User login

Recreational cannabinoid use: The hazards behind the “high”

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Screen all patients for use of addiction-prone substances. A

› Screen cannabis users with a validated secondary screen for problematic use. A

› Counsel patients that there is no evidence that use of recreational cannabis is safe; advise them that it can cause numerous physical, psychomotor, cognitive, and psychiatric effects. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Approximately 156 million Americans (49% of the population) have tried cannabis.1 About 5.7 million people ages 12 years and older use it daily or almost daily, a number that has nearly doubled since 2006.2 There are 6600 new users in the United States every day,2 and almost half of all high school students will have tried it by graduation.3

There is limited evidence that cannabis may have medical benefit in some circumstances.4 (See “Medical marijuana: A treatment worth trying?” J Fam Pract. 2016;65:178-185 or http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/106836/medical-marijuana-treatment-worth-trying.) As a result, it is now legal for medical purposes in 25 states. Recreational use by adults is also legal in 4 states and the District of Columbia.5 The US Food and Drug Administration, however, has reaffirmed its stance that marijuana is a Schedule I drug on the basis of its “high potential for abuse” and the absence of “currently accepted medical uses.”6

The effects of legalizing the medical and recreational use of cannabis for individuals—and society as a whole—are uncertain. Debate is ongoing about the risks, benefits, and rights of individuals. Some argue it is safer than alcohol or that criminalization has been ineffective and even harmful. Others make the case for personal liberty and autonomy. Still, others are convinced legalization is a misdirected experiment that will result in diverse adverse outcomes. Regardless, it is important that primary care providers understand the ramifications of marijuana use. This evidence-based narrative highlights major negative consequences of non-medical cannabinoid use.

Potential adverse consequences of cannabis use

Although the potential adverse consequences are vast, the literature on this subject is limited for various reasons:

- Many studies are observational with a small sample size.

- Most studies examine smoked cannabis—not other routes of delivery.

- When smoked, the dose, frequency, duration, and smoking technique are variable.

- The quantity of Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive component in cannabis, is variable. (For more on the chemical properties of the marijuana plant, see “Cannabinoids: A diverse group of chemicals.”7)

- Most studies do not examine medical users, who are expected to use less cannabis or lower doses of THC.

- There are confounding effects of other drugs, notably tobacco, which is used by up to 90% of cannabis users.8

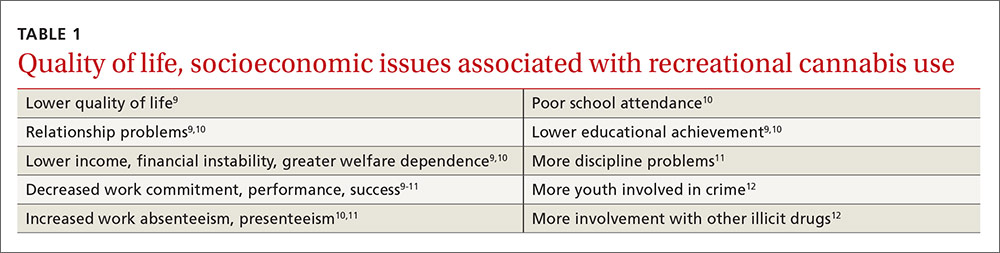

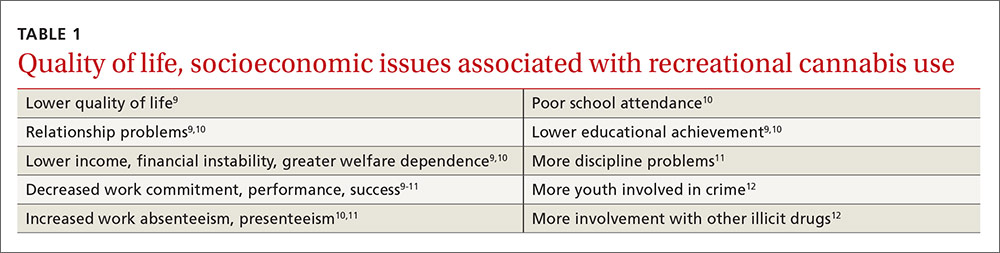

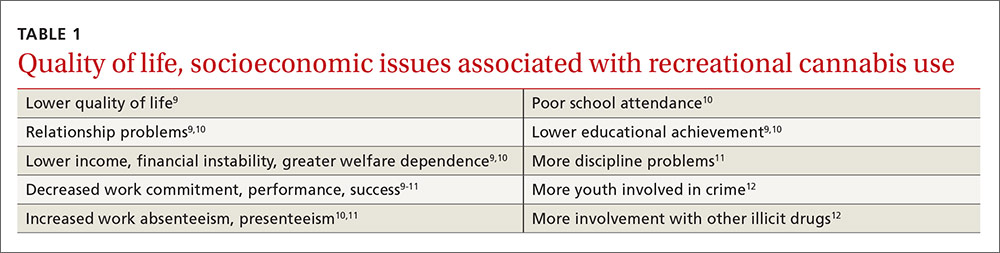

Lower quality of life. In general, regular non-medical cannabis use is associated with a lower quality of life and poorer socioeconomic outcomes (TABLE 1).9-12 Physical and mental health is ranked lower by heavy users as compared to extremely low users.9 Some who attempt butane extraction of THC from the plant have experienced explosions and severe burns.13

Studies regarding cannabis use and weight are conflicting. Appetite and weight may increase initially, and young adults who increase their use of the drug are more likely to find themselves on an increasing obesity trajectory.14 However, in an observational study of nearly 11,000 participants ages 20 to 59 years, cannabis users had a lower body mass index, better lipid parameters, and were less likely to have diabetes than non-using counterparts.15

Elevated rates of MI. Chronic effects may include oral health problems,16 gynecomastia, and changes in sexual function.17 Elevated rates of myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, limb arteritis, and stroke have been observed.18 Synthetic cannabinoids have been associated with heart attacks and acute renal injury in youth;19,20 however, plant-based marijuana does not affect the kidneys. In addition, high doses of plant-based marijuana can result in cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, characterized by cyclic vomiting and compulsive bathing that resolves with cessation of the drug.21

No major pulmonary effects. Interestingly, cannabis does not appear to have major negative pulmonary effects. Acutely, smoking marijuana causes bronchodilation.22 Chronic, low-level use over 20 years is associated with an increase in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), but this upward trend diminishes and may reverse in high-level users.23 Although higher lung volumes are observed, cannabis does not appear to contribute to the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but can cause chronic bronchitis that resolves with smoking cessation.22 Chronic use has also been tied to airway infection. Lastly, fungal growth has been found on marijuana plants, which is concerning because of the potential to expose people to Aspergillus.22,24

Cannabis and cancer? The jury is out. Cannabis contains at least 33 carcinogens25 and may be contaminated with pesticides,26 but research about its relationship with cancer is incomplete. Although smoking results in histopathologic changes of the bronchial mucosa, evidence of lung cancer is mixed.22,25,27 Some studies have suggested associations with cancers of the brain, testis, prostate, and cervix,25,27 as well as certain rare cancers in children due to parental exposure.25,27

There are conflicting data about associations with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma,25,27,28 bladder cancer,25,29 and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.25,30 Some studies suggest marijuana offers protection against certain types of cancer. In fact, it appears that some cannabinoids found in marijuana, such as cannabidiol (CBD), may be antineoplastic.31 The potential oncogenic effects of edible and topical cannabinoid products have not been investigated.

Use linked to car accidents. More recent work indicates cannabis use is associated with injuries in motor vehicle,32 non-traffic,33 and workplace34 settings. In fact, a meta-analysis found a near-doubling of motor vehicle accidents with recent use.32 Risk is dose-dependent and heightened with alcohol.35-37 Psychomotor impairment persists for at least 6 hours after smoking cannabis,38 at least 10 hours after ingesting it,37 and may last up to 24 hours, as indicated by a study involving pilots using a flight simulator.39

In contrast to alcohol, there is a greater decrement in routine vs complex driving tasks in experimental studies.35,36 Behavioral strategies, like driving slowly, are employed to compensate for impairment, but the ability to do so is lost with alcohol co-ingestion.35 Importantly, individuals using marijuana may not recognize the presence or extent of the impairment they are experiencing,37,39 placing themselves and others in danger.

Data are insufficient to ascribe to marijuana an increase in overall mortality,40 and there have been no reported overdose deaths from respiratory depression. However, a few deaths and a greater number of hospitalizations, due mainly to central nervous system effects including agitation, depression, coma, delirium, and toxic psychosis, have been attributed to the use of synthetic cannabinoids.20

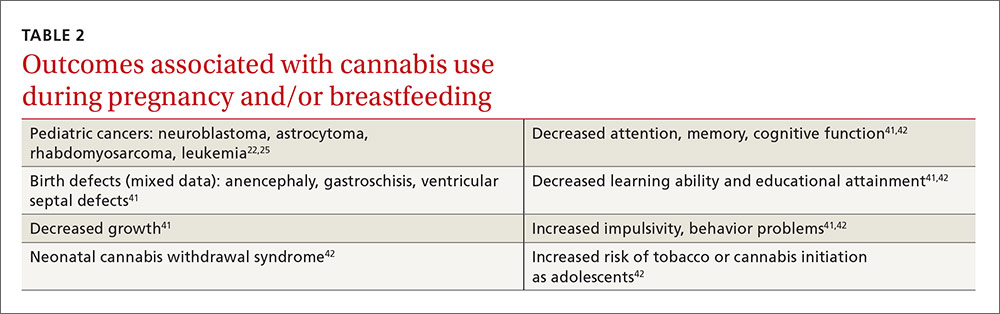

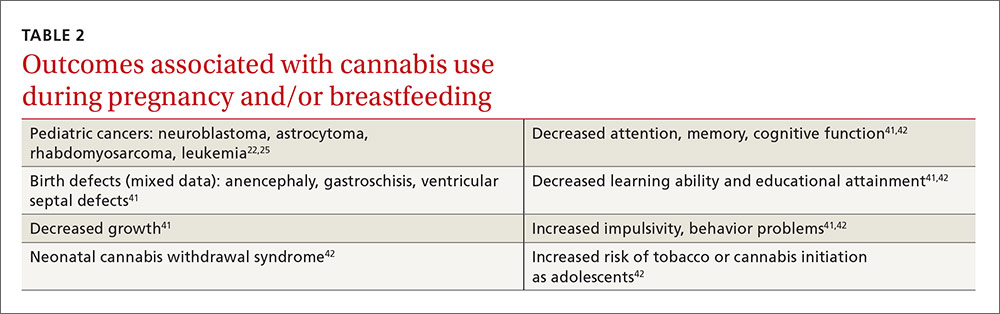

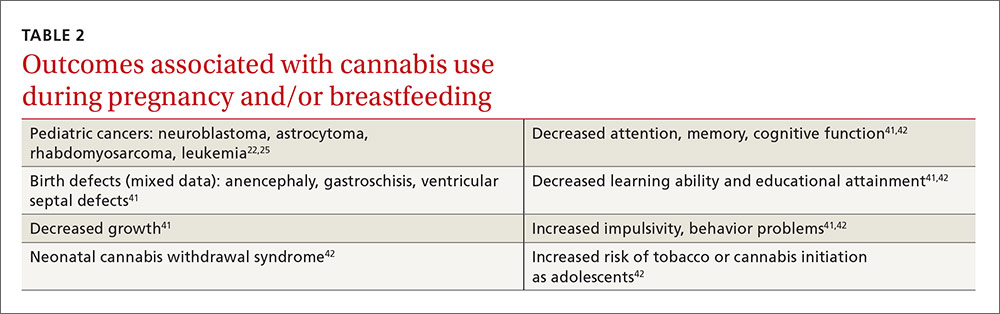

Cannabis use can pose a risk to the fetus. About 5% of pregnant women report recent marijuana use2 for recreational or medical reasons (eg, morning sickness), and there is concern about its effects on the developing fetus. Certain rare pediatric cancers22,25 and birth defects41 have been reported with cannabis use (TABLE 222,25,41,42). Neonatal withdrawal is minor, if present at all.42 Moderate evidence indicates prenatal and breastfeeding exposure can result in multiple developmental problems, as well as an increased likelihood of initiating tobacco and marijuana use as teens.41,42

Cognitive effects of cannabis are a concern. The central nervous system is not fully myelinated until the age of 18, and complete maturation continues beyond that. Due to neuroplasticity, life experiences and exogenous agents may result in further changes. Cannabis produces changes in brain structure and function that are evident on neuroimaging.43 Although accidental pediatric intoxication is alarming, negative consequences are likely to be of short duration.

Regular use by youth, on the other hand, negatively affects cognition and delays brain maturation, especially for younger initiates.9,38,44 With abstinence, deficits tend to normalize, but they may last indefinitely among young people who continue to use marijuana.44

Dyscognition is less severe and is more likely to resolve with abstinence in adults,44 which may tip the scale for adults weighing whether to use cannabis for a medical purpose.45 Keep in mind that individuals may not be aware of their cognitive deficits,46 even though nearly all domains (from basic motor coordination to more complex executive function tasks, such as the ability to control emotions and behavior) are affected.44 A possible exception may be improvement in attention with acute use in daily, but not occasional, users.44 Highly focused attention, however, is not always beneficial if it delays redirection toward a new urgent stimulus.

Mood benefit? Research suggests otherwise. The psychiatric effects of cannabis are not fully understood. Users may claim mood benefit, but research suggests marijuana prompts the development or worsening of anxiety, depression, and suicidality.12,47 Violence, paranoia, and borderline personality features have also been associated with use.38,47 Amotivational syndrome, a disorder that includes apathy, callousness, and antisocial behavior, has been described, but the interplay between cannabis and motivation beyond recent use is unclear.48

Lifetime cannabis use is related to panic,49 yet correlational studies suggest both benefit and problems for individuals who use cannabis for posttraumatic stress disorder.50 It is now well established that marijuana use is an independent causal risk factor for the development of psychosis, particularly in vulnerable youth, and that it worsens schizophrenia in those who suffer from it.51 Human experimental studies suggest this may be because the effect of THC is counteracted by CBD.52 Synthetic cannabinoids are even more potent anxiogenic and psychogenic agents than plant-based marijuana.19,20

Cannabis Use Disorder

About 9% of those who try cannabis develop Cannabis Use Disorder, which is characterized by continued use of the substance despite significant distress or impairment.53 Cannabis Use Disorder is essentially an addiction. Primary risk factors include male gender, younger age at marijuana initiation, and personal or family history of other substance or psychiatric problems.53

Although cannabis use often precedes use of other addiction-prone substances, it remains unclear if it is a “gateway” to the use of other illicit drugs.54 Marijuana withdrawal is relatively minor and is comparable to that for tobacco.55 While there are no known effective pharmacotherapies for discontinuing cannabis use, addiction therapy—including cognitive behavioral therapy and trigger management—is effective.56

SIDEBAR

Cannabinoids: A diverse group of chemicalsCannabis, the genus name for 3 species of marijuana plant (sativa, indica, ruderalis), has come to mean any psychoactive part of the plant and is used interchangeably with “marijuana.” There are at least 85 different cannabinoids in the native plant.7

Cannabinoids are a diverse group of chemicals that have activity at cannabinoid receptors. Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a partial agonist of the CB1 receptor, is the primary psychoactive component and is found in larger quantities in Cannabis sativa, which is preferred by non-medical users. Cannabidiol (CBD), a weak partial CB1 antagonist, exhibits few, if any, psychotropic properties and is more plentiful in Cannabis indica.

Synthetic cannabinioids are a heterogeneous group of manufactured drugs that are full CB1 agonists and that are more potent than THC, yet are often assumed to be safe by users. Typically, they are dissolved in solvents, sprayed onto inert plant materials, and marketed as herbal products like “K2” and “spice.”

So how should the evidence inform your care?

Screen all patients for use of cannabinoids and other addiction-prone substances.57 Follow any affirmative answers to your questions about cannabis use by asking about potential negative consequences of use. For example, ask patients:

- How often during the past 6 months did you find that you were unable to stop using cannabis once you started?

- How often during the past 6 months did you fail to do what was expected of you because of using cannabis? (For more questions, see the Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test available at: http://www.otago.ac.nz/nationaladdictioncentre/pdfs/cudit-r.pdf.)

Other validated screening tools include the Severity of Dependence Scale, the Cannabis Abuse Screening Test, and the Problematic Use of Marijuana.58

Counsel patients about possible adverse effects and inform them there is no evidence that recreational marijuana or synthetic cannabinoids can be used safely over time. Consider medical use requests only if there is a favorable risk/benefit balance, other recognized treatment options have been exhausted, and you have a strong understanding of the use of cannabis in the medical condition being considered.4

Since brief interventions using motivational interviewing to reduce or eliminate recreational use have not been found to be effective,59 referral to an addiction specialist may be indicated. If a diagnosis of cannabis use disorder is established, then abstinence from addiction-prone substances including marijuana, programs like Marijuana Anonymous (Available at: https://www.marijuana-anonymous.org/), and individualized addiction therapy scaled to the severity of the condition can be effective.56 Because psychiatric conditions frequently co-occur and complicate addiction,53 they should be screened for and managed, as well.

Drug testing. Cannabis Use Disorder has significant relapse potential.60 Abstinence and treatment adherence should be ascertained through regular follow-up that includes a clinical interview, exam, and body fluid drug testing. Point-of-care urine analysis for substances of potential addiction has limited utility. Definitive testing of urine with gas chromotography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) or liquid chromatography (LC/MS-MS) can eliminate THC false-positives and false-negatives that can occur with point-of-care urine immunoassays. In addition, GCMS and LC/MS-MS can identify synthetic cannabinoids; in-office immunoassays cannot.

If the patient relapses, subsequent medical care should be coordinated with an addiction specialist with the goal of helping the patient to abstain from cannabis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Wright, MD, FAAFP, 5325 Ridge Trail, Littleton, CO 80123; [email protected].

1. Pew Research Center. 6 facts about marijuana. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/14/6-facts-about-marijuana/. Accessed September 27, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. HHS Pub # (SMA) 14-4863. 2014. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2015.

3. Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future National Survey on Drug Use 1975-2015. Available at: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Accessed September 23, 2015.

4. Metts J, Wright S, Sundaram J, et al. Medical marijuana: a treatment worth trying? J Fam Pract. 2016;65:178-185.

5. Governing the states and localities. State marijuana laws map. Available at: http://www.governing.com/gov-data/state-marijuana-laws-map-medical-recreational.html. Accessed October 12, 2016.

6. US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug scheduling. Available at: https://www.dea.gov/druginfo/ds.shtml. Accessed October 12, 2016.

7. El-Alfy AT, Ivey K, Robinson K, et al. Antidepressant-like effect of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa L. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;95:434-442.

8. Peters EN, Budney AJ, Carroll KM. Clinical correlates of co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107:1404-1417.

9. Gruber AJ, Pope HG, Hudson JI, et al. Attributes of long-term heavy cannabis users: a case-control study. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1415-1422.

10. Palamar JJ, Fenstermaker M, Kamboukos D, et al. Adverse psychosocial outcomes associated with drug use among US high school seniors: a comparison of alcohol and marijuana. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40:438-446.

11. Zwerling C, Ryan J, Orav EJ. The efficacy of preemployment drug screening for marijuana and cocaine in predicting employment outcome. JAMA. 1990;264:2639-2643.

12. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:1123-1135.

13. Bell C, Slim J, Flaten HK, et al. Butane hash oil burns associated with marijuana liberalization in Colorado. J Med Toxicol. 2015;11:422-425.

14. Huang DYC, Lanza HI, Anglin MD. Association between adolescent substance use and obesity in young adulthood: a group-based dual trajectory analysis. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2653-2660.

15. Rajavashisth TB, Shaheen M, Norris KC, et al. Decreased prevalence of diabetes in marijuana users: cross-sectional data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000494.

16. Cho CM, Hirsch R, Johnstone S. General and oral health implications of cannabis use. Aust Dent J. 2005;50:70-74.

17. Gorzalka BB, Hill MN, Chang SC. Male-female differences in the effects of cannabinoids on sexual behavior and gonadal hormone function. Horm Behav. 2010;58:91-99.

18. Desbois AC, Cacoub P. Cannabis-associated arterial disease. Ann Vasc Surg. 2013;27:996-1005.

19. Mills B, Yepes A, Nugent K. Synthetic cannabinoids. Am J Med Sci. 2015;350:59-62.

20. Tuv SS, Strand MC, Karinen R, et al. Effect and occurrence of synthetic cannabinoids. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2012;132:2285-2288.

21. Wallace EA, Andrews SE, Garmany CL, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: literature review and proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm. South Med J. 2011;104:659-964.

22. Gates P, Jaffe A, Copeland J. Cannabis smoking and respiratory health: considerations of the literature. Respirology. 2014;19:655-662.

23. Pletcher MJ, Vittinghoff E, Kalhan R, et al. Association between marijuana exposure and pulmonary function over 20 years: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. JAMA. 2012;307:173-181.

24. Verweij PE, Kerremans JJ, Vos A, et al. Fungal contamination of tobacco and marijuana. JAMA. 2000;284:2875.

25. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. Evidence on the carcinogenicity of marijuana smoke. August 2009. Available at: http://oehha.ca.gov/media/downloads/crnr/finalmjsmokehid.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2015.

26. Stone D. Cannabis, pesticides and conflicting laws: the dilemma for legalized States and implications for public health. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69:284-288.

27. Hashibe M, Straif K, Tashkin DP, et al. Epidemiologic review of marijuana and cancer risk. Alcohol. 2005;35:265-275.

28. Liang C, McClean MD, Marsit C, et al. A population-based case-control study of marijuana use and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2009;2:759-768.

29. Thomas AA, Wallner LP, Quinn VP, et al. Association between cannabis use and the risk of bladder cancer: results from the California Men’s Health Study. Urology. 2015;85:388-392.

30. Holly EA, Lele C, Bracci PM, et al. Case-control study of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma among women and heterosexual men in the San Francisco Bay area, California. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:375-389.

31. Massi P, Solinas M, Cinquina V, et al. Cannabidiol as potential anticancer drug. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:303-312.

32. Ashbridge M, Hayden JA, Cartwright JL. Acute cannabis consumption and motor vehicle collision risk: systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e536.

33.Barrio G, Jimenez-Mejias E, Pulido J, et al. Association between cannabis use and non-traffic injuries. Accid Anal Prev. 2012;47:172-176.

34. MacDonald S, Hall W, Roman P, et al. Testing for cannabis in the work-place: a review of the evidence. Addiction. 2010;105:408-416.

35. Sewell RA, Poling J, Sofuoglu M. The effect of cannabis compared with alcohol on driving. Am J Addict. 2009;18:185-193.

36. Ramaekers JG, Berghaus G, van Laar M, et al. Dose related risk of motor vehicle crashes after cannabis use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73:109-119.

37. Menetrey A, Augsburger M, Favrat B, et al. Assessment of driving capability through the use of clinical and psychomotor tests in relation to blood cannabinoid levels following oral administration of 20 mg dronabinol or of a cannabis decoction made with 20 or 60 mg Δ9-THC. J Anal Toxicol. 2005;29:327-338.

38. Raemakers JG, Kaurert G, van Ruitenbeek P, et al. High-potency marijuana impairs executive function and inhibitory motor control. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2296-2303.

39. Leirer VO, Yesavage JA, Morrow DG. Marijuana carry-over effects on aircraft pilot performance. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1991;62:221-227.

40. Calabria B, Degenhardt L, Hall W, et al. Does cannabis use increase the risk of death? Systematic review of epidemiological evidence on adverse effects of cannabis use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:318-330.

41. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Monitoring health concerns related to marijuana in Colorado: 2014. Changes in marijuana use patterns, systematic literature review, and possible marijuana-related health effects. Available at: http://www2.cde.state.co.us/artemis/hemonos/he1282m332015internet/he1282m332015internet01.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2015.

42. Behnke M, Smith VC, Committee on Substance Abuse, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Perinatal substance abuse: short- and long-term effects on the exposed fetus. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1009-1024.

43. Batalla A, Bhattacharyya S, Yücel M, et al. Structural and functional imaging studies in chronic cannabis users: a systematic review of adolescent and adult findings. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55821.

44. Crean RD, Crane NA, Mason BJ. An evidence based review of acute and long-term effects of cannabis use on executive cognitive functions. J Addict Med. 2011;5:1-8.

45. Pavisian B, MacIntosh BJ, Szilagyi G, et al. Effects of cannabis on cognition in patients with multiple sclerosis: a psychometric and MRI study. Neurology. 2014;82:1879-1887.

46. Bartholomew J, Holroyd S, Heffernan TM. Does cannabis use affect prospective memory in young adults? J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:241-246.

47. Copeland J, Rooke S, Swift W. Changes in cannabis use among young people: impact on mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26:325-329.

48. Ari M, Sahpolat M, Kokacya H, et al. Amotivational syndrome: less known and diagnosed as a clinical. J Mood Disord. 2015;5:31-35.

49. Zvolensky MJ, Cougle JR, Johnson KA, et al. Marijuana use and panic psychopathology among a representative sample of adults. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;18(2):129-134.

50. Yarnell S. The use of medicinal marijuana for posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the current literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3).

51. Le Bec PY, Fatséas M, Denis C, et al. Cannabis and psychosis: search of a causal link through a critical and systematic review. Encephale. 2009;35:377-385.

52. Englund A, Morrison PD, Nottage J, et al. Cannabidiol inhibits THC-elicited paranoid symptoms and hippocampal-dependent memory impairment. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:19-27.

53. Lopez-Quintero C, Perez de los Cobos J, Hasin DS, et al. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011:115:120-130.

54. Degenhardt L, Dierker L, Chiu WT, et al. Evaluating the drug use “gateway” theory using cross-national data: consistency and associations of the order of initiation of drug use among participants in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:84-97.

55. Vandrey RG, Budney AJ, Hughes JR, et al. A within subject comparison of withdrawal symptoms during abstinence from cannabis, tobacco, and both substances. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:48-54.

56.Budney AJ, Roffman R, Stephens RS, et al. Marijuana dependence and its treatment. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2007;4:4-16.

57. Turner SD, Spithoff S, Kahan M. Approach to cannabis use disorder in primary care: focus on youth and other high-risk users. Can Fam Phys. 2014;60:801-808.

58. Piontek D, Kraus L, Klempova D. Short scales to assess cannabis-related problems: a review of psychometric properties. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2008;3:25.

59. Saitz R, Palfai TPA, Cheng DM, et al. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: the ASPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:502-513.

60. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, et al. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689-1695.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Screen all patients for use of addiction-prone substances. A

› Screen cannabis users with a validated secondary screen for problematic use. A

› Counsel patients that there is no evidence that use of recreational cannabis is safe; advise them that it can cause numerous physical, psychomotor, cognitive, and psychiatric effects. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Approximately 156 million Americans (49% of the population) have tried cannabis.1 About 5.7 million people ages 12 years and older use it daily or almost daily, a number that has nearly doubled since 2006.2 There are 6600 new users in the United States every day,2 and almost half of all high school students will have tried it by graduation.3

There is limited evidence that cannabis may have medical benefit in some circumstances.4 (See “Medical marijuana: A treatment worth trying?” J Fam Pract. 2016;65:178-185 or http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/106836/medical-marijuana-treatment-worth-trying.) As a result, it is now legal for medical purposes in 25 states. Recreational use by adults is also legal in 4 states and the District of Columbia.5 The US Food and Drug Administration, however, has reaffirmed its stance that marijuana is a Schedule I drug on the basis of its “high potential for abuse” and the absence of “currently accepted medical uses.”6

The effects of legalizing the medical and recreational use of cannabis for individuals—and society as a whole—are uncertain. Debate is ongoing about the risks, benefits, and rights of individuals. Some argue it is safer than alcohol or that criminalization has been ineffective and even harmful. Others make the case for personal liberty and autonomy. Still, others are convinced legalization is a misdirected experiment that will result in diverse adverse outcomes. Regardless, it is important that primary care providers understand the ramifications of marijuana use. This evidence-based narrative highlights major negative consequences of non-medical cannabinoid use.

Potential adverse consequences of cannabis use

Although the potential adverse consequences are vast, the literature on this subject is limited for various reasons:

- Many studies are observational with a small sample size.

- Most studies examine smoked cannabis—not other routes of delivery.

- When smoked, the dose, frequency, duration, and smoking technique are variable.

- The quantity of Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive component in cannabis, is variable. (For more on the chemical properties of the marijuana plant, see “Cannabinoids: A diverse group of chemicals.”7)

- Most studies do not examine medical users, who are expected to use less cannabis or lower doses of THC.

- There are confounding effects of other drugs, notably tobacco, which is used by up to 90% of cannabis users.8

Lower quality of life. In general, regular non-medical cannabis use is associated with a lower quality of life and poorer socioeconomic outcomes (TABLE 1).9-12 Physical and mental health is ranked lower by heavy users as compared to extremely low users.9 Some who attempt butane extraction of THC from the plant have experienced explosions and severe burns.13

Studies regarding cannabis use and weight are conflicting. Appetite and weight may increase initially, and young adults who increase their use of the drug are more likely to find themselves on an increasing obesity trajectory.14 However, in an observational study of nearly 11,000 participants ages 20 to 59 years, cannabis users had a lower body mass index, better lipid parameters, and were less likely to have diabetes than non-using counterparts.15

Elevated rates of MI. Chronic effects may include oral health problems,16 gynecomastia, and changes in sexual function.17 Elevated rates of myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, limb arteritis, and stroke have been observed.18 Synthetic cannabinoids have been associated with heart attacks and acute renal injury in youth;19,20 however, plant-based marijuana does not affect the kidneys. In addition, high doses of plant-based marijuana can result in cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, characterized by cyclic vomiting and compulsive bathing that resolves with cessation of the drug.21

No major pulmonary effects. Interestingly, cannabis does not appear to have major negative pulmonary effects. Acutely, smoking marijuana causes bronchodilation.22 Chronic, low-level use over 20 years is associated with an increase in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), but this upward trend diminishes and may reverse in high-level users.23 Although higher lung volumes are observed, cannabis does not appear to contribute to the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but can cause chronic bronchitis that resolves with smoking cessation.22 Chronic use has also been tied to airway infection. Lastly, fungal growth has been found on marijuana plants, which is concerning because of the potential to expose people to Aspergillus.22,24

Cannabis and cancer? The jury is out. Cannabis contains at least 33 carcinogens25 and may be contaminated with pesticides,26 but research about its relationship with cancer is incomplete. Although smoking results in histopathologic changes of the bronchial mucosa, evidence of lung cancer is mixed.22,25,27 Some studies have suggested associations with cancers of the brain, testis, prostate, and cervix,25,27 as well as certain rare cancers in children due to parental exposure.25,27

There are conflicting data about associations with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma,25,27,28 bladder cancer,25,29 and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.25,30 Some studies suggest marijuana offers protection against certain types of cancer. In fact, it appears that some cannabinoids found in marijuana, such as cannabidiol (CBD), may be antineoplastic.31 The potential oncogenic effects of edible and topical cannabinoid products have not been investigated.

Use linked to car accidents. More recent work indicates cannabis use is associated with injuries in motor vehicle,32 non-traffic,33 and workplace34 settings. In fact, a meta-analysis found a near-doubling of motor vehicle accidents with recent use.32 Risk is dose-dependent and heightened with alcohol.35-37 Psychomotor impairment persists for at least 6 hours after smoking cannabis,38 at least 10 hours after ingesting it,37 and may last up to 24 hours, as indicated by a study involving pilots using a flight simulator.39

In contrast to alcohol, there is a greater decrement in routine vs complex driving tasks in experimental studies.35,36 Behavioral strategies, like driving slowly, are employed to compensate for impairment, but the ability to do so is lost with alcohol co-ingestion.35 Importantly, individuals using marijuana may not recognize the presence or extent of the impairment they are experiencing,37,39 placing themselves and others in danger.

Data are insufficient to ascribe to marijuana an increase in overall mortality,40 and there have been no reported overdose deaths from respiratory depression. However, a few deaths and a greater number of hospitalizations, due mainly to central nervous system effects including agitation, depression, coma, delirium, and toxic psychosis, have been attributed to the use of synthetic cannabinoids.20

Cannabis use can pose a risk to the fetus. About 5% of pregnant women report recent marijuana use2 for recreational or medical reasons (eg, morning sickness), and there is concern about its effects on the developing fetus. Certain rare pediatric cancers22,25 and birth defects41 have been reported with cannabis use (TABLE 222,25,41,42). Neonatal withdrawal is minor, if present at all.42 Moderate evidence indicates prenatal and breastfeeding exposure can result in multiple developmental problems, as well as an increased likelihood of initiating tobacco and marijuana use as teens.41,42

Cognitive effects of cannabis are a concern. The central nervous system is not fully myelinated until the age of 18, and complete maturation continues beyond that. Due to neuroplasticity, life experiences and exogenous agents may result in further changes. Cannabis produces changes in brain structure and function that are evident on neuroimaging.43 Although accidental pediatric intoxication is alarming, negative consequences are likely to be of short duration.

Regular use by youth, on the other hand, negatively affects cognition and delays brain maturation, especially for younger initiates.9,38,44 With abstinence, deficits tend to normalize, but they may last indefinitely among young people who continue to use marijuana.44

Dyscognition is less severe and is more likely to resolve with abstinence in adults,44 which may tip the scale for adults weighing whether to use cannabis for a medical purpose.45 Keep in mind that individuals may not be aware of their cognitive deficits,46 even though nearly all domains (from basic motor coordination to more complex executive function tasks, such as the ability to control emotions and behavior) are affected.44 A possible exception may be improvement in attention with acute use in daily, but not occasional, users.44 Highly focused attention, however, is not always beneficial if it delays redirection toward a new urgent stimulus.

Mood benefit? Research suggests otherwise. The psychiatric effects of cannabis are not fully understood. Users may claim mood benefit, but research suggests marijuana prompts the development or worsening of anxiety, depression, and suicidality.12,47 Violence, paranoia, and borderline personality features have also been associated with use.38,47 Amotivational syndrome, a disorder that includes apathy, callousness, and antisocial behavior, has been described, but the interplay between cannabis and motivation beyond recent use is unclear.48

Lifetime cannabis use is related to panic,49 yet correlational studies suggest both benefit and problems for individuals who use cannabis for posttraumatic stress disorder.50 It is now well established that marijuana use is an independent causal risk factor for the development of psychosis, particularly in vulnerable youth, and that it worsens schizophrenia in those who suffer from it.51 Human experimental studies suggest this may be because the effect of THC is counteracted by CBD.52 Synthetic cannabinoids are even more potent anxiogenic and psychogenic agents than plant-based marijuana.19,20

Cannabis Use Disorder

About 9% of those who try cannabis develop Cannabis Use Disorder, which is characterized by continued use of the substance despite significant distress or impairment.53 Cannabis Use Disorder is essentially an addiction. Primary risk factors include male gender, younger age at marijuana initiation, and personal or family history of other substance or psychiatric problems.53

Although cannabis use often precedes use of other addiction-prone substances, it remains unclear if it is a “gateway” to the use of other illicit drugs.54 Marijuana withdrawal is relatively minor and is comparable to that for tobacco.55 While there are no known effective pharmacotherapies for discontinuing cannabis use, addiction therapy—including cognitive behavioral therapy and trigger management—is effective.56

SIDEBAR

Cannabinoids: A diverse group of chemicalsCannabis, the genus name for 3 species of marijuana plant (sativa, indica, ruderalis), has come to mean any psychoactive part of the plant and is used interchangeably with “marijuana.” There are at least 85 different cannabinoids in the native plant.7

Cannabinoids are a diverse group of chemicals that have activity at cannabinoid receptors. Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a partial agonist of the CB1 receptor, is the primary psychoactive component and is found in larger quantities in Cannabis sativa, which is preferred by non-medical users. Cannabidiol (CBD), a weak partial CB1 antagonist, exhibits few, if any, psychotropic properties and is more plentiful in Cannabis indica.

Synthetic cannabinioids are a heterogeneous group of manufactured drugs that are full CB1 agonists and that are more potent than THC, yet are often assumed to be safe by users. Typically, they are dissolved in solvents, sprayed onto inert plant materials, and marketed as herbal products like “K2” and “spice.”

So how should the evidence inform your care?

Screen all patients for use of cannabinoids and other addiction-prone substances.57 Follow any affirmative answers to your questions about cannabis use by asking about potential negative consequences of use. For example, ask patients:

- How often during the past 6 months did you find that you were unable to stop using cannabis once you started?

- How often during the past 6 months did you fail to do what was expected of you because of using cannabis? (For more questions, see the Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test available at: http://www.otago.ac.nz/nationaladdictioncentre/pdfs/cudit-r.pdf.)

Other validated screening tools include the Severity of Dependence Scale, the Cannabis Abuse Screening Test, and the Problematic Use of Marijuana.58

Counsel patients about possible adverse effects and inform them there is no evidence that recreational marijuana or synthetic cannabinoids can be used safely over time. Consider medical use requests only if there is a favorable risk/benefit balance, other recognized treatment options have been exhausted, and you have a strong understanding of the use of cannabis in the medical condition being considered.4

Since brief interventions using motivational interviewing to reduce or eliminate recreational use have not been found to be effective,59 referral to an addiction specialist may be indicated. If a diagnosis of cannabis use disorder is established, then abstinence from addiction-prone substances including marijuana, programs like Marijuana Anonymous (Available at: https://www.marijuana-anonymous.org/), and individualized addiction therapy scaled to the severity of the condition can be effective.56 Because psychiatric conditions frequently co-occur and complicate addiction,53 they should be screened for and managed, as well.

Drug testing. Cannabis Use Disorder has significant relapse potential.60 Abstinence and treatment adherence should be ascertained through regular follow-up that includes a clinical interview, exam, and body fluid drug testing. Point-of-care urine analysis for substances of potential addiction has limited utility. Definitive testing of urine with gas chromotography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) or liquid chromatography (LC/MS-MS) can eliminate THC false-positives and false-negatives that can occur with point-of-care urine immunoassays. In addition, GCMS and LC/MS-MS can identify synthetic cannabinoids; in-office immunoassays cannot.

If the patient relapses, subsequent medical care should be coordinated with an addiction specialist with the goal of helping the patient to abstain from cannabis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Wright, MD, FAAFP, 5325 Ridge Trail, Littleton, CO 80123; [email protected].

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Screen all patients for use of addiction-prone substances. A

› Screen cannabis users with a validated secondary screen for problematic use. A

› Counsel patients that there is no evidence that use of recreational cannabis is safe; advise them that it can cause numerous physical, psychomotor, cognitive, and psychiatric effects. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Approximately 156 million Americans (49% of the population) have tried cannabis.1 About 5.7 million people ages 12 years and older use it daily or almost daily, a number that has nearly doubled since 2006.2 There are 6600 new users in the United States every day,2 and almost half of all high school students will have tried it by graduation.3

There is limited evidence that cannabis may have medical benefit in some circumstances.4 (See “Medical marijuana: A treatment worth trying?” J Fam Pract. 2016;65:178-185 or http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/106836/medical-marijuana-treatment-worth-trying.) As a result, it is now legal for medical purposes in 25 states. Recreational use by adults is also legal in 4 states and the District of Columbia.5 The US Food and Drug Administration, however, has reaffirmed its stance that marijuana is a Schedule I drug on the basis of its “high potential for abuse” and the absence of “currently accepted medical uses.”6

The effects of legalizing the medical and recreational use of cannabis for individuals—and society as a whole—are uncertain. Debate is ongoing about the risks, benefits, and rights of individuals. Some argue it is safer than alcohol or that criminalization has been ineffective and even harmful. Others make the case for personal liberty and autonomy. Still, others are convinced legalization is a misdirected experiment that will result in diverse adverse outcomes. Regardless, it is important that primary care providers understand the ramifications of marijuana use. This evidence-based narrative highlights major negative consequences of non-medical cannabinoid use.

Potential adverse consequences of cannabis use

Although the potential adverse consequences are vast, the literature on this subject is limited for various reasons:

- Many studies are observational with a small sample size.

- Most studies examine smoked cannabis—not other routes of delivery.

- When smoked, the dose, frequency, duration, and smoking technique are variable.

- The quantity of Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive component in cannabis, is variable. (For more on the chemical properties of the marijuana plant, see “Cannabinoids: A diverse group of chemicals.”7)

- Most studies do not examine medical users, who are expected to use less cannabis or lower doses of THC.

- There are confounding effects of other drugs, notably tobacco, which is used by up to 90% of cannabis users.8

Lower quality of life. In general, regular non-medical cannabis use is associated with a lower quality of life and poorer socioeconomic outcomes (TABLE 1).9-12 Physical and mental health is ranked lower by heavy users as compared to extremely low users.9 Some who attempt butane extraction of THC from the plant have experienced explosions and severe burns.13

Studies regarding cannabis use and weight are conflicting. Appetite and weight may increase initially, and young adults who increase their use of the drug are more likely to find themselves on an increasing obesity trajectory.14 However, in an observational study of nearly 11,000 participants ages 20 to 59 years, cannabis users had a lower body mass index, better lipid parameters, and were less likely to have diabetes than non-using counterparts.15

Elevated rates of MI. Chronic effects may include oral health problems,16 gynecomastia, and changes in sexual function.17 Elevated rates of myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, limb arteritis, and stroke have been observed.18 Synthetic cannabinoids have been associated with heart attacks and acute renal injury in youth;19,20 however, plant-based marijuana does not affect the kidneys. In addition, high doses of plant-based marijuana can result in cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, characterized by cyclic vomiting and compulsive bathing that resolves with cessation of the drug.21

No major pulmonary effects. Interestingly, cannabis does not appear to have major negative pulmonary effects. Acutely, smoking marijuana causes bronchodilation.22 Chronic, low-level use over 20 years is associated with an increase in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), but this upward trend diminishes and may reverse in high-level users.23 Although higher lung volumes are observed, cannabis does not appear to contribute to the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but can cause chronic bronchitis that resolves with smoking cessation.22 Chronic use has also been tied to airway infection. Lastly, fungal growth has been found on marijuana plants, which is concerning because of the potential to expose people to Aspergillus.22,24

Cannabis and cancer? The jury is out. Cannabis contains at least 33 carcinogens25 and may be contaminated with pesticides,26 but research about its relationship with cancer is incomplete. Although smoking results in histopathologic changes of the bronchial mucosa, evidence of lung cancer is mixed.22,25,27 Some studies have suggested associations with cancers of the brain, testis, prostate, and cervix,25,27 as well as certain rare cancers in children due to parental exposure.25,27

There are conflicting data about associations with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma,25,27,28 bladder cancer,25,29 and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.25,30 Some studies suggest marijuana offers protection against certain types of cancer. In fact, it appears that some cannabinoids found in marijuana, such as cannabidiol (CBD), may be antineoplastic.31 The potential oncogenic effects of edible and topical cannabinoid products have not been investigated.

Use linked to car accidents. More recent work indicates cannabis use is associated with injuries in motor vehicle,32 non-traffic,33 and workplace34 settings. In fact, a meta-analysis found a near-doubling of motor vehicle accidents with recent use.32 Risk is dose-dependent and heightened with alcohol.35-37 Psychomotor impairment persists for at least 6 hours after smoking cannabis,38 at least 10 hours after ingesting it,37 and may last up to 24 hours, as indicated by a study involving pilots using a flight simulator.39

In contrast to alcohol, there is a greater decrement in routine vs complex driving tasks in experimental studies.35,36 Behavioral strategies, like driving slowly, are employed to compensate for impairment, but the ability to do so is lost with alcohol co-ingestion.35 Importantly, individuals using marijuana may not recognize the presence or extent of the impairment they are experiencing,37,39 placing themselves and others in danger.

Data are insufficient to ascribe to marijuana an increase in overall mortality,40 and there have been no reported overdose deaths from respiratory depression. However, a few deaths and a greater number of hospitalizations, due mainly to central nervous system effects including agitation, depression, coma, delirium, and toxic psychosis, have been attributed to the use of synthetic cannabinoids.20

Cannabis use can pose a risk to the fetus. About 5% of pregnant women report recent marijuana use2 for recreational or medical reasons (eg, morning sickness), and there is concern about its effects on the developing fetus. Certain rare pediatric cancers22,25 and birth defects41 have been reported with cannabis use (TABLE 222,25,41,42). Neonatal withdrawal is minor, if present at all.42 Moderate evidence indicates prenatal and breastfeeding exposure can result in multiple developmental problems, as well as an increased likelihood of initiating tobacco and marijuana use as teens.41,42

Cognitive effects of cannabis are a concern. The central nervous system is not fully myelinated until the age of 18, and complete maturation continues beyond that. Due to neuroplasticity, life experiences and exogenous agents may result in further changes. Cannabis produces changes in brain structure and function that are evident on neuroimaging.43 Although accidental pediatric intoxication is alarming, negative consequences are likely to be of short duration.

Regular use by youth, on the other hand, negatively affects cognition and delays brain maturation, especially for younger initiates.9,38,44 With abstinence, deficits tend to normalize, but they may last indefinitely among young people who continue to use marijuana.44

Dyscognition is less severe and is more likely to resolve with abstinence in adults,44 which may tip the scale for adults weighing whether to use cannabis for a medical purpose.45 Keep in mind that individuals may not be aware of their cognitive deficits,46 even though nearly all domains (from basic motor coordination to more complex executive function tasks, such as the ability to control emotions and behavior) are affected.44 A possible exception may be improvement in attention with acute use in daily, but not occasional, users.44 Highly focused attention, however, is not always beneficial if it delays redirection toward a new urgent stimulus.

Mood benefit? Research suggests otherwise. The psychiatric effects of cannabis are not fully understood. Users may claim mood benefit, but research suggests marijuana prompts the development or worsening of anxiety, depression, and suicidality.12,47 Violence, paranoia, and borderline personality features have also been associated with use.38,47 Amotivational syndrome, a disorder that includes apathy, callousness, and antisocial behavior, has been described, but the interplay between cannabis and motivation beyond recent use is unclear.48

Lifetime cannabis use is related to panic,49 yet correlational studies suggest both benefit and problems for individuals who use cannabis for posttraumatic stress disorder.50 It is now well established that marijuana use is an independent causal risk factor for the development of psychosis, particularly in vulnerable youth, and that it worsens schizophrenia in those who suffer from it.51 Human experimental studies suggest this may be because the effect of THC is counteracted by CBD.52 Synthetic cannabinoids are even more potent anxiogenic and psychogenic agents than plant-based marijuana.19,20

Cannabis Use Disorder

About 9% of those who try cannabis develop Cannabis Use Disorder, which is characterized by continued use of the substance despite significant distress or impairment.53 Cannabis Use Disorder is essentially an addiction. Primary risk factors include male gender, younger age at marijuana initiation, and personal or family history of other substance or psychiatric problems.53

Although cannabis use often precedes use of other addiction-prone substances, it remains unclear if it is a “gateway” to the use of other illicit drugs.54 Marijuana withdrawal is relatively minor and is comparable to that for tobacco.55 While there are no known effective pharmacotherapies for discontinuing cannabis use, addiction therapy—including cognitive behavioral therapy and trigger management—is effective.56

SIDEBAR

Cannabinoids: A diverse group of chemicalsCannabis, the genus name for 3 species of marijuana plant (sativa, indica, ruderalis), has come to mean any psychoactive part of the plant and is used interchangeably with “marijuana.” There are at least 85 different cannabinoids in the native plant.7

Cannabinoids are a diverse group of chemicals that have activity at cannabinoid receptors. Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a partial agonist of the CB1 receptor, is the primary psychoactive component and is found in larger quantities in Cannabis sativa, which is preferred by non-medical users. Cannabidiol (CBD), a weak partial CB1 antagonist, exhibits few, if any, psychotropic properties and is more plentiful in Cannabis indica.

Synthetic cannabinioids are a heterogeneous group of manufactured drugs that are full CB1 agonists and that are more potent than THC, yet are often assumed to be safe by users. Typically, they are dissolved in solvents, sprayed onto inert plant materials, and marketed as herbal products like “K2” and “spice.”

So how should the evidence inform your care?

Screen all patients for use of cannabinoids and other addiction-prone substances.57 Follow any affirmative answers to your questions about cannabis use by asking about potential negative consequences of use. For example, ask patients:

- How often during the past 6 months did you find that you were unable to stop using cannabis once you started?

- How often during the past 6 months did you fail to do what was expected of you because of using cannabis? (For more questions, see the Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test available at: http://www.otago.ac.nz/nationaladdictioncentre/pdfs/cudit-r.pdf.)

Other validated screening tools include the Severity of Dependence Scale, the Cannabis Abuse Screening Test, and the Problematic Use of Marijuana.58

Counsel patients about possible adverse effects and inform them there is no evidence that recreational marijuana or synthetic cannabinoids can be used safely over time. Consider medical use requests only if there is a favorable risk/benefit balance, other recognized treatment options have been exhausted, and you have a strong understanding of the use of cannabis in the medical condition being considered.4

Since brief interventions using motivational interviewing to reduce or eliminate recreational use have not been found to be effective,59 referral to an addiction specialist may be indicated. If a diagnosis of cannabis use disorder is established, then abstinence from addiction-prone substances including marijuana, programs like Marijuana Anonymous (Available at: https://www.marijuana-anonymous.org/), and individualized addiction therapy scaled to the severity of the condition can be effective.56 Because psychiatric conditions frequently co-occur and complicate addiction,53 they should be screened for and managed, as well.

Drug testing. Cannabis Use Disorder has significant relapse potential.60 Abstinence and treatment adherence should be ascertained through regular follow-up that includes a clinical interview, exam, and body fluid drug testing. Point-of-care urine analysis for substances of potential addiction has limited utility. Definitive testing of urine with gas chromotography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) or liquid chromatography (LC/MS-MS) can eliminate THC false-positives and false-negatives that can occur with point-of-care urine immunoassays. In addition, GCMS and LC/MS-MS can identify synthetic cannabinoids; in-office immunoassays cannot.

If the patient relapses, subsequent medical care should be coordinated with an addiction specialist with the goal of helping the patient to abstain from cannabis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Wright, MD, FAAFP, 5325 Ridge Trail, Littleton, CO 80123; [email protected].

1. Pew Research Center. 6 facts about marijuana. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/14/6-facts-about-marijuana/. Accessed September 27, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. HHS Pub # (SMA) 14-4863. 2014. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2015.

3. Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future National Survey on Drug Use 1975-2015. Available at: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Accessed September 23, 2015.

4. Metts J, Wright S, Sundaram J, et al. Medical marijuana: a treatment worth trying? J Fam Pract. 2016;65:178-185.

5. Governing the states and localities. State marijuana laws map. Available at: http://www.governing.com/gov-data/state-marijuana-laws-map-medical-recreational.html. Accessed October 12, 2016.

6. US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug scheduling. Available at: https://www.dea.gov/druginfo/ds.shtml. Accessed October 12, 2016.

7. El-Alfy AT, Ivey K, Robinson K, et al. Antidepressant-like effect of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa L. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;95:434-442.

8. Peters EN, Budney AJ, Carroll KM. Clinical correlates of co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107:1404-1417.

9. Gruber AJ, Pope HG, Hudson JI, et al. Attributes of long-term heavy cannabis users: a case-control study. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1415-1422.

10. Palamar JJ, Fenstermaker M, Kamboukos D, et al. Adverse psychosocial outcomes associated with drug use among US high school seniors: a comparison of alcohol and marijuana. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40:438-446.

11. Zwerling C, Ryan J, Orav EJ. The efficacy of preemployment drug screening for marijuana and cocaine in predicting employment outcome. JAMA. 1990;264:2639-2643.

12. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:1123-1135.

13. Bell C, Slim J, Flaten HK, et al. Butane hash oil burns associated with marijuana liberalization in Colorado. J Med Toxicol. 2015;11:422-425.

14. Huang DYC, Lanza HI, Anglin MD. Association between adolescent substance use and obesity in young adulthood: a group-based dual trajectory analysis. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2653-2660.

15. Rajavashisth TB, Shaheen M, Norris KC, et al. Decreased prevalence of diabetes in marijuana users: cross-sectional data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000494.

16. Cho CM, Hirsch R, Johnstone S. General and oral health implications of cannabis use. Aust Dent J. 2005;50:70-74.

17. Gorzalka BB, Hill MN, Chang SC. Male-female differences in the effects of cannabinoids on sexual behavior and gonadal hormone function. Horm Behav. 2010;58:91-99.

18. Desbois AC, Cacoub P. Cannabis-associated arterial disease. Ann Vasc Surg. 2013;27:996-1005.

19. Mills B, Yepes A, Nugent K. Synthetic cannabinoids. Am J Med Sci. 2015;350:59-62.

20. Tuv SS, Strand MC, Karinen R, et al. Effect and occurrence of synthetic cannabinoids. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2012;132:2285-2288.

21. Wallace EA, Andrews SE, Garmany CL, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: literature review and proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm. South Med J. 2011;104:659-964.

22. Gates P, Jaffe A, Copeland J. Cannabis smoking and respiratory health: considerations of the literature. Respirology. 2014;19:655-662.

23. Pletcher MJ, Vittinghoff E, Kalhan R, et al. Association between marijuana exposure and pulmonary function over 20 years: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. JAMA. 2012;307:173-181.

24. Verweij PE, Kerremans JJ, Vos A, et al. Fungal contamination of tobacco and marijuana. JAMA. 2000;284:2875.

25. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. Evidence on the carcinogenicity of marijuana smoke. August 2009. Available at: http://oehha.ca.gov/media/downloads/crnr/finalmjsmokehid.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2015.

26. Stone D. Cannabis, pesticides and conflicting laws: the dilemma for legalized States and implications for public health. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69:284-288.

27. Hashibe M, Straif K, Tashkin DP, et al. Epidemiologic review of marijuana and cancer risk. Alcohol. 2005;35:265-275.

28. Liang C, McClean MD, Marsit C, et al. A population-based case-control study of marijuana use and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2009;2:759-768.

29. Thomas AA, Wallner LP, Quinn VP, et al. Association between cannabis use and the risk of bladder cancer: results from the California Men’s Health Study. Urology. 2015;85:388-392.

30. Holly EA, Lele C, Bracci PM, et al. Case-control study of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma among women and heterosexual men in the San Francisco Bay area, California. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:375-389.

31. Massi P, Solinas M, Cinquina V, et al. Cannabidiol as potential anticancer drug. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:303-312.

32. Ashbridge M, Hayden JA, Cartwright JL. Acute cannabis consumption and motor vehicle collision risk: systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e536.

33.Barrio G, Jimenez-Mejias E, Pulido J, et al. Association between cannabis use and non-traffic injuries. Accid Anal Prev. 2012;47:172-176.

34. MacDonald S, Hall W, Roman P, et al. Testing for cannabis in the work-place: a review of the evidence. Addiction. 2010;105:408-416.

35. Sewell RA, Poling J, Sofuoglu M. The effect of cannabis compared with alcohol on driving. Am J Addict. 2009;18:185-193.

36. Ramaekers JG, Berghaus G, van Laar M, et al. Dose related risk of motor vehicle crashes after cannabis use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73:109-119.

37. Menetrey A, Augsburger M, Favrat B, et al. Assessment of driving capability through the use of clinical and psychomotor tests in relation to blood cannabinoid levels following oral administration of 20 mg dronabinol or of a cannabis decoction made with 20 or 60 mg Δ9-THC. J Anal Toxicol. 2005;29:327-338.

38. Raemakers JG, Kaurert G, van Ruitenbeek P, et al. High-potency marijuana impairs executive function and inhibitory motor control. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2296-2303.

39. Leirer VO, Yesavage JA, Morrow DG. Marijuana carry-over effects on aircraft pilot performance. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1991;62:221-227.

40. Calabria B, Degenhardt L, Hall W, et al. Does cannabis use increase the risk of death? Systematic review of epidemiological evidence on adverse effects of cannabis use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:318-330.

41. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Monitoring health concerns related to marijuana in Colorado: 2014. Changes in marijuana use patterns, systematic literature review, and possible marijuana-related health effects. Available at: http://www2.cde.state.co.us/artemis/hemonos/he1282m332015internet/he1282m332015internet01.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2015.

42. Behnke M, Smith VC, Committee on Substance Abuse, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Perinatal substance abuse: short- and long-term effects on the exposed fetus. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1009-1024.

43. Batalla A, Bhattacharyya S, Yücel M, et al. Structural and functional imaging studies in chronic cannabis users: a systematic review of adolescent and adult findings. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55821.

44. Crean RD, Crane NA, Mason BJ. An evidence based review of acute and long-term effects of cannabis use on executive cognitive functions. J Addict Med. 2011;5:1-8.

45. Pavisian B, MacIntosh BJ, Szilagyi G, et al. Effects of cannabis on cognition in patients with multiple sclerosis: a psychometric and MRI study. Neurology. 2014;82:1879-1887.

46. Bartholomew J, Holroyd S, Heffernan TM. Does cannabis use affect prospective memory in young adults? J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:241-246.

47. Copeland J, Rooke S, Swift W. Changes in cannabis use among young people: impact on mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26:325-329.

48. Ari M, Sahpolat M, Kokacya H, et al. Amotivational syndrome: less known and diagnosed as a clinical. J Mood Disord. 2015;5:31-35.

49. Zvolensky MJ, Cougle JR, Johnson KA, et al. Marijuana use and panic psychopathology among a representative sample of adults. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;18(2):129-134.

50. Yarnell S. The use of medicinal marijuana for posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the current literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3).

51. Le Bec PY, Fatséas M, Denis C, et al. Cannabis and psychosis: search of a causal link through a critical and systematic review. Encephale. 2009;35:377-385.

52. Englund A, Morrison PD, Nottage J, et al. Cannabidiol inhibits THC-elicited paranoid symptoms and hippocampal-dependent memory impairment. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:19-27.

53. Lopez-Quintero C, Perez de los Cobos J, Hasin DS, et al. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011:115:120-130.

54. Degenhardt L, Dierker L, Chiu WT, et al. Evaluating the drug use “gateway” theory using cross-national data: consistency and associations of the order of initiation of drug use among participants in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:84-97.

55. Vandrey RG, Budney AJ, Hughes JR, et al. A within subject comparison of withdrawal symptoms during abstinence from cannabis, tobacco, and both substances. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:48-54.

56.Budney AJ, Roffman R, Stephens RS, et al. Marijuana dependence and its treatment. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2007;4:4-16.

57. Turner SD, Spithoff S, Kahan M. Approach to cannabis use disorder in primary care: focus on youth and other high-risk users. Can Fam Phys. 2014;60:801-808.

58. Piontek D, Kraus L, Klempova D. Short scales to assess cannabis-related problems: a review of psychometric properties. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2008;3:25.

59. Saitz R, Palfai TPA, Cheng DM, et al. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: the ASPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:502-513.

60. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, et al. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689-1695.

1. Pew Research Center. 6 facts about marijuana. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/14/6-facts-about-marijuana/. Accessed September 27, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. HHS Pub # (SMA) 14-4863. 2014. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2015.

3. Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future National Survey on Drug Use 1975-2015. Available at: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Accessed September 23, 2015.

4. Metts J, Wright S, Sundaram J, et al. Medical marijuana: a treatment worth trying? J Fam Pract. 2016;65:178-185.

5. Governing the states and localities. State marijuana laws map. Available at: http://www.governing.com/gov-data/state-marijuana-laws-map-medical-recreational.html. Accessed October 12, 2016.

6. US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug scheduling. Available at: https://www.dea.gov/druginfo/ds.shtml. Accessed October 12, 2016.

7. El-Alfy AT, Ivey K, Robinson K, et al. Antidepressant-like effect of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa L. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;95:434-442.

8. Peters EN, Budney AJ, Carroll KM. Clinical correlates of co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107:1404-1417.

9. Gruber AJ, Pope HG, Hudson JI, et al. Attributes of long-term heavy cannabis users: a case-control study. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1415-1422.

10. Palamar JJ, Fenstermaker M, Kamboukos D, et al. Adverse psychosocial outcomes associated with drug use among US high school seniors: a comparison of alcohol and marijuana. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40:438-446.

11. Zwerling C, Ryan J, Orav EJ. The efficacy of preemployment drug screening for marijuana and cocaine in predicting employment outcome. JAMA. 1990;264:2639-2643.

12. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:1123-1135.

13. Bell C, Slim J, Flaten HK, et al. Butane hash oil burns associated with marijuana liberalization in Colorado. J Med Toxicol. 2015;11:422-425.

14. Huang DYC, Lanza HI, Anglin MD. Association between adolescent substance use and obesity in young adulthood: a group-based dual trajectory analysis. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2653-2660.

15. Rajavashisth TB, Shaheen M, Norris KC, et al. Decreased prevalence of diabetes in marijuana users: cross-sectional data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000494.

16. Cho CM, Hirsch R, Johnstone S. General and oral health implications of cannabis use. Aust Dent J. 2005;50:70-74.

17. Gorzalka BB, Hill MN, Chang SC. Male-female differences in the effects of cannabinoids on sexual behavior and gonadal hormone function. Horm Behav. 2010;58:91-99.

18. Desbois AC, Cacoub P. Cannabis-associated arterial disease. Ann Vasc Surg. 2013;27:996-1005.

19. Mills B, Yepes A, Nugent K. Synthetic cannabinoids. Am J Med Sci. 2015;350:59-62.

20. Tuv SS, Strand MC, Karinen R, et al. Effect and occurrence of synthetic cannabinoids. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2012;132:2285-2288.

21. Wallace EA, Andrews SE, Garmany CL, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: literature review and proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm. South Med J. 2011;104:659-964.

22. Gates P, Jaffe A, Copeland J. Cannabis smoking and respiratory health: considerations of the literature. Respirology. 2014;19:655-662.

23. Pletcher MJ, Vittinghoff E, Kalhan R, et al. Association between marijuana exposure and pulmonary function over 20 years: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. JAMA. 2012;307:173-181.

24. Verweij PE, Kerremans JJ, Vos A, et al. Fungal contamination of tobacco and marijuana. JAMA. 2000;284:2875.

25. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. Evidence on the carcinogenicity of marijuana smoke. August 2009. Available at: http://oehha.ca.gov/media/downloads/crnr/finalmjsmokehid.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2015.

26. Stone D. Cannabis, pesticides and conflicting laws: the dilemma for legalized States and implications for public health. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69:284-288.

27. Hashibe M, Straif K, Tashkin DP, et al. Epidemiologic review of marijuana and cancer risk. Alcohol. 2005;35:265-275.

28. Liang C, McClean MD, Marsit C, et al. A population-based case-control study of marijuana use and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2009;2:759-768.

29. Thomas AA, Wallner LP, Quinn VP, et al. Association between cannabis use and the risk of bladder cancer: results from the California Men’s Health Study. Urology. 2015;85:388-392.

30. Holly EA, Lele C, Bracci PM, et al. Case-control study of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma among women and heterosexual men in the San Francisco Bay area, California. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:375-389.

31. Massi P, Solinas M, Cinquina V, et al. Cannabidiol as potential anticancer drug. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:303-312.

32. Ashbridge M, Hayden JA, Cartwright JL. Acute cannabis consumption and motor vehicle collision risk: systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e536.

33.Barrio G, Jimenez-Mejias E, Pulido J, et al. Association between cannabis use and non-traffic injuries. Accid Anal Prev. 2012;47:172-176.

34. MacDonald S, Hall W, Roman P, et al. Testing for cannabis in the work-place: a review of the evidence. Addiction. 2010;105:408-416.

35. Sewell RA, Poling J, Sofuoglu M. The effect of cannabis compared with alcohol on driving. Am J Addict. 2009;18:185-193.

36. Ramaekers JG, Berghaus G, van Laar M, et al. Dose related risk of motor vehicle crashes after cannabis use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73:109-119.

37. Menetrey A, Augsburger M, Favrat B, et al. Assessment of driving capability through the use of clinical and psychomotor tests in relation to blood cannabinoid levels following oral administration of 20 mg dronabinol or of a cannabis decoction made with 20 or 60 mg Δ9-THC. J Anal Toxicol. 2005;29:327-338.

38. Raemakers JG, Kaurert G, van Ruitenbeek P, et al. High-potency marijuana impairs executive function and inhibitory motor control. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2296-2303.

39. Leirer VO, Yesavage JA, Morrow DG. Marijuana carry-over effects on aircraft pilot performance. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1991;62:221-227.

40. Calabria B, Degenhardt L, Hall W, et al. Does cannabis use increase the risk of death? Systematic review of epidemiological evidence on adverse effects of cannabis use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:318-330.

41. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Monitoring health concerns related to marijuana in Colorado: 2014. Changes in marijuana use patterns, systematic literature review, and possible marijuana-related health effects. Available at: http://www2.cde.state.co.us/artemis/hemonos/he1282m332015internet/he1282m332015internet01.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2015.

42. Behnke M, Smith VC, Committee on Substance Abuse, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Perinatal substance abuse: short- and long-term effects on the exposed fetus. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1009-1024.

43. Batalla A, Bhattacharyya S, Yücel M, et al. Structural and functional imaging studies in chronic cannabis users: a systematic review of adolescent and adult findings. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55821.

44. Crean RD, Crane NA, Mason BJ. An evidence based review of acute and long-term effects of cannabis use on executive cognitive functions. J Addict Med. 2011;5:1-8.

45. Pavisian B, MacIntosh BJ, Szilagyi G, et al. Effects of cannabis on cognition in patients with multiple sclerosis: a psychometric and MRI study. Neurology. 2014;82:1879-1887.

46. Bartholomew J, Holroyd S, Heffernan TM. Does cannabis use affect prospective memory in young adults? J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:241-246.

47. Copeland J, Rooke S, Swift W. Changes in cannabis use among young people: impact on mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26:325-329.

48. Ari M, Sahpolat M, Kokacya H, et al. Amotivational syndrome: less known and diagnosed as a clinical. J Mood Disord. 2015;5:31-35.

49. Zvolensky MJ, Cougle JR, Johnson KA, et al. Marijuana use and panic psychopathology among a representative sample of adults. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;18(2):129-134.

50. Yarnell S. The use of medicinal marijuana for posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the current literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3).

51. Le Bec PY, Fatséas M, Denis C, et al. Cannabis and psychosis: search of a causal link through a critical and systematic review. Encephale. 2009;35:377-385.

52. Englund A, Morrison PD, Nottage J, et al. Cannabidiol inhibits THC-elicited paranoid symptoms and hippocampal-dependent memory impairment. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:19-27.

53. Lopez-Quintero C, Perez de los Cobos J, Hasin DS, et al. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011:115:120-130.

54. Degenhardt L, Dierker L, Chiu WT, et al. Evaluating the drug use “gateway” theory using cross-national data: consistency and associations of the order of initiation of drug use among participants in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:84-97.

55. Vandrey RG, Budney AJ, Hughes JR, et al. A within subject comparison of withdrawal symptoms during abstinence from cannabis, tobacco, and both substances. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:48-54.

56.Budney AJ, Roffman R, Stephens RS, et al. Marijuana dependence and its treatment. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2007;4:4-16.

57. Turner SD, Spithoff S, Kahan M. Approach to cannabis use disorder in primary care: focus on youth and other high-risk users. Can Fam Phys. 2014;60:801-808.

58. Piontek D, Kraus L, Klempova D. Short scales to assess cannabis-related problems: a review of psychometric properties. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2008;3:25.

59. Saitz R, Palfai TPA, Cheng DM, et al. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: the ASPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:502-513.

60. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, et al. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689-1695.

Medical marijuana: A treatment worth trying?

› Consider recommending medical marijuana for conditions with evidence supporting its use only after other treatment options have been exhausted. B

› Thoroughly screen potential candidates for medical marijuana to rule out a history of substance abuse, mental illness, and other contraindications. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series