User login

Late-onset, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

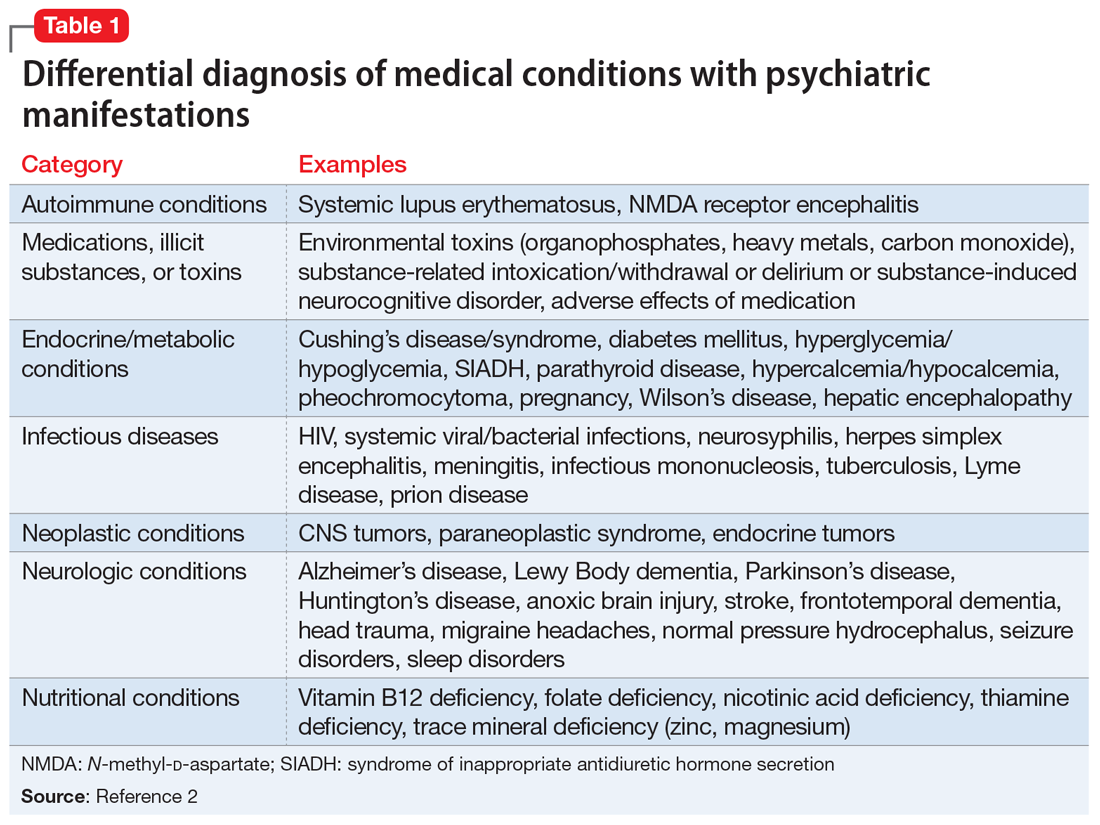

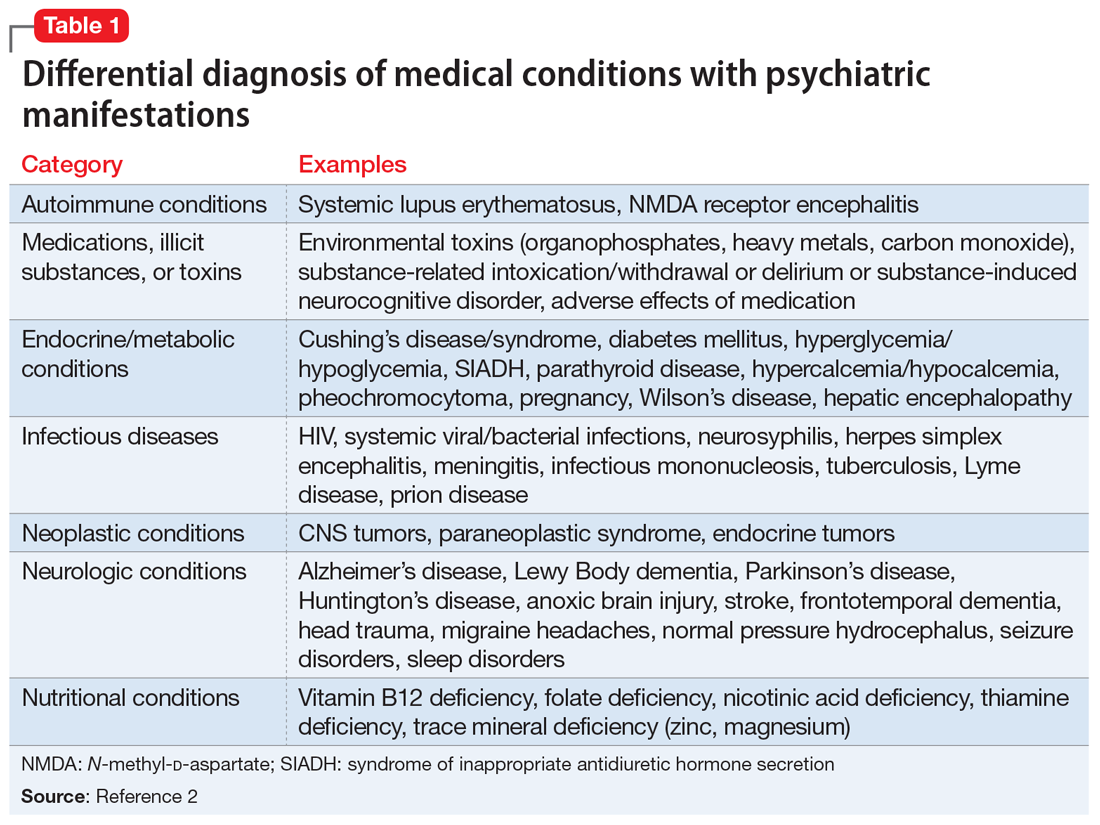

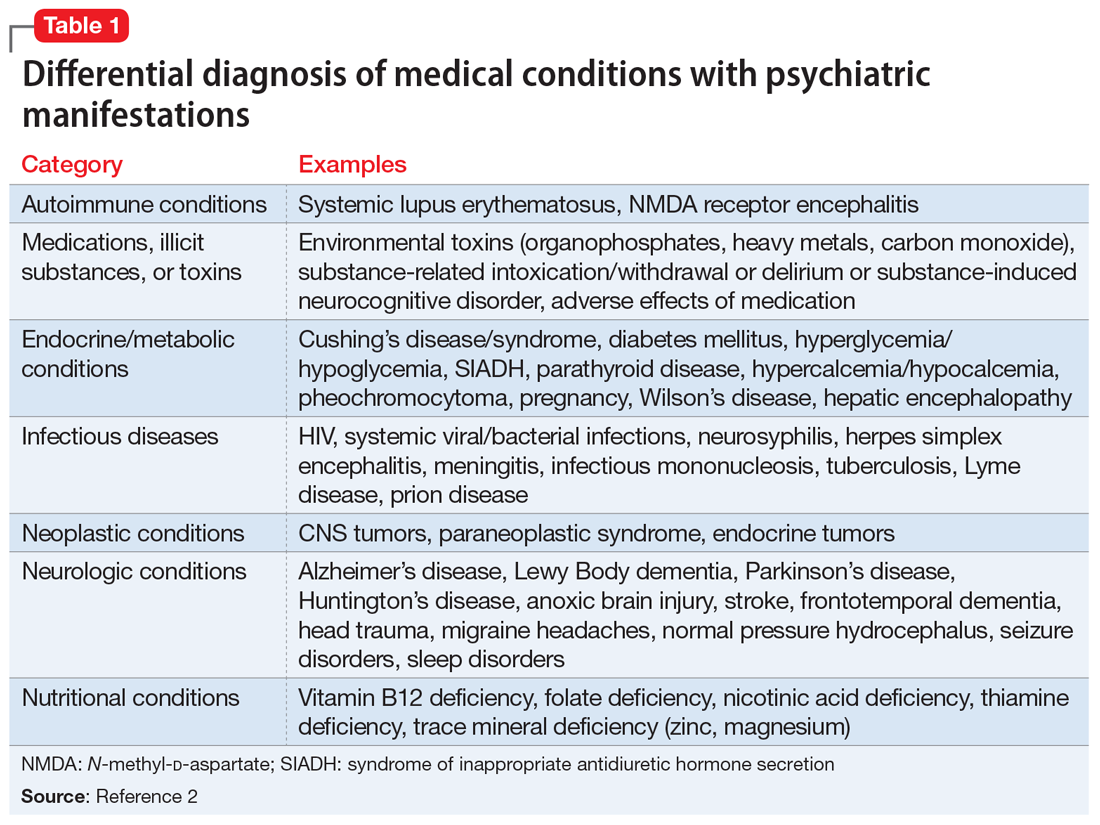

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations

Chronic excess glucocorticoid production is the underlying pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease, which is most commonly caused by an ACTH-producing adenoma.4,5 When these hormones become dysregulated, the result can be over- or underproduction of cortisol, which can lead to physical and psychiatric manifestations.6

Cushing’s disease most commonly manifests with the physical symptoms of centripetal fat deposition, abdominal striae, facial plethora, muscle atrophy, bone density loss, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular complications.5

Hypercortisolism can precipitate anxiety (12% to 79%), mood disorders (50% to 70%), and (less commonly) psychotic disorders; however, in a clinical setting, if a patient presented with one of these as a chief complaint, they would likely first be treated psychiatrically rather than worked up medically for a rare medical condition.5,7-13

Mr. A’s initial bloodwork was unremarkable, but cortisol levels were not obtained at that time because testing for cortisol levels to rule out an underlying medical condition is not routine in patients with depression and anxiety. In Mr. A’s case, a neuroendocrine workup was only ordered once his PCP’s niece coincidentally was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma.

Continue to: For Mr. A...

For Mr. A, Cushing’s disease presented as a psychiatric disorder with anxiety and insomnia that were resistant to numerous psychiatric medications during an 8-month period. If Mr. A’s PCP had not ordered a brain MRI, he may have continued to receive ineffective psychiatric treatment for some time. Many of Mr. A’s physical symptoms were consistent with Cushing’s disease and mental illness, including erectile dysfunction, fatigue, and muscle weakness; however, his 15-pound weight loss pointed more toward psychiatric illness and further disguised his underlying medical diagnosis, because sudden weight gain is commonly seen in Cushing’s disease (Table 24,5,7,9).

TREATMENT Persistent psychiatric symptoms, then finally relief

Four weeks after surgery, Mr. A’s psychiatric symptoms gradually intensify, which prompts him to see a psychiatrist. A mental status examination (MSE) shows that he is well-nourished, with normal activity, appropriate behavior, and coherent thought process, but depressed mood and flat affect. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. He reports that despite being advised to have realistic expectations, he had high hopes that the surgery would lead to remission of all his symptoms, and expresses disappointment that he does not feel “back to normal.”

Six days later, Mr. A’s wife takes him to the hospital. His MSE shows that he has a tense appearance, fidgety activity, depressed and anxious mood, restricted affect, circumstantial thought process, and paranoid delusions that his wife was plotting against him. He says he still is experiencing insomnia. He also discloses having suicidal ideations with a plan and intent to overdose on medication, as well as homicidal ideations about killing his wife and children. Mr. A provides reasons for why he would want to hurt his family, and does not appear to be bothered by these thoughts.

Mr. A is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit and is prescribed quetiapine, 100 mg every night at bedtime. During the next 2 days, quetiapine is titrated to 300 mg every night at bedtime. On hospital Day 3, Mr. A says he is feeling worse than the previous days. He is still having vague suicidal thoughts and feels agitated, guilty, and depressed. To treat these persistent symptoms, quetiapine is further increased to 400 mg every night at bedtime, and he is initiated on bupropion XL, 150 mg, to treat persistent symptoms.

After 1 week of hospitalization, the treatment team meets with Mr. A and his wife, who has been supportive throughout her husband’s hospitalization. During the meeting, they both agree that Mr. A has experienced some improvement because he is no longer having suicidal or homicidal thoughts, but he is still feeling depressed and frustrated by his continued insomnia. Following the meeting, Mr. A’s quetiapine is further increased to 450 mg every night at bedtime to address continued insomnia, and bupropion XL is increased to 300 mg/d to address continued depressive symptoms. During the next few days, his affective symptoms improve; however, his initial insomnia continues, and quetiapine is further increased to 500 mg every night at bedtime.

Continue to: On hospital Day 20...

On hospital Day 20, Mr. A is discharged back to his outpatient psychiatrist and receives quetiapine, 500 mg every night at bedtime, and bupropion XL, 300 mg/d. Although Mr. A’s depression and anxiety continue to be well controlled, his insomnia persists. Sleep hygiene is addressed, and alprazolam, 0.5 mg every night at bedtime, is added to his regimen, which proves to be effective.

OUTCOME A slow remission

After a year of treatment, Mr. A is slowly tapered off of all medications. Two years later, he is in complete remission of all psychiatric symptoms and no longer requires any psychotropic medications.

The authors’ observations

Treatment for hypercortisolism in patients with psychiatric symptoms triggered by glucocorticoid imbalance has typically resulted in a decrease in the severity of their psychiatric symptoms.9,11 A prospective longitudinal study examining 33 patients found that correction of hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome often led to resolution of their psychiatric symptoms, with 87.9% of patients back to baseline within 1 year.14 However, to our knowledge, few reports have described the management of patients whose symptoms are resistant to treatment of hypercortisolism.

In our case, after transsphenoidal resection of an adenoma, Mr. A became suicidal and paranoid, and his anxiety and insomnia also persisted. A possible explanation for the worsening of Mr. A’s symptoms after surgery could be the slow recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and therefore a temporary deficiency in glucocorticoid, which caused an increase in catecholamines, leading to an increase in stress.14 This concept of a “slow recovery” is supported by the fact that Mr. A was successfully weaned off all medication after 1 year of treatment, and achieved complete remission of psychiatric symptoms for >2 years. Furthermore, the severity of Mr. A’s symptoms appeared to correlate with his 24-hour urine cortisol and

Future research should evaluate the utility of screening all patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and/or insomnia for hypercortisolism. Even without other clues to endocrinopathies, serum cortisol levels can be used as a screening tool for diagnosing underlying medical causes in patients with anxiety and depression.2 A greater understanding of the relationship between medical and psychiatric manifestations will allow clinicians to better care for patients. Further research is needed to elucidate the quantitative relationship between cortisol levels and anxiety to evaluate severity, guide treatment planning, and follow treatment response for patients with anxiety. It may be useful to determine the threshold between elevated cortisol levels due to anxiety vs elevated cortisol due to an underlying medical pathology such as Cushing’s disease. Additionally, little research has been conducted to compare how psychiatric symptoms respond to pituitary macroadenoma resection alone, pharmaceutical intervention alone, or a combination of these approaches. It would be beneficial to evaluate these treatment strategies to elucidate the most effective method to reduce psychiatric symptoms in patients with hypercortisolism, and perhaps to reduce the incidence of post-resection worsening of psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: This case was challenging...

This case was challenging because Mr. A did not initially respond to psychiatric intervention, his psychiatric symptoms worsened after transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma, and his symptoms were alleviated only after psychiatric medications were re-initiated following surgery. This case highlights the importance of considering an underlying medically diagnosable and treatable cause of psychiatric illness, and illustrates the complex ongoing management that may be necessary to help a patient with this condition achieve their baseline. Further, Mr. A’s case shows that the absence of response to standard psychiatric therapies should warrant earlier laboratory and/or imaging evaluation prior to or in conjunction with psychiatric referral. Additionally, testing for cortisol levels is not typically done for a patient with treatment-resistant anxiety, and this case highlights the importance of considering hypercortisolism in such circumstances.

Bottom Line

Consider testing cortisol levels in patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and insomnia, because cortisol plays a role in Cushing’s disease and anxiety. The severity of psychiatric manifestations of Cushing’s disease may correlate with cortisol levels. Treatment should focus on symptomatic management and underlying etiology.

Related Resources

- Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

- Rotham J. Cushing’s syndrome: a tale of frequent misdiagnosis. National Center for Health Research. 2020. www.center4research.org/cushings-syndrome-frequent-misdiagnosis/

- Middleman D. Psychiatric issues of Cushing’s patients: coping with Cushing’s. Cushing’s Support and Research Foundation. www.csrf.net/coping-with-cushings/psychiatric-issues-of-cushings-patients/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Diazepam • Valium

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Zolpidem tartrate • Ambien CR

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Neural sciences. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

3. Anfinson TJ, Kathol RG. Screening laboratory evaluation in psychiatric patients: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14(4):248-257.

4. Fehm HL, Voigt KH. Pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease. Pathobiol Annu. 1979;9:225-255.

5. Fujii Y, Mizoguchi Y, Masuoka J, et al. Cushing’s syndrome and psychosis: a case report and literature review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5):18.

6. Raff H, Sharma ST, Nieman LK. Physiological basis for the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adrenal disorders: Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Compr Physiol. 2011;4(2):739-769.

7. Santos A, Resimini E, Pascual JC, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: prevalence diagnosis, and management. Drugs. 2017;77(8):829-842.

8. Arnaldi G, Angeli A, Atkinson B, et al. Diagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5593-5602.

9. Sonino N, Fava GA. Psychosomatic aspects of Cushing’s disease. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67(3):140-146.

10. Loosen PT, Chambliss B, DeBold CR, et al. Psychiatric phenomenology in Cushing’s disease. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1992;25(4):192-198.

11. Kelly WF, Kelly MJ, Faragher B. A prospective study of psychiatric and psychological aspects of Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;45(6):715-720.

12. Katho RG, Delahunt JW, Hannah L. Transition from bipolar affective disorder to intermittent Cushing’s syndrome: case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(5):194-196.

13. Hirsh D, Orr G, Kantarovich V, et al. Cushing’s syndrome presenting as a schizophrenia-like psychotic state. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2000;37(1):46-50.

14. Dorn LD, Burgess ES, Friedman TC, et al. The longitudinal course of psychopathology in Cushing’s syndrome after correction of hypercortisolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(3):912-919.

15. Starkman MN, Schteingart DE, Schork MA. Cushing’s syndrome after treatment: changes in cortisol and ACTH levels, and amelioration of the depressive syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(3):177-178.

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations

Chronic excess glucocorticoid production is the underlying pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease, which is most commonly caused by an ACTH-producing adenoma.4,5 When these hormones become dysregulated, the result can be over- or underproduction of cortisol, which can lead to physical and psychiatric manifestations.6

Cushing’s disease most commonly manifests with the physical symptoms of centripetal fat deposition, abdominal striae, facial plethora, muscle atrophy, bone density loss, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular complications.5

Hypercortisolism can precipitate anxiety (12% to 79%), mood disorders (50% to 70%), and (less commonly) psychotic disorders; however, in a clinical setting, if a patient presented with one of these as a chief complaint, they would likely first be treated psychiatrically rather than worked up medically for a rare medical condition.5,7-13

Mr. A’s initial bloodwork was unremarkable, but cortisol levels were not obtained at that time because testing for cortisol levels to rule out an underlying medical condition is not routine in patients with depression and anxiety. In Mr. A’s case, a neuroendocrine workup was only ordered once his PCP’s niece coincidentally was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma.

Continue to: For Mr. A...

For Mr. A, Cushing’s disease presented as a psychiatric disorder with anxiety and insomnia that were resistant to numerous psychiatric medications during an 8-month period. If Mr. A’s PCP had not ordered a brain MRI, he may have continued to receive ineffective psychiatric treatment for some time. Many of Mr. A’s physical symptoms were consistent with Cushing’s disease and mental illness, including erectile dysfunction, fatigue, and muscle weakness; however, his 15-pound weight loss pointed more toward psychiatric illness and further disguised his underlying medical diagnosis, because sudden weight gain is commonly seen in Cushing’s disease (Table 24,5,7,9).

TREATMENT Persistent psychiatric symptoms, then finally relief

Four weeks after surgery, Mr. A’s psychiatric symptoms gradually intensify, which prompts him to see a psychiatrist. A mental status examination (MSE) shows that he is well-nourished, with normal activity, appropriate behavior, and coherent thought process, but depressed mood and flat affect. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. He reports that despite being advised to have realistic expectations, he had high hopes that the surgery would lead to remission of all his symptoms, and expresses disappointment that he does not feel “back to normal.”

Six days later, Mr. A’s wife takes him to the hospital. His MSE shows that he has a tense appearance, fidgety activity, depressed and anxious mood, restricted affect, circumstantial thought process, and paranoid delusions that his wife was plotting against him. He says he still is experiencing insomnia. He also discloses having suicidal ideations with a plan and intent to overdose on medication, as well as homicidal ideations about killing his wife and children. Mr. A provides reasons for why he would want to hurt his family, and does not appear to be bothered by these thoughts.

Mr. A is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit and is prescribed quetiapine, 100 mg every night at bedtime. During the next 2 days, quetiapine is titrated to 300 mg every night at bedtime. On hospital Day 3, Mr. A says he is feeling worse than the previous days. He is still having vague suicidal thoughts and feels agitated, guilty, and depressed. To treat these persistent symptoms, quetiapine is further increased to 400 mg every night at bedtime, and he is initiated on bupropion XL, 150 mg, to treat persistent symptoms.

After 1 week of hospitalization, the treatment team meets with Mr. A and his wife, who has been supportive throughout her husband’s hospitalization. During the meeting, they both agree that Mr. A has experienced some improvement because he is no longer having suicidal or homicidal thoughts, but he is still feeling depressed and frustrated by his continued insomnia. Following the meeting, Mr. A’s quetiapine is further increased to 450 mg every night at bedtime to address continued insomnia, and bupropion XL is increased to 300 mg/d to address continued depressive symptoms. During the next few days, his affective symptoms improve; however, his initial insomnia continues, and quetiapine is further increased to 500 mg every night at bedtime.

Continue to: On hospital Day 20...

On hospital Day 20, Mr. A is discharged back to his outpatient psychiatrist and receives quetiapine, 500 mg every night at bedtime, and bupropion XL, 300 mg/d. Although Mr. A’s depression and anxiety continue to be well controlled, his insomnia persists. Sleep hygiene is addressed, and alprazolam, 0.5 mg every night at bedtime, is added to his regimen, which proves to be effective.

OUTCOME A slow remission

After a year of treatment, Mr. A is slowly tapered off of all medications. Two years later, he is in complete remission of all psychiatric symptoms and no longer requires any psychotropic medications.

The authors’ observations

Treatment for hypercortisolism in patients with psychiatric symptoms triggered by glucocorticoid imbalance has typically resulted in a decrease in the severity of their psychiatric symptoms.9,11 A prospective longitudinal study examining 33 patients found that correction of hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome often led to resolution of their psychiatric symptoms, with 87.9% of patients back to baseline within 1 year.14 However, to our knowledge, few reports have described the management of patients whose symptoms are resistant to treatment of hypercortisolism.

In our case, after transsphenoidal resection of an adenoma, Mr. A became suicidal and paranoid, and his anxiety and insomnia also persisted. A possible explanation for the worsening of Mr. A’s symptoms after surgery could be the slow recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and therefore a temporary deficiency in glucocorticoid, which caused an increase in catecholamines, leading to an increase in stress.14 This concept of a “slow recovery” is supported by the fact that Mr. A was successfully weaned off all medication after 1 year of treatment, and achieved complete remission of psychiatric symptoms for >2 years. Furthermore, the severity of Mr. A’s symptoms appeared to correlate with his 24-hour urine cortisol and

Future research should evaluate the utility of screening all patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and/or insomnia for hypercortisolism. Even without other clues to endocrinopathies, serum cortisol levels can be used as a screening tool for diagnosing underlying medical causes in patients with anxiety and depression.2 A greater understanding of the relationship between medical and psychiatric manifestations will allow clinicians to better care for patients. Further research is needed to elucidate the quantitative relationship between cortisol levels and anxiety to evaluate severity, guide treatment planning, and follow treatment response for patients with anxiety. It may be useful to determine the threshold between elevated cortisol levels due to anxiety vs elevated cortisol due to an underlying medical pathology such as Cushing’s disease. Additionally, little research has been conducted to compare how psychiatric symptoms respond to pituitary macroadenoma resection alone, pharmaceutical intervention alone, or a combination of these approaches. It would be beneficial to evaluate these treatment strategies to elucidate the most effective method to reduce psychiatric symptoms in patients with hypercortisolism, and perhaps to reduce the incidence of post-resection worsening of psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: This case was challenging...

This case was challenging because Mr. A did not initially respond to psychiatric intervention, his psychiatric symptoms worsened after transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma, and his symptoms were alleviated only after psychiatric medications were re-initiated following surgery. This case highlights the importance of considering an underlying medically diagnosable and treatable cause of psychiatric illness, and illustrates the complex ongoing management that may be necessary to help a patient with this condition achieve their baseline. Further, Mr. A’s case shows that the absence of response to standard psychiatric therapies should warrant earlier laboratory and/or imaging evaluation prior to or in conjunction with psychiatric referral. Additionally, testing for cortisol levels is not typically done for a patient with treatment-resistant anxiety, and this case highlights the importance of considering hypercortisolism in such circumstances.

Bottom Line

Consider testing cortisol levels in patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and insomnia, because cortisol plays a role in Cushing’s disease and anxiety. The severity of psychiatric manifestations of Cushing’s disease may correlate with cortisol levels. Treatment should focus on symptomatic management and underlying etiology.

Related Resources

- Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

- Rotham J. Cushing’s syndrome: a tale of frequent misdiagnosis. National Center for Health Research. 2020. www.center4research.org/cushings-syndrome-frequent-misdiagnosis/

- Middleman D. Psychiatric issues of Cushing’s patients: coping with Cushing’s. Cushing’s Support and Research Foundation. www.csrf.net/coping-with-cushings/psychiatric-issues-of-cushings-patients/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Diazepam • Valium

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Zolpidem tartrate • Ambien CR

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations

Chronic excess glucocorticoid production is the underlying pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease, which is most commonly caused by an ACTH-producing adenoma.4,5 When these hormones become dysregulated, the result can be over- or underproduction of cortisol, which can lead to physical and psychiatric manifestations.6

Cushing’s disease most commonly manifests with the physical symptoms of centripetal fat deposition, abdominal striae, facial plethora, muscle atrophy, bone density loss, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular complications.5

Hypercortisolism can precipitate anxiety (12% to 79%), mood disorders (50% to 70%), and (less commonly) psychotic disorders; however, in a clinical setting, if a patient presented with one of these as a chief complaint, they would likely first be treated psychiatrically rather than worked up medically for a rare medical condition.5,7-13

Mr. A’s initial bloodwork was unremarkable, but cortisol levels were not obtained at that time because testing for cortisol levels to rule out an underlying medical condition is not routine in patients with depression and anxiety. In Mr. A’s case, a neuroendocrine workup was only ordered once his PCP’s niece coincidentally was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma.

Continue to: For Mr. A...

For Mr. A, Cushing’s disease presented as a psychiatric disorder with anxiety and insomnia that were resistant to numerous psychiatric medications during an 8-month period. If Mr. A’s PCP had not ordered a brain MRI, he may have continued to receive ineffective psychiatric treatment for some time. Many of Mr. A’s physical symptoms were consistent with Cushing’s disease and mental illness, including erectile dysfunction, fatigue, and muscle weakness; however, his 15-pound weight loss pointed more toward psychiatric illness and further disguised his underlying medical diagnosis, because sudden weight gain is commonly seen in Cushing’s disease (Table 24,5,7,9).

TREATMENT Persistent psychiatric symptoms, then finally relief

Four weeks after surgery, Mr. A’s psychiatric symptoms gradually intensify, which prompts him to see a psychiatrist. A mental status examination (MSE) shows that he is well-nourished, with normal activity, appropriate behavior, and coherent thought process, but depressed mood and flat affect. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. He reports that despite being advised to have realistic expectations, he had high hopes that the surgery would lead to remission of all his symptoms, and expresses disappointment that he does not feel “back to normal.”

Six days later, Mr. A’s wife takes him to the hospital. His MSE shows that he has a tense appearance, fidgety activity, depressed and anxious mood, restricted affect, circumstantial thought process, and paranoid delusions that his wife was plotting against him. He says he still is experiencing insomnia. He also discloses having suicidal ideations with a plan and intent to overdose on medication, as well as homicidal ideations about killing his wife and children. Mr. A provides reasons for why he would want to hurt his family, and does not appear to be bothered by these thoughts.

Mr. A is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit and is prescribed quetiapine, 100 mg every night at bedtime. During the next 2 days, quetiapine is titrated to 300 mg every night at bedtime. On hospital Day 3, Mr. A says he is feeling worse than the previous days. He is still having vague suicidal thoughts and feels agitated, guilty, and depressed. To treat these persistent symptoms, quetiapine is further increased to 400 mg every night at bedtime, and he is initiated on bupropion XL, 150 mg, to treat persistent symptoms.

After 1 week of hospitalization, the treatment team meets with Mr. A and his wife, who has been supportive throughout her husband’s hospitalization. During the meeting, they both agree that Mr. A has experienced some improvement because he is no longer having suicidal or homicidal thoughts, but he is still feeling depressed and frustrated by his continued insomnia. Following the meeting, Mr. A’s quetiapine is further increased to 450 mg every night at bedtime to address continued insomnia, and bupropion XL is increased to 300 mg/d to address continued depressive symptoms. During the next few days, his affective symptoms improve; however, his initial insomnia continues, and quetiapine is further increased to 500 mg every night at bedtime.

Continue to: On hospital Day 20...

On hospital Day 20, Mr. A is discharged back to his outpatient psychiatrist and receives quetiapine, 500 mg every night at bedtime, and bupropion XL, 300 mg/d. Although Mr. A’s depression and anxiety continue to be well controlled, his insomnia persists. Sleep hygiene is addressed, and alprazolam, 0.5 mg every night at bedtime, is added to his regimen, which proves to be effective.

OUTCOME A slow remission

After a year of treatment, Mr. A is slowly tapered off of all medications. Two years later, he is in complete remission of all psychiatric symptoms and no longer requires any psychotropic medications.

The authors’ observations

Treatment for hypercortisolism in patients with psychiatric symptoms triggered by glucocorticoid imbalance has typically resulted in a decrease in the severity of their psychiatric symptoms.9,11 A prospective longitudinal study examining 33 patients found that correction of hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome often led to resolution of their psychiatric symptoms, with 87.9% of patients back to baseline within 1 year.14 However, to our knowledge, few reports have described the management of patients whose symptoms are resistant to treatment of hypercortisolism.

In our case, after transsphenoidal resection of an adenoma, Mr. A became suicidal and paranoid, and his anxiety and insomnia also persisted. A possible explanation for the worsening of Mr. A’s symptoms after surgery could be the slow recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and therefore a temporary deficiency in glucocorticoid, which caused an increase in catecholamines, leading to an increase in stress.14 This concept of a “slow recovery” is supported by the fact that Mr. A was successfully weaned off all medication after 1 year of treatment, and achieved complete remission of psychiatric symptoms for >2 years. Furthermore, the severity of Mr. A’s symptoms appeared to correlate with his 24-hour urine cortisol and

Future research should evaluate the utility of screening all patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and/or insomnia for hypercortisolism. Even without other clues to endocrinopathies, serum cortisol levels can be used as a screening tool for diagnosing underlying medical causes in patients with anxiety and depression.2 A greater understanding of the relationship between medical and psychiatric manifestations will allow clinicians to better care for patients. Further research is needed to elucidate the quantitative relationship between cortisol levels and anxiety to evaluate severity, guide treatment planning, and follow treatment response for patients with anxiety. It may be useful to determine the threshold between elevated cortisol levels due to anxiety vs elevated cortisol due to an underlying medical pathology such as Cushing’s disease. Additionally, little research has been conducted to compare how psychiatric symptoms respond to pituitary macroadenoma resection alone, pharmaceutical intervention alone, or a combination of these approaches. It would be beneficial to evaluate these treatment strategies to elucidate the most effective method to reduce psychiatric symptoms in patients with hypercortisolism, and perhaps to reduce the incidence of post-resection worsening of psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: This case was challenging...

This case was challenging because Mr. A did not initially respond to psychiatric intervention, his psychiatric symptoms worsened after transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma, and his symptoms were alleviated only after psychiatric medications were re-initiated following surgery. This case highlights the importance of considering an underlying medically diagnosable and treatable cause of psychiatric illness, and illustrates the complex ongoing management that may be necessary to help a patient with this condition achieve their baseline. Further, Mr. A’s case shows that the absence of response to standard psychiatric therapies should warrant earlier laboratory and/or imaging evaluation prior to or in conjunction with psychiatric referral. Additionally, testing for cortisol levels is not typically done for a patient with treatment-resistant anxiety, and this case highlights the importance of considering hypercortisolism in such circumstances.

Bottom Line

Consider testing cortisol levels in patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and insomnia, because cortisol plays a role in Cushing’s disease and anxiety. The severity of psychiatric manifestations of Cushing’s disease may correlate with cortisol levels. Treatment should focus on symptomatic management and underlying etiology.

Related Resources

- Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

- Rotham J. Cushing’s syndrome: a tale of frequent misdiagnosis. National Center for Health Research. 2020. www.center4research.org/cushings-syndrome-frequent-misdiagnosis/

- Middleman D. Psychiatric issues of Cushing’s patients: coping with Cushing’s. Cushing’s Support and Research Foundation. www.csrf.net/coping-with-cushings/psychiatric-issues-of-cushings-patients/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Diazepam • Valium

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Zolpidem tartrate • Ambien CR

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Neural sciences. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

3. Anfinson TJ, Kathol RG. Screening laboratory evaluation in psychiatric patients: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14(4):248-257.

4. Fehm HL, Voigt KH. Pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease. Pathobiol Annu. 1979;9:225-255.

5. Fujii Y, Mizoguchi Y, Masuoka J, et al. Cushing’s syndrome and psychosis: a case report and literature review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5):18.

6. Raff H, Sharma ST, Nieman LK. Physiological basis for the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adrenal disorders: Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Compr Physiol. 2011;4(2):739-769.

7. Santos A, Resimini E, Pascual JC, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: prevalence diagnosis, and management. Drugs. 2017;77(8):829-842.

8. Arnaldi G, Angeli A, Atkinson B, et al. Diagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5593-5602.

9. Sonino N, Fava GA. Psychosomatic aspects of Cushing’s disease. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67(3):140-146.

10. Loosen PT, Chambliss B, DeBold CR, et al. Psychiatric phenomenology in Cushing’s disease. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1992;25(4):192-198.

11. Kelly WF, Kelly MJ, Faragher B. A prospective study of psychiatric and psychological aspects of Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;45(6):715-720.

12. Katho RG, Delahunt JW, Hannah L. Transition from bipolar affective disorder to intermittent Cushing’s syndrome: case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(5):194-196.

13. Hirsh D, Orr G, Kantarovich V, et al. Cushing’s syndrome presenting as a schizophrenia-like psychotic state. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2000;37(1):46-50.

14. Dorn LD, Burgess ES, Friedman TC, et al. The longitudinal course of psychopathology in Cushing’s syndrome after correction of hypercortisolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(3):912-919.

15. Starkman MN, Schteingart DE, Schork MA. Cushing’s syndrome after treatment: changes in cortisol and ACTH levels, and amelioration of the depressive syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(3):177-178.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Neural sciences. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

3. Anfinson TJ, Kathol RG. Screening laboratory evaluation in psychiatric patients: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14(4):248-257.

4. Fehm HL, Voigt KH. Pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease. Pathobiol Annu. 1979;9:225-255.

5. Fujii Y, Mizoguchi Y, Masuoka J, et al. Cushing’s syndrome and psychosis: a case report and literature review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5):18.

6. Raff H, Sharma ST, Nieman LK. Physiological basis for the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adrenal disorders: Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Compr Physiol. 2011;4(2):739-769.

7. Santos A, Resimini E, Pascual JC, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: prevalence diagnosis, and management. Drugs. 2017;77(8):829-842.

8. Arnaldi G, Angeli A, Atkinson B, et al. Diagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5593-5602.

9. Sonino N, Fava GA. Psychosomatic aspects of Cushing’s disease. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67(3):140-146.

10. Loosen PT, Chambliss B, DeBold CR, et al. Psychiatric phenomenology in Cushing’s disease. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1992;25(4):192-198.

11. Kelly WF, Kelly MJ, Faragher B. A prospective study of psychiatric and psychological aspects of Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;45(6):715-720.

12. Katho RG, Delahunt JW, Hannah L. Transition from bipolar affective disorder to intermittent Cushing’s syndrome: case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(5):194-196.

13. Hirsh D, Orr G, Kantarovich V, et al. Cushing’s syndrome presenting as a schizophrenia-like psychotic state. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2000;37(1):46-50.

14. Dorn LD, Burgess ES, Friedman TC, et al. The longitudinal course of psychopathology in Cushing’s syndrome after correction of hypercortisolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(3):912-919.

15. Starkman MN, Schteingart DE, Schork MA. Cushing’s syndrome after treatment: changes in cortisol and ACTH levels, and amelioration of the depressive syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(3):177-178.

Nothing up his sleeve: Decompensation after bariatric surgery

CASE Sudden-onset low mood

Mr. G, age 64, is obese (body mass index [BMI] 37 kg/m2) and has a history of schizoaffective disorder. He is recovering from a sleeve gastrectomy, a surgical weight-loss procedure in which a large portion of the stomach is removed. Seven weeks after his surgery, he experiences a sudden onset of “low mood” and fears that he will become suicidal; he has a history of suicide attempts. Mr. G calls his long-term outpatient clinic and is advised to go to the emergency department (ED).

For years, Mr. G had been stable in a group home setting, and had always been adherent to treatment and forthcoming about his medications with both his bariatric surgeon and psychiatrist. Within the last month, he had been seen at the clinic, had no psychiatric symptoms, and was recovering well from the sleeve gastrectomy.

HISTORY A stable regimen

Mr. G’s psychiatric symptoms initially developed when he was in his 20s, during a time in which he reported using “a lot of drugs.” He had multiple suicide attempts, and multiple inpatient and outpatient treatments. He was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder.

Mr. G has been stable on medications for the last 2 years. His outpatient psychotropic regimen is divalproex sodium extended-release (ER), 2,500 mg every night at bedtime; iloperidone, 8 mg twice a day; escitalopram, 10 mg/d; and mirtazapine, 30 mg every night at bedtime.

In the group home, Mr. G spends his days socializing, studying philosophy, and writing essays. He hopes to find a job in the craftsman industry.

Mr. G’s medical history includes obesity (BMI: 37 kg/m2). Since the surgery, he has been receiving omeprazole, 40 mg/d, a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), to decrease the amount of acid in his stomach. Three weeks after surgery, he had an unremarkable postoperative outpatient psychiatry visit. Divalproex sodium ER was maintained at the pre-surgical dose of 2,500 mg/d.

EVALUATION Depressed and frightened

In the ED, Mr. G’s vitals are normal, but his serum valproic acid (VPA) level is 33.68 µg/mL (therapeutic range: 50 to 125 µg/mL), despite being compliant with treatment. Mr. G is discharged from the ED and told to follow up with his outpatient psychiatrist the next day.

Continue to: At his outpatient psychiatry appointment...

At his outpatient psychiatry appointment, Mr. G’s vital signs are normal, but he reports increasing depression and worsened mood. On mental status examination, Mr. G’s appearance is well groomed, and no agitation nor fidgeting are observed. His behavior is cooperative but somewhat disorganized. He is perseverative on “feeling so low.” He has poor eye contact, which is unusual for him. Mr. G’s speech is loud compared with his baseline. Affect is congruent to mood, which he describes as “depressed and frightened.” He is also noted to be irritable. His thought process is abstract and tangential, which is within his baseline. Mr. G’s thought content is fearful and negativistic, despite his usual positivity and optimism. He denies hallucinations and is oriented to time, place, and person. His judgment, attention, and memory are all within normal limits.

[polldaddy:10790537]

The authors’ observations

The psychiatrist rules out malingering/nonadherence due to Mr. G’s long history of treatment compliance, as evidenced by his past symptom control and therapeutic serum VPA levels. Mr. G was compliant with his postoperative appointments and has been healing well. Therefore, the treatment team believed that Mr. G’s intense and acute decompensation had to be related to a recent change. The notable changes in Mr. G’s case included his sleeve gastrectomy, and the addition of omeprazole to his medication regimen.

The treatment team observed that Mr. G had a long history of compliance with his medications and his symptoms were consistent with a low serum VPA level, which led to the conclusion that the low serum VPA level measured while he was in the ED was likely accurate. This prompted the team to consider Mr. G’s recent surgery. It is well documented that some bariatric surgeries can cause poor absorption of certain vitamins, minerals, and medications. However, Mr. G had a sleeve gastrectomy, which preserves absorption. At this point, the team considered if the patient’s recent medication change was the source of his low VPA level.

The psychiatrist concluded that the issue must have been with the addition of omeprazole because Mr. G’s sleeve gastrectomy was noneventful, he was healing well and being closely monitored by his bariatric surgeon, and this type of surgery preserves absorption. Fortunately, Mr. G was a good historian and had informed his psychiatrist about the addition of omeprazole after his sleeve gastrectomy. The psychiatrist knew acidity was important for the absorption of some medications. Although she was unsure as to whether the problem was a lack of absorption or lack of delivery, the psychiatrist knew a medication change was necessary to raise Mr. G’s serum VPA levels.

TREATMENT A change in divalproex formulation

The psychiatrist switches Mr. G’s formulation of divalproex sodium ER, 2,500 mg/d, to valproic acid immediate-release (IR) liquid capsules. He receives a total daily dose of 2,500 mg, but the dosage is split into 3 times a day. The omeprazole is continued to maintain the postoperative healing process, and he receives his other medications as well (iloperidone, 8 mg twice a day; escitalopram, 10 mg/d; and mirtazapine, 30 mg every night at bedtime).

[polldaddy:10790540]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

The key component to creating a treatment plan for Mr. G centered on understanding drug metabolism and delivery. Acidity plays a role in dissolution of many medications, which led the team to surmise that the PPI, omeprazole, was the culprit. Through research, they understood that the divalproex sodium ER formulation needed a more acidic environment to dissolve, and therefore, an IR formulation was needed.

Different formulations, different characteristics

Medications can be produced in different formulations such as IR, delayed-release (DR), and ER formulations. Different formulations may contain the same medication at identical strengths; however, they may not be bioequivalent and should be titrated based on both the properties of the medication and the release type.1

Immediate-release formulations are developed to dissolve without delaying or prolonging absorption of the medication. These formulations typically include “superdisintegrants” containing croscarmellose sodium2 so that they disintegrate, de-aggregate, and/or dissolve when they come into contact with water or the gastrointestinal tract.3-7

Delayed-release formulations rely on the gastrointestinal pH to release the medication after a certain amount of time has elapsed due to the enteric coating surrounding the tablet. This enteric coating prevents gastric mucosa/gastric juices from inactivating an acid-labile medication.8

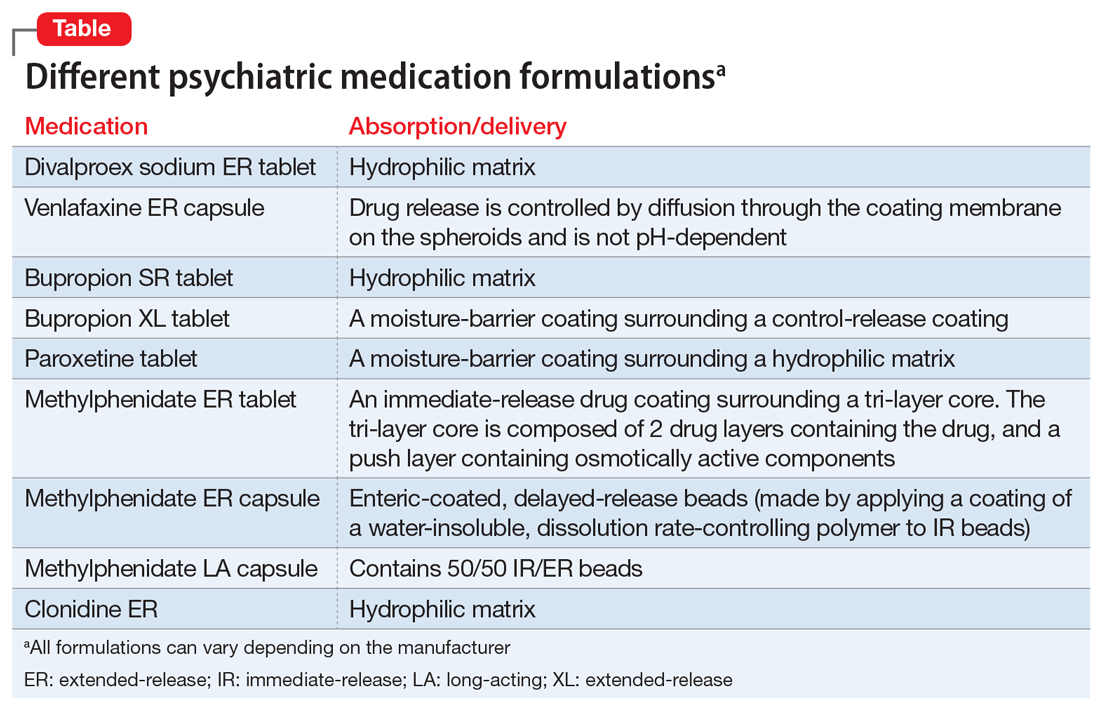

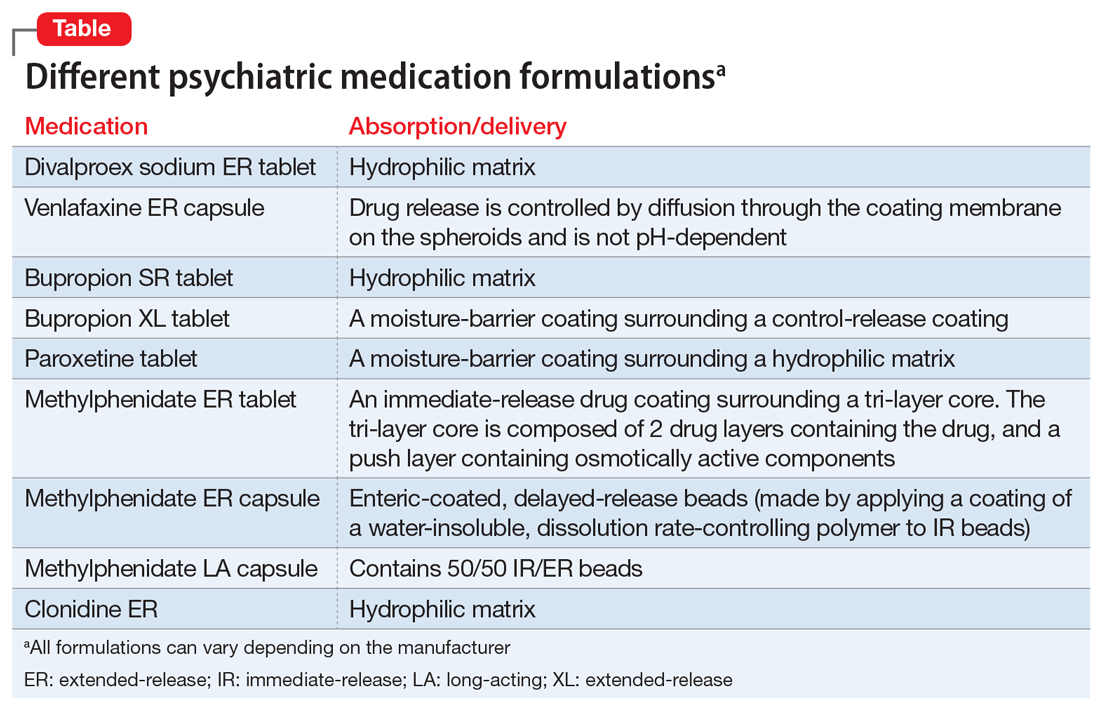

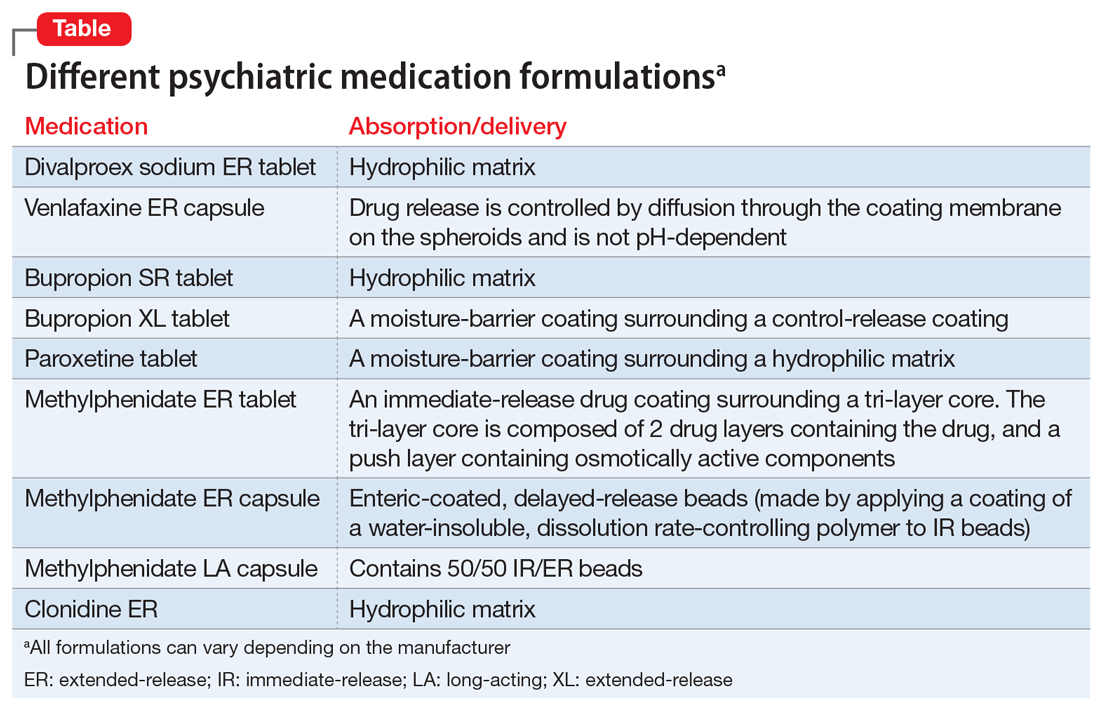

Extended-release formulations, such as the divalproex sodium ER that was originally prescribed to Mr. G, are designed to release the medication in a controlled manner over an extended period of time, and at a predetermined rate and location following administration.8-9 The advantage of this type of formulation is that it can be used to reduce dose frequency and improve adherence.10 Extended-release formulations are designed to minimize fluctuations in serum drug concentration between doses,11 thereby reducing the risk of adverse effects.12,13 A list of some common extended-release psychiatric medications is shown in the Table.

Continue to: The 5 oral formulations...

The 5 oral formulations of medications that contain valproic acid include:

- syrup

- capsule

- sprinkle

- enteric-coated delayed-release and extended-release

A parenteral form via IV is available for patients who are unable to swallow.

Absorption vs delivery

Any gastric bypass surgery can have postoperative complications, one of which can include absorption deficiencies of vitamins and minerals. Sleeve gastrectomy has the least amount of absorption-related nutritional deficiencies.14 Additionally, this procedure preserves the stomach’s ability to produce gastric acid. Therefore, regardless of formulation, there should be no initial postsurgical need to change psychotropic medication formulations. However, because VPA is related to B-vitamin deficiency, supplementation can be considered.

Omeprazole is a PPI that increases pH in the stomach and is often prescribed to promote healing of gastric surgery. However, in Mr. G’s case, omeprazole created a non-acidic environment in his stomach, which prevented the divalproex sodium ER formulation from being dissolved and the medication from being delivered. Mr. G’s absorption ability was preserved, which was confirmed by his rapid recovery and increased serum VPA levels once he was switched to the IR formulation. There is no literature supporting a recommended length of time a patient can receive omeprazole therapy for sleeve gastrectomy; this is at the surgeon’s discretion. Mr. G’s prescription for omeprazole was for 3 months.

Proper valproate dosing

In Mr. G’s case, it could be hypothesized that the VPA dosing was incorrect. For mood disorders, oral VPA dosing is 25 mg/kg/d. Mr. G lost 40 pounds, which would translate to a 450-mg reduction in dose. Despite maintaining his original dose, his serum VPA levels decreased by almost 50% and could not be attributed to trough measurement. In this case, Mr. G was prescribed a higher dose than needed given his weight loss.

Continue to: Divalproex sodium ER...

Divalproex sodium ER is a hydrophilic matrix tablet that requires a low pH to dissolve. Switching to an IR formulation bypassed the need for a low pH and the VPA was delivered and absorbed. Mr. G was always able to absorb the medication, but only when delivered. The Table lists other psychiatric medications that clinicians should be aware of that utilize similar hydrophilic matrix technology to slowly release medications through the gastrointestinal tract and also require low pH to release the medication from the tablet.

OUTCOME Stable once again

Two and a half weeks after his medication formulation is changed from divalproex sodium ER to IR, Mr. G shows improvement in his symptoms. His serum VPA level is 52 µg/mL, which is within therapeutic limits. He continues receiving his previous medications as well. He reports “feeling much better” and denies having any depressive symptoms nor anxiety. Mr. G is able to maintain eye contact, and has positive thought content, improved organization of thinking, and retained abstraction.

Bottom Line

All medication changes should be identified at each visit. Many extended-release psychiatric medications require lower pH to release the medication from the tablet. When evaluating nonresponse to psychotropic medications, anything that affects pH in the stomach should be considered.

Related Resources

- Monte SV, Russo KM, Mustafa E. Impact of sleeve gastrectomy on psychiatric medication use and symptoms. J Obes. 2018; 2018:8532602. doi: 10.1155/2018/8532602

- Qiu Y, Zhou D. Understanding design and development of modified release solid oral dosage forms. J Validation Technol. 2011;17(2):23-32.

- ObesityHelp, Inc. https://www.obesityhelp.com/medications-after-bariatric-surgery-wls/

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Clonidine ER • Kapvay

Divalproex sodium extended- release tablets • Depakote ER

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Methylphenidate ER tablet • Concerta

Methylphenidate ER capsule • Metadate, Jornay

Methylphenidate LA capsule • Ritalin LA

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Omeprazole • Prilosec, Zegerid

Paroxetine • Paxil

Valproic acid immediate- release capsules and solution • Depakene

Valproate sodium IV • Depacon

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Wheless JW, Phelps SJ. A clinician’s guide to oral extended-release drug delivery systems in epilepsy. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2018;23(4):277-292.

2. Jaimini M, Ranga S, Kumar A, et al. A review on immediate release drug delivery system by using design of experiment. J Drug Discov Therap. 2013;1(12):21-27.

3. Bhandari N, Kumar A, Choudhary A, et al. A review on immediate release drug delivery system. Int Res J Pharm App Sci. 2014;49(1):78-87.

4. Eatock J, Baker GA. Managing patient adherence and quality of life in epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(1):117-131.

5. Manjunath R, Davis KL, Candrilli SD, et al. Association of antiepileptic drug nonadherence with risk of seizures in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14(2):372-378.

6. Samsonsen C, Reimers A, Bråthen G, et al. Nonadherence to treatment causing acute hospitalizations in people with epilepsy: an observational, prospective study. Epilepsia. 2014;55(11):e125-e128. doi: 10.1111/epi.12801

7. Mangal M, Thakral S, Goswami M, et al. Superdisintegrants: an updated review. Int Pharmacy Pharmaceut Sci Res. 2012;2(2):26-35.

8. Tablets. United States Pharmacopeia. Accessed January 21, 2021. http://www.pharmacopeia.cn/v29240/usp29nf24s0_c1151s87.html

9. Holquist C, Fava W. FDA safety page: delayed- vs. extended-release Rxs. Drug Topics. Published July 23, 2007. Accessed January 21, 2021. https://www.drugtopics.com/view/fda-safety-page-delayed-release-vs-extended-release-rxs

10. Qiu Y, Zhou D. Understanding design and development of modified release solid oral dosage forms. J Validation Technol. 2011;17(2):23-32.

11. Perucca E. Extended-release formulations of antiepileptic drugs: rationale and comparative value. Epilepsy Curr. 2009;9(6):153-157.

12. Bialer M. Extended-release formulations for the treatment of epilepsy. CNS Drugs. 2007;21(9):765-774.

13. Pellock JM, Smith MC, Cloyd JC, et al. Extended-release formulations: simplifying strategies in the management of antiepileptic drug therapy. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5(3):301-307.

14. Sarkhosh K, Birch DW, Sharma A, et al. Complications associated with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: a surgeon’s guide. Can J Surg 2013;56(5):347-352.

CASE Sudden-onset low mood

Mr. G, age 64, is obese (body mass index [BMI] 37 kg/m2) and has a history of schizoaffective disorder. He is recovering from a sleeve gastrectomy, a surgical weight-loss procedure in which a large portion of the stomach is removed. Seven weeks after his surgery, he experiences a sudden onset of “low mood” and fears that he will become suicidal; he has a history of suicide attempts. Mr. G calls his long-term outpatient clinic and is advised to go to the emergency department (ED).

For years, Mr. G had been stable in a group home setting, and had always been adherent to treatment and forthcoming about his medications with both his bariatric surgeon and psychiatrist. Within the last month, he had been seen at the clinic, had no psychiatric symptoms, and was recovering well from the sleeve gastrectomy.

HISTORY A stable regimen

Mr. G’s psychiatric symptoms initially developed when he was in his 20s, during a time in which he reported using “a lot of drugs.” He had multiple suicide attempts, and multiple inpatient and outpatient treatments. He was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder.

Mr. G has been stable on medications for the last 2 years. His outpatient psychotropic regimen is divalproex sodium extended-release (ER), 2,500 mg every night at bedtime; iloperidone, 8 mg twice a day; escitalopram, 10 mg/d; and mirtazapine, 30 mg every night at bedtime.

In the group home, Mr. G spends his days socializing, studying philosophy, and writing essays. He hopes to find a job in the craftsman industry.

Mr. G’s medical history includes obesity (BMI: 37 kg/m2). Since the surgery, he has been receiving omeprazole, 40 mg/d, a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), to decrease the amount of acid in his stomach. Three weeks after surgery, he had an unremarkable postoperative outpatient psychiatry visit. Divalproex sodium ER was maintained at the pre-surgical dose of 2,500 mg/d.

EVALUATION Depressed and frightened

In the ED, Mr. G’s vitals are normal, but his serum valproic acid (VPA) level is 33.68 µg/mL (therapeutic range: 50 to 125 µg/mL), despite being compliant with treatment. Mr. G is discharged from the ED and told to follow up with his outpatient psychiatrist the next day.

Continue to: At his outpatient psychiatry appointment...

At his outpatient psychiatry appointment, Mr. G’s vital signs are normal, but he reports increasing depression and worsened mood. On mental status examination, Mr. G’s appearance is well groomed, and no agitation nor fidgeting are observed. His behavior is cooperative but somewhat disorganized. He is perseverative on “feeling so low.” He has poor eye contact, which is unusual for him. Mr. G’s speech is loud compared with his baseline. Affect is congruent to mood, which he describes as “depressed and frightened.” He is also noted to be irritable. His thought process is abstract and tangential, which is within his baseline. Mr. G’s thought content is fearful and negativistic, despite his usual positivity and optimism. He denies hallucinations and is oriented to time, place, and person. His judgment, attention, and memory are all within normal limits.

[polldaddy:10790537]

The authors’ observations

The psychiatrist rules out malingering/nonadherence due to Mr. G’s long history of treatment compliance, as evidenced by his past symptom control and therapeutic serum VPA levels. Mr. G was compliant with his postoperative appointments and has been healing well. Therefore, the treatment team believed that Mr. G’s intense and acute decompensation had to be related to a recent change. The notable changes in Mr. G’s case included his sleeve gastrectomy, and the addition of omeprazole to his medication regimen.

The treatment team observed that Mr. G had a long history of compliance with his medications and his symptoms were consistent with a low serum VPA level, which led to the conclusion that the low serum VPA level measured while he was in the ED was likely accurate. This prompted the team to consider Mr. G’s recent surgery. It is well documented that some bariatric surgeries can cause poor absorption of certain vitamins, minerals, and medications. However, Mr. G had a sleeve gastrectomy, which preserves absorption. At this point, the team considered if the patient’s recent medication change was the source of his low VPA level.

The psychiatrist concluded that the issue must have been with the addition of omeprazole because Mr. G’s sleeve gastrectomy was noneventful, he was healing well and being closely monitored by his bariatric surgeon, and this type of surgery preserves absorption. Fortunately, Mr. G was a good historian and had informed his psychiatrist about the addition of omeprazole after his sleeve gastrectomy. The psychiatrist knew acidity was important for the absorption of some medications. Although she was unsure as to whether the problem was a lack of absorption or lack of delivery, the psychiatrist knew a medication change was necessary to raise Mr. G’s serum VPA levels.

TREATMENT A change in divalproex formulation

The psychiatrist switches Mr. G’s formulation of divalproex sodium ER, 2,500 mg/d, to valproic acid immediate-release (IR) liquid capsules. He receives a total daily dose of 2,500 mg, but the dosage is split into 3 times a day. The omeprazole is continued to maintain the postoperative healing process, and he receives his other medications as well (iloperidone, 8 mg twice a day; escitalopram, 10 mg/d; and mirtazapine, 30 mg every night at bedtime).

[polldaddy:10790540]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

The key component to creating a treatment plan for Mr. G centered on understanding drug metabolism and delivery. Acidity plays a role in dissolution of many medications, which led the team to surmise that the PPI, omeprazole, was the culprit. Through research, they understood that the divalproex sodium ER formulation needed a more acidic environment to dissolve, and therefore, an IR formulation was needed.

Different formulations, different characteristics

Medications can be produced in different formulations such as IR, delayed-release (DR), and ER formulations. Different formulations may contain the same medication at identical strengths; however, they may not be bioequivalent and should be titrated based on both the properties of the medication and the release type.1

Immediate-release formulations are developed to dissolve without delaying or prolonging absorption of the medication. These formulations typically include “superdisintegrants” containing croscarmellose sodium2 so that they disintegrate, de-aggregate, and/or dissolve when they come into contact with water or the gastrointestinal tract.3-7

Delayed-release formulations rely on the gastrointestinal pH to release the medication after a certain amount of time has elapsed due to the enteric coating surrounding the tablet. This enteric coating prevents gastric mucosa/gastric juices from inactivating an acid-labile medication.8

Extended-release formulations, such as the divalproex sodium ER that was originally prescribed to Mr. G, are designed to release the medication in a controlled manner over an extended period of time, and at a predetermined rate and location following administration.8-9 The advantage of this type of formulation is that it can be used to reduce dose frequency and improve adherence.10 Extended-release formulations are designed to minimize fluctuations in serum drug concentration between doses,11 thereby reducing the risk of adverse effects.12,13 A list of some common extended-release psychiatric medications is shown in the Table.

Continue to: The 5 oral formulations...

The 5 oral formulations of medications that contain valproic acid include:

- syrup

- capsule

- sprinkle

- enteric-coated delayed-release and extended-release

A parenteral form via IV is available for patients who are unable to swallow.

Absorption vs delivery

Any gastric bypass surgery can have postoperative complications, one of which can include absorption deficiencies of vitamins and minerals. Sleeve gastrectomy has the least amount of absorption-related nutritional deficiencies.14 Additionally, this procedure preserves the stomach’s ability to produce gastric acid. Therefore, regardless of formulation, there should be no initial postsurgical need to change psychotropic medication formulations. However, because VPA is related to B-vitamin deficiency, supplementation can be considered.

Omeprazole is a PPI that increases pH in the stomach and is often prescribed to promote healing of gastric surgery. However, in Mr. G’s case, omeprazole created a non-acidic environment in his stomach, which prevented the divalproex sodium ER formulation from being dissolved and the medication from being delivered. Mr. G’s absorption ability was preserved, which was confirmed by his rapid recovery and increased serum VPA levels once he was switched to the IR formulation. There is no literature supporting a recommended length of time a patient can receive omeprazole therapy for sleeve gastrectomy; this is at the surgeon’s discretion. Mr. G’s prescription for omeprazole was for 3 months.

Proper valproate dosing

In Mr. G’s case, it could be hypothesized that the VPA dosing was incorrect. For mood disorders, oral VPA dosing is 25 mg/kg/d. Mr. G lost 40 pounds, which would translate to a 450-mg reduction in dose. Despite maintaining his original dose, his serum VPA levels decreased by almost 50% and could not be attributed to trough measurement. In this case, Mr. G was prescribed a higher dose than needed given his weight loss.

Continue to: Divalproex sodium ER...

Divalproex sodium ER is a hydrophilic matrix tablet that requires a low pH to dissolve. Switching to an IR formulation bypassed the need for a low pH and the VPA was delivered and absorbed. Mr. G was always able to absorb the medication, but only when delivered. The Table lists other psychiatric medications that clinicians should be aware of that utilize similar hydrophilic matrix technology to slowly release medications through the gastrointestinal tract and also require low pH to release the medication from the tablet.

OUTCOME Stable once again

Two and a half weeks after his medication formulation is changed from divalproex sodium ER to IR, Mr. G shows improvement in his symptoms. His serum VPA level is 52 µg/mL, which is within therapeutic limits. He continues receiving his previous medications as well. He reports “feeling much better” and denies having any depressive symptoms nor anxiety. Mr. G is able to maintain eye contact, and has positive thought content, improved organization of thinking, and retained abstraction.

Bottom Line

All medication changes should be identified at each visit. Many extended-release psychiatric medications require lower pH to release the medication from the tablet. When evaluating nonresponse to psychotropic medications, anything that affects pH in the stomach should be considered.

Related Resources

- Monte SV, Russo KM, Mustafa E. Impact of sleeve gastrectomy on psychiatric medication use and symptoms. J Obes. 2018; 2018:8532602. doi: 10.1155/2018/8532602

- Qiu Y, Zhou D. Understanding design and development of modified release solid oral dosage forms. J Validation Technol. 2011;17(2):23-32.

- ObesityHelp, Inc. https://www.obesityhelp.com/medications-after-bariatric-surgery-wls/

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Clonidine ER • Kapvay

Divalproex sodium extended- release tablets • Depakote ER

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Methylphenidate ER tablet • Concerta

Methylphenidate ER capsule • Metadate, Jornay

Methylphenidate LA capsule • Ritalin LA

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Omeprazole • Prilosec, Zegerid

Paroxetine • Paxil

Valproic acid immediate- release capsules and solution • Depakene

Valproate sodium IV • Depacon

Venlafaxine • Effexor

CASE Sudden-onset low mood

Mr. G, age 64, is obese (body mass index [BMI] 37 kg/m2) and has a history of schizoaffective disorder. He is recovering from a sleeve gastrectomy, a surgical weight-loss procedure in which a large portion of the stomach is removed. Seven weeks after his surgery, he experiences a sudden onset of “low mood” and fears that he will become suicidal; he has a history of suicide attempts. Mr. G calls his long-term outpatient clinic and is advised to go to the emergency department (ED).

For years, Mr. G had been stable in a group home setting, and had always been adherent to treatment and forthcoming about his medications with both his bariatric surgeon and psychiatrist. Within the last month, he had been seen at the clinic, had no psychiatric symptoms, and was recovering well from the sleeve gastrectomy.

HISTORY A stable regimen

Mr. G’s psychiatric symptoms initially developed when he was in his 20s, during a time in which he reported using “a lot of drugs.” He had multiple suicide attempts, and multiple inpatient and outpatient treatments. He was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder.

Mr. G has been stable on medications for the last 2 years. His outpatient psychotropic regimen is divalproex sodium extended-release (ER), 2,500 mg every night at bedtime; iloperidone, 8 mg twice a day; escitalopram, 10 mg/d; and mirtazapine, 30 mg every night at bedtime.

In the group home, Mr. G spends his days socializing, studying philosophy, and writing essays. He hopes to find a job in the craftsman industry.

Mr. G’s medical history includes obesity (BMI: 37 kg/m2). Since the surgery, he has been receiving omeprazole, 40 mg/d, a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), to decrease the amount of acid in his stomach. Three weeks after surgery, he had an unremarkable postoperative outpatient psychiatry visit. Divalproex sodium ER was maintained at the pre-surgical dose of 2,500 mg/d.

EVALUATION Depressed and frightened