User login

Preparing Veterans Health Administration Psychologists to Meet the Complex Needs of Aging Veterans

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is understaffed for clinical psychologists who have specialty training in geriatrics (ie, geropsychologists) to meet the needs of aging veterans. Though only 16.8% of US adults are aged ≥ 65 years,1 this age group comprises 45.9% of patients within the VHA.2 The needs of older adults are complex and warrant specialized services from mental health clinicians trained to understand lifespan developmental processes, biological changes associated with aging, and changes in psychosocial functioning.

Older veterans (aged ≥ 65 years) present with higher rates of combined medical and mental health diagnoses compared to both younger veterans and older adults who are not veterans.3 Nearly 1 of 5 (18.1%) older veterans who use VHA services have confirmed mental health diagnoses, and an additional 25.5% have documented mental health concerns without a formal diagnosis in their health record.4 The clinical presentations of older veterans frequently differ from younger adults and include greater complexity. For example, older veterans face an increased risk of cognitive impairment compared to the general population, due in part to higher prevalence of posttraumatic stress, which doubles their risk of developing dementia.5 Additional examples of multicomplexity among older veterans may include co-occurring medical and psychiatric diagnoses, the presence of delirium, social isolation/loneliness, and concerns related to polypharmacy. These complex presentations result in significant challenges for mental health clinicians in areas like assessment (eg, accuracy of case conceptualization), intervention (eg, selection and prioritization), and consultation (eg, coordination among multiple medical and mental health specialists).

Older veterans also present with substantial resilience. Research has found that aging veterans exposed to trauma during their military service often review their memories and past experiences, which is known as later-adulthood trauma reengagement.6 Through this normative life review process, veterans engage with memories and experiences from their past that they previously avoided, which could lead to posttraumatic growth for some. Unfortunately, others may experience an increase in psychological distress. Mental health clinicians with specialty expertise and training in aging and lifespan development can facilitate positive outcomes to reduce distress.7

The United States in general, and the VHA specifically, face a growing shortage of geriatric mental health clinicians.

The Geriatric Scholars Program (GSP) was developed in 2008 to address the training gap and provide education in geriatrics to VHA clinicians that treat older veterans, particularly in rural areas.11,12 The GSP initially focused on primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists. It was later expanded to include other disciplines (ie, social work, rehabilitation therapists, and psychiatrists). In 2013, the GSP – Psychology Track (GSP-P) was developed with funding from the VHA Offices of Rural Health and Geriatrics and Extended Care specifically for psychologists.

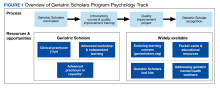

This article describes the multicomponent longitudinal GSP-P, which has evolved to meet the target audience’s ongoing needs for knowledge, skills, and opportunities to refine practice behaviors. GSP-P received the 2020 Award for Excellence in Geropsychology Training from the Council of Professional Geropsychology Training Programs. GSP-P has grown within the context of the larger GSP and aligns with the other existing elective learning opportunities (Figure 1).

Program description

Introductory Course

Psychologist subject matter experts (SMEs) developed an intensive course in geropsychology in the absence of a similar course in the geriatric medicine board review curriculum. SMEs reviewed the guidelines for practice by professional organizations like the Pikes Peak Geropsychology Competencies, which outline knowledge and skills in various domains.13 SMEs integrated this review with findings from a needs assessment for postlicensed VHA psychology staff in 4 health care systems, drafted a syllabus, and circulated it to geropsychology experts for feedback. The resulting multiday course covered general mental health as well as topics particularly salient for mental health clinicians treating older veterans including suicide prevention and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).14 This Geropsychology Competencies Review Course was piloted in 1 region initially before being offered nationally in 2014.

Quality Improvement

Introductory course attendees also participate in an intensive day-long interactive workshop in quality improvement (QI). After completing these trainings, they apply what they have learned at their home facility by embarking on a QI project related to geriatrics. The QI projects reinforce learning and initiate practice changes not only for attendees but at times the larger health care system. Topics are selected by scholars in response to the needs they observe in their clinics. Recent GSP projects include efforts to increase screenings for depression and anxiety, improve adherence to VHA dementia policy, increase access to virtual care, and increase referrals to programs such as whole health or cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, a first-line treatment for insomnia in older adults.17 Another project targeted the improvement of referrals to the Compassionate Contact Corps in an effort to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older veterans.18 Evaluations demonstrate significant improvement in scholars’ confidence in related program development and management from precourse to 3 months postcourse.15

Webinars

The Addressing Geriatric Mental Health webinar series was created to introduce learners to topics that could not be covered in the introductory course. Topics were suggested by the expert reviewers of the curriculum or identified by the scholars themselves (eg, chronic pain, sexuality, or serious mental illness). A secondary function of the webinars was to reach a broader audience. Over time, scholars and webinar attendees requested opportunities to explore topics in greater depth (eg, PTSD later in life). These requests led the webinars to focus on annual themes.

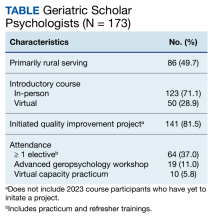

The series is open to all disciplines of geriatric scholars, VHA staff, and non-VHA staff through the Veterans Affairs Talent Management System and the TRAIN Learning Network (train.org). Attendance for the 37 webinars was captured from logins to the virtual learning platform and may underestimate attendance if a group attended on a single screen. Average attendance increased from 157 attendees/webinar in 2015 to 418 attendees/webinar in 2023 (Figure 2). This may have been related to the increase in virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, but represents a 166% increase in audience from the inaugural year of the series.

Advanced Learning Opportunities

To invest in the ongoing growth and development of introductory course graduates, GSP-P developed and offered an advanced workshop in 2019. This multiday workshop focused on further enhancement of geropsychology competencies, with an emphasis on treating older veterans with mental and physical comorbidities. Didactics and experiential learning exercises led by SMEs covered topics such as adjusting to chronic illness, capacity assessment, PTSD, insomnia and sleep changes, chronic pain, and psychological interventions in palliative care and hospice settings. Evaluation findings demonstrated significant improvements from precourse to 6 months postcourse in confidence and knowledge as

To facilitate ongoing and individually tailored learning following the advanced workshop, scholars also developed and executed independent learning plans (ILPs) during a 6-month window with consultation from an experienced geropsychologist. Fifteen of 19 scholars (78.9%) completed ILPs with an average of 3 learning goals listed. After completing the ILPs, scholars endorsed their clinical and/or personal usefulness, citing increased confidence, enhanced skills for use with patients with complex needs, personal fulfillment, and career advancement. Most scholars noted ILPs were feasible and learning resources were accessible. Overall, the evaluation found ILPs to be a valuable way to enhance psychologists’ learning and effectiveness in treating older veterans with complex health needs.20

Clinical Practica

All geriatric scholars who completed the program have additional opportunities for professional development through practicum experiences focused on specific clinical approaches to the care of older veterans, such as dementia care, pain management, geriatric assessment, and palliative care. These practica provide scholars with individualized learning experiences in an individualized or small group setting and may be conducted either in-person or virtually.

In response to an expressed need from those who completed the program, the GSP-P planning committee collaborated with an SME to develop a virtual practicum to assess patients’ decision making capacity. Evaluating capacities among older adults is a common request, yet clinicians report little to no formal training in how to conceptualize and approach these complex questions.21,22 Utilizing an evidence-informed and structured approach promotes the balancing of an older adult’s autonomy and professional ethics. Learning capacity evaluation skills could better position psychologists to not only navigate complex ethical, legal, and clinical situations, but also serve as expert consultants to interdisciplinary teams. This virtual practicum was initiated in 2022 and to date has included 10 scholars. The practicum includes multiple modalities of learning: (1) self-directed review of core concepts; (2) attendance at 4 capacity didactics focused on introduction to evaluating capacities, medical consent and decision making, financial decision making and management, and independent living; and (3) participation in 5 group consultations on capacity evaluations conducted at their home sites. During these group consultations, additional case examples were shared to reinforce capacity concepts.

Discussion

The objective of GSP-P is to enhance geropsychology practice competencies among VHA psychologists given the outsized representation of older adults within the VHA system and their complex care needs. The curricula have significantly evolved to accomplish this, expanding the reach and investing in the continuing growth and development of scholars.

There are several elements that set GSP apart from other geriatric and geropsychology continuing medical education programs. The first is that the training is veteran focused, allowing us to discuss the unique impact military service has on aging. Similarly, because all scholars work within the integrated health care system, we can introduce and review key resources and programs that benefit all veterans and their families/care partners across the system. Through the GSP, the VA invests in ongoing professional development. Scholars can participate in additional experiential practica, webinars, and advanced workshops tailored to their individual learning needs. Lastly, the GSP works to create a community among its scholars where they can not only continue to consult with presenters/instructors, but also one another. A planned future direction for the GSP-P is to incorporate quarterly office hours and discussions for alumni to develop an increased sense of community. This may strengthen commitment to the overall VA mission, leading to increased retainment of talent who now have the knowledge, skills, and confidence to care for aging veterans.

Limitations

GSP is limited by its available funding. Additionally, the number of participants who can enroll each year in GSP-P (not including webinars) is capped by policy. Another limitation is the number of QI coaches available to mentor scholars on their projects.

Conclusions

Outcomes of GSP-P have been extremely favorable. Following participation in the program, we have found a significant increase in confidence in geropsychology practice among clinicians, as well as enhanced knowledge and skills across competency domains.15,19 We have observed rising attendance in our annual webinar series and graduates of our introductory courses participate in subsequent trainings (eg, advanced workshop or virtual practicum). Several graduates of GSP-P have become board certified in geropsychology by the American Board of Geropsychology and many proceed to supervise geropsychology-focused clinical rotations for psychology practicum students, predoctoral interns, and postdoctoral fellows. This suggests that the reach of GSP-P programming may extend farther than reported in this article.

The needs of aging veterans have also changed based on cohort differences, as the population of World War II and Korean War era veterans has declined and the number of older Vietnam era veterans has grown. We expect different challenges with older Gulf War and post-9/11 era veterans. For instance, 17% of troops deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan following 9/11 experienced mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), and 59% of those experienced > 1 mild TBI.23 Research indicates that younger post-9/11 veterans have a 3-fold risk of developing early onset dementia after experiencing a TBI.24 Therefore, even though post-9/11 veterans are not older in terms of chronological age, some may experience symptoms and conditions more often occurring in older veterans. As a result, it would be beneficial for clinicians to learn about the presentation and treatment of geriatric conditions such as dementia.

Moving forward, the GSP-P should identify potential opportunities to collaborate with the non-VHA mental health community–which also faces a shortage of geriatric mental health clinicians–to extend educational opportunities to improve care for veterans in all settings (eg, cosponsor training opportunities open to both VHA and non-VHA clinicians).8,25 Many aging veterans may receive portions of their health care outside the VHA, particularly those who reside in rural areas. Additionally, as veterans age, so do their support systems (eg, family members, friends, spouses, caregivers, and even clinicians), most of whom will receive care outside of the VHA. Community education collaborations will not only improve the care of older veterans, but also the care of older adults in the general population.

Promising directions include the adoption of the GSP model in other health care settings. Recently, Indian Health Service has adapted the model, beginning with primary care clinicians and pharmacists and is beginning to expand to other disciplines. Additional investments in VHA workforce training include the availability of geropsychology internship and fellowship training opportunities through the Office of Academic Affiliations, which provide earlier opportunities to specialize in geropsychology. Continued investment in both prelicensure and postpsychology licensure training efforts are needed within the VHA to meet the geriatric mental health needs of veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Terri Huh, PhD, for her contributions to the development and initiation of the GSP-P. The authors also appreciate the collaboration and quality initiative training led by Carol Callaway-Lane, DNP, ACNP-BC, and her team.

1. Caplan Z, Rabe M; US Department of Commerce, US Census Bureau. The Older Population: 2020 (Census Brief No. C2020BR-07). May 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/2020/census-briefs/c2020br-07.pdf

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. VA benefits & health care utilization. Updated February 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/pocketcards/fy2023q2.PDF

3. O’Malley KA, Vinson L, Pless Kaiser A, Sager Z, Hinrichs K. Mental health and aging veterans: How the Veterans Health Administration meets the needs of aging veterans. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2020;30(1):19-23. doi:10.1093/ppar/prz027

4. Greenberg G, Hoff R. FY 2021 Older Adult (65+ on October 1st) Veteran Data Sheet: National, VISN, and Healthcare System Tables. West Haven, CT: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Northeast Program Evaluation Center. 2022.

5. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.61

6. Davison EH, Kaiser AP, Spiro A 3rd, Moye J, King LA, King DW. From late-onset stress symptomatology to later-adulthood trauma reengagement in aging combat veterans: Taking a broader view. Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):14-21. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv097

7. Kaiser AP, Boyle JT, Bamonti PM, O’Malley K, Moye J. Development, adaptation, and clinical implementation of the Later-Adulthood Trauma Reengagement (LATR) group intervention for older veterans. Psychol Serv. 2023;20(4):863-875. doi:10.1037/ser0000736

8. Moye J, Karel MJ, Stamm KE, et al. Workforce analysis of psychological practice with older adults: Growing crisis requires urgent action. Train Educ Prof Psychol. 2019;13(1):46-55. doi:10.1037/tep0000206

9. Stamm K, Lin L, Conroy J. Critical needs in geropsychology. Monitor on Psychology. 2021;52(4):21.

10. American Board of Geropsychology. Specialists. 2024. Accessed February 6, 2024. https://abgero.org/board-members/specialists/

11. Kramer BJ. The VA Geriatric Scholars Program. Fed Pract. 2015;32(5):46-48.

12. Kramer BJ, Creekmur B, Howe JL, et al. Veterans Affairs Geriatric Scholars Program: Enhancing existing primary care clinician skills in caring for older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):2343-2348. doi:10.1111/jgs.14382

13. Knight BG, Karel MJ, Hinrichsen GA, Qualls SH, Duffy M. Pikes Peak model for training in professional geropsychology. Am Psychol. 2009;64(3):205-14. doi:10.1037/a0015059

14. Huh JWT, Rodriguez R, Gould CE, R Brunskill S, Melendez L, Kramer BJ. Developing a program to increase geropsychology competencies of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) psychologists. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2020;41(4):463-479. doi:10.1080/02701960.2018.1491402

15. Huh JWT, Rodriguez RL, Gregg JJ, Scales AN, Kramer BJ, Gould CE. Improving geropsychology competencies of Veterans Affairs psychologists. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(3):798-805. doi:10.1111/jgs.17029

16. Karel MJ, Emery EE, Molinari V; CoPGTP Task Force on the Assessment of Geropsychology Competencies. Development of a tool to evaluate geropsychology knowledge and skill competencies. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(6):886-896. doi:10.1017/S1041610209991736

17. Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, et al. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2006;29(11):1415-1419.

18. Sullivan J, Gualtieri L, Campbell M, Davila H, Pendergast J, Taylor P. VA Compassionate Contact Corps: a phone-based intervention for veterans interested in speaking with peers. Innov Aging. 2021;5(Suppl 1):204. doi:10.1093/geroni/igab046.788

19. Gregg JJ, Rodriguez RL, Mehta PS, Kramer BJ, Gould CE. Enhancing specialty training in geropsychology competencies: an evaluation of a VA Geriatric Scholars Program advanced topics workshop. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2023;44(3):329-338. doi:10.1080/02701960.2022.2069764

20. Gould CE, Rodriguez RL, Gregg J, Mehta PS, Kramer J. Mentored independent learning plans among psychologists: a mixed methods investigation. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(S1):S53.

21. Mullaly E, Kinsella G, Berberovic N, et al. Assessment of decision-making capacity: exploration of common practices among neuropsychologists. Aust Psychol. 2007;42:178-186. doi:10.1080/00050060601187142

22. Seyfried L, Ryan KA, Kim SYH. Assessment of decision-making capacity: Views and experiences of consultation psychiatrists. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(2):115-123. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2012.08.001

23. Wilk JE, Herrell RK, Wynn GH, Riviere LA, Hoge CW. Mild traumatic brain injury (concussion), posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in U.S. soldiers involved in combat deployments: association with postdeployment symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(3):249-257. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e318244c604

24. Kennedy E, Panahi S, Stewart IJ, et al. Traumatic brain injury and early onset dementia in post 9-11 veterans. Brain Inj. 2022;36(5):620-627.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033846

25. Merz CC, Koh D, Sakai EY, et al. The big shortage: Geropsychologists discuss facilitators and barriers to working in the field of aging. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 2017;3(4):388-399. doi:10.1037/tps0000137

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is understaffed for clinical psychologists who have specialty training in geriatrics (ie, geropsychologists) to meet the needs of aging veterans. Though only 16.8% of US adults are aged ≥ 65 years,1 this age group comprises 45.9% of patients within the VHA.2 The needs of older adults are complex and warrant specialized services from mental health clinicians trained to understand lifespan developmental processes, biological changes associated with aging, and changes in psychosocial functioning.

Older veterans (aged ≥ 65 years) present with higher rates of combined medical and mental health diagnoses compared to both younger veterans and older adults who are not veterans.3 Nearly 1 of 5 (18.1%) older veterans who use VHA services have confirmed mental health diagnoses, and an additional 25.5% have documented mental health concerns without a formal diagnosis in their health record.4 The clinical presentations of older veterans frequently differ from younger adults and include greater complexity. For example, older veterans face an increased risk of cognitive impairment compared to the general population, due in part to higher prevalence of posttraumatic stress, which doubles their risk of developing dementia.5 Additional examples of multicomplexity among older veterans may include co-occurring medical and psychiatric diagnoses, the presence of delirium, social isolation/loneliness, and concerns related to polypharmacy. These complex presentations result in significant challenges for mental health clinicians in areas like assessment (eg, accuracy of case conceptualization), intervention (eg, selection and prioritization), and consultation (eg, coordination among multiple medical and mental health specialists).

Older veterans also present with substantial resilience. Research has found that aging veterans exposed to trauma during their military service often review their memories and past experiences, which is known as later-adulthood trauma reengagement.6 Through this normative life review process, veterans engage with memories and experiences from their past that they previously avoided, which could lead to posttraumatic growth for some. Unfortunately, others may experience an increase in psychological distress. Mental health clinicians with specialty expertise and training in aging and lifespan development can facilitate positive outcomes to reduce distress.7

The United States in general, and the VHA specifically, face a growing shortage of geriatric mental health clinicians.

The Geriatric Scholars Program (GSP) was developed in 2008 to address the training gap and provide education in geriatrics to VHA clinicians that treat older veterans, particularly in rural areas.11,12 The GSP initially focused on primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists. It was later expanded to include other disciplines (ie, social work, rehabilitation therapists, and psychiatrists). In 2013, the GSP – Psychology Track (GSP-P) was developed with funding from the VHA Offices of Rural Health and Geriatrics and Extended Care specifically for psychologists.

This article describes the multicomponent longitudinal GSP-P, which has evolved to meet the target audience’s ongoing needs for knowledge, skills, and opportunities to refine practice behaviors. GSP-P received the 2020 Award for Excellence in Geropsychology Training from the Council of Professional Geropsychology Training Programs. GSP-P has grown within the context of the larger GSP and aligns with the other existing elective learning opportunities (Figure 1).

Program description

Introductory Course

Psychologist subject matter experts (SMEs) developed an intensive course in geropsychology in the absence of a similar course in the geriatric medicine board review curriculum. SMEs reviewed the guidelines for practice by professional organizations like the Pikes Peak Geropsychology Competencies, which outline knowledge and skills in various domains.13 SMEs integrated this review with findings from a needs assessment for postlicensed VHA psychology staff in 4 health care systems, drafted a syllabus, and circulated it to geropsychology experts for feedback. The resulting multiday course covered general mental health as well as topics particularly salient for mental health clinicians treating older veterans including suicide prevention and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).14 This Geropsychology Competencies Review Course was piloted in 1 region initially before being offered nationally in 2014.

Quality Improvement

Introductory course attendees also participate in an intensive day-long interactive workshop in quality improvement (QI). After completing these trainings, they apply what they have learned at their home facility by embarking on a QI project related to geriatrics. The QI projects reinforce learning and initiate practice changes not only for attendees but at times the larger health care system. Topics are selected by scholars in response to the needs they observe in their clinics. Recent GSP projects include efforts to increase screenings for depression and anxiety, improve adherence to VHA dementia policy, increase access to virtual care, and increase referrals to programs such as whole health or cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, a first-line treatment for insomnia in older adults.17 Another project targeted the improvement of referrals to the Compassionate Contact Corps in an effort to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older veterans.18 Evaluations demonstrate significant improvement in scholars’ confidence in related program development and management from precourse to 3 months postcourse.15

Webinars

The Addressing Geriatric Mental Health webinar series was created to introduce learners to topics that could not be covered in the introductory course. Topics were suggested by the expert reviewers of the curriculum or identified by the scholars themselves (eg, chronic pain, sexuality, or serious mental illness). A secondary function of the webinars was to reach a broader audience. Over time, scholars and webinar attendees requested opportunities to explore topics in greater depth (eg, PTSD later in life). These requests led the webinars to focus on annual themes.

The series is open to all disciplines of geriatric scholars, VHA staff, and non-VHA staff through the Veterans Affairs Talent Management System and the TRAIN Learning Network (train.org). Attendance for the 37 webinars was captured from logins to the virtual learning platform and may underestimate attendance if a group attended on a single screen. Average attendance increased from 157 attendees/webinar in 2015 to 418 attendees/webinar in 2023 (Figure 2). This may have been related to the increase in virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, but represents a 166% increase in audience from the inaugural year of the series.

Advanced Learning Opportunities

To invest in the ongoing growth and development of introductory course graduates, GSP-P developed and offered an advanced workshop in 2019. This multiday workshop focused on further enhancement of geropsychology competencies, with an emphasis on treating older veterans with mental and physical comorbidities. Didactics and experiential learning exercises led by SMEs covered topics such as adjusting to chronic illness, capacity assessment, PTSD, insomnia and sleep changes, chronic pain, and psychological interventions in palliative care and hospice settings. Evaluation findings demonstrated significant improvements from precourse to 6 months postcourse in confidence and knowledge as

To facilitate ongoing and individually tailored learning following the advanced workshop, scholars also developed and executed independent learning plans (ILPs) during a 6-month window with consultation from an experienced geropsychologist. Fifteen of 19 scholars (78.9%) completed ILPs with an average of 3 learning goals listed. After completing the ILPs, scholars endorsed their clinical and/or personal usefulness, citing increased confidence, enhanced skills for use with patients with complex needs, personal fulfillment, and career advancement. Most scholars noted ILPs were feasible and learning resources were accessible. Overall, the evaluation found ILPs to be a valuable way to enhance psychologists’ learning and effectiveness in treating older veterans with complex health needs.20

Clinical Practica

All geriatric scholars who completed the program have additional opportunities for professional development through practicum experiences focused on specific clinical approaches to the care of older veterans, such as dementia care, pain management, geriatric assessment, and palliative care. These practica provide scholars with individualized learning experiences in an individualized or small group setting and may be conducted either in-person or virtually.

In response to an expressed need from those who completed the program, the GSP-P planning committee collaborated with an SME to develop a virtual practicum to assess patients’ decision making capacity. Evaluating capacities among older adults is a common request, yet clinicians report little to no formal training in how to conceptualize and approach these complex questions.21,22 Utilizing an evidence-informed and structured approach promotes the balancing of an older adult’s autonomy and professional ethics. Learning capacity evaluation skills could better position psychologists to not only navigate complex ethical, legal, and clinical situations, but also serve as expert consultants to interdisciplinary teams. This virtual practicum was initiated in 2022 and to date has included 10 scholars. The practicum includes multiple modalities of learning: (1) self-directed review of core concepts; (2) attendance at 4 capacity didactics focused on introduction to evaluating capacities, medical consent and decision making, financial decision making and management, and independent living; and (3) participation in 5 group consultations on capacity evaluations conducted at their home sites. During these group consultations, additional case examples were shared to reinforce capacity concepts.

Discussion

The objective of GSP-P is to enhance geropsychology practice competencies among VHA psychologists given the outsized representation of older adults within the VHA system and their complex care needs. The curricula have significantly evolved to accomplish this, expanding the reach and investing in the continuing growth and development of scholars.

There are several elements that set GSP apart from other geriatric and geropsychology continuing medical education programs. The first is that the training is veteran focused, allowing us to discuss the unique impact military service has on aging. Similarly, because all scholars work within the integrated health care system, we can introduce and review key resources and programs that benefit all veterans and their families/care partners across the system. Through the GSP, the VA invests in ongoing professional development. Scholars can participate in additional experiential practica, webinars, and advanced workshops tailored to their individual learning needs. Lastly, the GSP works to create a community among its scholars where they can not only continue to consult with presenters/instructors, but also one another. A planned future direction for the GSP-P is to incorporate quarterly office hours and discussions for alumni to develop an increased sense of community. This may strengthen commitment to the overall VA mission, leading to increased retainment of talent who now have the knowledge, skills, and confidence to care for aging veterans.

Limitations

GSP is limited by its available funding. Additionally, the number of participants who can enroll each year in GSP-P (not including webinars) is capped by policy. Another limitation is the number of QI coaches available to mentor scholars on their projects.

Conclusions

Outcomes of GSP-P have been extremely favorable. Following participation in the program, we have found a significant increase in confidence in geropsychology practice among clinicians, as well as enhanced knowledge and skills across competency domains.15,19 We have observed rising attendance in our annual webinar series and graduates of our introductory courses participate in subsequent trainings (eg, advanced workshop or virtual practicum). Several graduates of GSP-P have become board certified in geropsychology by the American Board of Geropsychology and many proceed to supervise geropsychology-focused clinical rotations for psychology practicum students, predoctoral interns, and postdoctoral fellows. This suggests that the reach of GSP-P programming may extend farther than reported in this article.

The needs of aging veterans have also changed based on cohort differences, as the population of World War II and Korean War era veterans has declined and the number of older Vietnam era veterans has grown. We expect different challenges with older Gulf War and post-9/11 era veterans. For instance, 17% of troops deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan following 9/11 experienced mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), and 59% of those experienced > 1 mild TBI.23 Research indicates that younger post-9/11 veterans have a 3-fold risk of developing early onset dementia after experiencing a TBI.24 Therefore, even though post-9/11 veterans are not older in terms of chronological age, some may experience symptoms and conditions more often occurring in older veterans. As a result, it would be beneficial for clinicians to learn about the presentation and treatment of geriatric conditions such as dementia.

Moving forward, the GSP-P should identify potential opportunities to collaborate with the non-VHA mental health community–which also faces a shortage of geriatric mental health clinicians–to extend educational opportunities to improve care for veterans in all settings (eg, cosponsor training opportunities open to both VHA and non-VHA clinicians).8,25 Many aging veterans may receive portions of their health care outside the VHA, particularly those who reside in rural areas. Additionally, as veterans age, so do their support systems (eg, family members, friends, spouses, caregivers, and even clinicians), most of whom will receive care outside of the VHA. Community education collaborations will not only improve the care of older veterans, but also the care of older adults in the general population.

Promising directions include the adoption of the GSP model in other health care settings. Recently, Indian Health Service has adapted the model, beginning with primary care clinicians and pharmacists and is beginning to expand to other disciplines. Additional investments in VHA workforce training include the availability of geropsychology internship and fellowship training opportunities through the Office of Academic Affiliations, which provide earlier opportunities to specialize in geropsychology. Continued investment in both prelicensure and postpsychology licensure training efforts are needed within the VHA to meet the geriatric mental health needs of veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Terri Huh, PhD, for her contributions to the development and initiation of the GSP-P. The authors also appreciate the collaboration and quality initiative training led by Carol Callaway-Lane, DNP, ACNP-BC, and her team.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is understaffed for clinical psychologists who have specialty training in geriatrics (ie, geropsychologists) to meet the needs of aging veterans. Though only 16.8% of US adults are aged ≥ 65 years,1 this age group comprises 45.9% of patients within the VHA.2 The needs of older adults are complex and warrant specialized services from mental health clinicians trained to understand lifespan developmental processes, biological changes associated with aging, and changes in psychosocial functioning.

Older veterans (aged ≥ 65 years) present with higher rates of combined medical and mental health diagnoses compared to both younger veterans and older adults who are not veterans.3 Nearly 1 of 5 (18.1%) older veterans who use VHA services have confirmed mental health diagnoses, and an additional 25.5% have documented mental health concerns without a formal diagnosis in their health record.4 The clinical presentations of older veterans frequently differ from younger adults and include greater complexity. For example, older veterans face an increased risk of cognitive impairment compared to the general population, due in part to higher prevalence of posttraumatic stress, which doubles their risk of developing dementia.5 Additional examples of multicomplexity among older veterans may include co-occurring medical and psychiatric diagnoses, the presence of delirium, social isolation/loneliness, and concerns related to polypharmacy. These complex presentations result in significant challenges for mental health clinicians in areas like assessment (eg, accuracy of case conceptualization), intervention (eg, selection and prioritization), and consultation (eg, coordination among multiple medical and mental health specialists).

Older veterans also present with substantial resilience. Research has found that aging veterans exposed to trauma during their military service often review their memories and past experiences, which is known as later-adulthood trauma reengagement.6 Through this normative life review process, veterans engage with memories and experiences from their past that they previously avoided, which could lead to posttraumatic growth for some. Unfortunately, others may experience an increase in psychological distress. Mental health clinicians with specialty expertise and training in aging and lifespan development can facilitate positive outcomes to reduce distress.7

The United States in general, and the VHA specifically, face a growing shortage of geriatric mental health clinicians.

The Geriatric Scholars Program (GSP) was developed in 2008 to address the training gap and provide education in geriatrics to VHA clinicians that treat older veterans, particularly in rural areas.11,12 The GSP initially focused on primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists. It was later expanded to include other disciplines (ie, social work, rehabilitation therapists, and psychiatrists). In 2013, the GSP – Psychology Track (GSP-P) was developed with funding from the VHA Offices of Rural Health and Geriatrics and Extended Care specifically for psychologists.

This article describes the multicomponent longitudinal GSP-P, which has evolved to meet the target audience’s ongoing needs for knowledge, skills, and opportunities to refine practice behaviors. GSP-P received the 2020 Award for Excellence in Geropsychology Training from the Council of Professional Geropsychology Training Programs. GSP-P has grown within the context of the larger GSP and aligns with the other existing elective learning opportunities (Figure 1).

Program description

Introductory Course

Psychologist subject matter experts (SMEs) developed an intensive course in geropsychology in the absence of a similar course in the geriatric medicine board review curriculum. SMEs reviewed the guidelines for practice by professional organizations like the Pikes Peak Geropsychology Competencies, which outline knowledge and skills in various domains.13 SMEs integrated this review with findings from a needs assessment for postlicensed VHA psychology staff in 4 health care systems, drafted a syllabus, and circulated it to geropsychology experts for feedback. The resulting multiday course covered general mental health as well as topics particularly salient for mental health clinicians treating older veterans including suicide prevention and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).14 This Geropsychology Competencies Review Course was piloted in 1 region initially before being offered nationally in 2014.

Quality Improvement

Introductory course attendees also participate in an intensive day-long interactive workshop in quality improvement (QI). After completing these trainings, they apply what they have learned at their home facility by embarking on a QI project related to geriatrics. The QI projects reinforce learning and initiate practice changes not only for attendees but at times the larger health care system. Topics are selected by scholars in response to the needs they observe in their clinics. Recent GSP projects include efforts to increase screenings for depression and anxiety, improve adherence to VHA dementia policy, increase access to virtual care, and increase referrals to programs such as whole health or cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, a first-line treatment for insomnia in older adults.17 Another project targeted the improvement of referrals to the Compassionate Contact Corps in an effort to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older veterans.18 Evaluations demonstrate significant improvement in scholars’ confidence in related program development and management from precourse to 3 months postcourse.15

Webinars

The Addressing Geriatric Mental Health webinar series was created to introduce learners to topics that could not be covered in the introductory course. Topics were suggested by the expert reviewers of the curriculum or identified by the scholars themselves (eg, chronic pain, sexuality, or serious mental illness). A secondary function of the webinars was to reach a broader audience. Over time, scholars and webinar attendees requested opportunities to explore topics in greater depth (eg, PTSD later in life). These requests led the webinars to focus on annual themes.

The series is open to all disciplines of geriatric scholars, VHA staff, and non-VHA staff through the Veterans Affairs Talent Management System and the TRAIN Learning Network (train.org). Attendance for the 37 webinars was captured from logins to the virtual learning platform and may underestimate attendance if a group attended on a single screen. Average attendance increased from 157 attendees/webinar in 2015 to 418 attendees/webinar in 2023 (Figure 2). This may have been related to the increase in virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, but represents a 166% increase in audience from the inaugural year of the series.

Advanced Learning Opportunities

To invest in the ongoing growth and development of introductory course graduates, GSP-P developed and offered an advanced workshop in 2019. This multiday workshop focused on further enhancement of geropsychology competencies, with an emphasis on treating older veterans with mental and physical comorbidities. Didactics and experiential learning exercises led by SMEs covered topics such as adjusting to chronic illness, capacity assessment, PTSD, insomnia and sleep changes, chronic pain, and psychological interventions in palliative care and hospice settings. Evaluation findings demonstrated significant improvements from precourse to 6 months postcourse in confidence and knowledge as

To facilitate ongoing and individually tailored learning following the advanced workshop, scholars also developed and executed independent learning plans (ILPs) during a 6-month window with consultation from an experienced geropsychologist. Fifteen of 19 scholars (78.9%) completed ILPs with an average of 3 learning goals listed. After completing the ILPs, scholars endorsed their clinical and/or personal usefulness, citing increased confidence, enhanced skills for use with patients with complex needs, personal fulfillment, and career advancement. Most scholars noted ILPs were feasible and learning resources were accessible. Overall, the evaluation found ILPs to be a valuable way to enhance psychologists’ learning and effectiveness in treating older veterans with complex health needs.20

Clinical Practica

All geriatric scholars who completed the program have additional opportunities for professional development through practicum experiences focused on specific clinical approaches to the care of older veterans, such as dementia care, pain management, geriatric assessment, and palliative care. These practica provide scholars with individualized learning experiences in an individualized or small group setting and may be conducted either in-person or virtually.

In response to an expressed need from those who completed the program, the GSP-P planning committee collaborated with an SME to develop a virtual practicum to assess patients’ decision making capacity. Evaluating capacities among older adults is a common request, yet clinicians report little to no formal training in how to conceptualize and approach these complex questions.21,22 Utilizing an evidence-informed and structured approach promotes the balancing of an older adult’s autonomy and professional ethics. Learning capacity evaluation skills could better position psychologists to not only navigate complex ethical, legal, and clinical situations, but also serve as expert consultants to interdisciplinary teams. This virtual practicum was initiated in 2022 and to date has included 10 scholars. The practicum includes multiple modalities of learning: (1) self-directed review of core concepts; (2) attendance at 4 capacity didactics focused on introduction to evaluating capacities, medical consent and decision making, financial decision making and management, and independent living; and (3) participation in 5 group consultations on capacity evaluations conducted at their home sites. During these group consultations, additional case examples were shared to reinforce capacity concepts.

Discussion

The objective of GSP-P is to enhance geropsychology practice competencies among VHA psychologists given the outsized representation of older adults within the VHA system and their complex care needs. The curricula have significantly evolved to accomplish this, expanding the reach and investing in the continuing growth and development of scholars.

There are several elements that set GSP apart from other geriatric and geropsychology continuing medical education programs. The first is that the training is veteran focused, allowing us to discuss the unique impact military service has on aging. Similarly, because all scholars work within the integrated health care system, we can introduce and review key resources and programs that benefit all veterans and their families/care partners across the system. Through the GSP, the VA invests in ongoing professional development. Scholars can participate in additional experiential practica, webinars, and advanced workshops tailored to their individual learning needs. Lastly, the GSP works to create a community among its scholars where they can not only continue to consult with presenters/instructors, but also one another. A planned future direction for the GSP-P is to incorporate quarterly office hours and discussions for alumni to develop an increased sense of community. This may strengthen commitment to the overall VA mission, leading to increased retainment of talent who now have the knowledge, skills, and confidence to care for aging veterans.

Limitations

GSP is limited by its available funding. Additionally, the number of participants who can enroll each year in GSP-P (not including webinars) is capped by policy. Another limitation is the number of QI coaches available to mentor scholars on their projects.

Conclusions

Outcomes of GSP-P have been extremely favorable. Following participation in the program, we have found a significant increase in confidence in geropsychology practice among clinicians, as well as enhanced knowledge and skills across competency domains.15,19 We have observed rising attendance in our annual webinar series and graduates of our introductory courses participate in subsequent trainings (eg, advanced workshop or virtual practicum). Several graduates of GSP-P have become board certified in geropsychology by the American Board of Geropsychology and many proceed to supervise geropsychology-focused clinical rotations for psychology practicum students, predoctoral interns, and postdoctoral fellows. This suggests that the reach of GSP-P programming may extend farther than reported in this article.

The needs of aging veterans have also changed based on cohort differences, as the population of World War II and Korean War era veterans has declined and the number of older Vietnam era veterans has grown. We expect different challenges with older Gulf War and post-9/11 era veterans. For instance, 17% of troops deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan following 9/11 experienced mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), and 59% of those experienced > 1 mild TBI.23 Research indicates that younger post-9/11 veterans have a 3-fold risk of developing early onset dementia after experiencing a TBI.24 Therefore, even though post-9/11 veterans are not older in terms of chronological age, some may experience symptoms and conditions more often occurring in older veterans. As a result, it would be beneficial for clinicians to learn about the presentation and treatment of geriatric conditions such as dementia.

Moving forward, the GSP-P should identify potential opportunities to collaborate with the non-VHA mental health community–which also faces a shortage of geriatric mental health clinicians–to extend educational opportunities to improve care for veterans in all settings (eg, cosponsor training opportunities open to both VHA and non-VHA clinicians).8,25 Many aging veterans may receive portions of their health care outside the VHA, particularly those who reside in rural areas. Additionally, as veterans age, so do their support systems (eg, family members, friends, spouses, caregivers, and even clinicians), most of whom will receive care outside of the VHA. Community education collaborations will not only improve the care of older veterans, but also the care of older adults in the general population.

Promising directions include the adoption of the GSP model in other health care settings. Recently, Indian Health Service has adapted the model, beginning with primary care clinicians and pharmacists and is beginning to expand to other disciplines. Additional investments in VHA workforce training include the availability of geropsychology internship and fellowship training opportunities through the Office of Academic Affiliations, which provide earlier opportunities to specialize in geropsychology. Continued investment in both prelicensure and postpsychology licensure training efforts are needed within the VHA to meet the geriatric mental health needs of veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Terri Huh, PhD, for her contributions to the development and initiation of the GSP-P. The authors also appreciate the collaboration and quality initiative training led by Carol Callaway-Lane, DNP, ACNP-BC, and her team.

1. Caplan Z, Rabe M; US Department of Commerce, US Census Bureau. The Older Population: 2020 (Census Brief No. C2020BR-07). May 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/2020/census-briefs/c2020br-07.pdf

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. VA benefits & health care utilization. Updated February 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/pocketcards/fy2023q2.PDF

3. O’Malley KA, Vinson L, Pless Kaiser A, Sager Z, Hinrichs K. Mental health and aging veterans: How the Veterans Health Administration meets the needs of aging veterans. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2020;30(1):19-23. doi:10.1093/ppar/prz027

4. Greenberg G, Hoff R. FY 2021 Older Adult (65+ on October 1st) Veteran Data Sheet: National, VISN, and Healthcare System Tables. West Haven, CT: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Northeast Program Evaluation Center. 2022.

5. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.61

6. Davison EH, Kaiser AP, Spiro A 3rd, Moye J, King LA, King DW. From late-onset stress symptomatology to later-adulthood trauma reengagement in aging combat veterans: Taking a broader view. Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):14-21. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv097

7. Kaiser AP, Boyle JT, Bamonti PM, O’Malley K, Moye J. Development, adaptation, and clinical implementation of the Later-Adulthood Trauma Reengagement (LATR) group intervention for older veterans. Psychol Serv. 2023;20(4):863-875. doi:10.1037/ser0000736

8. Moye J, Karel MJ, Stamm KE, et al. Workforce analysis of psychological practice with older adults: Growing crisis requires urgent action. Train Educ Prof Psychol. 2019;13(1):46-55. doi:10.1037/tep0000206

9. Stamm K, Lin L, Conroy J. Critical needs in geropsychology. Monitor on Psychology. 2021;52(4):21.

10. American Board of Geropsychology. Specialists. 2024. Accessed February 6, 2024. https://abgero.org/board-members/specialists/

11. Kramer BJ. The VA Geriatric Scholars Program. Fed Pract. 2015;32(5):46-48.

12. Kramer BJ, Creekmur B, Howe JL, et al. Veterans Affairs Geriatric Scholars Program: Enhancing existing primary care clinician skills in caring for older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):2343-2348. doi:10.1111/jgs.14382

13. Knight BG, Karel MJ, Hinrichsen GA, Qualls SH, Duffy M. Pikes Peak model for training in professional geropsychology. Am Psychol. 2009;64(3):205-14. doi:10.1037/a0015059

14. Huh JWT, Rodriguez R, Gould CE, R Brunskill S, Melendez L, Kramer BJ. Developing a program to increase geropsychology competencies of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) psychologists. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2020;41(4):463-479. doi:10.1080/02701960.2018.1491402

15. Huh JWT, Rodriguez RL, Gregg JJ, Scales AN, Kramer BJ, Gould CE. Improving geropsychology competencies of Veterans Affairs psychologists. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(3):798-805. doi:10.1111/jgs.17029

16. Karel MJ, Emery EE, Molinari V; CoPGTP Task Force on the Assessment of Geropsychology Competencies. Development of a tool to evaluate geropsychology knowledge and skill competencies. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(6):886-896. doi:10.1017/S1041610209991736

17. Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, et al. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2006;29(11):1415-1419.

18. Sullivan J, Gualtieri L, Campbell M, Davila H, Pendergast J, Taylor P. VA Compassionate Contact Corps: a phone-based intervention for veterans interested in speaking with peers. Innov Aging. 2021;5(Suppl 1):204. doi:10.1093/geroni/igab046.788

19. Gregg JJ, Rodriguez RL, Mehta PS, Kramer BJ, Gould CE. Enhancing specialty training in geropsychology competencies: an evaluation of a VA Geriatric Scholars Program advanced topics workshop. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2023;44(3):329-338. doi:10.1080/02701960.2022.2069764

20. Gould CE, Rodriguez RL, Gregg J, Mehta PS, Kramer J. Mentored independent learning plans among psychologists: a mixed methods investigation. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(S1):S53.

21. Mullaly E, Kinsella G, Berberovic N, et al. Assessment of decision-making capacity: exploration of common practices among neuropsychologists. Aust Psychol. 2007;42:178-186. doi:10.1080/00050060601187142

22. Seyfried L, Ryan KA, Kim SYH. Assessment of decision-making capacity: Views and experiences of consultation psychiatrists. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(2):115-123. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2012.08.001

23. Wilk JE, Herrell RK, Wynn GH, Riviere LA, Hoge CW. Mild traumatic brain injury (concussion), posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in U.S. soldiers involved in combat deployments: association with postdeployment symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(3):249-257. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e318244c604

24. Kennedy E, Panahi S, Stewart IJ, et al. Traumatic brain injury and early onset dementia in post 9-11 veterans. Brain Inj. 2022;36(5):620-627.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033846

25. Merz CC, Koh D, Sakai EY, et al. The big shortage: Geropsychologists discuss facilitators and barriers to working in the field of aging. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 2017;3(4):388-399. doi:10.1037/tps0000137

1. Caplan Z, Rabe M; US Department of Commerce, US Census Bureau. The Older Population: 2020 (Census Brief No. C2020BR-07). May 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/2020/census-briefs/c2020br-07.pdf

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. VA benefits & health care utilization. Updated February 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/pocketcards/fy2023q2.PDF

3. O’Malley KA, Vinson L, Pless Kaiser A, Sager Z, Hinrichs K. Mental health and aging veterans: How the Veterans Health Administration meets the needs of aging veterans. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2020;30(1):19-23. doi:10.1093/ppar/prz027

4. Greenberg G, Hoff R. FY 2021 Older Adult (65+ on October 1st) Veteran Data Sheet: National, VISN, and Healthcare System Tables. West Haven, CT: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Northeast Program Evaluation Center. 2022.

5. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.61

6. Davison EH, Kaiser AP, Spiro A 3rd, Moye J, King LA, King DW. From late-onset stress symptomatology to later-adulthood trauma reengagement in aging combat veterans: Taking a broader view. Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):14-21. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv097

7. Kaiser AP, Boyle JT, Bamonti PM, O’Malley K, Moye J. Development, adaptation, and clinical implementation of the Later-Adulthood Trauma Reengagement (LATR) group intervention for older veterans. Psychol Serv. 2023;20(4):863-875. doi:10.1037/ser0000736

8. Moye J, Karel MJ, Stamm KE, et al. Workforce analysis of psychological practice with older adults: Growing crisis requires urgent action. Train Educ Prof Psychol. 2019;13(1):46-55. doi:10.1037/tep0000206

9. Stamm K, Lin L, Conroy J. Critical needs in geropsychology. Monitor on Psychology. 2021;52(4):21.

10. American Board of Geropsychology. Specialists. 2024. Accessed February 6, 2024. https://abgero.org/board-members/specialists/

11. Kramer BJ. The VA Geriatric Scholars Program. Fed Pract. 2015;32(5):46-48.

12. Kramer BJ, Creekmur B, Howe JL, et al. Veterans Affairs Geriatric Scholars Program: Enhancing existing primary care clinician skills in caring for older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):2343-2348. doi:10.1111/jgs.14382

13. Knight BG, Karel MJ, Hinrichsen GA, Qualls SH, Duffy M. Pikes Peak model for training in professional geropsychology. Am Psychol. 2009;64(3):205-14. doi:10.1037/a0015059

14. Huh JWT, Rodriguez R, Gould CE, R Brunskill S, Melendez L, Kramer BJ. Developing a program to increase geropsychology competencies of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) psychologists. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2020;41(4):463-479. doi:10.1080/02701960.2018.1491402

15. Huh JWT, Rodriguez RL, Gregg JJ, Scales AN, Kramer BJ, Gould CE. Improving geropsychology competencies of Veterans Affairs psychologists. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(3):798-805. doi:10.1111/jgs.17029

16. Karel MJ, Emery EE, Molinari V; CoPGTP Task Force on the Assessment of Geropsychology Competencies. Development of a tool to evaluate geropsychology knowledge and skill competencies. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(6):886-896. doi:10.1017/S1041610209991736

17. Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, et al. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2006;29(11):1415-1419.

18. Sullivan J, Gualtieri L, Campbell M, Davila H, Pendergast J, Taylor P. VA Compassionate Contact Corps: a phone-based intervention for veterans interested in speaking with peers. Innov Aging. 2021;5(Suppl 1):204. doi:10.1093/geroni/igab046.788

19. Gregg JJ, Rodriguez RL, Mehta PS, Kramer BJ, Gould CE. Enhancing specialty training in geropsychology competencies: an evaluation of a VA Geriatric Scholars Program advanced topics workshop. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2023;44(3):329-338. doi:10.1080/02701960.2022.2069764

20. Gould CE, Rodriguez RL, Gregg J, Mehta PS, Kramer J. Mentored independent learning plans among psychologists: a mixed methods investigation. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(S1):S53.

21. Mullaly E, Kinsella G, Berberovic N, et al. Assessment of decision-making capacity: exploration of common practices among neuropsychologists. Aust Psychol. 2007;42:178-186. doi:10.1080/00050060601187142

22. Seyfried L, Ryan KA, Kim SYH. Assessment of decision-making capacity: Views and experiences of consultation psychiatrists. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(2):115-123. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2012.08.001

23. Wilk JE, Herrell RK, Wynn GH, Riviere LA, Hoge CW. Mild traumatic brain injury (concussion), posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in U.S. soldiers involved in combat deployments: association with postdeployment symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(3):249-257. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e318244c604

24. Kennedy E, Panahi S, Stewart IJ, et al. Traumatic brain injury and early onset dementia in post 9-11 veterans. Brain Inj. 2022;36(5):620-627.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033846

25. Merz CC, Koh D, Sakai EY, et al. The big shortage: Geropsychologists discuss facilitators and barriers to working in the field of aging. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 2017;3(4):388-399. doi:10.1037/tps0000137