User login

Effect of Parental Adverse Childhood Experiences and Resilience on a Child’s Healthcare Reutilization

Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, include exposure to abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction (eg, having a parent who is mentally ill) as a child.1 Exposure to ACEs affects health into adulthood, with a dose-response relationship between ACEs and a range of comorbidities.1 Adults with 6 or more ACEs have a 20-year shorter life expectancy than do those with no ACEs.1 Still, ACEs are static; once experienced, that experience cannot be undone. However, resilience, or positive adaptation in the context of adversity, can be protective, buffering the negative effects of ACEs.2,3 Protective factors that promote resilience include social capital, such as positive relationships with caregivers and peers.3

With their clear link to health outcomes across the life-course, there is a movement for pediatricians to screen children for ACEs4 and to develop strategies that promote resilience in children, parents, and families. However, screening a child for adversity has challenges because younger children may not have experienced an adverse exposure, or they may be unable to voice their experiences. Studies have demonstrated that parental adversity, or ACEs, may be a marker for childhood adversity.5,6 Biological models also support this potential intergenerational effect of ACEs. Chronic exposure to stress, including ACEs, results in elevated cortisol via a dysregulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which results in chronic inflammation.7 This “toxic stress” is prolonged, severe in intensity, and can lead to epigenetic changes that may be passed on to the next generation.8,9

Hospitalization of an ill child, and the transition to home after that hospitalization, is a stressful event for children and families.10 This stress may be relevant to parents that have a history of a high rate of ACEs or a current low degree of resilience. Our previous work demonstrated that, in the inpatient setting, parents with high ACEs (≥4) or low resilience have increased coping difficulty 14 days after their child’s hospital discharge.11 Our objective here was to evaluate whether a parent’s ACEs and/or resilience would also be associated with that child’s likelihood of reutilization. We hypothesized that more parental ACEs and/or lower parental resilience would be associated with revisits the emergency room, urgent care, or hospital readmissions.

METHODS

Participants and Study Design

We conducted a prospective cohort study of parents of hospitalized children recruited from the “Hospital-to-Home Outcomes” Studies (H2O I and H2O II).12,13 H2O I and II were prospective, single-center, randomized controlled trials designed to determine the effectiveness of either a nurse-led transitional home visit (H2O I) or telephone call (H2O II) on 30-day unplanned healthcare reutilization. The trials and this study were approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Institutional Review Board. All parents provided written informed consent.

Details of H2O I and II recruitment and design have been described previously.12,13 Briefly, children were eligible for inclusion in either study if they were admitted to our institution’s general Hospital Medicine or the Hospital Medicine Complex Care Services; for H2O I, children hospitalized on the Neurology and Neurosurgery services were also eligible.12,13 Patients were excluded if they were discharged to a residential facility, if they lived outside the home healthcare nurse service area, if they were eligible for skilled home healthcare services (eg, intravenous antibiotics), or if the participating caregiver was non-English speaking.12,13 In H2O I, families were randomized either to receive a single nurse home visit within 96 hours of discharge or standard of care. In H2O II, families enrolled were randomized to receive a telephone call by a nurse within 96 hours of discharge or standard of care. As we have previously published, randomization in both trials successfully balanced the intervention and control arms with respect to key demographic characteristics.12,13 For the analyses presented here, we focused on a subset of caregivers 18 years and older whose children were enrolled in either H2O I or II between August 2015 and October 2016. In both H2O trials, face-to-face and paper-based questionnaires were completed by parents during the index hospitalization.

Outcome and Predictors

Our primary outcome was unanticipated healthcare reutilization defined as return to the emergency room, urgent care, or unplanned readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge, consistent with the H2O trials. This was measured using the primary institution’s administrative data supplemented by a utilization database shared across regional hospitals.14 Readmissions were identified as “unplanned” using a previously validated algorithm,15 and treated as a dichotomous yes/no variable.

Our primary predictors were parental ACEs and resilience (see Appendix Tables). The ACE questionnaire addresses abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction in the first 18 years of life.1 It is composed of 10 questions, each with a yes/no response.1 We defined parents as low (ACE 0), moderate (ACE 1-3), or high (ACE ≥4) risk a priori because previous literature has described poor outcomes in adults with 4 or more ACEs.16

Given the sensitive nature of the questions, respondents independently completed the ACE questionnaire on paper instead of via the face-to-face survey. Respondents returned the completed questionnaire to the research assistant in a sealed envelope. All families received educational information on relevant hospital and community-based resources (eg, social work).

Parental resilience was measured using the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS). The BRS is 6 items, each on a 5-point Likert scale. Responses were averaged, providing a total score of 1-5; higher scores are representative of higher resilience.17 We treated the BRS score as a continuous variable. BRS has been used in clinical settings; it has demonstrated positive correlation with social support and negative correlation with fatigue.17 Parents answered BRS questions during the index pediatric hospitalization in a face-to-face interview.

Parent and Child Characteristics

Parent and child sociodemographic variables were also obtained during the face-to-face interview. Parental variables included age, gender, educational attainment, household income, employment status, and financial and social strain.11 Educational attainment was analyzed in 2 categories—high school or less vs more than high school—because most discharge instructions are written at a high school reading level.18 Parents reported their annual household income in the following categories: <$15,000; $15,000-$29,999; $30,000-$44,999; $45,000-$59,999; $60,000-$89,999; $90,000-$119,999; ≥$120,000. Employment was dichotomized as not employed/student vs any employment. Financial and social strain were assessed using a series of 9 previously described questions.19 These questions assessed, via self-report, a family’s ability to make ends meet, ability to pay rent/mortgage or utilities, need to move in with others because of financial reasons, and ability to borrow money if needed, as well as home ownership and parental marital status.15,19 Strain questions were all dichotomous (yes/no, single/not single). A composite variable was then constructed that categorized those reporting no strain items, 1 to 2 items, 3 to 4 items, and 5 or more items.20

Child variables included race, ethnicity, age, primary care access,21 payer, and H2O treatment arm. Race categories were white/Caucasian, black/African American, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, and other; ethnicity categories were Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic/Latino, and unknown. Given relatively low numbers of children reported to be Hispanic/Latino, we combined race and ethnicity into a single variable, categorized as non-Hispanic/white, non-Hispanic/black, and multiracial/Hispanic/other. Primary care access was assessed using the access subscale to the Parent’s Perception of Primary Care questionnaire. This includes assessment of a family’s ability to travel to their doctor, to see their doctor for routine or sick care, and to get help or advice on evenings or weekends. Scores were categorized as always adequate, almost always adequate, or sometimes/never adequate.21 Payer was dichotomized to private or public/self-pay.

Statistical Analyses

We examined the distribution of outcomes, predictors, and covariates. We compared sociodemographic characteristics of those respondents and nonrespondents to the ACE screen using the chi-square test for categorical variables or the t test for continuous variables. We used logistic regression to assess for associations between the independent variables of interest and reutilization, adjusting for potential confounders. To build our adjusted, multivariable model, we decided a priori to include child race/ethnicity, primary care access, financial and social strain, and trial treatment arm. We treated the H2O I control group as the referent group. Other covariates considered for inclusion were caregiver education, household income, employment, and payer. These were included in multivariable models if bivariate associations were significant at the P < .1 level. We assessed an ACE-by-resilience interaction term because we hypothesized that those with more ACEs and lower resilience may have more reutilization outcomes than parents with fewer ACEs and higher resilience. We also evaluated interaction terms between trial arm assignment and predictors to assess effects that may be introduced by the randomization. Predictors in the final logistic regression model were significant at the P < .05 level. Logistic regression assumption of little or no multicollinearity among the independent variables was verified in the final models. All analyses were performed with Stata v16 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

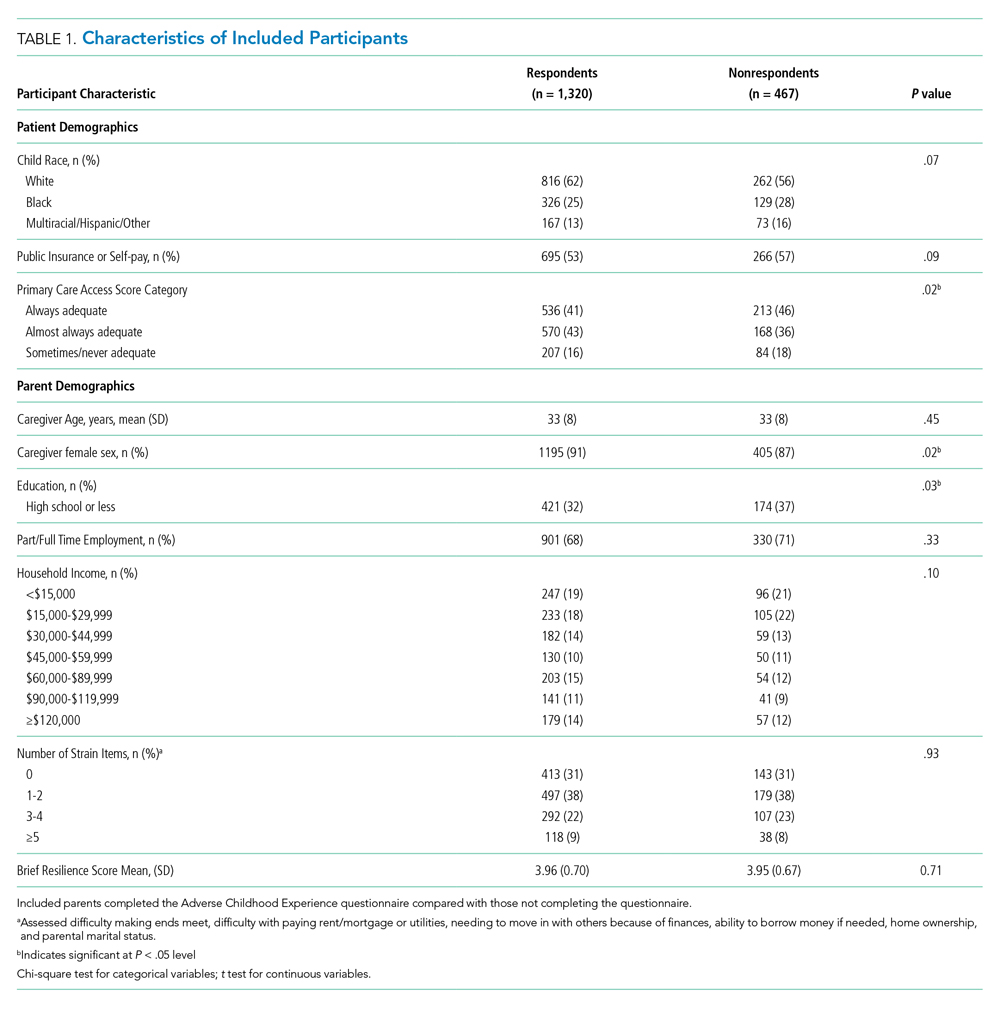

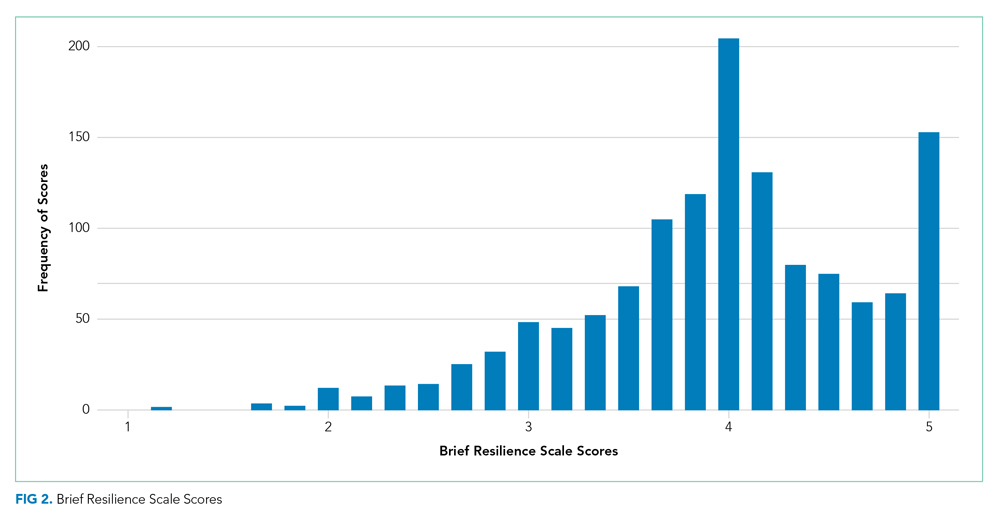

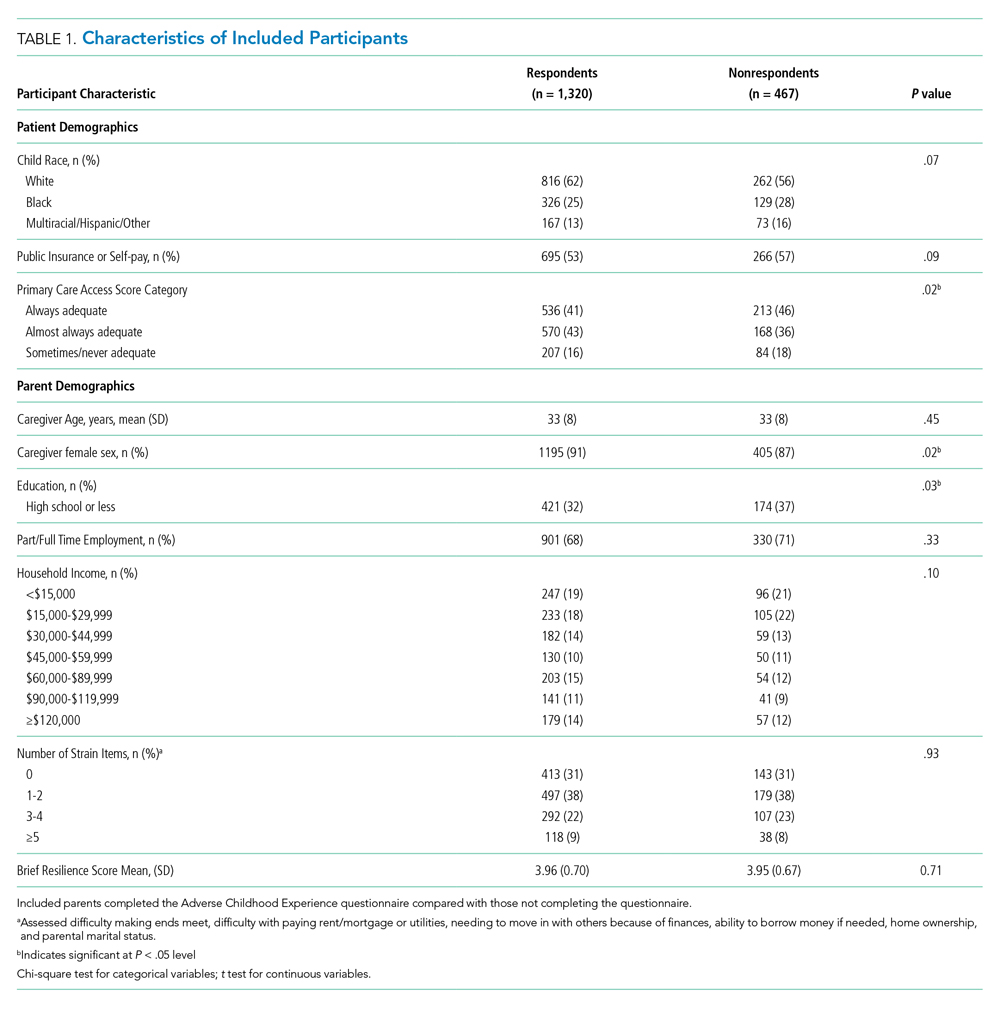

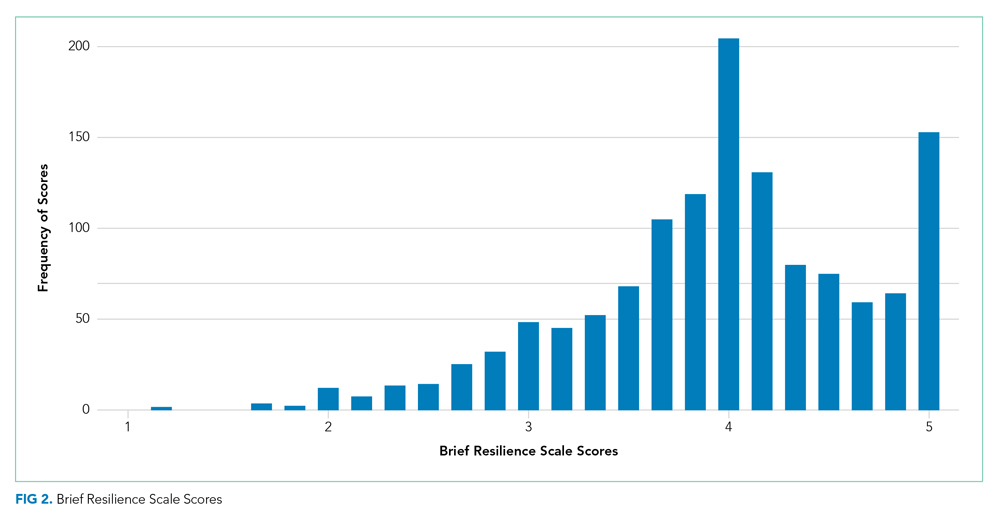

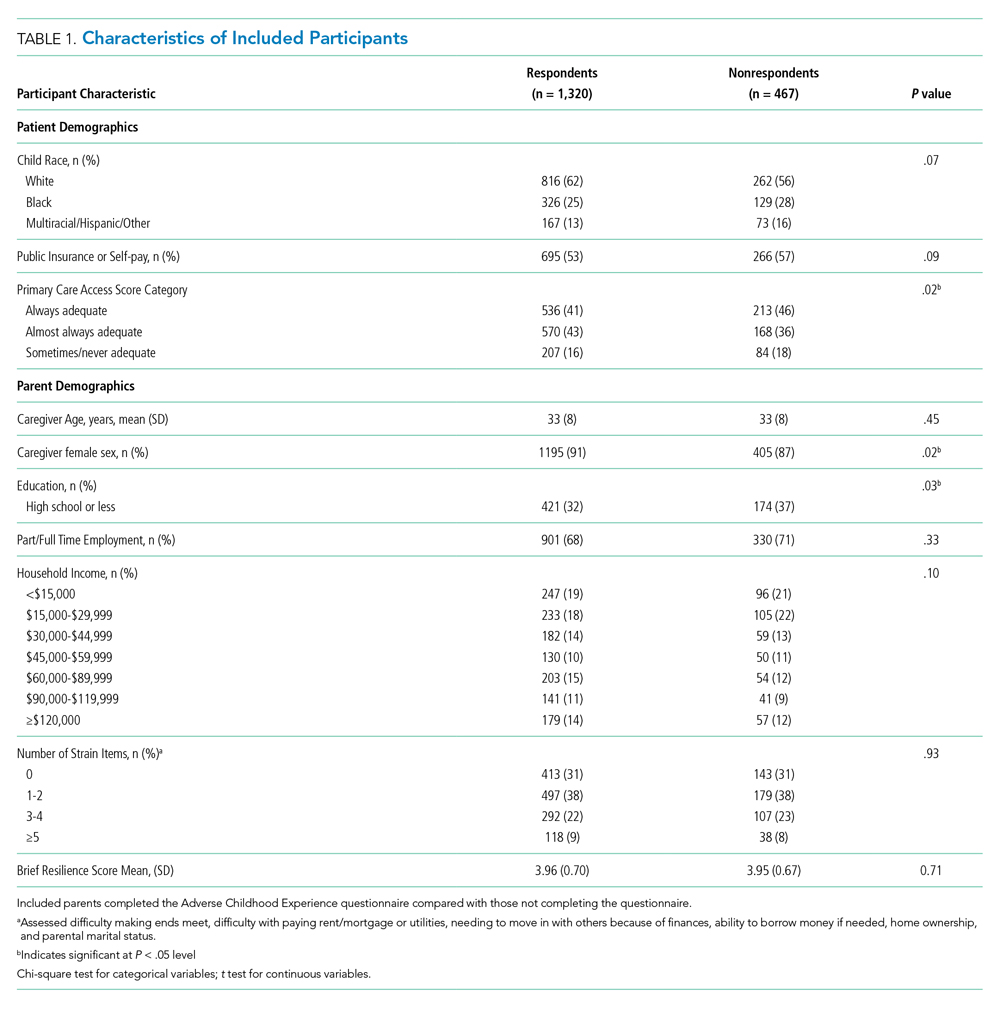

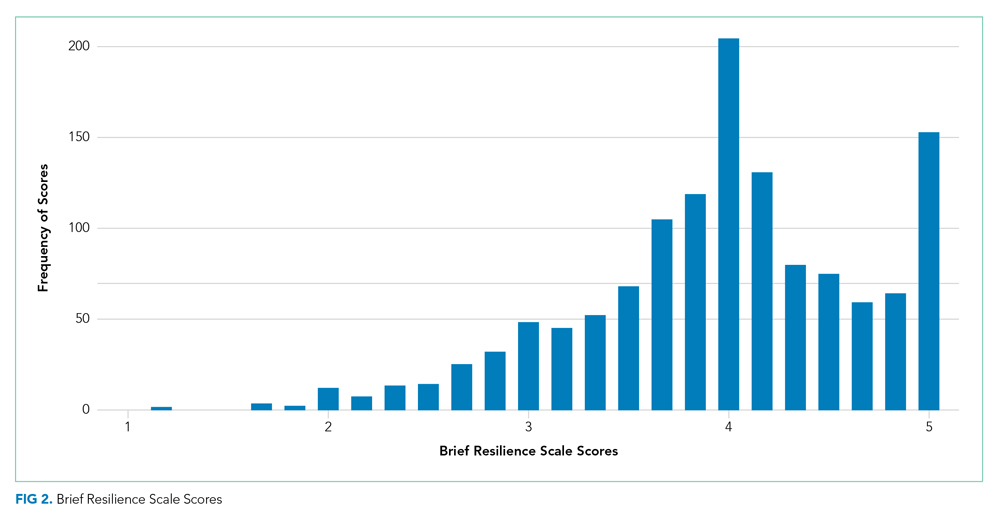

There were a total of 1,787 parent-child dyads enrolled in the H2O I and II during the study period; 1,320 parents (74%) completed the ACE questionnaire and were included the analysis. Included parents were primarily female and employed, as well as educated beyond high school (Table 1). Overall, 64% reported one or more ACEs (range 0 to 9); 45% reported 1to 3, and 19% reported 4 or more ACEs. The most commonly reported ACEs were divorce (n = 573, 43%), exposure to alcoholism (n = 306, 23%), and exposure to mental illness (n = 281, 21%; Figure 1). Parents had a mean BRS score of 3.97 (range 1.17-5.00), with the distribution shown in Figure 2.

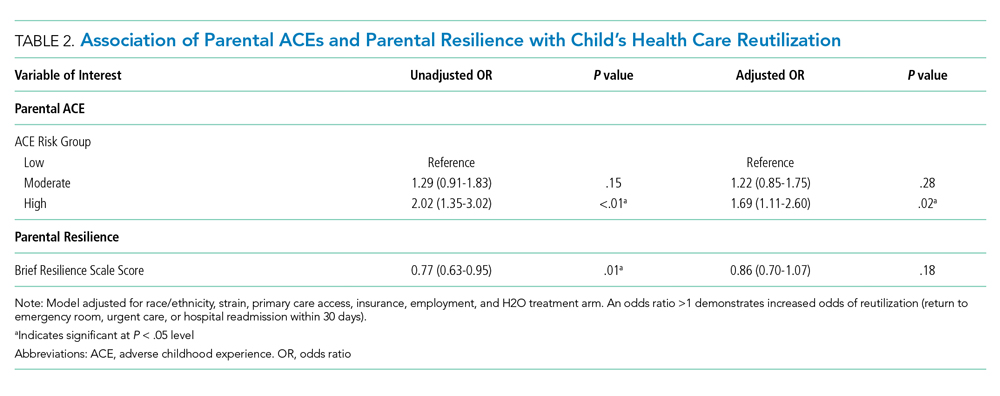

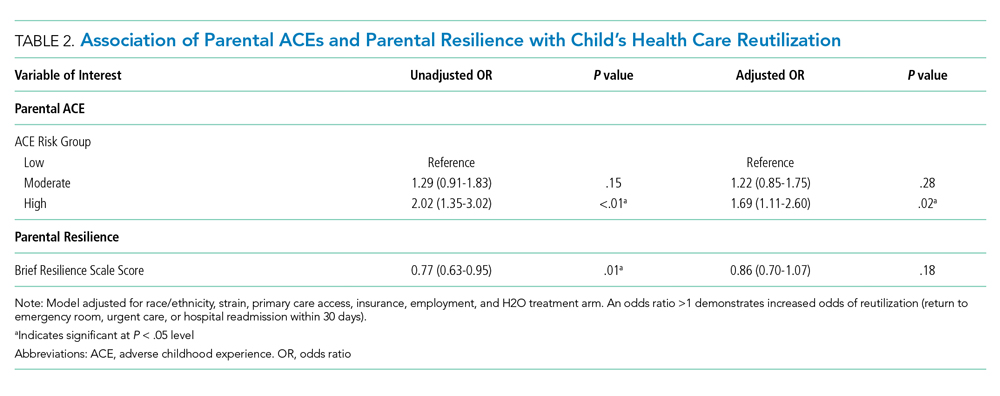

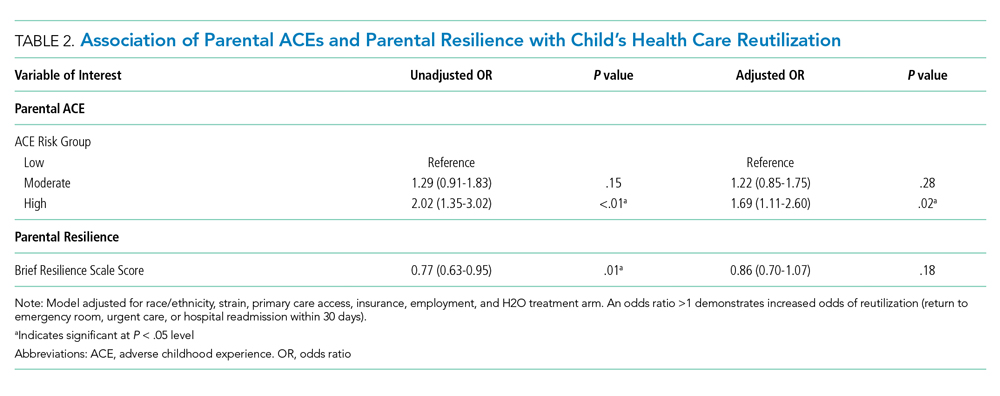

Of the 1,320 included patients, the average length of stay was 2.5 days, and 82% of hospitalizations were caused by acute medical issues (eg, bronchiolitis). A total of 211 children experienced a reutilization event within 30 days of discharge. In bivariate analysis, children with parents with 4 or more ACEs had a 2.02-times (95% CI 1.35-3.02) higher odds of experiencing a reutilization event than did those with parents reporting no ACEs. Parents with higher resilience scores had children with a lower odds of reutilization (odds ratio [OR] 0.77 95% CI 0.63-0.95).

In addition to our a priori variables, parental education, employment, and insurance met our significance threshold for inclusion in the multivariable model. The ACE-by-resilience interaction term was not significant and not included in the model. Similarly, there was no significant interaction between ACE and resilience and H2O treatment arm; the interaction terms were not included in the final adjusted model, but treatment arm assignment was kept as a covariate. A total of 1,292 children, out of the 1,320 respondents, remained in the final multivariable model; the excluded 28 had incomplete covariate data but were not otherwise different. In this final adjusted model, children with parents reporting 4 or more ACEs had a 1.69-times (95% CI 1.11-2.60) greater odds of reutilization than did those with parents reporting no ACEs (Table 2). Resilience failed to reach statistical significance in the adjusted model (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.70-1.07).

DISCUSSION

We found that high-risk parents (4 or more ACEs) had children with an increased odds of healthcare reutilization, suggesting intergenerational effects of ACEs. We did not find a similar effect relating to parental resilience. We also did not find an interaction between parental ACEs and resilience, suggesting that a parent’s reported degree of resilience does not modify the effect of ACEs on reutilization risk.

Parental adversity may be a risk factor for a child’s unanticipated reutilization. We previously demonstrated that parents with 4 or more ACEs have more coping difficulty than a parent with no ACEs after a child’s hospitalization.11 It is possible that parents with high adversity may have poorer coping mechanisms when dealing with a stressful situation, such as a child’s hospitalization. This may have resulted in inequitable outcomes (eg, increased reutilization) for their children. Other studies have confirmed such an intergenerational effect of adversity, linking a parent’s ACEs with poor developmental, behavioral, and health outcomes in their children.6,22,23 O’Malley et al showed an association of parental ACEs to current adversities,24 such as insurance or housing concerns, that affect the entirety of the household, including children. In short, it appears that parental ACEs may be a compelling predictor of current childhood adversity.

Resilience buffers the negative effects of ACEs; however, we did not find significant associations between resilience and reutilization or an interaction between ACEs and resilience. The factors that may contribute to reutilization are complex. In our previous work, parental resilience was associated with coping difficulty after discharge; but again, did not interact with parental ACEs.11 Here, we suggest that while resilience may buffer the negative effects of ACEs, that buffering may not affect the likelihood of reutilization. It is also possible that the BRS tool is of less relevance on how one handles the stress of a child’s hospitalization. While the BRS is one measure of resilience, there are many other relevant constructs to resilience, such as connection to social supports, that also may also contribute to risk of reutilization.25

Reducing the stress of a hospitalization itself and promoting a safe transition from hospital to home is critical to improving child health outcomes. Our data here, and in our previous work, demonstrate that a history of adversity and one’s current coping ability may drive a parent’s response to a child’s hospitalization and affect their capacity to care for that child after hospital discharge.11 Additional in-hospital supports like child life, behavioral health, or pastoral care could reduce the stress of the hospitalization while also building positive coping mechanisms.26-29 A meta-analysis demonstrated that such coping interventions can help alleviate the stress of a hospitalization.30 Hill et al demonstrated successful stress reduction in parents of hospitalized children using a “Coping Kit for Parents.”31 Further studies are warranted to understand which interventions are most effective for children and families and whether they could be more effectively deployed if the inpatient team knew more about parental ACEs.

Screening for parental ACEs could help to identify patients at highest risk for a poor transition to home. Therefore, screening for parental adversity in clinical settings, including inpatient settings, may be relevant and valuable.32 Additionally, by recognizing the high prevalence of ACEs in an inpatient setting, hospitals and healthcare organizations could be motivated to develop and enact trauma-informed approaches. A trauma-informed care approach recognizes the intersection of trauma with health and social problems. With this recognition, care teams can more sensitively address the trauma as they provide relevant services.33 Trauma-informed care is a secondary public health prevention approach that would help team members identify the prevalence and effects of trauma via screening, recognize the signs of a maladaptive response to stress, and respond by integrating awareness of trauma into practice management.28,34 Both the National Academy of Medicine and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality have called for such a trauma-informed approach in primary care.35 In response, many healthcare organizations have developed trauma-informed practices to better address the needs of the populations they serve. For example, provider training on this approach has led to improved rapport in patient-provider relationships.36

Although ACE awareness is a component of trauma-informed care, there are still limitations of the original ACE questionnaire developed by Felitti et al. The existing tool is not inclusive of all adversities a parent or child may face. Moreover, its focus is on past exposures and experiences and not current health-related social needs (eg, food insecurity) which have known linkages with a range of health outcomes and health disparities.37 Additionally, the original ACE questionnaire was created as a population level tool and not as a screening tool. If used as a screening tool, providers may view the questions as too sensitive to ask, and parents may have difficulty responding to and understanding the relevance to their child’s care. Therefore, we suggest that more evidence is required to understand how to best adapt ACE questions into a screening processes that may be implemented in a medical setting.

More evidence is also needed to determine when and where such screening may be most useful. A primary care provider would be best equipped to screen caregivers for ACEs given their established relationship with parents and patients. Given the potential relevance of such information for inpatient care provision, information could then flow from primary care to the inpatient team. However, because not all patients have established primary care providers and only 4% of pediatricians screen for ACEs,38 it is important for inpatient medical teams to understand their role in identifying and addressing ACEs during hospital stays. Development of a screening tool, with input from all stakeholders—including parents—that is valid and feasible for use in a pediatric inpatient setting would be an important step forward. This tool should be paired with training in how to discuss these topics in a trauma-informed, nonjudgmental, empathic manner. We see this as a way in which providers can more effectively elicit an accurate response while simultaneously educating parents on the relevance of such sensitive topics during an acute hospital stay. We also recommend that screening should always be paired with response capabilities that connect those who screen positive with resources that could help them to navigate the stress experienced during and after a child’s hospitalization. Furthermore, communication with primary care providers about parents that screen positive should be integrated into the transition process.

This work has several limitations. First, our study was a part of randomized controlled trials conducted in one academic setting, which thereby limits generalizability. For example, we limited our cohort to those who were English-speaking patients only. This may bias our results because respondents with limited English proficiency may have different risk profiles than their English-speaking peers. In addition, the administration of the both the ACE and resilience questionnaires occurred during an acutely stressful period, which may influence how a parent responds to these questions. Also, both of the surveys are self-reported by parents, which may be susceptible to memory and response biases. Relatedly, we had a high number of nonrespondents, particularly to the ACE questionnaire. Our results are therefore only relevant to those who chose to respond and cannot be applied to nonrespondents. Further work assessing why one does or does not respond to such sensitive questions is an important area for future inquiry. Lastly, our cohort had limited medical complexity; future studies may consider links between parental ACEs (and resilience) and morbidity experienced by children with medical complexity.

CONCLUSION

Parents history of adversity is linked to their children’s unanticipated healthcare reutilization after a hospital discharge. Screening for parental stressors during a hospitalization may be an important first step to connecting parents and children to evidence-based interventions capable of mitigating the stress of hospitalization and promoting better, more seamless transitions from hospital to home.

Acknowledgments

Group Members: The following H2O members are nonauthor contributors: JoAnne Bachus, BSN, RN; Monica Borell, BSN, RN; Lenisa V Chang, MA, PhD; Patricia Crawford, RN; Sarah Ferris, BA; Jennifer Gold, BSN, RN; Judy A Heilman, BSN, RN; Jane C Khoury, PhD; Pierce Kuhnell, MS; Karen Lawley, BSN, RN; Margo Moore, MS, BSN, RN; Lynne O’Donnell, BSN, RN; Sarah Riddle, MD; Susan N Sherman, DPA; Angela M Statile, MD, MEd; Karen P Sullivan, BSN, RN; Heather Tubbs-Cooley, PhD, RN; Susan Wade-Murphy, MSN, RN; and Christine M White, MD, MAT.

The authors also thank David Keller, MD, for his guidance on the study.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial relationships or conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding Source

Supported by funds from the Academic Pediatric Young Investigator Award (Dr A Shah) and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award (IHS-1306-0081, to Dr K Auger, Dr S Shah, Dr H Sucharew, Dr J Simmons), the National Institutes of Health (1K23AI112916, to Dr AF Beck), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K12HS026393-01, to Dr A Shah, K08-HS024735- 01A1, to Dr K Auger). Dr J Haney received Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship funding through the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Disclaimer

All statements in this report, including findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, its Board of Governors, or the Methodology Committee.

1. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8.

2. Bethell CD, Newacheck P, Hawes E, Halfon N. Adverse childhood experiences: assessing the impact on health and school engagement and the mitigating role of resilience. Health Aff. 2014;33(12):2106-2115. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0914.

3. Masten AS. Ordinary Magic. Resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):227-238. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227.

4. Garner AS, Shonkoff JP, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of C, et al. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e224-231. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2662.

5. Randell KA, O’Malley D, Dowd MD. Association of parental adverse childhood experiences and current child adversity. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(8):786-787. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0269.

6. Le-Scherban F, Wang X, Boyle-Steed KH, Pachter LM. Intergenerational associations of parent adverse childhood experiences and child health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20174274. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4274.

7. Johnson SB, Riley AW, Granger DA, Riis J. The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):319-327. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0469.

8. Roth TL, Lubin FD, Funk AJ, Sweatt JD. Lasting epigenetic influence of early-life adversity on the BDNF gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):760-769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.028.

9. Garner AS, Forkey H, Szilagyi M. Translating developmental science to address childhood adversity. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(5):493-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.05.010.

10. Weiss M, Johnson NL, Malin S, Jerofke T, Lang C, Sherburne E. Readiness for discharge in parents of hospitalized children. J Pediatr Nurs. 2008;23(4):282-295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2007.10.005.

11. Shah AN, Beck AF, Sucharew HJ, et al. Parental adverse childhood experiences and resilience on coping after discharge. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172127. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2127.

12. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: The Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) Trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3919.

13. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482.

14. TheHealthCollaborative. Healthbridge analytics. http://healthcollab.org/hbanalytics/. Accessed August 11, 2017.

15. Auger K, Mueller E, Weinberg S, et al. A validated method for identifying unplanned pediatric readmission. J Pediatr. 2016;170:105-12.e122. https://doi.org10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.051.

16. Felitti VJ. Belastungen in der Kindheit und Gesundheit im Erwachsenenalter: die Verwandlung von Gold in Blei [The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult health: turning gold into lead]. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2002;48(4):359-369. https://doi.org/10.13109/zptm.2002.48.4.359.

17. Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(3):194-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972.

18. Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS. Health literacy and the risk of hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(12):791-798. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00242.x.

19. Auger KA, Kahn RS, Simmons JM, et al. Using address information to identify hardships reported by families of children hospitalized with asthma. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(1):79-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.07.003.

20. Auger KA, Kahn RS, Davis MM, Simmons JM. Pediatric asthma readmission: asthma knowledge is not enough? J Pediatr. 2015;166(1):101-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.046.

21. Seid M, Varni JW, Bermudez LO, et al. Parents’ perceptions of primary care: measuring parents’ experiences of pediatric primary care quality. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):264-270. https://doi:10.1542/peds.108.2.264.

22. Schickedanz A, Halfon N, Sastry N, Chung PJ. Parents’ adverse childhood experiences and their children’s behavioral health problems. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0023.

23. Folger AT, Eismann EA, Stephenson NB, et al. Parental adverse childhood experiences and offspring development at 2 years of age. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172826. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2826.

24. O’Malley DM, Randell KA, Dowd MD. Family adversity and resilience measures in pediatric acute care settings. Public Health Nurs. 2016;33(1):3-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12246.

25. Masten AS. Resilience in developing systems: the promise of integrated approaches. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2016;13(3):297-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1147344.

26. Burns-Nader S, Hernandez-Reif M. Facilitating play for hospitalized children through child life services. Child Health Care. 2016;45(1):1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02739615.2014.948161.

27. Feudtner C, Haney J, Dimmers MA. Spiritual care needs of hospitalized children and their families: a national survey of pastoral care providers’ perceptions. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e67-e72. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.1.e67.

28. Kazak AE, Schneider S, Didonato S, Pai AL. Family psychosocial risk screening guided by the Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model (PPPHM) using the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT). Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):574-580. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2014.995774.

29. Kodish I. Behavioral health care for children who are medically hospitalized. Pediatr Ann. 2018;47(8):e323-e327. https://doi.org/10.3928/19382359-20180705-01.

30. Doupnik SK, Hill D, Palakshappa D, et al. Parent coping support interventions during acute pediatric hospitalizations: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-4171.

31. Hill DL, Carroll KW, Snyder KJG, et al. Development and pilot testing of a coping kit for parents of hospitalized children. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(4):454-463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.11.001.

32. Bronner MB, Peek N, Knoester H, Bos AP, Last BF, Grootenhuis MA. Course and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in parents after pediatric intensive care treatment of their child. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(9):966-974. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsq004.

33. Bowen EA, Murshid NS. Trauma-informed social policy: a conceptual framework for policy analysis and advocacy. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):223-229. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302970.

34. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2014.

35. Machtinger EL, Cuca YP, Khanna N, Rose CD, Kimberg LS. From treatment to healing: the promise of trauma-informed primary care. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25(3):193-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2015.03.008.

36. Green BL, Saunders PA, Power E, et al. Trauma-informed medical care: patient response to a primary care provider communication training. J Loss Trauma . 2016;21(2):147-159. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2015.1084854.

37. McKay S, Parente V. Health Disparities in the Hospitalized Child. Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9(5):317-325. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2018-0223.

38. Kerker BD, Storfer-Isser A, Szilagyi M, et al. Do pediatricians ask about adverse childhood experiences in pediatric primary care? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(2):154-160. https://doi.org/10.1

Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, include exposure to abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction (eg, having a parent who is mentally ill) as a child.1 Exposure to ACEs affects health into adulthood, with a dose-response relationship between ACEs and a range of comorbidities.1 Adults with 6 or more ACEs have a 20-year shorter life expectancy than do those with no ACEs.1 Still, ACEs are static; once experienced, that experience cannot be undone. However, resilience, or positive adaptation in the context of adversity, can be protective, buffering the negative effects of ACEs.2,3 Protective factors that promote resilience include social capital, such as positive relationships with caregivers and peers.3

With their clear link to health outcomes across the life-course, there is a movement for pediatricians to screen children for ACEs4 and to develop strategies that promote resilience in children, parents, and families. However, screening a child for adversity has challenges because younger children may not have experienced an adverse exposure, or they may be unable to voice their experiences. Studies have demonstrated that parental adversity, or ACEs, may be a marker for childhood adversity.5,6 Biological models also support this potential intergenerational effect of ACEs. Chronic exposure to stress, including ACEs, results in elevated cortisol via a dysregulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which results in chronic inflammation.7 This “toxic stress” is prolonged, severe in intensity, and can lead to epigenetic changes that may be passed on to the next generation.8,9

Hospitalization of an ill child, and the transition to home after that hospitalization, is a stressful event for children and families.10 This stress may be relevant to parents that have a history of a high rate of ACEs or a current low degree of resilience. Our previous work demonstrated that, in the inpatient setting, parents with high ACEs (≥4) or low resilience have increased coping difficulty 14 days after their child’s hospital discharge.11 Our objective here was to evaluate whether a parent’s ACEs and/or resilience would also be associated with that child’s likelihood of reutilization. We hypothesized that more parental ACEs and/or lower parental resilience would be associated with revisits the emergency room, urgent care, or hospital readmissions.

METHODS

Participants and Study Design

We conducted a prospective cohort study of parents of hospitalized children recruited from the “Hospital-to-Home Outcomes” Studies (H2O I and H2O II).12,13 H2O I and II were prospective, single-center, randomized controlled trials designed to determine the effectiveness of either a nurse-led transitional home visit (H2O I) or telephone call (H2O II) on 30-day unplanned healthcare reutilization. The trials and this study were approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Institutional Review Board. All parents provided written informed consent.

Details of H2O I and II recruitment and design have been described previously.12,13 Briefly, children were eligible for inclusion in either study if they were admitted to our institution’s general Hospital Medicine or the Hospital Medicine Complex Care Services; for H2O I, children hospitalized on the Neurology and Neurosurgery services were also eligible.12,13 Patients were excluded if they were discharged to a residential facility, if they lived outside the home healthcare nurse service area, if they were eligible for skilled home healthcare services (eg, intravenous antibiotics), or if the participating caregiver was non-English speaking.12,13 In H2O I, families were randomized either to receive a single nurse home visit within 96 hours of discharge or standard of care. In H2O II, families enrolled were randomized to receive a telephone call by a nurse within 96 hours of discharge or standard of care. As we have previously published, randomization in both trials successfully balanced the intervention and control arms with respect to key demographic characteristics.12,13 For the analyses presented here, we focused on a subset of caregivers 18 years and older whose children were enrolled in either H2O I or II between August 2015 and October 2016. In both H2O trials, face-to-face and paper-based questionnaires were completed by parents during the index hospitalization.

Outcome and Predictors

Our primary outcome was unanticipated healthcare reutilization defined as return to the emergency room, urgent care, or unplanned readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge, consistent with the H2O trials. This was measured using the primary institution’s administrative data supplemented by a utilization database shared across regional hospitals.14 Readmissions were identified as “unplanned” using a previously validated algorithm,15 and treated as a dichotomous yes/no variable.

Our primary predictors were parental ACEs and resilience (see Appendix Tables). The ACE questionnaire addresses abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction in the first 18 years of life.1 It is composed of 10 questions, each with a yes/no response.1 We defined parents as low (ACE 0), moderate (ACE 1-3), or high (ACE ≥4) risk a priori because previous literature has described poor outcomes in adults with 4 or more ACEs.16

Given the sensitive nature of the questions, respondents independently completed the ACE questionnaire on paper instead of via the face-to-face survey. Respondents returned the completed questionnaire to the research assistant in a sealed envelope. All families received educational information on relevant hospital and community-based resources (eg, social work).

Parental resilience was measured using the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS). The BRS is 6 items, each on a 5-point Likert scale. Responses were averaged, providing a total score of 1-5; higher scores are representative of higher resilience.17 We treated the BRS score as a continuous variable. BRS has been used in clinical settings; it has demonstrated positive correlation with social support and negative correlation with fatigue.17 Parents answered BRS questions during the index pediatric hospitalization in a face-to-face interview.

Parent and Child Characteristics

Parent and child sociodemographic variables were also obtained during the face-to-face interview. Parental variables included age, gender, educational attainment, household income, employment status, and financial and social strain.11 Educational attainment was analyzed in 2 categories—high school or less vs more than high school—because most discharge instructions are written at a high school reading level.18 Parents reported their annual household income in the following categories: <$15,000; $15,000-$29,999; $30,000-$44,999; $45,000-$59,999; $60,000-$89,999; $90,000-$119,999; ≥$120,000. Employment was dichotomized as not employed/student vs any employment. Financial and social strain were assessed using a series of 9 previously described questions.19 These questions assessed, via self-report, a family’s ability to make ends meet, ability to pay rent/mortgage or utilities, need to move in with others because of financial reasons, and ability to borrow money if needed, as well as home ownership and parental marital status.15,19 Strain questions were all dichotomous (yes/no, single/not single). A composite variable was then constructed that categorized those reporting no strain items, 1 to 2 items, 3 to 4 items, and 5 or more items.20

Child variables included race, ethnicity, age, primary care access,21 payer, and H2O treatment arm. Race categories were white/Caucasian, black/African American, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, and other; ethnicity categories were Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic/Latino, and unknown. Given relatively low numbers of children reported to be Hispanic/Latino, we combined race and ethnicity into a single variable, categorized as non-Hispanic/white, non-Hispanic/black, and multiracial/Hispanic/other. Primary care access was assessed using the access subscale to the Parent’s Perception of Primary Care questionnaire. This includes assessment of a family’s ability to travel to their doctor, to see their doctor for routine or sick care, and to get help or advice on evenings or weekends. Scores were categorized as always adequate, almost always adequate, or sometimes/never adequate.21 Payer was dichotomized to private or public/self-pay.

Statistical Analyses

We examined the distribution of outcomes, predictors, and covariates. We compared sociodemographic characteristics of those respondents and nonrespondents to the ACE screen using the chi-square test for categorical variables or the t test for continuous variables. We used logistic regression to assess for associations between the independent variables of interest and reutilization, adjusting for potential confounders. To build our adjusted, multivariable model, we decided a priori to include child race/ethnicity, primary care access, financial and social strain, and trial treatment arm. We treated the H2O I control group as the referent group. Other covariates considered for inclusion were caregiver education, household income, employment, and payer. These were included in multivariable models if bivariate associations were significant at the P < .1 level. We assessed an ACE-by-resilience interaction term because we hypothesized that those with more ACEs and lower resilience may have more reutilization outcomes than parents with fewer ACEs and higher resilience. We also evaluated interaction terms between trial arm assignment and predictors to assess effects that may be introduced by the randomization. Predictors in the final logistic regression model were significant at the P < .05 level. Logistic regression assumption of little or no multicollinearity among the independent variables was verified in the final models. All analyses were performed with Stata v16 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

There were a total of 1,787 parent-child dyads enrolled in the H2O I and II during the study period; 1,320 parents (74%) completed the ACE questionnaire and were included the analysis. Included parents were primarily female and employed, as well as educated beyond high school (Table 1). Overall, 64% reported one or more ACEs (range 0 to 9); 45% reported 1to 3, and 19% reported 4 or more ACEs. The most commonly reported ACEs were divorce (n = 573, 43%), exposure to alcoholism (n = 306, 23%), and exposure to mental illness (n = 281, 21%; Figure 1). Parents had a mean BRS score of 3.97 (range 1.17-5.00), with the distribution shown in Figure 2.

Of the 1,320 included patients, the average length of stay was 2.5 days, and 82% of hospitalizations were caused by acute medical issues (eg, bronchiolitis). A total of 211 children experienced a reutilization event within 30 days of discharge. In bivariate analysis, children with parents with 4 or more ACEs had a 2.02-times (95% CI 1.35-3.02) higher odds of experiencing a reutilization event than did those with parents reporting no ACEs. Parents with higher resilience scores had children with a lower odds of reutilization (odds ratio [OR] 0.77 95% CI 0.63-0.95).

In addition to our a priori variables, parental education, employment, and insurance met our significance threshold for inclusion in the multivariable model. The ACE-by-resilience interaction term was not significant and not included in the model. Similarly, there was no significant interaction between ACE and resilience and H2O treatment arm; the interaction terms were not included in the final adjusted model, but treatment arm assignment was kept as a covariate. A total of 1,292 children, out of the 1,320 respondents, remained in the final multivariable model; the excluded 28 had incomplete covariate data but were not otherwise different. In this final adjusted model, children with parents reporting 4 or more ACEs had a 1.69-times (95% CI 1.11-2.60) greater odds of reutilization than did those with parents reporting no ACEs (Table 2). Resilience failed to reach statistical significance in the adjusted model (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.70-1.07).

DISCUSSION

We found that high-risk parents (4 or more ACEs) had children with an increased odds of healthcare reutilization, suggesting intergenerational effects of ACEs. We did not find a similar effect relating to parental resilience. We also did not find an interaction between parental ACEs and resilience, suggesting that a parent’s reported degree of resilience does not modify the effect of ACEs on reutilization risk.

Parental adversity may be a risk factor for a child’s unanticipated reutilization. We previously demonstrated that parents with 4 or more ACEs have more coping difficulty than a parent with no ACEs after a child’s hospitalization.11 It is possible that parents with high adversity may have poorer coping mechanisms when dealing with a stressful situation, such as a child’s hospitalization. This may have resulted in inequitable outcomes (eg, increased reutilization) for their children. Other studies have confirmed such an intergenerational effect of adversity, linking a parent’s ACEs with poor developmental, behavioral, and health outcomes in their children.6,22,23 O’Malley et al showed an association of parental ACEs to current adversities,24 such as insurance or housing concerns, that affect the entirety of the household, including children. In short, it appears that parental ACEs may be a compelling predictor of current childhood adversity.

Resilience buffers the negative effects of ACEs; however, we did not find significant associations between resilience and reutilization or an interaction between ACEs and resilience. The factors that may contribute to reutilization are complex. In our previous work, parental resilience was associated with coping difficulty after discharge; but again, did not interact with parental ACEs.11 Here, we suggest that while resilience may buffer the negative effects of ACEs, that buffering may not affect the likelihood of reutilization. It is also possible that the BRS tool is of less relevance on how one handles the stress of a child’s hospitalization. While the BRS is one measure of resilience, there are many other relevant constructs to resilience, such as connection to social supports, that also may also contribute to risk of reutilization.25

Reducing the stress of a hospitalization itself and promoting a safe transition from hospital to home is critical to improving child health outcomes. Our data here, and in our previous work, demonstrate that a history of adversity and one’s current coping ability may drive a parent’s response to a child’s hospitalization and affect their capacity to care for that child after hospital discharge.11 Additional in-hospital supports like child life, behavioral health, or pastoral care could reduce the stress of the hospitalization while also building positive coping mechanisms.26-29 A meta-analysis demonstrated that such coping interventions can help alleviate the stress of a hospitalization.30 Hill et al demonstrated successful stress reduction in parents of hospitalized children using a “Coping Kit for Parents.”31 Further studies are warranted to understand which interventions are most effective for children and families and whether they could be more effectively deployed if the inpatient team knew more about parental ACEs.

Screening for parental ACEs could help to identify patients at highest risk for a poor transition to home. Therefore, screening for parental adversity in clinical settings, including inpatient settings, may be relevant and valuable.32 Additionally, by recognizing the high prevalence of ACEs in an inpatient setting, hospitals and healthcare organizations could be motivated to develop and enact trauma-informed approaches. A trauma-informed care approach recognizes the intersection of trauma with health and social problems. With this recognition, care teams can more sensitively address the trauma as they provide relevant services.33 Trauma-informed care is a secondary public health prevention approach that would help team members identify the prevalence and effects of trauma via screening, recognize the signs of a maladaptive response to stress, and respond by integrating awareness of trauma into practice management.28,34 Both the National Academy of Medicine and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality have called for such a trauma-informed approach in primary care.35 In response, many healthcare organizations have developed trauma-informed practices to better address the needs of the populations they serve. For example, provider training on this approach has led to improved rapport in patient-provider relationships.36

Although ACE awareness is a component of trauma-informed care, there are still limitations of the original ACE questionnaire developed by Felitti et al. The existing tool is not inclusive of all adversities a parent or child may face. Moreover, its focus is on past exposures and experiences and not current health-related social needs (eg, food insecurity) which have known linkages with a range of health outcomes and health disparities.37 Additionally, the original ACE questionnaire was created as a population level tool and not as a screening tool. If used as a screening tool, providers may view the questions as too sensitive to ask, and parents may have difficulty responding to and understanding the relevance to their child’s care. Therefore, we suggest that more evidence is required to understand how to best adapt ACE questions into a screening processes that may be implemented in a medical setting.

More evidence is also needed to determine when and where such screening may be most useful. A primary care provider would be best equipped to screen caregivers for ACEs given their established relationship with parents and patients. Given the potential relevance of such information for inpatient care provision, information could then flow from primary care to the inpatient team. However, because not all patients have established primary care providers and only 4% of pediatricians screen for ACEs,38 it is important for inpatient medical teams to understand their role in identifying and addressing ACEs during hospital stays. Development of a screening tool, with input from all stakeholders—including parents—that is valid and feasible for use in a pediatric inpatient setting would be an important step forward. This tool should be paired with training in how to discuss these topics in a trauma-informed, nonjudgmental, empathic manner. We see this as a way in which providers can more effectively elicit an accurate response while simultaneously educating parents on the relevance of such sensitive topics during an acute hospital stay. We also recommend that screening should always be paired with response capabilities that connect those who screen positive with resources that could help them to navigate the stress experienced during and after a child’s hospitalization. Furthermore, communication with primary care providers about parents that screen positive should be integrated into the transition process.

This work has several limitations. First, our study was a part of randomized controlled trials conducted in one academic setting, which thereby limits generalizability. For example, we limited our cohort to those who were English-speaking patients only. This may bias our results because respondents with limited English proficiency may have different risk profiles than their English-speaking peers. In addition, the administration of the both the ACE and resilience questionnaires occurred during an acutely stressful period, which may influence how a parent responds to these questions. Also, both of the surveys are self-reported by parents, which may be susceptible to memory and response biases. Relatedly, we had a high number of nonrespondents, particularly to the ACE questionnaire. Our results are therefore only relevant to those who chose to respond and cannot be applied to nonrespondents. Further work assessing why one does or does not respond to such sensitive questions is an important area for future inquiry. Lastly, our cohort had limited medical complexity; future studies may consider links between parental ACEs (and resilience) and morbidity experienced by children with medical complexity.

CONCLUSION

Parents history of adversity is linked to their children’s unanticipated healthcare reutilization after a hospital discharge. Screening for parental stressors during a hospitalization may be an important first step to connecting parents and children to evidence-based interventions capable of mitigating the stress of hospitalization and promoting better, more seamless transitions from hospital to home.

Acknowledgments

Group Members: The following H2O members are nonauthor contributors: JoAnne Bachus, BSN, RN; Monica Borell, BSN, RN; Lenisa V Chang, MA, PhD; Patricia Crawford, RN; Sarah Ferris, BA; Jennifer Gold, BSN, RN; Judy A Heilman, BSN, RN; Jane C Khoury, PhD; Pierce Kuhnell, MS; Karen Lawley, BSN, RN; Margo Moore, MS, BSN, RN; Lynne O’Donnell, BSN, RN; Sarah Riddle, MD; Susan N Sherman, DPA; Angela M Statile, MD, MEd; Karen P Sullivan, BSN, RN; Heather Tubbs-Cooley, PhD, RN; Susan Wade-Murphy, MSN, RN; and Christine M White, MD, MAT.

The authors also thank David Keller, MD, for his guidance on the study.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial relationships or conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding Source

Supported by funds from the Academic Pediatric Young Investigator Award (Dr A Shah) and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award (IHS-1306-0081, to Dr K Auger, Dr S Shah, Dr H Sucharew, Dr J Simmons), the National Institutes of Health (1K23AI112916, to Dr AF Beck), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K12HS026393-01, to Dr A Shah, K08-HS024735- 01A1, to Dr K Auger). Dr J Haney received Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship funding through the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Disclaimer

All statements in this report, including findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, its Board of Governors, or the Methodology Committee.

Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, include exposure to abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction (eg, having a parent who is mentally ill) as a child.1 Exposure to ACEs affects health into adulthood, with a dose-response relationship between ACEs and a range of comorbidities.1 Adults with 6 or more ACEs have a 20-year shorter life expectancy than do those with no ACEs.1 Still, ACEs are static; once experienced, that experience cannot be undone. However, resilience, or positive adaptation in the context of adversity, can be protective, buffering the negative effects of ACEs.2,3 Protective factors that promote resilience include social capital, such as positive relationships with caregivers and peers.3

With their clear link to health outcomes across the life-course, there is a movement for pediatricians to screen children for ACEs4 and to develop strategies that promote resilience in children, parents, and families. However, screening a child for adversity has challenges because younger children may not have experienced an adverse exposure, or they may be unable to voice their experiences. Studies have demonstrated that parental adversity, or ACEs, may be a marker for childhood adversity.5,6 Biological models also support this potential intergenerational effect of ACEs. Chronic exposure to stress, including ACEs, results in elevated cortisol via a dysregulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which results in chronic inflammation.7 This “toxic stress” is prolonged, severe in intensity, and can lead to epigenetic changes that may be passed on to the next generation.8,9

Hospitalization of an ill child, and the transition to home after that hospitalization, is a stressful event for children and families.10 This stress may be relevant to parents that have a history of a high rate of ACEs or a current low degree of resilience. Our previous work demonstrated that, in the inpatient setting, parents with high ACEs (≥4) or low resilience have increased coping difficulty 14 days after their child’s hospital discharge.11 Our objective here was to evaluate whether a parent’s ACEs and/or resilience would also be associated with that child’s likelihood of reutilization. We hypothesized that more parental ACEs and/or lower parental resilience would be associated with revisits the emergency room, urgent care, or hospital readmissions.

METHODS

Participants and Study Design

We conducted a prospective cohort study of parents of hospitalized children recruited from the “Hospital-to-Home Outcomes” Studies (H2O I and H2O II).12,13 H2O I and II were prospective, single-center, randomized controlled trials designed to determine the effectiveness of either a nurse-led transitional home visit (H2O I) or telephone call (H2O II) on 30-day unplanned healthcare reutilization. The trials and this study were approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Institutional Review Board. All parents provided written informed consent.

Details of H2O I and II recruitment and design have been described previously.12,13 Briefly, children were eligible for inclusion in either study if they were admitted to our institution’s general Hospital Medicine or the Hospital Medicine Complex Care Services; for H2O I, children hospitalized on the Neurology and Neurosurgery services were also eligible.12,13 Patients were excluded if they were discharged to a residential facility, if they lived outside the home healthcare nurse service area, if they were eligible for skilled home healthcare services (eg, intravenous antibiotics), or if the participating caregiver was non-English speaking.12,13 In H2O I, families were randomized either to receive a single nurse home visit within 96 hours of discharge or standard of care. In H2O II, families enrolled were randomized to receive a telephone call by a nurse within 96 hours of discharge or standard of care. As we have previously published, randomization in both trials successfully balanced the intervention and control arms with respect to key demographic characteristics.12,13 For the analyses presented here, we focused on a subset of caregivers 18 years and older whose children were enrolled in either H2O I or II between August 2015 and October 2016. In both H2O trials, face-to-face and paper-based questionnaires were completed by parents during the index hospitalization.

Outcome and Predictors

Our primary outcome was unanticipated healthcare reutilization defined as return to the emergency room, urgent care, or unplanned readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge, consistent with the H2O trials. This was measured using the primary institution’s administrative data supplemented by a utilization database shared across regional hospitals.14 Readmissions were identified as “unplanned” using a previously validated algorithm,15 and treated as a dichotomous yes/no variable.

Our primary predictors were parental ACEs and resilience (see Appendix Tables). The ACE questionnaire addresses abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction in the first 18 years of life.1 It is composed of 10 questions, each with a yes/no response.1 We defined parents as low (ACE 0), moderate (ACE 1-3), or high (ACE ≥4) risk a priori because previous literature has described poor outcomes in adults with 4 or more ACEs.16

Given the sensitive nature of the questions, respondents independently completed the ACE questionnaire on paper instead of via the face-to-face survey. Respondents returned the completed questionnaire to the research assistant in a sealed envelope. All families received educational information on relevant hospital and community-based resources (eg, social work).

Parental resilience was measured using the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS). The BRS is 6 items, each on a 5-point Likert scale. Responses were averaged, providing a total score of 1-5; higher scores are representative of higher resilience.17 We treated the BRS score as a continuous variable. BRS has been used in clinical settings; it has demonstrated positive correlation with social support and negative correlation with fatigue.17 Parents answered BRS questions during the index pediatric hospitalization in a face-to-face interview.

Parent and Child Characteristics

Parent and child sociodemographic variables were also obtained during the face-to-face interview. Parental variables included age, gender, educational attainment, household income, employment status, and financial and social strain.11 Educational attainment was analyzed in 2 categories—high school or less vs more than high school—because most discharge instructions are written at a high school reading level.18 Parents reported their annual household income in the following categories: <$15,000; $15,000-$29,999; $30,000-$44,999; $45,000-$59,999; $60,000-$89,999; $90,000-$119,999; ≥$120,000. Employment was dichotomized as not employed/student vs any employment. Financial and social strain were assessed using a series of 9 previously described questions.19 These questions assessed, via self-report, a family’s ability to make ends meet, ability to pay rent/mortgage or utilities, need to move in with others because of financial reasons, and ability to borrow money if needed, as well as home ownership and parental marital status.15,19 Strain questions were all dichotomous (yes/no, single/not single). A composite variable was then constructed that categorized those reporting no strain items, 1 to 2 items, 3 to 4 items, and 5 or more items.20

Child variables included race, ethnicity, age, primary care access,21 payer, and H2O treatment arm. Race categories were white/Caucasian, black/African American, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, and other; ethnicity categories were Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic/Latino, and unknown. Given relatively low numbers of children reported to be Hispanic/Latino, we combined race and ethnicity into a single variable, categorized as non-Hispanic/white, non-Hispanic/black, and multiracial/Hispanic/other. Primary care access was assessed using the access subscale to the Parent’s Perception of Primary Care questionnaire. This includes assessment of a family’s ability to travel to their doctor, to see their doctor for routine or sick care, and to get help or advice on evenings or weekends. Scores were categorized as always adequate, almost always adequate, or sometimes/never adequate.21 Payer was dichotomized to private or public/self-pay.

Statistical Analyses

We examined the distribution of outcomes, predictors, and covariates. We compared sociodemographic characteristics of those respondents and nonrespondents to the ACE screen using the chi-square test for categorical variables or the t test for continuous variables. We used logistic regression to assess for associations between the independent variables of interest and reutilization, adjusting for potential confounders. To build our adjusted, multivariable model, we decided a priori to include child race/ethnicity, primary care access, financial and social strain, and trial treatment arm. We treated the H2O I control group as the referent group. Other covariates considered for inclusion were caregiver education, household income, employment, and payer. These were included in multivariable models if bivariate associations were significant at the P < .1 level. We assessed an ACE-by-resilience interaction term because we hypothesized that those with more ACEs and lower resilience may have more reutilization outcomes than parents with fewer ACEs and higher resilience. We also evaluated interaction terms between trial arm assignment and predictors to assess effects that may be introduced by the randomization. Predictors in the final logistic regression model were significant at the P < .05 level. Logistic regression assumption of little or no multicollinearity among the independent variables was verified in the final models. All analyses were performed with Stata v16 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

There were a total of 1,787 parent-child dyads enrolled in the H2O I and II during the study period; 1,320 parents (74%) completed the ACE questionnaire and were included the analysis. Included parents were primarily female and employed, as well as educated beyond high school (Table 1). Overall, 64% reported one or more ACEs (range 0 to 9); 45% reported 1to 3, and 19% reported 4 or more ACEs. The most commonly reported ACEs were divorce (n = 573, 43%), exposure to alcoholism (n = 306, 23%), and exposure to mental illness (n = 281, 21%; Figure 1). Parents had a mean BRS score of 3.97 (range 1.17-5.00), with the distribution shown in Figure 2.

Of the 1,320 included patients, the average length of stay was 2.5 days, and 82% of hospitalizations were caused by acute medical issues (eg, bronchiolitis). A total of 211 children experienced a reutilization event within 30 days of discharge. In bivariate analysis, children with parents with 4 or more ACEs had a 2.02-times (95% CI 1.35-3.02) higher odds of experiencing a reutilization event than did those with parents reporting no ACEs. Parents with higher resilience scores had children with a lower odds of reutilization (odds ratio [OR] 0.77 95% CI 0.63-0.95).

In addition to our a priori variables, parental education, employment, and insurance met our significance threshold for inclusion in the multivariable model. The ACE-by-resilience interaction term was not significant and not included in the model. Similarly, there was no significant interaction between ACE and resilience and H2O treatment arm; the interaction terms were not included in the final adjusted model, but treatment arm assignment was kept as a covariate. A total of 1,292 children, out of the 1,320 respondents, remained in the final multivariable model; the excluded 28 had incomplete covariate data but were not otherwise different. In this final adjusted model, children with parents reporting 4 or more ACEs had a 1.69-times (95% CI 1.11-2.60) greater odds of reutilization than did those with parents reporting no ACEs (Table 2). Resilience failed to reach statistical significance in the adjusted model (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.70-1.07).

DISCUSSION

We found that high-risk parents (4 or more ACEs) had children with an increased odds of healthcare reutilization, suggesting intergenerational effects of ACEs. We did not find a similar effect relating to parental resilience. We also did not find an interaction between parental ACEs and resilience, suggesting that a parent’s reported degree of resilience does not modify the effect of ACEs on reutilization risk.

Parental adversity may be a risk factor for a child’s unanticipated reutilization. We previously demonstrated that parents with 4 or more ACEs have more coping difficulty than a parent with no ACEs after a child’s hospitalization.11 It is possible that parents with high adversity may have poorer coping mechanisms when dealing with a stressful situation, such as a child’s hospitalization. This may have resulted in inequitable outcomes (eg, increased reutilization) for their children. Other studies have confirmed such an intergenerational effect of adversity, linking a parent’s ACEs with poor developmental, behavioral, and health outcomes in their children.6,22,23 O’Malley et al showed an association of parental ACEs to current adversities,24 such as insurance or housing concerns, that affect the entirety of the household, including children. In short, it appears that parental ACEs may be a compelling predictor of current childhood adversity.

Resilience buffers the negative effects of ACEs; however, we did not find significant associations between resilience and reutilization or an interaction between ACEs and resilience. The factors that may contribute to reutilization are complex. In our previous work, parental resilience was associated with coping difficulty after discharge; but again, did not interact with parental ACEs.11 Here, we suggest that while resilience may buffer the negative effects of ACEs, that buffering may not affect the likelihood of reutilization. It is also possible that the BRS tool is of less relevance on how one handles the stress of a child’s hospitalization. While the BRS is one measure of resilience, there are many other relevant constructs to resilience, such as connection to social supports, that also may also contribute to risk of reutilization.25

Reducing the stress of a hospitalization itself and promoting a safe transition from hospital to home is critical to improving child health outcomes. Our data here, and in our previous work, demonstrate that a history of adversity and one’s current coping ability may drive a parent’s response to a child’s hospitalization and affect their capacity to care for that child after hospital discharge.11 Additional in-hospital supports like child life, behavioral health, or pastoral care could reduce the stress of the hospitalization while also building positive coping mechanisms.26-29 A meta-analysis demonstrated that such coping interventions can help alleviate the stress of a hospitalization.30 Hill et al demonstrated successful stress reduction in parents of hospitalized children using a “Coping Kit for Parents.”31 Further studies are warranted to understand which interventions are most effective for children and families and whether they could be more effectively deployed if the inpatient team knew more about parental ACEs.

Screening for parental ACEs could help to identify patients at highest risk for a poor transition to home. Therefore, screening for parental adversity in clinical settings, including inpatient settings, may be relevant and valuable.32 Additionally, by recognizing the high prevalence of ACEs in an inpatient setting, hospitals and healthcare organizations could be motivated to develop and enact trauma-informed approaches. A trauma-informed care approach recognizes the intersection of trauma with health and social problems. With this recognition, care teams can more sensitively address the trauma as they provide relevant services.33 Trauma-informed care is a secondary public health prevention approach that would help team members identify the prevalence and effects of trauma via screening, recognize the signs of a maladaptive response to stress, and respond by integrating awareness of trauma into practice management.28,34 Both the National Academy of Medicine and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality have called for such a trauma-informed approach in primary care.35 In response, many healthcare organizations have developed trauma-informed practices to better address the needs of the populations they serve. For example, provider training on this approach has led to improved rapport in patient-provider relationships.36

Although ACE awareness is a component of trauma-informed care, there are still limitations of the original ACE questionnaire developed by Felitti et al. The existing tool is not inclusive of all adversities a parent or child may face. Moreover, its focus is on past exposures and experiences and not current health-related social needs (eg, food insecurity) which have known linkages with a range of health outcomes and health disparities.37 Additionally, the original ACE questionnaire was created as a population level tool and not as a screening tool. If used as a screening tool, providers may view the questions as too sensitive to ask, and parents may have difficulty responding to and understanding the relevance to their child’s care. Therefore, we suggest that more evidence is required to understand how to best adapt ACE questions into a screening processes that may be implemented in a medical setting.

More evidence is also needed to determine when and where such screening may be most useful. A primary care provider would be best equipped to screen caregivers for ACEs given their established relationship with parents and patients. Given the potential relevance of such information for inpatient care provision, information could then flow from primary care to the inpatient team. However, because not all patients have established primary care providers and only 4% of pediatricians screen for ACEs,38 it is important for inpatient medical teams to understand their role in identifying and addressing ACEs during hospital stays. Development of a screening tool, with input from all stakeholders—including parents—that is valid and feasible for use in a pediatric inpatient setting would be an important step forward. This tool should be paired with training in how to discuss these topics in a trauma-informed, nonjudgmental, empathic manner. We see this as a way in which providers can more effectively elicit an accurate response while simultaneously educating parents on the relevance of such sensitive topics during an acute hospital stay. We also recommend that screening should always be paired with response capabilities that connect those who screen positive with resources that could help them to navigate the stress experienced during and after a child’s hospitalization. Furthermore, communication with primary care providers about parents that screen positive should be integrated into the transition process.

This work has several limitations. First, our study was a part of randomized controlled trials conducted in one academic setting, which thereby limits generalizability. For example, we limited our cohort to those who were English-speaking patients only. This may bias our results because respondents with limited English proficiency may have different risk profiles than their English-speaking peers. In addition, the administration of the both the ACE and resilience questionnaires occurred during an acutely stressful period, which may influence how a parent responds to these questions. Also, both of the surveys are self-reported by parents, which may be susceptible to memory and response biases. Relatedly, we had a high number of nonrespondents, particularly to the ACE questionnaire. Our results are therefore only relevant to those who chose to respond and cannot be applied to nonrespondents. Further work assessing why one does or does not respond to such sensitive questions is an important area for future inquiry. Lastly, our cohort had limited medical complexity; future studies may consider links between parental ACEs (and resilience) and morbidity experienced by children with medical complexity.

CONCLUSION

Parents history of adversity is linked to their children’s unanticipated healthcare reutilization after a hospital discharge. Screening for parental stressors during a hospitalization may be an important first step to connecting parents and children to evidence-based interventions capable of mitigating the stress of hospitalization and promoting better, more seamless transitions from hospital to home.

Acknowledgments

Group Members: The following H2O members are nonauthor contributors: JoAnne Bachus, BSN, RN; Monica Borell, BSN, RN; Lenisa V Chang, MA, PhD; Patricia Crawford, RN; Sarah Ferris, BA; Jennifer Gold, BSN, RN; Judy A Heilman, BSN, RN; Jane C Khoury, PhD; Pierce Kuhnell, MS; Karen Lawley, BSN, RN; Margo Moore, MS, BSN, RN; Lynne O’Donnell, BSN, RN; Sarah Riddle, MD; Susan N Sherman, DPA; Angela M Statile, MD, MEd; Karen P Sullivan, BSN, RN; Heather Tubbs-Cooley, PhD, RN; Susan Wade-Murphy, MSN, RN; and Christine M White, MD, MAT.

The authors also thank David Keller, MD, for his guidance on the study.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial relationships or conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding Source

Supported by funds from the Academic Pediatric Young Investigator Award (Dr A Shah) and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award (IHS-1306-0081, to Dr K Auger, Dr S Shah, Dr H Sucharew, Dr J Simmons), the National Institutes of Health (1K23AI112916, to Dr AF Beck), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K12HS026393-01, to Dr A Shah, K08-HS024735- 01A1, to Dr K Auger). Dr J Haney received Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship funding through the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Disclaimer

All statements in this report, including findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, its Board of Governors, or the Methodology Committee.

1. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8.

2. Bethell CD, Newacheck P, Hawes E, Halfon N. Adverse childhood experiences: assessing the impact on health and school engagement and the mitigating role of resilience. Health Aff. 2014;33(12):2106-2115. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0914.

3. Masten AS. Ordinary Magic. Resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):227-238. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227.

4. Garner AS, Shonkoff JP, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of C, et al. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e224-231. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2662.

5. Randell KA, O’Malley D, Dowd MD. Association of parental adverse childhood experiences and current child adversity. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(8):786-787. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0269.

6. Le-Scherban F, Wang X, Boyle-Steed KH, Pachter LM. Intergenerational associations of parent adverse childhood experiences and child health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20174274. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4274.

7. Johnson SB, Riley AW, Granger DA, Riis J. The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):319-327. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0469.

8. Roth TL, Lubin FD, Funk AJ, Sweatt JD. Lasting epigenetic influence of early-life adversity on the BDNF gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):760-769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.028.

9. Garner AS, Forkey H, Szilagyi M. Translating developmental science to address childhood adversity. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(5):493-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.05.010.

10. Weiss M, Johnson NL, Malin S, Jerofke T, Lang C, Sherburne E. Readiness for discharge in parents of hospitalized children. J Pediatr Nurs. 2008;23(4):282-295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2007.10.005.

11. Shah AN, Beck AF, Sucharew HJ, et al. Parental adverse childhood experiences and resilience on coping after discharge. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172127. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2127.

12. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: The Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) Trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3919.

13. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482.

14. TheHealthCollaborative. Healthbridge analytics. http://healthcollab.org/hbanalytics/. Accessed August 11, 2017.

15. Auger K, Mueller E, Weinberg S, et al. A validated method for identifying unplanned pediatric readmission. J Pediatr. 2016;170:105-12.e122. https://doi.org10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.051.

16. Felitti VJ. Belastungen in der Kindheit und Gesundheit im Erwachsenenalter: die Verwandlung von Gold in Blei [The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult health: turning gold into lead]. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2002;48(4):359-369. https://doi.org/10.13109/zptm.2002.48.4.359.

17. Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(3):194-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972.