User login

Evidence-Based Deprescribing: Reversing the Tide of Potentially Inappropriate Polypharmacy

From the Department of Internal Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Ipswich Road, Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia (Dr. Scott), School of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Herston Road, Brisbane, Australia (Dr. Scott), Centre of Research Excellence in Quality & Safety in Integrated Primary-Secondary Care, The University of Queensland, Herston Road, Brisbane, Australia (Ms. Anderson), and Charming Institute, Camp Hill, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia (Dr. Freeman).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the adverse drug events (ADEs) risk of polypharmacy; the process of deprescribing and evidence of efficacy in reducing inappropriate polypharmacy; the enablers and barriers to deprescribing; and patient and system of care level strategies that can be employed to enhance deprescribing.

- Methods: Literature review.

- Results: Inappropriate polypharmacy, especially in older people, imposes a significant burden of ADEs, ill health, disability, hospitalization and even death. The single most important predictor of inappropriate prescribing and risk of ADEs in older patients is the number of prescribed medicines. Deprescribing is the process of systematically reviewing, identifying, and discontinuing potentially inappropriate medicines (PIMs), aimed at minimizing polypharmacy and improving patient outcomes. Evidence of efficacy for deprescribing is emerging from randomized trials and observational studies, and deprescribing protocols have been developed and validated for clinical use. Barriers and enablers to deprescribing by individual prescribers center on 4 themes: (1) raising awareness of the prevalence and characteristics of PIMs; (2) overcoming clinical inertia whereby discontinuing medicines is seen as being a low value proposition compared to maintaining the status quo; (3) increasing skills and competence (self-efficacy) in deprescribing; and (4) countering external and logistical factors that impede the process.

- Conclusion: In optimizing the scale and effects of deprescribing in clinical practice, strategies that promote depresribing will need to be applied at both the level of individual patient–prescriber encounters and systems of care.

In developed countries in the modern era, about 30% of patients aged 65 years or older are prescribed 5 or more medicines [1]. Over the past decade, the prevalence of polypharmacy (use of > 5 prescription drugs) in the adult population of the United States has doubled from 8.2% in 1999–2000 to 15% in 2011–2012 [2]. While many patients may benefit from such polypharmacy [3] (defined here as 5 or more regularly prescribed medicines), it comes with increased risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) in older people [4] due to physiological changes of aging that alter pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic responses to medicines [5]. Approximately 1 in 5 medicines commonly used in older people may be inappropriate [6], rising to a third among those living in residential aged care facilities [7]. Among nursing home residents with advanced dementia, more than half receive at least 1 medicine with questionable benefit [8]. Approximately 50% of hospitalized nursing home or ambulatory care patients receive 1 or more unnecessary medicines [9]. Observational studies have documented ADEs in at least 15% of older patients, contributing to ill health [10], disability [11], hospitalization [12] and readmissions [13], increased length of stay, and, in some cases, death [14]. This high level of iatrogenic harm from potentially inappropriate medicines (PIMs) mandates a response from clinicians responsible for managing medicines.

In this narrative review, we aim to detail the ADE risk of polypharmacy, the process of deprescribing and evidence of its efficacy in reducing potentially inappropriate polypharmacy, the enablers and barriers to deprescribing, and patient and system of care level strategies that can be employed in enhancing deprescribing.

Polypharmacy As a Risk Factor for Medicine-Related Harm

The number of medicines a patient is taking is the single most important predictor of medicine-related harm [15]. One report estimated the risk of ADEs as a contributory cause of patients presenting acutely to hospital emergency departments to be 13% for 2 drugs, 38% for 4 drugs, and 82% for 7 drugs or more [16]. The more medicines an individual takes, the greater their risk of experiencing an adverse drug reaction, a drug-drug interaction, a drug-disease interaction, cascade prescribing (where more medicines are added to counteract side effects of existing medicines), nonadherence, and drug errors (wrong drug, wrong dose, missed doses, erroneous dosing frequency) [17–20]. Once the number of regular medicines rises above 5 (commonly regarded as the threshold for defining polypharmacy), observational data suggest that additional medicines independently increase the risk of frailty, falling, and hospital admission [21].

The benefits of many medicines in frail older people remain unquantified. As many as 50% of clinical trials have a specific upper age limit and approximately 80% of clinical trials exclude people with comorbidities [22,23]. Single-disease treatment guidelines based on such trials are often extrapolated to older people with multimorbidity despite an absence of evidence for benefit [24] and with little consideration of the potential burdens and harms of polypharmacy resulting from treating multiple diseases in the one patient [25]. By contrast, the risks from many medicines in older people are well known. Older people are at high risk of ADEs and toxicity due to reduced renal and liver function and age-related changes in physiological reserve, body composition, and cellular metabolism [26]. While the adverse effects of polypharmacy or of comorbidities targeted for treatment are difficult to separate, the burden of medicine-induced decline in function and quality of life is becoming better defined and appreciated [27].

Defining Evidence-Based Deprescribing

While many definitions have been proposed [28], we define evidence-based deprescribing as follows: the active process of systematically reviewing medicines being used by individual patients and, using best available evidence, identifying and discontinuing those associated with unfavorable risk–benefit trade-offs within the context of illness severity, advanced age, multi-morbidity, physical and emotional capacity, life expectancy, care goals, and personal preferences [29]. An enlarging body of research has demonstrated the feasibility, safety and patient benefit of deprescribing, as discussed further below. It employs evidence-based frameworks that assist the prescriber [30] and are patient-centered [31].

Importantly, deprescribing should be seen as part of the good prescribing continuum, which spans medicine initiation, titrating, changing, or adding medicines, and switching or ceasing medicines. Deprescribing is not about denying effective treatment to eligible patients. It is a positive, patient-centered intervention, with inherent uncertainties, and requires shared decision-making, informed patient consent and close monitoring of effects [32]. Deprescribing involves diagnosing a problem (use of a PIM), making a therapeutic decision (withdrawing it with close follow-up) and altering the natural history of the problem (reducing incidence of medicine-related adverse events).

Our definition of evidence-based deprescribing is a form of direct deprescribing applied at the level of the individual patient-prescriber/pharmacist encounter. Direct deprescribing uses explicit, systematic processes (such as using an algorithm or structured deprescribing framework or guide) applied by individual prescribers (or pharmacists) to the medicine regimens of individual patients (ie, at the patient level), and which targets either specific classes of medicines or all medicines that are potentially inappropriate. This is in contrast to indirect deprescribing, which uses more generic, programmatic strategies aimed at prescribers as a whole (ie, at the population or system level) and which seek to improve quality use of medicines in general, including both underuse and overuse of medicines. Indirect deprescribing entails a broader aim of medicines optimization in which deprescribing is a possible outcome but not necessarily the sole focus. Such strategies include pharmacist or physician medicine reviews, education programs for clinicians and/or patients, academic detailing, audit and feedback, geriatric assessment, multidisciplinary teams, prescribing restrictions, and government policies, all of which aim to reduce the overall burden of PIMs among broad groups of patients. While intuitively the 2 approaches in combination should exert synergistic effects superior to those of either by itself, this has not been studied.

Evidence For Deprescribing

Indirect Deprescribing

Overall, the research into indirect interventions has been highly heterogenous in terms of interventions and measures of medicine use. Research has often been of low to moderate quality, focused more on changes to prescribing patterns and less on clinical outcomes, been of short duration, and produced mixed results [33]. In a 2013 systematic review of 36 studies involving different interventions involving frail older patients in various settings, 22 of 26 quantitative studies reported statistically significant reductions in the proportions of medicines deemed unnecessary (defined using various criteria), ranging from 3 to 20 percentage points [34]. A more recent review of 20 trials of pharmacist-led reviews in both inpatient and outpatient settings reported a small reduction in the mean number of prescribed medicines (–0.48, 95% confidence interval [CI] –0.89 to –0.07) but no effects on mortality or readmissions, although unplanned hospitalizations were reduced in patients with heart failure [35]. A 2012 review of 10 controlled and 20 randomized studies revealed statistically significant reductions in the number of medicines in most of the controlled studies, although mixed results in the randomized studies [36]. Another 2012 review of 10 studies of different designs concluded that interventions were beneficial in reducing potentially inappropriate prescribing and medicine-related problems [37]. A 2013 review of 15 studies of academic detailing of family physicians showed a modest decline in the number of medications of certain classes such as benzodiazepines and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [38]. Another 2013 review restricted to 8 randomized trials of various interventions involving nursing home patients suggested medicine-related problems were more frequently identified and resolved, together with improvement in medicine appropriateness [39]. In 2 randomized trials conducted in aged care facilities and centered on educational interventions, one aimed at prescribers [40] and the other at nursing staff [41],the number of potentially harmful medicines and days in hospital was significantly reduced [40,41], combined with slower declines in health-related quality of life [40]. In a randomized trial, patient education provided through community pharmacists led to a 77% reduction in benzodiazepine use among chronic users at 6 months with no withdrawal seizures or other ill effects [42].

Direct Deprescribing Targeting Specific Classes of Medicines

The evidence base for direct patient-level deprescribing is more rigorous as it pertains to specific classes of medicines. A 2008 systematic review of 31 trials (15 randomized, 16 observational) that withdrew a single class of medicine in older people demonstrated that, with appropriate patient selection and education coupled with careful withdrawal and close monitoring, antihypertensive agents, psychotropic medicines, and benzodiazepines could be discontinued without harm in 20% to 100% of patients, although psychotropics showed a high post-trial rate of recommencement [43]. Another review of 9 randomized trials demonstrated the safety of withdrawing antipsychotic agents that had been used continuously for behavioural and psychological symptoms in more than 80% of subjects with dementia [44]. In an observational study, cessation of inappropriate antihypertensives was associated with fewer cardiovascular events and deaths over a 5-year follow-up period [45]. A recent randomized trial of statin withdrawal in patients with advanced illness and of whom half had a prognosis of less than 12 months demonstrated improved quality of life and no increased risk of cardiovascular events over the following 60 days [46].

Direct Deprescribing Targeting All Medicines

The evidence base for direct patient-level deprescribing that assesses all medicines, not just specific medicine classes, features several high-quality observational studies and controlled trials, and subgroup findings from a recent comprehensive systematic review. In this review of 132 studies, which included 56 randomized controlled trials [47], mortality was shown in randomized trials to be decreased by 38% as a result of direct (ie, patient-level) deprescribing interventions. However, this effect was not seen in studies of indirect deprescribing comprising mainly generic educational interventions. While space prevents a detailed analysis of all relevant trials, some of the more commonly cited sentinel studies are mentioned here.

In a controlled trial involving 190 patients in aged care facilities, a structured approach to deprescribing (Good Palliative–Geriatric Practice algorithm) resulted in 63% of patients having, on average, 2.8 medicines per patient discontinued, and was associated with a halving in both annual mortality and referrals to acute care hospitals [48]. In another prospective uncontrolled study, the same approach applied to a cohort of 70 community-dwelling older patients resulted in an average of 4.4 medicines prescribed to 64 patients being recommended for discontinuation, of which 81% were successfully discontinued, with 88% of patients reporting global improvements in health [49]. In a prospective cohort study of 50 older hospitalized patients receiving a median of 10 regular medicines on admission, a formal deprescribing process led to the cessation of just over 1 in 3 medicines by discharge, representing 4 fewer medicines per patient [50]. During a median follow-up period of just over 2.5 months for 39 patients, less than 5% of ceased medicines were recommenced in 3 patients for relapsing symptoms, with no deaths or acute presentations to hospital attributable to cessation of medicines. A multidisciplinary hospital clinic for older patients over a 3-month period achieved cessation of 22% of medicines in 17 patients without ill effect [51].

Two randomized studies used the Screening Tool of Older People’s Prescriptions (STOPP) to reduce the use of PIMs in older hospital inpatients [52,53]. One reported significantly reduced PIMs use in the intervention group at discharge and 6 months post-discharge, no change in the rate of hospital readmission, and non-significant reductions in falls, all cause-mortality, and primary care visits during the 6-month follow-up period [52]. The second study reported reduced PIMs use in the intervention group of frail older patients on discharge, although the proportion of people prescribed at least 1 PIM was not altered [53].

Recently, a randomized trial of a deprescribing intervention applied to aged care residents resulted in successful discontinuation of 207 (59%) of 348 medicines targeted for deprescribing, and a mean reduction of 2 medicines per patient at 12 months compared to none in controls, with no differences in mortality or hospital admissions [54]. The evidence for direct deprescribing is limited by relatively few high-quality randomized trials, small patient samples, short duration of follow-up, selection of specific subsets of patients, and the absence of comprehensive re-prescribing data and clinical outcomes.

Methods Used for Direct Deprescribing

At the level of individual patient care, various instruments have been developed to assist the deprescribing process. Screening tools or criteria such as the Beers criteria and STOPP tool help identify medicines more likely than not to be inappropriate for a given set of circumstances and are widely used by research pharmacists. Deprescribing guidelines directed at particular medications (or drug classes) [55], or specific patient populations [56], can identify clinical scenarios where a particular drug is likely to be inappropriate, and how to safely wean or discontinue it.

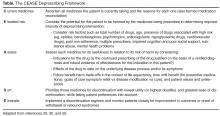

In applying a more nuanced, patient-centered approach to deprescribing, structured guides comprising algorithms, flowcharts, or tables describe sequential steps in deciding which medications used by an individual patient should be targeted for discontinuation after due attention to all relevant factors. Such guides prompt a more systematic appraisal of all medications being used. In a recent review of 7 structured guides that had undergone some form of efficacy testing [59], the strongest evidence of efficacy and clinician acceptability was seen for the Good Palliative–Geriatric Practice algorithm [48] (Figure) and the CEASE protocol [29,30,50,60] (Table). Both have been subject to a process of development and refinement over months to years involving multiple clinician prescribers and pharmacists.

Clinical Circumstances Conducive to Deprescribing

Deprescribing should be especially considered in any older patient presenting with a new symptom or clinical syndrome suggestive of adverse medicine effects. The advent of advanced or end-stage disease, terminal illness, dementia, extreme frailty, or full dependence on others for all cares marks a stage of a person’s life when limited life expectancy and changed goals of care call for a re-appraisal of the benefits of current medicines. Lack of response in controlling symptoms despite optimal adherence and dosing or conversely the absence of symptoms for long periods of time should challenge the need for ongoing regular use of medicines. Similarly, the lack of verification, or indeed repudiation, of past diagnostic labels which gave rise to indications for medicines in the first place should prompt consideration of discontinuation. Patients receiving single medicines or combinations of medicines, both of which are high risk, should attract attention [63], as should use of preventive medicines for scenarios associated with no increased disease risk despite medicine cessation (eg, ceasing alendronate after 5 years of treatment results in no increase in osteoporotic fracture risk over the ensuing 5 years [64]; ceasing statins for primary prevention after a prolonged period results in no increase in cardiovascular events 8 years after discontinuation [65]). Evidence that has emerged that strongly contradicts previously held beliefs as to the indications for certain medicines (eg, aspirin as primary prevention of cardiovascular disease) should lead to a higher frequency of their discontinuation. Finally, medicines which impose demands on patients which they deem intolerable in terms of dietary and lifestyle restrictions, adverse side effects, medicine monitoring (such as warfarin), financial cost, or any other reason likely to result in nonadherence, should be considered candidates for deprescribing [25].

Barriers to Deprescribing

The most effective strategy to reducing potentially inappropriate polypharmacy is for doctors to prescribe and patients to consume fewer medicines. Unfortunately, both doctors and patients often lack confidence about when and how to cease medicines [66–69]. In a recent systematic review comprised mostly of studies involving general practitioners in primary care [66], 4 themes emerged. First, prescribers may be unaware of their own instances of inappropriate prescribing in older people until this is pointed out to them. Poor insight may be attributable in part to insufficient education in geriatric pharmacology. Second, clinical inertia manifesting as failure to act despite an awareness of PIMs may arise from deprescribing being viewed as a risky affair [70], with doctors fearful of provoking withdrawal syndromes or disease complications, and damaging their reputation and relationships with patients or colleagues in the process. Continuing inappropriate medicines is reinforced by prescriber beliefs that to do so is a safer or kinder course of action for the patient. Third, self-perceptions of being ill-equipped, in terms of the necessary knowledge and skills, to deprescribe appropriately (lack of self-efficacy) may be a barrier, even if one accepts the need for deprescribing. Information deficits around benefit-harm trade-offs of particular drugs and alternative treatments (both drug and non-drug), especially for older, frail, multi-morbid patients, contribute to the problem. Confidence to deprescribe is further undermined by the lack of clear documentation regarding reasons drugs were originally prescribed by other doctors, outcomes of past trials of discontinuation, and current patient care goals. Fourth, several external or logistical constraints may hamper deprescribing efforts such as perceived patient unwillingness to deprescribe certain medicines, lack of prescriber time, poor remuneration, and community and professional attitudes toward more rather than less use of medicines.

Deprescribing in hospital settings led by specialists appears to be no better than in general practice, although it has been less well studied. While an episode of acute inpatient care may afford an opportunity to review and reduce medicine lists, studies suggest the opposite occurs. In a New Zealand audit of 424 patients of mean age 80 years admitted acutely to a medical unit, chronically administered medications increased during hospital stay from a mean of 6.6 to 7.7 [71]. Similarly, in an Australian study investigating medication changes for 1220 patients of mean age 81 years admitted to general medical units of 11 acute care hospitals, the mean number of regularly administered medications rose from 7.1 on admission to 7.6 at discharge [72]. It is likely the same drivers behind failure to deprescribe in primary care also operate in secondary and tertiary care settings. Part of the problem is under-recognition of medicine-related geriatric syndromes on the part of hospital physicians and pharmacists [73].

Patients in both the community and residential aged care facilities frequently express a desire to have their medicines reduced in number, especially if advised by their treating clinician [74,75]. Having said this, many remain wary of discontinuing specific medicines [67], sharing the same fears of evoking withdrawal syndromes or disease relapse as do prescribers, and recounting the strong advice of past specialists to never withhold any medicines without first seeking their advice.

A challenge for all involved in deprescribing is gaining agreement on what are the most important factors that determine when, how, and in whom deprescribing should be conducted. Recent qualitative studies suggest that doctors, pharmacists, nursing staff, and patients and their families, while in broad agreement that deprescribing is worthwhile, often differ in their perspectives on what takes priority in selecting medicines for deprescribing in individual patients, and how it should be done and by whom [76,77].

Strategies That May Facilitate Deprescribing

While deprescribing presents some challenges, there are several strategies that can facilitate it at both the level of individual clinical encounters and at the level of whole populations and systems of care.

Individual Clinical Encounters

Within individual clinician–patient encounters, patients should be empowered to ask their doctors and pharmacists the following questions:

- What are my treatment options (including non-medicine options) for my condition?

- What are the possible benefits and harms of each medicine?

- What might be reasonable grounds for stopping a medicine?

In turn, doctors and pharmacists should ask in a nonjudgmental fashion, at every encounter, whether patients are experiencing any side effects, administration and monitoring problems, or other barriers to adherence associated with any of their medicines.

The issue of deprescribing should be framed as an attempt to alleviate symptoms (of drug toxicity), improve quality of life (from drug-induced disability), and lessen the risk of morbid events (especially ADEs) in the future. Compelling evidence that identifies circumstances in which medicines can be safely withdrawn while reducing the risk of ADEs needs to be emphasized. Specialists must play a sentinel leadership role in advising and authorizing other health professionals to deprescribe in situations where benefits of medications they have prescribed are no longer outweighed by the harms [60,78].

In language they can understand, patients should be informed of the benefit–harm trade-offs specific to them of continuing or discontinuing a particular medicine, as far as these can be specified. Patients often overestimate the benefits and underestimate the harms of treatments [79]. Providing such personalised information can substantially alter perceptions of risk and change attitudes towards discontinuation [80]. Eliciting patients’ beliefs about the necessity for each individual medicine and spending time, using an empathic manner, to dispel or qualify those at odds with evidence and clinical judgement renders deprescribing more acceptable to patients.

In estimating treatment benefit–harm trade-offs in individual patients, disease risk prediction tools (http://www.medal.org/), evidence tables [81,82], and decision aids are increasingly available. Prognostication tools (http://eprognosis.ucsf.edu) combined with trial-based time-to-event data can be used to determine if medicine-specific time until benefit exceeds remaining life span.

Deprescribing is best performed by reducing medicines one at a time over several encounters with the same overseeing generalist clinician with whom patients have established a trusting and collaborative relationship. This provides repeated opportunities to discuss and assuage any fears of discontinuing a medicine, and to adjust the deprescribing plan according to changes in clinical circumstances and revised treatment goals. Practice-based pharmacists can review patients’ medicine lists and apply screening criteria to identify medicines more likely to be unnecessary or harmful, which then helps initiate and guide deprescribing. Integrating a structured deprescribing protocol—and reminders to use it—into electronic health records, and providing decision support and data collection for future reference, reduce the cognitive burden on prescribers [83]. Practical guidance in how to safely wean and cease particular classes of medicines in older people can be accessed from various sources [84,85]. Seeking input from clinical pharmacologists, pharmacists, nurses, and other salient care providers on a case-by-case basis in the form of interactive case conferences provides support, seeks consensus, and shares the risk and responsibility for deprescribing recommendations [86].

System of Care

The success of deprescribing efforts in realizing better population health will be compromised unless all key stakeholders involved in quality use of medicines commit to operationalizing deprescribing strategies at the system of care level. Position statements on deprescribing in multi-morbid populations should be formulated and promulgated by all professional societies of prescribers (primary care, specialists, pharmacists, dentists, nurse practitioners). Professional development programs as well as undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate courses in medicine, pharmacy, and nursing should include training in deprescribing as a core curricular element.

Researchers seeking funding and/or ethics approval for research projects involving medicines should be required to collect, analyze, and report data on the frequency of, and reasons for, withdrawal of drugs in trial subjects. This helps build the evidence base of medicine-related harm. In turn, government funders of research should require more researchers to design and conduct clinical trials that recruit multi-morbid patients, including specific subgroups (eg, patients with dementia), and aim to define medicine benefits and harms using patient risk stratification methods. Pharmaceutical companies should sponsor research on how to deprescribe their medicines within trials that also aim to assess efficacy and safety. Medicine regulatory authorities such as the Food and Drug Administration should mandate that this information be supplied at the time the company submits their application to have the medicine approved and listed for public subsidy. Trialists should adopt the word “deprescribing” in abstract titles for research on prescriber-initiated medicine discontinuation so that relevant articles can be more accurately indexed in, and retrieved from, bibliographic databases using recently formulated medical subject headings in Medline (“depresciptions”).

Editors of medical journals should promote a deprescribing agenda as a quality and safety issue for patient care, with the “Less is More” series in JAMA Internal Medicine and “Too much medicine” series in BMJ being good examples. Clinical guideline developers should formulate treatment recommendations specific to the needs of multi-morbid patients which acknowledge the limited evidence base for many medicines in such populations. These should take account of commonly encountered clinical scenarios where disease-specific medicines may engender greater risk of harm, and provide cautionary notes regarding initiation and discontinuation of medicines associated with high-risk.

Pharmacists need to instruct patients in how to identify medicine-induced harm and side effects, and how to collaborate with their prescribing clinicians in safely discontinuing high-risk medicines. Ideally, patients being admitted to residential aged care facilities should have their medicine lists reviewed by a pharmacist in flagging medicines eligible for deprescribing. Organizations and services responsible for providing quality use of medicines information (medicines handbooks, prescribing guidelines, drug safety bulletins) should describe when and how deprescribing should be performed in regards to specific medicines. This information should be cross-referenced to clinical guidelines and position statements dealing with the same medicine. Vendors of medicine prescribing software should be encouraged to incorporate flags and alerts which prompt prescribers to consider medicine cessation in high-risk patients.

Government and statutory bodies with responsibility for health care (health departments, quality and safety commissions, practice accreditation services, health care standard–setting bodies) should fund more research to develop and evaluate medicine safety standards aimed at reducing inappropriate use of medicines. Accreditation procedures for hospitals and primary care organizations should mandate the adoption of professional development and quality measurement systems that support and monitor patients receiving multiple medicines. Organizations responsible for conducting pharmacovigilance studies should issue medicine-specific deprescribing alerts whenever their data suggest higher than expected incidence of medicine-related adverse events in older populations receiving such medicines.

Conclusion

Inappropriate medicine use and polypharmacy is a growing issue among older and multi-morbid patients. The cumulative evidence of the safety and benefits of deprescribing argues for its adoption on the part of all prescribers, as well as its support by pharmacists and others responsible for optimizing use of medicines. Widespread implementation within routine care of an evidence-based approach to deprescribing in all patients receiving polypharmacy has its challenges, but also considerable potential to relieve unnecessary suffering and disability. More high quality research is needed in defining the circumstances under which deprescribing confers maximal benefit in terms of improved clinical outcomes.

Corresponding author: Ian A. Scott, Dept. of Internal Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Australia 4102, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Qato DM, Alexander GC, Conti RM, et . Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. JAMA 2008;300:2867–78.

2. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, et al. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA 2015;314:1818–31.

3. Wise J. Polypharmacy: a necessary evil. BMJ 2013;347: f7033.

4. Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:989–95.

5. Atkin PA, Veitch PC, Veitch EM, Ogle SJ. The epidemiology of serious adverse drug reactions among the elderly. Medicines Aging 1999;14:141–52.

6. Roughead EE, Anderson B, Gilbert AL. Potentially inappropriate prescribing among Australian veterans and war widows/widowers. Intern Med J 2007;37:402–5.

7. Stafford AC, Alswayan MS, Tenni PC. Inappropriate prescribing in older residents of Australian care homes. Clin Pharmacol Therapeut 2011;36:33–44.

8. Tjia J, Briesacher BA, Peterson D, et al. Use of medications of questionable benefit in advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1763–71.

9. Tjia J, Velten SJ, Parsons C, et al. Studies to reduce unnecessary medication use in frail older adults: A systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013;30:285–307.

10. Anathhanam AS, Powis RA, Cracknell AL, Robson J. Impact of prescribed medicines on patient safety in older people. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2012;3:165–74.

11. Opondo D, Eslami S, Visscher S, et al. Inappropriateness of medication prescriptions to elderly patients in the primary care setting: a systematic review. PLoS One 2012;7(8):e43617.

12. Kalisch LM, Caughey GE, Barratt JD, et al. Prevalence of preventable medication-related hospitalizations in Australia: an opportunity to reduce harm. Int J Qual Health Care 2012;24:239–49.

13. Bero LA, Lipton HL, Bird JA. Characterisation of geriatric drug-related hospital readmissions. Med Care 1991;29:989–1003.

14. Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Korhonen MJ, et al. Polypharmacy status as an indicator of mortality in an elderly population. Drugs Aging 2009;26:1039–48.

15. Steinman MA, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, et al. Prescribing quality in older veterans: a multifocal approach. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:1379–86.

16. Goldberg R, Mabee J, Chan L, Wong S. Drug-drug and drug-disease interactions in the ED: analysis of a high-risk population. Am J Emerg Med 1996;14:447–50.

17. Elliott RA, Booth JC. Problems with medicine use in older Australians: a review of recent literature. J Pharm Pract Res 2014;44:258–71.

18. Barat I, Andreasen F, Damsgaard EM. Drug therapy in the elderly: what doctors believe and patients actually do. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001;51:615–22.

19. Chapman RH, Benner JS, Petrilla AA, et al. Predictors of adherence with antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapy. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1147–52.

20. Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events. N Engl J Med 2012;366:859.

21. Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, Naganathan V, Waite L, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:989–95.

22. Cherubini A, Oristrell J, Pla X, et al. The persistent exclusion of older patients from ongoing clinical trials regarding heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:550–6.

23. Bugeja G, Kumar A, Banerjee AK. Exclusion of elderly people from clinical research: a descriptive study of published reports. BMJ 1997;315:1059.

24. Mangin D, Heath I, Jamoulle M. Beyond diagnosis: rising to the multimorbidity challenge. BMJ 2012;344:e3526.

25. Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA 2005;294:716–24.

26. McLean AJ, Le Couteur DG. Aging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev 2004;56:163–84.

27. Hilmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, et al. Drug Burden Index score and functional decline in older people. Am J Med 2009;122:1142–9.

28. Reeve E, Gnjidic D, Long J, Hilmer S. A systematic review of the emerging definition of ‘deprescribing’ with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;80:1254–68.

29. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy – the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:827–34.

30. Scott IA, Gray LA, Martin JH, et al. Deciding when to stop: towards evidence-based deprescribing of drugs in older populations. Evidence-based Med 2013;18:121–4.

31. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;78:738–47.

32. Alldred D. Deprescribing: a brave new word? Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22:2–3.

33. Kaur S, Mitchell G, Vitetta L, Roberts MS. Interventions that can reduce inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2009;26:1013–28.

34. Tjia J, Velten SJ, Parsons C, et al. Studies to reduce unnecessary medication use in frail older adults: A systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013;30:285–307.

35. Thomas R, Huntley AL, Mann M, et al. Pharmacist-led interventions to reduce unplanned admissions for older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Age Ageing 2014;43:174–87.

36. Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Kouladjian L, Hilmer SN. Deprescribing trials: Methods to reduce polypharmacy and the impact on prescribing and clinical outcomes. Clin Geriatr Med 2012;28:237–53.

37. Patterson SM, Hughes C, Kerse N, et al. Interventions to improve use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;5:CD008165.

38. Chhina HK, Bhole VM, Goldsmith C, et al. Effectiveness of academic detailing to optimize medication prescribing behaviour of family physicians. J Pharm Pharm Sci 2013;16:511–29.

39. Alldred DP, Raynor DK, Hughes C, et al. Interventions to optimise prescribing for older people in care homes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;CD009095.

40. García-Gollarte F, Baleriola-Júlvez J, Ferrero-López I, et al. An educational intervention on drug use in nursing homes improves health outcomes and resource utilization and reduces inappropriate drug prescription. J Am Dir Assoc 2014;15:885–91.

41. Pitkälä KH, Juola A-L, Kautiainen H, Soini H, et al. Education to reduce potentially harmful medication use among residents of assisted living facilities: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Dir Assoc 2014;15:892–8.

42. Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, et al. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education. The EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:890–8.

43. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, Le Couteur DG. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2008;25:1021–31.

44. Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic medicines for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;3:CD007726.

45. Ekbom T, Lindholm LH, Odén A, et al. A 5-year prospective, observational study of the withdrawal of antihypertensive treatment in elderly people. J Intern Med 1994;235:581–588.

46. Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH Jr, et al. Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life-limiting illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:691–700.

47. Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, Schwartz D, Etherton-Beer CD. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016 Apr 14. [Epub ahead of print]

48. Garfinkel D, Zur-Gil S, Ben-Israel J. The war against polypharmacy: a new cost-effective geriatric-palliative approach for improving drug therapy in disabled elderly people. Isr Med Assoc J 2007;9:430–4.

49. Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medicines in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1648–54.

50. McKean M, Pillans P, Scott IA. A medication review and deprescribing method for hospitalised older patients receiving multiple medications. Intern Med J 2016;46:35–42.

51. Mudge A, Radnedge K, Kasper K, et al. Effects of a pilot multidisciplinary clinic for frequent attending elderly patients on deprescribing. Aust Health Rev 2015; Jul 6. [Epub ahead of print]

52. Gallagher PF, O’Connor MN, O’Mahony D. Prevention of potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly Patients: A randomized controlled trial using STOPP/START criteria. Clin Pharmacol Therap 2011;89:845–54.

53. Dalleur O, Boland B, Losseau C, et al. Reduction of potentially inappropriate medications using the STOPP criteria in frail older inpatients: a randomised controlled study. Drugs Aging 2014;31:291–8.

54. Potter K, Flicker L, Page A, Etherton-Beer C. Deprescribing in frail older people: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2016;11(3):e0149984.

55. Conklin J, Farrell B, Ward N, et al. Developmental evaluation as a strategy to enhance the uptake and use of deprescribing guidelines: protocol for a multiple case study. Implement Sci 2015;10:91–101.

56. Lindsay J, Dooley M, Martin J, et al. The development and evaluation of an oncological palliative care deprescribing guideline: the ‘OncPal deprescribing guideline’ Support Care Cancer 2015;23:71–8.

57. Miller GC, Valenti L, Britt H, Bayram C. Drugs causing adverse events in patients aged 45 or older: a randomised survey of Australian general practice patients. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003701.

58. Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shebab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalisations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2002–12.

59. Scott IA, Andersen K, Freeman C. Review of structured guides for deprescribing. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2016. In press.

60. Scott IA, Le Couteur D. Physicians need to take the lead in deprescribing. Intern Med J 2015;45:352–6.

61. Poudel A, Ballokova A, Hubbard RE, et al. An algorithm of medication review in residential aged care facilities: focus on minimizing use of high risk medications. Geriatr Gerontol Int Sep 3. [Epub ahead of print]

62. Scott IA, Martin JH, Gray LA, Mitchell CA. Effects of a drug minimisation guide on prescribing intentions in elderly persons with polypharmacy. Drugs Ageing 2012;29:659–67.

63. Bennett A, Gnjidic D, Gillett M, et al. Prevalence and impact of fall-risk-increasing drugs, polypharmacy, and drug-drug interactions in robust versus frail hospitalised falls patients: a prospective cohort study. Drugs Aging 2014;31:225–32.

64. Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al. FLEX Research Group. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomised trial. JAMA 2006;296:2927–38.

65. Sever PS, Chang CL, Gupta AK, et al. The Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial: 11-year mortality follow-up of the lipid lowering arm in the UK. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2525–32.

66. Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, Scott I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open 2014;4.

67. Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, et al. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013;30:793–807.

68. Palagyi A, Keay L, Harper J, et al. Barricades and brickwalls—a qualitative study exploring perceptions of medication use and deprescribing in long-term care. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:15.

69. Garfinkel D, Ilhan B, Bahat G. Routine deprescribing of chronic medications to combat polypharmacy. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2015;6:212–33.

70. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. The benefits and harms of deprescribing. Med J Aust 2014;201:386–9.

71. Betteridge TM, Frampton CM, Jardine DL. Polypharmacy – we make it worse! A cross-sectional study from an acute admissions unit. Intern Med J 2012;42:208–11.

72. Hubbard RE, Peel NM, Scott IA, et al. Polypharmacy among inpatients aged 70 years or older in Australia. Med J Aust 2015;202:373–7.

73. Klopotowska JE, Wierenga PC, Smorenburg SM, et al. Recognition of adverse drug events in older hospitalized medical patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013;69:75–85.

74. Reeve E, Wiese MD, Hendrix I, et al. People’s attitudes, beliefs, and experiences regarding polypharmacy and willingness to deprescribe. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1508–14.

75. Kalogianis MJ, Wimmer BC, Turner JP, et al. Are residents of aged care facilities willing to have their medications deprescribed? Res Social Adm Pharm 2015. Published online 18 Dec 2015.

76. Turner JP, Edwards S, Stanners M, et al. What factors are important for deprescribing in Australian long-term care facilities? Perspectives of residents and health professionals. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009781.

77. Page AT, Etherton-Beer CD, Clifford RM, et al. Deprescribing in frail older people - Do doctors and pharmacists agree? Res Social Adm Pharm 2015;12:438–49.

78. Luymes CH, van der Kleij RM, Poortvliet RK, et al. Deprescribing potentially inappropriate preventive cardiovascular medication: Barriers and enablers for patients and general practitioners. Ann Pharmacother 2016 Mar 3. [Epub ahead of print]

79. Hoffmann TC, Del Mar C. Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:274–86.

80. Martin P, Tamblyn R, Ahmed S, Tannenbaum C. A drug education tool developed for older adults changes knowledge, beliefs and risk perceptions about inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions in the elderly. Patient Educ Couns 2013;92:81–7.

81. Hamilton H, Gallagher P, Ryan C, et al. Potentially inappropriate medicines defined by STOPP criteria and the risk of adverse drug events in older hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1013–7.

82. NHS Highland. Polypharmacy: guidance for prescribing in frail adults. Accessed at: www.nhshighland.scot.nhs.uk/publications/documents/guidelines/polypharmacy guidance for prescribing in frail adults.pdf.

83. Anderson K, Foster MM, Freeman CR, Scott IA. A multifaceted intervention to reduce inappropriate polypharmacy in primary care: research co-creation opportunities in a pilot study. Med J Aust 2016;204:S41–4.

84. A practical guide to stopping medicines in older people. Accessed at: www.bpac.org.nz/magazine/2010/april/stopGuide.asp.

85. www.cpsedu.com.au/posts/view/46/Deprescribing-Documents-now-Available-for-Download.

86. Bregnhøj L, Thirstrup S, Kristensen MB, et al. Combined intervention programme reduces inappropriate prescribing in elderly patients exposed to polypharmacy in primary care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2009;65:199–207.

From the Department of Internal Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Ipswich Road, Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia (Dr. Scott), School of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Herston Road, Brisbane, Australia (Dr. Scott), Centre of Research Excellence in Quality & Safety in Integrated Primary-Secondary Care, The University of Queensland, Herston Road, Brisbane, Australia (Ms. Anderson), and Charming Institute, Camp Hill, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia (Dr. Freeman).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the adverse drug events (ADEs) risk of polypharmacy; the process of deprescribing and evidence of efficacy in reducing inappropriate polypharmacy; the enablers and barriers to deprescribing; and patient and system of care level strategies that can be employed to enhance deprescribing.

- Methods: Literature review.

- Results: Inappropriate polypharmacy, especially in older people, imposes a significant burden of ADEs, ill health, disability, hospitalization and even death. The single most important predictor of inappropriate prescribing and risk of ADEs in older patients is the number of prescribed medicines. Deprescribing is the process of systematically reviewing, identifying, and discontinuing potentially inappropriate medicines (PIMs), aimed at minimizing polypharmacy and improving patient outcomes. Evidence of efficacy for deprescribing is emerging from randomized trials and observational studies, and deprescribing protocols have been developed and validated for clinical use. Barriers and enablers to deprescribing by individual prescribers center on 4 themes: (1) raising awareness of the prevalence and characteristics of PIMs; (2) overcoming clinical inertia whereby discontinuing medicines is seen as being a low value proposition compared to maintaining the status quo; (3) increasing skills and competence (self-efficacy) in deprescribing; and (4) countering external and logistical factors that impede the process.

- Conclusion: In optimizing the scale and effects of deprescribing in clinical practice, strategies that promote depresribing will need to be applied at both the level of individual patient–prescriber encounters and systems of care.

In developed countries in the modern era, about 30% of patients aged 65 years or older are prescribed 5 or more medicines [1]. Over the past decade, the prevalence of polypharmacy (use of > 5 prescription drugs) in the adult population of the United States has doubled from 8.2% in 1999–2000 to 15% in 2011–2012 [2]. While many patients may benefit from such polypharmacy [3] (defined here as 5 or more regularly prescribed medicines), it comes with increased risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) in older people [4] due to physiological changes of aging that alter pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic responses to medicines [5]. Approximately 1 in 5 medicines commonly used in older people may be inappropriate [6], rising to a third among those living in residential aged care facilities [7]. Among nursing home residents with advanced dementia, more than half receive at least 1 medicine with questionable benefit [8]. Approximately 50% of hospitalized nursing home or ambulatory care patients receive 1 or more unnecessary medicines [9]. Observational studies have documented ADEs in at least 15% of older patients, contributing to ill health [10], disability [11], hospitalization [12] and readmissions [13], increased length of stay, and, in some cases, death [14]. This high level of iatrogenic harm from potentially inappropriate medicines (PIMs) mandates a response from clinicians responsible for managing medicines.

In this narrative review, we aim to detail the ADE risk of polypharmacy, the process of deprescribing and evidence of its efficacy in reducing potentially inappropriate polypharmacy, the enablers and barriers to deprescribing, and patient and system of care level strategies that can be employed in enhancing deprescribing.

Polypharmacy As a Risk Factor for Medicine-Related Harm

The number of medicines a patient is taking is the single most important predictor of medicine-related harm [15]. One report estimated the risk of ADEs as a contributory cause of patients presenting acutely to hospital emergency departments to be 13% for 2 drugs, 38% for 4 drugs, and 82% for 7 drugs or more [16]. The more medicines an individual takes, the greater their risk of experiencing an adverse drug reaction, a drug-drug interaction, a drug-disease interaction, cascade prescribing (where more medicines are added to counteract side effects of existing medicines), nonadherence, and drug errors (wrong drug, wrong dose, missed doses, erroneous dosing frequency) [17–20]. Once the number of regular medicines rises above 5 (commonly regarded as the threshold for defining polypharmacy), observational data suggest that additional medicines independently increase the risk of frailty, falling, and hospital admission [21].

The benefits of many medicines in frail older people remain unquantified. As many as 50% of clinical trials have a specific upper age limit and approximately 80% of clinical trials exclude people with comorbidities [22,23]. Single-disease treatment guidelines based on such trials are often extrapolated to older people with multimorbidity despite an absence of evidence for benefit [24] and with little consideration of the potential burdens and harms of polypharmacy resulting from treating multiple diseases in the one patient [25]. By contrast, the risks from many medicines in older people are well known. Older people are at high risk of ADEs and toxicity due to reduced renal and liver function and age-related changes in physiological reserve, body composition, and cellular metabolism [26]. While the adverse effects of polypharmacy or of comorbidities targeted for treatment are difficult to separate, the burden of medicine-induced decline in function and quality of life is becoming better defined and appreciated [27].

Defining Evidence-Based Deprescribing

While many definitions have been proposed [28], we define evidence-based deprescribing as follows: the active process of systematically reviewing medicines being used by individual patients and, using best available evidence, identifying and discontinuing those associated with unfavorable risk–benefit trade-offs within the context of illness severity, advanced age, multi-morbidity, physical and emotional capacity, life expectancy, care goals, and personal preferences [29]. An enlarging body of research has demonstrated the feasibility, safety and patient benefit of deprescribing, as discussed further below. It employs evidence-based frameworks that assist the prescriber [30] and are patient-centered [31].

Importantly, deprescribing should be seen as part of the good prescribing continuum, which spans medicine initiation, titrating, changing, or adding medicines, and switching or ceasing medicines. Deprescribing is not about denying effective treatment to eligible patients. It is a positive, patient-centered intervention, with inherent uncertainties, and requires shared decision-making, informed patient consent and close monitoring of effects [32]. Deprescribing involves diagnosing a problem (use of a PIM), making a therapeutic decision (withdrawing it with close follow-up) and altering the natural history of the problem (reducing incidence of medicine-related adverse events).

Our definition of evidence-based deprescribing is a form of direct deprescribing applied at the level of the individual patient-prescriber/pharmacist encounter. Direct deprescribing uses explicit, systematic processes (such as using an algorithm or structured deprescribing framework or guide) applied by individual prescribers (or pharmacists) to the medicine regimens of individual patients (ie, at the patient level), and which targets either specific classes of medicines or all medicines that are potentially inappropriate. This is in contrast to indirect deprescribing, which uses more generic, programmatic strategies aimed at prescribers as a whole (ie, at the population or system level) and which seek to improve quality use of medicines in general, including both underuse and overuse of medicines. Indirect deprescribing entails a broader aim of medicines optimization in which deprescribing is a possible outcome but not necessarily the sole focus. Such strategies include pharmacist or physician medicine reviews, education programs for clinicians and/or patients, academic detailing, audit and feedback, geriatric assessment, multidisciplinary teams, prescribing restrictions, and government policies, all of which aim to reduce the overall burden of PIMs among broad groups of patients. While intuitively the 2 approaches in combination should exert synergistic effects superior to those of either by itself, this has not been studied.

Evidence For Deprescribing

Indirect Deprescribing

Overall, the research into indirect interventions has been highly heterogenous in terms of interventions and measures of medicine use. Research has often been of low to moderate quality, focused more on changes to prescribing patterns and less on clinical outcomes, been of short duration, and produced mixed results [33]. In a 2013 systematic review of 36 studies involving different interventions involving frail older patients in various settings, 22 of 26 quantitative studies reported statistically significant reductions in the proportions of medicines deemed unnecessary (defined using various criteria), ranging from 3 to 20 percentage points [34]. A more recent review of 20 trials of pharmacist-led reviews in both inpatient and outpatient settings reported a small reduction in the mean number of prescribed medicines (–0.48, 95% confidence interval [CI] –0.89 to –0.07) but no effects on mortality or readmissions, although unplanned hospitalizations were reduced in patients with heart failure [35]. A 2012 review of 10 controlled and 20 randomized studies revealed statistically significant reductions in the number of medicines in most of the controlled studies, although mixed results in the randomized studies [36]. Another 2012 review of 10 studies of different designs concluded that interventions were beneficial in reducing potentially inappropriate prescribing and medicine-related problems [37]. A 2013 review of 15 studies of academic detailing of family physicians showed a modest decline in the number of medications of certain classes such as benzodiazepines and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [38]. Another 2013 review restricted to 8 randomized trials of various interventions involving nursing home patients suggested medicine-related problems were more frequently identified and resolved, together with improvement in medicine appropriateness [39]. In 2 randomized trials conducted in aged care facilities and centered on educational interventions, one aimed at prescribers [40] and the other at nursing staff [41],the number of potentially harmful medicines and days in hospital was significantly reduced [40,41], combined with slower declines in health-related quality of life [40]. In a randomized trial, patient education provided through community pharmacists led to a 77% reduction in benzodiazepine use among chronic users at 6 months with no withdrawal seizures or other ill effects [42].

Direct Deprescribing Targeting Specific Classes of Medicines

The evidence base for direct patient-level deprescribing is more rigorous as it pertains to specific classes of medicines. A 2008 systematic review of 31 trials (15 randomized, 16 observational) that withdrew a single class of medicine in older people demonstrated that, with appropriate patient selection and education coupled with careful withdrawal and close monitoring, antihypertensive agents, psychotropic medicines, and benzodiazepines could be discontinued without harm in 20% to 100% of patients, although psychotropics showed a high post-trial rate of recommencement [43]. Another review of 9 randomized trials demonstrated the safety of withdrawing antipsychotic agents that had been used continuously for behavioural and psychological symptoms in more than 80% of subjects with dementia [44]. In an observational study, cessation of inappropriate antihypertensives was associated with fewer cardiovascular events and deaths over a 5-year follow-up period [45]. A recent randomized trial of statin withdrawal in patients with advanced illness and of whom half had a prognosis of less than 12 months demonstrated improved quality of life and no increased risk of cardiovascular events over the following 60 days [46].

Direct Deprescribing Targeting All Medicines

The evidence base for direct patient-level deprescribing that assesses all medicines, not just specific medicine classes, features several high-quality observational studies and controlled trials, and subgroup findings from a recent comprehensive systematic review. In this review of 132 studies, which included 56 randomized controlled trials [47], mortality was shown in randomized trials to be decreased by 38% as a result of direct (ie, patient-level) deprescribing interventions. However, this effect was not seen in studies of indirect deprescribing comprising mainly generic educational interventions. While space prevents a detailed analysis of all relevant trials, some of the more commonly cited sentinel studies are mentioned here.

In a controlled trial involving 190 patients in aged care facilities, a structured approach to deprescribing (Good Palliative–Geriatric Practice algorithm) resulted in 63% of patients having, on average, 2.8 medicines per patient discontinued, and was associated with a halving in both annual mortality and referrals to acute care hospitals [48]. In another prospective uncontrolled study, the same approach applied to a cohort of 70 community-dwelling older patients resulted in an average of 4.4 medicines prescribed to 64 patients being recommended for discontinuation, of which 81% were successfully discontinued, with 88% of patients reporting global improvements in health [49]. In a prospective cohort study of 50 older hospitalized patients receiving a median of 10 regular medicines on admission, a formal deprescribing process led to the cessation of just over 1 in 3 medicines by discharge, representing 4 fewer medicines per patient [50]. During a median follow-up period of just over 2.5 months for 39 patients, less than 5% of ceased medicines were recommenced in 3 patients for relapsing symptoms, with no deaths or acute presentations to hospital attributable to cessation of medicines. A multidisciplinary hospital clinic for older patients over a 3-month period achieved cessation of 22% of medicines in 17 patients without ill effect [51].

Two randomized studies used the Screening Tool of Older People’s Prescriptions (STOPP) to reduce the use of PIMs in older hospital inpatients [52,53]. One reported significantly reduced PIMs use in the intervention group at discharge and 6 months post-discharge, no change in the rate of hospital readmission, and non-significant reductions in falls, all cause-mortality, and primary care visits during the 6-month follow-up period [52]. The second study reported reduced PIMs use in the intervention group of frail older patients on discharge, although the proportion of people prescribed at least 1 PIM was not altered [53].

Recently, a randomized trial of a deprescribing intervention applied to aged care residents resulted in successful discontinuation of 207 (59%) of 348 medicines targeted for deprescribing, and a mean reduction of 2 medicines per patient at 12 months compared to none in controls, with no differences in mortality or hospital admissions [54]. The evidence for direct deprescribing is limited by relatively few high-quality randomized trials, small patient samples, short duration of follow-up, selection of specific subsets of patients, and the absence of comprehensive re-prescribing data and clinical outcomes.

Methods Used for Direct Deprescribing

At the level of individual patient care, various instruments have been developed to assist the deprescribing process. Screening tools or criteria such as the Beers criteria and STOPP tool help identify medicines more likely than not to be inappropriate for a given set of circumstances and are widely used by research pharmacists. Deprescribing guidelines directed at particular medications (or drug classes) [55], or specific patient populations [56], can identify clinical scenarios where a particular drug is likely to be inappropriate, and how to safely wean or discontinue it.

In applying a more nuanced, patient-centered approach to deprescribing, structured guides comprising algorithms, flowcharts, or tables describe sequential steps in deciding which medications used by an individual patient should be targeted for discontinuation after due attention to all relevant factors. Such guides prompt a more systematic appraisal of all medications being used. In a recent review of 7 structured guides that had undergone some form of efficacy testing [59], the strongest evidence of efficacy and clinician acceptability was seen for the Good Palliative–Geriatric Practice algorithm [48] (Figure) and the CEASE protocol [29,30,50,60] (Table). Both have been subject to a process of development and refinement over months to years involving multiple clinician prescribers and pharmacists.

Clinical Circumstances Conducive to Deprescribing

Deprescribing should be especially considered in any older patient presenting with a new symptom or clinical syndrome suggestive of adverse medicine effects. The advent of advanced or end-stage disease, terminal illness, dementia, extreme frailty, or full dependence on others for all cares marks a stage of a person’s life when limited life expectancy and changed goals of care call for a re-appraisal of the benefits of current medicines. Lack of response in controlling symptoms despite optimal adherence and dosing or conversely the absence of symptoms for long periods of time should challenge the need for ongoing regular use of medicines. Similarly, the lack of verification, or indeed repudiation, of past diagnostic labels which gave rise to indications for medicines in the first place should prompt consideration of discontinuation. Patients receiving single medicines or combinations of medicines, both of which are high risk, should attract attention [63], as should use of preventive medicines for scenarios associated with no increased disease risk despite medicine cessation (eg, ceasing alendronate after 5 years of treatment results in no increase in osteoporotic fracture risk over the ensuing 5 years [64]; ceasing statins for primary prevention after a prolonged period results in no increase in cardiovascular events 8 years after discontinuation [65]). Evidence that has emerged that strongly contradicts previously held beliefs as to the indications for certain medicines (eg, aspirin as primary prevention of cardiovascular disease) should lead to a higher frequency of their discontinuation. Finally, medicines which impose demands on patients which they deem intolerable in terms of dietary and lifestyle restrictions, adverse side effects, medicine monitoring (such as warfarin), financial cost, or any other reason likely to result in nonadherence, should be considered candidates for deprescribing [25].

Barriers to Deprescribing

The most effective strategy to reducing potentially inappropriate polypharmacy is for doctors to prescribe and patients to consume fewer medicines. Unfortunately, both doctors and patients often lack confidence about when and how to cease medicines [66–69]. In a recent systematic review comprised mostly of studies involving general practitioners in primary care [66], 4 themes emerged. First, prescribers may be unaware of their own instances of inappropriate prescribing in older people until this is pointed out to them. Poor insight may be attributable in part to insufficient education in geriatric pharmacology. Second, clinical inertia manifesting as failure to act despite an awareness of PIMs may arise from deprescribing being viewed as a risky affair [70], with doctors fearful of provoking withdrawal syndromes or disease complications, and damaging their reputation and relationships with patients or colleagues in the process. Continuing inappropriate medicines is reinforced by prescriber beliefs that to do so is a safer or kinder course of action for the patient. Third, self-perceptions of being ill-equipped, in terms of the necessary knowledge and skills, to deprescribe appropriately (lack of self-efficacy) may be a barrier, even if one accepts the need for deprescribing. Information deficits around benefit-harm trade-offs of particular drugs and alternative treatments (both drug and non-drug), especially for older, frail, multi-morbid patients, contribute to the problem. Confidence to deprescribe is further undermined by the lack of clear documentation regarding reasons drugs were originally prescribed by other doctors, outcomes of past trials of discontinuation, and current patient care goals. Fourth, several external or logistical constraints may hamper deprescribing efforts such as perceived patient unwillingness to deprescribe certain medicines, lack of prescriber time, poor remuneration, and community and professional attitudes toward more rather than less use of medicines.

Deprescribing in hospital settings led by specialists appears to be no better than in general practice, although it has been less well studied. While an episode of acute inpatient care may afford an opportunity to review and reduce medicine lists, studies suggest the opposite occurs. In a New Zealand audit of 424 patients of mean age 80 years admitted acutely to a medical unit, chronically administered medications increased during hospital stay from a mean of 6.6 to 7.7 [71]. Similarly, in an Australian study investigating medication changes for 1220 patients of mean age 81 years admitted to general medical units of 11 acute care hospitals, the mean number of regularly administered medications rose from 7.1 on admission to 7.6 at discharge [72]. It is likely the same drivers behind failure to deprescribe in primary care also operate in secondary and tertiary care settings. Part of the problem is under-recognition of medicine-related geriatric syndromes on the part of hospital physicians and pharmacists [73].

Patients in both the community and residential aged care facilities frequently express a desire to have their medicines reduced in number, especially if advised by their treating clinician [74,75]. Having said this, many remain wary of discontinuing specific medicines [67], sharing the same fears of evoking withdrawal syndromes or disease relapse as do prescribers, and recounting the strong advice of past specialists to never withhold any medicines without first seeking their advice.

A challenge for all involved in deprescribing is gaining agreement on what are the most important factors that determine when, how, and in whom deprescribing should be conducted. Recent qualitative studies suggest that doctors, pharmacists, nursing staff, and patients and their families, while in broad agreement that deprescribing is worthwhile, often differ in their perspectives on what takes priority in selecting medicines for deprescribing in individual patients, and how it should be done and by whom [76,77].

Strategies That May Facilitate Deprescribing

While deprescribing presents some challenges, there are several strategies that can facilitate it at both the level of individual clinical encounters and at the level of whole populations and systems of care.

Individual Clinical Encounters

Within individual clinician–patient encounters, patients should be empowered to ask their doctors and pharmacists the following questions:

- What are my treatment options (including non-medicine options) for my condition?

- What are the possible benefits and harms of each medicine?

- What might be reasonable grounds for stopping a medicine?

In turn, doctors and pharmacists should ask in a nonjudgmental fashion, at every encounter, whether patients are experiencing any side effects, administration and monitoring problems, or other barriers to adherence associated with any of their medicines.

The issue of deprescribing should be framed as an attempt to alleviate symptoms (of drug toxicity), improve quality of life (from drug-induced disability), and lessen the risk of morbid events (especially ADEs) in the future. Compelling evidence that identifies circumstances in which medicines can be safely withdrawn while reducing the risk of ADEs needs to be emphasized. Specialists must play a sentinel leadership role in advising and authorizing other health professionals to deprescribe in situations where benefits of medications they have prescribed are no longer outweighed by the harms [60,78].

In language they can understand, patients should be informed of the benefit–harm trade-offs specific to them of continuing or discontinuing a particular medicine, as far as these can be specified. Patients often overestimate the benefits and underestimate the harms of treatments [79]. Providing such personalised information can substantially alter perceptions of risk and change attitudes towards discontinuation [80]. Eliciting patients’ beliefs about the necessity for each individual medicine and spending time, using an empathic manner, to dispel or qualify those at odds with evidence and clinical judgement renders deprescribing more acceptable to patients.

In estimating treatment benefit–harm trade-offs in individual patients, disease risk prediction tools (http://www.medal.org/), evidence tables [81,82], and decision aids are increasingly available. Prognostication tools (http://eprognosis.ucsf.edu) combined with trial-based time-to-event data can be used to determine if medicine-specific time until benefit exceeds remaining life span.

Deprescribing is best performed by reducing medicines one at a time over several encounters with the same overseeing generalist clinician with whom patients have established a trusting and collaborative relationship. This provides repeated opportunities to discuss and assuage any fears of discontinuing a medicine, and to adjust the deprescribing plan according to changes in clinical circumstances and revised treatment goals. Practice-based pharmacists can review patients’ medicine lists and apply screening criteria to identify medicines more likely to be unnecessary or harmful, which then helps initiate and guide deprescribing. Integrating a structured deprescribing protocol—and reminders to use it—into electronic health records, and providing decision support and data collection for future reference, reduce the cognitive burden on prescribers [83]. Practical guidance in how to safely wean and cease particular classes of medicines in older people can be accessed from various sources [84,85]. Seeking input from clinical pharmacologists, pharmacists, nurses, and other salient care providers on a case-by-case basis in the form of interactive case conferences provides support, seeks consensus, and shares the risk and responsibility for deprescribing recommendations [86].

System of Care

The success of deprescribing efforts in realizing better population health will be compromised unless all key stakeholders involved in quality use of medicines commit to operationalizing deprescribing strategies at the system of care level. Position statements on deprescribing in multi-morbid populations should be formulated and promulgated by all professional societies of prescribers (primary care, specialists, pharmacists, dentists, nurse practitioners). Professional development programs as well as undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate courses in medicine, pharmacy, and nursing should include training in deprescribing as a core curricular element.

Researchers seeking funding and/or ethics approval for research projects involving medicines should be required to collect, analyze, and report data on the frequency of, and reasons for, withdrawal of drugs in trial subjects. This helps build the evidence base of medicine-related harm. In turn, government funders of research should require more researchers to design and conduct clinical trials that recruit multi-morbid patients, including specific subgroups (eg, patients with dementia), and aim to define medicine benefits and harms using patient risk stratification methods. Pharmaceutical companies should sponsor research on how to deprescribe their medicines within trials that also aim to assess efficacy and safety. Medicine regulatory authorities such as the Food and Drug Administration should mandate that this information be supplied at the time the company submits their application to have the medicine approved and listed for public subsidy. Trialists should adopt the word “deprescribing” in abstract titles for research on prescriber-initiated medicine discontinuation so that relevant articles can be more accurately indexed in, and retrieved from, bibliographic databases using recently formulated medical subject headings in Medline (“depresciptions”).

Editors of medical journals should promote a deprescribing agenda as a quality and safety issue for patient care, with the “Less is More” series in JAMA Internal Medicine and “Too much medicine” series in BMJ being good examples. Clinical guideline developers should formulate treatment recommendations specific to the needs of multi-morbid patients which acknowledge the limited evidence base for many medicines in such populations. These should take account of commonly encountered clinical scenarios where disease-specific medicines may engender greater risk of harm, and provide cautionary notes regarding initiation and discontinuation of medicines associated with high-risk.

Pharmacists need to instruct patients in how to identify medicine-induced harm and side effects, and how to collaborate with their prescribing clinicians in safely discontinuing high-risk medicines. Ideally, patients being admitted to residential aged care facilities should have their medicine lists reviewed by a pharmacist in flagging medicines eligible for deprescribing. Organizations and services responsible for providing quality use of medicines information (medicines handbooks, prescribing guidelines, drug safety bulletins) should describe when and how deprescribing should be performed in regards to specific medicines. This information should be cross-referenced to clinical guidelines and position statements dealing with the same medicine. Vendors of medicine prescribing software should be encouraged to incorporate flags and alerts which prompt prescribers to consider medicine cessation in high-risk patients.