User login

Waiting for Godot: The Quest to Promote Scholarship in Hospital Medicine

Twenty years into the hospitalist movement, the proven formula for developing high-quality scholarly output in a hospital medicine group remains elusive. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, McKinney et al. describe a new model in which an academic research coach—a PhD-trained researcher with 50% protected time to assist with hospitalist scholarly activities—is utilized to support scholarship.1 Built on the premise that most hospitalist faculty do not have research training and many are embarking on their first academic project, the research coach was available to engage hospitalists at any stage of scholarship from conceptualizing an idea, to submitting one’s first IRB, to data analysis, and grant and manuscript submission. This innovation (and the financial investment required) provides an opportunity to consider how to facilitate scholarship and measure its value in hospital medicine groups.

Academic institutions are built on the premise that scholarship—and research in particular—is of equal value to clinical care and teaching; a perspective that is commonly enshrined in promotion criteria that require scholarship for career advancement. While hospitalists are competent to begin clinical practice and transfer their knowledge to others at the conclusion of their residency, most are not prepared to lead research programs or create academic products from their clinical innovations, quality improvement, or medical education work. Yet, particularly for hospitalists who choose to practice in an academic setting, the leadership of their Section, Division, or Department may naturally expect scholarship to occur, similar to other clinical disciplines. In our experience as the directors of research and faculty development in our hospital medicine group, meeting this expectation requires recognizing that faculty development and scholarship development are intertwined and there must be an investment in both.

We believe that faculty development is required—but not sufficient—for the development of high-quality scholarship. In order for hospitalists to generate new knowledge in clinical, educational, quality improvement, and research domains, they must acquire a new skill set after residency training. These skills can be gained in different formats and time frames such as dedicated hospital medicine fellowships, internal faculty development programs, external programs (eg, Academic Hospitalist Academy), and/or individual mentorship. Descriptions of internal faculty development programs have unfortunately been limited to a single institutions with uncertain generalizability.2,3 One could argue that faculty development may even be more important in hospital medicine than in clinical subspecialties given the relative youth of the field and the experience level of the entry-level faculty. Pediatric hospital medicine may be farthest along in faculty development and scholarship development after becoming a distinct subspecialty recognized by the American Board of Pediatrics and American Board of Medical Specialties; pediatric hospitalists must now complete fellowship training after residency before independent practice.4 Importantly, completion of a scholarly product that advances the field is a required component of the pediatric hospital medicine fellowship curricular framework.5 Regardless of what infrastructure a hospital medicine group chooses to build, there is a growing realization that faculty development must be firmly in place in order for scholarship to flourish.

In addition to junior faculty development, there is also a need for scholarship development to translate new skills into products of scholarship. For example, a well-published senior faculty member still may need statistical assistance and a midcareer hospitalist who leads quality improvement may struggle to write an effective manuscript to disseminate their findings. McKinney et al.’s innovation seems intended to meet this need, and the just-in-time and menu-style nature of the academic research coach resource is unique and novel. One can imagine how this approach to increasing scholarship productivity could be effective and utilized by busy junior, midcareer, and senior hospitalists alike. As the authors point out, this model attempts to mitigate the drawbacks that other models for enhancing hospitalist scholarship have faced, such as relying on physician scientists as mentors, holding works-in-progress or research seminars, or funding a consulting statistician. A well-trained scientist who meets hospitalists “where they are” is appealing when placed in the context of an effective faculty development program that enables faculty to take advantage of this resource. We hope that future evaluations of this promising innovation will include a comparison group to measure the effect of the academic research coach and demonstrate a return on the financial investment supporting the academic research coach.

Measuring return on investment requires defining the value of scholarship in hospital medicine. Some things that are easy to measure and have valence for traditional academic productivity are captured in the McKinney manuscript: the number of abstracts, papers, and grants.

Measuring the value of scholarship in hospital medicine touches very near to the core of the value proposition of hospital medicine overall as a specialty. Without high-quality scholarship that demonstrates the influence of hospitalists in improving systems, leading change, educating learners, and advocating for the needs of our patients, why continue to invest in this model? We are struck every year at the Society of Hospital Medicine national conference about how much innovation hospitalists are leading – and how little is systematically evaluated or disseminated. In Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” Vladimir and Estragon talk about life and wait for Godot who, of course, never arrives. Instead of patiently waiting for more scholarship to arrive, we suggest that hospital medicine leaders follow the lead of McKinney et al. and take action by investing in it.

Disclosures

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Funding

Dr. Burke is funded by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award.

1. McKinney CM, Mookherjee S, Fihn SD, Gallagher TH. An academic research coach: an innovative approach to increasing scholarly productivity in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(8):457-461. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3194.

2. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):161-166. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.845.

3. Seymann GB, Southern W, Burger A, et al. Features of successful academic hospitalist programs: Insights from the SCHOLAR (SuCcessful HOspitaLists in academics and research) project. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(10):708-713. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2603.

4. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: a proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20161823. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

5. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al. Development of a curricular framework for pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20170698. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0698.

6. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

Twenty years into the hospitalist movement, the proven formula for developing high-quality scholarly output in a hospital medicine group remains elusive. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, McKinney et al. describe a new model in which an academic research coach—a PhD-trained researcher with 50% protected time to assist with hospitalist scholarly activities—is utilized to support scholarship.1 Built on the premise that most hospitalist faculty do not have research training and many are embarking on their first academic project, the research coach was available to engage hospitalists at any stage of scholarship from conceptualizing an idea, to submitting one’s first IRB, to data analysis, and grant and manuscript submission. This innovation (and the financial investment required) provides an opportunity to consider how to facilitate scholarship and measure its value in hospital medicine groups.

Academic institutions are built on the premise that scholarship—and research in particular—is of equal value to clinical care and teaching; a perspective that is commonly enshrined in promotion criteria that require scholarship for career advancement. While hospitalists are competent to begin clinical practice and transfer their knowledge to others at the conclusion of their residency, most are not prepared to lead research programs or create academic products from their clinical innovations, quality improvement, or medical education work. Yet, particularly for hospitalists who choose to practice in an academic setting, the leadership of their Section, Division, or Department may naturally expect scholarship to occur, similar to other clinical disciplines. In our experience as the directors of research and faculty development in our hospital medicine group, meeting this expectation requires recognizing that faculty development and scholarship development are intertwined and there must be an investment in both.

We believe that faculty development is required—but not sufficient—for the development of high-quality scholarship. In order for hospitalists to generate new knowledge in clinical, educational, quality improvement, and research domains, they must acquire a new skill set after residency training. These skills can be gained in different formats and time frames such as dedicated hospital medicine fellowships, internal faculty development programs, external programs (eg, Academic Hospitalist Academy), and/or individual mentorship. Descriptions of internal faculty development programs have unfortunately been limited to a single institutions with uncertain generalizability.2,3 One could argue that faculty development may even be more important in hospital medicine than in clinical subspecialties given the relative youth of the field and the experience level of the entry-level faculty. Pediatric hospital medicine may be farthest along in faculty development and scholarship development after becoming a distinct subspecialty recognized by the American Board of Pediatrics and American Board of Medical Specialties; pediatric hospitalists must now complete fellowship training after residency before independent practice.4 Importantly, completion of a scholarly product that advances the field is a required component of the pediatric hospital medicine fellowship curricular framework.5 Regardless of what infrastructure a hospital medicine group chooses to build, there is a growing realization that faculty development must be firmly in place in order for scholarship to flourish.

In addition to junior faculty development, there is also a need for scholarship development to translate new skills into products of scholarship. For example, a well-published senior faculty member still may need statistical assistance and a midcareer hospitalist who leads quality improvement may struggle to write an effective manuscript to disseminate their findings. McKinney et al.’s innovation seems intended to meet this need, and the just-in-time and menu-style nature of the academic research coach resource is unique and novel. One can imagine how this approach to increasing scholarship productivity could be effective and utilized by busy junior, midcareer, and senior hospitalists alike. As the authors point out, this model attempts to mitigate the drawbacks that other models for enhancing hospitalist scholarship have faced, such as relying on physician scientists as mentors, holding works-in-progress or research seminars, or funding a consulting statistician. A well-trained scientist who meets hospitalists “where they are” is appealing when placed in the context of an effective faculty development program that enables faculty to take advantage of this resource. We hope that future evaluations of this promising innovation will include a comparison group to measure the effect of the academic research coach and demonstrate a return on the financial investment supporting the academic research coach.

Measuring return on investment requires defining the value of scholarship in hospital medicine. Some things that are easy to measure and have valence for traditional academic productivity are captured in the McKinney manuscript: the number of abstracts, papers, and grants.

Measuring the value of scholarship in hospital medicine touches very near to the core of the value proposition of hospital medicine overall as a specialty. Without high-quality scholarship that demonstrates the influence of hospitalists in improving systems, leading change, educating learners, and advocating for the needs of our patients, why continue to invest in this model? We are struck every year at the Society of Hospital Medicine national conference about how much innovation hospitalists are leading – and how little is systematically evaluated or disseminated. In Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” Vladimir and Estragon talk about life and wait for Godot who, of course, never arrives. Instead of patiently waiting for more scholarship to arrive, we suggest that hospital medicine leaders follow the lead of McKinney et al. and take action by investing in it.

Disclosures

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Funding

Dr. Burke is funded by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award.

Twenty years into the hospitalist movement, the proven formula for developing high-quality scholarly output in a hospital medicine group remains elusive. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, McKinney et al. describe a new model in which an academic research coach—a PhD-trained researcher with 50% protected time to assist with hospitalist scholarly activities—is utilized to support scholarship.1 Built on the premise that most hospitalist faculty do not have research training and many are embarking on their first academic project, the research coach was available to engage hospitalists at any stage of scholarship from conceptualizing an idea, to submitting one’s first IRB, to data analysis, and grant and manuscript submission. This innovation (and the financial investment required) provides an opportunity to consider how to facilitate scholarship and measure its value in hospital medicine groups.

Academic institutions are built on the premise that scholarship—and research in particular—is of equal value to clinical care and teaching; a perspective that is commonly enshrined in promotion criteria that require scholarship for career advancement. While hospitalists are competent to begin clinical practice and transfer their knowledge to others at the conclusion of their residency, most are not prepared to lead research programs or create academic products from their clinical innovations, quality improvement, or medical education work. Yet, particularly for hospitalists who choose to practice in an academic setting, the leadership of their Section, Division, or Department may naturally expect scholarship to occur, similar to other clinical disciplines. In our experience as the directors of research and faculty development in our hospital medicine group, meeting this expectation requires recognizing that faculty development and scholarship development are intertwined and there must be an investment in both.

We believe that faculty development is required—but not sufficient—for the development of high-quality scholarship. In order for hospitalists to generate new knowledge in clinical, educational, quality improvement, and research domains, they must acquire a new skill set after residency training. These skills can be gained in different formats and time frames such as dedicated hospital medicine fellowships, internal faculty development programs, external programs (eg, Academic Hospitalist Academy), and/or individual mentorship. Descriptions of internal faculty development programs have unfortunately been limited to a single institutions with uncertain generalizability.2,3 One could argue that faculty development may even be more important in hospital medicine than in clinical subspecialties given the relative youth of the field and the experience level of the entry-level faculty. Pediatric hospital medicine may be farthest along in faculty development and scholarship development after becoming a distinct subspecialty recognized by the American Board of Pediatrics and American Board of Medical Specialties; pediatric hospitalists must now complete fellowship training after residency before independent practice.4 Importantly, completion of a scholarly product that advances the field is a required component of the pediatric hospital medicine fellowship curricular framework.5 Regardless of what infrastructure a hospital medicine group chooses to build, there is a growing realization that faculty development must be firmly in place in order for scholarship to flourish.

In addition to junior faculty development, there is also a need for scholarship development to translate new skills into products of scholarship. For example, a well-published senior faculty member still may need statistical assistance and a midcareer hospitalist who leads quality improvement may struggle to write an effective manuscript to disseminate their findings. McKinney et al.’s innovation seems intended to meet this need, and the just-in-time and menu-style nature of the academic research coach resource is unique and novel. One can imagine how this approach to increasing scholarship productivity could be effective and utilized by busy junior, midcareer, and senior hospitalists alike. As the authors point out, this model attempts to mitigate the drawbacks that other models for enhancing hospitalist scholarship have faced, such as relying on physician scientists as mentors, holding works-in-progress or research seminars, or funding a consulting statistician. A well-trained scientist who meets hospitalists “where they are” is appealing when placed in the context of an effective faculty development program that enables faculty to take advantage of this resource. We hope that future evaluations of this promising innovation will include a comparison group to measure the effect of the academic research coach and demonstrate a return on the financial investment supporting the academic research coach.

Measuring return on investment requires defining the value of scholarship in hospital medicine. Some things that are easy to measure and have valence for traditional academic productivity are captured in the McKinney manuscript: the number of abstracts, papers, and grants.

Measuring the value of scholarship in hospital medicine touches very near to the core of the value proposition of hospital medicine overall as a specialty. Without high-quality scholarship that demonstrates the influence of hospitalists in improving systems, leading change, educating learners, and advocating for the needs of our patients, why continue to invest in this model? We are struck every year at the Society of Hospital Medicine national conference about how much innovation hospitalists are leading – and how little is systematically evaluated or disseminated. In Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” Vladimir and Estragon talk about life and wait for Godot who, of course, never arrives. Instead of patiently waiting for more scholarship to arrive, we suggest that hospital medicine leaders follow the lead of McKinney et al. and take action by investing in it.

Disclosures

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Funding

Dr. Burke is funded by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award.

1. McKinney CM, Mookherjee S, Fihn SD, Gallagher TH. An academic research coach: an innovative approach to increasing scholarly productivity in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(8):457-461. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3194.

2. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):161-166. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.845.

3. Seymann GB, Southern W, Burger A, et al. Features of successful academic hospitalist programs: Insights from the SCHOLAR (SuCcessful HOspitaLists in academics and research) project. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(10):708-713. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2603.

4. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: a proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20161823. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

5. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al. Development of a curricular framework for pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20170698. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0698.

6. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

1. McKinney CM, Mookherjee S, Fihn SD, Gallagher TH. An academic research coach: an innovative approach to increasing scholarly productivity in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(8):457-461. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3194.

2. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):161-166. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.845.

3. Seymann GB, Southern W, Burger A, et al. Features of successful academic hospitalist programs: Insights from the SCHOLAR (SuCcessful HOspitaLists in academics and research) project. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(10):708-713. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2603.

4. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: a proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20161823. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

5. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al. Development of a curricular framework for pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20170698. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0698.

6. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

National Survey of Hospitalists’ Experiences with Incidental Pulmonary Nodules

Pulmonary nodules are common, and their identification is increasing as a result of the use of more sensitive chest imaging modalities.1 Pulmonary nodules are defined on imaging as small (≤30 mm), well-defined lesions, completely surrounded by pulmonary parenchyma.2 Most of the pulmonary nodules detected incidentally (ie, in asymptomatic patients outside the context of chest CT screening for lung cancer) are benign.1 Lesions >30 mm are defined as masses and have higher risks of malignancy.2

Because the majority of patients will not benefit from the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules (IPNs), improving the benefits and minimizing the harms of IPN follow-up are critical. The Fleischner Society3 published their first guideline on the management of solid IPNs in 2005,4 which was supplemented in 2013 with specific guidance for the management of subsolid IPNs.5 In 2017, both guidelines were combined in a single update.6 The Fleischner Society recommendations for imaging surveillance and tissue sampling are based on nodule type (solid vs subsolid), number (single vs multiple), size, appearance, and patient risk for malignancy.

For IPNs identified in the hospital, management may be particularly challenging. For one, the provider initially ordering the chest imaging may not be the provider coordinating the patient’s discharge, leading to a lack of knowledge that the IPN even exists. The hospitalist to primary care provider (PCP) handoff may also have vulnerabilities, including the lack of inclusion of the IPN follow-up in the discharge summary and the nonreceipt of the discharge summary by the PCP. Moreover, because a patient’s acute medical problems often take precedence during a hospitalization, inpatients may not even be made aware of identified IPNs and the need for follow-up. Thus, the absence of standardized approaches to managing IPNs is a threat to patient safety, as well as a legal liability for providers and their institutions.

To better understand the current state of IPN management in our own institution, we examined the management of IPNs identified by chest computed tomographies (CTs) performed for inpatients on our general medicine services over a two-year period.7 Among the 50 inpatients identified with IPNs requiring follow-up, 78% had no follow-up imaging documented. Moreover, 40% had no mention of the IPN in their hospital summary or discharge instructions.

To inform our approach to addressing this challenge, we sought to examine the practices of hospitalist physicians nationally regarding the management of IPNs, including hospitalists’ familiarity with the Fleischner Society guidelines.

METHODS

We developed a 14-item survey to assess hospitalists’ exposure to and management of IPNs. The survey targeted attendees of the 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) annual conference and was available for completion on a tablet at the conference registration desk, the SHM kiosk in the exhibit hall, and at the entrance and exit of the morning plenary sessions. Following the annual conference, the survey was e-mailed to conference attendees, with one follow-up e-mailed to nonresponders.

Analyses were descriptive and included proportions for categorical variables and median and mean values and standard deviations for continuous variables. In addition, we examined the association between survey items and a response of “yes” to the question “Are you familiar with the Fleischner Society guidelines for the management of incidental pulmonary nodules?”

Associations between familiarity with the Fleischner Society guidelines and survey items were examined using Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables with small sample sizes, the Cochran–Armitage test for trend for ordinal variables, and the t-test for continuous variables. The associations between categorical items were measured by odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical tests were two-sided using a P =.05 level for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using R version 3.4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with the R packages MASS, stats, and Publish. Institutional review board exemption was granted.

RESULTS

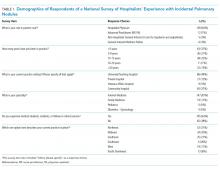

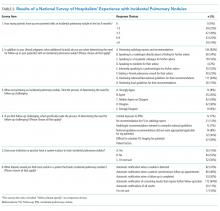

We received 174 responses from a total of 3,954 conference attendees. The majority were identified as hospitalist physicians, and most of them were internists (Table 1). About half practiced at a university or a teaching hospital, and more than half supervised trainees and practiced for more than five years. Respondents were involved in direct patient care (whether a teaching or a nonteaching service) for a median of 28 weeks annually (mean 31.2 weeks, standard deviation 13.5), and practice regions were geographically diverse. All respondents reported seeing at least one IPN case in the past six months, with most seeing three or more cases (Table 2). Despite this exposure, 42% were unfamiliar with the Fleischner Society guidelines. When determining the need for IPN follow-up, most of them utilized radiology report recommendations or consulted national or international guidelines, and a third spoke with radiologists directly. About a third agreed that determining the need for follow-up was challenging, with 39% citing patient factors (eg, lack of insurance, poor access to healthcare), and 30% citing scheduling of follow-up imaging. Few reported the availability of an automated tracking system at their institution, although most of them desired automatic notifications of results requiring follow-up.

Unadjusted analyses revealed that supervision of trainees and seeing more IPN cases significantly increased the odds of a survey respondent being familiar with the Fleischner Society guidelines (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.04-3.68, P =.05, and OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.12-2.18, P =.008, respectively; Supplementary Table 1).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the survey reported here is the first to examine hospitalists’ knowledge of the Fleischner Society guidelines and their approach to management of IPNs. Although our data suggest that hospitalists are less familiar with the Fleischner Society recommendations than pulmonologists8 and radiologists,8-10 the majority of hospitalists in our study rely on radiology report recommendations to inform follow-up. This suggests that embedding the Fleischner Society recommendations into radiology reports is an effective method to promote adherence to these recommendations, which has been demonstrated in previous research.11-13 Our study also suggests that hospitalists with more IPN exposure and those who supervise trainees are more likely to be aware of the Fleischner Society recommendations, which is similar to findings from studies examining radiologists and pulmonologists.8-9

Our findings highlight other opportunities for quality improvement in IPN management. Almost a quarter of hospitalists reported formally consulting pulmonologists for IPN management. Hospitalist groups wishing to improve value could partner with their radiology departments and embed the Fleischner Society recommendations into their imaging reports to potentially reduce unnecessary pulmonary consultations. Among the 59 hospitalists who agreed that IPN management was challenging, a majority cited the scheduling process (30%) as a barrier. Redesigning the scheduling process for follow-up imaging could be a focus in local efforts to improve IPN management. Strengthening communication between hospitalists and PCPs may provide additional opportunities for improved IPN follow-up, given the centrality of PCPs to ensuring such follow-up. This might include enhancing direct communication between hospitalists and PCPs for high-risk patients, or creating systems to ensure robust indirect communication, such as the implementation of standardized discharge summaries that uniformly include essential follow-up information.

At our institution, given the large volume of high-risk patients and imaging performed, and the available resources, we have established an IPN consult team to improve follow-up for inpatients with IPNs identified by chest CTs on Medicine services. The team includes a nurse practitioner (NP) and a pulmonologist who consult by default, to notify patients of their findings and recommended follow-up, and communicate results to their PCPs. The IPN consult team also sees patients for follow-up in the ambulatory IPN clinic. This initiative has addressed the most frequently cited challenges identified in our nationwide hospitalist survey by taking the communication and follow-up out of the hospitalists’ hands. To ensure identification of all IPNs by the NP, our radiology department has created a structured template for radiology attendings to document follow-up for all chest CTs reviewed based on the Fleischner Society guidelines. Compliance with use of the template by radiologists is followed monthly. After a run-in period, almost 100% of chest CT reports use the structured template, consistent with published findings from similar initiatives,14 and 100% of patients with new IPNs identified on the inpatient Medicine services have had an IPN consult.

The major limitation of our survey study is the response rate. It is difficult to determine in what direction this could bias our results, as those with and without experience in managing IPNs may have been equally likely to complete the survey. Despite the low response rate, our sample targeted the general cohort of conference attendees (rather than specific forums such as audiences interested in quality or imaging), and the descriptive characteristics of our convenience sample align well with the overall conference attendee demographics (eg, conference attendees were 77% hospitalist attendings and 9% advanced practice providers, as compared with 82% and 7% of survey respondents, respectively), suggesting that our respondents were representative of conference attendees as a whole.

Next steps for this work at our institution include developing systems to ensure appropriate follow-up for those with IPNs identified on chest CTs performed for Medicine outpatients. In addition, our institution is collaborating on a national study to compare outcomes resulting from following the traditional Fleischner Society recommendations compared to the new 2017 recommendations, which recommend more lenient follow-up.15

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Vivek Ahya, Eduardo Barbosa Jr., Tammy Tursi, and Anil Vachani for their leadership of the local quality improvement initiatives described in our Discussion, namely, the development and implementation of the structured templates for radiology reports and the incidental pulmonary nodule consult team.

Disclosures

Dr. Cook reports relevant financial activity outside the submitted work, including royalties from Osler Institute and grants from ACRIN and Beryl Institute. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study. There was no financial support for this study.

Previous Presentations

Presented as a poster at the 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference, Las Vegas, NV: Wilen J, Garin M, Umscheid CA, Cook TS, Myers JS. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules: a survey of hospitalists nationwide [abstract]. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2017; 12 (Suppl 2). Available at: https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/follow-up-of-incidental-pulmonary-nodules-a-survey-of-hospitalists-nationwide/. Accessed March 18, 2018.

1. Ost D, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH. Clinical Practice: the solitary pulmonary nodule. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2535-2542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp012290 PubMed

2. Tuddenham WJ. Glossary of terms for thoracic radiology: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the Fleischner Society. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143(3):509-517. PubMed

3. Janower ML. A brief history of the Fleischner Society. J Thorac Imaging. 2010;25(1):27-28. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181cc4cee. PubMed

4. Macmahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2005;237(2):395-400. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041887. PubMed

5. Naidich DP, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, et al. Recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules detected at CT: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2013;266(1):304-317. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120628. PubMed

6. MacMahon H, Naidich DP, Goo JM, et al. Guidelines for management of incidental pulmonary nodules detected on CT images: from the Fleischner Society 2017. Radiology.2017;284(1):228-243. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161659. PubMed

7. Garin M, Soran C, Cook T, Ferguson M, Day S, Myers JS. Communication and follow-up of incidental lung nodules found on chest CT in a hospitalized and ambulatory patient population. J Hosp Med. 2014:9(2). Available at: https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/communication-and-followup-of-incidental-lung-nodules-found-on-chest-ct-in-a-hospitalized-and-ambulatory-patient-population/ Accessed June 14, 2018.

8. Mets OM, de Jong PA, Chung K, Lammers JWJ, van Ginneken B, Schaefer-Prokop CM. Fleischner recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules: high awareness but limited conformance – a survey study. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:3840-3849. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4249-y. PubMed

9. Eisenberg RL, Bankier AA, Boiselle PM. Compliance with Fleischner Society Guidelines for management of small lung nodules: a survey of 834 radiologists. Radiology. 2010;255(1):218-224. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09091556. PubMed

10. Eisenberg RL. Ways to improve radiologists’ adherence to Fleischner society guidelines for management of pulmonary nodules. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10(6):439-441. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2012.10.001. PubMed

11. Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(4):378-383. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.08.003. PubMed

12. Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Dann E, Black WC. Using radiology reports to encourage evidence-based practice in the evaluation of small, incidentally detected pulmonary nodules: a preliminary study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(2):211-214. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201307-242BC. PubMed

13. McDonald JS, Koo CW, White D, Hartman TE, Bender CE, Sykes AMG. Addition of the Fleischner Society Guidelines to chest CT examination interpretive reports improves adherence to recommended follow-up care for incidental pulmonary nodules. Acad Radiol. 2017;24(3):337-344. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.08.026. PubMed

14. Zygmont ME, Shekhani H, Kerchberger JM, Johnson JO, Hanna TN. Point-of-Care reference materials increase practice compliance with societal guidelines for incidental findings in emergency imaging. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13(12):1494-1500. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.07.032. PubMed

15. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Portfolio of Funded Projects. Available at: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/pragmatic-trial-more-versus-less-intensive-strategies-active-surveillance#/. Accessed May 22, 2018.

Pulmonary nodules are common, and their identification is increasing as a result of the use of more sensitive chest imaging modalities.1 Pulmonary nodules are defined on imaging as small (≤30 mm), well-defined lesions, completely surrounded by pulmonary parenchyma.2 Most of the pulmonary nodules detected incidentally (ie, in asymptomatic patients outside the context of chest CT screening for lung cancer) are benign.1 Lesions >30 mm are defined as masses and have higher risks of malignancy.2

Because the majority of patients will not benefit from the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules (IPNs), improving the benefits and minimizing the harms of IPN follow-up are critical. The Fleischner Society3 published their first guideline on the management of solid IPNs in 2005,4 which was supplemented in 2013 with specific guidance for the management of subsolid IPNs.5 In 2017, both guidelines were combined in a single update.6 The Fleischner Society recommendations for imaging surveillance and tissue sampling are based on nodule type (solid vs subsolid), number (single vs multiple), size, appearance, and patient risk for malignancy.

For IPNs identified in the hospital, management may be particularly challenging. For one, the provider initially ordering the chest imaging may not be the provider coordinating the patient’s discharge, leading to a lack of knowledge that the IPN even exists. The hospitalist to primary care provider (PCP) handoff may also have vulnerabilities, including the lack of inclusion of the IPN follow-up in the discharge summary and the nonreceipt of the discharge summary by the PCP. Moreover, because a patient’s acute medical problems often take precedence during a hospitalization, inpatients may not even be made aware of identified IPNs and the need for follow-up. Thus, the absence of standardized approaches to managing IPNs is a threat to patient safety, as well as a legal liability for providers and their institutions.

To better understand the current state of IPN management in our own institution, we examined the management of IPNs identified by chest computed tomographies (CTs) performed for inpatients on our general medicine services over a two-year period.7 Among the 50 inpatients identified with IPNs requiring follow-up, 78% had no follow-up imaging documented. Moreover, 40% had no mention of the IPN in their hospital summary or discharge instructions.

To inform our approach to addressing this challenge, we sought to examine the practices of hospitalist physicians nationally regarding the management of IPNs, including hospitalists’ familiarity with the Fleischner Society guidelines.

METHODS

We developed a 14-item survey to assess hospitalists’ exposure to and management of IPNs. The survey targeted attendees of the 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) annual conference and was available for completion on a tablet at the conference registration desk, the SHM kiosk in the exhibit hall, and at the entrance and exit of the morning plenary sessions. Following the annual conference, the survey was e-mailed to conference attendees, with one follow-up e-mailed to nonresponders.

Analyses were descriptive and included proportions for categorical variables and median and mean values and standard deviations for continuous variables. In addition, we examined the association between survey items and a response of “yes” to the question “Are you familiar with the Fleischner Society guidelines for the management of incidental pulmonary nodules?”

Associations between familiarity with the Fleischner Society guidelines and survey items were examined using Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables with small sample sizes, the Cochran–Armitage test for trend for ordinal variables, and the t-test for continuous variables. The associations between categorical items were measured by odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical tests were two-sided using a P =.05 level for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using R version 3.4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with the R packages MASS, stats, and Publish. Institutional review board exemption was granted.

RESULTS

We received 174 responses from a total of 3,954 conference attendees. The majority were identified as hospitalist physicians, and most of them were internists (Table 1). About half practiced at a university or a teaching hospital, and more than half supervised trainees and practiced for more than five years. Respondents were involved in direct patient care (whether a teaching or a nonteaching service) for a median of 28 weeks annually (mean 31.2 weeks, standard deviation 13.5), and practice regions were geographically diverse. All respondents reported seeing at least one IPN case in the past six months, with most seeing three or more cases (Table 2). Despite this exposure, 42% were unfamiliar with the Fleischner Society guidelines. When determining the need for IPN follow-up, most of them utilized radiology report recommendations or consulted national or international guidelines, and a third spoke with radiologists directly. About a third agreed that determining the need for follow-up was challenging, with 39% citing patient factors (eg, lack of insurance, poor access to healthcare), and 30% citing scheduling of follow-up imaging. Few reported the availability of an automated tracking system at their institution, although most of them desired automatic notifications of results requiring follow-up.

Unadjusted analyses revealed that supervision of trainees and seeing more IPN cases significantly increased the odds of a survey respondent being familiar with the Fleischner Society guidelines (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.04-3.68, P =.05, and OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.12-2.18, P =.008, respectively; Supplementary Table 1).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the survey reported here is the first to examine hospitalists’ knowledge of the Fleischner Society guidelines and their approach to management of IPNs. Although our data suggest that hospitalists are less familiar with the Fleischner Society recommendations than pulmonologists8 and radiologists,8-10 the majority of hospitalists in our study rely on radiology report recommendations to inform follow-up. This suggests that embedding the Fleischner Society recommendations into radiology reports is an effective method to promote adherence to these recommendations, which has been demonstrated in previous research.11-13 Our study also suggests that hospitalists with more IPN exposure and those who supervise trainees are more likely to be aware of the Fleischner Society recommendations, which is similar to findings from studies examining radiologists and pulmonologists.8-9

Our findings highlight other opportunities for quality improvement in IPN management. Almost a quarter of hospitalists reported formally consulting pulmonologists for IPN management. Hospitalist groups wishing to improve value could partner with their radiology departments and embed the Fleischner Society recommendations into their imaging reports to potentially reduce unnecessary pulmonary consultations. Among the 59 hospitalists who agreed that IPN management was challenging, a majority cited the scheduling process (30%) as a barrier. Redesigning the scheduling process for follow-up imaging could be a focus in local efforts to improve IPN management. Strengthening communication between hospitalists and PCPs may provide additional opportunities for improved IPN follow-up, given the centrality of PCPs to ensuring such follow-up. This might include enhancing direct communication between hospitalists and PCPs for high-risk patients, or creating systems to ensure robust indirect communication, such as the implementation of standardized discharge summaries that uniformly include essential follow-up information.

At our institution, given the large volume of high-risk patients and imaging performed, and the available resources, we have established an IPN consult team to improve follow-up for inpatients with IPNs identified by chest CTs on Medicine services. The team includes a nurse practitioner (NP) and a pulmonologist who consult by default, to notify patients of their findings and recommended follow-up, and communicate results to their PCPs. The IPN consult team also sees patients for follow-up in the ambulatory IPN clinic. This initiative has addressed the most frequently cited challenges identified in our nationwide hospitalist survey by taking the communication and follow-up out of the hospitalists’ hands. To ensure identification of all IPNs by the NP, our radiology department has created a structured template for radiology attendings to document follow-up for all chest CTs reviewed based on the Fleischner Society guidelines. Compliance with use of the template by radiologists is followed monthly. After a run-in period, almost 100% of chest CT reports use the structured template, consistent with published findings from similar initiatives,14 and 100% of patients with new IPNs identified on the inpatient Medicine services have had an IPN consult.

The major limitation of our survey study is the response rate. It is difficult to determine in what direction this could bias our results, as those with and without experience in managing IPNs may have been equally likely to complete the survey. Despite the low response rate, our sample targeted the general cohort of conference attendees (rather than specific forums such as audiences interested in quality or imaging), and the descriptive characteristics of our convenience sample align well with the overall conference attendee demographics (eg, conference attendees were 77% hospitalist attendings and 9% advanced practice providers, as compared with 82% and 7% of survey respondents, respectively), suggesting that our respondents were representative of conference attendees as a whole.

Next steps for this work at our institution include developing systems to ensure appropriate follow-up for those with IPNs identified on chest CTs performed for Medicine outpatients. In addition, our institution is collaborating on a national study to compare outcomes resulting from following the traditional Fleischner Society recommendations compared to the new 2017 recommendations, which recommend more lenient follow-up.15

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Vivek Ahya, Eduardo Barbosa Jr., Tammy Tursi, and Anil Vachani for their leadership of the local quality improvement initiatives described in our Discussion, namely, the development and implementation of the structured templates for radiology reports and the incidental pulmonary nodule consult team.

Disclosures

Dr. Cook reports relevant financial activity outside the submitted work, including royalties from Osler Institute and grants from ACRIN and Beryl Institute. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study. There was no financial support for this study.

Previous Presentations

Presented as a poster at the 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference, Las Vegas, NV: Wilen J, Garin M, Umscheid CA, Cook TS, Myers JS. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules: a survey of hospitalists nationwide [abstract]. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2017; 12 (Suppl 2). Available at: https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/follow-up-of-incidental-pulmonary-nodules-a-survey-of-hospitalists-nationwide/. Accessed March 18, 2018.

Pulmonary nodules are common, and their identification is increasing as a result of the use of more sensitive chest imaging modalities.1 Pulmonary nodules are defined on imaging as small (≤30 mm), well-defined lesions, completely surrounded by pulmonary parenchyma.2 Most of the pulmonary nodules detected incidentally (ie, in asymptomatic patients outside the context of chest CT screening for lung cancer) are benign.1 Lesions >30 mm are defined as masses and have higher risks of malignancy.2

Because the majority of patients will not benefit from the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules (IPNs), improving the benefits and minimizing the harms of IPN follow-up are critical. The Fleischner Society3 published their first guideline on the management of solid IPNs in 2005,4 which was supplemented in 2013 with specific guidance for the management of subsolid IPNs.5 In 2017, both guidelines were combined in a single update.6 The Fleischner Society recommendations for imaging surveillance and tissue sampling are based on nodule type (solid vs subsolid), number (single vs multiple), size, appearance, and patient risk for malignancy.

For IPNs identified in the hospital, management may be particularly challenging. For one, the provider initially ordering the chest imaging may not be the provider coordinating the patient’s discharge, leading to a lack of knowledge that the IPN even exists. The hospitalist to primary care provider (PCP) handoff may also have vulnerabilities, including the lack of inclusion of the IPN follow-up in the discharge summary and the nonreceipt of the discharge summary by the PCP. Moreover, because a patient’s acute medical problems often take precedence during a hospitalization, inpatients may not even be made aware of identified IPNs and the need for follow-up. Thus, the absence of standardized approaches to managing IPNs is a threat to patient safety, as well as a legal liability for providers and their institutions.

To better understand the current state of IPN management in our own institution, we examined the management of IPNs identified by chest computed tomographies (CTs) performed for inpatients on our general medicine services over a two-year period.7 Among the 50 inpatients identified with IPNs requiring follow-up, 78% had no follow-up imaging documented. Moreover, 40% had no mention of the IPN in their hospital summary or discharge instructions.

To inform our approach to addressing this challenge, we sought to examine the practices of hospitalist physicians nationally regarding the management of IPNs, including hospitalists’ familiarity with the Fleischner Society guidelines.

METHODS

We developed a 14-item survey to assess hospitalists’ exposure to and management of IPNs. The survey targeted attendees of the 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) annual conference and was available for completion on a tablet at the conference registration desk, the SHM kiosk in the exhibit hall, and at the entrance and exit of the morning plenary sessions. Following the annual conference, the survey was e-mailed to conference attendees, with one follow-up e-mailed to nonresponders.

Analyses were descriptive and included proportions for categorical variables and median and mean values and standard deviations for continuous variables. In addition, we examined the association between survey items and a response of “yes” to the question “Are you familiar with the Fleischner Society guidelines for the management of incidental pulmonary nodules?”

Associations between familiarity with the Fleischner Society guidelines and survey items were examined using Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables with small sample sizes, the Cochran–Armitage test for trend for ordinal variables, and the t-test for continuous variables. The associations between categorical items were measured by odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical tests were two-sided using a P =.05 level for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using R version 3.4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with the R packages MASS, stats, and Publish. Institutional review board exemption was granted.

RESULTS

We received 174 responses from a total of 3,954 conference attendees. The majority were identified as hospitalist physicians, and most of them were internists (Table 1). About half practiced at a university or a teaching hospital, and more than half supervised trainees and practiced for more than five years. Respondents were involved in direct patient care (whether a teaching or a nonteaching service) for a median of 28 weeks annually (mean 31.2 weeks, standard deviation 13.5), and practice regions were geographically diverse. All respondents reported seeing at least one IPN case in the past six months, with most seeing three or more cases (Table 2). Despite this exposure, 42% were unfamiliar with the Fleischner Society guidelines. When determining the need for IPN follow-up, most of them utilized radiology report recommendations or consulted national or international guidelines, and a third spoke with radiologists directly. About a third agreed that determining the need for follow-up was challenging, with 39% citing patient factors (eg, lack of insurance, poor access to healthcare), and 30% citing scheduling of follow-up imaging. Few reported the availability of an automated tracking system at their institution, although most of them desired automatic notifications of results requiring follow-up.

Unadjusted analyses revealed that supervision of trainees and seeing more IPN cases significantly increased the odds of a survey respondent being familiar with the Fleischner Society guidelines (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.04-3.68, P =.05, and OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.12-2.18, P =.008, respectively; Supplementary Table 1).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the survey reported here is the first to examine hospitalists’ knowledge of the Fleischner Society guidelines and their approach to management of IPNs. Although our data suggest that hospitalists are less familiar with the Fleischner Society recommendations than pulmonologists8 and radiologists,8-10 the majority of hospitalists in our study rely on radiology report recommendations to inform follow-up. This suggests that embedding the Fleischner Society recommendations into radiology reports is an effective method to promote adherence to these recommendations, which has been demonstrated in previous research.11-13 Our study also suggests that hospitalists with more IPN exposure and those who supervise trainees are more likely to be aware of the Fleischner Society recommendations, which is similar to findings from studies examining radiologists and pulmonologists.8-9

Our findings highlight other opportunities for quality improvement in IPN management. Almost a quarter of hospitalists reported formally consulting pulmonologists for IPN management. Hospitalist groups wishing to improve value could partner with their radiology departments and embed the Fleischner Society recommendations into their imaging reports to potentially reduce unnecessary pulmonary consultations. Among the 59 hospitalists who agreed that IPN management was challenging, a majority cited the scheduling process (30%) as a barrier. Redesigning the scheduling process for follow-up imaging could be a focus in local efforts to improve IPN management. Strengthening communication between hospitalists and PCPs may provide additional opportunities for improved IPN follow-up, given the centrality of PCPs to ensuring such follow-up. This might include enhancing direct communication between hospitalists and PCPs for high-risk patients, or creating systems to ensure robust indirect communication, such as the implementation of standardized discharge summaries that uniformly include essential follow-up information.

At our institution, given the large volume of high-risk patients and imaging performed, and the available resources, we have established an IPN consult team to improve follow-up for inpatients with IPNs identified by chest CTs on Medicine services. The team includes a nurse practitioner (NP) and a pulmonologist who consult by default, to notify patients of their findings and recommended follow-up, and communicate results to their PCPs. The IPN consult team also sees patients for follow-up in the ambulatory IPN clinic. This initiative has addressed the most frequently cited challenges identified in our nationwide hospitalist survey by taking the communication and follow-up out of the hospitalists’ hands. To ensure identification of all IPNs by the NP, our radiology department has created a structured template for radiology attendings to document follow-up for all chest CTs reviewed based on the Fleischner Society guidelines. Compliance with use of the template by radiologists is followed monthly. After a run-in period, almost 100% of chest CT reports use the structured template, consistent with published findings from similar initiatives,14 and 100% of patients with new IPNs identified on the inpatient Medicine services have had an IPN consult.

The major limitation of our survey study is the response rate. It is difficult to determine in what direction this could bias our results, as those with and without experience in managing IPNs may have been equally likely to complete the survey. Despite the low response rate, our sample targeted the general cohort of conference attendees (rather than specific forums such as audiences interested in quality or imaging), and the descriptive characteristics of our convenience sample align well with the overall conference attendee demographics (eg, conference attendees were 77% hospitalist attendings and 9% advanced practice providers, as compared with 82% and 7% of survey respondents, respectively), suggesting that our respondents were representative of conference attendees as a whole.

Next steps for this work at our institution include developing systems to ensure appropriate follow-up for those with IPNs identified on chest CTs performed for Medicine outpatients. In addition, our institution is collaborating on a national study to compare outcomes resulting from following the traditional Fleischner Society recommendations compared to the new 2017 recommendations, which recommend more lenient follow-up.15

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Vivek Ahya, Eduardo Barbosa Jr., Tammy Tursi, and Anil Vachani for their leadership of the local quality improvement initiatives described in our Discussion, namely, the development and implementation of the structured templates for radiology reports and the incidental pulmonary nodule consult team.

Disclosures

Dr. Cook reports relevant financial activity outside the submitted work, including royalties from Osler Institute and grants from ACRIN and Beryl Institute. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study. There was no financial support for this study.

Previous Presentations

Presented as a poster at the 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference, Las Vegas, NV: Wilen J, Garin M, Umscheid CA, Cook TS, Myers JS. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules: a survey of hospitalists nationwide [abstract]. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2017; 12 (Suppl 2). Available at: https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/follow-up-of-incidental-pulmonary-nodules-a-survey-of-hospitalists-nationwide/. Accessed March 18, 2018.

1. Ost D, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH. Clinical Practice: the solitary pulmonary nodule. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2535-2542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp012290 PubMed

2. Tuddenham WJ. Glossary of terms for thoracic radiology: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the Fleischner Society. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143(3):509-517. PubMed

3. Janower ML. A brief history of the Fleischner Society. J Thorac Imaging. 2010;25(1):27-28. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181cc4cee. PubMed

4. Macmahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2005;237(2):395-400. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041887. PubMed

5. Naidich DP, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, et al. Recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules detected at CT: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2013;266(1):304-317. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120628. PubMed

6. MacMahon H, Naidich DP, Goo JM, et al. Guidelines for management of incidental pulmonary nodules detected on CT images: from the Fleischner Society 2017. Radiology.2017;284(1):228-243. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161659. PubMed

7. Garin M, Soran C, Cook T, Ferguson M, Day S, Myers JS. Communication and follow-up of incidental lung nodules found on chest CT in a hospitalized and ambulatory patient population. J Hosp Med. 2014:9(2). Available at: https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/communication-and-followup-of-incidental-lung-nodules-found-on-chest-ct-in-a-hospitalized-and-ambulatory-patient-population/ Accessed June 14, 2018.

8. Mets OM, de Jong PA, Chung K, Lammers JWJ, van Ginneken B, Schaefer-Prokop CM. Fleischner recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules: high awareness but limited conformance – a survey study. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:3840-3849. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4249-y. PubMed

9. Eisenberg RL, Bankier AA, Boiselle PM. Compliance with Fleischner Society Guidelines for management of small lung nodules: a survey of 834 radiologists. Radiology. 2010;255(1):218-224. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09091556. PubMed

10. Eisenberg RL. Ways to improve radiologists’ adherence to Fleischner society guidelines for management of pulmonary nodules. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10(6):439-441. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2012.10.001. PubMed

11. Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(4):378-383. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.08.003. PubMed

12. Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Dann E, Black WC. Using radiology reports to encourage evidence-based practice in the evaluation of small, incidentally detected pulmonary nodules: a preliminary study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(2):211-214. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201307-242BC. PubMed

13. McDonald JS, Koo CW, White D, Hartman TE, Bender CE, Sykes AMG. Addition of the Fleischner Society Guidelines to chest CT examination interpretive reports improves adherence to recommended follow-up care for incidental pulmonary nodules. Acad Radiol. 2017;24(3):337-344. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.08.026. PubMed

14. Zygmont ME, Shekhani H, Kerchberger JM, Johnson JO, Hanna TN. Point-of-Care reference materials increase practice compliance with societal guidelines for incidental findings in emergency imaging. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13(12):1494-1500. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.07.032. PubMed

15. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Portfolio of Funded Projects. Available at: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/pragmatic-trial-more-versus-less-intensive-strategies-active-surveillance#/. Accessed May 22, 2018.

1. Ost D, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH. Clinical Practice: the solitary pulmonary nodule. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2535-2542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp012290 PubMed

2. Tuddenham WJ. Glossary of terms for thoracic radiology: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the Fleischner Society. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143(3):509-517. PubMed

3. Janower ML. A brief history of the Fleischner Society. J Thorac Imaging. 2010;25(1):27-28. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181cc4cee. PubMed

4. Macmahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2005;237(2):395-400. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041887. PubMed

5. Naidich DP, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, et al. Recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules detected at CT: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2013;266(1):304-317. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120628. PubMed

6. MacMahon H, Naidich DP, Goo JM, et al. Guidelines for management of incidental pulmonary nodules detected on CT images: from the Fleischner Society 2017. Radiology.2017;284(1):228-243. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161659. PubMed

7. Garin M, Soran C, Cook T, Ferguson M, Day S, Myers JS. Communication and follow-up of incidental lung nodules found on chest CT in a hospitalized and ambulatory patient population. J Hosp Med. 2014:9(2). Available at: https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/communication-and-followup-of-incidental-lung-nodules-found-on-chest-ct-in-a-hospitalized-and-ambulatory-patient-population/ Accessed June 14, 2018.

8. Mets OM, de Jong PA, Chung K, Lammers JWJ, van Ginneken B, Schaefer-Prokop CM. Fleischner recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules: high awareness but limited conformance – a survey study. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:3840-3849. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4249-y. PubMed

9. Eisenberg RL, Bankier AA, Boiselle PM. Compliance with Fleischner Society Guidelines for management of small lung nodules: a survey of 834 radiologists. Radiology. 2010;255(1):218-224. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09091556. PubMed

10. Eisenberg RL. Ways to improve radiologists’ adherence to Fleischner society guidelines for management of pulmonary nodules. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10(6):439-441. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2012.10.001. PubMed

11. Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(4):378-383. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.08.003. PubMed

12. Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Dann E, Black WC. Using radiology reports to encourage evidence-based practice in the evaluation of small, incidentally detected pulmonary nodules: a preliminary study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(2):211-214. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201307-242BC. PubMed

13. McDonald JS, Koo CW, White D, Hartman TE, Bender CE, Sykes AMG. Addition of the Fleischner Society Guidelines to chest CT examination interpretive reports improves adherence to recommended follow-up care for incidental pulmonary nodules. Acad Radiol. 2017;24(3):337-344. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.08.026. PubMed

14. Zygmont ME, Shekhani H, Kerchberger JM, Johnson JO, Hanna TN. Point-of-Care reference materials increase practice compliance with societal guidelines for incidental findings in emergency imaging. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13(12):1494-1500. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.07.032. PubMed

15. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Portfolio of Funded Projects. Available at: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/pragmatic-trial-more-versus-less-intensive-strategies-active-surveillance#/. Accessed May 22, 2018.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine