User login

Determining suicide risk (Hint: A screen is not enough)

• An individualized assessment is essential to identifying relevant risk factors. C

• Use direct questions, such as, “Have you had any thoughts about killing yourself?” to screen for suicidal ideation. B

• Ask a family member or close friend to ensure that any guns or other lethal means of suicide are inaccessible to the patient at risk. C

• Avoid the use of “no harm” contracts, which are controversial and lack demonstrated effectiveness. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE When Dr. A, a 68-year-old retired gastroenterologist with a history of hypertension and hypertriglyceridemia, sees his family physician (FP) for a routine check-up, his blood pressure, at 146/88 mm Hg, is uncharacteristically high. When the physician questions him about it, the patient reports taking his hydrochlorothiazide intermittently.

Dr. A, whom the FP treated for depression 5 years ago, appears downcast. in response to queries about his current mood, the patient describes a full depressive syndrome that has progressively worsened over the past month or so. The FP decides to assess his risk of suicide. But how best to proceed?

Assessing suicide risk is an essential skill for a primary care physician. It is also a daunting task, complicated by the fact that, while mental illness often predisposes patients to suicide, large numbers of people who suffer from major depression or other mental disorders are at low risk for suicide. Yet FPs, who are often the first health care practitioners patients turn to for treatment of mental health problems1 and who frequently care for the same patients for years, are well positioned to recognize when something is seriously amiss.

The difficulty comes in knowing what the next step should be. Many researchers have attempted to develop algorithms, questionnaires, and scales to facilitate rapid screening for suicide risk. But the validity and utility of such tools are questionable. Most have a low positive predictive value and generate large numbers of false-positive results.2-4 Thus, while a standard short screen or set of questions may be included in a suicide risk assessment, these measures alone are inadequate.2,3

What’s needed is an individualized approach that focuses on evaluating patients within the context of their health status, personal strengths, unique vulnerabilities, and specific circumstances. Here’s what we recommend.

Identify patients in need

Consider an individualized suicide risk assessment for patients with any of the following:

- A presentation suggestive of a mental disorder or substance abuse5-8

- the onset of, change in, or worsening of a serious medical condition

- a recent (or anticipated) major loss or psychosocial stressor9

- an expression of hopelessness10

- an acknowledgement of suicidal ideation.

CASE Dr. A fits more than 1 of the criteria: in addition to the recurrence of his depressive symptoms, he expresses hopelessness—noting that he stopped taking his medication 2 weeks ago because ”it just doesn’t matter.”

Dig deeper to assess risk

There are 4 key components of the assessment and documentation of suicide risk: (1) An overall assessment of risk, eg, low, moderate, or high; (2) a summary of the most salient risk factors and protective factors; (3) a plan to address modifiable risk factors; and (4) a rationale for the level of care and treatment provided. A thorough evaluation is the core element of the suicide risk assessment.2,11

The depth of the evaluation depends on the apparent risk, with more effort required for those at moderate or higher risk. (For high-risk patients, severe symptoms may impede a lengthy interview, and the need for hospitalization may be obvious.)

Some of the information needed may be available from the patient’s prior history. The rest can be obtained from a current medical history, including a discussion of factors known to exacerbate—or mitigate—risk (TABLE 1). The most robust predictors of suicide include being male,12 single or living alone;13 inpatient psychiatric treatment;10,14 hopelessness;10,13 and a suicide plan or a prior suicide attempt (although most “successful” suicides are completed on the first try14,15). In addition, suicide is often precipitated by a crisis, including financial, legal, or interpersonal difficulties, housing problems, educational failure, or job loss.

Sex and age considerations. For women, the incidence of suicide is highest for those in their late 40s. For men, who have a higher risk overall, the incidence increases dramatically in adolescence and remains elevated through adulthood, with a second large increase occurring after the age of 70.12

Does the patient have a psychiatric diagnosis? Mental illness has been found to be present in more than 90% of suicides,5-7 and a psychiatric diagnosis—or psychiatric symptoms such as agitation, aggression, or severe sleep disturbance2,10,16—is a key risk factor. Substance abuse is another significant risk.8,17 The risk of suicide may be especially high after discharge from a psychiatric hospital.

Is there a lack of support? The absence of a support system is a significant risk factor; conversely, marriage and children are commonly reported protective factors. In questioning patients about family and social ties, however, keep in mind that a situation that is protective for many, or most, people—eg, marriage—may represent an added stressor and risk factor for a particular patient.18

TABLE 1

Suicide assessment: Major risks vs protective factors

| Risk factors |

|---|

| Suicidality (ideation, intent, plan) |

| Prior suicide attempts2,13 |

| Hopelessness10,13 |

| Mental illness* 5-7 |

| Recent loss or crisis9 |

| Negativity, rigidity |

| Alcohol intoxication/abuse8,17 |

| Elderly12 |

| Male12 |

| Single/living alone13 |

| Gay/bisexual orientation13,25 |

| Psychiatric symptoms†10,14 |

| Impulsivity or violent/aggressive behavior |

| Family history of suicide26 |

| Unemployment2 |

| Protective factors |

| Female |

| Marriage |

| Children‡27,28 |

| Pregnancy29 |

| Interpersonal support |

| Positive coping skills30,31 |

| Religious activity32 |

| Life satisfaction33 |

| *Especially with recent psychiatric hospitalization. |

| † Including, but not limited to, anxiety, agitation, and impulsivity. |

| ‡ This includes any patient who feels responsible for children. |

Ask about suicidal ideation

The nature of suicidality, which may be the most relevant predictor of risk, can be assessed through a number of questions (TABLE 2).15 Not surprisingly, you are most likely to elicit information if you adopt an empathic, nonjudgmental, and direct communication style.

TABLE 2

Assessing suicidality: Sample questions

|

Whenever possible, begin with open-ended questions, and use follow-up questions or other cues to encourage elaboration. Ask patients whether they have thought about self-harm. If a patient acknowledges thoughts of suicide, ask additional questions to determine whether he or she has a plan and the means to carry it out. If so, what has prevented the patient from acting on it thus far?

Patients often require time to respond to such difficult questions, so resist the urge to rush through this portion of the suicide risk assessment. Simply waiting patiently may encourage a response.

CASE When directly questioned about suicidal ideation, Dr. A acknowledges that he has had thoughts of wanting to fall asleep and not wake up. Asked whether he has considered actually hurting himself, he pauses, looks away, sighs, and utters an unconvincing denial. When his FP observes, “you paused before answering that question and then looked away,” Dr. A re-establishes eye contact and admits that he has had thoughts of taking his life.

It is not uncommon for patients with suicidal ideation to initially deny it or simply fail to respond to questions, then later to open up in response to requests for clarification or further questions. This may be partly due to the patient’s own ambivalence. It may also have to do with the way the questions are presented. In order to get an accurate answer, avoid questions leading toward a negative response. Ask: ”Have you thought about killing yourself?” not “You’re not thinking about killing yourself, are you?”

Does the patient have a plan?

Suicidal ideation is defined as passive (having thoughts of wanting to die) or active (having thoughts of actually killing oneself). It is crucial to assess the level of intent and the lethality of any plan. Too often, physicians fail to probe enough to find out whether the patient has access to a lethal means of suicide, including, but not limited to, firearms or large quantities of pills that could be used as a potentially fatal overdose.

CASE Dr. A admits that he has had suicidal thoughts for the past 2 weeks, and that these thoughts have become more frequent and intense. He also says that while drinking last weekend, he thought about shooting himself.

Although Dr. A occasionally hunts and has access to guns, he denies having any intent or plan to act on his thoughts. He adds that he would never kill himself because he doesn’t want his wife and adult children to suffer.

Follow up with family or friends

For patients like Dr. A, who appear to be at significant risk, an interview with a family member or close friend may be helpful—or even necessary—to adequately gauge the extent of the danger. Patients usually consent to a physician’s request to obtain information from a loved one, particularly if the request is presented as routine or as an action taken on the patient’s behalf. A patient’s inability to name a close contact is a red flag, as individuals who are more isolated tend to be at higher risk than people with a supportive social network.19

A refusal to grant your request to contact a loved one is also worrisome, and it may still be appropriate to contact others for collateral information or notification if the patient appears to be at considerable risk.20 In such cases, be aware of local laws, and document the rationale for gathering clinical information. Focus on obtaining information needed for risk assessment. Ethical guidelines state that when “the risk of danger is deemed to be significant,” confidential information may be revealed.21

CASE Dr. A is initially reluctant to allow you to call his wife, but consents after being told that this is a routine action and for his benefit. His wife confirms his history of depressive symptoms and recalls that he became more withdrawn than usual several months ago. She has been worried about him and is glad he is finally getting help. although she is not concerned about her husband’s safety, she agrees to remove the gun from their home— and to follow up with the FP to verify that she has done so. She accepts the FP’s explanation of this as routine and is not overly alarmed by the request.

Further questioning of Dr. A and his wife, along with the FP’s knowledge of the patient, makes it clear that he has previously demonstrated good coping skills. Dr. A cannot identify a recent stressor to explain his symptoms, but acknowledges that he has become more pessimistic about the future and intermittently feels hopeless.

Dr. A generally believes his depression will resolve, as it did in the past. he has no history of psychiatric hospitalizations or suicide attempts. Nor does he have a history of problem drinking, although he admits he has been drinking alcohol more frequently than usual in the past several weeks. He identifies his wife as his primary support, although he’s aware that he has been isolating more from her and his many other supports in the past month.

Estimate risk, decide on next steps

For experienced clinicians, a determinatiuon of whether an individual is at low, moderate, or high risk is often based on both an analytical assessment and an intuitive sense of risk. In some cases, it may be useful to distinguish between acute and chronic or baseline risk.3

Patients judged to be at the highest risk may warrant immediate transport to the emergency department.22 If a patient at this level of risk does not agree to go to the hospital, involuntary admission may be necessary, depending on the laws in your state. (For patients at moderate or moderate-to-high risk, especially if acutely elevated from baseline, hospitalization may still be offered or recommended— and the recommendation documented.)

Pay particular attention to risk factors that can be modified. Access to firearms can be restricted. Treatment of mental disorders, which can generally be considered modifiable risk factors, should be a primary focus. FPs may be able to successfully treat depression, for instance, with medication and close follow-up. Counseling or psychotherapy may also be helpful; provide a referral to an alcohol or drug treatment program, as needed.

Consider a psychiatric consultation or referral if you do not feel comfortable managing a patient who has expressed any suicidal ideation.23 Psychiatric referral should also be considered when the patient does not respond to treatment with close follow-up, when psychotic symptoms are present, when hospitalization may be warranted, or when the patient has a history of suicidal thoughts or an articulated suicide plan.

Avoid suicide prevention contracts.2,24 Asking a patient to sign a “no harm,” or suicide prevention, contract is not recommended. While such contracts may lower the anxiety of physicians, they have not been found to reduce patients’ risk and are not an adequate substitute for a suicide risk assessment.

Develop a crisis response plan. Collaboratively developed safety or crisis response plans may be written on a card. Such plans can provide steps for self-management (eg, a distracting activity) and steps for external intervention if needed, such as seeking the company of a loved one or accessing emergency services.

CASE Dr. A appears to be at moderate to high risk of suicide. Salient risk factors include his age, sex, occupation (health care providers and agriculture workers are at elevated risk12,13), depression, increased use of alcohol, and suicidal ideation. He denies any intent of acting on these thoughts, however, and has a number of protective factors, including the lack of a prior attempt, his expectation that the depression will resolve, demonstrated good coping skills, and a supportive marriage.

The patient declines an offer of hospitalization. He does, however, agree to quit drinking, and to begin a regimen of antidepressants with more frequent visits to his FP. His FP offers him a referral for psychotherapy, and he agrees to seek immediate help, should he feel unsafe.

CORRESPONDENCE Jess G. Fiedorowicz, MD, 200 Hawkins Drive W278 GH, Iowa City, IA 52242; [email protected]

1. Brody DS, Thompson TL, 2nd, Larson DB, et al. Recognizing and managing depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17:93-107.

2. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11 suppl):s1-s60.

3. Bryan CJ, Rudd MD. Advances in the assessment of suicide risk. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:185-200.

4. Gaynes BN, West SL, Ford CA, et al. Screening for suicide risk in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:822-835.

5. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R. Mental disorders and suicide in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:447-452.

6. Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Marttunen MJ, et al. Mental disorders and comorbidity in suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:935-940.

7. Rich CL, Young D, Fowler RC. San Diego suicide study. I. Young vs old subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:577-582.

8. Fiedorowicz JG, Black DW, Coryell WH. Suicide and mental morbidity. In: Shrivastava A, ed. Handbook of Suicide Behaviour. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; In Press.

9. Beautrais AL. Suicide and serious suicide attempts in youth: a multiple-group comparison study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1093-1099.

10. Conner KR, Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, et al. Psychological vulnerability to completed suicide: a review of empirical studies. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31:367-385.

11. Jacobs DG, Brewer ML. Application of The APA practice guidelines on suicide to clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:447-454.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Updated 2005. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars. Accessed December 20, 2008.

13. Coryell WH. Clinical assessment of suicide risk in depressive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:455-461.

14. Isometsa ET, Lonnqvist JK. Suicide attempts preceding completed suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:531-535.

15. Coryell W, Young EA. Clinical predictors of suicide in primary major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:412-417.

16. Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, Brent DA. Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:84-91.

17. Murphy GE, Wetzel RD, Robins E, et al. Multiple risk factors predict suicide in alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:459-463.

18. Russell Ramsay J, Newman CF. After the attempt: maintaining the therapeutic alliance following a patient’s suicide attempt. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35:413-424.

19. Beautrais AL. A case control study of suicide and attempted suicide in older adults. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32:1-9.

20. Simon RI. Assessing and Managing Suicide Risk: Guidelines for Clinically Based Risk Management. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2005:54.

21. American Psychiatric Association. The Principles of Medical Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry. Washington, DC:2009. Available at: http://www.psych.org/MainMenu/PsychiatricPractice/Ethics/ResourcesStandards/ PrinciplesofMedicalEthics.aspx. Accessed April 23, 2010.

22. Raue PJ, Brown EL, Meyers BS, et al. Does every allusion to possible suicide require the same response? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:605-612.

23. Bronheim HE, Fulop G, Kunkel EJ, et al. The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine practice guidelines for psychiatric consultation in the general medical setting. The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine. Psychosomatics. 1998;39:S8-30.

24. Simon RI. The suicide prevention contract: clinical, legal, and risk management issues. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1999;27:445-450.

25. Remafedi G, French S, Story M, et al. The relationship between suicide risk and sexual orientation: results of a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:57-60.

26. Runeson B, Asberg M. Family history of suicide among suicide victims. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1525-1526.

27. Hoyer G, Lund E. Suicide among women related to number of children in marriage. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:134-137.

28. Clark DC, Fawcett J. The relation of parenthood to suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:160.-

29. Appleby L. Suicide during pregnancy and in the first postnatal year. BMJ. 1991;302:137-140.

30. Josepho SA, Plutchik R. Stress, coping, and suicide risk in psychiatric inpatients. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1994;24:48-57.

31. Hughes SL, Neimeyer RA. Cognitive predictors of suicide risk among hospitalized psychiatric patients: a prospective study. Death Stud. 1993;17:103-124.

32. Nisbet PA, Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Seidlitz L. The effect of participation in religious activities on suicide versus natural death in adults 50 and older. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:543-546.

33. Chioqueta AP, Stiles TC. The relationship between psychological buffers, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: identification of protective factors. Crisis. 2007;28:67-73.

• An individualized assessment is essential to identifying relevant risk factors. C

• Use direct questions, such as, “Have you had any thoughts about killing yourself?” to screen for suicidal ideation. B

• Ask a family member or close friend to ensure that any guns or other lethal means of suicide are inaccessible to the patient at risk. C

• Avoid the use of “no harm” contracts, which are controversial and lack demonstrated effectiveness. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE When Dr. A, a 68-year-old retired gastroenterologist with a history of hypertension and hypertriglyceridemia, sees his family physician (FP) for a routine check-up, his blood pressure, at 146/88 mm Hg, is uncharacteristically high. When the physician questions him about it, the patient reports taking his hydrochlorothiazide intermittently.

Dr. A, whom the FP treated for depression 5 years ago, appears downcast. in response to queries about his current mood, the patient describes a full depressive syndrome that has progressively worsened over the past month or so. The FP decides to assess his risk of suicide. But how best to proceed?

Assessing suicide risk is an essential skill for a primary care physician. It is also a daunting task, complicated by the fact that, while mental illness often predisposes patients to suicide, large numbers of people who suffer from major depression or other mental disorders are at low risk for suicide. Yet FPs, who are often the first health care practitioners patients turn to for treatment of mental health problems1 and who frequently care for the same patients for years, are well positioned to recognize when something is seriously amiss.

The difficulty comes in knowing what the next step should be. Many researchers have attempted to develop algorithms, questionnaires, and scales to facilitate rapid screening for suicide risk. But the validity and utility of such tools are questionable. Most have a low positive predictive value and generate large numbers of false-positive results.2-4 Thus, while a standard short screen or set of questions may be included in a suicide risk assessment, these measures alone are inadequate.2,3

What’s needed is an individualized approach that focuses on evaluating patients within the context of their health status, personal strengths, unique vulnerabilities, and specific circumstances. Here’s what we recommend.

Identify patients in need

Consider an individualized suicide risk assessment for patients with any of the following:

- A presentation suggestive of a mental disorder or substance abuse5-8

- the onset of, change in, or worsening of a serious medical condition

- a recent (or anticipated) major loss or psychosocial stressor9

- an expression of hopelessness10

- an acknowledgement of suicidal ideation.

CASE Dr. A fits more than 1 of the criteria: in addition to the recurrence of his depressive symptoms, he expresses hopelessness—noting that he stopped taking his medication 2 weeks ago because ”it just doesn’t matter.”

Dig deeper to assess risk

There are 4 key components of the assessment and documentation of suicide risk: (1) An overall assessment of risk, eg, low, moderate, or high; (2) a summary of the most salient risk factors and protective factors; (3) a plan to address modifiable risk factors; and (4) a rationale for the level of care and treatment provided. A thorough evaluation is the core element of the suicide risk assessment.2,11

The depth of the evaluation depends on the apparent risk, with more effort required for those at moderate or higher risk. (For high-risk patients, severe symptoms may impede a lengthy interview, and the need for hospitalization may be obvious.)

Some of the information needed may be available from the patient’s prior history. The rest can be obtained from a current medical history, including a discussion of factors known to exacerbate—or mitigate—risk (TABLE 1). The most robust predictors of suicide include being male,12 single or living alone;13 inpatient psychiatric treatment;10,14 hopelessness;10,13 and a suicide plan or a prior suicide attempt (although most “successful” suicides are completed on the first try14,15). In addition, suicide is often precipitated by a crisis, including financial, legal, or interpersonal difficulties, housing problems, educational failure, or job loss.

Sex and age considerations. For women, the incidence of suicide is highest for those in their late 40s. For men, who have a higher risk overall, the incidence increases dramatically in adolescence and remains elevated through adulthood, with a second large increase occurring after the age of 70.12

Does the patient have a psychiatric diagnosis? Mental illness has been found to be present in more than 90% of suicides,5-7 and a psychiatric diagnosis—or psychiatric symptoms such as agitation, aggression, or severe sleep disturbance2,10,16—is a key risk factor. Substance abuse is another significant risk.8,17 The risk of suicide may be especially high after discharge from a psychiatric hospital.

Is there a lack of support? The absence of a support system is a significant risk factor; conversely, marriage and children are commonly reported protective factors. In questioning patients about family and social ties, however, keep in mind that a situation that is protective for many, or most, people—eg, marriage—may represent an added stressor and risk factor for a particular patient.18

TABLE 1

Suicide assessment: Major risks vs protective factors

| Risk factors |

|---|

| Suicidality (ideation, intent, plan) |

| Prior suicide attempts2,13 |

| Hopelessness10,13 |

| Mental illness* 5-7 |

| Recent loss or crisis9 |

| Negativity, rigidity |

| Alcohol intoxication/abuse8,17 |

| Elderly12 |

| Male12 |

| Single/living alone13 |

| Gay/bisexual orientation13,25 |

| Psychiatric symptoms†10,14 |

| Impulsivity or violent/aggressive behavior |

| Family history of suicide26 |

| Unemployment2 |

| Protective factors |

| Female |

| Marriage |

| Children‡27,28 |

| Pregnancy29 |

| Interpersonal support |

| Positive coping skills30,31 |

| Religious activity32 |

| Life satisfaction33 |

| *Especially with recent psychiatric hospitalization. |

| † Including, but not limited to, anxiety, agitation, and impulsivity. |

| ‡ This includes any patient who feels responsible for children. |

Ask about suicidal ideation

The nature of suicidality, which may be the most relevant predictor of risk, can be assessed through a number of questions (TABLE 2).15 Not surprisingly, you are most likely to elicit information if you adopt an empathic, nonjudgmental, and direct communication style.

TABLE 2

Assessing suicidality: Sample questions

|

Whenever possible, begin with open-ended questions, and use follow-up questions or other cues to encourage elaboration. Ask patients whether they have thought about self-harm. If a patient acknowledges thoughts of suicide, ask additional questions to determine whether he or she has a plan and the means to carry it out. If so, what has prevented the patient from acting on it thus far?

Patients often require time to respond to such difficult questions, so resist the urge to rush through this portion of the suicide risk assessment. Simply waiting patiently may encourage a response.

CASE When directly questioned about suicidal ideation, Dr. A acknowledges that he has had thoughts of wanting to fall asleep and not wake up. Asked whether he has considered actually hurting himself, he pauses, looks away, sighs, and utters an unconvincing denial. When his FP observes, “you paused before answering that question and then looked away,” Dr. A re-establishes eye contact and admits that he has had thoughts of taking his life.

It is not uncommon for patients with suicidal ideation to initially deny it or simply fail to respond to questions, then later to open up in response to requests for clarification or further questions. This may be partly due to the patient’s own ambivalence. It may also have to do with the way the questions are presented. In order to get an accurate answer, avoid questions leading toward a negative response. Ask: ”Have you thought about killing yourself?” not “You’re not thinking about killing yourself, are you?”

Does the patient have a plan?

Suicidal ideation is defined as passive (having thoughts of wanting to die) or active (having thoughts of actually killing oneself). It is crucial to assess the level of intent and the lethality of any plan. Too often, physicians fail to probe enough to find out whether the patient has access to a lethal means of suicide, including, but not limited to, firearms or large quantities of pills that could be used as a potentially fatal overdose.

CASE Dr. A admits that he has had suicidal thoughts for the past 2 weeks, and that these thoughts have become more frequent and intense. He also says that while drinking last weekend, he thought about shooting himself.

Although Dr. A occasionally hunts and has access to guns, he denies having any intent or plan to act on his thoughts. He adds that he would never kill himself because he doesn’t want his wife and adult children to suffer.

Follow up with family or friends

For patients like Dr. A, who appear to be at significant risk, an interview with a family member or close friend may be helpful—or even necessary—to adequately gauge the extent of the danger. Patients usually consent to a physician’s request to obtain information from a loved one, particularly if the request is presented as routine or as an action taken on the patient’s behalf. A patient’s inability to name a close contact is a red flag, as individuals who are more isolated tend to be at higher risk than people with a supportive social network.19

A refusal to grant your request to contact a loved one is also worrisome, and it may still be appropriate to contact others for collateral information or notification if the patient appears to be at considerable risk.20 In such cases, be aware of local laws, and document the rationale for gathering clinical information. Focus on obtaining information needed for risk assessment. Ethical guidelines state that when “the risk of danger is deemed to be significant,” confidential information may be revealed.21

CASE Dr. A is initially reluctant to allow you to call his wife, but consents after being told that this is a routine action and for his benefit. His wife confirms his history of depressive symptoms and recalls that he became more withdrawn than usual several months ago. She has been worried about him and is glad he is finally getting help. although she is not concerned about her husband’s safety, she agrees to remove the gun from their home— and to follow up with the FP to verify that she has done so. She accepts the FP’s explanation of this as routine and is not overly alarmed by the request.

Further questioning of Dr. A and his wife, along with the FP’s knowledge of the patient, makes it clear that he has previously demonstrated good coping skills. Dr. A cannot identify a recent stressor to explain his symptoms, but acknowledges that he has become more pessimistic about the future and intermittently feels hopeless.

Dr. A generally believes his depression will resolve, as it did in the past. he has no history of psychiatric hospitalizations or suicide attempts. Nor does he have a history of problem drinking, although he admits he has been drinking alcohol more frequently than usual in the past several weeks. He identifies his wife as his primary support, although he’s aware that he has been isolating more from her and his many other supports in the past month.

Estimate risk, decide on next steps

For experienced clinicians, a determinatiuon of whether an individual is at low, moderate, or high risk is often based on both an analytical assessment and an intuitive sense of risk. In some cases, it may be useful to distinguish between acute and chronic or baseline risk.3

Patients judged to be at the highest risk may warrant immediate transport to the emergency department.22 If a patient at this level of risk does not agree to go to the hospital, involuntary admission may be necessary, depending on the laws in your state. (For patients at moderate or moderate-to-high risk, especially if acutely elevated from baseline, hospitalization may still be offered or recommended— and the recommendation documented.)

Pay particular attention to risk factors that can be modified. Access to firearms can be restricted. Treatment of mental disorders, which can generally be considered modifiable risk factors, should be a primary focus. FPs may be able to successfully treat depression, for instance, with medication and close follow-up. Counseling or psychotherapy may also be helpful; provide a referral to an alcohol or drug treatment program, as needed.

Consider a psychiatric consultation or referral if you do not feel comfortable managing a patient who has expressed any suicidal ideation.23 Psychiatric referral should also be considered when the patient does not respond to treatment with close follow-up, when psychotic symptoms are present, when hospitalization may be warranted, or when the patient has a history of suicidal thoughts or an articulated suicide plan.

Avoid suicide prevention contracts.2,24 Asking a patient to sign a “no harm,” or suicide prevention, contract is not recommended. While such contracts may lower the anxiety of physicians, they have not been found to reduce patients’ risk and are not an adequate substitute for a suicide risk assessment.

Develop a crisis response plan. Collaboratively developed safety or crisis response plans may be written on a card. Such plans can provide steps for self-management (eg, a distracting activity) and steps for external intervention if needed, such as seeking the company of a loved one or accessing emergency services.

CASE Dr. A appears to be at moderate to high risk of suicide. Salient risk factors include his age, sex, occupation (health care providers and agriculture workers are at elevated risk12,13), depression, increased use of alcohol, and suicidal ideation. He denies any intent of acting on these thoughts, however, and has a number of protective factors, including the lack of a prior attempt, his expectation that the depression will resolve, demonstrated good coping skills, and a supportive marriage.

The patient declines an offer of hospitalization. He does, however, agree to quit drinking, and to begin a regimen of antidepressants with more frequent visits to his FP. His FP offers him a referral for psychotherapy, and he agrees to seek immediate help, should he feel unsafe.

CORRESPONDENCE Jess G. Fiedorowicz, MD, 200 Hawkins Drive W278 GH, Iowa City, IA 52242; [email protected]

• An individualized assessment is essential to identifying relevant risk factors. C

• Use direct questions, such as, “Have you had any thoughts about killing yourself?” to screen for suicidal ideation. B

• Ask a family member or close friend to ensure that any guns or other lethal means of suicide are inaccessible to the patient at risk. C

• Avoid the use of “no harm” contracts, which are controversial and lack demonstrated effectiveness. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE When Dr. A, a 68-year-old retired gastroenterologist with a history of hypertension and hypertriglyceridemia, sees his family physician (FP) for a routine check-up, his blood pressure, at 146/88 mm Hg, is uncharacteristically high. When the physician questions him about it, the patient reports taking his hydrochlorothiazide intermittently.

Dr. A, whom the FP treated for depression 5 years ago, appears downcast. in response to queries about his current mood, the patient describes a full depressive syndrome that has progressively worsened over the past month or so. The FP decides to assess his risk of suicide. But how best to proceed?

Assessing suicide risk is an essential skill for a primary care physician. It is also a daunting task, complicated by the fact that, while mental illness often predisposes patients to suicide, large numbers of people who suffer from major depression or other mental disorders are at low risk for suicide. Yet FPs, who are often the first health care practitioners patients turn to for treatment of mental health problems1 and who frequently care for the same patients for years, are well positioned to recognize when something is seriously amiss.

The difficulty comes in knowing what the next step should be. Many researchers have attempted to develop algorithms, questionnaires, and scales to facilitate rapid screening for suicide risk. But the validity and utility of such tools are questionable. Most have a low positive predictive value and generate large numbers of false-positive results.2-4 Thus, while a standard short screen or set of questions may be included in a suicide risk assessment, these measures alone are inadequate.2,3

What’s needed is an individualized approach that focuses on evaluating patients within the context of their health status, personal strengths, unique vulnerabilities, and specific circumstances. Here’s what we recommend.

Identify patients in need

Consider an individualized suicide risk assessment for patients with any of the following:

- A presentation suggestive of a mental disorder or substance abuse5-8

- the onset of, change in, or worsening of a serious medical condition

- a recent (or anticipated) major loss or psychosocial stressor9

- an expression of hopelessness10

- an acknowledgement of suicidal ideation.

CASE Dr. A fits more than 1 of the criteria: in addition to the recurrence of his depressive symptoms, he expresses hopelessness—noting that he stopped taking his medication 2 weeks ago because ”it just doesn’t matter.”

Dig deeper to assess risk

There are 4 key components of the assessment and documentation of suicide risk: (1) An overall assessment of risk, eg, low, moderate, or high; (2) a summary of the most salient risk factors and protective factors; (3) a plan to address modifiable risk factors; and (4) a rationale for the level of care and treatment provided. A thorough evaluation is the core element of the suicide risk assessment.2,11

The depth of the evaluation depends on the apparent risk, with more effort required for those at moderate or higher risk. (For high-risk patients, severe symptoms may impede a lengthy interview, and the need for hospitalization may be obvious.)

Some of the information needed may be available from the patient’s prior history. The rest can be obtained from a current medical history, including a discussion of factors known to exacerbate—or mitigate—risk (TABLE 1). The most robust predictors of suicide include being male,12 single or living alone;13 inpatient psychiatric treatment;10,14 hopelessness;10,13 and a suicide plan or a prior suicide attempt (although most “successful” suicides are completed on the first try14,15). In addition, suicide is often precipitated by a crisis, including financial, legal, or interpersonal difficulties, housing problems, educational failure, or job loss.

Sex and age considerations. For women, the incidence of suicide is highest for those in their late 40s. For men, who have a higher risk overall, the incidence increases dramatically in adolescence and remains elevated through adulthood, with a second large increase occurring after the age of 70.12

Does the patient have a psychiatric diagnosis? Mental illness has been found to be present in more than 90% of suicides,5-7 and a psychiatric diagnosis—or psychiatric symptoms such as agitation, aggression, or severe sleep disturbance2,10,16—is a key risk factor. Substance abuse is another significant risk.8,17 The risk of suicide may be especially high after discharge from a psychiatric hospital.

Is there a lack of support? The absence of a support system is a significant risk factor; conversely, marriage and children are commonly reported protective factors. In questioning patients about family and social ties, however, keep in mind that a situation that is protective for many, or most, people—eg, marriage—may represent an added stressor and risk factor for a particular patient.18

TABLE 1

Suicide assessment: Major risks vs protective factors

| Risk factors |

|---|

| Suicidality (ideation, intent, plan) |

| Prior suicide attempts2,13 |

| Hopelessness10,13 |

| Mental illness* 5-7 |

| Recent loss or crisis9 |

| Negativity, rigidity |

| Alcohol intoxication/abuse8,17 |

| Elderly12 |

| Male12 |

| Single/living alone13 |

| Gay/bisexual orientation13,25 |

| Psychiatric symptoms†10,14 |

| Impulsivity or violent/aggressive behavior |

| Family history of suicide26 |

| Unemployment2 |

| Protective factors |

| Female |

| Marriage |

| Children‡27,28 |

| Pregnancy29 |

| Interpersonal support |

| Positive coping skills30,31 |

| Religious activity32 |

| Life satisfaction33 |

| *Especially with recent psychiatric hospitalization. |

| † Including, but not limited to, anxiety, agitation, and impulsivity. |

| ‡ This includes any patient who feels responsible for children. |

Ask about suicidal ideation

The nature of suicidality, which may be the most relevant predictor of risk, can be assessed through a number of questions (TABLE 2).15 Not surprisingly, you are most likely to elicit information if you adopt an empathic, nonjudgmental, and direct communication style.

TABLE 2

Assessing suicidality: Sample questions

|

Whenever possible, begin with open-ended questions, and use follow-up questions or other cues to encourage elaboration. Ask patients whether they have thought about self-harm. If a patient acknowledges thoughts of suicide, ask additional questions to determine whether he or she has a plan and the means to carry it out. If so, what has prevented the patient from acting on it thus far?

Patients often require time to respond to such difficult questions, so resist the urge to rush through this portion of the suicide risk assessment. Simply waiting patiently may encourage a response.

CASE When directly questioned about suicidal ideation, Dr. A acknowledges that he has had thoughts of wanting to fall asleep and not wake up. Asked whether he has considered actually hurting himself, he pauses, looks away, sighs, and utters an unconvincing denial. When his FP observes, “you paused before answering that question and then looked away,” Dr. A re-establishes eye contact and admits that he has had thoughts of taking his life.

It is not uncommon for patients with suicidal ideation to initially deny it or simply fail to respond to questions, then later to open up in response to requests for clarification or further questions. This may be partly due to the patient’s own ambivalence. It may also have to do with the way the questions are presented. In order to get an accurate answer, avoid questions leading toward a negative response. Ask: ”Have you thought about killing yourself?” not “You’re not thinking about killing yourself, are you?”

Does the patient have a plan?

Suicidal ideation is defined as passive (having thoughts of wanting to die) or active (having thoughts of actually killing oneself). It is crucial to assess the level of intent and the lethality of any plan. Too often, physicians fail to probe enough to find out whether the patient has access to a lethal means of suicide, including, but not limited to, firearms or large quantities of pills that could be used as a potentially fatal overdose.

CASE Dr. A admits that he has had suicidal thoughts for the past 2 weeks, and that these thoughts have become more frequent and intense. He also says that while drinking last weekend, he thought about shooting himself.

Although Dr. A occasionally hunts and has access to guns, he denies having any intent or plan to act on his thoughts. He adds that he would never kill himself because he doesn’t want his wife and adult children to suffer.

Follow up with family or friends

For patients like Dr. A, who appear to be at significant risk, an interview with a family member or close friend may be helpful—or even necessary—to adequately gauge the extent of the danger. Patients usually consent to a physician’s request to obtain information from a loved one, particularly if the request is presented as routine or as an action taken on the patient’s behalf. A patient’s inability to name a close contact is a red flag, as individuals who are more isolated tend to be at higher risk than people with a supportive social network.19

A refusal to grant your request to contact a loved one is also worrisome, and it may still be appropriate to contact others for collateral information or notification if the patient appears to be at considerable risk.20 In such cases, be aware of local laws, and document the rationale for gathering clinical information. Focus on obtaining information needed for risk assessment. Ethical guidelines state that when “the risk of danger is deemed to be significant,” confidential information may be revealed.21

CASE Dr. A is initially reluctant to allow you to call his wife, but consents after being told that this is a routine action and for his benefit. His wife confirms his history of depressive symptoms and recalls that he became more withdrawn than usual several months ago. She has been worried about him and is glad he is finally getting help. although she is not concerned about her husband’s safety, she agrees to remove the gun from their home— and to follow up with the FP to verify that she has done so. She accepts the FP’s explanation of this as routine and is not overly alarmed by the request.

Further questioning of Dr. A and his wife, along with the FP’s knowledge of the patient, makes it clear that he has previously demonstrated good coping skills. Dr. A cannot identify a recent stressor to explain his symptoms, but acknowledges that he has become more pessimistic about the future and intermittently feels hopeless.

Dr. A generally believes his depression will resolve, as it did in the past. he has no history of psychiatric hospitalizations or suicide attempts. Nor does he have a history of problem drinking, although he admits he has been drinking alcohol more frequently than usual in the past several weeks. He identifies his wife as his primary support, although he’s aware that he has been isolating more from her and his many other supports in the past month.

Estimate risk, decide on next steps

For experienced clinicians, a determinatiuon of whether an individual is at low, moderate, or high risk is often based on both an analytical assessment and an intuitive sense of risk. In some cases, it may be useful to distinguish between acute and chronic or baseline risk.3

Patients judged to be at the highest risk may warrant immediate transport to the emergency department.22 If a patient at this level of risk does not agree to go to the hospital, involuntary admission may be necessary, depending on the laws in your state. (For patients at moderate or moderate-to-high risk, especially if acutely elevated from baseline, hospitalization may still be offered or recommended— and the recommendation documented.)

Pay particular attention to risk factors that can be modified. Access to firearms can be restricted. Treatment of mental disorders, which can generally be considered modifiable risk factors, should be a primary focus. FPs may be able to successfully treat depression, for instance, with medication and close follow-up. Counseling or psychotherapy may also be helpful; provide a referral to an alcohol or drug treatment program, as needed.

Consider a psychiatric consultation or referral if you do not feel comfortable managing a patient who has expressed any suicidal ideation.23 Psychiatric referral should also be considered when the patient does not respond to treatment with close follow-up, when psychotic symptoms are present, when hospitalization may be warranted, or when the patient has a history of suicidal thoughts or an articulated suicide plan.

Avoid suicide prevention contracts.2,24 Asking a patient to sign a “no harm,” or suicide prevention, contract is not recommended. While such contracts may lower the anxiety of physicians, they have not been found to reduce patients’ risk and are not an adequate substitute for a suicide risk assessment.

Develop a crisis response plan. Collaboratively developed safety or crisis response plans may be written on a card. Such plans can provide steps for self-management (eg, a distracting activity) and steps for external intervention if needed, such as seeking the company of a loved one or accessing emergency services.

CASE Dr. A appears to be at moderate to high risk of suicide. Salient risk factors include his age, sex, occupation (health care providers and agriculture workers are at elevated risk12,13), depression, increased use of alcohol, and suicidal ideation. He denies any intent of acting on these thoughts, however, and has a number of protective factors, including the lack of a prior attempt, his expectation that the depression will resolve, demonstrated good coping skills, and a supportive marriage.

The patient declines an offer of hospitalization. He does, however, agree to quit drinking, and to begin a regimen of antidepressants with more frequent visits to his FP. His FP offers him a referral for psychotherapy, and he agrees to seek immediate help, should he feel unsafe.

CORRESPONDENCE Jess G. Fiedorowicz, MD, 200 Hawkins Drive W278 GH, Iowa City, IA 52242; [email protected]

1. Brody DS, Thompson TL, 2nd, Larson DB, et al. Recognizing and managing depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17:93-107.

2. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11 suppl):s1-s60.

3. Bryan CJ, Rudd MD. Advances in the assessment of suicide risk. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:185-200.

4. Gaynes BN, West SL, Ford CA, et al. Screening for suicide risk in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:822-835.

5. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R. Mental disorders and suicide in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:447-452.

6. Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Marttunen MJ, et al. Mental disorders and comorbidity in suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:935-940.

7. Rich CL, Young D, Fowler RC. San Diego suicide study. I. Young vs old subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:577-582.

8. Fiedorowicz JG, Black DW, Coryell WH. Suicide and mental morbidity. In: Shrivastava A, ed. Handbook of Suicide Behaviour. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; In Press.

9. Beautrais AL. Suicide and serious suicide attempts in youth: a multiple-group comparison study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1093-1099.

10. Conner KR, Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, et al. Psychological vulnerability to completed suicide: a review of empirical studies. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31:367-385.

11. Jacobs DG, Brewer ML. Application of The APA practice guidelines on suicide to clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:447-454.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Updated 2005. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars. Accessed December 20, 2008.

13. Coryell WH. Clinical assessment of suicide risk in depressive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:455-461.

14. Isometsa ET, Lonnqvist JK. Suicide attempts preceding completed suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:531-535.

15. Coryell W, Young EA. Clinical predictors of suicide in primary major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:412-417.

16. Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, Brent DA. Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:84-91.

17. Murphy GE, Wetzel RD, Robins E, et al. Multiple risk factors predict suicide in alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:459-463.

18. Russell Ramsay J, Newman CF. After the attempt: maintaining the therapeutic alliance following a patient’s suicide attempt. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35:413-424.

19. Beautrais AL. A case control study of suicide and attempted suicide in older adults. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32:1-9.

20. Simon RI. Assessing and Managing Suicide Risk: Guidelines for Clinically Based Risk Management. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2005:54.

21. American Psychiatric Association. The Principles of Medical Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry. Washington, DC:2009. Available at: http://www.psych.org/MainMenu/PsychiatricPractice/Ethics/ResourcesStandards/ PrinciplesofMedicalEthics.aspx. Accessed April 23, 2010.

22. Raue PJ, Brown EL, Meyers BS, et al. Does every allusion to possible suicide require the same response? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:605-612.

23. Bronheim HE, Fulop G, Kunkel EJ, et al. The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine practice guidelines for psychiatric consultation in the general medical setting. The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine. Psychosomatics. 1998;39:S8-30.

24. Simon RI. The suicide prevention contract: clinical, legal, and risk management issues. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1999;27:445-450.

25. Remafedi G, French S, Story M, et al. The relationship between suicide risk and sexual orientation: results of a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:57-60.

26. Runeson B, Asberg M. Family history of suicide among suicide victims. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1525-1526.

27. Hoyer G, Lund E. Suicide among women related to number of children in marriage. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:134-137.

28. Clark DC, Fawcett J. The relation of parenthood to suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:160.-

29. Appleby L. Suicide during pregnancy and in the first postnatal year. BMJ. 1991;302:137-140.

30. Josepho SA, Plutchik R. Stress, coping, and suicide risk in psychiatric inpatients. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1994;24:48-57.

31. Hughes SL, Neimeyer RA. Cognitive predictors of suicide risk among hospitalized psychiatric patients: a prospective study. Death Stud. 1993;17:103-124.

32. Nisbet PA, Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Seidlitz L. The effect of participation in religious activities on suicide versus natural death in adults 50 and older. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:543-546.

33. Chioqueta AP, Stiles TC. The relationship between psychological buffers, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: identification of protective factors. Crisis. 2007;28:67-73.

1. Brody DS, Thompson TL, 2nd, Larson DB, et al. Recognizing and managing depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17:93-107.

2. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11 suppl):s1-s60.

3. Bryan CJ, Rudd MD. Advances in the assessment of suicide risk. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:185-200.

4. Gaynes BN, West SL, Ford CA, et al. Screening for suicide risk in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:822-835.

5. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R. Mental disorders and suicide in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:447-452.

6. Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Marttunen MJ, et al. Mental disorders and comorbidity in suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:935-940.

7. Rich CL, Young D, Fowler RC. San Diego suicide study. I. Young vs old subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:577-582.

8. Fiedorowicz JG, Black DW, Coryell WH. Suicide and mental morbidity. In: Shrivastava A, ed. Handbook of Suicide Behaviour. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; In Press.

9. Beautrais AL. Suicide and serious suicide attempts in youth: a multiple-group comparison study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1093-1099.

10. Conner KR, Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, et al. Psychological vulnerability to completed suicide: a review of empirical studies. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31:367-385.

11. Jacobs DG, Brewer ML. Application of The APA practice guidelines on suicide to clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:447-454.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Updated 2005. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars. Accessed December 20, 2008.

13. Coryell WH. Clinical assessment of suicide risk in depressive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:455-461.

14. Isometsa ET, Lonnqvist JK. Suicide attempts preceding completed suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:531-535.

15. Coryell W, Young EA. Clinical predictors of suicide in primary major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:412-417.

16. Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, Brent DA. Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:84-91.

17. Murphy GE, Wetzel RD, Robins E, et al. Multiple risk factors predict suicide in alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:459-463.

18. Russell Ramsay J, Newman CF. After the attempt: maintaining the therapeutic alliance following a patient’s suicide attempt. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35:413-424.

19. Beautrais AL. A case control study of suicide and attempted suicide in older adults. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32:1-9.

20. Simon RI. Assessing and Managing Suicide Risk: Guidelines for Clinically Based Risk Management. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2005:54.

21. American Psychiatric Association. The Principles of Medical Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry. Washington, DC:2009. Available at: http://www.psych.org/MainMenu/PsychiatricPractice/Ethics/ResourcesStandards/ PrinciplesofMedicalEthics.aspx. Accessed April 23, 2010.

22. Raue PJ, Brown EL, Meyers BS, et al. Does every allusion to possible suicide require the same response? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:605-612.

23. Bronheim HE, Fulop G, Kunkel EJ, et al. The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine practice guidelines for psychiatric consultation in the general medical setting. The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine. Psychosomatics. 1998;39:S8-30.

24. Simon RI. The suicide prevention contract: clinical, legal, and risk management issues. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1999;27:445-450.

25. Remafedi G, French S, Story M, et al. The relationship between suicide risk and sexual orientation: results of a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:57-60.

26. Runeson B, Asberg M. Family history of suicide among suicide victims. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1525-1526.

27. Hoyer G, Lund E. Suicide among women related to number of children in marriage. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:134-137.

28. Clark DC, Fawcett J. The relation of parenthood to suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:160.-

29. Appleby L. Suicide during pregnancy and in the first postnatal year. BMJ. 1991;302:137-140.

30. Josepho SA, Plutchik R. Stress, coping, and suicide risk in psychiatric inpatients. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1994;24:48-57.

31. Hughes SL, Neimeyer RA. Cognitive predictors of suicide risk among hospitalized psychiatric patients: a prospective study. Death Stud. 1993;17:103-124.

32. Nisbet PA, Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Seidlitz L. The effect of participation in religious activities on suicide versus natural death in adults 50 and older. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:543-546.

33. Chioqueta AP, Stiles TC. The relationship between psychological buffers, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: identification of protective factors. Crisis. 2007;28:67-73.

Borderline or bipolar? Don't skimp on the life story

Borderline, bipolar, or both? Frame your diagnosis on the patient history

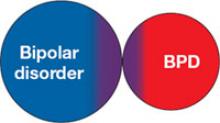

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) and bipolar disorder are frequently confused with each other, in part because of their considerable symptomatic overlap. This redundancy occurs despite the different ways these disorders are conceptualized: BPD as a personality disorder and bipolar disorder as a brain disease among Axis I clinical disorders.

BPD and bipolar disorder—especially bipolar II—often co-occur ( Box ) and are frequently misidentified, as shown by clinical and epidemiologic studies. Misdiagnosis creates problems for clinicians and patients. When diagnosed with BPD, patients with bipolar disorder may be deprived of potentially effective pharmacologic treatments.1 Conversely, the stigma that BPD carries—particularly in the mental health community—may lead clinicians to:

- not even disclose the BPD diagnosis to patients2

- lean in the direction of diagnosing BPD as bipolar disorder, potentially resulting in treatments that have little relevance or failure to refer for more appropriate psychosocial treatments.

To help you avoid confusion and the pitfalls of misdiagnosis, this article clarifies the distinctions between bipolar disorder and BPD. We discuss symptom overlap, highlight key differences between the constructs, outline diagnostic differences, and provide useful suggestions to discern the differential diagnosis.

between BPD and bipolar disorder*

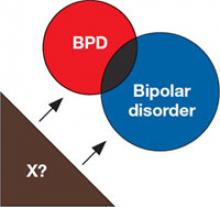

1. Inability of current nosology to separate 2 distinct conditions

Relatively indistinct diagnostic boundaries confuse the differentiation of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and bipolar disorder (5 of 9 BPD criteria may occur with mania or hypomania). In this model, the person has 1 disorder but because of symptom overlap receives a diagnosis of both. Because structured interviews do not allow for subjective judgment or expert opinion, the result is the generation of 2 diagnoses when 1 may provide a more parsimonious and valid explanation.

2. BPD exists on a spectrum with bipolar disorder

The mood lability of BPD may be viewed as not unlike that seen with bipolar disorder.1 Behaviors displayed by patients with BPD are subsequently conceptualized as arising from their unstable mood. Supporting arguments cite family study data and evidence from pharmacotherapy trials of anticonvulsants, including divalproex, for rapid cycling bipolar disorder and BPD.2 Family studies have been notable for their failure to directly characterize family members, however, and clinical trials have been quite small. Further, treatment response may have very limited nosologic implications.

3. Bipolar disorder is a risk factor for BPD

4. BPD is a risk factor for bipolar disorder

Early emergence of a bipolar disorder (in preadolescent or adolescent patients) has been proposed to disrupt psychological development, leading to BPD. This adverse impact on personality development—the “scar hypothesis”3 —is supported by data showing greater risk of co-occurring BPD with earlier onset bipolar disorder.4 More important, prospective studies of patients with bipolar disorder show a greater risk for developing BPD.5

BPD also may be a risk factor for the development of bipolar disorder—the “vulnerability hypothesis.”3 Patients with BPD are more likely to develop bipolar disorder, even compared to patients with other personality disorders.5

5. Shared risk factors

BPD and bipolar disorder may be linked by shared risk factors, such as shared genes or trait neuroticism.3

*Some evidence supports each potential explanation, and they are not necessarily mutually exclusive

References

a. Akiskal HS. Demystifying borderline personality: critique of the concept and unorthodox reflections on its natural kinship with the bipolar spectrum. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(6):401-407.

b. Mackinnon DF, Pies R. Affective instability as rapid cycling: theoretical and clinical implications for borderline personality and bipolar spectrum disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(1):1-14.

c. Christensen MV, Kessing LV. Do personality traits predict first onset in depressive and bipolar disorder? Nord J Psychiatry. 2006;60(2):79-88.

d. Goldberg JF, Garno JL. Age at onset of bipolar disorder and risk for comorbid borderline personality disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(2):205-208.

e. Gunderson JG, Weinberg I, Daversa MT, et al. Descriptive and longitudinal observations on the relationship of borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1173-1178.

Overlapping symptoms

Bipolar disorder is generally considered a clinical disorder or brain disease that can be understood as a broken mood “thermostat.” The lifetime prevalence of bipolar types I and II is approximately 2%.3 Approximately one-half of patients have a family history of illness, and multiple genes are believed to influence inheritance. Mania is the disorder’s hallmark,4 although overactivity has alternatively been proposed as a core feature.5 Most patients with mania ultimately experience depression6 ( Table 1 ).

No dimensional personality correlates have been consistently demonstrated in bipolar disorder, although co-occurring personality disorders—often the “dramatic” Cluster B type—are common4,7 and may adversely affect treatment response and suicide risk.8,9

Both bipolar disorder and BPD are associated with considerable risk of suicide or suicide attempts.10,11 Self-mutilation or self-injurious behavior without suicidal intent are particularly common in BPD.12 Threats of suicide—which may be manipulative or help-seeking—also are common in BPD and tend to be acute rather than chronic.13

Borderline personality disorder is characterized by an enduring and inflexible pattern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that impairs an individual’s psychosocial or vocational function. Its estimated prevalence is approximately 1%,14 although recent community estimates approach 6%.15 Genetic influences play a lesser etiologic role in BPD than in bipolar disorder.

Several of BPD’s common features ( Table 2 )—impulsivity, mood instability, inappropriate anger, suicidal behavior, and unstable relationships—are shared with bipolar disorder, but patients with BPD tend to show higher levels of impulsiveness and hostility than patients with bipolar disorder.16 Dimensional assessments of personality traits suggest that BPD is characterized by high neuroticism and low agreeableness.17 BPD also has been more strongly associated with a childhood history of abuse, even when compared with control groups having other personality disorders or major depression.18 The male-to-female ratio for bipolar disorder approximates 1:1;3 in BPD this ratio has been estimated at 1:4 in clinical samples19 and near 1:1 in community samples.15

BPD and bipolar disorder often co-occur. Evidence indicates ≤20% of patients with BPD have comorbid bipolar disorder20 and 15% of patients with bipolar disorder have comorbid BPD.21 Co-occurrence happens much more often than would be expected by chance. These similar bidirectional comorbidity estimates (15% to 20%) would not be expected for conditions of such differing prevalence (<1% vs 2% or more). This suggests:

- the estimated prevalence of bipolar disorder in BPD is too low

- the estimated prevalence of BPD in bipolar disorder samples is too high

- borderline personality disorder is present in >1% of the population

- bipolar disorder is less common

- some combination of the above.

Among these possibilities, the prevalence estimates of bipolar disorder are the most consistent. Several studies suggest that BPD may be much more common, with some estimates exceeding 5%.15

Table 1

Common signs and symptoms

associated with mania and depression in bipolar disorder

| (Hypo)mania | Depression |

|---|---|

| Elevated mood | Decreased mood |

| Irritability | Irritability |

| Decreased need for sleep | Anhedonia |

| Grandiosity | Decreased self-attitude |

| Talkativeness | Insomnia/hypersomnia |

| Racing thoughts | Change in appetite/weight |

| Increased motor activity | Fatigue |

| Increased sex drive | Hopelessness |

| Religiosity | Suicidal thoughts |

| Distractibility | Impaired concentration |

Table 2

Borderline personality disorder: Commonly reported features

| Impulsivity |

| Unstable relationships |

| Unstable self-image |

| Affective instability |

| Fear of abandonment |

| Recurrent self-injurious or suicidal behavior |

| Feelings of emptiness |

| Intense anger or hostility |

| Transient paranoia or dissociative symptoms |

Roots of misdiagnosis

The presence of bipolar disorder or BPD may increase the risk that the other will be misdiagnosed. When symptoms of both are present, those suggesting 1 diagnosis may reflect the consequences of the other. A diagnosis of BPD could represent a partially treated or treatment-resistant bipolar disorder, or a BPD diagnosis could be the result of several years of disruption by a mood disorder.

Characteristics of bipolar disorder have contributed to clinician bias in favor of that diagnosis rather than BPD ( Table 3 ).22,23 Bipolar disorder also may be misdiagnosed as BPD. This error may most likely occur when the history focuses excessively on cross-sectional symptoms, such as when a patient with bipolar disorder shows prominent mood lability or interpersonal sensitivity during a mood episode but not when euthymic.

Bipolar II disorder. The confusion between bipolar disorder and BPD may be particularly problematic for patients with bipolar II disorder or subthreshold bipolar disorders. The manias of bipolar I disorder are much more readily distinguishable from the mood instability or reactivity of BPD. The manic symptoms of bipolar I are more florid, more pronounced, and lead to more obvious impairment.

The milder highs of bipolar II may resemble the mood fluctuations seen in BPD. Further, bipolar II is characterized by a greater chronicity and affective morbidity than bipolar I, and episodes of illness may be characterized by irritability, anger, and racing thoughts.24 Whereas impulsivity or aggression are more characteristic of BPD, bipolar II is similar to BPD on dimensions of affective instability.24,25

When present in BPD, affective instability or lability is conceptualized as ultra-rapid or ultradian, with a frequency of hours to days. BPD is less likely than bipolar II to show affective lability between depression and euthymia or elation and more likely to show fluctuations into anger and anxiety.26

Nonetheless, because of the increased prominence of shared features and reduced distinguishing features, bipolar II and BPD are prone to misdiagnosis and commonly co-occur.

Table 3

Clinician biases that may favor a bipolar disorder diagnosis, rather than BPD

| Bipolar disorder is supported by decades of research |

| Patients with bipolar disorder are often considered more “likeable” than those with BPD |

| Bipolar disorder is more treatable and has a better long-term outcome than BPD (although BPD is generally characterized by clinical improvement, whereas bipolar disorder is more stable with perhaps some increase in depressive symptom burden) |

| Widely thought to have a biologic basis, the bipolar diagnosis conveys less stigma than BPD, which often is less empathically attributed to the patient’s own failings |

| A bipolar diagnosis is easier to explain to patients than BPD; many psychiatrists have difficulty explaining personality disorders in terms patients understand |

| BPD: borderline personality disorder |

| Source: References 22,23 |

History, the diagnostic key

A thorough and rigorous psychiatric history is essential to distinguish BPD from bipolar disorder. Supplementing the patient’s history with an informant interview is often helpful.

Because personality disorders are considered a chronic and enduring pattern of maladaptive behavior, focus the history on longitudinal course and not simply cross-sectional symptoms. Thus, symptoms suggestive of BPD that are confined only to clearly defined episodes of mood disturbance and are absent during euthymia would not warrant a BPD diagnosis.

Temporal relationship. A detailed chronologic history can help determine the temporal relationship between any borderline features and mood episodes. When the patient’s life story is used as a scaffold for the phenomenologic portions of the psychiatric history, one can determine whether any such functional impairment is confined to episodes of mood disorder or appears as an enduring pattern of thinking, acting, and relating. Exploring what happened at notable life transitions—leaving school, loss of job, divorce/separation—may be similarly helpful.

Family history of psychiatric illness may provide a clue to an individual’s genetic predisposition but, of course, does not determine diagnosis. A detailed family and social history that provides evidence of an individual’s function in school, work, and interpersonal relationships is more relevant.

Abandonment and identity issues. Essential to BPD is fear of abandonment, often an undue fear that those important to patients will leave them. Patients may go to extremes to avoid being “abandoned,” even when this threat is not genuine.27,28 Their insecure attachments often lead them to fear being alone. The patient with BPD may:

- make frantic phone calls or send text messages to a friend or lover seeking reassurance

- take extreme measures such as refusing to leave the person’s home or pleading with them not to leave.

Patients with BPD often struggle with identity disturbance, leading them to wonder who they are and what their beliefs and core values are.29 Although occasionally patients with bipolar disorder may have these symptoms, they are not characteristic of bipolar disorder.

Mood lability. The time course of changes in affect or mood swings also may help distinguish BPD from bipolar disorder.

- With bipolar disorder the shift typically is from depression to elation or the reverse, and moods are sustained. Manias or hypomanias are often immediately followed by a “crash” into depression.

- With BPD, “roller-coaster moods” are typical, mood shifts are nonsustained, and the poles often are anxiety, anger, or desperation.

Patients with BPD often report moods shifting rapidly over minutes or hours, but they rarely describe moods sustained for days or weeks on end—other than perhaps depression. Mood lability of BPD often is produced by interpersonal sensitivity, whereas mood lability in bipolar disorder tends to be autonomous and persistent.

Young patients. Assessment can be particularly challenging in young adults and adolescents because symptoms of an emerging bipolar disorder can be more difficult to distinguish from BPD.30 Patients this young also may have less longitudinal history to distinguish an enduring pattern of thinking and relating from a mood disorder. For these cases, it may be particularly important to classify the frequency and pattern of mood symptoms.

Affective dysregulation is a core feature of BPD and is variably defined as a mood reactivity, typically of short duration (often hours). Cycling in bipolar disorder classically involves a periodicity of weeks to months. Even the broadest definitions include a minimum duration of 2 days for hypomania.5

Mood reactivity can occur within episodes of bipolar disorder, although episodes may occur spontaneously and without an obvious precipitant or stressor. Impulsivity may represent more of an essential feature of BPD than affective instability or mood reactivity and may be of particular diagnostic relevance.

Treatment implications

When you are unable to make a clear diagnosis, describe your clinical reasoning and differential diagnosis in the assessment or formulation. With close follow-up, the longitudinal history and course of illness may eventually lead you to an accurate diagnosis.

There are good reasons to acknowledge both conditions when bipolar disorder and BPD are present. Proper recognition of bipolar disorder is a prerequisite to taking full advantage of proven pharmacologic treatments. The evidence base for pharmacologic management of BPD remains limited,31 but recognizing this disorder may help the patient understand his or her psychiatric history and encourage the use of effective psychosocial treatments.

Psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder may target demoralization and circadian rhythms with sleep hygiene or social rhythms therapy. Acknowledging BPD:

- helps both clinician and patient to better understand the condition

- facilitates setting realistic treatment goals because BPD tends to respond to medication less robustly than bipolar disorder.

Recognizing BPD also allows for referral to targeted psychosocial treatments, including dialectical behavior therapy, mentalization-based treatment, or Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS).32-34

Related resources

- National Institute of Mental Health. Overview on borderline personality disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/borderline-personality-disorder-fact-sheet/index.shtml.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/bipolar-disorder/index.shtml.

- Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS). www.uihealthcare.com/topics/medicaldepartments/psychiatry/stepps/index.html.

Drug brand name

- Divalproex • Depakote, Depakene, others

Disclosures