User login

Inpatient Staffing in Pediatric Programs

Resident duty hour restrictions were initially implemented in New York in 1989 with New York State Code 405 in response to a patient death in a New York City Emergency Department.1 This case initiated an evaluation of potential risks to patient safety when residents were inadequately supervised and overfatigued. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented resident duty hours nationally due to concerns for patient safety and quality of care.2 These restrictions involved the implementation of the 80‐hour work week (averaged over 4 weeks), a maximum duty length of 30 hours, and prescriptive supervision guidelines. In December 2008, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) proposed additional changes to further restrict resident duty hours which also included overnight protected sleep periods and additional days off per month.3 The ACGME responded by mandating new resident duty hour restrictions in October 2010 which will be implemented in July 2011. The ACGME's new changes include a change in the maximum duty hour length for residents in their first year of training (PGY‐1) of 16 hours. Residents in their second year of training (PGY‐2) level and above may work a maximum of 24 hours with an additional 4 hours for transition of care and resident education. The ACGME strongly recommends strategic napping, but do not have a protected overnight sleep period in place4 (Table 1).

| Current Guidelines | IOM Proposed Changes | ACGME Mandated Changes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 2008 | October 2010 | ||

| |||

| Maximum hours of work per week | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk |

| Maximum duty length | 30 hr (admitting patients for up to 24 hr, then additional 6 hr for transition of care) | 30 hr with 5 hr protected sleep period (admitting patients for up to 16 hr) | PGY‐1 residents, 16 hr |

| Or | PGY‐2 residents, 24 hr with additional 4 hr for transition of care | ||

| 16 hr with no protected sleep period | |||

| Strategic napping | None | 5 hr protected sleep period for 30 hr shifts | Highly recommended after 16 hr of continuous duty |

| Time off between duty periods | 10 hr after shift | 10 hr after day shift | Recommend 10 hr, but must have at least 8 hr off |

| 12 hr after night shift | In their final years, residents can have less than 8 hr | ||

| 14 hr after 30 hr shifts | |||

| Maximum consecutive nights of night float | None | 4 consecutive nights maximum | 6 consecutive nights maximum |

| Frequency of in‐house call | Every third night, on average | Every third night, no averaging | Every third night, no averaging |

| Days off per month | 4 days off | 5 days off, at least one 48 hr period per month | 4 days off |

| Moonlighting restrictions | Internal moonlighting counts against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap |

There is growing concern regarding the impact of these new resident duty hour restrictions on the coverage of inpatient services, particularly during the overnight period. To our knowledge, there is no published national data on how pediatric inpatient teaching services are staffed at night. The objective of this study was to survey the current landscape of pediatric resident coverage of noncritical care inpatient teaching services. In addition, we sought to explore how changes in work hour restrictions might affect the role of pediatric hospitalists in training programs.

METHODS

We developed an institutional review board (IRB)‐approved Web‐based electronic survey. The survey consisted of 17 questions. The survey obtained information regarding the demographics of the program including: number of residents, daily patient census per ward intern, information regarding staff‐only pediatric ward services, overnight coverage, and current attending in‐house overnight coverage (see Appendix). We also examined the prevalence of pediatric hospitalists in training programs, their current role in staffing patients, and how that role may change with the implementation of additional resident duty hour restrictions. Initially, the survey was reviewed and tested by several pediatric hospitalists and program directors. It was then reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Director (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent out to 196 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in January 2010. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or specifically designating someone else to complete it. Two reminders were sent. We then sent an additional request for program participation on the pediatric hospitalist listserve. All data was collected by February 2010.

RESULTS

One hundred twenty unique responses were received (61% of total pediatric residency programs). As of 2009, this represented 5201 pediatric residents (58% of total pediatric residents). The average program size was 43 residents (range: 12‐156 residents, median 43). The average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours was 6.65 patients (range: 3‐17, median 6). Twenty percent of training programs had staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward services during daytime hours. In the programs with both staff‐only and resident pediatric ward services, only 19% of patients were covered by the staff‐only teams and 81% of patients were covered by resident teams.

During the overnight period, 86% of resident teams did not have caps on the number of new patient admissions. An average of 3.6 providers per training program were in‐house overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards. Ninety‐four percent of these providers in‐house were residents (399 residents in‐house/425 total providers in‐house each night).

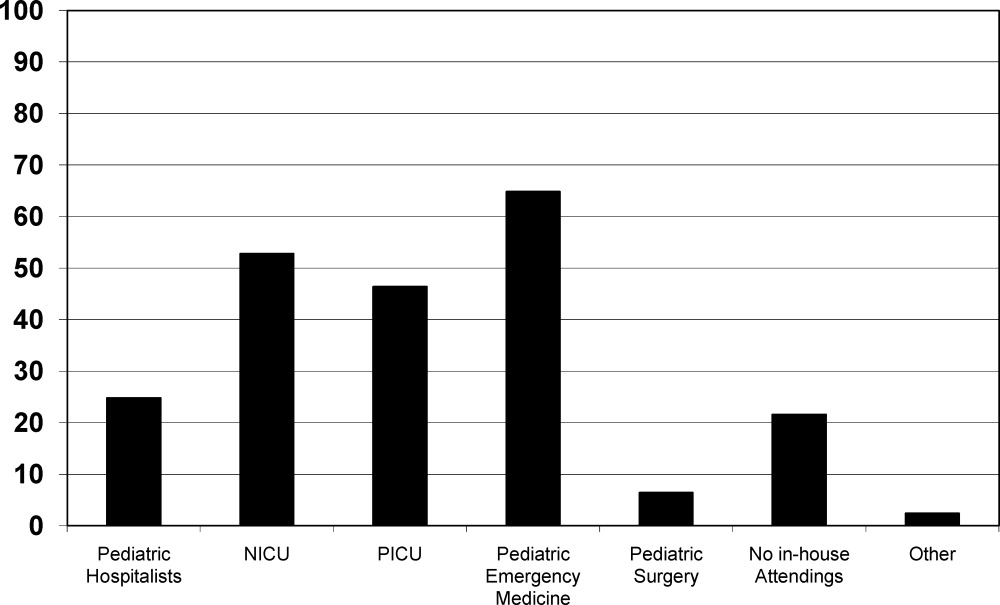

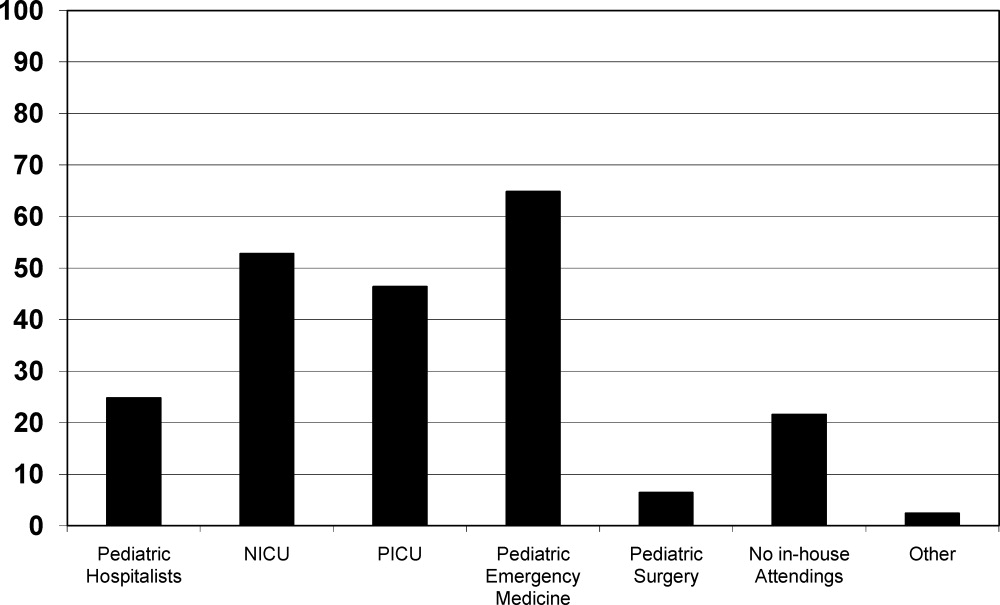

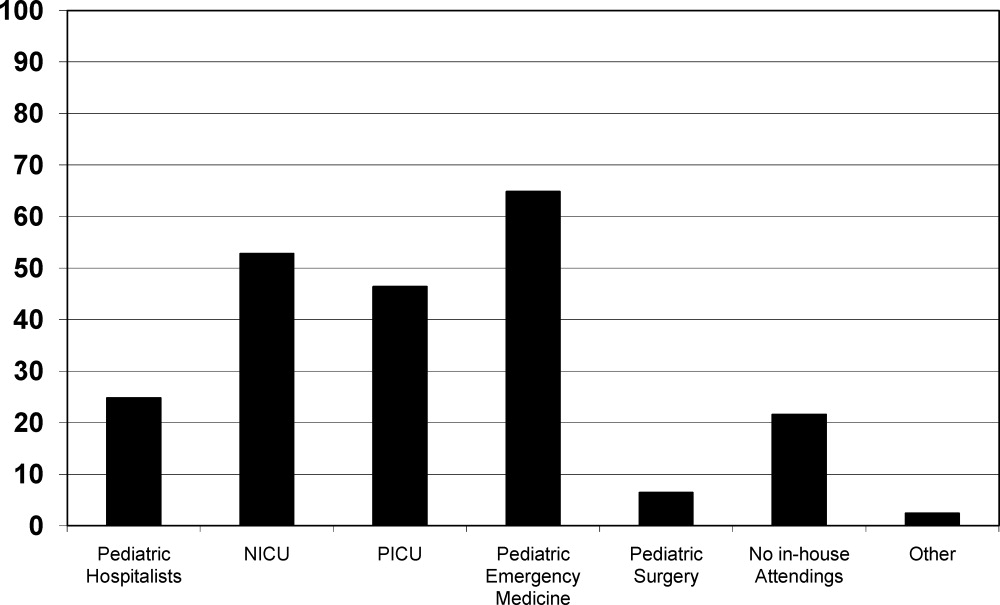

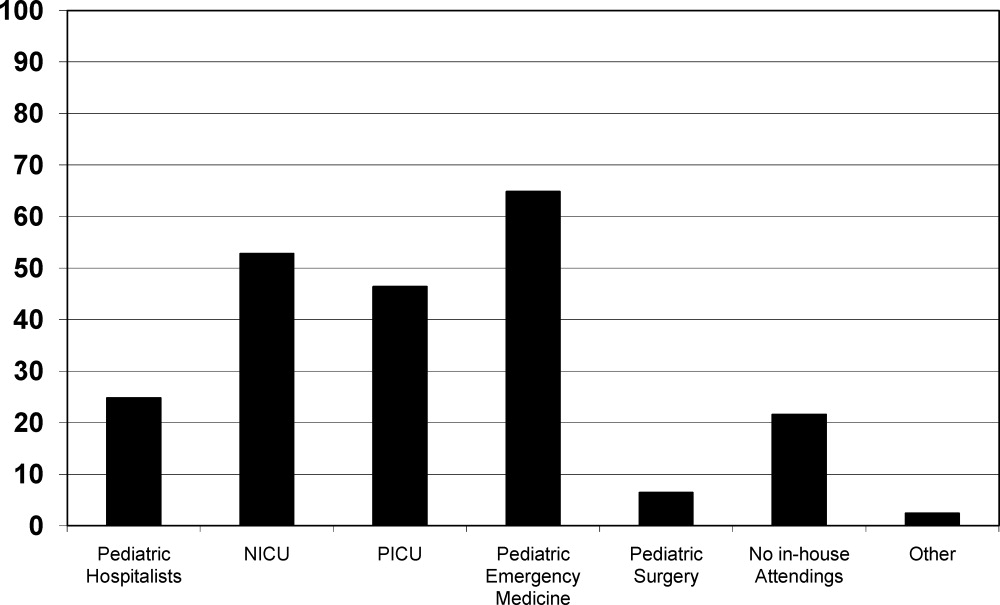

Twenty‐five percent of the training programs that responded to the survey had pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night. This included both overnight and partial nights (ie, until midnight). Other attendings in‐house at night include: neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) attendings (53% of programs), pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) attendings (46% of programs), Pediatric Emergency Medicine attendings (65% of programs), and Pediatric Surgery attendings (6.4% of programs). Twenty‐two percent of programs had no in‐house attendings at night (Figure 1).

Pediatric hospitalists were involved with 84% (n = 97) of training programs. Sixty percent (n = 58) of the pediatric hospitalist teams were staffed with both teaching attendings and residents. Fourteen percent (n = 14) of the pediatric hospitalist teams did not involve residents (staff‐only) and 25% (n = 25) had both types of teams. Specifically, of the programs that had pediatric hospitalists, 20% (n = 19) of them had hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day and 13% (n = 12) of teams had hospitalist attendings in‐house into the evening hours for a varying amount of time. Of the programs with hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day, 52% (n = 11) had started this coverage within the past 3 years.

Looking towards the future, and prior to the enactment of the October 2010 ACGME standards, 31% (n = 35) of the training programs that lacked 24/7 hospitalist in‐house coverage in January 2010 anticipated adding this level of coverage within the next 5 years. Notably, 70% (n = 81) of training programs felt that further resident work hour restrictions, which have since been enacted, would likely require the addition of more hospitalist attendings at night. Our survey allowed program directors to make open‐ended comments on how further work hour restrictions may change inpatient staffing in noncritical care inpatient teaching services.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this was the first national study of pediatric resident coverage in noncritical care inpatient teaching services. While there was significant variation in how inpatient teaching services were covered across these programs, in January 2010, residents were involved in the majority of patient care with only 20% of programs having attending‐only hospitalist teams during the daytime. During the overnight period, the proportion of patient care provided by residents became even more significant with residents representing 94% of the total in‐house providers accepting new admissions. While pediatric hospitalists were prevalent at these training programs, their role in direct patient care overnight was limited. Only 6% of total in‐house providers accepting admissions at night were pediatric hospitalists.

The comments made by program directors are representative of the overall concerns regarding changes to resident work hours (see Table 2). In a position statement by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors in regards to the IOM recommendations, concerns were raised stating that the recommendations of the IOM Committee are intended to enhance patient safety without appropriate consideration for the educational and professional development of trainees.5 While the newly mandated ACGME standards are different than the previous IOM recommendations, it is clear that there will be very significant changes to accommodate these new standards. Our study was done prior to the new ACGME's standards. At the time of the survey, less than a third of programs were anticipating the addition of 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage; however, if resident work hours were further restricted, 70% of programs felt that additional hospitalists would be needed. This is a significant increase in the previously anticipated need for overnight attending hospitalist coverage, especially in light of the further restrictions mandated by the ACGME. We know that the response of New York State programs to the 405 regulations varied by program size, but all made significant changes to accommodate the new standards.6 It is clear that many program directors nationally are anticipating significant changes to their residencies when these new restrictions are enacted. The respondents in our survey felt that pediatric hospitalists are going to have to play an even bigger role at night when additional resident work hour restrictions are put into place.

|

| ▪ If the new duty hours are mandated, we would have to go to a night float system to be in compliance. This would require more residents and we do not have the funding to hire more residents. |

| ▪ Restrictions will be costly. It will increase shift work mentality, and increase pt errors due to handovers. If these (work restrictions) are not applied to all doctors (neurosurgeons, ICU doctors), they should not apply to resident doctors. |

| ▪ The additional restrictions may make the hospital consider giving up its residency program in favor of a hospitalist‐only model. |

| ▪ We do not have enough residents to care for the current patient load. |

| ▪ Additional work hour restrictions will lead to more hand‐over care and less ownership of patients by residents who identify themselves as primary patient physicians. Both situations are associated with increased rates of complications and possible sentinel events. |

| ▪ If the hours are reduced, the hospital will be forced to hire physicians for the care of patients. The administration of the hospital is now beginning to ask why they should financially support the training program if the residents are not providing a substantial portion of the hospital care for the patients. |

Pediatric hospital medicine remains a rapidly growing field.7 Eighty‐four percent of pediatric training programs utilize pediatric hospitalists. Over 60% of these pediatric hospitalist teams are involved in teaching teams with residents. While we did not directly study the supply and demand of pediatric hospitalists, there is some concern that even despite its rapid growth, the supply of pediatric hospitalists will not keep up with the demand when further resident work hours restrictions are implemented. At time of submission, a cost‐analysis has not yet been publicly published on the ACGME's new changes. There is data available based on the IOM's 2008 recommendations. A study by Nuckols and Escarce8 suggests that if the IOM's recommendations were implemented, the entire healthcare system nationally would have to develop and fill new full‐time positions equal to 5001 attending physicians, 5984 midlevel providers (nurse practitioners or physician assistants), 320 licensed vocational nurses, 229 nursing aides, and 45 laboratory technicians. This would be equivalent to adding an additional 8247 residency positions across all specialties.810 While the ACGME's new mandated changes are different than the IOM's recommendations, they will also restrict resident duty hours that we believe could lead to gaps in patient care requiring significant personnel changes in the healthcare system.

There are several limitations to our study. We did not study the role of pediatric subspecialty fellows and their involvement in pediatric inpatient services in these training programs. We also did not study the prevalence and use of resident night float systems. While night floats may be used in some programs, it may become more prevalent with the possible restriction in intern work hours down to 16 hours. As with any survey, there remains both volunteer and nonresponse bias with the programs that decide to complete or disregard the survey. Finally, there remains some concern over the data collection after the survey was sent out to the hospitalist listserve. Pediatric hospitalists may have incorrectly filled out the data for their program after their program director had already completed the survey. We attempted to minimize this problem by specifically instructing hospitalists to encourage their program director to fill out the survey if they had not already done so. We also compared computer Internet Protocol (IP) addresses and actual program responses, before and after the hospitalist e‐mail was sent, in an attempt to minimize the chance of including duplicated responses from the same program. Lastly, the January 2010 survey predated the October 2010 ACGME response to the IOM recommendations, and the responses may be different now that the specific restrictions have been mandated with an actual implementation date.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that pediatric teaching services varied significantly in how they provided overnight coverage in 2010 prior to new ACGME recommendations. Overall, residents were providing the overwhelming majority of the patient care overnight in pediatric training programs. While hospitalists were prevalent in pediatric training programs, in 2010 they had limited roles in direct patient care at night. The ACGME has now mandated additional residency work hour restrictions to be implemented July 2011. With these restrictions, hospitalists will likely need to expand their services, and additional hospitalists will be needed to provide overnight coverage. It is unclear where those hospitalists will come from and what their role will be. It is also unclear what the impact of increased demand and changed job description will be on the continued evolution of the field of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Future work needs to be done to establish benchmarks for inpatient coverage. The benchmarks could include guidelines on balancing patient safety with resident education. This may also involve the implementation of resident night float models. There needs to be monitoring on how changes in resident work hours and staffing affect coverage and, ultimately, how changes affect patient and resident outcomes.

APPENDIX

INPATIENT STAFFING WITHIN PEDIATRIC RESIDENCY PROGRAMS SURVEY

|

| Demographics |

| How many residents are in your residency program? (total, categorical, Med‐Peds, other combined Peds) |

| What is your average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours? |

| Does your hospital have a staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward service during the daytime hours? |

| If your hospital has a staff‐only pediatric ward service, what are the proportion of patients cared for by residents vs staff‐only during daytime hours? |

| Do your residents cap the number of new patient admissions at night? |

| Providers in‐house overnight |

| How many providers do you have in‐house at night until midnight/overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards? (residents, hospitalists, nurse practitioners, other) |

| Do you have attendings in‐house at night? (pediatric hospitalists, NICU, PICU, Peds EM, Peds Surgery, no attendings, other) |

| Pediatric hospitalists |

| Does your hospital have pediatric hospitalists? |

| Are your pediatric hospitalist teams staffed by: (teaching attendings and residents, hospitalist‐staff only, both) |

| If you have a staff‐only hospitalist team (no residents), how long has it been in existence? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years) |

| Are your hospitalist attendings in‐house: (daytime only, 24 hours/day, other) |

| If your hospitalist attendings are in‐house 24/7, how many years has that coverage been available? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years, not available) |

| Future pediatric hospitalist coverage |

| Do you anticipate that your hospital will be adding 24/7 hospitalist attending coverage? (next year, next 2 years, next 5 years, not anticipating adding coverage, 24/7 hospitalist coverage already in place) |

| In your opinion, would further resident work hour restrictions make your hospital more likely to add additional hospitalist attendings at night? (very likely, somewhat likely, neutral, not likely) |

- ,.The Bell Commission: ethical implications for the training of physicians.Mt Sinai J Med.2000;67(2):136–139.

- ,.Restricted duty hours for surgeons and impact on residents quality of life, education, and patient care: a literature review.Patient Saf Surg.2009;3(1):3.

- Institute of Medicine. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Released December 02, 2008. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2008/Resident‐Duty‐Hours‐Enhancing‐Sleep‐Supervision‐and‐Safety.aspx. Accessed September 20,2009.

- ACGME 2010 Standards “Common Program Requirements.” Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/pdf/Common_Program_ Requirements_07012011.pdf. Accessed January 27,2011.

- Association of Pediatric Program Directors. Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) Position Statement in Response to the IOM Recommendations on Resident Duty Hours.2009. Available at: http://www.appd.org/PDFs/APPD _IOM%20 _Duty _Hours _Report _Position _Paper _4–30‐09.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- ,,,,.Lessons learned from New York state: fourteen years of experience with work hour limitations.Acad Med.2005;80(5):467–472.

- ,,,.Health care market trends and the evolution of hospitalist use and rolesJ Gen Intern Med.2005;20(2):101–107.

- ,,,,.Cost implications of reduced work hours and workloads for resident physicians.N Engl J Med.2009;360:2202–2215.

- .Revisiting duty‐hour length—IOM recommendations for patient safety and resident education.N Engl J Med.2008;359:2633–2635.

- ,,,.Resident duty hour restrictions: is less really more?J Pediatr.2009;154:631–632.

Resident duty hour restrictions were initially implemented in New York in 1989 with New York State Code 405 in response to a patient death in a New York City Emergency Department.1 This case initiated an evaluation of potential risks to patient safety when residents were inadequately supervised and overfatigued. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented resident duty hours nationally due to concerns for patient safety and quality of care.2 These restrictions involved the implementation of the 80‐hour work week (averaged over 4 weeks), a maximum duty length of 30 hours, and prescriptive supervision guidelines. In December 2008, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) proposed additional changes to further restrict resident duty hours which also included overnight protected sleep periods and additional days off per month.3 The ACGME responded by mandating new resident duty hour restrictions in October 2010 which will be implemented in July 2011. The ACGME's new changes include a change in the maximum duty hour length for residents in their first year of training (PGY‐1) of 16 hours. Residents in their second year of training (PGY‐2) level and above may work a maximum of 24 hours with an additional 4 hours for transition of care and resident education. The ACGME strongly recommends strategic napping, but do not have a protected overnight sleep period in place4 (Table 1).

| Current Guidelines | IOM Proposed Changes | ACGME Mandated Changes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 2008 | October 2010 | ||

| |||

| Maximum hours of work per week | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk |

| Maximum duty length | 30 hr (admitting patients for up to 24 hr, then additional 6 hr for transition of care) | 30 hr with 5 hr protected sleep period (admitting patients for up to 16 hr) | PGY‐1 residents, 16 hr |

| Or | PGY‐2 residents, 24 hr with additional 4 hr for transition of care | ||

| 16 hr with no protected sleep period | |||

| Strategic napping | None | 5 hr protected sleep period for 30 hr shifts | Highly recommended after 16 hr of continuous duty |

| Time off between duty periods | 10 hr after shift | 10 hr after day shift | Recommend 10 hr, but must have at least 8 hr off |

| 12 hr after night shift | In their final years, residents can have less than 8 hr | ||

| 14 hr after 30 hr shifts | |||

| Maximum consecutive nights of night float | None | 4 consecutive nights maximum | 6 consecutive nights maximum |

| Frequency of in‐house call | Every third night, on average | Every third night, no averaging | Every third night, no averaging |

| Days off per month | 4 days off | 5 days off, at least one 48 hr period per month | 4 days off |

| Moonlighting restrictions | Internal moonlighting counts against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap |

There is growing concern regarding the impact of these new resident duty hour restrictions on the coverage of inpatient services, particularly during the overnight period. To our knowledge, there is no published national data on how pediatric inpatient teaching services are staffed at night. The objective of this study was to survey the current landscape of pediatric resident coverage of noncritical care inpatient teaching services. In addition, we sought to explore how changes in work hour restrictions might affect the role of pediatric hospitalists in training programs.

METHODS

We developed an institutional review board (IRB)‐approved Web‐based electronic survey. The survey consisted of 17 questions. The survey obtained information regarding the demographics of the program including: number of residents, daily patient census per ward intern, information regarding staff‐only pediatric ward services, overnight coverage, and current attending in‐house overnight coverage (see Appendix). We also examined the prevalence of pediatric hospitalists in training programs, their current role in staffing patients, and how that role may change with the implementation of additional resident duty hour restrictions. Initially, the survey was reviewed and tested by several pediatric hospitalists and program directors. It was then reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Director (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent out to 196 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in January 2010. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or specifically designating someone else to complete it. Two reminders were sent. We then sent an additional request for program participation on the pediatric hospitalist listserve. All data was collected by February 2010.

RESULTS

One hundred twenty unique responses were received (61% of total pediatric residency programs). As of 2009, this represented 5201 pediatric residents (58% of total pediatric residents). The average program size was 43 residents (range: 12‐156 residents, median 43). The average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours was 6.65 patients (range: 3‐17, median 6). Twenty percent of training programs had staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward services during daytime hours. In the programs with both staff‐only and resident pediatric ward services, only 19% of patients were covered by the staff‐only teams and 81% of patients were covered by resident teams.

During the overnight period, 86% of resident teams did not have caps on the number of new patient admissions. An average of 3.6 providers per training program were in‐house overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards. Ninety‐four percent of these providers in‐house were residents (399 residents in‐house/425 total providers in‐house each night).

Twenty‐five percent of the training programs that responded to the survey had pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night. This included both overnight and partial nights (ie, until midnight). Other attendings in‐house at night include: neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) attendings (53% of programs), pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) attendings (46% of programs), Pediatric Emergency Medicine attendings (65% of programs), and Pediatric Surgery attendings (6.4% of programs). Twenty‐two percent of programs had no in‐house attendings at night (Figure 1).

Pediatric hospitalists were involved with 84% (n = 97) of training programs. Sixty percent (n = 58) of the pediatric hospitalist teams were staffed with both teaching attendings and residents. Fourteen percent (n = 14) of the pediatric hospitalist teams did not involve residents (staff‐only) and 25% (n = 25) had both types of teams. Specifically, of the programs that had pediatric hospitalists, 20% (n = 19) of them had hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day and 13% (n = 12) of teams had hospitalist attendings in‐house into the evening hours for a varying amount of time. Of the programs with hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day, 52% (n = 11) had started this coverage within the past 3 years.

Looking towards the future, and prior to the enactment of the October 2010 ACGME standards, 31% (n = 35) of the training programs that lacked 24/7 hospitalist in‐house coverage in January 2010 anticipated adding this level of coverage within the next 5 years. Notably, 70% (n = 81) of training programs felt that further resident work hour restrictions, which have since been enacted, would likely require the addition of more hospitalist attendings at night. Our survey allowed program directors to make open‐ended comments on how further work hour restrictions may change inpatient staffing in noncritical care inpatient teaching services.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this was the first national study of pediatric resident coverage in noncritical care inpatient teaching services. While there was significant variation in how inpatient teaching services were covered across these programs, in January 2010, residents were involved in the majority of patient care with only 20% of programs having attending‐only hospitalist teams during the daytime. During the overnight period, the proportion of patient care provided by residents became even more significant with residents representing 94% of the total in‐house providers accepting new admissions. While pediatric hospitalists were prevalent at these training programs, their role in direct patient care overnight was limited. Only 6% of total in‐house providers accepting admissions at night were pediatric hospitalists.

The comments made by program directors are representative of the overall concerns regarding changes to resident work hours (see Table 2). In a position statement by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors in regards to the IOM recommendations, concerns were raised stating that the recommendations of the IOM Committee are intended to enhance patient safety without appropriate consideration for the educational and professional development of trainees.5 While the newly mandated ACGME standards are different than the previous IOM recommendations, it is clear that there will be very significant changes to accommodate these new standards. Our study was done prior to the new ACGME's standards. At the time of the survey, less than a third of programs were anticipating the addition of 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage; however, if resident work hours were further restricted, 70% of programs felt that additional hospitalists would be needed. This is a significant increase in the previously anticipated need for overnight attending hospitalist coverage, especially in light of the further restrictions mandated by the ACGME. We know that the response of New York State programs to the 405 regulations varied by program size, but all made significant changes to accommodate the new standards.6 It is clear that many program directors nationally are anticipating significant changes to their residencies when these new restrictions are enacted. The respondents in our survey felt that pediatric hospitalists are going to have to play an even bigger role at night when additional resident work hour restrictions are put into place.

|

| ▪ If the new duty hours are mandated, we would have to go to a night float system to be in compliance. This would require more residents and we do not have the funding to hire more residents. |

| ▪ Restrictions will be costly. It will increase shift work mentality, and increase pt errors due to handovers. If these (work restrictions) are not applied to all doctors (neurosurgeons, ICU doctors), they should not apply to resident doctors. |

| ▪ The additional restrictions may make the hospital consider giving up its residency program in favor of a hospitalist‐only model. |

| ▪ We do not have enough residents to care for the current patient load. |

| ▪ Additional work hour restrictions will lead to more hand‐over care and less ownership of patients by residents who identify themselves as primary patient physicians. Both situations are associated with increased rates of complications and possible sentinel events. |

| ▪ If the hours are reduced, the hospital will be forced to hire physicians for the care of patients. The administration of the hospital is now beginning to ask why they should financially support the training program if the residents are not providing a substantial portion of the hospital care for the patients. |

Pediatric hospital medicine remains a rapidly growing field.7 Eighty‐four percent of pediatric training programs utilize pediatric hospitalists. Over 60% of these pediatric hospitalist teams are involved in teaching teams with residents. While we did not directly study the supply and demand of pediatric hospitalists, there is some concern that even despite its rapid growth, the supply of pediatric hospitalists will not keep up with the demand when further resident work hours restrictions are implemented. At time of submission, a cost‐analysis has not yet been publicly published on the ACGME's new changes. There is data available based on the IOM's 2008 recommendations. A study by Nuckols and Escarce8 suggests that if the IOM's recommendations were implemented, the entire healthcare system nationally would have to develop and fill new full‐time positions equal to 5001 attending physicians, 5984 midlevel providers (nurse practitioners or physician assistants), 320 licensed vocational nurses, 229 nursing aides, and 45 laboratory technicians. This would be equivalent to adding an additional 8247 residency positions across all specialties.810 While the ACGME's new mandated changes are different than the IOM's recommendations, they will also restrict resident duty hours that we believe could lead to gaps in patient care requiring significant personnel changes in the healthcare system.

There are several limitations to our study. We did not study the role of pediatric subspecialty fellows and their involvement in pediatric inpatient services in these training programs. We also did not study the prevalence and use of resident night float systems. While night floats may be used in some programs, it may become more prevalent with the possible restriction in intern work hours down to 16 hours. As with any survey, there remains both volunteer and nonresponse bias with the programs that decide to complete or disregard the survey. Finally, there remains some concern over the data collection after the survey was sent out to the hospitalist listserve. Pediatric hospitalists may have incorrectly filled out the data for their program after their program director had already completed the survey. We attempted to minimize this problem by specifically instructing hospitalists to encourage their program director to fill out the survey if they had not already done so. We also compared computer Internet Protocol (IP) addresses and actual program responses, before and after the hospitalist e‐mail was sent, in an attempt to minimize the chance of including duplicated responses from the same program. Lastly, the January 2010 survey predated the October 2010 ACGME response to the IOM recommendations, and the responses may be different now that the specific restrictions have been mandated with an actual implementation date.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that pediatric teaching services varied significantly in how they provided overnight coverage in 2010 prior to new ACGME recommendations. Overall, residents were providing the overwhelming majority of the patient care overnight in pediatric training programs. While hospitalists were prevalent in pediatric training programs, in 2010 they had limited roles in direct patient care at night. The ACGME has now mandated additional residency work hour restrictions to be implemented July 2011. With these restrictions, hospitalists will likely need to expand their services, and additional hospitalists will be needed to provide overnight coverage. It is unclear where those hospitalists will come from and what their role will be. It is also unclear what the impact of increased demand and changed job description will be on the continued evolution of the field of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Future work needs to be done to establish benchmarks for inpatient coverage. The benchmarks could include guidelines on balancing patient safety with resident education. This may also involve the implementation of resident night float models. There needs to be monitoring on how changes in resident work hours and staffing affect coverage and, ultimately, how changes affect patient and resident outcomes.

APPENDIX

INPATIENT STAFFING WITHIN PEDIATRIC RESIDENCY PROGRAMS SURVEY

|

| Demographics |

| How many residents are in your residency program? (total, categorical, Med‐Peds, other combined Peds) |

| What is your average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours? |

| Does your hospital have a staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward service during the daytime hours? |

| If your hospital has a staff‐only pediatric ward service, what are the proportion of patients cared for by residents vs staff‐only during daytime hours? |

| Do your residents cap the number of new patient admissions at night? |

| Providers in‐house overnight |

| How many providers do you have in‐house at night until midnight/overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards? (residents, hospitalists, nurse practitioners, other) |

| Do you have attendings in‐house at night? (pediatric hospitalists, NICU, PICU, Peds EM, Peds Surgery, no attendings, other) |

| Pediatric hospitalists |

| Does your hospital have pediatric hospitalists? |

| Are your pediatric hospitalist teams staffed by: (teaching attendings and residents, hospitalist‐staff only, both) |

| If you have a staff‐only hospitalist team (no residents), how long has it been in existence? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years) |

| Are your hospitalist attendings in‐house: (daytime only, 24 hours/day, other) |

| If your hospitalist attendings are in‐house 24/7, how many years has that coverage been available? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years, not available) |

| Future pediatric hospitalist coverage |

| Do you anticipate that your hospital will be adding 24/7 hospitalist attending coverage? (next year, next 2 years, next 5 years, not anticipating adding coverage, 24/7 hospitalist coverage already in place) |

| In your opinion, would further resident work hour restrictions make your hospital more likely to add additional hospitalist attendings at night? (very likely, somewhat likely, neutral, not likely) |

Resident duty hour restrictions were initially implemented in New York in 1989 with New York State Code 405 in response to a patient death in a New York City Emergency Department.1 This case initiated an evaluation of potential risks to patient safety when residents were inadequately supervised and overfatigued. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented resident duty hours nationally due to concerns for patient safety and quality of care.2 These restrictions involved the implementation of the 80‐hour work week (averaged over 4 weeks), a maximum duty length of 30 hours, and prescriptive supervision guidelines. In December 2008, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) proposed additional changes to further restrict resident duty hours which also included overnight protected sleep periods and additional days off per month.3 The ACGME responded by mandating new resident duty hour restrictions in October 2010 which will be implemented in July 2011. The ACGME's new changes include a change in the maximum duty hour length for residents in their first year of training (PGY‐1) of 16 hours. Residents in their second year of training (PGY‐2) level and above may work a maximum of 24 hours with an additional 4 hours for transition of care and resident education. The ACGME strongly recommends strategic napping, but do not have a protected overnight sleep period in place4 (Table 1).

| Current Guidelines | IOM Proposed Changes | ACGME Mandated Changes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 2008 | October 2010 | ||

| |||

| Maximum hours of work per week | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk | 80 hr averaged over 4 wk |

| Maximum duty length | 30 hr (admitting patients for up to 24 hr, then additional 6 hr for transition of care) | 30 hr with 5 hr protected sleep period (admitting patients for up to 16 hr) | PGY‐1 residents, 16 hr |

| Or | PGY‐2 residents, 24 hr with additional 4 hr for transition of care | ||

| 16 hr with no protected sleep period | |||

| Strategic napping | None | 5 hr protected sleep period for 30 hr shifts | Highly recommended after 16 hr of continuous duty |

| Time off between duty periods | 10 hr after shift | 10 hr after day shift | Recommend 10 hr, but must have at least 8 hr off |

| 12 hr after night shift | In their final years, residents can have less than 8 hr | ||

| 14 hr after 30 hr shifts | |||

| Maximum consecutive nights of night float | None | 4 consecutive nights maximum | 6 consecutive nights maximum |

| Frequency of in‐house call | Every third night, on average | Every third night, no averaging | Every third night, no averaging |

| Days off per month | 4 days off | 5 days off, at least one 48 hr period per month | 4 days off |

| Moonlighting restrictions | Internal moonlighting counts against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap | Both internal and external moonlighting count against 80 hr cap |

There is growing concern regarding the impact of these new resident duty hour restrictions on the coverage of inpatient services, particularly during the overnight period. To our knowledge, there is no published national data on how pediatric inpatient teaching services are staffed at night. The objective of this study was to survey the current landscape of pediatric resident coverage of noncritical care inpatient teaching services. In addition, we sought to explore how changes in work hour restrictions might affect the role of pediatric hospitalists in training programs.

METHODS

We developed an institutional review board (IRB)‐approved Web‐based electronic survey. The survey consisted of 17 questions. The survey obtained information regarding the demographics of the program including: number of residents, daily patient census per ward intern, information regarding staff‐only pediatric ward services, overnight coverage, and current attending in‐house overnight coverage (see Appendix). We also examined the prevalence of pediatric hospitalists in training programs, their current role in staffing patients, and how that role may change with the implementation of additional resident duty hour restrictions. Initially, the survey was reviewed and tested by several pediatric hospitalists and program directors. It was then reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Director (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent out to 196 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in January 2010. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or specifically designating someone else to complete it. Two reminders were sent. We then sent an additional request for program participation on the pediatric hospitalist listserve. All data was collected by February 2010.

RESULTS

One hundred twenty unique responses were received (61% of total pediatric residency programs). As of 2009, this represented 5201 pediatric residents (58% of total pediatric residents). The average program size was 43 residents (range: 12‐156 residents, median 43). The average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours was 6.65 patients (range: 3‐17, median 6). Twenty percent of training programs had staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward services during daytime hours. In the programs with both staff‐only and resident pediatric ward services, only 19% of patients were covered by the staff‐only teams and 81% of patients were covered by resident teams.

During the overnight period, 86% of resident teams did not have caps on the number of new patient admissions. An average of 3.6 providers per training program were in‐house overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards. Ninety‐four percent of these providers in‐house were residents (399 residents in‐house/425 total providers in‐house each night).

Twenty‐five percent of the training programs that responded to the survey had pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night. This included both overnight and partial nights (ie, until midnight). Other attendings in‐house at night include: neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) attendings (53% of programs), pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) attendings (46% of programs), Pediatric Emergency Medicine attendings (65% of programs), and Pediatric Surgery attendings (6.4% of programs). Twenty‐two percent of programs had no in‐house attendings at night (Figure 1).

Pediatric hospitalists were involved with 84% (n = 97) of training programs. Sixty percent (n = 58) of the pediatric hospitalist teams were staffed with both teaching attendings and residents. Fourteen percent (n = 14) of the pediatric hospitalist teams did not involve residents (staff‐only) and 25% (n = 25) had both types of teams. Specifically, of the programs that had pediatric hospitalists, 20% (n = 19) of them had hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day and 13% (n = 12) of teams had hospitalist attendings in‐house into the evening hours for a varying amount of time. Of the programs with hospitalist attendings in‐house 24 hours per day, 52% (n = 11) had started this coverage within the past 3 years.

Looking towards the future, and prior to the enactment of the October 2010 ACGME standards, 31% (n = 35) of the training programs that lacked 24/7 hospitalist in‐house coverage in January 2010 anticipated adding this level of coverage within the next 5 years. Notably, 70% (n = 81) of training programs felt that further resident work hour restrictions, which have since been enacted, would likely require the addition of more hospitalist attendings at night. Our survey allowed program directors to make open‐ended comments on how further work hour restrictions may change inpatient staffing in noncritical care inpatient teaching services.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this was the first national study of pediatric resident coverage in noncritical care inpatient teaching services. While there was significant variation in how inpatient teaching services were covered across these programs, in January 2010, residents were involved in the majority of patient care with only 20% of programs having attending‐only hospitalist teams during the daytime. During the overnight period, the proportion of patient care provided by residents became even more significant with residents representing 94% of the total in‐house providers accepting new admissions. While pediatric hospitalists were prevalent at these training programs, their role in direct patient care overnight was limited. Only 6% of total in‐house providers accepting admissions at night were pediatric hospitalists.

The comments made by program directors are representative of the overall concerns regarding changes to resident work hours (see Table 2). In a position statement by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors in regards to the IOM recommendations, concerns were raised stating that the recommendations of the IOM Committee are intended to enhance patient safety without appropriate consideration for the educational and professional development of trainees.5 While the newly mandated ACGME standards are different than the previous IOM recommendations, it is clear that there will be very significant changes to accommodate these new standards. Our study was done prior to the new ACGME's standards. At the time of the survey, less than a third of programs were anticipating the addition of 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage; however, if resident work hours were further restricted, 70% of programs felt that additional hospitalists would be needed. This is a significant increase in the previously anticipated need for overnight attending hospitalist coverage, especially in light of the further restrictions mandated by the ACGME. We know that the response of New York State programs to the 405 regulations varied by program size, but all made significant changes to accommodate the new standards.6 It is clear that many program directors nationally are anticipating significant changes to their residencies when these new restrictions are enacted. The respondents in our survey felt that pediatric hospitalists are going to have to play an even bigger role at night when additional resident work hour restrictions are put into place.

|

| ▪ If the new duty hours are mandated, we would have to go to a night float system to be in compliance. This would require more residents and we do not have the funding to hire more residents. |

| ▪ Restrictions will be costly. It will increase shift work mentality, and increase pt errors due to handovers. If these (work restrictions) are not applied to all doctors (neurosurgeons, ICU doctors), they should not apply to resident doctors. |

| ▪ The additional restrictions may make the hospital consider giving up its residency program in favor of a hospitalist‐only model. |

| ▪ We do not have enough residents to care for the current patient load. |

| ▪ Additional work hour restrictions will lead to more hand‐over care and less ownership of patients by residents who identify themselves as primary patient physicians. Both situations are associated with increased rates of complications and possible sentinel events. |

| ▪ If the hours are reduced, the hospital will be forced to hire physicians for the care of patients. The administration of the hospital is now beginning to ask why they should financially support the training program if the residents are not providing a substantial portion of the hospital care for the patients. |

Pediatric hospital medicine remains a rapidly growing field.7 Eighty‐four percent of pediatric training programs utilize pediatric hospitalists. Over 60% of these pediatric hospitalist teams are involved in teaching teams with residents. While we did not directly study the supply and demand of pediatric hospitalists, there is some concern that even despite its rapid growth, the supply of pediatric hospitalists will not keep up with the demand when further resident work hours restrictions are implemented. At time of submission, a cost‐analysis has not yet been publicly published on the ACGME's new changes. There is data available based on the IOM's 2008 recommendations. A study by Nuckols and Escarce8 suggests that if the IOM's recommendations were implemented, the entire healthcare system nationally would have to develop and fill new full‐time positions equal to 5001 attending physicians, 5984 midlevel providers (nurse practitioners or physician assistants), 320 licensed vocational nurses, 229 nursing aides, and 45 laboratory technicians. This would be equivalent to adding an additional 8247 residency positions across all specialties.810 While the ACGME's new mandated changes are different than the IOM's recommendations, they will also restrict resident duty hours that we believe could lead to gaps in patient care requiring significant personnel changes in the healthcare system.

There are several limitations to our study. We did not study the role of pediatric subspecialty fellows and their involvement in pediatric inpatient services in these training programs. We also did not study the prevalence and use of resident night float systems. While night floats may be used in some programs, it may become more prevalent with the possible restriction in intern work hours down to 16 hours. As with any survey, there remains both volunteer and nonresponse bias with the programs that decide to complete or disregard the survey. Finally, there remains some concern over the data collection after the survey was sent out to the hospitalist listserve. Pediatric hospitalists may have incorrectly filled out the data for their program after their program director had already completed the survey. We attempted to minimize this problem by specifically instructing hospitalists to encourage their program director to fill out the survey if they had not already done so. We also compared computer Internet Protocol (IP) addresses and actual program responses, before and after the hospitalist e‐mail was sent, in an attempt to minimize the chance of including duplicated responses from the same program. Lastly, the January 2010 survey predated the October 2010 ACGME response to the IOM recommendations, and the responses may be different now that the specific restrictions have been mandated with an actual implementation date.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that pediatric teaching services varied significantly in how they provided overnight coverage in 2010 prior to new ACGME recommendations. Overall, residents were providing the overwhelming majority of the patient care overnight in pediatric training programs. While hospitalists were prevalent in pediatric training programs, in 2010 they had limited roles in direct patient care at night. The ACGME has now mandated additional residency work hour restrictions to be implemented July 2011. With these restrictions, hospitalists will likely need to expand their services, and additional hospitalists will be needed to provide overnight coverage. It is unclear where those hospitalists will come from and what their role will be. It is also unclear what the impact of increased demand and changed job description will be on the continued evolution of the field of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Future work needs to be done to establish benchmarks for inpatient coverage. The benchmarks could include guidelines on balancing patient safety with resident education. This may also involve the implementation of resident night float models. There needs to be monitoring on how changes in resident work hours and staffing affect coverage and, ultimately, how changes affect patient and resident outcomes.

APPENDIX

INPATIENT STAFFING WITHIN PEDIATRIC RESIDENCY PROGRAMS SURVEY

|

| Demographics |

| How many residents are in your residency program? (total, categorical, Med‐Peds, other combined Peds) |

| What is your average daily patient census per ward intern during daytime hours? |

| Does your hospital have a staff‐only (no residents) pediatric ward service during the daytime hours? |

| If your hospital has a staff‐only pediatric ward service, what are the proportion of patients cared for by residents vs staff‐only during daytime hours? |

| Do your residents cap the number of new patient admissions at night? |

| Providers in‐house overnight |

| How many providers do you have in‐house at night until midnight/overnight to accept patient admissions to pediatric wards? (residents, hospitalists, nurse practitioners, other) |

| Do you have attendings in‐house at night? (pediatric hospitalists, NICU, PICU, Peds EM, Peds Surgery, no attendings, other) |

| Pediatric hospitalists |

| Does your hospital have pediatric hospitalists? |

| Are your pediatric hospitalist teams staffed by: (teaching attendings and residents, hospitalist‐staff only, both) |

| If you have a staff‐only hospitalist team (no residents), how long has it been in existence? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years) |

| Are your hospitalist attendings in‐house: (daytime only, 24 hours/day, other) |

| If your hospitalist attendings are in‐house 24/7, how many years has that coverage been available? (less than 1 year, 1‐3 years, 4‐10 years, over 10 years, not available) |

| Future pediatric hospitalist coverage |

| Do you anticipate that your hospital will be adding 24/7 hospitalist attending coverage? (next year, next 2 years, next 5 years, not anticipating adding coverage, 24/7 hospitalist coverage already in place) |

| In your opinion, would further resident work hour restrictions make your hospital more likely to add additional hospitalist attendings at night? (very likely, somewhat likely, neutral, not likely) |

- ,.The Bell Commission: ethical implications for the training of physicians.Mt Sinai J Med.2000;67(2):136–139.

- ,.Restricted duty hours for surgeons and impact on residents quality of life, education, and patient care: a literature review.Patient Saf Surg.2009;3(1):3.

- Institute of Medicine. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Released December 02, 2008. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2008/Resident‐Duty‐Hours‐Enhancing‐Sleep‐Supervision‐and‐Safety.aspx. Accessed September 20,2009.

- ACGME 2010 Standards “Common Program Requirements.” Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/pdf/Common_Program_ Requirements_07012011.pdf. Accessed January 27,2011.

- Association of Pediatric Program Directors. Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) Position Statement in Response to the IOM Recommendations on Resident Duty Hours.2009. Available at: http://www.appd.org/PDFs/APPD _IOM%20 _Duty _Hours _Report _Position _Paper _4–30‐09.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- ,,,,.Lessons learned from New York state: fourteen years of experience with work hour limitations.Acad Med.2005;80(5):467–472.

- ,,,.Health care market trends and the evolution of hospitalist use and rolesJ Gen Intern Med.2005;20(2):101–107.

- ,,,,.Cost implications of reduced work hours and workloads for resident physicians.N Engl J Med.2009;360:2202–2215.

- .Revisiting duty‐hour length—IOM recommendations for patient safety and resident education.N Engl J Med.2008;359:2633–2635.

- ,,,.Resident duty hour restrictions: is less really more?J Pediatr.2009;154:631–632.

- ,.The Bell Commission: ethical implications for the training of physicians.Mt Sinai J Med.2000;67(2):136–139.

- ,.Restricted duty hours for surgeons and impact on residents quality of life, education, and patient care: a literature review.Patient Saf Surg.2009;3(1):3.

- Institute of Medicine. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Released December 02, 2008. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2008/Resident‐Duty‐Hours‐Enhancing‐Sleep‐Supervision‐and‐Safety.aspx. Accessed September 20,2009.

- ACGME 2010 Standards “Common Program Requirements.” Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/pdf/Common_Program_ Requirements_07012011.pdf. Accessed January 27,2011.

- Association of Pediatric Program Directors. Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) Position Statement in Response to the IOM Recommendations on Resident Duty Hours.2009. Available at: http://www.appd.org/PDFs/APPD _IOM%20 _Duty _Hours _Report _Position _Paper _4–30‐09.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- ,,,,.Lessons learned from New York state: fourteen years of experience with work hour limitations.Acad Med.2005;80(5):467–472.

- ,,,.Health care market trends and the evolution of hospitalist use and rolesJ Gen Intern Med.2005;20(2):101–107.

- ,,,,.Cost implications of reduced work hours and workloads for resident physicians.N Engl J Med.2009;360:2202–2215.

- .Revisiting duty‐hour length—IOM recommendations for patient safety and resident education.N Engl J Med.2008;359:2633–2635.

- ,,,.Resident duty hour restrictions: is less really more?J Pediatr.2009;154:631–632.

Copyright © 2011 Society of Hospital Medicine