User login

When Skin Damage Takes Sides

A 61-year-old man is sent to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of several facial lesions. Although they have been present for years, the patient says they have never caused any symptoms.

The patient’s work history includes extensive outdoor activity, as well as more than 20 years of driving a truck. He is now retired and spends most of his days fishing.

He has a history of at least two unspecified skin cancers but denies receiving facial radiation treatment. He has been a smoker since age 12 and admits to heavy drinking.

EXAMINATION

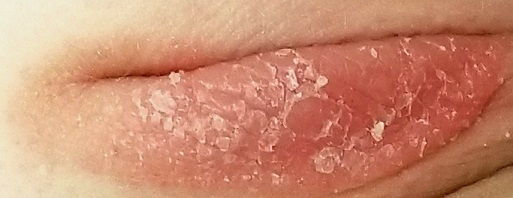

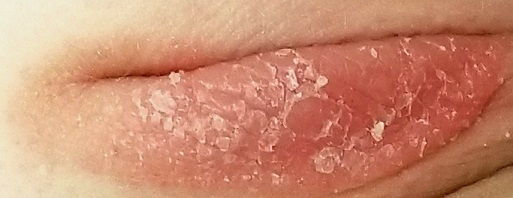

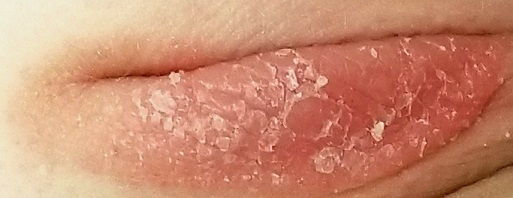

The patient’s face is uneven in appearance, with deep wrinkles and multiple areas of discoloration. His skin is type III.

Multiple open and closed comedones are seen around the left malar and brow areas, where the underlying skin has a whitish look to it. The comedones are not inflamed, and no pustules are observed. Some of the comedones extend into the infra-orbital area on the left side of his face. Almost no such changes are seen on the right side.

There is no increase in hair in the affected areas and no skin changes observed on his hands or arms, other than moderately severe sun damage.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the 1930s, two French dermatologists, Favre and Racouchot, began to see several cases like this one. Following a review of available literature, they published their findings, calling the condition “nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones.” This quickly became known as Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS), the name it still bears today.

FRS is quite common, especially on the faces of white men older than 50. More men than woman are affected, and smoking almost certainly contributes to the problem.

The connection between FRS and sun exposure is well established: the basophilic degeneration of the dermis (solar elastosis) seen in FRS is identical to that seen from overexposure to the sun. Another clue to the cause is exemplified in cases involving truck drivers, since the side of the face nearest the window is usually affected more than the other side. In most countries, the left side of the face sustains the most damage; in countries with right-hand drive, the right side of the face is affected.

Significant focal nodular solar elastosis, along with open and closed comedones, notably worse on the more sun-exposed side, is unique to FRS. The lack of increase in facial hair in the affected area is significant, in that it effectively rules out the only other major item in the differential: porphyria cutanea tarda.

Treatment is problematic at best. Except in younger patients, sunscreens are largely a waste. The comedones can be manually extracted, but recurrence is certain. For the truly motivated patient, laser resurfacing and peels can help. To slow the progression of the disease, smoking cessation is necessary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is most commonly seen in older men with a history of excessive chronic sun exposure. Most are smokers.

- FRS primarily affects the malar and lateral brow areas with nodular elastosis, in which are embedded multiple cysts and comedones.

- In the United States, FRS is usually more pronounced on the left side of the face.

- Other signs of chronic sun damage (actinic weathering, also known as dermatoheliosis) are almost always seen over the entire face of FRS patients.

A 61-year-old man is sent to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of several facial lesions. Although they have been present for years, the patient says they have never caused any symptoms.

The patient’s work history includes extensive outdoor activity, as well as more than 20 years of driving a truck. He is now retired and spends most of his days fishing.

He has a history of at least two unspecified skin cancers but denies receiving facial radiation treatment. He has been a smoker since age 12 and admits to heavy drinking.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s face is uneven in appearance, with deep wrinkles and multiple areas of discoloration. His skin is type III.

Multiple open and closed comedones are seen around the left malar and brow areas, where the underlying skin has a whitish look to it. The comedones are not inflamed, and no pustules are observed. Some of the comedones extend into the infra-orbital area on the left side of his face. Almost no such changes are seen on the right side.

There is no increase in hair in the affected areas and no skin changes observed on his hands or arms, other than moderately severe sun damage.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the 1930s, two French dermatologists, Favre and Racouchot, began to see several cases like this one. Following a review of available literature, they published their findings, calling the condition “nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones.” This quickly became known as Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS), the name it still bears today.

FRS is quite common, especially on the faces of white men older than 50. More men than woman are affected, and smoking almost certainly contributes to the problem.

The connection between FRS and sun exposure is well established: the basophilic degeneration of the dermis (solar elastosis) seen in FRS is identical to that seen from overexposure to the sun. Another clue to the cause is exemplified in cases involving truck drivers, since the side of the face nearest the window is usually affected more than the other side. In most countries, the left side of the face sustains the most damage; in countries with right-hand drive, the right side of the face is affected.

Significant focal nodular solar elastosis, along with open and closed comedones, notably worse on the more sun-exposed side, is unique to FRS. The lack of increase in facial hair in the affected area is significant, in that it effectively rules out the only other major item in the differential: porphyria cutanea tarda.

Treatment is problematic at best. Except in younger patients, sunscreens are largely a waste. The comedones can be manually extracted, but recurrence is certain. For the truly motivated patient, laser resurfacing and peels can help. To slow the progression of the disease, smoking cessation is necessary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is most commonly seen in older men with a history of excessive chronic sun exposure. Most are smokers.

- FRS primarily affects the malar and lateral brow areas with nodular elastosis, in which are embedded multiple cysts and comedones.

- In the United States, FRS is usually more pronounced on the left side of the face.

- Other signs of chronic sun damage (actinic weathering, also known as dermatoheliosis) are almost always seen over the entire face of FRS patients.

A 61-year-old man is sent to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of several facial lesions. Although they have been present for years, the patient says they have never caused any symptoms.

The patient’s work history includes extensive outdoor activity, as well as more than 20 years of driving a truck. He is now retired and spends most of his days fishing.

He has a history of at least two unspecified skin cancers but denies receiving facial radiation treatment. He has been a smoker since age 12 and admits to heavy drinking.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s face is uneven in appearance, with deep wrinkles and multiple areas of discoloration. His skin is type III.

Multiple open and closed comedones are seen around the left malar and brow areas, where the underlying skin has a whitish look to it. The comedones are not inflamed, and no pustules are observed. Some of the comedones extend into the infra-orbital area on the left side of his face. Almost no such changes are seen on the right side.

There is no increase in hair in the affected areas and no skin changes observed on his hands or arms, other than moderately severe sun damage.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the 1930s, two French dermatologists, Favre and Racouchot, began to see several cases like this one. Following a review of available literature, they published their findings, calling the condition “nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones.” This quickly became known as Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS), the name it still bears today.

FRS is quite common, especially on the faces of white men older than 50. More men than woman are affected, and smoking almost certainly contributes to the problem.

The connection between FRS and sun exposure is well established: the basophilic degeneration of the dermis (solar elastosis) seen in FRS is identical to that seen from overexposure to the sun. Another clue to the cause is exemplified in cases involving truck drivers, since the side of the face nearest the window is usually affected more than the other side. In most countries, the left side of the face sustains the most damage; in countries with right-hand drive, the right side of the face is affected.

Significant focal nodular solar elastosis, along with open and closed comedones, notably worse on the more sun-exposed side, is unique to FRS. The lack of increase in facial hair in the affected area is significant, in that it effectively rules out the only other major item in the differential: porphyria cutanea tarda.

Treatment is problematic at best. Except in younger patients, sunscreens are largely a waste. The comedones can be manually extracted, but recurrence is certain. For the truly motivated patient, laser resurfacing and peels can help. To slow the progression of the disease, smoking cessation is necessary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is most commonly seen in older men with a history of excessive chronic sun exposure. Most are smokers.

- FRS primarily affects the malar and lateral brow areas with nodular elastosis, in which are embedded multiple cysts and comedones.

- In the United States, FRS is usually more pronounced on the left side of the face.

- Other signs of chronic sun damage (actinic weathering, also known as dermatoheliosis) are almost always seen over the entire face of FRS patients.

A Nuisance for the Newlyweds

Prompted by his new bride, who is concerned she might “catch something” from him, a 53-year-old man self-refers for evaluation of a slightly itchy intergluteal rash. He’s had it for years; it waxes and wanes but never fully resolves.

It has been previously diagnosed as a yeast infection, fungal infection, and even herpes. But none of the respective treatments have helped.

More history-taking reveals a family history of psoriasis (maternal grandmother), but the patient denies other areas of involvement or other skin changes. He also denies having arthritis.

EXAMINATION

A salmon-pink, 7-cm, roughly round dry patch covered by white tenacious scale is located in the upper intergluteal/sacral interface. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

A similar process is noted in the periumbilical area (a difficult area for this patient to see, due to his weight). Inspection of his fingernails reveals 3/10 with definite tiny pits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The urge to call any and every rash occurring near the genitals a yeast infection is universally compelling among primary care providers. It is often so reflexive that even when anti-yeast medications fail, the provider hangs onto the diagnosis. This happens for one simple reason: Their differential is lacking.

This patient has psoriasis, albeit a somewhat unusual form, which demonstrates an important learning point: Psoriasis can present in any number of ways, not just in the standard “extensor surfaces of elbows and knees” distribution. It’s not unusual for psoriasis to zero in on one or two areas. I’ve seen it confined to the groin, the genitals, and the scalp. It can even involve the oral mucosa.

In these somewhat obscure cases, additional findings can be helpful to establish the diagnosis. The two areas of involvement in this case—the upper intergluteal area and the periumbilical region—may not fit the classic “knees and elbows” picture of psoriasis, but they are not atypical for the disease. Add the nail pits, the fixed nature of the problem, and the family history, and you’ve nailed the diagnosis.

Don’t forget that, occasionally, psoriatic arthropathy can precede the appearance of psoriasis, and that the severity of one does not predict the severity of the other.

Finally, in a fair number of cases, the diagnosis of psoriasis must be made by biopsy, which shows characteristic changes such as parakeratosis, epidermal thickening, and fusing of rete ridges. These “psoriasiform” changes seen microscopically must be corroborated by clinical findings, though, since many other papulosquamous diseases can exhibit similar changes.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Psoriasis is one of the more common dermatoses in this country, which means you will see it with some frequency.

- Psoriasis can affect limited or atypical areas, but corroboration of the diagnosis can be sought in classic areas (nails, scalp, upper intergluteal and periumbilical areas).

- Strive to develop alternative diagnoses for similar rashes—in other words, build your differential for “yeast infection.”

Prompted by his new bride, who is concerned she might “catch something” from him, a 53-year-old man self-refers for evaluation of a slightly itchy intergluteal rash. He’s had it for years; it waxes and wanes but never fully resolves.

It has been previously diagnosed as a yeast infection, fungal infection, and even herpes. But none of the respective treatments have helped.

More history-taking reveals a family history of psoriasis (maternal grandmother), but the patient denies other areas of involvement or other skin changes. He also denies having arthritis.

EXAMINATION

A salmon-pink, 7-cm, roughly round dry patch covered by white tenacious scale is located in the upper intergluteal/sacral interface. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

A similar process is noted in the periumbilical area (a difficult area for this patient to see, due to his weight). Inspection of his fingernails reveals 3/10 with definite tiny pits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The urge to call any and every rash occurring near the genitals a yeast infection is universally compelling among primary care providers. It is often so reflexive that even when anti-yeast medications fail, the provider hangs onto the diagnosis. This happens for one simple reason: Their differential is lacking.

This patient has psoriasis, albeit a somewhat unusual form, which demonstrates an important learning point: Psoriasis can present in any number of ways, not just in the standard “extensor surfaces of elbows and knees” distribution. It’s not unusual for psoriasis to zero in on one or two areas. I’ve seen it confined to the groin, the genitals, and the scalp. It can even involve the oral mucosa.

In these somewhat obscure cases, additional findings can be helpful to establish the diagnosis. The two areas of involvement in this case—the upper intergluteal area and the periumbilical region—may not fit the classic “knees and elbows” picture of psoriasis, but they are not atypical for the disease. Add the nail pits, the fixed nature of the problem, and the family history, and you’ve nailed the diagnosis.

Don’t forget that, occasionally, psoriatic arthropathy can precede the appearance of psoriasis, and that the severity of one does not predict the severity of the other.

Finally, in a fair number of cases, the diagnosis of psoriasis must be made by biopsy, which shows characteristic changes such as parakeratosis, epidermal thickening, and fusing of rete ridges. These “psoriasiform” changes seen microscopically must be corroborated by clinical findings, though, since many other papulosquamous diseases can exhibit similar changes.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Psoriasis is one of the more common dermatoses in this country, which means you will see it with some frequency.

- Psoriasis can affect limited or atypical areas, but corroboration of the diagnosis can be sought in classic areas (nails, scalp, upper intergluteal and periumbilical areas).

- Strive to develop alternative diagnoses for similar rashes—in other words, build your differential for “yeast infection.”

Prompted by his new bride, who is concerned she might “catch something” from him, a 53-year-old man self-refers for evaluation of a slightly itchy intergluteal rash. He’s had it for years; it waxes and wanes but never fully resolves.

It has been previously diagnosed as a yeast infection, fungal infection, and even herpes. But none of the respective treatments have helped.

More history-taking reveals a family history of psoriasis (maternal grandmother), but the patient denies other areas of involvement or other skin changes. He also denies having arthritis.

EXAMINATION

A salmon-pink, 7-cm, roughly round dry patch covered by white tenacious scale is located in the upper intergluteal/sacral interface. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

A similar process is noted in the periumbilical area (a difficult area for this patient to see, due to his weight). Inspection of his fingernails reveals 3/10 with definite tiny pits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The urge to call any and every rash occurring near the genitals a yeast infection is universally compelling among primary care providers. It is often so reflexive that even when anti-yeast medications fail, the provider hangs onto the diagnosis. This happens for one simple reason: Their differential is lacking.

This patient has psoriasis, albeit a somewhat unusual form, which demonstrates an important learning point: Psoriasis can present in any number of ways, not just in the standard “extensor surfaces of elbows and knees” distribution. It’s not unusual for psoriasis to zero in on one or two areas. I’ve seen it confined to the groin, the genitals, and the scalp. It can even involve the oral mucosa.

In these somewhat obscure cases, additional findings can be helpful to establish the diagnosis. The two areas of involvement in this case—the upper intergluteal area and the periumbilical region—may not fit the classic “knees and elbows” picture of psoriasis, but they are not atypical for the disease. Add the nail pits, the fixed nature of the problem, and the family history, and you’ve nailed the diagnosis.

Don’t forget that, occasionally, psoriatic arthropathy can precede the appearance of psoriasis, and that the severity of one does not predict the severity of the other.

Finally, in a fair number of cases, the diagnosis of psoriasis must be made by biopsy, which shows characteristic changes such as parakeratosis, epidermal thickening, and fusing of rete ridges. These “psoriasiform” changes seen microscopically must be corroborated by clinical findings, though, since many other papulosquamous diseases can exhibit similar changes.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Psoriasis is one of the more common dermatoses in this country, which means you will see it with some frequency.

- Psoriasis can affect limited or atypical areas, but corroboration of the diagnosis can be sought in classic areas (nails, scalp, upper intergluteal and periumbilical areas).

- Strive to develop alternative diagnoses for similar rashes—in other words, build your differential for “yeast infection.”

“It Gets Better With Age”

Since birth, this now–13-year-old boy has had redness on his face— the intensity of which has slowly increased with time. Various providers have offered a plethora of diagnoses, but no treatment attempts thus far have helped. The condition is asymptomatic but nonetheless distressing to the patient.

More history-taking reveals that, when he was about 6, crops of tiny papules developed on both triceps, his buttocks, and his upper back. These, too, have resisted treatment with OTC creams.

Neither of the boy’s two siblings have had any similar lesions, and no one in the family has any related health problems (eg, atopic diatheses).

EXAMINATION

The posterior 2/3 of both sides of the patient’s face are strikingly red. His nasolabial folds are spared, but the redness extends posteriorly to the immediate preauricular areas and vertically from the zygoma to the jawline. The erythema is highly blanchable with digital pressure and has a uniformly rough, papular feel. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

The papules on the triceps, anterior thighs, and upper back are uniform in size (pinpoint, measuring ≤ 1 mm) and distribution, obviously originating from follicles. Unlike the face, these areas are not erythematous.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

There are several types of keratosis pilaris (KP), including rubra faceii, the form affecting this patient (distinguished in part by involvement of the facial skin). KP is utterly common, affecting 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide, with no gender preference. This autosomal dominant disorder involves follicular keratinization—normal keratin (produced in the hair follicle) builds up and creates a “plug” that manifests as a firm, dry papule. Obstruction of the follicular orifice may be significant enough to prevent hair from exiting, in which case, the hair continues to grow but simply curls in on itself and accentuates the appearance of the papule.

Although KP is a condition and not a disease, it is often considered part of the atopic diatheses, which include the major diagnostic criteria of eczema, urticaria, and seasonal allergies. KP is often mistaken for acne, especially when it affects the face, but its lack of comedones and pustules is a distinguishing characteristic.

Keratosis follicularis (Darier disease) also features follicular papules, but the distribution and morphology differ significantly. Darier is a more serious problem in terms of extent and symptomatology.

Treatment of KP is unsatisfactory at best, but emollients can make it less bumpy. Salicylic acid and lactic acid–containing preparations can also help, but only temporarily. Gentle exfoliation followed by the application of heavy oils is considered the most effective treatment method. The most encouraging thing we can tell our patients: The problem tends to lessen with age.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common inherited defect of follicular keratinization that affects 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide.

- KP results in a distribution of follicular rough papules across the face, triceps, thighs, buttocks, and upper back, beginning in early childhood.

- A significant percentage of affected patients exhibit the variant termed rubra faceii, which involves the posterior 2/3 of the bilateral face.

- Treatment is problematic, but the application of emollients after gentle exfoliation can help; most cases improve as the patient ages.

Since birth, this now–13-year-old boy has had redness on his face— the intensity of which has slowly increased with time. Various providers have offered a plethora of diagnoses, but no treatment attempts thus far have helped. The condition is asymptomatic but nonetheless distressing to the patient.

More history-taking reveals that, when he was about 6, crops of tiny papules developed on both triceps, his buttocks, and his upper back. These, too, have resisted treatment with OTC creams.

Neither of the boy’s two siblings have had any similar lesions, and no one in the family has any related health problems (eg, atopic diatheses).

EXAMINATION

The posterior 2/3 of both sides of the patient’s face are strikingly red. His nasolabial folds are spared, but the redness extends posteriorly to the immediate preauricular areas and vertically from the zygoma to the jawline. The erythema is highly blanchable with digital pressure and has a uniformly rough, papular feel. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

The papules on the triceps, anterior thighs, and upper back are uniform in size (pinpoint, measuring ≤ 1 mm) and distribution, obviously originating from follicles. Unlike the face, these areas are not erythematous.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

There are several types of keratosis pilaris (KP), including rubra faceii, the form affecting this patient (distinguished in part by involvement of the facial skin). KP is utterly common, affecting 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide, with no gender preference. This autosomal dominant disorder involves follicular keratinization—normal keratin (produced in the hair follicle) builds up and creates a “plug” that manifests as a firm, dry papule. Obstruction of the follicular orifice may be significant enough to prevent hair from exiting, in which case, the hair continues to grow but simply curls in on itself and accentuates the appearance of the papule.

Although KP is a condition and not a disease, it is often considered part of the atopic diatheses, which include the major diagnostic criteria of eczema, urticaria, and seasonal allergies. KP is often mistaken for acne, especially when it affects the face, but its lack of comedones and pustules is a distinguishing characteristic.

Keratosis follicularis (Darier disease) also features follicular papules, but the distribution and morphology differ significantly. Darier is a more serious problem in terms of extent and symptomatology.

Treatment of KP is unsatisfactory at best, but emollients can make it less bumpy. Salicylic acid and lactic acid–containing preparations can also help, but only temporarily. Gentle exfoliation followed by the application of heavy oils is considered the most effective treatment method. The most encouraging thing we can tell our patients: The problem tends to lessen with age.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common inherited defect of follicular keratinization that affects 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide.

- KP results in a distribution of follicular rough papules across the face, triceps, thighs, buttocks, and upper back, beginning in early childhood.

- A significant percentage of affected patients exhibit the variant termed rubra faceii, which involves the posterior 2/3 of the bilateral face.

- Treatment is problematic, but the application of emollients after gentle exfoliation can help; most cases improve as the patient ages.

Since birth, this now–13-year-old boy has had redness on his face— the intensity of which has slowly increased with time. Various providers have offered a plethora of diagnoses, but no treatment attempts thus far have helped. The condition is asymptomatic but nonetheless distressing to the patient.

More history-taking reveals that, when he was about 6, crops of tiny papules developed on both triceps, his buttocks, and his upper back. These, too, have resisted treatment with OTC creams.

Neither of the boy’s two siblings have had any similar lesions, and no one in the family has any related health problems (eg, atopic diatheses).

EXAMINATION

The posterior 2/3 of both sides of the patient’s face are strikingly red. His nasolabial folds are spared, but the redness extends posteriorly to the immediate preauricular areas and vertically from the zygoma to the jawline. The erythema is highly blanchable with digital pressure and has a uniformly rough, papular feel. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

The papules on the triceps, anterior thighs, and upper back are uniform in size (pinpoint, measuring ≤ 1 mm) and distribution, obviously originating from follicles. Unlike the face, these areas are not erythematous.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

There are several types of keratosis pilaris (KP), including rubra faceii, the form affecting this patient (distinguished in part by involvement of the facial skin). KP is utterly common, affecting 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide, with no gender preference. This autosomal dominant disorder involves follicular keratinization—normal keratin (produced in the hair follicle) builds up and creates a “plug” that manifests as a firm, dry papule. Obstruction of the follicular orifice may be significant enough to prevent hair from exiting, in which case, the hair continues to grow but simply curls in on itself and accentuates the appearance of the papule.

Although KP is a condition and not a disease, it is often considered part of the atopic diatheses, which include the major diagnostic criteria of eczema, urticaria, and seasonal allergies. KP is often mistaken for acne, especially when it affects the face, but its lack of comedones and pustules is a distinguishing characteristic.

Keratosis follicularis (Darier disease) also features follicular papules, but the distribution and morphology differ significantly. Darier is a more serious problem in terms of extent and symptomatology.

Treatment of KP is unsatisfactory at best, but emollients can make it less bumpy. Salicylic acid and lactic acid–containing preparations can also help, but only temporarily. Gentle exfoliation followed by the application of heavy oils is considered the most effective treatment method. The most encouraging thing we can tell our patients: The problem tends to lessen with age.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common inherited defect of follicular keratinization that affects 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide.

- KP results in a distribution of follicular rough papules across the face, triceps, thighs, buttocks, and upper back, beginning in early childhood.

- A significant percentage of affected patients exhibit the variant termed rubra faceii, which involves the posterior 2/3 of the bilateral face.

- Treatment is problematic, but the application of emollients after gentle exfoliation can help; most cases improve as the patient ages.

Location Does Not Matter

Several months ago, this 7-year-old girl noticed a lesion on her outer vagina. In addition to growing larger, the lesion has begun to itch.

The patient’s mother has attempted treatment with anti-yeast cream and 1% hydrocortisone cream; neither has helped.

Both mother and daughter deny any recent trauma to the area, presence of similar lesions, or family history of skin disease or arthritis.

The child is well in all other respects; she takes no medications and has no history of serious illnesses or surgeries.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, 8- x 2-cm, salmon-pink plaque covered with uniform tenacious white scale is located on the left labia majora in a vertical orientation. The margins are sharply defined. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

No similar changes are seen on the elbows, knees, scalp, trunk, or nails.

A biopsy of the lesion is performed. The pathology report shows parakeratosis and elongation of rete ridges.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The morphology of this lesion is a perfect fit for psoriasis, a very common disease affecting about 3% of the white population in this country. Mentally repositioning this lesion to the elbow, trunk, or knee would have made the diagnosis obvious; these are the most commonly affected areas, while the genitals are among the least common. But a white-feathered bird with an orange bill and feet who greets you with a quack is probably a duck, even if it’s sitting on your dining room table.

Even for an experienced dermatology provider (35 years in the field), seeing this lesion in this location was a momentary shock. After all, there’s an 18-item differential for genital rashes—but very few look like this.

Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus is commonly seen on young girls in this area, but it is atrophic with almost no scale. Lichen simplex chronicus can be scaly and plaquish, but it rarely appears this organized.

In most primary care settings, this would be (and was) called a “yeast infection.” Not only do yeast infections not look a thing like this, there also needs to be an underlying reason for that diagnosis (eg, use of antibiotics, history of diabetes).

Biopsy is the only way to confirm this diagnosis, to give the family some peace of mind and guide appropriate therapy.

We discussed the diagnosis thoroughly with the parents, including the etiology, potential treatments, and prognosis. Treatment was initiated with topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid. If it proves necessary, we could increase the potency of the steroid, inject the lesion with steroid, or even start her on methotrexate.

She’ll also be closely followed for signs of worsening disease and for psoriatic arthropathy, which affects almost 25% of patients with psoriasis. She’ll be fortunate if this is the extent of her disease.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Salmon-pink, scaly plaques are psoriatic until proven otherwise.

- Psoriasis is common, affecting almost 3% of the white population.

- Though most often seen on extensor surfaces of arms, legs, and trunk, psoriasis can appear virtually anywhere.

- Mentally transpositioning a lesion to another location can be helpful in sorting through this differential.

Several months ago, this 7-year-old girl noticed a lesion on her outer vagina. In addition to growing larger, the lesion has begun to itch.

The patient’s mother has attempted treatment with anti-yeast cream and 1% hydrocortisone cream; neither has helped.

Both mother and daughter deny any recent trauma to the area, presence of similar lesions, or family history of skin disease or arthritis.

The child is well in all other respects; she takes no medications and has no history of serious illnesses or surgeries.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, 8- x 2-cm, salmon-pink plaque covered with uniform tenacious white scale is located on the left labia majora in a vertical orientation. The margins are sharply defined. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

No similar changes are seen on the elbows, knees, scalp, trunk, or nails.

A biopsy of the lesion is performed. The pathology report shows parakeratosis and elongation of rete ridges.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The morphology of this lesion is a perfect fit for psoriasis, a very common disease affecting about 3% of the white population in this country. Mentally repositioning this lesion to the elbow, trunk, or knee would have made the diagnosis obvious; these are the most commonly affected areas, while the genitals are among the least common. But a white-feathered bird with an orange bill and feet who greets you with a quack is probably a duck, even if it’s sitting on your dining room table.

Even for an experienced dermatology provider (35 years in the field), seeing this lesion in this location was a momentary shock. After all, there’s an 18-item differential for genital rashes—but very few look like this.

Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus is commonly seen on young girls in this area, but it is atrophic with almost no scale. Lichen simplex chronicus can be scaly and plaquish, but it rarely appears this organized.

In most primary care settings, this would be (and was) called a “yeast infection.” Not only do yeast infections not look a thing like this, there also needs to be an underlying reason for that diagnosis (eg, use of antibiotics, history of diabetes).

Biopsy is the only way to confirm this diagnosis, to give the family some peace of mind and guide appropriate therapy.

We discussed the diagnosis thoroughly with the parents, including the etiology, potential treatments, and prognosis. Treatment was initiated with topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid. If it proves necessary, we could increase the potency of the steroid, inject the lesion with steroid, or even start her on methotrexate.

She’ll also be closely followed for signs of worsening disease and for psoriatic arthropathy, which affects almost 25% of patients with psoriasis. She’ll be fortunate if this is the extent of her disease.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Salmon-pink, scaly plaques are psoriatic until proven otherwise.

- Psoriasis is common, affecting almost 3% of the white population.

- Though most often seen on extensor surfaces of arms, legs, and trunk, psoriasis can appear virtually anywhere.

- Mentally transpositioning a lesion to another location can be helpful in sorting through this differential.

Several months ago, this 7-year-old girl noticed a lesion on her outer vagina. In addition to growing larger, the lesion has begun to itch.

The patient’s mother has attempted treatment with anti-yeast cream and 1% hydrocortisone cream; neither has helped.

Both mother and daughter deny any recent trauma to the area, presence of similar lesions, or family history of skin disease or arthritis.

The child is well in all other respects; she takes no medications and has no history of serious illnesses or surgeries.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, 8- x 2-cm, salmon-pink plaque covered with uniform tenacious white scale is located on the left labia majora in a vertical orientation. The margins are sharply defined. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

No similar changes are seen on the elbows, knees, scalp, trunk, or nails.

A biopsy of the lesion is performed. The pathology report shows parakeratosis and elongation of rete ridges.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The morphology of this lesion is a perfect fit for psoriasis, a very common disease affecting about 3% of the white population in this country. Mentally repositioning this lesion to the elbow, trunk, or knee would have made the diagnosis obvious; these are the most commonly affected areas, while the genitals are among the least common. But a white-feathered bird with an orange bill and feet who greets you with a quack is probably a duck, even if it’s sitting on your dining room table.

Even for an experienced dermatology provider (35 years in the field), seeing this lesion in this location was a momentary shock. After all, there’s an 18-item differential for genital rashes—but very few look like this.

Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus is commonly seen on young girls in this area, but it is atrophic with almost no scale. Lichen simplex chronicus can be scaly and plaquish, but it rarely appears this organized.

In most primary care settings, this would be (and was) called a “yeast infection.” Not only do yeast infections not look a thing like this, there also needs to be an underlying reason for that diagnosis (eg, use of antibiotics, history of diabetes).

Biopsy is the only way to confirm this diagnosis, to give the family some peace of mind and guide appropriate therapy.

We discussed the diagnosis thoroughly with the parents, including the etiology, potential treatments, and prognosis. Treatment was initiated with topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid. If it proves necessary, we could increase the potency of the steroid, inject the lesion with steroid, or even start her on methotrexate.

She’ll also be closely followed for signs of worsening disease and for psoriatic arthropathy, which affects almost 25% of patients with psoriasis. She’ll be fortunate if this is the extent of her disease.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Salmon-pink, scaly plaques are psoriatic until proven otherwise.

- Psoriasis is common, affecting almost 3% of the white population.

- Though most often seen on extensor surfaces of arms, legs, and trunk, psoriasis can appear virtually anywhere.

- Mentally transpositioning a lesion to another location can be helpful in sorting through this differential.

Sporting an Old Lesion

The lesion on this 12-year-old girl’s trunk has been present since birth, growing slowly as she has. Recently, an abrasion sustained during a basketball game caused the lesion to become swollen and tender. It has since returned to its original size and nontender state, but the change in appearance raised enough concern to prompt dermatologic consultation.

The child is otherwise healthy and reports having had very few sunburns, tanning easily (though seldom).

EXAMINATION

The lesion—an oval, nevoid, hair-bearing, uniformly brown plaque with a mammilated surface—is located on the right lower anterior abdominal wall and measures just short of 3 cm x 2 cm. It bears no sign of the recent trauma. The margins are clearly defined, and the lesion is nontender on palpation. No increased warmth is detected.

Overall, the patient’s type III skin has little, if any, evidence of excessive sun exposure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) affect about 1% of newborns, appearing within months after birth. There is no unanimity in opinion regarding their origin, although they appear to be hereditary in some cases.

About 50% of CMNs occur on the trunk and 15% on the head or neck; the rest are scattered about on the extremities. The distinctive morphologic appearance of the lesion helps to distinguish it from other items in the differential, such as warts or cancer.

Only rarely do CMNs raise concern for malignant potential. (Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.) So-called “giant” CMNs (> 20 cm) appear to be associated with the greatest risk, though the incidence of melanoma in children younger than 9 is only about 0.7 cases per million. Of particular concern are “bathing trunk” CMNs, which occasionally cover more than half of the body; affected patients need special attention from pediatric dermatologists who have the appropriate experience.

Neither “small” (< 2 cm) nor “medium” CMNs (> 2 cm, < 20 cm) are particularly worrisome in terms of malignancy. But depending on the location and original size, CMNs can become the object of unwanted attention or ridicule from peers—a little 1-cm lesion on an infant’s neck can grow four to six times its original size by puberty. And at that point, excision becomes much more problematic due to the likelihood of scarring.

Therefore, many experts advise excising some lesions early on, while the lesion and resulting scar are small—and before the child has a chance to develop any anxiety over it. If not excised, CMNs simply need to be watched for change (size, uniformity of color, and border).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) < 20 cm in diameter are generally quite safe but can grow much larger—often becoming a source of ridicule.

- Depending on the size, location, and appearance of the lesion, excision is justifiable before it has a chance to grow and become problematic.

- Children younger than 10 almost never develop melanoma (the rate is 0.7 cases per million)—and even when they do, it is almost never related to malignant transformation of a CMN.

- Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.

The lesion on this 12-year-old girl’s trunk has been present since birth, growing slowly as she has. Recently, an abrasion sustained during a basketball game caused the lesion to become swollen and tender. It has since returned to its original size and nontender state, but the change in appearance raised enough concern to prompt dermatologic consultation.

The child is otherwise healthy and reports having had very few sunburns, tanning easily (though seldom).

EXAMINATION

The lesion—an oval, nevoid, hair-bearing, uniformly brown plaque with a mammilated surface—is located on the right lower anterior abdominal wall and measures just short of 3 cm x 2 cm. It bears no sign of the recent trauma. The margins are clearly defined, and the lesion is nontender on palpation. No increased warmth is detected.

Overall, the patient’s type III skin has little, if any, evidence of excessive sun exposure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) affect about 1% of newborns, appearing within months after birth. There is no unanimity in opinion regarding their origin, although they appear to be hereditary in some cases.

About 50% of CMNs occur on the trunk and 15% on the head or neck; the rest are scattered about on the extremities. The distinctive morphologic appearance of the lesion helps to distinguish it from other items in the differential, such as warts or cancer.

Only rarely do CMNs raise concern for malignant potential. (Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.) So-called “giant” CMNs (> 20 cm) appear to be associated with the greatest risk, though the incidence of melanoma in children younger than 9 is only about 0.7 cases per million. Of particular concern are “bathing trunk” CMNs, which occasionally cover more than half of the body; affected patients need special attention from pediatric dermatologists who have the appropriate experience.

Neither “small” (< 2 cm) nor “medium” CMNs (> 2 cm, < 20 cm) are particularly worrisome in terms of malignancy. But depending on the location and original size, CMNs can become the object of unwanted attention or ridicule from peers—a little 1-cm lesion on an infant’s neck can grow four to six times its original size by puberty. And at that point, excision becomes much more problematic due to the likelihood of scarring.

Therefore, many experts advise excising some lesions early on, while the lesion and resulting scar are small—and before the child has a chance to develop any anxiety over it. If not excised, CMNs simply need to be watched for change (size, uniformity of color, and border).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) < 20 cm in diameter are generally quite safe but can grow much larger—often becoming a source of ridicule.

- Depending on the size, location, and appearance of the lesion, excision is justifiable before it has a chance to grow and become problematic.

- Children younger than 10 almost never develop melanoma (the rate is 0.7 cases per million)—and even when they do, it is almost never related to malignant transformation of a CMN.

- Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.

The lesion on this 12-year-old girl’s trunk has been present since birth, growing slowly as she has. Recently, an abrasion sustained during a basketball game caused the lesion to become swollen and tender. It has since returned to its original size and nontender state, but the change in appearance raised enough concern to prompt dermatologic consultation.

The child is otherwise healthy and reports having had very few sunburns, tanning easily (though seldom).

EXAMINATION

The lesion—an oval, nevoid, hair-bearing, uniformly brown plaque with a mammilated surface—is located on the right lower anterior abdominal wall and measures just short of 3 cm x 2 cm. It bears no sign of the recent trauma. The margins are clearly defined, and the lesion is nontender on palpation. No increased warmth is detected.

Overall, the patient’s type III skin has little, if any, evidence of excessive sun exposure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) affect about 1% of newborns, appearing within months after birth. There is no unanimity in opinion regarding their origin, although they appear to be hereditary in some cases.

About 50% of CMNs occur on the trunk and 15% on the head or neck; the rest are scattered about on the extremities. The distinctive morphologic appearance of the lesion helps to distinguish it from other items in the differential, such as warts or cancer.

Only rarely do CMNs raise concern for malignant potential. (Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.) So-called “giant” CMNs (> 20 cm) appear to be associated with the greatest risk, though the incidence of melanoma in children younger than 9 is only about 0.7 cases per million. Of particular concern are “bathing trunk” CMNs, which occasionally cover more than half of the body; affected patients need special attention from pediatric dermatologists who have the appropriate experience.

Neither “small” (< 2 cm) nor “medium” CMNs (> 2 cm, < 20 cm) are particularly worrisome in terms of malignancy. But depending on the location and original size, CMNs can become the object of unwanted attention or ridicule from peers—a little 1-cm lesion on an infant’s neck can grow four to six times its original size by puberty. And at that point, excision becomes much more problematic due to the likelihood of scarring.

Therefore, many experts advise excising some lesions early on, while the lesion and resulting scar are small—and before the child has a chance to develop any anxiety over it. If not excised, CMNs simply need to be watched for change (size, uniformity of color, and border).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) < 20 cm in diameter are generally quite safe but can grow much larger—often becoming a source of ridicule.

- Depending on the size, location, and appearance of the lesion, excision is justifiable before it has a chance to grow and become problematic.

- Children younger than 10 almost never develop melanoma (the rate is 0.7 cases per million)—and even when they do, it is almost never related to malignant transformation of a CMN.

- Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.

Eye Can’t See a Thing

About 10 years ago, this 63-year-old man noticed a lesion on his eyelid. It didn’t bother him, so he ignored it—until recently, when it reached a size sufficient to interfere with his vision. This development, and subsequent commentary from friends concerned by its proximity to his eye and fears of cancer, disturbed him enough to seek evaluation.

He first consulted an ophthalmologist, who provided a diagnosis that the patient promptly forgot. However, he was also advised to see a dermatologist or plastic surgeon for further evaluation, since the lesion does not affect the eye itself. The patient wants the lesion removed but seeks a dermatology referral first.

He denies pain, discomfort, or trauma to the affected area.

EXAMINATION

A translucent, round, 7-mm cystic lesion is located on the left lateral lower eyelid just below the margin, resembling a bleb. No redness is seen in the area. Palpation confirms the soft, cystic nature of the lesion.

Examination of the other eye and the rest of the patient’s facial skin reveals no abnormalities.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical presentation of an apocrine hidrocystoma (AH), a benign lesion of uncertain etiology. The eyelid is rich in apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous glands, all of which can transform into cysts via traumatic plugging.

AH is also known as cystadenoma, Moll gland cyst, or sudoriferous cyst. It is an entity distinct from chalazions (a granulomatous reaction to sebaceous glands in the eyelid) and lacrimal duct cysts. The differential includes basal cell carcinoma, intradermal nevus, and eccrine cyst.

In my experience, merely incising and draining the cyst is useless in the long run; while this does reduce swelling, it also invites recurrence. Therefore, removal by saucerization and cauterization of the base is the best treatment option.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Apocrine hidrocystomas (AHs) are benign cysts derived from plugged apocrine sweat glands, which are found in numerous areas around the body, including the eyes.

- AHs are also known as cystadenomas, Moll gland cysts, or sudoriferous cysts.

- Though AHs are often found near the eye, they are not technically an eye problem—but they do have potential to obstruct the visual field.

- Removal is usually by saucerization, with cautery of the base for hemostasis and prevention of recurrence.

About 10 years ago, this 63-year-old man noticed a lesion on his eyelid. It didn’t bother him, so he ignored it—until recently, when it reached a size sufficient to interfere with his vision. This development, and subsequent commentary from friends concerned by its proximity to his eye and fears of cancer, disturbed him enough to seek evaluation.

He first consulted an ophthalmologist, who provided a diagnosis that the patient promptly forgot. However, he was also advised to see a dermatologist or plastic surgeon for further evaluation, since the lesion does not affect the eye itself. The patient wants the lesion removed but seeks a dermatology referral first.

He denies pain, discomfort, or trauma to the affected area.

EXAMINATION

A translucent, round, 7-mm cystic lesion is located on the left lateral lower eyelid just below the margin, resembling a bleb. No redness is seen in the area. Palpation confirms the soft, cystic nature of the lesion.

Examination of the other eye and the rest of the patient’s facial skin reveals no abnormalities.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical presentation of an apocrine hidrocystoma (AH), a benign lesion of uncertain etiology. The eyelid is rich in apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous glands, all of which can transform into cysts via traumatic plugging.

AH is also known as cystadenoma, Moll gland cyst, or sudoriferous cyst. It is an entity distinct from chalazions (a granulomatous reaction to sebaceous glands in the eyelid) and lacrimal duct cysts. The differential includes basal cell carcinoma, intradermal nevus, and eccrine cyst.

In my experience, merely incising and draining the cyst is useless in the long run; while this does reduce swelling, it also invites recurrence. Therefore, removal by saucerization and cauterization of the base is the best treatment option.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Apocrine hidrocystomas (AHs) are benign cysts derived from plugged apocrine sweat glands, which are found in numerous areas around the body, including the eyes.

- AHs are also known as cystadenomas, Moll gland cysts, or sudoriferous cysts.

- Though AHs are often found near the eye, they are not technically an eye problem—but they do have potential to obstruct the visual field.

- Removal is usually by saucerization, with cautery of the base for hemostasis and prevention of recurrence.

About 10 years ago, this 63-year-old man noticed a lesion on his eyelid. It didn’t bother him, so he ignored it—until recently, when it reached a size sufficient to interfere with his vision. This development, and subsequent commentary from friends concerned by its proximity to his eye and fears of cancer, disturbed him enough to seek evaluation.

He first consulted an ophthalmologist, who provided a diagnosis that the patient promptly forgot. However, he was also advised to see a dermatologist or plastic surgeon for further evaluation, since the lesion does not affect the eye itself. The patient wants the lesion removed but seeks a dermatology referral first.

He denies pain, discomfort, or trauma to the affected area.

EXAMINATION

A translucent, round, 7-mm cystic lesion is located on the left lateral lower eyelid just below the margin, resembling a bleb. No redness is seen in the area. Palpation confirms the soft, cystic nature of the lesion.

Examination of the other eye and the rest of the patient’s facial skin reveals no abnormalities.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical presentation of an apocrine hidrocystoma (AH), a benign lesion of uncertain etiology. The eyelid is rich in apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous glands, all of which can transform into cysts via traumatic plugging.

AH is also known as cystadenoma, Moll gland cyst, or sudoriferous cyst. It is an entity distinct from chalazions (a granulomatous reaction to sebaceous glands in the eyelid) and lacrimal duct cysts. The differential includes basal cell carcinoma, intradermal nevus, and eccrine cyst.

In my experience, merely incising and draining the cyst is useless in the long run; while this does reduce swelling, it also invites recurrence. Therefore, removal by saucerization and cauterization of the base is the best treatment option.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Apocrine hidrocystomas (AHs) are benign cysts derived from plugged apocrine sweat glands, which are found in numerous areas around the body, including the eyes.

- AHs are also known as cystadenomas, Moll gland cysts, or sudoriferous cysts.

- Though AHs are often found near the eye, they are not technically an eye problem—but they do have potential to obstruct the visual field.

- Removal is usually by saucerization, with cautery of the base for hemostasis and prevention of recurrence.

Not on My Watch!

The itchy patch of skin on this 60-year-old man’s forearm, beneath his watch, has troubled him intermittently for a year. It is unresponsive to topical medications, including tolnaftate cream and 1% hydrocortisone cream; the latter seemed to improve the condition initially, but with time, the patch grew larger and itchier.

The patient’s primary care provider believed the rash might be precancerous and prescribed 5-fluorouracil cream, which showed no benefit. The patient was then referred to a dermatologist, who performed a KOH examination. No fungal elements were found.

At that point, the patient decided to simply ignore the problem. That resolve ended when the itchiness increased—leading to his presentation today. He is in decent health but has had a kidney transplant and is taking the standard immunosuppressant (anti-rejection) medications.

EXAMINATION

A faintly pink, scaly rash is located on the patient’s forearm. It is unimpressive in appearance but very bothersome to the patient.

Despite the patient’s history, fungal origin remains a possibility, as does psoriasis. A punch biopsy is performed.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The biopsy results showed numerous fungal elements crowded around deeper aspects of hair follicles and a granulomatous reaction in the surrounding skin.

Normally, dermatophytes (the organisms that cause superficial fungal infections) are incapable of invading deeper tissues, making KOH exam a simple diagnostic method. But with immune suppression, the infection is able to invade deeper structures, making it more difficult to diagnose and treat. In this patient’s case, the use of steroid creams under occlusion (ie, the watch) had suppressed the body’s immune response to the infection.

The terminology used to describe this phenomenon varies according to the severity of infection. Tinea incognito might be used to describe this patient’s case, in which the steroid rendered the condition almost impossible to diagnose visually. With continued use of stronger topical steroids, the degree of inflammation might have been worse, involving deeper, larger nodules instead of faint pink scaling. In such cases, the term Majocchi fungal granuloma is used.

This patient moved his watch to the other arm temporarily and was successfully treated with twice-daily application of topical econazole cream and a two-week course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Immunosuppression can make fungal infections more difficult to diagnose and treat.

- Dermatophytes don’t normally invade deeper structures and can usually be detected with a KOH exam of surface skin cells.

- If the patient is immunocompromised, a fungal diagnosis is best confirmed with a punch biopsy, and treatment achieved with a combination of oral and topical antifungal products.

- Mild cases of this kind are termed tinea incognito, while more severe cases are called Majocchi fungal granuloma.

The itchy patch of skin on this 60-year-old man’s forearm, beneath his watch, has troubled him intermittently for a year. It is unresponsive to topical medications, including tolnaftate cream and 1% hydrocortisone cream; the latter seemed to improve the condition initially, but with time, the patch grew larger and itchier.

The patient’s primary care provider believed the rash might be precancerous and prescribed 5-fluorouracil cream, which showed no benefit. The patient was then referred to a dermatologist, who performed a KOH examination. No fungal elements were found.

At that point, the patient decided to simply ignore the problem. That resolve ended when the itchiness increased—leading to his presentation today. He is in decent health but has had a kidney transplant and is taking the standard immunosuppressant (anti-rejection) medications.

EXAMINATION

A faintly pink, scaly rash is located on the patient’s forearm. It is unimpressive in appearance but very bothersome to the patient.

Despite the patient’s history, fungal origin remains a possibility, as does psoriasis. A punch biopsy is performed.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The biopsy results showed numerous fungal elements crowded around deeper aspects of hair follicles and a granulomatous reaction in the surrounding skin.

Normally, dermatophytes (the organisms that cause superficial fungal infections) are incapable of invading deeper tissues, making KOH exam a simple diagnostic method. But with immune suppression, the infection is able to invade deeper structures, making it more difficult to diagnose and treat. In this patient’s case, the use of steroid creams under occlusion (ie, the watch) had suppressed the body’s immune response to the infection.

The terminology used to describe this phenomenon varies according to the severity of infection. Tinea incognito might be used to describe this patient’s case, in which the steroid rendered the condition almost impossible to diagnose visually. With continued use of stronger topical steroids, the degree of inflammation might have been worse, involving deeper, larger nodules instead of faint pink scaling. In such cases, the term Majocchi fungal granuloma is used.

This patient moved his watch to the other arm temporarily and was successfully treated with twice-daily application of topical econazole cream and a two-week course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Immunosuppression can make fungal infections more difficult to diagnose and treat.

- Dermatophytes don’t normally invade deeper structures and can usually be detected with a KOH exam of surface skin cells.

- If the patient is immunocompromised, a fungal diagnosis is best confirmed with a punch biopsy, and treatment achieved with a combination of oral and topical antifungal products.

- Mild cases of this kind are termed tinea incognito, while more severe cases are called Majocchi fungal granuloma.

The itchy patch of skin on this 60-year-old man’s forearm, beneath his watch, has troubled him intermittently for a year. It is unresponsive to topical medications, including tolnaftate cream and 1% hydrocortisone cream; the latter seemed to improve the condition initially, but with time, the patch grew larger and itchier.

The patient’s primary care provider believed the rash might be precancerous and prescribed 5-fluorouracil cream, which showed no benefit. The patient was then referred to a dermatologist, who performed a KOH examination. No fungal elements were found.

At that point, the patient decided to simply ignore the problem. That resolve ended when the itchiness increased—leading to his presentation today. He is in decent health but has had a kidney transplant and is taking the standard immunosuppressant (anti-rejection) medications.

EXAMINATION

A faintly pink, scaly rash is located on the patient’s forearm. It is unimpressive in appearance but very bothersome to the patient.

Despite the patient’s history, fungal origin remains a possibility, as does psoriasis. A punch biopsy is performed.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The biopsy results showed numerous fungal elements crowded around deeper aspects of hair follicles and a granulomatous reaction in the surrounding skin.

Normally, dermatophytes (the organisms that cause superficial fungal infections) are incapable of invading deeper tissues, making KOH exam a simple diagnostic method. But with immune suppression, the infection is able to invade deeper structures, making it more difficult to diagnose and treat. In this patient’s case, the use of steroid creams under occlusion (ie, the watch) had suppressed the body’s immune response to the infection.

The terminology used to describe this phenomenon varies according to the severity of infection. Tinea incognito might be used to describe this patient’s case, in which the steroid rendered the condition almost impossible to diagnose visually. With continued use of stronger topical steroids, the degree of inflammation might have been worse, involving deeper, larger nodules instead of faint pink scaling. In such cases, the term Majocchi fungal granuloma is used.

This patient moved his watch to the other arm temporarily and was successfully treated with twice-daily application of topical econazole cream and a two-week course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Immunosuppression can make fungal infections more difficult to diagnose and treat.

- Dermatophytes don’t normally invade deeper structures and can usually be detected with a KOH exam of surface skin cells.

- If the patient is immunocompromised, a fungal diagnosis is best confirmed with a punch biopsy, and treatment achieved with a combination of oral and topical antifungal products.

- Mild cases of this kind are termed tinea incognito, while more severe cases are called Majocchi fungal granuloma.

This Baby's Got Flare

At birth, this child had a lesion on his shoulder that now—a year later—has doubled in size. His parents report no systemic symptoms or medication use for their son. They say that the child exhibits no distress; he does not attempt to scratch at the affected patch of skin. However, they observe that if the lesion is touched, it swells and then (within minutes) returns to normal.

There is no family history of similar problems. However, both the patient and his mother are highly atopic.

EXAMINATION

The lesion—a low, orange, oval plaque—measures about 3.5 x 2 cm. Barely palpable, it urticates when stroked with a fingernail edge but does not appear to cause any discomfort.

No other lesions of note are found. The child appears quite healthy and is in no distress.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Mastocytosis is caused by a localized accumulation of mast cells (a type of white blood cell) and CD34-positive mast cell precursors, which are normally present but widely scattered and sparse. This child has the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis, which can manifest with solitary lesions or with dozens or hundreds of scattered lesions (the latter known as urticaria pigmentosa). Both types are typically benign and self-limited.

When stroked, mast cell lesions degranulate portions of the cell, releasing histamine precursors and leukotrienes (eg, IL 1 and IL 31). In most cases, stroking merely leads to short-lived urtication. But if the problem is more widespread (eg, urticaria pigmentosa) and the lesions are sufficiently traumatized, the release of these substances can lead to problems such as hypotension, malaise, fever, and abdominal pain.

Fortunately, this is rare, as is systemic mastocytosis—a condition in which mast cells infiltrate internal organs and bone marrow, interrupting normal function and, in the extreme, leading to mast cell leukemia. Our patient is not at risk for these complications; his lesion should resolve completely by age 3.

The differential for this patient’s lesion includes congenital nevus, lichen aureus, and café au lait spot.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Cutaneous mastocytosis manifests as a reddish orange maculopapular patch, which urticates upon forceful stroking.

- Stroking the lesion degranulates the mast cells comprising it, leading to the release of histamine precursors.

- Mast cells can infiltrate internal organs and bone marrow, leading, in the extreme, to mast cell leukemia.

- Urticaria pigmentosa is a variation of mastocytosis in which hundreds of such lesions develop all over the body.

At birth, this child had a lesion on his shoulder that now—a year later—has doubled in size. His parents report no systemic symptoms or medication use for their son. They say that the child exhibits no distress; he does not attempt to scratch at the affected patch of skin. However, they observe that if the lesion is touched, it swells and then (within minutes) returns to normal.

There is no family history of similar problems. However, both the patient and his mother are highly atopic.

EXAMINATION

The lesion—a low, orange, oval plaque—measures about 3.5 x 2 cm. Barely palpable, it urticates when stroked with a fingernail edge but does not appear to cause any discomfort.

No other lesions of note are found. The child appears quite healthy and is in no distress.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Mastocytosis is caused by a localized accumulation of mast cells (a type of white blood cell) and CD34-positive mast cell precursors, which are normally present but widely scattered and sparse. This child has the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis, which can manifest with solitary lesions or with dozens or hundreds of scattered lesions (the latter known as urticaria pigmentosa). Both types are typically benign and self-limited.

When stroked, mast cell lesions degranulate portions of the cell, releasing histamine precursors and leukotrienes (eg, IL 1 and IL 31). In most cases, stroking merely leads to short-lived urtication. But if the problem is more widespread (eg, urticaria pigmentosa) and the lesions are sufficiently traumatized, the release of these substances can lead to problems such as hypotension, malaise, fever, and abdominal pain.

Fortunately, this is rare, as is systemic mastocytosis—a condition in which mast cells infiltrate internal organs and bone marrow, interrupting normal function and, in the extreme, leading to mast cell leukemia. Our patient is not at risk for these complications; his lesion should resolve completely by age 3.

The differential for this patient’s lesion includes congenital nevus, lichen aureus, and café au lait spot.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Cutaneous mastocytosis manifests as a reddish orange maculopapular patch, which urticates upon forceful stroking.

- Stroking the lesion degranulates the mast cells comprising it, leading to the release of histamine precursors.

- Mast cells can infiltrate internal organs and bone marrow, leading, in the extreme, to mast cell leukemia.

- Urticaria pigmentosa is a variation of mastocytosis in which hundreds of such lesions develop all over the body.

At birth, this child had a lesion on his shoulder that now—a year later—has doubled in size. His parents report no systemic symptoms or medication use for their son. They say that the child exhibits no distress; he does not attempt to scratch at the affected patch of skin. However, they observe that if the lesion is touched, it swells and then (within minutes) returns to normal.

There is no family history of similar problems. However, both the patient and his mother are highly atopic.

EXAMINATION

The lesion—a low, orange, oval plaque—measures about 3.5 x 2 cm. Barely palpable, it urticates when stroked with a fingernail edge but does not appear to cause any discomfort.

No other lesions of note are found. The child appears quite healthy and is in no distress.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Mastocytosis is caused by a localized accumulation of mast cells (a type of white blood cell) and CD34-positive mast cell precursors, which are normally present but widely scattered and sparse. This child has the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis, which can manifest with solitary lesions or with dozens or hundreds of scattered lesions (the latter known as urticaria pigmentosa). Both types are typically benign and self-limited.

When stroked, mast cell lesions degranulate portions of the cell, releasing histamine precursors and leukotrienes (eg, IL 1 and IL 31). In most cases, stroking merely leads to short-lived urtication. But if the problem is more widespread (eg, urticaria pigmentosa) and the lesions are sufficiently traumatized, the release of these substances can lead to problems such as hypotension, malaise, fever, and abdominal pain.

Fortunately, this is rare, as is systemic mastocytosis—a condition in which mast cells infiltrate internal organs and bone marrow, interrupting normal function and, in the extreme, leading to mast cell leukemia. Our patient is not at risk for these complications; his lesion should resolve completely by age 3.

The differential for this patient’s lesion includes congenital nevus, lichen aureus, and café au lait spot.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Cutaneous mastocytosis manifests as a reddish orange maculopapular patch, which urticates upon forceful stroking.

- Stroking the lesion degranulates the mast cells comprising it, leading to the release of histamine precursors.

- Mast cells can infiltrate internal organs and bone marrow, leading, in the extreme, to mast cell leukemia.

- Urticaria pigmentosa is a variation of mastocytosis in which hundreds of such lesions develop all over the body.

The Mother of All Skin Problems

Each time this 32-year-old woman has a baby—she’s had four to date—she notices that sections of her face darken. Early on, she observed a pattern in which the coming of winter coincided with a lightening of these affected areas—but now the effect lasts year-round, with progressive darkening. She has not tried any products (OTC or prescription) for this problem.

Growing up in the South, the patient and her family spent most summers boating, swimming, and fishing. Her use of sunscreen was sporadic, but she would tan easily regardless.

Her health is good, aside from a 15-year history of smoking.

EXAMINATION

There is excessive hyperpigmentation (brown) on the patient’s face. It follows a mask-like pattern, including her maxilla and the periphery of her face.

Elsewhere, there is abundant evidence of excessive sun exposure, with focal hyperpigmentation and telangiectasias on her arms. She has type IV skin, consistent with her Native American ancestry.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Melasma, also known as chloasma and dubbed the “mask of pregnancy,” is an extremely common problem that results from a combination of naturally dark skin, lots of sun exposure, and increased levels of estrogenic hormones. The latter can result from pregnancy or from oral contraceptive or estrogen replacement therapy use. Another precipitating factor is thyroid disease, certain types of which lead to an increase in melanocytic stimulating hormone.

Melasma, as one might expect, is seen almost exclusively in women, though a rare male is affected. It is especially common among Latina, Native American, and African-American women, whose melanocytes are especially able to produce pigment.

There are several treatments for melasma, none of them perfect, including tretinoin, azelaic acid, chemical peels, dermabrasion, and lasers. The most common treatment is hydroquinone cream, available in the US in both OTC (2%) and prescription (4%) strengths. However, hydroquinone is available OTC in stronger formulations (15% to 20%) in many Central and South American countries; unfortunately, many women who obtain and use these products experience exogenous ochronosis—a worsening or even precipitation of melasma, resulting from excessive production of tyrosinase.

Any treatment must be used in conjunction with rigorous sunscreen application. A full-spectrum product, with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide as the only active ingredients, must be used, because chemical-laden sunscreens don’t do as good a job covering UVA, UVB, and visible light. Convincing women who are unaccustomed to needing sunscreen to use it religiously is part of what makes treating melasma difficult.

The differential for melasma includes postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (eg, following an episode of contact dermatitis) and simple solar lentigines.

This patient was treated with hydroquinone 4% cream bid, plus sunscreen. She was also given information about other treatment options, such as laser and dermabrasion.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Melasma, also known at chloasma, is quite common, especially among women with darker skin who live in sunny parts of the world.

- It results from a combination of dark skin, an increased level of estrogenic hormones (eg, with pregnancy, birth control pills, or estrogen replacement therapy), and excessive exposure to UV light.

- While hydroquinone cream can be an effective treatment, the maximum strength should be 4%; overuse of stronger concentrations (available in other countries, such as Mexico), can actually cause melasma to worsen.

Each time this 32-year-old woman has a baby—she’s had four to date—she notices that sections of her face darken. Early on, she observed a pattern in which the coming of winter coincided with a lightening of these affected areas—but now the effect lasts year-round, with progressive darkening. She has not tried any products (OTC or prescription) for this problem.

Growing up in the South, the patient and her family spent most summers boating, swimming, and fishing. Her use of sunscreen was sporadic, but she would tan easily regardless.

Her health is good, aside from a 15-year history of smoking.

EXAMINATION

There is excessive hyperpigmentation (brown) on the patient’s face. It follows a mask-like pattern, including her maxilla and the periphery of her face.

Elsewhere, there is abundant evidence of excessive sun exposure, with focal hyperpigmentation and telangiectasias on her arms. She has type IV skin, consistent with her Native American ancestry.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION