User login

Postpartum IUD insertion: Best practices

CASE 1 Multiparous female with short-interval pregnancies desires contraception

A 24-year-old woman (G4P3) presents for a routine prenatal visit in the third trimester. Her last 2 pregnancies have occurred within 3 months of her prior birth. She endorses feeling overwhelmed with having 4 children under the age of 5 years, and she specifies that she would like to avoid another pregnancy for several years. She plans to breast and bottle feed, and she notes that she tends to forget to take pills. When you look back at her prior charts, you note that she did not return for her last 2 postpartum visits. What can you offer her? What would be a safe contraceptive option for her?

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are safe, effective, and reported by patients to be satisfactory methods of contraception precisely because they are prone to less user error. The Contraceptive Choice Project demonstrated that patients are more apt to choose them when barriers such as cost and access are removed and nondirective counseling is provided.1 Given that unintended pregnancy rates hover around 48%, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends them as first-line methods for pregnancy prevention.2,3

For repeat pregnancies, the postpartum period is an especially vulnerable time—non-breastfeeding women will ovulate as soon as 25 days after birth, and by 8 weeks 30% will have ovulated.4 Approximately 40% to 57% of women report having unprotected intercourse before 6 weeks postpartum, and nearly 70% of all pregnancies in the first year postpartum are unintended.3,5 Furthermore, patients at highest risk for short-interval pregnancy, such as adolescents, are less likely to return for a postpartum visit.3

Short-interval pregnancies confer greater fetal risk, including risks of low-birth weight, preterm birth, small for gestational age and increased risk of neonatal intensive care unit admission.6 Additionally, maternal health may be compromised during a short-interval pregnancy, particularly in medically complex patients due to increased risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as postpartum bleeding or uterine rupture and disease progression.7 A 2006 meta-analysis by Conde-Agudelo and colleagues found that waiting at least 18 months between pregnancies was optimal for reducing these risks.6

Thus, the immediate postpartum period is an optimal time for addressing contraceptive needs and for preventing short-interval and unintended pregnancy. This article aims to provide evidence supporting the use of immediate postpartum IUDs, as well as their associated risks and barriers to use.

IUD types and routes for immediate postpartum insertion

There are several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that examine the immediate postpartum use of copper IUDs and levonorgestrel-releasing (LNG) IUDs.8-11 In 2010, Chen and colleagues compared placement of the immediate postpartum IUD following vaginal delivery with interval placement at 6–8 weeks postpartum. Of 51 patients enrolled in each arm, 98% received an IUD immediately postpartum, and 90% received one during their postpartum visit. There were 12 expulsions (24%) in the immediate postpartum IUD group, compared with 2 (4.4%) in the interval group. Expelled IUDs were replaced, and at 6 months both groups had similar rates of IUD use.8

Whitaker and colleagues demonstrated similar findings after randomizing a small group of women who had a cesarean delivery (CD) to interval or immediate placement. There were significantly more expulsions in the post-placental group (20%) than the interval group (0%), but there were more users of the IUD in the post-placental group than in the interval group at 12 months.9

Two RCTs, by Lester and colleagues and Levi et al, demonstrated successful placement of the copper IUD or LNG-IUD following CD, with few expulsions (0% and 8%, respectively). Patients who were randomized to immediate postpartum IUD placement were more likely to receive an IUD than those who were randomized to interval insertion, mostly due to lack of postpartum follow up. Both studies followed patients out to 6 months, and rates of IUD continuation and satisfaction were higher at this time in the immediate postpartum IUD groups.10,11

Continue to: Risks, contraindications, and breastfeeding impact...

Risks, contraindications, and breastfeeding impact

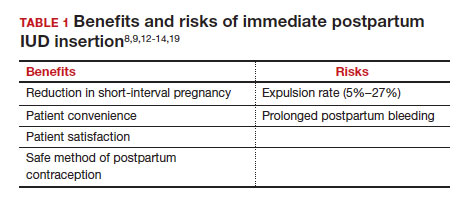

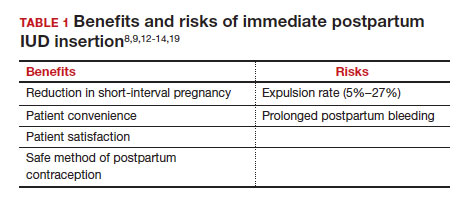

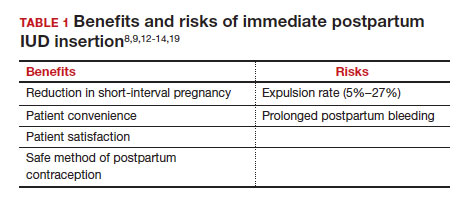

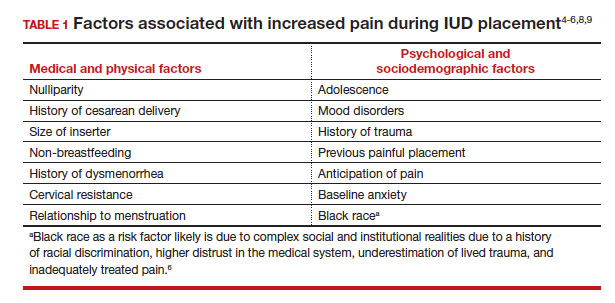

What are the risks of immediate postpartum IUD placement? The highest risk of IUD placement in the immediate postpartum period appears to be expulsion (TABLE 1). In a meta-analysis conducted in 2022, which looked at 11 studies of immediate IUD insertion, the rates of expulsion were between 5% and 27%.3,8,12,13 Results of a study by Cohen and colleagues demonstrated that most expulsions occurred within the first 12 weeks following delivery; of those expulsions that occurred, only 11% went unrecognized.13 Immediate postpartum IUD insertion does not increase the IUD-associated risks of perforation, infection, or immediate postpartum bleeding (although prolonged bleeding may be more common).12

Are there contraindications to placing an IUD immediately postpartum? The main contraindication to immediate postpartum IUD use is peripartum infection, including Triple I, endomyometritis, and puerperal sepsis. Other contraindications include retained placenta requiring manual or surgical removal, uterine anomalies, and other medical contraindications to IUD use as recommended by the US Medical Eligibility Criteria.14

Does immediate IUD placement affect breastfeeding? There is theoretical risk of decreased milk supply or difficulty breastfeeding with initiation of progestin-only methods of contraception in the immediate postpartum period, as the rapid fall in progesterone levels initiates lactogenesis. However, progestin-only methods appear to have limited effect on initiation and continuation of breastfeeding in the immediate postpartum period.15

There were 2 secondary analyses of a pair of RCTs comparing immediate and delayed postpartum IUD use. Results from Levi and colleagues demonstrated no difference between immediate and interval IUD placement groups in the proportion of women who were breastfeeding at 6, 12, and 24 weeks.16 Chen and colleagues’ study was smaller; researchers found that women with interval IUD placement were more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding and continuing to breastfeed at 6 months compared with the immediate postpartum group.17

To better characterize the impact of progestin implants, in a recent meta-analysis, authors examined the use of subcutaneous levonorgestrel rods and found no difference in breastfeeding initiation and continuation rates between women who had them placed immediately versus 6 ̶ 8 weeks postpartum.12

Benefits of immediate postpartum IUD placement

One benefit of immediate postpartum IUD insertion is a reduction in short-interval pregnancies. In a study by Cohen and colleagues13 of young women aged 13 to 22 years choosing immediate postpartum IUDs (82) or implants (162), the authors found that 61% of women retained their IUDs at 12 months postpartum. Because few requested IUD removal over that time frame, the discontinuation rate at 1 year was primarily due to expulsions. Pregnancy rates at 1 year were 7.6% in the IUD group and 1.5% in the implant group. However, the 7.6% rate in the IUD group was lower than in previously studied adolescent control groups: 18.6% of control adolescents (38 of 204) using a contraceptive form other than a postpartum etonogestrel implant had repeat pregnancy at 1 year.13,18

Not only are patients who receive immediate postpartum IUDs more likely to receive them and continue their use, but they are also satisfied with the experience of receiving the IUD and with the method of contraception. A small mixed methods study of 66 patients demonstrated that women were interested in obtaining immediate postpartum contraception to avoid some of the logistical and financial challenges of returning for a postpartum visit. They also felt that the IUD placement was less painful than expected, and they didn’t feel that the insertion process imposed on their birth experience. Many described relief to know that they had a safe and effective contraceptive method upon leaving the hospital.19 Other studies have shown that even among women who expel an IUD following immediate postpartum placement, many choose to replace it in order to continue it as a contraceptive method.8,9,13

Continue to: Instructions for placement...

Instructions for placement

1. Counsel appropriately. Thoroughly counsel patients regarding their options for postpartum contraception, with emphasis on the benefits, risks, and contraindications. Current recommendations to reduce the risk of expulsion are to place the IUD in the delivery room or operating room within 10 minutes of placental delivery.

2. Post ̶ vaginal delivery. Following vaginal delivery, remove the IUD from the inserter, cut the strings to 10 cm and, using either fingers to grasp the wings of the IUD or ring forceps, advance the IUD to the fundus. Ultrasound guidance may be used, but it does not appear to be helpful in preventing expulsion.20

3. Post ̶ cesarean delivery. Once the placenta is delivered, place the IUD using the inserter or a ring forceps at the fundus and guide the strings into the cervix, then close the hysterotomy.

ACOG does recommend formal trainingbefore placing postpartum IUDs. One resource they provide is a free online webinar (https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/webinars/long-acting-reversible-contra ception-overview-and-hands-on-practice-for-residents).3

CASE 1 Resolved

The patient was counseled in the office about her options, and she was most interested in immediate postpartum LNG-IUD placement. She went on to deliver a healthy baby vaginally at 39 weeks. Within 10 minutes of placental delivery, she received an LNG-IUD. She returned to the office 3 months later for STI screening; her examination revealed correct placement and no evidence of expulsion. She expressed that she was happy with her IUD and thankful that she was able to receive it immediately after the birth of her baby.

CASE 2 Nulliparous woman desires IUD for postpartum contraception

A 33-year-old nulliparous woman presents in the third trimester for a routine prenatal visit. She had used the LNG-IUD prior to getting pregnant and reports that she was very happy with it. She knows she wants to wait at least 2 years before trying to get pregnant again, and she would like to resume contraception as soon as it is reasonably safe to do so. She has read that it is possible to get an IUD immediately postpartum and asks about it as a possible option.

What barriers will she face in obtaining an immediate postpartum IUD?

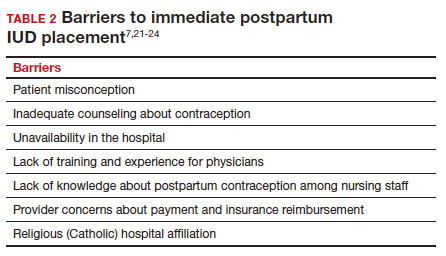

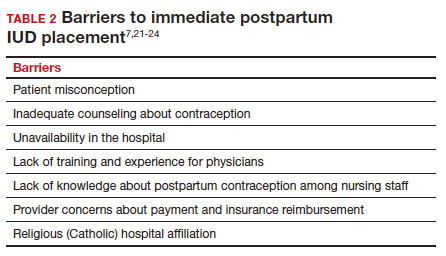

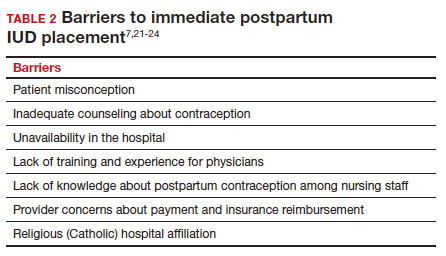

There are many barriers for patients who may be good candidates for immediate postpartum contraception (TABLE 2). Many patients are unaware that it is a safe option, and they often have concerns about such risks as infection, perforation, and effects on breastfeeding. Additionally, providers may not prioritize adequate counseling about postpartum contraception when they face time constraints and a need to counsel about other pregnancy-related topics during the prenatal visit schedule.7,21

System, hospital, and clinician barriers to immediate postpartum IUD use

Hospital implementation of a successful postpartum IUD program requires pharmacy, intrapartum and postpartum nursing staff, physicians, administration, and billing to be aligned. Hospital administration and pharmacists must stock IUDs in the pharmacy. Hospital nursing staff attitudes toward and knowledge of postpartum contraception can have profound influence on how they discuss safe and effective methods of postpartum contraception with patients who may not have received counseling during prenatal care.22 In a survey of 108 ACOG fellows, nearly 75% of ObGyn physicians did not offer immediate postpartum IUDs; lack of provider training, lack of IUD availability, and concern about cost and payment were found to be common reasons why.21 Additionally, Catholic-affiliated and rural institutions are less likely to offer it, whereas more urban, teaching hospitals are more likely to have programs in place.23 Prior to 2012, immediate postpartum IUD insertions and device costs were part of the global Medicaid obstetric fee in most states, and both hospital systems and individual providers were concerned about loss of revenue.23

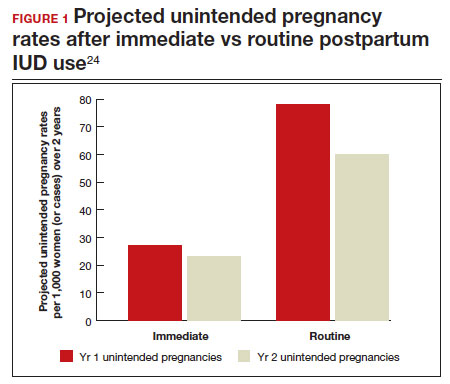

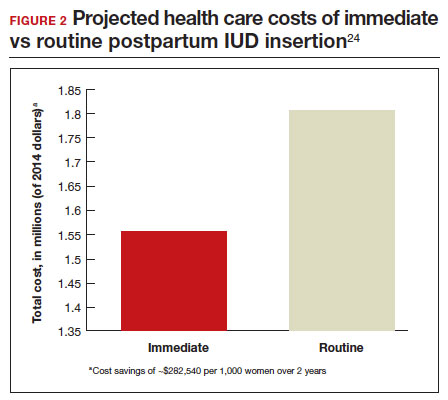

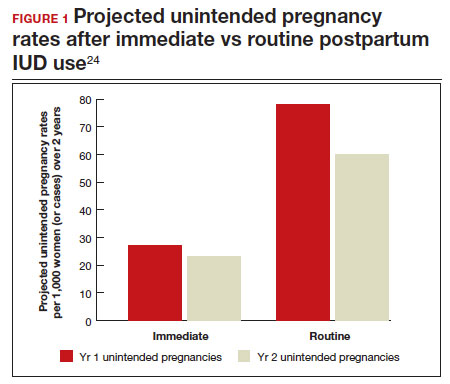

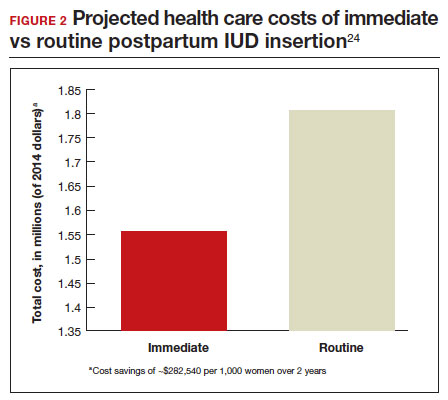

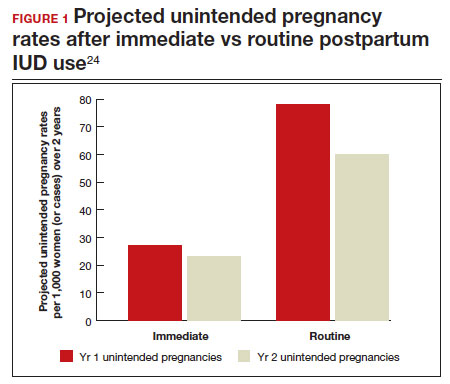

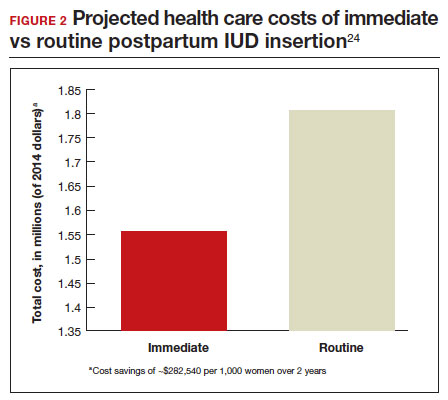

In 2015, Washington and colleagues published a decision analysis that examined the cost-effectiveness and cost savings associated with immediate postpartum IUD use. Accounting for expulsion rates, they found that immediate postpartum IUD placement can save $282,540 per 1,000 women over 2 years; additionally, immediate postpartum IUD use can prevent 88 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 women over 2 years.24 Not only do immediate postpartum IUDs have great potential to prevent individual patients from undesired short-interval pregnancies (FIGURE 1), but they can also save the system substantial health care dollars (FIGURE 2).

Overcoming barriers

Immediate postpartum IUD implementation is attainable with practice, policy, and institutional changes. Education and training programs geared toward providers and nursing staff can improve understanding of the benefits and risks of immediate postpartum IUD placement. Additionally, clinicians must provide comprehensive, nondirective counseling during the antepartum period, informing patients of all safe and effective options. Expulsion risks should be disclosed, as well as the benefit of not needing to return for a separate postpartum contraception appointment.

Since 2012, many state Medicaid agencies have decoupled reimbursement for inpatient postpartum IUD insertion from the delivery fee. By 2018, more than half of states adopted this practice. Commercial insurers have followed suit in some cases, and as such, both Medicaid and commercially insured patients have had increased access to immediate postpartum IUDs.23 This has translated into increased uptake of immediate postpartum IUDs among both Medicaid and commercially insured patients. Koch et al conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing IUD use in patients 1 year before and 1 year after the policy changes, and they found a 10-fold increase in use of immediate postpartum IUDs.25

While education, counseling, access, and changes in reimbursement may increase access in many hospital systems, some barriers, such as religious affiliation of the hospital system, may be impossible to overcome. A viable alternative to immediate postpartum IUD placement may be early postpartum IUD placement, which could allow patients to coordinate this procedure with 1- or 2-week return routine postpartum visits for CD recovery, mental health screenings, and/or well-baby visits. More data are necessary before recommending this universally, but Averbach and colleagues published a promising meta-analysis that demonstrated no complete expulsions in studies in which IUDs were placed between 2 and 4 weeks postpartum, and only a pooled partial expulsion rate (of immediate postpartum, early inpatient, early outpatient, and interval placement) of 3.7%.4

CASE 2 Resolved

Although the patient was interested in receiving a postpartum LNG-IUD immediately after her vaginal birth, she had to wait until her 6-week postpartum visit. The hospital did not stock IUDs for immediate postpartum IUD use, and her provider, having not been trained on immediate postpartum insertion, did not feel comfortable trying to place it in the immediate postpartum time frame. ●

- Immediate postpartum IUD insertion is a safe and effective method for postpartum contraception for many postpartum women.

- Immediate postpartum IUD insertion can result in increased uptake of postpartum contraception, a reduction in short interval pregnancies, and the opportunity for patients to plan their ideal family size.

- Patients should be thoroughly counseled about the safety of IUD placement and risks of expulsion associated with immediate postpartum placement.

- Successful programs for immediate postpartum IUD insertion incorporate training for providers on proper insertion techniques, education for nursing staff about safety and counseling, on-site IUD supply, and reimbursement that is decoupled from the payment for delivery.

- Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of longacting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:19982007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855.

- Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, et al. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990-2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1152-e1161. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30315-6.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 670: Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e32-e37. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001587.

- Averbach SH, Ermias Y, Jeng G, et al. Expulsion of intrauterine devices after postpartum placement by timing of placement, delivery type, and intrauterine device type: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:177188. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.045.

- Connolly A, Thorp J, Pahel L. Effects of pregnancy and childbirth on postpartum sexual function: a longitudinal prospective study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:263-267. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1293-6.

- Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermúdez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:1809-1823. doi: 10.1001 /jama.295.15.1809.

- Vricella LK, Gawron LM, Louis JM. Society for MaternalFetal Medicine (SMFM) Consult Series #48: Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception for women at high risk for medical complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:B2-B12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.011.

- Chen BA, Reeves MF, Hayes JL, et al. Postplacental or delayed insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device after vaginal delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1079-1087. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f73fac.

- Whitaker AK, Endres LK, Mistretta SQ, et al. Postplacental insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device after cesarean delivery vs. delayed insertion: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2014;89:534-539. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.007.

- Lester F, Kakaire O, Byamugisha J, et al. Intracesarean insertion of the Copper T380A versus 6 weeks postcesarean: a randomized clinical trial. Contraception. 2015;91:198-203. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.12.002.

- Levi EE, Stuart GS, Zerden ML, et al. Intrauterine device placement during cesarean delivery and continued use 6 months postpartum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:5-11. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000882.

- Sothornwit J, Kaewrudee S, Lumbiganon P, et al. Immediate versus delayed postpartum insertion of contraceptive implant and IUD for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;10:CD011913. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011913.pub3.

- Cohen R, Sheeder J, Arango N, et al. Twelve-month contraceptive continuation and repeat pregnancy among young mothers choosing postdelivery contraceptive implants or postplacental intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2016;93:178-183. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.10.001.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1-86.

- Kapp N, Curtis K, Nanda K. Progestogen-only contraceptive use among breastfeeding women: a systematic review. Contraception. 2010;82:17-37. doi: 10.1016 /j.contraception.2010.02.002.

- Levi EE, Findley MK, Avila K, et al. Placement of levonorgestrel intrauterine device at the time of cesarean delivery and the effect on breastfeeding duration. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13:674679. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2018.0060.

- Chen BA, Reeves MF, Creinin MD, et al. Postplacental or delayed levonorgestrel intrauterine device insertion and breast-feeding duration. Contraception. 2011;84:499-504. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.022.

- Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:481.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.015.

- Carr SL, Singh RH, Sussman AL, et al. Women’s experiences with immediate postpartum intrauterine device insertion: a mixed-methods study. Contraception. 2018;97:219-226. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.10.008.

- Martinez OP, Wilder L, Seal P. Ultrasound-guided compared with non-ultrasound-Guided placement of immediate postpartum intrauterine contraceptive devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:91-93. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004828.

- Holden EC, Lai E, Morelli SS, et al. Ongoing barriers to immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception: a physician survey. Contracept Reprod Med. 2018;3:23. doi: 10.1186/s40834-018-0078-5.

- Benfield N, Hawkins F, Ray L, et al. Exposure to routine availability of immediate postpartum LARC: effect on attitudes and practices of labor and delivery and postpartum nurses. Contraception. 2018;97:411-414. doi: 10.1016 /j.contraception.2018.01.017.

- Steenland MW, Vatsa R, Pace LE, et al. Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraceptive use following statespecific changes in hospital Medicaid reimbursement. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2237918. doi: 10.1001 /jamanetworkopen.2022.37918.

- Washington CI, Jamshidi R, Thung SF, et al. Timing of postpartum intrauterine device placement: a costeffectiveness analysis. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:131-137. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.09.032

CASE 1 Multiparous female with short-interval pregnancies desires contraception

A 24-year-old woman (G4P3) presents for a routine prenatal visit in the third trimester. Her last 2 pregnancies have occurred within 3 months of her prior birth. She endorses feeling overwhelmed with having 4 children under the age of 5 years, and she specifies that she would like to avoid another pregnancy for several years. She plans to breast and bottle feed, and she notes that she tends to forget to take pills. When you look back at her prior charts, you note that she did not return for her last 2 postpartum visits. What can you offer her? What would be a safe contraceptive option for her?

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are safe, effective, and reported by patients to be satisfactory methods of contraception precisely because they are prone to less user error. The Contraceptive Choice Project demonstrated that patients are more apt to choose them when barriers such as cost and access are removed and nondirective counseling is provided.1 Given that unintended pregnancy rates hover around 48%, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends them as first-line methods for pregnancy prevention.2,3

For repeat pregnancies, the postpartum period is an especially vulnerable time—non-breastfeeding women will ovulate as soon as 25 days after birth, and by 8 weeks 30% will have ovulated.4 Approximately 40% to 57% of women report having unprotected intercourse before 6 weeks postpartum, and nearly 70% of all pregnancies in the first year postpartum are unintended.3,5 Furthermore, patients at highest risk for short-interval pregnancy, such as adolescents, are less likely to return for a postpartum visit.3

Short-interval pregnancies confer greater fetal risk, including risks of low-birth weight, preterm birth, small for gestational age and increased risk of neonatal intensive care unit admission.6 Additionally, maternal health may be compromised during a short-interval pregnancy, particularly in medically complex patients due to increased risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as postpartum bleeding or uterine rupture and disease progression.7 A 2006 meta-analysis by Conde-Agudelo and colleagues found that waiting at least 18 months between pregnancies was optimal for reducing these risks.6

Thus, the immediate postpartum period is an optimal time for addressing contraceptive needs and for preventing short-interval and unintended pregnancy. This article aims to provide evidence supporting the use of immediate postpartum IUDs, as well as their associated risks and barriers to use.

IUD types and routes for immediate postpartum insertion

There are several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that examine the immediate postpartum use of copper IUDs and levonorgestrel-releasing (LNG) IUDs.8-11 In 2010, Chen and colleagues compared placement of the immediate postpartum IUD following vaginal delivery with interval placement at 6–8 weeks postpartum. Of 51 patients enrolled in each arm, 98% received an IUD immediately postpartum, and 90% received one during their postpartum visit. There were 12 expulsions (24%) in the immediate postpartum IUD group, compared with 2 (4.4%) in the interval group. Expelled IUDs were replaced, and at 6 months both groups had similar rates of IUD use.8

Whitaker and colleagues demonstrated similar findings after randomizing a small group of women who had a cesarean delivery (CD) to interval or immediate placement. There were significantly more expulsions in the post-placental group (20%) than the interval group (0%), but there were more users of the IUD in the post-placental group than in the interval group at 12 months.9

Two RCTs, by Lester and colleagues and Levi et al, demonstrated successful placement of the copper IUD or LNG-IUD following CD, with few expulsions (0% and 8%, respectively). Patients who were randomized to immediate postpartum IUD placement were more likely to receive an IUD than those who were randomized to interval insertion, mostly due to lack of postpartum follow up. Both studies followed patients out to 6 months, and rates of IUD continuation and satisfaction were higher at this time in the immediate postpartum IUD groups.10,11

Continue to: Risks, contraindications, and breastfeeding impact...

Risks, contraindications, and breastfeeding impact

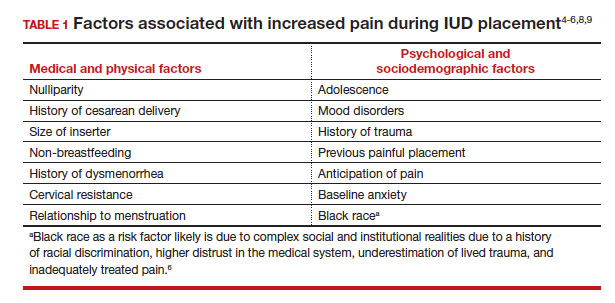

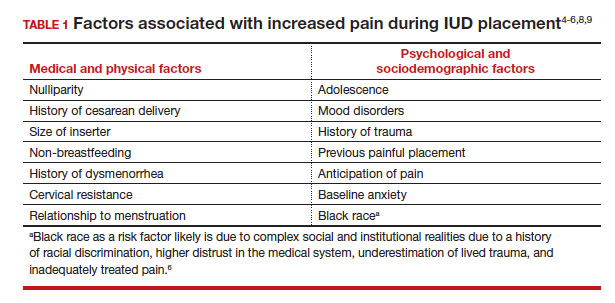

What are the risks of immediate postpartum IUD placement? The highest risk of IUD placement in the immediate postpartum period appears to be expulsion (TABLE 1). In a meta-analysis conducted in 2022, which looked at 11 studies of immediate IUD insertion, the rates of expulsion were between 5% and 27%.3,8,12,13 Results of a study by Cohen and colleagues demonstrated that most expulsions occurred within the first 12 weeks following delivery; of those expulsions that occurred, only 11% went unrecognized.13 Immediate postpartum IUD insertion does not increase the IUD-associated risks of perforation, infection, or immediate postpartum bleeding (although prolonged bleeding may be more common).12

Are there contraindications to placing an IUD immediately postpartum? The main contraindication to immediate postpartum IUD use is peripartum infection, including Triple I, endomyometritis, and puerperal sepsis. Other contraindications include retained placenta requiring manual or surgical removal, uterine anomalies, and other medical contraindications to IUD use as recommended by the US Medical Eligibility Criteria.14

Does immediate IUD placement affect breastfeeding? There is theoretical risk of decreased milk supply or difficulty breastfeeding with initiation of progestin-only methods of contraception in the immediate postpartum period, as the rapid fall in progesterone levels initiates lactogenesis. However, progestin-only methods appear to have limited effect on initiation and continuation of breastfeeding in the immediate postpartum period.15

There were 2 secondary analyses of a pair of RCTs comparing immediate and delayed postpartum IUD use. Results from Levi and colleagues demonstrated no difference between immediate and interval IUD placement groups in the proportion of women who were breastfeeding at 6, 12, and 24 weeks.16 Chen and colleagues’ study was smaller; researchers found that women with interval IUD placement were more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding and continuing to breastfeed at 6 months compared with the immediate postpartum group.17

To better characterize the impact of progestin implants, in a recent meta-analysis, authors examined the use of subcutaneous levonorgestrel rods and found no difference in breastfeeding initiation and continuation rates between women who had them placed immediately versus 6 ̶ 8 weeks postpartum.12

Benefits of immediate postpartum IUD placement

One benefit of immediate postpartum IUD insertion is a reduction in short-interval pregnancies. In a study by Cohen and colleagues13 of young women aged 13 to 22 years choosing immediate postpartum IUDs (82) or implants (162), the authors found that 61% of women retained their IUDs at 12 months postpartum. Because few requested IUD removal over that time frame, the discontinuation rate at 1 year was primarily due to expulsions. Pregnancy rates at 1 year were 7.6% in the IUD group and 1.5% in the implant group. However, the 7.6% rate in the IUD group was lower than in previously studied adolescent control groups: 18.6% of control adolescents (38 of 204) using a contraceptive form other than a postpartum etonogestrel implant had repeat pregnancy at 1 year.13,18

Not only are patients who receive immediate postpartum IUDs more likely to receive them and continue their use, but they are also satisfied with the experience of receiving the IUD and with the method of contraception. A small mixed methods study of 66 patients demonstrated that women were interested in obtaining immediate postpartum contraception to avoid some of the logistical and financial challenges of returning for a postpartum visit. They also felt that the IUD placement was less painful than expected, and they didn’t feel that the insertion process imposed on their birth experience. Many described relief to know that they had a safe and effective contraceptive method upon leaving the hospital.19 Other studies have shown that even among women who expel an IUD following immediate postpartum placement, many choose to replace it in order to continue it as a contraceptive method.8,9,13

Continue to: Instructions for placement...

Instructions for placement

1. Counsel appropriately. Thoroughly counsel patients regarding their options for postpartum contraception, with emphasis on the benefits, risks, and contraindications. Current recommendations to reduce the risk of expulsion are to place the IUD in the delivery room or operating room within 10 minutes of placental delivery.

2. Post ̶ vaginal delivery. Following vaginal delivery, remove the IUD from the inserter, cut the strings to 10 cm and, using either fingers to grasp the wings of the IUD or ring forceps, advance the IUD to the fundus. Ultrasound guidance may be used, but it does not appear to be helpful in preventing expulsion.20

3. Post ̶ cesarean delivery. Once the placenta is delivered, place the IUD using the inserter or a ring forceps at the fundus and guide the strings into the cervix, then close the hysterotomy.

ACOG does recommend formal trainingbefore placing postpartum IUDs. One resource they provide is a free online webinar (https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/webinars/long-acting-reversible-contra ception-overview-and-hands-on-practice-for-residents).3

CASE 1 Resolved

The patient was counseled in the office about her options, and she was most interested in immediate postpartum LNG-IUD placement. She went on to deliver a healthy baby vaginally at 39 weeks. Within 10 minutes of placental delivery, she received an LNG-IUD. She returned to the office 3 months later for STI screening; her examination revealed correct placement and no evidence of expulsion. She expressed that she was happy with her IUD and thankful that she was able to receive it immediately after the birth of her baby.

CASE 2 Nulliparous woman desires IUD for postpartum contraception

A 33-year-old nulliparous woman presents in the third trimester for a routine prenatal visit. She had used the LNG-IUD prior to getting pregnant and reports that she was very happy with it. She knows she wants to wait at least 2 years before trying to get pregnant again, and she would like to resume contraception as soon as it is reasonably safe to do so. She has read that it is possible to get an IUD immediately postpartum and asks about it as a possible option.

What barriers will she face in obtaining an immediate postpartum IUD?

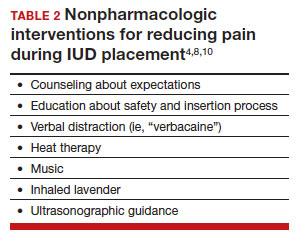

There are many barriers for patients who may be good candidates for immediate postpartum contraception (TABLE 2). Many patients are unaware that it is a safe option, and they often have concerns about such risks as infection, perforation, and effects on breastfeeding. Additionally, providers may not prioritize adequate counseling about postpartum contraception when they face time constraints and a need to counsel about other pregnancy-related topics during the prenatal visit schedule.7,21

System, hospital, and clinician barriers to immediate postpartum IUD use

Hospital implementation of a successful postpartum IUD program requires pharmacy, intrapartum and postpartum nursing staff, physicians, administration, and billing to be aligned. Hospital administration and pharmacists must stock IUDs in the pharmacy. Hospital nursing staff attitudes toward and knowledge of postpartum contraception can have profound influence on how they discuss safe and effective methods of postpartum contraception with patients who may not have received counseling during prenatal care.22 In a survey of 108 ACOG fellows, nearly 75% of ObGyn physicians did not offer immediate postpartum IUDs; lack of provider training, lack of IUD availability, and concern about cost and payment were found to be common reasons why.21 Additionally, Catholic-affiliated and rural institutions are less likely to offer it, whereas more urban, teaching hospitals are more likely to have programs in place.23 Prior to 2012, immediate postpartum IUD insertions and device costs were part of the global Medicaid obstetric fee in most states, and both hospital systems and individual providers were concerned about loss of revenue.23

In 2015, Washington and colleagues published a decision analysis that examined the cost-effectiveness and cost savings associated with immediate postpartum IUD use. Accounting for expulsion rates, they found that immediate postpartum IUD placement can save $282,540 per 1,000 women over 2 years; additionally, immediate postpartum IUD use can prevent 88 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 women over 2 years.24 Not only do immediate postpartum IUDs have great potential to prevent individual patients from undesired short-interval pregnancies (FIGURE 1), but they can also save the system substantial health care dollars (FIGURE 2).

Overcoming barriers

Immediate postpartum IUD implementation is attainable with practice, policy, and institutional changes. Education and training programs geared toward providers and nursing staff can improve understanding of the benefits and risks of immediate postpartum IUD placement. Additionally, clinicians must provide comprehensive, nondirective counseling during the antepartum period, informing patients of all safe and effective options. Expulsion risks should be disclosed, as well as the benefit of not needing to return for a separate postpartum contraception appointment.

Since 2012, many state Medicaid agencies have decoupled reimbursement for inpatient postpartum IUD insertion from the delivery fee. By 2018, more than half of states adopted this practice. Commercial insurers have followed suit in some cases, and as such, both Medicaid and commercially insured patients have had increased access to immediate postpartum IUDs.23 This has translated into increased uptake of immediate postpartum IUDs among both Medicaid and commercially insured patients. Koch et al conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing IUD use in patients 1 year before and 1 year after the policy changes, and they found a 10-fold increase in use of immediate postpartum IUDs.25

While education, counseling, access, and changes in reimbursement may increase access in many hospital systems, some barriers, such as religious affiliation of the hospital system, may be impossible to overcome. A viable alternative to immediate postpartum IUD placement may be early postpartum IUD placement, which could allow patients to coordinate this procedure with 1- or 2-week return routine postpartum visits for CD recovery, mental health screenings, and/or well-baby visits. More data are necessary before recommending this universally, but Averbach and colleagues published a promising meta-analysis that demonstrated no complete expulsions in studies in which IUDs were placed between 2 and 4 weeks postpartum, and only a pooled partial expulsion rate (of immediate postpartum, early inpatient, early outpatient, and interval placement) of 3.7%.4

CASE 2 Resolved

Although the patient was interested in receiving a postpartum LNG-IUD immediately after her vaginal birth, she had to wait until her 6-week postpartum visit. The hospital did not stock IUDs for immediate postpartum IUD use, and her provider, having not been trained on immediate postpartum insertion, did not feel comfortable trying to place it in the immediate postpartum time frame. ●

- Immediate postpartum IUD insertion is a safe and effective method for postpartum contraception for many postpartum women.

- Immediate postpartum IUD insertion can result in increased uptake of postpartum contraception, a reduction in short interval pregnancies, and the opportunity for patients to plan their ideal family size.

- Patients should be thoroughly counseled about the safety of IUD placement and risks of expulsion associated with immediate postpartum placement.

- Successful programs for immediate postpartum IUD insertion incorporate training for providers on proper insertion techniques, education for nursing staff about safety and counseling, on-site IUD supply, and reimbursement that is decoupled from the payment for delivery.

CASE 1 Multiparous female with short-interval pregnancies desires contraception

A 24-year-old woman (G4P3) presents for a routine prenatal visit in the third trimester. Her last 2 pregnancies have occurred within 3 months of her prior birth. She endorses feeling overwhelmed with having 4 children under the age of 5 years, and she specifies that she would like to avoid another pregnancy for several years. She plans to breast and bottle feed, and she notes that she tends to forget to take pills. When you look back at her prior charts, you note that she did not return for her last 2 postpartum visits. What can you offer her? What would be a safe contraceptive option for her?

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are safe, effective, and reported by patients to be satisfactory methods of contraception precisely because they are prone to less user error. The Contraceptive Choice Project demonstrated that patients are more apt to choose them when barriers such as cost and access are removed and nondirective counseling is provided.1 Given that unintended pregnancy rates hover around 48%, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends them as first-line methods for pregnancy prevention.2,3

For repeat pregnancies, the postpartum period is an especially vulnerable time—non-breastfeeding women will ovulate as soon as 25 days after birth, and by 8 weeks 30% will have ovulated.4 Approximately 40% to 57% of women report having unprotected intercourse before 6 weeks postpartum, and nearly 70% of all pregnancies in the first year postpartum are unintended.3,5 Furthermore, patients at highest risk for short-interval pregnancy, such as adolescents, are less likely to return for a postpartum visit.3

Short-interval pregnancies confer greater fetal risk, including risks of low-birth weight, preterm birth, small for gestational age and increased risk of neonatal intensive care unit admission.6 Additionally, maternal health may be compromised during a short-interval pregnancy, particularly in medically complex patients due to increased risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as postpartum bleeding or uterine rupture and disease progression.7 A 2006 meta-analysis by Conde-Agudelo and colleagues found that waiting at least 18 months between pregnancies was optimal for reducing these risks.6

Thus, the immediate postpartum period is an optimal time for addressing contraceptive needs and for preventing short-interval and unintended pregnancy. This article aims to provide evidence supporting the use of immediate postpartum IUDs, as well as their associated risks and barriers to use.

IUD types and routes for immediate postpartum insertion

There are several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that examine the immediate postpartum use of copper IUDs and levonorgestrel-releasing (LNG) IUDs.8-11 In 2010, Chen and colleagues compared placement of the immediate postpartum IUD following vaginal delivery with interval placement at 6–8 weeks postpartum. Of 51 patients enrolled in each arm, 98% received an IUD immediately postpartum, and 90% received one during their postpartum visit. There were 12 expulsions (24%) in the immediate postpartum IUD group, compared with 2 (4.4%) in the interval group. Expelled IUDs were replaced, and at 6 months both groups had similar rates of IUD use.8

Whitaker and colleagues demonstrated similar findings after randomizing a small group of women who had a cesarean delivery (CD) to interval or immediate placement. There were significantly more expulsions in the post-placental group (20%) than the interval group (0%), but there were more users of the IUD in the post-placental group than in the interval group at 12 months.9

Two RCTs, by Lester and colleagues and Levi et al, demonstrated successful placement of the copper IUD or LNG-IUD following CD, with few expulsions (0% and 8%, respectively). Patients who were randomized to immediate postpartum IUD placement were more likely to receive an IUD than those who were randomized to interval insertion, mostly due to lack of postpartum follow up. Both studies followed patients out to 6 months, and rates of IUD continuation and satisfaction were higher at this time in the immediate postpartum IUD groups.10,11

Continue to: Risks, contraindications, and breastfeeding impact...

Risks, contraindications, and breastfeeding impact

What are the risks of immediate postpartum IUD placement? The highest risk of IUD placement in the immediate postpartum period appears to be expulsion (TABLE 1). In a meta-analysis conducted in 2022, which looked at 11 studies of immediate IUD insertion, the rates of expulsion were between 5% and 27%.3,8,12,13 Results of a study by Cohen and colleagues demonstrated that most expulsions occurred within the first 12 weeks following delivery; of those expulsions that occurred, only 11% went unrecognized.13 Immediate postpartum IUD insertion does not increase the IUD-associated risks of perforation, infection, or immediate postpartum bleeding (although prolonged bleeding may be more common).12

Are there contraindications to placing an IUD immediately postpartum? The main contraindication to immediate postpartum IUD use is peripartum infection, including Triple I, endomyometritis, and puerperal sepsis. Other contraindications include retained placenta requiring manual or surgical removal, uterine anomalies, and other medical contraindications to IUD use as recommended by the US Medical Eligibility Criteria.14

Does immediate IUD placement affect breastfeeding? There is theoretical risk of decreased milk supply or difficulty breastfeeding with initiation of progestin-only methods of contraception in the immediate postpartum period, as the rapid fall in progesterone levels initiates lactogenesis. However, progestin-only methods appear to have limited effect on initiation and continuation of breastfeeding in the immediate postpartum period.15

There were 2 secondary analyses of a pair of RCTs comparing immediate and delayed postpartum IUD use. Results from Levi and colleagues demonstrated no difference between immediate and interval IUD placement groups in the proportion of women who were breastfeeding at 6, 12, and 24 weeks.16 Chen and colleagues’ study was smaller; researchers found that women with interval IUD placement were more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding and continuing to breastfeed at 6 months compared with the immediate postpartum group.17

To better characterize the impact of progestin implants, in a recent meta-analysis, authors examined the use of subcutaneous levonorgestrel rods and found no difference in breastfeeding initiation and continuation rates between women who had them placed immediately versus 6 ̶ 8 weeks postpartum.12

Benefits of immediate postpartum IUD placement

One benefit of immediate postpartum IUD insertion is a reduction in short-interval pregnancies. In a study by Cohen and colleagues13 of young women aged 13 to 22 years choosing immediate postpartum IUDs (82) or implants (162), the authors found that 61% of women retained their IUDs at 12 months postpartum. Because few requested IUD removal over that time frame, the discontinuation rate at 1 year was primarily due to expulsions. Pregnancy rates at 1 year were 7.6% in the IUD group and 1.5% in the implant group. However, the 7.6% rate in the IUD group was lower than in previously studied adolescent control groups: 18.6% of control adolescents (38 of 204) using a contraceptive form other than a postpartum etonogestrel implant had repeat pregnancy at 1 year.13,18

Not only are patients who receive immediate postpartum IUDs more likely to receive them and continue their use, but they are also satisfied with the experience of receiving the IUD and with the method of contraception. A small mixed methods study of 66 patients demonstrated that women were interested in obtaining immediate postpartum contraception to avoid some of the logistical and financial challenges of returning for a postpartum visit. They also felt that the IUD placement was less painful than expected, and they didn’t feel that the insertion process imposed on their birth experience. Many described relief to know that they had a safe and effective contraceptive method upon leaving the hospital.19 Other studies have shown that even among women who expel an IUD following immediate postpartum placement, many choose to replace it in order to continue it as a contraceptive method.8,9,13

Continue to: Instructions for placement...

Instructions for placement

1. Counsel appropriately. Thoroughly counsel patients regarding their options for postpartum contraception, with emphasis on the benefits, risks, and contraindications. Current recommendations to reduce the risk of expulsion are to place the IUD in the delivery room or operating room within 10 minutes of placental delivery.

2. Post ̶ vaginal delivery. Following vaginal delivery, remove the IUD from the inserter, cut the strings to 10 cm and, using either fingers to grasp the wings of the IUD or ring forceps, advance the IUD to the fundus. Ultrasound guidance may be used, but it does not appear to be helpful in preventing expulsion.20

3. Post ̶ cesarean delivery. Once the placenta is delivered, place the IUD using the inserter or a ring forceps at the fundus and guide the strings into the cervix, then close the hysterotomy.

ACOG does recommend formal trainingbefore placing postpartum IUDs. One resource they provide is a free online webinar (https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/webinars/long-acting-reversible-contra ception-overview-and-hands-on-practice-for-residents).3

CASE 1 Resolved

The patient was counseled in the office about her options, and she was most interested in immediate postpartum LNG-IUD placement. She went on to deliver a healthy baby vaginally at 39 weeks. Within 10 minutes of placental delivery, she received an LNG-IUD. She returned to the office 3 months later for STI screening; her examination revealed correct placement and no evidence of expulsion. She expressed that she was happy with her IUD and thankful that she was able to receive it immediately after the birth of her baby.

CASE 2 Nulliparous woman desires IUD for postpartum contraception

A 33-year-old nulliparous woman presents in the third trimester for a routine prenatal visit. She had used the LNG-IUD prior to getting pregnant and reports that she was very happy with it. She knows she wants to wait at least 2 years before trying to get pregnant again, and she would like to resume contraception as soon as it is reasonably safe to do so. She has read that it is possible to get an IUD immediately postpartum and asks about it as a possible option.

What barriers will she face in obtaining an immediate postpartum IUD?

There are many barriers for patients who may be good candidates for immediate postpartum contraception (TABLE 2). Many patients are unaware that it is a safe option, and they often have concerns about such risks as infection, perforation, and effects on breastfeeding. Additionally, providers may not prioritize adequate counseling about postpartum contraception when they face time constraints and a need to counsel about other pregnancy-related topics during the prenatal visit schedule.7,21

System, hospital, and clinician barriers to immediate postpartum IUD use

Hospital implementation of a successful postpartum IUD program requires pharmacy, intrapartum and postpartum nursing staff, physicians, administration, and billing to be aligned. Hospital administration and pharmacists must stock IUDs in the pharmacy. Hospital nursing staff attitudes toward and knowledge of postpartum contraception can have profound influence on how they discuss safe and effective methods of postpartum contraception with patients who may not have received counseling during prenatal care.22 In a survey of 108 ACOG fellows, nearly 75% of ObGyn physicians did not offer immediate postpartum IUDs; lack of provider training, lack of IUD availability, and concern about cost and payment were found to be common reasons why.21 Additionally, Catholic-affiliated and rural institutions are less likely to offer it, whereas more urban, teaching hospitals are more likely to have programs in place.23 Prior to 2012, immediate postpartum IUD insertions and device costs were part of the global Medicaid obstetric fee in most states, and both hospital systems and individual providers were concerned about loss of revenue.23

In 2015, Washington and colleagues published a decision analysis that examined the cost-effectiveness and cost savings associated with immediate postpartum IUD use. Accounting for expulsion rates, they found that immediate postpartum IUD placement can save $282,540 per 1,000 women over 2 years; additionally, immediate postpartum IUD use can prevent 88 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 women over 2 years.24 Not only do immediate postpartum IUDs have great potential to prevent individual patients from undesired short-interval pregnancies (FIGURE 1), but they can also save the system substantial health care dollars (FIGURE 2).

Overcoming barriers

Immediate postpartum IUD implementation is attainable with practice, policy, and institutional changes. Education and training programs geared toward providers and nursing staff can improve understanding of the benefits and risks of immediate postpartum IUD placement. Additionally, clinicians must provide comprehensive, nondirective counseling during the antepartum period, informing patients of all safe and effective options. Expulsion risks should be disclosed, as well as the benefit of not needing to return for a separate postpartum contraception appointment.

Since 2012, many state Medicaid agencies have decoupled reimbursement for inpatient postpartum IUD insertion from the delivery fee. By 2018, more than half of states adopted this practice. Commercial insurers have followed suit in some cases, and as such, both Medicaid and commercially insured patients have had increased access to immediate postpartum IUDs.23 This has translated into increased uptake of immediate postpartum IUDs among both Medicaid and commercially insured patients. Koch et al conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing IUD use in patients 1 year before and 1 year after the policy changes, and they found a 10-fold increase in use of immediate postpartum IUDs.25

While education, counseling, access, and changes in reimbursement may increase access in many hospital systems, some barriers, such as religious affiliation of the hospital system, may be impossible to overcome. A viable alternative to immediate postpartum IUD placement may be early postpartum IUD placement, which could allow patients to coordinate this procedure with 1- or 2-week return routine postpartum visits for CD recovery, mental health screenings, and/or well-baby visits. More data are necessary before recommending this universally, but Averbach and colleagues published a promising meta-analysis that demonstrated no complete expulsions in studies in which IUDs were placed between 2 and 4 weeks postpartum, and only a pooled partial expulsion rate (of immediate postpartum, early inpatient, early outpatient, and interval placement) of 3.7%.4

CASE 2 Resolved

Although the patient was interested in receiving a postpartum LNG-IUD immediately after her vaginal birth, she had to wait until her 6-week postpartum visit. The hospital did not stock IUDs for immediate postpartum IUD use, and her provider, having not been trained on immediate postpartum insertion, did not feel comfortable trying to place it in the immediate postpartum time frame. ●

- Immediate postpartum IUD insertion is a safe and effective method for postpartum contraception for many postpartum women.

- Immediate postpartum IUD insertion can result in increased uptake of postpartum contraception, a reduction in short interval pregnancies, and the opportunity for patients to plan their ideal family size.

- Patients should be thoroughly counseled about the safety of IUD placement and risks of expulsion associated with immediate postpartum placement.

- Successful programs for immediate postpartum IUD insertion incorporate training for providers on proper insertion techniques, education for nursing staff about safety and counseling, on-site IUD supply, and reimbursement that is decoupled from the payment for delivery.

- Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of longacting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:19982007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855.

- Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, et al. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990-2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1152-e1161. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30315-6.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 670: Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e32-e37. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001587.

- Averbach SH, Ermias Y, Jeng G, et al. Expulsion of intrauterine devices after postpartum placement by timing of placement, delivery type, and intrauterine device type: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:177188. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.045.

- Connolly A, Thorp J, Pahel L. Effects of pregnancy and childbirth on postpartum sexual function: a longitudinal prospective study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:263-267. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1293-6.

- Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermúdez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:1809-1823. doi: 10.1001 /jama.295.15.1809.

- Vricella LK, Gawron LM, Louis JM. Society for MaternalFetal Medicine (SMFM) Consult Series #48: Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception for women at high risk for medical complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:B2-B12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.011.

- Chen BA, Reeves MF, Hayes JL, et al. Postplacental or delayed insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device after vaginal delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1079-1087. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f73fac.

- Whitaker AK, Endres LK, Mistretta SQ, et al. Postplacental insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device after cesarean delivery vs. delayed insertion: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2014;89:534-539. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.007.

- Lester F, Kakaire O, Byamugisha J, et al. Intracesarean insertion of the Copper T380A versus 6 weeks postcesarean: a randomized clinical trial. Contraception. 2015;91:198-203. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.12.002.

- Levi EE, Stuart GS, Zerden ML, et al. Intrauterine device placement during cesarean delivery and continued use 6 months postpartum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:5-11. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000882.

- Sothornwit J, Kaewrudee S, Lumbiganon P, et al. Immediate versus delayed postpartum insertion of contraceptive implant and IUD for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;10:CD011913. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011913.pub3.

- Cohen R, Sheeder J, Arango N, et al. Twelve-month contraceptive continuation and repeat pregnancy among young mothers choosing postdelivery contraceptive implants or postplacental intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2016;93:178-183. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.10.001.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1-86.

- Kapp N, Curtis K, Nanda K. Progestogen-only contraceptive use among breastfeeding women: a systematic review. Contraception. 2010;82:17-37. doi: 10.1016 /j.contraception.2010.02.002.

- Levi EE, Findley MK, Avila K, et al. Placement of levonorgestrel intrauterine device at the time of cesarean delivery and the effect on breastfeeding duration. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13:674679. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2018.0060.

- Chen BA, Reeves MF, Creinin MD, et al. Postplacental or delayed levonorgestrel intrauterine device insertion and breast-feeding duration. Contraception. 2011;84:499-504. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.022.

- Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:481.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.015.

- Carr SL, Singh RH, Sussman AL, et al. Women’s experiences with immediate postpartum intrauterine device insertion: a mixed-methods study. Contraception. 2018;97:219-226. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.10.008.

- Martinez OP, Wilder L, Seal P. Ultrasound-guided compared with non-ultrasound-Guided placement of immediate postpartum intrauterine contraceptive devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:91-93. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004828.

- Holden EC, Lai E, Morelli SS, et al. Ongoing barriers to immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception: a physician survey. Contracept Reprod Med. 2018;3:23. doi: 10.1186/s40834-018-0078-5.

- Benfield N, Hawkins F, Ray L, et al. Exposure to routine availability of immediate postpartum LARC: effect on attitudes and practices of labor and delivery and postpartum nurses. Contraception. 2018;97:411-414. doi: 10.1016 /j.contraception.2018.01.017.

- Steenland MW, Vatsa R, Pace LE, et al. Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraceptive use following statespecific changes in hospital Medicaid reimbursement. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2237918. doi: 10.1001 /jamanetworkopen.2022.37918.

- Washington CI, Jamshidi R, Thung SF, et al. Timing of postpartum intrauterine device placement: a costeffectiveness analysis. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:131-137. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.09.032

- Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of longacting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:19982007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855.

- Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, et al. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990-2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1152-e1161. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30315-6.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 670: Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e32-e37. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001587.

- Averbach SH, Ermias Y, Jeng G, et al. Expulsion of intrauterine devices after postpartum placement by timing of placement, delivery type, and intrauterine device type: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:177188. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.045.

- Connolly A, Thorp J, Pahel L. Effects of pregnancy and childbirth on postpartum sexual function: a longitudinal prospective study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:263-267. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1293-6.

- Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermúdez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:1809-1823. doi: 10.1001 /jama.295.15.1809.

- Vricella LK, Gawron LM, Louis JM. Society for MaternalFetal Medicine (SMFM) Consult Series #48: Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception for women at high risk for medical complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:B2-B12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.011.

- Chen BA, Reeves MF, Hayes JL, et al. Postplacental or delayed insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device after vaginal delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1079-1087. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f73fac.

- Whitaker AK, Endres LK, Mistretta SQ, et al. Postplacental insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device after cesarean delivery vs. delayed insertion: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2014;89:534-539. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.007.

- Lester F, Kakaire O, Byamugisha J, et al. Intracesarean insertion of the Copper T380A versus 6 weeks postcesarean: a randomized clinical trial. Contraception. 2015;91:198-203. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.12.002.

- Levi EE, Stuart GS, Zerden ML, et al. Intrauterine device placement during cesarean delivery and continued use 6 months postpartum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:5-11. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000882.

- Sothornwit J, Kaewrudee S, Lumbiganon P, et al. Immediate versus delayed postpartum insertion of contraceptive implant and IUD for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;10:CD011913. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011913.pub3.

- Cohen R, Sheeder J, Arango N, et al. Twelve-month contraceptive continuation and repeat pregnancy among young mothers choosing postdelivery contraceptive implants or postplacental intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2016;93:178-183. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.10.001.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1-86.

- Kapp N, Curtis K, Nanda K. Progestogen-only contraceptive use among breastfeeding women: a systematic review. Contraception. 2010;82:17-37. doi: 10.1016 /j.contraception.2010.02.002.

- Levi EE, Findley MK, Avila K, et al. Placement of levonorgestrel intrauterine device at the time of cesarean delivery and the effect on breastfeeding duration. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13:674679. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2018.0060.

- Chen BA, Reeves MF, Creinin MD, et al. Postplacental or delayed levonorgestrel intrauterine device insertion and breast-feeding duration. Contraception. 2011;84:499-504. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.022.

- Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:481.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.015.

- Carr SL, Singh RH, Sussman AL, et al. Women’s experiences with immediate postpartum intrauterine device insertion: a mixed-methods study. Contraception. 2018;97:219-226. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.10.008.

- Martinez OP, Wilder L, Seal P. Ultrasound-guided compared with non-ultrasound-Guided placement of immediate postpartum intrauterine contraceptive devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:91-93. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004828.

- Holden EC, Lai E, Morelli SS, et al. Ongoing barriers to immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception: a physician survey. Contracept Reprod Med. 2018;3:23. doi: 10.1186/s40834-018-0078-5.

- Benfield N, Hawkins F, Ray L, et al. Exposure to routine availability of immediate postpartum LARC: effect on attitudes and practices of labor and delivery and postpartum nurses. Contraception. 2018;97:411-414. doi: 10.1016 /j.contraception.2018.01.017.

- Steenland MW, Vatsa R, Pace LE, et al. Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraceptive use following statespecific changes in hospital Medicaid reimbursement. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2237918. doi: 10.1001 /jamanetworkopen.2022.37918.

- Washington CI, Jamshidi R, Thung SF, et al. Timing of postpartum intrauterine device placement: a costeffectiveness analysis. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:131-137. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.09.032

How to place an IUD with minimal patient discomfort

CASE Nulliparous young woman desires contraception

An 18-year-old nulliparous patient presents to your office inquiring about contraception before she leaves for college. She not only wants to prevent pregnancy but she also would like a method that can help with her dysmenorrhea. After receiving nondirective counseling about all of the methods available, she selects a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (LNG-IUD). However, she discloses that she is very nervous about placement. She has heard from friends that it can be painful to get an IUD. What are these patient’s risk factors for painful placement? How would you mitigate her experience of pain during the insertion process?

IUDs are highly effective and safe methods of preventing unwanted pregnancy. IUDs have become increasingly more common; they were the method of choice for 14% of contraception users in 2016, a rise from 12% in 2014.1 The Contraceptive CHOICE project demonstrated that IUDs were most likely to be chosen as a reversible method of contraception when unbiased counseling is provided and barriers such as cost are removed. Additionally, rates of continuation were found to be high, thus reducing the number of unwanted pregnancies.2 However, pain during IUD insertion as well as the fear and anxiety surrounding the procedure are some of the major limitations to IUD uptake and use. Specifically, fear of pain during IUD insertion is a substantial barrier; this fear is thought to also exacerbate the experience of pain during the insertion process.3

This article aims to identify risk factors for painful IUD placement and to review both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic methods that may decrease discomfort and anxiety during IUD insertion.

What factors contribute to the experience of pain with IUD placement?

While some women do not report experiencing pain during IUD insertion, approximately 17% describe the pain as severe.4 The perception of pain during IUD placement is multifactorial; physiologic, psychological, emotional, cultural, and circumstantial factors all can play a role (TABLE 1). The biologic perception of pain results from the manipulation of the cervix and uterus; noxious stimuli activate both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic system at T10-L2 mediates the fundus, the ovarian plexus at the cornua, and the uterosacral ligaments, while the parasympathetic fibers from S2-S4 enter the cervix at 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock and innervate the upper vagina, cervix, and lower uterine segment.4,5 Nulliparity, history of cesarean delivery, increased size of the IUD inserter, length of the uterine cavity, breastfeeding status, relation to timing of menstruation, and length of time since last vaginal delivery all may be triggers for pain. Other sociocultural influences on a patient’s experience of pain include young age (adolescence), Black race, and history of sexual trauma, as well as existing anxiety and beliefs about expected pain.3,5,6-8

It also is important to consider all aspects of the procedure that could be painful. Steps during IUD insertion that have been found to invoke average to severe pain include use of tenaculum on the cervix, uterine stabilization, uterine sounding, placement of the insertion tube, and deployment of the actual IUD.4-7

A secondary analysis of the Contraceptive CHOICE project confirmed that women with higher levels of anticipated pain were more likely to experience increased discomfort during placement.3 Providers tend to underestimate the anxiety and pain experienced by their patients undergoing IUD insertion. In a study about anticipated pain during IUD insertion, clinicians were asked if patients were “pleasant and appropriately engaging” or “anxious.” Only 10% of those patients were noted to be anxious by their provider; however, patients with a positive screen on the PHQ-4 depression and anxiety screen did anticipate more pain than those who did not.6 In another study, patients estimated their pain scores at 30 mm higher than their providers on a visual analog scale.7 Given these discrepancies, it is imperative to address anxiety and pain anticipation, risk factors for pain, and offerings for pain management during IUD placement to ensure a more holistic experience.

Continue to: What are nonpharmacologic interventions that can reduce anxiety and pain?...

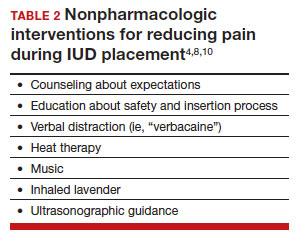

What are nonpharmacologic interventions that can reduce anxiety and pain?

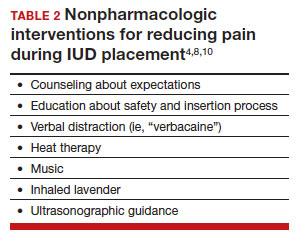

There are few formal studies on nonpharmacologic options for pain reduction at IUD insertion, with varying outcomes.4,8,10 However, many of them suggest that establishing a trusting clinician-patient relationship, a relaxing and inviting environment, and emotional support during the procedure may help make the procedure more comfortable overall (TABLE 2).4,5,10

Education and counseling

Patients should be thoroughly informed about the different IUD options, and they should be reassured regarding their contraceptive effectiveness and low risk for insertion difficulties in order to mitigate anxiety about complications and future fertility.11 This counseling session can offer the patient opportunities for relationship building with the provider and for the clinician to assess for anxiety and address concerns about the insertion and removal process. Patients who are adequately informed regarding expectations and procedural steps are more likely to have better pain management.5 Another purpose of this counseling session may be to identify any risk factors that may increase pain and tailor nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic options to the individual patient.

Environment

Examination rooms should be comfortable, private, and professional appearing. Patients prefer a more informal, unhurried, and less sterile atmosphere for procedures. Clinicians should strive to engender trust prior to the procedure by sharing information in a straightforward manner, and ensuring that staff of medical assistants, nurses, and clinicians are a “well-oiled machine” to inspire confidence in the competence of the team.4 Ultrasonography guidance also may be helpful in reducing pain during IUD placement, but this may not be available in all outpatient settings.8

Distraction techniques

Various distraction methods have been employed during gynecologic procedures, and more specifically IUD placement, with some effect. During and after the procedure, heat and ice have been found to be helpful adjuncts for uterine cramping and should be offered as first-line pain management options on the examination table. This can be in the form of reusable heating pads or chemical heat or ice packs.4 A small study demonstrated that inhaled lavender may help with lowering anxiety prior to and during the procedure; however, it had limited effects on pain.10

Clinicians and support staff should engage in conversation with the patient throughout the procedure (ie, “verbacaine”). This can be conducted via a casual chat about unrelated topics or gentle and positive coaching through the procedure with the intent to remove negative imagery associated with elements of the insertion process.5 Finally, studies have been conducted using music as a distraction for colposcopy and hysteroscopy, and results have indicated that it is beneficial, reducing both pain and anxiety during these similar types of procedures.4 While these options may not fully remove pain and anxiety, many are low investment interventions that many patients will appreciate.

What are pharmacologic interventions that can decrease pain during IUD insertion?

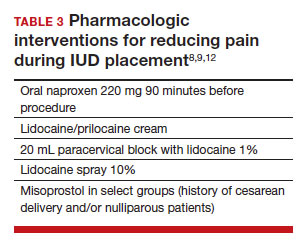

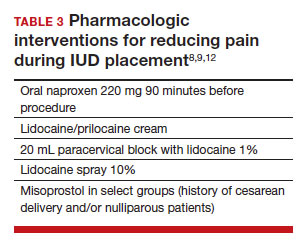

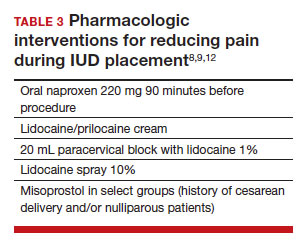

The literature is more robust with studies examining the benefits of pharmacologic methods for reducing pain during IUD insertion; strategies include agents that lessen uterine cramping, numb the cervix, and soften and open the cervical os. Despite the plethora of studies, there is no one standard of care for pain management during IUD insertion (TABLE 3).

Lidocaine injection

Lidocaine is an amine anesthetic that can block the nociceptive response of nerves upon administration; it has the advantages of rapid onset and low risk in appropriate doses. Multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have examined the use of paracervical and intracervical block with lidocaine.9,12-15 Lopez and colleagues conducted a review in 2015, including 3 studies about injectable lidocaine and demonstrated some effect of injectable lidocaine on reduction in pain at tenaculum placement.9

Mody and colleagues conducted a pilot RCT of 50 patients comparing a 10 mL lidocaine 1% paracervical block to no block, which was routine procedure at the time.12 The authors demonstrated a reduction in pain at the tenaculum site but no decrease in pain with insertion. They also measured pain during the block administration itself and found that the block increased the overall pain of the procedure. In 2018, Mody et al13 performed another RCT, but with a higher dose of 20 mL of buffered lidocaine 1% in 64 nulliparous patients. They found that paracervical block improved pain during uterine sounding, IUD insertion, and 5 minutes following insertion, as well as the pain of the overall procedure.

De Nadai and colleagues evaluated if a larger dose of lidocaine (3.6 mL of lidocaine 2%) administered intracervically at the anterior lip was beneficial.14 They randomly assigned 302 women total: 99 to intracervical block, 101 to intracervical sham block with dry needling at the anterior lip, and 102 to no intervention. Fewer patients reported extreme pain with tenaculum placement and with IUD (levonorgestrel-releasing system) insertion. Given that this option requires less lidocaine overall and fewer injection points, it has the potential to be an easier and more reproducible technique.14

Finally, Akers and colleagues aimed to evaluate IUD insertion in nulliparous adolescents. They compared a 1% paracervical block of 10 mL with 1 mL at the anterior lip and 4.5 mL at 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock in the cervicovaginal junction versus depression of the wood end of a cotton swab at the same sites. They found that the paracervical block improved pain substantially during all steps of the procedure compared with the sham block in this young population.16

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) show promise in reducing pain during IUD placement, as they inhibit the production of prostaglandins, which can in turn reduce uterine cramping and inflammation during IUD placement.

Lopez and colleagues evaluated the use of NSAIDs in 7 RCTs including oral naproxen, oral ibuprofen, and intramuscular ketorolac.9 While it had no effect on pain at the time of placement, naproxen administered at least 90 minutes before the procedure decreased uterine cramping for 2 hours after insertion. Women receiving naproxen also were less likely to describe the insertion as “unpleasant.” Ibuprofen was found to have limited effects during insertion and after the procedure. Intramuscular ketorolac studies were conflicting. Results of one study demonstrated a lower median pain score at 5 minutes but no differences during tenaculum placement or IUD insertion, whereas another demonstrated reduction in pain during and after the procedure.8,9

Another RCT showed potential benefit of tramadol over the use of naproxen when they were compared; however, tramadol is an opioid, and there are barriers to universal use in the outpatient setting.9

Continue to: Topical anesthetics...

Topical anesthetics

Topical anesthetics offer promise of pain relief without the pain of injection and with the advantage of self-administration for some formulations.

Several RCTs evaluated whether lidocaine gel 2% applied to the cervix or injected via flexible catheter into the cervical os improved pain, but there were no substantial differences in pain perception between topical gel and placebo groups in the insertion of IUDs.9

Rapkin and colleagues15 studied whether self-administered intravaginal lidocaine gel 2% five minutes before insertion was helpful;15 they found that tenaculum placement was less painful, but IUD placement was not. Conti et al expanded upon the Rapkin study by extending the amount of time of exposure to self-administered intravaginal lidocaine gel 2% to 15 minutes; they found no difference in perception of pain during tenaculum placement, but they did see a substantial difference in discomfort during speculum placement.17 This finding may be helpful for patients with a history of sexual trauma or anxiety about gynecologic examinations. Based on surveys conducted during their study, they found that patients were willing to wait 15 minutes for this benefit.