User login

Janus Kinase Inhibitors: A Promising Therapeutic Option for Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction that usually manifests with eczematous lesions within hours to days after exposure to a contact allergen. The primary treatment of ACD consists of allergen avoidance, but medications also may be necessary to manage symptoms, particularly in cases where avoidance alone does not lead to resolution of dermatitis. At present, no medical therapies are explicitly approved for use in the management of ACD. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are a class of small molecule inhibitors that are used for the treatment of a range of inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Several oral and topical JAK inhibitors also have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for atopic dermatitis (AD). In this article, we discuss this important class of medications and the role that they may play in the off-label management of refractory ACD.

JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway

The JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway plays a crucial role in many biologic processes. Notably, JAK/STAT signaling is involved in the development and regulation of the immune system.1 The cascade begins when a particular transmembrane receptor binds a ligand, such as an interferon or interleukin.2 Upon ligand binding, the receptor dimerizes or oligomerizes, bringing the relevant JAK proteins into close approximation to each other.3 This allows the JAK proteins to autophosphorylate or transphosphorylate.2-4 Phosphorylation activates the JAK proteins and increases their kinase activity.3 In humans, there are 4 JAK proteins: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2.4 When activated, the JAK proteins phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues on the receptor, which creates a docking site for STAT proteins. After binding, the STAT proteins then are phosphorylated, leading to their dimerization and translocation to the nucleus.2,3 Once in the nucleus, the STAT proteins act as transcription factors for target genes.3

JAK Inhibitors

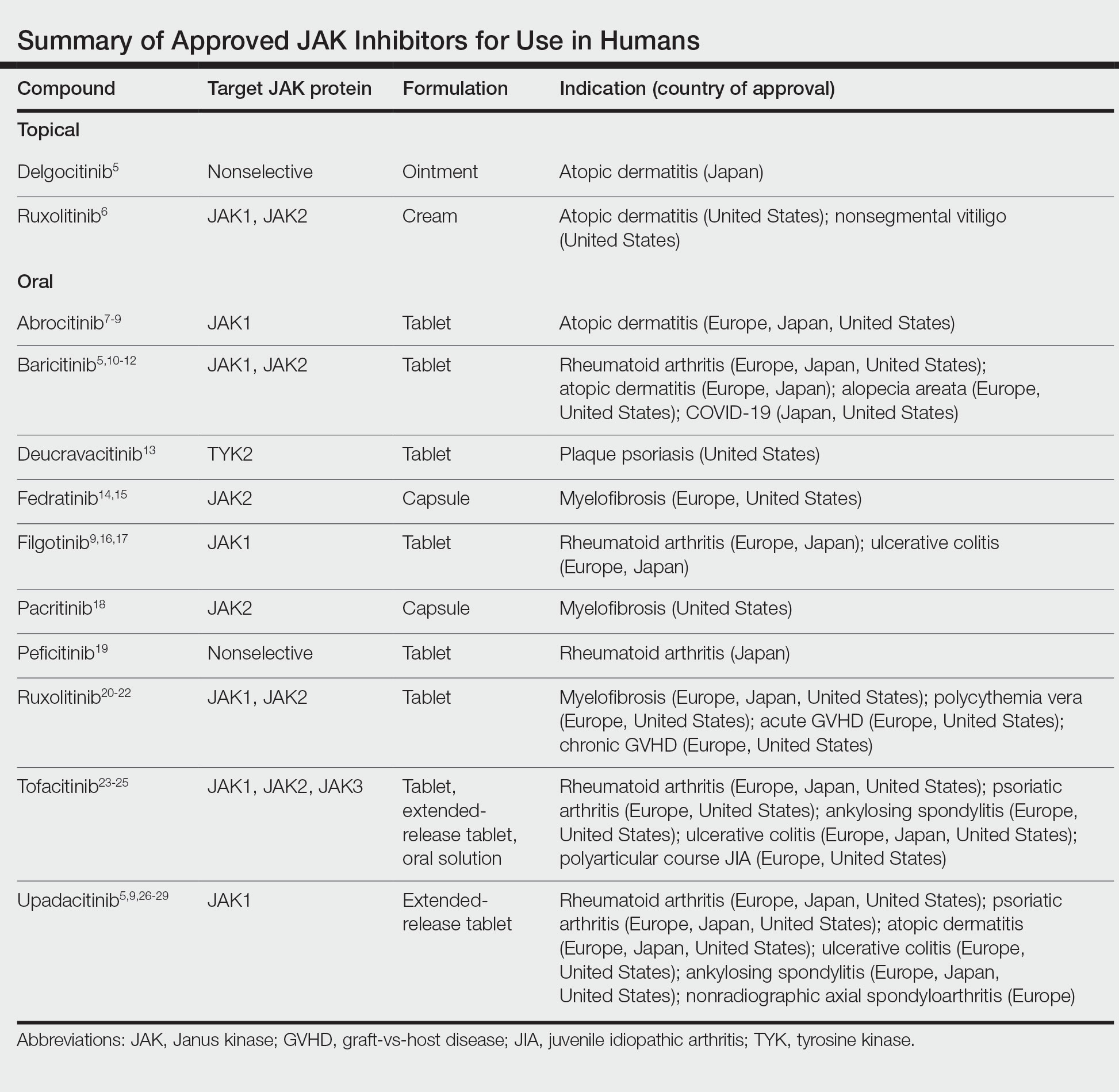

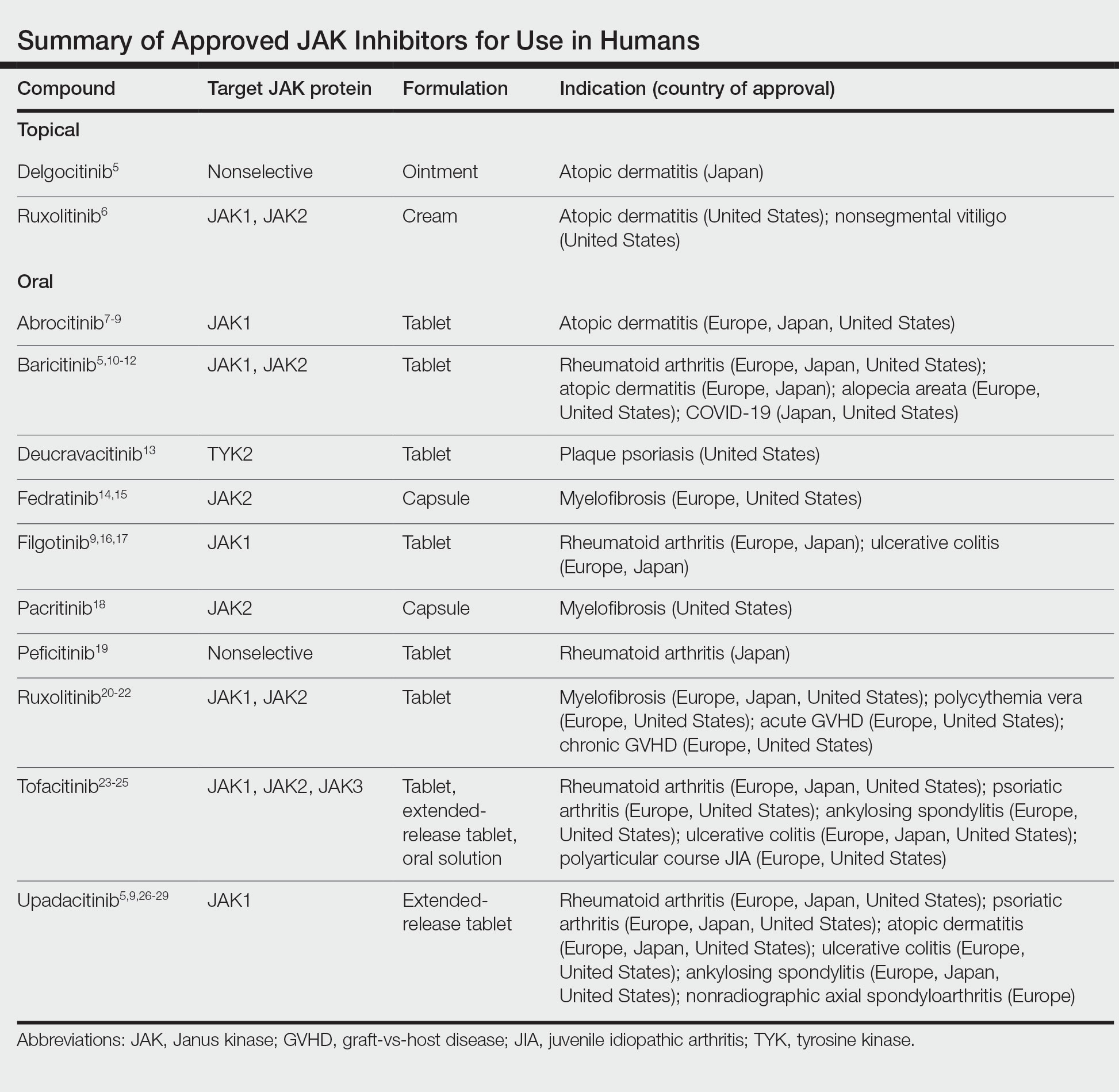

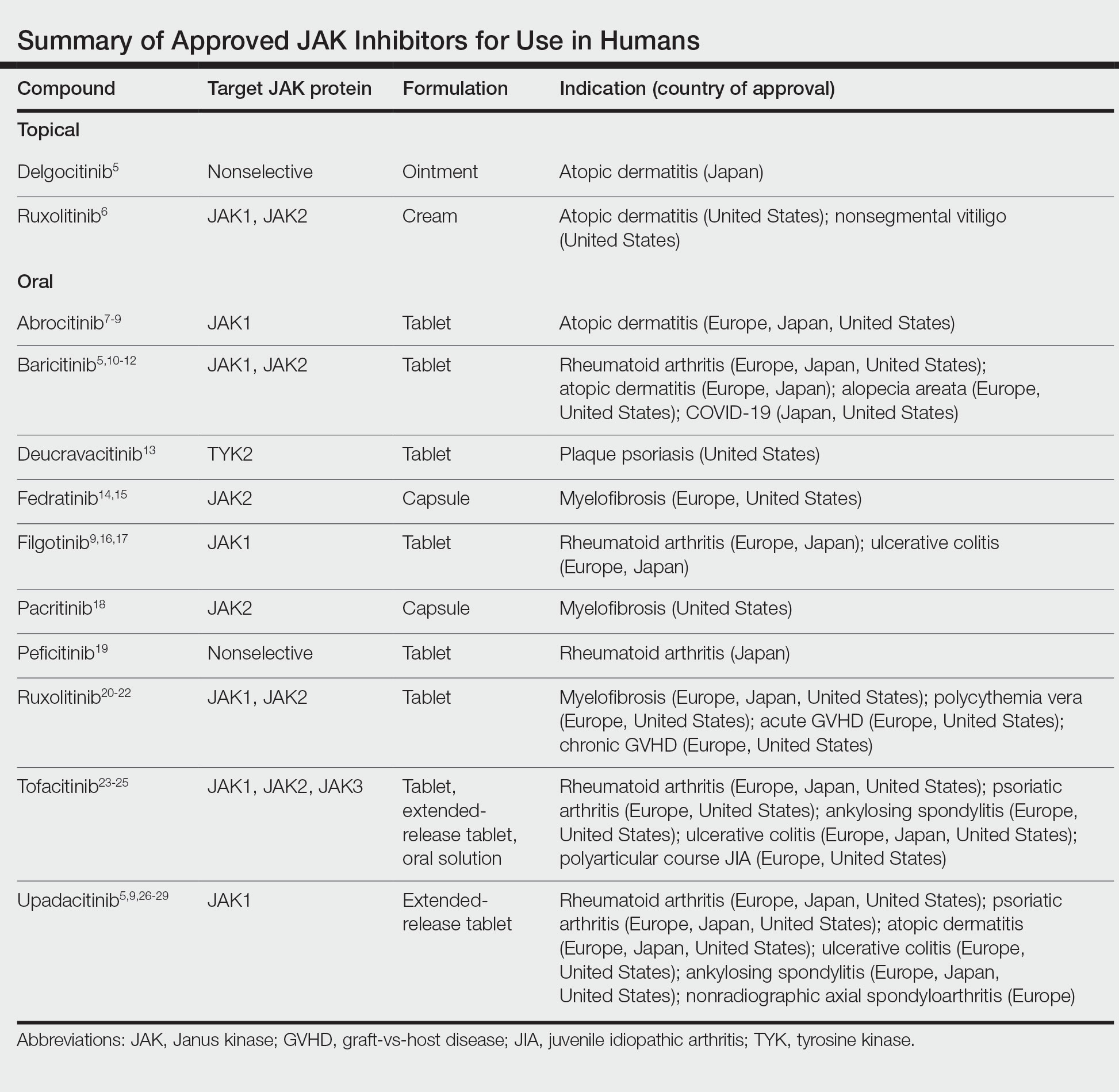

Janus kinase inhibitors are immunomodulatory medications that work through inhibition of 1 or more of the JAK proteins in the JAK/STAT pathway. Through this mechanism, JAK inhibitors can impede the activity of proinflammatory cytokines and T cells.4 A brief overview of the commercially available JAK inhibitors in Europe, Japan, and the United States is provided in the Table.5-29

Of the approved JAK inhibitors, more than 40% are indicated for AD. The first JAK inhibitor to be approved in the topical form was delgocitinib in 2020 in Japan.5 In a phase 3 trial, delgocitinib demonstrated significant reductions in modified Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score (P<.001) as well as Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) when compared with vehicle.30 Topical ruxolitinib soon followed when its approval for AD was announced by the FDA in 2021.31 Results from 2 phase 3 trials found that significantly more patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) treatment success (P<.0001) and a significant reduction in itch as measured by the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) with topical ruxolitinib vs vehicle.32

The first oral JAK inhibitor to attain approval for AD was baricitinib in Europe and Japan, but it is not currently approved for this indication in the United States by the FDA.11,12,33 Consistent findings across phase 3 trials revealed that baricitinib was more effective at achieving IGA treatment success and improved EASI scores compared with placebo.33

Upadacitinib, another oral JAK inhibitor, was subsequently approved for AD in Europe and Japan in 2021 and in the United States in early 2022.5,9,26,27 Two replicate phase 3 trials demonstrated significant improvement in EASI score, itch, and quality of life with upadacitinib compared with placebo (P<.0001).34 Abrocitinib was granted FDA approval for AD in the same time period, with phase 3 trials exhibiting greater responses in IGA and EASI scores vs placebo.35

Potential for Use in ACD

Given the successful use of JAK inhibitors in the management of AD, there is optimism that these medications also may have potential application in ACD. Recent literature suggests that the 2 conditions may be more closely related mechanistically than previously understood. As a result, AD and ACD often are managed with the same therapeutic agents.36

Although the exact etiology of ACD is still being elucidated, activation of T cells and cytokines plays an important role.37 Notably, more than 40 cytokines exert their effects through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, including IL-2, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ.37,38 A study on nickel contact allergy revealed that JAK/STAT activation may regulate the balance between IL-12 and IL-23 and increase type 1 T-helper (TH1) polarization.39 Skin inflammation and chronic pruritus, which are major components of ACD, also are thought to be mediated in part by JAK signaling.34,40

Animal studies have suggested that JAK inhibitors may show benefit in the management of ACD. Rats with oxazolone-induced ACD were found to have less swelling and epidermal thickening in the area of induced dermatitis after treatment with oral tofacitinib, comparable to the effects of cyclosporine. Tofacitinib was presumed to exert its effects through cytokine suppression, particularly that of IFN-γ, IL-22, and tumor necrosis factor α.41 In a separate study on mice with toluene-2,4-diisocyanate–induced ACD, both tofacitinib and another JAK inhibitor, oclacitinib, demonstrated inhibition of cytokine production, migration, and maturation of bone marrow–derived dendritic cells. Both topical and oral formulations of these 2 JAK inhibitors also were found to decrease scratching behavior; only the topicals improved ear thickness (used as a marker of skin inflammation), suggesting potential benefits to local application.42 In a murine model, oral delgocitinib also attenuated contact hypersensitivity via inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell proliferation and cytokine production.37 Finally, in a randomized clinical trial conducted on dogs with allergic dermatitis (of which 10% were presumed to be from contact allergy), oral oclacitinib significantly reduced pruritus and clinical severity scores vs placebo (P<.0001).43

There also are early clinical studies and case reports highlighting the effective use of JAK inhibitors in the management of ACD in humans. A 37-year-old man with occupational airborne ACD to Compositae saw full clearance of his dermatitis with daily oral abrocitinib after topical corticosteroids and dupilumab failed.44 Another patient, a 57-year-old woman, had near-complete resolution of chronic Parthenium-induced airborne ACD after starting twice-daily oral tofacitinib. Allergen avoidance, as well as multiple medications, including topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and azathioprine, previously failed in this patient.45 Finally, a phase 2 study on patients with irritant and nonirritant chronic hand eczema found that significantly more patients achieved treatment success (as measured by the physician global assessment) with topical delgocitinib vs vehicle (P=.009).46 Chronic hand eczema may be due to a variety of causes, including AD, irritant contact dermatitis, and ACD. Thus, these studies begin to highlight the potential role for JAK inhibitors in the management of refractory ACD.

Side Effects of JAK Inhibitors

The safety profile of JAK inhibitors must be taken into consideration. In general, topical JAK inhibitors are safe and well tolerated, with the majority of adverse events (AEs) seen in clinical trials considered mild or unrelated to the medication.30,32 Nasopharyngitis, local skin infection, and acne were reported; a systematic review found no increased risk of AEs with topical JAK inhibitors compared with placebo.30,32,47 Application-site reactions, a common concern among the existing topical calcineurin and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, were rare (approximately 2% of patients).47 The most frequent AEs seen in clinical trials of oral JAK inhibitors included acne, nasopharyngitis/upper respiratory tract infections, nausea, and headache.33-35 Herpes simplex virus infection and worsening of AD also were seen. Although elevations in creatine phosphokinase levels were reported, patients often were asymptomatic and elevations were related to exercise or resolved without treatment interruption.33-35

As a class, JAK inhibitors carry a boxed warning for serious infections, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and mortality. The FDA placed this label on JAK inhibitors because of the results of a randomized controlled trial of oral tofacitinib vs tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors in RA.48,49 Notably, participants in the trial had to be 50 years or older and have at least 1 additional cardiovascular risk factor. Postmarket safety data are still being collected for patients with AD and other dermatologic conditions, but the findings of safety analyses have been reassuring to date.50,51 Regular follow-up and routine laboratory monitoring are recommended for any patient started on an oral JAK inhibitor, which often includes monitoring of the complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipids, as well as baseline screening for tuberculosis and hepatitis.52,53 For topical JAK inhibitors, no specific laboratory monitoring is recommended.

Finally, it must be considered that the challenges of off-label prescribing combined with high costs may limit access to JAK inhibitors for use in ACD.

Final Interpretation

Early investigations, including studies on animals and humans, suggest that JAK inhibitors are a promising option in the management of treatment-refractory ACD. Patients and providers should be aware of both the benefits and known side effects of JAK inhibitors prior to treatment initiation.

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:273-287.

- Bousoik E, Montazeri Aliabadi H. “Do we know Jack” about JAK? a closer look at JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Front Oncol. 2018;8:287.

- Jatiani SS, Baker SJ, Silverman LR, et al. Jak/STAT pathways in cytokine signaling and myeloproliferative disorders: approaches for targeted therapies. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:979-993.

- Seif F, Khoshmirsafa M, Aazami H, et al. The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2017;15:23.

- Traidl S, Freimooser S, Werfel T. Janus kinase inhibitors for the therapy of atopic dermatitis. Allergol Select. 2021;5:293-304.

- Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215309s001lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo (abrocitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/213871s000lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 17, 2021. Updated November 10, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/cibinqo

- New drugs approved in FY 2021. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000246734.pdf

- Olumiant (baricitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/207924s007lbl.pdf

- Olumiant. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 16, 2017. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/olumiant

- Review report: Olumiant. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. April 21, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000243207.pdf

- Sotyktu (deucravacitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/214958s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic (fedratinib) capsules. Prescribing information. Celgene Corporation; 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212327s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 3, 2021. Updated December 8, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/inrebic

- Jyseleca. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published September 28, 2020. Updated November 9, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/jyseleca-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Jyseleca. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. September 8, 2020. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000247830.pdf

- Vonjo (pacritinib) capsules. Prescribing information. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Review report: Smyraf. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. February 28, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000233074.pdf

- Jakafi (ruxolitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/202192s023lbl.pdf

- Jakavi. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published October 4, 2012. Updated May 18, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/jakavi

- New drugs approved in FY 2014. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000229076.pdf

- Xeljanz (tofacitinib). Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/203214s028,208246s013,213082s003lbl.pdf

- Xeljanz. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/xeljanz-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Xeljanz. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000237584.pdf

- Rinvoq (upadacitinib) extended-release tablets. Prescribing information. AbbVie Inc; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/211675s003lbl.pdf

- Rinvoq. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 18, 2019. Updated December 7, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/rinvoq

- New drugs approved in FY 2019. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000235289.pdfs

- New drugs approved in May 2022. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000248626.pdf

- Nakagawa H, Nemoto O, Igarashi A, et al. Delgocitinib ointment, a topical Janus kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study and an open-label, long-term extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:823-831. Erratum appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1069.

- Sideris N, Paschou E, Bakirtzi K, et al. New and upcoming topical treatments for atopic dermatitis: a review of the literature. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4974.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 2 phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:863-872.

- Radi G, Simonetti O, Rizzetto G, et al. Baricitinib: the first Jak inhibitor approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adult patients. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9:1575.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397:2151-2168. Erratum appears in Lancet. 2021;397:2150.

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112.

- Johnson H, Novack DE, Adler BL, et al. Can atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis coexist? Cutis. 2022;110:139-142.

- Amano W, Nakajima S, Yamamoto Y, et al. JAK inhibitor JTE-052 regulates contact hypersensitivity by downmodulating T cell activation and differentiation. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84:258-265.

- O’Shea JJ, Schwartz DM, Villarino AV, et al. The JAK-STAT pathway: impact on human disease and therapeutic intervention. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:311-328.

- Bechara R, Antonios D, Azouri H, et al. Nickel sulfate promotes IL-17A producing CD4+ T cells by an IL-23-dependent mechanism regulated by TLR4 and JAK-STAT pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2140-2148.

- Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J, et al. Sensory neurons co-opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell. 2017;171:217-228.e13.

- Fujii Y, Sengoku T. Effects of the Janus kinase inhibitor CP-690550 (tofacitinib) in a rat model of oxazolone-induced chronic dermatitis. Pharmacology. 2013;91:207-213.

- Fukuyama T, Ehling S, Cook E, et al. Topically administered Janus-kinase inhibitors tofacitinib and oclacitinib display impressive antipruritic and anti-inflammatory responses in a model of allergic dermatitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;354:394-405.

- Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, et al. Efficacy and safety of oclacitinib for the control of pruritus and associated skin lesions in dogs with canine allergic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24:479, E114.

- Baltazar D, Shinamoto SR, Hamann CP, et al. Occupational airborne allergic contact dermatitis to invasive Compositae species treated with abrocitinib: a case report. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:542-544.

- Muddebihal A, Sardana K, Sinha S, et al. Tofacitinib in refractory Parthenium-induced airborne allergic contact dermatitis [published online October 12, 2022]. Contact Dermatitis. doi:10.1111/cod.14234

- Worm M, Bauer A, Elsner P, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical delgocitinib in patients with chronic hand eczema: data from a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase IIa study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1103-1110.

- Chen J, Cheng J, Yang H, et al. The efficacy and safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:495-496.

- Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires warnings about increased risk of serious heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death for JAK inhibitors that treat certain chronic inflammatory conditions. Updated December 7, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-warnings-about-increased-risk-serious-heart-related-events-cancer-blood-clots-and-death

- Chen TL, Lee LL, Huang HK, et al. Association of risk of incident venous thromboembolism with atopic dermatitis and treatment with Janus kinase inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1254-1261.

- King B, Maari C, Lain E, et al. Extended safety analysis of baricitinib 2 mg in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: an integrated analysis from eight randomized clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:395-405.

- Nash P, Kerschbaumer A, Dörner T, et al. Points to consider for the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases with Janus kinase inhibitors: a consensus statement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:71-87.

- Narla S, Silverberg JI. The suitability of treating atopic dermatitis with Janus kinase inhibitors. Exp Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18:439-459.

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction that usually manifests with eczematous lesions within hours to days after exposure to a contact allergen. The primary treatment of ACD consists of allergen avoidance, but medications also may be necessary to manage symptoms, particularly in cases where avoidance alone does not lead to resolution of dermatitis. At present, no medical therapies are explicitly approved for use in the management of ACD. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are a class of small molecule inhibitors that are used for the treatment of a range of inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Several oral and topical JAK inhibitors also have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for atopic dermatitis (AD). In this article, we discuss this important class of medications and the role that they may play in the off-label management of refractory ACD.

JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway

The JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway plays a crucial role in many biologic processes. Notably, JAK/STAT signaling is involved in the development and regulation of the immune system.1 The cascade begins when a particular transmembrane receptor binds a ligand, such as an interferon or interleukin.2 Upon ligand binding, the receptor dimerizes or oligomerizes, bringing the relevant JAK proteins into close approximation to each other.3 This allows the JAK proteins to autophosphorylate or transphosphorylate.2-4 Phosphorylation activates the JAK proteins and increases their kinase activity.3 In humans, there are 4 JAK proteins: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2.4 When activated, the JAK proteins phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues on the receptor, which creates a docking site for STAT proteins. After binding, the STAT proteins then are phosphorylated, leading to their dimerization and translocation to the nucleus.2,3 Once in the nucleus, the STAT proteins act as transcription factors for target genes.3

JAK Inhibitors

Janus kinase inhibitors are immunomodulatory medications that work through inhibition of 1 or more of the JAK proteins in the JAK/STAT pathway. Through this mechanism, JAK inhibitors can impede the activity of proinflammatory cytokines and T cells.4 A brief overview of the commercially available JAK inhibitors in Europe, Japan, and the United States is provided in the Table.5-29

Of the approved JAK inhibitors, more than 40% are indicated for AD. The first JAK inhibitor to be approved in the topical form was delgocitinib in 2020 in Japan.5 In a phase 3 trial, delgocitinib demonstrated significant reductions in modified Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score (P<.001) as well as Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) when compared with vehicle.30 Topical ruxolitinib soon followed when its approval for AD was announced by the FDA in 2021.31 Results from 2 phase 3 trials found that significantly more patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) treatment success (P<.0001) and a significant reduction in itch as measured by the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) with topical ruxolitinib vs vehicle.32

The first oral JAK inhibitor to attain approval for AD was baricitinib in Europe and Japan, but it is not currently approved for this indication in the United States by the FDA.11,12,33 Consistent findings across phase 3 trials revealed that baricitinib was more effective at achieving IGA treatment success and improved EASI scores compared with placebo.33

Upadacitinib, another oral JAK inhibitor, was subsequently approved for AD in Europe and Japan in 2021 and in the United States in early 2022.5,9,26,27 Two replicate phase 3 trials demonstrated significant improvement in EASI score, itch, and quality of life with upadacitinib compared with placebo (P<.0001).34 Abrocitinib was granted FDA approval for AD in the same time period, with phase 3 trials exhibiting greater responses in IGA and EASI scores vs placebo.35

Potential for Use in ACD

Given the successful use of JAK inhibitors in the management of AD, there is optimism that these medications also may have potential application in ACD. Recent literature suggests that the 2 conditions may be more closely related mechanistically than previously understood. As a result, AD and ACD often are managed with the same therapeutic agents.36

Although the exact etiology of ACD is still being elucidated, activation of T cells and cytokines plays an important role.37 Notably, more than 40 cytokines exert their effects through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, including IL-2, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ.37,38 A study on nickel contact allergy revealed that JAK/STAT activation may regulate the balance between IL-12 and IL-23 and increase type 1 T-helper (TH1) polarization.39 Skin inflammation and chronic pruritus, which are major components of ACD, also are thought to be mediated in part by JAK signaling.34,40

Animal studies have suggested that JAK inhibitors may show benefit in the management of ACD. Rats with oxazolone-induced ACD were found to have less swelling and epidermal thickening in the area of induced dermatitis after treatment with oral tofacitinib, comparable to the effects of cyclosporine. Tofacitinib was presumed to exert its effects through cytokine suppression, particularly that of IFN-γ, IL-22, and tumor necrosis factor α.41 In a separate study on mice with toluene-2,4-diisocyanate–induced ACD, both tofacitinib and another JAK inhibitor, oclacitinib, demonstrated inhibition of cytokine production, migration, and maturation of bone marrow–derived dendritic cells. Both topical and oral formulations of these 2 JAK inhibitors also were found to decrease scratching behavior; only the topicals improved ear thickness (used as a marker of skin inflammation), suggesting potential benefits to local application.42 In a murine model, oral delgocitinib also attenuated contact hypersensitivity via inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell proliferation and cytokine production.37 Finally, in a randomized clinical trial conducted on dogs with allergic dermatitis (of which 10% were presumed to be from contact allergy), oral oclacitinib significantly reduced pruritus and clinical severity scores vs placebo (P<.0001).43

There also are early clinical studies and case reports highlighting the effective use of JAK inhibitors in the management of ACD in humans. A 37-year-old man with occupational airborne ACD to Compositae saw full clearance of his dermatitis with daily oral abrocitinib after topical corticosteroids and dupilumab failed.44 Another patient, a 57-year-old woman, had near-complete resolution of chronic Parthenium-induced airborne ACD after starting twice-daily oral tofacitinib. Allergen avoidance, as well as multiple medications, including topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and azathioprine, previously failed in this patient.45 Finally, a phase 2 study on patients with irritant and nonirritant chronic hand eczema found that significantly more patients achieved treatment success (as measured by the physician global assessment) with topical delgocitinib vs vehicle (P=.009).46 Chronic hand eczema may be due to a variety of causes, including AD, irritant contact dermatitis, and ACD. Thus, these studies begin to highlight the potential role for JAK inhibitors in the management of refractory ACD.

Side Effects of JAK Inhibitors

The safety profile of JAK inhibitors must be taken into consideration. In general, topical JAK inhibitors are safe and well tolerated, with the majority of adverse events (AEs) seen in clinical trials considered mild or unrelated to the medication.30,32 Nasopharyngitis, local skin infection, and acne were reported; a systematic review found no increased risk of AEs with topical JAK inhibitors compared with placebo.30,32,47 Application-site reactions, a common concern among the existing topical calcineurin and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, were rare (approximately 2% of patients).47 The most frequent AEs seen in clinical trials of oral JAK inhibitors included acne, nasopharyngitis/upper respiratory tract infections, nausea, and headache.33-35 Herpes simplex virus infection and worsening of AD also were seen. Although elevations in creatine phosphokinase levels were reported, patients often were asymptomatic and elevations were related to exercise or resolved without treatment interruption.33-35

As a class, JAK inhibitors carry a boxed warning for serious infections, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and mortality. The FDA placed this label on JAK inhibitors because of the results of a randomized controlled trial of oral tofacitinib vs tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors in RA.48,49 Notably, participants in the trial had to be 50 years or older and have at least 1 additional cardiovascular risk factor. Postmarket safety data are still being collected for patients with AD and other dermatologic conditions, but the findings of safety analyses have been reassuring to date.50,51 Regular follow-up and routine laboratory monitoring are recommended for any patient started on an oral JAK inhibitor, which often includes monitoring of the complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipids, as well as baseline screening for tuberculosis and hepatitis.52,53 For topical JAK inhibitors, no specific laboratory monitoring is recommended.

Finally, it must be considered that the challenges of off-label prescribing combined with high costs may limit access to JAK inhibitors for use in ACD.

Final Interpretation

Early investigations, including studies on animals and humans, suggest that JAK inhibitors are a promising option in the management of treatment-refractory ACD. Patients and providers should be aware of both the benefits and known side effects of JAK inhibitors prior to treatment initiation.

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction that usually manifests with eczematous lesions within hours to days after exposure to a contact allergen. The primary treatment of ACD consists of allergen avoidance, but medications also may be necessary to manage symptoms, particularly in cases where avoidance alone does not lead to resolution of dermatitis. At present, no medical therapies are explicitly approved for use in the management of ACD. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are a class of small molecule inhibitors that are used for the treatment of a range of inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Several oral and topical JAK inhibitors also have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for atopic dermatitis (AD). In this article, we discuss this important class of medications and the role that they may play in the off-label management of refractory ACD.

JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway

The JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway plays a crucial role in many biologic processes. Notably, JAK/STAT signaling is involved in the development and regulation of the immune system.1 The cascade begins when a particular transmembrane receptor binds a ligand, such as an interferon or interleukin.2 Upon ligand binding, the receptor dimerizes or oligomerizes, bringing the relevant JAK proteins into close approximation to each other.3 This allows the JAK proteins to autophosphorylate or transphosphorylate.2-4 Phosphorylation activates the JAK proteins and increases their kinase activity.3 In humans, there are 4 JAK proteins: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2.4 When activated, the JAK proteins phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues on the receptor, which creates a docking site for STAT proteins. After binding, the STAT proteins then are phosphorylated, leading to their dimerization and translocation to the nucleus.2,3 Once in the nucleus, the STAT proteins act as transcription factors for target genes.3

JAK Inhibitors

Janus kinase inhibitors are immunomodulatory medications that work through inhibition of 1 or more of the JAK proteins in the JAK/STAT pathway. Through this mechanism, JAK inhibitors can impede the activity of proinflammatory cytokines and T cells.4 A brief overview of the commercially available JAK inhibitors in Europe, Japan, and the United States is provided in the Table.5-29

Of the approved JAK inhibitors, more than 40% are indicated for AD. The first JAK inhibitor to be approved in the topical form was delgocitinib in 2020 in Japan.5 In a phase 3 trial, delgocitinib demonstrated significant reductions in modified Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score (P<.001) as well as Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) when compared with vehicle.30 Topical ruxolitinib soon followed when its approval for AD was announced by the FDA in 2021.31 Results from 2 phase 3 trials found that significantly more patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) treatment success (P<.0001) and a significant reduction in itch as measured by the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) with topical ruxolitinib vs vehicle.32

The first oral JAK inhibitor to attain approval for AD was baricitinib in Europe and Japan, but it is not currently approved for this indication in the United States by the FDA.11,12,33 Consistent findings across phase 3 trials revealed that baricitinib was more effective at achieving IGA treatment success and improved EASI scores compared with placebo.33

Upadacitinib, another oral JAK inhibitor, was subsequently approved for AD in Europe and Japan in 2021 and in the United States in early 2022.5,9,26,27 Two replicate phase 3 trials demonstrated significant improvement in EASI score, itch, and quality of life with upadacitinib compared with placebo (P<.0001).34 Abrocitinib was granted FDA approval for AD in the same time period, with phase 3 trials exhibiting greater responses in IGA and EASI scores vs placebo.35

Potential for Use in ACD

Given the successful use of JAK inhibitors in the management of AD, there is optimism that these medications also may have potential application in ACD. Recent literature suggests that the 2 conditions may be more closely related mechanistically than previously understood. As a result, AD and ACD often are managed with the same therapeutic agents.36

Although the exact etiology of ACD is still being elucidated, activation of T cells and cytokines plays an important role.37 Notably, more than 40 cytokines exert their effects through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, including IL-2, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ.37,38 A study on nickel contact allergy revealed that JAK/STAT activation may regulate the balance between IL-12 and IL-23 and increase type 1 T-helper (TH1) polarization.39 Skin inflammation and chronic pruritus, which are major components of ACD, also are thought to be mediated in part by JAK signaling.34,40

Animal studies have suggested that JAK inhibitors may show benefit in the management of ACD. Rats with oxazolone-induced ACD were found to have less swelling and epidermal thickening in the area of induced dermatitis after treatment with oral tofacitinib, comparable to the effects of cyclosporine. Tofacitinib was presumed to exert its effects through cytokine suppression, particularly that of IFN-γ, IL-22, and tumor necrosis factor α.41 In a separate study on mice with toluene-2,4-diisocyanate–induced ACD, both tofacitinib and another JAK inhibitor, oclacitinib, demonstrated inhibition of cytokine production, migration, and maturation of bone marrow–derived dendritic cells. Both topical and oral formulations of these 2 JAK inhibitors also were found to decrease scratching behavior; only the topicals improved ear thickness (used as a marker of skin inflammation), suggesting potential benefits to local application.42 In a murine model, oral delgocitinib also attenuated contact hypersensitivity via inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell proliferation and cytokine production.37 Finally, in a randomized clinical trial conducted on dogs with allergic dermatitis (of which 10% were presumed to be from contact allergy), oral oclacitinib significantly reduced pruritus and clinical severity scores vs placebo (P<.0001).43

There also are early clinical studies and case reports highlighting the effective use of JAK inhibitors in the management of ACD in humans. A 37-year-old man with occupational airborne ACD to Compositae saw full clearance of his dermatitis with daily oral abrocitinib after topical corticosteroids and dupilumab failed.44 Another patient, a 57-year-old woman, had near-complete resolution of chronic Parthenium-induced airborne ACD after starting twice-daily oral tofacitinib. Allergen avoidance, as well as multiple medications, including topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and azathioprine, previously failed in this patient.45 Finally, a phase 2 study on patients with irritant and nonirritant chronic hand eczema found that significantly more patients achieved treatment success (as measured by the physician global assessment) with topical delgocitinib vs vehicle (P=.009).46 Chronic hand eczema may be due to a variety of causes, including AD, irritant contact dermatitis, and ACD. Thus, these studies begin to highlight the potential role for JAK inhibitors in the management of refractory ACD.

Side Effects of JAK Inhibitors

The safety profile of JAK inhibitors must be taken into consideration. In general, topical JAK inhibitors are safe and well tolerated, with the majority of adverse events (AEs) seen in clinical trials considered mild or unrelated to the medication.30,32 Nasopharyngitis, local skin infection, and acne were reported; a systematic review found no increased risk of AEs with topical JAK inhibitors compared with placebo.30,32,47 Application-site reactions, a common concern among the existing topical calcineurin and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, were rare (approximately 2% of patients).47 The most frequent AEs seen in clinical trials of oral JAK inhibitors included acne, nasopharyngitis/upper respiratory tract infections, nausea, and headache.33-35 Herpes simplex virus infection and worsening of AD also were seen. Although elevations in creatine phosphokinase levels were reported, patients often were asymptomatic and elevations were related to exercise or resolved without treatment interruption.33-35

As a class, JAK inhibitors carry a boxed warning for serious infections, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and mortality. The FDA placed this label on JAK inhibitors because of the results of a randomized controlled trial of oral tofacitinib vs tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors in RA.48,49 Notably, participants in the trial had to be 50 years or older and have at least 1 additional cardiovascular risk factor. Postmarket safety data are still being collected for patients with AD and other dermatologic conditions, but the findings of safety analyses have been reassuring to date.50,51 Regular follow-up and routine laboratory monitoring are recommended for any patient started on an oral JAK inhibitor, which often includes monitoring of the complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipids, as well as baseline screening for tuberculosis and hepatitis.52,53 For topical JAK inhibitors, no specific laboratory monitoring is recommended.

Finally, it must be considered that the challenges of off-label prescribing combined with high costs may limit access to JAK inhibitors for use in ACD.

Final Interpretation

Early investigations, including studies on animals and humans, suggest that JAK inhibitors are a promising option in the management of treatment-refractory ACD. Patients and providers should be aware of both the benefits and known side effects of JAK inhibitors prior to treatment initiation.

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:273-287.

- Bousoik E, Montazeri Aliabadi H. “Do we know Jack” about JAK? a closer look at JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Front Oncol. 2018;8:287.

- Jatiani SS, Baker SJ, Silverman LR, et al. Jak/STAT pathways in cytokine signaling and myeloproliferative disorders: approaches for targeted therapies. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:979-993.

- Seif F, Khoshmirsafa M, Aazami H, et al. The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2017;15:23.

- Traidl S, Freimooser S, Werfel T. Janus kinase inhibitors for the therapy of atopic dermatitis. Allergol Select. 2021;5:293-304.

- Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215309s001lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo (abrocitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/213871s000lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 17, 2021. Updated November 10, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/cibinqo

- New drugs approved in FY 2021. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000246734.pdf

- Olumiant (baricitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/207924s007lbl.pdf

- Olumiant. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 16, 2017. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/olumiant

- Review report: Olumiant. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. April 21, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000243207.pdf

- Sotyktu (deucravacitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/214958s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic (fedratinib) capsules. Prescribing information. Celgene Corporation; 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212327s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 3, 2021. Updated December 8, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/inrebic

- Jyseleca. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published September 28, 2020. Updated November 9, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/jyseleca-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Jyseleca. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. September 8, 2020. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000247830.pdf

- Vonjo (pacritinib) capsules. Prescribing information. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Review report: Smyraf. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. February 28, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000233074.pdf

- Jakafi (ruxolitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/202192s023lbl.pdf

- Jakavi. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published October 4, 2012. Updated May 18, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/jakavi

- New drugs approved in FY 2014. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000229076.pdf

- Xeljanz (tofacitinib). Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/203214s028,208246s013,213082s003lbl.pdf

- Xeljanz. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/xeljanz-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Xeljanz. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000237584.pdf

- Rinvoq (upadacitinib) extended-release tablets. Prescribing information. AbbVie Inc; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/211675s003lbl.pdf

- Rinvoq. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 18, 2019. Updated December 7, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/rinvoq

- New drugs approved in FY 2019. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000235289.pdfs

- New drugs approved in May 2022. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000248626.pdf

- Nakagawa H, Nemoto O, Igarashi A, et al. Delgocitinib ointment, a topical Janus kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study and an open-label, long-term extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:823-831. Erratum appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1069.

- Sideris N, Paschou E, Bakirtzi K, et al. New and upcoming topical treatments for atopic dermatitis: a review of the literature. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4974.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 2 phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:863-872.

- Radi G, Simonetti O, Rizzetto G, et al. Baricitinib: the first Jak inhibitor approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adult patients. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9:1575.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397:2151-2168. Erratum appears in Lancet. 2021;397:2150.

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112.

- Johnson H, Novack DE, Adler BL, et al. Can atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis coexist? Cutis. 2022;110:139-142.

- Amano W, Nakajima S, Yamamoto Y, et al. JAK inhibitor JTE-052 regulates contact hypersensitivity by downmodulating T cell activation and differentiation. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84:258-265.

- O’Shea JJ, Schwartz DM, Villarino AV, et al. The JAK-STAT pathway: impact on human disease and therapeutic intervention. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:311-328.

- Bechara R, Antonios D, Azouri H, et al. Nickel sulfate promotes IL-17A producing CD4+ T cells by an IL-23-dependent mechanism regulated by TLR4 and JAK-STAT pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2140-2148.

- Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J, et al. Sensory neurons co-opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell. 2017;171:217-228.e13.

- Fujii Y, Sengoku T. Effects of the Janus kinase inhibitor CP-690550 (tofacitinib) in a rat model of oxazolone-induced chronic dermatitis. Pharmacology. 2013;91:207-213.

- Fukuyama T, Ehling S, Cook E, et al. Topically administered Janus-kinase inhibitors tofacitinib and oclacitinib display impressive antipruritic and anti-inflammatory responses in a model of allergic dermatitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;354:394-405.

- Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, et al. Efficacy and safety of oclacitinib for the control of pruritus and associated skin lesions in dogs with canine allergic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24:479, E114.

- Baltazar D, Shinamoto SR, Hamann CP, et al. Occupational airborne allergic contact dermatitis to invasive Compositae species treated with abrocitinib: a case report. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:542-544.

- Muddebihal A, Sardana K, Sinha S, et al. Tofacitinib in refractory Parthenium-induced airborne allergic contact dermatitis [published online October 12, 2022]. Contact Dermatitis. doi:10.1111/cod.14234

- Worm M, Bauer A, Elsner P, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical delgocitinib in patients with chronic hand eczema: data from a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase IIa study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1103-1110.

- Chen J, Cheng J, Yang H, et al. The efficacy and safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:495-496.

- Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires warnings about increased risk of serious heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death for JAK inhibitors that treat certain chronic inflammatory conditions. Updated December 7, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-warnings-about-increased-risk-serious-heart-related-events-cancer-blood-clots-and-death

- Chen TL, Lee LL, Huang HK, et al. Association of risk of incident venous thromboembolism with atopic dermatitis and treatment with Janus kinase inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1254-1261.

- King B, Maari C, Lain E, et al. Extended safety analysis of baricitinib 2 mg in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: an integrated analysis from eight randomized clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:395-405.

- Nash P, Kerschbaumer A, Dörner T, et al. Points to consider for the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases with Janus kinase inhibitors: a consensus statement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:71-87.

- Narla S, Silverberg JI. The suitability of treating atopic dermatitis with Janus kinase inhibitors. Exp Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18:439-459.

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:273-287.

- Bousoik E, Montazeri Aliabadi H. “Do we know Jack” about JAK? a closer look at JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Front Oncol. 2018;8:287.

- Jatiani SS, Baker SJ, Silverman LR, et al. Jak/STAT pathways in cytokine signaling and myeloproliferative disorders: approaches for targeted therapies. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:979-993.

- Seif F, Khoshmirsafa M, Aazami H, et al. The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2017;15:23.

- Traidl S, Freimooser S, Werfel T. Janus kinase inhibitors for the therapy of atopic dermatitis. Allergol Select. 2021;5:293-304.

- Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215309s001lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo (abrocitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/213871s000lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 17, 2021. Updated November 10, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/cibinqo

- New drugs approved in FY 2021. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000246734.pdf

- Olumiant (baricitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/207924s007lbl.pdf

- Olumiant. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 16, 2017. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/olumiant

- Review report: Olumiant. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. April 21, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000243207.pdf

- Sotyktu (deucravacitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/214958s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic (fedratinib) capsules. Prescribing information. Celgene Corporation; 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212327s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 3, 2021. Updated December 8, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/inrebic

- Jyseleca. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published September 28, 2020. Updated November 9, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/jyseleca-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Jyseleca. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. September 8, 2020. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000247830.pdf

- Vonjo (pacritinib) capsules. Prescribing information. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Review report: Smyraf. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. February 28, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000233074.pdf

- Jakafi (ruxolitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/202192s023lbl.pdf

- Jakavi. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published October 4, 2012. Updated May 18, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/jakavi

- New drugs approved in FY 2014. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000229076.pdf

- Xeljanz (tofacitinib). Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/203214s028,208246s013,213082s003lbl.pdf

- Xeljanz. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/xeljanz-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Xeljanz. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000237584.pdf

- Rinvoq (upadacitinib) extended-release tablets. Prescribing information. AbbVie Inc; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/211675s003lbl.pdf

- Rinvoq. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 18, 2019. Updated December 7, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/rinvoq

- New drugs approved in FY 2019. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000235289.pdfs

- New drugs approved in May 2022. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000248626.pdf

- Nakagawa H, Nemoto O, Igarashi A, et al. Delgocitinib ointment, a topical Janus kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study and an open-label, long-term extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:823-831. Erratum appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1069.

- Sideris N, Paschou E, Bakirtzi K, et al. New and upcoming topical treatments for atopic dermatitis: a review of the literature. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4974.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 2 phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:863-872.

- Radi G, Simonetti O, Rizzetto G, et al. Baricitinib: the first Jak inhibitor approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adult patients. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9:1575.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397:2151-2168. Erratum appears in Lancet. 2021;397:2150.

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112.

- Johnson H, Novack DE, Adler BL, et al. Can atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis coexist? Cutis. 2022;110:139-142.

- Amano W, Nakajima S, Yamamoto Y, et al. JAK inhibitor JTE-052 regulates contact hypersensitivity by downmodulating T cell activation and differentiation. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84:258-265.

- O’Shea JJ, Schwartz DM, Villarino AV, et al. The JAK-STAT pathway: impact on human disease and therapeutic intervention. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:311-328.

- Bechara R, Antonios D, Azouri H, et al. Nickel sulfate promotes IL-17A producing CD4+ T cells by an IL-23-dependent mechanism regulated by TLR4 and JAK-STAT pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2140-2148.

- Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J, et al. Sensory neurons co-opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell. 2017;171:217-228.e13.

- Fujii Y, Sengoku T. Effects of the Janus kinase inhibitor CP-690550 (tofacitinib) in a rat model of oxazolone-induced chronic dermatitis. Pharmacology. 2013;91:207-213.

- Fukuyama T, Ehling S, Cook E, et al. Topically administered Janus-kinase inhibitors tofacitinib and oclacitinib display impressive antipruritic and anti-inflammatory responses in a model of allergic dermatitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;354:394-405.

- Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, et al. Efficacy and safety of oclacitinib for the control of pruritus and associated skin lesions in dogs with canine allergic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24:479, E114.

- Baltazar D, Shinamoto SR, Hamann CP, et al. Occupational airborne allergic contact dermatitis to invasive Compositae species treated with abrocitinib: a case report. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:542-544.

- Muddebihal A, Sardana K, Sinha S, et al. Tofacitinib in refractory Parthenium-induced airborne allergic contact dermatitis [published online October 12, 2022]. Contact Dermatitis. doi:10.1111/cod.14234

- Worm M, Bauer A, Elsner P, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical delgocitinib in patients with chronic hand eczema: data from a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase IIa study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1103-1110.

- Chen J, Cheng J, Yang H, et al. The efficacy and safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:495-496.

- Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires warnings about increased risk of serious heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death for JAK inhibitors that treat certain chronic inflammatory conditions. Updated December 7, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-warnings-about-increased-risk-serious-heart-related-events-cancer-blood-clots-and-death

- Chen TL, Lee LL, Huang HK, et al. Association of risk of incident venous thromboembolism with atopic dermatitis and treatment with Janus kinase inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1254-1261.

- King B, Maari C, Lain E, et al. Extended safety analysis of baricitinib 2 mg in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: an integrated analysis from eight randomized clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:395-405.

- Nash P, Kerschbaumer A, Dörner T, et al. Points to consider for the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases with Janus kinase inhibitors: a consensus statement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:71-87.

- Narla S, Silverberg JI. The suitability of treating atopic dermatitis with Janus kinase inhibitors. Exp Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18:439-459.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are a novel class of small molecule inhibitors that modulate the JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathway.

- Select JAK inhibitors have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the management of atopic dermatitis. Their use in allergic contact dermatitis is under active investigation.

- Regular follow-up and laboratory monitoring for patients on oral JAK inhibitors is recommended, given the potential for treatment-related adverse effects.

Photoallergic Contact Dermatitis: No Fun in the Sun

Photoallergic contact dermatitis (PACD), a subtype of allergic contact dermatitis that occurs because of the specific combination of exposure to an exogenous chemical applied topically to the skin and UV radiation, may be more common than was once thought.1 Although the incidence in the general population is unknown, current research points to approximately 20% to 40% of patients with suspected photosensitivity having a PACD diagnosis.2 Recently, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) reported that 21% of 373 patients undergoing photopatch testing (PPT) were diagnosed with PACD2; however, PPT is not routinely performed, which may contribute to underdiagnosis.

Mechanism of Disease

Similar to allergic contact dermatitis, PACD is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction; however, it only occurs when an exogenous chemical is applied topically to the skin with concomitant exposure to UV radiation, usually in the UVA range (315–400 nm).3,4 When exposed to UV radiation, it is thought that the exogenous chemical combines with a protein in the skin and transforms into a photoantigen. In the sensitization phase, the photoantigen is taken up by antigen-presenting cells in the epidermis and transported to local lymph nodes where antigen-specific T cells are generated.5 In the elicitation phase, the inflammatory reaction of PACD occurs upon subsequent exposure to the same chemical plus UV radiation.4 Development of PACD does not necessarily depend on the dose of the chemical or the amount of UV radiation.6 Why certain individuals may be more susceptible is unknown, though major histocompatibility complex haplotypes could be influential.7,8

Clinical Manifestations

Photoallergic contact dermatitis primarily presents in sun-exposed areas of the skin (eg, face, neck, V area of the chest, dorsal upper extremities) with sparing of naturally photoprotected sites, such as the upper eyelids and nasolabial and retroauricular folds. Other than its characteristic photodistribution, PACD often is clinically indistinguishable from routine allergic contact dermatitis. It manifests as a pruritic, poorly demarcated, eczematous or sometimes vesiculobullous eruption that develops in a delayed fashion—24 to 72 hours after sun exposure. The dermatitis may extend to other parts of the body either through spread of the chemical agent by the hands or clothing or due to the systemic nature of the immune response. The severity of the presentation can vary depending on multiple factors, such as concentration and absorption of the agent, length of exposure, intensity and duration of UV radiation exposure, and individual susceptibility.4 Chronic PACD may become lichenified. Generally, rashes resolve after discontinuation of the causative agent; however, long-term exposure may lead to development of chronic actinic dermatitis, with persistent photodistributed eczema regardless of contact with the initial inciting agent.9

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with photodistributed dermatitis is broad; therefore, taking a thorough history is important. Considerations include age of onset, timing and persistence of reactions, use of topical and systemic medications (both prescription and over-the-counter [OTC]), personal care products, occupation, and hobbies, as well as a thorough review of systems.

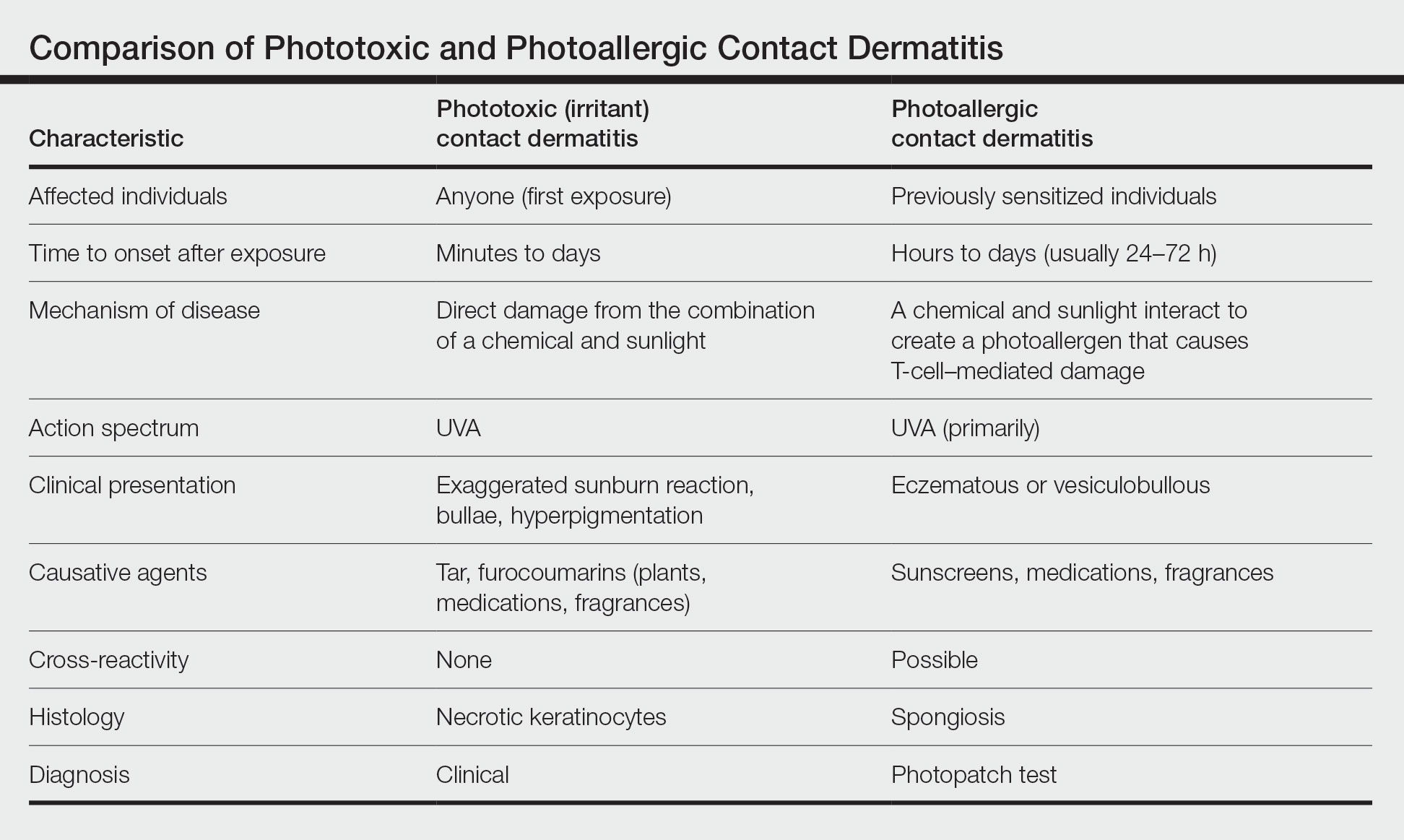

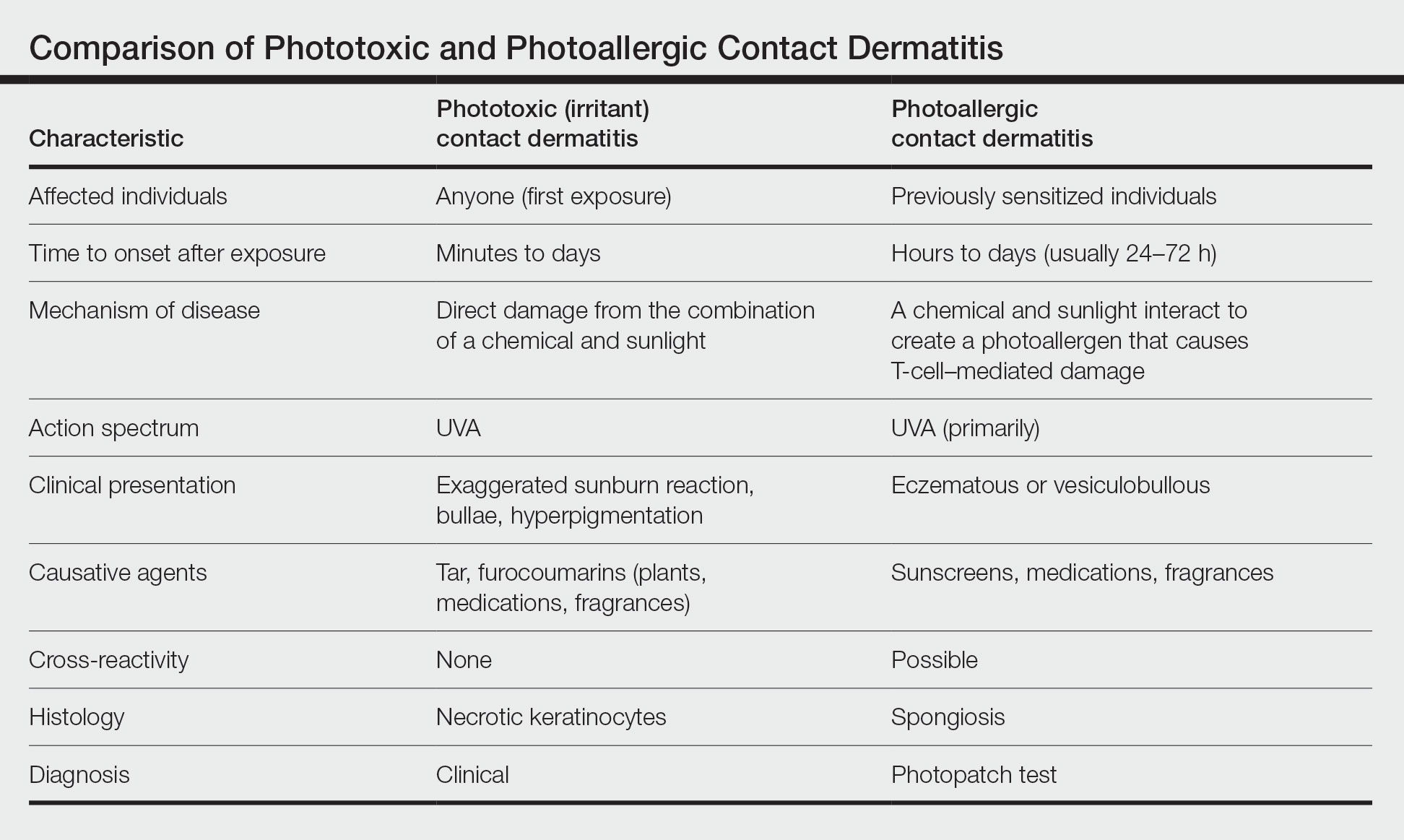

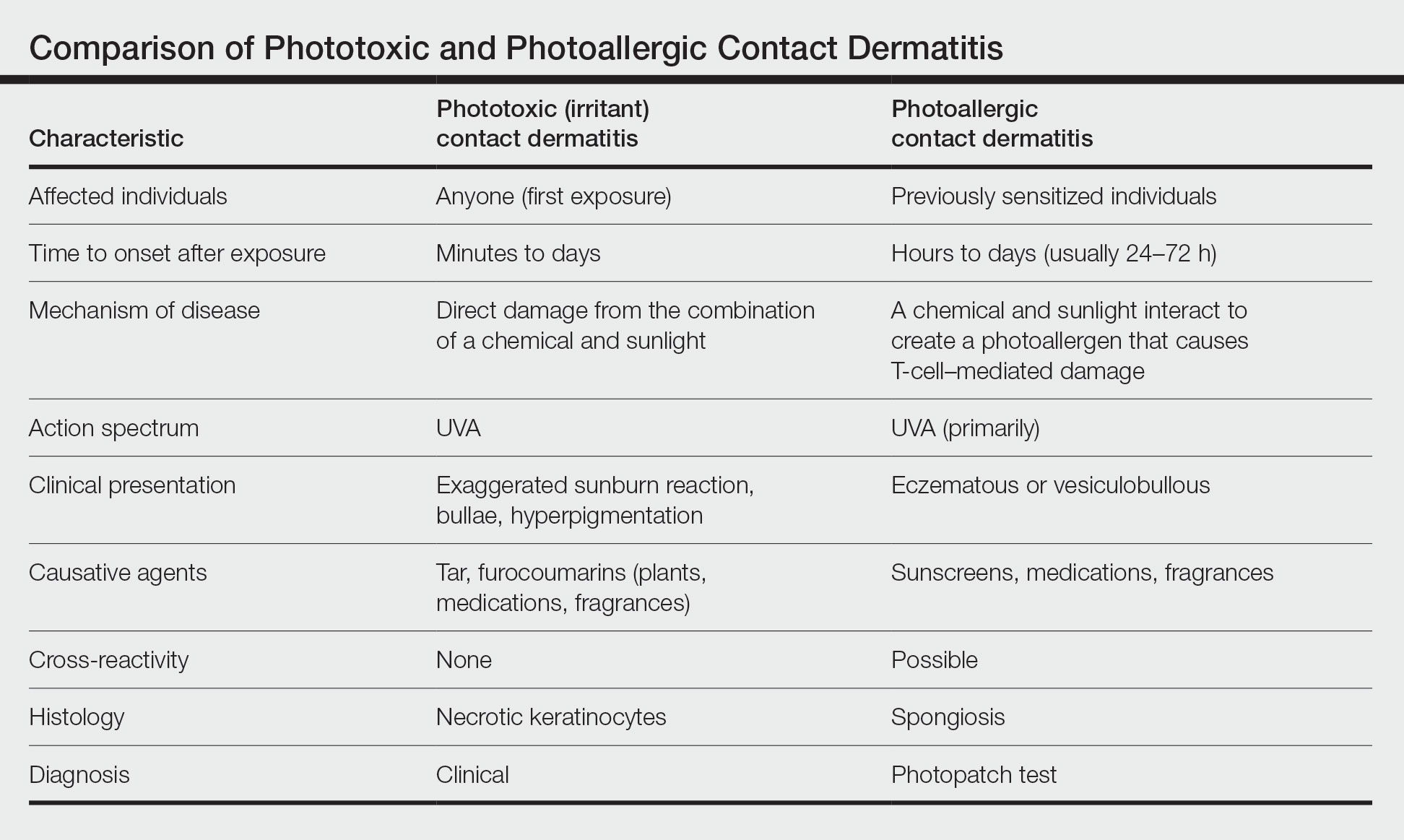

It is important to distinguish PACD from phototoxic contact dermatitis (PTCD)(also known as photoirritant contact dermatitis)(Table). Asking about the onset and timing of the eruption may be critical for distinction, as PTCD can occur within minutes to hours of the first exposure to a chemical and UV radiation, while there is a sensitization delay in PACD.6 Phytophotodermatitis is a well-known type of PTCD caused by exposure to furocoumarin-containing plants, most commonly limes.10 Other causes of PTCD include tar products and certain medications.11 Importantly, PPT to a known phototoxic chemical should never be performed because it will cause a strong reaction in anyone tested, regardless of exposure history.

Other diagnoses to consider include photoaggravated dermatoses (eg, atopic dermatitis, lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis) and idiopathic photodermatoses (eg, chronic actinic dermatitis, actinic prurigo, polymorphous light eruption). Although atopic dermatitis usually improves with UV light exposure, photoaggravated atopic dermatitis is suggested in eczema patients who flare with sun exposure, in a seasonal pattern, or after phototherapy; this condition is challenging to differentiate from PACD if PPT is not performed.12 The diagnosis of idiopathic photodermatoses is nuanced; however, asking about the timeline of the reaction including onset, duration, and persistence, as well as characterization of unique clinical features, can help in differentiation.13 In certain scenarios, a biopsy may be helpful. A thorough review of systems will help to assess for autoimmune connective tissue disorders, and relevant serologies should be checked as indicated.

Diagnosis

Histologically, PACD presents similarly to allergic contact dermatitis with spongiotic dermatitis; therefore, biopsy cannot be relied upon to make the diagnosis.6 Photopatch testing is required for definitive diagnosis. It is reasonable to perform PPT in any patient with chronic dermatitis primarily affecting sun-exposed areas without a clear alternative diagnosis.14,15 Of note, at present there are no North American consensus guidelines for PPT, but typically duplicate sets of photoallergens are applied to both sides of the patient’s back and one side is exposed to UVA radiation. The reactions are compared after 48 to 96 hours.15 A positive reaction only at the irradiated site is consistent with photoallergy, while a reaction of equal strength at both the irradiated and nonirradiated sites indicates regular contact allergy. The case of a reaction occurring at both sites with a stronger response at the irradiated site is known as photoaggravated contact allergy, which can be thought of as allergic contact dermatitis that worsens but does not solely occur with exposure to sunlight.

Although PPT is necessary for the accurate diagnosis of PACD, it is infrequently used. Two surveys of 112 and 117 American Contact Dermatitis Society members, respectively, have revealed that only around half performed PPT, most of them testing fewer than 20 times per year.16,17 Additionally, there was variability in the test methodology and allergens employed. Nevertheless, most respondents tested sunscreens, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), fragrances, and their patients’ own products.16,17 The most common reasons for not performing PPT were lack of equipment, insufficient skills, rare clinical suspicion, and cost. Dermatologists at academic centers performed more PPT than those in other practice settings, including multispecialty group practices and private offices.16 These findings highlight multiple factors that may contribute to reduced patient access to PPT and thus potential underdiagnosis of PACD.

Common Photoallergens

The most common photoallergens change over time in response to market trends; for example, fragrance was once a top photoallergen in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s but declined in prominence after musk ambrette—the primary allergen associated with PACD at the time—was removed as an ingredient in fragrances.18

In the largest and most recent PPT series from North America (1999-2009),2 sunscreens comprised 7 of the top 10 most common photoallergens, which is consistent with other studies showing sunscreens to be the most common North American photoallergens.19-22 The frequency of PACD due to sunscreens likely relates to their increasing use worldwide as awareness of photocarcinogenesis and photoaging grows, as well as the common use of UV filters in nonsunscreen personal care products, ranging from lip balms to perfumes and bodywashes. Chemical (organic) UV filters—in particular oxybenzone (benzophenone-3) and avobenzone (butyl methoxydibenzoylmethane)—are the most common sunscreen photoallergens.2,23 Para-aminobenzoic acid was once a common photoallergen, but it is no longer used in US sunscreens due to safety concerns.19,20 The physical (inorganic) UV filters zinc oxide and titanium dioxide are not known photosensitizers.

Methylisothiazolinone (MI) is a highly allergenic preservative commonly used in a wide array of personal care products, including sunscreens.24 In the most recent NACDG patch test data, MI was the second most common contact allergen.25 Allergic contact dermatitis caused by MI in sunscreen can mimic PACD.26 In addition, MI can cause photoaggravated contact dermatitis, with some affected patients experiencing ongoing photosensitivity even after avoiding this allergen.26-30 The European Union and Canada have introduced restrictions on the use of MI in personal care products, but no such regulatory measures have been taken in the United States to date.25,31,32

After sunscreens, another common cause of PACD are topical NSAIDs, which are frequently used for musculoskeletal pain relief. These are of particular concern in Europe, where a variety of formulations are widely available OTC.33 Ketoprofen and etofenamate are responsible for the largest number of PACD reactions in Europe.2,34,35 Meanwhile, the only OTC topical NSAID available in the United States is diclofenac gel, which was approved in 2020. Cases of PACD due to use of diclofenac gel have been reported in the literature, but testing in larger populations is needed.36-39

Notably, ketoprofen may co- or cross-react with certain UV filters—oxybenzone and octocrylene—and the lipid-lowering agent fenofibrate due to chemical similarities.40-43 Despite the relatively high number of photoallergic reactions to ketoprofen in the NACDG photopatch series, only 25% (5/20) were considered clinically relevant (ie, the allergen could not be verified as present in the known skin contactants of the patient, and the patient was not exposed to circumstances in which contact with materials known to contain the allergen would likely occur), which suggests that they likely represented cross-reactions in patients sensitized to sunscreens.2

Other agents that may cause PACD include antimicrobials, plants and plant derivatives, and pesticides.2,4,18 The antimicrobial fentichlor is a common cause of positive PPT reactions, but it rarely is clinically relevant.44

Treatment

The primary management of PACD centers on identification of the causative photoallergen to avoid future exposure. Patients should be educated on the various names by which the causative allergen can be identified on product labels and should be given a list of safe products that are free from relevant allergens and cross-reacting chemicals.45 Additionally, sun protection education should be provided. Exposure to UVA radiation can occur through windows, making the use of broad-spectrum sunscreens and protective clothing crucial. In cases of sunscreen-induced PACD, the responsible chemical UV filter(s) should be avoided, or alternatively, patients may use physical sunscreens containing only zinc oxide and/or titanium dioxide as active ingredients, as these are not known to cause PACD.4

When avoidance alone is insufficient, topical corticosteroids are the usual first-line treatment for localized PACD. When steroid-sparing treatments are preferred, topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus may be used. If PACD is more widespread and severe, systemic therapy using steroids or steroid-sparing agents may be necessary to provide symptomatic relief.4

Final Interpretation

Photoallergic contact dermatitis is not uncommon, particularly among photosensitive patients. Most cases are due to sunscreens or topical NSAIDs. Consideration of PPT should be given in any patient with a chronic photodistributed dermatitis to evaluate for the possibility of PACD.

- Darvay A, White IR, Rycroft RJ, et al. Photoallergic contact dermatitis is uncommon. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:597-601.

- DeLeo VA, Adler BL, Warshaw EM, et al. Photopatch test results of the North American contact dermatitis group, 1999-2009. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2022;38:288-291.

- Kerr A, Ferguson J. Photoallergic contact dermatitis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2010;26:56-65.

- As¸kın Ö, Cesur SK, Engin B, et al. Photoallergic contact dermatitis. Curr Derm Rep. 2019;8:157-163.

- Wilm A, Berneburg M. Photoallergy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:7-13.

- DeLeo VA. Photocontact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:279-288.

- Imai S, Atarashi K, Ikesue K, et al. Establishment of murine model of allergic photocontact dermatitis to ketoprofen and characterization of pathogenic T cells. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;41:127-136.

- Tokura Y, Yagi H, Satoh T, et al. Inhibitory effect of melanin pigment on sensitization and elicitation of murine contact photosensitivity: mechanism of low responsiveness in C57BL/10 background mice. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:673-678.

- Stein KR, Scheinfeld NS. Drug-induced photoallergic and phototoxic reactions. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:431-443.

- Janusz SC, Schwartz RA. Botanical briefs: phytophotodermatitis is an occupational and recreational dermatosis in the limelight. Cutis. 2021;107:187-189.

- Atwal SK, Chen A, Adler BL. Phototoxic contact dermatitis from over-the-counter 8-methoxypsoralen. Cutis. 2022;109:E2-E3.

- Rutter KJ, Farrar MD, Marjanovic EJ, et al. Clinicophotobiological characterization of photoaggravated atopic dermatitis [published online July 27, 2022]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.2823

- Lecha M. Idiopathic photodermatoses: clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:499-505.

- Marks JG Jr, Anderson BE, DeLeo VA. Contact & Occupational Dermatology. 4th ed. Jaypee Brothers; 2016.

- Bruynzeel DP, Ferguson J, Andersen K, et al. Photopatch testing: a consensus methodology for Europe. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:679-682.

- Kim T, Taylor JS, Maibach HI, et al. Photopatch testing among members of the American Contact Dermatitis Society. Dermatitis. 2020;31:59-67.

- Asemota E, Crawford G, Kovarik C, et al. A survey examining photopatch test and phototest methodologies of contact dermatologists in the United States: platform for developing a consensus. Dermatitis. 2017;28:265-269.

- Scalf LA, Davis MD, Rohlinger AL, et al. Photopatch testing of 182 patients: a 6-year experience at the Mayo Clinic. Dermatitis. 2009;20:44-52.

- Greenspoon J, Ahluwalia R, Juma N, et al. Allergic and photoallergic contact dermatitis: a 10-year experience. Dermatitis. 2013;24:29-32.

- Victor FC, Cohen DE, Soter NA. A 20-year analysis of previous and emerging allergens that elicit photoallergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:605-610.

- Schauder S, Ippen H. Contact and photocontact sensitivity to sunscreens. review of a 15-year experience and of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:221-232.

- Collaris EJ, Frank J. Photoallergic contact dermatitis caused by ultraviolet filters in different sunscreens. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(suppl 1):35-37.

- Heurung AR, Raju SI, Warshaw EM. Adverse reactions to sunscreen agents: epidemiology, responsible irritants and allergens, clinical characteristics, and management. Dermatitis. 2014;25:289-326.

- Reeder M, Atwater AR. Methylisothiazolinone and isothiazolinone allergy. Cutis. 2019;104:94-96.

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch Test Results: 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123.

- Kullberg SA, Voller LM, Warshaw EM. Methylisothiazolinone in “dermatology-recommended” sunscreens: an important mimicker of photoallergic contact dermatitis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2021;37:366-370.

- Herman A, Aerts O, de Montjoye L, et al. Isothiazolinone derivatives and allergic contact dermatitis: a review and update. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:267-276.

- Adler BL, Houle MC, Pratt M. Photoaggravated contact dermatitis to methylisothiazolinone and associated photosensitivity: a case series [published online January 25, 2022]. Dermatitis. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000833

- Aerts O, Goossens A, Marguery MC, et al. Photoaggravated allergic contact dermatitis and transient photosensitivity caused by methylisothiazolinone. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:241-245.

- Pirmez R, Fernandes AL, Melo MG. Photoaggravated contact dermatitis to Kathon CG (methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone): a novel pattern of involvement in a growing epidemic?. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1343-1344.

- Uter W, Aalto-Korte K, Agner T, et al. The epidemic of methylisothiazolinone contact allergy in Europe: follow-up on changing exposures.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:333-339.

- Government of Canada. Changes to the cosmetic ingredient hotlist. December 3, 2019. Updated August 26, 2022. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredient-hotlist-prohibited-restricted-ingredients/changes.html

- Barkin RL. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: the importance of drug, delivery, and therapeutic outcome. Am J Ther. 2015;22:388-407.

- European Multicentre Photopatch Test Study (EMCPPTS) Taskforce. A European multicentre photopatch test study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:1002-1009.