User login

Complete Atrioventricular Nodal Block Due to Malignancy-Related Hypercalcemia

Complete atrioventricular (AV) block can occur due to structural or functional causes. Common structural etiologies include sclerodegenerative disease of the conduction system, ischemic heart disease in the acute or chronic setting, infiltrative myocardial disease, congenital heart disease, and cardiac surgery. Reversible etiologies of complete AV block include drug overdose and electrolyte abnormalities. In the following case study, the authors present a rare case of complete AV block caused by severe hypercalcemia related to malignancy that completely normalized after treatment of the hypercalcemia.

Case Report

A 63-year-old African-American man with metastatic carcinoma of the lungs (Figure 1) with unknown primary cancer was found to have a serum calcium level of 17.5 mg/dL (reference range:8.4-10.2 mg/dL) on routine preoperative laboratory testing prior to placement of a surgical port for chemotherapy. The patient also was noted to have a slow heart rate, and his electrocardiogram revealed a third-degree AV block with an escape rhythm at 29 bpm with a prolonged corrected QT (QTc) of 556 ms (Figure 2).

Although the patient reported nonspecific symptoms of fatigue, anorexia, dysphagia, and weight loss for 3 months, there were no new symptoms of dizziness, chest discomfort, or syncope. His past medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and the recently discovered bilateral lung metastasis. The patient reported no prior history of cardiac arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, or structural heart defects. His outpatient medications included aspirin, amlodipine, bupropion, hydralazine, and simvastatin.

At the physical examination the patient was cachectic but in no apparent distress. His heart rate escape rhythm was 29 bpm, with no murmurs and mildly reduced breath sounds. The patient’s blood pressure was 110/70. After correction for albumin, the serum calcium level was 17.8 mg/dL; ionized calcium level was 8.6 mg/dL; parathyroid hormone was 7.6 pg/mL (normal range, 12-88 pg/mL); parathyroid hormone-related protein was 6.4 pmol/L (normal range, < 2.0 pmol/L); potassium was 3.4 mmol/L (normal range, 3.5 – 5.1 mmol/L); and magnesium was 2.01 mg/dL. The patient’s thyroid stimulating hormone level was normal, and serial cardiac enzymes stayed within the reference range.

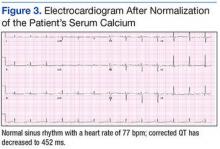

The patient was admitted to a cardiac care unit. A temporary transvenous pacemaker was placed, and the hypercalcemia was treated with aggressive fluid hydration, calcitonin, and zoledronic acid. Serum calcium gradually decreased to 14.6 mg/dL the following day and 9.6 mg/dL the subsequent day. The normalization of calcium resulted in resolution of complete heart block (Figure 3). The patient did not experience recurrence of AV nodal dysfunction and eventually died 3 months later due to his advanced metastatic disease.

Discussion

The reported cardiovascular effects of hypercalcemia include hypertension, arrhythmias, increased myocardial contractility at serum calcium level below 15 mg/dL, and myocardial depression above that level. Electrocardiographic manifestations of hypercalcemia include a shortened ST segment leading to a short corrected QT interval (QTc), slight increase in T wave duration, and rarely, Osborn waves or J waves.1-3 However, its influence on the AV node is less clear.

One small study assessed the prevalence of cardiac arrhythmias and conduction disturbances in 20 patients with hyperparathyroidism and moderate hypercalcemia and found no increase in the frequency of arrhythmias or high grade AV block.4

There are reports of conduction abnormality secondary to experimentally induced hypercalcemia in the literature. Hoff and colleagues described findings of AV block generated by the injection of IV calcium in dogs.5 In 2 human subjects, sinus bradycardia was precipitated after they received IV infusion of calcium gluconate.6 Shah and colleagues described 2 patients with sinus node dysfunction attributed to hypercalcemia secondary to hyperparathyroidism.7

Case reports of AV nodal dysfunction provoked by hypercalcemia have primarily occurred in the setting of primary hyperparathyroidism.8,9 Milk-alkali syndrome and vitamin D related hypercalcemia also have been reported to cause complete heart block.10,11 Reports of malignancy-related hypercalcemia causing conduction abnormalities are rare. The authors also found one case report of marked sinus bradycardia due to hypercalcemia related to breast cancer.12The case study presented in this report is rare because the patient developed complete AV block due to malignancy-related hypercalcemia that resolved completely with resolution of hypercalcemia. The prolongation of the QTc interval was another unique electrocardiographic change observed in this case. Calcium levels are inversely proportional to the QTc interval, and hypercalcemia is typically associated with a shortened QTc interval. However, this patient had a prolonged QTc without any other clear-cut cause. His hypokalemia was of a mild degree and not severe enough to produce such a long QTc interval. A possible explanation of QTc prolongation may be an increase in the T wave width associated with a serum calcium level above 16 mg/dL.

The pathophysiology of hypercalcemia-induced AV nodal conduction system disease is unknown. Calcium deposition in AV nodes of elderly patients has been associated with paroxysmal 2:1 AV block.8 It could be postulated that elevated serum calcium levels predispose to calcium deposition in cardiac conduction tissue, leading to progressive dysfunction. Although this theory may be applicable in a chronic setting, the mechanism in an acute setting likely relates to elevated serum levels of calcium that causes an alteration in electrochemical gradients. These elevated serum levels also increase intracellular calcium. This rise may result in increased calmodulin activation on the intracellular portion of the myocyte cell membrane and consequent enhanced sodium channel activation, which may then inhibit AV nodal conduction.13

Conclusion

Physicians should be aware that severe hypercalcemia can cause significant conduction system alterations, including complete AV block. A short QTc interval is typical, but a prolonged QTc interval also may be seen. While temporary support with a transvenous pacemaker may be needed, the conduction system abnormality is expected to resolve by treatment of the underlying hypercalcemia.

1. Nierenberg DW, Ransil BJ. Q-aTc interval as a clinical indicator of hypercalcemia. Am J Cardiol. 1979;44(2):243-248.

2. Bronsky D, Dubin A, Waldstein SS, Kushner DS. Calcium and the electrocardiogram II. The electrocardiographic manifestations of hyperparathyroidism and of marked hypercalcemia from various other etiologies. Am J Cardiol. 1961;7(6):833-839.

3. Otero J, Lenihan DJ. The "normothermic" Osborn wave induced by severe hypercalcemia. Tex Heart Inst J. 2000;27(3):316-317.

4. Rosenqvist M, Nordenström J, Andersson M, Edhag OK. Cardiac conduction inpatients with hypercalcaemia due to primary hyperparathyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1992;37(1):29-33.

5. Hoff H, Smith P, Winkler A. Electrocardiographic changes and concentration of calcium in serum following injection of calcium chloride. Am J Physiol. 1939;125:162-171.

6. Howard JE, Hopkins TR, Connor TB. The use of intravenous calcium as a measure of activity of the parathyroid glands. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1952;65:351-358.

7. Shah AP, Lopez A, Wachsner RY, Meymandi SK, El-Bialy AK, Ichiuji AM. Sinus node dysfunction secondary to hyperparathyroidism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2004;9(2):145-147.

8. Vosnakidis A, Polymeropoulos K, Zaragoulidis P, Zarifis I. Atrioventricular nodal dysfunction secondary to hyperparathyroidism. J Thoracic Dis. 2013;5(3):E90-E92.

9. Crum WB, Till HJ. Hyperparathyroidism with Wenckebach's phenomenon. Am J Cardiol. 1960;6:838-840.

10. Ginsberg H, Schwarz KV. Letter: hypercalcemia and complete heart block. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79(6):903.

11. Garg G, Khadgwat R, Khandelwal D, Gupta N. Vitamin D toxicity presenting as hypercalcemia and complete heart block: an interesting case report. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16 (suppl 2):S423-S425.

12. Badertscher E, Warnica JW, Ernst DS. Acute hypercalcemia and severe bradycardia in a patient with breast cancer. CMAJ. 1993;148(9):1506-1508.

13. Potet F, Chagot B, Anghelescu M, et al. Functional interactions between distinct sodium channel cytoplasmic domains through the action of calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(13):8846-8854.

Complete atrioventricular (AV) block can occur due to structural or functional causes. Common structural etiologies include sclerodegenerative disease of the conduction system, ischemic heart disease in the acute or chronic setting, infiltrative myocardial disease, congenital heart disease, and cardiac surgery. Reversible etiologies of complete AV block include drug overdose and electrolyte abnormalities. In the following case study, the authors present a rare case of complete AV block caused by severe hypercalcemia related to malignancy that completely normalized after treatment of the hypercalcemia.

Case Report

A 63-year-old African-American man with metastatic carcinoma of the lungs (Figure 1) with unknown primary cancer was found to have a serum calcium level of 17.5 mg/dL (reference range:8.4-10.2 mg/dL) on routine preoperative laboratory testing prior to placement of a surgical port for chemotherapy. The patient also was noted to have a slow heart rate, and his electrocardiogram revealed a third-degree AV block with an escape rhythm at 29 bpm with a prolonged corrected QT (QTc) of 556 ms (Figure 2).

Although the patient reported nonspecific symptoms of fatigue, anorexia, dysphagia, and weight loss for 3 months, there were no new symptoms of dizziness, chest discomfort, or syncope. His past medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and the recently discovered bilateral lung metastasis. The patient reported no prior history of cardiac arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, or structural heart defects. His outpatient medications included aspirin, amlodipine, bupropion, hydralazine, and simvastatin.

At the physical examination the patient was cachectic but in no apparent distress. His heart rate escape rhythm was 29 bpm, with no murmurs and mildly reduced breath sounds. The patient’s blood pressure was 110/70. After correction for albumin, the serum calcium level was 17.8 mg/dL; ionized calcium level was 8.6 mg/dL; parathyroid hormone was 7.6 pg/mL (normal range, 12-88 pg/mL); parathyroid hormone-related protein was 6.4 pmol/L (normal range, < 2.0 pmol/L); potassium was 3.4 mmol/L (normal range, 3.5 – 5.1 mmol/L); and magnesium was 2.01 mg/dL. The patient’s thyroid stimulating hormone level was normal, and serial cardiac enzymes stayed within the reference range.

The patient was admitted to a cardiac care unit. A temporary transvenous pacemaker was placed, and the hypercalcemia was treated with aggressive fluid hydration, calcitonin, and zoledronic acid. Serum calcium gradually decreased to 14.6 mg/dL the following day and 9.6 mg/dL the subsequent day. The normalization of calcium resulted in resolution of complete heart block (Figure 3). The patient did not experience recurrence of AV nodal dysfunction and eventually died 3 months later due to his advanced metastatic disease.

Discussion

The reported cardiovascular effects of hypercalcemia include hypertension, arrhythmias, increased myocardial contractility at serum calcium level below 15 mg/dL, and myocardial depression above that level. Electrocardiographic manifestations of hypercalcemia include a shortened ST segment leading to a short corrected QT interval (QTc), slight increase in T wave duration, and rarely, Osborn waves or J waves.1-3 However, its influence on the AV node is less clear.

One small study assessed the prevalence of cardiac arrhythmias and conduction disturbances in 20 patients with hyperparathyroidism and moderate hypercalcemia and found no increase in the frequency of arrhythmias or high grade AV block.4

There are reports of conduction abnormality secondary to experimentally induced hypercalcemia in the literature. Hoff and colleagues described findings of AV block generated by the injection of IV calcium in dogs.5 In 2 human subjects, sinus bradycardia was precipitated after they received IV infusion of calcium gluconate.6 Shah and colleagues described 2 patients with sinus node dysfunction attributed to hypercalcemia secondary to hyperparathyroidism.7

Case reports of AV nodal dysfunction provoked by hypercalcemia have primarily occurred in the setting of primary hyperparathyroidism.8,9 Milk-alkali syndrome and vitamin D related hypercalcemia also have been reported to cause complete heart block.10,11 Reports of malignancy-related hypercalcemia causing conduction abnormalities are rare. The authors also found one case report of marked sinus bradycardia due to hypercalcemia related to breast cancer.12The case study presented in this report is rare because the patient developed complete AV block due to malignancy-related hypercalcemia that resolved completely with resolution of hypercalcemia. The prolongation of the QTc interval was another unique electrocardiographic change observed in this case. Calcium levels are inversely proportional to the QTc interval, and hypercalcemia is typically associated with a shortened QTc interval. However, this patient had a prolonged QTc without any other clear-cut cause. His hypokalemia was of a mild degree and not severe enough to produce such a long QTc interval. A possible explanation of QTc prolongation may be an increase in the T wave width associated with a serum calcium level above 16 mg/dL.

The pathophysiology of hypercalcemia-induced AV nodal conduction system disease is unknown. Calcium deposition in AV nodes of elderly patients has been associated with paroxysmal 2:1 AV block.8 It could be postulated that elevated serum calcium levels predispose to calcium deposition in cardiac conduction tissue, leading to progressive dysfunction. Although this theory may be applicable in a chronic setting, the mechanism in an acute setting likely relates to elevated serum levels of calcium that causes an alteration in electrochemical gradients. These elevated serum levels also increase intracellular calcium. This rise may result in increased calmodulin activation on the intracellular portion of the myocyte cell membrane and consequent enhanced sodium channel activation, which may then inhibit AV nodal conduction.13

Conclusion

Physicians should be aware that severe hypercalcemia can cause significant conduction system alterations, including complete AV block. A short QTc interval is typical, but a prolonged QTc interval also may be seen. While temporary support with a transvenous pacemaker may be needed, the conduction system abnormality is expected to resolve by treatment of the underlying hypercalcemia.

Complete atrioventricular (AV) block can occur due to structural or functional causes. Common structural etiologies include sclerodegenerative disease of the conduction system, ischemic heart disease in the acute or chronic setting, infiltrative myocardial disease, congenital heart disease, and cardiac surgery. Reversible etiologies of complete AV block include drug overdose and electrolyte abnormalities. In the following case study, the authors present a rare case of complete AV block caused by severe hypercalcemia related to malignancy that completely normalized after treatment of the hypercalcemia.

Case Report

A 63-year-old African-American man with metastatic carcinoma of the lungs (Figure 1) with unknown primary cancer was found to have a serum calcium level of 17.5 mg/dL (reference range:8.4-10.2 mg/dL) on routine preoperative laboratory testing prior to placement of a surgical port for chemotherapy. The patient also was noted to have a slow heart rate, and his electrocardiogram revealed a third-degree AV block with an escape rhythm at 29 bpm with a prolonged corrected QT (QTc) of 556 ms (Figure 2).

Although the patient reported nonspecific symptoms of fatigue, anorexia, dysphagia, and weight loss for 3 months, there were no new symptoms of dizziness, chest discomfort, or syncope. His past medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and the recently discovered bilateral lung metastasis. The patient reported no prior history of cardiac arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, or structural heart defects. His outpatient medications included aspirin, amlodipine, bupropion, hydralazine, and simvastatin.

At the physical examination the patient was cachectic but in no apparent distress. His heart rate escape rhythm was 29 bpm, with no murmurs and mildly reduced breath sounds. The patient’s blood pressure was 110/70. After correction for albumin, the serum calcium level was 17.8 mg/dL; ionized calcium level was 8.6 mg/dL; parathyroid hormone was 7.6 pg/mL (normal range, 12-88 pg/mL); parathyroid hormone-related protein was 6.4 pmol/L (normal range, < 2.0 pmol/L); potassium was 3.4 mmol/L (normal range, 3.5 – 5.1 mmol/L); and magnesium was 2.01 mg/dL. The patient’s thyroid stimulating hormone level was normal, and serial cardiac enzymes stayed within the reference range.

The patient was admitted to a cardiac care unit. A temporary transvenous pacemaker was placed, and the hypercalcemia was treated with aggressive fluid hydration, calcitonin, and zoledronic acid. Serum calcium gradually decreased to 14.6 mg/dL the following day and 9.6 mg/dL the subsequent day. The normalization of calcium resulted in resolution of complete heart block (Figure 3). The patient did not experience recurrence of AV nodal dysfunction and eventually died 3 months later due to his advanced metastatic disease.

Discussion

The reported cardiovascular effects of hypercalcemia include hypertension, arrhythmias, increased myocardial contractility at serum calcium level below 15 mg/dL, and myocardial depression above that level. Electrocardiographic manifestations of hypercalcemia include a shortened ST segment leading to a short corrected QT interval (QTc), slight increase in T wave duration, and rarely, Osborn waves or J waves.1-3 However, its influence on the AV node is less clear.

One small study assessed the prevalence of cardiac arrhythmias and conduction disturbances in 20 patients with hyperparathyroidism and moderate hypercalcemia and found no increase in the frequency of arrhythmias or high grade AV block.4

There are reports of conduction abnormality secondary to experimentally induced hypercalcemia in the literature. Hoff and colleagues described findings of AV block generated by the injection of IV calcium in dogs.5 In 2 human subjects, sinus bradycardia was precipitated after they received IV infusion of calcium gluconate.6 Shah and colleagues described 2 patients with sinus node dysfunction attributed to hypercalcemia secondary to hyperparathyroidism.7

Case reports of AV nodal dysfunction provoked by hypercalcemia have primarily occurred in the setting of primary hyperparathyroidism.8,9 Milk-alkali syndrome and vitamin D related hypercalcemia also have been reported to cause complete heart block.10,11 Reports of malignancy-related hypercalcemia causing conduction abnormalities are rare. The authors also found one case report of marked sinus bradycardia due to hypercalcemia related to breast cancer.12The case study presented in this report is rare because the patient developed complete AV block due to malignancy-related hypercalcemia that resolved completely with resolution of hypercalcemia. The prolongation of the QTc interval was another unique electrocardiographic change observed in this case. Calcium levels are inversely proportional to the QTc interval, and hypercalcemia is typically associated with a shortened QTc interval. However, this patient had a prolonged QTc without any other clear-cut cause. His hypokalemia was of a mild degree and not severe enough to produce such a long QTc interval. A possible explanation of QTc prolongation may be an increase in the T wave width associated with a serum calcium level above 16 mg/dL.

The pathophysiology of hypercalcemia-induced AV nodal conduction system disease is unknown. Calcium deposition in AV nodes of elderly patients has been associated with paroxysmal 2:1 AV block.8 It could be postulated that elevated serum calcium levels predispose to calcium deposition in cardiac conduction tissue, leading to progressive dysfunction. Although this theory may be applicable in a chronic setting, the mechanism in an acute setting likely relates to elevated serum levels of calcium that causes an alteration in electrochemical gradients. These elevated serum levels also increase intracellular calcium. This rise may result in increased calmodulin activation on the intracellular portion of the myocyte cell membrane and consequent enhanced sodium channel activation, which may then inhibit AV nodal conduction.13

Conclusion

Physicians should be aware that severe hypercalcemia can cause significant conduction system alterations, including complete AV block. A short QTc interval is typical, but a prolonged QTc interval also may be seen. While temporary support with a transvenous pacemaker may be needed, the conduction system abnormality is expected to resolve by treatment of the underlying hypercalcemia.

1. Nierenberg DW, Ransil BJ. Q-aTc interval as a clinical indicator of hypercalcemia. Am J Cardiol. 1979;44(2):243-248.

2. Bronsky D, Dubin A, Waldstein SS, Kushner DS. Calcium and the electrocardiogram II. The electrocardiographic manifestations of hyperparathyroidism and of marked hypercalcemia from various other etiologies. Am J Cardiol. 1961;7(6):833-839.

3. Otero J, Lenihan DJ. The "normothermic" Osborn wave induced by severe hypercalcemia. Tex Heart Inst J. 2000;27(3):316-317.

4. Rosenqvist M, Nordenström J, Andersson M, Edhag OK. Cardiac conduction inpatients with hypercalcaemia due to primary hyperparathyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1992;37(1):29-33.

5. Hoff H, Smith P, Winkler A. Electrocardiographic changes and concentration of calcium in serum following injection of calcium chloride. Am J Physiol. 1939;125:162-171.

6. Howard JE, Hopkins TR, Connor TB. The use of intravenous calcium as a measure of activity of the parathyroid glands. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1952;65:351-358.

7. Shah AP, Lopez A, Wachsner RY, Meymandi SK, El-Bialy AK, Ichiuji AM. Sinus node dysfunction secondary to hyperparathyroidism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2004;9(2):145-147.

8. Vosnakidis A, Polymeropoulos K, Zaragoulidis P, Zarifis I. Atrioventricular nodal dysfunction secondary to hyperparathyroidism. J Thoracic Dis. 2013;5(3):E90-E92.

9. Crum WB, Till HJ. Hyperparathyroidism with Wenckebach's phenomenon. Am J Cardiol. 1960;6:838-840.

10. Ginsberg H, Schwarz KV. Letter: hypercalcemia and complete heart block. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79(6):903.

11. Garg G, Khadgwat R, Khandelwal D, Gupta N. Vitamin D toxicity presenting as hypercalcemia and complete heart block: an interesting case report. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16 (suppl 2):S423-S425.

12. Badertscher E, Warnica JW, Ernst DS. Acute hypercalcemia and severe bradycardia in a patient with breast cancer. CMAJ. 1993;148(9):1506-1508.

13. Potet F, Chagot B, Anghelescu M, et al. Functional interactions between distinct sodium channel cytoplasmic domains through the action of calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(13):8846-8854.

1. Nierenberg DW, Ransil BJ. Q-aTc interval as a clinical indicator of hypercalcemia. Am J Cardiol. 1979;44(2):243-248.

2. Bronsky D, Dubin A, Waldstein SS, Kushner DS. Calcium and the electrocardiogram II. The electrocardiographic manifestations of hyperparathyroidism and of marked hypercalcemia from various other etiologies. Am J Cardiol. 1961;7(6):833-839.

3. Otero J, Lenihan DJ. The "normothermic" Osborn wave induced by severe hypercalcemia. Tex Heart Inst J. 2000;27(3):316-317.

4. Rosenqvist M, Nordenström J, Andersson M, Edhag OK. Cardiac conduction inpatients with hypercalcaemia due to primary hyperparathyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1992;37(1):29-33.

5. Hoff H, Smith P, Winkler A. Electrocardiographic changes and concentration of calcium in serum following injection of calcium chloride. Am J Physiol. 1939;125:162-171.

6. Howard JE, Hopkins TR, Connor TB. The use of intravenous calcium as a measure of activity of the parathyroid glands. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1952;65:351-358.

7. Shah AP, Lopez A, Wachsner RY, Meymandi SK, El-Bialy AK, Ichiuji AM. Sinus node dysfunction secondary to hyperparathyroidism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2004;9(2):145-147.

8. Vosnakidis A, Polymeropoulos K, Zaragoulidis P, Zarifis I. Atrioventricular nodal dysfunction secondary to hyperparathyroidism. J Thoracic Dis. 2013;5(3):E90-E92.

9. Crum WB, Till HJ. Hyperparathyroidism with Wenckebach's phenomenon. Am J Cardiol. 1960;6:838-840.

10. Ginsberg H, Schwarz KV. Letter: hypercalcemia and complete heart block. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79(6):903.

11. Garg G, Khadgwat R, Khandelwal D, Gupta N. Vitamin D toxicity presenting as hypercalcemia and complete heart block: an interesting case report. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16 (suppl 2):S423-S425.

12. Badertscher E, Warnica JW, Ernst DS. Acute hypercalcemia and severe bradycardia in a patient with breast cancer. CMAJ. 1993;148(9):1506-1508.

13. Potet F, Chagot B, Anghelescu M, et al. Functional interactions between distinct sodium channel cytoplasmic domains through the action of calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(13):8846-8854.