User login

Experiences of Veterans With Diabetes From Shared Medical Appointments

Treatment of diabetes can be difficult and challenging. Information to improve the self-management behavior of patients with diabetes is important, because the prevalence of diabetes is expected to increase as the population ages, along with rising medical costs, premature death, and morbidity due to complications. Veterans, as a group, present unique challenges in health care. A recent analysis at a VA setting found only 17.3% of veterans were meeting all 3 of their “ABC” goals—A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol.1

Within the VA, diabetes is the third most common diagnosis, with a higher prevalence among veterans (25%) than among the general U.S. population (8.3%).2 However, little information exists about the barriers and motivations of the veterans who have completed a diabetes shared medical appointment (SMA) series.

The VA promotes SMAs as an effective alternative to one-on-one encounters for a cohort of patients with similar health conditions. In these SMAs, a multidisciplinary team meets with a group of patients for about 2 hours. These SMAs can be especially important for patients who need frequent encounters for care management, such as diabetes. Shared medical appointments focus on the American Association of Diabetes Educators 7 (AADE 7) self-care behaviors and provide a medium to foster improved self-management and healthy coping.3

Related: Education Pitfalls of Insulin Administration in Patients With Diabetes

Several systematic reviews of qualitative studies have identified and summarized factors that impact diabetes self-management.4,5 Behavioral science and social psychology provide rich examples of theories to influence and understand behaviors, including motivational interviewing and self-determinism.6,7 Other recent innovative approaches in primary care settings and diabetes self-management at the VA include companion (family or friend) participation in primary care visits, collaborative goal setting with patient and providers, age-matched patient pairing, and using a clinical pharmacist clinic as a midlevel provider to help meet VA national diabetes performance standards.8-11

In accordance with the Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) focus on the delivery of patient care, the goal of this study was to understand the experiences of veterans and to learn about the tools and methods they perceive to be most useful in improving patient education and motivation for self-management of diabetes. A onetime diabetes focus group was held to inquire about these specific issues.

Methods

The focus group took place at the Vancouver, Washington, campus of VA Portland Health Care System (VAPHCS). All veteran participants and their family members who had completed at least 3 of a 4-session SMA series were invited. Out of 29 invited veterans, 18 participated in the discussion along with 3 family members (all wives), for a total of 21 participants. The SMAs focused on meeting primary care performance standards on A1c, blood pressure, and hyperlipidemia, in accordance with the new PACT model. The VA education division approved the use of the Conversation Map for SMAs, created by Merck (Whitehouse Station, NJ) in collaboration with the American Diabetes Association. Using the Conversation Map format in a VA setting has been shown to reduce mean A1c levels by -0.9 (± 1.9%; P < .001).12 The SMA team made lifestyle and medication changes weekly (under a scope of practice for the pharmacist).

Data Gathering and Analysis

Participants attended a 2-hour focus group facilitated by the same 4 clinic care providers (2 pharmacists, 1 clinical nurse, 1 dietician) who had led the SMAs. The decision to have the discussion led by these same providers was grounded in the belief that this format would be familiar to the participants, and the rapport already established between providers and participants would encourage greater participation than if the meeting were led by unfamiliar VA employees. Two trained VAPHCS qualitative researchers attended the focus group and took extensive verbatim notes.

During the first 45 minutes, participants used a dot-voting technique to provide general demographic and background information in response to questions posted on boards around the room. Participants then were asked to choose their top 3 answers in response to each of a series of questions about barriers, resources, and motivators in self-management. The group was divided into 2 smaller groups of 10 or 11 participants, each facilitated by 2 researchers and assisted by a note-taker trained to capture the verbatim discussion. Session audio was not recorded, because VA policy requires signed consent, and this requirement might have discouraged participation.

The following questions guided the discussion: (1) Thinking back to when you were diagnosed with diabetes, what could you have done then that would have made a difference? (2) Thinking about all your experiences with diabetes, what was most helpful in motivating you to take control? (3) What one thing helped education or information “stick” with you? (4) What additional resources that are not currently available at the VA would help you? and (5) Tell us about your diabetes management plan.

Related: Diabetes Patient-Centered Medical Home Approach

After the focus groups, the research team used a formal debriefing tool to identify both initial impressions of possible discussion themes and group dynamics potentially influencing the content of the discussion; no significant communication or participation issues were identified.13 All research team members read the discussion notes and met to iteratively develop a simple codebook of global themes, using an approach of general inductive thematic content analysis.14

Two team members coded the notes, paying attention to the need to capture divergent or minority positions voiced by participants. Both coders worked toward consensus on code definitions through repeated discussions with each other and with the full research team. Codes were then used to sort and analyze about 180 comments made by participants during the focus groups. The Institutional Review Board of the VAPHCS approved the protocol for this study.

Results

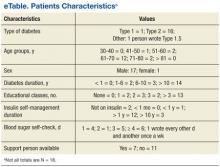

Most participants in the diabetes focus group had type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and were male—1 female veteran participated (eTable).

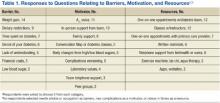

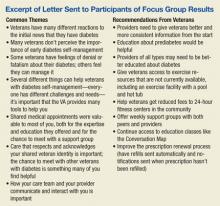

After the initial analysis, all participants were mailed a letter summarizing themes and suggestions from the meeting (see Box). Responses to questions posted on the board and responded to by voting are included in Table 1. Weight gain was most commonly chosen as a barrier to self-management. The A1c value was the highest rated motivator for self-management of diabetes, followed by face-to-face support from the care team and family support. Participants chose one-on-one appointments with the diabetes team and classes with instructors as the most helpful VA resources.

The final codebook resulted in 9 domains: diagnostic experience, what helps, perceived value of the SMA group, veteran identity, interaction with care providers, denial, fatalism, motivators, and barriers; each contained several related codes. Several themes emerged from the analysis of the focus group data for a desired experience of managing and coping with diabetes.

Identity as a Person With Diabetes

Participants were at various stages of their identity with a chronic illness. Over time, the veterans noted a transition from being a “diabetic person” to a “person living healthy with diabetes.” One veteran’s comment encapsulated the shift in diabetic identity over time: “[Initially] when looking up diabetes on the computer, there were scary things. It was very frightening, and I was thinking, oh, they’re going to cut off my legs. Years later you have more objectivity and control.”

Some participants responded with denial, rejecting that they had diabetes or that they needed to make lifestyle changes. When asked how he felt when first diagnosed, one veteran stated, “I resisted endlessly. I wouldn’t take my face out of the food.” Many veterans expressed that the diagnosis of diabetes was similar to an assault on their identity.

One veteran with long-standing diabetes shared the following: “I got a giant plastic box, and every needle [I use] goes into the box. Every day I look at this huge pile of needles. It’s my sign of weakness. If I kick it…I won’t keep adding them [to the pile].”

Similarly another veteran stated, “I felt like a failure, not a winner, when I started taking insulin.” The A1c test result was seen “like a hammer coming down,” an indication of the individual’s success or failure.

Identity as a Veteran

For some veterans in the focus group, the development of diabetes was considered to be service connected and related to chemical exposure to herbicides, including Agent Orange. One veteran emphasized, “This [diabetes] is ’cause of Agent Orange exposure.”

Another participant commented, “If you’ve served your country, you’re strong…[you think diabetes] can’t happen to you.” One participant explained, “Hearing it from [other veterans in focus group].... I don’t know if this was bred into me in the service. Probably. These guys have traversed the territory. I go to these guys for my answers. And hearing it from them, you could tell me everything I need to hear, and every one of these guys could tell me the exact same thing, and I would listen to them and not to [the clinical staff].”

Early Education

Another theme was a general desire for early information and education. Veterans suggested that information and self-management coaching when diagnosed with prediabetes would have been beneficial to reduce the risk of progression to diabetes. Many participants expressed regret that tools such as A1c monitoring were not available to them earlier: “I was also diagnosed borderline…that’s when I should have been hit by the 2 x 4...[they] should have done the A1c every 6 months.” Some participants described feelings that early education and, as one put it, “more emphasis on the seriousness of it,” would have helped them prevent their diabetes from worsening or develop healthier habits for self-management earlier.

Another veteran had what the group felt was the optimal experience: “The nurse told me I was diabetic...sat there for 45 minutes and just talked to me about it. It was the fact that she sat and talked with me and covered all the questions I had. That was the best thing bar none.”

Veterans expressed frustration with the time delay between the diagnosis and availability of clinical support and education: “When I first got the diagnosis, there was 4 or 5 weeks until the class. I’m thinking, what they should have done as soon as they sent that letter with the A1c, they should have sent me a packet saying, here’s what you can do NOW. Boom!”

Interventions

The chance to meet with other veterans with diabetes was something many participants said was helpful and provided a specific benefit that health care providers on their own could not give. One participant stated, “Classes make you feel more normal, when you sit with these people whose experiences you share.” Another stated, “When people have had a problem, get together and say how they’ve overcome it, I wanna hear about it.” The veterans agreed that someone who has specialty training in diabetes, not just in peer-to-peer support groups, should lead the education or support groups.

When the veterans were asked whether they thought that a veteran-led group would be beneficial, one veteran stated, “A support group must have a facilitator that has skills and resources.” Another stated, “You need at least one person to give you direction.”

One veteran explained that having weekly classes and hearing the same information several times helped information to “stick.” Another veteran, while expressing frustration about the lack of education he received on diet, stated, “What we eat directly affects us…classes like this are the greatest thing that ever happened. They give us more support than the doctors ever do.” One veteran described how having his weekly morning SMA class to look forward to was a strong motivation to pay attention to all the things that matter to his diabetes throughout the week. Another veteran emphasized the SMA as being important, because “being members of the military, you still have the civilians and they are them and we are us. ... With no family members, this [SMA] has made a big difference.”

Provider Relationship

Veterans expressed that having a positive provider relationship was an important element in diabetes self-management. The lack of time available for diabetes management in standard primary care encounters was cited as a barrier. One veteran stated, “[Providers] diagnose you with a blood test and [push you] out the door!” One veteran observed, “I think they need to turn you over to a nurse practitioner. You’re better off with someone like that who actually has time to talk to you instead of leaving you with someone who just gives you a prescription.”

The quality of the interaction mattered, and veterans felt that providers’ actions during the appointment could negatively affect the experience. One veteran summed up the groups’ feelings regarding their interactions with providers by saying, “[It is] key for our care providers to treat us like people. We should be able to ask them to get off of the computer and talk to us for a bit!” Other participants nodded in agreement, and one veteran remarked that he had a provider who had diabetes and “that was great.” The veterans also appreciated positive reinforcement from the primary care team. One participant remarked, “It’s nice to get the letter from my primary care provider with a little note saying you’re doing better.”

Resources

Participants had many suggestions regarding additional resources that they would like the VA to offer to help them self-manage diabetes. Many suggestions related to having greater access to resources for weight management through exercise or healthful eating. One participant stated, “An exercise facility…I think that’s key, and not just for diabetics.” Another participant noted, “In the VA, we have places to eat. Have you seen the food they give us to eat? Fatty, carbs, fried food.” However, many veterans were unclear about what resources the VA did offer, not knowing about certain resources such as diabetic shoes. When asked to prioritize what resources are most useful, given a scarcity, most participants insisted that a wide range of resources needed to be offered, because different people have different needs. One participant summed it up: “You can’t do away with primary care, you can’t do away with education, you can’t do away with pharmacy...[and] face-to-face makes all the difference in the world.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze the veteran experience with diabetes self-management and identify motivating factors and barriers in a population that had attended a primary care SMA series. The focus group had several interesting findings. A person’s identity or self-worth can be disrupted by the experience of chronic illness. Chronic illness can be conceptualized as a threat to one’s sense of security and identity.15 This disruption of identity at various stages of diabetes duration, from new onset to living many years with this chronic illness, is illustrated in the study participants’ comments of negotiating, adapting, and integrating diabetes into their lives.

This outcome is similar to findings by Olshansky and colleagues in which individuals struggled with the transition of becoming “a person with diabetes” rather than a “diabetic person.”16 Olshansky and colleagues suggested emphasizing lifestyle changes as health-related benefits for all people, those with and without diabetes, as a strategy to deal with normalizing their new identity; this concept can be viewed as a form of empowerment.

Related: A Shared Diabetes Clinic at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Furthermore, veteran identity was found to be an important factor for driving behaviors in diabetes care. This layering or double identity of diabetes plus being a veteran can be particularly challenging. Several participants commented on Agent Orange exposure during their service time as the etiology of their diabetes. Some of the veterans placed more value on what other fellow veterans said vs what health care professionals said. A study of nonveteran insulin users found that narratives or sharing of life stories of diabetes to be beneficial to the described assault on personal identity.17

As only about one-third of participants had a support person for their diabetes in this focus group, veteran-only groups likely have additional benefits, especially for those without family support. An additional complication of diabetes self-management in the veteran population is a disproportionate prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and substance abuse comorbidities (including alcoholism).

Of interest in this focus group was the low rating of peer-led groups as a motivator for successful diabetes self-management, perhaps because this was not offered at VAPHCS. Support or peer-led groups provide ongoing opportunities to address at least 2 of the AADE 7 self-care behaviors—problem solving and healthy coping. A recent 6-month study compared peer coaches, financial incentives, or usual care to promote behaviors for improved glucose control in African American veterans.18 Weekly telephone interventions by the peer mentors reduced A1c by 1.07% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.84%-0.31%) compared with 0.45% (95% CI, 1.23%-0.32%) in the group with financial incentives. The authors suggest transitioning patients who achieve control from mentee to mentor roles to maintain the program’s sustainability.

Nearly all participants endorsed the SMAs as valuable for the expertise and education they offered as well as for the chance to meet regularly with a veteran diabetes cohort group for support. The SMAs could be viewed as an avenue for shared narratives that may assist individuals in understanding their experiences and adapting to their chronic illness.

Using social psychology interventions to change behaviors may be challenging in busy primary care settings and hampered when veterans perceive only pressure to do what their providers recommend in a controlled behavior fashion. Individuals in a SMA may be more apt to act in a self-determined manner when they feel they are in control and activities are done with volition and a choice consistent with their identity when supported by their fellow diabetic veterans. A previous survey of VA provider and student perceptions that used an SMA for diabetes education in a primary care setting also found benefits, but sustainability issues were identified, such as limited resources (space), organization issues with clinic structure redesign, and potential to alter long-standing patient-provider relationships.19,20

An emphasis on A1c goals may be appropriate, because this was the highest rated motivator in the focus group, although care should be taken to tailor care to the needs of the veteran. A veteran population may be even more driven by constant evaluation of their success in reaching target goals. Education may be useful about how A1c relates to diabetes, such as self-monitoring of blood sugar, complications, and medications.

A study by Heisler and colleagues found that knowing A1c values was useful to patients to assess their diabetes control but not sufficient to increase confidence or motivation.21 In this mail survey of patients with T2DM, where the VA was 1 of 5 sites, 66% did not know their last A1c value, and only 25% accurately reported that value. The authors stated that it was unknown why VA respondents had significantly lower odds than did patients at the other sites of knowing their last A1c value. This study’s focus group was anonymous, and participants were not asked whether they accurately knew their A1c value or goal.

Limitations

One of the strengths of this study is that to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report of findings from a focus group on motivating factors and barriers for veterans with diabetes who had attended an SMA in a primary care setting. Although the study was small, the participation rate was high.

The study had a few limitations. The results might not be applicable to other populations, because all participants were veterans, predominantly male with T2DM. Selection bias is possible, because participants had already attended SMA classes. Participants may have been biased in their providing positive feedback of the SMA classes, since SMA facilitators held this focus group.

Conclusions

The study findings have several implications. Weight gain was ranked as the greatest barrier to self-managing diabetes in this focus group. Veterans stated they had limited resources, which could impact their AADE 7 self-care activities of being active and healthy eating. As resources allow, cooking classes, gym memberships, and VA-affiliated exercise facilities may be beneficial. Since there was heterogeneity in veteran experiences during diabetes diagnosis, consistent information should be provided upfront, including general concepts of diabetes and available resources.

This diabetes focus group highlighted the challenges of having a double identity, of being both a veteran and having diabetes. Shared medical appointments with veteran cohorts were identified as a promising intervention that allows for camaraderie and shared narratives to be enhanced by clinical guidance and education. By providing social support, SMAs may nudge fellow veterans to act on barriers that have them “stuck” in certain behaviors or situations. Many veterans view A1c as an important motivator, and this should be considered as a general educational tool.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, Egge A, Alexander B. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

2. Kupersmith J, Francis J, Kerr E, et al. Advancing evidence-based care for diabetes: lessons from the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(2):156-168.

3. Mulcahy K, Maryniuk M, Peeple M, et al. AADE Position Statement: standards for outcomes measurement of diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29(5):804-816.

4. Fitzpatrick SL, Schumann KP, Hill-Briggs F. Problem solving interventions for diabetes self-management and control: a systemic review of the literature. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;100(2):145-161.

5. Stellefson M, Dipnarine K, Stopka C. The chronic care model and diabetes management in US primary care settings: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:120180.

6. Heisler M, Resnicow K. Helping patients make and sustain healthy changes: a brief introduction to motivational interviewing in clinical diabetes care. Clin Diabetes. 2008;26(4):161-165.

7. Williams GC, Rodin GC, Ryan RM, Grolnick WS, Deci EL. Autonomous regulation and long-term medication adherence in adult outpatients. Health Psychol. 1998;17(3):269-276.

8. Rosland AM, Piette JD, Choi HJ, Heisler M. Family and friend participation in primary care visits of patients with diabetes or heart failure: patient and physician determinants and experiences. Med Care. 2011;49(1):37-45.

9. Lafata JE, Morris HL, Dobie E, Heisler M, Werner RM, Dumenci L. Patient-reported use of collaborative goal setting and glycemic control among patients with diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):94-99.

10. Heisler M, Vijan S, Makki F, Piette JD. Diabetes control with reciprocal peer support versus nurse care management: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(8):507-515.

11. Collier IA, Baker DM. Implementation of a pharmacist-supervised outpatient diabetes treatment clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(1):27-36.

12. Kirsch S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(5):349-353.

13. Moen J, Antonov K, Nilsson JLF. Interaction between participants in focus groups with older patients and general practitioners. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(5):607-616.

14. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288.

15. Aujoulat I, Marcolongo R, Bonadiman L, Deccache A. Reconsidering patient empowerment in chronic illness: a critique of models of self-efficacy and bodily control. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(5):1228-1239.

16. Olshansky E, Sacco D, Fitzgerald K, et al. Living with diabetes: normalizing the process of managing diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(6):1004-1012.

17. Goldman JB, Maclean HM. The significance of identity in the adjustment to diabetes among insulin users. Diabetes Educ. 1998;24(6):741-748.

18. Long JA, Jahnle EC, Richardson DM, Lowenstein G, Volpp KG. Peer mentoring and financial incentives to improve glucose control in African American veterans. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(6):416-424.

19. Kirsch SR, Schaub K, Aron DC. Shared medical appointments: a potential venue for education in interprofessional care. Qual Manag Health Care. 2009;18(3)217-224.

20. Kirsch SR, Lawrence RH, Aron DC. Tailoring an intervention to the context and system redesign related to the intervention: a case study of implementing shared medical appointments for diabetes. Implement Sci. 2008;3(suppl 1):34.

21. Heisler M, Piette JD, Spencer M, Kiefer E, Vijan S. The relationship between knowledge of recent HbA1c values and diabetes care understanding and self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(4):816-822.

Treatment of diabetes can be difficult and challenging. Information to improve the self-management behavior of patients with diabetes is important, because the prevalence of diabetes is expected to increase as the population ages, along with rising medical costs, premature death, and morbidity due to complications. Veterans, as a group, present unique challenges in health care. A recent analysis at a VA setting found only 17.3% of veterans were meeting all 3 of their “ABC” goals—A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol.1

Within the VA, diabetes is the third most common diagnosis, with a higher prevalence among veterans (25%) than among the general U.S. population (8.3%).2 However, little information exists about the barriers and motivations of the veterans who have completed a diabetes shared medical appointment (SMA) series.

The VA promotes SMAs as an effective alternative to one-on-one encounters for a cohort of patients with similar health conditions. In these SMAs, a multidisciplinary team meets with a group of patients for about 2 hours. These SMAs can be especially important for patients who need frequent encounters for care management, such as diabetes. Shared medical appointments focus on the American Association of Diabetes Educators 7 (AADE 7) self-care behaviors and provide a medium to foster improved self-management and healthy coping.3

Related: Education Pitfalls of Insulin Administration in Patients With Diabetes

Several systematic reviews of qualitative studies have identified and summarized factors that impact diabetes self-management.4,5 Behavioral science and social psychology provide rich examples of theories to influence and understand behaviors, including motivational interviewing and self-determinism.6,7 Other recent innovative approaches in primary care settings and diabetes self-management at the VA include companion (family or friend) participation in primary care visits, collaborative goal setting with patient and providers, age-matched patient pairing, and using a clinical pharmacist clinic as a midlevel provider to help meet VA national diabetes performance standards.8-11

In accordance with the Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) focus on the delivery of patient care, the goal of this study was to understand the experiences of veterans and to learn about the tools and methods they perceive to be most useful in improving patient education and motivation for self-management of diabetes. A onetime diabetes focus group was held to inquire about these specific issues.

Methods

The focus group took place at the Vancouver, Washington, campus of VA Portland Health Care System (VAPHCS). All veteran participants and their family members who had completed at least 3 of a 4-session SMA series were invited. Out of 29 invited veterans, 18 participated in the discussion along with 3 family members (all wives), for a total of 21 participants. The SMAs focused on meeting primary care performance standards on A1c, blood pressure, and hyperlipidemia, in accordance with the new PACT model. The VA education division approved the use of the Conversation Map for SMAs, created by Merck (Whitehouse Station, NJ) in collaboration with the American Diabetes Association. Using the Conversation Map format in a VA setting has been shown to reduce mean A1c levels by -0.9 (± 1.9%; P < .001).12 The SMA team made lifestyle and medication changes weekly (under a scope of practice for the pharmacist).

Data Gathering and Analysis

Participants attended a 2-hour focus group facilitated by the same 4 clinic care providers (2 pharmacists, 1 clinical nurse, 1 dietician) who had led the SMAs. The decision to have the discussion led by these same providers was grounded in the belief that this format would be familiar to the participants, and the rapport already established between providers and participants would encourage greater participation than if the meeting were led by unfamiliar VA employees. Two trained VAPHCS qualitative researchers attended the focus group and took extensive verbatim notes.

During the first 45 minutes, participants used a dot-voting technique to provide general demographic and background information in response to questions posted on boards around the room. Participants then were asked to choose their top 3 answers in response to each of a series of questions about barriers, resources, and motivators in self-management. The group was divided into 2 smaller groups of 10 or 11 participants, each facilitated by 2 researchers and assisted by a note-taker trained to capture the verbatim discussion. Session audio was not recorded, because VA policy requires signed consent, and this requirement might have discouraged participation.

The following questions guided the discussion: (1) Thinking back to when you were diagnosed with diabetes, what could you have done then that would have made a difference? (2) Thinking about all your experiences with diabetes, what was most helpful in motivating you to take control? (3) What one thing helped education or information “stick” with you? (4) What additional resources that are not currently available at the VA would help you? and (5) Tell us about your diabetes management plan.

Related: Diabetes Patient-Centered Medical Home Approach

After the focus groups, the research team used a formal debriefing tool to identify both initial impressions of possible discussion themes and group dynamics potentially influencing the content of the discussion; no significant communication or participation issues were identified.13 All research team members read the discussion notes and met to iteratively develop a simple codebook of global themes, using an approach of general inductive thematic content analysis.14

Two team members coded the notes, paying attention to the need to capture divergent or minority positions voiced by participants. Both coders worked toward consensus on code definitions through repeated discussions with each other and with the full research team. Codes were then used to sort and analyze about 180 comments made by participants during the focus groups. The Institutional Review Board of the VAPHCS approved the protocol for this study.

Results

Most participants in the diabetes focus group had type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and were male—1 female veteran participated (eTable).

After the initial analysis, all participants were mailed a letter summarizing themes and suggestions from the meeting (see Box). Responses to questions posted on the board and responded to by voting are included in Table 1. Weight gain was most commonly chosen as a barrier to self-management. The A1c value was the highest rated motivator for self-management of diabetes, followed by face-to-face support from the care team and family support. Participants chose one-on-one appointments with the diabetes team and classes with instructors as the most helpful VA resources.

The final codebook resulted in 9 domains: diagnostic experience, what helps, perceived value of the SMA group, veteran identity, interaction with care providers, denial, fatalism, motivators, and barriers; each contained several related codes. Several themes emerged from the analysis of the focus group data for a desired experience of managing and coping with diabetes.

Identity as a Person With Diabetes

Participants were at various stages of their identity with a chronic illness. Over time, the veterans noted a transition from being a “diabetic person” to a “person living healthy with diabetes.” One veteran’s comment encapsulated the shift in diabetic identity over time: “[Initially] when looking up diabetes on the computer, there were scary things. It was very frightening, and I was thinking, oh, they’re going to cut off my legs. Years later you have more objectivity and control.”

Some participants responded with denial, rejecting that they had diabetes or that they needed to make lifestyle changes. When asked how he felt when first diagnosed, one veteran stated, “I resisted endlessly. I wouldn’t take my face out of the food.” Many veterans expressed that the diagnosis of diabetes was similar to an assault on their identity.

One veteran with long-standing diabetes shared the following: “I got a giant plastic box, and every needle [I use] goes into the box. Every day I look at this huge pile of needles. It’s my sign of weakness. If I kick it…I won’t keep adding them [to the pile].”

Similarly another veteran stated, “I felt like a failure, not a winner, when I started taking insulin.” The A1c test result was seen “like a hammer coming down,” an indication of the individual’s success or failure.

Identity as a Veteran

For some veterans in the focus group, the development of diabetes was considered to be service connected and related to chemical exposure to herbicides, including Agent Orange. One veteran emphasized, “This [diabetes] is ’cause of Agent Orange exposure.”

Another participant commented, “If you’ve served your country, you’re strong…[you think diabetes] can’t happen to you.” One participant explained, “Hearing it from [other veterans in focus group].... I don’t know if this was bred into me in the service. Probably. These guys have traversed the territory. I go to these guys for my answers. And hearing it from them, you could tell me everything I need to hear, and every one of these guys could tell me the exact same thing, and I would listen to them and not to [the clinical staff].”

Early Education

Another theme was a general desire for early information and education. Veterans suggested that information and self-management coaching when diagnosed with prediabetes would have been beneficial to reduce the risk of progression to diabetes. Many participants expressed regret that tools such as A1c monitoring were not available to them earlier: “I was also diagnosed borderline…that’s when I should have been hit by the 2 x 4...[they] should have done the A1c every 6 months.” Some participants described feelings that early education and, as one put it, “more emphasis on the seriousness of it,” would have helped them prevent their diabetes from worsening or develop healthier habits for self-management earlier.

Another veteran had what the group felt was the optimal experience: “The nurse told me I was diabetic...sat there for 45 minutes and just talked to me about it. It was the fact that she sat and talked with me and covered all the questions I had. That was the best thing bar none.”

Veterans expressed frustration with the time delay between the diagnosis and availability of clinical support and education: “When I first got the diagnosis, there was 4 or 5 weeks until the class. I’m thinking, what they should have done as soon as they sent that letter with the A1c, they should have sent me a packet saying, here’s what you can do NOW. Boom!”

Interventions

The chance to meet with other veterans with diabetes was something many participants said was helpful and provided a specific benefit that health care providers on their own could not give. One participant stated, “Classes make you feel more normal, when you sit with these people whose experiences you share.” Another stated, “When people have had a problem, get together and say how they’ve overcome it, I wanna hear about it.” The veterans agreed that someone who has specialty training in diabetes, not just in peer-to-peer support groups, should lead the education or support groups.

When the veterans were asked whether they thought that a veteran-led group would be beneficial, one veteran stated, “A support group must have a facilitator that has skills and resources.” Another stated, “You need at least one person to give you direction.”

One veteran explained that having weekly classes and hearing the same information several times helped information to “stick.” Another veteran, while expressing frustration about the lack of education he received on diet, stated, “What we eat directly affects us…classes like this are the greatest thing that ever happened. They give us more support than the doctors ever do.” One veteran described how having his weekly morning SMA class to look forward to was a strong motivation to pay attention to all the things that matter to his diabetes throughout the week. Another veteran emphasized the SMA as being important, because “being members of the military, you still have the civilians and they are them and we are us. ... With no family members, this [SMA] has made a big difference.”

Provider Relationship

Veterans expressed that having a positive provider relationship was an important element in diabetes self-management. The lack of time available for diabetes management in standard primary care encounters was cited as a barrier. One veteran stated, “[Providers] diagnose you with a blood test and [push you] out the door!” One veteran observed, “I think they need to turn you over to a nurse practitioner. You’re better off with someone like that who actually has time to talk to you instead of leaving you with someone who just gives you a prescription.”

The quality of the interaction mattered, and veterans felt that providers’ actions during the appointment could negatively affect the experience. One veteran summed up the groups’ feelings regarding their interactions with providers by saying, “[It is] key for our care providers to treat us like people. We should be able to ask them to get off of the computer and talk to us for a bit!” Other participants nodded in agreement, and one veteran remarked that he had a provider who had diabetes and “that was great.” The veterans also appreciated positive reinforcement from the primary care team. One participant remarked, “It’s nice to get the letter from my primary care provider with a little note saying you’re doing better.”

Resources

Participants had many suggestions regarding additional resources that they would like the VA to offer to help them self-manage diabetes. Many suggestions related to having greater access to resources for weight management through exercise or healthful eating. One participant stated, “An exercise facility…I think that’s key, and not just for diabetics.” Another participant noted, “In the VA, we have places to eat. Have you seen the food they give us to eat? Fatty, carbs, fried food.” However, many veterans were unclear about what resources the VA did offer, not knowing about certain resources such as diabetic shoes. When asked to prioritize what resources are most useful, given a scarcity, most participants insisted that a wide range of resources needed to be offered, because different people have different needs. One participant summed it up: “You can’t do away with primary care, you can’t do away with education, you can’t do away with pharmacy...[and] face-to-face makes all the difference in the world.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze the veteran experience with diabetes self-management and identify motivating factors and barriers in a population that had attended a primary care SMA series. The focus group had several interesting findings. A person’s identity or self-worth can be disrupted by the experience of chronic illness. Chronic illness can be conceptualized as a threat to one’s sense of security and identity.15 This disruption of identity at various stages of diabetes duration, from new onset to living many years with this chronic illness, is illustrated in the study participants’ comments of negotiating, adapting, and integrating diabetes into their lives.

This outcome is similar to findings by Olshansky and colleagues in which individuals struggled with the transition of becoming “a person with diabetes” rather than a “diabetic person.”16 Olshansky and colleagues suggested emphasizing lifestyle changes as health-related benefits for all people, those with and without diabetes, as a strategy to deal with normalizing their new identity; this concept can be viewed as a form of empowerment.

Related: A Shared Diabetes Clinic at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Furthermore, veteran identity was found to be an important factor for driving behaviors in diabetes care. This layering or double identity of diabetes plus being a veteran can be particularly challenging. Several participants commented on Agent Orange exposure during their service time as the etiology of their diabetes. Some of the veterans placed more value on what other fellow veterans said vs what health care professionals said. A study of nonveteran insulin users found that narratives or sharing of life stories of diabetes to be beneficial to the described assault on personal identity.17

As only about one-third of participants had a support person for their diabetes in this focus group, veteran-only groups likely have additional benefits, especially for those without family support. An additional complication of diabetes self-management in the veteran population is a disproportionate prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and substance abuse comorbidities (including alcoholism).

Of interest in this focus group was the low rating of peer-led groups as a motivator for successful diabetes self-management, perhaps because this was not offered at VAPHCS. Support or peer-led groups provide ongoing opportunities to address at least 2 of the AADE 7 self-care behaviors—problem solving and healthy coping. A recent 6-month study compared peer coaches, financial incentives, or usual care to promote behaviors for improved glucose control in African American veterans.18 Weekly telephone interventions by the peer mentors reduced A1c by 1.07% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.84%-0.31%) compared with 0.45% (95% CI, 1.23%-0.32%) in the group with financial incentives. The authors suggest transitioning patients who achieve control from mentee to mentor roles to maintain the program’s sustainability.

Nearly all participants endorsed the SMAs as valuable for the expertise and education they offered as well as for the chance to meet regularly with a veteran diabetes cohort group for support. The SMAs could be viewed as an avenue for shared narratives that may assist individuals in understanding their experiences and adapting to their chronic illness.

Using social psychology interventions to change behaviors may be challenging in busy primary care settings and hampered when veterans perceive only pressure to do what their providers recommend in a controlled behavior fashion. Individuals in a SMA may be more apt to act in a self-determined manner when they feel they are in control and activities are done with volition and a choice consistent with their identity when supported by their fellow diabetic veterans. A previous survey of VA provider and student perceptions that used an SMA for diabetes education in a primary care setting also found benefits, but sustainability issues were identified, such as limited resources (space), organization issues with clinic structure redesign, and potential to alter long-standing patient-provider relationships.19,20

An emphasis on A1c goals may be appropriate, because this was the highest rated motivator in the focus group, although care should be taken to tailor care to the needs of the veteran. A veteran population may be even more driven by constant evaluation of their success in reaching target goals. Education may be useful about how A1c relates to diabetes, such as self-monitoring of blood sugar, complications, and medications.

A study by Heisler and colleagues found that knowing A1c values was useful to patients to assess their diabetes control but not sufficient to increase confidence or motivation.21 In this mail survey of patients with T2DM, where the VA was 1 of 5 sites, 66% did not know their last A1c value, and only 25% accurately reported that value. The authors stated that it was unknown why VA respondents had significantly lower odds than did patients at the other sites of knowing their last A1c value. This study’s focus group was anonymous, and participants were not asked whether they accurately knew their A1c value or goal.

Limitations

One of the strengths of this study is that to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report of findings from a focus group on motivating factors and barriers for veterans with diabetes who had attended an SMA in a primary care setting. Although the study was small, the participation rate was high.

The study had a few limitations. The results might not be applicable to other populations, because all participants were veterans, predominantly male with T2DM. Selection bias is possible, because participants had already attended SMA classes. Participants may have been biased in their providing positive feedback of the SMA classes, since SMA facilitators held this focus group.

Conclusions

The study findings have several implications. Weight gain was ranked as the greatest barrier to self-managing diabetes in this focus group. Veterans stated they had limited resources, which could impact their AADE 7 self-care activities of being active and healthy eating. As resources allow, cooking classes, gym memberships, and VA-affiliated exercise facilities may be beneficial. Since there was heterogeneity in veteran experiences during diabetes diagnosis, consistent information should be provided upfront, including general concepts of diabetes and available resources.

This diabetes focus group highlighted the challenges of having a double identity, of being both a veteran and having diabetes. Shared medical appointments with veteran cohorts were identified as a promising intervention that allows for camaraderie and shared narratives to be enhanced by clinical guidance and education. By providing social support, SMAs may nudge fellow veterans to act on barriers that have them “stuck” in certain behaviors or situations. Many veterans view A1c as an important motivator, and this should be considered as a general educational tool.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Treatment of diabetes can be difficult and challenging. Information to improve the self-management behavior of patients with diabetes is important, because the prevalence of diabetes is expected to increase as the population ages, along with rising medical costs, premature death, and morbidity due to complications. Veterans, as a group, present unique challenges in health care. A recent analysis at a VA setting found only 17.3% of veterans were meeting all 3 of their “ABC” goals—A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol.1

Within the VA, diabetes is the third most common diagnosis, with a higher prevalence among veterans (25%) than among the general U.S. population (8.3%).2 However, little information exists about the barriers and motivations of the veterans who have completed a diabetes shared medical appointment (SMA) series.

The VA promotes SMAs as an effective alternative to one-on-one encounters for a cohort of patients with similar health conditions. In these SMAs, a multidisciplinary team meets with a group of patients for about 2 hours. These SMAs can be especially important for patients who need frequent encounters for care management, such as diabetes. Shared medical appointments focus on the American Association of Diabetes Educators 7 (AADE 7) self-care behaviors and provide a medium to foster improved self-management and healthy coping.3

Related: Education Pitfalls of Insulin Administration in Patients With Diabetes

Several systematic reviews of qualitative studies have identified and summarized factors that impact diabetes self-management.4,5 Behavioral science and social psychology provide rich examples of theories to influence and understand behaviors, including motivational interviewing and self-determinism.6,7 Other recent innovative approaches in primary care settings and diabetes self-management at the VA include companion (family or friend) participation in primary care visits, collaborative goal setting with patient and providers, age-matched patient pairing, and using a clinical pharmacist clinic as a midlevel provider to help meet VA national diabetes performance standards.8-11

In accordance with the Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) focus on the delivery of patient care, the goal of this study was to understand the experiences of veterans and to learn about the tools and methods they perceive to be most useful in improving patient education and motivation for self-management of diabetes. A onetime diabetes focus group was held to inquire about these specific issues.

Methods

The focus group took place at the Vancouver, Washington, campus of VA Portland Health Care System (VAPHCS). All veteran participants and their family members who had completed at least 3 of a 4-session SMA series were invited. Out of 29 invited veterans, 18 participated in the discussion along with 3 family members (all wives), for a total of 21 participants. The SMAs focused on meeting primary care performance standards on A1c, blood pressure, and hyperlipidemia, in accordance with the new PACT model. The VA education division approved the use of the Conversation Map for SMAs, created by Merck (Whitehouse Station, NJ) in collaboration with the American Diabetes Association. Using the Conversation Map format in a VA setting has been shown to reduce mean A1c levels by -0.9 (± 1.9%; P < .001).12 The SMA team made lifestyle and medication changes weekly (under a scope of practice for the pharmacist).

Data Gathering and Analysis

Participants attended a 2-hour focus group facilitated by the same 4 clinic care providers (2 pharmacists, 1 clinical nurse, 1 dietician) who had led the SMAs. The decision to have the discussion led by these same providers was grounded in the belief that this format would be familiar to the participants, and the rapport already established between providers and participants would encourage greater participation than if the meeting were led by unfamiliar VA employees. Two trained VAPHCS qualitative researchers attended the focus group and took extensive verbatim notes.

During the first 45 minutes, participants used a dot-voting technique to provide general demographic and background information in response to questions posted on boards around the room. Participants then were asked to choose their top 3 answers in response to each of a series of questions about barriers, resources, and motivators in self-management. The group was divided into 2 smaller groups of 10 or 11 participants, each facilitated by 2 researchers and assisted by a note-taker trained to capture the verbatim discussion. Session audio was not recorded, because VA policy requires signed consent, and this requirement might have discouraged participation.

The following questions guided the discussion: (1) Thinking back to when you were diagnosed with diabetes, what could you have done then that would have made a difference? (2) Thinking about all your experiences with diabetes, what was most helpful in motivating you to take control? (3) What one thing helped education or information “stick” with you? (4) What additional resources that are not currently available at the VA would help you? and (5) Tell us about your diabetes management plan.

Related: Diabetes Patient-Centered Medical Home Approach

After the focus groups, the research team used a formal debriefing tool to identify both initial impressions of possible discussion themes and group dynamics potentially influencing the content of the discussion; no significant communication or participation issues were identified.13 All research team members read the discussion notes and met to iteratively develop a simple codebook of global themes, using an approach of general inductive thematic content analysis.14

Two team members coded the notes, paying attention to the need to capture divergent or minority positions voiced by participants. Both coders worked toward consensus on code definitions through repeated discussions with each other and with the full research team. Codes were then used to sort and analyze about 180 comments made by participants during the focus groups. The Institutional Review Board of the VAPHCS approved the protocol for this study.

Results

Most participants in the diabetes focus group had type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and were male—1 female veteran participated (eTable).

After the initial analysis, all participants were mailed a letter summarizing themes and suggestions from the meeting (see Box). Responses to questions posted on the board and responded to by voting are included in Table 1. Weight gain was most commonly chosen as a barrier to self-management. The A1c value was the highest rated motivator for self-management of diabetes, followed by face-to-face support from the care team and family support. Participants chose one-on-one appointments with the diabetes team and classes with instructors as the most helpful VA resources.

The final codebook resulted in 9 domains: diagnostic experience, what helps, perceived value of the SMA group, veteran identity, interaction with care providers, denial, fatalism, motivators, and barriers; each contained several related codes. Several themes emerged from the analysis of the focus group data for a desired experience of managing and coping with diabetes.

Identity as a Person With Diabetes

Participants were at various stages of their identity with a chronic illness. Over time, the veterans noted a transition from being a “diabetic person” to a “person living healthy with diabetes.” One veteran’s comment encapsulated the shift in diabetic identity over time: “[Initially] when looking up diabetes on the computer, there were scary things. It was very frightening, and I was thinking, oh, they’re going to cut off my legs. Years later you have more objectivity and control.”

Some participants responded with denial, rejecting that they had diabetes or that they needed to make lifestyle changes. When asked how he felt when first diagnosed, one veteran stated, “I resisted endlessly. I wouldn’t take my face out of the food.” Many veterans expressed that the diagnosis of diabetes was similar to an assault on their identity.

One veteran with long-standing diabetes shared the following: “I got a giant plastic box, and every needle [I use] goes into the box. Every day I look at this huge pile of needles. It’s my sign of weakness. If I kick it…I won’t keep adding them [to the pile].”

Similarly another veteran stated, “I felt like a failure, not a winner, when I started taking insulin.” The A1c test result was seen “like a hammer coming down,” an indication of the individual’s success or failure.

Identity as a Veteran

For some veterans in the focus group, the development of diabetes was considered to be service connected and related to chemical exposure to herbicides, including Agent Orange. One veteran emphasized, “This [diabetes] is ’cause of Agent Orange exposure.”

Another participant commented, “If you’ve served your country, you’re strong…[you think diabetes] can’t happen to you.” One participant explained, “Hearing it from [other veterans in focus group].... I don’t know if this was bred into me in the service. Probably. These guys have traversed the territory. I go to these guys for my answers. And hearing it from them, you could tell me everything I need to hear, and every one of these guys could tell me the exact same thing, and I would listen to them and not to [the clinical staff].”

Early Education

Another theme was a general desire for early information and education. Veterans suggested that information and self-management coaching when diagnosed with prediabetes would have been beneficial to reduce the risk of progression to diabetes. Many participants expressed regret that tools such as A1c monitoring were not available to them earlier: “I was also diagnosed borderline…that’s when I should have been hit by the 2 x 4...[they] should have done the A1c every 6 months.” Some participants described feelings that early education and, as one put it, “more emphasis on the seriousness of it,” would have helped them prevent their diabetes from worsening or develop healthier habits for self-management earlier.

Another veteran had what the group felt was the optimal experience: “The nurse told me I was diabetic...sat there for 45 minutes and just talked to me about it. It was the fact that she sat and talked with me and covered all the questions I had. That was the best thing bar none.”

Veterans expressed frustration with the time delay between the diagnosis and availability of clinical support and education: “When I first got the diagnosis, there was 4 or 5 weeks until the class. I’m thinking, what they should have done as soon as they sent that letter with the A1c, they should have sent me a packet saying, here’s what you can do NOW. Boom!”

Interventions

The chance to meet with other veterans with diabetes was something many participants said was helpful and provided a specific benefit that health care providers on their own could not give. One participant stated, “Classes make you feel more normal, when you sit with these people whose experiences you share.” Another stated, “When people have had a problem, get together and say how they’ve overcome it, I wanna hear about it.” The veterans agreed that someone who has specialty training in diabetes, not just in peer-to-peer support groups, should lead the education or support groups.

When the veterans were asked whether they thought that a veteran-led group would be beneficial, one veteran stated, “A support group must have a facilitator that has skills and resources.” Another stated, “You need at least one person to give you direction.”

One veteran explained that having weekly classes and hearing the same information several times helped information to “stick.” Another veteran, while expressing frustration about the lack of education he received on diet, stated, “What we eat directly affects us…classes like this are the greatest thing that ever happened. They give us more support than the doctors ever do.” One veteran described how having his weekly morning SMA class to look forward to was a strong motivation to pay attention to all the things that matter to his diabetes throughout the week. Another veteran emphasized the SMA as being important, because “being members of the military, you still have the civilians and they are them and we are us. ... With no family members, this [SMA] has made a big difference.”

Provider Relationship

Veterans expressed that having a positive provider relationship was an important element in diabetes self-management. The lack of time available for diabetes management in standard primary care encounters was cited as a barrier. One veteran stated, “[Providers] diagnose you with a blood test and [push you] out the door!” One veteran observed, “I think they need to turn you over to a nurse practitioner. You’re better off with someone like that who actually has time to talk to you instead of leaving you with someone who just gives you a prescription.”

The quality of the interaction mattered, and veterans felt that providers’ actions during the appointment could negatively affect the experience. One veteran summed up the groups’ feelings regarding their interactions with providers by saying, “[It is] key for our care providers to treat us like people. We should be able to ask them to get off of the computer and talk to us for a bit!” Other participants nodded in agreement, and one veteran remarked that he had a provider who had diabetes and “that was great.” The veterans also appreciated positive reinforcement from the primary care team. One participant remarked, “It’s nice to get the letter from my primary care provider with a little note saying you’re doing better.”

Resources

Participants had many suggestions regarding additional resources that they would like the VA to offer to help them self-manage diabetes. Many suggestions related to having greater access to resources for weight management through exercise or healthful eating. One participant stated, “An exercise facility…I think that’s key, and not just for diabetics.” Another participant noted, “In the VA, we have places to eat. Have you seen the food they give us to eat? Fatty, carbs, fried food.” However, many veterans were unclear about what resources the VA did offer, not knowing about certain resources such as diabetic shoes. When asked to prioritize what resources are most useful, given a scarcity, most participants insisted that a wide range of resources needed to be offered, because different people have different needs. One participant summed it up: “You can’t do away with primary care, you can’t do away with education, you can’t do away with pharmacy...[and] face-to-face makes all the difference in the world.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze the veteran experience with diabetes self-management and identify motivating factors and barriers in a population that had attended a primary care SMA series. The focus group had several interesting findings. A person’s identity or self-worth can be disrupted by the experience of chronic illness. Chronic illness can be conceptualized as a threat to one’s sense of security and identity.15 This disruption of identity at various stages of diabetes duration, from new onset to living many years with this chronic illness, is illustrated in the study participants’ comments of negotiating, adapting, and integrating diabetes into their lives.

This outcome is similar to findings by Olshansky and colleagues in which individuals struggled with the transition of becoming “a person with diabetes” rather than a “diabetic person.”16 Olshansky and colleagues suggested emphasizing lifestyle changes as health-related benefits for all people, those with and without diabetes, as a strategy to deal with normalizing their new identity; this concept can be viewed as a form of empowerment.

Related: A Shared Diabetes Clinic at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Furthermore, veteran identity was found to be an important factor for driving behaviors in diabetes care. This layering or double identity of diabetes plus being a veteran can be particularly challenging. Several participants commented on Agent Orange exposure during their service time as the etiology of their diabetes. Some of the veterans placed more value on what other fellow veterans said vs what health care professionals said. A study of nonveteran insulin users found that narratives or sharing of life stories of diabetes to be beneficial to the described assault on personal identity.17

As only about one-third of participants had a support person for their diabetes in this focus group, veteran-only groups likely have additional benefits, especially for those without family support. An additional complication of diabetes self-management in the veteran population is a disproportionate prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and substance abuse comorbidities (including alcoholism).

Of interest in this focus group was the low rating of peer-led groups as a motivator for successful diabetes self-management, perhaps because this was not offered at VAPHCS. Support or peer-led groups provide ongoing opportunities to address at least 2 of the AADE 7 self-care behaviors—problem solving and healthy coping. A recent 6-month study compared peer coaches, financial incentives, or usual care to promote behaviors for improved glucose control in African American veterans.18 Weekly telephone interventions by the peer mentors reduced A1c by 1.07% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.84%-0.31%) compared with 0.45% (95% CI, 1.23%-0.32%) in the group with financial incentives. The authors suggest transitioning patients who achieve control from mentee to mentor roles to maintain the program’s sustainability.

Nearly all participants endorsed the SMAs as valuable for the expertise and education they offered as well as for the chance to meet regularly with a veteran diabetes cohort group for support. The SMAs could be viewed as an avenue for shared narratives that may assist individuals in understanding their experiences and adapting to their chronic illness.

Using social psychology interventions to change behaviors may be challenging in busy primary care settings and hampered when veterans perceive only pressure to do what their providers recommend in a controlled behavior fashion. Individuals in a SMA may be more apt to act in a self-determined manner when they feel they are in control and activities are done with volition and a choice consistent with their identity when supported by their fellow diabetic veterans. A previous survey of VA provider and student perceptions that used an SMA for diabetes education in a primary care setting also found benefits, but sustainability issues were identified, such as limited resources (space), organization issues with clinic structure redesign, and potential to alter long-standing patient-provider relationships.19,20

An emphasis on A1c goals may be appropriate, because this was the highest rated motivator in the focus group, although care should be taken to tailor care to the needs of the veteran. A veteran population may be even more driven by constant evaluation of their success in reaching target goals. Education may be useful about how A1c relates to diabetes, such as self-monitoring of blood sugar, complications, and medications.

A study by Heisler and colleagues found that knowing A1c values was useful to patients to assess their diabetes control but not sufficient to increase confidence or motivation.21 In this mail survey of patients with T2DM, where the VA was 1 of 5 sites, 66% did not know their last A1c value, and only 25% accurately reported that value. The authors stated that it was unknown why VA respondents had significantly lower odds than did patients at the other sites of knowing their last A1c value. This study’s focus group was anonymous, and participants were not asked whether they accurately knew their A1c value or goal.

Limitations

One of the strengths of this study is that to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report of findings from a focus group on motivating factors and barriers for veterans with diabetes who had attended an SMA in a primary care setting. Although the study was small, the participation rate was high.

The study had a few limitations. The results might not be applicable to other populations, because all participants were veterans, predominantly male with T2DM. Selection bias is possible, because participants had already attended SMA classes. Participants may have been biased in their providing positive feedback of the SMA classes, since SMA facilitators held this focus group.

Conclusions

The study findings have several implications. Weight gain was ranked as the greatest barrier to self-managing diabetes in this focus group. Veterans stated they had limited resources, which could impact their AADE 7 self-care activities of being active and healthy eating. As resources allow, cooking classes, gym memberships, and VA-affiliated exercise facilities may be beneficial. Since there was heterogeneity in veteran experiences during diabetes diagnosis, consistent information should be provided upfront, including general concepts of diabetes and available resources.

This diabetes focus group highlighted the challenges of having a double identity, of being both a veteran and having diabetes. Shared medical appointments with veteran cohorts were identified as a promising intervention that allows for camaraderie and shared narratives to be enhanced by clinical guidance and education. By providing social support, SMAs may nudge fellow veterans to act on barriers that have them “stuck” in certain behaviors or situations. Many veterans view A1c as an important motivator, and this should be considered as a general educational tool.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, Egge A, Alexander B. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

2. Kupersmith J, Francis J, Kerr E, et al. Advancing evidence-based care for diabetes: lessons from the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(2):156-168.

3. Mulcahy K, Maryniuk M, Peeple M, et al. AADE Position Statement: standards for outcomes measurement of diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29(5):804-816.

4. Fitzpatrick SL, Schumann KP, Hill-Briggs F. Problem solving interventions for diabetes self-management and control: a systemic review of the literature. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;100(2):145-161.

5. Stellefson M, Dipnarine K, Stopka C. The chronic care model and diabetes management in US primary care settings: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:120180.

6. Heisler M, Resnicow K. Helping patients make and sustain healthy changes: a brief introduction to motivational interviewing in clinical diabetes care. Clin Diabetes. 2008;26(4):161-165.

7. Williams GC, Rodin GC, Ryan RM, Grolnick WS, Deci EL. Autonomous regulation and long-term medication adherence in adult outpatients. Health Psychol. 1998;17(3):269-276.

8. Rosland AM, Piette JD, Choi HJ, Heisler M. Family and friend participation in primary care visits of patients with diabetes or heart failure: patient and physician determinants and experiences. Med Care. 2011;49(1):37-45.

9. Lafata JE, Morris HL, Dobie E, Heisler M, Werner RM, Dumenci L. Patient-reported use of collaborative goal setting and glycemic control among patients with diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):94-99.

10. Heisler M, Vijan S, Makki F, Piette JD. Diabetes control with reciprocal peer support versus nurse care management: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(8):507-515.

11. Collier IA, Baker DM. Implementation of a pharmacist-supervised outpatient diabetes treatment clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(1):27-36.

12. Kirsch S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(5):349-353.

13. Moen J, Antonov K, Nilsson JLF. Interaction between participants in focus groups with older patients and general practitioners. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(5):607-616.

14. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288.

15. Aujoulat I, Marcolongo R, Bonadiman L, Deccache A. Reconsidering patient empowerment in chronic illness: a critique of models of self-efficacy and bodily control. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(5):1228-1239.

16. Olshansky E, Sacco D, Fitzgerald K, et al. Living with diabetes: normalizing the process of managing diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(6):1004-1012.

17. Goldman JB, Maclean HM. The significance of identity in the adjustment to diabetes among insulin users. Diabetes Educ. 1998;24(6):741-748.

18. Long JA, Jahnle EC, Richardson DM, Lowenstein G, Volpp KG. Peer mentoring and financial incentives to improve glucose control in African American veterans. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(6):416-424.

19. Kirsch SR, Schaub K, Aron DC. Shared medical appointments: a potential venue for education in interprofessional care. Qual Manag Health Care. 2009;18(3)217-224.

20. Kirsch SR, Lawrence RH, Aron DC. Tailoring an intervention to the context and system redesign related to the intervention: a case study of implementing shared medical appointments for diabetes. Implement Sci. 2008;3(suppl 1):34.

21. Heisler M, Piette JD, Spencer M, Kiefer E, Vijan S. The relationship between knowledge of recent HbA1c values and diabetes care understanding and self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(4):816-822.

1. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, Egge A, Alexander B. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

2. Kupersmith J, Francis J, Kerr E, et al. Advancing evidence-based care for diabetes: lessons from the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(2):156-168.

3. Mulcahy K, Maryniuk M, Peeple M, et al. AADE Position Statement: standards for outcomes measurement of diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29(5):804-816.

4. Fitzpatrick SL, Schumann KP, Hill-Briggs F. Problem solving interventions for diabetes self-management and control: a systemic review of the literature. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;100(2):145-161.

5. Stellefson M, Dipnarine K, Stopka C. The chronic care model and diabetes management in US primary care settings: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:120180.

6. Heisler M, Resnicow K. Helping patients make and sustain healthy changes: a brief introduction to motivational interviewing in clinical diabetes care. Clin Diabetes. 2008;26(4):161-165.

7. Williams GC, Rodin GC, Ryan RM, Grolnick WS, Deci EL. Autonomous regulation and long-term medication adherence in adult outpatients. Health Psychol. 1998;17(3):269-276.

8. Rosland AM, Piette JD, Choi HJ, Heisler M. Family and friend participation in primary care visits of patients with diabetes or heart failure: patient and physician determinants and experiences. Med Care. 2011;49(1):37-45.

9. Lafata JE, Morris HL, Dobie E, Heisler M, Werner RM, Dumenci L. Patient-reported use of collaborative goal setting and glycemic control among patients with diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):94-99.

10. Heisler M, Vijan S, Makki F, Piette JD. Diabetes control with reciprocal peer support versus nurse care management: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(8):507-515.

11. Collier IA, Baker DM. Implementation of a pharmacist-supervised outpatient diabetes treatment clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(1):27-36.

12. Kirsch S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(5):349-353.

13. Moen J, Antonov K, Nilsson JLF. Interaction between participants in focus groups with older patients and general practitioners. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(5):607-616.

14. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288.

15. Aujoulat I, Marcolongo R, Bonadiman L, Deccache A. Reconsidering patient empowerment in chronic illness: a critique of models of self-efficacy and bodily control. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(5):1228-1239.

16. Olshansky E, Sacco D, Fitzgerald K, et al. Living with diabetes: normalizing the process of managing diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(6):1004-1012.

17. Goldman JB, Maclean HM. The significance of identity in the adjustment to diabetes among insulin users. Diabetes Educ. 1998;24(6):741-748.