User login

Judicious antibiotic use key in ambulatory settings

I was recently asked to evaluate a young child with a urinary tract infection caused by an extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Escherichia coli.

I’d just broken the bad news to the mother: There was no oral medication available to treat the baby, so she’d have to stay in the hospital for a full intravenous course.

“Has your child been treated with antibiotics recently?” I asked the mother, wondering how the baby had come to have such a resistant infection.

“She had a couple days of runny nose and a low-grade fever a couple of weeks ago,” she told me. “Her doctor treated her for a sinus infection.”

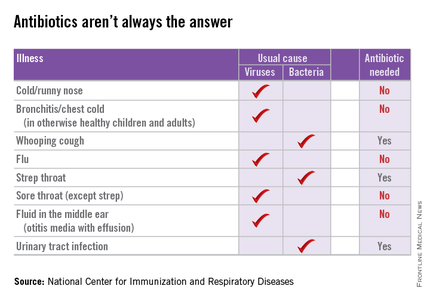

In 2011, doctors in outpatient settings across the United States wrote 262.5 million prescriptions for antibiotics – 73.7 million for children – and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 50% of these were completely unnecessary because they were prescribed for viral respiratory tract infections (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 May 1;60[9]:1308-16).

Prescribing practices varied by region, with the highest rates in the South. Don’t think I’m judging. I live in Kentucky, the state with the highest rate of antibiotic prescribing at 1,281 prescriptions per 1,000 persons. Is it any wonder that we’re seeing kids with very resistant infections?

The CDC estimates that at least two million people in the United States are infected annually with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and at least 23,000 of them die as a result of these infections. It is estimated that prevention strategies that include better antibiotic prescribing could prevent as many as 619,000 infections and 37,000 deaths over 5 years. Fortunately, my little patient recovered fully, but it has made me think about antimicrobial stewardship, especially its role in the outpatient setting.

According the American Academy of Pediatrics, the goal of antimicrobial stewardship is “to optimize antimicrobial use, with the aim of decreasing inappropriate use that leads to unwarranted toxicity and to selection and spread of resistant organisms.”

Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) are increasingly common in inpatient settings and have been shown to reduce antibiotic use. These programs can take many forms. The hospital where I work relies primarily on clinical guidelines emphasizing appropriate empiric therapy for a variety of common conditions. Other hospitals employ prospective audit and feedback, as well as a restricted formulary. Medicare and Medicaid Conditions of Participation will soon require hospitals that receive funds from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have an ASP.

Comparatively little has been published about ASPs in the outpatient setting. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that effective strategies include patient education, provider education, provider audit and feedback, and clinical decision support. We have at least some data that these work, at least in a research setting.

From 2000 to 2003, a controlled, cluster-randomized trial in 16 Massachusetts communities demonstrated that a 3-year, multifaceted, community-level intervention was “modestly successful” in reducing antibiotic use (Pediatrics. 2008 Jan;121[1]:e15-23). As a part of this intervention, parents received education via direct mail and in primary care settings, pharmacies, and child care centers while physicians received small-group education, frequent updates and educational materials, and prescribing feedback. Antibiotic prescribing was measured via health insurance claims data from all children who were 6 years of age or younger and resided in study communities, and were insured by one of four participating health plans. Coincident with the intervention, there was 4.2% decrease in antibiotic prescribing among children aged 24 to <48 months and a 6.7% decrease among those aged 48-72 months. The effect was greatest among Medicaid-insured children.

More recently, 18 primary care practices in Pennsylvania and New Jersey were randomized to an intervention that consisted of a 1-hour, on-site education session followed by 1 year of personalized, quarterly audit and feedback of prescribing for bacterial and viral acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs), or usual practice (JAMA. 2013 Jun 12;309[22]:2345-52). The prescribing practices of 162 clinicians were included in the analysis.

Broad spectrum–antibiotic prescribing decreased in intervention practices, compared with controls (26.8% to 14.3% among intervention practices vs. 28.4% to 22.6% in controls), as did “off-guideline” prescribing for pneumonia and acute sinusitis. Antibiotic prescribing for viral infections was relatively low at baseline and did not change. The authors concluded that “extending antimicrobial stewardship to the ambulatory setting, where such programs have generally not been implemented, may have important health benefits.” Unfortunately, the positive effect in these practices was not sustained after the audit and feedback stopped (JAMA. 2014 Dec 17;312[23]:2569-70).

Not all antimicrobial stewardship interventions need to be time- and resource-intensive. Investigators in California found that providers who publicly pledged to reducing inappropriate antibiotic use for ARTIs by signing and posting a commitment letter in exam rooms actually prescribed fewer inappropriate antibiotic courses for their adult patients (JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Mar;174[3]:425-31).

“When you have a cough, sore throat, or other illness, your doctor will help you select the best possible treatments. If an antibiotic would do more harm than good, your doctor will explain this to you, and may offer other treatments that are better for you,” the letter read in part. There was a 19.7 absolute percentage reduction in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for ARTIs among clinicians randomized to the commitment letter invention relative to controls.

Can antimicrobial strategies work in the “real” world, in a busy pediatrician’s office? According to Dr. Patricia Purcell, a physician with East Louisville Pediatrics in Louisville, Ky., the answer is “yes.”

“We actually start with education in the newborn period,” Dr. Purcell said. “We let parents know that we are not going to call in antibiotics over the phone, and we’re not going to prescribe them for an upper respiratory tract infection.”

Dr. Purcell and her partners have committed to following evidence-based guidelines for antibiotic practices, such as the AAP’s guidelines for otitis media and sinusitis. She also noted that at least one major insurance company is starting to provide the group feedback about their antibiotic-prescribing practices. “They want to make sure we are not prescribing antibiotics for viruses,” she said.

Still, the message that antibiotics are not always the answer can be a bitter pill for some parents to swallow. A pediatrician friend in Alabama notes: “I have these conversations every day, and a lot of parents are mad at me for not prescribing antibiotics for their child’s ‘terrible cold.’” Another friend notes that watchful waiting can be a burden for parents who have high copays or difficulties with transportation.

Still, many parents would welcome a frank discussion about the risks and benefits of antibiotics. After I shared some of the CDC information for parents with a nursing colleague, she told me that her daughter recently had a febrile illness and was diagnosed with otitis media. “I don’t like giving my kids meds they don’t need,” she told me. “However, if the doc says they need antibiotics and they prescribe them, I give them. I never say, ‘Do we really need antibiotics for that?’”

Now she is rethinking that approach. “Was 10 days of amoxicillin necessary for a ‘red’ eardrum?! I’m just a mom. ... I don’t know the answer to that! Was her ear red because she had been crying or because of her fever? Did she get ‘treatment’ she did not need? Did the doctor give me antibiotics without education because she assumed that is why I brought her in?”

This year’s “Get Smart About Antibiotics Week” was Nov. 16-22. This annual 1-week observance is intended to raise awareness of the threat of antibiotic resistance and the importance of appropriate prescribing and use. Kudos if you celebrated this in your office. If you missed it, it’s not too late to check out some of the activities suggested by the CDC, and try one or two in your own practice. Email me with your ideas about stewardship in the outpatient setting, and I’ll try to feature at least some of them in a future column.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. Dr. Bryant disclosed that she has been an investigator for clinical trials funded by Pfizer for the past 2 years. Email her at [email protected].

I was recently asked to evaluate a young child with a urinary tract infection caused by an extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Escherichia coli.

I’d just broken the bad news to the mother: There was no oral medication available to treat the baby, so she’d have to stay in the hospital for a full intravenous course.

“Has your child been treated with antibiotics recently?” I asked the mother, wondering how the baby had come to have such a resistant infection.

“She had a couple days of runny nose and a low-grade fever a couple of weeks ago,” she told me. “Her doctor treated her for a sinus infection.”

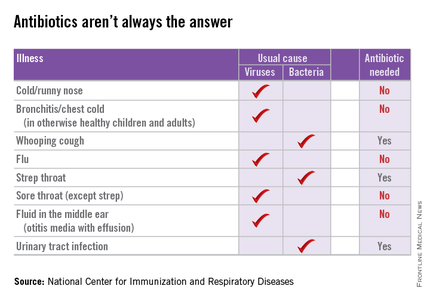

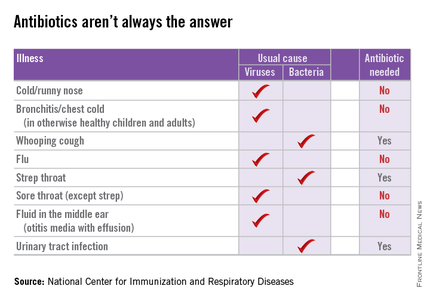

In 2011, doctors in outpatient settings across the United States wrote 262.5 million prescriptions for antibiotics – 73.7 million for children – and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 50% of these were completely unnecessary because they were prescribed for viral respiratory tract infections (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 May 1;60[9]:1308-16).

Prescribing practices varied by region, with the highest rates in the South. Don’t think I’m judging. I live in Kentucky, the state with the highest rate of antibiotic prescribing at 1,281 prescriptions per 1,000 persons. Is it any wonder that we’re seeing kids with very resistant infections?

The CDC estimates that at least two million people in the United States are infected annually with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and at least 23,000 of them die as a result of these infections. It is estimated that prevention strategies that include better antibiotic prescribing could prevent as many as 619,000 infections and 37,000 deaths over 5 years. Fortunately, my little patient recovered fully, but it has made me think about antimicrobial stewardship, especially its role in the outpatient setting.

According the American Academy of Pediatrics, the goal of antimicrobial stewardship is “to optimize antimicrobial use, with the aim of decreasing inappropriate use that leads to unwarranted toxicity and to selection and spread of resistant organisms.”

Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) are increasingly common in inpatient settings and have been shown to reduce antibiotic use. These programs can take many forms. The hospital where I work relies primarily on clinical guidelines emphasizing appropriate empiric therapy for a variety of common conditions. Other hospitals employ prospective audit and feedback, as well as a restricted formulary. Medicare and Medicaid Conditions of Participation will soon require hospitals that receive funds from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have an ASP.

Comparatively little has been published about ASPs in the outpatient setting. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that effective strategies include patient education, provider education, provider audit and feedback, and clinical decision support. We have at least some data that these work, at least in a research setting.

From 2000 to 2003, a controlled, cluster-randomized trial in 16 Massachusetts communities demonstrated that a 3-year, multifaceted, community-level intervention was “modestly successful” in reducing antibiotic use (Pediatrics. 2008 Jan;121[1]:e15-23). As a part of this intervention, parents received education via direct mail and in primary care settings, pharmacies, and child care centers while physicians received small-group education, frequent updates and educational materials, and prescribing feedback. Antibiotic prescribing was measured via health insurance claims data from all children who were 6 years of age or younger and resided in study communities, and were insured by one of four participating health plans. Coincident with the intervention, there was 4.2% decrease in antibiotic prescribing among children aged 24 to <48 months and a 6.7% decrease among those aged 48-72 months. The effect was greatest among Medicaid-insured children.

More recently, 18 primary care practices in Pennsylvania and New Jersey were randomized to an intervention that consisted of a 1-hour, on-site education session followed by 1 year of personalized, quarterly audit and feedback of prescribing for bacterial and viral acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs), or usual practice (JAMA. 2013 Jun 12;309[22]:2345-52). The prescribing practices of 162 clinicians were included in the analysis.

Broad spectrum–antibiotic prescribing decreased in intervention practices, compared with controls (26.8% to 14.3% among intervention practices vs. 28.4% to 22.6% in controls), as did “off-guideline” prescribing for pneumonia and acute sinusitis. Antibiotic prescribing for viral infections was relatively low at baseline and did not change. The authors concluded that “extending antimicrobial stewardship to the ambulatory setting, where such programs have generally not been implemented, may have important health benefits.” Unfortunately, the positive effect in these practices was not sustained after the audit and feedback stopped (JAMA. 2014 Dec 17;312[23]:2569-70).

Not all antimicrobial stewardship interventions need to be time- and resource-intensive. Investigators in California found that providers who publicly pledged to reducing inappropriate antibiotic use for ARTIs by signing and posting a commitment letter in exam rooms actually prescribed fewer inappropriate antibiotic courses for their adult patients (JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Mar;174[3]:425-31).

“When you have a cough, sore throat, or other illness, your doctor will help you select the best possible treatments. If an antibiotic would do more harm than good, your doctor will explain this to you, and may offer other treatments that are better for you,” the letter read in part. There was a 19.7 absolute percentage reduction in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for ARTIs among clinicians randomized to the commitment letter invention relative to controls.

Can antimicrobial strategies work in the “real” world, in a busy pediatrician’s office? According to Dr. Patricia Purcell, a physician with East Louisville Pediatrics in Louisville, Ky., the answer is “yes.”

“We actually start with education in the newborn period,” Dr. Purcell said. “We let parents know that we are not going to call in antibiotics over the phone, and we’re not going to prescribe them for an upper respiratory tract infection.”

Dr. Purcell and her partners have committed to following evidence-based guidelines for antibiotic practices, such as the AAP’s guidelines for otitis media and sinusitis. She also noted that at least one major insurance company is starting to provide the group feedback about their antibiotic-prescribing practices. “They want to make sure we are not prescribing antibiotics for viruses,” she said.

Still, the message that antibiotics are not always the answer can be a bitter pill for some parents to swallow. A pediatrician friend in Alabama notes: “I have these conversations every day, and a lot of parents are mad at me for not prescribing antibiotics for their child’s ‘terrible cold.’” Another friend notes that watchful waiting can be a burden for parents who have high copays or difficulties with transportation.

Still, many parents would welcome a frank discussion about the risks and benefits of antibiotics. After I shared some of the CDC information for parents with a nursing colleague, she told me that her daughter recently had a febrile illness and was diagnosed with otitis media. “I don’t like giving my kids meds they don’t need,” she told me. “However, if the doc says they need antibiotics and they prescribe them, I give them. I never say, ‘Do we really need antibiotics for that?’”

Now she is rethinking that approach. “Was 10 days of amoxicillin necessary for a ‘red’ eardrum?! I’m just a mom. ... I don’t know the answer to that! Was her ear red because she had been crying or because of her fever? Did she get ‘treatment’ she did not need? Did the doctor give me antibiotics without education because she assumed that is why I brought her in?”

This year’s “Get Smart About Antibiotics Week” was Nov. 16-22. This annual 1-week observance is intended to raise awareness of the threat of antibiotic resistance and the importance of appropriate prescribing and use. Kudos if you celebrated this in your office. If you missed it, it’s not too late to check out some of the activities suggested by the CDC, and try one or two in your own practice. Email me with your ideas about stewardship in the outpatient setting, and I’ll try to feature at least some of them in a future column.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. Dr. Bryant disclosed that she has been an investigator for clinical trials funded by Pfizer for the past 2 years. Email her at [email protected].

I was recently asked to evaluate a young child with a urinary tract infection caused by an extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Escherichia coli.

I’d just broken the bad news to the mother: There was no oral medication available to treat the baby, so she’d have to stay in the hospital for a full intravenous course.

“Has your child been treated with antibiotics recently?” I asked the mother, wondering how the baby had come to have such a resistant infection.

“She had a couple days of runny nose and a low-grade fever a couple of weeks ago,” she told me. “Her doctor treated her for a sinus infection.”

In 2011, doctors in outpatient settings across the United States wrote 262.5 million prescriptions for antibiotics – 73.7 million for children – and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 50% of these were completely unnecessary because they were prescribed for viral respiratory tract infections (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 May 1;60[9]:1308-16).

Prescribing practices varied by region, with the highest rates in the South. Don’t think I’m judging. I live in Kentucky, the state with the highest rate of antibiotic prescribing at 1,281 prescriptions per 1,000 persons. Is it any wonder that we’re seeing kids with very resistant infections?

The CDC estimates that at least two million people in the United States are infected annually with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and at least 23,000 of them die as a result of these infections. It is estimated that prevention strategies that include better antibiotic prescribing could prevent as many as 619,000 infections and 37,000 deaths over 5 years. Fortunately, my little patient recovered fully, but it has made me think about antimicrobial stewardship, especially its role in the outpatient setting.

According the American Academy of Pediatrics, the goal of antimicrobial stewardship is “to optimize antimicrobial use, with the aim of decreasing inappropriate use that leads to unwarranted toxicity and to selection and spread of resistant organisms.”

Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) are increasingly common in inpatient settings and have been shown to reduce antibiotic use. These programs can take many forms. The hospital where I work relies primarily on clinical guidelines emphasizing appropriate empiric therapy for a variety of common conditions. Other hospitals employ prospective audit and feedback, as well as a restricted formulary. Medicare and Medicaid Conditions of Participation will soon require hospitals that receive funds from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have an ASP.

Comparatively little has been published about ASPs in the outpatient setting. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that effective strategies include patient education, provider education, provider audit and feedback, and clinical decision support. We have at least some data that these work, at least in a research setting.

From 2000 to 2003, a controlled, cluster-randomized trial in 16 Massachusetts communities demonstrated that a 3-year, multifaceted, community-level intervention was “modestly successful” in reducing antibiotic use (Pediatrics. 2008 Jan;121[1]:e15-23). As a part of this intervention, parents received education via direct mail and in primary care settings, pharmacies, and child care centers while physicians received small-group education, frequent updates and educational materials, and prescribing feedback. Antibiotic prescribing was measured via health insurance claims data from all children who were 6 years of age or younger and resided in study communities, and were insured by one of four participating health plans. Coincident with the intervention, there was 4.2% decrease in antibiotic prescribing among children aged 24 to <48 months and a 6.7% decrease among those aged 48-72 months. The effect was greatest among Medicaid-insured children.

More recently, 18 primary care practices in Pennsylvania and New Jersey were randomized to an intervention that consisted of a 1-hour, on-site education session followed by 1 year of personalized, quarterly audit and feedback of prescribing for bacterial and viral acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs), or usual practice (JAMA. 2013 Jun 12;309[22]:2345-52). The prescribing practices of 162 clinicians were included in the analysis.

Broad spectrum–antibiotic prescribing decreased in intervention practices, compared with controls (26.8% to 14.3% among intervention practices vs. 28.4% to 22.6% in controls), as did “off-guideline” prescribing for pneumonia and acute sinusitis. Antibiotic prescribing for viral infections was relatively low at baseline and did not change. The authors concluded that “extending antimicrobial stewardship to the ambulatory setting, where such programs have generally not been implemented, may have important health benefits.” Unfortunately, the positive effect in these practices was not sustained after the audit and feedback stopped (JAMA. 2014 Dec 17;312[23]:2569-70).

Not all antimicrobial stewardship interventions need to be time- and resource-intensive. Investigators in California found that providers who publicly pledged to reducing inappropriate antibiotic use for ARTIs by signing and posting a commitment letter in exam rooms actually prescribed fewer inappropriate antibiotic courses for their adult patients (JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Mar;174[3]:425-31).

“When you have a cough, sore throat, or other illness, your doctor will help you select the best possible treatments. If an antibiotic would do more harm than good, your doctor will explain this to you, and may offer other treatments that are better for you,” the letter read in part. There was a 19.7 absolute percentage reduction in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for ARTIs among clinicians randomized to the commitment letter invention relative to controls.

Can antimicrobial strategies work in the “real” world, in a busy pediatrician’s office? According to Dr. Patricia Purcell, a physician with East Louisville Pediatrics in Louisville, Ky., the answer is “yes.”

“We actually start with education in the newborn period,” Dr. Purcell said. “We let parents know that we are not going to call in antibiotics over the phone, and we’re not going to prescribe them for an upper respiratory tract infection.”

Dr. Purcell and her partners have committed to following evidence-based guidelines for antibiotic practices, such as the AAP’s guidelines for otitis media and sinusitis. She also noted that at least one major insurance company is starting to provide the group feedback about their antibiotic-prescribing practices. “They want to make sure we are not prescribing antibiotics for viruses,” she said.

Still, the message that antibiotics are not always the answer can be a bitter pill for some parents to swallow. A pediatrician friend in Alabama notes: “I have these conversations every day, and a lot of parents are mad at me for not prescribing antibiotics for their child’s ‘terrible cold.’” Another friend notes that watchful waiting can be a burden for parents who have high copays or difficulties with transportation.

Still, many parents would welcome a frank discussion about the risks and benefits of antibiotics. After I shared some of the CDC information for parents with a nursing colleague, she told me that her daughter recently had a febrile illness and was diagnosed with otitis media. “I don’t like giving my kids meds they don’t need,” she told me. “However, if the doc says they need antibiotics and they prescribe them, I give them. I never say, ‘Do we really need antibiotics for that?’”

Now she is rethinking that approach. “Was 10 days of amoxicillin necessary for a ‘red’ eardrum?! I’m just a mom. ... I don’t know the answer to that! Was her ear red because she had been crying or because of her fever? Did she get ‘treatment’ she did not need? Did the doctor give me antibiotics without education because she assumed that is why I brought her in?”

This year’s “Get Smart About Antibiotics Week” was Nov. 16-22. This annual 1-week observance is intended to raise awareness of the threat of antibiotic resistance and the importance of appropriate prescribing and use. Kudos if you celebrated this in your office. If you missed it, it’s not too late to check out some of the activities suggested by the CDC, and try one or two in your own practice. Email me with your ideas about stewardship in the outpatient setting, and I’ll try to feature at least some of them in a future column.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. Dr. Bryant disclosed that she has been an investigator for clinical trials funded by Pfizer for the past 2 years. Email her at [email protected].