User login

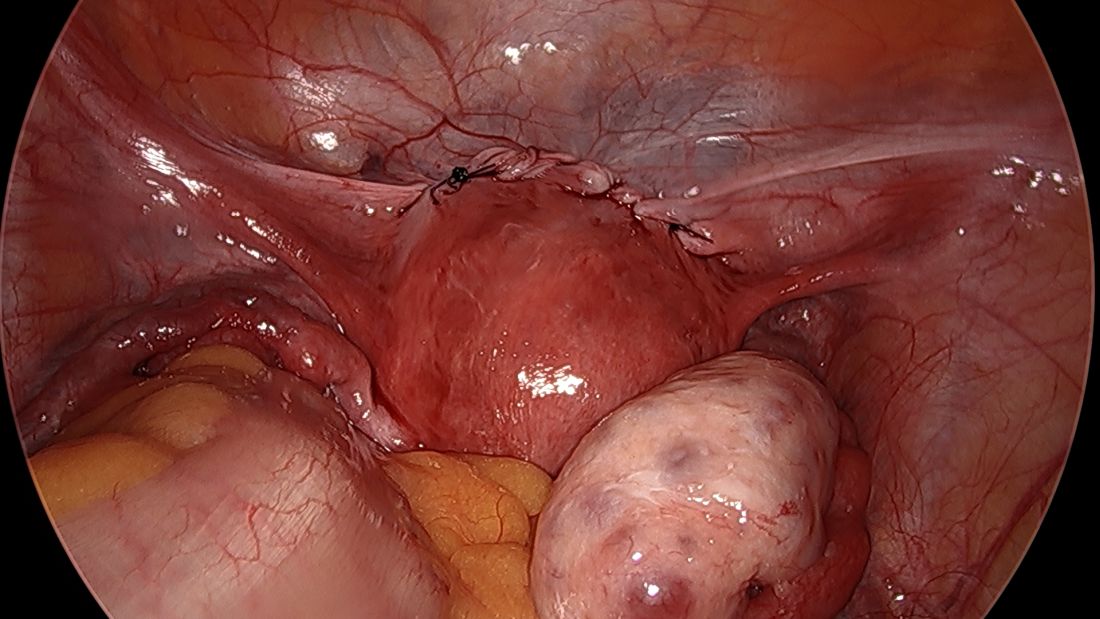

Sacral nerve root endometriosis

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Laparoscopic abdominal cerclage: An effective, patient-sought approach for cervical insufficiency

Cervical insufficiency is an important cause of preterm birth and complicates up to 1% of pregnancies. It is typically diagnosed as painless cervical dilation without contractions, often in the second trimester at around 16-18 weeks, but the clinical presentation can be variable. In some cases, a rescue cerclage can be placed to prevent second trimester loss or preterm birth.

A recent landmark randomized controlled trial of abdominal vs. vaginal cerclage – the MAVRIC trial (Multicentre Abdominal vs. Vaginal Randomized Intervention of Cerclage)1 published in 2020 – has offered significant validation for the belief that an abdominal approach is the preferred approach for patients with cervical insufficiency and a prior failed vaginal cerclage.

Obstetricians traditionally have had a high threshold for placement of an abdominal cerclage given the need for cesarean delivery and the morbidity of an open procedure. Laparoscopic abdominal cerclage has lowered this threshold and is increasingly the preferred method for cerclage placement. Reported complication rates are generally lower than for open abdominal cerclage, and neonatal survival rates are similar or improved.

In our experience, the move toward laparoscopic abdominal cerclage is largely a patient-driven shift. Since 2007, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, we have performed over 150 laparoscopic abdominal cerclage placements. The majority of patients had at least one prior second-trimester loss (many of them had multiple losses), with many having also failed a transvaginal cerclage.

In an analysis of 137 of these cases published recently in Fertility and Sterility, the neonatal survival rate was 93.8% in the 80 pregnancies that followed and extended beyond the first trimester, and the mean gestational age at delivery was 36.9 weeks.2 (First trimester losses are typically excluded from the denominator because they are unlikely to be the result of cervical insufficiency.)

History and outcomes data

The vaginal cerclage has long been a mainstay of therapy because it is a simple procedure. The McDonald technique, described in the 1950s, uses a simple purse string suture at the cervico-vaginal juncture, and the Shirodkar approach, also described in the 1950s, involves placing the cerclage higher on the cervix, as close to the internal os as possible. The Shirodkar technique is more complex, requiring more dissection, and is used less often than the McDonald approach.

The abdominal cerclage, first reported in 1965,3 is placed higher on the cervix, right near the juncture of the lower uterine segment and the cervix, and has generally been thought to provide optimal integrity. It is this point of placement – right at the juncture where membranes begin protruding into the cervix as it shortens and softens – that offers the strongest defense against cervical insufficiency.

The laparoscopic abdominal approach has been gaining popularity since it was first reported in 1998.4 Its traditional indication has been after a prior failed vaginal cerclage or when the cervix is too short to place a vaginal cerclage – as a result of a congenital anomaly or cervical conization, for instance.

Some of my patients have had one pregnancy loss in which cervical insufficiency was suspected and have sought laparoscopic abdominal cerclage without attempting a vaginal cerclage. Data to support this scenario are unavailable, but given the psychological trauma of pregnancy loss and the minimally invasive and low-risk nature of laparoscopic abdominal cerclage, I have been inclined to agree to preventive laparoscopic abdominal procedures without a trial of a vaginal cerclage. I believe this is a reasonable option.

The recently published MAVRIC trial included only abdominal cerclages performed using an open approach, but it provides good data for the scenario in which a vaginal cerclage has failed.

The rates of preterm birth at less than 32 weeks were significantly lower with abdominal cerclage than with low vaginal cerclage (McDonald technique) or high vaginal cerclage (Shirodkar technique) (8% vs. 33%, and 8% vs. 38%). No neonatal deaths occurred.

The analysis covered 111 women who conceived and had known pregnancy outcomes, out of 139 who were recruited and randomized. Cerclage placement occurred either between 10 and 16 weeks of gestation for vaginal cerclages and at 14 weeks for abdominal cerclages or before conception for those assigned to receive an abdominal or high vaginal cerclage.

Reviews of the literature done by our group1 and others have found equivalent outcomes between abdominal cerclages placed through laparotomy and through laparoscopy. The largest systematic review analyzed 31 studies involving 1,844 patients and found that neonatal survival rates were significantly greater in the laparoscopic group (97% vs. 90%), as were rates of deliveries after 34 weeks of gestation (83% vs. 76%).5

The better outcomes in the laparoscopic group may at least partly reflect improved laparoscopic surgeon techniques and improvements in neonatal care over time. At the minimum, we can conclude that neonatal outcomes are at least equivalent when an abdominal cerclage is placed through laparotomy or with a minimally invasive approach.

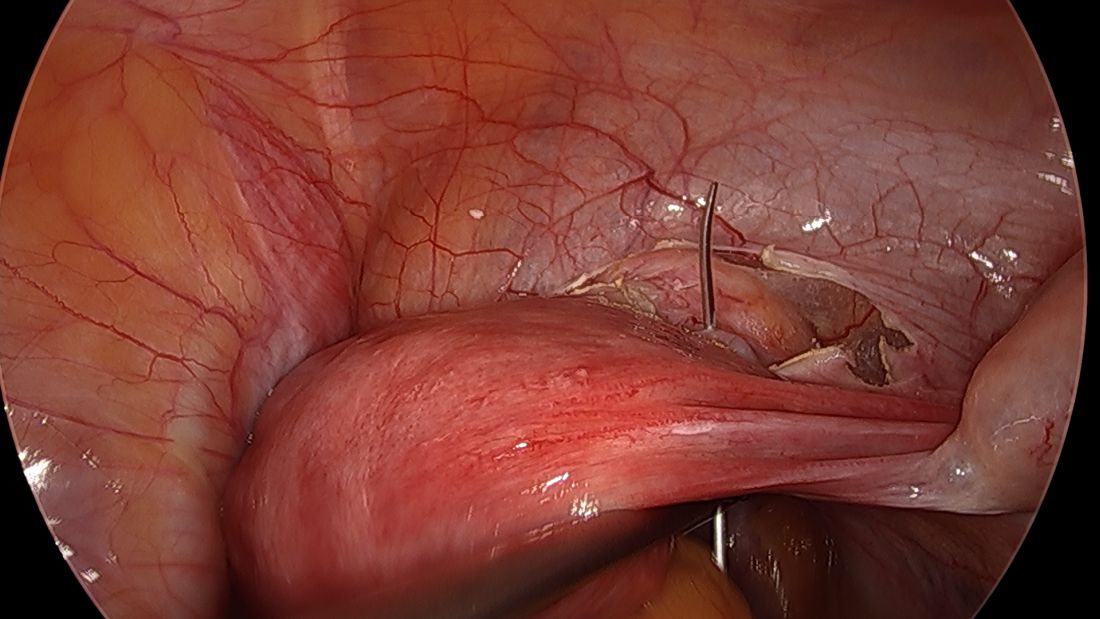

Our technique

Laparoscopic cerclages are much more easily placed – and with less risk of surgical complications or blood loss – in patients who are not pregnant. Postconception cerclage placement also carries a unique, small risk of fetal loss (estimated to occur in 1.2% of laparoscopic cases and 3% of open cases). 1 We therefore prefer to perform the procedure before pregnancy, though we do place abdominal cerclages in early pregnancy as well. (Approximately 10% of the 137 patients in our analysis were pregnant at the time of cerclage placement. 1 )

The procedure, described here for the nonpregnant patient, typically requires 3-4 ports. My preference is to use a 10-mm scope at the umbilicus, two 5-mm ipsilateral ports, and an additional 5-mm port for my assistant. We generally use a uterine manipulator to help with dissection and facilitate the correct angulation of the suture needle.

We start by opening the vesicouterine peritoneum to dissect the uterine arteries anteriorly and to move the bladder slightly caudad. It is not a significant dissection.

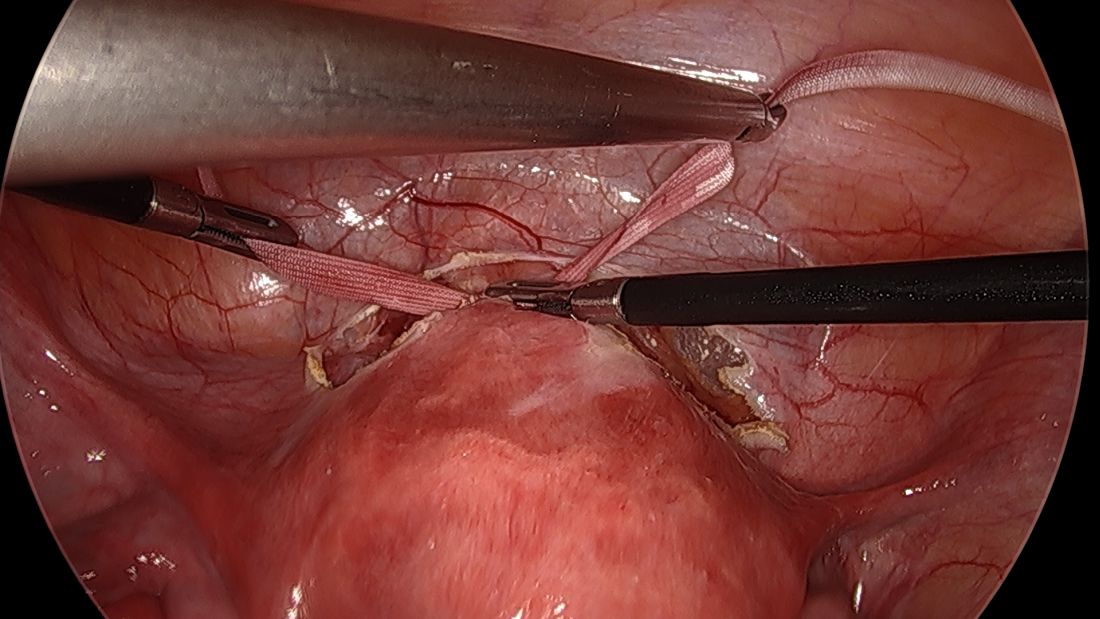

For suturing, we use 5-mm Mersilene polyester tape with blunt-tip needles – the same tape that is commonly used for vaginal cerclages. The needles (which probably are unnecessarily long for laparoscopic cerclages) are straightened out prior to insertion with robust needle holders.

The posterior broad ligament is not opened prior to insertion of the needle, as opening the broad ligament risks possible vessel injury and adds complexity.

Direct insertion of the needle simplifies the procedure and has not led to any complications thus far.

We prefer to insert the suture posteriorly at the level of the internal os just above the insertion of the uterosacral ligaments. It is helpful to view the uterus and cervix as an hourglass, with the level of the internal os is at the narrowest point of the hourglass.

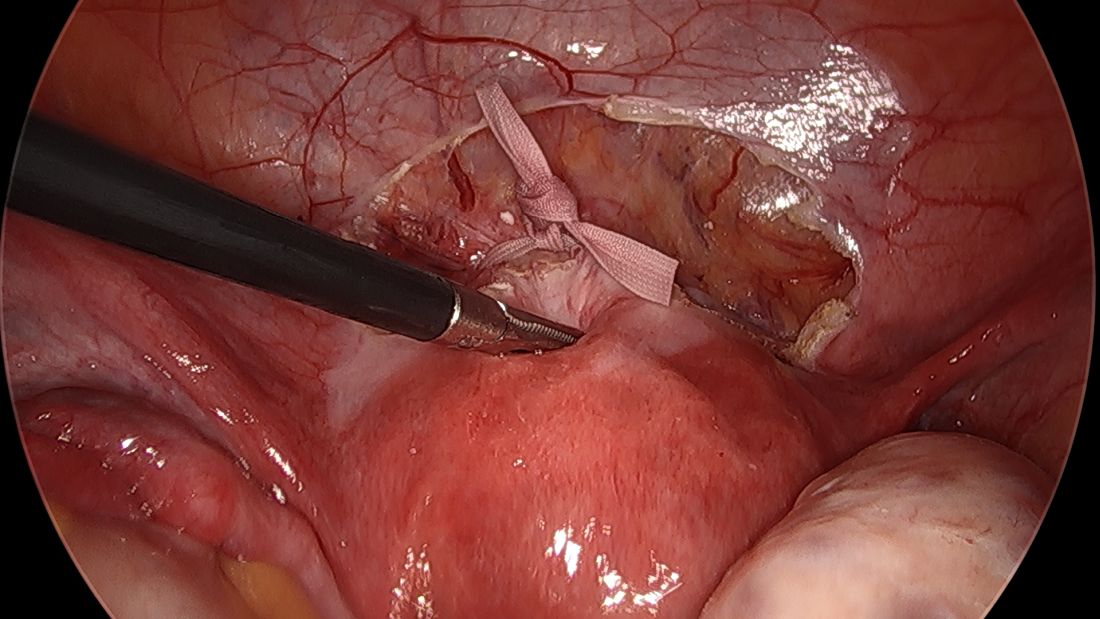

The suture is passed carefully between the uterine vessels and the cervical stroma. The uterine artery should be lateral to placement of the needle, and the uterosacral ligament should be below. The surgeon should see a pulsation of the uterine artery. The use of blunt needles is advantageous because, especially when newer to the procedure, the surgeon can place the needle in slightly more medial than may be deemed necessary so as to avert the uterine vessels, then adjust placement slightly more laterally if resistance is met.

Suture placement should follow a fairly low-impact path. Encountering too much resistance with the needle signals passage into the cervix and necessitates redirection of the needle with a slightly more lateral placement. Twisting the uterus with the uterine manipulator can be helpful throughout this process.

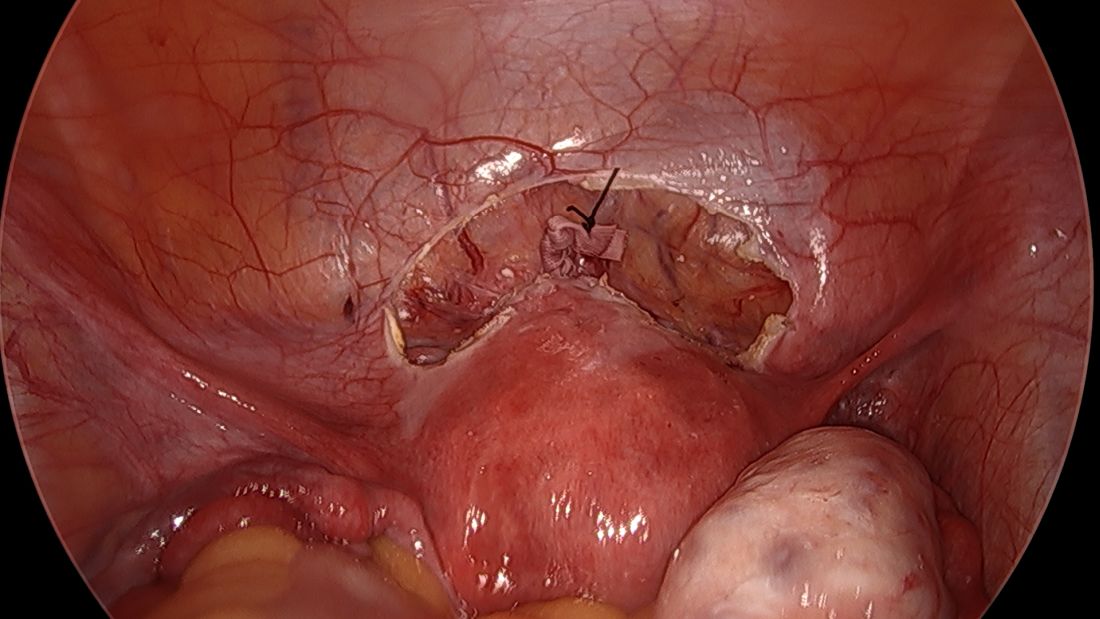

Once the needles are passed through, they are cut off the Mersilene tape and removed. For suturing, it’s important that the first and second knots are tied down snuggly and flat.

I usually ask my assistant to hold down the first knot so that it doesn’t unravel while I tie the second knot. I usually tie 6 square knots with the tape.

The edges of the tape are then trimmed, and with a 2.0 silk suture, the ends are secured to the lower uterine segment to prevent a theoretical risk of erosion into the bladder.

We then close the overlying vesicouterine peritoneum with 2-0 Monocryl suture, tying it intracorporally. Closing the peritoneum posteriorly is generally not necessary.

We have not had significant bleeding or severe complications in any of our cases. And while the literature comparing preconception and postconception abdominal cerclage is limited, the risks appear very low especially before pregnancy. Some oozing from the uterine vein can sometimes occur; if this does not resolve once it is tied down, placement of a simple figure of eight suture such as a Monocryl or Vicryl at the posterior insertion of the tape may be necessary to stop the bleeding.

Some surgeons place the abdominal cerclage lateral to the uterine artery, presumably to lessen any risk of vessel injury, but again, our placement medial to the vessels has not led to any significant bleeding. By doing so we are averting a theoretical risk with lateral placement of possibly constricting blood flow to the uterus during pregnancy.

Another technique for suturing that has been described uses a fascial closing device, which, after the needles are removed, passes between the vessels and cervix anteriorly and grasps each end of the suture posteriorly before pulling it through the cervix. My concern with this approach is that entry into the cervix with this device’s sharp needles could cause erosion of the tape into the cervical canal. Piercing of a vessel could also cause bleeding.

Laparoscopic abdominal cerclage can also be placed with robotic assistance, but I don’t believe that the robot offers any benefit for this relatively short, uncomplicated procedure.

A note on patient care

We recommend that patients not become pregnant for 2 months after the laparoscopic abdominal cerclage is placed, and that they receive obstetrical care as high-risk patients. The cerclage can be removed at the time of cesarean delivery if the patient has completed childbearing. Otherwise, if the cerclage appears normal, it can be left in place for future pregnancies.

In the event of a miscarriage, a dilatation and evacuation procedure can be performed with an abdominal cerclage in place, up to 18 weeks of pregnancy. Beyond this point, the patient likely will need to have the cerclage removed laparoscopically to allow vaginal passing of the fetus.

References

1. Shennan A et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(3):261.E1-261.E9.

2. Clark NV & Einarsson JI. Fertil Steril. 2020;113:717-22.

3. Benson RC & Durfee RB. Obstet Gynecol. 1965;25:145-55.

4. Lesser KB et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:855-6.

5. Moawad GN et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:277-86.

Cervical insufficiency is an important cause of preterm birth and complicates up to 1% of pregnancies. It is typically diagnosed as painless cervical dilation without contractions, often in the second trimester at around 16-18 weeks, but the clinical presentation can be variable. In some cases, a rescue cerclage can be placed to prevent second trimester loss or preterm birth.

A recent landmark randomized controlled trial of abdominal vs. vaginal cerclage – the MAVRIC trial (Multicentre Abdominal vs. Vaginal Randomized Intervention of Cerclage)1 published in 2020 – has offered significant validation for the belief that an abdominal approach is the preferred approach for patients with cervical insufficiency and a prior failed vaginal cerclage.

Obstetricians traditionally have had a high threshold for placement of an abdominal cerclage given the need for cesarean delivery and the morbidity of an open procedure. Laparoscopic abdominal cerclage has lowered this threshold and is increasingly the preferred method for cerclage placement. Reported complication rates are generally lower than for open abdominal cerclage, and neonatal survival rates are similar or improved.

In our experience, the move toward laparoscopic abdominal cerclage is largely a patient-driven shift. Since 2007, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, we have performed over 150 laparoscopic abdominal cerclage placements. The majority of patients had at least one prior second-trimester loss (many of them had multiple losses), with many having also failed a transvaginal cerclage.

In an analysis of 137 of these cases published recently in Fertility and Sterility, the neonatal survival rate was 93.8% in the 80 pregnancies that followed and extended beyond the first trimester, and the mean gestational age at delivery was 36.9 weeks.2 (First trimester losses are typically excluded from the denominator because they are unlikely to be the result of cervical insufficiency.)

History and outcomes data

The vaginal cerclage has long been a mainstay of therapy because it is a simple procedure. The McDonald technique, described in the 1950s, uses a simple purse string suture at the cervico-vaginal juncture, and the Shirodkar approach, also described in the 1950s, involves placing the cerclage higher on the cervix, as close to the internal os as possible. The Shirodkar technique is more complex, requiring more dissection, and is used less often than the McDonald approach.

The abdominal cerclage, first reported in 1965,3 is placed higher on the cervix, right near the juncture of the lower uterine segment and the cervix, and has generally been thought to provide optimal integrity. It is this point of placement – right at the juncture where membranes begin protruding into the cervix as it shortens and softens – that offers the strongest defense against cervical insufficiency.

The laparoscopic abdominal approach has been gaining popularity since it was first reported in 1998.4 Its traditional indication has been after a prior failed vaginal cerclage or when the cervix is too short to place a vaginal cerclage – as a result of a congenital anomaly or cervical conization, for instance.

Some of my patients have had one pregnancy loss in which cervical insufficiency was suspected and have sought laparoscopic abdominal cerclage without attempting a vaginal cerclage. Data to support this scenario are unavailable, but given the psychological trauma of pregnancy loss and the minimally invasive and low-risk nature of laparoscopic abdominal cerclage, I have been inclined to agree to preventive laparoscopic abdominal procedures without a trial of a vaginal cerclage. I believe this is a reasonable option.

The recently published MAVRIC trial included only abdominal cerclages performed using an open approach, but it provides good data for the scenario in which a vaginal cerclage has failed.

The rates of preterm birth at less than 32 weeks were significantly lower with abdominal cerclage than with low vaginal cerclage (McDonald technique) or high vaginal cerclage (Shirodkar technique) (8% vs. 33%, and 8% vs. 38%). No neonatal deaths occurred.

The analysis covered 111 women who conceived and had known pregnancy outcomes, out of 139 who were recruited and randomized. Cerclage placement occurred either between 10 and 16 weeks of gestation for vaginal cerclages and at 14 weeks for abdominal cerclages or before conception for those assigned to receive an abdominal or high vaginal cerclage.

Reviews of the literature done by our group1 and others have found equivalent outcomes between abdominal cerclages placed through laparotomy and through laparoscopy. The largest systematic review analyzed 31 studies involving 1,844 patients and found that neonatal survival rates were significantly greater in the laparoscopic group (97% vs. 90%), as were rates of deliveries after 34 weeks of gestation (83% vs. 76%).5

The better outcomes in the laparoscopic group may at least partly reflect improved laparoscopic surgeon techniques and improvements in neonatal care over time. At the minimum, we can conclude that neonatal outcomes are at least equivalent when an abdominal cerclage is placed through laparotomy or with a minimally invasive approach.

Our technique

Laparoscopic cerclages are much more easily placed – and with less risk of surgical complications or blood loss – in patients who are not pregnant. Postconception cerclage placement also carries a unique, small risk of fetal loss (estimated to occur in 1.2% of laparoscopic cases and 3% of open cases). 1 We therefore prefer to perform the procedure before pregnancy, though we do place abdominal cerclages in early pregnancy as well. (Approximately 10% of the 137 patients in our analysis were pregnant at the time of cerclage placement. 1 )

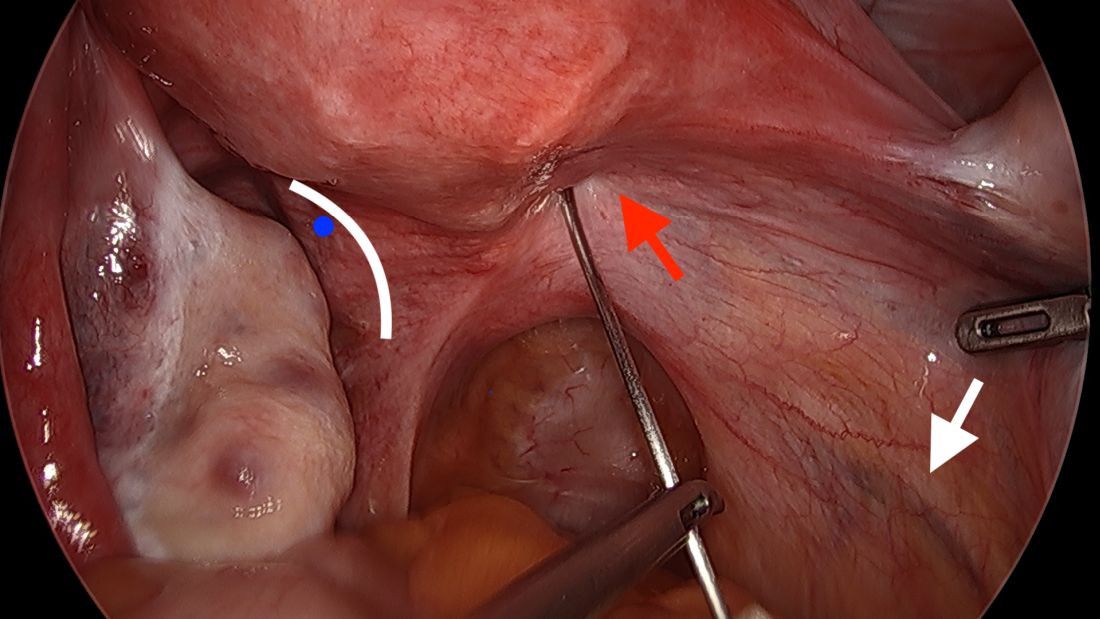

The procedure, described here for the nonpregnant patient, typically requires 3-4 ports. My preference is to use a 10-mm scope at the umbilicus, two 5-mm ipsilateral ports, and an additional 5-mm port for my assistant. We generally use a uterine manipulator to help with dissection and facilitate the correct angulation of the suture needle.

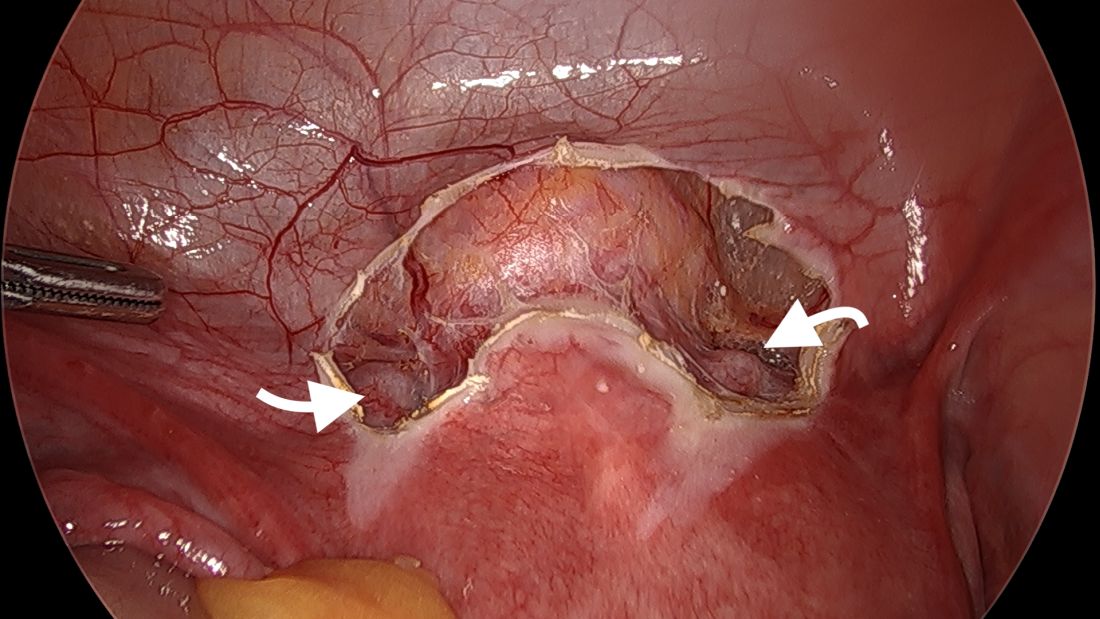

We start by opening the vesicouterine peritoneum to dissect the uterine arteries anteriorly and to move the bladder slightly caudad. It is not a significant dissection.

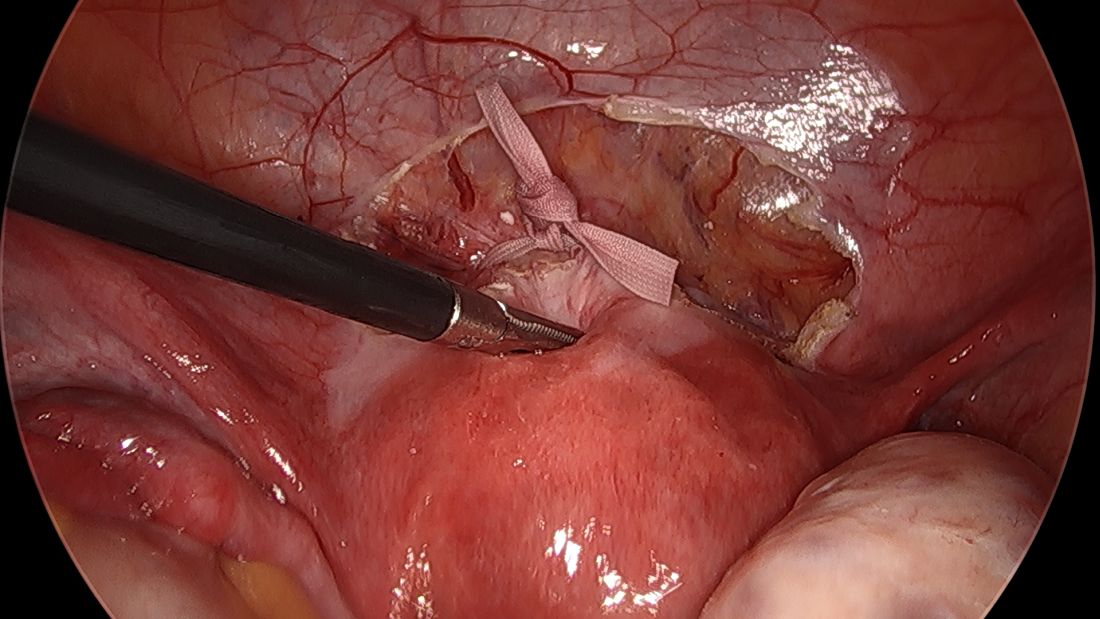

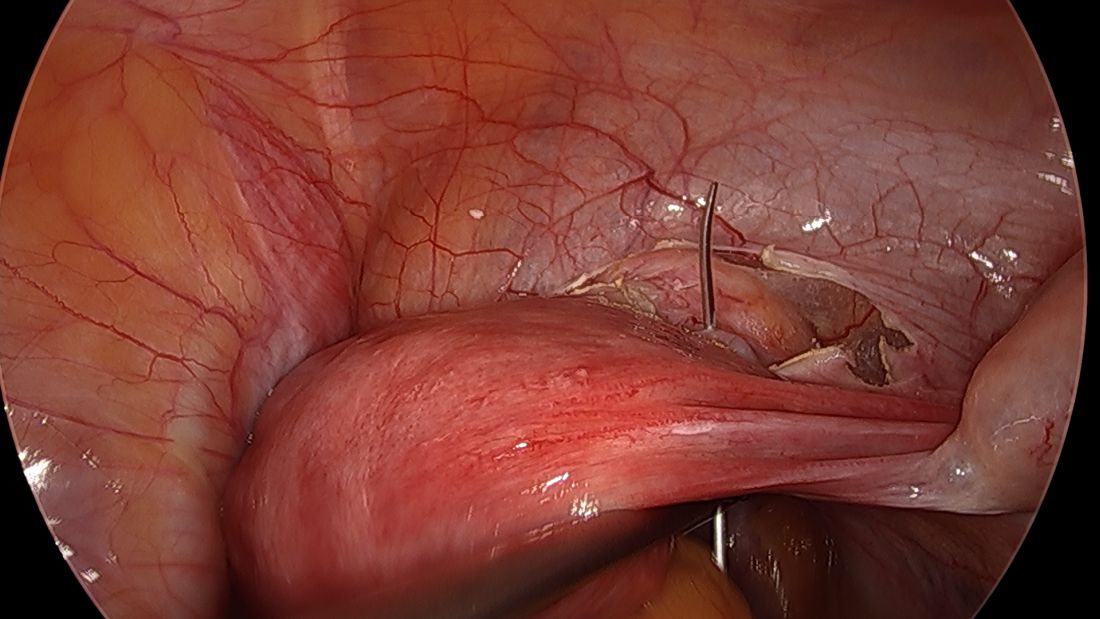

For suturing, we use 5-mm Mersilene polyester tape with blunt-tip needles – the same tape that is commonly used for vaginal cerclages. The needles (which probably are unnecessarily long for laparoscopic cerclages) are straightened out prior to insertion with robust needle holders.

The posterior broad ligament is not opened prior to insertion of the needle, as opening the broad ligament risks possible vessel injury and adds complexity.

Direct insertion of the needle simplifies the procedure and has not led to any complications thus far.

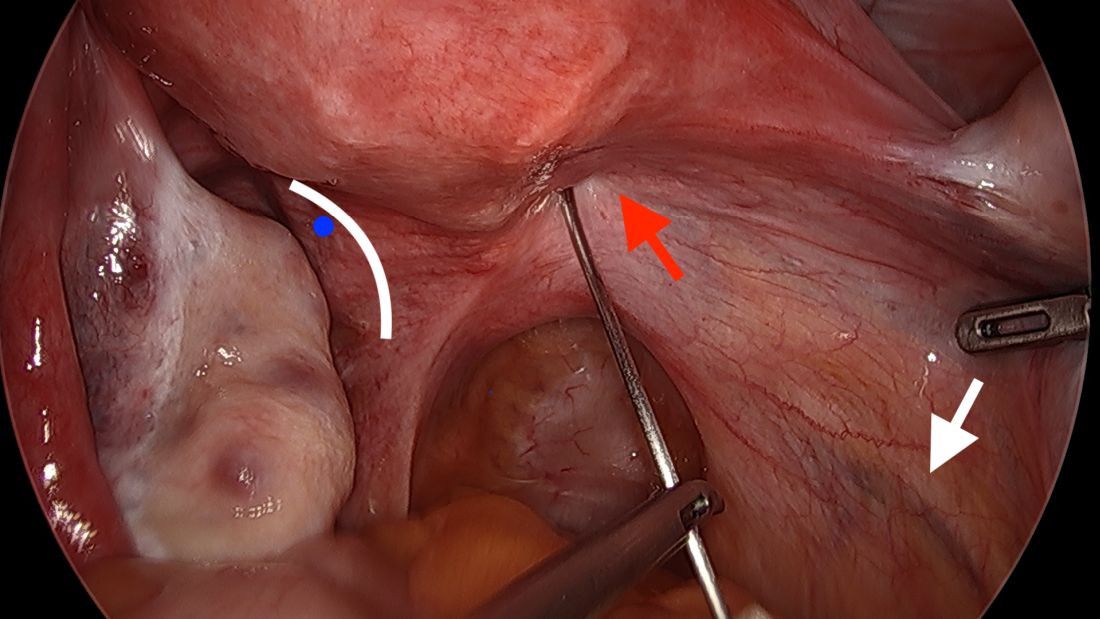

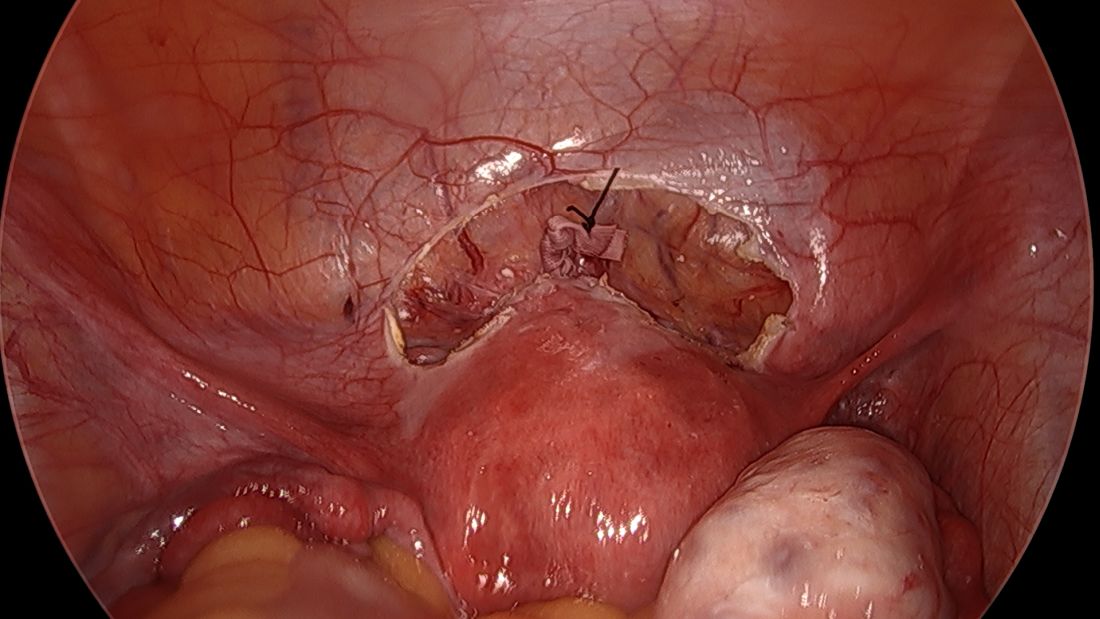

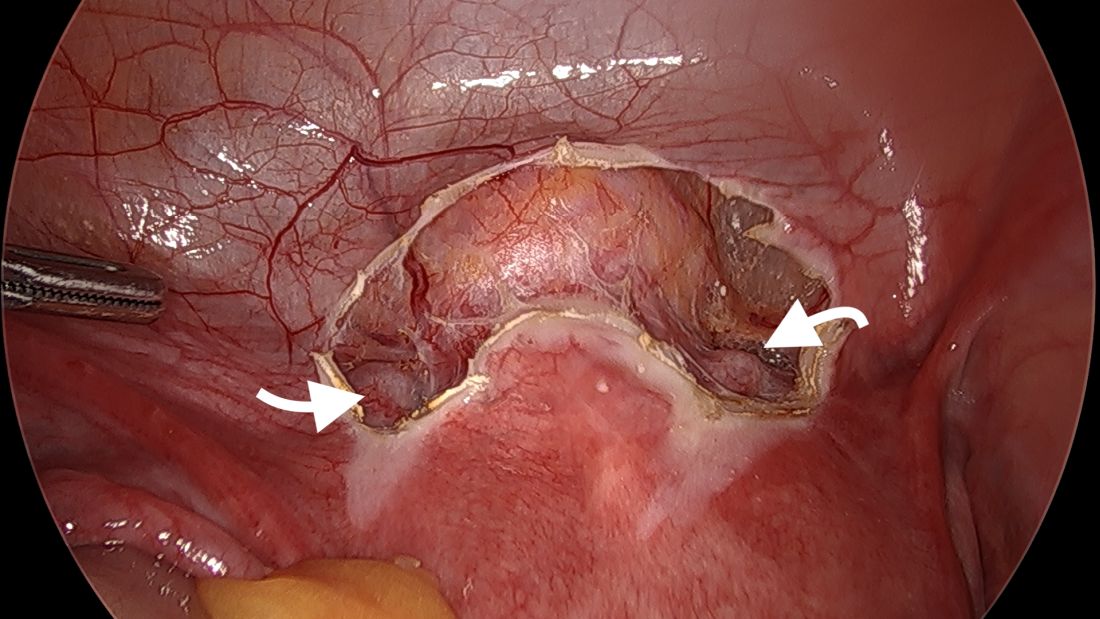

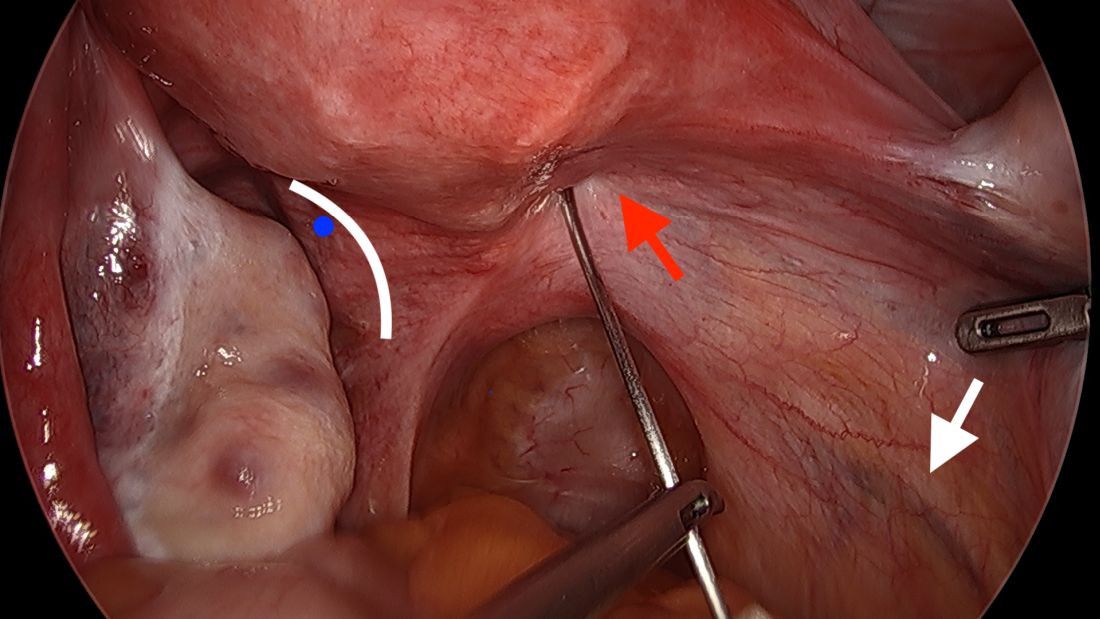

We prefer to insert the suture posteriorly at the level of the internal os just above the insertion of the uterosacral ligaments. It is helpful to view the uterus and cervix as an hourglass, with the level of the internal os is at the narrowest point of the hourglass.

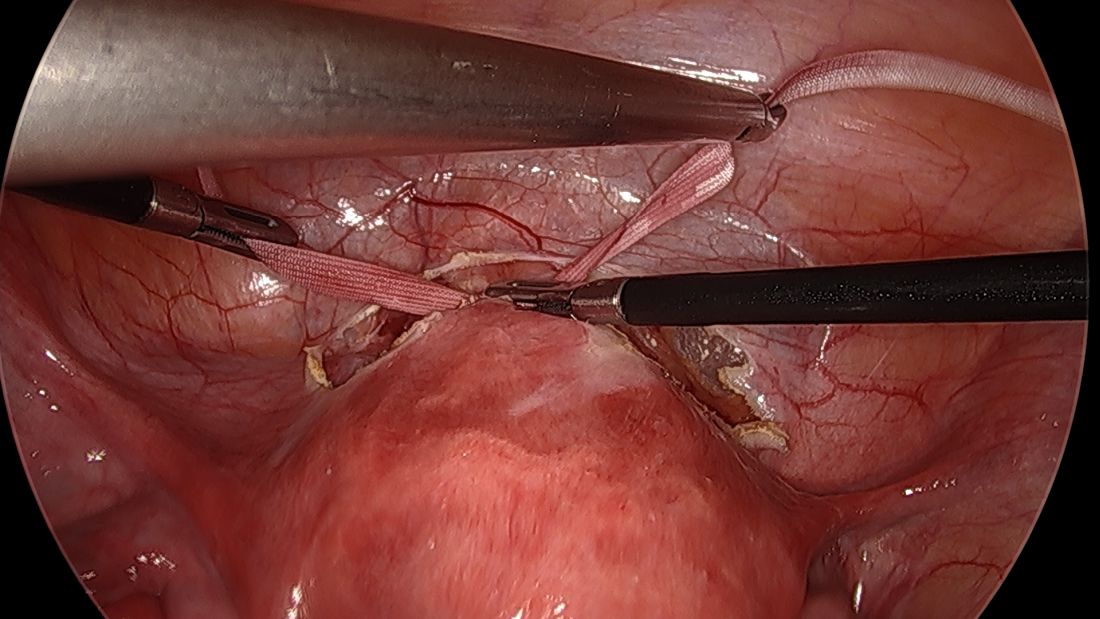

The suture is passed carefully between the uterine vessels and the cervical stroma. The uterine artery should be lateral to placement of the needle, and the uterosacral ligament should be below. The surgeon should see a pulsation of the uterine artery. The use of blunt needles is advantageous because, especially when newer to the procedure, the surgeon can place the needle in slightly more medial than may be deemed necessary so as to avert the uterine vessels, then adjust placement slightly more laterally if resistance is met.

Suture placement should follow a fairly low-impact path. Encountering too much resistance with the needle signals passage into the cervix and necessitates redirection of the needle with a slightly more lateral placement. Twisting the uterus with the uterine manipulator can be helpful throughout this process.

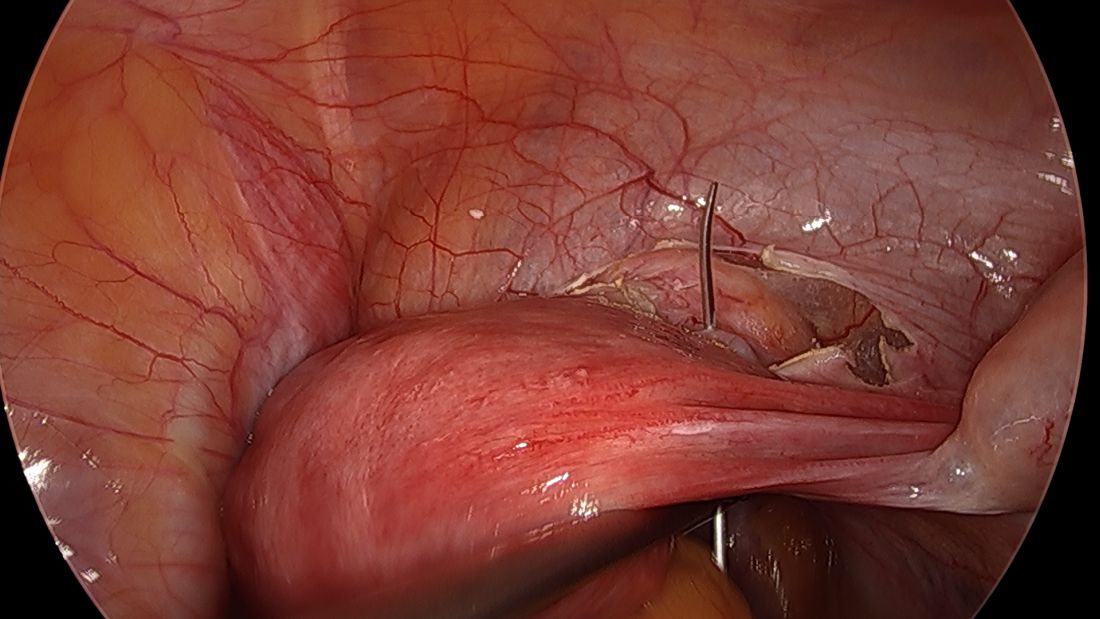

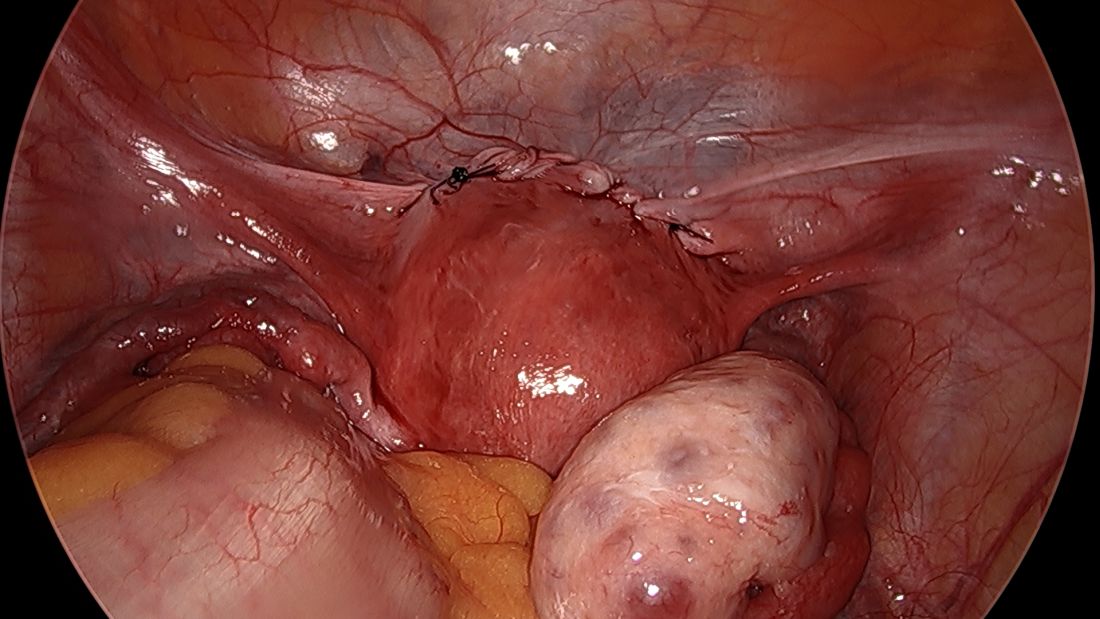

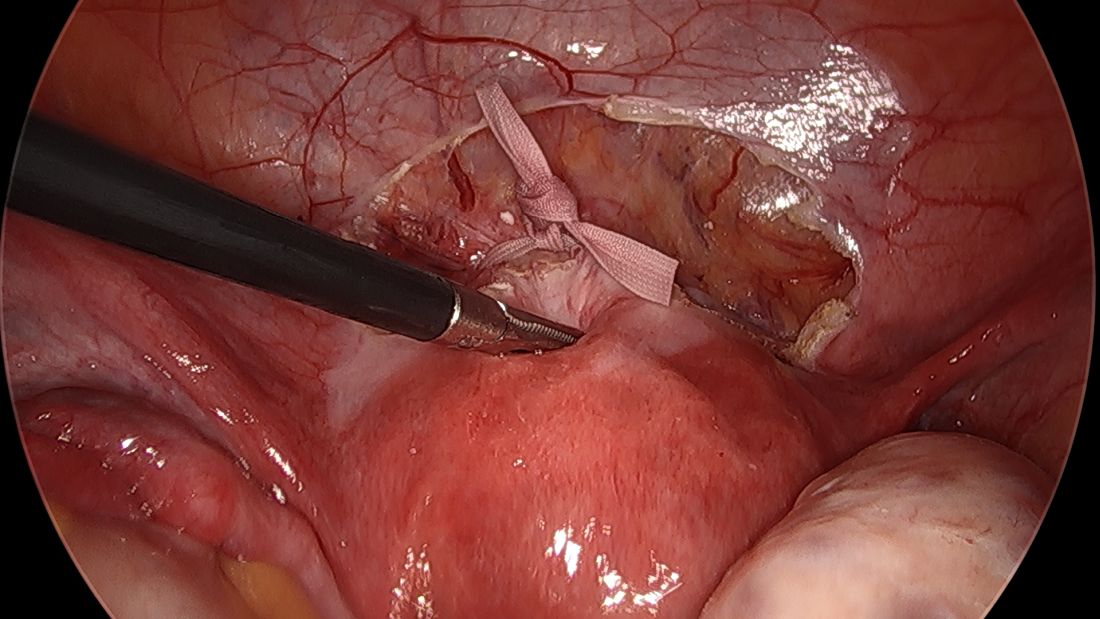

Once the needles are passed through, they are cut off the Mersilene tape and removed. For suturing, it’s important that the first and second knots are tied down snuggly and flat.

I usually ask my assistant to hold down the first knot so that it doesn’t unravel while I tie the second knot. I usually tie 6 square knots with the tape.

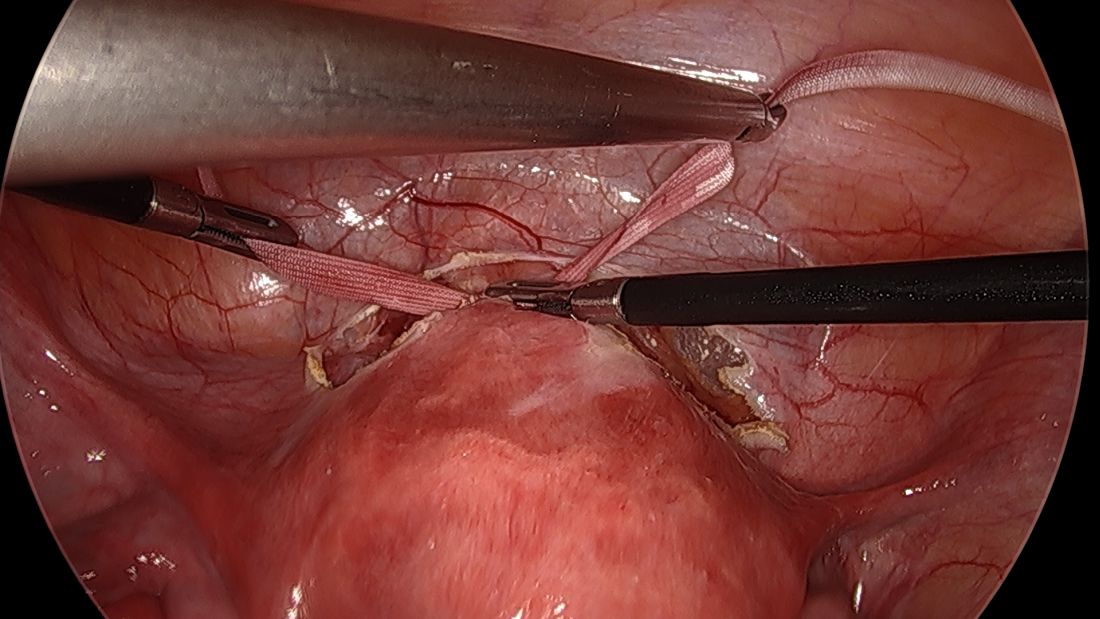

The edges of the tape are then trimmed, and with a 2.0 silk suture, the ends are secured to the lower uterine segment to prevent a theoretical risk of erosion into the bladder.

We then close the overlying vesicouterine peritoneum with 2-0 Monocryl suture, tying it intracorporally. Closing the peritoneum posteriorly is generally not necessary.

We have not had significant bleeding or severe complications in any of our cases. And while the literature comparing preconception and postconception abdominal cerclage is limited, the risks appear very low especially before pregnancy. Some oozing from the uterine vein can sometimes occur; if this does not resolve once it is tied down, placement of a simple figure of eight suture such as a Monocryl or Vicryl at the posterior insertion of the tape may be necessary to stop the bleeding.

Some surgeons place the abdominal cerclage lateral to the uterine artery, presumably to lessen any risk of vessel injury, but again, our placement medial to the vessels has not led to any significant bleeding. By doing so we are averting a theoretical risk with lateral placement of possibly constricting blood flow to the uterus during pregnancy.

Another technique for suturing that has been described uses a fascial closing device, which, after the needles are removed, passes between the vessels and cervix anteriorly and grasps each end of the suture posteriorly before pulling it through the cervix. My concern with this approach is that entry into the cervix with this device’s sharp needles could cause erosion of the tape into the cervical canal. Piercing of a vessel could also cause bleeding.

Laparoscopic abdominal cerclage can also be placed with robotic assistance, but I don’t believe that the robot offers any benefit for this relatively short, uncomplicated procedure.

A note on patient care

We recommend that patients not become pregnant for 2 months after the laparoscopic abdominal cerclage is placed, and that they receive obstetrical care as high-risk patients. The cerclage can be removed at the time of cesarean delivery if the patient has completed childbearing. Otherwise, if the cerclage appears normal, it can be left in place for future pregnancies.

In the event of a miscarriage, a dilatation and evacuation procedure can be performed with an abdominal cerclage in place, up to 18 weeks of pregnancy. Beyond this point, the patient likely will need to have the cerclage removed laparoscopically to allow vaginal passing of the fetus.

References

1. Shennan A et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(3):261.E1-261.E9.

2. Clark NV & Einarsson JI. Fertil Steril. 2020;113:717-22.

3. Benson RC & Durfee RB. Obstet Gynecol. 1965;25:145-55.

4. Lesser KB et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:855-6.

5. Moawad GN et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:277-86.

Cervical insufficiency is an important cause of preterm birth and complicates up to 1% of pregnancies. It is typically diagnosed as painless cervical dilation without contractions, often in the second trimester at around 16-18 weeks, but the clinical presentation can be variable. In some cases, a rescue cerclage can be placed to prevent second trimester loss or preterm birth.

A recent landmark randomized controlled trial of abdominal vs. vaginal cerclage – the MAVRIC trial (Multicentre Abdominal vs. Vaginal Randomized Intervention of Cerclage)1 published in 2020 – has offered significant validation for the belief that an abdominal approach is the preferred approach for patients with cervical insufficiency and a prior failed vaginal cerclage.

Obstetricians traditionally have had a high threshold for placement of an abdominal cerclage given the need for cesarean delivery and the morbidity of an open procedure. Laparoscopic abdominal cerclage has lowered this threshold and is increasingly the preferred method for cerclage placement. Reported complication rates are generally lower than for open abdominal cerclage, and neonatal survival rates are similar or improved.

In our experience, the move toward laparoscopic abdominal cerclage is largely a patient-driven shift. Since 2007, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, we have performed over 150 laparoscopic abdominal cerclage placements. The majority of patients had at least one prior second-trimester loss (many of them had multiple losses), with many having also failed a transvaginal cerclage.

In an analysis of 137 of these cases published recently in Fertility and Sterility, the neonatal survival rate was 93.8% in the 80 pregnancies that followed and extended beyond the first trimester, and the mean gestational age at delivery was 36.9 weeks.2 (First trimester losses are typically excluded from the denominator because they are unlikely to be the result of cervical insufficiency.)

History and outcomes data

The vaginal cerclage has long been a mainstay of therapy because it is a simple procedure. The McDonald technique, described in the 1950s, uses a simple purse string suture at the cervico-vaginal juncture, and the Shirodkar approach, also described in the 1950s, involves placing the cerclage higher on the cervix, as close to the internal os as possible. The Shirodkar technique is more complex, requiring more dissection, and is used less often than the McDonald approach.

The abdominal cerclage, first reported in 1965,3 is placed higher on the cervix, right near the juncture of the lower uterine segment and the cervix, and has generally been thought to provide optimal integrity. It is this point of placement – right at the juncture where membranes begin protruding into the cervix as it shortens and softens – that offers the strongest defense against cervical insufficiency.

The laparoscopic abdominal approach has been gaining popularity since it was first reported in 1998.4 Its traditional indication has been after a prior failed vaginal cerclage or when the cervix is too short to place a vaginal cerclage – as a result of a congenital anomaly or cervical conization, for instance.

Some of my patients have had one pregnancy loss in which cervical insufficiency was suspected and have sought laparoscopic abdominal cerclage without attempting a vaginal cerclage. Data to support this scenario are unavailable, but given the psychological trauma of pregnancy loss and the minimally invasive and low-risk nature of laparoscopic abdominal cerclage, I have been inclined to agree to preventive laparoscopic abdominal procedures without a trial of a vaginal cerclage. I believe this is a reasonable option.

The recently published MAVRIC trial included only abdominal cerclages performed using an open approach, but it provides good data for the scenario in which a vaginal cerclage has failed.

The rates of preterm birth at less than 32 weeks were significantly lower with abdominal cerclage than with low vaginal cerclage (McDonald technique) or high vaginal cerclage (Shirodkar technique) (8% vs. 33%, and 8% vs. 38%). No neonatal deaths occurred.

The analysis covered 111 women who conceived and had known pregnancy outcomes, out of 139 who were recruited and randomized. Cerclage placement occurred either between 10 and 16 weeks of gestation for vaginal cerclages and at 14 weeks for abdominal cerclages or before conception for those assigned to receive an abdominal or high vaginal cerclage.

Reviews of the literature done by our group1 and others have found equivalent outcomes between abdominal cerclages placed through laparotomy and through laparoscopy. The largest systematic review analyzed 31 studies involving 1,844 patients and found that neonatal survival rates were significantly greater in the laparoscopic group (97% vs. 90%), as were rates of deliveries after 34 weeks of gestation (83% vs. 76%).5

The better outcomes in the laparoscopic group may at least partly reflect improved laparoscopic surgeon techniques and improvements in neonatal care over time. At the minimum, we can conclude that neonatal outcomes are at least equivalent when an abdominal cerclage is placed through laparotomy or with a minimally invasive approach.

Our technique

Laparoscopic cerclages are much more easily placed – and with less risk of surgical complications or blood loss – in patients who are not pregnant. Postconception cerclage placement also carries a unique, small risk of fetal loss (estimated to occur in 1.2% of laparoscopic cases and 3% of open cases). 1 We therefore prefer to perform the procedure before pregnancy, though we do place abdominal cerclages in early pregnancy as well. (Approximately 10% of the 137 patients in our analysis were pregnant at the time of cerclage placement. 1 )

The procedure, described here for the nonpregnant patient, typically requires 3-4 ports. My preference is to use a 10-mm scope at the umbilicus, two 5-mm ipsilateral ports, and an additional 5-mm port for my assistant. We generally use a uterine manipulator to help with dissection and facilitate the correct angulation of the suture needle.

We start by opening the vesicouterine peritoneum to dissect the uterine arteries anteriorly and to move the bladder slightly caudad. It is not a significant dissection.

For suturing, we use 5-mm Mersilene polyester tape with blunt-tip needles – the same tape that is commonly used for vaginal cerclages. The needles (which probably are unnecessarily long for laparoscopic cerclages) are straightened out prior to insertion with robust needle holders.

The posterior broad ligament is not opened prior to insertion of the needle, as opening the broad ligament risks possible vessel injury and adds complexity.

Direct insertion of the needle simplifies the procedure and has not led to any complications thus far.

We prefer to insert the suture posteriorly at the level of the internal os just above the insertion of the uterosacral ligaments. It is helpful to view the uterus and cervix as an hourglass, with the level of the internal os is at the narrowest point of the hourglass.

The suture is passed carefully between the uterine vessels and the cervical stroma. The uterine artery should be lateral to placement of the needle, and the uterosacral ligament should be below. The surgeon should see a pulsation of the uterine artery. The use of blunt needles is advantageous because, especially when newer to the procedure, the surgeon can place the needle in slightly more medial than may be deemed necessary so as to avert the uterine vessels, then adjust placement slightly more laterally if resistance is met.

Suture placement should follow a fairly low-impact path. Encountering too much resistance with the needle signals passage into the cervix and necessitates redirection of the needle with a slightly more lateral placement. Twisting the uterus with the uterine manipulator can be helpful throughout this process.

Once the needles are passed through, they are cut off the Mersilene tape and removed. For suturing, it’s important that the first and second knots are tied down snuggly and flat.

I usually ask my assistant to hold down the first knot so that it doesn’t unravel while I tie the second knot. I usually tie 6 square knots with the tape.

The edges of the tape are then trimmed, and with a 2.0 silk suture, the ends are secured to the lower uterine segment to prevent a theoretical risk of erosion into the bladder.

We then close the overlying vesicouterine peritoneum with 2-0 Monocryl suture, tying it intracorporally. Closing the peritoneum posteriorly is generally not necessary.

We have not had significant bleeding or severe complications in any of our cases. And while the literature comparing preconception and postconception abdominal cerclage is limited, the risks appear very low especially before pregnancy. Some oozing from the uterine vein can sometimes occur; if this does not resolve once it is tied down, placement of a simple figure of eight suture such as a Monocryl or Vicryl at the posterior insertion of the tape may be necessary to stop the bleeding.

Some surgeons place the abdominal cerclage lateral to the uterine artery, presumably to lessen any risk of vessel injury, but again, our placement medial to the vessels has not led to any significant bleeding. By doing so we are averting a theoretical risk with lateral placement of possibly constricting blood flow to the uterus during pregnancy.

Another technique for suturing that has been described uses a fascial closing device, which, after the needles are removed, passes between the vessels and cervix anteriorly and grasps each end of the suture posteriorly before pulling it through the cervix. My concern with this approach is that entry into the cervix with this device’s sharp needles could cause erosion of the tape into the cervical canal. Piercing of a vessel could also cause bleeding.

Laparoscopic abdominal cerclage can also be placed with robotic assistance, but I don’t believe that the robot offers any benefit for this relatively short, uncomplicated procedure.

A note on patient care

We recommend that patients not become pregnant for 2 months after the laparoscopic abdominal cerclage is placed, and that they receive obstetrical care as high-risk patients. The cerclage can be removed at the time of cesarean delivery if the patient has completed childbearing. Otherwise, if the cerclage appears normal, it can be left in place for future pregnancies.

In the event of a miscarriage, a dilatation and evacuation procedure can be performed with an abdominal cerclage in place, up to 18 weeks of pregnancy. Beyond this point, the patient likely will need to have the cerclage removed laparoscopically to allow vaginal passing of the fetus.

References

1. Shennan A et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(3):261.E1-261.E9.

2. Clark NV & Einarsson JI. Fertil Steril. 2020;113:717-22.

3. Benson RC & Durfee RB. Obstet Gynecol. 1965;25:145-55.

4. Lesser KB et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:855-6.

5. Moawad GN et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:277-86.