughs, to deliver hope, and to bring our nation back to full strength. To the American people and to each and every one of you at the CDC, I promise to work with you, to harness the power of American science, to fight this virus and prevent unnecessary illness and deaths so that we can all get back to our lives.”

Among the tools she will have that her predecessor did not (for long) are not 1 but 2 vaccines, and possibly more soon. However, in a paper published in Health Affairs in November, Walensky and her co-authors reported on their mathematical simulation of vaccination that showed factors related to implementation “will contribute more to the success of vaccination programs than a vaccine’s efficacy as determined in clinical trials.” The benefits of a vaccine decline substantially, they add, in the event of manufacturing or deployment delays, or greater epidemic severity. Equally important, they note, is the need to address vaccine hesitancy. “Our findings demonstrate the need,” they wrote, “…to redouble efforts to promote public confidence in COVID-19 vaccines, and to encourage continued adherence to other mitigation approaches, even after a vaccine becomes available.”

In a Facebook Live event sponsored by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, where Walensky received her MPH degree, she said there are other “substantial challenges” in distributing a coronavirus vaccine, including the fact that one quarter of Americans don’t have a primary care physician to guide their care.

Her appointment has won praise from health experts around the world not only for her extensive scientific background (BS degree in biochemistry and molecular biology from Washington University and a MD degree from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine) and experience but also for her communication skills. She regularly appears on CNN and has more than 50,000 followers on social media.

She will need those communication skills to undo the knot of suspicion and resistance surrounding the COVID vaccines. The year is young, but since January 1st, the 7-day average of deaths has exceeded 2,500 deaths every day and is continuing to rise. Hospitals are running out of room to care for those patients, and the many others with other needs. In 2019, according to the CDC’s latest data, more than 30 million people in the US had no health insurance; thousands of Americans now struggling financially are swelling those numbers.

Walensky definitely has her tasks cut out for her—and those are just the ones we know about now. But Ashish Jha, MD, MPH, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, who is also a renowned public health researcher, has no doubts about her capability. In December, he tweeted: “Running @CDCgov complicated, especially in a crisis. You need to 1. Communicate with the American people, 2. Run a sprawling organization, 3. Understand, effectively use tools of public health. Lots of people can do one of these. No one I know can do all 3 as well as @RWalensky.”

IHS Publishes COVID-19 Vaccination Plan

COVID-19 infection rates have been nearly 4 times higher among American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) when compared with those of non-Hispanic Whites, and AI/ANs are more than 4 times more likely to be hospitalized with the virus. Some mitigation measures have been harder to maintain in Native American communities. Frequent handwashing is difficult when water is at a premium, and social distancing is not always possible when extended families—including elderly—may be living in a single residence.

So vaccination “remains the most promising intervention,” the Indian Health Service Vaccine Task Force wrote in its COVID-19 Pandemic Vaccine Plan, released in November. The plan details how the IHS health care system will prepare for and distribute a vaccine when one becomes available in the US.

The Vaccine Task Force was established by the IHS Headquarters Incident Command Structure, which was activated in early March to respond to COVID-19. In September, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) began a series of consultations with tribes and urban Indian organizations for input on the plan, which aligns as well with recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

To “ensure that vaccines are effectively delivered throughout Indian Country in ways that make sense for tribal communities,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar says the Trump Administration has given all tribal health programs and urban Indian organizations two ways to receive the vaccine: through the IHS or through the state.

The CDC, along with IHS, states, and tribes, are coordinating the distribution of a vaccine for federal sites, tribal health programs, and Urban Indian Organizations (UIOs). CDC has issued data requirements that all health care facilities must meet for COVID-19 vaccine administration, inventory, and monitoring.

“There are system-wide planning efforts in place to make sure we’re ready to implement vaccination activities as soon as a US Food and Drug Administration authorized or approved vaccine is available,” said IHS Director RADM Michael Weahkee in a press release. The program’s success, he said, depends on “the strong partnership between the federal government, tribes, and urban leaders.”

The list of IHS, tribal health programs, and UIOs facilities that will receive the COVID-19 vaccine from the IHS, broken down by IHS area, is available on the IHS coronavirus website.

COVID-19 infection rates have been nearly 4 times higher among American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) when compared with those of non-Hispanic Whites, and AI/ANs are more than 4 times more likely to be hospitalized with the virus. Some mitigation measures have been harder to maintain in Native American communities. Frequent handwashing is difficult when water is at a premium, and social distancing is not always possible when extended families—including elderly—may be living in a single residence.

So vaccination “remains the most promising intervention,” the Indian Health Service Vaccine Task Force wrote in its COVID-19 Pandemic Vaccine Plan, released in November. The plan details how the IHS health care system will prepare for and distribute a vaccine when one becomes available in the US.

The Vaccine Task Force was established by the IHS Headquarters Incident Command Structure, which was activated in early March to respond to COVID-19. In September, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) began a series of consultations with tribes and urban Indian organizations for input on the plan, which aligns as well with recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

To “ensure that vaccines are effectively delivered throughout Indian Country in ways that make sense for tribal communities,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar says the Trump Administration has given all tribal health programs and urban Indian organizations two ways to receive the vaccine: through the IHS or through the state.

The CDC, along with IHS, states, and tribes, are coordinating the distribution of a vaccine for federal sites, tribal health programs, and Urban Indian Organizations (UIOs). CDC has issued data requirements that all health care facilities must meet for COVID-19 vaccine administration, inventory, and monitoring.

“There are system-wide planning efforts in place to make sure we’re ready to implement vaccination activities as soon as a US Food and Drug Administration authorized or approved vaccine is available,” said IHS Director RADM Michael Weahkee in a press release. The program’s success, he said, depends on “the strong partnership between the federal government, tribes, and urban leaders.”

The list of IHS, tribal health programs, and UIOs facilities that will receive the COVID-19 vaccine from the IHS, broken down by IHS area, is available on the IHS coronavirus website.

COVID-19 infection rates have been nearly 4 times higher among American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) when compared with those of non-Hispanic Whites, and AI/ANs are more than 4 times more likely to be hospitalized with the virus. Some mitigation measures have been harder to maintain in Native American communities. Frequent handwashing is difficult when water is at a premium, and social distancing is not always possible when extended families—including elderly—may be living in a single residence.

So vaccination “remains the most promising intervention,” the Indian Health Service Vaccine Task Force wrote in its COVID-19 Pandemic Vaccine Plan, released in November. The plan details how the IHS health care system will prepare for and distribute a vaccine when one becomes available in the US.

The Vaccine Task Force was established by the IHS Headquarters Incident Command Structure, which was activated in early March to respond to COVID-19. In September, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) began a series of consultations with tribes and urban Indian organizations for input on the plan, which aligns as well with recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

To “ensure that vaccines are effectively delivered throughout Indian Country in ways that make sense for tribal communities,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar says the Trump Administration has given all tribal health programs and urban Indian organizations two ways to receive the vaccine: through the IHS or through the state.

The CDC, along with IHS, states, and tribes, are coordinating the distribution of a vaccine for federal sites, tribal health programs, and Urban Indian Organizations (UIOs). CDC has issued data requirements that all health care facilities must meet for COVID-19 vaccine administration, inventory, and monitoring.

“There are system-wide planning efforts in place to make sure we’re ready to implement vaccination activities as soon as a US Food and Drug Administration authorized or approved vaccine is available,” said IHS Director RADM Michael Weahkee in a press release. The program’s success, he said, depends on “the strong partnership between the federal government, tribes, and urban leaders.”

The list of IHS, tribal health programs, and UIOs facilities that will receive the COVID-19 vaccine from the IHS, broken down by IHS area, is available on the IHS coronavirus website.

HCPs and COVID-19 Risk: Safer at Home or at Work?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Michigan Department of Health and Human Services surveyed health care personnel in 27 hospitals and 7 medical control agencies that coordinate emergency medical services in the Detroit metropolitan area. Of 16,397 participants, 6.9% had COVID-19 antibodies (although only 2.7% reported a history of a positive real-time transcription polymerase chain reaction test); however, participants had about 6 times the odds of exposure to the virus at home when compared with the workplace. Of those who reported close contact (within 6 feet) of a person with confirmed COVID-19 for ≥ 10 minutes, seroprevalence was highest among those with exposure to a household member (34.3%).

The survey revealed a pattern that suggested community acquisition was a common underlying factor of infection risk, the researchers say. Workers were only more vulnerable at home and when they were closer to the metropolitan center. Seropositivity was more common within 9 miles of Detroit’s center, regardless of occupation and health care setting. The farther away from the center, the lower the seroprevalence.

By work location, seroprevalence was highest among participants who worked in hospital wards (8.8%) and lowest among those in police departments (3.9%). In hospitals, participants working in wards and EDs had higher seropositivity (8.8% and 8.1%, respectively) than did those in ICUs and ORs (6.1% and 4.5%, respectively). Nurses and nurse assistants were more likely to be seropositive than physicians. Nurse assistants had the highest incidence, regardless of where they worked.

Reducing community spread through population-based measures may directly protect healthcare workers on 2 fronts, the researchers say: reduced occupational exposure as a result of fewer infected patients in the less controlled workplace setting such as the ED, and reduced exposure in their homes and communities.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Michigan Department of Health and Human Services surveyed health care personnel in 27 hospitals and 7 medical control agencies that coordinate emergency medical services in the Detroit metropolitan area. Of 16,397 participants, 6.9% had COVID-19 antibodies (although only 2.7% reported a history of a positive real-time transcription polymerase chain reaction test); however, participants had about 6 times the odds of exposure to the virus at home when compared with the workplace. Of those who reported close contact (within 6 feet) of a person with confirmed COVID-19 for ≥ 10 minutes, seroprevalence was highest among those with exposure to a household member (34.3%).

The survey revealed a pattern that suggested community acquisition was a common underlying factor of infection risk, the researchers say. Workers were only more vulnerable at home and when they were closer to the metropolitan center. Seropositivity was more common within 9 miles of Detroit’s center, regardless of occupation and health care setting. The farther away from the center, the lower the seroprevalence.

By work location, seroprevalence was highest among participants who worked in hospital wards (8.8%) and lowest among those in police departments (3.9%). In hospitals, participants working in wards and EDs had higher seropositivity (8.8% and 8.1%, respectively) than did those in ICUs and ORs (6.1% and 4.5%, respectively). Nurses and nurse assistants were more likely to be seropositive than physicians. Nurse assistants had the highest incidence, regardless of where they worked.

Reducing community spread through population-based measures may directly protect healthcare workers on 2 fronts, the researchers say: reduced occupational exposure as a result of fewer infected patients in the less controlled workplace setting such as the ED, and reduced exposure in their homes and communities.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Michigan Department of Health and Human Services surveyed health care personnel in 27 hospitals and 7 medical control agencies that coordinate emergency medical services in the Detroit metropolitan area. Of 16,397 participants, 6.9% had COVID-19 antibodies (although only 2.7% reported a history of a positive real-time transcription polymerase chain reaction test); however, participants had about 6 times the odds of exposure to the virus at home when compared with the workplace. Of those who reported close contact (within 6 feet) of a person with confirmed COVID-19 for ≥ 10 minutes, seroprevalence was highest among those with exposure to a household member (34.3%).

The survey revealed a pattern that suggested community acquisition was a common underlying factor of infection risk, the researchers say. Workers were only more vulnerable at home and when they were closer to the metropolitan center. Seropositivity was more common within 9 miles of Detroit’s center, regardless of occupation and health care setting. The farther away from the center, the lower the seroprevalence.

By work location, seroprevalence was highest among participants who worked in hospital wards (8.8%) and lowest among those in police departments (3.9%). In hospitals, participants working in wards and EDs had higher seropositivity (8.8% and 8.1%, respectively) than did those in ICUs and ORs (6.1% and 4.5%, respectively). Nurses and nurse assistants were more likely to be seropositive than physicians. Nurse assistants had the highest incidence, regardless of where they worked.

Reducing community spread through population-based measures may directly protect healthcare workers on 2 fronts, the researchers say: reduced occupational exposure as a result of fewer infected patients in the less controlled workplace setting such as the ED, and reduced exposure in their homes and communities.

Matching Wits With a Viral Enemy: How the VA Has Responded to COVID-19

The numbers tell the story:

110,066 veterans diagnosed with COVID-19 as of November 30;

879,457 veterans and employees tested for COVID-19 as of November 6;

14,168 veterans admitted to a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center for COVID-19 care;

1,525% increase in telehealth visits;

59,095 new staff hired to meet surge in demand for COVID-19 care;

75 completed Fourth Mission assignments; and

> 2,000 VA employees helping to support nonveteran patients and non-VA health care systems.

But those numbers are just some of the data in the COVID-19 Response Report, which the VA recently released. The report offers “an extensive look at VA’s complex COVID-19 response,” including how it prepared for the pandemic, the initial response, and key COVID-19 policies and directives.

The report was compiled from more than 90 interviews with health care leaders and stakeholders, along with documents and data pertaining to the Veterans Integrated Service Networks. The interviews were designed to “keep discussion at a strategic level.”

Meeting the crisis mandated that the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) act “with unity of effort and agility,” the authors note, across 18 networks with 170 medical centers. Not only is the VA called on to serve veterans, but its “Fourth Mission” explicitly calls on the VA to “improve the Nation’s preparedness for response to war, terrorism, national emergencies, and natural disasters.” But the VHA possessed some major assets, they add, including a nationwide capacity for inpatient health care, “considerable experience” generating and managing response to regional and local public health emergencies, and strong clinical processes focused on evidence-based guidelines. However, “[w]ithout national analytics of data from outbreaks in other nations, and without a national plan addressing the VHA role, forecasting demand for VHA inpatient services under the Fourth Mission required assumptions with a high degree of uncertainty.”

VHA planners adapted the existing High Consequence Infections Base Plan to COVID-19 and then developed the COVID-19 Response Plan as an annex to that. They released their plan to the public in the interest of a coordinated national response—although not all states were aware of VHA’s important safety-net capabilities. Despite that, the report says, during the pandemic, the mission assignments under the VA’s Fourth Mission have grown to the greatest scale and scope in the VA’s history.

“[H]ealth care in the United States will never be the same,” said Richard Stone, MD, VHA Executive in Charge, in his foreword to the report. Much of what we now consider routine, he said, such as parking lot screenings, digital questionnaires and rapid testing “were revolutionary and challenging to implement” when the pandemic began. “While we are certainly not perfect, we are a learning organization and seek to always find ways to improve.”

Identifying root causes for complex process problems is essential to improvement, the report authors say, and require “new knowledge.” To that end, the VA also has played a critical role in COVID-19–related research, participating in more than 90 and leading 28 multiple-site COVID-19 research studies, including research on 3D-printed respirator masks and convalescent plasma treatment.

The VA’s pandemic response has been “robust and far-reaching,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. The report, he adds, “reflects VA’s agility throughout the pandemic to adapt based on lessons learned.”

The numbers tell the story:

110,066 veterans diagnosed with COVID-19 as of November 30;

879,457 veterans and employees tested for COVID-19 as of November 6;

14,168 veterans admitted to a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center for COVID-19 care;

1,525% increase in telehealth visits;

59,095 new staff hired to meet surge in demand for COVID-19 care;

75 completed Fourth Mission assignments; and

> 2,000 VA employees helping to support nonveteran patients and non-VA health care systems.

But those numbers are just some of the data in the COVID-19 Response Report, which the VA recently released. The report offers “an extensive look at VA’s complex COVID-19 response,” including how it prepared for the pandemic, the initial response, and key COVID-19 policies and directives.

The report was compiled from more than 90 interviews with health care leaders and stakeholders, along with documents and data pertaining to the Veterans Integrated Service Networks. The interviews were designed to “keep discussion at a strategic level.”

Meeting the crisis mandated that the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) act “with unity of effort and agility,” the authors note, across 18 networks with 170 medical centers. Not only is the VA called on to serve veterans, but its “Fourth Mission” explicitly calls on the VA to “improve the Nation’s preparedness for response to war, terrorism, national emergencies, and natural disasters.” But the VHA possessed some major assets, they add, including a nationwide capacity for inpatient health care, “considerable experience” generating and managing response to regional and local public health emergencies, and strong clinical processes focused on evidence-based guidelines. However, “[w]ithout national analytics of data from outbreaks in other nations, and without a national plan addressing the VHA role, forecasting demand for VHA inpatient services under the Fourth Mission required assumptions with a high degree of uncertainty.”

VHA planners adapted the existing High Consequence Infections Base Plan to COVID-19 and then developed the COVID-19 Response Plan as an annex to that. They released their plan to the public in the interest of a coordinated national response—although not all states were aware of VHA’s important safety-net capabilities. Despite that, the report says, during the pandemic, the mission assignments under the VA’s Fourth Mission have grown to the greatest scale and scope in the VA’s history.

“[H]ealth care in the United States will never be the same,” said Richard Stone, MD, VHA Executive in Charge, in his foreword to the report. Much of what we now consider routine, he said, such as parking lot screenings, digital questionnaires and rapid testing “were revolutionary and challenging to implement” when the pandemic began. “While we are certainly not perfect, we are a learning organization and seek to always find ways to improve.”

Identifying root causes for complex process problems is essential to improvement, the report authors say, and require “new knowledge.” To that end, the VA also has played a critical role in COVID-19–related research, participating in more than 90 and leading 28 multiple-site COVID-19 research studies, including research on 3D-printed respirator masks and convalescent plasma treatment.

The VA’s pandemic response has been “robust and far-reaching,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. The report, he adds, “reflects VA’s agility throughout the pandemic to adapt based on lessons learned.”

The numbers tell the story:

110,066 veterans diagnosed with COVID-19 as of November 30;

879,457 veterans and employees tested for COVID-19 as of November 6;

14,168 veterans admitted to a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center for COVID-19 care;

1,525% increase in telehealth visits;

59,095 new staff hired to meet surge in demand for COVID-19 care;

75 completed Fourth Mission assignments; and

> 2,000 VA employees helping to support nonveteran patients and non-VA health care systems.

But those numbers are just some of the data in the COVID-19 Response Report, which the VA recently released. The report offers “an extensive look at VA’s complex COVID-19 response,” including how it prepared for the pandemic, the initial response, and key COVID-19 policies and directives.

The report was compiled from more than 90 interviews with health care leaders and stakeholders, along with documents and data pertaining to the Veterans Integrated Service Networks. The interviews were designed to “keep discussion at a strategic level.”

Meeting the crisis mandated that the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) act “with unity of effort and agility,” the authors note, across 18 networks with 170 medical centers. Not only is the VA called on to serve veterans, but its “Fourth Mission” explicitly calls on the VA to “improve the Nation’s preparedness for response to war, terrorism, national emergencies, and natural disasters.” But the VHA possessed some major assets, they add, including a nationwide capacity for inpatient health care, “considerable experience” generating and managing response to regional and local public health emergencies, and strong clinical processes focused on evidence-based guidelines. However, “[w]ithout national analytics of data from outbreaks in other nations, and without a national plan addressing the VHA role, forecasting demand for VHA inpatient services under the Fourth Mission required assumptions with a high degree of uncertainty.”

VHA planners adapted the existing High Consequence Infections Base Plan to COVID-19 and then developed the COVID-19 Response Plan as an annex to that. They released their plan to the public in the interest of a coordinated national response—although not all states were aware of VHA’s important safety-net capabilities. Despite that, the report says, during the pandemic, the mission assignments under the VA’s Fourth Mission have grown to the greatest scale and scope in the VA’s history.

“[H]ealth care in the United States will never be the same,” said Richard Stone, MD, VHA Executive in Charge, in his foreword to the report. Much of what we now consider routine, he said, such as parking lot screenings, digital questionnaires and rapid testing “were revolutionary and challenging to implement” when the pandemic began. “While we are certainly not perfect, we are a learning organization and seek to always find ways to improve.”

Identifying root causes for complex process problems is essential to improvement, the report authors say, and require “new knowledge.” To that end, the VA also has played a critical role in COVID-19–related research, participating in more than 90 and leading 28 multiple-site COVID-19 research studies, including research on 3D-printed respirator masks and convalescent plasma treatment.

The VA’s pandemic response has been “robust and far-reaching,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. The report, he adds, “reflects VA’s agility throughout the pandemic to adapt based on lessons learned.”

Postpartum Depression Recommendations: Screen More Women and Lengthen the Screening Period

Clinical practice guidelines advise screening women for perinatal depression twice prenatally and once postpartum, but providers at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) may not be adhering closely to those recommendations. In a multisite cohort study, the researchers enrolled women veterans who were pregnant and delivered newborns between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2019. The researchers combined electronic health record and claims data with information collected from prenatal and postpartum telephone surveys.

Of the 663 women involved, 93% received primary care at a VA facility during pregnancy; 41% saw a VA mental health provider. Less than half of the sample had been screened for depression during the perinatal period, despite contact with VA providers. Only 13% of the women had both prenatal and postnatal screens.

Screened veterans were less likely to be diagnosed with depression by a VA provider in either the preconception or pregnancy periods, compared with those not screened (11% vs 24% and 14% vs 23%, respectively).

Among unscreened women, 18% scored positive for depression prenatally and 9% postnatally on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale. The researchers note that lack of screening can hinder connection to VA mental health treatment and referral resources.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that pediatricians screen mothers for postpartum depression at 1, 2, 4, and 6 months after childbirth. But extending that into toddlerhood could pick up more women at risk, say National Institutes of Health researchers. “[S]ix months may not be long enough to gauge depressive symptoms,” said Diane Putnick, PhD, primary author.

In their study of 4,866 women, the researchers analyzed data from the Upstate KIDS study, which included babies born between 2008 and 2010 in New York State. The researchers found that approximately 1 in 4 women experienced high levels of depressive symptoms at some point during the 3 postnatal years.

In addition to extending the screening period to 36 months, the researchers advise keeping watch on women with underlying conditions, such as mood disorders and/or gestational diabetes, who were more likely to have higher levels of depressive symptoms that persisted.

Clinical practice guidelines advise screening women for perinatal depression twice prenatally and once postpartum, but providers at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) may not be adhering closely to those recommendations. In a multisite cohort study, the researchers enrolled women veterans who were pregnant and delivered newborns between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2019. The researchers combined electronic health record and claims data with information collected from prenatal and postpartum telephone surveys.

Of the 663 women involved, 93% received primary care at a VA facility during pregnancy; 41% saw a VA mental health provider. Less than half of the sample had been screened for depression during the perinatal period, despite contact with VA providers. Only 13% of the women had both prenatal and postnatal screens.

Screened veterans were less likely to be diagnosed with depression by a VA provider in either the preconception or pregnancy periods, compared with those not screened (11% vs 24% and 14% vs 23%, respectively).

Among unscreened women, 18% scored positive for depression prenatally and 9% postnatally on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale. The researchers note that lack of screening can hinder connection to VA mental health treatment and referral resources.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that pediatricians screen mothers for postpartum depression at 1, 2, 4, and 6 months after childbirth. But extending that into toddlerhood could pick up more women at risk, say National Institutes of Health researchers. “[S]ix months may not be long enough to gauge depressive symptoms,” said Diane Putnick, PhD, primary author.

In their study of 4,866 women, the researchers analyzed data from the Upstate KIDS study, which included babies born between 2008 and 2010 in New York State. The researchers found that approximately 1 in 4 women experienced high levels of depressive symptoms at some point during the 3 postnatal years.

In addition to extending the screening period to 36 months, the researchers advise keeping watch on women with underlying conditions, such as mood disorders and/or gestational diabetes, who were more likely to have higher levels of depressive symptoms that persisted.

Clinical practice guidelines advise screening women for perinatal depression twice prenatally and once postpartum, but providers at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) may not be adhering closely to those recommendations. In a multisite cohort study, the researchers enrolled women veterans who were pregnant and delivered newborns between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2019. The researchers combined electronic health record and claims data with information collected from prenatal and postpartum telephone surveys.

Of the 663 women involved, 93% received primary care at a VA facility during pregnancy; 41% saw a VA mental health provider. Less than half of the sample had been screened for depression during the perinatal period, despite contact with VA providers. Only 13% of the women had both prenatal and postnatal screens.

Screened veterans were less likely to be diagnosed with depression by a VA provider in either the preconception or pregnancy periods, compared with those not screened (11% vs 24% and 14% vs 23%, respectively).

Among unscreened women, 18% scored positive for depression prenatally and 9% postnatally on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale. The researchers note that lack of screening can hinder connection to VA mental health treatment and referral resources.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that pediatricians screen mothers for postpartum depression at 1, 2, 4, and 6 months after childbirth. But extending that into toddlerhood could pick up more women at risk, say National Institutes of Health researchers. “[S]ix months may not be long enough to gauge depressive symptoms,” said Diane Putnick, PhD, primary author.

In their study of 4,866 women, the researchers analyzed data from the Upstate KIDS study, which included babies born between 2008 and 2010 in New York State. The researchers found that approximately 1 in 4 women experienced high levels of depressive symptoms at some point during the 3 postnatal years.

In addition to extending the screening period to 36 months, the researchers advise keeping watch on women with underlying conditions, such as mood disorders and/or gestational diabetes, who were more likely to have higher levels of depressive symptoms that persisted.

Electronic Reminders Extend the Reach of Health Care

Many health care providers (HCPs) view the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system of electronic reminders as a model. User experience and improvements that make clinical life easier (like automated text messaging, which requires no hands-on staff involvement) have brought more HCPs into the fold. And during a viral pandemic, preventive care is ever more important, as are the ways to provide it. But a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study shows some non-VA providers have some catching up to do.

Although the CDC researchers noted that electronic reminders can improve preventive and follow-up care, they also pointed out that HCPs must first have the computing capabilities to accomplish this. They analyzed 2017 data (the most recent available) from the National Electronic Health Records Survey of > 10,000 physicians and found only 65% of office-based physicians did.

Not surprisingly, practices that used electronic health record (EHR) systems were more than 3 times as likely to also have computerized capability to identify patients who needed preventive care or follow-up (71% vs 23% of practices without EHR). Primary care physicians were more likely than surgeons and other nonprimary care physicians to have the capability (73% vs 55% and 59%, respectively). Age also entered into it, with 70% of physicians aged between 45 and 54 years having the capability, compared with 57% of those aged 65 to 84 years. Offices with multiple physicians were more likely to have computerized capability.

The VA began using computerized clinical reminders 20 years ago to encourage patients to take better care of themselves to, for example, moderate alcohol use, manage cholesterol, or stop smoking. In 2006, the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) won an Innovations in American Government Award from Harvard University. The committee called VistA innovative because of its “unique linkage with standardized, consistent performance measurement.” VistA, the committee said, “substantially improves efficiency, reduces costs and demonstrably improves clinical decision-making.”

However, when the VA was getting its electronic reminder system up to speed, not all users were comfortable with it. Researchers who studied uptake of a system that sent reminders about lipid management to patients with ischemic heart disease found “substantial barriers” to implementation, including a possibly significant effect of “prior culture and attitudes” toward reminders.

Four years after the VA began using computerized reminders, attendees at “Camp CPRS,” a week-long meeting to train employees in the Computerized Patient Record System, were asked about facilitation and barriers. More than half of respondents could report at least 1 situation in which reminders helped them deliver care more effectively. But “[w]hile the potential benefits of such a system are significant,” the researchers said, “and in fact some VA hospitals are showing an increase in compliance with some best practices…it is generally understood that some providers within the VA do not use the clinical reminders.” Some HCPs said they were hard to use and cited insufficient training.

Experience and consistent use pay off, though. For instance, researchers from the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Washington evaluated the effectiveness of an electronic clinical reminder for brief alcohol counseling at 8 VA sites. They wanted to determine how often the HCPs used the reminder, and whether it helped patients resolve unhealthy alcohol use. The study, involving 4,198 participants who screened positive for alcohol use, found 71% of the patients had the clinical reminder documented in the EHR—a high rate, the researchers noted, relative to other studies. The results were similar across the 2-year period, even in the first 8 months.

Sustainability also is a factor. At the time of their study, the researchers said, no health care system had achieved sustained implementation of brief alcohol counseling for patients who screened positive. Moreover, the patients who had reminders were significantly more likely to report having resolved unhealthy alcohol use at follow-up.

Do electronic daily reminders really improve adherence? Valentin Rivish, DNP, RN, NE-BC, telehealth specialist and facility e-consult coordinator with the Phoenix VA Health Care System in Arizona, wanted to see what evidence exists on telehealth adherence and utilization. He enlisted 40 veterans whose home-telehealth response rates were < 70%. Over 4 weeks, the veterans received an electronic daily reminder sent to their home-telehealth device, with the goal of having them respond daily.

As Rivish expected, daily reminders did improve adherence. After 4 weeks, 24 participants (60%) showed an increased response rate, and 14 (35%) achieved at least a 70% response rate pos-intervention. As a result, the Phoenix telehealth department has included the cost-effective intervention in its standard operating procedure.

The VA has continued to add to its repertoire of ways to stay in touch with patients. In 2018, for instance, it launched VEText, a text messaging appointment-reminder system. According to the Veterans Health Administration Office of Veterans Access to Care, in just the first few months more than 3.24 million patients had received VEText messages (and had canceled 319,504 appointments, freeing up time slots for other veterans).

This year, the VA, US Department of Defense, and US Coast Guard launched a joint health information exchange (HIE) that allows partners to quickly and securely share EHR data bidirectionally with participating community healthcare providers. To that end, the 46,000-member HIE is collaborating with the CommonWell Health Alliance, adding a nationwide network of more than 15,000 hospitals and clinics.

“As a clinician who is using the joint HIE, the more patient information I have access to, the more I can understand the full picture of my patients’ care and better meet their needs,” says Dr. Neil Evans, a VA primary care physician and clinical leader with the Federal Electronic Health Record Modernization office. “During the COVID-19 pandemic, efficient electronic health information is more important than ever.”

Many health care providers (HCPs) view the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system of electronic reminders as a model. User experience and improvements that make clinical life easier (like automated text messaging, which requires no hands-on staff involvement) have brought more HCPs into the fold. And during a viral pandemic, preventive care is ever more important, as are the ways to provide it. But a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study shows some non-VA providers have some catching up to do.

Although the CDC researchers noted that electronic reminders can improve preventive and follow-up care, they also pointed out that HCPs must first have the computing capabilities to accomplish this. They analyzed 2017 data (the most recent available) from the National Electronic Health Records Survey of > 10,000 physicians and found only 65% of office-based physicians did.

Not surprisingly, practices that used electronic health record (EHR) systems were more than 3 times as likely to also have computerized capability to identify patients who needed preventive care or follow-up (71% vs 23% of practices without EHR). Primary care physicians were more likely than surgeons and other nonprimary care physicians to have the capability (73% vs 55% and 59%, respectively). Age also entered into it, with 70% of physicians aged between 45 and 54 years having the capability, compared with 57% of those aged 65 to 84 years. Offices with multiple physicians were more likely to have computerized capability.

The VA began using computerized clinical reminders 20 years ago to encourage patients to take better care of themselves to, for example, moderate alcohol use, manage cholesterol, or stop smoking. In 2006, the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) won an Innovations in American Government Award from Harvard University. The committee called VistA innovative because of its “unique linkage with standardized, consistent performance measurement.” VistA, the committee said, “substantially improves efficiency, reduces costs and demonstrably improves clinical decision-making.”

However, when the VA was getting its electronic reminder system up to speed, not all users were comfortable with it. Researchers who studied uptake of a system that sent reminders about lipid management to patients with ischemic heart disease found “substantial barriers” to implementation, including a possibly significant effect of “prior culture and attitudes” toward reminders.

Four years after the VA began using computerized reminders, attendees at “Camp CPRS,” a week-long meeting to train employees in the Computerized Patient Record System, were asked about facilitation and barriers. More than half of respondents could report at least 1 situation in which reminders helped them deliver care more effectively. But “[w]hile the potential benefits of such a system are significant,” the researchers said, “and in fact some VA hospitals are showing an increase in compliance with some best practices…it is generally understood that some providers within the VA do not use the clinical reminders.” Some HCPs said they were hard to use and cited insufficient training.

Experience and consistent use pay off, though. For instance, researchers from the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Washington evaluated the effectiveness of an electronic clinical reminder for brief alcohol counseling at 8 VA sites. They wanted to determine how often the HCPs used the reminder, and whether it helped patients resolve unhealthy alcohol use. The study, involving 4,198 participants who screened positive for alcohol use, found 71% of the patients had the clinical reminder documented in the EHR—a high rate, the researchers noted, relative to other studies. The results were similar across the 2-year period, even in the first 8 months.

Sustainability also is a factor. At the time of their study, the researchers said, no health care system had achieved sustained implementation of brief alcohol counseling for patients who screened positive. Moreover, the patients who had reminders were significantly more likely to report having resolved unhealthy alcohol use at follow-up.

Do electronic daily reminders really improve adherence? Valentin Rivish, DNP, RN, NE-BC, telehealth specialist and facility e-consult coordinator with the Phoenix VA Health Care System in Arizona, wanted to see what evidence exists on telehealth adherence and utilization. He enlisted 40 veterans whose home-telehealth response rates were < 70%. Over 4 weeks, the veterans received an electronic daily reminder sent to their home-telehealth device, with the goal of having them respond daily.

As Rivish expected, daily reminders did improve adherence. After 4 weeks, 24 participants (60%) showed an increased response rate, and 14 (35%) achieved at least a 70% response rate pos-intervention. As a result, the Phoenix telehealth department has included the cost-effective intervention in its standard operating procedure.

The VA has continued to add to its repertoire of ways to stay in touch with patients. In 2018, for instance, it launched VEText, a text messaging appointment-reminder system. According to the Veterans Health Administration Office of Veterans Access to Care, in just the first few months more than 3.24 million patients had received VEText messages (and had canceled 319,504 appointments, freeing up time slots for other veterans).

This year, the VA, US Department of Defense, and US Coast Guard launched a joint health information exchange (HIE) that allows partners to quickly and securely share EHR data bidirectionally with participating community healthcare providers. To that end, the 46,000-member HIE is collaborating with the CommonWell Health Alliance, adding a nationwide network of more than 15,000 hospitals and clinics.

“As a clinician who is using the joint HIE, the more patient information I have access to, the more I can understand the full picture of my patients’ care and better meet their needs,” says Dr. Neil Evans, a VA primary care physician and clinical leader with the Federal Electronic Health Record Modernization office. “During the COVID-19 pandemic, efficient electronic health information is more important than ever.”

Many health care providers (HCPs) view the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system of electronic reminders as a model. User experience and improvements that make clinical life easier (like automated text messaging, which requires no hands-on staff involvement) have brought more HCPs into the fold. And during a viral pandemic, preventive care is ever more important, as are the ways to provide it. But a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study shows some non-VA providers have some catching up to do.

Although the CDC researchers noted that electronic reminders can improve preventive and follow-up care, they also pointed out that HCPs must first have the computing capabilities to accomplish this. They analyzed 2017 data (the most recent available) from the National Electronic Health Records Survey of > 10,000 physicians and found only 65% of office-based physicians did.

Not surprisingly, practices that used electronic health record (EHR) systems were more than 3 times as likely to also have computerized capability to identify patients who needed preventive care or follow-up (71% vs 23% of practices without EHR). Primary care physicians were more likely than surgeons and other nonprimary care physicians to have the capability (73% vs 55% and 59%, respectively). Age also entered into it, with 70% of physicians aged between 45 and 54 years having the capability, compared with 57% of those aged 65 to 84 years. Offices with multiple physicians were more likely to have computerized capability.

The VA began using computerized clinical reminders 20 years ago to encourage patients to take better care of themselves to, for example, moderate alcohol use, manage cholesterol, or stop smoking. In 2006, the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) won an Innovations in American Government Award from Harvard University. The committee called VistA innovative because of its “unique linkage with standardized, consistent performance measurement.” VistA, the committee said, “substantially improves efficiency, reduces costs and demonstrably improves clinical decision-making.”

However, when the VA was getting its electronic reminder system up to speed, not all users were comfortable with it. Researchers who studied uptake of a system that sent reminders about lipid management to patients with ischemic heart disease found “substantial barriers” to implementation, including a possibly significant effect of “prior culture and attitudes” toward reminders.

Four years after the VA began using computerized reminders, attendees at “Camp CPRS,” a week-long meeting to train employees in the Computerized Patient Record System, were asked about facilitation and barriers. More than half of respondents could report at least 1 situation in which reminders helped them deliver care more effectively. But “[w]hile the potential benefits of such a system are significant,” the researchers said, “and in fact some VA hospitals are showing an increase in compliance with some best practices…it is generally understood that some providers within the VA do not use the clinical reminders.” Some HCPs said they were hard to use and cited insufficient training.

Experience and consistent use pay off, though. For instance, researchers from the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Washington evaluated the effectiveness of an electronic clinical reminder for brief alcohol counseling at 8 VA sites. They wanted to determine how often the HCPs used the reminder, and whether it helped patients resolve unhealthy alcohol use. The study, involving 4,198 participants who screened positive for alcohol use, found 71% of the patients had the clinical reminder documented in the EHR—a high rate, the researchers noted, relative to other studies. The results were similar across the 2-year period, even in the first 8 months.

Sustainability also is a factor. At the time of their study, the researchers said, no health care system had achieved sustained implementation of brief alcohol counseling for patients who screened positive. Moreover, the patients who had reminders were significantly more likely to report having resolved unhealthy alcohol use at follow-up.

Do electronic daily reminders really improve adherence? Valentin Rivish, DNP, RN, NE-BC, telehealth specialist and facility e-consult coordinator with the Phoenix VA Health Care System in Arizona, wanted to see what evidence exists on telehealth adherence and utilization. He enlisted 40 veterans whose home-telehealth response rates were < 70%. Over 4 weeks, the veterans received an electronic daily reminder sent to their home-telehealth device, with the goal of having them respond daily.

As Rivish expected, daily reminders did improve adherence. After 4 weeks, 24 participants (60%) showed an increased response rate, and 14 (35%) achieved at least a 70% response rate pos-intervention. As a result, the Phoenix telehealth department has included the cost-effective intervention in its standard operating procedure.

The VA has continued to add to its repertoire of ways to stay in touch with patients. In 2018, for instance, it launched VEText, a text messaging appointment-reminder system. According to the Veterans Health Administration Office of Veterans Access to Care, in just the first few months more than 3.24 million patients had received VEText messages (and had canceled 319,504 appointments, freeing up time slots for other veterans).

This year, the VA, US Department of Defense, and US Coast Guard launched a joint health information exchange (HIE) that allows partners to quickly and securely share EHR data bidirectionally with participating community healthcare providers. To that end, the 46,000-member HIE is collaborating with the CommonWell Health Alliance, adding a nationwide network of more than 15,000 hospitals and clinics.

“As a clinician who is using the joint HIE, the more patient information I have access to, the more I can understand the full picture of my patients’ care and better meet their needs,” says Dr. Neil Evans, a VA primary care physician and clinical leader with the Federal Electronic Health Record Modernization office. “During the COVID-19 pandemic, efficient electronic health information is more important than ever.”

The Cell’s Waste Disposal System May be Key to Killing Coronavirus

Normally, the lysosome, known as the cells’ “trash compactor,” destroys viruses before they can leave the cell. However, researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have discovered that SARS-CoV-2 is not like other viruses. The virus can deactivate that waste disposal system, exit without hindrance, and spread freely throughout the body.

“To our shock, these coronaviruses got out of the cells just fine,” said Nihal Altan-Bonnet, PhD, chief of the Laboratory of Host-Pathogen Dynamics at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, who coauthored the study report.

Most viruses exit via the biosynthetic secretory pathway, used to transport hormones, growth factors and other materials. The researchers wanted to learn whether coronaviruses took an alternate route. To find out, they conducted further studies, using microscopy and virus-specific markers. They discovered that coronaviruses somehow target the lysosome and congregate there. Although lysosomes are highly acidic, the coronaviruses were not destroyed.

That question led to more experiments. The researchers next found that lysosomes get “de-acidified” in coronavirus-infected cells, which weakens their destructive enzymes. The result: The coronavirus remains intact, ready to infect other cells upon exiting.

The coronaviruses are “very sneaky,” Altan-Bonnet says. “They’re using these lysosomes to get out, but they’re also disrupting the lysosome so it can’t do its job or function.” It’s possible that the way the coronavirus interferes with the lysosome’s “immunological machinery” underlies some of the immune system abnormalities seen in COVID-19 patients, such as cytokine storms.

Studying this coronavirus's heterodox ways may mean that researchers can figure out how to keep it from getting out unscathed, or restore the lysosome’s killing ability by re-acidifying it. Altan-Bonnet and coauthor Sourish Ghosh, PhD, say they have already identified one experimental enzyme inhibitor that potently blocks coronaviruses from exiting the cell.

The lysosome pathway, Altan-Bonnet says, “offers a whole different way of thinking about targeted therapeutics.”

Normally, the lysosome, known as the cells’ “trash compactor,” destroys viruses before they can leave the cell. However, researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have discovered that SARS-CoV-2 is not like other viruses. The virus can deactivate that waste disposal system, exit without hindrance, and spread freely throughout the body.

“To our shock, these coronaviruses got out of the cells just fine,” said Nihal Altan-Bonnet, PhD, chief of the Laboratory of Host-Pathogen Dynamics at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, who coauthored the study report.

Most viruses exit via the biosynthetic secretory pathway, used to transport hormones, growth factors and other materials. The researchers wanted to learn whether coronaviruses took an alternate route. To find out, they conducted further studies, using microscopy and virus-specific markers. They discovered that coronaviruses somehow target the lysosome and congregate there. Although lysosomes are highly acidic, the coronaviruses were not destroyed.

That question led to more experiments. The researchers next found that lysosomes get “de-acidified” in coronavirus-infected cells, which weakens their destructive enzymes. The result: The coronavirus remains intact, ready to infect other cells upon exiting.

The coronaviruses are “very sneaky,” Altan-Bonnet says. “They’re using these lysosomes to get out, but they’re also disrupting the lysosome so it can’t do its job or function.” It’s possible that the way the coronavirus interferes with the lysosome’s “immunological machinery” underlies some of the immune system abnormalities seen in COVID-19 patients, such as cytokine storms.

Studying this coronavirus's heterodox ways may mean that researchers can figure out how to keep it from getting out unscathed, or restore the lysosome’s killing ability by re-acidifying it. Altan-Bonnet and coauthor Sourish Ghosh, PhD, say they have already identified one experimental enzyme inhibitor that potently blocks coronaviruses from exiting the cell.

The lysosome pathway, Altan-Bonnet says, “offers a whole different way of thinking about targeted therapeutics.”

Normally, the lysosome, known as the cells’ “trash compactor,” destroys viruses before they can leave the cell. However, researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have discovered that SARS-CoV-2 is not like other viruses. The virus can deactivate that waste disposal system, exit without hindrance, and spread freely throughout the body.

“To our shock, these coronaviruses got out of the cells just fine,” said Nihal Altan-Bonnet, PhD, chief of the Laboratory of Host-Pathogen Dynamics at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, who coauthored the study report.

Most viruses exit via the biosynthetic secretory pathway, used to transport hormones, growth factors and other materials. The researchers wanted to learn whether coronaviruses took an alternate route. To find out, they conducted further studies, using microscopy and virus-specific markers. They discovered that coronaviruses somehow target the lysosome and congregate there. Although lysosomes are highly acidic, the coronaviruses were not destroyed.

That question led to more experiments. The researchers next found that lysosomes get “de-acidified” in coronavirus-infected cells, which weakens their destructive enzymes. The result: The coronavirus remains intact, ready to infect other cells upon exiting.

The coronaviruses are “very sneaky,” Altan-Bonnet says. “They’re using these lysosomes to get out, but they’re also disrupting the lysosome so it can’t do its job or function.” It’s possible that the way the coronavirus interferes with the lysosome’s “immunological machinery” underlies some of the immune system abnormalities seen in COVID-19 patients, such as cytokine storms.

Studying this coronavirus's heterodox ways may mean that researchers can figure out how to keep it from getting out unscathed, or restore the lysosome’s killing ability by re-acidifying it. Altan-Bonnet and coauthor Sourish Ghosh, PhD, say they have already identified one experimental enzyme inhibitor that potently blocks coronaviruses from exiting the cell.

The lysosome pathway, Altan-Bonnet says, “offers a whole different way of thinking about targeted therapeutics.”

How VA Nurses are Coping With the COVID-19 Pandemic

The tsunami we call COVID-19 has threatened to overwhelm everything in its path, with devastating effects that can be hard to quantify or qualify. But the Nurses Organization of Veterans Affairs (NOVA) has taken on the fight. Earlier this year, NOVA surveyed its members to learn how nurses felt the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was managing personal protective equipment (PPE), testing, communications, staffing needs, and other issues. Following the survey NOVA conducted in-depth interviews with nurses at the VA Boston Healthcare System to better understand how the pandemic was affecting nurses across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

The first survey, which was conducted in March and April 2020, included the following questions:

- Do you feel prepared for COVID-19?

- Do you feel your facility’s supply of PPE is adequate?

- Are you aware of the protocol for the distribution of equipment/supplies at your facility?

- Are staff being tested for the virus, and if so, when, and are there enough test kits available for staff and patients?

- Do you believe your facility is properly handling staff who have been exposed to COVID-19 but are asymptomatic?

With the May survey, NOVA aimed to get an update on how things were progressing. This survey asked how the pandemic was affecting members personally, including questions such as: Do you feel you are being supported—mentally and physically? Has VA offered to provide staff mental health counselors or others to help mitigate stress during the crisis?

Results revealed inconsistencies and some confusion. For example, communication among leadership, staff, and veterans continued to change rapidly, causing some misunderstanding overall, respondents said. Some pointed to “e-mail overload” and weekly updates that didn’t work. Others felt communication was “reactive” and “bare minimum”—not “proactive and informative.”

Most (74%) respondents felt that access to PPE was inadequate, and many did not know the protocol for distribution or what supplies were on hand, while 47% felt ill prepared for any COVID-19 onslaught. Although things had improved somewhat by May, > 85% of the respondents said they were reusing what was provided daily and were still finding it difficult to get PPE when needed.

According to respondents, testing was pretty much nonexistent. When asked whether staff were being tested and whether tests for both staff and patients were available, the answer was a resounding No (80%). Nurses’ comments ranged from “staff are not being tested, even if they have been exposed,” to “there are not enough tests for patients, let alone for frontline staff.”

The lack of tests compounded stress. Helen Motroni, ADN, RN, spinal cord injury staff nurse, said, “I have been tested twice for direct exposure to the coronavirus in the past 3 weeks. Luckily, the results were negative, but waiting for the test results was extremely stressful because I have 2 little boys at home. While waiting for results, I self-quarantined and was terrified that I possibly brought the virus home to my children. I never left my room and would talk with my boys through the door and FaceTime. My 8-year-old asked me why I couldn’t stay home so I would not get sick. I explained to him that if every nurse did that, there would be nobody to help those that are sick and suffering.”

As summer approached, testing throughout most of the states remained scarce and contact tracing was a struggle at many facilities. It seemed that, even if testing was available, only those at high risk would be tested.

Moreover, quarantine and sick leave for those who were COVID positive remained a concern, as numbers of those exposed increased. It was widely known and reported that staffing levels within the VHA were inadequate prior to the months going into the pandemic; survey respondents wondered how they would handle vacancies and take care of outside patients as part of the Fourth Mission if staff got sick. One COVID-compelled solution (which NOVA has advocated for years) included expedited hiring practices. Timely application and quicker onboarding enabled VA to hire within weeks rather than months. Since March, VA has hired > 20,000 new employees.

Multiplied Multitasking

The crisis, along with potential and actual staff shortages, has meant that many nurses have been doing double and triple duty—at the least. Danielle Newman, MSN, RN, clinical resource nurse, specialty and outpatient clinics, said, “Throughout the COVID crisis, I have been a direct care provider, an educator, a member of the float pool, an infection preventionist, a colleague, a therapist, and part of a support system to many.… As a PPE nurse educator, I visit every floor in the hospital and help educate staff on how to properly don and doff PPE, as well as monitor the doffing area and assist staff through the doffing process. I have also been involved in obtaining nasal swabs on veterans as well as staff in order to isolate and slow the progression of the virus.”

Some nurses were deployed, some redeployed, and some volunteered for the COVID front. James Murphy, BSN, RN, an emergency department nurse, answered the call. “During the first few weeks of the outbreak and with all its uncertainty, I volunteered to be a COVID nurse.… Seeing how the pandemic has changed practice was an experience.”