User login

Necrotizing Cellulitis With Multiple Abscesses on the Leg Caused by Serratia marcescens

A gram-negative bacillus of the Enterobacteriaceae family, Serratia marcescens is an organism known to cause bacteremia, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, endocarditis, meningitis, and septic arthritis.1 Unusual cases of cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis (NF) caused by S marcescens also have been reported.2,3 This entity has been initially described in immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised patients.4 Both community and nosocomial cases also have been reported.3

Case Report

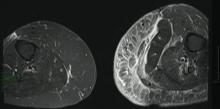

A 68-year-old morbidly obese woman with high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, chronic venous insufficiency, and left leg lymphoedema was referred to our emergency unit. She had pain and circumferential erythema with multiple abscesses of the left leg of 2 weeks’ duration. No history of trauma, ulcer, injection, or animal bite was noted. At the time of presentation she had no fever and vital parameters were normal. Empirical treatment with oral amoxicillin (6 g daily) and amoxicillin-clavulanate (375 mg daily) was started. Forty-eight hours later, inflammation, pain, and abscesses worsened (Figure 1A). Laboratory tests showed an elevated white blood cell count (15.9×109⁄L with 86% neutrophils [reference range, 4.5–11.0×109⁄L]) and an elevated C-reactive protein level (322 mg/L [reference range, <2 mg/L]). Human immunodeficiency virus serology was negative. Needle aspiration of an abscess yielded S marcescens. A second aspiration confirmed the presence of the same organism, wild-type S marcescens, which was resistant to amoxicillin and clavulanic acid, first-generation cephalosporin, and tobramycin but sensitive to piperacillin, third-generation cephalosporins, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, and co-trimoxazole. Intravenous cefepime, a third-generation cephalosporin, was started. During the next 48 hours the patient developed severe sepsis with confusion, acute renal failure (creatinine: 231 µmol/L vs 138 µmol/L at baseline [reference range, 53–106 µmol/L), and worsening of skin lesions. Blood cultures were negative and amikacin was added. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a diffuse inflammatory process involving the skin and subcutaneous tissue that extended to the soleus fascia with no other muscle involvement or deep collection (Figure 2). Surgical debridement of infected tissues was performed (Figure 1B). Histologic examination revealed spreading suppurative inflammation involving the dermis and subcutaneous tissues. Clinical healing was obtained after 21 days of antimicrobial therapy. The debrided area required skin grafting 2 months later (Figure 1C).

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Erythema with multiple abscesses on the left ankle and leg at presentation (A), day 1 following surgical debridement of infected tissues (B), and 2 months later with complete healing following a skin graft (C). |

Comment

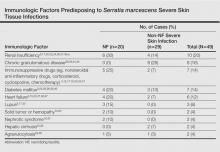

The most common causative bacteria of cellulitis are Staphylococcus aureus and group A β-hemolytic streptococci. Serratia marcescens is a rare but increasingly recognized pathogen of skin and soft tissue infections.5 The proposed pathogenic mechanism for skin necrosis during S marcescens infection is the bacterial production of large proteases (eg, deoxyribonuclease, lipase, gelatinase).6 Injection of purified proteinase from S marcescens into rat skin leads to increased vascular permeability, necrosis of epidermal tissue, dermal inflammation and edema, and infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the subcutaneous fat and muscle.7Serratia marcescens is ubiquitous in soil and water and it also may colonize the respiratory, urinary, and digestive tracts in humans. Cellulitis due to S marcescens secondary to iguana bites8,9 and snake bites10 or leech-borne cellulitis11 suggest that the oral cavity of these animals may be colonized. To date, 49 cases of severe S marcescens skin infections have been described, according to a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Serratia marcescens and skin, cutaneous, soft tissue, and cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis: 20 cases with NF3,12-28 and 29 non-NF cases8-11,29-46 (typical cellulitis presentation [n=8]9,11,35-38,40; abscesses, gumma, or pyoderma gangrenosum–like lesions associated with chronic granulomatous disease in childhood [n=7]29,44,45; painful nodules with secondary abscesses [n=6]31-34,46; acute bullous cellulitis [n=4]8,10,30; secondary infections of ulcers [n=2]35,40; abscesses in immunocompetent patient [n=1]41; and necrotizing skin ulceration [n=1]36). Lower extremities were frequently involved (NF cases, n=13; non-NF cases, n=16). Underlying immunosuppression was observed in 14 NF cases and in 17 non-NF cases. Predisposing immunologic factors are summarized in the Table. Local risk factors, including chronic leg edema, trauma, surgical wound, filler injection, and ulcer, were frequently reported in NF and non-NF cases,16,20,26-28,31,32,34,35,37,38,40,46 including our case. Surgery was required in 19 NF cases and in 7 non-NF cases. Serratia marcescens–mediated NF led to higher mortality (n=12) than non-NF cases (n=1). Other nonsevere clinical manifestations of S marcescens infection reported in the literature included disseminated papular eruptions with human immunodeficiency virus infection42 and trunk folliculitis.43 Our patient had many risk factors, including chronic edema, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, and chronic venous insufficiency. The potential presence of abscesses and necrotic tissue hinders antibiotic penetration at the infection site, and surgery should be systematically considered as early as possible in view of the high mortality rate of S marcescens cellulitis.

Conclusion

Although uncommon, an S marcescens skin infection may be suspected in cases of cellulitis in immunocompromised patients, especially when conventional antibiotics are not effective. Serratia marcescens naturally produces a cephalosporinase that confers resistance to amoxicillin and to amoxicillin associated with clavulanic acid. Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, or imipenem-cilastatin are indicated in cases of S marcescens skin infections, and surgery should be promptly considered if appropriate antibiotic therapy does not lead to rapid clinical improvement.

1. Engel HJ, Collignon PJ, Whiting PT, et al. Serratia sp. bacteremia in Canberra, Australia: a population-based study over 10 years. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:821-824.

2. Brenner DE, Lookingbill DP. Serratia marcescens cellulitis. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1599-1600.

3. Rehman T, Moore TA, Seoane L. Serratia marcescens necrotizing fasciitis presenting as bilateral breast necrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3406-3408.

4. Yu VL. Serratia marcescens: historical perspective and clinical review. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:887-893.

5. Moet GJ, Jones RN, Biedenbach DJ, et al. 2007. Contemporary causes of skin and soft tissue infections in North America, Latin America, and Europe: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1998–2004). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;57:7-13.

6. Aucken HM, Pitt TL. Antibiotic resistance and putative virulence factors of Serratia marcescens with respect to O and K serotypes. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:1105-1113.

7. Conroy MC, Bander NH, Lepow IH. Effect in the rat of intradermal injection of purified proteinases from Streptococcus and Serratia marcescens. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1975;150:801-806.

8. Grim KD, Doherty C, Rosen T. Serratia marcescens bullous cellulitis after iguana bites. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1075-1076.

9. Hsieh S, Babl FE. Serratia marcescens cellulitis following an iguana bite. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1181-1182.

10. Subramani P, Narasimhamurthy GB, Ashokan B, et al. Serratia marcescens: an unusual pathogen associated with snakebite cellulitis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7:152-154.

11. Pereira JA, Greig JR, Liddy H, et al. Leech-borne Serratia marcescens infection following complex hand injury. Br J Plast Surg. 1998;51:640-641.

12. Wen YK. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens: a fatal complication of nephrotic syndrome. Ren Fail. 2012;34:649-652.

13. Prelog T, Jereb M, Cuček I, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens after venous access port implantation in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:e246-e248.

14. Meisel M, Schultz-Coulon HJ. Life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis colli caused by Serratia marcescens [in German]. HNO. 2009;57:1071-1074.

15. Campos GA, Burgos LAM, Fica CA, et al. Fatal necrotizing fasciitis due to Serratia marcescens [in Spanish]. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2007;24:319-322.

16. Bustamante Rodríguez R, Bustamante Rodríguez E, Obón Azuara B. Community-acquired necrotizing fasciitis by Serratia marcescens [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2008;130:198-199.

17. Pascual J, Liaño F, Rivera M, et al. Necrotizing myositis secondary to Serratia marcescens in a renal allograft recipient. Nephron. 1990;55:329-331.

18. Statham MM, Vohra A, Mehta DK, et al. Serratia marcescens causing cervical necrotizing oropharyngitis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:467-473.

19. Rimailho A, Riou B, Richard C, et al. Fulminant necrotizing fasciitis and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:143-146.

20. Huang JW, Fang CT, Hung KY, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens in two patients receiving corticosteroid therapy. J Formos Med Assoc. 1999;98:851-854.

21. Newton CL, deLemos D, Abramo TJ, et al. Cervical necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens in a 2 year old. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:433-435.

22. Curtis CE, Chock S, Henderson T, et al. A fatal case of necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens. Am Surg. 2005;71:228-230.

23. Zipper RP, Bustamante MA, Khatib R. Serratia marcescens: a single pathogen in necrotizing fasciitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:648-649.

24. Liangpunsakul S, Pursell K. Community-acquired necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens: case report and review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:509-510.

25. Vano-Galvan S, Álvarez-Twose I, Moreno-Martín P, et al. Fulminant necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens in an immunosuppressed host. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e57-e58.

26. Majumdar R, Crum-Cianflone NF. Necrotizing fasciitis due to Serratia marcescens: case report and review of the literature [published online October 23, 2015]. Infection. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0855-x.

27. Cope TE, Cope W, Beaumont DM. A case of necrotising fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens: extreme age as functional immunosuppression? Age Ageing. 2013;42:266-268.

28. Lakhani NA, Narsinghani U, Kumar R. Necrotizing fasciitis of the abdominal wall caused by Serratia marcescens. Infect Dis Rep. 2015;157:5774.

29. Friend JC, Hilligoss DM, Marquesen M, et al. Skin ulcers and disseminated abscesses are characteristic of Serratia marcescens infection in older patients with chronic granulomatous disease [published online May 27, 2009]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:164-166.

30. Cooper CL, Wiseman M, Brunham R. Bullous cellulitis caused by Serratia marcescens. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;3:36-38.

31. Langrock ML, Linde HJ, Landthaler M, et al. Leg ulcers and abscesses caused by Serratia marcescens. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:705-707.

32. João AM, Serrano PN, Cachão MP, et al. Recurrent Serratia marcescens cutaneous infection manifesting as painful nodules and ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2 suppl):S55-S57.

33. Friedman DN, Peterson NB, Sumner WT, et al. Spontaneous dermal abscesses and ulcers as a result of Serratia marcescens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S193-S194.

34. Soria X, Bielsa I, Ribera M, et al. Acute dermal abscesses caused by Serratia marcescens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:891-893.

35. Bogaert MA, Hogan DJ, Miller AE Jr. Serratia cellulitis and secondary infection of leg ulcers by Serratia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:565.

36. Gössl M, Eggebrecht H. Necrotizing skin ulceration in antibiotic-induced agranulocytosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1527.

37. Brenner DE, Lookingbill DP. Serratia marcescens cellulitis. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1599-1600.

38. Bonner MJ, Meharg JG Jr. Primary cellulitis due to Serratia marcescens. JAMA. 1983;250:2348-2349.

39. Bornstein PF, Ditto AM, Noskin GA. Serratia marcescens cellulitis in a patient on hemodialysis. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12:374-376.

40. Kaplan H, Sehtman L, Ricover N, et al. Serratia marcescens: cutaneous involvement. preliminary report. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1988;16:305-308.

41. Giráldez P, Mayo E, Pavón P, et al. Skin infection due to Serratia marcescens in an immunocompetent patient [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:236-237.

42. Muñoz-Pérez MA, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, Camacho F. Disseminated papular eruption caused by Serratia marcescens: a new cutaneous manifestation in HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 1996;10:1179-1180.

43. Lehrhoff S, Yost M, Robinson M, et al. Serratia marcescens folliculitis and concomitant acne vulgaris. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:19.

44. Benajiba N, Amrani R, Rkain M, et al. Serratia marcescens cutaneous gumma and chronic septic granulomatosis. Med Mal Infect. 2014;44:39-41.

45. Barbato M, Ragusa G, Civitelli F, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease mimicking early-onset Crohn’s disease with cutaneous manifestations. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:156.

46. Park KY, Seo SJ. Cutaneous Serratia marcescens infection in an immunocompetent patient after filler injection. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:191-192.

A gram-negative bacillus of the Enterobacteriaceae family, Serratia marcescens is an organism known to cause bacteremia, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, endocarditis, meningitis, and septic arthritis.1 Unusual cases of cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis (NF) caused by S marcescens also have been reported.2,3 This entity has been initially described in immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised patients.4 Both community and nosocomial cases also have been reported.3

Case Report

A 68-year-old morbidly obese woman with high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, chronic venous insufficiency, and left leg lymphoedema was referred to our emergency unit. She had pain and circumferential erythema with multiple abscesses of the left leg of 2 weeks’ duration. No history of trauma, ulcer, injection, or animal bite was noted. At the time of presentation she had no fever and vital parameters were normal. Empirical treatment with oral amoxicillin (6 g daily) and amoxicillin-clavulanate (375 mg daily) was started. Forty-eight hours later, inflammation, pain, and abscesses worsened (Figure 1A). Laboratory tests showed an elevated white blood cell count (15.9×109⁄L with 86% neutrophils [reference range, 4.5–11.0×109⁄L]) and an elevated C-reactive protein level (322 mg/L [reference range, <2 mg/L]). Human immunodeficiency virus serology was negative. Needle aspiration of an abscess yielded S marcescens. A second aspiration confirmed the presence of the same organism, wild-type S marcescens, which was resistant to amoxicillin and clavulanic acid, first-generation cephalosporin, and tobramycin but sensitive to piperacillin, third-generation cephalosporins, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, and co-trimoxazole. Intravenous cefepime, a third-generation cephalosporin, was started. During the next 48 hours the patient developed severe sepsis with confusion, acute renal failure (creatinine: 231 µmol/L vs 138 µmol/L at baseline [reference range, 53–106 µmol/L), and worsening of skin lesions. Blood cultures were negative and amikacin was added. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a diffuse inflammatory process involving the skin and subcutaneous tissue that extended to the soleus fascia with no other muscle involvement or deep collection (Figure 2). Surgical debridement of infected tissues was performed (Figure 1B). Histologic examination revealed spreading suppurative inflammation involving the dermis and subcutaneous tissues. Clinical healing was obtained after 21 days of antimicrobial therapy. The debrided area required skin grafting 2 months later (Figure 1C).

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Erythema with multiple abscesses on the left ankle and leg at presentation (A), day 1 following surgical debridement of infected tissues (B), and 2 months later with complete healing following a skin graft (C). |

Comment

The most common causative bacteria of cellulitis are Staphylococcus aureus and group A β-hemolytic streptococci. Serratia marcescens is a rare but increasingly recognized pathogen of skin and soft tissue infections.5 The proposed pathogenic mechanism for skin necrosis during S marcescens infection is the bacterial production of large proteases (eg, deoxyribonuclease, lipase, gelatinase).6 Injection of purified proteinase from S marcescens into rat skin leads to increased vascular permeability, necrosis of epidermal tissue, dermal inflammation and edema, and infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the subcutaneous fat and muscle.7Serratia marcescens is ubiquitous in soil and water and it also may colonize the respiratory, urinary, and digestive tracts in humans. Cellulitis due to S marcescens secondary to iguana bites8,9 and snake bites10 or leech-borne cellulitis11 suggest that the oral cavity of these animals may be colonized. To date, 49 cases of severe S marcescens skin infections have been described, according to a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Serratia marcescens and skin, cutaneous, soft tissue, and cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis: 20 cases with NF3,12-28 and 29 non-NF cases8-11,29-46 (typical cellulitis presentation [n=8]9,11,35-38,40; abscesses, gumma, or pyoderma gangrenosum–like lesions associated with chronic granulomatous disease in childhood [n=7]29,44,45; painful nodules with secondary abscesses [n=6]31-34,46; acute bullous cellulitis [n=4]8,10,30; secondary infections of ulcers [n=2]35,40; abscesses in immunocompetent patient [n=1]41; and necrotizing skin ulceration [n=1]36). Lower extremities were frequently involved (NF cases, n=13; non-NF cases, n=16). Underlying immunosuppression was observed in 14 NF cases and in 17 non-NF cases. Predisposing immunologic factors are summarized in the Table. Local risk factors, including chronic leg edema, trauma, surgical wound, filler injection, and ulcer, were frequently reported in NF and non-NF cases,16,20,26-28,31,32,34,35,37,38,40,46 including our case. Surgery was required in 19 NF cases and in 7 non-NF cases. Serratia marcescens–mediated NF led to higher mortality (n=12) than non-NF cases (n=1). Other nonsevere clinical manifestations of S marcescens infection reported in the literature included disseminated papular eruptions with human immunodeficiency virus infection42 and trunk folliculitis.43 Our patient had many risk factors, including chronic edema, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, and chronic venous insufficiency. The potential presence of abscesses and necrotic tissue hinders antibiotic penetration at the infection site, and surgery should be systematically considered as early as possible in view of the high mortality rate of S marcescens cellulitis.

Conclusion

Although uncommon, an S marcescens skin infection may be suspected in cases of cellulitis in immunocompromised patients, especially when conventional antibiotics are not effective. Serratia marcescens naturally produces a cephalosporinase that confers resistance to amoxicillin and to amoxicillin associated with clavulanic acid. Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, or imipenem-cilastatin are indicated in cases of S marcescens skin infections, and surgery should be promptly considered if appropriate antibiotic therapy does not lead to rapid clinical improvement.

A gram-negative bacillus of the Enterobacteriaceae family, Serratia marcescens is an organism known to cause bacteremia, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, endocarditis, meningitis, and septic arthritis.1 Unusual cases of cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis (NF) caused by S marcescens also have been reported.2,3 This entity has been initially described in immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised patients.4 Both community and nosocomial cases also have been reported.3

Case Report

A 68-year-old morbidly obese woman with high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, chronic venous insufficiency, and left leg lymphoedema was referred to our emergency unit. She had pain and circumferential erythema with multiple abscesses of the left leg of 2 weeks’ duration. No history of trauma, ulcer, injection, or animal bite was noted. At the time of presentation she had no fever and vital parameters were normal. Empirical treatment with oral amoxicillin (6 g daily) and amoxicillin-clavulanate (375 mg daily) was started. Forty-eight hours later, inflammation, pain, and abscesses worsened (Figure 1A). Laboratory tests showed an elevated white blood cell count (15.9×109⁄L with 86% neutrophils [reference range, 4.5–11.0×109⁄L]) and an elevated C-reactive protein level (322 mg/L [reference range, <2 mg/L]). Human immunodeficiency virus serology was negative. Needle aspiration of an abscess yielded S marcescens. A second aspiration confirmed the presence of the same organism, wild-type S marcescens, which was resistant to amoxicillin and clavulanic acid, first-generation cephalosporin, and tobramycin but sensitive to piperacillin, third-generation cephalosporins, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, and co-trimoxazole. Intravenous cefepime, a third-generation cephalosporin, was started. During the next 48 hours the patient developed severe sepsis with confusion, acute renal failure (creatinine: 231 µmol/L vs 138 µmol/L at baseline [reference range, 53–106 µmol/L), and worsening of skin lesions. Blood cultures were negative and amikacin was added. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a diffuse inflammatory process involving the skin and subcutaneous tissue that extended to the soleus fascia with no other muscle involvement or deep collection (Figure 2). Surgical debridement of infected tissues was performed (Figure 1B). Histologic examination revealed spreading suppurative inflammation involving the dermis and subcutaneous tissues. Clinical healing was obtained after 21 days of antimicrobial therapy. The debrided area required skin grafting 2 months later (Figure 1C).

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Erythema with multiple abscesses on the left ankle and leg at presentation (A), day 1 following surgical debridement of infected tissues (B), and 2 months later with complete healing following a skin graft (C). |

Comment

The most common causative bacteria of cellulitis are Staphylococcus aureus and group A β-hemolytic streptococci. Serratia marcescens is a rare but increasingly recognized pathogen of skin and soft tissue infections.5 The proposed pathogenic mechanism for skin necrosis during S marcescens infection is the bacterial production of large proteases (eg, deoxyribonuclease, lipase, gelatinase).6 Injection of purified proteinase from S marcescens into rat skin leads to increased vascular permeability, necrosis of epidermal tissue, dermal inflammation and edema, and infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the subcutaneous fat and muscle.7Serratia marcescens is ubiquitous in soil and water and it also may colonize the respiratory, urinary, and digestive tracts in humans. Cellulitis due to S marcescens secondary to iguana bites8,9 and snake bites10 or leech-borne cellulitis11 suggest that the oral cavity of these animals may be colonized. To date, 49 cases of severe S marcescens skin infections have been described, according to a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Serratia marcescens and skin, cutaneous, soft tissue, and cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis: 20 cases with NF3,12-28 and 29 non-NF cases8-11,29-46 (typical cellulitis presentation [n=8]9,11,35-38,40; abscesses, gumma, or pyoderma gangrenosum–like lesions associated with chronic granulomatous disease in childhood [n=7]29,44,45; painful nodules with secondary abscesses [n=6]31-34,46; acute bullous cellulitis [n=4]8,10,30; secondary infections of ulcers [n=2]35,40; abscesses in immunocompetent patient [n=1]41; and necrotizing skin ulceration [n=1]36). Lower extremities were frequently involved (NF cases, n=13; non-NF cases, n=16). Underlying immunosuppression was observed in 14 NF cases and in 17 non-NF cases. Predisposing immunologic factors are summarized in the Table. Local risk factors, including chronic leg edema, trauma, surgical wound, filler injection, and ulcer, were frequently reported in NF and non-NF cases,16,20,26-28,31,32,34,35,37,38,40,46 including our case. Surgery was required in 19 NF cases and in 7 non-NF cases. Serratia marcescens–mediated NF led to higher mortality (n=12) than non-NF cases (n=1). Other nonsevere clinical manifestations of S marcescens infection reported in the literature included disseminated papular eruptions with human immunodeficiency virus infection42 and trunk folliculitis.43 Our patient had many risk factors, including chronic edema, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, and chronic venous insufficiency. The potential presence of abscesses and necrotic tissue hinders antibiotic penetration at the infection site, and surgery should be systematically considered as early as possible in view of the high mortality rate of S marcescens cellulitis.

Conclusion

Although uncommon, an S marcescens skin infection may be suspected in cases of cellulitis in immunocompromised patients, especially when conventional antibiotics are not effective. Serratia marcescens naturally produces a cephalosporinase that confers resistance to amoxicillin and to amoxicillin associated with clavulanic acid. Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, or imipenem-cilastatin are indicated in cases of S marcescens skin infections, and surgery should be promptly considered if appropriate antibiotic therapy does not lead to rapid clinical improvement.

1. Engel HJ, Collignon PJ, Whiting PT, et al. Serratia sp. bacteremia in Canberra, Australia: a population-based study over 10 years. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:821-824.

2. Brenner DE, Lookingbill DP. Serratia marcescens cellulitis. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1599-1600.

3. Rehman T, Moore TA, Seoane L. Serratia marcescens necrotizing fasciitis presenting as bilateral breast necrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3406-3408.

4. Yu VL. Serratia marcescens: historical perspective and clinical review. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:887-893.

5. Moet GJ, Jones RN, Biedenbach DJ, et al. 2007. Contemporary causes of skin and soft tissue infections in North America, Latin America, and Europe: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1998–2004). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;57:7-13.

6. Aucken HM, Pitt TL. Antibiotic resistance and putative virulence factors of Serratia marcescens with respect to O and K serotypes. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:1105-1113.

7. Conroy MC, Bander NH, Lepow IH. Effect in the rat of intradermal injection of purified proteinases from Streptococcus and Serratia marcescens. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1975;150:801-806.

8. Grim KD, Doherty C, Rosen T. Serratia marcescens bullous cellulitis after iguana bites. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1075-1076.

9. Hsieh S, Babl FE. Serratia marcescens cellulitis following an iguana bite. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1181-1182.

10. Subramani P, Narasimhamurthy GB, Ashokan B, et al. Serratia marcescens: an unusual pathogen associated with snakebite cellulitis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7:152-154.

11. Pereira JA, Greig JR, Liddy H, et al. Leech-borne Serratia marcescens infection following complex hand injury. Br J Plast Surg. 1998;51:640-641.

12. Wen YK. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens: a fatal complication of nephrotic syndrome. Ren Fail. 2012;34:649-652.

13. Prelog T, Jereb M, Cuček I, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens after venous access port implantation in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:e246-e248.

14. Meisel M, Schultz-Coulon HJ. Life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis colli caused by Serratia marcescens [in German]. HNO. 2009;57:1071-1074.

15. Campos GA, Burgos LAM, Fica CA, et al. Fatal necrotizing fasciitis due to Serratia marcescens [in Spanish]. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2007;24:319-322.

16. Bustamante Rodríguez R, Bustamante Rodríguez E, Obón Azuara B. Community-acquired necrotizing fasciitis by Serratia marcescens [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2008;130:198-199.

17. Pascual J, Liaño F, Rivera M, et al. Necrotizing myositis secondary to Serratia marcescens in a renal allograft recipient. Nephron. 1990;55:329-331.

18. Statham MM, Vohra A, Mehta DK, et al. Serratia marcescens causing cervical necrotizing oropharyngitis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:467-473.

19. Rimailho A, Riou B, Richard C, et al. Fulminant necrotizing fasciitis and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:143-146.

20. Huang JW, Fang CT, Hung KY, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens in two patients receiving corticosteroid therapy. J Formos Med Assoc. 1999;98:851-854.

21. Newton CL, deLemos D, Abramo TJ, et al. Cervical necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens in a 2 year old. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:433-435.

22. Curtis CE, Chock S, Henderson T, et al. A fatal case of necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens. Am Surg. 2005;71:228-230.

23. Zipper RP, Bustamante MA, Khatib R. Serratia marcescens: a single pathogen in necrotizing fasciitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:648-649.

24. Liangpunsakul S, Pursell K. Community-acquired necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens: case report and review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:509-510.

25. Vano-Galvan S, Álvarez-Twose I, Moreno-Martín P, et al. Fulminant necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens in an immunosuppressed host. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e57-e58.

26. Majumdar R, Crum-Cianflone NF. Necrotizing fasciitis due to Serratia marcescens: case report and review of the literature [published online October 23, 2015]. Infection. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0855-x.

27. Cope TE, Cope W, Beaumont DM. A case of necrotising fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens: extreme age as functional immunosuppression? Age Ageing. 2013;42:266-268.

28. Lakhani NA, Narsinghani U, Kumar R. Necrotizing fasciitis of the abdominal wall caused by Serratia marcescens. Infect Dis Rep. 2015;157:5774.

29. Friend JC, Hilligoss DM, Marquesen M, et al. Skin ulcers and disseminated abscesses are characteristic of Serratia marcescens infection in older patients with chronic granulomatous disease [published online May 27, 2009]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:164-166.

30. Cooper CL, Wiseman M, Brunham R. Bullous cellulitis caused by Serratia marcescens. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;3:36-38.

31. Langrock ML, Linde HJ, Landthaler M, et al. Leg ulcers and abscesses caused by Serratia marcescens. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:705-707.

32. João AM, Serrano PN, Cachão MP, et al. Recurrent Serratia marcescens cutaneous infection manifesting as painful nodules and ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2 suppl):S55-S57.

33. Friedman DN, Peterson NB, Sumner WT, et al. Spontaneous dermal abscesses and ulcers as a result of Serratia marcescens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S193-S194.

34. Soria X, Bielsa I, Ribera M, et al. Acute dermal abscesses caused by Serratia marcescens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:891-893.

35. Bogaert MA, Hogan DJ, Miller AE Jr. Serratia cellulitis and secondary infection of leg ulcers by Serratia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:565.

36. Gössl M, Eggebrecht H. Necrotizing skin ulceration in antibiotic-induced agranulocytosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1527.

37. Brenner DE, Lookingbill DP. Serratia marcescens cellulitis. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1599-1600.

38. Bonner MJ, Meharg JG Jr. Primary cellulitis due to Serratia marcescens. JAMA. 1983;250:2348-2349.

39. Bornstein PF, Ditto AM, Noskin GA. Serratia marcescens cellulitis in a patient on hemodialysis. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12:374-376.

40. Kaplan H, Sehtman L, Ricover N, et al. Serratia marcescens: cutaneous involvement. preliminary report. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1988;16:305-308.

41. Giráldez P, Mayo E, Pavón P, et al. Skin infection due to Serratia marcescens in an immunocompetent patient [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:236-237.

42. Muñoz-Pérez MA, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, Camacho F. Disseminated papular eruption caused by Serratia marcescens: a new cutaneous manifestation in HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 1996;10:1179-1180.

43. Lehrhoff S, Yost M, Robinson M, et al. Serratia marcescens folliculitis and concomitant acne vulgaris. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:19.

44. Benajiba N, Amrani R, Rkain M, et al. Serratia marcescens cutaneous gumma and chronic septic granulomatosis. Med Mal Infect. 2014;44:39-41.

45. Barbato M, Ragusa G, Civitelli F, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease mimicking early-onset Crohn’s disease with cutaneous manifestations. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:156.

46. Park KY, Seo SJ. Cutaneous Serratia marcescens infection in an immunocompetent patient after filler injection. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:191-192.

1. Engel HJ, Collignon PJ, Whiting PT, et al. Serratia sp. bacteremia in Canberra, Australia: a population-based study over 10 years. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:821-824.

2. Brenner DE, Lookingbill DP. Serratia marcescens cellulitis. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1599-1600.

3. Rehman T, Moore TA, Seoane L. Serratia marcescens necrotizing fasciitis presenting as bilateral breast necrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3406-3408.

4. Yu VL. Serratia marcescens: historical perspective and clinical review. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:887-893.

5. Moet GJ, Jones RN, Biedenbach DJ, et al. 2007. Contemporary causes of skin and soft tissue infections in North America, Latin America, and Europe: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1998–2004). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;57:7-13.

6. Aucken HM, Pitt TL. Antibiotic resistance and putative virulence factors of Serratia marcescens with respect to O and K serotypes. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:1105-1113.

7. Conroy MC, Bander NH, Lepow IH. Effect in the rat of intradermal injection of purified proteinases from Streptococcus and Serratia marcescens. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1975;150:801-806.

8. Grim KD, Doherty C, Rosen T. Serratia marcescens bullous cellulitis after iguana bites. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1075-1076.

9. Hsieh S, Babl FE. Serratia marcescens cellulitis following an iguana bite. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1181-1182.

10. Subramani P, Narasimhamurthy GB, Ashokan B, et al. Serratia marcescens: an unusual pathogen associated with snakebite cellulitis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7:152-154.

11. Pereira JA, Greig JR, Liddy H, et al. Leech-borne Serratia marcescens infection following complex hand injury. Br J Plast Surg. 1998;51:640-641.

12. Wen YK. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens: a fatal complication of nephrotic syndrome. Ren Fail. 2012;34:649-652.

13. Prelog T, Jereb M, Cuček I, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens after venous access port implantation in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:e246-e248.

14. Meisel M, Schultz-Coulon HJ. Life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis colli caused by Serratia marcescens [in German]. HNO. 2009;57:1071-1074.

15. Campos GA, Burgos LAM, Fica CA, et al. Fatal necrotizing fasciitis due to Serratia marcescens [in Spanish]. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2007;24:319-322.

16. Bustamante Rodríguez R, Bustamante Rodríguez E, Obón Azuara B. Community-acquired necrotizing fasciitis by Serratia marcescens [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2008;130:198-199.

17. Pascual J, Liaño F, Rivera M, et al. Necrotizing myositis secondary to Serratia marcescens in a renal allograft recipient. Nephron. 1990;55:329-331.

18. Statham MM, Vohra A, Mehta DK, et al. Serratia marcescens causing cervical necrotizing oropharyngitis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:467-473.

19. Rimailho A, Riou B, Richard C, et al. Fulminant necrotizing fasciitis and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:143-146.

20. Huang JW, Fang CT, Hung KY, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens in two patients receiving corticosteroid therapy. J Formos Med Assoc. 1999;98:851-854.

21. Newton CL, deLemos D, Abramo TJ, et al. Cervical necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens in a 2 year old. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:433-435.

22. Curtis CE, Chock S, Henderson T, et al. A fatal case of necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens. Am Surg. 2005;71:228-230.

23. Zipper RP, Bustamante MA, Khatib R. Serratia marcescens: a single pathogen in necrotizing fasciitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:648-649.

24. Liangpunsakul S, Pursell K. Community-acquired necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens: case report and review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:509-510.

25. Vano-Galvan S, Álvarez-Twose I, Moreno-Martín P, et al. Fulminant necrotizing fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens in an immunosuppressed host. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e57-e58.

26. Majumdar R, Crum-Cianflone NF. Necrotizing fasciitis due to Serratia marcescens: case report and review of the literature [published online October 23, 2015]. Infection. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0855-x.

27. Cope TE, Cope W, Beaumont DM. A case of necrotising fasciitis caused by Serratia marcescens: extreme age as functional immunosuppression? Age Ageing. 2013;42:266-268.

28. Lakhani NA, Narsinghani U, Kumar R. Necrotizing fasciitis of the abdominal wall caused by Serratia marcescens. Infect Dis Rep. 2015;157:5774.

29. Friend JC, Hilligoss DM, Marquesen M, et al. Skin ulcers and disseminated abscesses are characteristic of Serratia marcescens infection in older patients with chronic granulomatous disease [published online May 27, 2009]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:164-166.

30. Cooper CL, Wiseman M, Brunham R. Bullous cellulitis caused by Serratia marcescens. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;3:36-38.

31. Langrock ML, Linde HJ, Landthaler M, et al. Leg ulcers and abscesses caused by Serratia marcescens. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:705-707.

32. João AM, Serrano PN, Cachão MP, et al. Recurrent Serratia marcescens cutaneous infection manifesting as painful nodules and ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2 suppl):S55-S57.

33. Friedman DN, Peterson NB, Sumner WT, et al. Spontaneous dermal abscesses and ulcers as a result of Serratia marcescens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S193-S194.

34. Soria X, Bielsa I, Ribera M, et al. Acute dermal abscesses caused by Serratia marcescens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:891-893.

35. Bogaert MA, Hogan DJ, Miller AE Jr. Serratia cellulitis and secondary infection of leg ulcers by Serratia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:565.

36. Gössl M, Eggebrecht H. Necrotizing skin ulceration in antibiotic-induced agranulocytosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1527.

37. Brenner DE, Lookingbill DP. Serratia marcescens cellulitis. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1599-1600.

38. Bonner MJ, Meharg JG Jr. Primary cellulitis due to Serratia marcescens. JAMA. 1983;250:2348-2349.

39. Bornstein PF, Ditto AM, Noskin GA. Serratia marcescens cellulitis in a patient on hemodialysis. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12:374-376.

40. Kaplan H, Sehtman L, Ricover N, et al. Serratia marcescens: cutaneous involvement. preliminary report. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1988;16:305-308.

41. Giráldez P, Mayo E, Pavón P, et al. Skin infection due to Serratia marcescens in an immunocompetent patient [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:236-237.

42. Muñoz-Pérez MA, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, Camacho F. Disseminated papular eruption caused by Serratia marcescens: a new cutaneous manifestation in HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 1996;10:1179-1180.

43. Lehrhoff S, Yost M, Robinson M, et al. Serratia marcescens folliculitis and concomitant acne vulgaris. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:19.

44. Benajiba N, Amrani R, Rkain M, et al. Serratia marcescens cutaneous gumma and chronic septic granulomatosis. Med Mal Infect. 2014;44:39-41.

45. Barbato M, Ragusa G, Civitelli F, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease mimicking early-onset Crohn’s disease with cutaneous manifestations. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:156.

46. Park KY, Seo SJ. Cutaneous Serratia marcescens infection in an immunocompetent patient after filler injection. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:191-192.

Practice Points

- Serratia marcescens skin infection should be considered in cases of cellulitis in immunocompromised patients when conventional antibiotics are not effective.

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, or imipenem-cilastatin are indicated in cases of S marcescens skin infections, and surgery should be promptly considered.