User login

An Unusual Cause of Shortness of Breath: Primary Tracheal Basal Cell Adenocarcinoma

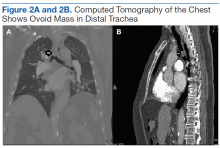

Salivary gland lung tumors are extremely rare intrathoracic malignancies, accounting for only 0.2% of all lung tumors.1 It has been postulated that these lung tumors arise from pluripotential cells in the epithelium of the submucosal bronchial glands and usually present as endoluminal lesions. The cause of salivary gland tumors is unclear. They seem to be unrelated to exposure to smoking, air pollutants, or other chemicals.2 Associated symptoms are generally related to endoluminal obstruction by the tumors, which are centrally located. Thus, presenting symptoms commonly include chronic cough, progressive dyspnea, hoarseness, wheezing, and occasional hemoptysis.3 Chest radiographs seem normal in most cases except those in which obstruction is present. Computed tomography usually shows well-defined endotracheal or endobronchial lesions that are lobulated, polypoid, or smooth, without infiltration into surrounding tissues.

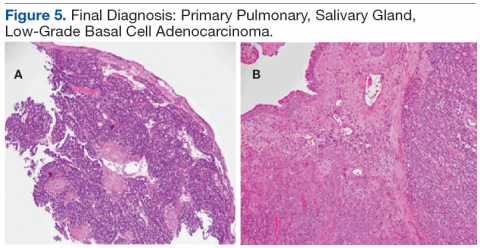

Although basal cell adenocarcinoma (BCAC) was included in World Health Organization’s (WHO) Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours in 1991, its definition—“an epithelial neoplasm that has cytological characteristics of basal cell adenoma (BCA), but a morphologic growth pattern indicative of malignancy”—did not appear until 2005.4 Basal cell adenocarcinoma generally is classified as a low-grade malignancy with a good long-term prognosis. It usually affects parotid and submandibular minor salivary glands.5

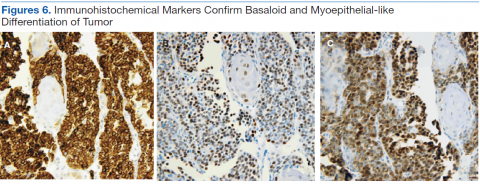

Histologic differentiation of BCAC and BCA is difficult and depends on whether local structures have been invaded or on which histologic features of perineural or vascular invasion are present.6 Basal cell adenocarcinoma also shows strong immunoreactivity to cytokeratin 7 (CK-7) and variable myoepithelial staining with S100.7 Because of the prognosis and potential treatment differences involved, BCAC must be differentiated from other basaloid cell tumors, such as BCA, adenoid cystic carcinoma, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, myoepithelial tumor, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).8 Surgical excision is the primary treatment of choice.5 Rare in the salivary glands, BCA and BCAC are even rarer in salivary gland tissue outside the head and neck region. The authors report on a case of BCAC of the salivary gland tissue in the trachea.

Case Report

An 84-year-old man with diabetes mellitus and hypertension and a nonsmoker presented to the emergency department of the VA Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan, Puerto Rico, with a dry cough and shortness of breath lasting 1 week, which worsened the day before

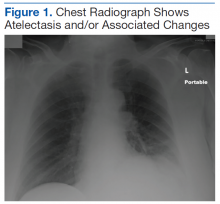

presentation. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and in no respiratory distress, and his vital signs were within normal limits. There was no barrel chest, no prolonged expiratory phase, and occasional wheezing more prominent on the left side. A chest radiograph showed atelectasis and/or associated changes (Figure 1).

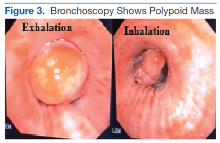

After the initial biopsy results led to a provisional diagnosis of basaloid neoplasm with squamous features, the patient underwent rigid bronchoscopic tracheal tumor debridement followed by cryotherapy at the base of the tumor.

Discussion

Primary tracheal tumors are rare, accounting for < 1% of all malignancies.9,10 According to the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, the rate of new cases of primary carcinoma of the trachea was 2.6 per 1 million people per year.11 Of all primary tumors of the trachea, 80% are malignant9,10; the rest vary widely and include both malignant and benign histotypes.11

The abundant minor salivary gland tissue in the upper respiratory tract can potentially develop neoplasia the same as the wide spectrum seen in head and neck salivary gland tumors. The most recent (2004) WHO Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart includes a brief section on salivary gland tumors and mentions only mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, myoepithelial carcinoma, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, pleomorphic adenoma, and carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma.12 However, there are reports of other salivary gland tumors in the tracheopulmonary location.

García and colleagues recently described a case of hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma with its defining EWSR1-ATF1 (Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1–activating transcription factor 1) fusion transcript.13 Similarly, no tracheopulmonary BCAC cases have been reported in the English-language literature since 2004, when Damiani and colleagues described a case of basal adenocarcinoma of the lung.14 In 2012, Yamada and colleagues reported a case of “basaloid carcinoma with central cavitation,”15 which showed a peculiar immunohistochemical profile similar

to the tumor described in the present article—suggestive of a myoepithelial origin if the morphologic architectural features match.

Salivary gland tumors are prone to manifest the squamous phenotype. Depending on the biopsy modality, these squamous areas (squamous eddies) can be sampled and can lead to the erroneous diagnosis of SCC. However, the histologic features of squamous malignancy are

lacking in these squamous components, and the pathologist should be able to distinguish additional phenotypes that can generate a wider differential diagnosis.

On follow-up, this patient has maintained satisfactory respiratory function. Starting 2 years after the initial resection, he has had annual checkups. Recent imaging and bronchoscopy have revealed tumor recurrence in the same site. Because of the patient’s extensive comorbidities, surgical intervention has been deferred in favor of cryotherapy, a less aggressive therapy.

Author disclosure

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Moran CA. Primary salivary gland-type tumors of the lung. Semin Diagn Pathol.

1995;12(2):106-122.

2. Molina JR, Aubry MC, Lewis JE, et al. Primary salivary gland-type lung cancer: spectrum of clinical presentation, histopathologic and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2007;110(10):2253-2259.

3. Brutinel WM, Cortese DA, McDougall JC, Gillio RG, Bergstralh EJ. A two-year experience with the neodymium-YAG laser in endobronchial obstruction. Chest. 1987;91(2):159-165.

4. Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2005. International Agency for Research on Cancer website. https://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/pat-gen/bb9/BB9.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

5. Sarath PV, Kannan N, Patil R, Manne RK, Swapna B, Suneel Kumar KV. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of the minor salivary glands involving palate and maxillary sinus. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2013;3(suppl 1):4.

6. Farrell T, Chang YL. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(10):1602-1604.

7. Jung MJ, Roh JL, Choi SH, et al. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of the salivary gland: a morphological and immunohistochemical comparison with basal cell adenoma with and without capsular invasion. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:171.

8. Jäkel KT, Löning T. Differential diagnosis of basaloid salivary gland tumors [in German]. Pathologe. 2004;25(1):46-55.

9. Urdaneta AI, Yu JB, Wilson LD. Population based cancer registry analysis of primary tracheal carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2011;34(1):32-37.

10. Varadhachary GR, Rabe MN. Cancer of unknown primary site. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(8):757-765.

11. Pelosi G, Fraggetta F, Maffini F, Solli P, Cavallon A, Viale G. Pulmonary epithelialmyoepithelial tumor of unproven malignant potential: report of a case and review

of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2001;14(5):521-526.

12. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004. International Agency for Research on Cancer website. https://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online /pat-gen/bb10/BB10.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2016.

13. García JJ, Jin L, Jackson SB, et al. Primary pulmonary hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma of bronchial submucosal gland origin. Hum Pathol. 2015;46(3):471-475.

14. Damiani S, Magrini E, Farnedi A, Pession A. Basal cell (myoepithelial) adenocarcinoma of the lung. First case with cytogenetic findings. Histopathology. 2004;45(4):422-424.

15. Yamada S, Noguchi H, Nabeshima A, et al. Basaloid carcinoma of the lung associated with central cavitation: a unique surgical case focusing on cytological and immunohistochemical findings. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:175-180.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

Salivary gland lung tumors are extremely rare intrathoracic malignancies, accounting for only 0.2% of all lung tumors.1 It has been postulated that these lung tumors arise from pluripotential cells in the epithelium of the submucosal bronchial glands and usually present as endoluminal lesions. The cause of salivary gland tumors is unclear. They seem to be unrelated to exposure to smoking, air pollutants, or other chemicals.2 Associated symptoms are generally related to endoluminal obstruction by the tumors, which are centrally located. Thus, presenting symptoms commonly include chronic cough, progressive dyspnea, hoarseness, wheezing, and occasional hemoptysis.3 Chest radiographs seem normal in most cases except those in which obstruction is present. Computed tomography usually shows well-defined endotracheal or endobronchial lesions that are lobulated, polypoid, or smooth, without infiltration into surrounding tissues.

Although basal cell adenocarcinoma (BCAC) was included in World Health Organization’s (WHO) Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours in 1991, its definition—“an epithelial neoplasm that has cytological characteristics of basal cell adenoma (BCA), but a morphologic growth pattern indicative of malignancy”—did not appear until 2005.4 Basal cell adenocarcinoma generally is classified as a low-grade malignancy with a good long-term prognosis. It usually affects parotid and submandibular minor salivary glands.5

Histologic differentiation of BCAC and BCA is difficult and depends on whether local structures have been invaded or on which histologic features of perineural or vascular invasion are present.6 Basal cell adenocarcinoma also shows strong immunoreactivity to cytokeratin 7 (CK-7) and variable myoepithelial staining with S100.7 Because of the prognosis and potential treatment differences involved, BCAC must be differentiated from other basaloid cell tumors, such as BCA, adenoid cystic carcinoma, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, myoepithelial tumor, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).8 Surgical excision is the primary treatment of choice.5 Rare in the salivary glands, BCA and BCAC are even rarer in salivary gland tissue outside the head and neck region. The authors report on a case of BCAC of the salivary gland tissue in the trachea.

Case Report

An 84-year-old man with diabetes mellitus and hypertension and a nonsmoker presented to the emergency department of the VA Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan, Puerto Rico, with a dry cough and shortness of breath lasting 1 week, which worsened the day before

presentation. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and in no respiratory distress, and his vital signs were within normal limits. There was no barrel chest, no prolonged expiratory phase, and occasional wheezing more prominent on the left side. A chest radiograph showed atelectasis and/or associated changes (Figure 1).

After the initial biopsy results led to a provisional diagnosis of basaloid neoplasm with squamous features, the patient underwent rigid bronchoscopic tracheal tumor debridement followed by cryotherapy at the base of the tumor.

Discussion

Primary tracheal tumors are rare, accounting for < 1% of all malignancies.9,10 According to the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, the rate of new cases of primary carcinoma of the trachea was 2.6 per 1 million people per year.11 Of all primary tumors of the trachea, 80% are malignant9,10; the rest vary widely and include both malignant and benign histotypes.11

The abundant minor salivary gland tissue in the upper respiratory tract can potentially develop neoplasia the same as the wide spectrum seen in head and neck salivary gland tumors. The most recent (2004) WHO Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart includes a brief section on salivary gland tumors and mentions only mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, myoepithelial carcinoma, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, pleomorphic adenoma, and carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma.12 However, there are reports of other salivary gland tumors in the tracheopulmonary location.

García and colleagues recently described a case of hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma with its defining EWSR1-ATF1 (Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1–activating transcription factor 1) fusion transcript.13 Similarly, no tracheopulmonary BCAC cases have been reported in the English-language literature since 2004, when Damiani and colleagues described a case of basal adenocarcinoma of the lung.14 In 2012, Yamada and colleagues reported a case of “basaloid carcinoma with central cavitation,”15 which showed a peculiar immunohistochemical profile similar

to the tumor described in the present article—suggestive of a myoepithelial origin if the morphologic architectural features match.

Salivary gland tumors are prone to manifest the squamous phenotype. Depending on the biopsy modality, these squamous areas (squamous eddies) can be sampled and can lead to the erroneous diagnosis of SCC. However, the histologic features of squamous malignancy are

lacking in these squamous components, and the pathologist should be able to distinguish additional phenotypes that can generate a wider differential diagnosis.

On follow-up, this patient has maintained satisfactory respiratory function. Starting 2 years after the initial resection, he has had annual checkups. Recent imaging and bronchoscopy have revealed tumor recurrence in the same site. Because of the patient’s extensive comorbidities, surgical intervention has been deferred in favor of cryotherapy, a less aggressive therapy.

Author disclosure

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Salivary gland lung tumors are extremely rare intrathoracic malignancies, accounting for only 0.2% of all lung tumors.1 It has been postulated that these lung tumors arise from pluripotential cells in the epithelium of the submucosal bronchial glands and usually present as endoluminal lesions. The cause of salivary gland tumors is unclear. They seem to be unrelated to exposure to smoking, air pollutants, or other chemicals.2 Associated symptoms are generally related to endoluminal obstruction by the tumors, which are centrally located. Thus, presenting symptoms commonly include chronic cough, progressive dyspnea, hoarseness, wheezing, and occasional hemoptysis.3 Chest radiographs seem normal in most cases except those in which obstruction is present. Computed tomography usually shows well-defined endotracheal or endobronchial lesions that are lobulated, polypoid, or smooth, without infiltration into surrounding tissues.

Although basal cell adenocarcinoma (BCAC) was included in World Health Organization’s (WHO) Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours in 1991, its definition—“an epithelial neoplasm that has cytological characteristics of basal cell adenoma (BCA), but a morphologic growth pattern indicative of malignancy”—did not appear until 2005.4 Basal cell adenocarcinoma generally is classified as a low-grade malignancy with a good long-term prognosis. It usually affects parotid and submandibular minor salivary glands.5

Histologic differentiation of BCAC and BCA is difficult and depends on whether local structures have been invaded or on which histologic features of perineural or vascular invasion are present.6 Basal cell adenocarcinoma also shows strong immunoreactivity to cytokeratin 7 (CK-7) and variable myoepithelial staining with S100.7 Because of the prognosis and potential treatment differences involved, BCAC must be differentiated from other basaloid cell tumors, such as BCA, adenoid cystic carcinoma, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, myoepithelial tumor, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).8 Surgical excision is the primary treatment of choice.5 Rare in the salivary glands, BCA and BCAC are even rarer in salivary gland tissue outside the head and neck region. The authors report on a case of BCAC of the salivary gland tissue in the trachea.

Case Report

An 84-year-old man with diabetes mellitus and hypertension and a nonsmoker presented to the emergency department of the VA Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan, Puerto Rico, with a dry cough and shortness of breath lasting 1 week, which worsened the day before

presentation. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and in no respiratory distress, and his vital signs were within normal limits. There was no barrel chest, no prolonged expiratory phase, and occasional wheezing more prominent on the left side. A chest radiograph showed atelectasis and/or associated changes (Figure 1).

After the initial biopsy results led to a provisional diagnosis of basaloid neoplasm with squamous features, the patient underwent rigid bronchoscopic tracheal tumor debridement followed by cryotherapy at the base of the tumor.

Discussion

Primary tracheal tumors are rare, accounting for < 1% of all malignancies.9,10 According to the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, the rate of new cases of primary carcinoma of the trachea was 2.6 per 1 million people per year.11 Of all primary tumors of the trachea, 80% are malignant9,10; the rest vary widely and include both malignant and benign histotypes.11

The abundant minor salivary gland tissue in the upper respiratory tract can potentially develop neoplasia the same as the wide spectrum seen in head and neck salivary gland tumors. The most recent (2004) WHO Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart includes a brief section on salivary gland tumors and mentions only mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, myoepithelial carcinoma, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, pleomorphic adenoma, and carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma.12 However, there are reports of other salivary gland tumors in the tracheopulmonary location.

García and colleagues recently described a case of hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma with its defining EWSR1-ATF1 (Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1–activating transcription factor 1) fusion transcript.13 Similarly, no tracheopulmonary BCAC cases have been reported in the English-language literature since 2004, when Damiani and colleagues described a case of basal adenocarcinoma of the lung.14 In 2012, Yamada and colleagues reported a case of “basaloid carcinoma with central cavitation,”15 which showed a peculiar immunohistochemical profile similar

to the tumor described in the present article—suggestive of a myoepithelial origin if the morphologic architectural features match.

Salivary gland tumors are prone to manifest the squamous phenotype. Depending on the biopsy modality, these squamous areas (squamous eddies) can be sampled and can lead to the erroneous diagnosis of SCC. However, the histologic features of squamous malignancy are

lacking in these squamous components, and the pathologist should be able to distinguish additional phenotypes that can generate a wider differential diagnosis.

On follow-up, this patient has maintained satisfactory respiratory function. Starting 2 years after the initial resection, he has had annual checkups. Recent imaging and bronchoscopy have revealed tumor recurrence in the same site. Because of the patient’s extensive comorbidities, surgical intervention has been deferred in favor of cryotherapy, a less aggressive therapy.

Author disclosure

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Moran CA. Primary salivary gland-type tumors of the lung. Semin Diagn Pathol.

1995;12(2):106-122.

2. Molina JR, Aubry MC, Lewis JE, et al. Primary salivary gland-type lung cancer: spectrum of clinical presentation, histopathologic and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2007;110(10):2253-2259.

3. Brutinel WM, Cortese DA, McDougall JC, Gillio RG, Bergstralh EJ. A two-year experience with the neodymium-YAG laser in endobronchial obstruction. Chest. 1987;91(2):159-165.

4. Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2005. International Agency for Research on Cancer website. https://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/pat-gen/bb9/BB9.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

5. Sarath PV, Kannan N, Patil R, Manne RK, Swapna B, Suneel Kumar KV. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of the minor salivary glands involving palate and maxillary sinus. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2013;3(suppl 1):4.

6. Farrell T, Chang YL. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(10):1602-1604.

7. Jung MJ, Roh JL, Choi SH, et al. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of the salivary gland: a morphological and immunohistochemical comparison with basal cell adenoma with and without capsular invasion. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:171.

8. Jäkel KT, Löning T. Differential diagnosis of basaloid salivary gland tumors [in German]. Pathologe. 2004;25(1):46-55.

9. Urdaneta AI, Yu JB, Wilson LD. Population based cancer registry analysis of primary tracheal carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2011;34(1):32-37.

10. Varadhachary GR, Rabe MN. Cancer of unknown primary site. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(8):757-765.

11. Pelosi G, Fraggetta F, Maffini F, Solli P, Cavallon A, Viale G. Pulmonary epithelialmyoepithelial tumor of unproven malignant potential: report of a case and review

of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2001;14(5):521-526.

12. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004. International Agency for Research on Cancer website. https://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online /pat-gen/bb10/BB10.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2016.

13. García JJ, Jin L, Jackson SB, et al. Primary pulmonary hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma of bronchial submucosal gland origin. Hum Pathol. 2015;46(3):471-475.

14. Damiani S, Magrini E, Farnedi A, Pession A. Basal cell (myoepithelial) adenocarcinoma of the lung. First case with cytogenetic findings. Histopathology. 2004;45(4):422-424.

15. Yamada S, Noguchi H, Nabeshima A, et al. Basaloid carcinoma of the lung associated with central cavitation: a unique surgical case focusing on cytological and immunohistochemical findings. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:175-180.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

1. Moran CA. Primary salivary gland-type tumors of the lung. Semin Diagn Pathol.

1995;12(2):106-122.

2. Molina JR, Aubry MC, Lewis JE, et al. Primary salivary gland-type lung cancer: spectrum of clinical presentation, histopathologic and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2007;110(10):2253-2259.

3. Brutinel WM, Cortese DA, McDougall JC, Gillio RG, Bergstralh EJ. A two-year experience with the neodymium-YAG laser in endobronchial obstruction. Chest. 1987;91(2):159-165.

4. Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2005. International Agency for Research on Cancer website. https://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/pat-gen/bb9/BB9.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

5. Sarath PV, Kannan N, Patil R, Manne RK, Swapna B, Suneel Kumar KV. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of the minor salivary glands involving palate and maxillary sinus. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2013;3(suppl 1):4.

6. Farrell T, Chang YL. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(10):1602-1604.

7. Jung MJ, Roh JL, Choi SH, et al. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of the salivary gland: a morphological and immunohistochemical comparison with basal cell adenoma with and without capsular invasion. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:171.

8. Jäkel KT, Löning T. Differential diagnosis of basaloid salivary gland tumors [in German]. Pathologe. 2004;25(1):46-55.

9. Urdaneta AI, Yu JB, Wilson LD. Population based cancer registry analysis of primary tracheal carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2011;34(1):32-37.

10. Varadhachary GR, Rabe MN. Cancer of unknown primary site. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(8):757-765.

11. Pelosi G, Fraggetta F, Maffini F, Solli P, Cavallon A, Viale G. Pulmonary epithelialmyoepithelial tumor of unproven malignant potential: report of a case and review

of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2001;14(5):521-526.

12. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004. International Agency for Research on Cancer website. https://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online /pat-gen/bb10/BB10.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2016.

13. García JJ, Jin L, Jackson SB, et al. Primary pulmonary hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma of bronchial submucosal gland origin. Hum Pathol. 2015;46(3):471-475.

14. Damiani S, Magrini E, Farnedi A, Pession A. Basal cell (myoepithelial) adenocarcinoma of the lung. First case with cytogenetic findings. Histopathology. 2004;45(4):422-424.

15. Yamada S, Noguchi H, Nabeshima A, et al. Basaloid carcinoma of the lung associated with central cavitation: a unique surgical case focusing on cytological and immunohistochemical findings. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:175-180.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.