User login

Man has very uncomfortable problem

HISTORY

A 59-year-old uncircumcised man is referred by his primary care provider for evaluation of what he deems a “yeast infection” of the distal penis and foreskin. Numerous OTC creams (eg, tolnaftate, clotrimazole, hydrocortisone cream) have been tried, over a period of months, with no improvement in the condition. Now, the patient is experiencing increasing discomfort, not only with the rash itself, but also with actual urinary obstruction. Urination, he reports, has been “difficult” and “messy.”

EXAMINATION

The patient’s foreskin is bound down so tightly that it cannot be retracted without pain. Only a tiny opening remains through which the patient can urinate (with difficulty). The surface of the foreskin is atrophic, dry, and shiny. There is little, if any, redness or swelling, but focal areas of purpura are noted over the area.

DISCUSSION

Penile conditions are problematic for several reasons, not the least of which is the location. Many clinicians are not inclined to even look at the area, pleading ignorance of what they might see and preferring to stay in the diagnostic dark. It is certainly true that a provider would do well to have some idea of what he/she might see when examining a particular area of the body—a principle that applies just as much to elbows and fingernails as to penises.

This patient’s condition is called balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO), a diagnosis of sufficient obscurity to almost guarantee initial misdiagnosis as “yeast infection” or “herpes.” One treatment failure after another eventually leads to referral to a provider familiar with BXO, which is the male version of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) and usually affects the glans, foreskin, and distal shaft.

The causes of these conditions are as yet unknown. However, much is known about how they present, how they look under a microscope, and how to treat them.

LS&A in women itches terribly and presents with whitish atrophic skin changes that affect the perivaginal and perianal areas, sharply sparing the perineum, which gives it a figure-eight or butterfly look. Localized trauma can produce areas of purpura or even bullae. LS&A is not uncommon in children (females > males), in whom the associated focal purpura can be mistaken for a sign of sexual abuse.

Treatment entails use of the most powerful topical steroid ointments, which are so effective that they have completely replaced previous treatment options (eg, testosterone ointment). While a cure is unlikely, control is a realistic goal. If it is left untreated, not only are affected women miserable, but also the condition can lead to stenosis of the introitus and/or meatal stenosis and eventual urinary blockage.

BXO, as in this case, can also cause urinary obstruction, both from the overlying foreskin and from actual meatal stenosis. This is why advanced cases need referral to urology for possible circumcision. As with many penile diagnoses (eg, squamous cell carcinoma or condyloma), BXO is far more common in the uncircumcised.

Other conditions that belong in the differential include seborrhea, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, candidiasis, Bowen’s disease, and irritant/contact dermatitis. Biopsy is typically needed to confirm the diagnosis.

A more common presentation of BXO is a focally atrophic finish to the glans penis, with whitish highlights and a notably dry feel to the affected skin. But, as in this case, it can also affect the foreskin, leading to inflammation and adhesion of the foreskin to the shaft and glans.

In relatively uncomplicated cases, class 1 steroid ointments, such as clobetasol, are prescribed for twice-daily use in the beginning, with a reduction to once-daily use within about two weeks, and then finally to occasional use as the situation demands. Normally, a class 1 steroid would not be used on a thin-skinned area, but BXO responds quite well to it (and lower-strength steroids usually fail). Once control is achieved, the frequency of application is, of course, limited to as-needed use.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

1. There is a differential for penile conditions that includes a number of items beyond “yeast infection”: squamous cell carcinoma, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, lichen planus, and balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO).

2. Dermatology is the relevant initial specialty for these patients, not urology, although the ultimate resolution for balanitis is often surgical.

3. The female counterpart to BXO is called lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A); it is far more common but equally mysterious to providers unacquainted with it.

4. Biopsy—safe and easy to perform—is often necessary to establish the correct diagnosis. For example, a 3-mm punch biopsy, performed under local anesthesia and closed with a single polyglactin stitch, would provide an adequate specimen. Other things being equal, the use of lidocaine-containing epinephrine is perfectly acceptable (and often necessary!) in this area.

5. BXO/LS&A are now routinely treated with class 1 steroid ointments, such as clobetasol, which has almost totally supplanted older choices (eg, testosterone ointment).

HISTORY

A 59-year-old uncircumcised man is referred by his primary care provider for evaluation of what he deems a “yeast infection” of the distal penis and foreskin. Numerous OTC creams (eg, tolnaftate, clotrimazole, hydrocortisone cream) have been tried, over a period of months, with no improvement in the condition. Now, the patient is experiencing increasing discomfort, not only with the rash itself, but also with actual urinary obstruction. Urination, he reports, has been “difficult” and “messy.”

EXAMINATION

The patient’s foreskin is bound down so tightly that it cannot be retracted without pain. Only a tiny opening remains through which the patient can urinate (with difficulty). The surface of the foreskin is atrophic, dry, and shiny. There is little, if any, redness or swelling, but focal areas of purpura are noted over the area.

DISCUSSION

Penile conditions are problematic for several reasons, not the least of which is the location. Many clinicians are not inclined to even look at the area, pleading ignorance of what they might see and preferring to stay in the diagnostic dark. It is certainly true that a provider would do well to have some idea of what he/she might see when examining a particular area of the body—a principle that applies just as much to elbows and fingernails as to penises.

This patient’s condition is called balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO), a diagnosis of sufficient obscurity to almost guarantee initial misdiagnosis as “yeast infection” or “herpes.” One treatment failure after another eventually leads to referral to a provider familiar with BXO, which is the male version of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) and usually affects the glans, foreskin, and distal shaft.

The causes of these conditions are as yet unknown. However, much is known about how they present, how they look under a microscope, and how to treat them.

LS&A in women itches terribly and presents with whitish atrophic skin changes that affect the perivaginal and perianal areas, sharply sparing the perineum, which gives it a figure-eight or butterfly look. Localized trauma can produce areas of purpura or even bullae. LS&A is not uncommon in children (females > males), in whom the associated focal purpura can be mistaken for a sign of sexual abuse.

Treatment entails use of the most powerful topical steroid ointments, which are so effective that they have completely replaced previous treatment options (eg, testosterone ointment). While a cure is unlikely, control is a realistic goal. If it is left untreated, not only are affected women miserable, but also the condition can lead to stenosis of the introitus and/or meatal stenosis and eventual urinary blockage.

BXO, as in this case, can also cause urinary obstruction, both from the overlying foreskin and from actual meatal stenosis. This is why advanced cases need referral to urology for possible circumcision. As with many penile diagnoses (eg, squamous cell carcinoma or condyloma), BXO is far more common in the uncircumcised.

Other conditions that belong in the differential include seborrhea, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, candidiasis, Bowen’s disease, and irritant/contact dermatitis. Biopsy is typically needed to confirm the diagnosis.

A more common presentation of BXO is a focally atrophic finish to the glans penis, with whitish highlights and a notably dry feel to the affected skin. But, as in this case, it can also affect the foreskin, leading to inflammation and adhesion of the foreskin to the shaft and glans.

In relatively uncomplicated cases, class 1 steroid ointments, such as clobetasol, are prescribed for twice-daily use in the beginning, with a reduction to once-daily use within about two weeks, and then finally to occasional use as the situation demands. Normally, a class 1 steroid would not be used on a thin-skinned area, but BXO responds quite well to it (and lower-strength steroids usually fail). Once control is achieved, the frequency of application is, of course, limited to as-needed use.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

1. There is a differential for penile conditions that includes a number of items beyond “yeast infection”: squamous cell carcinoma, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, lichen planus, and balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO).

2. Dermatology is the relevant initial specialty for these patients, not urology, although the ultimate resolution for balanitis is often surgical.

3. The female counterpart to BXO is called lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A); it is far more common but equally mysterious to providers unacquainted with it.

4. Biopsy—safe and easy to perform—is often necessary to establish the correct diagnosis. For example, a 3-mm punch biopsy, performed under local anesthesia and closed with a single polyglactin stitch, would provide an adequate specimen. Other things being equal, the use of lidocaine-containing epinephrine is perfectly acceptable (and often necessary!) in this area.

5. BXO/LS&A are now routinely treated with class 1 steroid ointments, such as clobetasol, which has almost totally supplanted older choices (eg, testosterone ointment).

HISTORY

A 59-year-old uncircumcised man is referred by his primary care provider for evaluation of what he deems a “yeast infection” of the distal penis and foreskin. Numerous OTC creams (eg, tolnaftate, clotrimazole, hydrocortisone cream) have been tried, over a period of months, with no improvement in the condition. Now, the patient is experiencing increasing discomfort, not only with the rash itself, but also with actual urinary obstruction. Urination, he reports, has been “difficult” and “messy.”

EXAMINATION

The patient’s foreskin is bound down so tightly that it cannot be retracted without pain. Only a tiny opening remains through which the patient can urinate (with difficulty). The surface of the foreskin is atrophic, dry, and shiny. There is little, if any, redness or swelling, but focal areas of purpura are noted over the area.

DISCUSSION

Penile conditions are problematic for several reasons, not the least of which is the location. Many clinicians are not inclined to even look at the area, pleading ignorance of what they might see and preferring to stay in the diagnostic dark. It is certainly true that a provider would do well to have some idea of what he/she might see when examining a particular area of the body—a principle that applies just as much to elbows and fingernails as to penises.

This patient’s condition is called balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO), a diagnosis of sufficient obscurity to almost guarantee initial misdiagnosis as “yeast infection” or “herpes.” One treatment failure after another eventually leads to referral to a provider familiar with BXO, which is the male version of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) and usually affects the glans, foreskin, and distal shaft.

The causes of these conditions are as yet unknown. However, much is known about how they present, how they look under a microscope, and how to treat them.

LS&A in women itches terribly and presents with whitish atrophic skin changes that affect the perivaginal and perianal areas, sharply sparing the perineum, which gives it a figure-eight or butterfly look. Localized trauma can produce areas of purpura or even bullae. LS&A is not uncommon in children (females > males), in whom the associated focal purpura can be mistaken for a sign of sexual abuse.

Treatment entails use of the most powerful topical steroid ointments, which are so effective that they have completely replaced previous treatment options (eg, testosterone ointment). While a cure is unlikely, control is a realistic goal. If it is left untreated, not only are affected women miserable, but also the condition can lead to stenosis of the introitus and/or meatal stenosis and eventual urinary blockage.

BXO, as in this case, can also cause urinary obstruction, both from the overlying foreskin and from actual meatal stenosis. This is why advanced cases need referral to urology for possible circumcision. As with many penile diagnoses (eg, squamous cell carcinoma or condyloma), BXO is far more common in the uncircumcised.

Other conditions that belong in the differential include seborrhea, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, candidiasis, Bowen’s disease, and irritant/contact dermatitis. Biopsy is typically needed to confirm the diagnosis.

A more common presentation of BXO is a focally atrophic finish to the glans penis, with whitish highlights and a notably dry feel to the affected skin. But, as in this case, it can also affect the foreskin, leading to inflammation and adhesion of the foreskin to the shaft and glans.

In relatively uncomplicated cases, class 1 steroid ointments, such as clobetasol, are prescribed for twice-daily use in the beginning, with a reduction to once-daily use within about two weeks, and then finally to occasional use as the situation demands. Normally, a class 1 steroid would not be used on a thin-skinned area, but BXO responds quite well to it (and lower-strength steroids usually fail). Once control is achieved, the frequency of application is, of course, limited to as-needed use.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

1. There is a differential for penile conditions that includes a number of items beyond “yeast infection”: squamous cell carcinoma, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, lichen planus, and balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO).

2. Dermatology is the relevant initial specialty for these patients, not urology, although the ultimate resolution for balanitis is often surgical.

3. The female counterpart to BXO is called lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A); it is far more common but equally mysterious to providers unacquainted with it.

4. Biopsy—safe and easy to perform—is often necessary to establish the correct diagnosis. For example, a 3-mm punch biopsy, performed under local anesthesia and closed with a single polyglactin stitch, would provide an adequate specimen. Other things being equal, the use of lidocaine-containing epinephrine is perfectly acceptable (and often necessary!) in this area.

5. BXO/LS&A are now routinely treated with class 1 steroid ointments, such as clobetasol, which has almost totally supplanted older choices (eg, testosterone ointment).

Woman with Discomfort and Discoloration on Back

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema ab igne (choice “a”) caused, of course, by the effects of the heating pad. The reticular pattern and acute onset are quite characteristic of this unusual condition.

Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) would not have presented in this reticular pattern and would typically have itched intensely.

Cellulitis (choice “c”) represents a superficial infection usually caused by strep and/or staph. It would not have been reticular, would have been painful, and would have required a break in the skin for the offending organism to gain entrance.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (PVA; choice “d”) describes vascular changes seen focally in patches that evolve slowly over months or even years. It is significant because of its reported potential to evolve into cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; however, PVA does not present with a reticular pattern, nor does it appear acutely.

DISCUSSION

The superficial vascular plexus, configured in a reticular pattern and normally invisible, is sensitive to repeated exposure to the infrared portion of the magnetic spectrum (wavelength 700 to 1,100 nm). This exposure initially produces erythema, which over time turns livid, then permanently hyperpigmented.

Erythema ab igne (EAI) was classically seen in those sitting close to an open fire or stove (producing temperatures of 43°C to 47°C) for extended periods, often for hours each day. With the advent of central heating, other triggers of EAI evolved, including prolonged use of laptop computers, heating fans, and as in this case, heating pads. It can even be due to occupational exposure to intense heat, as with glassblowers, bakers, and steelworkers.

Most of the skin changes seen with EAI resemble those seen with chronic sun damage, including vasodilatation and melanin incontinence with melanophages in the upper dermis.

This particular patient had only one exposure to the heating pad, but had turned it on high and lain on it all night. This produced the changes seen, which will likely become permanently etched in her skin in the exact pattern of the causative heating pad. Months of dexamethasone therapy may also have contributed to the problem, by thinning the patient’s skin enough to render her susceptible to this single exposure to heat.

With EAI patients in general, thought needs to be given to possible underlying issues, such as the source of pain being treated with the heating pad—most commonly, on the low back—or the possible reason for constantly feeling cold, such as anemia or hypothyroidism.

Treatment choices include the application of tretinoin cream or 5-fluorouracil cream, or ablation with laser (YAG, ruby, alexandrite).

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema ab igne (choice “a”) caused, of course, by the effects of the heating pad. The reticular pattern and acute onset are quite characteristic of this unusual condition.

Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) would not have presented in this reticular pattern and would typically have itched intensely.

Cellulitis (choice “c”) represents a superficial infection usually caused by strep and/or staph. It would not have been reticular, would have been painful, and would have required a break in the skin for the offending organism to gain entrance.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (PVA; choice “d”) describes vascular changes seen focally in patches that evolve slowly over months or even years. It is significant because of its reported potential to evolve into cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; however, PVA does not present with a reticular pattern, nor does it appear acutely.

DISCUSSION

The superficial vascular plexus, configured in a reticular pattern and normally invisible, is sensitive to repeated exposure to the infrared portion of the magnetic spectrum (wavelength 700 to 1,100 nm). This exposure initially produces erythema, which over time turns livid, then permanently hyperpigmented.

Erythema ab igne (EAI) was classically seen in those sitting close to an open fire or stove (producing temperatures of 43°C to 47°C) for extended periods, often for hours each day. With the advent of central heating, other triggers of EAI evolved, including prolonged use of laptop computers, heating fans, and as in this case, heating pads. It can even be due to occupational exposure to intense heat, as with glassblowers, bakers, and steelworkers.

Most of the skin changes seen with EAI resemble those seen with chronic sun damage, including vasodilatation and melanin incontinence with melanophages in the upper dermis.

This particular patient had only one exposure to the heating pad, but had turned it on high and lain on it all night. This produced the changes seen, which will likely become permanently etched in her skin in the exact pattern of the causative heating pad. Months of dexamethasone therapy may also have contributed to the problem, by thinning the patient’s skin enough to render her susceptible to this single exposure to heat.

With EAI patients in general, thought needs to be given to possible underlying issues, such as the source of pain being treated with the heating pad—most commonly, on the low back—or the possible reason for constantly feeling cold, such as anemia or hypothyroidism.

Treatment choices include the application of tretinoin cream or 5-fluorouracil cream, or ablation with laser (YAG, ruby, alexandrite).

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema ab igne (choice “a”) caused, of course, by the effects of the heating pad. The reticular pattern and acute onset are quite characteristic of this unusual condition.

Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) would not have presented in this reticular pattern and would typically have itched intensely.

Cellulitis (choice “c”) represents a superficial infection usually caused by strep and/or staph. It would not have been reticular, would have been painful, and would have required a break in the skin for the offending organism to gain entrance.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (PVA; choice “d”) describes vascular changes seen focally in patches that evolve slowly over months or even years. It is significant because of its reported potential to evolve into cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; however, PVA does not present with a reticular pattern, nor does it appear acutely.

DISCUSSION

The superficial vascular plexus, configured in a reticular pattern and normally invisible, is sensitive to repeated exposure to the infrared portion of the magnetic spectrum (wavelength 700 to 1,100 nm). This exposure initially produces erythema, which over time turns livid, then permanently hyperpigmented.

Erythema ab igne (EAI) was classically seen in those sitting close to an open fire or stove (producing temperatures of 43°C to 47°C) for extended periods, often for hours each day. With the advent of central heating, other triggers of EAI evolved, including prolonged use of laptop computers, heating fans, and as in this case, heating pads. It can even be due to occupational exposure to intense heat, as with glassblowers, bakers, and steelworkers.

Most of the skin changes seen with EAI resemble those seen with chronic sun damage, including vasodilatation and melanin incontinence with melanophages in the upper dermis.

This particular patient had only one exposure to the heating pad, but had turned it on high and lain on it all night. This produced the changes seen, which will likely become permanently etched in her skin in the exact pattern of the causative heating pad. Months of dexamethasone therapy may also have contributed to the problem, by thinning the patient’s skin enough to render her susceptible to this single exposure to heat.

With EAI patients in general, thought needs to be given to possible underlying issues, such as the source of pain being treated with the heating pad—most commonly, on the low back—or the possible reason for constantly feeling cold, such as anemia or hypothyroidism.

Treatment choices include the application of tretinoin cream or 5-fluorouracil cream, or ablation with laser (YAG, ruby, alexandrite).

A 42-year-old woman presents with discoloration and discomfort involving her back. The discomfort, which started less than 24 hours ago, is not severe, but she is worried about the changes in color she can see in the mirror. Her history is significant for metastatic melanoma. She has been undergoing treatment with chemotherapy and localized radiation and for several months has been taking systemic steroids for intracerebral edema. Additional history taking reveals that the night before the appearance of the skin changes, she fell asleep lying on a heating pad because she was cold. She denies doing this habitually. Examination reveals a large patch of reticular erythema covering the entire central back, sharply sparing the area under the bra strap. The erythema is bounded laterally by sharply demarcated linear margins that mimic the exact shape and size of the heating pad in question. Focal blisters can be seen within the erythema, but the overall effect is macular (flat). Neither tenderness nor increased warmth is noted on palpation.

Is common problem of aging benign or malignant?

HISTORY

A 61-year-old man is urgently referred to dermatology by his primary care provider, at the request of the patient’s family. During a recent visit, family members happened to see his exposed back, which is covered in lesions. The patient claims the lesions have “been there for years,” growing in size and number. However, his family was greatly alarmed and insisted he seek immediate evaluation.

The patient denies any symptoms associated with the lesions, but does volunteer that they are very much like those his father had as an older man.

DISCUSSION

These are, of course, benign seborrheic keratoses—arguably the single most common problem seen in dermatology offices and the source of much consternation, often to everyone except the patient. Dark, sometimes large, often numerous, they look worrisome. But what are they, exactly?

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are benign epidermal excrescences that exhibit a variety of colors and finishes. Varying greatly in size, the typical SK is about a centimeter in diameter, papular to nodular, and tan to grayish brown, with a rough, friable surface. Though little (if any) evidence proves that sun causes them, they tend to appear on the sun-exposed skin of patients ages 50 and older. However, I’ve seen them on patients in their 30s. SKs larger than 10 cm are not unusual, especially on the mid-trunk.

Not everyone develops as many lesions as this patient, but multiple SKs are the rule rather than the exception. Many patients mislabel them as “age spots,” “liver spots,” or “barnacles.” But just as many know that development of SKs is probably hereditary in nature; patients often recall seeing them on their parents or grandparents. Hardly anyone is pleased when they appear, though they are an inevitable consequence of aging for most of us.

The provider’s role, of course, is to distinguish benign from malignant, and that task isn’t always easy. But there are ways to make sure an SK is just that, and not something dangerous.

First of all, anytime you see a multitude of similar lesions that have been present, unchanged, for extended periods on older patients, it’s likely they’re benign.

Next, the “stuck-on” (epidermal) nature of SKs is a very reassuring sign of benignancy. SKs are rough, warty, and dry and clearly develop on the surface of the skin. Their appearance is in sharp contrast to the intradermal nature of, say, melanoma, which may have a raised portion (though at least 80% of melanomas are essentially flat) but cannot be scraped off. Patients will often comment that they’re able to peel SKs off with minor trauma, something one cannot do to a malignant lesion.

Third, on close inspection of SKs, tiny comedone-like pores can be seen scattered over their surface, a feature accentuated by application of liquid nitrogen (which is thus diagnostic as well as therapeutic).

Finally, the application of liquid nitrogen also highlights another indication of the benignancy of SKs: Since SKs have almost no superficial vasculature, they are relatively cool, and when treated with liquid nitrogen, the white color that results persists for several seconds longer than in normal well-vascularized skin or in most melanomas.

This may sound like trivia to the unwary. Unfortunately, there is no rule that says a melanoma cannot develop in the midst of numerous SKs, or even concurrent with an SK. So it does pay to “stay awake” while freezing SKs.

SKs are common on the trunk, arms (especially the triceps), face, scalp, and legs. On the latter, which have fewer oil glands, SKs tend to be drier and whiter. On the face, where sebum is relatively abundant, SKs can be quite dark and shiny. SKs are also relatively common on areas that never see the sun, such as genitals, but they spare the palms and soles, preferring the company of hair follicles.

Biopsy is often required to rule out the other items in the differential, such as melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, Bowen’s disease, angiokeratoma, and warts.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

1. Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are, by far, the most common benign skin lesions seen in dermatology.

2. The fact that they appear in large numbers speaks loudly to their benignancy, other things being equal (older patient, sun-exposed skin, unchanging nature).

3. The color of SKs can vary a great deal—from orange to brown, gray, or tan to black—in part related to their location.

4. Liquid nitrogen treatment is not only highly effective in treating SKs, but serves as a useful diagnostic tool in two ways: First, it highlights the surface pore-like structures, called horn pseudocysts, which are pathognomic for SKs. Second, the frozen SK stays white considerably longer than relatively well-vascularized normal skin or melanoma, which thaw almost instantly.

5. When in doubt, a deep shave biopsy (“saucerization”) is indicated.

HISTORY

A 61-year-old man is urgently referred to dermatology by his primary care provider, at the request of the patient’s family. During a recent visit, family members happened to see his exposed back, which is covered in lesions. The patient claims the lesions have “been there for years,” growing in size and number. However, his family was greatly alarmed and insisted he seek immediate evaluation.

The patient denies any symptoms associated with the lesions, but does volunteer that they are very much like those his father had as an older man.

DISCUSSION

These are, of course, benign seborrheic keratoses—arguably the single most common problem seen in dermatology offices and the source of much consternation, often to everyone except the patient. Dark, sometimes large, often numerous, they look worrisome. But what are they, exactly?

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are benign epidermal excrescences that exhibit a variety of colors and finishes. Varying greatly in size, the typical SK is about a centimeter in diameter, papular to nodular, and tan to grayish brown, with a rough, friable surface. Though little (if any) evidence proves that sun causes them, they tend to appear on the sun-exposed skin of patients ages 50 and older. However, I’ve seen them on patients in their 30s. SKs larger than 10 cm are not unusual, especially on the mid-trunk.

Not everyone develops as many lesions as this patient, but multiple SKs are the rule rather than the exception. Many patients mislabel them as “age spots,” “liver spots,” or “barnacles.” But just as many know that development of SKs is probably hereditary in nature; patients often recall seeing them on their parents or grandparents. Hardly anyone is pleased when they appear, though they are an inevitable consequence of aging for most of us.

The provider’s role, of course, is to distinguish benign from malignant, and that task isn’t always easy. But there are ways to make sure an SK is just that, and not something dangerous.

First of all, anytime you see a multitude of similar lesions that have been present, unchanged, for extended periods on older patients, it’s likely they’re benign.

Next, the “stuck-on” (epidermal) nature of SKs is a very reassuring sign of benignancy. SKs are rough, warty, and dry and clearly develop on the surface of the skin. Their appearance is in sharp contrast to the intradermal nature of, say, melanoma, which may have a raised portion (though at least 80% of melanomas are essentially flat) but cannot be scraped off. Patients will often comment that they’re able to peel SKs off with minor trauma, something one cannot do to a malignant lesion.

Third, on close inspection of SKs, tiny comedone-like pores can be seen scattered over their surface, a feature accentuated by application of liquid nitrogen (which is thus diagnostic as well as therapeutic).

Finally, the application of liquid nitrogen also highlights another indication of the benignancy of SKs: Since SKs have almost no superficial vasculature, they are relatively cool, and when treated with liquid nitrogen, the white color that results persists for several seconds longer than in normal well-vascularized skin or in most melanomas.

This may sound like trivia to the unwary. Unfortunately, there is no rule that says a melanoma cannot develop in the midst of numerous SKs, or even concurrent with an SK. So it does pay to “stay awake” while freezing SKs.

SKs are common on the trunk, arms (especially the triceps), face, scalp, and legs. On the latter, which have fewer oil glands, SKs tend to be drier and whiter. On the face, where sebum is relatively abundant, SKs can be quite dark and shiny. SKs are also relatively common on areas that never see the sun, such as genitals, but they spare the palms and soles, preferring the company of hair follicles.

Biopsy is often required to rule out the other items in the differential, such as melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, Bowen’s disease, angiokeratoma, and warts.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

1. Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are, by far, the most common benign skin lesions seen in dermatology.

2. The fact that they appear in large numbers speaks loudly to their benignancy, other things being equal (older patient, sun-exposed skin, unchanging nature).

3. The color of SKs can vary a great deal—from orange to brown, gray, or tan to black—in part related to their location.

4. Liquid nitrogen treatment is not only highly effective in treating SKs, but serves as a useful diagnostic tool in two ways: First, it highlights the surface pore-like structures, called horn pseudocysts, which are pathognomic for SKs. Second, the frozen SK stays white considerably longer than relatively well-vascularized normal skin or melanoma, which thaw almost instantly.

5. When in doubt, a deep shave biopsy (“saucerization”) is indicated.

HISTORY

A 61-year-old man is urgently referred to dermatology by his primary care provider, at the request of the patient’s family. During a recent visit, family members happened to see his exposed back, which is covered in lesions. The patient claims the lesions have “been there for years,” growing in size and number. However, his family was greatly alarmed and insisted he seek immediate evaluation.

The patient denies any symptoms associated with the lesions, but does volunteer that they are very much like those his father had as an older man.

DISCUSSION

These are, of course, benign seborrheic keratoses—arguably the single most common problem seen in dermatology offices and the source of much consternation, often to everyone except the patient. Dark, sometimes large, often numerous, they look worrisome. But what are they, exactly?

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are benign epidermal excrescences that exhibit a variety of colors and finishes. Varying greatly in size, the typical SK is about a centimeter in diameter, papular to nodular, and tan to grayish brown, with a rough, friable surface. Though little (if any) evidence proves that sun causes them, they tend to appear on the sun-exposed skin of patients ages 50 and older. However, I’ve seen them on patients in their 30s. SKs larger than 10 cm are not unusual, especially on the mid-trunk.

Not everyone develops as many lesions as this patient, but multiple SKs are the rule rather than the exception. Many patients mislabel them as “age spots,” “liver spots,” or “barnacles.” But just as many know that development of SKs is probably hereditary in nature; patients often recall seeing them on their parents or grandparents. Hardly anyone is pleased when they appear, though they are an inevitable consequence of aging for most of us.

The provider’s role, of course, is to distinguish benign from malignant, and that task isn’t always easy. But there are ways to make sure an SK is just that, and not something dangerous.

First of all, anytime you see a multitude of similar lesions that have been present, unchanged, for extended periods on older patients, it’s likely they’re benign.

Next, the “stuck-on” (epidermal) nature of SKs is a very reassuring sign of benignancy. SKs are rough, warty, and dry and clearly develop on the surface of the skin. Their appearance is in sharp contrast to the intradermal nature of, say, melanoma, which may have a raised portion (though at least 80% of melanomas are essentially flat) but cannot be scraped off. Patients will often comment that they’re able to peel SKs off with minor trauma, something one cannot do to a malignant lesion.

Third, on close inspection of SKs, tiny comedone-like pores can be seen scattered over their surface, a feature accentuated by application of liquid nitrogen (which is thus diagnostic as well as therapeutic).

Finally, the application of liquid nitrogen also highlights another indication of the benignancy of SKs: Since SKs have almost no superficial vasculature, they are relatively cool, and when treated with liquid nitrogen, the white color that results persists for several seconds longer than in normal well-vascularized skin or in most melanomas.

This may sound like trivia to the unwary. Unfortunately, there is no rule that says a melanoma cannot develop in the midst of numerous SKs, or even concurrent with an SK. So it does pay to “stay awake” while freezing SKs.

SKs are common on the trunk, arms (especially the triceps), face, scalp, and legs. On the latter, which have fewer oil glands, SKs tend to be drier and whiter. On the face, where sebum is relatively abundant, SKs can be quite dark and shiny. SKs are also relatively common on areas that never see the sun, such as genitals, but they spare the palms and soles, preferring the company of hair follicles.

Biopsy is often required to rule out the other items in the differential, such as melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, Bowen’s disease, angiokeratoma, and warts.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

1. Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are, by far, the most common benign skin lesions seen in dermatology.

2. The fact that they appear in large numbers speaks loudly to their benignancy, other things being equal (older patient, sun-exposed skin, unchanging nature).

3. The color of SKs can vary a great deal—from orange to brown, gray, or tan to black—in part related to their location.

4. Liquid nitrogen treatment is not only highly effective in treating SKs, but serves as a useful diagnostic tool in two ways: First, it highlights the surface pore-like structures, called horn pseudocysts, which are pathognomic for SKs. Second, the frozen SK stays white considerably longer than relatively well-vascularized normal skin or melanoma, which thaw almost instantly.

5. When in doubt, a deep shave biopsy (“saucerization”) is indicated.

Inexperienced runner develops leg rash

HISTORY

A 16-year-old high school student gets a sudden burst of energy one spring day and decides to become a runner, joining her friends in a 2K fundraiser one Saturday morning. That night, she is quite sore; the next morning, she has so much pain in her shins she can hardly walk. Her mother suggests she apply ice packs to her legs, which she does, using elastic bandages to hold them in place for several hours, until the ice cubes melt.

As intended, the pain in her legs feels better. But as her legs rewarm, a rash appears where the ice packs contacted the skin. The itching and stinging are intense enough to alarm the girl’s mother, who calls and obtains a same-day appointment with dermatology. Topical diphenhydramine cream and calamine lotion, applied at home, are no help.

EXAMINATION

The area on each leg where the ice packs contacted the skin is covered by a solid orange-red wheal, the periphery of which is ringed by a faint whitish halo. There is no increase in warmth or tenderness elicited on palpation. No ecchymosis is seen, and the wheals are highly blanchable on deeper palpation. No other abnormalities of the skin are observed in this or other locations.

DISCUSSION

Clearly, this condition is urticarial in nature—albeit an unusual form, triggered by cold. Though it appears counterintuitive, cold uriticaria typically appears only on rewarming of the affected area, and is marked by the sudden appearance of “welts” or “hives” that usually clear (with or without treatment) within hours.

Uncomplicated urticaria resolves without leaving any signs (eg, purpura, ecchymosis) that might otherwise suggest the presence of a vasculitic component, such as that seen with lupus or other autoimmune diseases. Blanchability on digital pressure is one way to confirm benignancy, since blood tends to leak from vessels damaged by vasculitis, emptying into the surrounding interstitial spaces and presenting as nonblanchable petichiae, purpura, or ecchymosis.

The relatively benign nature of this patient’s urticaria was also suggested by additional history taking, in which she denied having fever, malaise, or arthralgia. These are all symptoms we might have seen with more serious underlying causes.

Cold urticaria is one of the so-called physical urticarias, a group that includes urticaria caused by vibration, pressure, heat, sun, and even exposure to water. Thought to comprise up to 20% of all urticaria, the physical urticarias occur most frequently in persons ages 17 to 40. Dermatographism is the most common form, occurring in the linear track of a vigorous scratch as a wheal that manifests rapidly, lasts a few minutes, then disappears without a trace. Its presence is purposely sought by the examiner to confirm the diagnosis of urticaria (most often the chronic idiopathic variety).

Primary cold urticaria (PCU), while usually localized and mild, can be accompanied by respiratory and cardiovascular compromise. Affected patients can develop fatal shock when exposed to cold water. Far more frequently, PCU is merely initially puzzling, then annoying. About 50% of patients with PCU see their condition cleared permanently after a few months, but the rest will experience periodic recurrences.

Besides avoidance of cold, PCU can be treated with antihistamines such as doxepin, cyproheptadine, or cetirizine. More stubborn, severe cases can be treated by desensitization: repeated, increased exposure to cold applied to increasing areas of the body over time. In cases where PCU is suspected but not seen, the clinician may apply ice to a small area of skin for 5 to 20 minutes, inducing a diagnostic wheal.

Secondary cold urticaria is associated with an underlying systemic disease, such as cryoglobulinemia, and patients are likely to experience symptoms such as headache, hypotension, laryngeal edema, and syncope. The ice-cube test is not advisable for these patients, lest tissue ischemia and vascular occlusion result.

Familial cold urticaria is also accompanied by systemic symptoms, as well as a positive family history and lesions with cyanotic centers and surrounding white halos. Referral of these atypical patients to allergy/immunology is mandatory.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

1. Most forms of urticaria are uniquely evanescent (ie, they arise suddenly and resolve almost as quickly), leaving little if any residual skin changes.

2. The wheals of cold urticaria appear on rewarming of the area.

3. Wheals are also known as welts. The latter are often mistakenly termed whelps (which, according to the dictionary, refers to a puppy or kitten).

4. Cold urticaria is one of the so-called physical urticarias, other forms of which can be triggered by the pressure from shoes, heat, vibration, or even exposure to water.

HISTORY

A 16-year-old high school student gets a sudden burst of energy one spring day and decides to become a runner, joining her friends in a 2K fundraiser one Saturday morning. That night, she is quite sore; the next morning, she has so much pain in her shins she can hardly walk. Her mother suggests she apply ice packs to her legs, which she does, using elastic bandages to hold them in place for several hours, until the ice cubes melt.

As intended, the pain in her legs feels better. But as her legs rewarm, a rash appears where the ice packs contacted the skin. The itching and stinging are intense enough to alarm the girl’s mother, who calls and obtains a same-day appointment with dermatology. Topical diphenhydramine cream and calamine lotion, applied at home, are no help.

EXAMINATION

The area on each leg where the ice packs contacted the skin is covered by a solid orange-red wheal, the periphery of which is ringed by a faint whitish halo. There is no increase in warmth or tenderness elicited on palpation. No ecchymosis is seen, and the wheals are highly blanchable on deeper palpation. No other abnormalities of the skin are observed in this or other locations.

DISCUSSION

Clearly, this condition is urticarial in nature—albeit an unusual form, triggered by cold. Though it appears counterintuitive, cold uriticaria typically appears only on rewarming of the affected area, and is marked by the sudden appearance of “welts” or “hives” that usually clear (with or without treatment) within hours.

Uncomplicated urticaria resolves without leaving any signs (eg, purpura, ecchymosis) that might otherwise suggest the presence of a vasculitic component, such as that seen with lupus or other autoimmune diseases. Blanchability on digital pressure is one way to confirm benignancy, since blood tends to leak from vessels damaged by vasculitis, emptying into the surrounding interstitial spaces and presenting as nonblanchable petichiae, purpura, or ecchymosis.

The relatively benign nature of this patient’s urticaria was also suggested by additional history taking, in which she denied having fever, malaise, or arthralgia. These are all symptoms we might have seen with more serious underlying causes.

Cold urticaria is one of the so-called physical urticarias, a group that includes urticaria caused by vibration, pressure, heat, sun, and even exposure to water. Thought to comprise up to 20% of all urticaria, the physical urticarias occur most frequently in persons ages 17 to 40. Dermatographism is the most common form, occurring in the linear track of a vigorous scratch as a wheal that manifests rapidly, lasts a few minutes, then disappears without a trace. Its presence is purposely sought by the examiner to confirm the diagnosis of urticaria (most often the chronic idiopathic variety).

Primary cold urticaria (PCU), while usually localized and mild, can be accompanied by respiratory and cardiovascular compromise. Affected patients can develop fatal shock when exposed to cold water. Far more frequently, PCU is merely initially puzzling, then annoying. About 50% of patients with PCU see their condition cleared permanently after a few months, but the rest will experience periodic recurrences.

Besides avoidance of cold, PCU can be treated with antihistamines such as doxepin, cyproheptadine, or cetirizine. More stubborn, severe cases can be treated by desensitization: repeated, increased exposure to cold applied to increasing areas of the body over time. In cases where PCU is suspected but not seen, the clinician may apply ice to a small area of skin for 5 to 20 minutes, inducing a diagnostic wheal.

Secondary cold urticaria is associated with an underlying systemic disease, such as cryoglobulinemia, and patients are likely to experience symptoms such as headache, hypotension, laryngeal edema, and syncope. The ice-cube test is not advisable for these patients, lest tissue ischemia and vascular occlusion result.

Familial cold urticaria is also accompanied by systemic symptoms, as well as a positive family history and lesions with cyanotic centers and surrounding white halos. Referral of these atypical patients to allergy/immunology is mandatory.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

1. Most forms of urticaria are uniquely evanescent (ie, they arise suddenly and resolve almost as quickly), leaving little if any residual skin changes.

2. The wheals of cold urticaria appear on rewarming of the area.

3. Wheals are also known as welts. The latter are often mistakenly termed whelps (which, according to the dictionary, refers to a puppy or kitten).

4. Cold urticaria is one of the so-called physical urticarias, other forms of which can be triggered by the pressure from shoes, heat, vibration, or even exposure to water.

HISTORY

A 16-year-old high school student gets a sudden burst of energy one spring day and decides to become a runner, joining her friends in a 2K fundraiser one Saturday morning. That night, she is quite sore; the next morning, she has so much pain in her shins she can hardly walk. Her mother suggests she apply ice packs to her legs, which she does, using elastic bandages to hold them in place for several hours, until the ice cubes melt.

As intended, the pain in her legs feels better. But as her legs rewarm, a rash appears where the ice packs contacted the skin. The itching and stinging are intense enough to alarm the girl’s mother, who calls and obtains a same-day appointment with dermatology. Topical diphenhydramine cream and calamine lotion, applied at home, are no help.

EXAMINATION

The area on each leg where the ice packs contacted the skin is covered by a solid orange-red wheal, the periphery of which is ringed by a faint whitish halo. There is no increase in warmth or tenderness elicited on palpation. No ecchymosis is seen, and the wheals are highly blanchable on deeper palpation. No other abnormalities of the skin are observed in this or other locations.

DISCUSSION

Clearly, this condition is urticarial in nature—albeit an unusual form, triggered by cold. Though it appears counterintuitive, cold uriticaria typically appears only on rewarming of the affected area, and is marked by the sudden appearance of “welts” or “hives” that usually clear (with or without treatment) within hours.

Uncomplicated urticaria resolves without leaving any signs (eg, purpura, ecchymosis) that might otherwise suggest the presence of a vasculitic component, such as that seen with lupus or other autoimmune diseases. Blanchability on digital pressure is one way to confirm benignancy, since blood tends to leak from vessels damaged by vasculitis, emptying into the surrounding interstitial spaces and presenting as nonblanchable petichiae, purpura, or ecchymosis.

The relatively benign nature of this patient’s urticaria was also suggested by additional history taking, in which she denied having fever, malaise, or arthralgia. These are all symptoms we might have seen with more serious underlying causes.

Cold urticaria is one of the so-called physical urticarias, a group that includes urticaria caused by vibration, pressure, heat, sun, and even exposure to water. Thought to comprise up to 20% of all urticaria, the physical urticarias occur most frequently in persons ages 17 to 40. Dermatographism is the most common form, occurring in the linear track of a vigorous scratch as a wheal that manifests rapidly, lasts a few minutes, then disappears without a trace. Its presence is purposely sought by the examiner to confirm the diagnosis of urticaria (most often the chronic idiopathic variety).

Primary cold urticaria (PCU), while usually localized and mild, can be accompanied by respiratory and cardiovascular compromise. Affected patients can develop fatal shock when exposed to cold water. Far more frequently, PCU is merely initially puzzling, then annoying. About 50% of patients with PCU see their condition cleared permanently after a few months, but the rest will experience periodic recurrences.

Besides avoidance of cold, PCU can be treated with antihistamines such as doxepin, cyproheptadine, or cetirizine. More stubborn, severe cases can be treated by desensitization: repeated, increased exposure to cold applied to increasing areas of the body over time. In cases where PCU is suspected but not seen, the clinician may apply ice to a small area of skin for 5 to 20 minutes, inducing a diagnostic wheal.

Secondary cold urticaria is associated with an underlying systemic disease, such as cryoglobulinemia, and patients are likely to experience symptoms such as headache, hypotension, laryngeal edema, and syncope. The ice-cube test is not advisable for these patients, lest tissue ischemia and vascular occlusion result.

Familial cold urticaria is also accompanied by systemic symptoms, as well as a positive family history and lesions with cyanotic centers and surrounding white halos. Referral of these atypical patients to allergy/immunology is mandatory.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

1. Most forms of urticaria are uniquely evanescent (ie, they arise suddenly and resolve almost as quickly), leaving little if any residual skin changes.

2. The wheals of cold urticaria appear on rewarming of the area.

3. Wheals are also known as welts. The latter are often mistakenly termed whelps (which, according to the dictionary, refers to a puppy or kitten).

4. Cold urticaria is one of the so-called physical urticarias, other forms of which can be triggered by the pressure from shoes, heat, vibration, or even exposure to water.

Skin Change and Fatigue Forces Woman to Take Leave of Absence

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatomyositis (choice “c”), thought to be a vasculopathy mediated by the deposition of complement and lysis of capillaries in skin and muscle.

Carcinoid (choice “a”) is a rare tumor that can release vasoactive peptides, which cause episodic flushing, and if prolonged, can cause permanent changes in the skin. But carcinoid involves neither muscle weakness nor the particular skin changes seen with dermatomyositis.

Lupus erythematosus (choice “b”) can present with similar symptoms. However, when it affects the fingers, it specifically affects the interphalangeal skin, sharply sparing the knuckles. Both lupus erythematosus and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD; choice “d”) can present with similar changes in the cuticles, but neither present with such profound muscle weakness.

DISCUSSION

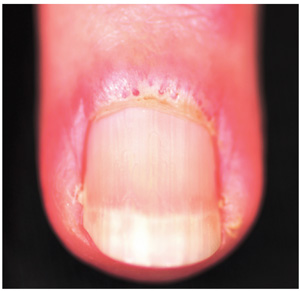

Dermatomyositis is one of three main conditions that present with characteristic changes in the cuticular vasculature (the other two being scleroderma and MCTD). The definitive diagnosis is usually made by a rheumatologist, who is able to distinguish dermatomyositis from the rest of the differential—a process that can be rather complex.

The first diagnostic step is to identify the changes to the cuticular vasculature. These must be specifically sought; they are not always as obvious as in this case. Fortunately, magnification can easily be carried out with either an ophthalmoscope or dermatoscope, an examination enhanced by the application of oil first.

These findings, along with sunburn-like eruptions on the neck and face, should prompt laboratory testing. Significant results would include a positive antinuclear antibody test and elevations of the muscle enzymes creatine kinase and aldolase. Skin biopsy is helpful, though not diagnostic by itself. Additional studies might include a barium swallow, which would show weak pharyngeal muscles, and either an electromyography or MRI, which would demonstrate characteristic muscle changes secondary to inflammation.

Perhaps the most important aspect of dermatomyositis is its connection to cancer. A significant percentage of adults diagnosed with dermatomyositis will also have an associated and often occult malignancy, which may be found before, during, or after the diagnosis of dermatomyositis. (Juvenile dermatomyositis is not associated with malignancy.)

Patient age, constitutional symptoms, rapidity of onset, high level of serum muscle enzymes, grossly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and severity of dermatomyositis are all factors that would prompt an aggressive search for malignancies, the types of which mirror those seen in the general population. In such cases, surgical and/or medical cures of causative cancer usually stop the dermatomyositis as well.

The workup on this particular patient is still underway, but she is already responding to therapy with prednisone (1 mg/kg/d), to be taken until muscle enzymes are normal. This can take months, with dosage reduced as symptoms respond. Steroid-sparing agents, such as methotrexate or azathioprine, are often begun as prednisone levels are reduced.

SUGGESTED READING

James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Saunders; 2005:166-170.

Bergman R, Sharony L, Schapira D, et al. The handheld dermatoscope as a nail-fold capillaroscopic instrument. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(8): 1027-1030.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatomyositis (choice “c”), thought to be a vasculopathy mediated by the deposition of complement and lysis of capillaries in skin and muscle.

Carcinoid (choice “a”) is a rare tumor that can release vasoactive peptides, which cause episodic flushing, and if prolonged, can cause permanent changes in the skin. But carcinoid involves neither muscle weakness nor the particular skin changes seen with dermatomyositis.

Lupus erythematosus (choice “b”) can present with similar symptoms. However, when it affects the fingers, it specifically affects the interphalangeal skin, sharply sparing the knuckles. Both lupus erythematosus and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD; choice “d”) can present with similar changes in the cuticles, but neither present with such profound muscle weakness.

DISCUSSION

Dermatomyositis is one of three main conditions that present with characteristic changes in the cuticular vasculature (the other two being scleroderma and MCTD). The definitive diagnosis is usually made by a rheumatologist, who is able to distinguish dermatomyositis from the rest of the differential—a process that can be rather complex.

The first diagnostic step is to identify the changes to the cuticular vasculature. These must be specifically sought; they are not always as obvious as in this case. Fortunately, magnification can easily be carried out with either an ophthalmoscope or dermatoscope, an examination enhanced by the application of oil first.

These findings, along with sunburn-like eruptions on the neck and face, should prompt laboratory testing. Significant results would include a positive antinuclear antibody test and elevations of the muscle enzymes creatine kinase and aldolase. Skin biopsy is helpful, though not diagnostic by itself. Additional studies might include a barium swallow, which would show weak pharyngeal muscles, and either an electromyography or MRI, which would demonstrate characteristic muscle changes secondary to inflammation.

Perhaps the most important aspect of dermatomyositis is its connection to cancer. A significant percentage of adults diagnosed with dermatomyositis will also have an associated and often occult malignancy, which may be found before, during, or after the diagnosis of dermatomyositis. (Juvenile dermatomyositis is not associated with malignancy.)

Patient age, constitutional symptoms, rapidity of onset, high level of serum muscle enzymes, grossly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and severity of dermatomyositis are all factors that would prompt an aggressive search for malignancies, the types of which mirror those seen in the general population. In such cases, surgical and/or medical cures of causative cancer usually stop the dermatomyositis as well.

The workup on this particular patient is still underway, but she is already responding to therapy with prednisone (1 mg/kg/d), to be taken until muscle enzymes are normal. This can take months, with dosage reduced as symptoms respond. Steroid-sparing agents, such as methotrexate or azathioprine, are often begun as prednisone levels are reduced.

SUGGESTED READING

James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Saunders; 2005:166-170.

Bergman R, Sharony L, Schapira D, et al. The handheld dermatoscope as a nail-fold capillaroscopic instrument. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(8): 1027-1030.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatomyositis (choice “c”), thought to be a vasculopathy mediated by the deposition of complement and lysis of capillaries in skin and muscle.

Carcinoid (choice “a”) is a rare tumor that can release vasoactive peptides, which cause episodic flushing, and if prolonged, can cause permanent changes in the skin. But carcinoid involves neither muscle weakness nor the particular skin changes seen with dermatomyositis.

Lupus erythematosus (choice “b”) can present with similar symptoms. However, when it affects the fingers, it specifically affects the interphalangeal skin, sharply sparing the knuckles. Both lupus erythematosus and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD; choice “d”) can present with similar changes in the cuticles, but neither present with such profound muscle weakness.

DISCUSSION

Dermatomyositis is one of three main conditions that present with characteristic changes in the cuticular vasculature (the other two being scleroderma and MCTD). The definitive diagnosis is usually made by a rheumatologist, who is able to distinguish dermatomyositis from the rest of the differential—a process that can be rather complex.

The first diagnostic step is to identify the changes to the cuticular vasculature. These must be specifically sought; they are not always as obvious as in this case. Fortunately, magnification can easily be carried out with either an ophthalmoscope or dermatoscope, an examination enhanced by the application of oil first.

These findings, along with sunburn-like eruptions on the neck and face, should prompt laboratory testing. Significant results would include a positive antinuclear antibody test and elevations of the muscle enzymes creatine kinase and aldolase. Skin biopsy is helpful, though not diagnostic by itself. Additional studies might include a barium swallow, which would show weak pharyngeal muscles, and either an electromyography or MRI, which would demonstrate characteristic muscle changes secondary to inflammation.

Perhaps the most important aspect of dermatomyositis is its connection to cancer. A significant percentage of adults diagnosed with dermatomyositis will also have an associated and often occult malignancy, which may be found before, during, or after the diagnosis of dermatomyositis. (Juvenile dermatomyositis is not associated with malignancy.)

Patient age, constitutional symptoms, rapidity of onset, high level of serum muscle enzymes, grossly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and severity of dermatomyositis are all factors that would prompt an aggressive search for malignancies, the types of which mirror those seen in the general population. In such cases, surgical and/or medical cures of causative cancer usually stop the dermatomyositis as well.

The workup on this particular patient is still underway, but she is already responding to therapy with prednisone (1 mg/kg/d), to be taken until muscle enzymes are normal. This can take months, with dosage reduced as symptoms respond. Steroid-sparing agents, such as methotrexate or azathioprine, are often begun as prednisone levels are reduced.

SUGGESTED READING

James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Saunders; 2005:166-170.

Bergman R, Sharony L, Schapira D, et al. The handheld dermatoscope as a nail-fold capillaroscopic instrument. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(8): 1027-1030.

A three-month history of muscle weakness, fatigue, and skin changes prompts a 59-year-old woman to self-refer to dermatology. Otherwise healthy prior to the onset of these symptoms, she has had to take a leave of absence from work due to her inability to carry out her duties, which include light lifting and prolonged periods of time on her feet as a clerk in a pharmacy. She first consulted her primary care provider (PCP), who informed her that she was not anemic and did not have thyroid disease; the PCP felt that stress was probably a factor. She then purchased a number of products from her health food store, which she started taking until the skin on her hands began to change. On examination, atrophic pinkish red planar plaques are noted on 10/10 fingers, confined to the dorsal aspects of her joints and sharply sparing the interphalangeal spaces. The cuticles demonstrate the presence of dilated and irregularly shaped capillary loops. Several of her cuticles are also overgrown and frayed. Examination of the rest of the patient’s skin reveals a blanchable, faintly sunburned appearance to her anterior neck.

Facial lesion in child cause for concern?

HISTORY

Lesions on children are the source of much consternation for parents and providers, and understandably so. While the vast majority are safe, there are lesions and conditions that are problematic on a number of levels.

Take this case of a 2½–year-old boy whose parents bring him in for evaluation of the lesion on his cheek. First noticed when the child was an infant, it has grown steadily to its present size (about 5 mm). The child is otherwise healthy, and there is no family history of skin disease or cancer.

The parents indicate their intention to have the lesion removed at the current visit, not realizing what that will actually entail in terms of pain and potential for scarring—not to mention the patient’s willingness to undergo the procedure. All they really know is that the lesion is there, and they want it gone.

On examination, the lesion is papular and black, with some unevenness of color. On palpation, it is firm and nontender, with an apparent intradermal component.

DISCUSSION

This case raises several points—but as to the lesion itself, although it is quite likely safe, it is worrisome, unsightly, and probably “needs to go.”

Based on its appearance and the patient’s age, the lesion probably represents a variant of Spitz tumor, called a Reed tumor or pigmented Spitz tumor. This is a benign lesion that not only resembles melanoma clinically, but also demonstrates microscopic histologic features suggestive of melanoma. Fortunately, it can usually be differentiated from melanoma with special stains and recognition of certain histologic features.

Originally called juvenile melanoma or prepubertal melanoma, these melanocytic nevi were assumed to be malignant; their discovery invariably led to draconian surgical procedures and dire prognoses. In 1947, a Cincinnati pathologist, Dr Sophie Spitz, noticed that none of the “juvenile melanoma” patients she had been involved with had ever shown any signs of cancer. This observation led her to conduct a study of several of these patients, in which it was confirmed that, in fact, these lesions were benign despite their appearance. She went on to determine the histologic differences of these lesions, publishing the results of that work in 1948. It was only after her death at age 46, from colon cancer, that these lesions became known as Spitz tumors, in her honor.

Since then, several variants of this lesion have been described, including the pigmented version described in this case. Another is called spitzoid melanoma—that is, melanoma that demonstrates some of the clinical and histologic features of Spitz tumors but behaves in a malignant fashion. Because of this, and because they mostly occur on children, they are usually removed with modest but definite margins. To this day, differentiation cannot be made on histologic bases alone, adding a significant degree of concern to the diagnosis (although only a tiny percentage ever exhibit malignant behavior).

The more common variety of Spitz tumors, also called epithelioid or spindle cell tumors, are much lighter in color (tan to red to brown) and tend to develop on the face, head, and neck, usually as solitary lesions presenting with an initial phase of rapid growth. The diagnosis of Spitz tumor in an older, sun-damaged patient is considered suspect, with the lesion treated as if it were melanoma.

Besides melanoma, the differential diagnosis for Spitz tumors includes compound nevus, juvenile xanthogranuloma, wart, and basal cell carcinoma.

This patient’s lesion clearly needs excision with clear margins. Given the patient’s age and the location of the lesion, the patient was referred to a plastic surgeon, who in turn will send the specimen to a dermatopathologist experienced in dealing with this tumor.

All this was carefully explained to the family, with reassurance of the probable benignancy of the lesion but also education about the need for continued vigilance. Following surgery, the patient will be followed by dermatology and watched for signs of malignant behavior at the surgical site and in relevant nodal drainage.

HISTORY

Lesions on children are the source of much consternation for parents and providers, and understandably so. While the vast majority are safe, there are lesions and conditions that are problematic on a number of levels.

Take this case of a 2½–year-old boy whose parents bring him in for evaluation of the lesion on his cheek. First noticed when the child was an infant, it has grown steadily to its present size (about 5 mm). The child is otherwise healthy, and there is no family history of skin disease or cancer.

The parents indicate their intention to have the lesion removed at the current visit, not realizing what that will actually entail in terms of pain and potential for scarring—not to mention the patient’s willingness to undergo the procedure. All they really know is that the lesion is there, and they want it gone.

On examination, the lesion is papular and black, with some unevenness of color. On palpation, it is firm and nontender, with an apparent intradermal component.

DISCUSSION

This case raises several points—but as to the lesion itself, although it is quite likely safe, it is worrisome, unsightly, and probably “needs to go.”

Based on its appearance and the patient’s age, the lesion probably represents a variant of Spitz tumor, called a Reed tumor or pigmented Spitz tumor. This is a benign lesion that not only resembles melanoma clinically, but also demonstrates microscopic histologic features suggestive of melanoma. Fortunately, it can usually be differentiated from melanoma with special stains and recognition of certain histologic features.

Originally called juvenile melanoma or prepubertal melanoma, these melanocytic nevi were assumed to be malignant; their discovery invariably led to draconian surgical procedures and dire prognoses. In 1947, a Cincinnati pathologist, Dr Sophie Spitz, noticed that none of the “juvenile melanoma” patients she had been involved with had ever shown any signs of cancer. This observation led her to conduct a study of several of these patients, in which it was confirmed that, in fact, these lesions were benign despite their appearance. She went on to determine the histologic differences of these lesions, publishing the results of that work in 1948. It was only after her death at age 46, from colon cancer, that these lesions became known as Spitz tumors, in her honor.

Since then, several variants of this lesion have been described, including the pigmented version described in this case. Another is called spitzoid melanoma—that is, melanoma that demonstrates some of the clinical and histologic features of Spitz tumors but behaves in a malignant fashion. Because of this, and because they mostly occur on children, they are usually removed with modest but definite margins. To this day, differentiation cannot be made on histologic bases alone, adding a significant degree of concern to the diagnosis (although only a tiny percentage ever exhibit malignant behavior).

The more common variety of Spitz tumors, also called epithelioid or spindle cell tumors, are much lighter in color (tan to red to brown) and tend to develop on the face, head, and neck, usually as solitary lesions presenting with an initial phase of rapid growth. The diagnosis of Spitz tumor in an older, sun-damaged patient is considered suspect, with the lesion treated as if it were melanoma.

Besides melanoma, the differential diagnosis for Spitz tumors includes compound nevus, juvenile xanthogranuloma, wart, and basal cell carcinoma.

This patient’s lesion clearly needs excision with clear margins. Given the patient’s age and the location of the lesion, the patient was referred to a plastic surgeon, who in turn will send the specimen to a dermatopathologist experienced in dealing with this tumor.

All this was carefully explained to the family, with reassurance of the probable benignancy of the lesion but also education about the need for continued vigilance. Following surgery, the patient will be followed by dermatology and watched for signs of malignant behavior at the surgical site and in relevant nodal drainage.

HISTORY

Lesions on children are the source of much consternation for parents and providers, and understandably so. While the vast majority are safe, there are lesions and conditions that are problematic on a number of levels.

Take this case of a 2½–year-old boy whose parents bring him in for evaluation of the lesion on his cheek. First noticed when the child was an infant, it has grown steadily to its present size (about 5 mm). The child is otherwise healthy, and there is no family history of skin disease or cancer.

The parents indicate their intention to have the lesion removed at the current visit, not realizing what that will actually entail in terms of pain and potential for scarring—not to mention the patient’s willingness to undergo the procedure. All they really know is that the lesion is there, and they want it gone.

On examination, the lesion is papular and black, with some unevenness of color. On palpation, it is firm and nontender, with an apparent intradermal component.

DISCUSSION

This case raises several points—but as to the lesion itself, although it is quite likely safe, it is worrisome, unsightly, and probably “needs to go.”

Based on its appearance and the patient’s age, the lesion probably represents a variant of Spitz tumor, called a Reed tumor or pigmented Spitz tumor. This is a benign lesion that not only resembles melanoma clinically, but also demonstrates microscopic histologic features suggestive of melanoma. Fortunately, it can usually be differentiated from melanoma with special stains and recognition of certain histologic features.

Originally called juvenile melanoma or prepubertal melanoma, these melanocytic nevi were assumed to be malignant; their discovery invariably led to draconian surgical procedures and dire prognoses. In 1947, a Cincinnati pathologist, Dr Sophie Spitz, noticed that none of the “juvenile melanoma” patients she had been involved with had ever shown any signs of cancer. This observation led her to conduct a study of several of these patients, in which it was confirmed that, in fact, these lesions were benign despite their appearance. She went on to determine the histologic differences of these lesions, publishing the results of that work in 1948. It was only after her death at age 46, from colon cancer, that these lesions became known as Spitz tumors, in her honor.

Since then, several variants of this lesion have been described, including the pigmented version described in this case. Another is called spitzoid melanoma—that is, melanoma that demonstrates some of the clinical and histologic features of Spitz tumors but behaves in a malignant fashion. Because of this, and because they mostly occur on children, they are usually removed with modest but definite margins. To this day, differentiation cannot be made on histologic bases alone, adding a significant degree of concern to the diagnosis (although only a tiny percentage ever exhibit malignant behavior).

The more common variety of Spitz tumors, also called epithelioid or spindle cell tumors, are much lighter in color (tan to red to brown) and tend to develop on the face, head, and neck, usually as solitary lesions presenting with an initial phase of rapid growth. The diagnosis of Spitz tumor in an older, sun-damaged patient is considered suspect, with the lesion treated as if it were melanoma.

Besides melanoma, the differential diagnosis for Spitz tumors includes compound nevus, juvenile xanthogranuloma, wart, and basal cell carcinoma.

This patient’s lesion clearly needs excision with clear margins. Given the patient’s age and the location of the lesion, the patient was referred to a plastic surgeon, who in turn will send the specimen to a dermatopathologist experienced in dealing with this tumor.

All this was carefully explained to the family, with reassurance of the probable benignancy of the lesion but also education about the need for continued vigilance. Following surgery, the patient will be followed by dermatology and watched for signs of malignant behavior at the surgical site and in relevant nodal drainage.

Immunosuppressed Woman with Lesion on Her Thumb

ANSWER

The correct answer is basal cell carcinoma (choice “d”), which only rarely affects the hands; it is far more common on more directly sun-exposed skin (eg, face, neck, and back).

Immunosuppressed individuals are at increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “a”), particularly those cancers associated with the human papillomavirus. These can present as odd plaques on the hands, so SCC belongs in the differential.

Mycobacterial infection (choice “b”) will demonstrate caseating (necrotic) granulomas and positive stains for acid-fast bacilli such as M marinum or M fortuitum; however, it can manifest with plaques.

Sarcoid (choice “c”) can be lesional and is thought to represent a reaction to an unknown antigen. Often reddish brown in color with plaquish morphology, sarcoid also demonstrates granulomatous changes microscopically; however, these are noncaseating epithelioid granulomas with no palisading.

DISCUSSION