User login

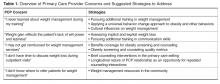

Overcoming Challenges to Obesity Counseling: Suggestions for the Primary Care Provider

From the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research Southeast, Atlanta, GA (Dr. Lewis) and the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (Dr. Gudzune).

Abstract

- Objective: To review challenges to obesity counseling in the primary care setting and suggest potential solutions.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: There are many challenges to obesity counseling in the primary care setting, including lack of primary care provider (PCP) training, provider weight bias, lack of reimbursement, lack of time during outpatient encounters, and limited ability to refer patients to structured weight loss support programs. However, there are potential solutions to overcome these challenges. By seeking continuing medical education on weight management and communication skills, PCPs can address any training gaps and establish rapport with patients when delivering obesity counseling. Recent policy changes including Medicare coverage of obesity counseling visits may reduce PCPs' concern about lack of reimbursement and time, and the rise of new models of care delivery and reimbursement, such as patient-centered medical homes or accountable care organizations, may facilitate referrals to ancillary providers like registered dietitians or multi-component weight loss programs.

- Conclusion: Although providers face several challenges in delivering effective obesity counseling, PCPs may overcome these obstacles by pursuing continuing medical education in this area and taking advantage of new health care benefits coverage and care delivery models.

Over one-third of U.S. adults are now obese [1] and the prevalence of obesity is rising globally (2). In 2003 and 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued a recommendation that health care providers screen all patients for obesity and offer intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions to obese patients [3,4]. Screening for obesity typically involves assessment and classification of a patient’s body mass index (BMI). In the primary care setting, weight management may include a range of therapeutic options such as intensive behavioral counseling, prescription anti-obesity medications, and referral to bariatric surgery. Behavioral interventions typically include activities such as goal setting, diet and exercise change, and self-monitoring. A recent systematic review showed that primary care–based behavioral interventions could result in modest weight losses of 3 kg over a 12-month period, and prevent the development of diabetes and hypertension in at-risk patients [5].

PCP Concern: “I never learned about weight management during my training”

One of the most common barriers to providing the recommended counseling reported by health care providers is inadequate training in nutrition, exercise, and weight loss counseling [10–12]. Many providers have knowledge deficiencies in basic weight management [13,14]. In addition, few PCPs who have received obesity-related training rate that training as good quality during medical school (23%) and residency (35%) [15].

Pursuing Additional Training in Weight Management

Providers could address their lack of training in weight management by participating in an obesity curriculum. When surveyed, PCPs have identified that additional training in nutrition counseling (93%) and exercise counseling (92%) would help them improve the care for obese patients, and many (60%) reported receiving good continuing medical education (CME) on this topic [15]. Much research in this area has examined the impact of such training on residents’ provision of obesity counseling. Residents who completed training improved the quality of obesity care that they provided [16], and those who learned appropriate obesity screening and counseling practices were more likely to report discussing lifestyle changes with their patients [17]. The vast majority of surveyed PCPs (86%) also felt that motivational interviewing [15], a technique that can effectively promote weight loss, would help them improve obesity care [18,19]. Patients demonstrated greater confidence in their ability to change their diet when their PCP used motivational interviewing–consistent techniques during counseling [20]; however, few PCPs utilize motivational interviewing techniques [20,21]. Offering CME opportunities for practicing PCPs to obtain skills in nutrition, exercise, and motivational interviewing would likely improve the quality of obesity care and weight loss counseling that are being delivered. PCPs could also consider attending an in-depth weight management and obesity

Applying a Universal Behavior Change Approach to Obesity and Other Behaviors

Another option may be encouraging PCPs to use a universal approach to behavioral counseling across multiple domains [22]. Using a single technique may lend familiarity and efficiency to the health care providers’ counseling [23]. The 5A’s—Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange—has been proposed as a possible “universal” strategy that has demonstrated efficacy in both smoking cessation [24] and weight loss [25,26]. Using the 5A’s has been associated with increased motivation to lose weight [25] and increased weight loss [26]. Many physicians are familiar with the 5A’s; however, few physicians use the complete technique. PCPs have been found to most frequently “assess” and “advise” when using the 5A’s technique for weight loss counseling [26,27], although assisting and arranging are the components that have been associated with dietary change and weight loss [26]. PCPs could incorporate these A’s into their counseling routine by ensuring that they “assist” the patient by establishing appropriate lifestyle changes (eg, calorie tracking to achieve a 500 to 1000 calorie reduction per day) or referring to a weight loss program, and “arrange” for follow-up by scheduling an appointment in a few weeks to discuss the patient’s progress [23]. While the 5A’s can effectively promote weight loss, many PCPs would likely require training or retraining in this method to ensure its proper use. For PCPs interested in integrating the 5A’s into their weight management practice, we refer them to the algorithm described by Serdula and colleagues [23].

Cultural Influences on Weight Management

A final weight management training consideration relates to cultural awareness for patients who are from different racial or ethnic backgrounds than the PCP. In the United States, racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately burdened by obesity. Nearly 60% of non-Hispanic black women and 41% of Hispanic women are obese, compared with 33% of non-Hispanic whites [28]. Despite this fact, obese non-Hispanic black and Hispanic patients are more likely than white patients to perceive themselves as “slightly overweight” and to rate their health as good to excellent despite their obesity [29,30]. As a result, they may be less likely to seek out weight loss strategies on their own or ask for weight control advice from their providers [31]. Additionally, racial and ethnic disparities in access to healthy foods [32,33], safe areas for engaging in physical activity [34], and lack of social support for healthy behaviors may make it much more difficult for some minority patients to act on their PCP's advice.

Because of different cultures, social influences, and norms, what an individual patient perceives as obese or unhealthy may differ dramatically from what his or her physician views as obese or unhealthy [35–38]. Therefore, it is important that PCPs have a discussion with their patients about their subjective weight and health perceptions before beginning any prescriptive weight management strategies or discussions of “normal BMI” [39,40]. If an obese patient views herself as being at a normal weight for her culture, she is unlikely to respond well to being told by her doctor that she needs to lose 40 pounds to get to a healthy weight. Recent research suggests that alternative goals, such as encouraging weight maintenance for non-Hispanic black women, may be a successful alternative to the traditional pathway of encouraging weight loss [41].

In addition to understanding cultural context during weight status discussions, it is also important to give behavior change advice that is sensitive to the culture, race, and ethnicity of the patient. Dietary recommendations should take into account the patient’s culture. For example, Lindbergh et al have noted that cooking in traditional Hispanic culture does not rely as much on measurements as does cooking for non-Hispanic whites [42]. Therefore, measurement-based dietary advice (the cornerstone of portion control) may be a more problematic concept for these patients to incorporate into their home cooking styles [42]. Physical activity recommendations should also be given in context of cultural acceptability. A recent study by Hall and others concluded that some African-American women may be reluctant to follow exercise advice for fear that sweating will ruin their hairstyles [43]. Although providers need not be experts on the cultural norms of all of their patients, they should be open to discussing them, and to asking about the patient’s goals, ideal body type, comfort with physical activity, diet advice and other issues that will make individualized counseling much more effective.

PCP Concern: “Weight gain reflects the patient’s lack of will power and laziness”

Bias towards obese patients has been documented among health care providers [44,45]. Studies have shown that some providers have less respect for obese patients [46], perceive obese patients as nonadherent to medications [47], and associate obesity with “laziness,” “stupidity,” and “worthlessness” [48]. Furthermore, obese patients identify physicians as a primary source of stigma [49] and many report stigmatizing experiences during interactions with the healthcare system [44,45]. In one study, a considerable proportion of obese patients reported ever experiencing stigma from a doctor (69%) or a nurse (46%) [49]. As a result of these negative experiences, obese patients have reported avoiding or delaying medical services such as gynecological cancer screening [50]. A recent study by Gudzune et al found that obese patients had significantly greater odds of “doctor shopping,” where individuals saw 5 or more primary care providers in a 2-year period [51]. This doctor shopping behavior may also be motivated by dissatisfaction with care, as focus groups of obese women have reported doctor shopping until they find a health care provider who is comfortable, experienced, and skilled in treating obese patients [50].

Assessing Implicit and Explicit Weight Bias

In addition to explicit negative attitudes, health care providers may also hold implicit biases towards obese patients [52]. A recent study found that over half of medical students held an implicit anti-fat bias [53]. These implicit attitudes may manifest more subtly during patient encounters. PCPs engage in less emotional rapport building during visits with overweight and obese patients as compared to normal weight patients [54], which include behaviors such as expressing empathy, concern, reassurance, and partnership. The lack of rapport building could negatively influence the patient-provider relationship and decrease the effectiveness of weight loss counseling. PCPs may need to consider undergoing self-assessment to determine whether or not they hold negative implicit and/or explicit attitudes towards obese patients. PCPs can complete the Weight Implicit Association Test (IAT) for free online at https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/demo/. To determine whether they hold negative explicit attitudes, PCPs can download and complete assessments offered by the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity (www.yaleruddcenter.org/resources/bias_toolkit/index.html).

Pursuing Additional Training in Communication Skills

If weight bias is indeed present, PCPs may benefit from additional training in communication skills as well as specific guidance on how to discuss weight loss with overweight and obese patients. For example, an observational study found that patients lost more weight when they had weight loss counseling visits with physicians who used motivational interviewing strategies [20,21]. Additional PCP training in this area would benefit the patient-provider relationship, as research has shown that such patient-centered communication strategies lead to greater patient satisfaction [55,56], improvement in some clinical outcomes [57,58], and less physician burnout [59]. In fact, some medical schools address student weight bias during their obesity curricula [60]. Building communication skills helps improve PCPs’ capacity to show concern and empathy for patients’ struggles, avoid judgment and criticism, and give emotional support and encouragement, which may all improve PCPs’ ability to execute more sensitive weight loss discussions. For providers who are more interested in CME opportunities, the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare offers an online interactive learning program in this area called “Doc Com” (http://doccom.aachonline.org/dnn/Home.aspx).

PCP Concern: “I may not get reimbursed for weight management services”

Traditional metrics for how doctors are reimbursed and how the quality of their care is measured have not promoted weight loss counseling by PCPs. Prior to 2012, physicians could not bill Medicare for obesity-specific counseling visits [61]. Given that many private insurers follow the lead of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for patterns of reimbursement, this issue has been pervasive in U.S. medical practice for a number of years, with considerable variability between plans on which obesity-related services are covered [62]. A recent study of U.S. health plans indicated that most would reject a claim for an office visit where obesity was the only coded diagnosis [62]. Additionally, the quality improvement movement has only recently begun to focus on issues of obesity. In 2009, the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s (NCQA) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) added 2 new measures pertaining to the documentation of a patient’s BMI status. Prior to this time, even the simple act of acknowledging obesity was routinely underperformed and quite variable across health plans in the United States [63].

Obesity Screening and Counseling Benefits Coverage

In 2012, CMS made a major coverage change decision when they agreed to reimburse providers for delivering intensive behavioral interventions for obesity [61]. Namely, CMS will now cover a 6-month series of visits for Medicare patients (weekly for month 1, every other week for months 2–6), followed by monthly visits for an additional 6 months in patients who have been able to lose 3 kg. For PCPs and other providers who have long hoped for more opportunity to discuss nutrition, weight, and physical activity with their Medicare patients, these policy changes are exciting. Hopefully, this move by CMS will stimulate similar changes in the private insurance market.

Greater reimbursement of obesity-related care is also more likely given the overall trend of the U.S. health care system—with the focus shifting away from traditional fee-for-service models that have de-emphasized preventive care and counseling and toward a model that rewards well care [64]. Large employer groups, who represent an important voice in any discussion of health insurance and reimbursement, are also increasingly interested in the use of wellness programs and weight loss to decrease their own health care costs. This trend could further stimulate insurers to cover programs that allow providers to engage in weight counseling as a way of attracting or retaining large employer groups as customers [62].

Obesity Screening and Counseling Quality Metrics

A parallel movement in the quality of care realm would serve to bolster any forthcoming changes in reimbursement. For example, an expansion of the HEDIS “wellness and health promotion” measures, or going beyond “BMI assessment” to include a brief assessment of key dietary factors or physical activity level as a routine quality measure, would go a long way toward emphasizing to payers and providers the need for more routine obesity counseling. Professional provider organizations have been increasingly engaged in this area as well. The recent recognition by the American Medical Association of obesity as a disease may also influence organizations such as the NCQA and payers who may be considering how to encourage providers to better address this important issue.

PCP Concern: “I don’t have time to discuss weight loss during outpatient visits”

The average continuity visit for an adult patient in the United States is about 20 minutes in duration, with a mean of 6 to 7 clinical items to be addressed during that time-period [65]. This leaves little time for providers to perform the necessary history and physical portions of the visit, educate patients on various topics, and write out prescriptions or referrals. Not surprisingly, such extreme time pressure leads many PCPs to feel overwhelmed and burned out [66], and the idea of adding another “to-do” to office visits may be resisted. For obese patients, many of whom are likely to have multiple chronic conditions, PCPs are faced with the task of both discussing active issues such as hypertension, diabetes, and sleep apnea, and also potentially discussing the patient’s weight status in a very brief amount of time. Under such time pressures, PCPs often adopt a “putting out fires” mentality and therefore tackle what they see as the most pressing issues—eg, deal with out of control blood pressure by adding a new medication, or lowering hemoglobin A1c by upping the insulin dose, rather than dealing with the 20-lb weight gain that might be leading to the high pressures and hyperglycemia.

Compounding this problem is the fact that well-delivered preventive health advice can be time-consuming, and with so many topics to choose from, it may be difficult for providers to know which issues make the most sense to prioritize [67]. A recent study estimated that PCPs routinely under-counsel patients about nutrition (an advice topic that earns a “B” rating from the USPSTF), while they over-counsel them on exercise and PSA testing (topics that earn an “I” rating from the USPSTF) [68]. Topics of discussion and the time spent on them may reflect patient priorities or PCP comfort with various issues, but it is clear that some improvements could be made to better utilize available time with patients.

In the face of time and resource pressures, many PCPs may not be ideally suited to deliver the kind of intensive behavioral weight loss interventions that are supported by the best scientific evidence [69]. In fact, there is little evidence to support even brief weight counseling sessions by PCPs [70]. However, for busy providers, there are several brief and potentially impactful tasks that could enable them to better support their obese patients.

Brief Counseling Interventions in the Primary Care Setting

First, primary care providers should routinely measure and discuss their patients BMIs as they would any other vital sign. In addition, other brief measures such as “Exercise as a Vital Sign” [71] can be incorporated into the visit, so that behaviors linked to weight can inform the strategy adopted and monitored over time. After a brief discussion is initiated, a referral can be placed for patients who wish to pursue more intense therapy for weight loss—this may be to behavioral health, nutrition, bariatric surgery or a comprehensive weight management clinic. Practices can support their providers by streamlining this referral process and educating providers and patients on available resources. PCPs also may be able to engage their patients in self-monitoring (eg, calorie tracking, exercise tracking, self weighing) so that most of the work and learning takes place outside of the primary care office. For example, PCPs can promote the use of a food diary, a practice that has been shown to improve weight loss success [72]. Review of the diary could take place at a separate visit with the PCP or in follow-up with a weight loss specialist or dietitian.

A major strength of the primary care setting is its longitudinal nature. Even if available time at individual visits is short, advice and support can be given repeatedly over a longer period of time than may often be achieved with a specialist consultant. For patients who are in the maintenance phase of weight loss, having long-term frequent contacts with a provider has been shown to prevent weight regain [73]. The use of group visits and physician extenders (RNs, NPs, PAs) for delivering obesity-related behavioral advice might offer another way to relieve some of the time pressures faced by PCPs in the one-on-one chronic disease management visit [69,74].

PCP Concern: “I don’t know where to refer patients for weight management”

Surveys of obese patients and their doctors indicate that PCPs may not often enough refer patients to structured weight loss programs or registered dietitians [75,76]. Furthermore, PCPs are often isolated from other providers who might be important in a team-based model of obesity care, such as pharmacists, registered dietitians, endocrinologists, and bariatric surgeons. The implementation of the Affordable Care Act, including payment reform and the rise of accountable care organizations, should begin changing the relative isolation of the PCP. If more practices attempt to conform to medical home models, the interconnectedness of PCPs to other health care team members may increase, thus facilitating a more team-based approach to obesity care and easier referrals to specialized team members [77].

Weight Management Resources

Aside from some academic centers and large private health care institutions, many primary care practices lack access to structured obesity care clinics that can help manage the challenges of guiding patients through their weight loss options. For providers who practice in areas that do not afford them easy access to obesity care clinics, it is worth seeking out available resources in the nonmedical community that might provide a structured support system for patients. One low-cost community-based program, Take Off Pounds Sensibly (TOPS; www.tops.org), can achieve and sustain a 6% weight loss for active members [78]. Groups such as Overeaters Anonymous are found in most U.S. cities, and have helpful websites including podcasts that patients can access even in the absence of a local branch (www.oa.org). Organizations like the YMCA, which have good penetration into most areas of the country, offer affordable access to physical activity and health programs including coaching that can promote all around healthier living and improved dietary habits (www.ymca.net). A final consideration could be referral to a commercial weight loss program. A 2005 review of the major U.S. commercial weight loss programs concluded that there was suboptimal evidence for or against these programs’ efficacy [79]. A recent randomized controlled trial showed that patients referred by their PCP to a commercial weight loss program (Weight Watchers) lost significantly more weight (2.3 kg) at 12 months as compared to patients who only received weight loss advice from their PCP [80]. However, it is important to keep in mind that not all commercial programs are the same and some programs can be ineffective or even dangerous for some patients. The PCP may need to take an active role monitoring their patient’s health and safety when using these programs.

A Strategy to Incorporate Weight Management into Current Practice

Summary

Given the obesity epidemic, PCPs will need to begin addressing weight loss as a part of their normal practice; however, providers face several challenges in implementing weight management services. Many PCPs report receiving inadequate training in weight management during their training; however, many CME opportunities exist for providers to reduce their knowledge and skills deficit. Depending upon the prevalence of obesity in their practice and interest in offering weight management services, PCPs may need to consider more intensive weight management training or even pursue certification as an obesity medicine provider through the American Board of Obesity Medicine. For providers with a more general interest in obesity counseling, applying a consistent counseling approach like the 5A’s to several behaviors (eg, obesity, smoking cessation) may facilitate such counseling as a regular part of the outpatient encounter. PCPs should also be aware of different cultural considerations with respect to obesity including different body image perceptions and cooking styles. Obesity bias is pervasive in our society; therefore, PCPs may similarly hold negative explicit or implicit attitudes towards these patients. Providers can engage in online self-assessment about their explicit and implicit biases in order to understand whether they hold any negative attitudes towards obese patients. Additional training in communication skills and empathy may improve these patient-provider relationships and translate into more effective behavioral counseling. PCPs may be concerned about a lack of reimbursement for weight management services or a lack of time to perform counseling during outpatient encounters. With the new obesity counseling benefits coverage by CMS, PCPs should be reimbursed for obesity counseling services and provide additional time through dedicated weight management visits for Medicare patients. The new primary care practice models including the patient-centered medical home may facilitate PCP referrals to other weight management providers such as registered dieticians and health coaches, which could offset the PCP’s time pressures. Finally, PCPs can consider referrals to community resources, such as programs like Overeaters Anonymous, TOPS or the YMCA, to help provide patients group support for behavior change. In summary, PCPs may need to consider additional training to be prepared to deliver high quality obesity care in collaboration with other local partners and weight management specialists.

Corresponding author: Kimberly A. Gudzune, MD, MPH, 2024 E. Monument St, Room 2-611, Baltimore, MD 21287, [email protected].

Funding/support: Dr. Gudzune received support through a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL116601).

Financial disclosures: None

1. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA 2012;307:491–7.

2. Stevens GA, Singh GM, Lu Y, et al. National, regional, and global rends in adult overweight and obesity prevalences. Popul Health Metr 2012;10:22.

3. McTigue KM, Harris R, Hemphill B, et al. Screening and interventions for obesity in adults: summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:933–49.

4. Moyer VA. Screening for and management of obesity in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:373–8.

5. LeBlanc ES, O’Conner E, Whitlock EP, et al. Effectiveness of primary care – relevant treatments for obesity in adults: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:434–47.

6. Jackson JE, Doescher MP, Saver BG, Hart LG. Trends in professional advice to lose weight among obese adults, 1994 to 2000. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:814–8.

7. McAlpine DD, Wilson AR. Trends in obesity-related counseling in primary care. Med Care 2007;45:322–9.

8. Bleich SN, Pickett-Blakley O, Cooper LA. Physician practice patterns of obesity diagnosis and weight-related counseling. Patient Educ Couns 2011;82:123–9.

9. Felix H, West DS, Bursac Z. Impact of USPSTF practice guidelines on provider weight loss counseling as reported by obese patients. Prev Med 2008;47:394–7.

10. Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med 1995;24:546–52.

11. Huang J, Yu H, Marin E, et al. Physicians’ weight loss counseling in two public hospital primary care clinics. Acad Med 2004;79:156–61.

12. Alexander SC, Ostbye T, Pollak KI, et al. Physicians’ beliefs about discussing obesity: results from focus groups. Am J Health Promot 2007;21:498–500.

13. Block JP, DeSalvo KB, Fisher WP. Are physicians equipped to address the obesity epidemic? Knowledge and attitudes of internal medicine residents. Prev Med 2003;36:669–75.

14. Jay M, Gillespie C, Ark T, et al. Do internists, pediatricians, and psychiatrists feel competent in obesity care?: using a needs assessment to drive curriculum design. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1066–70.

15. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, Cooper LA. National survey of US primary care physicians’ perspectives about causes of obesity and solutions to improve care. BMJ Open 2012;2(6).

16. Jay M, Schlair S, Caldwell R, et al. From the patient’s perspective: the impact of training on residnet physician’s obesity counseling. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:415–22.

17. Forman-Hoffman V, Little A, Wahls T. Barriers to obesity management: a pilot study of primary care clinicians. BMC Fam Pract 2006;7:35.

18. Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 2011;12:709–23.

19. Martins RK, McNeil DW. Review of motivational interviewing in promoting health behaviors. Clin Psychol Rev 2009;29:283–93.

20. Cox ME, Yancy WS Jr, Coffman CJ, et al. Effects of counseling techniques on patients’ weight-related attitudes and behaviors in a primary care clinic. Patient Educ Couns 2011;5:363–8.

21. Pollak KI, Alexander SC, Coffman CJ, et al. Physician communication techniques and weight loss in adults: Project CHAT. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:321–8.

22. Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med 2002;22:267–84.

23. Serdula MK, Khan LK, Dietz WH. Weight loss counseling revisited. J Amer Med Assoc 2003;289:1747–50.

24. Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update—clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008.

25. Jay M, Gillespie C, Schlair S, et al. Physicians’ use of the 5As in counseling obese patients: is the quality of counseling associated with patients’ motivation and intention to lose weight? BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:159.

26. Alexander SC, Cox ME, Boling Turner CL, et al Do the five A’s work when physicians counsel about weight loss? Fam Med 2011;43:179–84.

27. Flocke SA, Clark A, Schlessman K, Pomiecko G. Exercise, diet, and weight loss advice in the family medicine outpatient setting. Fam Med 2005;37:415–21.

28. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009-2010. NCHS Data Brief 2012;(82):1–8.

29. Burroughs VJ, et al. Self-reported comorbidities among self-described overweight African-American and Hispanic adults in the United States: results of a national survey. Obesity 2008;16:1400–6.

30. Dorsey RR, Eberhardt MS, Ogden CL. Racial/ethnic differences in weight perception. Obesity 2009;17:790–5.

31. Dorsey RR, Eberhardt MS, Ogden CL. Racial and ethnic differences in weight management behavior by weight perception status. Ethnic Dis 2010;20:244–50.

32. Baker EA, Schootman M, Barnidge E, Kelly C. The role of race and poverty in access to foods that enable individuals to adhere to dietary guidelines. Prev Chronic Dis 2006;3(3):A76.

33. Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:74–81.

34. Gordon-Larsen P, et al. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics 2006;117:417–24.

35. Kumanyika S, Wilson JF, Guilford-Davenport M. Weight-related attitudes and behaviors of black women. J Am Dietetic Assoc 1993;93:416–22.

36. Chithambo TP, Huey SJ. Black/white differences in perceived weight and attractiveness among overweight women. J Obes 2013;2013:320–6.

37. Paeratakul S, et al. Sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and BMI in relation to self-perception of overweight. Obesity Res 2002;10:345–50.

38. Bennett GG, et al. Attitudes regarding overweight, exercise, and health among blacks (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2006;17:95–101.

39. Kumanyika SK, et al. Expanding the obesity research paradigm to reach African American communities. Prev Chronic Disease 2007;4(4).

40. Stuart-Shor EM, Berra KA, Kamau MW, Kumanyika SK. Behavioral strategies for cardiovascular risk reduction in diverse and underserved racial/ethnic groups. Circulation 2012;125:171–84.

41. Bennett GG, Foley P, Levine E, et al. Behavioral treatment for weight gain prevention among black women in primary care practice: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1770–7.

42. Lindberg NM, Stevens VJ, Halperin RO. Weight-loss interventions for Hispanic populations: the role of culture. J Obes 2012:542736.

43. Hall RR, et al. Hair care practices as a barrier to physical activity in African American women. JAMA Dermatology 2013;149:310–4.

44. Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res 2001;9:788–905.

45. Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:941–64.

46. Huizinga MM, Cooper LA, Bleich SN, et al. Physician respect for patients with obesity. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:1236–9.

47. Huizinga MM, Bleich SN, Beach MC, et al. Disparity in physician perception of patients’ adherence to medications by obesity status. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:1932–7.

48. Schwartz MB, Chambliss HO, Brownell KD, et al. Weight bias among health professionals specializing in obesity. Obes Res 2003;11:1033–9.

49. Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: an investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1802–15.

50. Amy NK, Aalborg A, Lyons P, Keranen L. Barriers to routine gynecological cancer screening for White and African-American obese women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:147–55.

51. Gudzune KA, Bleich SN, Richards TM, et al. Doctor shopping by overweight and obese patients is associated with increased healthcare utilization. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:1328–34.

52. Teachman BA, Brownell KD. Implicit anti-fat bias among health professionals: is anyone immune? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001;25:1525–31.

53. Miller DP Jr, Spangler JG, Vitolins MZ, et al. Are medical students aware of their anti-obesity bias? Acad Med 2013;88:978–82.

54. Gudzune KA, Beach MC, Roter DL, Cooper LA. Physicians build less rapport with obese patients. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:2146–52.

55. Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract 2002;15:25–38.

56. Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, et al. Interventions for providers to promote patient-center approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD003267.

57. Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ 1995;152:1423–33.

58. Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, et al. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med 2011;86:359–64.

59. Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA 2009;302:1284––93.

60. Vitolins MZ, Crandall S, Miller D, et al. Obesity educational interventions in U.S. medical schools: a systematic review and identified gaps. Teach Learn Med 2012;24:267–72.

61. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Decision memo for intensive behavioral therapy for obesity. 2012.

62. Simpson LA, Cooper J. Paying for obesity: a changing landscape. Pediatrics 2009;123 Suppl 5:5301–7.

63. Arterburn DE, et al. Body mass index measurement and obesity prevalence in ten U.S. health plans. Clin Med Res 2010;8:126–30.

64. Koh HK, Sebelius KG. Promoting prevention through the Affordable Care Act. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:1296–9.

65. Abbo ED, et al. The increasing number of clinical items addressed during the time of adult primary care visits. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:2058–65.

66. Mechanic D. Physician discontent: challenges and opportunities. JAMA 2003;290:941–6.

67. Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, et al. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health 2003;93:635–41.

68. Pollak KI, Krause KM, Yarnall KS, et al. Estimated time spent on preventive services by primary care physicians. BMC Health Services Research 2008;8:245.

69. Tsai AG, Wadden TA. Treatment of obesity in primary care practice in the United States: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:1073–9.

70. Carvajal R, Wadden TA, Tsai AG, et al. Managing obesity in primary care practice: a narrative review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2013;1281:191–06.

71. Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, et al. Initial validation of an exercise “vital sign” in electronic medical records. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:2071–6.

72. Butryn ML, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Consistent self-monitoring of weight: a key component of successful weight loss maintenance. Obesity 2007;15:3091–6.

73. Butryn ML, Webb V, Wadden TA. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Psych Clin North Am 2011;34:841–59.

74. Lavoie JG, Wong ST, Chongo M, et al. Group medical visits can deliver on patient-centered care objectives: results from a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:2013.

75. Wadden TA, Anderson DA, Foster GD, et al. Obese women’s perceptions of their physicians’ weight management attitudes and practices. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:854–60.

76. Phelan SP, et al. What do physicians recommend to their overweight and obese patients? J Am Board Fam Med 2009;22:115–22.

77. Grant RMA, Greene DD. The health care home model: primary health care meeting public health goals. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1096–103.

78. Mitchell NS, Dickinson LM, Kempe A, Tsai AG. Determining the effectiveness of Take Off Pounds Sensibly (TOPS), a nationally available nonprofit weight loss program. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:568–73.

79. Tsai AG, Wadden TA. Systematic review: An evaluation of major commercial weight loss programs in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:56–66.

80. Jebb SA, Ahern AL, Olson AD, et al. Primary care referral to a commercial provider for weight loss treatment versus standard care: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;378:1485–92.

81. Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008;27:379–87.

82. Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 2013;46:81–95.

83. Scott JG, Cohen D, DiCicco-Bloom B, et al. Speaking of weight: how patients and primary care clinicians initiate weight loss counseling. Prev Med 2004;38:819–27.

84. Brown I, Thompson J, Tod A, Jones G. Primary care support for tacking obesity: a qualitative study of the perceptions of obese patients. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:666–72.

85. Tailor A, Ogden J. Avoiding the term ‘obesity:’ an experimental study of the impact of doctors’ language on patients’ beliefs. Patient Educ Couns 2009;76:260–4.

86. Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Alexander SC, et al. Empathy goes a long way in weight loss discussions. J Fam Pract 2007;56:1031–6.

From the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research Southeast, Atlanta, GA (Dr. Lewis) and the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (Dr. Gudzune).

Abstract

- Objective: To review challenges to obesity counseling in the primary care setting and suggest potential solutions.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: There are many challenges to obesity counseling in the primary care setting, including lack of primary care provider (PCP) training, provider weight bias, lack of reimbursement, lack of time during outpatient encounters, and limited ability to refer patients to structured weight loss support programs. However, there are potential solutions to overcome these challenges. By seeking continuing medical education on weight management and communication skills, PCPs can address any training gaps and establish rapport with patients when delivering obesity counseling. Recent policy changes including Medicare coverage of obesity counseling visits may reduce PCPs' concern about lack of reimbursement and time, and the rise of new models of care delivery and reimbursement, such as patient-centered medical homes or accountable care organizations, may facilitate referrals to ancillary providers like registered dietitians or multi-component weight loss programs.

- Conclusion: Although providers face several challenges in delivering effective obesity counseling, PCPs may overcome these obstacles by pursuing continuing medical education in this area and taking advantage of new health care benefits coverage and care delivery models.

Over one-third of U.S. adults are now obese [1] and the prevalence of obesity is rising globally (2). In 2003 and 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued a recommendation that health care providers screen all patients for obesity and offer intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions to obese patients [3,4]. Screening for obesity typically involves assessment and classification of a patient’s body mass index (BMI). In the primary care setting, weight management may include a range of therapeutic options such as intensive behavioral counseling, prescription anti-obesity medications, and referral to bariatric surgery. Behavioral interventions typically include activities such as goal setting, diet and exercise change, and self-monitoring. A recent systematic review showed that primary care–based behavioral interventions could result in modest weight losses of 3 kg over a 12-month period, and prevent the development of diabetes and hypertension in at-risk patients [5].

PCP Concern: “I never learned about weight management during my training”

One of the most common barriers to providing the recommended counseling reported by health care providers is inadequate training in nutrition, exercise, and weight loss counseling [10–12]. Many providers have knowledge deficiencies in basic weight management [13,14]. In addition, few PCPs who have received obesity-related training rate that training as good quality during medical school (23%) and residency (35%) [15].

Pursuing Additional Training in Weight Management

Providers could address their lack of training in weight management by participating in an obesity curriculum. When surveyed, PCPs have identified that additional training in nutrition counseling (93%) and exercise counseling (92%) would help them improve the care for obese patients, and many (60%) reported receiving good continuing medical education (CME) on this topic [15]. Much research in this area has examined the impact of such training on residents’ provision of obesity counseling. Residents who completed training improved the quality of obesity care that they provided [16], and those who learned appropriate obesity screening and counseling practices were more likely to report discussing lifestyle changes with their patients [17]. The vast majority of surveyed PCPs (86%) also felt that motivational interviewing [15], a technique that can effectively promote weight loss, would help them improve obesity care [18,19]. Patients demonstrated greater confidence in their ability to change their diet when their PCP used motivational interviewing–consistent techniques during counseling [20]; however, few PCPs utilize motivational interviewing techniques [20,21]. Offering CME opportunities for practicing PCPs to obtain skills in nutrition, exercise, and motivational interviewing would likely improve the quality of obesity care and weight loss counseling that are being delivered. PCPs could also consider attending an in-depth weight management and obesity

Applying a Universal Behavior Change Approach to Obesity and Other Behaviors

Another option may be encouraging PCPs to use a universal approach to behavioral counseling across multiple domains [22]. Using a single technique may lend familiarity and efficiency to the health care providers’ counseling [23]. The 5A’s—Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange—has been proposed as a possible “universal” strategy that has demonstrated efficacy in both smoking cessation [24] and weight loss [25,26]. Using the 5A’s has been associated with increased motivation to lose weight [25] and increased weight loss [26]. Many physicians are familiar with the 5A’s; however, few physicians use the complete technique. PCPs have been found to most frequently “assess” and “advise” when using the 5A’s technique for weight loss counseling [26,27], although assisting and arranging are the components that have been associated with dietary change and weight loss [26]. PCPs could incorporate these A’s into their counseling routine by ensuring that they “assist” the patient by establishing appropriate lifestyle changes (eg, calorie tracking to achieve a 500 to 1000 calorie reduction per day) or referring to a weight loss program, and “arrange” for follow-up by scheduling an appointment in a few weeks to discuss the patient’s progress [23]. While the 5A’s can effectively promote weight loss, many PCPs would likely require training or retraining in this method to ensure its proper use. For PCPs interested in integrating the 5A’s into their weight management practice, we refer them to the algorithm described by Serdula and colleagues [23].

Cultural Influences on Weight Management

A final weight management training consideration relates to cultural awareness for patients who are from different racial or ethnic backgrounds than the PCP. In the United States, racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately burdened by obesity. Nearly 60% of non-Hispanic black women and 41% of Hispanic women are obese, compared with 33% of non-Hispanic whites [28]. Despite this fact, obese non-Hispanic black and Hispanic patients are more likely than white patients to perceive themselves as “slightly overweight” and to rate their health as good to excellent despite their obesity [29,30]. As a result, they may be less likely to seek out weight loss strategies on their own or ask for weight control advice from their providers [31]. Additionally, racial and ethnic disparities in access to healthy foods [32,33], safe areas for engaging in physical activity [34], and lack of social support for healthy behaviors may make it much more difficult for some minority patients to act on their PCP's advice.

Because of different cultures, social influences, and norms, what an individual patient perceives as obese or unhealthy may differ dramatically from what his or her physician views as obese or unhealthy [35–38]. Therefore, it is important that PCPs have a discussion with their patients about their subjective weight and health perceptions before beginning any prescriptive weight management strategies or discussions of “normal BMI” [39,40]. If an obese patient views herself as being at a normal weight for her culture, she is unlikely to respond well to being told by her doctor that she needs to lose 40 pounds to get to a healthy weight. Recent research suggests that alternative goals, such as encouraging weight maintenance for non-Hispanic black women, may be a successful alternative to the traditional pathway of encouraging weight loss [41].

In addition to understanding cultural context during weight status discussions, it is also important to give behavior change advice that is sensitive to the culture, race, and ethnicity of the patient. Dietary recommendations should take into account the patient’s culture. For example, Lindbergh et al have noted that cooking in traditional Hispanic culture does not rely as much on measurements as does cooking for non-Hispanic whites [42]. Therefore, measurement-based dietary advice (the cornerstone of portion control) may be a more problematic concept for these patients to incorporate into their home cooking styles [42]. Physical activity recommendations should also be given in context of cultural acceptability. A recent study by Hall and others concluded that some African-American women may be reluctant to follow exercise advice for fear that sweating will ruin their hairstyles [43]. Although providers need not be experts on the cultural norms of all of their patients, they should be open to discussing them, and to asking about the patient’s goals, ideal body type, comfort with physical activity, diet advice and other issues that will make individualized counseling much more effective.

PCP Concern: “Weight gain reflects the patient’s lack of will power and laziness”

Bias towards obese patients has been documented among health care providers [44,45]. Studies have shown that some providers have less respect for obese patients [46], perceive obese patients as nonadherent to medications [47], and associate obesity with “laziness,” “stupidity,” and “worthlessness” [48]. Furthermore, obese patients identify physicians as a primary source of stigma [49] and many report stigmatizing experiences during interactions with the healthcare system [44,45]. In one study, a considerable proportion of obese patients reported ever experiencing stigma from a doctor (69%) or a nurse (46%) [49]. As a result of these negative experiences, obese patients have reported avoiding or delaying medical services such as gynecological cancer screening [50]. A recent study by Gudzune et al found that obese patients had significantly greater odds of “doctor shopping,” where individuals saw 5 or more primary care providers in a 2-year period [51]. This doctor shopping behavior may also be motivated by dissatisfaction with care, as focus groups of obese women have reported doctor shopping until they find a health care provider who is comfortable, experienced, and skilled in treating obese patients [50].

Assessing Implicit and Explicit Weight Bias

In addition to explicit negative attitudes, health care providers may also hold implicit biases towards obese patients [52]. A recent study found that over half of medical students held an implicit anti-fat bias [53]. These implicit attitudes may manifest more subtly during patient encounters. PCPs engage in less emotional rapport building during visits with overweight and obese patients as compared to normal weight patients [54], which include behaviors such as expressing empathy, concern, reassurance, and partnership. The lack of rapport building could negatively influence the patient-provider relationship and decrease the effectiveness of weight loss counseling. PCPs may need to consider undergoing self-assessment to determine whether or not they hold negative implicit and/or explicit attitudes towards obese patients. PCPs can complete the Weight Implicit Association Test (IAT) for free online at https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/demo/. To determine whether they hold negative explicit attitudes, PCPs can download and complete assessments offered by the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity (www.yaleruddcenter.org/resources/bias_toolkit/index.html).

Pursuing Additional Training in Communication Skills

If weight bias is indeed present, PCPs may benefit from additional training in communication skills as well as specific guidance on how to discuss weight loss with overweight and obese patients. For example, an observational study found that patients lost more weight when they had weight loss counseling visits with physicians who used motivational interviewing strategies [20,21]. Additional PCP training in this area would benefit the patient-provider relationship, as research has shown that such patient-centered communication strategies lead to greater patient satisfaction [55,56], improvement in some clinical outcomes [57,58], and less physician burnout [59]. In fact, some medical schools address student weight bias during their obesity curricula [60]. Building communication skills helps improve PCPs’ capacity to show concern and empathy for patients’ struggles, avoid judgment and criticism, and give emotional support and encouragement, which may all improve PCPs’ ability to execute more sensitive weight loss discussions. For providers who are more interested in CME opportunities, the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare offers an online interactive learning program in this area called “Doc Com” (http://doccom.aachonline.org/dnn/Home.aspx).

PCP Concern: “I may not get reimbursed for weight management services”

Traditional metrics for how doctors are reimbursed and how the quality of their care is measured have not promoted weight loss counseling by PCPs. Prior to 2012, physicians could not bill Medicare for obesity-specific counseling visits [61]. Given that many private insurers follow the lead of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for patterns of reimbursement, this issue has been pervasive in U.S. medical practice for a number of years, with considerable variability between plans on which obesity-related services are covered [62]. A recent study of U.S. health plans indicated that most would reject a claim for an office visit where obesity was the only coded diagnosis [62]. Additionally, the quality improvement movement has only recently begun to focus on issues of obesity. In 2009, the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s (NCQA) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) added 2 new measures pertaining to the documentation of a patient’s BMI status. Prior to this time, even the simple act of acknowledging obesity was routinely underperformed and quite variable across health plans in the United States [63].

Obesity Screening and Counseling Benefits Coverage

In 2012, CMS made a major coverage change decision when they agreed to reimburse providers for delivering intensive behavioral interventions for obesity [61]. Namely, CMS will now cover a 6-month series of visits for Medicare patients (weekly for month 1, every other week for months 2–6), followed by monthly visits for an additional 6 months in patients who have been able to lose 3 kg. For PCPs and other providers who have long hoped for more opportunity to discuss nutrition, weight, and physical activity with their Medicare patients, these policy changes are exciting. Hopefully, this move by CMS will stimulate similar changes in the private insurance market.

Greater reimbursement of obesity-related care is also more likely given the overall trend of the U.S. health care system—with the focus shifting away from traditional fee-for-service models that have de-emphasized preventive care and counseling and toward a model that rewards well care [64]. Large employer groups, who represent an important voice in any discussion of health insurance and reimbursement, are also increasingly interested in the use of wellness programs and weight loss to decrease their own health care costs. This trend could further stimulate insurers to cover programs that allow providers to engage in weight counseling as a way of attracting or retaining large employer groups as customers [62].

Obesity Screening and Counseling Quality Metrics

A parallel movement in the quality of care realm would serve to bolster any forthcoming changes in reimbursement. For example, an expansion of the HEDIS “wellness and health promotion” measures, or going beyond “BMI assessment” to include a brief assessment of key dietary factors or physical activity level as a routine quality measure, would go a long way toward emphasizing to payers and providers the need for more routine obesity counseling. Professional provider organizations have been increasingly engaged in this area as well. The recent recognition by the American Medical Association of obesity as a disease may also influence organizations such as the NCQA and payers who may be considering how to encourage providers to better address this important issue.

PCP Concern: “I don’t have time to discuss weight loss during outpatient visits”

The average continuity visit for an adult patient in the United States is about 20 minutes in duration, with a mean of 6 to 7 clinical items to be addressed during that time-period [65]. This leaves little time for providers to perform the necessary history and physical portions of the visit, educate patients on various topics, and write out prescriptions or referrals. Not surprisingly, such extreme time pressure leads many PCPs to feel overwhelmed and burned out [66], and the idea of adding another “to-do” to office visits may be resisted. For obese patients, many of whom are likely to have multiple chronic conditions, PCPs are faced with the task of both discussing active issues such as hypertension, diabetes, and sleep apnea, and also potentially discussing the patient’s weight status in a very brief amount of time. Under such time pressures, PCPs often adopt a “putting out fires” mentality and therefore tackle what they see as the most pressing issues—eg, deal with out of control blood pressure by adding a new medication, or lowering hemoglobin A1c by upping the insulin dose, rather than dealing with the 20-lb weight gain that might be leading to the high pressures and hyperglycemia.

Compounding this problem is the fact that well-delivered preventive health advice can be time-consuming, and with so many topics to choose from, it may be difficult for providers to know which issues make the most sense to prioritize [67]. A recent study estimated that PCPs routinely under-counsel patients about nutrition (an advice topic that earns a “B” rating from the USPSTF), while they over-counsel them on exercise and PSA testing (topics that earn an “I” rating from the USPSTF) [68]. Topics of discussion and the time spent on them may reflect patient priorities or PCP comfort with various issues, but it is clear that some improvements could be made to better utilize available time with patients.

In the face of time and resource pressures, many PCPs may not be ideally suited to deliver the kind of intensive behavioral weight loss interventions that are supported by the best scientific evidence [69]. In fact, there is little evidence to support even brief weight counseling sessions by PCPs [70]. However, for busy providers, there are several brief and potentially impactful tasks that could enable them to better support their obese patients.

Brief Counseling Interventions in the Primary Care Setting

First, primary care providers should routinely measure and discuss their patients BMIs as they would any other vital sign. In addition, other brief measures such as “Exercise as a Vital Sign” [71] can be incorporated into the visit, so that behaviors linked to weight can inform the strategy adopted and monitored over time. After a brief discussion is initiated, a referral can be placed for patients who wish to pursue more intense therapy for weight loss—this may be to behavioral health, nutrition, bariatric surgery or a comprehensive weight management clinic. Practices can support their providers by streamlining this referral process and educating providers and patients on available resources. PCPs also may be able to engage their patients in self-monitoring (eg, calorie tracking, exercise tracking, self weighing) so that most of the work and learning takes place outside of the primary care office. For example, PCPs can promote the use of a food diary, a practice that has been shown to improve weight loss success [72]. Review of the diary could take place at a separate visit with the PCP or in follow-up with a weight loss specialist or dietitian.

A major strength of the primary care setting is its longitudinal nature. Even if available time at individual visits is short, advice and support can be given repeatedly over a longer period of time than may often be achieved with a specialist consultant. For patients who are in the maintenance phase of weight loss, having long-term frequent contacts with a provider has been shown to prevent weight regain [73]. The use of group visits and physician extenders (RNs, NPs, PAs) for delivering obesity-related behavioral advice might offer another way to relieve some of the time pressures faced by PCPs in the one-on-one chronic disease management visit [69,74].

PCP Concern: “I don’t know where to refer patients for weight management”

Surveys of obese patients and their doctors indicate that PCPs may not often enough refer patients to structured weight loss programs or registered dietitians [75,76]. Furthermore, PCPs are often isolated from other providers who might be important in a team-based model of obesity care, such as pharmacists, registered dietitians, endocrinologists, and bariatric surgeons. The implementation of the Affordable Care Act, including payment reform and the rise of accountable care organizations, should begin changing the relative isolation of the PCP. If more practices attempt to conform to medical home models, the interconnectedness of PCPs to other health care team members may increase, thus facilitating a more team-based approach to obesity care and easier referrals to specialized team members [77].

Weight Management Resources

Aside from some academic centers and large private health care institutions, many primary care practices lack access to structured obesity care clinics that can help manage the challenges of guiding patients through their weight loss options. For providers who practice in areas that do not afford them easy access to obesity care clinics, it is worth seeking out available resources in the nonmedical community that might provide a structured support system for patients. One low-cost community-based program, Take Off Pounds Sensibly (TOPS; www.tops.org), can achieve and sustain a 6% weight loss for active members [78]. Groups such as Overeaters Anonymous are found in most U.S. cities, and have helpful websites including podcasts that patients can access even in the absence of a local branch (www.oa.org). Organizations like the YMCA, which have good penetration into most areas of the country, offer affordable access to physical activity and health programs including coaching that can promote all around healthier living and improved dietary habits (www.ymca.net). A final consideration could be referral to a commercial weight loss program. A 2005 review of the major U.S. commercial weight loss programs concluded that there was suboptimal evidence for or against these programs’ efficacy [79]. A recent randomized controlled trial showed that patients referred by their PCP to a commercial weight loss program (Weight Watchers) lost significantly more weight (2.3 kg) at 12 months as compared to patients who only received weight loss advice from their PCP [80]. However, it is important to keep in mind that not all commercial programs are the same and some programs can be ineffective or even dangerous for some patients. The PCP may need to take an active role monitoring their patient’s health and safety when using these programs.

A Strategy to Incorporate Weight Management into Current Practice

Summary

Given the obesity epidemic, PCPs will need to begin addressing weight loss as a part of their normal practice; however, providers face several challenges in implementing weight management services. Many PCPs report receiving inadequate training in weight management during their training; however, many CME opportunities exist for providers to reduce their knowledge and skills deficit. Depending upon the prevalence of obesity in their practice and interest in offering weight management services, PCPs may need to consider more intensive weight management training or even pursue certification as an obesity medicine provider through the American Board of Obesity Medicine. For providers with a more general interest in obesity counseling, applying a consistent counseling approach like the 5A’s to several behaviors (eg, obesity, smoking cessation) may facilitate such counseling as a regular part of the outpatient encounter. PCPs should also be aware of different cultural considerations with respect to obesity including different body image perceptions and cooking styles. Obesity bias is pervasive in our society; therefore, PCPs may similarly hold negative explicit or implicit attitudes towards these patients. Providers can engage in online self-assessment about their explicit and implicit biases in order to understand whether they hold any negative attitudes towards obese patients. Additional training in communication skills and empathy may improve these patient-provider relationships and translate into more effective behavioral counseling. PCPs may be concerned about a lack of reimbursement for weight management services or a lack of time to perform counseling during outpatient encounters. With the new obesity counseling benefits coverage by CMS, PCPs should be reimbursed for obesity counseling services and provide additional time through dedicated weight management visits for Medicare patients. The new primary care practice models including the patient-centered medical home may facilitate PCP referrals to other weight management providers such as registered dieticians and health coaches, which could offset the PCP’s time pressures. Finally, PCPs can consider referrals to community resources, such as programs like Overeaters Anonymous, TOPS or the YMCA, to help provide patients group support for behavior change. In summary, PCPs may need to consider additional training to be prepared to deliver high quality obesity care in collaboration with other local partners and weight management specialists.

Corresponding author: Kimberly A. Gudzune, MD, MPH, 2024 E. Monument St, Room 2-611, Baltimore, MD 21287, [email protected].

Funding/support: Dr. Gudzune received support through a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL116601).

Financial disclosures: None

From the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research Southeast, Atlanta, GA (Dr. Lewis) and the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (Dr. Gudzune).

Abstract

- Objective: To review challenges to obesity counseling in the primary care setting and suggest potential solutions.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: There are many challenges to obesity counseling in the primary care setting, including lack of primary care provider (PCP) training, provider weight bias, lack of reimbursement, lack of time during outpatient encounters, and limited ability to refer patients to structured weight loss support programs. However, there are potential solutions to overcome these challenges. By seeking continuing medical education on weight management and communication skills, PCPs can address any training gaps and establish rapport with patients when delivering obesity counseling. Recent policy changes including Medicare coverage of obesity counseling visits may reduce PCPs' concern about lack of reimbursement and time, and the rise of new models of care delivery and reimbursement, such as patient-centered medical homes or accountable care organizations, may facilitate referrals to ancillary providers like registered dietitians or multi-component weight loss programs.

- Conclusion: Although providers face several challenges in delivering effective obesity counseling, PCPs may overcome these obstacles by pursuing continuing medical education in this area and taking advantage of new health care benefits coverage and care delivery models.

Over one-third of U.S. adults are now obese [1] and the prevalence of obesity is rising globally (2). In 2003 and 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued a recommendation that health care providers screen all patients for obesity and offer intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions to obese patients [3,4]. Screening for obesity typically involves assessment and classification of a patient’s body mass index (BMI). In the primary care setting, weight management may include a range of therapeutic options such as intensive behavioral counseling, prescription anti-obesity medications, and referral to bariatric surgery. Behavioral interventions typically include activities such as goal setting, diet and exercise change, and self-monitoring. A recent systematic review showed that primary care–based behavioral interventions could result in modest weight losses of 3 kg over a 12-month period, and prevent the development of diabetes and hypertension in at-risk patients [5].

PCP Concern: “I never learned about weight management during my training”

One of the most common barriers to providing the recommended counseling reported by health care providers is inadequate training in nutrition, exercise, and weight loss counseling [10–12]. Many providers have knowledge deficiencies in basic weight management [13,14]. In addition, few PCPs who have received obesity-related training rate that training as good quality during medical school (23%) and residency (35%) [15].

Pursuing Additional Training in Weight Management

Providers could address their lack of training in weight management by participating in an obesity curriculum. When surveyed, PCPs have identified that additional training in nutrition counseling (93%) and exercise counseling (92%) would help them improve the care for obese patients, and many (60%) reported receiving good continuing medical education (CME) on this topic [15]. Much research in this area has examined the impact of such training on residents’ provision of obesity counseling. Residents who completed training improved the quality of obesity care that they provided [16], and those who learned appropriate obesity screening and counseling practices were more likely to report discussing lifestyle changes with their patients [17]. The vast majority of surveyed PCPs (86%) also felt that motivational interviewing [15], a technique that can effectively promote weight loss, would help them improve obesity care [18,19]. Patients demonstrated greater confidence in their ability to change their diet when their PCP used motivational interviewing–consistent techniques during counseling [20]; however, few PCPs utilize motivational interviewing techniques [20,21]. Offering CME opportunities for practicing PCPs to obtain skills in nutrition, exercise, and motivational interviewing would likely improve the quality of obesity care and weight loss counseling that are being delivered. PCPs could also consider attending an in-depth weight management and obesity

Applying a Universal Behavior Change Approach to Obesity and Other Behaviors

Another option may be encouraging PCPs to use a universal approach to behavioral counseling across multiple domains [22]. Using a single technique may lend familiarity and efficiency to the health care providers’ counseling [23]. The 5A’s—Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange—has been proposed as a possible “universal” strategy that has demonstrated efficacy in both smoking cessation [24] and weight loss [25,26]. Using the 5A’s has been associated with increased motivation to lose weight [25] and increased weight loss [26]. Many physicians are familiar with the 5A’s; however, few physicians use the complete technique. PCPs have been found to most frequently “assess” and “advise” when using the 5A’s technique for weight loss counseling [26,27], although assisting and arranging are the components that have been associated with dietary change and weight loss [26]. PCPs could incorporate these A’s into their counseling routine by ensuring that they “assist” the patient by establishing appropriate lifestyle changes (eg, calorie tracking to achieve a 500 to 1000 calorie reduction per day) or referring to a weight loss program, and “arrange” for follow-up by scheduling an appointment in a few weeks to discuss the patient’s progress [23]. While the 5A’s can effectively promote weight loss, many PCPs would likely require training or retraining in this method to ensure its proper use. For PCPs interested in integrating the 5A’s into their weight management practice, we refer them to the algorithm described by Serdula and colleagues [23].

Cultural Influences on Weight Management

A final weight management training consideration relates to cultural awareness for patients who are from different racial or ethnic backgrounds than the PCP. In the United States, racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately burdened by obesity. Nearly 60% of non-Hispanic black women and 41% of Hispanic women are obese, compared with 33% of non-Hispanic whites [28]. Despite this fact, obese non-Hispanic black and Hispanic patients are more likely than white patients to perceive themselves as “slightly overweight” and to rate their health as good to excellent despite their obesity [29,30]. As a result, they may be less likely to seek out weight loss strategies on their own or ask for weight control advice from their providers [31]. Additionally, racial and ethnic disparities in access to healthy foods [32,33], safe areas for engaging in physical activity [34], and lack of social support for healthy behaviors may make it much more difficult for some minority patients to act on their PCP's advice.

Because of different cultures, social influences, and norms, what an individual patient perceives as obese or unhealthy may differ dramatically from what his or her physician views as obese or unhealthy [35–38]. Therefore, it is important that PCPs have a discussion with their patients about their subjective weight and health perceptions before beginning any prescriptive weight management strategies or discussions of “normal BMI” [39,40]. If an obese patient views herself as being at a normal weight for her culture, she is unlikely to respond well to being told by her doctor that she needs to lose 40 pounds to get to a healthy weight. Recent research suggests that alternative goals, such as encouraging weight maintenance for non-Hispanic black women, may be a successful alternative to the traditional pathway of encouraging weight loss [41].

In addition to understanding cultural context during weight status discussions, it is also important to give behavior change advice that is sensitive to the culture, race, and ethnicity of the patient. Dietary recommendations should take into account the patient’s culture. For example, Lindbergh et al have noted that cooking in traditional Hispanic culture does not rely as much on measurements as does cooking for non-Hispanic whites [42]. Therefore, measurement-based dietary advice (the cornerstone of portion control) may be a more problematic concept for these patients to incorporate into their home cooking styles [42]. Physical activity recommendations should also be given in context of cultural acceptability. A recent study by Hall and others concluded that some African-American women may be reluctant to follow exercise advice for fear that sweating will ruin their hairstyles [43]. Although providers need not be experts on the cultural norms of all of their patients, they should be open to discussing them, and to asking about the patient’s goals, ideal body type, comfort with physical activity, diet advice and other issues that will make individualized counseling much more effective.

PCP Concern: “Weight gain reflects the patient’s lack of will power and laziness”

Bias towards obese patients has been documented among health care providers [44,45]. Studies have shown that some providers have less respect for obese patients [46], perceive obese patients as nonadherent to medications [47], and associate obesity with “laziness,” “stupidity,” and “worthlessness” [48]. Furthermore, obese patients identify physicians as a primary source of stigma [49] and many report stigmatizing experiences during interactions with the healthcare system [44,45]. In one study, a considerable proportion of obese patients reported ever experiencing stigma from a doctor (69%) or a nurse (46%) [49]. As a result of these negative experiences, obese patients have reported avoiding or delaying medical services such as gynecological cancer screening [50]. A recent study by Gudzune et al found that obese patients had significantly greater odds of “doctor shopping,” where individuals saw 5 or more primary care providers in a 2-year period [51]. This doctor shopping behavior may also be motivated by dissatisfaction with care, as focus groups of obese women have reported doctor shopping until they find a health care provider who is comfortable, experienced, and skilled in treating obese patients [50].

Assessing Implicit and Explicit Weight Bias

In addition to explicit negative attitudes, health care providers may also hold implicit biases towards obese patients [52]. A recent study found that over half of medical students held an implicit anti-fat bias [53]. These implicit attitudes may manifest more subtly during patient encounters. PCPs engage in less emotional rapport building during visits with overweight and obese patients as compared to normal weight patients [54], which include behaviors such as expressing empathy, concern, reassurance, and partnership. The lack of rapport building could negatively influence the patient-provider relationship and decrease the effectiveness of weight loss counseling. PCPs may need to consider undergoing self-assessment to determine whether or not they hold negative implicit and/or explicit attitudes towards obese patients. PCPs can complete the Weight Implicit Association Test (IAT) for free online at https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/demo/. To determine whether they hold negative explicit attitudes, PCPs can download and complete assessments offered by the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity (www.yaleruddcenter.org/resources/bias_toolkit/index.html).