User login

Simultaneous Cases of Carfilzomib-Induced Thrombotic Microangiopathy in 2 Patients With Multiple Myeloma

As a class of drugs, proteasome inhibitors are known to rarely cause drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy (DITMA). In particular, carfilzomib is a second-generation, irreversible proteasome inhibitor approved for the treatment of relapsed, refractory multiple myeloma (MM) in combination with other therapeutic agents.1 Although generally well tolerated, carfilzomib has been associated with serious adverse events such as cardiovascular toxicity and DITMA.2-4 Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is a life-threatening disorder characterized by thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and end-organ damage.5 Its occurrence secondary to carfilzomib has been reported only rarely in clinical trials of MM, and the most effective management of the disorder as well as the concurrent risk factors that contribute to its development remain incompletely understood.6,7 As a result, given both the expanding use of carfilzomib in practice and the morbidity of TMA, descriptions of carfilzomib-induced TMA from the real-world setting continue to provide important contributions to our understanding of the disorder.

At our US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center, 2 patients developed severe carfilzomib-induced TMA within days of one another. The presentation of simultaneous cases was highly unexpected and offered the unique opportunity to compare clinical features in real time. Here, we describe our 2 cases in detail, review their presentations and management in the context of the prior literature, and discuss potential insights gained into the disease.

Case Presentation

Case 1

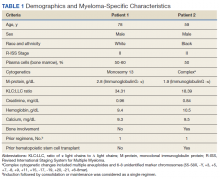

A 78-year-old male patient was diagnosed with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance in 2012 that progressed to Revised International Staging System stage II IgG-κ MM in 2016 due to worsening anemia with a hemoglobin level < 10 g/dL (Table 1). He was treated initially with 8 cycles of first-line bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone, to which he achieved a partial response with > 50% reduction in serum M-protein. He then received 3 cycles of maintenance bortezomib until relapse, at which time he was switched to second-line therapy consisting of carfilzomib 20 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 and 56 mg/m2 on days 8, 9, 15, and 16 for cycle 1, followed by 56 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 for subsequent cycles plus dexamethasone 20 mg twice weekly every 28 days.

After the patient received cycle 3, day 1 of carfilzomib, he developed subjective fevers, chills, and diarrhea. He missed his day 2 infusion and instead presented to the VA emergency department, where his vital signs were stable and laboratory tests were notable for the following levels: leukocytosis of20.3 K/µL (91.7% neutrophils), hemoglobin 12.4 g/dL (prior 13.5 g/dL), platelet count 171 K/µL, and creatinine 1.39 mg/dL (prior 1.13 g/dL). A chest X-ray demonstrated diffuse bilateral opacities concerning for edema vs infection, and he was started empirically on vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and azithromycin. His outpatient medications, which included acyclovir, aspirin, finasteride, oxybutynin, ranitidine, omega-3 fatty acids, fish oil, vitamin D, and senna, were continued as indicated.

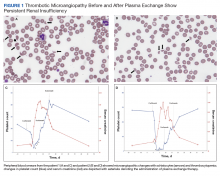

On hospital day 2, the patient’s platelet count dropped to 81 K/µL and creatinine level rose to 1.78 mg/dL. He developed dark urine (urinalysis [UA] 3+ blood, 6-11 red blood cells per high power field [RBC/HPF]) and had laboratory tests suggestive of hemolysis, including lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) > 1,200 IU/L (reference range, 60-250 IU/L), haptoglobin < 30 mg/dL (reference range, 44-215 mg/dL), total bilirubin 3.2 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1.3 mg/dL; indirect bilirubin, 2.6 mg/dL), and a peripheral blood smear demonstrating moderate microangiopathy (Figure 1).

Workup for alternative causes of thrombocytopenia included a negative heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel and a disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) panel showing elevated fibrinogen (515 mg/dL; reference range, 200-400 mg/dL) and mildly elevated international normalized ratio (INR) (1.3). Blood cultures were negative, and a 22-pathogen gastrointestinal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel failed to identify viral or bacterial pathogens, including Escherichia coli O157:H7. C3 (81 mg/dL; reference range, 90-180 mg/dL) and C4 (16 mg/dL; reference range, 16-47 mg/dL) complement levels were borderline to mildly reduced.

Based on this constellation of findings, a diagnosis of TMA was made, and the patient was started empirically on plasma exchange and pulse-dosed steroids. After 4 cycles of plasma exchange, the platelet count had normalized from its nadir of 29 K/µL. ADAMTS13 activity (98% enzyme activity) ruled out thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), and the patient continued to have anuric renal failure (creatinine, 8.62 mg/dL) necessitating the initiation of hemodialysis. Given persistent renal insufficiency, a diagnosis of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) was considered, and eculizumab 900 mg was administered on days 8 and 15 with stabilization of renal function. By the time of discharge on day 18, the patient’s creatinine level had decreased to 3.89 mg/dL, and platelet count was 403 K/µL. Creatinine normalized to 1.07 mg/dL by day 46.

Outpatient genetic testing through the BloodCenter of Wisconsin Diagnostic Laboratories was negative for mutations in the following genes associated with atypical HUS: CFH, CFI, MCP (CD46), THBD, CFB, C3, DGKE, ADAMTS13, C4BPA, C4BPB, LMNA, CFHR1, CFHR3, CFHR4, and CFHR5. The patient subsequently remained off all antimyeloma therapy for > 1 year until eventually starting third-line pomalidomide plus dexamethasone without reinitiation of proteasome inhibitor therapy.

Case 2

A 59-year-old male patient, diagnosed in 2013 with ISS stage I IgG-κ MM after presenting with compression fractures, completed 8 cycles of cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone before undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with complete response (Table 1). He subsequently received single-agent maintenance bortezomib until relapse nearly 2 years later, at which time he started second-line carfilzomib 20 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 and 27 mg/m2 on days 8, 9, 15, and 16 for cycle 1, followed by 27 mg/m2 on days 8, 9, 15, and 16 for cycles 2 to 8, lenalidomide 25 mg on days 1 to 21, and dexamethasone 40 mg weekly every 28 days. Serum free light chain levels normalized after 9 cycles, and he subsequently began maintenance carfilzomib 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 15 plus lenalidomide 10 mg on days 1 to 21 every 28 days.

On the morning before admission, the patient received C6D17 of maintenance carfilzomib, which had been delayed from day 15 because of the holiday. Later that evening, he developed nausea, vomiting, and fever of 101.3 °F. He presented to the VA emergency department and was tachycardic (108 beats per minute) and hypotensive (86/55 mm Hg). Laboratory tests were notable for hemoglobin level 9.9 g/dL (prior 11.6 g/dL), platelet count 270 K/µL, and creatinine level 1.86 mg/dL (prior 1.12 mg/dL). A respiratory viral panel was positive for influenza A, and antimicrobial agents were eventually broadened to piperacillin-tazobactam, azithromycin, and oseltamivir. His outpatient medications, which included acyclovir, zoledronic acid, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, aspirin, amlodipine, atorvastatin, omeprazole, zolpidem, calcium, vitamin D, loratadine, ascorbic acid, and prochlorperazine, were continued as indicated.

On hospital day 2, the patient’s platelet count declined from 211 to 57 K/µL. He developed tea-colored urine (UA 2+ blood, 0-2 RBC/HPF) and had laboratory tests suggestive of hemolysis, including LDH 910 IU/L (reference range, 60-250 IU/L), total bilirubin 3.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1.3 mg/dL; no direct or indirect available), and a peripheral blood smear demonstrating moderate microangiopathy. Although haptoglobin level was normal at this time (206 mg/dL; reference range, 44-215 mg/dL), it decreased to 42 mg/dL by the following day. Additional workup included a negative direct Coombs and a DIC panel showing elevated fibrinogen (596 mg/dL; reference range, 200-400 mg/dL) and mildly elevated INR (1.16). Blood cultures remained negative, and a 22-pathogen GI PCR panel identified no viral or bacterial pathogens, including E coli O157:H7. C3 (114 mg/dL; reference range, 90-180 mg/dL) and C4 (40 mg/dL; reference range, 16-47 mg/dL) complement levels were both normal.

Based on these findings, empiric treatment was started with plasma exchange and pulse-dosed steroids. The patient received 3 cycles of plasma exchange until the results of the ADAMTS13 activity ruled out TTP (63% enzyme activity). Over the next 6 days, his platelet count reached a nadir of 6 K/µL and creatinine level peaked at 10.36 mg/dL, necessitating the initiation of hemodialysis. Given severe renal insufficiency, a diagnosis of atypical HUS was again considered, and eculizumab 900 mg was administered on days 9 and 16 with stabilization of renal function. By the time of discharge on day 17, the patient’s creatinine level had decreased to 4.17 mg/dL and platelet count was 164 K/µL. Creatinine level normalized to 1.02 mg/dL by day 72.

Outpatient genetic testing through the BloodCenter of Wisconsin Diagnostic Laboratories was negative for gene mutations associated with atypical HUS. Approximately 1 month after discharge, the patient resumed maintenance lenalidomide alone without reinitiation of proteasome inhibitor therapy.

Discussion

In this case series, we describe the uncommon drug-related adverse event of TMA occurring in 2 patients with MM after receiving carfilzomib. Although the incidence of TMA disorders is low, reaching up to 2.8% in patients receiving carfilzomib plus cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone in the phase 2 CARDAMON trial, our experience suggests that a high index of suspicion for carfilzomib-induced TMA is warranted in the real-world setting.8 TMA syndromes, including TTP, HUS, and DITMA, are characterized by microvascular endothelial injury and thrombosis leading to thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.5,9 Several drug culprits of DITMA are recognized, including quinine, gemcitabine, tacrolimus, and proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib, carfilzomib, ixazomib).10-12 In a real-world series of patients receiving proteasome inhibitor therapy, either carfilzomib (n=8) or bortezomib (n=3), common clinical features of DITMA included thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, gastrointestinal symptoms, and renal insufficiency with or without a need for hemodialysis.2 Although DITMA has been described primarily as an early event, its occurrence after 12 months of proteasome inhibitor therapy has also been reported, both in this series and elsewhere, thereby suggesting an ongoing risk for DITMA throughout the duration of carfilzomib treatment.2,13

The diagnosis of DITMA can be challenging given its nonspecific symptoms that overlap with other TMA syndromes. Previous studies have proposed that for a drug to be associated with DITMA, there should be: (1) evidence of clinical and/or pathologic findings of TMA; (2) exclusion of alternative causes of TMA; (3) no other new drug exposures other than the suspected culprit medication; and (4) a lack of recurrence of TMA in absence of the drug.10 In the case of patients with MM, other causes of TMA have also been described, including the underlying plasma cell disorder itself and stem cell transplantation.14 In the 2 cases we have described, these alternative causes were considered unlikely given that only 1 patient underwent transplantation remotely and neither had a previous history of TMA secondary to their disease. With respect to other TMA syndromes, ADAMTS13 levels > 10% and negative stool studies for E coli O157:H7 suggested against TTP or typical HUS, respectively. No other drug culprits were identified, and the close timing between the receipt of carfilzomib and symptom onset supported a causal relationship.

Because specific therapies are lacking, management of DITMA has traditionally included drug discontinuation and supportive care for end-organ injury.5 The terminal complement inhibitor, eculizumab, improves hematologic abnormalities and renal function in patients with atypical HUS but its use for treating patients with DITMA is not standard.15 Therefore, the decision to administer eculizumab to our 2 patients was driven by their severe renal insufficiency without improvement after plasma exchange, which suggested a phenotype similar to atypical HUS. After administration of eculizumab, renal function stabilized and then gradually improved over weeks to months, a time course similar to that described in cases of patients with DITMA secondary to other anticancer therapies treated with eculizumab.16 Although these results suggest a potential role for eculizumab in proteasome inhibitor–induced TMA, distinguishing the benefit of eculizumab over drug discontinuation alone remains challenging, and well-designed prospective investigations are needed.

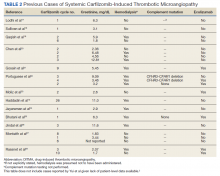

The clustered occurrence of our 2 cases is unique from previous reports that describe carfilzomib-induced TMA as a sporadic event (Table 2).13,17-28 Both immune-mediated and direct toxic effects have been proposed as mechanisms of DITMA, and while our cases do not differentiate between these mechanisms, we considered whether a combined model of initiation, whereby patient or environmental risk factors modulate occurrence of the disease in conjunction with the inciting drug, could explain the clustered occurrence of cases. In this series, drug manufacturing was not a shared risk factor as each patient received carfilzomib from different lot numbers. Furthermore, other patients at our center received carfilzomib from the same batches without developing DITMA. We also considered the role of infection given that 1 patient was diagnosed with influenza A and both presented with nonspecific, viral-like symptoms during the winter season. Interestingly, concurrent viral infections have been reported in other cases of carfilzomib-induced DITMA as well and have also been discussed as a trigger of atypical HUS.20,29 Finally, genetic testing was negative for complement pathway mutations that might predispose to complement dysregulation.

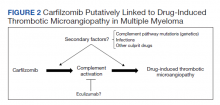

The absence of complement mutations in our 2 patients differs from a recent series describing heterozygous CFHR3-CHFR1 deletions in association with carfilzomib-induced TMA.22 In that report, the authors hypothesized that carfilzomib decreases expression of complement factor H (CFH), a negative regulator of complement activation, thereby leading to complement dysregulation in patients who are genetically predisposed. In a second series, plasma from patients with DITMA secondary to carfilzomib induced the deposition of the complement complex, C5b-9, on endothelial cells in culture, suggesting activation of the complement pathway.30 The effective use of eculizumab would also point to a role for complement activation, and ongoing investigations should aim to identify the triggers and mechanisms of complement dysregulation in this setting, especially for patients like ours in whom genetic testing for complement pathway mutations is negative (Figure 2).

Conclusions

DITMA is a known risk of proteasome inhibitors and is listed as a safety warning in the prescribing information for bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib.12 Given the overall rarity of this adverse event, the simultaneous presentation of our 2 cases was unexpected and underscores the need for heightened awareness in clinical practice. In addition, while no underlying complement mutations were identified, eculizumab was used in both cases to successfully stabilize renal function. Further research investigating the efficacy of eculizumab and the role of complement activation in proteasome inhibitor–induced TMA will be valuable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients whose histories are reported in this manuscript as well as the physicians and staff who provided care during the hospitalizations and beyond. We also thank Oscar Silva, MD, PhD, for his assistance in reviewing and formatting the peripheral blood smear images.

1. McBride A, Klaus JO, Stockeri-Goldstein K. Carfilzomib: a second-generation proteasome inhibitor for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(5):353-360. doi:10.2146/ajhp130281

2. Yui JC, Van Keer J, Weiss BM, et al. Proteasome inhibitor associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(9):E348-E352. doi:10.1002/ajh.24447

3. Dimopoulos MA, Roussou M, Gavriatopoulou M, et al. Cardiac and renal complications of carfilzomib in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2017;1(7):449-454. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2016003269

4. Chari A, Stewart AK, Russell SD, et al. Analysis of carfilzomib cardiovascular safety profile across relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma clinical trials. Blood Adv. 2018;2(13):1633-1644. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2017015545

5. George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):654-666. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1312353

6. Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Palumbo A, et al. Carfilzomib and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (ENDEAVOR): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(1):27-38. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00464-7

7. Dimopoulos M, Quach H, Mateos MV, et al. Carfilzomib, dexamethasone, and daratumumab versus carfilzomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CANDOR): results from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2020;396(10245):186-197. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30734-0

8. Camilleri M, Cuadrado M, Phillips E, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy in untreated myeloma patients receiving carfilzomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone on the CARDAMON study. Br J Haematol. 2021;193(4):750-760. doi:10.1111/bjh.17377

9. Masias C, Vasu S, Cataland SR. None of the above: thrombotic microangiopathy beyond TTP and HUS. Blood. 2017;129(21):2857-2863. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-11-743104

10. Al-Nouri ZL, Reese JA, Terrell DR, Vesely SK, George JN. Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: a systemic review of published reports. Blood. 2015;125(4):616-618. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-11-611335

11. Saleem R, Reese JA, George JN. Drug-induced thrombotic-microangiopathy: an updated systematic review, 2014-2018. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(9):E241-E243. doi:10.1002/ajh.25208

12 Nguyen MN, Nayernama A, Jones SC, Kanapuru B, Gormley N, Waldron PE. Proteasome inhibitor-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: a review of cases reported to the FDA adverse event reporting system and published in the literature. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(9):E218-E222. doi:10.1002/ajh.25832

13. Haddadin M, Al-Sadawi M, Madanat S, et al. Late presentation of carfilzomib associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Am J Med Case Rep. 2019;7(10):240-243. doi:10.12691/ajmcr-7-10-5

14 Portuguese AJ, Gleber C, Passero Jr FC, Lipe B. A review of thrombotic microangiopathies in multiple myeloma. Leuk Res. 2019;85:106195. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2019.106195

15. Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, et al. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2169-2181. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208981

16. Olson SR, Lu E, Sulpizio E, Shatzel JJ, Rueda JF, DeLoughery TG. When to stop eculizumab in complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathies. Am J Nephrol. 2018;48(2):96-107. doi:10.1159/000492033

17. Lodhi A, Kumar A, Saqlain MU, Suneja M. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with proteasome inhibitors. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(5):632-636. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfv059

18. Sullivan MR, Danilov AV, Lansigan F, Dunbar NM. Carfilzomib associated thrombotic microangiopathy initially treated with therapeutic plasma exchange. J Clin Apher., 2015;30(5):308-310. doi:10.1002/jca.21371

19. Qaqish I, Schlam IM, Chakkera HA, Fonseca R, Adamski J. Carfilzomib: a cause of drug associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Transfus Apher Sci. 2016;54(3):401-404. doi:10.1016/j.transci.2016.03.002

20. Chen Y, Ooi M, Lim SF, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy during carfilzomib use: case series in Singapore. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6(7):e450. doi:10.1038/bcj.2016.62

21. Gosain R, Gill A, Fuqua J, et al. Gemcitabine and carfilzomib induced thrombotic microangiopathy: eculizumab as a life-saving treatment. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(12):1926-1930. doi:10.1002/ccr3.1214

22. Portuguese AJ, Lipe B. Carfilzomib-induced aHUS responds to early eculizumab and may be associated with heterozygrous CFHR3-CFHR1 deletion. Blood Adv. 2018;2(23):3443-3446. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018027532

23. Moliz C, Gutiérrez E, Cavero T, Redondo B, Praga M. Eculizumab as a treatment for atypical hemolytic syndrome secondary to carfilzomib. Nefrologia (Engl Ed). 2019;39(1):86-88. doi:10.1016/j.nefro.2018.02.005

24. Jeyaraman P, Borah P, Singh A, et al., Thrombotic microangiopathy after carfilzomib in a very young myeloma patient. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2020;81:102400. doi:10.1016/j.bcmd.2019.102400

25. Bhutani D, Assal A, Mapara MY, Prinzing S, Lentzsch S. Case report: carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy with complement activation treated successfully with eculizumab. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(4):e155-e157. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2020.01.016

26. Jindal N, Jandial A, Jain A, et al. Carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: a case based review. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2020;S1658-3876(20)30118-7. doi:10.1016/j.hemonc.2020.07.001

27. Monteith BE, Venner CP, Reece DE, et al. Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy with concurrent proteasome inhibitor use in the treatment of multiple myeloma: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(11):e791-e780. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2020.04.014

28. Rassner M, Baur R, Wäsch R, et al. Two cases of carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy successfully treated with eculizumab in multiple myeloma. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12882-020-02226-5

29. Kavanagh D, Goodship THJ. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, genetic basis, and clinical manifestations. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:15-20. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.15

30. Blasco M, Martínez-Roca A, Rodríguez-Lobato LG, et al. Complement as the enabler of carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy. Br J Haematol. 2021;193(1):181-187. doi:10.1111/bjh.16796

As a class of drugs, proteasome inhibitors are known to rarely cause drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy (DITMA). In particular, carfilzomib is a second-generation, irreversible proteasome inhibitor approved for the treatment of relapsed, refractory multiple myeloma (MM) in combination with other therapeutic agents.1 Although generally well tolerated, carfilzomib has been associated with serious adverse events such as cardiovascular toxicity and DITMA.2-4 Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is a life-threatening disorder characterized by thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and end-organ damage.5 Its occurrence secondary to carfilzomib has been reported only rarely in clinical trials of MM, and the most effective management of the disorder as well as the concurrent risk factors that contribute to its development remain incompletely understood.6,7 As a result, given both the expanding use of carfilzomib in practice and the morbidity of TMA, descriptions of carfilzomib-induced TMA from the real-world setting continue to provide important contributions to our understanding of the disorder.

At our US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center, 2 patients developed severe carfilzomib-induced TMA within days of one another. The presentation of simultaneous cases was highly unexpected and offered the unique opportunity to compare clinical features in real time. Here, we describe our 2 cases in detail, review their presentations and management in the context of the prior literature, and discuss potential insights gained into the disease.

Case Presentation

Case 1

A 78-year-old male patient was diagnosed with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance in 2012 that progressed to Revised International Staging System stage II IgG-κ MM in 2016 due to worsening anemia with a hemoglobin level < 10 g/dL (Table 1). He was treated initially with 8 cycles of first-line bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone, to which he achieved a partial response with > 50% reduction in serum M-protein. He then received 3 cycles of maintenance bortezomib until relapse, at which time he was switched to second-line therapy consisting of carfilzomib 20 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 and 56 mg/m2 on days 8, 9, 15, and 16 for cycle 1, followed by 56 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 for subsequent cycles plus dexamethasone 20 mg twice weekly every 28 days.

After the patient received cycle 3, day 1 of carfilzomib, he developed subjective fevers, chills, and diarrhea. He missed his day 2 infusion and instead presented to the VA emergency department, where his vital signs were stable and laboratory tests were notable for the following levels: leukocytosis of20.3 K/µL (91.7% neutrophils), hemoglobin 12.4 g/dL (prior 13.5 g/dL), platelet count 171 K/µL, and creatinine 1.39 mg/dL (prior 1.13 g/dL). A chest X-ray demonstrated diffuse bilateral opacities concerning for edema vs infection, and he was started empirically on vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and azithromycin. His outpatient medications, which included acyclovir, aspirin, finasteride, oxybutynin, ranitidine, omega-3 fatty acids, fish oil, vitamin D, and senna, were continued as indicated.

On hospital day 2, the patient’s platelet count dropped to 81 K/µL and creatinine level rose to 1.78 mg/dL. He developed dark urine (urinalysis [UA] 3+ blood, 6-11 red blood cells per high power field [RBC/HPF]) and had laboratory tests suggestive of hemolysis, including lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) > 1,200 IU/L (reference range, 60-250 IU/L), haptoglobin < 30 mg/dL (reference range, 44-215 mg/dL), total bilirubin 3.2 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1.3 mg/dL; indirect bilirubin, 2.6 mg/dL), and a peripheral blood smear demonstrating moderate microangiopathy (Figure 1).

Workup for alternative causes of thrombocytopenia included a negative heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel and a disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) panel showing elevated fibrinogen (515 mg/dL; reference range, 200-400 mg/dL) and mildly elevated international normalized ratio (INR) (1.3). Blood cultures were negative, and a 22-pathogen gastrointestinal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel failed to identify viral or bacterial pathogens, including Escherichia coli O157:H7. C3 (81 mg/dL; reference range, 90-180 mg/dL) and C4 (16 mg/dL; reference range, 16-47 mg/dL) complement levels were borderline to mildly reduced.

Based on this constellation of findings, a diagnosis of TMA was made, and the patient was started empirically on plasma exchange and pulse-dosed steroids. After 4 cycles of plasma exchange, the platelet count had normalized from its nadir of 29 K/µL. ADAMTS13 activity (98% enzyme activity) ruled out thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), and the patient continued to have anuric renal failure (creatinine, 8.62 mg/dL) necessitating the initiation of hemodialysis. Given persistent renal insufficiency, a diagnosis of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) was considered, and eculizumab 900 mg was administered on days 8 and 15 with stabilization of renal function. By the time of discharge on day 18, the patient’s creatinine level had decreased to 3.89 mg/dL, and platelet count was 403 K/µL. Creatinine normalized to 1.07 mg/dL by day 46.

Outpatient genetic testing through the BloodCenter of Wisconsin Diagnostic Laboratories was negative for mutations in the following genes associated with atypical HUS: CFH, CFI, MCP (CD46), THBD, CFB, C3, DGKE, ADAMTS13, C4BPA, C4BPB, LMNA, CFHR1, CFHR3, CFHR4, and CFHR5. The patient subsequently remained off all antimyeloma therapy for > 1 year until eventually starting third-line pomalidomide plus dexamethasone without reinitiation of proteasome inhibitor therapy.

Case 2

A 59-year-old male patient, diagnosed in 2013 with ISS stage I IgG-κ MM after presenting with compression fractures, completed 8 cycles of cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone before undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with complete response (Table 1). He subsequently received single-agent maintenance bortezomib until relapse nearly 2 years later, at which time he started second-line carfilzomib 20 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 and 27 mg/m2 on days 8, 9, 15, and 16 for cycle 1, followed by 27 mg/m2 on days 8, 9, 15, and 16 for cycles 2 to 8, lenalidomide 25 mg on days 1 to 21, and dexamethasone 40 mg weekly every 28 days. Serum free light chain levels normalized after 9 cycles, and he subsequently began maintenance carfilzomib 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 15 plus lenalidomide 10 mg on days 1 to 21 every 28 days.

On the morning before admission, the patient received C6D17 of maintenance carfilzomib, which had been delayed from day 15 because of the holiday. Later that evening, he developed nausea, vomiting, and fever of 101.3 °F. He presented to the VA emergency department and was tachycardic (108 beats per minute) and hypotensive (86/55 mm Hg). Laboratory tests were notable for hemoglobin level 9.9 g/dL (prior 11.6 g/dL), platelet count 270 K/µL, and creatinine level 1.86 mg/dL (prior 1.12 mg/dL). A respiratory viral panel was positive for influenza A, and antimicrobial agents were eventually broadened to piperacillin-tazobactam, azithromycin, and oseltamivir. His outpatient medications, which included acyclovir, zoledronic acid, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, aspirin, amlodipine, atorvastatin, omeprazole, zolpidem, calcium, vitamin D, loratadine, ascorbic acid, and prochlorperazine, were continued as indicated.

On hospital day 2, the patient’s platelet count declined from 211 to 57 K/µL. He developed tea-colored urine (UA 2+ blood, 0-2 RBC/HPF) and had laboratory tests suggestive of hemolysis, including LDH 910 IU/L (reference range, 60-250 IU/L), total bilirubin 3.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1.3 mg/dL; no direct or indirect available), and a peripheral blood smear demonstrating moderate microangiopathy. Although haptoglobin level was normal at this time (206 mg/dL; reference range, 44-215 mg/dL), it decreased to 42 mg/dL by the following day. Additional workup included a negative direct Coombs and a DIC panel showing elevated fibrinogen (596 mg/dL; reference range, 200-400 mg/dL) and mildly elevated INR (1.16). Blood cultures remained negative, and a 22-pathogen GI PCR panel identified no viral or bacterial pathogens, including E coli O157:H7. C3 (114 mg/dL; reference range, 90-180 mg/dL) and C4 (40 mg/dL; reference range, 16-47 mg/dL) complement levels were both normal.

Based on these findings, empiric treatment was started with plasma exchange and pulse-dosed steroids. The patient received 3 cycles of plasma exchange until the results of the ADAMTS13 activity ruled out TTP (63% enzyme activity). Over the next 6 days, his platelet count reached a nadir of 6 K/µL and creatinine level peaked at 10.36 mg/dL, necessitating the initiation of hemodialysis. Given severe renal insufficiency, a diagnosis of atypical HUS was again considered, and eculizumab 900 mg was administered on days 9 and 16 with stabilization of renal function. By the time of discharge on day 17, the patient’s creatinine level had decreased to 4.17 mg/dL and platelet count was 164 K/µL. Creatinine level normalized to 1.02 mg/dL by day 72.

Outpatient genetic testing through the BloodCenter of Wisconsin Diagnostic Laboratories was negative for gene mutations associated with atypical HUS. Approximately 1 month after discharge, the patient resumed maintenance lenalidomide alone without reinitiation of proteasome inhibitor therapy.

Discussion

In this case series, we describe the uncommon drug-related adverse event of TMA occurring in 2 patients with MM after receiving carfilzomib. Although the incidence of TMA disorders is low, reaching up to 2.8% in patients receiving carfilzomib plus cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone in the phase 2 CARDAMON trial, our experience suggests that a high index of suspicion for carfilzomib-induced TMA is warranted in the real-world setting.8 TMA syndromes, including TTP, HUS, and DITMA, are characterized by microvascular endothelial injury and thrombosis leading to thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.5,9 Several drug culprits of DITMA are recognized, including quinine, gemcitabine, tacrolimus, and proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib, carfilzomib, ixazomib).10-12 In a real-world series of patients receiving proteasome inhibitor therapy, either carfilzomib (n=8) or bortezomib (n=3), common clinical features of DITMA included thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, gastrointestinal symptoms, and renal insufficiency with or without a need for hemodialysis.2 Although DITMA has been described primarily as an early event, its occurrence after 12 months of proteasome inhibitor therapy has also been reported, both in this series and elsewhere, thereby suggesting an ongoing risk for DITMA throughout the duration of carfilzomib treatment.2,13

The diagnosis of DITMA can be challenging given its nonspecific symptoms that overlap with other TMA syndromes. Previous studies have proposed that for a drug to be associated with DITMA, there should be: (1) evidence of clinical and/or pathologic findings of TMA; (2) exclusion of alternative causes of TMA; (3) no other new drug exposures other than the suspected culprit medication; and (4) a lack of recurrence of TMA in absence of the drug.10 In the case of patients with MM, other causes of TMA have also been described, including the underlying plasma cell disorder itself and stem cell transplantation.14 In the 2 cases we have described, these alternative causes were considered unlikely given that only 1 patient underwent transplantation remotely and neither had a previous history of TMA secondary to their disease. With respect to other TMA syndromes, ADAMTS13 levels > 10% and negative stool studies for E coli O157:H7 suggested against TTP or typical HUS, respectively. No other drug culprits were identified, and the close timing between the receipt of carfilzomib and symptom onset supported a causal relationship.

Because specific therapies are lacking, management of DITMA has traditionally included drug discontinuation and supportive care for end-organ injury.5 The terminal complement inhibitor, eculizumab, improves hematologic abnormalities and renal function in patients with atypical HUS but its use for treating patients with DITMA is not standard.15 Therefore, the decision to administer eculizumab to our 2 patients was driven by their severe renal insufficiency without improvement after plasma exchange, which suggested a phenotype similar to atypical HUS. After administration of eculizumab, renal function stabilized and then gradually improved over weeks to months, a time course similar to that described in cases of patients with DITMA secondary to other anticancer therapies treated with eculizumab.16 Although these results suggest a potential role for eculizumab in proteasome inhibitor–induced TMA, distinguishing the benefit of eculizumab over drug discontinuation alone remains challenging, and well-designed prospective investigations are needed.

The clustered occurrence of our 2 cases is unique from previous reports that describe carfilzomib-induced TMA as a sporadic event (Table 2).13,17-28 Both immune-mediated and direct toxic effects have been proposed as mechanisms of DITMA, and while our cases do not differentiate between these mechanisms, we considered whether a combined model of initiation, whereby patient or environmental risk factors modulate occurrence of the disease in conjunction with the inciting drug, could explain the clustered occurrence of cases. In this series, drug manufacturing was not a shared risk factor as each patient received carfilzomib from different lot numbers. Furthermore, other patients at our center received carfilzomib from the same batches without developing DITMA. We also considered the role of infection given that 1 patient was diagnosed with influenza A and both presented with nonspecific, viral-like symptoms during the winter season. Interestingly, concurrent viral infections have been reported in other cases of carfilzomib-induced DITMA as well and have also been discussed as a trigger of atypical HUS.20,29 Finally, genetic testing was negative for complement pathway mutations that might predispose to complement dysregulation.

The absence of complement mutations in our 2 patients differs from a recent series describing heterozygous CFHR3-CHFR1 deletions in association with carfilzomib-induced TMA.22 In that report, the authors hypothesized that carfilzomib decreases expression of complement factor H (CFH), a negative regulator of complement activation, thereby leading to complement dysregulation in patients who are genetically predisposed. In a second series, plasma from patients with DITMA secondary to carfilzomib induced the deposition of the complement complex, C5b-9, on endothelial cells in culture, suggesting activation of the complement pathway.30 The effective use of eculizumab would also point to a role for complement activation, and ongoing investigations should aim to identify the triggers and mechanisms of complement dysregulation in this setting, especially for patients like ours in whom genetic testing for complement pathway mutations is negative (Figure 2).

Conclusions

DITMA is a known risk of proteasome inhibitors and is listed as a safety warning in the prescribing information for bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib.12 Given the overall rarity of this adverse event, the simultaneous presentation of our 2 cases was unexpected and underscores the need for heightened awareness in clinical practice. In addition, while no underlying complement mutations were identified, eculizumab was used in both cases to successfully stabilize renal function. Further research investigating the efficacy of eculizumab and the role of complement activation in proteasome inhibitor–induced TMA will be valuable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients whose histories are reported in this manuscript as well as the physicians and staff who provided care during the hospitalizations and beyond. We also thank Oscar Silva, MD, PhD, for his assistance in reviewing and formatting the peripheral blood smear images.

As a class of drugs, proteasome inhibitors are known to rarely cause drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy (DITMA). In particular, carfilzomib is a second-generation, irreversible proteasome inhibitor approved for the treatment of relapsed, refractory multiple myeloma (MM) in combination with other therapeutic agents.1 Although generally well tolerated, carfilzomib has been associated with serious adverse events such as cardiovascular toxicity and DITMA.2-4 Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is a life-threatening disorder characterized by thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and end-organ damage.5 Its occurrence secondary to carfilzomib has been reported only rarely in clinical trials of MM, and the most effective management of the disorder as well as the concurrent risk factors that contribute to its development remain incompletely understood.6,7 As a result, given both the expanding use of carfilzomib in practice and the morbidity of TMA, descriptions of carfilzomib-induced TMA from the real-world setting continue to provide important contributions to our understanding of the disorder.

At our US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center, 2 patients developed severe carfilzomib-induced TMA within days of one another. The presentation of simultaneous cases was highly unexpected and offered the unique opportunity to compare clinical features in real time. Here, we describe our 2 cases in detail, review their presentations and management in the context of the prior literature, and discuss potential insights gained into the disease.

Case Presentation

Case 1

A 78-year-old male patient was diagnosed with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance in 2012 that progressed to Revised International Staging System stage II IgG-κ MM in 2016 due to worsening anemia with a hemoglobin level < 10 g/dL (Table 1). He was treated initially with 8 cycles of first-line bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone, to which he achieved a partial response with > 50% reduction in serum M-protein. He then received 3 cycles of maintenance bortezomib until relapse, at which time he was switched to second-line therapy consisting of carfilzomib 20 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 and 56 mg/m2 on days 8, 9, 15, and 16 for cycle 1, followed by 56 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 for subsequent cycles plus dexamethasone 20 mg twice weekly every 28 days.

After the patient received cycle 3, day 1 of carfilzomib, he developed subjective fevers, chills, and diarrhea. He missed his day 2 infusion and instead presented to the VA emergency department, where his vital signs were stable and laboratory tests were notable for the following levels: leukocytosis of20.3 K/µL (91.7% neutrophils), hemoglobin 12.4 g/dL (prior 13.5 g/dL), platelet count 171 K/µL, and creatinine 1.39 mg/dL (prior 1.13 g/dL). A chest X-ray demonstrated diffuse bilateral opacities concerning for edema vs infection, and he was started empirically on vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and azithromycin. His outpatient medications, which included acyclovir, aspirin, finasteride, oxybutynin, ranitidine, omega-3 fatty acids, fish oil, vitamin D, and senna, were continued as indicated.

On hospital day 2, the patient’s platelet count dropped to 81 K/µL and creatinine level rose to 1.78 mg/dL. He developed dark urine (urinalysis [UA] 3+ blood, 6-11 red blood cells per high power field [RBC/HPF]) and had laboratory tests suggestive of hemolysis, including lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) > 1,200 IU/L (reference range, 60-250 IU/L), haptoglobin < 30 mg/dL (reference range, 44-215 mg/dL), total bilirubin 3.2 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1.3 mg/dL; indirect bilirubin, 2.6 mg/dL), and a peripheral blood smear demonstrating moderate microangiopathy (Figure 1).

Workup for alternative causes of thrombocytopenia included a negative heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel and a disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) panel showing elevated fibrinogen (515 mg/dL; reference range, 200-400 mg/dL) and mildly elevated international normalized ratio (INR) (1.3). Blood cultures were negative, and a 22-pathogen gastrointestinal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel failed to identify viral or bacterial pathogens, including Escherichia coli O157:H7. C3 (81 mg/dL; reference range, 90-180 mg/dL) and C4 (16 mg/dL; reference range, 16-47 mg/dL) complement levels were borderline to mildly reduced.

Based on this constellation of findings, a diagnosis of TMA was made, and the patient was started empirically on plasma exchange and pulse-dosed steroids. After 4 cycles of plasma exchange, the platelet count had normalized from its nadir of 29 K/µL. ADAMTS13 activity (98% enzyme activity) ruled out thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), and the patient continued to have anuric renal failure (creatinine, 8.62 mg/dL) necessitating the initiation of hemodialysis. Given persistent renal insufficiency, a diagnosis of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) was considered, and eculizumab 900 mg was administered on days 8 and 15 with stabilization of renal function. By the time of discharge on day 18, the patient’s creatinine level had decreased to 3.89 mg/dL, and platelet count was 403 K/µL. Creatinine normalized to 1.07 mg/dL by day 46.

Outpatient genetic testing through the BloodCenter of Wisconsin Diagnostic Laboratories was negative for mutations in the following genes associated with atypical HUS: CFH, CFI, MCP (CD46), THBD, CFB, C3, DGKE, ADAMTS13, C4BPA, C4BPB, LMNA, CFHR1, CFHR3, CFHR4, and CFHR5. The patient subsequently remained off all antimyeloma therapy for > 1 year until eventually starting third-line pomalidomide plus dexamethasone without reinitiation of proteasome inhibitor therapy.

Case 2

A 59-year-old male patient, diagnosed in 2013 with ISS stage I IgG-κ MM after presenting with compression fractures, completed 8 cycles of cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone before undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with complete response (Table 1). He subsequently received single-agent maintenance bortezomib until relapse nearly 2 years later, at which time he started second-line carfilzomib 20 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 and 27 mg/m2 on days 8, 9, 15, and 16 for cycle 1, followed by 27 mg/m2 on days 8, 9, 15, and 16 for cycles 2 to 8, lenalidomide 25 mg on days 1 to 21, and dexamethasone 40 mg weekly every 28 days. Serum free light chain levels normalized after 9 cycles, and he subsequently began maintenance carfilzomib 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 15 plus lenalidomide 10 mg on days 1 to 21 every 28 days.

On the morning before admission, the patient received C6D17 of maintenance carfilzomib, which had been delayed from day 15 because of the holiday. Later that evening, he developed nausea, vomiting, and fever of 101.3 °F. He presented to the VA emergency department and was tachycardic (108 beats per minute) and hypotensive (86/55 mm Hg). Laboratory tests were notable for hemoglobin level 9.9 g/dL (prior 11.6 g/dL), platelet count 270 K/µL, and creatinine level 1.86 mg/dL (prior 1.12 mg/dL). A respiratory viral panel was positive for influenza A, and antimicrobial agents were eventually broadened to piperacillin-tazobactam, azithromycin, and oseltamivir. His outpatient medications, which included acyclovir, zoledronic acid, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, aspirin, amlodipine, atorvastatin, omeprazole, zolpidem, calcium, vitamin D, loratadine, ascorbic acid, and prochlorperazine, were continued as indicated.

On hospital day 2, the patient’s platelet count declined from 211 to 57 K/µL. He developed tea-colored urine (UA 2+ blood, 0-2 RBC/HPF) and had laboratory tests suggestive of hemolysis, including LDH 910 IU/L (reference range, 60-250 IU/L), total bilirubin 3.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1.3 mg/dL; no direct or indirect available), and a peripheral blood smear demonstrating moderate microangiopathy. Although haptoglobin level was normal at this time (206 mg/dL; reference range, 44-215 mg/dL), it decreased to 42 mg/dL by the following day. Additional workup included a negative direct Coombs and a DIC panel showing elevated fibrinogen (596 mg/dL; reference range, 200-400 mg/dL) and mildly elevated INR (1.16). Blood cultures remained negative, and a 22-pathogen GI PCR panel identified no viral or bacterial pathogens, including E coli O157:H7. C3 (114 mg/dL; reference range, 90-180 mg/dL) and C4 (40 mg/dL; reference range, 16-47 mg/dL) complement levels were both normal.

Based on these findings, empiric treatment was started with plasma exchange and pulse-dosed steroids. The patient received 3 cycles of plasma exchange until the results of the ADAMTS13 activity ruled out TTP (63% enzyme activity). Over the next 6 days, his platelet count reached a nadir of 6 K/µL and creatinine level peaked at 10.36 mg/dL, necessitating the initiation of hemodialysis. Given severe renal insufficiency, a diagnosis of atypical HUS was again considered, and eculizumab 900 mg was administered on days 9 and 16 with stabilization of renal function. By the time of discharge on day 17, the patient’s creatinine level had decreased to 4.17 mg/dL and platelet count was 164 K/µL. Creatinine level normalized to 1.02 mg/dL by day 72.

Outpatient genetic testing through the BloodCenter of Wisconsin Diagnostic Laboratories was negative for gene mutations associated with atypical HUS. Approximately 1 month after discharge, the patient resumed maintenance lenalidomide alone without reinitiation of proteasome inhibitor therapy.

Discussion

In this case series, we describe the uncommon drug-related adverse event of TMA occurring in 2 patients with MM after receiving carfilzomib. Although the incidence of TMA disorders is low, reaching up to 2.8% in patients receiving carfilzomib plus cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone in the phase 2 CARDAMON trial, our experience suggests that a high index of suspicion for carfilzomib-induced TMA is warranted in the real-world setting.8 TMA syndromes, including TTP, HUS, and DITMA, are characterized by microvascular endothelial injury and thrombosis leading to thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.5,9 Several drug culprits of DITMA are recognized, including quinine, gemcitabine, tacrolimus, and proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib, carfilzomib, ixazomib).10-12 In a real-world series of patients receiving proteasome inhibitor therapy, either carfilzomib (n=8) or bortezomib (n=3), common clinical features of DITMA included thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, gastrointestinal symptoms, and renal insufficiency with or without a need for hemodialysis.2 Although DITMA has been described primarily as an early event, its occurrence after 12 months of proteasome inhibitor therapy has also been reported, both in this series and elsewhere, thereby suggesting an ongoing risk for DITMA throughout the duration of carfilzomib treatment.2,13

The diagnosis of DITMA can be challenging given its nonspecific symptoms that overlap with other TMA syndromes. Previous studies have proposed that for a drug to be associated with DITMA, there should be: (1) evidence of clinical and/or pathologic findings of TMA; (2) exclusion of alternative causes of TMA; (3) no other new drug exposures other than the suspected culprit medication; and (4) a lack of recurrence of TMA in absence of the drug.10 In the case of patients with MM, other causes of TMA have also been described, including the underlying plasma cell disorder itself and stem cell transplantation.14 In the 2 cases we have described, these alternative causes were considered unlikely given that only 1 patient underwent transplantation remotely and neither had a previous history of TMA secondary to their disease. With respect to other TMA syndromes, ADAMTS13 levels > 10% and negative stool studies for E coli O157:H7 suggested against TTP or typical HUS, respectively. No other drug culprits were identified, and the close timing between the receipt of carfilzomib and symptom onset supported a causal relationship.

Because specific therapies are lacking, management of DITMA has traditionally included drug discontinuation and supportive care for end-organ injury.5 The terminal complement inhibitor, eculizumab, improves hematologic abnormalities and renal function in patients with atypical HUS but its use for treating patients with DITMA is not standard.15 Therefore, the decision to administer eculizumab to our 2 patients was driven by their severe renal insufficiency without improvement after plasma exchange, which suggested a phenotype similar to atypical HUS. After administration of eculizumab, renal function stabilized and then gradually improved over weeks to months, a time course similar to that described in cases of patients with DITMA secondary to other anticancer therapies treated with eculizumab.16 Although these results suggest a potential role for eculizumab in proteasome inhibitor–induced TMA, distinguishing the benefit of eculizumab over drug discontinuation alone remains challenging, and well-designed prospective investigations are needed.

The clustered occurrence of our 2 cases is unique from previous reports that describe carfilzomib-induced TMA as a sporadic event (Table 2).13,17-28 Both immune-mediated and direct toxic effects have been proposed as mechanisms of DITMA, and while our cases do not differentiate between these mechanisms, we considered whether a combined model of initiation, whereby patient or environmental risk factors modulate occurrence of the disease in conjunction with the inciting drug, could explain the clustered occurrence of cases. In this series, drug manufacturing was not a shared risk factor as each patient received carfilzomib from different lot numbers. Furthermore, other patients at our center received carfilzomib from the same batches without developing DITMA. We also considered the role of infection given that 1 patient was diagnosed with influenza A and both presented with nonspecific, viral-like symptoms during the winter season. Interestingly, concurrent viral infections have been reported in other cases of carfilzomib-induced DITMA as well and have also been discussed as a trigger of atypical HUS.20,29 Finally, genetic testing was negative for complement pathway mutations that might predispose to complement dysregulation.

The absence of complement mutations in our 2 patients differs from a recent series describing heterozygous CFHR3-CHFR1 deletions in association with carfilzomib-induced TMA.22 In that report, the authors hypothesized that carfilzomib decreases expression of complement factor H (CFH), a negative regulator of complement activation, thereby leading to complement dysregulation in patients who are genetically predisposed. In a second series, plasma from patients with DITMA secondary to carfilzomib induced the deposition of the complement complex, C5b-9, on endothelial cells in culture, suggesting activation of the complement pathway.30 The effective use of eculizumab would also point to a role for complement activation, and ongoing investigations should aim to identify the triggers and mechanisms of complement dysregulation in this setting, especially for patients like ours in whom genetic testing for complement pathway mutations is negative (Figure 2).

Conclusions

DITMA is a known risk of proteasome inhibitors and is listed as a safety warning in the prescribing information for bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib.12 Given the overall rarity of this adverse event, the simultaneous presentation of our 2 cases was unexpected and underscores the need for heightened awareness in clinical practice. In addition, while no underlying complement mutations were identified, eculizumab was used in both cases to successfully stabilize renal function. Further research investigating the efficacy of eculizumab and the role of complement activation in proteasome inhibitor–induced TMA will be valuable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients whose histories are reported in this manuscript as well as the physicians and staff who provided care during the hospitalizations and beyond. We also thank Oscar Silva, MD, PhD, for his assistance in reviewing and formatting the peripheral blood smear images.

1. McBride A, Klaus JO, Stockeri-Goldstein K. Carfilzomib: a second-generation proteasome inhibitor for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(5):353-360. doi:10.2146/ajhp130281

2. Yui JC, Van Keer J, Weiss BM, et al. Proteasome inhibitor associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(9):E348-E352. doi:10.1002/ajh.24447

3. Dimopoulos MA, Roussou M, Gavriatopoulou M, et al. Cardiac and renal complications of carfilzomib in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2017;1(7):449-454. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2016003269

4. Chari A, Stewart AK, Russell SD, et al. Analysis of carfilzomib cardiovascular safety profile across relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma clinical trials. Blood Adv. 2018;2(13):1633-1644. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2017015545

5. George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):654-666. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1312353

6. Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Palumbo A, et al. Carfilzomib and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (ENDEAVOR): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(1):27-38. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00464-7

7. Dimopoulos M, Quach H, Mateos MV, et al. Carfilzomib, dexamethasone, and daratumumab versus carfilzomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CANDOR): results from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2020;396(10245):186-197. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30734-0

8. Camilleri M, Cuadrado M, Phillips E, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy in untreated myeloma patients receiving carfilzomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone on the CARDAMON study. Br J Haematol. 2021;193(4):750-760. doi:10.1111/bjh.17377

9. Masias C, Vasu S, Cataland SR. None of the above: thrombotic microangiopathy beyond TTP and HUS. Blood. 2017;129(21):2857-2863. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-11-743104

10. Al-Nouri ZL, Reese JA, Terrell DR, Vesely SK, George JN. Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: a systemic review of published reports. Blood. 2015;125(4):616-618. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-11-611335

11. Saleem R, Reese JA, George JN. Drug-induced thrombotic-microangiopathy: an updated systematic review, 2014-2018. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(9):E241-E243. doi:10.1002/ajh.25208

12 Nguyen MN, Nayernama A, Jones SC, Kanapuru B, Gormley N, Waldron PE. Proteasome inhibitor-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: a review of cases reported to the FDA adverse event reporting system and published in the literature. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(9):E218-E222. doi:10.1002/ajh.25832

13. Haddadin M, Al-Sadawi M, Madanat S, et al. Late presentation of carfilzomib associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Am J Med Case Rep. 2019;7(10):240-243. doi:10.12691/ajmcr-7-10-5

14 Portuguese AJ, Gleber C, Passero Jr FC, Lipe B. A review of thrombotic microangiopathies in multiple myeloma. Leuk Res. 2019;85:106195. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2019.106195

15. Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, et al. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2169-2181. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208981

16. Olson SR, Lu E, Sulpizio E, Shatzel JJ, Rueda JF, DeLoughery TG. When to stop eculizumab in complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathies. Am J Nephrol. 2018;48(2):96-107. doi:10.1159/000492033

17. Lodhi A, Kumar A, Saqlain MU, Suneja M. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with proteasome inhibitors. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(5):632-636. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfv059

18. Sullivan MR, Danilov AV, Lansigan F, Dunbar NM. Carfilzomib associated thrombotic microangiopathy initially treated with therapeutic plasma exchange. J Clin Apher., 2015;30(5):308-310. doi:10.1002/jca.21371

19. Qaqish I, Schlam IM, Chakkera HA, Fonseca R, Adamski J. Carfilzomib: a cause of drug associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Transfus Apher Sci. 2016;54(3):401-404. doi:10.1016/j.transci.2016.03.002

20. Chen Y, Ooi M, Lim SF, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy during carfilzomib use: case series in Singapore. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6(7):e450. doi:10.1038/bcj.2016.62

21. Gosain R, Gill A, Fuqua J, et al. Gemcitabine and carfilzomib induced thrombotic microangiopathy: eculizumab as a life-saving treatment. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(12):1926-1930. doi:10.1002/ccr3.1214

22. Portuguese AJ, Lipe B. Carfilzomib-induced aHUS responds to early eculizumab and may be associated with heterozygrous CFHR3-CFHR1 deletion. Blood Adv. 2018;2(23):3443-3446. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018027532

23. Moliz C, Gutiérrez E, Cavero T, Redondo B, Praga M. Eculizumab as a treatment for atypical hemolytic syndrome secondary to carfilzomib. Nefrologia (Engl Ed). 2019;39(1):86-88. doi:10.1016/j.nefro.2018.02.005

24. Jeyaraman P, Borah P, Singh A, et al., Thrombotic microangiopathy after carfilzomib in a very young myeloma patient. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2020;81:102400. doi:10.1016/j.bcmd.2019.102400

25. Bhutani D, Assal A, Mapara MY, Prinzing S, Lentzsch S. Case report: carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy with complement activation treated successfully with eculizumab. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(4):e155-e157. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2020.01.016

26. Jindal N, Jandial A, Jain A, et al. Carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: a case based review. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2020;S1658-3876(20)30118-7. doi:10.1016/j.hemonc.2020.07.001

27. Monteith BE, Venner CP, Reece DE, et al. Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy with concurrent proteasome inhibitor use in the treatment of multiple myeloma: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(11):e791-e780. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2020.04.014

28. Rassner M, Baur R, Wäsch R, et al. Two cases of carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy successfully treated with eculizumab in multiple myeloma. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12882-020-02226-5

29. Kavanagh D, Goodship THJ. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, genetic basis, and clinical manifestations. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:15-20. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.15

30. Blasco M, Martínez-Roca A, Rodríguez-Lobato LG, et al. Complement as the enabler of carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy. Br J Haematol. 2021;193(1):181-187. doi:10.1111/bjh.16796

1. McBride A, Klaus JO, Stockeri-Goldstein K. Carfilzomib: a second-generation proteasome inhibitor for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(5):353-360. doi:10.2146/ajhp130281

2. Yui JC, Van Keer J, Weiss BM, et al. Proteasome inhibitor associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(9):E348-E352. doi:10.1002/ajh.24447

3. Dimopoulos MA, Roussou M, Gavriatopoulou M, et al. Cardiac and renal complications of carfilzomib in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2017;1(7):449-454. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2016003269

4. Chari A, Stewart AK, Russell SD, et al. Analysis of carfilzomib cardiovascular safety profile across relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma clinical trials. Blood Adv. 2018;2(13):1633-1644. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2017015545

5. George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):654-666. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1312353

6. Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Palumbo A, et al. Carfilzomib and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (ENDEAVOR): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(1):27-38. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00464-7

7. Dimopoulos M, Quach H, Mateos MV, et al. Carfilzomib, dexamethasone, and daratumumab versus carfilzomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CANDOR): results from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2020;396(10245):186-197. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30734-0

8. Camilleri M, Cuadrado M, Phillips E, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy in untreated myeloma patients receiving carfilzomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone on the CARDAMON study. Br J Haematol. 2021;193(4):750-760. doi:10.1111/bjh.17377

9. Masias C, Vasu S, Cataland SR. None of the above: thrombotic microangiopathy beyond TTP and HUS. Blood. 2017;129(21):2857-2863. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-11-743104

10. Al-Nouri ZL, Reese JA, Terrell DR, Vesely SK, George JN. Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: a systemic review of published reports. Blood. 2015;125(4):616-618. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-11-611335

11. Saleem R, Reese JA, George JN. Drug-induced thrombotic-microangiopathy: an updated systematic review, 2014-2018. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(9):E241-E243. doi:10.1002/ajh.25208

12 Nguyen MN, Nayernama A, Jones SC, Kanapuru B, Gormley N, Waldron PE. Proteasome inhibitor-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: a review of cases reported to the FDA adverse event reporting system and published in the literature. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(9):E218-E222. doi:10.1002/ajh.25832

13. Haddadin M, Al-Sadawi M, Madanat S, et al. Late presentation of carfilzomib associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Am J Med Case Rep. 2019;7(10):240-243. doi:10.12691/ajmcr-7-10-5

14 Portuguese AJ, Gleber C, Passero Jr FC, Lipe B. A review of thrombotic microangiopathies in multiple myeloma. Leuk Res. 2019;85:106195. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2019.106195

15. Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, et al. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2169-2181. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208981

16. Olson SR, Lu E, Sulpizio E, Shatzel JJ, Rueda JF, DeLoughery TG. When to stop eculizumab in complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathies. Am J Nephrol. 2018;48(2):96-107. doi:10.1159/000492033

17. Lodhi A, Kumar A, Saqlain MU, Suneja M. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with proteasome inhibitors. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(5):632-636. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfv059

18. Sullivan MR, Danilov AV, Lansigan F, Dunbar NM. Carfilzomib associated thrombotic microangiopathy initially treated with therapeutic plasma exchange. J Clin Apher., 2015;30(5):308-310. doi:10.1002/jca.21371

19. Qaqish I, Schlam IM, Chakkera HA, Fonseca R, Adamski J. Carfilzomib: a cause of drug associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Transfus Apher Sci. 2016;54(3):401-404. doi:10.1016/j.transci.2016.03.002

20. Chen Y, Ooi M, Lim SF, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy during carfilzomib use: case series in Singapore. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6(7):e450. doi:10.1038/bcj.2016.62

21. Gosain R, Gill A, Fuqua J, et al. Gemcitabine and carfilzomib induced thrombotic microangiopathy: eculizumab as a life-saving treatment. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(12):1926-1930. doi:10.1002/ccr3.1214

22. Portuguese AJ, Lipe B. Carfilzomib-induced aHUS responds to early eculizumab and may be associated with heterozygrous CFHR3-CFHR1 deletion. Blood Adv. 2018;2(23):3443-3446. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018027532

23. Moliz C, Gutiérrez E, Cavero T, Redondo B, Praga M. Eculizumab as a treatment for atypical hemolytic syndrome secondary to carfilzomib. Nefrologia (Engl Ed). 2019;39(1):86-88. doi:10.1016/j.nefro.2018.02.005

24. Jeyaraman P, Borah P, Singh A, et al., Thrombotic microangiopathy after carfilzomib in a very young myeloma patient. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2020;81:102400. doi:10.1016/j.bcmd.2019.102400

25. Bhutani D, Assal A, Mapara MY, Prinzing S, Lentzsch S. Case report: carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy with complement activation treated successfully with eculizumab. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(4):e155-e157. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2020.01.016

26. Jindal N, Jandial A, Jain A, et al. Carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: a case based review. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2020;S1658-3876(20)30118-7. doi:10.1016/j.hemonc.2020.07.001

27. Monteith BE, Venner CP, Reece DE, et al. Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy with concurrent proteasome inhibitor use in the treatment of multiple myeloma: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(11):e791-e780. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2020.04.014

28. Rassner M, Baur R, Wäsch R, et al. Two cases of carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy successfully treated with eculizumab in multiple myeloma. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12882-020-02226-5

29. Kavanagh D, Goodship THJ. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, genetic basis, and clinical manifestations. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:15-20. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.15

30. Blasco M, Martínez-Roca A, Rodríguez-Lobato LG, et al. Complement as the enabler of carfilzomib-induced thrombotic microangiopathy. Br J Haematol. 2021;193(1):181-187. doi:10.1111/bjh.16796