User login

Transient global amnesia: Psychiatric precipitants, features, and comorbidities

Ms. A, age 48, is a physician’s assistant with no psychiatric history. She presents to the emergency department (ED) with her partner and daughter due to a 15-minute episode of acute-onset memory loss and concern for stroke. In the ED, Ms. A is confused and repeatedly asks, “Where are we?” “How did we get here?” and “What day is it?” Her partner denies Ms. A has focal neurologic deficits or seizures.

Ms. A had only slept 4 hours the night before she came to the ED because she had just learned that her daughter works in the sex industry. According to her daughter, Ms. A was raped by a soldier many years ago. At that time, her perpetrator told Ms. A that he would kill her entire family if she ever told anyone. As a result, she never pursued any psychological or psychiatric treatment.

During the evaluation, Ms. A shares details regarding her social and medical history; however, she does not recall receiving bad news the night before. She asks the interviewer several times how she got to the hospital, and when a cranial nerve exam is performed, she states, “I am not the patient!”

Ms. A’s vital signs and physical exam are unremarkable. Urinalysis is significant for a ketones level of 20 mmol/L (reference range: negative for ketones), and a urine human chorionic gonadotropin test is negative. A neurologic exam does not identify any focal deficits. No imaging is performed.

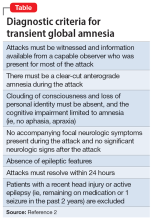

Transient global amnesia (TGA) describes an episode of anterograde, and possibly retrograde, amnesia that lasts up to 24 hours. On presentation, patients experiencing TGA repeatedly ask, “Where am I?” “What day is it?” and “How did I get here?” However, semantic memory—such as knowledge of the world and autobiographical information—is preserved.1 The first case of TGA was described in 1956, and its diagnostic criteria were most recently modified in 1990 (Table2).

Though TGA is the most common cause of acute-onset amnesia, it is rare, affecting approximately 3 to 10 individuals per 100,000. The average age of onset is 61 to 63, with most cases occurring after age 50. TGA is generally thought to affect males and females equally, though some studies suggest a female predominance.3 In most cases (approximately 90%), there is a precipitating event such as physical or emotional stress, change in temperature, or sexual intercourse.4

In this article, we provide an overview of the classification, presentation, differential diagnosis, workup, and treatment of TGA. While TGA is a neurologic diagnosis, in a subset of patients it can present with psychiatric features resembling conversion disorder. For such patients, we argue that TGA can be considered a neuropsychiatric condition (Box 15-12). This classification may empower emergency psychiatry clinicians and psychotherapists to identify and treat the condition, which is not described by the current psychiatric diagnostic system.

Box 1

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is a neurologic diagnosis. However, in 1956, Bender8 associated the clinical picture of TGA with psychogenic etiology, 2 years before the term was coined. The same year, Courjon et al9 classified TGA as a functional disorder.

As recent literature on TGA has focused on the neuropsychologic mechanism of memory loss, examination of the condition from a psychodynamic standpoint has fallen out of favor. In fact, the earliest discussions of the condition attributed the absence of TGA from literature prior to the 1950s “to erroneous classification of TGA as psychogenic or hysterical amnesia.”10 However, to refer to this condition as purely neurologic—and without any “psychogenic” or functional features— would be reductive.

In a 2019 case report, Espiridion et al6 considered TGA within the same diagnostic realm as—if not actually a form of—dissociative amnesia (DA). They published the case of a 60-year-old woman with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who experienced an episode of TGA that had manifested as anterograde and retrograde amnesia for 2 days and was precipitated by a psychotherapy session in which she discussed an individual who had assaulted her 5 years earlier. Much like in the case of Ms. A, the report from Espiridion et al6 clearly exemplifies a psychiatric etiology that shares similar context of a stressor unveiling a past memory too unbearable to maintain in consciousness. They concluded that “this case demonstrates anterograde and identity memory impairments likely induced by her PTSD. It is … possible that this presentation may be labeled PTSD-related dissociative amnesia.”6

Considering TGA as a type of DA within a subset of patients represents progression with regards to considering it as a psychiatric disorder. However, a prominent factor distinguishing TGA from DA is that the latter is more commonly associated with loss of personal identity.5 In TGA, memory of autobiographical information typically is preserved.7

Others have argued for a subtype of “emotional arousal–induced TGA”11 or “emotional TGA.”10 We suggest that this “emotional” subtype of TGA, which clearly was affecting Ms. A, shares similarities with functional neurologic symptom disorder, otherwise known as conversion disorder. The psychoanalytic concept that unconscious psychic distress can be “converted” into a neurologic problem is exemplified by Ms. A. Of note, being female and having an emotional stressor are risk factors for conversion disorder. Additionally, migraine— which was not part of Ms. A’s history—is also a risk factor for both TGA and conversion disorder.12 Despite these similarities, however, TGA’s neurophysiological changes on MRI and self-resolving nature still position the disorder as uniquely neuropsychiatric in the term’s purest sense.

Continue to: Differential diagnosis and workup

Differential diagnosis and workup

The differential diagnosis for acute-onset memory loss in the absence of other neurologic or psychiatric features is broad. It includes:

- dissociative amnesia

- ischemic amnesia

- transient epileptic amnesia

- toxic and metabolic amnesia

- posttraumatic amnesia.

Dissociative amnesia (DA), otherwise known as psychogenic amnesia, is “an inability to recall important autobiographical information, usually of a traumatic or stressful nature, that is inconsistent with ordinary forgetting.”13 According to this definition, DA features only retrograde amnesia, as opposed to TGA, which features anterograde amnesia, with possible retrograde amnesia. A subtype of DA—specifically, “continuous amnesia” or “anterograde dissociative amnesia”— is in DSM-5.13 However, the diagnostic criteria are unclear, and no cases have been identified in the literature since 1903, before TGA became a diagnostic entity.5,14 Moreover, patients with DA cannot recall autobiographical information, which is not a feature of TGA. Within DSM-5, TGA is an exclusion criterion for DA.13 Thus, an episode of anterograde amnesia with acute onset best meets criteria for TGA, even if there are substantial psychiatric risk factors.

Ischemic amnesia—including stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA)—is often the primary concern of patients with TGA and their families upon initial presentation, as was the case with Ms. A.6,15 TIA presenting with isolated, acute-onset amnesia would be highly unusual, because these attacks usually present with focal symptoms including motor deficits, sensory deficits, visual field deficits, and aphasia or dysarthria. A patient with amnesia experiencing a TIA would likely have symptoms lasting from seconds to minutes, which is much shorter than a typical TGA episode.16

Amnesia secondary to stroke may be transient or permanent.7 Amnesia is present in approximately 1% of all strokes and in approximately 19.3% of posterior cerebral artery strokes.7,17 Unlike TIA and TGA, ischemic amnesia would present with MRI findings detectable at symptom onset. TGA does reveal MRI findings, particularly punctate lesions in the CA1 area of the hippocampus; however, these lesions are typically much smaller than those found in stroke, and are not detectable until 12 to 48 hours after episode onset.1,17 MRI findings in ischemic amnesia are typically associated with extrahippocampal lesions.17 Finally, the presence of vascular risk factors such as hyperlipidemia, smoking, diabetes, and hypertension may also favor a diagnosis of stroke or TIA as opposed to TGA, which is not associated with these risk factors.18 Though ischemic amnesia and TGA usually can be differentiated based on history and presentation, MRI with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and diffusion-weighted imaging may be performed to definitively distinguish stroke from TGA.7

Transient epileptic amnesia (TEA), a focal form of epilepsy within the temporal lobe, should also be considered in patients who present with acute-onset amnesia. Like TGA, TEA may present with simultaneous anterograde and retrograde amnesia accompanied by repetitive questioning.19 Amnesia can be the sole symptom of TEA in up to 24% of cases. However, several key features distinguish TEA from TGA. TEA most often presents with other clinical signs of seizures, such as oral automatisms and/or olfactory hallucinations.20 There is also a significant difference in episode length; TEA episodes last an average of 30 to 60 minutes and tend to occur upon wakening, whereas TGA episodes last an average of 4 to 6 hours and do not preferentially occur at any particular time.1,21 In the interictal period—between seizures—patients with TEA may also experience accelerated long-term forgetting, autobiographical amnesia, and topographical amnesia.19,20 Finally, a diagnosis of TEA also requires recurrent episodes. Recurrence can happen with TGA, but is less frequent.21 Generally, history and presentation can distinguish TEA from TGA. Though there is no formal protocol for TEA workup, Lanzone et al21 recommend 24-hour EEG or EEG sleep monitoring in patients who present with amnesia as well as other clinical manifestations of epileptic phenomenon.

Continue to: Toxic and metabolic

Toxic and metabolic etiologies of amnesia include opioid and cocaine use, general anesthetics,22 and hypoglycemia.7,23 Toxic and metabolic causes of amnesia may mirror TGA in their acute onset as well as anterograde nature. However, these patients will likely present with fluctuating consciousness and/or other neuropsychiatric features, such as pressured speech, delusions, and/or distractability.23 Obtaining a patient’s medical history, including substance use, medication use, and the presence of diabetes,24 is typically sufficient to rule out toxic and metabolic causes.7

Posttraumatic amnesia (PTA) describes transient memory loss that occurs after a traumatic brain injury. Anterograde amnesia is most common, though approximately 20% of patients may also experience retrograde amnesia pertaining to the events near the date of their injury. Unlike TGA, which typically resolves within 24 hours, the recovery time of amnestic symptoms in PTA ranges from minutes to years.7 A distinguishing feature of PTA is the presence of confusion, which often resembles a state of delirium.25 The presentation of PTA can vary immensely with regards to agitation, psychotic symptoms, and the time to resolution of the amnesia. Though TGA can be distinguished from PTA based on a lack of clouding of consciousness, a case of anterograde amnesia warrants inquiry into a potential history of head injuries to rule out a traumatic cause.26

Box 21,3,23,27-33 outlines current theories of the etiology and pathogenesis of TGA.

Box 2

The etiology and pathogenesis of transient global amnesia (TGA) are poorly understood, and TGA remains one of the most enigmatic syndromes in clinical neurology.27 Theories regarding the pathogenesis of TGA are diverse and include vascular, epileptic, migraine, and stress-related etiologies.1,23

Early theories suggested arterial ischemia28 and epileptic phenomena29 as etiologies of TGA. The venous theory posits that TGA stems from jugular venous incompetency, causing venous flow and subsequent venous congestion in the medial temporal lobe, wherein lies the hippocampus. This theory is supported by several studies showing venous valve insufficiency as detected by ultrasonographic evaluation during the Valsalva maneuver in patients with TGA.30 This pathophysiologic mechanism may explain the occurrence of TGA in a specific cluster of cases, including men whose TGA episodes are precipitated by physical stress or the Valsalva maneuver.3 The migraine theory and stress theory share a similar proposed neurophysiologic mechanism.

The migraine theory stems from migraines being a known risk factor for TGA, particularly in middle-aged women.31 The stress theory is based on the known emotional precipitants and psychiatric comorbidities associated with TGA. Notably, both the migraine theory and stress theory implicate the role of excessive glutamate release as well as CNS depression.31,32 Glutamate targets the CA1 region of the hippocampus, which is involved in TGA and is known to have the highest density of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors among hippocampal regions.33

Given the heterogeneity of the demographics and stressors associated with TGA, multiple mechanisms for the disease process may coexist, leading to a similar clinical picture. In 2006, Quinette et al3 performed a multivariate analysis of variables associated with TGA, including age, sex, medical history, and presentation. They demonstrated 3 “clusters” of TGA pictures: women with anxiety or a personality disorder; men with physical precipitating events; and younger patients (age <56) with a history of migraine. These findings suggest TGA may have unique precipitants corresponding to multiple neurophysiologic mechanisms.

Transient global ischemia: Psychiatric features

Several studies have demonstrated psychiatric precipitants, features, and comorbidities associated with TGA. Of the TGA cases associated with precipitating events, 29% to 50% are associated with an emotional stressor.3,4 Examples of emotional stressors include a quarrel,4 the announcement of a birth or suicide, and a nightmare.15 For Ms. A, learning her daughter worked in the sex industry was an emotional stressor.2

During its acute phase, TGA has been shown to present with mood and anxiety symptoms.34 Moreover, during episodes, patients often demonstrate features of panic attacks, such as dizziness, fainting, choking, palpitations, and paresthesia.3,35

Continue to: Finally, patients with TGA...

Finally, patients with TGA are more likely to have psychiatric comorbidities than those without the condition. In a study of 25 patients who experienced TGA triggered by a precipitant, Inzitari et al4 found a strong association of TGA with phobic personality traits, including agoraphobia and simple phobic attitudes (ie, fear of traveling far from home or the sight of blood). Pantoni et al35 replicated these results in 2005 and found that in comparison to patients with TIA, patients with TGA are more likely to have personal and family histories of psychiatric disease. A 2014 study by Dohring et al36 found that compared to healthy controls, patients with TGA are more likely to have maladaptive coping strategies and stress responses. Patients with TGA tended to exhibit increased feelings of guilt, take more medication, and exhibit more anxiety compared to healthy controls.36

Treatment: Benzodiazepines

There are no published treatment guidelines for TGA. However, in case reports, benzodiazepines (specifically lorazepam37) have been shown to have utility in diagnosing and treating DA. The success of benzodiazepines is attributed to its gamma-aminobutyric acid mechanism, which involves inhibiting activity of the N-methyl-

However, the benzodiazepine midazolam has been identified as a precipitant of TGA. In a case report, Rinehart et al22 identified flumazenil—a benzodiazepine antagonist used primarily to treat retrograde postoperative amnesia—as an antidote. The potentially paradoxical role of benzodiazepines in both the precipitation and treatment of TGA may relate back to the heterogeneity of the etiologies of TGA. Further research comparing the treatment of TGA in patients with stress-induced TGA vs postoperative TGA is needed to better understand the neurochemical basis of TGA and work toward establishing optimal treatment options for different patient demographics.

A generally favorable prognosis

TGA carries a low risk of recurrence. In studies with 3- to 7-year follow-up periods, the recurrence rates ranged from 1.4% to 23.8%.23,35,38

Memory impairments may be present for 5 to 6 months following a TGA episode. The severity of these impairments may range from clinically unnoticeable to the patient meeting the criteria for mild cognitive impairment.23,39 The risk is higher in patients who have had recurrent TGA compared to those patients who have experienced only a single episode.23

Continue to: TGA does not increase...

TGA does not increase the risk of cerebrovascular events. There is controversy regarding a potentially increased risk for dementia as well as epilepsy, though there is insufficient evidence to support these findings.23,40

CASE CONTINUED

Five hours after the onset of Ms. A’s symptoms, the treatment team initiates oral lorazepam 1 mg. One hour after taking lorazepam, Ms. A’s anterograde and retrograde amnesia improve. She cannot recall why she was brought to the hospital but does remember the date and location, which she was not able to do on initial presentation. She feels safe, states a clear plan for self-care, and is discharged in the care of her partner. Though Ms. A’s memory improved soon after she received lorazepam, this improvement also could be attributed to the natural course of time, as TGA tends to resolve on its own within 24 hours.

Bottom Line

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is an episode of anterograde, and possibly retrograde, amnesia that lasts up to 24 hours. It represents an interesting diagnosis at the intersection of psychiatry and neurology. TGA has many established psychiatric risk factors and features—some of which may resemble conversion disorder—but these may only apply to a particular subset of patients, which reflects the heterogeneity of the condition.

Related Resources

- Sparaco M, Pascarella R, Muccio CF, et al. Forgetting the unforgettable: transient global amnesia part I: pathophysiology and etiology. J Clin Med. 2022;11(12): 3373. doi:10.3390/jcm1112337

- Sparaco M, Pascarella R, Muccio CF, et al. Forgetting the unforgettable: transient global amnesia part II: a clinical road map. J Clin Med. 2022;11(14):3940. doi:10.3390/ jcm11143940

Drug Brand Names

Flumazenil • Romazicon

Lorazepam • Ativan

Midazolam • Versed

1. Miller TD, Butler CR. Acute-onset amnesia: transient global amnesia and other causes. Pract Neurol. 2022;22(3):201-208. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2020-002826

2. Hodges JR, Warlow CP. Syndromes of transient amnesia: towards a classification. A study of 153 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53(10):834-843. doi:10.1136/jnnp.53.10.834

3. Quinette P, Guillery-Girard B, Dayan J, et al. What does transient global amnesia really mean? Review of the literature and thorough study of 142 cases. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 7):1640-1658. doi:10.1093/brain/awl105

4. Inzitari D, Pantoni L, Lamassa M, et al. Emotional arousal and phobia in transient global amnesia. Arch Neurol. 1997;54(7):866-873. doi:10.1001/archneur.1997.00550190056015

5. Staniloiu A, Markowitsch HJ. Dissociative amnesia. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(3):226-241. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70279-2

6. Espiridion ED, Gupta J, Bshara A, et al. Transient global amnesia in a 60-year-old female with post-traumatic stress disorder. Cureus. 2019;11(9):e5792. doi:10.7759/cureus.5792

7. Alessandro L, Ricciardi M, Chaves H, et al. Acute amnestic syndromes. J Neurol Sci. 2020;413:116781. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2020.116781

8. Bender M. Syndrome of isolated episode of confusion with amnesia. J Hillside Hosp. 1956;5:212-215.

9. Courjon J, Guyotat J. Les ictus amnéstiques [Amnesic strokes]. J Med Lyon. 1956;37(882):697-701.

10. Noel A, Quinette P, Hainselin M, et al. The still enigmatic syndrome of transient global amnesia: interactions between neurological and psychopathological factors. Neuropsychol Rev. 2015;25(2):125-133. doi:10.1007/s11065-015-9284-y

11. Merriam AE, Wyszynski B, Betzler T. Emotional arousal-induced transient global amnesia. A clue to the neural transcription of emotion? Psychosomatics. 1992;33(1):109-113. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(92)72029-5

12. Hallett M, Aybek S, Dworetzky BA, et al. Functional neurological disorder: new subtypes and shared mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(6):537-550. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00422-1

13. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

14. Bourdon B, Dide M. A case of continuous amnesia with tactile asymbolia, complicated by other troubles. Ann Psychol. 1903;10:84-115.

15. Marinella MA. Transient global amnesia and a father’s worst nightmare. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(8):843-844. doi:10.1056/NEJM200402193500821

16. Amarenco P. Transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1933-1941. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1908837

17. Szabo K, Forster A, Jager T, et al. Hippocampal lesion patterns in acute posterior cerebral artery stroke: clinical and MRI findings. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2042-2045. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.536144

18. Liampas I, Raptopoulou M, Siokas V, et al. Conventional cardiovascular risk factors in transient global amnesia: systematic review and proposition of a novel hypothesis. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2021;61:100909. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2021.100909

19. Zeman A, Butler C. Transient epileptic amnesia. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23(6):610-616. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834027db

20. Baker J, Savage S, Milton F, et al. The syndrome of transient epileptic amnesia: a combined series of 115 cases and literature review. Brain Commun. 2021;3(2):fcab038. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcab038

21. Lanzone J, Ricci L, Assenza G, et al Transient epileptic and global amnesia: real-life differential diagnosis. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;88:205-211. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.07.015

22. Rinehart JB, Baker B, Raphael D. Postoperative global amnesia reversed with flumazenil. Neurologist. 2012;18(4):216-218. doi:10.1097/NRL.0b013e31825bbef4

23. Arena JE, Rabinstein AA. Transient global amnesia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(2):264-272. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.001

24. Holemans X, Dupuis M, Misson N, et al. Reversible amnesia in a type 1 diabetic patient and bilateral hippocampal lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Diabet Med. 2001;18(9):761-763. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00481.x

25. Marshman LAG, Jakabek D, Hennessy M, et al. Post-traumatic amnesia. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(11):1475-1481. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2012.11.022

26. Parker TD, Rees R, Rajagopal S, et al. Post-traumatic amnesia. Pract Neurol. 2022;22(2):129-137. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2021-003056

27. You SH, Kim B, Kim BK. Transient global amnesia: signal alteration in 2D/3D T2-FLAIR sequences. Clin Imaging. 2021;78:154-159. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.03.029

28. Mathew NT, Meyer JS. Pathogenesis and natural history of transient global amnesia. Stroke. 1974;5(3):303-311. doi:10.1161/01.str.5.3.303

29. Fisher CM, Adams RD. Transient global amnesia. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1964;40(SUPPL 9):1-83.

30. Cejas C, Cisneros LF, Lagos R, et al. Internal jugular vein valve incompetence is highly prevalent in transient global amnesia. Stroke. 2010;41(1):67-71. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.566315

31. Liampas I, Siouras AS, Siokas V, et al. Migraine in transient global amnesia: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Neurol. 2022;269(1):184-196. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-10363-y

32. Ding X, Peng D. Transient global amnesia: an electrophysiological disorder based on cortical spreading depression-transient global amnesia model. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:602496. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2020.602496

33. Bartsch T, Dohring J, Reuter S, et al. Selective neuronal vulnerability of human hippocampal CA1 neurons: lesion evolution, temporal course, and pattern of hippocampal damage in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35(11):1836-1845. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2015.137

34. Noel A, Quinette P, Guillery-Girard B, et al. Psychopathological factors, memory disorders and transient global amnesia. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(2):145-151. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045716

35. Pantoni L, Bertini E, Lamassa M, et al. Clinical features, risk factors, and prognosis in transient global amnesia: a follow-up study. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12(5):350-356. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00982.x

36. Dohring J, Schmuck A, Bartsch T. Stress-related factors in the emergence of transient global amnesia with hippocampal lesions. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:287. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00287

37. Jiang S, Gunther S, Hartney K, et al. An intravenous lorazepam infusion for dissociative amnesia: a case report. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(6):814-818. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2020.01.009

38. He S, Ye Z, Yang Q, et al. Transient global amnesia: risk factors, imaging features, and prognosis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:1611-1619. doi:10.2147/NDT.S299168

39. Borroni B, Agosti C, Brambilla C, et al. Is transient global amnesia a risk factor for amnestic mild cognitive impairment? J Neurol. 2004;251(9):1125-1127. doi:10.1007/s00415-004-0497-x

40. Liampas I, Raptopoulou M, Siokas V, et al. The long-term prognosis of transient global amnesia: a systematic review. Rev Neurosci. 2021;32(5):531-543. doi:10.1515/revneuro-2020-0110

Ms. A, age 48, is a physician’s assistant with no psychiatric history. She presents to the emergency department (ED) with her partner and daughter due to a 15-minute episode of acute-onset memory loss and concern for stroke. In the ED, Ms. A is confused and repeatedly asks, “Where are we?” “How did we get here?” and “What day is it?” Her partner denies Ms. A has focal neurologic deficits or seizures.

Ms. A had only slept 4 hours the night before she came to the ED because she had just learned that her daughter works in the sex industry. According to her daughter, Ms. A was raped by a soldier many years ago. At that time, her perpetrator told Ms. A that he would kill her entire family if she ever told anyone. As a result, she never pursued any psychological or psychiatric treatment.

During the evaluation, Ms. A shares details regarding her social and medical history; however, she does not recall receiving bad news the night before. She asks the interviewer several times how she got to the hospital, and when a cranial nerve exam is performed, she states, “I am not the patient!”

Ms. A’s vital signs and physical exam are unremarkable. Urinalysis is significant for a ketones level of 20 mmol/L (reference range: negative for ketones), and a urine human chorionic gonadotropin test is negative. A neurologic exam does not identify any focal deficits. No imaging is performed.

Transient global amnesia (TGA) describes an episode of anterograde, and possibly retrograde, amnesia that lasts up to 24 hours. On presentation, patients experiencing TGA repeatedly ask, “Where am I?” “What day is it?” and “How did I get here?” However, semantic memory—such as knowledge of the world and autobiographical information—is preserved.1 The first case of TGA was described in 1956, and its diagnostic criteria were most recently modified in 1990 (Table2).

Though TGA is the most common cause of acute-onset amnesia, it is rare, affecting approximately 3 to 10 individuals per 100,000. The average age of onset is 61 to 63, with most cases occurring after age 50. TGA is generally thought to affect males and females equally, though some studies suggest a female predominance.3 In most cases (approximately 90%), there is a precipitating event such as physical or emotional stress, change in temperature, or sexual intercourse.4

In this article, we provide an overview of the classification, presentation, differential diagnosis, workup, and treatment of TGA. While TGA is a neurologic diagnosis, in a subset of patients it can present with psychiatric features resembling conversion disorder. For such patients, we argue that TGA can be considered a neuropsychiatric condition (Box 15-12). This classification may empower emergency psychiatry clinicians and psychotherapists to identify and treat the condition, which is not described by the current psychiatric diagnostic system.

Box 1

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is a neurologic diagnosis. However, in 1956, Bender8 associated the clinical picture of TGA with psychogenic etiology, 2 years before the term was coined. The same year, Courjon et al9 classified TGA as a functional disorder.

As recent literature on TGA has focused on the neuropsychologic mechanism of memory loss, examination of the condition from a psychodynamic standpoint has fallen out of favor. In fact, the earliest discussions of the condition attributed the absence of TGA from literature prior to the 1950s “to erroneous classification of TGA as psychogenic or hysterical amnesia.”10 However, to refer to this condition as purely neurologic—and without any “psychogenic” or functional features— would be reductive.

In a 2019 case report, Espiridion et al6 considered TGA within the same diagnostic realm as—if not actually a form of—dissociative amnesia (DA). They published the case of a 60-year-old woman with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who experienced an episode of TGA that had manifested as anterograde and retrograde amnesia for 2 days and was precipitated by a psychotherapy session in which she discussed an individual who had assaulted her 5 years earlier. Much like in the case of Ms. A, the report from Espiridion et al6 clearly exemplifies a psychiatric etiology that shares similar context of a stressor unveiling a past memory too unbearable to maintain in consciousness. They concluded that “this case demonstrates anterograde and identity memory impairments likely induced by her PTSD. It is … possible that this presentation may be labeled PTSD-related dissociative amnesia.”6

Considering TGA as a type of DA within a subset of patients represents progression with regards to considering it as a psychiatric disorder. However, a prominent factor distinguishing TGA from DA is that the latter is more commonly associated with loss of personal identity.5 In TGA, memory of autobiographical information typically is preserved.7

Others have argued for a subtype of “emotional arousal–induced TGA”11 or “emotional TGA.”10 We suggest that this “emotional” subtype of TGA, which clearly was affecting Ms. A, shares similarities with functional neurologic symptom disorder, otherwise known as conversion disorder. The psychoanalytic concept that unconscious psychic distress can be “converted” into a neurologic problem is exemplified by Ms. A. Of note, being female and having an emotional stressor are risk factors for conversion disorder. Additionally, migraine— which was not part of Ms. A’s history—is also a risk factor for both TGA and conversion disorder.12 Despite these similarities, however, TGA’s neurophysiological changes on MRI and self-resolving nature still position the disorder as uniquely neuropsychiatric in the term’s purest sense.

Continue to: Differential diagnosis and workup

Differential diagnosis and workup

The differential diagnosis for acute-onset memory loss in the absence of other neurologic or psychiatric features is broad. It includes:

- dissociative amnesia

- ischemic amnesia

- transient epileptic amnesia

- toxic and metabolic amnesia

- posttraumatic amnesia.

Dissociative amnesia (DA), otherwise known as psychogenic amnesia, is “an inability to recall important autobiographical information, usually of a traumatic or stressful nature, that is inconsistent with ordinary forgetting.”13 According to this definition, DA features only retrograde amnesia, as opposed to TGA, which features anterograde amnesia, with possible retrograde amnesia. A subtype of DA—specifically, “continuous amnesia” or “anterograde dissociative amnesia”— is in DSM-5.13 However, the diagnostic criteria are unclear, and no cases have been identified in the literature since 1903, before TGA became a diagnostic entity.5,14 Moreover, patients with DA cannot recall autobiographical information, which is not a feature of TGA. Within DSM-5, TGA is an exclusion criterion for DA.13 Thus, an episode of anterograde amnesia with acute onset best meets criteria for TGA, even if there are substantial psychiatric risk factors.

Ischemic amnesia—including stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA)—is often the primary concern of patients with TGA and their families upon initial presentation, as was the case with Ms. A.6,15 TIA presenting with isolated, acute-onset amnesia would be highly unusual, because these attacks usually present with focal symptoms including motor deficits, sensory deficits, visual field deficits, and aphasia or dysarthria. A patient with amnesia experiencing a TIA would likely have symptoms lasting from seconds to minutes, which is much shorter than a typical TGA episode.16

Amnesia secondary to stroke may be transient or permanent.7 Amnesia is present in approximately 1% of all strokes and in approximately 19.3% of posterior cerebral artery strokes.7,17 Unlike TIA and TGA, ischemic amnesia would present with MRI findings detectable at symptom onset. TGA does reveal MRI findings, particularly punctate lesions in the CA1 area of the hippocampus; however, these lesions are typically much smaller than those found in stroke, and are not detectable until 12 to 48 hours after episode onset.1,17 MRI findings in ischemic amnesia are typically associated with extrahippocampal lesions.17 Finally, the presence of vascular risk factors such as hyperlipidemia, smoking, diabetes, and hypertension may also favor a diagnosis of stroke or TIA as opposed to TGA, which is not associated with these risk factors.18 Though ischemic amnesia and TGA usually can be differentiated based on history and presentation, MRI with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and diffusion-weighted imaging may be performed to definitively distinguish stroke from TGA.7

Transient epileptic amnesia (TEA), a focal form of epilepsy within the temporal lobe, should also be considered in patients who present with acute-onset amnesia. Like TGA, TEA may present with simultaneous anterograde and retrograde amnesia accompanied by repetitive questioning.19 Amnesia can be the sole symptom of TEA in up to 24% of cases. However, several key features distinguish TEA from TGA. TEA most often presents with other clinical signs of seizures, such as oral automatisms and/or olfactory hallucinations.20 There is also a significant difference in episode length; TEA episodes last an average of 30 to 60 minutes and tend to occur upon wakening, whereas TGA episodes last an average of 4 to 6 hours and do not preferentially occur at any particular time.1,21 In the interictal period—between seizures—patients with TEA may also experience accelerated long-term forgetting, autobiographical amnesia, and topographical amnesia.19,20 Finally, a diagnosis of TEA also requires recurrent episodes. Recurrence can happen with TGA, but is less frequent.21 Generally, history and presentation can distinguish TEA from TGA. Though there is no formal protocol for TEA workup, Lanzone et al21 recommend 24-hour EEG or EEG sleep monitoring in patients who present with amnesia as well as other clinical manifestations of epileptic phenomenon.

Continue to: Toxic and metabolic

Toxic and metabolic etiologies of amnesia include opioid and cocaine use, general anesthetics,22 and hypoglycemia.7,23 Toxic and metabolic causes of amnesia may mirror TGA in their acute onset as well as anterograde nature. However, these patients will likely present with fluctuating consciousness and/or other neuropsychiatric features, such as pressured speech, delusions, and/or distractability.23 Obtaining a patient’s medical history, including substance use, medication use, and the presence of diabetes,24 is typically sufficient to rule out toxic and metabolic causes.7

Posttraumatic amnesia (PTA) describes transient memory loss that occurs after a traumatic brain injury. Anterograde amnesia is most common, though approximately 20% of patients may also experience retrograde amnesia pertaining to the events near the date of their injury. Unlike TGA, which typically resolves within 24 hours, the recovery time of amnestic symptoms in PTA ranges from minutes to years.7 A distinguishing feature of PTA is the presence of confusion, which often resembles a state of delirium.25 The presentation of PTA can vary immensely with regards to agitation, psychotic symptoms, and the time to resolution of the amnesia. Though TGA can be distinguished from PTA based on a lack of clouding of consciousness, a case of anterograde amnesia warrants inquiry into a potential history of head injuries to rule out a traumatic cause.26

Box 21,3,23,27-33 outlines current theories of the etiology and pathogenesis of TGA.

Box 2

The etiology and pathogenesis of transient global amnesia (TGA) are poorly understood, and TGA remains one of the most enigmatic syndromes in clinical neurology.27 Theories regarding the pathogenesis of TGA are diverse and include vascular, epileptic, migraine, and stress-related etiologies.1,23

Early theories suggested arterial ischemia28 and epileptic phenomena29 as etiologies of TGA. The venous theory posits that TGA stems from jugular venous incompetency, causing venous flow and subsequent venous congestion in the medial temporal lobe, wherein lies the hippocampus. This theory is supported by several studies showing venous valve insufficiency as detected by ultrasonographic evaluation during the Valsalva maneuver in patients with TGA.30 This pathophysiologic mechanism may explain the occurrence of TGA in a specific cluster of cases, including men whose TGA episodes are precipitated by physical stress or the Valsalva maneuver.3 The migraine theory and stress theory share a similar proposed neurophysiologic mechanism.

The migraine theory stems from migraines being a known risk factor for TGA, particularly in middle-aged women.31 The stress theory is based on the known emotional precipitants and psychiatric comorbidities associated with TGA. Notably, both the migraine theory and stress theory implicate the role of excessive glutamate release as well as CNS depression.31,32 Glutamate targets the CA1 region of the hippocampus, which is involved in TGA and is known to have the highest density of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors among hippocampal regions.33

Given the heterogeneity of the demographics and stressors associated with TGA, multiple mechanisms for the disease process may coexist, leading to a similar clinical picture. In 2006, Quinette et al3 performed a multivariate analysis of variables associated with TGA, including age, sex, medical history, and presentation. They demonstrated 3 “clusters” of TGA pictures: women with anxiety or a personality disorder; men with physical precipitating events; and younger patients (age <56) with a history of migraine. These findings suggest TGA may have unique precipitants corresponding to multiple neurophysiologic mechanisms.

Transient global ischemia: Psychiatric features

Several studies have demonstrated psychiatric precipitants, features, and comorbidities associated with TGA. Of the TGA cases associated with precipitating events, 29% to 50% are associated with an emotional stressor.3,4 Examples of emotional stressors include a quarrel,4 the announcement of a birth or suicide, and a nightmare.15 For Ms. A, learning her daughter worked in the sex industry was an emotional stressor.2

During its acute phase, TGA has been shown to present with mood and anxiety symptoms.34 Moreover, during episodes, patients often demonstrate features of panic attacks, such as dizziness, fainting, choking, palpitations, and paresthesia.3,35

Continue to: Finally, patients with TGA...

Finally, patients with TGA are more likely to have psychiatric comorbidities than those without the condition. In a study of 25 patients who experienced TGA triggered by a precipitant, Inzitari et al4 found a strong association of TGA with phobic personality traits, including agoraphobia and simple phobic attitudes (ie, fear of traveling far from home or the sight of blood). Pantoni et al35 replicated these results in 2005 and found that in comparison to patients with TIA, patients with TGA are more likely to have personal and family histories of psychiatric disease. A 2014 study by Dohring et al36 found that compared to healthy controls, patients with TGA are more likely to have maladaptive coping strategies and stress responses. Patients with TGA tended to exhibit increased feelings of guilt, take more medication, and exhibit more anxiety compared to healthy controls.36

Treatment: Benzodiazepines

There are no published treatment guidelines for TGA. However, in case reports, benzodiazepines (specifically lorazepam37) have been shown to have utility in diagnosing and treating DA. The success of benzodiazepines is attributed to its gamma-aminobutyric acid mechanism, which involves inhibiting activity of the N-methyl-

However, the benzodiazepine midazolam has been identified as a precipitant of TGA. In a case report, Rinehart et al22 identified flumazenil—a benzodiazepine antagonist used primarily to treat retrograde postoperative amnesia—as an antidote. The potentially paradoxical role of benzodiazepines in both the precipitation and treatment of TGA may relate back to the heterogeneity of the etiologies of TGA. Further research comparing the treatment of TGA in patients with stress-induced TGA vs postoperative TGA is needed to better understand the neurochemical basis of TGA and work toward establishing optimal treatment options for different patient demographics.

A generally favorable prognosis

TGA carries a low risk of recurrence. In studies with 3- to 7-year follow-up periods, the recurrence rates ranged from 1.4% to 23.8%.23,35,38

Memory impairments may be present for 5 to 6 months following a TGA episode. The severity of these impairments may range from clinically unnoticeable to the patient meeting the criteria for mild cognitive impairment.23,39 The risk is higher in patients who have had recurrent TGA compared to those patients who have experienced only a single episode.23

Continue to: TGA does not increase...

TGA does not increase the risk of cerebrovascular events. There is controversy regarding a potentially increased risk for dementia as well as epilepsy, though there is insufficient evidence to support these findings.23,40

CASE CONTINUED

Five hours after the onset of Ms. A’s symptoms, the treatment team initiates oral lorazepam 1 mg. One hour after taking lorazepam, Ms. A’s anterograde and retrograde amnesia improve. She cannot recall why she was brought to the hospital but does remember the date and location, which she was not able to do on initial presentation. She feels safe, states a clear plan for self-care, and is discharged in the care of her partner. Though Ms. A’s memory improved soon after she received lorazepam, this improvement also could be attributed to the natural course of time, as TGA tends to resolve on its own within 24 hours.

Bottom Line

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is an episode of anterograde, and possibly retrograde, amnesia that lasts up to 24 hours. It represents an interesting diagnosis at the intersection of psychiatry and neurology. TGA has many established psychiatric risk factors and features—some of which may resemble conversion disorder—but these may only apply to a particular subset of patients, which reflects the heterogeneity of the condition.

Related Resources

- Sparaco M, Pascarella R, Muccio CF, et al. Forgetting the unforgettable: transient global amnesia part I: pathophysiology and etiology. J Clin Med. 2022;11(12): 3373. doi:10.3390/jcm1112337

- Sparaco M, Pascarella R, Muccio CF, et al. Forgetting the unforgettable: transient global amnesia part II: a clinical road map. J Clin Med. 2022;11(14):3940. doi:10.3390/ jcm11143940

Drug Brand Names

Flumazenil • Romazicon

Lorazepam • Ativan

Midazolam • Versed

Ms. A, age 48, is a physician’s assistant with no psychiatric history. She presents to the emergency department (ED) with her partner and daughter due to a 15-minute episode of acute-onset memory loss and concern for stroke. In the ED, Ms. A is confused and repeatedly asks, “Where are we?” “How did we get here?” and “What day is it?” Her partner denies Ms. A has focal neurologic deficits or seizures.

Ms. A had only slept 4 hours the night before she came to the ED because she had just learned that her daughter works in the sex industry. According to her daughter, Ms. A was raped by a soldier many years ago. At that time, her perpetrator told Ms. A that he would kill her entire family if she ever told anyone. As a result, she never pursued any psychological or psychiatric treatment.

During the evaluation, Ms. A shares details regarding her social and medical history; however, she does not recall receiving bad news the night before. She asks the interviewer several times how she got to the hospital, and when a cranial nerve exam is performed, she states, “I am not the patient!”

Ms. A’s vital signs and physical exam are unremarkable. Urinalysis is significant for a ketones level of 20 mmol/L (reference range: negative for ketones), and a urine human chorionic gonadotropin test is negative. A neurologic exam does not identify any focal deficits. No imaging is performed.

Transient global amnesia (TGA) describes an episode of anterograde, and possibly retrograde, amnesia that lasts up to 24 hours. On presentation, patients experiencing TGA repeatedly ask, “Where am I?” “What day is it?” and “How did I get here?” However, semantic memory—such as knowledge of the world and autobiographical information—is preserved.1 The first case of TGA was described in 1956, and its diagnostic criteria were most recently modified in 1990 (Table2).

Though TGA is the most common cause of acute-onset amnesia, it is rare, affecting approximately 3 to 10 individuals per 100,000. The average age of onset is 61 to 63, with most cases occurring after age 50. TGA is generally thought to affect males and females equally, though some studies suggest a female predominance.3 In most cases (approximately 90%), there is a precipitating event such as physical or emotional stress, change in temperature, or sexual intercourse.4

In this article, we provide an overview of the classification, presentation, differential diagnosis, workup, and treatment of TGA. While TGA is a neurologic diagnosis, in a subset of patients it can present with psychiatric features resembling conversion disorder. For such patients, we argue that TGA can be considered a neuropsychiatric condition (Box 15-12). This classification may empower emergency psychiatry clinicians and psychotherapists to identify and treat the condition, which is not described by the current psychiatric diagnostic system.

Box 1

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is a neurologic diagnosis. However, in 1956, Bender8 associated the clinical picture of TGA with psychogenic etiology, 2 years before the term was coined. The same year, Courjon et al9 classified TGA as a functional disorder.

As recent literature on TGA has focused on the neuropsychologic mechanism of memory loss, examination of the condition from a psychodynamic standpoint has fallen out of favor. In fact, the earliest discussions of the condition attributed the absence of TGA from literature prior to the 1950s “to erroneous classification of TGA as psychogenic or hysterical amnesia.”10 However, to refer to this condition as purely neurologic—and without any “psychogenic” or functional features— would be reductive.

In a 2019 case report, Espiridion et al6 considered TGA within the same diagnostic realm as—if not actually a form of—dissociative amnesia (DA). They published the case of a 60-year-old woman with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who experienced an episode of TGA that had manifested as anterograde and retrograde amnesia for 2 days and was precipitated by a psychotherapy session in which she discussed an individual who had assaulted her 5 years earlier. Much like in the case of Ms. A, the report from Espiridion et al6 clearly exemplifies a psychiatric etiology that shares similar context of a stressor unveiling a past memory too unbearable to maintain in consciousness. They concluded that “this case demonstrates anterograde and identity memory impairments likely induced by her PTSD. It is … possible that this presentation may be labeled PTSD-related dissociative amnesia.”6

Considering TGA as a type of DA within a subset of patients represents progression with regards to considering it as a psychiatric disorder. However, a prominent factor distinguishing TGA from DA is that the latter is more commonly associated with loss of personal identity.5 In TGA, memory of autobiographical information typically is preserved.7

Others have argued for a subtype of “emotional arousal–induced TGA”11 or “emotional TGA.”10 We suggest that this “emotional” subtype of TGA, which clearly was affecting Ms. A, shares similarities with functional neurologic symptom disorder, otherwise known as conversion disorder. The psychoanalytic concept that unconscious psychic distress can be “converted” into a neurologic problem is exemplified by Ms. A. Of note, being female and having an emotional stressor are risk factors for conversion disorder. Additionally, migraine— which was not part of Ms. A’s history—is also a risk factor for both TGA and conversion disorder.12 Despite these similarities, however, TGA’s neurophysiological changes on MRI and self-resolving nature still position the disorder as uniquely neuropsychiatric in the term’s purest sense.

Continue to: Differential diagnosis and workup

Differential diagnosis and workup

The differential diagnosis for acute-onset memory loss in the absence of other neurologic or psychiatric features is broad. It includes:

- dissociative amnesia

- ischemic amnesia

- transient epileptic amnesia

- toxic and metabolic amnesia

- posttraumatic amnesia.

Dissociative amnesia (DA), otherwise known as psychogenic amnesia, is “an inability to recall important autobiographical information, usually of a traumatic or stressful nature, that is inconsistent with ordinary forgetting.”13 According to this definition, DA features only retrograde amnesia, as opposed to TGA, which features anterograde amnesia, with possible retrograde amnesia. A subtype of DA—specifically, “continuous amnesia” or “anterograde dissociative amnesia”— is in DSM-5.13 However, the diagnostic criteria are unclear, and no cases have been identified in the literature since 1903, before TGA became a diagnostic entity.5,14 Moreover, patients with DA cannot recall autobiographical information, which is not a feature of TGA. Within DSM-5, TGA is an exclusion criterion for DA.13 Thus, an episode of anterograde amnesia with acute onset best meets criteria for TGA, even if there are substantial psychiatric risk factors.

Ischemic amnesia—including stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA)—is often the primary concern of patients with TGA and their families upon initial presentation, as was the case with Ms. A.6,15 TIA presenting with isolated, acute-onset amnesia would be highly unusual, because these attacks usually present with focal symptoms including motor deficits, sensory deficits, visual field deficits, and aphasia or dysarthria. A patient with amnesia experiencing a TIA would likely have symptoms lasting from seconds to minutes, which is much shorter than a typical TGA episode.16

Amnesia secondary to stroke may be transient or permanent.7 Amnesia is present in approximately 1% of all strokes and in approximately 19.3% of posterior cerebral artery strokes.7,17 Unlike TIA and TGA, ischemic amnesia would present with MRI findings detectable at symptom onset. TGA does reveal MRI findings, particularly punctate lesions in the CA1 area of the hippocampus; however, these lesions are typically much smaller than those found in stroke, and are not detectable until 12 to 48 hours after episode onset.1,17 MRI findings in ischemic amnesia are typically associated with extrahippocampal lesions.17 Finally, the presence of vascular risk factors such as hyperlipidemia, smoking, diabetes, and hypertension may also favor a diagnosis of stroke or TIA as opposed to TGA, which is not associated with these risk factors.18 Though ischemic amnesia and TGA usually can be differentiated based on history and presentation, MRI with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and diffusion-weighted imaging may be performed to definitively distinguish stroke from TGA.7

Transient epileptic amnesia (TEA), a focal form of epilepsy within the temporal lobe, should also be considered in patients who present with acute-onset amnesia. Like TGA, TEA may present with simultaneous anterograde and retrograde amnesia accompanied by repetitive questioning.19 Amnesia can be the sole symptom of TEA in up to 24% of cases. However, several key features distinguish TEA from TGA. TEA most often presents with other clinical signs of seizures, such as oral automatisms and/or olfactory hallucinations.20 There is also a significant difference in episode length; TEA episodes last an average of 30 to 60 minutes and tend to occur upon wakening, whereas TGA episodes last an average of 4 to 6 hours and do not preferentially occur at any particular time.1,21 In the interictal period—between seizures—patients with TEA may also experience accelerated long-term forgetting, autobiographical amnesia, and topographical amnesia.19,20 Finally, a diagnosis of TEA also requires recurrent episodes. Recurrence can happen with TGA, but is less frequent.21 Generally, history and presentation can distinguish TEA from TGA. Though there is no formal protocol for TEA workup, Lanzone et al21 recommend 24-hour EEG or EEG sleep monitoring in patients who present with amnesia as well as other clinical manifestations of epileptic phenomenon.

Continue to: Toxic and metabolic

Toxic and metabolic etiologies of amnesia include opioid and cocaine use, general anesthetics,22 and hypoglycemia.7,23 Toxic and metabolic causes of amnesia may mirror TGA in their acute onset as well as anterograde nature. However, these patients will likely present with fluctuating consciousness and/or other neuropsychiatric features, such as pressured speech, delusions, and/or distractability.23 Obtaining a patient’s medical history, including substance use, medication use, and the presence of diabetes,24 is typically sufficient to rule out toxic and metabolic causes.7

Posttraumatic amnesia (PTA) describes transient memory loss that occurs after a traumatic brain injury. Anterograde amnesia is most common, though approximately 20% of patients may also experience retrograde amnesia pertaining to the events near the date of their injury. Unlike TGA, which typically resolves within 24 hours, the recovery time of amnestic symptoms in PTA ranges from minutes to years.7 A distinguishing feature of PTA is the presence of confusion, which often resembles a state of delirium.25 The presentation of PTA can vary immensely with regards to agitation, psychotic symptoms, and the time to resolution of the amnesia. Though TGA can be distinguished from PTA based on a lack of clouding of consciousness, a case of anterograde amnesia warrants inquiry into a potential history of head injuries to rule out a traumatic cause.26

Box 21,3,23,27-33 outlines current theories of the etiology and pathogenesis of TGA.

Box 2

The etiology and pathogenesis of transient global amnesia (TGA) are poorly understood, and TGA remains one of the most enigmatic syndromes in clinical neurology.27 Theories regarding the pathogenesis of TGA are diverse and include vascular, epileptic, migraine, and stress-related etiologies.1,23

Early theories suggested arterial ischemia28 and epileptic phenomena29 as etiologies of TGA. The venous theory posits that TGA stems from jugular venous incompetency, causing venous flow and subsequent venous congestion in the medial temporal lobe, wherein lies the hippocampus. This theory is supported by several studies showing venous valve insufficiency as detected by ultrasonographic evaluation during the Valsalva maneuver in patients with TGA.30 This pathophysiologic mechanism may explain the occurrence of TGA in a specific cluster of cases, including men whose TGA episodes are precipitated by physical stress or the Valsalva maneuver.3 The migraine theory and stress theory share a similar proposed neurophysiologic mechanism.

The migraine theory stems from migraines being a known risk factor for TGA, particularly in middle-aged women.31 The stress theory is based on the known emotional precipitants and psychiatric comorbidities associated with TGA. Notably, both the migraine theory and stress theory implicate the role of excessive glutamate release as well as CNS depression.31,32 Glutamate targets the CA1 region of the hippocampus, which is involved in TGA and is known to have the highest density of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors among hippocampal regions.33

Given the heterogeneity of the demographics and stressors associated with TGA, multiple mechanisms for the disease process may coexist, leading to a similar clinical picture. In 2006, Quinette et al3 performed a multivariate analysis of variables associated with TGA, including age, sex, medical history, and presentation. They demonstrated 3 “clusters” of TGA pictures: women with anxiety or a personality disorder; men with physical precipitating events; and younger patients (age <56) with a history of migraine. These findings suggest TGA may have unique precipitants corresponding to multiple neurophysiologic mechanisms.

Transient global ischemia: Psychiatric features

Several studies have demonstrated psychiatric precipitants, features, and comorbidities associated with TGA. Of the TGA cases associated with precipitating events, 29% to 50% are associated with an emotional stressor.3,4 Examples of emotional stressors include a quarrel,4 the announcement of a birth or suicide, and a nightmare.15 For Ms. A, learning her daughter worked in the sex industry was an emotional stressor.2

During its acute phase, TGA has been shown to present with mood and anxiety symptoms.34 Moreover, during episodes, patients often demonstrate features of panic attacks, such as dizziness, fainting, choking, palpitations, and paresthesia.3,35

Continue to: Finally, patients with TGA...

Finally, patients with TGA are more likely to have psychiatric comorbidities than those without the condition. In a study of 25 patients who experienced TGA triggered by a precipitant, Inzitari et al4 found a strong association of TGA with phobic personality traits, including agoraphobia and simple phobic attitudes (ie, fear of traveling far from home or the sight of blood). Pantoni et al35 replicated these results in 2005 and found that in comparison to patients with TIA, patients with TGA are more likely to have personal and family histories of psychiatric disease. A 2014 study by Dohring et al36 found that compared to healthy controls, patients with TGA are more likely to have maladaptive coping strategies and stress responses. Patients with TGA tended to exhibit increased feelings of guilt, take more medication, and exhibit more anxiety compared to healthy controls.36

Treatment: Benzodiazepines

There are no published treatment guidelines for TGA. However, in case reports, benzodiazepines (specifically lorazepam37) have been shown to have utility in diagnosing and treating DA. The success of benzodiazepines is attributed to its gamma-aminobutyric acid mechanism, which involves inhibiting activity of the N-methyl-

However, the benzodiazepine midazolam has been identified as a precipitant of TGA. In a case report, Rinehart et al22 identified flumazenil—a benzodiazepine antagonist used primarily to treat retrograde postoperative amnesia—as an antidote. The potentially paradoxical role of benzodiazepines in both the precipitation and treatment of TGA may relate back to the heterogeneity of the etiologies of TGA. Further research comparing the treatment of TGA in patients with stress-induced TGA vs postoperative TGA is needed to better understand the neurochemical basis of TGA and work toward establishing optimal treatment options for different patient demographics.

A generally favorable prognosis

TGA carries a low risk of recurrence. In studies with 3- to 7-year follow-up periods, the recurrence rates ranged from 1.4% to 23.8%.23,35,38

Memory impairments may be present for 5 to 6 months following a TGA episode. The severity of these impairments may range from clinically unnoticeable to the patient meeting the criteria for mild cognitive impairment.23,39 The risk is higher in patients who have had recurrent TGA compared to those patients who have experienced only a single episode.23

Continue to: TGA does not increase...

TGA does not increase the risk of cerebrovascular events. There is controversy regarding a potentially increased risk for dementia as well as epilepsy, though there is insufficient evidence to support these findings.23,40

CASE CONTINUED

Five hours after the onset of Ms. A’s symptoms, the treatment team initiates oral lorazepam 1 mg. One hour after taking lorazepam, Ms. A’s anterograde and retrograde amnesia improve. She cannot recall why she was brought to the hospital but does remember the date and location, which she was not able to do on initial presentation. She feels safe, states a clear plan for self-care, and is discharged in the care of her partner. Though Ms. A’s memory improved soon after she received lorazepam, this improvement also could be attributed to the natural course of time, as TGA tends to resolve on its own within 24 hours.

Bottom Line

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is an episode of anterograde, and possibly retrograde, amnesia that lasts up to 24 hours. It represents an interesting diagnosis at the intersection of psychiatry and neurology. TGA has many established psychiatric risk factors and features—some of which may resemble conversion disorder—but these may only apply to a particular subset of patients, which reflects the heterogeneity of the condition.

Related Resources

- Sparaco M, Pascarella R, Muccio CF, et al. Forgetting the unforgettable: transient global amnesia part I: pathophysiology and etiology. J Clin Med. 2022;11(12): 3373. doi:10.3390/jcm1112337

- Sparaco M, Pascarella R, Muccio CF, et al. Forgetting the unforgettable: transient global amnesia part II: a clinical road map. J Clin Med. 2022;11(14):3940. doi:10.3390/ jcm11143940

Drug Brand Names

Flumazenil • Romazicon

Lorazepam • Ativan

Midazolam • Versed

1. Miller TD, Butler CR. Acute-onset amnesia: transient global amnesia and other causes. Pract Neurol. 2022;22(3):201-208. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2020-002826

2. Hodges JR, Warlow CP. Syndromes of transient amnesia: towards a classification. A study of 153 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53(10):834-843. doi:10.1136/jnnp.53.10.834

3. Quinette P, Guillery-Girard B, Dayan J, et al. What does transient global amnesia really mean? Review of the literature and thorough study of 142 cases. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 7):1640-1658. doi:10.1093/brain/awl105

4. Inzitari D, Pantoni L, Lamassa M, et al. Emotional arousal and phobia in transient global amnesia. Arch Neurol. 1997;54(7):866-873. doi:10.1001/archneur.1997.00550190056015

5. Staniloiu A, Markowitsch HJ. Dissociative amnesia. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(3):226-241. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70279-2

6. Espiridion ED, Gupta J, Bshara A, et al. Transient global amnesia in a 60-year-old female with post-traumatic stress disorder. Cureus. 2019;11(9):e5792. doi:10.7759/cureus.5792

7. Alessandro L, Ricciardi M, Chaves H, et al. Acute amnestic syndromes. J Neurol Sci. 2020;413:116781. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2020.116781

8. Bender M. Syndrome of isolated episode of confusion with amnesia. J Hillside Hosp. 1956;5:212-215.

9. Courjon J, Guyotat J. Les ictus amnéstiques [Amnesic strokes]. J Med Lyon. 1956;37(882):697-701.

10. Noel A, Quinette P, Hainselin M, et al. The still enigmatic syndrome of transient global amnesia: interactions between neurological and psychopathological factors. Neuropsychol Rev. 2015;25(2):125-133. doi:10.1007/s11065-015-9284-y

11. Merriam AE, Wyszynski B, Betzler T. Emotional arousal-induced transient global amnesia. A clue to the neural transcription of emotion? Psychosomatics. 1992;33(1):109-113. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(92)72029-5

12. Hallett M, Aybek S, Dworetzky BA, et al. Functional neurological disorder: new subtypes and shared mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(6):537-550. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00422-1

13. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

14. Bourdon B, Dide M. A case of continuous amnesia with tactile asymbolia, complicated by other troubles. Ann Psychol. 1903;10:84-115.

15. Marinella MA. Transient global amnesia and a father’s worst nightmare. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(8):843-844. doi:10.1056/NEJM200402193500821

16. Amarenco P. Transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1933-1941. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1908837

17. Szabo K, Forster A, Jager T, et al. Hippocampal lesion patterns in acute posterior cerebral artery stroke: clinical and MRI findings. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2042-2045. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.536144

18. Liampas I, Raptopoulou M, Siokas V, et al. Conventional cardiovascular risk factors in transient global amnesia: systematic review and proposition of a novel hypothesis. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2021;61:100909. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2021.100909

19. Zeman A, Butler C. Transient epileptic amnesia. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23(6):610-616. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834027db

20. Baker J, Savage S, Milton F, et al. The syndrome of transient epileptic amnesia: a combined series of 115 cases and literature review. Brain Commun. 2021;3(2):fcab038. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcab038

21. Lanzone J, Ricci L, Assenza G, et al Transient epileptic and global amnesia: real-life differential diagnosis. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;88:205-211. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.07.015

22. Rinehart JB, Baker B, Raphael D. Postoperative global amnesia reversed with flumazenil. Neurologist. 2012;18(4):216-218. doi:10.1097/NRL.0b013e31825bbef4

23. Arena JE, Rabinstein AA. Transient global amnesia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(2):264-272. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.001

24. Holemans X, Dupuis M, Misson N, et al. Reversible amnesia in a type 1 diabetic patient and bilateral hippocampal lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Diabet Med. 2001;18(9):761-763. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00481.x

25. Marshman LAG, Jakabek D, Hennessy M, et al. Post-traumatic amnesia. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(11):1475-1481. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2012.11.022

26. Parker TD, Rees R, Rajagopal S, et al. Post-traumatic amnesia. Pract Neurol. 2022;22(2):129-137. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2021-003056

27. You SH, Kim B, Kim BK. Transient global amnesia: signal alteration in 2D/3D T2-FLAIR sequences. Clin Imaging. 2021;78:154-159. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.03.029

28. Mathew NT, Meyer JS. Pathogenesis and natural history of transient global amnesia. Stroke. 1974;5(3):303-311. doi:10.1161/01.str.5.3.303

29. Fisher CM, Adams RD. Transient global amnesia. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1964;40(SUPPL 9):1-83.

30. Cejas C, Cisneros LF, Lagos R, et al. Internal jugular vein valve incompetence is highly prevalent in transient global amnesia. Stroke. 2010;41(1):67-71. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.566315

31. Liampas I, Siouras AS, Siokas V, et al. Migraine in transient global amnesia: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Neurol. 2022;269(1):184-196. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-10363-y

32. Ding X, Peng D. Transient global amnesia: an electrophysiological disorder based on cortical spreading depression-transient global amnesia model. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:602496. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2020.602496

33. Bartsch T, Dohring J, Reuter S, et al. Selective neuronal vulnerability of human hippocampal CA1 neurons: lesion evolution, temporal course, and pattern of hippocampal damage in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35(11):1836-1845. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2015.137

34. Noel A, Quinette P, Guillery-Girard B, et al. Psychopathological factors, memory disorders and transient global amnesia. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(2):145-151. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045716

35. Pantoni L, Bertini E, Lamassa M, et al. Clinical features, risk factors, and prognosis in transient global amnesia: a follow-up study. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12(5):350-356. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00982.x

36. Dohring J, Schmuck A, Bartsch T. Stress-related factors in the emergence of transient global amnesia with hippocampal lesions. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:287. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00287

37. Jiang S, Gunther S, Hartney K, et al. An intravenous lorazepam infusion for dissociative amnesia: a case report. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(6):814-818. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2020.01.009

38. He S, Ye Z, Yang Q, et al. Transient global amnesia: risk factors, imaging features, and prognosis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:1611-1619. doi:10.2147/NDT.S299168

39. Borroni B, Agosti C, Brambilla C, et al. Is transient global amnesia a risk factor for amnestic mild cognitive impairment? J Neurol. 2004;251(9):1125-1127. doi:10.1007/s00415-004-0497-x

40. Liampas I, Raptopoulou M, Siokas V, et al. The long-term prognosis of transient global amnesia: a systematic review. Rev Neurosci. 2021;32(5):531-543. doi:10.1515/revneuro-2020-0110

1. Miller TD, Butler CR. Acute-onset amnesia: transient global amnesia and other causes. Pract Neurol. 2022;22(3):201-208. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2020-002826

2. Hodges JR, Warlow CP. Syndromes of transient amnesia: towards a classification. A study of 153 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53(10):834-843. doi:10.1136/jnnp.53.10.834

3. Quinette P, Guillery-Girard B, Dayan J, et al. What does transient global amnesia really mean? Review of the literature and thorough study of 142 cases. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 7):1640-1658. doi:10.1093/brain/awl105

4. Inzitari D, Pantoni L, Lamassa M, et al. Emotional arousal and phobia in transient global amnesia. Arch Neurol. 1997;54(7):866-873. doi:10.1001/archneur.1997.00550190056015

5. Staniloiu A, Markowitsch HJ. Dissociative amnesia. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(3):226-241. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70279-2

6. Espiridion ED, Gupta J, Bshara A, et al. Transient global amnesia in a 60-year-old female with post-traumatic stress disorder. Cureus. 2019;11(9):e5792. doi:10.7759/cureus.5792

7. Alessandro L, Ricciardi M, Chaves H, et al. Acute amnestic syndromes. J Neurol Sci. 2020;413:116781. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2020.116781

8. Bender M. Syndrome of isolated episode of confusion with amnesia. J Hillside Hosp. 1956;5:212-215.

9. Courjon J, Guyotat J. Les ictus amnéstiques [Amnesic strokes]. J Med Lyon. 1956;37(882):697-701.

10. Noel A, Quinette P, Hainselin M, et al. The still enigmatic syndrome of transient global amnesia: interactions between neurological and psychopathological factors. Neuropsychol Rev. 2015;25(2):125-133. doi:10.1007/s11065-015-9284-y

11. Merriam AE, Wyszynski B, Betzler T. Emotional arousal-induced transient global amnesia. A clue to the neural transcription of emotion? Psychosomatics. 1992;33(1):109-113. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(92)72029-5

12. Hallett M, Aybek S, Dworetzky BA, et al. Functional neurological disorder: new subtypes and shared mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(6):537-550. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00422-1

13. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

14. Bourdon B, Dide M. A case of continuous amnesia with tactile asymbolia, complicated by other troubles. Ann Psychol. 1903;10:84-115.

15. Marinella MA. Transient global amnesia and a father’s worst nightmare. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(8):843-844. doi:10.1056/NEJM200402193500821

16. Amarenco P. Transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1933-1941. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1908837

17. Szabo K, Forster A, Jager T, et al. Hippocampal lesion patterns in acute posterior cerebral artery stroke: clinical and MRI findings. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2042-2045. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.536144

18. Liampas I, Raptopoulou M, Siokas V, et al. Conventional cardiovascular risk factors in transient global amnesia: systematic review and proposition of a novel hypothesis. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2021;61:100909. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2021.100909

19. Zeman A, Butler C. Transient epileptic amnesia. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23(6):610-616. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834027db

20. Baker J, Savage S, Milton F, et al. The syndrome of transient epileptic amnesia: a combined series of 115 cases and literature review. Brain Commun. 2021;3(2):fcab038. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcab038

21. Lanzone J, Ricci L, Assenza G, et al Transient epileptic and global amnesia: real-life differential diagnosis. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;88:205-211. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.07.015

22. Rinehart JB, Baker B, Raphael D. Postoperative global amnesia reversed with flumazenil. Neurologist. 2012;18(4):216-218. doi:10.1097/NRL.0b013e31825bbef4

23. Arena JE, Rabinstein AA. Transient global amnesia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(2):264-272. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.001

24. Holemans X, Dupuis M, Misson N, et al. Reversible amnesia in a type 1 diabetic patient and bilateral hippocampal lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Diabet Med. 2001;18(9):761-763. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00481.x

25. Marshman LAG, Jakabek D, Hennessy M, et al. Post-traumatic amnesia. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(11):1475-1481. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2012.11.022

26. Parker TD, Rees R, Rajagopal S, et al. Post-traumatic amnesia. Pract Neurol. 2022;22(2):129-137. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2021-003056

27. You SH, Kim B, Kim BK. Transient global amnesia: signal alteration in 2D/3D T2-FLAIR sequences. Clin Imaging. 2021;78:154-159. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.03.029

28. Mathew NT, Meyer JS. Pathogenesis and natural history of transient global amnesia. Stroke. 1974;5(3):303-311. doi:10.1161/01.str.5.3.303

29. Fisher CM, Adams RD. Transient global amnesia. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1964;40(SUPPL 9):1-83.

30. Cejas C, Cisneros LF, Lagos R, et al. Internal jugular vein valve incompetence is highly prevalent in transient global amnesia. Stroke. 2010;41(1):67-71. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.566315

31. Liampas I, Siouras AS, Siokas V, et al. Migraine in transient global amnesia: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Neurol. 2022;269(1):184-196. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-10363-y

32. Ding X, Peng D. Transient global amnesia: an electrophysiological disorder based on cortical spreading depression-transient global amnesia model. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:602496. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2020.602496

33. Bartsch T, Dohring J, Reuter S, et al. Selective neuronal vulnerability of human hippocampal CA1 neurons: lesion evolution, temporal course, and pattern of hippocampal damage in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35(11):1836-1845. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2015.137

34. Noel A, Quinette P, Guillery-Girard B, et al. Psychopathological factors, memory disorders and transient global amnesia. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(2):145-151. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045716

35. Pantoni L, Bertini E, Lamassa M, et al. Clinical features, risk factors, and prognosis in transient global amnesia: a follow-up study. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12(5):350-356. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00982.x

36. Dohring J, Schmuck A, Bartsch T. Stress-related factors in the emergence of transient global amnesia with hippocampal lesions. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:287. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00287

37. Jiang S, Gunther S, Hartney K, et al. An intravenous lorazepam infusion for dissociative amnesia: a case report. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(6):814-818. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2020.01.009

38. He S, Ye Z, Yang Q, et al. Transient global amnesia: risk factors, imaging features, and prognosis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:1611-1619. doi:10.2147/NDT.S299168

39. Borroni B, Agosti C, Brambilla C, et al. Is transient global amnesia a risk factor for amnestic mild cognitive impairment? J Neurol. 2004;251(9):1125-1127. doi:10.1007/s00415-004-0497-x

40. Liampas I, Raptopoulou M, Siokas V, et al. The long-term prognosis of transient global amnesia: a systematic review. Rev Neurosci. 2021;32(5):531-543. doi:10.1515/revneuro-2020-0110