User login

Evaluation and Management of Female Sexual Dysfunction

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Causes of pain

- Screening

- Multimodal treatment

Care of women with sexual disorders has made great strides since Masters and Johnson began their study in 1957. In 2000, the Sexual Function Health Council of the American Foundation for Urologic Disease devised the classification system for female sexual dysfunction, which was officially defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR.1 There are now definitions for sexual desire disorders, sexual arousal disorders, orgasmic disorder, and sexual pain disorders.

Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) has complex physiologic and psychologic components that require a detailed screening, history, and physical examination. Our goal in this review is to provide primary care providers with insights and practical advice to help screen, diagnose, and treat FSD, which can have a profound impact on patients’ most intimate relationships.

UNDERSTANDING THE TYPES OF FSD

Most women consider sexual health an important part of their overall health.2 Factors that can disrupt normal sexual function include aging, socioeconomics, and other medical comorbidities. FSD is common in women throughout their lives and refers to various sexual dysfunctions including diminished arousal, problems achieving orgasm, dyspareunia, and low desire. Its prevalence is reported to be as high as 20% to 43%.3,4

The World Health Organization and the US Surgeon General have released statements encouraging health care providers to address sexual health during a patient’s annual visits.5 Unfortunately, despite this call to action, many patients and providers are initially hesitant to discuss these problems.6

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) provides the definition and diagnostic guidelines for the different components of FSD. Its classification of sexual disorders was simplified and published in May 2013.7 There are now only three female dysfunctions (as opposed to five in DSM-IV):

- Female hypoactive desire dysfunction and female arousal dysfunction were merged into a single syndrome labeled female sexual interest/arousal disorder.

- The formerly separate dyspareunia (painful intercourse) and vaginismus are now called genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder.

- Female orgasmic disorder remains as a category and is unchanged.

To qualify as a dysfunction, the problem must be present more than 75% of the time, for more than six months, causing significant distress, and must not be explained by a nonsexual mental disorder, relationship distress, substance abuse, or a medical condition.

Substance- or medication-induced sexual dysfunction falls under “Other Dysfunctions” and is defined as a clinically significant disturbance in sexual function that is predominant in the clinical picture. The criteria for substance- and medication-induced sexual dysfunction are unchanged and include neither the 75% nor the six-month requirement. The diagnosis of sexual dysfunction due to a general medical condition and sexual aversion disorder are absent from the DSM-5.7

Continue to: A common symptom

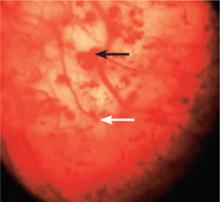

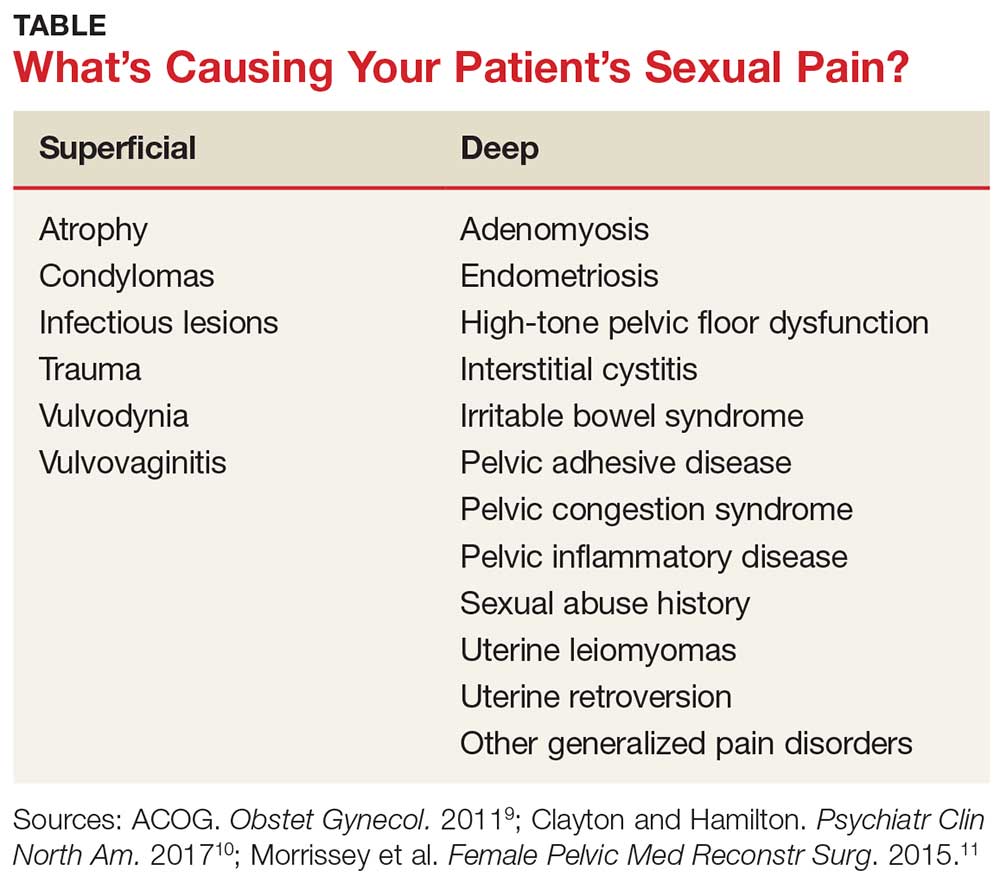

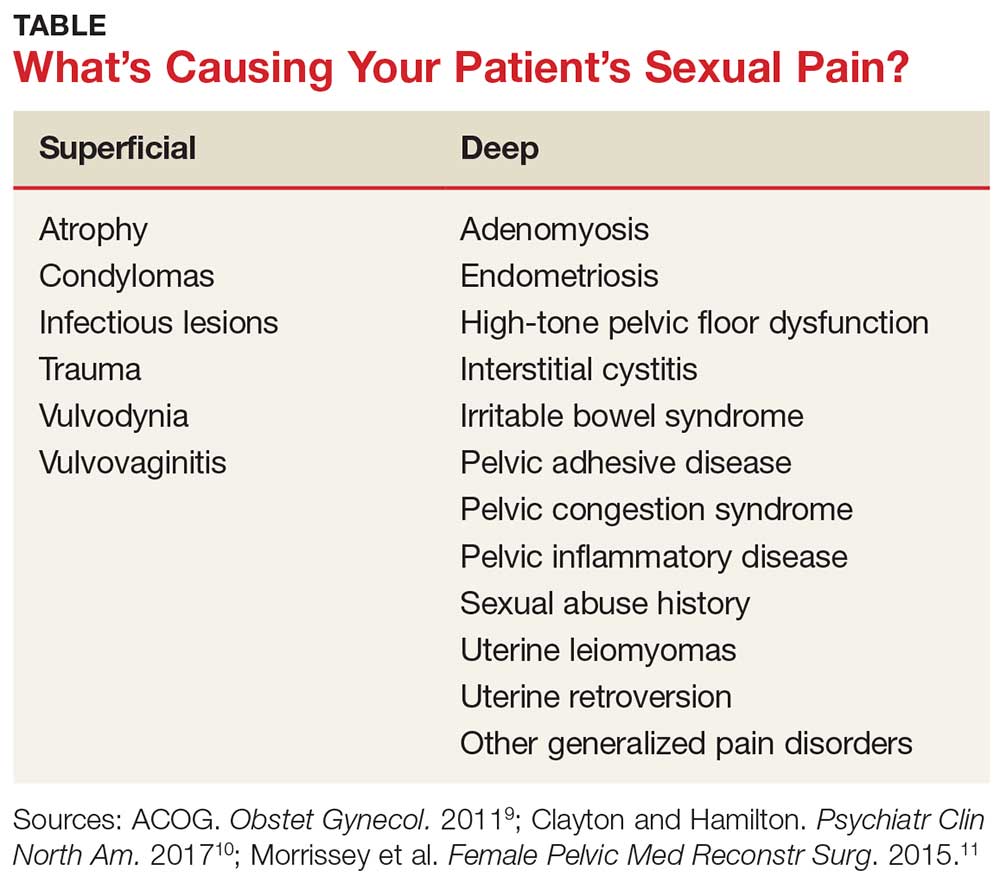

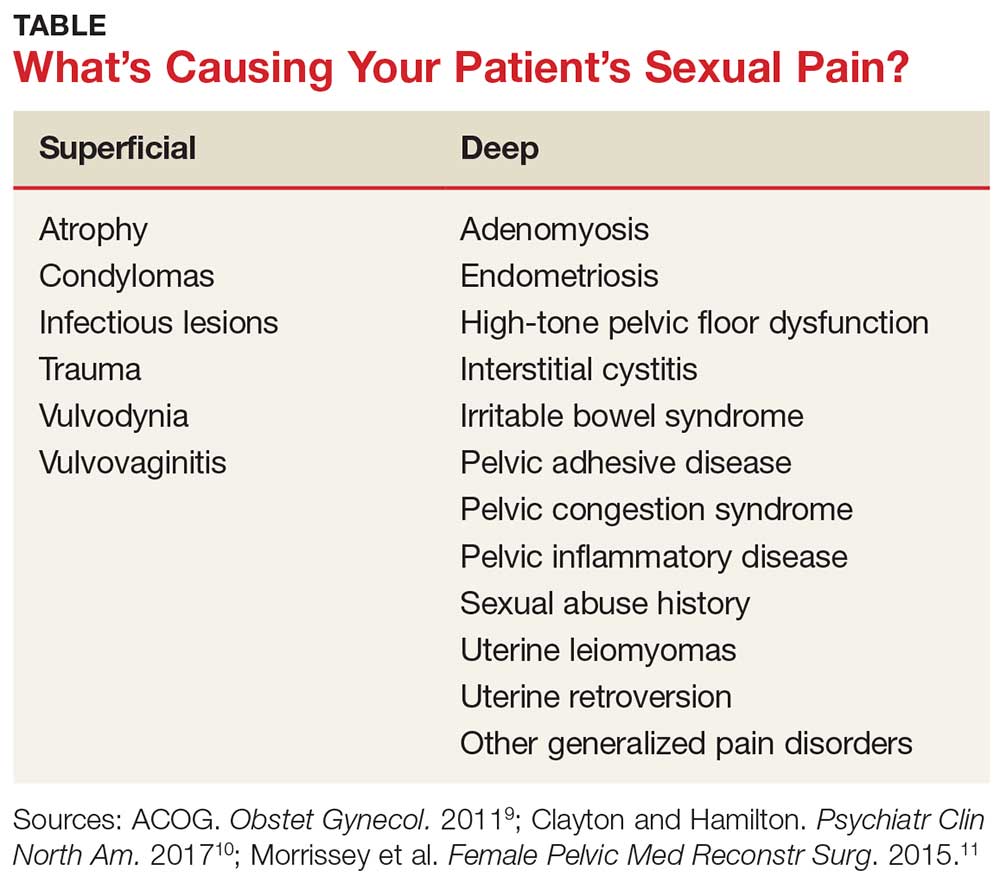

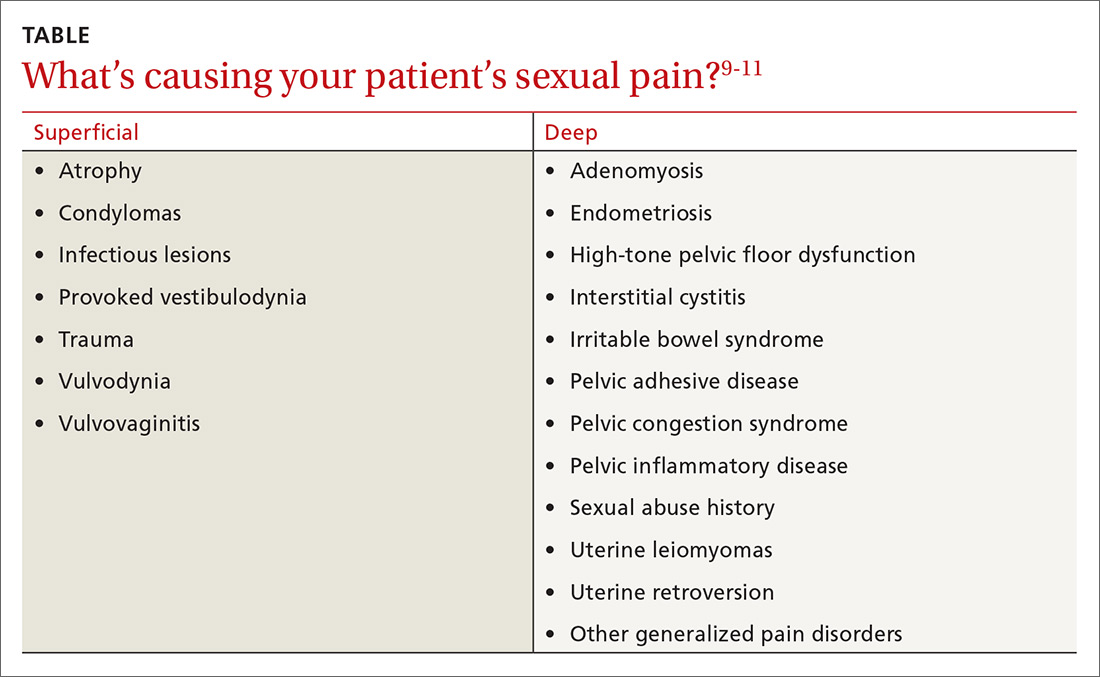

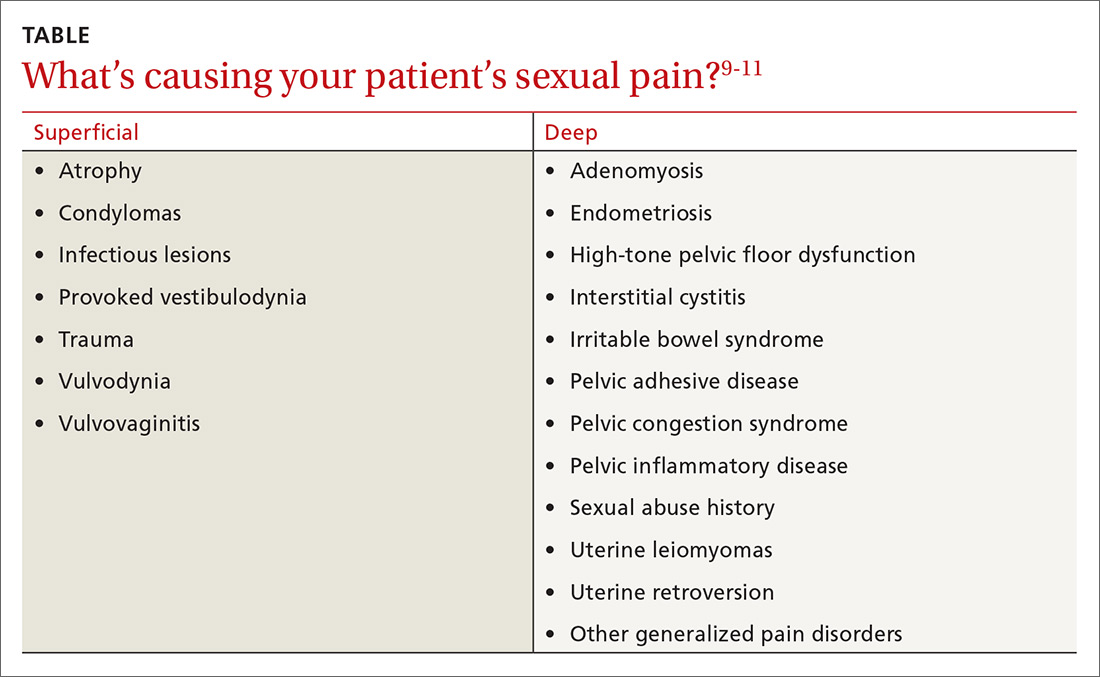

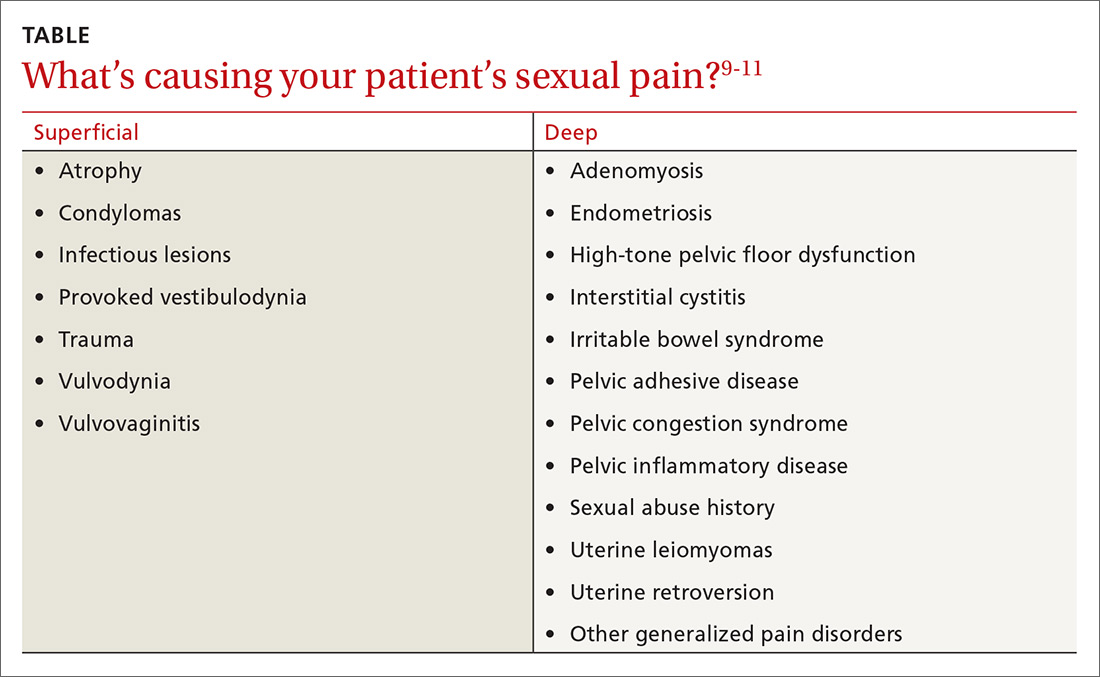

A common symptom. Female sexual disorders can be caused by several complex physiologic and psychologic factors. A common symptom among many women is dyspareunia. It is seen more often in postmenopausal women, and its prevalence ranges from 8% to 22%.8 Pain on vaginal entry usually indicates vaginal atrophy, vaginal dermatitis, or provoked vestibulodynia. Pain on deep penetration could be caused by endometriosis, interstitial cystitis, or uterine leiomyomas.9

The physical examination will reproduce the pain when the vulva or vagina is touched with a cotton swab or when you insert a finger into the vagina. The differential diagnosis is listed in the Table.9-11

EVALUATING THE PATIENT

Initially, many patients and providers may hesitate to discuss sexual dysfunction, but the annual exam is a good opportunity to broach the topic of sexual health.

Screening and history

Clinicians can screen all patients, regardless of age, with the help of a validated sex questionnaire or during a routine review of systems. There are many validated screening tools available. A simple, integrated screening tool to use is the Brief Sexual Symptom Checklist for Women (BSSC-W), created by the International Consultation on Sexual Medicine.12 Although recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the BSSC-W is not validated.9 The four items in the questionnaire ascertain personal information regarding an individual’s overall sexual function satisfaction, the problem causing dysfunction, how bothersome the symptoms are, and whether the patient is interested in discussing it with her provider.12

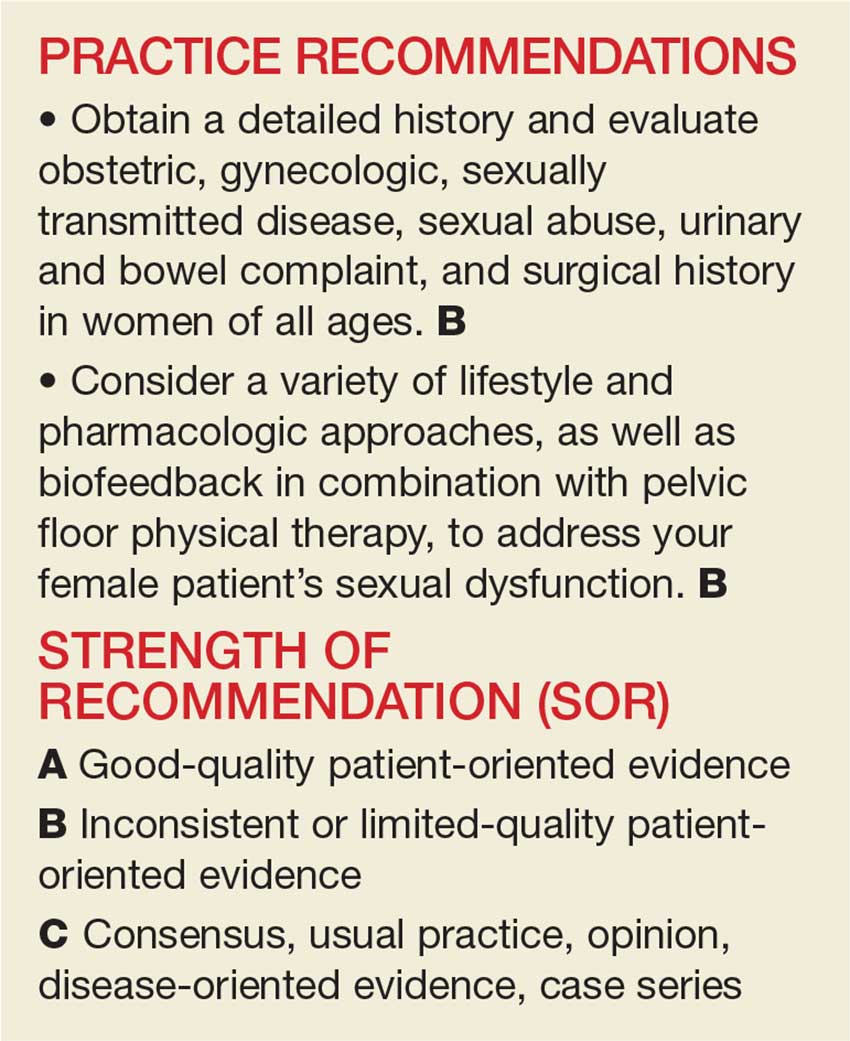

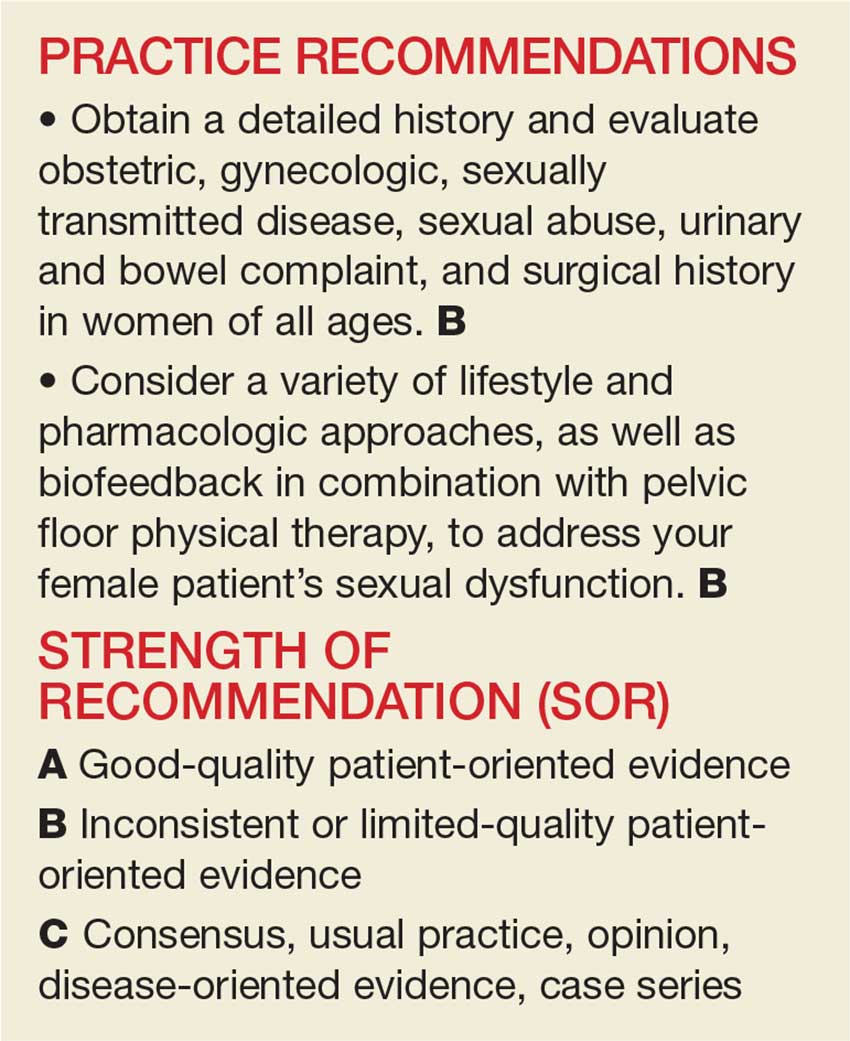

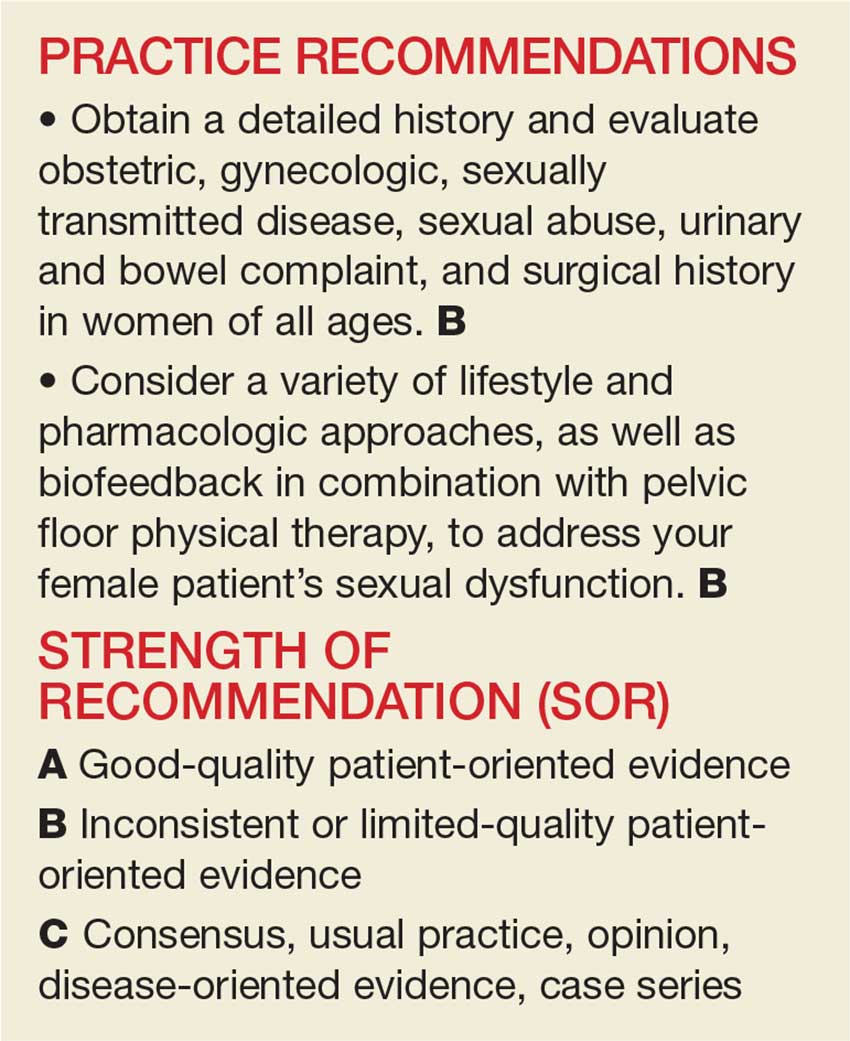

It’s important to obtain a detailed obstetric and gynecologic history that includes any sexually transmitted diseases, sexual abuse, urinary and bowel complaints, or surgeries. In addition, you’ll want to differentiate between various types of dysfunctions. A thorough physical examination, including an external and internal pelvic exam, can help to rule out other causes of sexual dysfunction.

Continue to: General exam: What to look for

General exam: What to look for

The external pelvic examination begins with visual inspection of the vulva, labia majora, and labia minora. Often, this is best accomplished gently with a gloved hand and a cotton swab. This inspection may reveal changes in pubic hair distribution, vulvar skin disorders, lesions, masses, cracks, or fissures. Inspection may also reveal redness and pain typical of vestibulitis, a flattening and pallor of the labia that suggests estrogen deficiency, or pelvic organ prolapse.

The internal pelvic examination begins with a manual evaluation of the muscles of the pelvic floor, uterus, bladder, urethra, anus, and adnexa. Make careful note of any unusual tenderness or pelvic masses. Pelvic floor muscles (PFMs) should voluntarily contract and relax and are not normally tender to palpation. Pelvic organ prolapse and/or hypermobility of the bladder may indicate a weakening of the endopelvic fascia and may cause sexual pain. The size and flexion of the uterus, tenderness in the vaginal fornix possibly indicating endometriosis, and adnexal fullness and/or masses should be identified and evaluated.

Neurologic exam of the pelvis will involve evaluation of sensory and motor function of both lower extremities and include a screening lumbosacral neurologic examination. Lumbosacral examination includes assessment of PFM strength, anal sphincter resting tone, voluntary anal contraction, and perineal sensation. If abnormalities are noted in the screening assessment, a complete comprehensive neurologic examination should be performed.

It’s important to assess pelvic floor muscle strength

Sexual function is associated with normal PFM function.13,14 The PFMs, particularly the pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus, are responsible for involuntary contractions during orgasm.13 Orgasm has been considered a reflex, which is preceded by increased blood flow to the genital organs, tumescence of the vulva and vagina, increased secretions during sexual arousal, and increased tension and contractions of the PFMs.15

Lowenstein et al found that women with strong or moderate PFM contractions scored significantly higher on both orgasm and arousal domains of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), compared with women with weak PFM contractions.16 Orgasm and arousal functions may be associated with PFM strength, with a positive association between pelvic floor strength and sexual activity and function.17,18

The function and dysfunction of the PFMs have been characterized as normal, overactive (high tone), underactive (low tone), and nonfunctioning.

Continue to: Normal PFMs

Normal PFMs are those that can voluntarily and involuntarily contract and relax.19,20

Overactive (high-tone) muscles are those that do not relax and possibly contract during times of relaxation for micturition or defecation. This type of dysfunction can lead to voiding dysfunction, defecatory dysfunction, and dyspareunia.19

Underactive, or low-tone, PFMs cannot contract voluntarily. This can be associated with urinary and anal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

Nonfunctioning muscles are completely inactive.19

How to assess. There are several ways to assess PFM tone and strength.20 The first is intravaginal or intrarectal digital palpation, which can be performed when the patient is in a supine or standing position. This examination evaluates PFM tone, squeeze pressure during contraction, symmetry, and relaxation. However, there is no validated scale to quantify PFM strength. Contractions can be further divided into voluntary and involuntary.19

During the exam, ask the patient to contract as much as she can to evaluate the maximum strength and sustained contraction for endurance. This measurement can be done with digital palpation or with pressure manometry or dynamometry.

Examination can be focused on the levator ani, piriformis, and internal obturator muscles bilaterally and rated by the patient’s reactions. Pelvic muscle tenderness, which can be highly prevalent in women with chronic pelvic pain, is associated with higher degrees of dyspareunia.21 Digital evaluation of the pelvic floor musculature varies in scale, number of fingers used, and parameters evaluated.

Lukban et al have described a 0 to 4 numbered scale that evaluates tenderness in the pelvic floor.22 The scale denotes “1” as comfortable pressure associated with the exam, “2” as uncomfortable pressure associated with the exam, “3” as moderate pain associated with the exam that intensifies with contraction, and “4” indicating severe pain with the exam and inability to perform the contraction maneuver due to pain.

Continue to: EFFECTIVE TREATMENT INCLUDES MULTIPLE OPTIONS

EFFECTIVE TREATMENT INCLUDES MULTIPLE OPTIONS

Lifestyle modifications can help

Lifestyle changes may help improve sexual function. These modifications include physical activity, healthy diet, nutrition counseling, and adequate sleep.23,24

Identifying medical conditions such as depression and anxiety will help delineate differential diagnoses of sexual dysfunction. Cardiovascular diseases may contribute to arousal disorder as a result of atherosclerosis of the vessels supplying the vagina and clitoris. Neurologic diseases such as multiple sclerosis and diabetes can affect sexual dysfunction by impairing arousal and orgasm.

Identification of concurrent comorbidities and implementation of lifestyle changes will help improve overall health and may improve sexual function.25

In addition, Herati et al found food sensitivities to grapefruit juice, spicy foods, alcohol, and caffeine were more prevalent in patients with interstitial cystitis and chronic pelvic pain.26 Avoiding irritants such as soap and other detergents in the perineal region may help decrease dysfunction.27 Finally, foods high in oxalate and other acidic items may cause bladder pain and worsening symptoms of vulvodynia.28

Topical therapies worth considering

Lubricants and moisturizers may help women with dyspareunia or symptoms of vaginal atrophy. For instance

Zestra, which contains a patented blend of botanical oils and extracts and is applied to the vulva prior to sexual activity, has been proven more effective than placebo for improving desire and arousal.29

Neogyn, a nonhormonal cream containing cutaneous lysate, has been shown to improve vulvar pain in women with vulvodynia. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized crossover trial followed 30 patients for three months and found a significant reduction in pain during sexual activity and a significant reduction in erythema.30

Alprostadil, a prostaglandin E1 analogue that increases genital vasodilation when applied topically, is currently undergoing investigational trials.31,32

Patients can also choose from many OTC lubricants that contain water-based, oil-based, or silicone-based ingredients.

Continue to: Don't overlook physical therapy

Don’t overlook physical therapy

Manual therapies, including the transvaginal technique, are used for FSD that results from a variety of causes, including high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. The transvaginal technique can identify myofascial pain; treatment involves internal release of the PFMs and external trigger-point identification and alleviation.

One pilot study examined use of transvaginal Thiele massage twice a week for five weeks in 21 symptomatic women with interstitial cystitis and high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. The researchers found it decreased hypertonicity of the pelvic floor and generated statistically significant improvement in the Symptom and Problem Indexes of the O’Leary-Sant Questionnaire, Likert Visual Analogue Scales for urgency and pain, and the Physical and Mental Component Summary from the SF-12 Quality-of-Life Scale.33 Transvaginal physical therapy is also an effective treatment for myofascial pelvic pain.34

Biofeedback, which can be used in combination with pelvic floor physical therapy, teaches the patient to control the PFMs by visualizing the activity to achieve conscious control over contraction of the pelvic floor and ceasing the cycle of spasm.35 Ger et al investigated patients with levator spasm and found biofeedback decreased pain; relief was rated as good or excellent at 15-month follow-up in six of 14 patients (43%).36

Home devices such as Eros Therapy, an FDA-approved, nonpharmacologic battery-operated device, provide vacuum suction to the clitoris with vibratory sensation. Eros Therapy has been shown to increase blood flow to the clitoris, vagina, and pelvic floor and increase sensation, orgasm, lubrication, and satisfaction.37

Vaginal dilators allow increasing lengths and girths designed to treat vaginal and pelvic floor pain.38 In our practice, we encourage pelvic muscle strengthening tools in the form of Kegel trainers and other insertion devices that may improve PFM coordination and strength.

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy has its place

Pharmacotherapy has its place

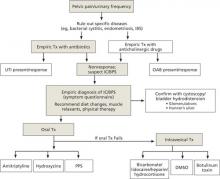

The treatment of FSD may require a multimodal systematic approach targeting genitopelvic pain. But before the best options can be found, it is important to first establish the cause of the pain. Several drug formulations have been effectively used, including hormonal and nonhormonal options.

Conjugated estrogens are FDA approved for the treatment of dyspareunia, which can contribute to decreased desire. Systemic estrogen in oral form, transdermal preparations, and topical formulations may increase sexual desire and arousal and decrease dyspareunia.39 Even synthetic steroid compounds such as tibolone may improve sexual function, although it is not FDA approved for that purpose.40

Ospemifene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator that acts as an estrogen agonist in select tissues, including vaginal epithelium. It is FDA approved for dyspareunia in postmenopausal women.41,42 A daily dose of 60 mg is effective and safe, with minimal adverse effects.42 Studies suggest that testosterone, although not FDA approved in the United States for this purpose, improves sexual desire, pleasure, orgasm, and arousal satisfaction.39 The hormone has not gained FDA approval because of concerns about long-term safety and efficacy.42

Nonhormonal drugs including flibanserin, a well-tolerated serotonin receptor 1A agonist, 2A antagonist shown to improve sexual desire, increase the number of satisfying sexual events and reduce distress associated with low sexual desire when compared with placebo.43 The FDA has approved flibanserin as the first treatment targeted for women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). It can, however, cause severe hypotension and syncope, is not well tolerated with alcohol, and is contraindicated in patients who take strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as fluconazole, verapamil, and erythromycin, or who have liver impairment.

Bupropion, a mild dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and acetylcholine receptor antagonist, has been shown to improve desire in women with and without depression. Although it is FDA approved for major depressive disorder, it is not approved for female sexual dysfunction and is still under investigation.

Tricyclic antidepressants, such as nortriptyline and amitriptyline, may be effective in treating neuropathic pain. Starting doses of both amitriptyline and nortriptyline are 10 mg/d and can be increased to a maximum of 100 mg/d.44 Tricyclic antidepressants are still under investigation for the treatment of FSD.

Muscle relaxants in oral and topical compounded form are used to treat increased pelvic floor tension and spasticity. Cyclobenzaprine and tizanidine are FDA-approved muscle relaxants indicated for muscle spasticity.

Cyclobenzaprine, at a starting dose of 10 mg, can be taken up to three times a day for pelvic floor tension. Tizanidine is a centrally active alpha 2 agonist that’s superior to placebo in treating high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.44

Other medications include benzodiazepines, such as oral clonazepam and intravaginal diazepam, although they are not FDA approved for high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. Rogalski et al evaluated data for 26 patients who received vaginal diazepam for bladder pain, sexual pain, and levator hypertonus.45 They found subjective and sexual pain improvement assessed on FSFI and the visual analog pain scale. PFM tone significantly improved during resting, squeezing, and relaxation phases. Multimodal therapy can be used for muscle spasticity and high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.

Continue to: Trigger point and Botox injections

Trigger point and Botox injections

Although drug therapy has its place in the management of sexual dysfunction, other modalities that involve trigger-point injections or botulinum toxin injections to the PFMs may prove helpful for patients with high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.

A prospective study investigated the role of trigger-point injections in 18 women with levator ani muscle spasm using a mixture of 0.25% bupivacaine in 10 mL, 2% lidocaine in 10 mL, and 40 mg of triamcinolone in 1 mL combined and used for injection of 5 mL per trigger point.46 Three months after injections, 13 of the 18 women showed improvement, resulting in a success rate of 72%. Trigger point injections can be applied externally or transvaginally.

OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) has also been tested for relief of levator ani muscle spasm. Botox is FDA approved for upper and lower limb spasticity but is not approved for pelvic floor spasticity or tension. It may reduce pressure in the PFMs and may be useful in women with high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.47

In a prospective six-month pilot study, 28 patients with pelvic pain for whom conservative treatment did not work received up to 300 U Botox into the pelvic floor.11 The study, which used needle electromyography guidance and a transperineal approach, found that the dyspareunia visual analog scale improved significantly at weeks 12 and 24. Keep in mind, however, that onabotulinumtoxinA should be reserved for patients for whom conventional treatments fail.47,48

Addressing psychologic issues

Sex therapy is a traditional approach that aims to improve individual or couples’ sexual experiences and help reduce anxiety related to sex.42 Cognitive behavioral sex therapy includes traditional sex therapy components but puts greater emphasis on modifying thought patterns that interfere with intimacy and sex.42

Mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral treatments have shown promise for sexual desire problems. It is an ancient eastern practice with Buddhist roots. This therapy is a nonjudgmental, present-moment awareness comprised of self-regulation of attention and accepting orientation to the present.49 Although there is little evidence from prospective studies, it may benefit women with sexual dysfunction after intervention with sex therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy.

CONCLUSION

Female sexual dysfunction is common and affects women of all ages. It can negatively impact a woman’s quality of life and overall well-being. The etiology of FSD is complex, and treatments are based on the causes of the dysfunction. Difficult cases warrant referral to a specialist in sexual health and female pelvic medicine. Future prospective trials, randomized controlled trials, the use of validated questionnaires, and meta-analyses will continue to move us forward as we find better ways to understand, identify, and treat female sexual dysfunction.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed, text revision). Washington, DC; 1994.

2. Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:970-978.

3. Lewis RW, Fugl-Meyer KS, Bosch R, et al. Epidemiology/risk factors of sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2004;1:35-39.

4. Laumann E, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537-544.

5. Office of the Surgeon General. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behavior. Rockville, MD; 2001.

6. Pauls RN, Kleeman SD, Segal JL, et al. Practice patterns of physician members of the American Urogynecologic Society regarding female sexual dysfunction: results of a national survey. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:460-467.

7. American Psychiatric Association. Sexual dysfunction. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed). Washington, DC; 2013.

8. Steege JF, Zolnoun DA. Evaluation and treatment of dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1124-1136.

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 119: Female sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:996-1007.

10. Clayton AH, Hamilton DV. Female sexual dysfunction. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40:267-284.

11. Morrissey D, El-Khawand D, Ginzburg N, et al. Botulinum Toxin A injections into pelvic floor muscles under electromyographic guidance for women with refractory high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction: a 6-month prospective pilot study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21:277-282.

12. Hatzichristou D, Rosen RC, Derogatis LR, et al. Recommendations for the clinical evaluation of men and women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 pt 2):337-348.

13. Kegel A. Sexual functions of the pubococcygeus muscle. West J Surg Obstet Gynecol. 1952;60:521-524.

14. Shafik A. The role of the levator ani muscle in evacuation, sexual performance and pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J. 2000;11:361-376.

15. Kinsey A, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE, et al. Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1998.

16. Lowenstein L, Gruenwald I, Gartman I, et al. Can stronger pelvic muscle floor improve sexual function? Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:553-556.

17. Kanter G, Rogers RG, Pauls RN, et al. A strong pelvic floor is associated with higher rates of sexual activity in women with pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:991-996.

18. Wehbe SA, Kellogg-Spadt S, Whitmore K. Urogenital complaints and female sexual dysfunction. Part 2. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2304-2317.

19. Messelink B, Benson T, Berghmans B, et al. Standardization of terminology of pelvic floor muscle function and dysfunction: report from the Pelvic Floor Clinical Assessment Group of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:374-380.

20. Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:4-20.

21. Montenegro ML, Mateus-Vasconcelos EC, Rosa e Silva JC, et al. Importance of pelvic muscle tenderness evaluation in women with chronic pelvic pain. Pain Med. 2010;11:224-228.

22. Lukban JC, Whitmore KE. Pelvic floor muscle re-education treatment of the overactive bladder and painful bladder syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:273-285.

23. Kalmbach DA, Arnedt JT, Pillai V, et al. The impact of sleep on female sexual response and behavior: a pilot study. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1221-1232.

24. Aversa A, Bruzziches R, Francomano D, et al. Weight loss by multidisciplinary intervention improves endothelial and sexual function in obese fertile women. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1024-1033.

25. Pauls RN, Kleeman SD, Karram MM. Female sexual dysfunction: principles of diagnosis and therapy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:196-205.

26. Herati AS, Shorter B, Tai J, et al. Differences in food sensitivities between female interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS) and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) patients. J Urol. 2009;181(4)(suppl):22.

27. Farrell J, Cacchioni T. The medicalization of women’s sexual pain. J Sex Res. 2012;49:328-336.

28. De Andres J, Sanchis-Lopez NM, Asensio-Samper JM, et al. Vulvodynia—an evidence-based literature review and proposed treatment algorithm. Pain Pract. 2016;16:204-236.

29. Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Women’s use and perceptions of commercial lubricants: prevalence and characteristics in a nationally representative sample of American adults. J Sex Med. 2014;11:642-652.

30. Donders GG, Bellen G. Cream with cutaneous fibroblast lysate for the treatment of provoked vestibulodynia: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled crossover study. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16:427-436.

31. Belkin ZR, Krapf JM, Goldstein AT. Drugs in early clinical development for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2015;24:159-167.

32. Islam A, Mitchel J, Rosen R, et al. Topical alprostadil in the treatment of female sexual arousal disorder: a pilot study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:531-540.

33. Oyama IA, Rejba A, Lukban JC, et al. Modified Thiele massage as therapeutic intervention for female patients with interstitial cystitis and high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. Urology. 2004;64:862-865.

34. Bedaiwy MA, Patterson B, Mahajan S. Prevalence of myofascial chronic pelvic pain and the effectiveness of pelvic floor physical therapy. J Reprod Med. 2013;58:504-510.

35. Wehbe SA, Fariello JY, Whitmore K. Minimally invasive therapies for chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Curr Urol Rep. 2010;11:276-285.

36. Ger GC, Wexner SD, Jorge JM, et al. Evaluation and treatment of chronic intractable rectal pain—a frustrating endeavor. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:139-145.

37. Billups KL, Berman L, Berman J, et al. A new non-pharmacological vacuum therapy for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:435-441.

38. Miles T, Johnson N. Vaginal dilator therapy for women receiving pelvic radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9:CD007291.

39. Goldstein I. Current management strategies of the postmenopausal patient with sexual health problems. J Sex Med. 2007;4(suppl 3):235-253.

40. Modelska K, Cummings S. Female sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women: systematic review of placebo-controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:286-293.

41. Constantine G, Graham S, Portman DJ, et al. Female sexual function improved with ospemifene in postmenopausal women with vulvar and vaginal atrophy: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Climacteric. 2015;18:226-232.

42. Kingsberg SA, Woodard T. Female sexual dysfunction: focus on low desire. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:477-486.

43. Simon JA, Kingsberg SA, Shumel B, et al. Efficacy and safety of flibanserin in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: results of the SNOWDROP trial. Menopause. 2014;21:633-640.

44. Curtis Nickel J, Baranowski AP, Pontari M, et al. Management of men diagnosed with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome who have failed traditional management. Rev Urol. 2007;9:63-72.

45. Rogalski MJ, Kellogg-Spadt S, Hoffmann AR, et al. Retrospective chart review of vaginal diazepam suppository use in high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:895-899.

46. Langford CF, Udvari Nagy S, Ghoniem GM. Levator ani trigger point injections: an underutilized treatment for chronic pelvic pain. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:59-62.

47. Abbott JA, Jarvis SK, Lyons SD, et al. Botulinum toxin type A for chronic pain and pelvic floor spasm in women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:915-923.

48. Kamanli A, Kaya A, Ardicoglu O, et al. Comparison of lidocaine injection, botulinum toxin injection, and dry needling to trigger points in myofascial pain syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25:604-611.

49. Brotto LA, Erskine Y, Carey M, et al. A brief mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral intervention improves sexual functioning versus wait-list control in women treated for gynecologic cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:320-325.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Causes of pain

- Screening

- Multimodal treatment

Care of women with sexual disorders has made great strides since Masters and Johnson began their study in 1957. In 2000, the Sexual Function Health Council of the American Foundation for Urologic Disease devised the classification system for female sexual dysfunction, which was officially defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR.1 There are now definitions for sexual desire disorders, sexual arousal disorders, orgasmic disorder, and sexual pain disorders.

Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) has complex physiologic and psychologic components that require a detailed screening, history, and physical examination. Our goal in this review is to provide primary care providers with insights and practical advice to help screen, diagnose, and treat FSD, which can have a profound impact on patients’ most intimate relationships.

UNDERSTANDING THE TYPES OF FSD

Most women consider sexual health an important part of their overall health.2 Factors that can disrupt normal sexual function include aging, socioeconomics, and other medical comorbidities. FSD is common in women throughout their lives and refers to various sexual dysfunctions including diminished arousal, problems achieving orgasm, dyspareunia, and low desire. Its prevalence is reported to be as high as 20% to 43%.3,4

The World Health Organization and the US Surgeon General have released statements encouraging health care providers to address sexual health during a patient’s annual visits.5 Unfortunately, despite this call to action, many patients and providers are initially hesitant to discuss these problems.6

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) provides the definition and diagnostic guidelines for the different components of FSD. Its classification of sexual disorders was simplified and published in May 2013.7 There are now only three female dysfunctions (as opposed to five in DSM-IV):

- Female hypoactive desire dysfunction and female arousal dysfunction were merged into a single syndrome labeled female sexual interest/arousal disorder.

- The formerly separate dyspareunia (painful intercourse) and vaginismus are now called genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder.

- Female orgasmic disorder remains as a category and is unchanged.

To qualify as a dysfunction, the problem must be present more than 75% of the time, for more than six months, causing significant distress, and must not be explained by a nonsexual mental disorder, relationship distress, substance abuse, or a medical condition.

Substance- or medication-induced sexual dysfunction falls under “Other Dysfunctions” and is defined as a clinically significant disturbance in sexual function that is predominant in the clinical picture. The criteria for substance- and medication-induced sexual dysfunction are unchanged and include neither the 75% nor the six-month requirement. The diagnosis of sexual dysfunction due to a general medical condition and sexual aversion disorder are absent from the DSM-5.7

Continue to: A common symptom

A common symptom. Female sexual disorders can be caused by several complex physiologic and psychologic factors. A common symptom among many women is dyspareunia. It is seen more often in postmenopausal women, and its prevalence ranges from 8% to 22%.8 Pain on vaginal entry usually indicates vaginal atrophy, vaginal dermatitis, or provoked vestibulodynia. Pain on deep penetration could be caused by endometriosis, interstitial cystitis, or uterine leiomyomas.9

The physical examination will reproduce the pain when the vulva or vagina is touched with a cotton swab or when you insert a finger into the vagina. The differential diagnosis is listed in the Table.9-11

EVALUATING THE PATIENT

Initially, many patients and providers may hesitate to discuss sexual dysfunction, but the annual exam is a good opportunity to broach the topic of sexual health.

Screening and history

Clinicians can screen all patients, regardless of age, with the help of a validated sex questionnaire or during a routine review of systems. There are many validated screening tools available. A simple, integrated screening tool to use is the Brief Sexual Symptom Checklist for Women (BSSC-W), created by the International Consultation on Sexual Medicine.12 Although recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the BSSC-W is not validated.9 The four items in the questionnaire ascertain personal information regarding an individual’s overall sexual function satisfaction, the problem causing dysfunction, how bothersome the symptoms are, and whether the patient is interested in discussing it with her provider.12

It’s important to obtain a detailed obstetric and gynecologic history that includes any sexually transmitted diseases, sexual abuse, urinary and bowel complaints, or surgeries. In addition, you’ll want to differentiate between various types of dysfunctions. A thorough physical examination, including an external and internal pelvic exam, can help to rule out other causes of sexual dysfunction.

Continue to: General exam: What to look for

General exam: What to look for

The external pelvic examination begins with visual inspection of the vulva, labia majora, and labia minora. Often, this is best accomplished gently with a gloved hand and a cotton swab. This inspection may reveal changes in pubic hair distribution, vulvar skin disorders, lesions, masses, cracks, or fissures. Inspection may also reveal redness and pain typical of vestibulitis, a flattening and pallor of the labia that suggests estrogen deficiency, or pelvic organ prolapse.

The internal pelvic examination begins with a manual evaluation of the muscles of the pelvic floor, uterus, bladder, urethra, anus, and adnexa. Make careful note of any unusual tenderness or pelvic masses. Pelvic floor muscles (PFMs) should voluntarily contract and relax and are not normally tender to palpation. Pelvic organ prolapse and/or hypermobility of the bladder may indicate a weakening of the endopelvic fascia and may cause sexual pain. The size and flexion of the uterus, tenderness in the vaginal fornix possibly indicating endometriosis, and adnexal fullness and/or masses should be identified and evaluated.

Neurologic exam of the pelvis will involve evaluation of sensory and motor function of both lower extremities and include a screening lumbosacral neurologic examination. Lumbosacral examination includes assessment of PFM strength, anal sphincter resting tone, voluntary anal contraction, and perineal sensation. If abnormalities are noted in the screening assessment, a complete comprehensive neurologic examination should be performed.

It’s important to assess pelvic floor muscle strength

Sexual function is associated with normal PFM function.13,14 The PFMs, particularly the pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus, are responsible for involuntary contractions during orgasm.13 Orgasm has been considered a reflex, which is preceded by increased blood flow to the genital organs, tumescence of the vulva and vagina, increased secretions during sexual arousal, and increased tension and contractions of the PFMs.15

Lowenstein et al found that women with strong or moderate PFM contractions scored significantly higher on both orgasm and arousal domains of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), compared with women with weak PFM contractions.16 Orgasm and arousal functions may be associated with PFM strength, with a positive association between pelvic floor strength and sexual activity and function.17,18

The function and dysfunction of the PFMs have been characterized as normal, overactive (high tone), underactive (low tone), and nonfunctioning.

Continue to: Normal PFMs

Normal PFMs are those that can voluntarily and involuntarily contract and relax.19,20

Overactive (high-tone) muscles are those that do not relax and possibly contract during times of relaxation for micturition or defecation. This type of dysfunction can lead to voiding dysfunction, defecatory dysfunction, and dyspareunia.19

Underactive, or low-tone, PFMs cannot contract voluntarily. This can be associated with urinary and anal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

Nonfunctioning muscles are completely inactive.19

How to assess. There are several ways to assess PFM tone and strength.20 The first is intravaginal or intrarectal digital palpation, which can be performed when the patient is in a supine or standing position. This examination evaluates PFM tone, squeeze pressure during contraction, symmetry, and relaxation. However, there is no validated scale to quantify PFM strength. Contractions can be further divided into voluntary and involuntary.19

During the exam, ask the patient to contract as much as she can to evaluate the maximum strength and sustained contraction for endurance. This measurement can be done with digital palpation or with pressure manometry or dynamometry.

Examination can be focused on the levator ani, piriformis, and internal obturator muscles bilaterally and rated by the patient’s reactions. Pelvic muscle tenderness, which can be highly prevalent in women with chronic pelvic pain, is associated with higher degrees of dyspareunia.21 Digital evaluation of the pelvic floor musculature varies in scale, number of fingers used, and parameters evaluated.

Lukban et al have described a 0 to 4 numbered scale that evaluates tenderness in the pelvic floor.22 The scale denotes “1” as comfortable pressure associated with the exam, “2” as uncomfortable pressure associated with the exam, “3” as moderate pain associated with the exam that intensifies with contraction, and “4” indicating severe pain with the exam and inability to perform the contraction maneuver due to pain.

Continue to: EFFECTIVE TREATMENT INCLUDES MULTIPLE OPTIONS

EFFECTIVE TREATMENT INCLUDES MULTIPLE OPTIONS

Lifestyle modifications can help

Lifestyle changes may help improve sexual function. These modifications include physical activity, healthy diet, nutrition counseling, and adequate sleep.23,24

Identifying medical conditions such as depression and anxiety will help delineate differential diagnoses of sexual dysfunction. Cardiovascular diseases may contribute to arousal disorder as a result of atherosclerosis of the vessels supplying the vagina and clitoris. Neurologic diseases such as multiple sclerosis and diabetes can affect sexual dysfunction by impairing arousal and orgasm.

Identification of concurrent comorbidities and implementation of lifestyle changes will help improve overall health and may improve sexual function.25

In addition, Herati et al found food sensitivities to grapefruit juice, spicy foods, alcohol, and caffeine were more prevalent in patients with interstitial cystitis and chronic pelvic pain.26 Avoiding irritants such as soap and other detergents in the perineal region may help decrease dysfunction.27 Finally, foods high in oxalate and other acidic items may cause bladder pain and worsening symptoms of vulvodynia.28

Topical therapies worth considering

Lubricants and moisturizers may help women with dyspareunia or symptoms of vaginal atrophy. For instance

Zestra, which contains a patented blend of botanical oils and extracts and is applied to the vulva prior to sexual activity, has been proven more effective than placebo for improving desire and arousal.29

Neogyn, a nonhormonal cream containing cutaneous lysate, has been shown to improve vulvar pain in women with vulvodynia. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized crossover trial followed 30 patients for three months and found a significant reduction in pain during sexual activity and a significant reduction in erythema.30

Alprostadil, a prostaglandin E1 analogue that increases genital vasodilation when applied topically, is currently undergoing investigational trials.31,32

Patients can also choose from many OTC lubricants that contain water-based, oil-based, or silicone-based ingredients.

Continue to: Don't overlook physical therapy

Don’t overlook physical therapy

Manual therapies, including the transvaginal technique, are used for FSD that results from a variety of causes, including high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. The transvaginal technique can identify myofascial pain; treatment involves internal release of the PFMs and external trigger-point identification and alleviation.

One pilot study examined use of transvaginal Thiele massage twice a week for five weeks in 21 symptomatic women with interstitial cystitis and high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. The researchers found it decreased hypertonicity of the pelvic floor and generated statistically significant improvement in the Symptom and Problem Indexes of the O’Leary-Sant Questionnaire, Likert Visual Analogue Scales for urgency and pain, and the Physical and Mental Component Summary from the SF-12 Quality-of-Life Scale.33 Transvaginal physical therapy is also an effective treatment for myofascial pelvic pain.34

Biofeedback, which can be used in combination with pelvic floor physical therapy, teaches the patient to control the PFMs by visualizing the activity to achieve conscious control over contraction of the pelvic floor and ceasing the cycle of spasm.35 Ger et al investigated patients with levator spasm and found biofeedback decreased pain; relief was rated as good or excellent at 15-month follow-up in six of 14 patients (43%).36

Home devices such as Eros Therapy, an FDA-approved, nonpharmacologic battery-operated device, provide vacuum suction to the clitoris with vibratory sensation. Eros Therapy has been shown to increase blood flow to the clitoris, vagina, and pelvic floor and increase sensation, orgasm, lubrication, and satisfaction.37

Vaginal dilators allow increasing lengths and girths designed to treat vaginal and pelvic floor pain.38 In our practice, we encourage pelvic muscle strengthening tools in the form of Kegel trainers and other insertion devices that may improve PFM coordination and strength.

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy has its place

Pharmacotherapy has its place

The treatment of FSD may require a multimodal systematic approach targeting genitopelvic pain. But before the best options can be found, it is important to first establish the cause of the pain. Several drug formulations have been effectively used, including hormonal and nonhormonal options.

Conjugated estrogens are FDA approved for the treatment of dyspareunia, which can contribute to decreased desire. Systemic estrogen in oral form, transdermal preparations, and topical formulations may increase sexual desire and arousal and decrease dyspareunia.39 Even synthetic steroid compounds such as tibolone may improve sexual function, although it is not FDA approved for that purpose.40

Ospemifene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator that acts as an estrogen agonist in select tissues, including vaginal epithelium. It is FDA approved for dyspareunia in postmenopausal women.41,42 A daily dose of 60 mg is effective and safe, with minimal adverse effects.42 Studies suggest that testosterone, although not FDA approved in the United States for this purpose, improves sexual desire, pleasure, orgasm, and arousal satisfaction.39 The hormone has not gained FDA approval because of concerns about long-term safety and efficacy.42

Nonhormonal drugs including flibanserin, a well-tolerated serotonin receptor 1A agonist, 2A antagonist shown to improve sexual desire, increase the number of satisfying sexual events and reduce distress associated with low sexual desire when compared with placebo.43 The FDA has approved flibanserin as the first treatment targeted for women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). It can, however, cause severe hypotension and syncope, is not well tolerated with alcohol, and is contraindicated in patients who take strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as fluconazole, verapamil, and erythromycin, or who have liver impairment.

Bupropion, a mild dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and acetylcholine receptor antagonist, has been shown to improve desire in women with and without depression. Although it is FDA approved for major depressive disorder, it is not approved for female sexual dysfunction and is still under investigation.

Tricyclic antidepressants, such as nortriptyline and amitriptyline, may be effective in treating neuropathic pain. Starting doses of both amitriptyline and nortriptyline are 10 mg/d and can be increased to a maximum of 100 mg/d.44 Tricyclic antidepressants are still under investigation for the treatment of FSD.

Muscle relaxants in oral and topical compounded form are used to treat increased pelvic floor tension and spasticity. Cyclobenzaprine and tizanidine are FDA-approved muscle relaxants indicated for muscle spasticity.

Cyclobenzaprine, at a starting dose of 10 mg, can be taken up to three times a day for pelvic floor tension. Tizanidine is a centrally active alpha 2 agonist that’s superior to placebo in treating high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.44

Other medications include benzodiazepines, such as oral clonazepam and intravaginal diazepam, although they are not FDA approved for high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. Rogalski et al evaluated data for 26 patients who received vaginal diazepam for bladder pain, sexual pain, and levator hypertonus.45 They found subjective and sexual pain improvement assessed on FSFI and the visual analog pain scale. PFM tone significantly improved during resting, squeezing, and relaxation phases. Multimodal therapy can be used for muscle spasticity and high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.

Continue to: Trigger point and Botox injections

Trigger point and Botox injections

Although drug therapy has its place in the management of sexual dysfunction, other modalities that involve trigger-point injections or botulinum toxin injections to the PFMs may prove helpful for patients with high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.

A prospective study investigated the role of trigger-point injections in 18 women with levator ani muscle spasm using a mixture of 0.25% bupivacaine in 10 mL, 2% lidocaine in 10 mL, and 40 mg of triamcinolone in 1 mL combined and used for injection of 5 mL per trigger point.46 Three months after injections, 13 of the 18 women showed improvement, resulting in a success rate of 72%. Trigger point injections can be applied externally or transvaginally.

OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) has also been tested for relief of levator ani muscle spasm. Botox is FDA approved for upper and lower limb spasticity but is not approved for pelvic floor spasticity or tension. It may reduce pressure in the PFMs and may be useful in women with high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.47

In a prospective six-month pilot study, 28 patients with pelvic pain for whom conservative treatment did not work received up to 300 U Botox into the pelvic floor.11 The study, which used needle electromyography guidance and a transperineal approach, found that the dyspareunia visual analog scale improved significantly at weeks 12 and 24. Keep in mind, however, that onabotulinumtoxinA should be reserved for patients for whom conventional treatments fail.47,48

Addressing psychologic issues

Sex therapy is a traditional approach that aims to improve individual or couples’ sexual experiences and help reduce anxiety related to sex.42 Cognitive behavioral sex therapy includes traditional sex therapy components but puts greater emphasis on modifying thought patterns that interfere with intimacy and sex.42

Mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral treatments have shown promise for sexual desire problems. It is an ancient eastern practice with Buddhist roots. This therapy is a nonjudgmental, present-moment awareness comprised of self-regulation of attention and accepting orientation to the present.49 Although there is little evidence from prospective studies, it may benefit women with sexual dysfunction after intervention with sex therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy.

CONCLUSION

Female sexual dysfunction is common and affects women of all ages. It can negatively impact a woman’s quality of life and overall well-being. The etiology of FSD is complex, and treatments are based on the causes of the dysfunction. Difficult cases warrant referral to a specialist in sexual health and female pelvic medicine. Future prospective trials, randomized controlled trials, the use of validated questionnaires, and meta-analyses will continue to move us forward as we find better ways to understand, identify, and treat female sexual dysfunction.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Causes of pain

- Screening

- Multimodal treatment

Care of women with sexual disorders has made great strides since Masters and Johnson began their study in 1957. In 2000, the Sexual Function Health Council of the American Foundation for Urologic Disease devised the classification system for female sexual dysfunction, which was officially defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR.1 There are now definitions for sexual desire disorders, sexual arousal disorders, orgasmic disorder, and sexual pain disorders.

Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) has complex physiologic and psychologic components that require a detailed screening, history, and physical examination. Our goal in this review is to provide primary care providers with insights and practical advice to help screen, diagnose, and treat FSD, which can have a profound impact on patients’ most intimate relationships.

UNDERSTANDING THE TYPES OF FSD

Most women consider sexual health an important part of their overall health.2 Factors that can disrupt normal sexual function include aging, socioeconomics, and other medical comorbidities. FSD is common in women throughout their lives and refers to various sexual dysfunctions including diminished arousal, problems achieving orgasm, dyspareunia, and low desire. Its prevalence is reported to be as high as 20% to 43%.3,4

The World Health Organization and the US Surgeon General have released statements encouraging health care providers to address sexual health during a patient’s annual visits.5 Unfortunately, despite this call to action, many patients and providers are initially hesitant to discuss these problems.6

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) provides the definition and diagnostic guidelines for the different components of FSD. Its classification of sexual disorders was simplified and published in May 2013.7 There are now only three female dysfunctions (as opposed to five in DSM-IV):

- Female hypoactive desire dysfunction and female arousal dysfunction were merged into a single syndrome labeled female sexual interest/arousal disorder.

- The formerly separate dyspareunia (painful intercourse) and vaginismus are now called genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder.

- Female orgasmic disorder remains as a category and is unchanged.

To qualify as a dysfunction, the problem must be present more than 75% of the time, for more than six months, causing significant distress, and must not be explained by a nonsexual mental disorder, relationship distress, substance abuse, or a medical condition.

Substance- or medication-induced sexual dysfunction falls under “Other Dysfunctions” and is defined as a clinically significant disturbance in sexual function that is predominant in the clinical picture. The criteria for substance- and medication-induced sexual dysfunction are unchanged and include neither the 75% nor the six-month requirement. The diagnosis of sexual dysfunction due to a general medical condition and sexual aversion disorder are absent from the DSM-5.7

Continue to: A common symptom

A common symptom. Female sexual disorders can be caused by several complex physiologic and psychologic factors. A common symptom among many women is dyspareunia. It is seen more often in postmenopausal women, and its prevalence ranges from 8% to 22%.8 Pain on vaginal entry usually indicates vaginal atrophy, vaginal dermatitis, or provoked vestibulodynia. Pain on deep penetration could be caused by endometriosis, interstitial cystitis, or uterine leiomyomas.9

The physical examination will reproduce the pain when the vulva or vagina is touched with a cotton swab or when you insert a finger into the vagina. The differential diagnosis is listed in the Table.9-11

EVALUATING THE PATIENT

Initially, many patients and providers may hesitate to discuss sexual dysfunction, but the annual exam is a good opportunity to broach the topic of sexual health.

Screening and history

Clinicians can screen all patients, regardless of age, with the help of a validated sex questionnaire or during a routine review of systems. There are many validated screening tools available. A simple, integrated screening tool to use is the Brief Sexual Symptom Checklist for Women (BSSC-W), created by the International Consultation on Sexual Medicine.12 Although recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the BSSC-W is not validated.9 The four items in the questionnaire ascertain personal information regarding an individual’s overall sexual function satisfaction, the problem causing dysfunction, how bothersome the symptoms are, and whether the patient is interested in discussing it with her provider.12

It’s important to obtain a detailed obstetric and gynecologic history that includes any sexually transmitted diseases, sexual abuse, urinary and bowel complaints, or surgeries. In addition, you’ll want to differentiate between various types of dysfunctions. A thorough physical examination, including an external and internal pelvic exam, can help to rule out other causes of sexual dysfunction.

Continue to: General exam: What to look for

General exam: What to look for

The external pelvic examination begins with visual inspection of the vulva, labia majora, and labia minora. Often, this is best accomplished gently with a gloved hand and a cotton swab. This inspection may reveal changes in pubic hair distribution, vulvar skin disorders, lesions, masses, cracks, or fissures. Inspection may also reveal redness and pain typical of vestibulitis, a flattening and pallor of the labia that suggests estrogen deficiency, or pelvic organ prolapse.

The internal pelvic examination begins with a manual evaluation of the muscles of the pelvic floor, uterus, bladder, urethra, anus, and adnexa. Make careful note of any unusual tenderness or pelvic masses. Pelvic floor muscles (PFMs) should voluntarily contract and relax and are not normally tender to palpation. Pelvic organ prolapse and/or hypermobility of the bladder may indicate a weakening of the endopelvic fascia and may cause sexual pain. The size and flexion of the uterus, tenderness in the vaginal fornix possibly indicating endometriosis, and adnexal fullness and/or masses should be identified and evaluated.

Neurologic exam of the pelvis will involve evaluation of sensory and motor function of both lower extremities and include a screening lumbosacral neurologic examination. Lumbosacral examination includes assessment of PFM strength, anal sphincter resting tone, voluntary anal contraction, and perineal sensation. If abnormalities are noted in the screening assessment, a complete comprehensive neurologic examination should be performed.

It’s important to assess pelvic floor muscle strength

Sexual function is associated with normal PFM function.13,14 The PFMs, particularly the pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus, are responsible for involuntary contractions during orgasm.13 Orgasm has been considered a reflex, which is preceded by increased blood flow to the genital organs, tumescence of the vulva and vagina, increased secretions during sexual arousal, and increased tension and contractions of the PFMs.15

Lowenstein et al found that women with strong or moderate PFM contractions scored significantly higher on both orgasm and arousal domains of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), compared with women with weak PFM contractions.16 Orgasm and arousal functions may be associated with PFM strength, with a positive association between pelvic floor strength and sexual activity and function.17,18

The function and dysfunction of the PFMs have been characterized as normal, overactive (high tone), underactive (low tone), and nonfunctioning.

Continue to: Normal PFMs

Normal PFMs are those that can voluntarily and involuntarily contract and relax.19,20

Overactive (high-tone) muscles are those that do not relax and possibly contract during times of relaxation for micturition or defecation. This type of dysfunction can lead to voiding dysfunction, defecatory dysfunction, and dyspareunia.19

Underactive, or low-tone, PFMs cannot contract voluntarily. This can be associated with urinary and anal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

Nonfunctioning muscles are completely inactive.19

How to assess. There are several ways to assess PFM tone and strength.20 The first is intravaginal or intrarectal digital palpation, which can be performed when the patient is in a supine or standing position. This examination evaluates PFM tone, squeeze pressure during contraction, symmetry, and relaxation. However, there is no validated scale to quantify PFM strength. Contractions can be further divided into voluntary and involuntary.19

During the exam, ask the patient to contract as much as she can to evaluate the maximum strength and sustained contraction for endurance. This measurement can be done with digital palpation or with pressure manometry or dynamometry.

Examination can be focused on the levator ani, piriformis, and internal obturator muscles bilaterally and rated by the patient’s reactions. Pelvic muscle tenderness, which can be highly prevalent in women with chronic pelvic pain, is associated with higher degrees of dyspareunia.21 Digital evaluation of the pelvic floor musculature varies in scale, number of fingers used, and parameters evaluated.

Lukban et al have described a 0 to 4 numbered scale that evaluates tenderness in the pelvic floor.22 The scale denotes “1” as comfortable pressure associated with the exam, “2” as uncomfortable pressure associated with the exam, “3” as moderate pain associated with the exam that intensifies with contraction, and “4” indicating severe pain with the exam and inability to perform the contraction maneuver due to pain.

Continue to: EFFECTIVE TREATMENT INCLUDES MULTIPLE OPTIONS

EFFECTIVE TREATMENT INCLUDES MULTIPLE OPTIONS

Lifestyle modifications can help

Lifestyle changes may help improve sexual function. These modifications include physical activity, healthy diet, nutrition counseling, and adequate sleep.23,24

Identifying medical conditions such as depression and anxiety will help delineate differential diagnoses of sexual dysfunction. Cardiovascular diseases may contribute to arousal disorder as a result of atherosclerosis of the vessels supplying the vagina and clitoris. Neurologic diseases such as multiple sclerosis and diabetes can affect sexual dysfunction by impairing arousal and orgasm.

Identification of concurrent comorbidities and implementation of lifestyle changes will help improve overall health and may improve sexual function.25

In addition, Herati et al found food sensitivities to grapefruit juice, spicy foods, alcohol, and caffeine were more prevalent in patients with interstitial cystitis and chronic pelvic pain.26 Avoiding irritants such as soap and other detergents in the perineal region may help decrease dysfunction.27 Finally, foods high in oxalate and other acidic items may cause bladder pain and worsening symptoms of vulvodynia.28

Topical therapies worth considering

Lubricants and moisturizers may help women with dyspareunia or symptoms of vaginal atrophy. For instance

Zestra, which contains a patented blend of botanical oils and extracts and is applied to the vulva prior to sexual activity, has been proven more effective than placebo for improving desire and arousal.29

Neogyn, a nonhormonal cream containing cutaneous lysate, has been shown to improve vulvar pain in women with vulvodynia. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized crossover trial followed 30 patients for three months and found a significant reduction in pain during sexual activity and a significant reduction in erythema.30

Alprostadil, a prostaglandin E1 analogue that increases genital vasodilation when applied topically, is currently undergoing investigational trials.31,32

Patients can also choose from many OTC lubricants that contain water-based, oil-based, or silicone-based ingredients.

Continue to: Don't overlook physical therapy

Don’t overlook physical therapy

Manual therapies, including the transvaginal technique, are used for FSD that results from a variety of causes, including high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. The transvaginal technique can identify myofascial pain; treatment involves internal release of the PFMs and external trigger-point identification and alleviation.

One pilot study examined use of transvaginal Thiele massage twice a week for five weeks in 21 symptomatic women with interstitial cystitis and high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. The researchers found it decreased hypertonicity of the pelvic floor and generated statistically significant improvement in the Symptom and Problem Indexes of the O’Leary-Sant Questionnaire, Likert Visual Analogue Scales for urgency and pain, and the Physical and Mental Component Summary from the SF-12 Quality-of-Life Scale.33 Transvaginal physical therapy is also an effective treatment for myofascial pelvic pain.34

Biofeedback, which can be used in combination with pelvic floor physical therapy, teaches the patient to control the PFMs by visualizing the activity to achieve conscious control over contraction of the pelvic floor and ceasing the cycle of spasm.35 Ger et al investigated patients with levator spasm and found biofeedback decreased pain; relief was rated as good or excellent at 15-month follow-up in six of 14 patients (43%).36

Home devices such as Eros Therapy, an FDA-approved, nonpharmacologic battery-operated device, provide vacuum suction to the clitoris with vibratory sensation. Eros Therapy has been shown to increase blood flow to the clitoris, vagina, and pelvic floor and increase sensation, orgasm, lubrication, and satisfaction.37

Vaginal dilators allow increasing lengths and girths designed to treat vaginal and pelvic floor pain.38 In our practice, we encourage pelvic muscle strengthening tools in the form of Kegel trainers and other insertion devices that may improve PFM coordination and strength.

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy has its place

Pharmacotherapy has its place

The treatment of FSD may require a multimodal systematic approach targeting genitopelvic pain. But before the best options can be found, it is important to first establish the cause of the pain. Several drug formulations have been effectively used, including hormonal and nonhormonal options.

Conjugated estrogens are FDA approved for the treatment of dyspareunia, which can contribute to decreased desire. Systemic estrogen in oral form, transdermal preparations, and topical formulations may increase sexual desire and arousal and decrease dyspareunia.39 Even synthetic steroid compounds such as tibolone may improve sexual function, although it is not FDA approved for that purpose.40

Ospemifene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator that acts as an estrogen agonist in select tissues, including vaginal epithelium. It is FDA approved for dyspareunia in postmenopausal women.41,42 A daily dose of 60 mg is effective and safe, with minimal adverse effects.42 Studies suggest that testosterone, although not FDA approved in the United States for this purpose, improves sexual desire, pleasure, orgasm, and arousal satisfaction.39 The hormone has not gained FDA approval because of concerns about long-term safety and efficacy.42

Nonhormonal drugs including flibanserin, a well-tolerated serotonin receptor 1A agonist, 2A antagonist shown to improve sexual desire, increase the number of satisfying sexual events and reduce distress associated with low sexual desire when compared with placebo.43 The FDA has approved flibanserin as the first treatment targeted for women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). It can, however, cause severe hypotension and syncope, is not well tolerated with alcohol, and is contraindicated in patients who take strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as fluconazole, verapamil, and erythromycin, or who have liver impairment.

Bupropion, a mild dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and acetylcholine receptor antagonist, has been shown to improve desire in women with and without depression. Although it is FDA approved for major depressive disorder, it is not approved for female sexual dysfunction and is still under investigation.

Tricyclic antidepressants, such as nortriptyline and amitriptyline, may be effective in treating neuropathic pain. Starting doses of both amitriptyline and nortriptyline are 10 mg/d and can be increased to a maximum of 100 mg/d.44 Tricyclic antidepressants are still under investigation for the treatment of FSD.

Muscle relaxants in oral and topical compounded form are used to treat increased pelvic floor tension and spasticity. Cyclobenzaprine and tizanidine are FDA-approved muscle relaxants indicated for muscle spasticity.

Cyclobenzaprine, at a starting dose of 10 mg, can be taken up to three times a day for pelvic floor tension. Tizanidine is a centrally active alpha 2 agonist that’s superior to placebo in treating high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.44

Other medications include benzodiazepines, such as oral clonazepam and intravaginal diazepam, although they are not FDA approved for high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. Rogalski et al evaluated data for 26 patients who received vaginal diazepam for bladder pain, sexual pain, and levator hypertonus.45 They found subjective and sexual pain improvement assessed on FSFI and the visual analog pain scale. PFM tone significantly improved during resting, squeezing, and relaxation phases. Multimodal therapy can be used for muscle spasticity and high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.

Continue to: Trigger point and Botox injections

Trigger point and Botox injections

Although drug therapy has its place in the management of sexual dysfunction, other modalities that involve trigger-point injections or botulinum toxin injections to the PFMs may prove helpful for patients with high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.

A prospective study investigated the role of trigger-point injections in 18 women with levator ani muscle spasm using a mixture of 0.25% bupivacaine in 10 mL, 2% lidocaine in 10 mL, and 40 mg of triamcinolone in 1 mL combined and used for injection of 5 mL per trigger point.46 Three months after injections, 13 of the 18 women showed improvement, resulting in a success rate of 72%. Trigger point injections can be applied externally or transvaginally.

OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) has also been tested for relief of levator ani muscle spasm. Botox is FDA approved for upper and lower limb spasticity but is not approved for pelvic floor spasticity or tension. It may reduce pressure in the PFMs and may be useful in women with high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction.47

In a prospective six-month pilot study, 28 patients with pelvic pain for whom conservative treatment did not work received up to 300 U Botox into the pelvic floor.11 The study, which used needle electromyography guidance and a transperineal approach, found that the dyspareunia visual analog scale improved significantly at weeks 12 and 24. Keep in mind, however, that onabotulinumtoxinA should be reserved for patients for whom conventional treatments fail.47,48

Addressing psychologic issues

Sex therapy is a traditional approach that aims to improve individual or couples’ sexual experiences and help reduce anxiety related to sex.42 Cognitive behavioral sex therapy includes traditional sex therapy components but puts greater emphasis on modifying thought patterns that interfere with intimacy and sex.42

Mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral treatments have shown promise for sexual desire problems. It is an ancient eastern practice with Buddhist roots. This therapy is a nonjudgmental, present-moment awareness comprised of self-regulation of attention and accepting orientation to the present.49 Although there is little evidence from prospective studies, it may benefit women with sexual dysfunction after intervention with sex therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy.

CONCLUSION

Female sexual dysfunction is common and affects women of all ages. It can negatively impact a woman’s quality of life and overall well-being. The etiology of FSD is complex, and treatments are based on the causes of the dysfunction. Difficult cases warrant referral to a specialist in sexual health and female pelvic medicine. Future prospective trials, randomized controlled trials, the use of validated questionnaires, and meta-analyses will continue to move us forward as we find better ways to understand, identify, and treat female sexual dysfunction.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed, text revision). Washington, DC; 1994.

2. Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:970-978.

3. Lewis RW, Fugl-Meyer KS, Bosch R, et al. Epidemiology/risk factors of sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2004;1:35-39.

4. Laumann E, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537-544.

5. Office of the Surgeon General. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behavior. Rockville, MD; 2001.

6. Pauls RN, Kleeman SD, Segal JL, et al. Practice patterns of physician members of the American Urogynecologic Society regarding female sexual dysfunction: results of a national survey. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:460-467.

7. American Psychiatric Association. Sexual dysfunction. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed). Washington, DC; 2013.

8. Steege JF, Zolnoun DA. Evaluation and treatment of dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1124-1136.

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 119: Female sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:996-1007.

10. Clayton AH, Hamilton DV. Female sexual dysfunction. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40:267-284.

11. Morrissey D, El-Khawand D, Ginzburg N, et al. Botulinum Toxin A injections into pelvic floor muscles under electromyographic guidance for women with refractory high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction: a 6-month prospective pilot study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21:277-282.

12. Hatzichristou D, Rosen RC, Derogatis LR, et al. Recommendations for the clinical evaluation of men and women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 pt 2):337-348.

13. Kegel A. Sexual functions of the pubococcygeus muscle. West J Surg Obstet Gynecol. 1952;60:521-524.

14. Shafik A. The role of the levator ani muscle in evacuation, sexual performance and pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J. 2000;11:361-376.

15. Kinsey A, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE, et al. Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1998.

16. Lowenstein L, Gruenwald I, Gartman I, et al. Can stronger pelvic muscle floor improve sexual function? Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:553-556.

17. Kanter G, Rogers RG, Pauls RN, et al. A strong pelvic floor is associated with higher rates of sexual activity in women with pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:991-996.

18. Wehbe SA, Kellogg-Spadt S, Whitmore K. Urogenital complaints and female sexual dysfunction. Part 2. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2304-2317.

19. Messelink B, Benson T, Berghmans B, et al. Standardization of terminology of pelvic floor muscle function and dysfunction: report from the Pelvic Floor Clinical Assessment Group of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:374-380.

20. Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:4-20.

21. Montenegro ML, Mateus-Vasconcelos EC, Rosa e Silva JC, et al. Importance of pelvic muscle tenderness evaluation in women with chronic pelvic pain. Pain Med. 2010;11:224-228.

22. Lukban JC, Whitmore KE. Pelvic floor muscle re-education treatment of the overactive bladder and painful bladder syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:273-285.

23. Kalmbach DA, Arnedt JT, Pillai V, et al. The impact of sleep on female sexual response and behavior: a pilot study. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1221-1232.

24. Aversa A, Bruzziches R, Francomano D, et al. Weight loss by multidisciplinary intervention improves endothelial and sexual function in obese fertile women. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1024-1033.

25. Pauls RN, Kleeman SD, Karram MM. Female sexual dysfunction: principles of diagnosis and therapy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:196-205.

26. Herati AS, Shorter B, Tai J, et al. Differences in food sensitivities between female interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS) and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) patients. J Urol. 2009;181(4)(suppl):22.

27. Farrell J, Cacchioni T. The medicalization of women’s sexual pain. J Sex Res. 2012;49:328-336.

28. De Andres J, Sanchis-Lopez NM, Asensio-Samper JM, et al. Vulvodynia—an evidence-based literature review and proposed treatment algorithm. Pain Pract. 2016;16:204-236.

29. Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Women’s use and perceptions of commercial lubricants: prevalence and characteristics in a nationally representative sample of American adults. J Sex Med. 2014;11:642-652.

30. Donders GG, Bellen G. Cream with cutaneous fibroblast lysate for the treatment of provoked vestibulodynia: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled crossover study. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16:427-436.

31. Belkin ZR, Krapf JM, Goldstein AT. Drugs in early clinical development for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2015;24:159-167.

32. Islam A, Mitchel J, Rosen R, et al. Topical alprostadil in the treatment of female sexual arousal disorder: a pilot study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:531-540.

33. Oyama IA, Rejba A, Lukban JC, et al. Modified Thiele massage as therapeutic intervention for female patients with interstitial cystitis and high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. Urology. 2004;64:862-865.

34. Bedaiwy MA, Patterson B, Mahajan S. Prevalence of myofascial chronic pelvic pain and the effectiveness of pelvic floor physical therapy. J Reprod Med. 2013;58:504-510.

35. Wehbe SA, Fariello JY, Whitmore K. Minimally invasive therapies for chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Curr Urol Rep. 2010;11:276-285.

36. Ger GC, Wexner SD, Jorge JM, et al. Evaluation and treatment of chronic intractable rectal pain—a frustrating endeavor. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:139-145.

37. Billups KL, Berman L, Berman J, et al. A new non-pharmacological vacuum therapy for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:435-441.

38. Miles T, Johnson N. Vaginal dilator therapy for women receiving pelvic radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9:CD007291.

39. Goldstein I. Current management strategies of the postmenopausal patient with sexual health problems. J Sex Med. 2007;4(suppl 3):235-253.

40. Modelska K, Cummings S. Female sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women: systematic review of placebo-controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:286-293.

41. Constantine G, Graham S, Portman DJ, et al. Female sexual function improved with ospemifene in postmenopausal women with vulvar and vaginal atrophy: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Climacteric. 2015;18:226-232.

42. Kingsberg SA, Woodard T. Female sexual dysfunction: focus on low desire. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:477-486.

43. Simon JA, Kingsberg SA, Shumel B, et al. Efficacy and safety of flibanserin in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: results of the SNOWDROP trial. Menopause. 2014;21:633-640.

44. Curtis Nickel J, Baranowski AP, Pontari M, et al. Management of men diagnosed with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome who have failed traditional management. Rev Urol. 2007;9:63-72.

45. Rogalski MJ, Kellogg-Spadt S, Hoffmann AR, et al. Retrospective chart review of vaginal diazepam suppository use in high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:895-899.

46. Langford CF, Udvari Nagy S, Ghoniem GM. Levator ani trigger point injections: an underutilized treatment for chronic pelvic pain. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:59-62.

47. Abbott JA, Jarvis SK, Lyons SD, et al. Botulinum toxin type A for chronic pain and pelvic floor spasm in women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:915-923.