User login

Pills to powder: An updated clinician’s reference for crushable psychotropics

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

- discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

- postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

- dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

- odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

- a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

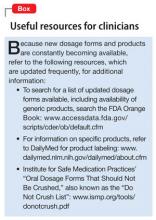

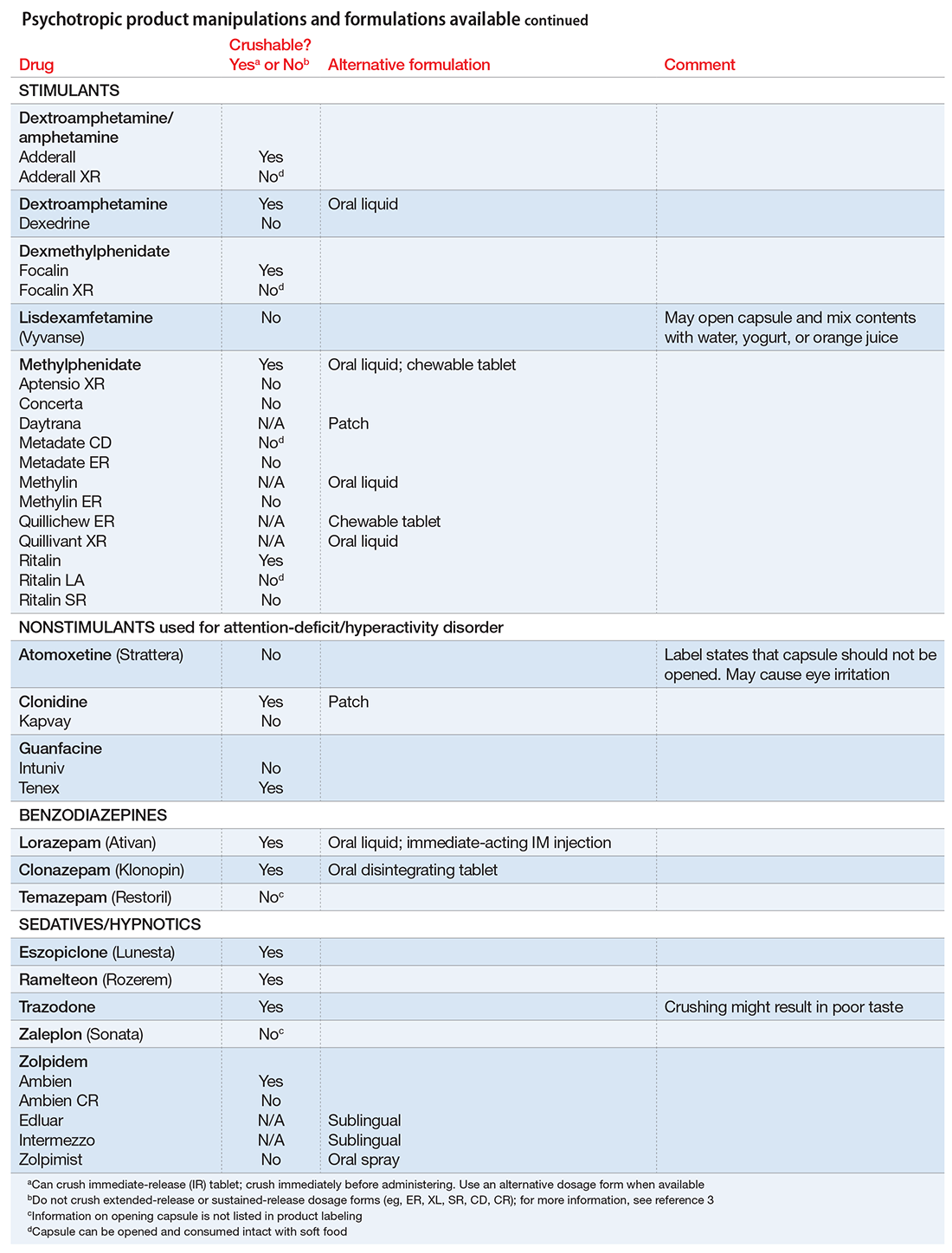

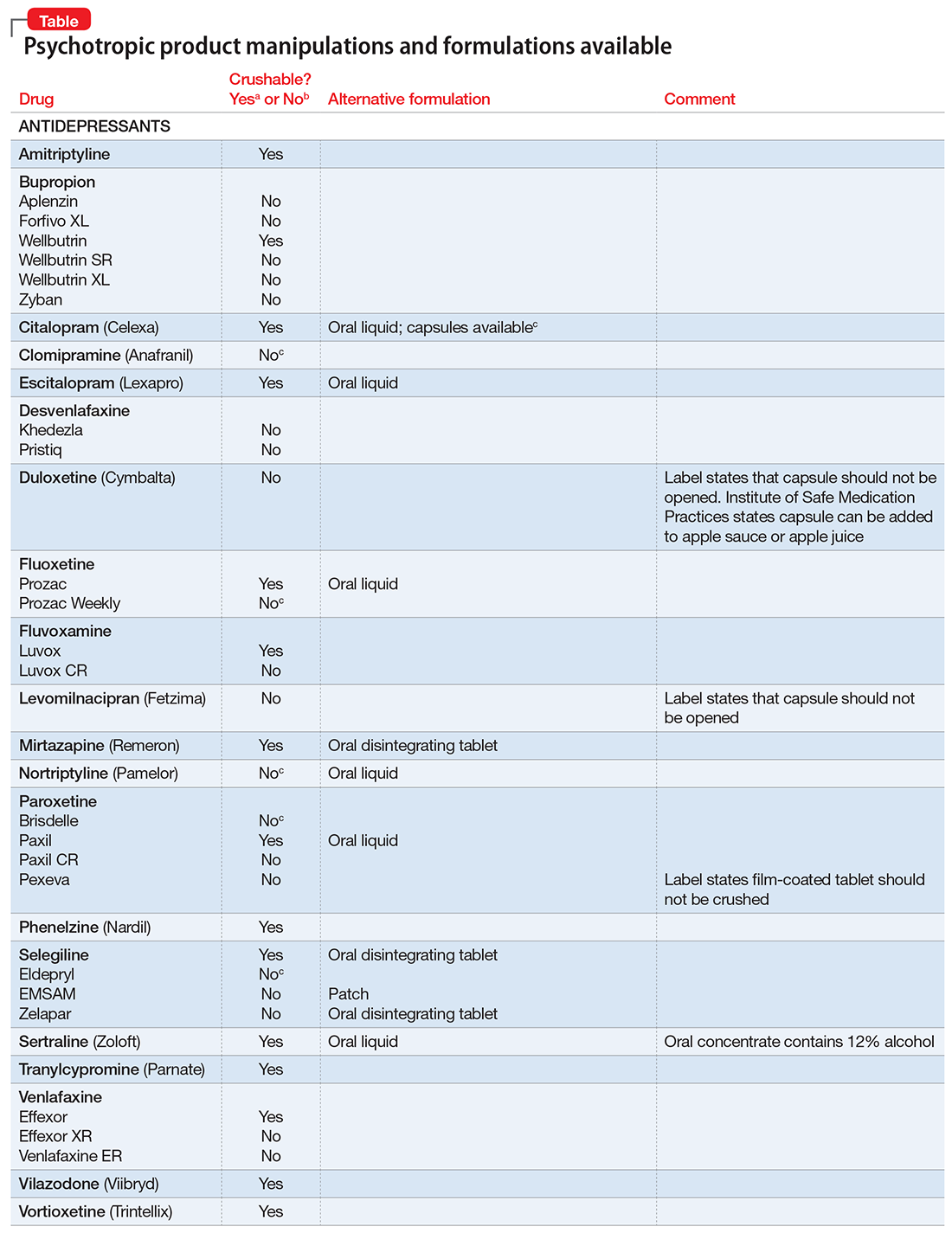

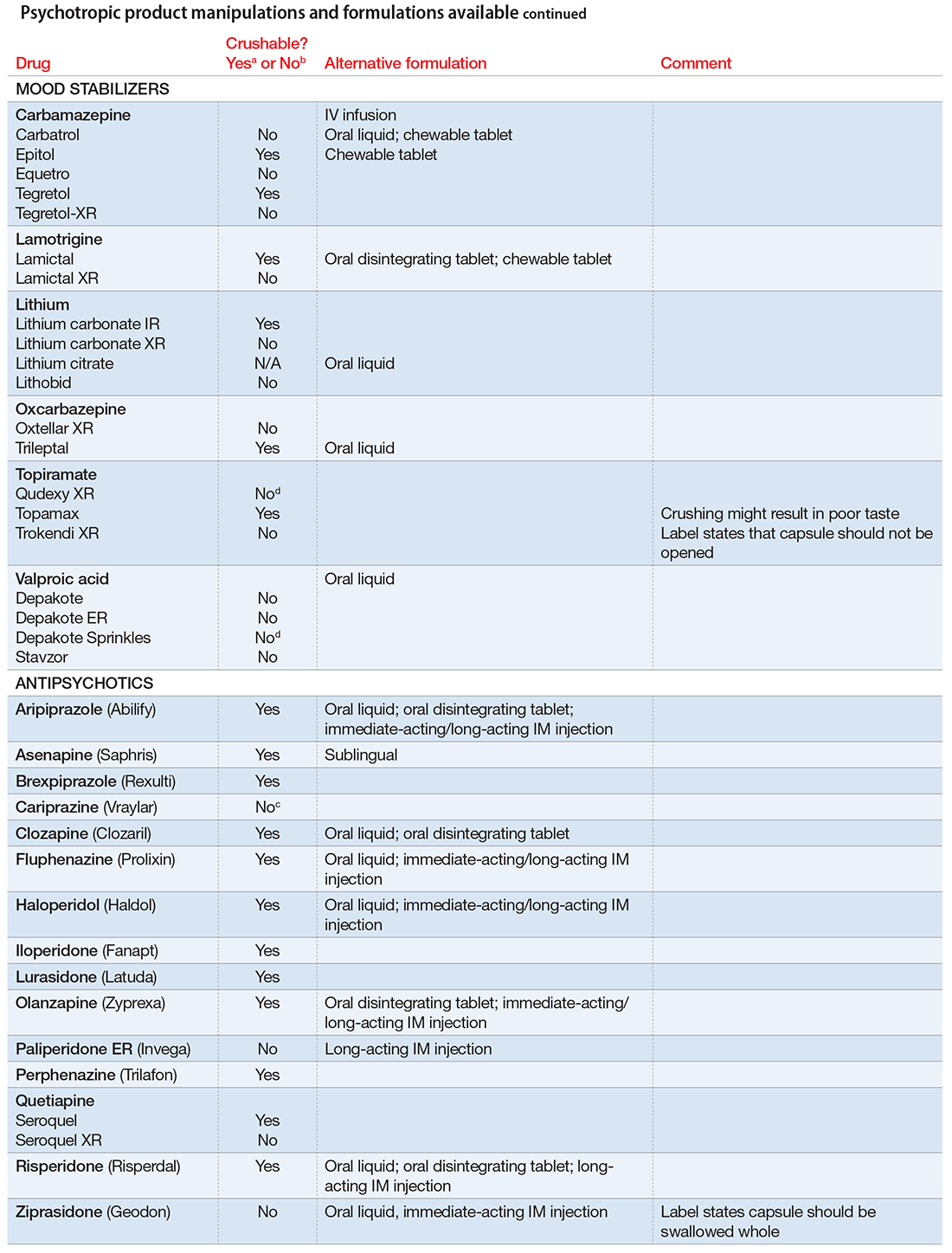

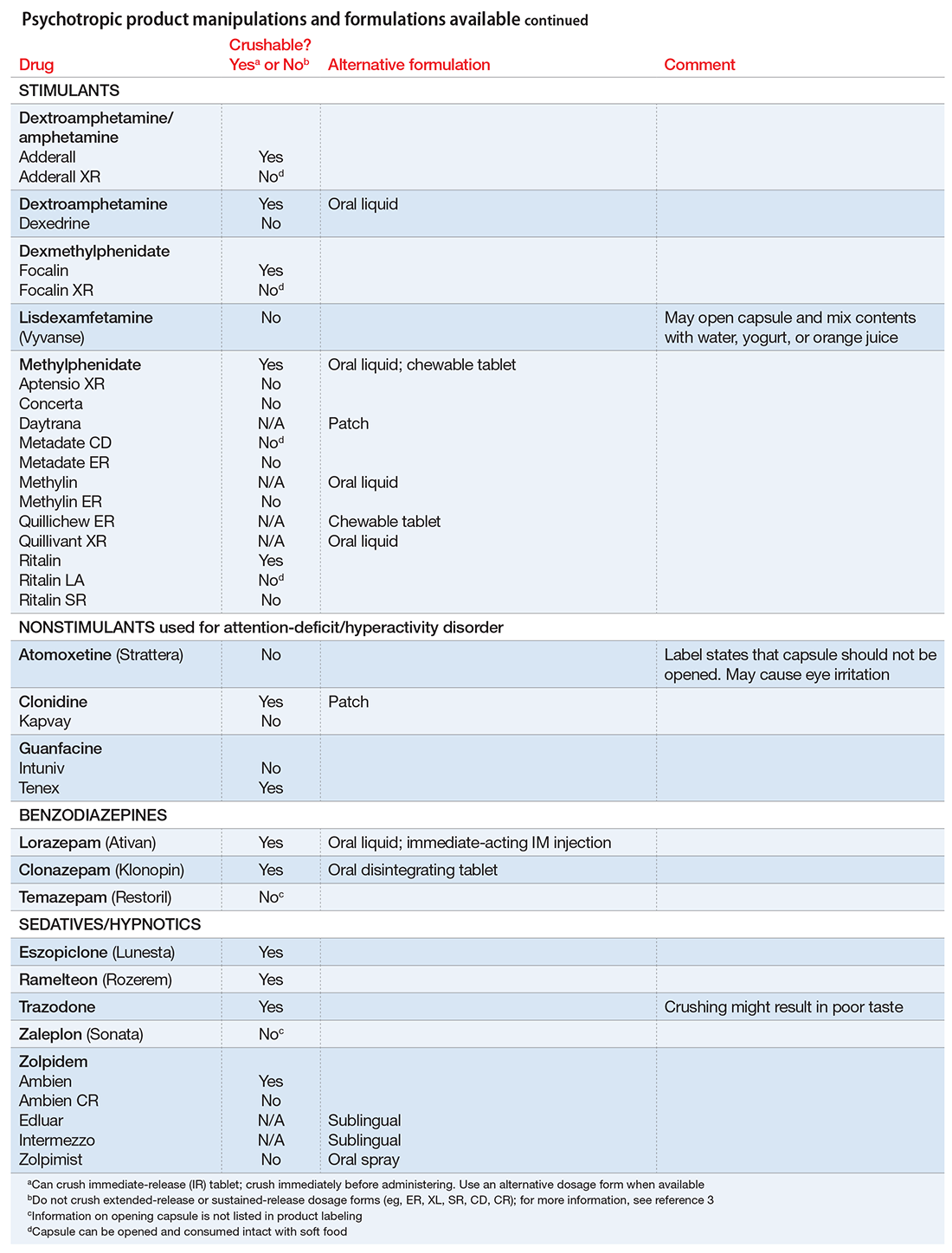

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

- Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

- Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

- Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

- Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

- Capsules generally can be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

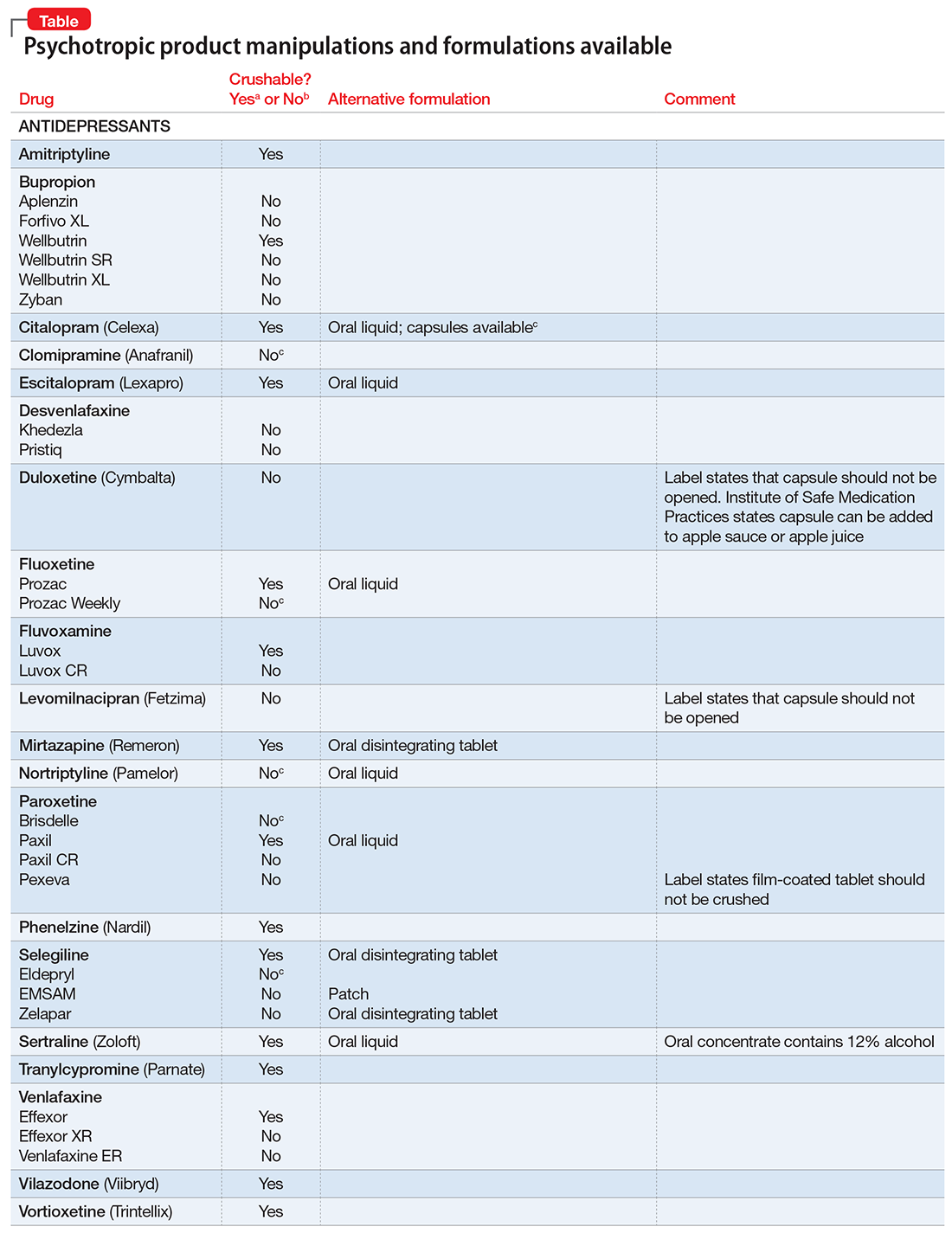

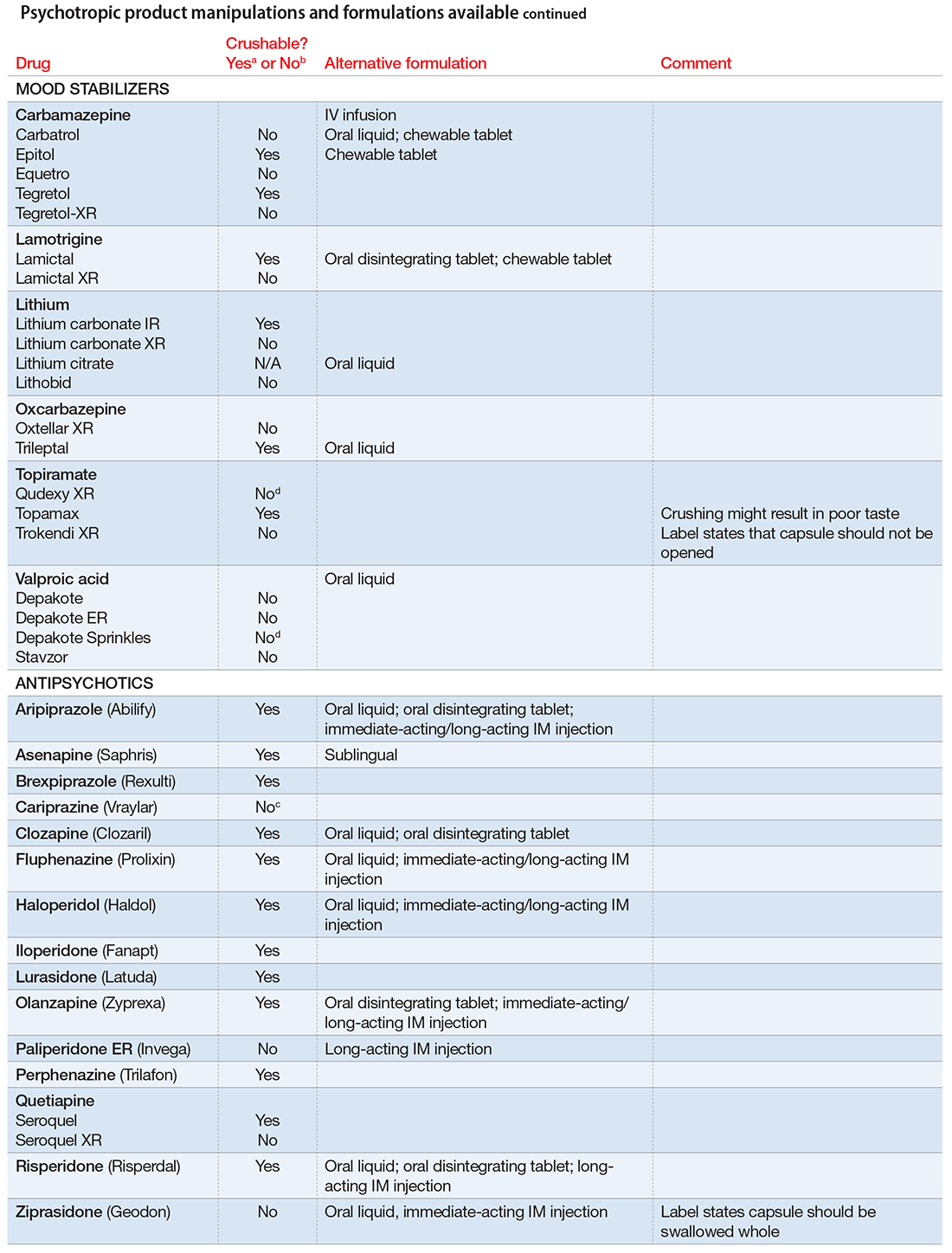

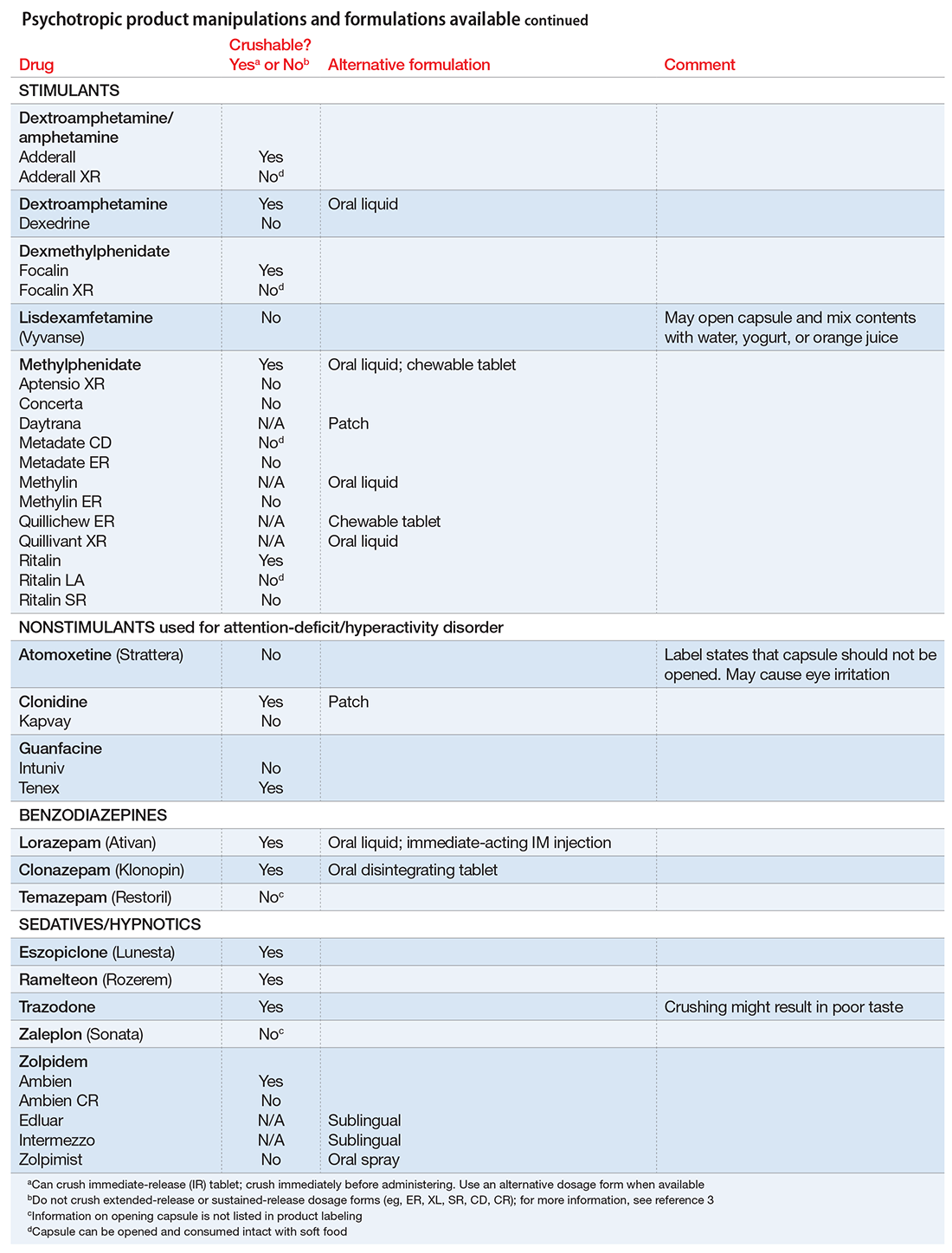

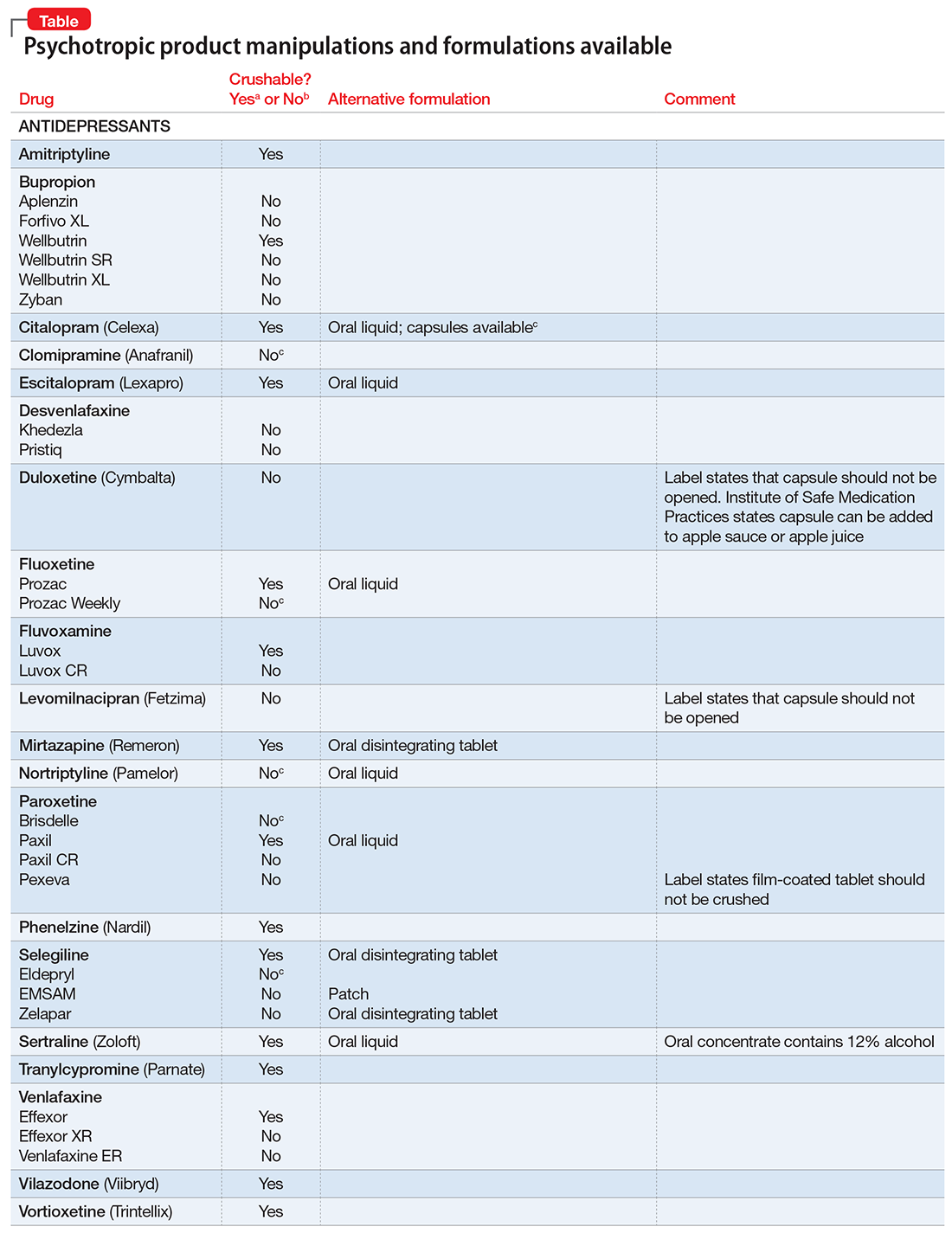

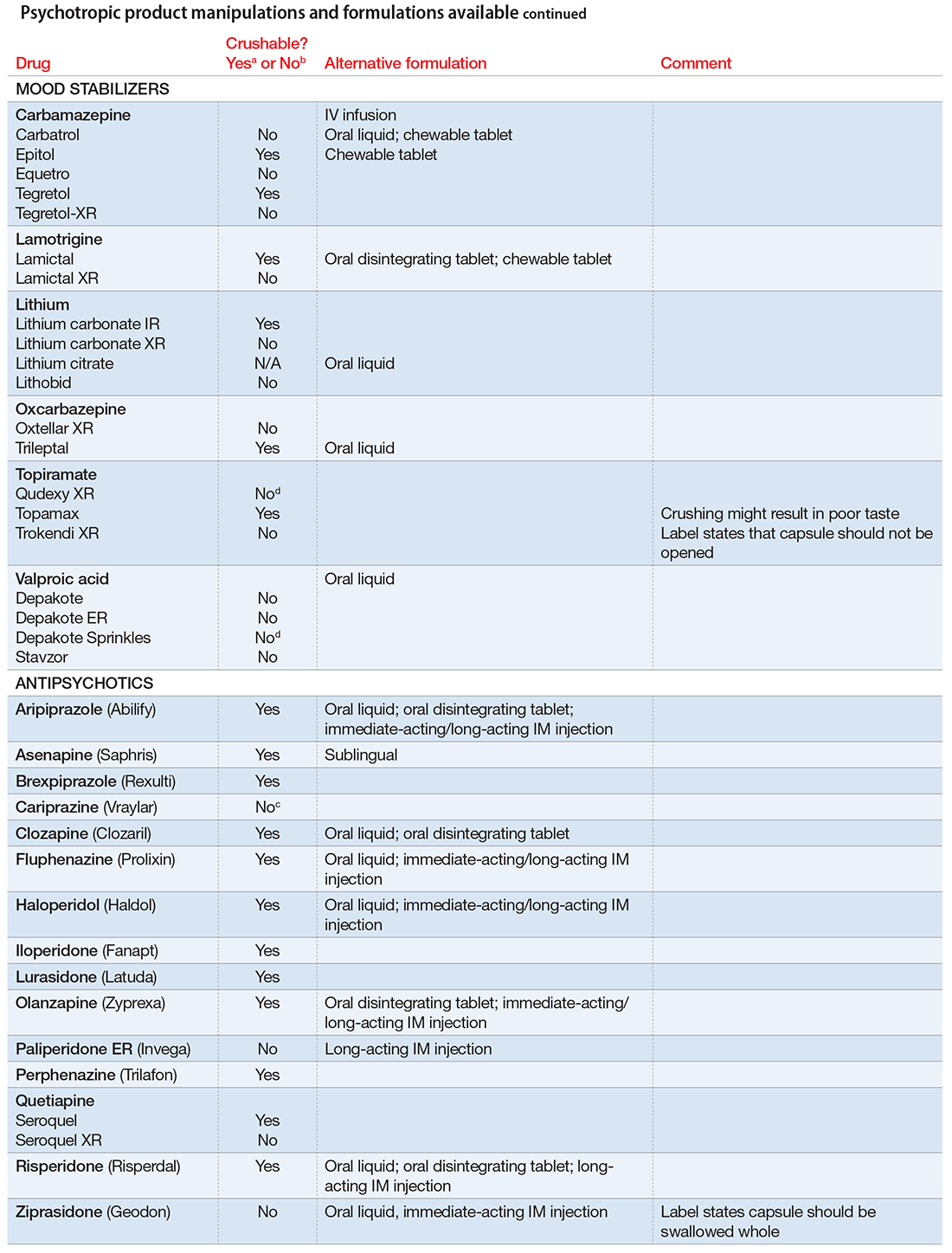

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’sLetter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp.org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2015. Accessed January 17, 2017.

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

- discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

- postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

- dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

- odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

- a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

- Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

- Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

- Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

- Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

- Capsules generally can be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

- discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

- postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

- dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

- odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

- a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

- Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

- Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

- Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

- Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

- Capsules generally can be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’sLetter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp.org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2015. Accessed January 17, 2017.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’sLetter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp.org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2015. Accessed January 17, 2017.

Opportunities to partner with clinical pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry

In this article, we highlight key steps that were needed to integrate clinical pharmacy specialists at an academic ambulatory psychiatric and addiction treatment center that serves pediatric and adult populations. Academic stakeholders identified addition of pharmacy services as a strategic goal in an effort to maximize services offered by the center and increase patient access to care while aligning with the standards set out by the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model.

We outline the role of clinical pharmacists in the care of adult patients in ambulatory psychiatry, illustrate opportunities to enhance patient care, point out possible challenges with implementation, and propose future initiatives to optimize the practitioner-pharmacist partnership.

Background: Role of ambulatory pharmacists in psychiatry

Clinical pharmacists’ role in the psychiatric ambulatory care setting generally is associated with positive outcomes. One study looking at a collaborative care model that utilized clinical pharmacist follow-up in managing major depressive disorder found that patients who received pharmacist intervention in the collaborative care model had, on average, a significantly higher adherence rate and patient satisfaction score than the “usual care” group.1 Within this study, patients in both groups experienced global clinical improvement with no significant difference; however, pharmacist interventions had a positive impact on several aspects of the care model, suggesting that pharmacists can be used effectively in ambulatory psychiatry.

Furthermore, a systematic study evaluating pharmacists’ impact on clinical and functional mental health outcomes identified 8 relevant studies conducted in the outpatient setting.2 Although interventions varied widely, most studies focused on pharmacists’ providing a combination of drug monitoring, treatment recommendations, and patient education. Outcomes were largely positive, including an overall reduction in number and dosage of psychiatric drugs, inferred cost savings, and significant improvements in the safe and efficacious use of antidepressant and antipsychotic medications.

These preliminary positive results require replication in larger, randomized cohorts. Additionally, the role of the pharmacist as medication manager in the collaborative care model requires further study. Results so far, however, indicate that pharmacists can have a positive impact on the care of ambulatory psychiatry patients. Nevertheless, there is still considerable need for ongoing exploration in this field.

Pre-implementation

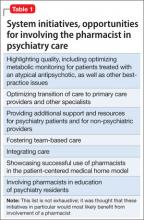

The need for pharmacy services. Various initiatives and existing practices within our health care system have underscored the need for a psychiatric pharmacist in the outpatient setting (Table 1).

A board-certified psychiatric pharmacist (BCPP) possesses specialized knowledge about treating patients affected by psychiatric illnesses. BCPPs work with prescribers and members of other disciplines, such as nurses and social workers, to optimize drug treatment by making pharmacotherapeutic recommendations and providing appropriate monitoring to enhance patient satisfaction and quality of life.3,4

Existing relationship with pharmacy. Along with evidence to support the positive impact clinical pharmacists can have in caring for patients with mental illness in the outpatient setting, a strong existing relationship between the Department of Psychiatry and our adult inpatient psychiatric pharmacist helped make it possible to develop an ambulatory psychiatric pharmacist position.

Each day, the inpatient psychiatric pharmacist works closely with the attending psychiatrists and psychiatry residents to provide treatment recommendations and counseling services for patients on the unit. The psychiatry residents highly valued their experiences with the pharmacist in the inpatient setting and expressed disappointment that this collaborative relationship was no longer available after they transitioned into the ambulatory setting.

Further, by being involved in initiatives that were relevant to both inpatient and outpatient psychiatry, such as metabolic monitoring for patients taking atypical antipsychotics, the clinical pharmacist in inpatient psychiatry had the opportunity to interact with key stakeholders in both settings. As a result of these pre-existing collaborative relationships, many clinicians were eager to have pharmacists available as a resource for patient care in the outpatient setting.

Pharmacist perspective: Outreach to psychiatry leadershipRecognizing the incentives and opportunities inherent in our emerging health care system, pharmacists became integral members of the patient care team in the PCMH model. Thanks to this effort, we now have PCMH pharmacists at every primary care health center in our health system (14 sites), providing disease management programs and polypharmacy services.

PCMH pharmacists’ role in the primary care setting fueled interest from specialty services and created opportunities to extend our existing partnership in inpatient psychiatry. One such opportunity to demonstrate the expertise of a psychiatric pharmacist was fueled by the FDA’s citalopram dosing alert5 at a system-wide level. This warning emerged as a chance to showcase the skill set of psychiatric pharmacists and the pharmacists’ successes in our PCMH model. The partnership was extended to include the buy-in of ambulatory pharmacy leadership and key stakeholders in ambulatory psychiatry.

Initial meetings included ambulatory care site leadership in psychiatry to increase awareness and understanding of pharmacists’ potential role in direct patient care. Achieving site leadership support was critical to successful implementation of pharmacist services in psychiatry. We also obtained approval from the Chair of the Department of Psychiatry to elicit support from faculty group practice.

Psychiatry leadership perspective

As fiscal pressures intensify at academic health centers, it becomes increasingly important for resources to be used as efficiently and effectively as possible. As a greater percentage of mental health patients with more “straightforward,” less complex conditions are being managed by their primary care providers or nonprescribing psychotherapists, or both, the acuity and complexity of cases in patients who present to psychiatric clinics have intensified. This intensification of patient needs and clinical acuity is in heightened conflict with the ongoing demand for clinician productivity and efficiency.

Additionally, the need to provide care to a seemingly ever-growing number of moderately or severely ill patients during shorter, less frequent visits presents a daunting task for clinicians and clinical leaders. Collaborative care models appear to offer the best hope for managing the seemingly overwhelming demand for services.

In this model, the patient, who is the critical member of the team, is expected to become an “expert” on his or her illness and to partner with members of the multidisciplinary team; with this support, patients are encouraged to develop a broad range of self-management skills and strategies to manage their illness. We believe that clinical pharmacists can and should play a critical role, not only in delivering direct clinical services to patients but also in developing and devising the care models that will most effectively apply each team member’s unique set of knowledge, skills, and experience. Given the large percentage of our patients who have multiple medical comorbidities and who require complex medical and psychiatric medication regimens, the role of the pharmacist in reviewing, educating, and advising patients and other team members on these crucial pharmacy concerns will be paramount.

In light of these complex medication issues, pharmacists are uniquely positioned to serve as a liaison among the patient, the primary care provider, and other members of their treatment team. We anticipate that our ambulatory psychiatry pharmacists will greatly enhance the comfort and confidence of patients and their primary care providers during periods of care transition.

Potential roles for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry

One potential role for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry is to perform polypharmacy assessments of patients receiving complex medication regimens, prompted by physician referral. The poly pharmacy intake interview, performed to obtain an accurate medication list and to identify patients’ concerns about their medications, can be conducted in person or by telephone. Patients’ knowledge about medications and medication adherence are discussed, as are their perceptions of effectiveness and adverse effects.

After initial data gathering, pharmacists complete a review of the medications, identifying any problems associated with medication indication, efficacy, tolerance, or adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, drug-nutrient interactions, and nonadherence. Pharmacists work to reduce medication costs if that is a concern of the patient, because nonadherence can result. A medication care plan is then developed in consultation with the primary care provider; here, the medication list is reconciled, the electronic medical record is updated, and actions to address any medication-related problems are prioritized.

Other services that might be offered include:• group education classes, based on patient motivational interviewing strategies, to address therapeutic nonadherence and to improve understanding of their disease and treatment regimens• medication safety and monitoring• treatment intensification, as needed, following established protocols.

These are a few of the ways in which pharmacists can be relied on to expand and improve access to patient care services within ambulatory psychiatry. Key stakeholders anticipate development of newer ideas as the pharmacist’s role in ambulatory psychiatry is increasingly clarified.

Reimbursement model

In creating a role for pharmacy in ambulatory psychiatry, it was essential that the model be financially viable and appealing. Alongside its clinical model, our institution has developed a financial model to support the pharmacist’s role. The lump-sum payment to the health centers from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan afforded the ambulatory care clinics an opportunity to invest in PCMH pharmacists. This funding, and the reimbursement based on T-code billing (face-to-face visits and phone consultation) for depression and other conditions requiring chronic care, provides ongoing support. From our experience, understanding physician reimbursement models and identifying relevant changes in health care reform are necessary to integrate new providers, including pharmacists, into a team-based care model.

Implementation

Promoting pharmacy services. To foster anticipated collaboration with clinical pharmacists, the medical director of outpatient psychiatry disseminated an announcement to all providers regarding the investiture of clinical pharmacists to support patient care activities, education, and research. Clinicians were educated about the pharmacists’ potential roles and about guidelines and methods for referral. Use of our electronic health record system enabled us to establish a relatively simple referral process involving sharing electronic messages with our pharmacists.

Further, as part of the planned integration of clinical pharmacists in the ambulatory psychiatry setting, pharmacists met strategically with members of various disciplines, clinical programs, specialty clinic programs, and teams throughout the center. In addition to answering questions about the referral process, they emphasized the role of pharmacy and opportunities for collaboration.

Collaborating with others. Because the involvement of clinical pharmacists is unfamiliar to some practitioners in outpatient psychiatry, it is important to develop services without infringing on the roles other disciplines play. Indeed, a survey by Wheeler et al6 identified many concerns and potential boundaries among pharmacists, other providers, and patients. Concerns included confusion of practitioner roles and boundaries, a too-traditional perception of the pharmacist, and demonstration of competence.6

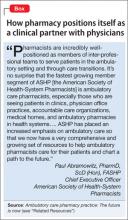

Early on, we developed a structured forum to discuss ongoing challenges and address issues related to the rapidly changing clinical landscape. During these discussions we conveyed that adding pharmacists to psychiatric services would be collaborative in nature and intended to augment existing services. This communication was pivotal to maintain the psychiatrist’s role as the ultimate prescriber and authority in the care of their patients; however, the pharmacist’s expertise, when sought, would help spur clinical and academic discussion that will benefit the patient. These discussions are paramount to achieving a productive, team-based approach, to overcome challenges, and to identify opportunities of value to our providers and patients (Box).

Work in progress

Implementing change in any clinical setting invariably creates challenges, and our endeavors to integrate clinical pharmacists into ambulatory psychiatry are no exception. We have identified several factors that we believe will optimize successful collaboration between pharmacy and ambulatory psychiatry (Table 2). Our primary challenge has been changing clinician behavior. Clinical practitioners can become too comfortable, wedded to their routines, and often are understandably resistant to change. Additionally, clinical systems often are inadvertently designed to obstruct change in ways that are not readily apparent. Efforts must be focused on behaviors and practices the clinical culture should encourage.

Regarding specific initiatives, clinical pharmacists have successfully identified patients on higher than recommended dosages of citalopram; they are working alongside prescribers to recommend ways to minimize the risk of heart rhythm abnormalities in these patients. Numerous prescribers have sought clinical pharmacists’ input to manage pharmacotherapy in their patients and to respond to patients’ questions on drug information.

The prospect of access to clinical pharmacist expertise in the outpatient setting was heralded with excitement, but the flow of referrals and consultations has been uneven. However simple the path for referral is, clinicians’ use of the system has been inconsistent—perhaps because of referrals’ passive, clinician-dependent nature. Educational outreach efforts often prompt a brief spike in referrals, only to be followed over time by a slow, steady drop-off. More active strategies will be needed, such as embedding the pharmacists as regular, active, visible members of the various clinical teams, and implementing a system in which patient record reviews are assigned to the pharmacists according to agreed-upon clusters of clinical criteria.

One of these tactics has, in the short term, showed success. Embedded in one of our newer clinics, which were designed to bridge primary and psychiatric care, clinical pharmacists are helping manage medically complicated patients. They assist with medication selection in light of drug interactions and medical comorbidities, conduct detailed medication histories, schedule follow-up visits to assess medication adherence and tolerability, and counsel patients experiencing insurance changes that make their medications less affordable. Integrating pharmacists in the new clinics has resulted in a steady flow of patient referrals and collaborative care work.

Clinical pharmacists are brainstorming with outpatient psychiatry leadership to build on these early successes. Ongoing communication and enhanced collaboration are essential, and can only improve the lives of our psychiatric patients.

For the future

Our partnership in ambulatory psychiatry was timed to occur during implementation of our health system’s new electronic health record initiative. Clinical pharmacists can play a key role in demonstrating use of the system to provide consistently accurate drug information to patients and to monitor patients receiving specific medications.

Development of ambulatory patient medication education groups, which has proved useful on the inpatient side, is another endeavor in the works. Integrating the clinical pharmacist with psychiatrists, psychologists, nurse practitioners, social workers, and trainees on specific teams devoted to depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, perinatal mental health, and personality disorders also might prove to be a wide-ranging and promising strategy.

Enhancing the education and training experiences of residents, fellows, medical students, pharmacy students, and allied health professional learners present in our clinics is another exciting prospect. This cross-disciplinary training will yield a new generation of providers who will be more comfortable collaborating with colleagues from other disciplines, all intent on providing high-quality, efficient care. We hope that, as these initiatives take root, we will recognize many opportunities to disseminate our collaborative efforts in scholarly venues, documenting and sharing the positive impact of our partnership.

Bottom Line

Because psychiatric outpatients present with challenging medical comorbidities and increasingly complex medication regimens, specialized clinical pharmacists can enrich the management team by offering essential monitoring and polypharmacy services, patient education and counseling, and cross-discipline training. At one academic treatment center, psychiatric and non-psychiatric practitioners are gradually buying in to these promising collaborative efforts.

Related Resources

• Board of Pharmacy Specialties. www.bpsweb.org/specialties/psychiatric.cfm.

• Abramowitz P. Ambulatory care pharmacy practice: The future is now. www.connect.ashp.org/blogs/paul-abramowitz/2014/05/14/ambulatory-care-pharmacy-practice-the-future-is-now.

Drug Brand Name

Citalopram • Celexa

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, et al. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(9):1175-1185.

2. Finley PR, Crismon ML, Rush AJ. Evaluating the impact of pharmacists in mental health: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(12):1634-1644.

3. Board of Pharmacy Specialties. http://www.bpsweb. org. Accessed June 4, 2014.

4. Cohen LJ. The role of neuropsychiatric pharmacists. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 19):54-57.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Abnormal heart rhythms associated with high doses of Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm297391. htm. Accessed June 4, 2014.

6. Wheeler A, Crump K, Lee M, et al. Collaborative prescribing: a qualitative exploration of a role for pharmacists in mental health. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012;8(3):179-192.

In this article, we highlight key steps that were needed to integrate clinical pharmacy specialists at an academic ambulatory psychiatric and addiction treatment center that serves pediatric and adult populations. Academic stakeholders identified addition of pharmacy services as a strategic goal in an effort to maximize services offered by the center and increase patient access to care while aligning with the standards set out by the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model.

We outline the role of clinical pharmacists in the care of adult patients in ambulatory psychiatry, illustrate opportunities to enhance patient care, point out possible challenges with implementation, and propose future initiatives to optimize the practitioner-pharmacist partnership.

Background: Role of ambulatory pharmacists in psychiatry

Clinical pharmacists’ role in the psychiatric ambulatory care setting generally is associated with positive outcomes. One study looking at a collaborative care model that utilized clinical pharmacist follow-up in managing major depressive disorder found that patients who received pharmacist intervention in the collaborative care model had, on average, a significantly higher adherence rate and patient satisfaction score than the “usual care” group.1 Within this study, patients in both groups experienced global clinical improvement with no significant difference; however, pharmacist interventions had a positive impact on several aspects of the care model, suggesting that pharmacists can be used effectively in ambulatory psychiatry.

Furthermore, a systematic study evaluating pharmacists’ impact on clinical and functional mental health outcomes identified 8 relevant studies conducted in the outpatient setting.2 Although interventions varied widely, most studies focused on pharmacists’ providing a combination of drug monitoring, treatment recommendations, and patient education. Outcomes were largely positive, including an overall reduction in number and dosage of psychiatric drugs, inferred cost savings, and significant improvements in the safe and efficacious use of antidepressant and antipsychotic medications.

These preliminary positive results require replication in larger, randomized cohorts. Additionally, the role of the pharmacist as medication manager in the collaborative care model requires further study. Results so far, however, indicate that pharmacists can have a positive impact on the care of ambulatory psychiatry patients. Nevertheless, there is still considerable need for ongoing exploration in this field.

Pre-implementation

The need for pharmacy services. Various initiatives and existing practices within our health care system have underscored the need for a psychiatric pharmacist in the outpatient setting (Table 1).

A board-certified psychiatric pharmacist (BCPP) possesses specialized knowledge about treating patients affected by psychiatric illnesses. BCPPs work with prescribers and members of other disciplines, such as nurses and social workers, to optimize drug treatment by making pharmacotherapeutic recommendations and providing appropriate monitoring to enhance patient satisfaction and quality of life.3,4

Existing relationship with pharmacy. Along with evidence to support the positive impact clinical pharmacists can have in caring for patients with mental illness in the outpatient setting, a strong existing relationship between the Department of Psychiatry and our adult inpatient psychiatric pharmacist helped make it possible to develop an ambulatory psychiatric pharmacist position.

Each day, the inpatient psychiatric pharmacist works closely with the attending psychiatrists and psychiatry residents to provide treatment recommendations and counseling services for patients on the unit. The psychiatry residents highly valued their experiences with the pharmacist in the inpatient setting and expressed disappointment that this collaborative relationship was no longer available after they transitioned into the ambulatory setting.

Further, by being involved in initiatives that were relevant to both inpatient and outpatient psychiatry, such as metabolic monitoring for patients taking atypical antipsychotics, the clinical pharmacist in inpatient psychiatry had the opportunity to interact with key stakeholders in both settings. As a result of these pre-existing collaborative relationships, many clinicians were eager to have pharmacists available as a resource for patient care in the outpatient setting.

Pharmacist perspective: Outreach to psychiatry leadershipRecognizing the incentives and opportunities inherent in our emerging health care system, pharmacists became integral members of the patient care team in the PCMH model. Thanks to this effort, we now have PCMH pharmacists at every primary care health center in our health system (14 sites), providing disease management programs and polypharmacy services.

PCMH pharmacists’ role in the primary care setting fueled interest from specialty services and created opportunities to extend our existing partnership in inpatient psychiatry. One such opportunity to demonstrate the expertise of a psychiatric pharmacist was fueled by the FDA’s citalopram dosing alert5 at a system-wide level. This warning emerged as a chance to showcase the skill set of psychiatric pharmacists and the pharmacists’ successes in our PCMH model. The partnership was extended to include the buy-in of ambulatory pharmacy leadership and key stakeholders in ambulatory psychiatry.

Initial meetings included ambulatory care site leadership in psychiatry to increase awareness and understanding of pharmacists’ potential role in direct patient care. Achieving site leadership support was critical to successful implementation of pharmacist services in psychiatry. We also obtained approval from the Chair of the Department of Psychiatry to elicit support from faculty group practice.

Psychiatry leadership perspective

As fiscal pressures intensify at academic health centers, it becomes increasingly important for resources to be used as efficiently and effectively as possible. As a greater percentage of mental health patients with more “straightforward,” less complex conditions are being managed by their primary care providers or nonprescribing psychotherapists, or both, the acuity and complexity of cases in patients who present to psychiatric clinics have intensified. This intensification of patient needs and clinical acuity is in heightened conflict with the ongoing demand for clinician productivity and efficiency.

Additionally, the need to provide care to a seemingly ever-growing number of moderately or severely ill patients during shorter, less frequent visits presents a daunting task for clinicians and clinical leaders. Collaborative care models appear to offer the best hope for managing the seemingly overwhelming demand for services.

In this model, the patient, who is the critical member of the team, is expected to become an “expert” on his or her illness and to partner with members of the multidisciplinary team; with this support, patients are encouraged to develop a broad range of self-management skills and strategies to manage their illness. We believe that clinical pharmacists can and should play a critical role, not only in delivering direct clinical services to patients but also in developing and devising the care models that will most effectively apply each team member’s unique set of knowledge, skills, and experience. Given the large percentage of our patients who have multiple medical comorbidities and who require complex medical and psychiatric medication regimens, the role of the pharmacist in reviewing, educating, and advising patients and other team members on these crucial pharmacy concerns will be paramount.

In light of these complex medication issues, pharmacists are uniquely positioned to serve as a liaison among the patient, the primary care provider, and other members of their treatment team. We anticipate that our ambulatory psychiatry pharmacists will greatly enhance the comfort and confidence of patients and their primary care providers during periods of care transition.

Potential roles for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry

One potential role for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry is to perform polypharmacy assessments of patients receiving complex medication regimens, prompted by physician referral. The poly pharmacy intake interview, performed to obtain an accurate medication list and to identify patients’ concerns about their medications, can be conducted in person or by telephone. Patients’ knowledge about medications and medication adherence are discussed, as are their perceptions of effectiveness and adverse effects.

After initial data gathering, pharmacists complete a review of the medications, identifying any problems associated with medication indication, efficacy, tolerance, or adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, drug-nutrient interactions, and nonadherence. Pharmacists work to reduce medication costs if that is a concern of the patient, because nonadherence can result. A medication care plan is then developed in consultation with the primary care provider; here, the medication list is reconciled, the electronic medical record is updated, and actions to address any medication-related problems are prioritized.

Other services that might be offered include:• group education classes, based on patient motivational interviewing strategies, to address therapeutic nonadherence and to improve understanding of their disease and treatment regimens• medication safety and monitoring• treatment intensification, as needed, following established protocols.

These are a few of the ways in which pharmacists can be relied on to expand and improve access to patient care services within ambulatory psychiatry. Key stakeholders anticipate development of newer ideas as the pharmacist’s role in ambulatory psychiatry is increasingly clarified.

Reimbursement model

In creating a role for pharmacy in ambulatory psychiatry, it was essential that the model be financially viable and appealing. Alongside its clinical model, our institution has developed a financial model to support the pharmacist’s role. The lump-sum payment to the health centers from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan afforded the ambulatory care clinics an opportunity to invest in PCMH pharmacists. This funding, and the reimbursement based on T-code billing (face-to-face visits and phone consultation) for depression and other conditions requiring chronic care, provides ongoing support. From our experience, understanding physician reimbursement models and identifying relevant changes in health care reform are necessary to integrate new providers, including pharmacists, into a team-based care model.

Implementation

Promoting pharmacy services. To foster anticipated collaboration with clinical pharmacists, the medical director of outpatient psychiatry disseminated an announcement to all providers regarding the investiture of clinical pharmacists to support patient care activities, education, and research. Clinicians were educated about the pharmacists’ potential roles and about guidelines and methods for referral. Use of our electronic health record system enabled us to establish a relatively simple referral process involving sharing electronic messages with our pharmacists.

Further, as part of the planned integration of clinical pharmacists in the ambulatory psychiatry setting, pharmacists met strategically with members of various disciplines, clinical programs, specialty clinic programs, and teams throughout the center. In addition to answering questions about the referral process, they emphasized the role of pharmacy and opportunities for collaboration.

Collaborating with others. Because the involvement of clinical pharmacists is unfamiliar to some practitioners in outpatient psychiatry, it is important to develop services without infringing on the roles other disciplines play. Indeed, a survey by Wheeler et al6 identified many concerns and potential boundaries among pharmacists, other providers, and patients. Concerns included confusion of practitioner roles and boundaries, a too-traditional perception of the pharmacist, and demonstration of competence.6

Early on, we developed a structured forum to discuss ongoing challenges and address issues related to the rapidly changing clinical landscape. During these discussions we conveyed that adding pharmacists to psychiatric services would be collaborative in nature and intended to augment existing services. This communication was pivotal to maintain the psychiatrist’s role as the ultimate prescriber and authority in the care of their patients; however, the pharmacist’s expertise, when sought, would help spur clinical and academic discussion that will benefit the patient. These discussions are paramount to achieving a productive, team-based approach, to overcome challenges, and to identify opportunities of value to our providers and patients (Box).

Work in progress

Implementing change in any clinical setting invariably creates challenges, and our endeavors to integrate clinical pharmacists into ambulatory psychiatry are no exception. We have identified several factors that we believe will optimize successful collaboration between pharmacy and ambulatory psychiatry (Table 2). Our primary challenge has been changing clinician behavior. Clinical practitioners can become too comfortable, wedded to their routines, and often are understandably resistant to change. Additionally, clinical systems often are inadvertently designed to obstruct change in ways that are not readily apparent. Efforts must be focused on behaviors and practices the clinical culture should encourage.

Regarding specific initiatives, clinical pharmacists have successfully identified patients on higher than recommended dosages of citalopram; they are working alongside prescribers to recommend ways to minimize the risk of heart rhythm abnormalities in these patients. Numerous prescribers have sought clinical pharmacists’ input to manage pharmacotherapy in their patients and to respond to patients’ questions on drug information.

The prospect of access to clinical pharmacist expertise in the outpatient setting was heralded with excitement, but the flow of referrals and consultations has been uneven. However simple the path for referral is, clinicians’ use of the system has been inconsistent—perhaps because of referrals’ passive, clinician-dependent nature. Educational outreach efforts often prompt a brief spike in referrals, only to be followed over time by a slow, steady drop-off. More active strategies will be needed, such as embedding the pharmacists as regular, active, visible members of the various clinical teams, and implementing a system in which patient record reviews are assigned to the pharmacists according to agreed-upon clusters of clinical criteria.

One of these tactics has, in the short term, showed success. Embedded in one of our newer clinics, which were designed to bridge primary and psychiatric care, clinical pharmacists are helping manage medically complicated patients. They assist with medication selection in light of drug interactions and medical comorbidities, conduct detailed medication histories, schedule follow-up visits to assess medication adherence and tolerability, and counsel patients experiencing insurance changes that make their medications less affordable. Integrating pharmacists in the new clinics has resulted in a steady flow of patient referrals and collaborative care work.

Clinical pharmacists are brainstorming with outpatient psychiatry leadership to build on these early successes. Ongoing communication and enhanced collaboration are essential, and can only improve the lives of our psychiatric patients.

For the future

Our partnership in ambulatory psychiatry was timed to occur during implementation of our health system’s new electronic health record initiative. Clinical pharmacists can play a key role in demonstrating use of the system to provide consistently accurate drug information to patients and to monitor patients receiving specific medications.

Development of ambulatory patient medication education groups, which has proved useful on the inpatient side, is another endeavor in the works. Integrating the clinical pharmacist with psychiatrists, psychologists, nurse practitioners, social workers, and trainees on specific teams devoted to depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, perinatal mental health, and personality disorders also might prove to be a wide-ranging and promising strategy.

Enhancing the education and training experiences of residents, fellows, medical students, pharmacy students, and allied health professional learners present in our clinics is another exciting prospect. This cross-disciplinary training will yield a new generation of providers who will be more comfortable collaborating with colleagues from other disciplines, all intent on providing high-quality, efficient care. We hope that, as these initiatives take root, we will recognize many opportunities to disseminate our collaborative efforts in scholarly venues, documenting and sharing the positive impact of our partnership.

Bottom Line

Because psychiatric outpatients present with challenging medical comorbidities and increasingly complex medication regimens, specialized clinical pharmacists can enrich the management team by offering essential monitoring and polypharmacy services, patient education and counseling, and cross-discipline training. At one academic treatment center, psychiatric and non-psychiatric practitioners are gradually buying in to these promising collaborative efforts.

Related Resources

• Board of Pharmacy Specialties. www.bpsweb.org/specialties/psychiatric.cfm.

• Abramowitz P. Ambulatory care pharmacy practice: The future is now. www.connect.ashp.org/blogs/paul-abramowitz/2014/05/14/ambulatory-care-pharmacy-practice-the-future-is-now.

Drug Brand Name

Citalopram • Celexa

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

In this article, we highlight key steps that were needed to integrate clinical pharmacy specialists at an academic ambulatory psychiatric and addiction treatment center that serves pediatric and adult populations. Academic stakeholders identified addition of pharmacy services as a strategic goal in an effort to maximize services offered by the center and increase patient access to care while aligning with the standards set out by the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model.

We outline the role of clinical pharmacists in the care of adult patients in ambulatory psychiatry, illustrate opportunities to enhance patient care, point out possible challenges with implementation, and propose future initiatives to optimize the practitioner-pharmacist partnership.

Background: Role of ambulatory pharmacists in psychiatry

Clinical pharmacists’ role in the psychiatric ambulatory care setting generally is associated with positive outcomes. One study looking at a collaborative care model that utilized clinical pharmacist follow-up in managing major depressive disorder found that patients who received pharmacist intervention in the collaborative care model had, on average, a significantly higher adherence rate and patient satisfaction score than the “usual care” group.1 Within this study, patients in both groups experienced global clinical improvement with no significant difference; however, pharmacist interventions had a positive impact on several aspects of the care model, suggesting that pharmacists can be used effectively in ambulatory psychiatry.

Furthermore, a systematic study evaluating pharmacists’ impact on clinical and functional mental health outcomes identified 8 relevant studies conducted in the outpatient setting.2 Although interventions varied widely, most studies focused on pharmacists’ providing a combination of drug monitoring, treatment recommendations, and patient education. Outcomes were largely positive, including an overall reduction in number and dosage of psychiatric drugs, inferred cost savings, and significant improvements in the safe and efficacious use of antidepressant and antipsychotic medications.

These preliminary positive results require replication in larger, randomized cohorts. Additionally, the role of the pharmacist as medication manager in the collaborative care model requires further study. Results so far, however, indicate that pharmacists can have a positive impact on the care of ambulatory psychiatry patients. Nevertheless, there is still considerable need for ongoing exploration in this field.

Pre-implementation

The need for pharmacy services. Various initiatives and existing practices within our health care system have underscored the need for a psychiatric pharmacist in the outpatient setting (Table 1).

A board-certified psychiatric pharmacist (BCPP) possesses specialized knowledge about treating patients affected by psychiatric illnesses. BCPPs work with prescribers and members of other disciplines, such as nurses and social workers, to optimize drug treatment by making pharmacotherapeutic recommendations and providing appropriate monitoring to enhance patient satisfaction and quality of life.3,4

Existing relationship with pharmacy. Along with evidence to support the positive impact clinical pharmacists can have in caring for patients with mental illness in the outpatient setting, a strong existing relationship between the Department of Psychiatry and our adult inpatient psychiatric pharmacist helped make it possible to develop an ambulatory psychiatric pharmacist position.

Each day, the inpatient psychiatric pharmacist works closely with the attending psychiatrists and psychiatry residents to provide treatment recommendations and counseling services for patients on the unit. The psychiatry residents highly valued their experiences with the pharmacist in the inpatient setting and expressed disappointment that this collaborative relationship was no longer available after they transitioned into the ambulatory setting.

Further, by being involved in initiatives that were relevant to both inpatient and outpatient psychiatry, such as metabolic monitoring for patients taking atypical antipsychotics, the clinical pharmacist in inpatient psychiatry had the opportunity to interact with key stakeholders in both settings. As a result of these pre-existing collaborative relationships, many clinicians were eager to have pharmacists available as a resource for patient care in the outpatient setting.

Pharmacist perspective: Outreach to psychiatry leadershipRecognizing the incentives and opportunities inherent in our emerging health care system, pharmacists became integral members of the patient care team in the PCMH model. Thanks to this effort, we now have PCMH pharmacists at every primary care health center in our health system (14 sites), providing disease management programs and polypharmacy services.

PCMH pharmacists’ role in the primary care setting fueled interest from specialty services and created opportunities to extend our existing partnership in inpatient psychiatry. One such opportunity to demonstrate the expertise of a psychiatric pharmacist was fueled by the FDA’s citalopram dosing alert5 at a system-wide level. This warning emerged as a chance to showcase the skill set of psychiatric pharmacists and the pharmacists’ successes in our PCMH model. The partnership was extended to include the buy-in of ambulatory pharmacy leadership and key stakeholders in ambulatory psychiatry.

Initial meetings included ambulatory care site leadership in psychiatry to increase awareness and understanding of pharmacists’ potential role in direct patient care. Achieving site leadership support was critical to successful implementation of pharmacist services in psychiatry. We also obtained approval from the Chair of the Department of Psychiatry to elicit support from faculty group practice.

Psychiatry leadership perspective

As fiscal pressures intensify at academic health centers, it becomes increasingly important for resources to be used as efficiently and effectively as possible. As a greater percentage of mental health patients with more “straightforward,” less complex conditions are being managed by their primary care providers or nonprescribing psychotherapists, or both, the acuity and complexity of cases in patients who present to psychiatric clinics have intensified. This intensification of patient needs and clinical acuity is in heightened conflict with the ongoing demand for clinician productivity and efficiency.

Additionally, the need to provide care to a seemingly ever-growing number of moderately or severely ill patients during shorter, less frequent visits presents a daunting task for clinicians and clinical leaders. Collaborative care models appear to offer the best hope for managing the seemingly overwhelming demand for services.

In this model, the patient, who is the critical member of the team, is expected to become an “expert” on his or her illness and to partner with members of the multidisciplinary team; with this support, patients are encouraged to develop a broad range of self-management skills and strategies to manage their illness. We believe that clinical pharmacists can and should play a critical role, not only in delivering direct clinical services to patients but also in developing and devising the care models that will most effectively apply each team member’s unique set of knowledge, skills, and experience. Given the large percentage of our patients who have multiple medical comorbidities and who require complex medical and psychiatric medication regimens, the role of the pharmacist in reviewing, educating, and advising patients and other team members on these crucial pharmacy concerns will be paramount.

In light of these complex medication issues, pharmacists are uniquely positioned to serve as a liaison among the patient, the primary care provider, and other members of their treatment team. We anticipate that our ambulatory psychiatry pharmacists will greatly enhance the comfort and confidence of patients and their primary care providers during periods of care transition.

Potential roles for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry

One potential role for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry is to perform polypharmacy assessments of patients receiving complex medication regimens, prompted by physician referral. The poly pharmacy intake interview, performed to obtain an accurate medication list and to identify patients’ concerns about their medications, can be conducted in person or by telephone. Patients’ knowledge about medications and medication adherence are discussed, as are their perceptions of effectiveness and adverse effects.

After initial data gathering, pharmacists complete a review of the medications, identifying any problems associated with medication indication, efficacy, tolerance, or adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, drug-nutrient interactions, and nonadherence. Pharmacists work to reduce medication costs if that is a concern of the patient, because nonadherence can result. A medication care plan is then developed in consultation with the primary care provider; here, the medication list is reconciled, the electronic medical record is updated, and actions to address any medication-related problems are prioritized.

Other services that might be offered include:• group education classes, based on patient motivational interviewing strategies, to address therapeutic nonadherence and to improve understanding of their disease and treatment regimens• medication safety and monitoring• treatment intensification, as needed, following established protocols.

These are a few of the ways in which pharmacists can be relied on to expand and improve access to patient care services within ambulatory psychiatry. Key stakeholders anticipate development of newer ideas as the pharmacist’s role in ambulatory psychiatry is increasingly clarified.

Reimbursement model

In creating a role for pharmacy in ambulatory psychiatry, it was essential that the model be financially viable and appealing. Alongside its clinical model, our institution has developed a financial model to support the pharmacist’s role. The lump-sum payment to the health centers from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan afforded the ambulatory care clinics an opportunity to invest in PCMH pharmacists. This funding, and the reimbursement based on T-code billing (face-to-face visits and phone consultation) for depression and other conditions requiring chronic care, provides ongoing support. From our experience, understanding physician reimbursement models and identifying relevant changes in health care reform are necessary to integrate new providers, including pharmacists, into a team-based care model.

Implementation

Promoting pharmacy services. To foster anticipated collaboration with clinical pharmacists, the medical director of outpatient psychiatry disseminated an announcement to all providers regarding the investiture of clinical pharmacists to support patient care activities, education, and research. Clinicians were educated about the pharmacists’ potential roles and about guidelines and methods for referral. Use of our electronic health record system enabled us to establish a relatively simple referral process involving sharing electronic messages with our pharmacists.

Further, as part of the planned integration of clinical pharmacists in the ambulatory psychiatry setting, pharmacists met strategically with members of various disciplines, clinical programs, specialty clinic programs, and teams throughout the center. In addition to answering questions about the referral process, they emphasized the role of pharmacy and opportunities for collaboration.

Collaborating with others. Because the involvement of clinical pharmacists is unfamiliar to some practitioners in outpatient psychiatry, it is important to develop services without infringing on the roles other disciplines play. Indeed, a survey by Wheeler et al6 identified many concerns and potential boundaries among pharmacists, other providers, and patients. Concerns included confusion of practitioner roles and boundaries, a too-traditional perception of the pharmacist, and demonstration of competence.6

Early on, we developed a structured forum to discuss ongoing challenges and address issues related to the rapidly changing clinical landscape. During these discussions we conveyed that adding pharmacists to psychiatric services would be collaborative in nature and intended to augment existing services. This communication was pivotal to maintain the psychiatrist’s role as the ultimate prescriber and authority in the care of their patients; however, the pharmacist’s expertise, when sought, would help spur clinical and academic discussion that will benefit the patient. These discussions are paramount to achieving a productive, team-based approach, to overcome challenges, and to identify opportunities of value to our providers and patients (Box).

Work in progress

Implementing change in any clinical setting invariably creates challenges, and our endeavors to integrate clinical pharmacists into ambulatory psychiatry are no exception. We have identified several factors that we believe will optimize successful collaboration between pharmacy and ambulatory psychiatry (Table 2). Our primary challenge has been changing clinician behavior. Clinical practitioners can become too comfortable, wedded to their routines, and often are understandably resistant to change. Additionally, clinical systems often are inadvertently designed to obstruct change in ways that are not readily apparent. Efforts must be focused on behaviors and practices the clinical culture should encourage.

Regarding specific initiatives, clinical pharmacists have successfully identified patients on higher than recommended dosages of citalopram; they are working alongside prescribers to recommend ways to minimize the risk of heart rhythm abnormalities in these patients. Numerous prescribers have sought clinical pharmacists’ input to manage pharmacotherapy in their patients and to respond to patients’ questions on drug information.

The prospect of access to clinical pharmacist expertise in the outpatient setting was heralded with excitement, but the flow of referrals and consultations has been uneven. However simple the path for referral is, clinicians’ use of the system has been inconsistent—perhaps because of referrals’ passive, clinician-dependent nature. Educational outreach efforts often prompt a brief spike in referrals, only to be followed over time by a slow, steady drop-off. More active strategies will be needed, such as embedding the pharmacists as regular, active, visible members of the various clinical teams, and implementing a system in which patient record reviews are assigned to the pharmacists according to agreed-upon clusters of clinical criteria.

One of these tactics has, in the short term, showed success. Embedded in one of our newer clinics, which were designed to bridge primary and psychiatric care, clinical pharmacists are helping manage medically complicated patients. They assist with medication selection in light of drug interactions and medical comorbidities, conduct detailed medication histories, schedule follow-up visits to assess medication adherence and tolerability, and counsel patients experiencing insurance changes that make their medications less affordable. Integrating pharmacists in the new clinics has resulted in a steady flow of patient referrals and collaborative care work.

Clinical pharmacists are brainstorming with outpatient psychiatry leadership to build on these early successes. Ongoing communication and enhanced collaboration are essential, and can only improve the lives of our psychiatric patients.

For the future

Our partnership in ambulatory psychiatry was timed to occur during implementation of our health system’s new electronic health record initiative. Clinical pharmacists can play a key role in demonstrating use of the system to provide consistently accurate drug information to patients and to monitor patients receiving specific medications.

Development of ambulatory patient medication education groups, which has proved useful on the inpatient side, is another endeavor in the works. Integrating the clinical pharmacist with psychiatrists, psychologists, nurse practitioners, social workers, and trainees on specific teams devoted to depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, perinatal mental health, and personality disorders also might prove to be a wide-ranging and promising strategy.

Enhancing the education and training experiences of residents, fellows, medical students, pharmacy students, and allied health professional learners present in our clinics is another exciting prospect. This cross-disciplinary training will yield a new generation of providers who will be more comfortable collaborating with colleagues from other disciplines, all intent on providing high-quality, efficient care. We hope that, as these initiatives take root, we will recognize many opportunities to disseminate our collaborative efforts in scholarly venues, documenting and sharing the positive impact of our partnership.

Bottom Line

Because psychiatric outpatients present with challenging medical comorbidities and increasingly complex medication regimens, specialized clinical pharmacists can enrich the management team by offering essential monitoring and polypharmacy services, patient education and counseling, and cross-discipline training. At one academic treatment center, psychiatric and non-psychiatric practitioners are gradually buying in to these promising collaborative efforts.

Related Resources

• Board of Pharmacy Specialties. www.bpsweb.org/specialties/psychiatric.cfm.

• Abramowitz P. Ambulatory care pharmacy practice: The future is now. www.connect.ashp.org/blogs/paul-abramowitz/2014/05/14/ambulatory-care-pharmacy-practice-the-future-is-now.

Drug Brand Name

Citalopram • Celexa

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, et al. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(9):1175-1185.

2. Finley PR, Crismon ML, Rush AJ. Evaluating the impact of pharmacists in mental health: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(12):1634-1644.

3. Board of Pharmacy Specialties. http://www.bpsweb. org. Accessed June 4, 2014.

4. Cohen LJ. The role of neuropsychiatric pharmacists. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 19):54-57.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Abnormal heart rhythms associated with high doses of Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm297391. htm. Accessed June 4, 2014.

6. Wheeler A, Crump K, Lee M, et al. Collaborative prescribing: a qualitative exploration of a role for pharmacists in mental health. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012;8(3):179-192.

1. Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, et al. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(9):1175-1185.

2. Finley PR, Crismon ML, Rush AJ. Evaluating the impact of pharmacists in mental health: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(12):1634-1644.

3. Board of Pharmacy Specialties. http://www.bpsweb. org. Accessed June 4, 2014.

4. Cohen LJ. The role of neuropsychiatric pharmacists. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 19):54-57.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Abnormal heart rhythms associated with high doses of Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm297391. htm. Accessed June 4, 2014.

6. Wheeler A, Crump K, Lee M, et al. Collaborative prescribing: a qualitative exploration of a role for pharmacists in mental health. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012;8(3):179-192.

Pills to powder: A clinician’s reference for crushable psychotropic medications

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

• discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

• postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

• dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

• odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

• a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

• Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

• Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

• Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

• Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

• Capsules can generally be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp. org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2014. Accessed March 13, 2014.

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

• discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

• postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

• dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

• odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

• a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

• Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

• Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

• Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

• Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

• Capsules can generally be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

• discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

• postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

• dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

• odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

• a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

• Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

• Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

• Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

• Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

• Capsules can generally be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp. org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2014. Accessed March 13, 2014.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp. org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2014. Accessed March 13, 2014.

Benzodiazepines: A versatile clinical tool

Since the discovery of chlordiazepoxide in the 1950s, benzodiazepines have revolutionized the treatment of anxiety and insomnia, largely because of their improved safety profile compared with barbiturates, formerly the preferred sedative-hypnotic.1 In addition to their anxiolytic and sedative-hypnotic effects, benzodiazepines exhibit anterograde amnesia, anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxant properties.1 Psychiatrists use benzodiazepines to treat anxiety and sleep disorders, acute agitation, alcohol withdrawal, catatonia, and psychotropic side effects such as akathisia. This article highlights the evidence for using benzodiazepines in anxiety and other disorders and why they generally should not be used for obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (Box 1).

Current evidence indicates little support for using benzodiazepines for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the World Federation of Biological Psychiatry do not recommend benzodiazepines for treating OCD because of a lack of evidence for efficacy.a,b An earlier study suggested clonazepam monotherapy was effective for OCDc; however, a more recent study did not show a benefit on rate of response or degree of symptom improvement.d Augmentation strategies with benzodiazepines also do not appear to be beneficial for OCD management. A recent double-blind, placebo-controlled study failed to demonstrate faster symptom improvement by augmenting sertraline with clonazepam, although the study had a small sample size and high drop-out rate.e

Because benzodiazepines have negligible action on core posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other agents largely have supplanted them for PTSD treatment.f Use of benzodiazepines for PTSD is associated with withdrawal symptoms, more severe symptoms after discontinuation, and possible disinhibition, and may interfere with patients’ efforts to integrate trauma experiences. Although benzodiazepines may reduce distress associated with acute trauma, there is evidence—in clinical studies and animal models—that early benzodiazepine administration fails to prevent PTSD and may increase its incidence.g The International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety, the APA, and the British Association for Psychopharmacology all highlight the limited role, if any, for benzodiazepines in PTSD.h-j

References

- Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders - first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2008;9(4):248-312.

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2007.

- Hewlett WA, Vinogradov S, Agras WS. Clomipramine, clonazepam, and clonidine treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;12(6):420-430.

- Hollander E, Kaplan A, Stahl SM. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of clonazepam in obsessive-compulsive disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2003;4(1):30-34.

- Crockett BA, Churchill E, Davidson JR. A double-blind combination study of clonazepam and sertraline in OCD. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16(3):127-132.

- Argyropoulos SV, Sandford JJ, Nutt DJ. The psychobiology of anxiolytic drugs. Part 2: pharmacological treatments of anxiety. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;88(3):213-227.

- Matar MA, Zohar J, Kaplan Z, et al. Alprazolam treatment immediately after stress exposure interferes with the normal HPA-stress response and increases vulnerability to subsequent stress in an animal model of PTSD. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19(4):283-295.

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JR, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement update on posttraumatic stress disorder from the international consensus group on depression and anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 1):55-62.

- Ursano RJ, Bell C, Eth S, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11 suppl):3-31.

- Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(6):567-596.

Pharmacokinetic properties

Most benzodiazepines are considered to have similar efficacy; therefore, selection is based on pharmacokinetic considerations. Table 1 compares the indication, onset, and half-life of 12 commonly used benzodiazepines.2-6 Although Table 1 lists approximate equivalent doses, studies report inconsistent data. These are approximations only and should not be used independently to make therapy decisions.

Table 1

Oral benzodiazepines: Indications, onset, half-life, and equivalent doses

| Drug | FDA-approved indication(s) | Onset of action | Approximate half-life (hours) in healthy adults | Approximate equivalent dose (mg)a | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alprazolam | Anxiety disorders, panic disorder | Intermediate | 6.3 to 26.9 (IR), 10.7 to 15.8 (XR) | 0.5 | Increased risk for abuse because of greater lipid solubility |