User login

Does qHPV vaccine prevent anal intraepithelial neoplasia and condylomata in men?

Yes. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus (qHPV) vaccine reduces rates of anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) by 50% to 54%, and persistent anal infection by 59%, associated with the 4 types of HPV in the vaccine (6, 11, 16, and 18) in young men who have sex with men (MSM); it also reduces external genital lesions by 66%, and persistent HPV infection associated with the same 4 HPV types by 48 to 59% in all young men, heterosexual men,and MSM (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized, placebo-controlled trials [RCTs]).

In addition, the vaccine is associated with a 50% to 55% decrease in recurrent high-grade AIN and anogenital condylomatain older MSM (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

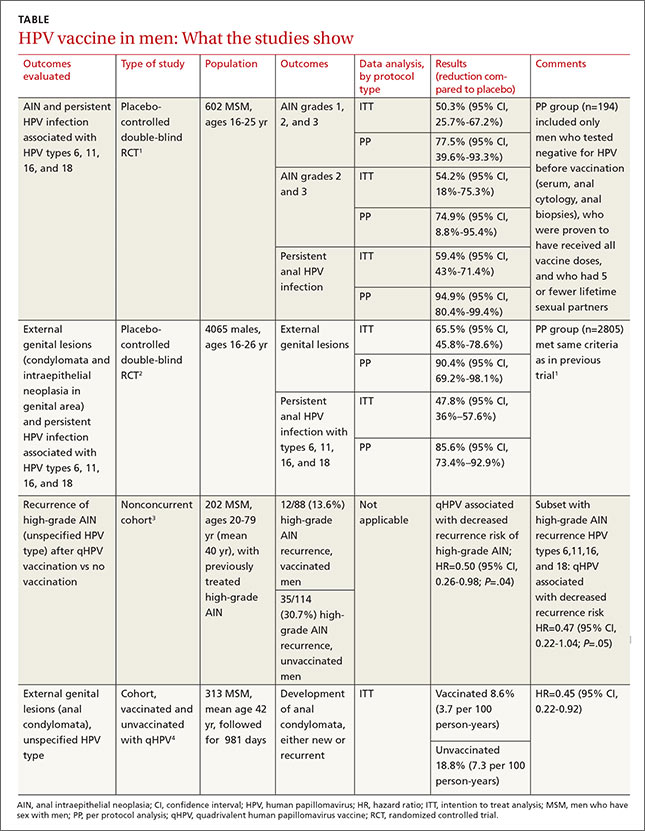

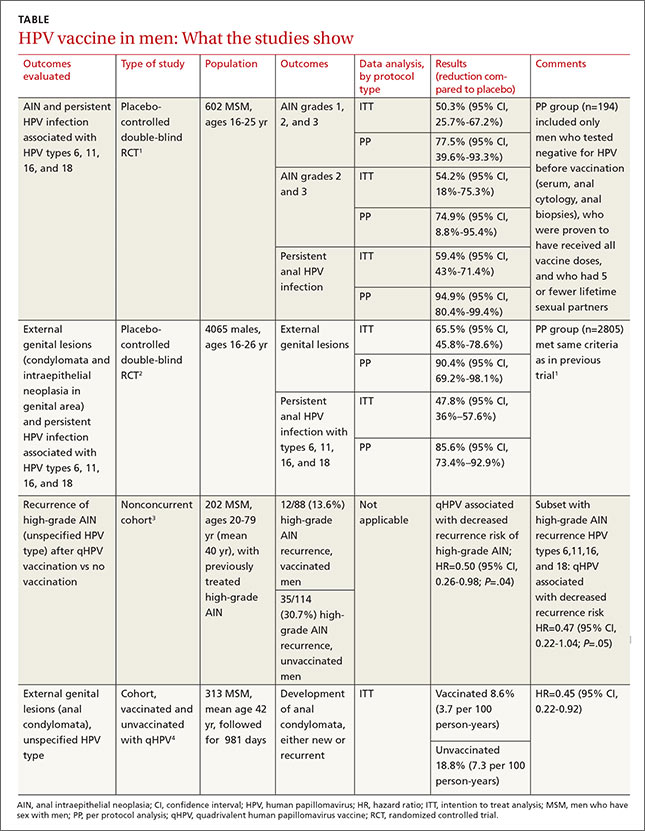

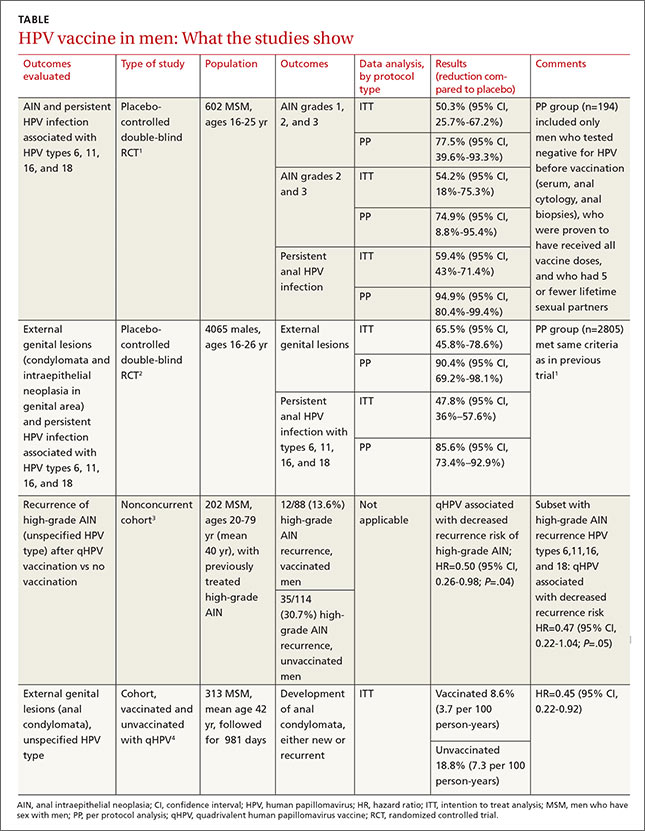

Two RCTs that evaluated qHPV in young men for preventing outcomes associated with the 4 HPV subtypes in the vaccine (6, 11, 16, and 18) found that it reduced them by 50% to 66% using an intention-to-treat protocol (TABLE1-4).

Vaccination reduces AIN and persistent infection in MSM

The first RCT evaluated a subset of 602 MSM from the second, larger RCT for preventing AIN and persistent HPV infection.1 The intention-to-treat population included men with 5 or fewer lifetime sexual partners who had engaged in insertive or receptive anal intercourse or oral sex within the last year, were not necessarily HPV-negative at enrollment, and received at least one dose of vaccine (or placebo).

The vaccine reduced AIN associated with the 4 HPV types (6.3 vs 12.6 events per 100 person-years; relative risk reduction [RRR]=50.3%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 25.7-67.2; number needed to treat [NNT]=16 to prevent one AIN case per year) and with HPV of any type (13 vs 17.5 events per 100 person-years; RRR=25.7%; 95% CI, -1.1 to 45.6). It also reduced the rate of persistent HPV infection with the 4 HPV vaccine subtypes (8.8 vs 21.6 events per 100 person-years; RRR=59.4%; 95% CI, 43%-71%; NNT=8 to prevent one persistent HPV infection per year).

Investigators in the study also evaluated vaccine efficacy in a smaller subset (194 men) using per-protocol analysis and found higher prevention rates (78% for AIN due to HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18). Investigators followed these subjects every 6 months for 36 months with polymerase chain reaction testing for HPV DNA, high-resolution anoscopy with anal cytology, and anal biopsy and histology if there were atypia.

The vaccine decreases persistent HPV infection and external genital lesions

The second RCT, including both MSM and heterosexual men, found that qHPV vaccine reduced rates of persistent HPV infection by 48%, and external genital lesions (condylomata or intraepithelial neoplasia involving the penis, perineum, or perianal area) by 66% associated with HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 using the intention-to-treat protocol.2

Investigators used the same protocols used in the first RCT, and the per-protocol population again had higher prevention rates (84% for any HPV type, 90% against the 4 vaccine types). The only adverse effect of the vaccine was injection site pain (57% vs 51% with placebo; P<.001).

The vaccine also helps older MSM

A nonconcurrent cohort study that evaluated qHPV vaccination among older MSM with previously treated high-grade AIN found a 50% decrease in recurrence rates in the 2 years after vaccination.3 Investigators recruited HIV-negative men, some of whom chose vaccination (not randomized), and followed them for 2 years. Study limitations included using medical records for data collection and the predominance of white, nonsmoking men with private insurance.

A post-hoc analysis of older men without previous anal condylomata (210 men) or with treated condylomata and no recurrence in the year before vaccination (103 men) found that qHPV vaccination was associated with 55% lower rates of anal condylomata.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends routine use of qHPV vaccine in males ages 11 through 21 years, and optional use in unvaccinated men as old as 26 years.5

1. Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1576-1585.

2. Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV infection and disease in males. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:401-411.

3. Swedish KA, Factor SH, Goldstone SE. Prevention of recurrent high-grade anal neoplasia with quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination of men who have sex with men: a nonconcurrent cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:891-898.

4. Swedish KA, Goldstone SE. Prevention of anal condyloma with quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination of older men who have sex with men. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93393.

5. Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-05):1-30.

Yes. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus (qHPV) vaccine reduces rates of anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) by 50% to 54%, and persistent anal infection by 59%, associated with the 4 types of HPV in the vaccine (6, 11, 16, and 18) in young men who have sex with men (MSM); it also reduces external genital lesions by 66%, and persistent HPV infection associated with the same 4 HPV types by 48 to 59% in all young men, heterosexual men,and MSM (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized, placebo-controlled trials [RCTs]).

In addition, the vaccine is associated with a 50% to 55% decrease in recurrent high-grade AIN and anogenital condylomatain older MSM (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Two RCTs that evaluated qHPV in young men for preventing outcomes associated with the 4 HPV subtypes in the vaccine (6, 11, 16, and 18) found that it reduced them by 50% to 66% using an intention-to-treat protocol (TABLE1-4).

Vaccination reduces AIN and persistent infection in MSM

The first RCT evaluated a subset of 602 MSM from the second, larger RCT for preventing AIN and persistent HPV infection.1 The intention-to-treat population included men with 5 or fewer lifetime sexual partners who had engaged in insertive or receptive anal intercourse or oral sex within the last year, were not necessarily HPV-negative at enrollment, and received at least one dose of vaccine (or placebo).

The vaccine reduced AIN associated with the 4 HPV types (6.3 vs 12.6 events per 100 person-years; relative risk reduction [RRR]=50.3%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 25.7-67.2; number needed to treat [NNT]=16 to prevent one AIN case per year) and with HPV of any type (13 vs 17.5 events per 100 person-years; RRR=25.7%; 95% CI, -1.1 to 45.6). It also reduced the rate of persistent HPV infection with the 4 HPV vaccine subtypes (8.8 vs 21.6 events per 100 person-years; RRR=59.4%; 95% CI, 43%-71%; NNT=8 to prevent one persistent HPV infection per year).

Investigators in the study also evaluated vaccine efficacy in a smaller subset (194 men) using per-protocol analysis and found higher prevention rates (78% for AIN due to HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18). Investigators followed these subjects every 6 months for 36 months with polymerase chain reaction testing for HPV DNA, high-resolution anoscopy with anal cytology, and anal biopsy and histology if there were atypia.

The vaccine decreases persistent HPV infection and external genital lesions

The second RCT, including both MSM and heterosexual men, found that qHPV vaccine reduced rates of persistent HPV infection by 48%, and external genital lesions (condylomata or intraepithelial neoplasia involving the penis, perineum, or perianal area) by 66% associated with HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 using the intention-to-treat protocol.2

Investigators used the same protocols used in the first RCT, and the per-protocol population again had higher prevention rates (84% for any HPV type, 90% against the 4 vaccine types). The only adverse effect of the vaccine was injection site pain (57% vs 51% with placebo; P<.001).

The vaccine also helps older MSM

A nonconcurrent cohort study that evaluated qHPV vaccination among older MSM with previously treated high-grade AIN found a 50% decrease in recurrence rates in the 2 years after vaccination.3 Investigators recruited HIV-negative men, some of whom chose vaccination (not randomized), and followed them for 2 years. Study limitations included using medical records for data collection and the predominance of white, nonsmoking men with private insurance.

A post-hoc analysis of older men without previous anal condylomata (210 men) or with treated condylomata and no recurrence in the year before vaccination (103 men) found that qHPV vaccination was associated with 55% lower rates of anal condylomata.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends routine use of qHPV vaccine in males ages 11 through 21 years, and optional use in unvaccinated men as old as 26 years.5

Yes. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus (qHPV) vaccine reduces rates of anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) by 50% to 54%, and persistent anal infection by 59%, associated with the 4 types of HPV in the vaccine (6, 11, 16, and 18) in young men who have sex with men (MSM); it also reduces external genital lesions by 66%, and persistent HPV infection associated with the same 4 HPV types by 48 to 59% in all young men, heterosexual men,and MSM (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized, placebo-controlled trials [RCTs]).

In addition, the vaccine is associated with a 50% to 55% decrease in recurrent high-grade AIN and anogenital condylomatain older MSM (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Two RCTs that evaluated qHPV in young men for preventing outcomes associated with the 4 HPV subtypes in the vaccine (6, 11, 16, and 18) found that it reduced them by 50% to 66% using an intention-to-treat protocol (TABLE1-4).

Vaccination reduces AIN and persistent infection in MSM

The first RCT evaluated a subset of 602 MSM from the second, larger RCT for preventing AIN and persistent HPV infection.1 The intention-to-treat population included men with 5 or fewer lifetime sexual partners who had engaged in insertive or receptive anal intercourse or oral sex within the last year, were not necessarily HPV-negative at enrollment, and received at least one dose of vaccine (or placebo).

The vaccine reduced AIN associated with the 4 HPV types (6.3 vs 12.6 events per 100 person-years; relative risk reduction [RRR]=50.3%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 25.7-67.2; number needed to treat [NNT]=16 to prevent one AIN case per year) and with HPV of any type (13 vs 17.5 events per 100 person-years; RRR=25.7%; 95% CI, -1.1 to 45.6). It also reduced the rate of persistent HPV infection with the 4 HPV vaccine subtypes (8.8 vs 21.6 events per 100 person-years; RRR=59.4%; 95% CI, 43%-71%; NNT=8 to prevent one persistent HPV infection per year).

Investigators in the study also evaluated vaccine efficacy in a smaller subset (194 men) using per-protocol analysis and found higher prevention rates (78% for AIN due to HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18). Investigators followed these subjects every 6 months for 36 months with polymerase chain reaction testing for HPV DNA, high-resolution anoscopy with anal cytology, and anal biopsy and histology if there were atypia.

The vaccine decreases persistent HPV infection and external genital lesions

The second RCT, including both MSM and heterosexual men, found that qHPV vaccine reduced rates of persistent HPV infection by 48%, and external genital lesions (condylomata or intraepithelial neoplasia involving the penis, perineum, or perianal area) by 66% associated with HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 using the intention-to-treat protocol.2

Investigators used the same protocols used in the first RCT, and the per-protocol population again had higher prevention rates (84% for any HPV type, 90% against the 4 vaccine types). The only adverse effect of the vaccine was injection site pain (57% vs 51% with placebo; P<.001).

The vaccine also helps older MSM

A nonconcurrent cohort study that evaluated qHPV vaccination among older MSM with previously treated high-grade AIN found a 50% decrease in recurrence rates in the 2 years after vaccination.3 Investigators recruited HIV-negative men, some of whom chose vaccination (not randomized), and followed them for 2 years. Study limitations included using medical records for data collection and the predominance of white, nonsmoking men with private insurance.

A post-hoc analysis of older men without previous anal condylomata (210 men) or with treated condylomata and no recurrence in the year before vaccination (103 men) found that qHPV vaccination was associated with 55% lower rates of anal condylomata.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends routine use of qHPV vaccine in males ages 11 through 21 years, and optional use in unvaccinated men as old as 26 years.5

1. Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1576-1585.

2. Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV infection and disease in males. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:401-411.

3. Swedish KA, Factor SH, Goldstone SE. Prevention of recurrent high-grade anal neoplasia with quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination of men who have sex with men: a nonconcurrent cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:891-898.

4. Swedish KA, Goldstone SE. Prevention of anal condyloma with quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination of older men who have sex with men. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93393.

5. Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-05):1-30.

1. Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1576-1585.

2. Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV infection and disease in males. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:401-411.

3. Swedish KA, Factor SH, Goldstone SE. Prevention of recurrent high-grade anal neoplasia with quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination of men who have sex with men: a nonconcurrent cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:891-898.

4. Swedish KA, Goldstone SE. Prevention of anal condyloma with quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination of older men who have sex with men. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93393.

5. Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-05):1-30.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network