User login

Domestic violence in health care is real and underreported

To protect survivors’ identities, some names have been changed or shortened.

Natasha Abadilla, MD, met the man who would become her abuser while working abroad for a public health nonprofit. When he began emotionally and physically abusing her, she did everything she could to hide it.

“My coworkers knew nothing of the abuse. I became an expert in applying makeup to hide the bruises,” recalls Dr. Abadilla, now a second-year resident and pediatric neurologist at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford.

Dr. Abadilla says she strongly identifies as a hard worker and – to this day – hopes her work did not falter despite her partner’s constant drain on her. But the impact of the abuse continued to affect her for years. Like many survivors of domestic violence, she struggled with PTSD and depression.

Health care workers are often the first point of contact for survivors of domestic violence. Experts and advocates continue to push for more training for clinicians to identify and respond to signs among their patients. Often missing from this conversation is the reality that those tasked with screening can also be victims of intimate partner violence themselves.

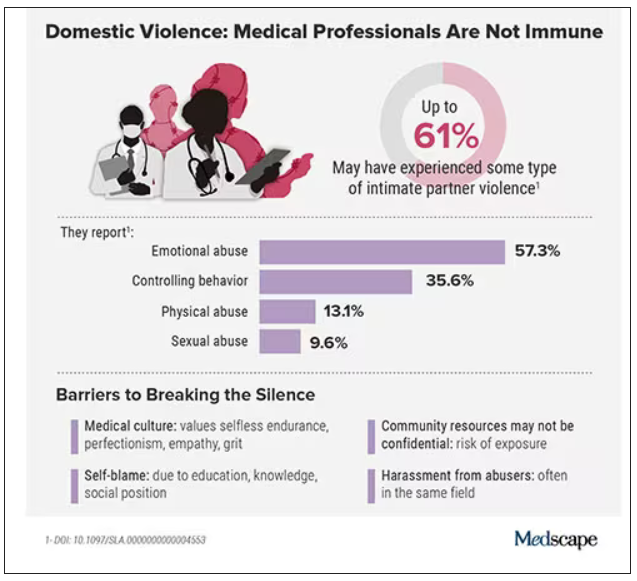

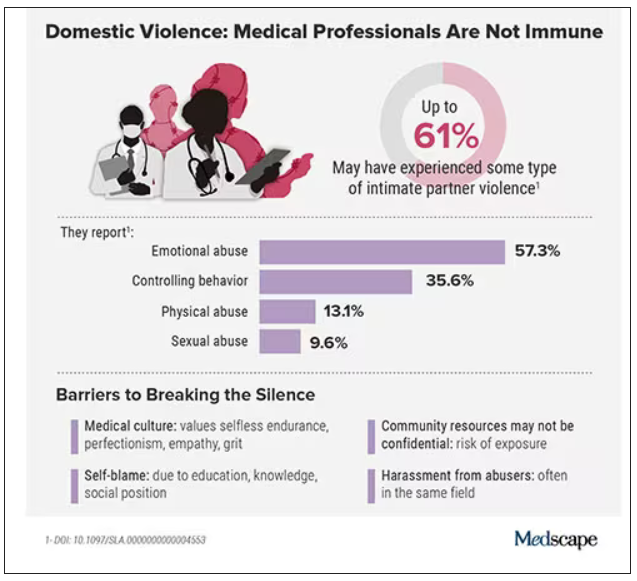

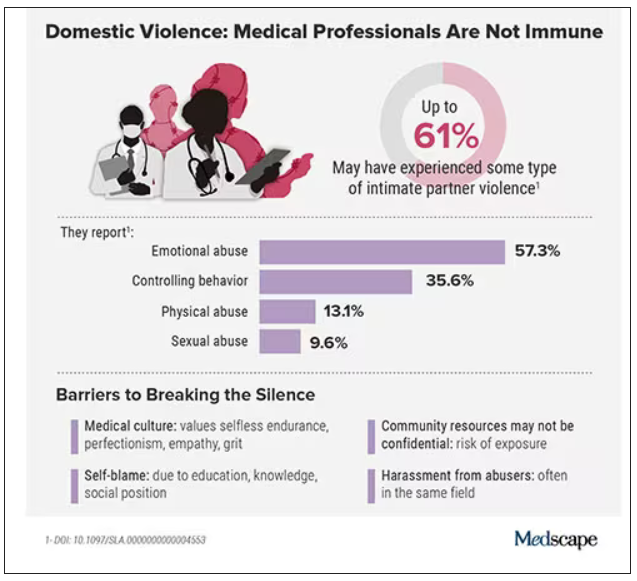

What’s more: The very strengths that medical professionals often pride themselves on – perfectionism, empathy, grit – can make it harder for them to identify abuse in their own relationships and push through humiliation and shame to seek help.

Dr. Abadilla is exceptional among survivors in the medical field. Rather than keep her experience quiet, she has shared it publicly.

Awareness, she believes, can save lives.

An understudied problem in an underserved group

The majority of research on health care workers in this area has focused on workplace violence, which 62% experience worldwide. But intimate partner violence remains understudied and underdiscussed. Some medical professionals are even saddled with a “double burden,” facing trauma at work and at home, note the authors of a 2022 meta-analysis published in the journal Trauma, Violence, & Abuse.

The problem has had dire consequences. In recent years, many health care workers have been killed by their abusers:

- In 2016, Casey M. Drawert, MD, a Texas-based critical care anesthesiologist, was fatally shot by her husband in a murder-suicide.

- In 2018, Tamara O’Neal, MD, an ER physician, and Dayna Less, a first-year pharmacy resident, were killed by Dr. O’Neal’s ex-fiancé at Mercy Hospital in Chicago.

- In 2019, Sarah Hawley, MD, a first-year University of Utah resident, was fatally shot by her boyfriend in a murder-suicide.

- In 2021, Moria Kinsey, a nurse practitioner in Tahlequah, Okla., was murdered by a physician.

- In July of 2023, Gwendolyn Lavonne Riddick, DO, an ob.gyn. in North Carolina, was fatally shot by the father of her 3-year-old son.

There are others.

In the wake of these tragedies, calls for health care workers to screen each other as well as patients have grown. But for an untold number of survivors, breaking the silence is still not possible due to concerns about their reputation, professional consequences, the threat of harassment from abusers who are often in the same field, a medical culture of selfless endurance, and a lack of appropriate resources.

While the vast majority have stayed silent, those who have spoken out say there’s a need for targeted interventions to educate medical professionals as well as more supportive policies throughout the health care system.

Are health care workers more at risk?

Although more studies are needed, research indicates health care workers experience domestic violence at rates comparable to those of other populations, whereas some data suggest rates may be higher.

In the United States, more than one in three women and one in four men experience some form of intimate partner violence in their lifetime. Similarly, a 2020 study found that 24% of 400 physicians responding to a survey reported a history of domestic violence, with 15% reporting verbal abuse, 8% reporting physical violence, 4% reporting sexual abuse, and 4% reporting stalking.

Meanwhile, in an anonymous survey completed by 882 practicing surgeons and trainees in the United States from late 2018 to early 2019, more than 60% reported experiencing some type of intimate partner violence, most commonly emotional abuse.

Recent studies in the United Kingdom, Australia, and elsewhere show that significant numbers of medical professionals are fighting this battle. A 2019 study of more than 2,000 nurses, midwives, and health care assistants in the United Kingdom found that nurses were three times more likely to experience domestic violence than the average person.

What would help solve this problem: More study of health care worker-survivors as a unique group with unique risk factors. In general, domestic violence is most prevalent among women and people in marginalized groups. But young adults, such as medical students and trainees, can face an increased risk due to economic strain. Major life changes, such as relocating for residency, can also drive up stress and fray social connections, further isolating victims.

Why it’s so much harder for medical professionals to reveal abuse

For medical professionals accustomed to being strong and forging on, identifying as a victim of abuse can seem like a personal contradiction. It can feel easier to separate their personal and professional lives rather than face a complex reality.

In a personal essay on KevinMD.com, medical student Chloe N. L. Lee describes this emotional turmoil. “As an aspiring psychiatrist, I questioned my character judgment (how did I end up with a misogynistic abuser?) and wondered if I ought to have known better. I worried that my colleagues would deem me unfit to care for patients. And I thought that this was not supposed to happen to women like me,” Ms. Lee writes.

Kimberly, a licensed therapist, experienced a similar pattern of self-blame when her partner began exhibiting violent behavior. “For a long time, I felt guilty because I said to myself, You’re a therapist. You’re supposed to know this,” she recalls. At the same time, she felt driven to help him and sought couples therapy as his violence escalated.

Whitney, a pharmacist, recognized the “hallmarks” of abuse in her relationship, but she coped by compartmentalizing. Whitney says she was vulnerable to her abuser as a young college student who struggled financially. As he showered her with gifts, she found herself waving away red flags like aggressiveness or overprotectiveness.

After Whitney graduated, her partner’s emotional manipulation escalated into frequent physical assaults. When he gave her a black eye, she could not bring herself to go into work. She quit her job without notice. Despite a spotless record, none of her coworkers ever reached out to investigate her sudden departure.

It would take 8 years for Whitney to acknowledge the abuse and seize a moment to escape. She fled with just her purse and started over in a new city, rebuilding her life in the midst of harassment and threats from her ex. She says she’s grateful to be alive.

An imperfect system doesn’t help

Health care workers rarely ask for support or disclose abuse at work. Some have cited stigma, a lack of confidentiality (especially when the abuser is also in health care), fears about colleagues’ judgment, and a culture that doesn’t prioritize self-care.

Sometimes policies get in the way: In a 2021 qualitative study of interviews with 21 female physician-survivors in the United Kingdom, many said that despite the intense stress of abuse and recovery, they were unable to take any time off.

Of 180 UK-based midwife-survivors interviewed in a 2018 study, only 60 sought support at work and 30 received it. Many said their supervisors pressured them to report the abuse and get back to work, called social services behind their back, or reported them to their professional regulator. “I was treated like the perpetrator,” one said. Barbara Hernandez, PhD, a researcher who studies physician-survivors and director of physician vitality at Loma Linda University in southern California, says workplace violence and mistreatment from patients or colleagues – and a poor institutional response – can make those in health care feel like they have to “shut up and put up,” priming them to also tolerate abuse at home.

When survivors do reach out, there can be a disconnect between the resources they need and those they’re offered, Dr. Hernandez adds. In a recent survey of 400 physicians she conducted, respondents typically said they would advise a physician-survivor to “get to a shelter quickly.” But when roles were reversed, they admitted going to a shelter was the least feasible option. Support groups can also be problematic in smaller communities where physicians might be recognized or see their own patients.

Complicating matters further, the violence often comes from within the medical community. This can lead to particularly malicious abuse tactics like sending false accusations to a victim’s regulatory college or board; prolonged court and custody battles to drain them of all resources and their ability to hold a job; or even sabotage, harassment, or violence at work. The sheen of the abuser’s public persona, on the other hand, can guard them from any accountability.

For example, one physician-survivor said her ex-partner, a psychiatrist, coerced her into believing she was mentally ill, claimed she was “psychotic” in order to take back their children after she left, and had numerous colleagues serve as character witnesses in court for him, “saying he couldn’t have done any of these things, how great he is, and what a wonderful father he is.”

Slow progress is still progress

After Sherilyn M. Gordon-Burroughs, MD, a Texas-based transplant surgeon, mother, and educator, was killed by her husband in a murder-suicide in 2017, her friends Barbara Lee Bass, MD, president of the American College of Surgeons, and Patricia L. Turner, MD, were spurred into action. Together, they founded the ACS Intimate Partner Violence Task Force. Their mission is to educate surgeons to identify the signs of intimate partner violence (IPV) in themselves and their colleagues and connect them with resources.

“There is a concerted effort to close that gap,” says D’Andrea K. Joseph, MD, cochair of the task force and chief of trauma and acute care surgery at NYU Langone in New York. In the future, Dr. Joseph predicts, “making this a part of the curriculum, that it’s standardized for residents and trainees, that there is a safe place for victims ... and that we can band together and really recognize and assist our colleagues who are in trouble.”

Resources created by the ACS IPV task force, such as the toolkit and curriculum, provide a model for other health care leaders. But there have been few similar initiatives aimed at increasing IPV intervention within the medical system.

What you can do in your workplace

In her essay, Ms. Lee explains that a major turning point came when a physician friend explicitly asked if she was experiencing abuse. He then gently confirmed she was, and asked without judgment how he could support her, an approach that mirrors advice from the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

“Having a physician validate that this was, indeed, an abusive situation helped enormously ... I believe it may have saved my life,” she writes.

That validation can be crucial, and Dr. Abadilla urges other physicians to regularly check in with colleagues, especially those who seem particularly positive with a go-getter attitude and yet may not seem themselves. That was how she presented when she was struggling the most.

Supporting systemic changes within your organization and beyond is also important. The authors of the 2022 meta-analysis stress the need for domestic violence training, legislative changes, paid leave, and union support.

Finding strength in recovery

Over a decade after escaping her abuser, Whitney says she’s only just begun to share her experience, but what she’s learned has made her a better pharmacist. She says she’s more attuned to subtle signs something could be off with patients and coworkers. When someone makes comments about feeling anxious or that they can’t do anything right, it’s important to ask why, she says.

Recently, Kimberly has opened up to her mentor and other therapists, many of whom have shared that they’re also survivors.

“The last thing I said to [my abuser] is you think you’ve won and you’re hurting me, but what you’ve done to me – I’m going to utilize this and I’m going to help other people,” Kimberly says. “This pain that I have will go away, and I’m going to save the lives of others.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

To protect survivors’ identities, some names have been changed or shortened.

Natasha Abadilla, MD, met the man who would become her abuser while working abroad for a public health nonprofit. When he began emotionally and physically abusing her, she did everything she could to hide it.

“My coworkers knew nothing of the abuse. I became an expert in applying makeup to hide the bruises,” recalls Dr. Abadilla, now a second-year resident and pediatric neurologist at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford.

Dr. Abadilla says she strongly identifies as a hard worker and – to this day – hopes her work did not falter despite her partner’s constant drain on her. But the impact of the abuse continued to affect her for years. Like many survivors of domestic violence, she struggled with PTSD and depression.

Health care workers are often the first point of contact for survivors of domestic violence. Experts and advocates continue to push for more training for clinicians to identify and respond to signs among their patients. Often missing from this conversation is the reality that those tasked with screening can also be victims of intimate partner violence themselves.

What’s more: The very strengths that medical professionals often pride themselves on – perfectionism, empathy, grit – can make it harder for them to identify abuse in their own relationships and push through humiliation and shame to seek help.

Dr. Abadilla is exceptional among survivors in the medical field. Rather than keep her experience quiet, she has shared it publicly.

Awareness, she believes, can save lives.

An understudied problem in an underserved group

The majority of research on health care workers in this area has focused on workplace violence, which 62% experience worldwide. But intimate partner violence remains understudied and underdiscussed. Some medical professionals are even saddled with a “double burden,” facing trauma at work and at home, note the authors of a 2022 meta-analysis published in the journal Trauma, Violence, & Abuse.

The problem has had dire consequences. In recent years, many health care workers have been killed by their abusers:

- In 2016, Casey M. Drawert, MD, a Texas-based critical care anesthesiologist, was fatally shot by her husband in a murder-suicide.

- In 2018, Tamara O’Neal, MD, an ER physician, and Dayna Less, a first-year pharmacy resident, were killed by Dr. O’Neal’s ex-fiancé at Mercy Hospital in Chicago.

- In 2019, Sarah Hawley, MD, a first-year University of Utah resident, was fatally shot by her boyfriend in a murder-suicide.

- In 2021, Moria Kinsey, a nurse practitioner in Tahlequah, Okla., was murdered by a physician.

- In July of 2023, Gwendolyn Lavonne Riddick, DO, an ob.gyn. in North Carolina, was fatally shot by the father of her 3-year-old son.

There are others.

In the wake of these tragedies, calls for health care workers to screen each other as well as patients have grown. But for an untold number of survivors, breaking the silence is still not possible due to concerns about their reputation, professional consequences, the threat of harassment from abusers who are often in the same field, a medical culture of selfless endurance, and a lack of appropriate resources.

While the vast majority have stayed silent, those who have spoken out say there’s a need for targeted interventions to educate medical professionals as well as more supportive policies throughout the health care system.

Are health care workers more at risk?

Although more studies are needed, research indicates health care workers experience domestic violence at rates comparable to those of other populations, whereas some data suggest rates may be higher.

In the United States, more than one in three women and one in four men experience some form of intimate partner violence in their lifetime. Similarly, a 2020 study found that 24% of 400 physicians responding to a survey reported a history of domestic violence, with 15% reporting verbal abuse, 8% reporting physical violence, 4% reporting sexual abuse, and 4% reporting stalking.

Meanwhile, in an anonymous survey completed by 882 practicing surgeons and trainees in the United States from late 2018 to early 2019, more than 60% reported experiencing some type of intimate partner violence, most commonly emotional abuse.

Recent studies in the United Kingdom, Australia, and elsewhere show that significant numbers of medical professionals are fighting this battle. A 2019 study of more than 2,000 nurses, midwives, and health care assistants in the United Kingdom found that nurses were three times more likely to experience domestic violence than the average person.

What would help solve this problem: More study of health care worker-survivors as a unique group with unique risk factors. In general, domestic violence is most prevalent among women and people in marginalized groups. But young adults, such as medical students and trainees, can face an increased risk due to economic strain. Major life changes, such as relocating for residency, can also drive up stress and fray social connections, further isolating victims.

Why it’s so much harder for medical professionals to reveal abuse

For medical professionals accustomed to being strong and forging on, identifying as a victim of abuse can seem like a personal contradiction. It can feel easier to separate their personal and professional lives rather than face a complex reality.

In a personal essay on KevinMD.com, medical student Chloe N. L. Lee describes this emotional turmoil. “As an aspiring psychiatrist, I questioned my character judgment (how did I end up with a misogynistic abuser?) and wondered if I ought to have known better. I worried that my colleagues would deem me unfit to care for patients. And I thought that this was not supposed to happen to women like me,” Ms. Lee writes.

Kimberly, a licensed therapist, experienced a similar pattern of self-blame when her partner began exhibiting violent behavior. “For a long time, I felt guilty because I said to myself, You’re a therapist. You’re supposed to know this,” she recalls. At the same time, she felt driven to help him and sought couples therapy as his violence escalated.

Whitney, a pharmacist, recognized the “hallmarks” of abuse in her relationship, but she coped by compartmentalizing. Whitney says she was vulnerable to her abuser as a young college student who struggled financially. As he showered her with gifts, she found herself waving away red flags like aggressiveness or overprotectiveness.

After Whitney graduated, her partner’s emotional manipulation escalated into frequent physical assaults. When he gave her a black eye, she could not bring herself to go into work. She quit her job without notice. Despite a spotless record, none of her coworkers ever reached out to investigate her sudden departure.

It would take 8 years for Whitney to acknowledge the abuse and seize a moment to escape. She fled with just her purse and started over in a new city, rebuilding her life in the midst of harassment and threats from her ex. She says she’s grateful to be alive.

An imperfect system doesn’t help

Health care workers rarely ask for support or disclose abuse at work. Some have cited stigma, a lack of confidentiality (especially when the abuser is also in health care), fears about colleagues’ judgment, and a culture that doesn’t prioritize self-care.

Sometimes policies get in the way: In a 2021 qualitative study of interviews with 21 female physician-survivors in the United Kingdom, many said that despite the intense stress of abuse and recovery, they were unable to take any time off.

Of 180 UK-based midwife-survivors interviewed in a 2018 study, only 60 sought support at work and 30 received it. Many said their supervisors pressured them to report the abuse and get back to work, called social services behind their back, or reported them to their professional regulator. “I was treated like the perpetrator,” one said. Barbara Hernandez, PhD, a researcher who studies physician-survivors and director of physician vitality at Loma Linda University in southern California, says workplace violence and mistreatment from patients or colleagues – and a poor institutional response – can make those in health care feel like they have to “shut up and put up,” priming them to also tolerate abuse at home.

When survivors do reach out, there can be a disconnect between the resources they need and those they’re offered, Dr. Hernandez adds. In a recent survey of 400 physicians she conducted, respondents typically said they would advise a physician-survivor to “get to a shelter quickly.” But when roles were reversed, they admitted going to a shelter was the least feasible option. Support groups can also be problematic in smaller communities where physicians might be recognized or see their own patients.

Complicating matters further, the violence often comes from within the medical community. This can lead to particularly malicious abuse tactics like sending false accusations to a victim’s regulatory college or board; prolonged court and custody battles to drain them of all resources and their ability to hold a job; or even sabotage, harassment, or violence at work. The sheen of the abuser’s public persona, on the other hand, can guard them from any accountability.

For example, one physician-survivor said her ex-partner, a psychiatrist, coerced her into believing she was mentally ill, claimed she was “psychotic” in order to take back their children after she left, and had numerous colleagues serve as character witnesses in court for him, “saying he couldn’t have done any of these things, how great he is, and what a wonderful father he is.”

Slow progress is still progress

After Sherilyn M. Gordon-Burroughs, MD, a Texas-based transplant surgeon, mother, and educator, was killed by her husband in a murder-suicide in 2017, her friends Barbara Lee Bass, MD, president of the American College of Surgeons, and Patricia L. Turner, MD, were spurred into action. Together, they founded the ACS Intimate Partner Violence Task Force. Their mission is to educate surgeons to identify the signs of intimate partner violence (IPV) in themselves and their colleagues and connect them with resources.

“There is a concerted effort to close that gap,” says D’Andrea K. Joseph, MD, cochair of the task force and chief of trauma and acute care surgery at NYU Langone in New York. In the future, Dr. Joseph predicts, “making this a part of the curriculum, that it’s standardized for residents and trainees, that there is a safe place for victims ... and that we can band together and really recognize and assist our colleagues who are in trouble.”

Resources created by the ACS IPV task force, such as the toolkit and curriculum, provide a model for other health care leaders. But there have been few similar initiatives aimed at increasing IPV intervention within the medical system.

What you can do in your workplace

In her essay, Ms. Lee explains that a major turning point came when a physician friend explicitly asked if she was experiencing abuse. He then gently confirmed she was, and asked without judgment how he could support her, an approach that mirrors advice from the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

“Having a physician validate that this was, indeed, an abusive situation helped enormously ... I believe it may have saved my life,” she writes.

That validation can be crucial, and Dr. Abadilla urges other physicians to regularly check in with colleagues, especially those who seem particularly positive with a go-getter attitude and yet may not seem themselves. That was how she presented when she was struggling the most.

Supporting systemic changes within your organization and beyond is also important. The authors of the 2022 meta-analysis stress the need for domestic violence training, legislative changes, paid leave, and union support.

Finding strength in recovery

Over a decade after escaping her abuser, Whitney says she’s only just begun to share her experience, but what she’s learned has made her a better pharmacist. She says she’s more attuned to subtle signs something could be off with patients and coworkers. When someone makes comments about feeling anxious or that they can’t do anything right, it’s important to ask why, she says.

Recently, Kimberly has opened up to her mentor and other therapists, many of whom have shared that they’re also survivors.

“The last thing I said to [my abuser] is you think you’ve won and you’re hurting me, but what you’ve done to me – I’m going to utilize this and I’m going to help other people,” Kimberly says. “This pain that I have will go away, and I’m going to save the lives of others.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

To protect survivors’ identities, some names have been changed or shortened.

Natasha Abadilla, MD, met the man who would become her abuser while working abroad for a public health nonprofit. When he began emotionally and physically abusing her, she did everything she could to hide it.

“My coworkers knew nothing of the abuse. I became an expert in applying makeup to hide the bruises,” recalls Dr. Abadilla, now a second-year resident and pediatric neurologist at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford.

Dr. Abadilla says she strongly identifies as a hard worker and – to this day – hopes her work did not falter despite her partner’s constant drain on her. But the impact of the abuse continued to affect her for years. Like many survivors of domestic violence, she struggled with PTSD and depression.

Health care workers are often the first point of contact for survivors of domestic violence. Experts and advocates continue to push for more training for clinicians to identify and respond to signs among their patients. Often missing from this conversation is the reality that those tasked with screening can also be victims of intimate partner violence themselves.

What’s more: The very strengths that medical professionals often pride themselves on – perfectionism, empathy, grit – can make it harder for them to identify abuse in their own relationships and push through humiliation and shame to seek help.

Dr. Abadilla is exceptional among survivors in the medical field. Rather than keep her experience quiet, she has shared it publicly.

Awareness, she believes, can save lives.

An understudied problem in an underserved group

The majority of research on health care workers in this area has focused on workplace violence, which 62% experience worldwide. But intimate partner violence remains understudied and underdiscussed. Some medical professionals are even saddled with a “double burden,” facing trauma at work and at home, note the authors of a 2022 meta-analysis published in the journal Trauma, Violence, & Abuse.

The problem has had dire consequences. In recent years, many health care workers have been killed by their abusers:

- In 2016, Casey M. Drawert, MD, a Texas-based critical care anesthesiologist, was fatally shot by her husband in a murder-suicide.

- In 2018, Tamara O’Neal, MD, an ER physician, and Dayna Less, a first-year pharmacy resident, were killed by Dr. O’Neal’s ex-fiancé at Mercy Hospital in Chicago.

- In 2019, Sarah Hawley, MD, a first-year University of Utah resident, was fatally shot by her boyfriend in a murder-suicide.

- In 2021, Moria Kinsey, a nurse practitioner in Tahlequah, Okla., was murdered by a physician.

- In July of 2023, Gwendolyn Lavonne Riddick, DO, an ob.gyn. in North Carolina, was fatally shot by the father of her 3-year-old son.

There are others.

In the wake of these tragedies, calls for health care workers to screen each other as well as patients have grown. But for an untold number of survivors, breaking the silence is still not possible due to concerns about their reputation, professional consequences, the threat of harassment from abusers who are often in the same field, a medical culture of selfless endurance, and a lack of appropriate resources.

While the vast majority have stayed silent, those who have spoken out say there’s a need for targeted interventions to educate medical professionals as well as more supportive policies throughout the health care system.

Are health care workers more at risk?

Although more studies are needed, research indicates health care workers experience domestic violence at rates comparable to those of other populations, whereas some data suggest rates may be higher.

In the United States, more than one in three women and one in four men experience some form of intimate partner violence in their lifetime. Similarly, a 2020 study found that 24% of 400 physicians responding to a survey reported a history of domestic violence, with 15% reporting verbal abuse, 8% reporting physical violence, 4% reporting sexual abuse, and 4% reporting stalking.

Meanwhile, in an anonymous survey completed by 882 practicing surgeons and trainees in the United States from late 2018 to early 2019, more than 60% reported experiencing some type of intimate partner violence, most commonly emotional abuse.

Recent studies in the United Kingdom, Australia, and elsewhere show that significant numbers of medical professionals are fighting this battle. A 2019 study of more than 2,000 nurses, midwives, and health care assistants in the United Kingdom found that nurses were three times more likely to experience domestic violence than the average person.

What would help solve this problem: More study of health care worker-survivors as a unique group with unique risk factors. In general, domestic violence is most prevalent among women and people in marginalized groups. But young adults, such as medical students and trainees, can face an increased risk due to economic strain. Major life changes, such as relocating for residency, can also drive up stress and fray social connections, further isolating victims.

Why it’s so much harder for medical professionals to reveal abuse

For medical professionals accustomed to being strong and forging on, identifying as a victim of abuse can seem like a personal contradiction. It can feel easier to separate their personal and professional lives rather than face a complex reality.

In a personal essay on KevinMD.com, medical student Chloe N. L. Lee describes this emotional turmoil. “As an aspiring psychiatrist, I questioned my character judgment (how did I end up with a misogynistic abuser?) and wondered if I ought to have known better. I worried that my colleagues would deem me unfit to care for patients. And I thought that this was not supposed to happen to women like me,” Ms. Lee writes.

Kimberly, a licensed therapist, experienced a similar pattern of self-blame when her partner began exhibiting violent behavior. “For a long time, I felt guilty because I said to myself, You’re a therapist. You’re supposed to know this,” she recalls. At the same time, she felt driven to help him and sought couples therapy as his violence escalated.

Whitney, a pharmacist, recognized the “hallmarks” of abuse in her relationship, but she coped by compartmentalizing. Whitney says she was vulnerable to her abuser as a young college student who struggled financially. As he showered her with gifts, she found herself waving away red flags like aggressiveness or overprotectiveness.

After Whitney graduated, her partner’s emotional manipulation escalated into frequent physical assaults. When he gave her a black eye, she could not bring herself to go into work. She quit her job without notice. Despite a spotless record, none of her coworkers ever reached out to investigate her sudden departure.

It would take 8 years for Whitney to acknowledge the abuse and seize a moment to escape. She fled with just her purse and started over in a new city, rebuilding her life in the midst of harassment and threats from her ex. She says she’s grateful to be alive.

An imperfect system doesn’t help

Health care workers rarely ask for support or disclose abuse at work. Some have cited stigma, a lack of confidentiality (especially when the abuser is also in health care), fears about colleagues’ judgment, and a culture that doesn’t prioritize self-care.

Sometimes policies get in the way: In a 2021 qualitative study of interviews with 21 female physician-survivors in the United Kingdom, many said that despite the intense stress of abuse and recovery, they were unable to take any time off.

Of 180 UK-based midwife-survivors interviewed in a 2018 study, only 60 sought support at work and 30 received it. Many said their supervisors pressured them to report the abuse and get back to work, called social services behind their back, or reported them to their professional regulator. “I was treated like the perpetrator,” one said. Barbara Hernandez, PhD, a researcher who studies physician-survivors and director of physician vitality at Loma Linda University in southern California, says workplace violence and mistreatment from patients or colleagues – and a poor institutional response – can make those in health care feel like they have to “shut up and put up,” priming them to also tolerate abuse at home.

When survivors do reach out, there can be a disconnect between the resources they need and those they’re offered, Dr. Hernandez adds. In a recent survey of 400 physicians she conducted, respondents typically said they would advise a physician-survivor to “get to a shelter quickly.” But when roles were reversed, they admitted going to a shelter was the least feasible option. Support groups can also be problematic in smaller communities where physicians might be recognized or see their own patients.

Complicating matters further, the violence often comes from within the medical community. This can lead to particularly malicious abuse tactics like sending false accusations to a victim’s regulatory college or board; prolonged court and custody battles to drain them of all resources and their ability to hold a job; or even sabotage, harassment, or violence at work. The sheen of the abuser’s public persona, on the other hand, can guard them from any accountability.

For example, one physician-survivor said her ex-partner, a psychiatrist, coerced her into believing she was mentally ill, claimed she was “psychotic” in order to take back their children after she left, and had numerous colleagues serve as character witnesses in court for him, “saying he couldn’t have done any of these things, how great he is, and what a wonderful father he is.”

Slow progress is still progress

After Sherilyn M. Gordon-Burroughs, MD, a Texas-based transplant surgeon, mother, and educator, was killed by her husband in a murder-suicide in 2017, her friends Barbara Lee Bass, MD, president of the American College of Surgeons, and Patricia L. Turner, MD, were spurred into action. Together, they founded the ACS Intimate Partner Violence Task Force. Their mission is to educate surgeons to identify the signs of intimate partner violence (IPV) in themselves and their colleagues and connect them with resources.

“There is a concerted effort to close that gap,” says D’Andrea K. Joseph, MD, cochair of the task force and chief of trauma and acute care surgery at NYU Langone in New York. In the future, Dr. Joseph predicts, “making this a part of the curriculum, that it’s standardized for residents and trainees, that there is a safe place for victims ... and that we can band together and really recognize and assist our colleagues who are in trouble.”

Resources created by the ACS IPV task force, such as the toolkit and curriculum, provide a model for other health care leaders. But there have been few similar initiatives aimed at increasing IPV intervention within the medical system.

What you can do in your workplace

In her essay, Ms. Lee explains that a major turning point came when a physician friend explicitly asked if she was experiencing abuse. He then gently confirmed she was, and asked without judgment how he could support her, an approach that mirrors advice from the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

“Having a physician validate that this was, indeed, an abusive situation helped enormously ... I believe it may have saved my life,” she writes.

That validation can be crucial, and Dr. Abadilla urges other physicians to regularly check in with colleagues, especially those who seem particularly positive with a go-getter attitude and yet may not seem themselves. That was how she presented when she was struggling the most.

Supporting systemic changes within your organization and beyond is also important. The authors of the 2022 meta-analysis stress the need for domestic violence training, legislative changes, paid leave, and union support.

Finding strength in recovery

Over a decade after escaping her abuser, Whitney says she’s only just begun to share her experience, but what she’s learned has made her a better pharmacist. She says she’s more attuned to subtle signs something could be off with patients and coworkers. When someone makes comments about feeling anxious or that they can’t do anything right, it’s important to ask why, she says.

Recently, Kimberly has opened up to her mentor and other therapists, many of whom have shared that they’re also survivors.

“The last thing I said to [my abuser] is you think you’ve won and you’re hurting me, but what you’ve done to me – I’m going to utilize this and I’m going to help other people,” Kimberly says. “This pain that I have will go away, and I’m going to save the lives of others.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.