User login

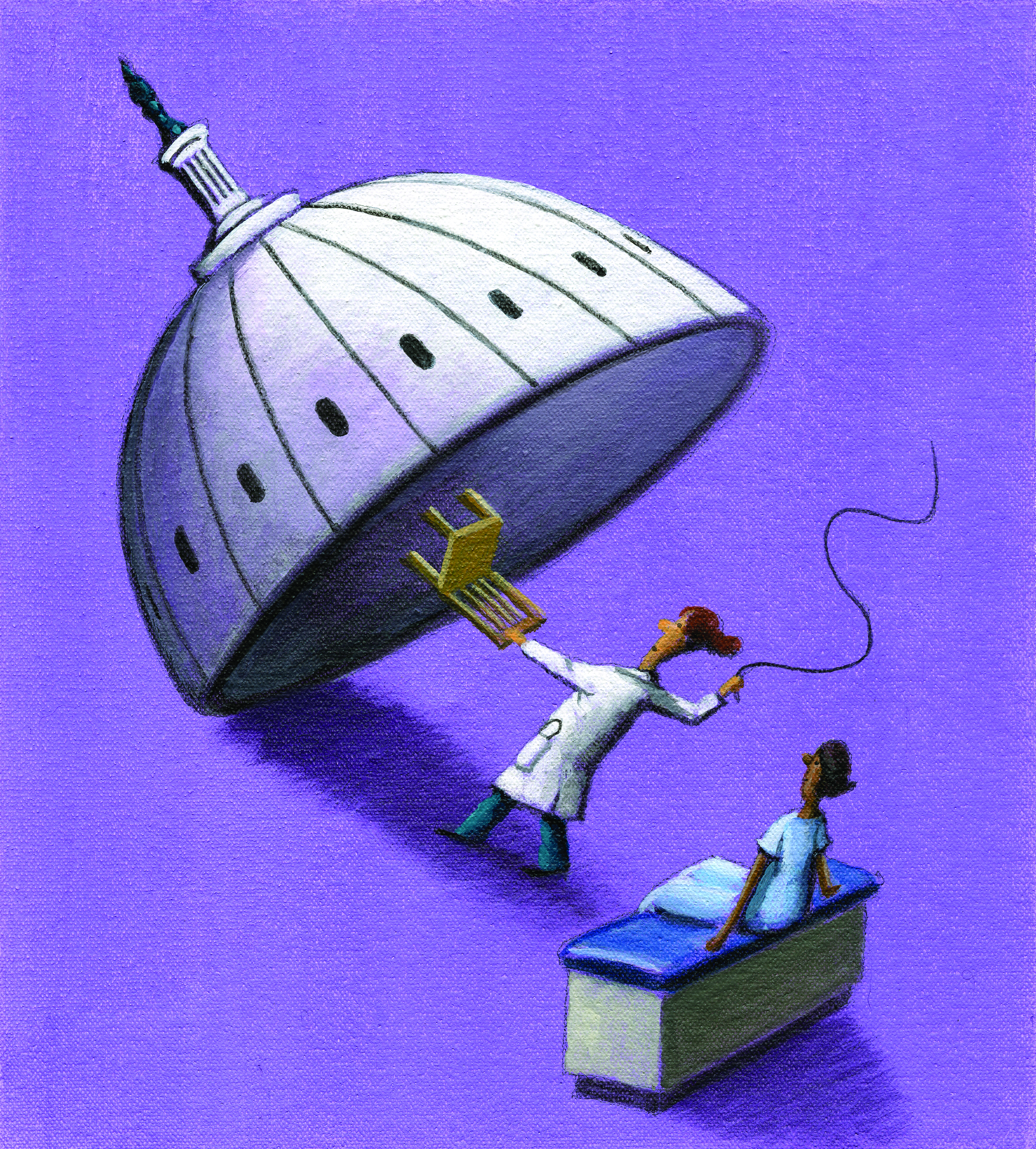

Targeting US maternal mortality: ACOG’s recent strides and future action

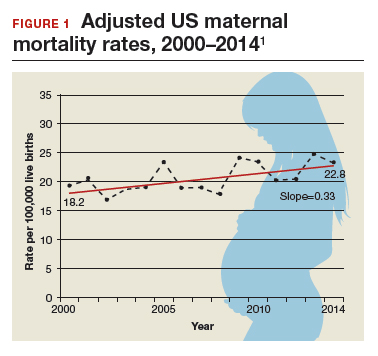

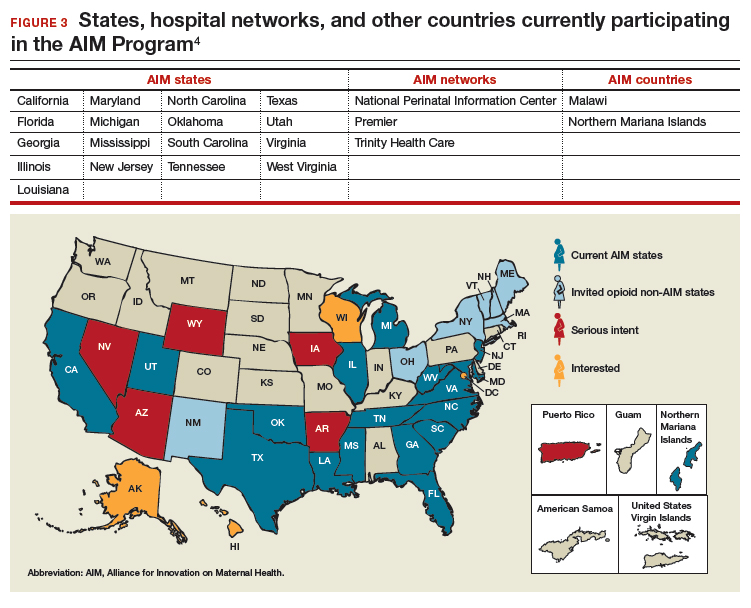

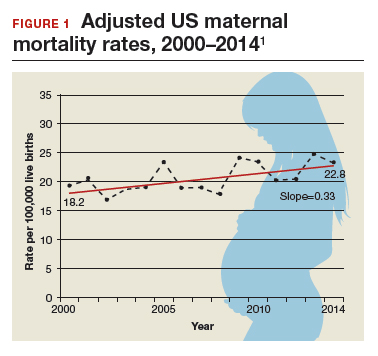

Real progress was achieved in 2018 in the effort to reduce the US maternal mortality rate, the highest of any developed nation and where women of color are 3 to 4 times more likely than others to die of childbirth-related causes. Importantly, the United States is the only nation other than Afghanistan and Sudan where the rate is rising.1

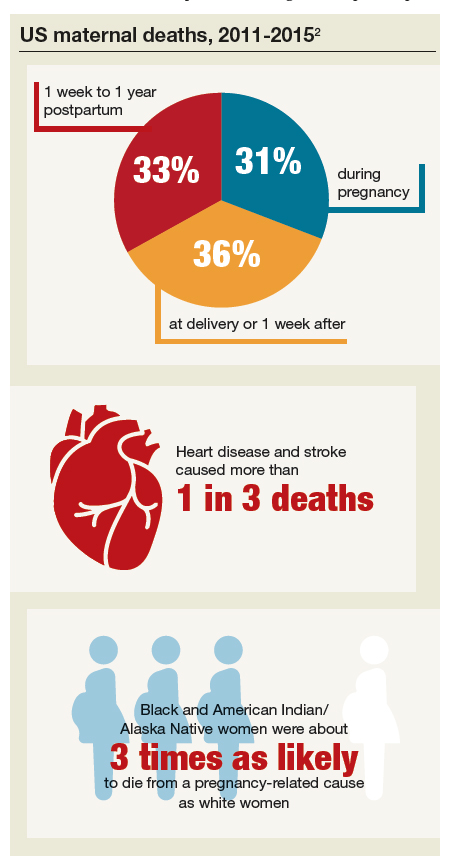

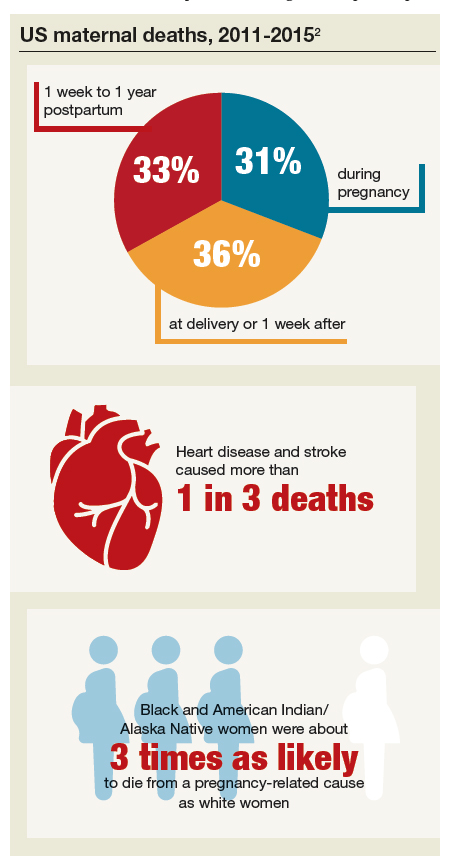

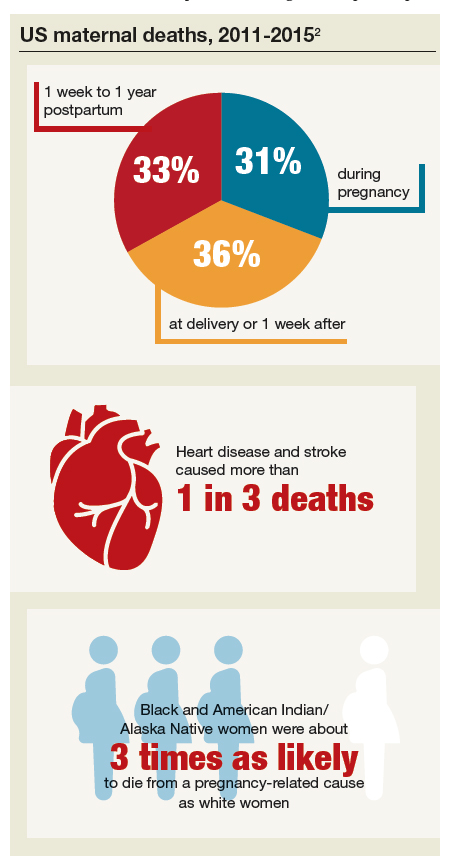

In May 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a Vital Signs document focused on preventable maternal deaths.2 It affirmed that about 60% of the 700 pregnancy-related deaths that occur annually in the United States are preventable, and it provided important information on when and why these deaths occur.

Among the CDC findings, about:

- one-third of deaths (31%) occurred during pregnancy (before delivery)

- one-third (36%) occurred at delivery or in the week after

- one-third (33%) occurred 1 week to 1 year postpartum.

In addition, the CDC highlighted that:

- Heart disease and stroke caused more than 1 in 3 deaths (34%). Infections and severe bleeding were other leading causes of death.

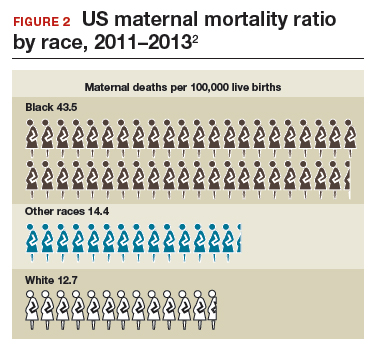

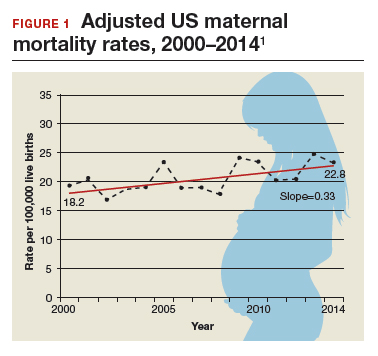

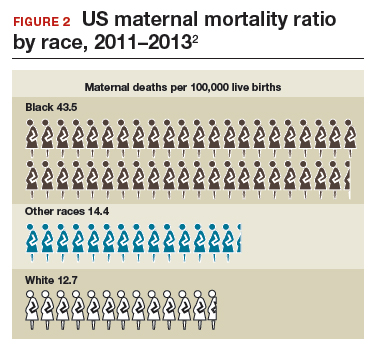

- Black and American Indian/Alaska Native women were about 3 times as likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause as white women.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Lisa Hollier, MD, MPH (2018–2019), fully embraced the challenge and responsibility of meaningfully improving health care for every mom. In this article, I review some of the critical steps taken in 2018 and preview ACOG’s continued commitment for 2019 and beyond.

Efforts succeed: Bills are now laws of the land

ACOG and our partner organizations, including the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the March of Dimes, have long recognized the value of state-based maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) in slowing and reversing the rate of maternal mortality. An MMRC brings together local experts to examine the causes of maternal deaths—not to find fault, but to find ways to prevent future deaths. With the right framework and support, MMRCs already are providing us with data and driving policy recommendations.

Supporting MMRCs in all states. With this in mind, ACOG helped pass and push to enactment HR 1318, the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018 (Public Law No. 115-344), a bipartisan bill designed to help develop and provide support for MMRCs in every state. The bill was introduced in the US House of Representatives by Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-WA) and Rep. Diana DeGette (D-CO) and in the US Senate by Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND) and Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV). ACOG Fellow and US Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX), also was instrumental in the bill’s success. The CDC is actively working toward implementation of this law, and grantees are expected to be announced by the end of September.

Continue to: In addition, ACOG worked with Congress...

In addition, ACOG worked with Congress to secure $50 million in federal funding to reduce maternal mortality, allocated thusly:

- $12 million to support state MMRCs

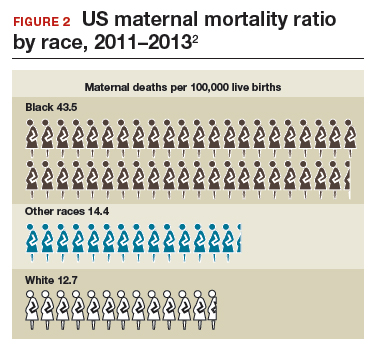

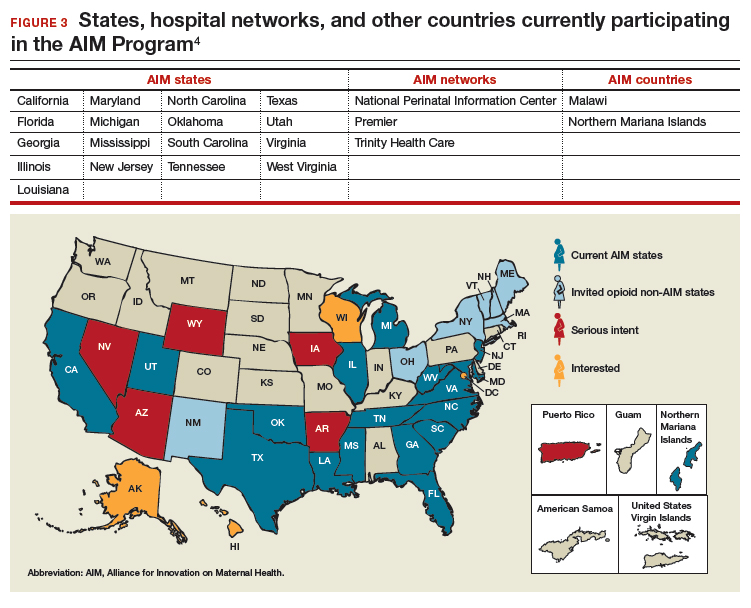

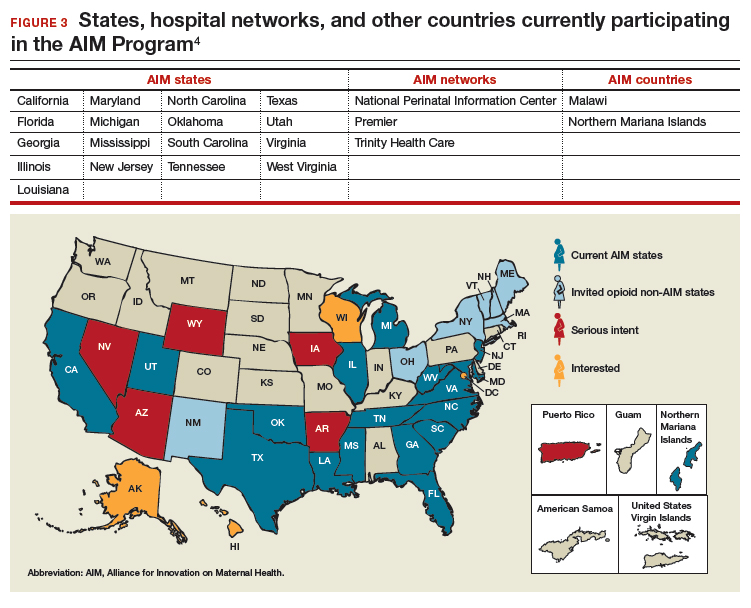

- $3 million to support the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health

- $23 million for State Maternal Health Innovation Program grants

- $12 million to address maternal mortality in the Healthy Start program.

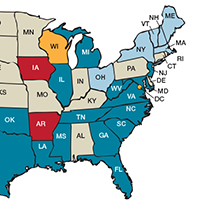

As these federal congressional initiatives worked their way into law, the states actively supported MMRCs as well. As of this writing, only 3 states—North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming—have not yet developed an MMRC.3

Filling the gaps in ObGyn care. Another key ACOG-sponsored bill signed into law will help bring more ObGyns into shortage areas. Sponsored by Rep. Burgess, Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-CA), and Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA) and by Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) and Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), the Improving Access to Maternity Care Act (Public Law No. 115-320) requires the Department of Health and Human Services to identify maternity health professional target areas for use by the National Health Service Corps to bring ObGyns to where they are most needed.

Following up on that new law, ACOG currently is working closely with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the National Rural Health Association (NRHA) on the unique challenges women in rural areas face in accessing maternity and other women’s health care services. In June, Dr. Hollier represented ACOG at the Rural Maternal Health forum, which was convened by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid and sponsored by ACOG, AAFP, and NRHA.4 We are pursuing policies designed to increase the number of ObGyns and other physicians who choose to train in rural areas and increase the clinical use of telehealth to help connect rural physicians and patients with subspecialists in urban areas.

Projects in the works

Congress is ready to do more. Already, 5 ACOG-supported bills have been introduced, including bills that extend women’s Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum (consistent with coverage for babies), support state perinatal quality collaboratives, and more. This interest is augmented by the work of the recently formed congressional Black Maternal Health Caucus, focused on reducing racial disparities in health care. In July, ACOG joined 12 members of Congress in a caucus summit to partner with these important congressional allies.

ACOG is expanding support for these legislative efforts through our work with another important ally, the American Medical Association (AMA). ACOG’s delegation to the 2019 Annual Meeting of the AMA House of Delegates in June scored important policy wins, including AMA support for Medicaid coverage for women 12 months postpartum and improving access to care in rural communities.

There is momentum on Capitol Hill to take action on these important issues, and ACOG’s priority is to ensure that any legislative package complements the important work many ObGyns are already doing to improve maternal health outcomes. ACOG has an important seat at the table and will continue to advocate each and every day for your practices and your patients as Congress deliberates legislative action.

Continue to: Your voice matters...

Your voice matters

Encourage your representatives in the House and the Senate to support ACOG-endorsed legislation and be sure they know the importance of ensuring access to women’s health care in your community. Get involved in advocacy; start by visiting the ACOG advocacy web page (www.acog.org/advocacy). Also note that members of Congress are back in their home states during seasonal breaks and many hold town halls and constituent meetings. The health of moms and babies is always an important issue, and you are the expert.

ACOG’s commitment to ensuring healthy moms and babies, and ensuring that our members can continue providing high-quality care, runs through everything we do.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks ACOG former Vice President for Health Policy Barbara Levy, MD, ACOG Senior Director Jeanne Mahoney, and ACOG Federal Affairs Director Rachel Tetlow for their helpful review and comments.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women's Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program. https://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-program/. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: pregnancy-related deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/maternal-deaths/index.html. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. State Maternal Mortality Review Committees, PQCs, and AIM. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/Government-Relations-and-Outreach/MMRC_AIM-State-Fact-Sheet_Mar-2019.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. A conversation on maternal health care in rural communities: charting a path to improved access, quality and outcomes. June 12, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/equity-initiatives/rural-health/rural-maternal-health.html. Accessed August 19, 2019.

Real progress was achieved in 2018 in the effort to reduce the US maternal mortality rate, the highest of any developed nation and where women of color are 3 to 4 times more likely than others to die of childbirth-related causes. Importantly, the United States is the only nation other than Afghanistan and Sudan where the rate is rising.1

In May 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a Vital Signs document focused on preventable maternal deaths.2 It affirmed that about 60% of the 700 pregnancy-related deaths that occur annually in the United States are preventable, and it provided important information on when and why these deaths occur.

Among the CDC findings, about:

- one-third of deaths (31%) occurred during pregnancy (before delivery)

- one-third (36%) occurred at delivery or in the week after

- one-third (33%) occurred 1 week to 1 year postpartum.

In addition, the CDC highlighted that:

- Heart disease and stroke caused more than 1 in 3 deaths (34%). Infections and severe bleeding were other leading causes of death.

- Black and American Indian/Alaska Native women were about 3 times as likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause as white women.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Lisa Hollier, MD, MPH (2018–2019), fully embraced the challenge and responsibility of meaningfully improving health care for every mom. In this article, I review some of the critical steps taken in 2018 and preview ACOG’s continued commitment for 2019 and beyond.

Efforts succeed: Bills are now laws of the land

ACOG and our partner organizations, including the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the March of Dimes, have long recognized the value of state-based maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) in slowing and reversing the rate of maternal mortality. An MMRC brings together local experts to examine the causes of maternal deaths—not to find fault, but to find ways to prevent future deaths. With the right framework and support, MMRCs already are providing us with data and driving policy recommendations.

Supporting MMRCs in all states. With this in mind, ACOG helped pass and push to enactment HR 1318, the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018 (Public Law No. 115-344), a bipartisan bill designed to help develop and provide support for MMRCs in every state. The bill was introduced in the US House of Representatives by Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-WA) and Rep. Diana DeGette (D-CO) and in the US Senate by Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND) and Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV). ACOG Fellow and US Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX), also was instrumental in the bill’s success. The CDC is actively working toward implementation of this law, and grantees are expected to be announced by the end of September.

Continue to: In addition, ACOG worked with Congress...

In addition, ACOG worked with Congress to secure $50 million in federal funding to reduce maternal mortality, allocated thusly:

- $12 million to support state MMRCs

- $3 million to support the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health

- $23 million for State Maternal Health Innovation Program grants

- $12 million to address maternal mortality in the Healthy Start program.

As these federal congressional initiatives worked their way into law, the states actively supported MMRCs as well. As of this writing, only 3 states—North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming—have not yet developed an MMRC.3

Filling the gaps in ObGyn care. Another key ACOG-sponsored bill signed into law will help bring more ObGyns into shortage areas. Sponsored by Rep. Burgess, Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-CA), and Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA) and by Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) and Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), the Improving Access to Maternity Care Act (Public Law No. 115-320) requires the Department of Health and Human Services to identify maternity health professional target areas for use by the National Health Service Corps to bring ObGyns to where they are most needed.

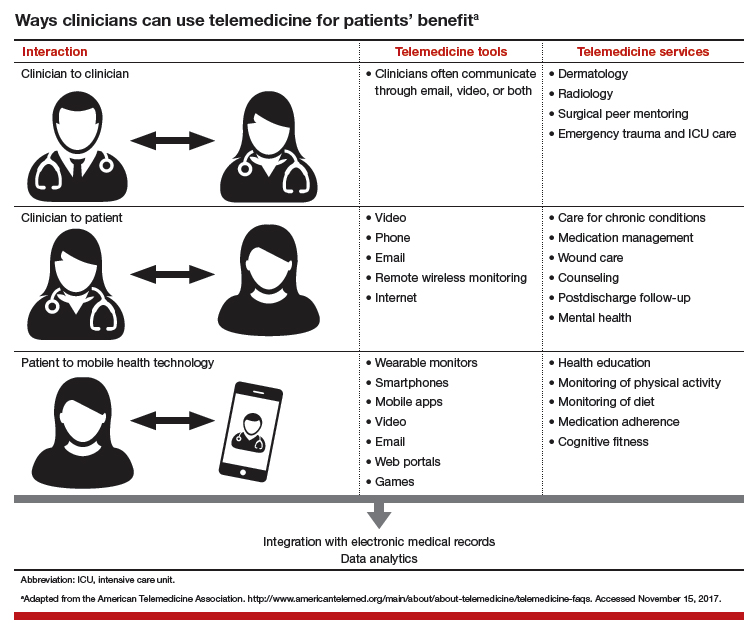

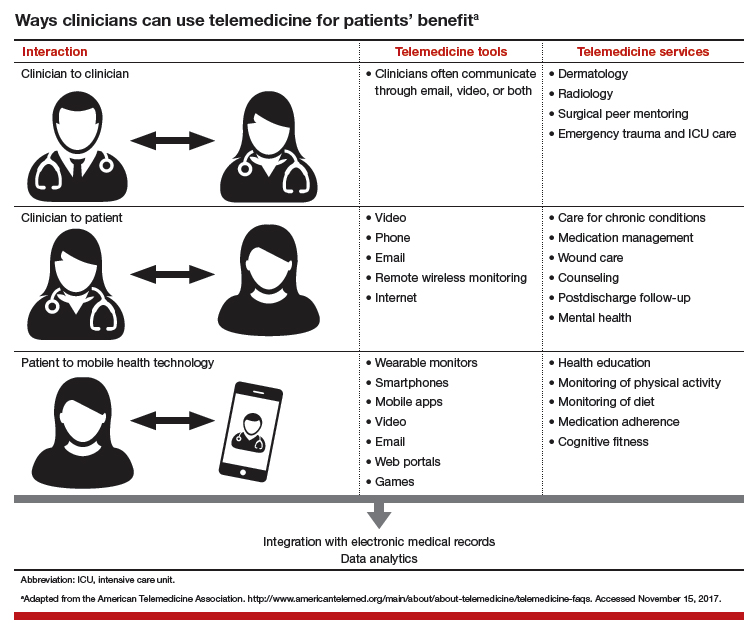

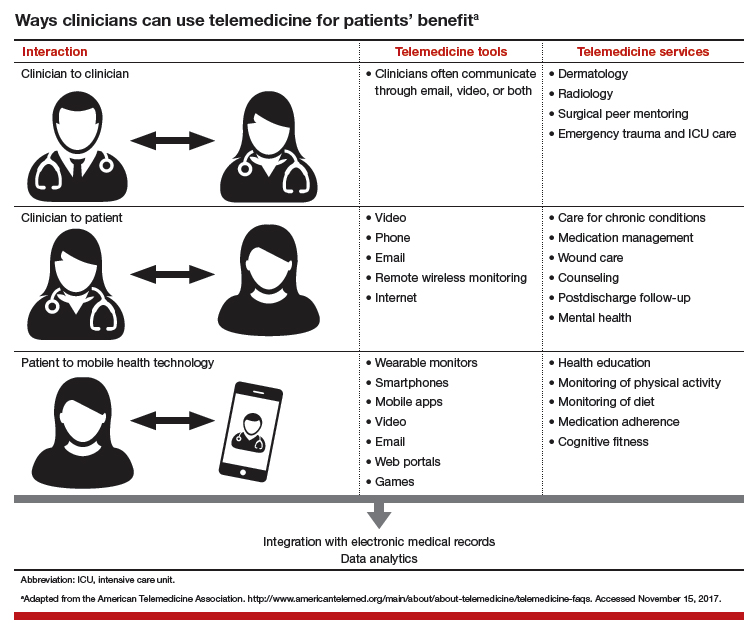

Following up on that new law, ACOG currently is working closely with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the National Rural Health Association (NRHA) on the unique challenges women in rural areas face in accessing maternity and other women’s health care services. In June, Dr. Hollier represented ACOG at the Rural Maternal Health forum, which was convened by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid and sponsored by ACOG, AAFP, and NRHA.4 We are pursuing policies designed to increase the number of ObGyns and other physicians who choose to train in rural areas and increase the clinical use of telehealth to help connect rural physicians and patients with subspecialists in urban areas.

Projects in the works

Congress is ready to do more. Already, 5 ACOG-supported bills have been introduced, including bills that extend women’s Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum (consistent with coverage for babies), support state perinatal quality collaboratives, and more. This interest is augmented by the work of the recently formed congressional Black Maternal Health Caucus, focused on reducing racial disparities in health care. In July, ACOG joined 12 members of Congress in a caucus summit to partner with these important congressional allies.

ACOG is expanding support for these legislative efforts through our work with another important ally, the American Medical Association (AMA). ACOG’s delegation to the 2019 Annual Meeting of the AMA House of Delegates in June scored important policy wins, including AMA support for Medicaid coverage for women 12 months postpartum and improving access to care in rural communities.

There is momentum on Capitol Hill to take action on these important issues, and ACOG’s priority is to ensure that any legislative package complements the important work many ObGyns are already doing to improve maternal health outcomes. ACOG has an important seat at the table and will continue to advocate each and every day for your practices and your patients as Congress deliberates legislative action.

Continue to: Your voice matters...

Your voice matters

Encourage your representatives in the House and the Senate to support ACOG-endorsed legislation and be sure they know the importance of ensuring access to women’s health care in your community. Get involved in advocacy; start by visiting the ACOG advocacy web page (www.acog.org/advocacy). Also note that members of Congress are back in their home states during seasonal breaks and many hold town halls and constituent meetings. The health of moms and babies is always an important issue, and you are the expert.

ACOG’s commitment to ensuring healthy moms and babies, and ensuring that our members can continue providing high-quality care, runs through everything we do.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks ACOG former Vice President for Health Policy Barbara Levy, MD, ACOG Senior Director Jeanne Mahoney, and ACOG Federal Affairs Director Rachel Tetlow for their helpful review and comments.

Real progress was achieved in 2018 in the effort to reduce the US maternal mortality rate, the highest of any developed nation and where women of color are 3 to 4 times more likely than others to die of childbirth-related causes. Importantly, the United States is the only nation other than Afghanistan and Sudan where the rate is rising.1

In May 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a Vital Signs document focused on preventable maternal deaths.2 It affirmed that about 60% of the 700 pregnancy-related deaths that occur annually in the United States are preventable, and it provided important information on when and why these deaths occur.

Among the CDC findings, about:

- one-third of deaths (31%) occurred during pregnancy (before delivery)

- one-third (36%) occurred at delivery or in the week after

- one-third (33%) occurred 1 week to 1 year postpartum.

In addition, the CDC highlighted that:

- Heart disease and stroke caused more than 1 in 3 deaths (34%). Infections and severe bleeding were other leading causes of death.

- Black and American Indian/Alaska Native women were about 3 times as likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause as white women.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Lisa Hollier, MD, MPH (2018–2019), fully embraced the challenge and responsibility of meaningfully improving health care for every mom. In this article, I review some of the critical steps taken in 2018 and preview ACOG’s continued commitment for 2019 and beyond.

Efforts succeed: Bills are now laws of the land

ACOG and our partner organizations, including the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the March of Dimes, have long recognized the value of state-based maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) in slowing and reversing the rate of maternal mortality. An MMRC brings together local experts to examine the causes of maternal deaths—not to find fault, but to find ways to prevent future deaths. With the right framework and support, MMRCs already are providing us with data and driving policy recommendations.

Supporting MMRCs in all states. With this in mind, ACOG helped pass and push to enactment HR 1318, the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018 (Public Law No. 115-344), a bipartisan bill designed to help develop and provide support for MMRCs in every state. The bill was introduced in the US House of Representatives by Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-WA) and Rep. Diana DeGette (D-CO) and in the US Senate by Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND) and Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV). ACOG Fellow and US Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX), also was instrumental in the bill’s success. The CDC is actively working toward implementation of this law, and grantees are expected to be announced by the end of September.

Continue to: In addition, ACOG worked with Congress...

In addition, ACOG worked with Congress to secure $50 million in federal funding to reduce maternal mortality, allocated thusly:

- $12 million to support state MMRCs

- $3 million to support the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health

- $23 million for State Maternal Health Innovation Program grants

- $12 million to address maternal mortality in the Healthy Start program.

As these federal congressional initiatives worked their way into law, the states actively supported MMRCs as well. As of this writing, only 3 states—North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming—have not yet developed an MMRC.3

Filling the gaps in ObGyn care. Another key ACOG-sponsored bill signed into law will help bring more ObGyns into shortage areas. Sponsored by Rep. Burgess, Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-CA), and Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA) and by Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) and Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), the Improving Access to Maternity Care Act (Public Law No. 115-320) requires the Department of Health and Human Services to identify maternity health professional target areas for use by the National Health Service Corps to bring ObGyns to where they are most needed.

Following up on that new law, ACOG currently is working closely with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the National Rural Health Association (NRHA) on the unique challenges women in rural areas face in accessing maternity and other women’s health care services. In June, Dr. Hollier represented ACOG at the Rural Maternal Health forum, which was convened by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid and sponsored by ACOG, AAFP, and NRHA.4 We are pursuing policies designed to increase the number of ObGyns and other physicians who choose to train in rural areas and increase the clinical use of telehealth to help connect rural physicians and patients with subspecialists in urban areas.

Projects in the works

Congress is ready to do more. Already, 5 ACOG-supported bills have been introduced, including bills that extend women’s Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum (consistent with coverage for babies), support state perinatal quality collaboratives, and more. This interest is augmented by the work of the recently formed congressional Black Maternal Health Caucus, focused on reducing racial disparities in health care. In July, ACOG joined 12 members of Congress in a caucus summit to partner with these important congressional allies.

ACOG is expanding support for these legislative efforts through our work with another important ally, the American Medical Association (AMA). ACOG’s delegation to the 2019 Annual Meeting of the AMA House of Delegates in June scored important policy wins, including AMA support for Medicaid coverage for women 12 months postpartum and improving access to care in rural communities.

There is momentum on Capitol Hill to take action on these important issues, and ACOG’s priority is to ensure that any legislative package complements the important work many ObGyns are already doing to improve maternal health outcomes. ACOG has an important seat at the table and will continue to advocate each and every day for your practices and your patients as Congress deliberates legislative action.

Continue to: Your voice matters...

Your voice matters

Encourage your representatives in the House and the Senate to support ACOG-endorsed legislation and be sure they know the importance of ensuring access to women’s health care in your community. Get involved in advocacy; start by visiting the ACOG advocacy web page (www.acog.org/advocacy). Also note that members of Congress are back in their home states during seasonal breaks and many hold town halls and constituent meetings. The health of moms and babies is always an important issue, and you are the expert.

ACOG’s commitment to ensuring healthy moms and babies, and ensuring that our members can continue providing high-quality care, runs through everything we do.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks ACOG former Vice President for Health Policy Barbara Levy, MD, ACOG Senior Director Jeanne Mahoney, and ACOG Federal Affairs Director Rachel Tetlow for their helpful review and comments.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women's Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program. https://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-program/. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: pregnancy-related deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/maternal-deaths/index.html. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. State Maternal Mortality Review Committees, PQCs, and AIM. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/Government-Relations-and-Outreach/MMRC_AIM-State-Fact-Sheet_Mar-2019.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. A conversation on maternal health care in rural communities: charting a path to improved access, quality and outcomes. June 12, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/equity-initiatives/rural-health/rural-maternal-health.html. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women's Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program. https://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-program/. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: pregnancy-related deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/maternal-deaths/index.html. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. State Maternal Mortality Review Committees, PQCs, and AIM. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/Government-Relations-and-Outreach/MMRC_AIM-State-Fact-Sheet_Mar-2019.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. A conversation on maternal health care in rural communities: charting a path to improved access, quality and outcomes. June 12, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/equity-initiatives/rural-health/rural-maternal-health.html. Accessed August 19, 2019.

The Affordable Care Act, closing in on a decade

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted on March 23, 2010. Controversies, complaints, and detractors have and continue to abound. But the ACA’s landmark women’s health gains are unmistakable. Contraceptive coverage, maternity coverage, Medicaid coverage of low-income women, coverage for individuals with preexisting conditions, and gender-neutral premiums are now a part of the fabric of our society. For most.

Many physicians and patients—many lawmakers, too—do not remember the serious problems people had with their insurance companies before the ACA. Maternity coverage was usually a free-standing rider to an insurance policy, making it very expensive. Insurance plans did not have to, and often did not, cover contraceptives, and none did without copays or deductibles. Women were routinely denied coverage if they had ever had a cesarean delivery, had once been the victim of domestic violence, or had any one of many common conditions, like diabetes. The many exclusionary conditions are so common, in fact, that one study estimated that around 52 million adults in the United States (27% of those younger than age 65 years) have preexisting conditions that would potentially make them uninsurable without the ACA’s protections.1

Before the ACA, it also was common for women with insurance policies to find their coverage rescinded, often with no explanation, even though they paid their premiums every month. And women with serious medical conditions often saw their coverage ended midway through their course of treatment. That placed their ObGyns in a terrible situation, too.

The insurance industry as a whole was running rough-shod over its customers, and making a lot of money by creatively and routinely denying coverage and payment for care. People were often insured, but not covered. The ACA halted many of these practices, and required insurers to meet high medical loss ratios, guaranteeing that 80% of the premiums’ for individual and small market insurers (and 85% for large insurers) are returned to patients in care payments or even in checks. In fact, nearly $4 billion in premiums have been rebated to insured individuals over the last 7 years under the ACA.2

The commitment of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to women’s health and to our members’ ability to provide the best care has centered on preserving the critical gains of the ACA for women, improving them when we can, and making sure politicians don’t turn back the clock on women’s health. We have been busy.

In this article, we will look at what has happened to these landmark gains and promises of improved women’s health, specifically preexisting condition protections and contraceptive coverage, under a new Administration. What happens when good health care policy and political enmity collide?

Preexisting coverage protections

The 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) defines a preexisting condition exclusionas a “limitation or exclusion of benefits relating to a condition based on the fact that the condition was present before the date of enrollment for the coverage, whether or not any medical advice, diagnosis, care, or treatment was recommended or received before that date.” HIPPA prohibited employer-sponsored health plans from discriminating against individuals through denying them coverage or charging them more based on their or their family members’ health problems. The ACA expanded protections to prohibit the insurance practice of denying coverage altogether to an individual with a preexisting condition.3

Continue to: Under Congress...

Under Congress

Republicans held the majority in both chambers of the 115th Congress (2017–2018), and hoped to use their majority status to get an ACA repeal bill to the Republican President’s desk for speedy enactment. It was not easy, and they were not successful. Four major bills—the American Health Care Act, the Better Care Reconciliation Act, the Health Care Freedom Act, and the Graham-Cassidy Amendment—never made it over the finish line, with some not even making it to a vote. The Health Care Freedom Act was voted down in the Senate 51-49 when Senator John McCain came back from brain surgery to cast his famous thumbs-down vote.4 These bills all would have repealed or hobbled guaranteed issue, community rating, and essential health benefits of the ACA. Of all the legislative attempts to undermine the ACA, only the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) was signed into law, repealing the ACA individual mandate.

Handling by the courts

The TCJA gave ACA opponents their opening in court. Twenty Republican state attorneys general and governors brought suit in February 2018 (Texas v Azar), arguing that because the ACA relies on the mandate, and the mandate has been repealed, the rest of the ACA also should be struck down. A federal district judge agreed, on December 15, 2018, declaring the entire ACA unconstitutional.5

That decision has been limited in its practical effect so far, and maybe it was not altogether unexpected. What was unexpected was that the US Department of Justice (DOJ) refused to defend a federal law, in this case, the ACA. In June 2018, the DOJ declined to defend the individual mandate, as well as guaranteed issue, community rating, the ban on preexisting condition exclusions, and discrimination based on health status in the ACA. The DOJ at that time, however, did not agree with the plaintiffs that without the mandate the entire ACA should be struck down. It said, “There is no reason why the ACA’s particular expansion of Medicaid hinges on the individual mandate.” Later, after the December 15 ruling, the DOJ changed its position and agreed with the judge, in a two-sentence letter to the court, that the ACA should be stricken altogether—shortly after which 3 career DOJ attorneys resigned.6

A legal expert observed: “The DOJ’s decision not to defend the ACA breaks with the Department’s long-standing bipartisan commitment to defend federal laws if reasonable arguments can be made in their defense. Decisions not to defend federal law are exceedingly rare. It seems even rarer to change the government’s position mid-appeal in such a high-profile lawsuit that risks disrupting the entire health care system and health insurance coverage for millions of Americans.”7

Regulatory tactics

What a policy maker cannot do by law, he or she can try to accomplish by regulation. The Administration is using 3 regulatory routes to undercut the ACA preexisting coverage protections and market stability.

Route 1: Short-Term Limited Duration (STLD) plans. These plans were created in the ACA to provide bridge coverage for up to 3 months for individuals in between health insurance plans. These plans do not have to comply with ACA patient protections, can deny coverage for preexisting conditions, and do not cover maternity care. In 2018, the Administration moved to allow these plans to be marketed broadly and renewed for up to 3 years. Because these plans provide less coverage and often come with high deductibles, they can be marketed with lower premiums, skimming off healthier younger people who do not expect to need much care, as well as lower-income families. This destabilizes the market and leaves people insured but not covered, exactly the situation before the ACA. Seven public health and medical groups sued to challenge the Administration’s STLD regulation; the lawsuit is presently pending.

Continue to: Route 2: Association Health Plans (AHPs)...

Route 2: Association Health Plans (AHPs). The Administration also has allowed the sale of AHPs, marketed to small employers and self-employed individuals. These plans also do not have to comply with ACA consumer protections. They often do not cover maternity care or other essential benefits, and can charge women higher premiums for the same insurance. This regulation, too, resulted in litigation and a federal judge enjoined the rule, but the case is now on appeal.

Route 3: ACA Section 1332 waivers. These waivers were created in the ACA to encourage state innovation to increase access to health coverage, under certain guardrails: states must ensure coverage is at least as comprehensive as the Essential Health Benefits; cost sharing protections must be at least as affordable as under the ACA; the plan must cover at least a comparable number of its residents; and the plan must not increase the federal deficit.

The Adminstration has come under fire for approving 1332 waiver plans that do not meet these guardrails, and allow insurers to exclude coverage for individuals with preexisting conditions, as well as skirt other important ACA patient protections. In response, Seema Verma, Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, promised as recently as April 23, that the Administration will not allow any weakening of the ACA preexisting coverage guarantee.8 So far, however, we do not know what action this means, and not surprisingly, House Democrats, now in the majority, are waiting to see those assurances come true. Consistent polling shows that a large majority of Americans, across political parties, think preexisting coverage protections are very important.9

Already, the House passed HR986, to repeal the Administration’s changes to the 1332 waiver rules. The bill won only 4 Republican votes in the House and now waits a Senate vote.

The House is ready to vote on HR1010, which returns the STLD rules to the original ACA version. The Congressional Budget Office has determined that this bill will reduce the federal deficit by $8.9 billion over 10 years, in part by reestablishing a large risk pool. Lower ACA premiums would mean lower federal subsidies and small federal outlays.

Contraceptive coverage

Since 2012, the ACA has required non-grandfathered individual and group health plans to cover, with no copays or deductibles, women’s preventive services, as determined by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). HRSA asked the National Academy of Medicine (the Institute of Medicine [IOM] at the time) to develop these coverage guidelines based on clinical and scientific relevance. The IOM relied heavily on ACOG’s testimony and women’s health guidelines. The guidelines are updated every 5 years, based on extensive review by the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative, led by ACOG. By law and regulation, covered services include:

- well-woman visits

- contraceptive methods and counseling, including all methods approved for women by the FDA

- breast and cervical cancer screening

- counseling for sexually transmitted infections

- counseling and screening for HIV

- screening for gestational diabetes

- breastfeeding support, supplies, and counseling

- screening and counseling for interpersonal and domestic violence.

Continue to: The previous administration offered a narrow exemption...

The previous administration offered a narrow exemption—an accommodation—for churches, religious orders, and integrated auxiliaries (organizations with financial support primarily from churches). That accommodation was expanded in the Supreme Court’s decision in Hobby Lobby, for closely held for-profit organizations that had religious objections to covering some or all contraceptives. Under the accommodation, the entity’s insurer or third-party administrator was responsible for providing contraceptive services to the entity’s plan participants and beneficiaries.

In October 2017, the Trump administration acted to greatly expand the ability of any employer, college or university, individual, or insurer to opt out of the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement. You will read more about this later.

ACOG’s business case for contraception

Early in the Trump Administration, the White House released a statement saying, “Ensuring affordable, accessible, and quality healthcare is critical to improving women’s health and ensuring that it fits their priorities at any stage of life.”10 ACOG could not agree more, and we encouraged the President to accomplish this important goal by protecting the landmark women’s health gains of the ACA. Our call to the President and the US Congress was: “Don’t turn back the clock on women’s health.”

We made a business case for continued contraceptive coverage:

Contraception reduces unintended pregnancies and saves federal dollars.

- Approximately 45% of US pregnancies are unintended.11

- No-copay coverage of contraception has contributed to a dramatic decline in the unintended pregnancy rate in the United States, now at a 30-year low.12

- When cost is not a barrier, women choose more effective forms of contraception, such as intrauterine devices and implants.13

- Unintended pregnancies cost approximately $12.5 billion in government expenditures in 2008.14

- Private health plans spend as much as $4.6 billion annually in costs related to unintended pregnancies.15

Contraception means healthier women and healthier families.

- Under the ACA, the uninsured rate among women ages 18 to 64 almost halved, decreasing from 19.3% to 10.8%.16

- More than 55 million women gained access to preventive services, including contraception, without a copay or a deductible.16

- Women with unintended pregnancies are more likely to delay prenatal care. Infants are at greater risk of birth defects, low birth weight, and poor mental and physical functioning in early childhood.17

Increased access to contraception helps families and improves economic security.

- Women saved $1.4 billion in out-of-pocket costs for contraception in 1 year.18

- Before the ACA, women were spending between 30% and 44% of their total out-of-pocket health costs just on birth control.19

- The ability to plan a pregnancy increases engagement of women in the workforce and improves economic stability for women and their families.20

Administration expands religious exemptions to contraception coverage

Still, on October 6, 2017, the Trump Administration moved to curtail women’s access to and coverage of contraception with the Religious Exemptions and Accommodations for Coverage of Certain Preventive Services under the Affordable Care Act and Moral Exemptions and Accommodations for Coverage of Certain Preventive Services Under the Affordable Care Act. In November 2018, the Administration published a revised rule, to take effect in January 2019.21 The rule immediately was taken to court by more than a dozen states and, 1 month later, was subject to an injunction by the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, blocking the rules from going into effect in those states.

Continue to: The rule vastly expands the Obama Administration’s religious accommodation...

The rule vastly expands the Obama Administration’s religious accommodation to include “nonprofit organizations, small businesses, and individuals that have nonreligious moral convictions opposing services covered by the contraceptive mandate.” The covered entities include21:

- churches, integrated auxiliaries, and religious orders with religious objections

- nonprofit organizations with religious or moral objections

- for-profit entities that are not publicly traded, with religious or moral objections

- for-profit entities that are publicly traded, with religious objections

- other nongovernmental employers with religious objections

- nongovernmental institutions of higher education with religious or moral objections

- individuals with religious or moral objections, with employer sponsored or individual market coverage, where the plan sponsor and/or issuer (as applicable) are willing to offer them a plan omitting contraceptive coverage to which they object

- issuers with religious or moral objections, to the extent they provide coverage to a plan sponsor or individual that is also exempt.

The Administration says women losing coverage can get contraceptives through Title X clinics or other government programs. Of course, many women losing coverage are employed, and earn above the low income (100% of the federal poverty level) eligibility requirement for Title X assistance. To address that, the Administration, through its proposed Title X regulations, broadens the definition of “low income” in that program to include women who lose their contraceptive coverage through the employer-base health insurance plan. This move further limits the ability of the Title X program to adequately care for already-qualified individuals.

The Administration’s rule also relied on major inaccuracies, which ACOG corrected.22 First, ACOG pointed out that, in fact, FDA-approved contraceptive methods are not abortifacients, countering the Administration’s contention that contraception is an abortifacient, and that contraceptives cause abortions or miscarriages. Every FDA-approved contraceptive acts before implantation, does not interfere with a pregnancy, and is not effective after a fertilized egg has implanted successfully in the uterus.23 No credible research supports the false statement that birth control causes miscarriages.24

Second, ACOG offered data proving that increased access to contraception is not associated with increased unsafe sexual behavior or increased sexual activity.25,26 The facts are that:

- The percentage of teens who are having sex has declined significantly, by 14% for female and 22% for male teenagers, over the past 25 years.27

- More women are using contraception the first time they have sex. Young women who do not use birth control at first sexual intercourse are twice as likely to become teen mothers.28

- Increased access to and use of contraception has contributed to a dramatic decline in rates of adolescent pregnancy.29

- School-based health centers that provide access to contraceptives are proven to increase use of contraceptives by already sexually active students, not to increase onset of sexual activity.30,31

Third, ACOG made clear the benefits to women’s health from contraception. ACOG asserted: As with any medication, certain types of contraception may be contraindicated for patients with certain medical conditions, including high blood pressure, lupus, or a history of breast cancer.32,33 For these and many other reasons, access to the full range of FDA-approved contraception, with no cost sharing or other barriers, is critical to women’s health. Regarding VTE, the risk among oral contraceptive users is very low. In fact, it is much lower than the risk of VTE during pregnancy or in the immediate postpartum period.34

Continue to: Regarding breast cancer: there is no proven increased risk...

Regarding breast cancer: there is no proven increased risk of breast cancer among contraceptive users, particularly among those younger than age 40. For women older than 40, health care providers must consider both the risks of becoming pregnant at advanced reproductive age and the risks of continuing contraception use until menopause.35

ACOG has 2 clear messages for politicians

ACOG has remained steadfast in its opposition to the Administration’s proposals to block access to contraception. ACOG expressed its strong opposition to political interference in medical care, saying “Every woman, regardless of her insurer, employer, state of residence, or income, should have affordable, seamless access to the right form of contraception for her, free from interference from her employer or politicians.”22

ACOG’s voice has been joined by 5 other major medical associations—American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Psychiatric Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American Osteopathic Association—together representing more than 560,000 physicians and medical students, in urging the Administration to immediately withdraw its proposals. This broad coalition unequivocally stated36:

Contraception is an integral part of preventive care and a medical necessity for women during approximately 30 years of their lives. Access to no-copay contraception leads to healthier women and families. Changes to our healthcare system come with very high stakes – impacting tens of millions of our patients. Access to contraception allows women to achieve, lead and reach their full potentials, becoming key drivers of our Nation’s economic success. These rules would create a new standard whereby employers can deny their employees coverage, based on their own moral objections. This interferes in the personal health care decisions of our patients, and inappropriately inserts a patient’s employer into the physician-patient relationship. In addition, these rules open the door to moral exemptions for other essential health care, including vaccinations.

These are challenging days for women’s health policy and legislation federally, and in many states. ACOG has two clear messages for politicians: Don’t turn back the clock on women’s health, and stay out of our exam rooms.

- Claxton G, Cox C, Damico A, et al. Pre-existing conditions and medical underwriting in the individual insurance market prior to the ACA. Kaiser Family Foundation website. Published December 12, 2016. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- Norris L. Billions in ACA rebates show 80/20 rule’s impact. HealthInsurance.org website. Published May 10, 2019. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Preexisting condition exclusions, lifetime and annual limits, rescissions, and patient protections. Regulations.gov website. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- Jost T. The Senate’s Health Care Freedom Act. Health Affairs website. Updated July 28, 2017. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- Texas v Azar decision. American Medical Association website. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- Keith K. DOJ, plaintiffs file in Texas v United States. Health Affairs website. Published May 2 2019. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- John & Rusty Report. Trump Administration asks court to strike down entire ACA. March 26, 2019. https://jrreport.wordandbrown.com/2019/03/26/trump-administration-asks-court-to-strike-down-entire-aca/. Accessed June 29, 2019.

- Speech: Remarks by Administrator Seema Verma at the CMS National Forum on State Relief and Empowerment Waivers. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid website. Published April 23, 2019. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- Poll: The ACA’s pre-existing condition protections remain popular with the public, including republicans, as legal challenge looms this week. Kaiser Family Foundation website. Published September 5, 2018. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- Statement from President Donald J. Trump on Women’s Health Week. White House website. Issued May 14, 2017. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008-2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:843-852.

- Insurance coverage of contraception. Guttmacher Institute website. Published August 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Carlin CS, Fertig AR, Dowd BE. Affordable Care Act’s mandate eliminating contraceptive cost sharing influenced choices of women with employer coverage. Health Affairs. 2016;35:1608-1615.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Access to contraception. Committee Opinion No. 615. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:250–255.

- Canestaro W, et al. Implications of employer coverage of contraception: cost-effectiveness analysis of contraception coverage under an employer mandate. Contraception. 2017;95:77-89.

- Simmons A, et al. The Affordable Care Act: Promoting better health for women. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Issue Brief, Department of Health and Human Services. June 14, 2016. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:1809–1823.

- Becker NV, Polsky D. Women saw large decrease in out-of-pocket spending for contraceptives after ACA mandate removed cost sharing. Health Affairs. 2015;34:1204-1211. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- Becker NV, Polsky D. Women saw large decrease in out-of-pocket spending for contraceptives after ACA mandate removed cost sharing. Health Affairs. 2015;34(7).

- Sonfield A, Hasstedt K, Kavanaugh ML, Anderson R. The social and economic benefits of women’s ability to determine whether and when to have children. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2013.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Fact sheet: Final rules on religious and moral exemptions and accommodation for coverage of certain preventive services under the Affordable Care Act. November 7, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Facts are important: Correcting the record on the Administration’s contraceptive coverage roll back rule. October 2017. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Brief for Physicians for Reproductive Health, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists et al. as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, Sebelius v. Hobby Lobby, 573 U.S. XXX. 2014. (No. 13-354).

- Early pregnancy loss. FAQ No. 90. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. August 2015.

- Kirby D. Emerging answers 2007: Research findings on programs to reduce teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2009.

- Meyer JL, Gold MA, Haggerty CL. Advance provision of emergency contraception among adolescent and young adult women: a systematic review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:2-9.

- Martinez GM and Abma JC. Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing of teenagers aged 15–19 in the United States. NCHS Data Brief, 2015, No. 209. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015.

- Martinez GM, Abma JC. Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing of teenagers aged 15-19 in the United States. NCHS Data Brief. July 2015. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Lindberg L, Santelli J, Desai S. Understanding the decline in adolescent fertility in the United States, 2007–2012. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:577-583.

- Minguez M, Santelli JS, Gibson E, et al. Reproductive health impact of a school health center. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:338-344.

- Knopf JA, Finnie RK, Peng Y, et al. Community Preventive Services Task Force. School-based health centers to advance health equity: a Community Guide systematic review. Am J Preventive Med. 2016;51:114-126.

- Progestin-only hormonal birth control: pill and injection. FAQ No. 86. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. July 2014.

- Combined hormonal birth control: pill, patch, and ring. FAQ No. 185. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. July 2014.

- Risk of venous thromboembolism among users of drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive pills. Committee Opinion No. 540. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1239-1242.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(No. RR-4):1–66.

- Letter to President Donald J. Trump. October 6, 2017. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/advocacy/coverage/aca/LT-Group6-President-ContraceptionIFRs-100617.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2019.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted on March 23, 2010. Controversies, complaints, and detractors have and continue to abound. But the ACA’s landmark women’s health gains are unmistakable. Contraceptive coverage, maternity coverage, Medicaid coverage of low-income women, coverage for individuals with preexisting conditions, and gender-neutral premiums are now a part of the fabric of our society. For most.

Many physicians and patients—many lawmakers, too—do not remember the serious problems people had with their insurance companies before the ACA. Maternity coverage was usually a free-standing rider to an insurance policy, making it very expensive. Insurance plans did not have to, and often did not, cover contraceptives, and none did without copays or deductibles. Women were routinely denied coverage if they had ever had a cesarean delivery, had once been the victim of domestic violence, or had any one of many common conditions, like diabetes. The many exclusionary conditions are so common, in fact, that one study estimated that around 52 million adults in the United States (27% of those younger than age 65 years) have preexisting conditions that would potentially make them uninsurable without the ACA’s protections.1

Before the ACA, it also was common for women with insurance policies to find their coverage rescinded, often with no explanation, even though they paid their premiums every month. And women with serious medical conditions often saw their coverage ended midway through their course of treatment. That placed their ObGyns in a terrible situation, too.

The insurance industry as a whole was running rough-shod over its customers, and making a lot of money by creatively and routinely denying coverage and payment for care. People were often insured, but not covered. The ACA halted many of these practices, and required insurers to meet high medical loss ratios, guaranteeing that 80% of the premiums’ for individual and small market insurers (and 85% for large insurers) are returned to patients in care payments or even in checks. In fact, nearly $4 billion in premiums have been rebated to insured individuals over the last 7 years under the ACA.2

The commitment of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to women’s health and to our members’ ability to provide the best care has centered on preserving the critical gains of the ACA for women, improving them when we can, and making sure politicians don’t turn back the clock on women’s health. We have been busy.

In this article, we will look at what has happened to these landmark gains and promises of improved women’s health, specifically preexisting condition protections and contraceptive coverage, under a new Administration. What happens when good health care policy and political enmity collide?

Preexisting coverage protections

The 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) defines a preexisting condition exclusionas a “limitation or exclusion of benefits relating to a condition based on the fact that the condition was present before the date of enrollment for the coverage, whether or not any medical advice, diagnosis, care, or treatment was recommended or received before that date.” HIPPA prohibited employer-sponsored health plans from discriminating against individuals through denying them coverage or charging them more based on their or their family members’ health problems. The ACA expanded protections to prohibit the insurance practice of denying coverage altogether to an individual with a preexisting condition.3

Continue to: Under Congress...

Under Congress

Republicans held the majority in both chambers of the 115th Congress (2017–2018), and hoped to use their majority status to get an ACA repeal bill to the Republican President’s desk for speedy enactment. It was not easy, and they were not successful. Four major bills—the American Health Care Act, the Better Care Reconciliation Act, the Health Care Freedom Act, and the Graham-Cassidy Amendment—never made it over the finish line, with some not even making it to a vote. The Health Care Freedom Act was voted down in the Senate 51-49 when Senator John McCain came back from brain surgery to cast his famous thumbs-down vote.4 These bills all would have repealed or hobbled guaranteed issue, community rating, and essential health benefits of the ACA. Of all the legislative attempts to undermine the ACA, only the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) was signed into law, repealing the ACA individual mandate.

Handling by the courts

The TCJA gave ACA opponents their opening in court. Twenty Republican state attorneys general and governors brought suit in February 2018 (Texas v Azar), arguing that because the ACA relies on the mandate, and the mandate has been repealed, the rest of the ACA also should be struck down. A federal district judge agreed, on December 15, 2018, declaring the entire ACA unconstitutional.5

That decision has been limited in its practical effect so far, and maybe it was not altogether unexpected. What was unexpected was that the US Department of Justice (DOJ) refused to defend a federal law, in this case, the ACA. In June 2018, the DOJ declined to defend the individual mandate, as well as guaranteed issue, community rating, the ban on preexisting condition exclusions, and discrimination based on health status in the ACA. The DOJ at that time, however, did not agree with the plaintiffs that without the mandate the entire ACA should be struck down. It said, “There is no reason why the ACA’s particular expansion of Medicaid hinges on the individual mandate.” Later, after the December 15 ruling, the DOJ changed its position and agreed with the judge, in a two-sentence letter to the court, that the ACA should be stricken altogether—shortly after which 3 career DOJ attorneys resigned.6

A legal expert observed: “The DOJ’s decision not to defend the ACA breaks with the Department’s long-standing bipartisan commitment to defend federal laws if reasonable arguments can be made in their defense. Decisions not to defend federal law are exceedingly rare. It seems even rarer to change the government’s position mid-appeal in such a high-profile lawsuit that risks disrupting the entire health care system and health insurance coverage for millions of Americans.”7

Regulatory tactics

What a policy maker cannot do by law, he or she can try to accomplish by regulation. The Administration is using 3 regulatory routes to undercut the ACA preexisting coverage protections and market stability.

Route 1: Short-Term Limited Duration (STLD) plans. These plans were created in the ACA to provide bridge coverage for up to 3 months for individuals in between health insurance plans. These plans do not have to comply with ACA patient protections, can deny coverage for preexisting conditions, and do not cover maternity care. In 2018, the Administration moved to allow these plans to be marketed broadly and renewed for up to 3 years. Because these plans provide less coverage and often come with high deductibles, they can be marketed with lower premiums, skimming off healthier younger people who do not expect to need much care, as well as lower-income families. This destabilizes the market and leaves people insured but not covered, exactly the situation before the ACA. Seven public health and medical groups sued to challenge the Administration’s STLD regulation; the lawsuit is presently pending.

Continue to: Route 2: Association Health Plans (AHPs)...

Route 2: Association Health Plans (AHPs). The Administration also has allowed the sale of AHPs, marketed to small employers and self-employed individuals. These plans also do not have to comply with ACA consumer protections. They often do not cover maternity care or other essential benefits, and can charge women higher premiums for the same insurance. This regulation, too, resulted in litigation and a federal judge enjoined the rule, but the case is now on appeal.

Route 3: ACA Section 1332 waivers. These waivers were created in the ACA to encourage state innovation to increase access to health coverage, under certain guardrails: states must ensure coverage is at least as comprehensive as the Essential Health Benefits; cost sharing protections must be at least as affordable as under the ACA; the plan must cover at least a comparable number of its residents; and the plan must not increase the federal deficit.

The Adminstration has come under fire for approving 1332 waiver plans that do not meet these guardrails, and allow insurers to exclude coverage for individuals with preexisting conditions, as well as skirt other important ACA patient protections. In response, Seema Verma, Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, promised as recently as April 23, that the Administration will not allow any weakening of the ACA preexisting coverage guarantee.8 So far, however, we do not know what action this means, and not surprisingly, House Democrats, now in the majority, are waiting to see those assurances come true. Consistent polling shows that a large majority of Americans, across political parties, think preexisting coverage protections are very important.9

Already, the House passed HR986, to repeal the Administration’s changes to the 1332 waiver rules. The bill won only 4 Republican votes in the House and now waits a Senate vote.

The House is ready to vote on HR1010, which returns the STLD rules to the original ACA version. The Congressional Budget Office has determined that this bill will reduce the federal deficit by $8.9 billion over 10 years, in part by reestablishing a large risk pool. Lower ACA premiums would mean lower federal subsidies and small federal outlays.

Contraceptive coverage

Since 2012, the ACA has required non-grandfathered individual and group health plans to cover, with no copays or deductibles, women’s preventive services, as determined by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). HRSA asked the National Academy of Medicine (the Institute of Medicine [IOM] at the time) to develop these coverage guidelines based on clinical and scientific relevance. The IOM relied heavily on ACOG’s testimony and women’s health guidelines. The guidelines are updated every 5 years, based on extensive review by the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative, led by ACOG. By law and regulation, covered services include:

- well-woman visits

- contraceptive methods and counseling, including all methods approved for women by the FDA

- breast and cervical cancer screening

- counseling for sexually transmitted infections

- counseling and screening for HIV

- screening for gestational diabetes

- breastfeeding support, supplies, and counseling

- screening and counseling for interpersonal and domestic violence.

Continue to: The previous administration offered a narrow exemption...

The previous administration offered a narrow exemption—an accommodation—for churches, religious orders, and integrated auxiliaries (organizations with financial support primarily from churches). That accommodation was expanded in the Supreme Court’s decision in Hobby Lobby, for closely held for-profit organizations that had religious objections to covering some or all contraceptives. Under the accommodation, the entity’s insurer or third-party administrator was responsible for providing contraceptive services to the entity’s plan participants and beneficiaries.

In October 2017, the Trump administration acted to greatly expand the ability of any employer, college or university, individual, or insurer to opt out of the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement. You will read more about this later.

ACOG’s business case for contraception

Early in the Trump Administration, the White House released a statement saying, “Ensuring affordable, accessible, and quality healthcare is critical to improving women’s health and ensuring that it fits their priorities at any stage of life.”10 ACOG could not agree more, and we encouraged the President to accomplish this important goal by protecting the landmark women’s health gains of the ACA. Our call to the President and the US Congress was: “Don’t turn back the clock on women’s health.”

We made a business case for continued contraceptive coverage:

Contraception reduces unintended pregnancies and saves federal dollars.

- Approximately 45% of US pregnancies are unintended.11

- No-copay coverage of contraception has contributed to a dramatic decline in the unintended pregnancy rate in the United States, now at a 30-year low.12

- When cost is not a barrier, women choose more effective forms of contraception, such as intrauterine devices and implants.13

- Unintended pregnancies cost approximately $12.5 billion in government expenditures in 2008.14

- Private health plans spend as much as $4.6 billion annually in costs related to unintended pregnancies.15

Contraception means healthier women and healthier families.

- Under the ACA, the uninsured rate among women ages 18 to 64 almost halved, decreasing from 19.3% to 10.8%.16

- More than 55 million women gained access to preventive services, including contraception, without a copay or a deductible.16

- Women with unintended pregnancies are more likely to delay prenatal care. Infants are at greater risk of birth defects, low birth weight, and poor mental and physical functioning in early childhood.17

Increased access to contraception helps families and improves economic security.

- Women saved $1.4 billion in out-of-pocket costs for contraception in 1 year.18

- Before the ACA, women were spending between 30% and 44% of their total out-of-pocket health costs just on birth control.19

- The ability to plan a pregnancy increases engagement of women in the workforce and improves economic stability for women and their families.20

Administration expands religious exemptions to contraception coverage

Still, on October 6, 2017, the Trump Administration moved to curtail women’s access to and coverage of contraception with the Religious Exemptions and Accommodations for Coverage of Certain Preventive Services under the Affordable Care Act and Moral Exemptions and Accommodations for Coverage of Certain Preventive Services Under the Affordable Care Act. In November 2018, the Administration published a revised rule, to take effect in January 2019.21 The rule immediately was taken to court by more than a dozen states and, 1 month later, was subject to an injunction by the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, blocking the rules from going into effect in those states.

Continue to: The rule vastly expands the Obama Administration’s religious accommodation...

The rule vastly expands the Obama Administration’s religious accommodation to include “nonprofit organizations, small businesses, and individuals that have nonreligious moral convictions opposing services covered by the contraceptive mandate.” The covered entities include21:

- churches, integrated auxiliaries, and religious orders with religious objections

- nonprofit organizations with religious or moral objections

- for-profit entities that are not publicly traded, with religious or moral objections

- for-profit entities that are publicly traded, with religious objections

- other nongovernmental employers with religious objections

- nongovernmental institutions of higher education with religious or moral objections

- individuals with religious or moral objections, with employer sponsored or individual market coverage, where the plan sponsor and/or issuer (as applicable) are willing to offer them a plan omitting contraceptive coverage to which they object

- issuers with religious or moral objections, to the extent they provide coverage to a plan sponsor or individual that is also exempt.

The Administration says women losing coverage can get contraceptives through Title X clinics or other government programs. Of course, many women losing coverage are employed, and earn above the low income (100% of the federal poverty level) eligibility requirement for Title X assistance. To address that, the Administration, through its proposed Title X regulations, broadens the definition of “low income” in that program to include women who lose their contraceptive coverage through the employer-base health insurance plan. This move further limits the ability of the Title X program to adequately care for already-qualified individuals.

The Administration’s rule also relied on major inaccuracies, which ACOG corrected.22 First, ACOG pointed out that, in fact, FDA-approved contraceptive methods are not abortifacients, countering the Administration’s contention that contraception is an abortifacient, and that contraceptives cause abortions or miscarriages. Every FDA-approved contraceptive acts before implantation, does not interfere with a pregnancy, and is not effective after a fertilized egg has implanted successfully in the uterus.23 No credible research supports the false statement that birth control causes miscarriages.24

Second, ACOG offered data proving that increased access to contraception is not associated with increased unsafe sexual behavior or increased sexual activity.25,26 The facts are that:

- The percentage of teens who are having sex has declined significantly, by 14% for female and 22% for male teenagers, over the past 25 years.27

- More women are using contraception the first time they have sex. Young women who do not use birth control at first sexual intercourse are twice as likely to become teen mothers.28

- Increased access to and use of contraception has contributed to a dramatic decline in rates of adolescent pregnancy.29

- School-based health centers that provide access to contraceptives are proven to increase use of contraceptives by already sexually active students, not to increase onset of sexual activity.30,31

Third, ACOG made clear the benefits to women’s health from contraception. ACOG asserted: As with any medication, certain types of contraception may be contraindicated for patients with certain medical conditions, including high blood pressure, lupus, or a history of breast cancer.32,33 For these and many other reasons, access to the full range of FDA-approved contraception, with no cost sharing or other barriers, is critical to women’s health. Regarding VTE, the risk among oral contraceptive users is very low. In fact, it is much lower than the risk of VTE during pregnancy or in the immediate postpartum period.34

Continue to: Regarding breast cancer: there is no proven increased risk...

Regarding breast cancer: there is no proven increased risk of breast cancer among contraceptive users, particularly among those younger than age 40. For women older than 40, health care providers must consider both the risks of becoming pregnant at advanced reproductive age and the risks of continuing contraception use until menopause.35

ACOG has 2 clear messages for politicians

ACOG has remained steadfast in its opposition to the Administration’s proposals to block access to contraception. ACOG expressed its strong opposition to political interference in medical care, saying “Every woman, regardless of her insurer, employer, state of residence, or income, should have affordable, seamless access to the right form of contraception for her, free from interference from her employer or politicians.”22

ACOG’s voice has been joined by 5 other major medical associations—American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Psychiatric Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American Osteopathic Association—together representing more than 560,000 physicians and medical students, in urging the Administration to immediately withdraw its proposals. This broad coalition unequivocally stated36:

Contraception is an integral part of preventive care and a medical necessity for women during approximately 30 years of their lives. Access to no-copay contraception leads to healthier women and families. Changes to our healthcare system come with very high stakes – impacting tens of millions of our patients. Access to contraception allows women to achieve, lead and reach their full potentials, becoming key drivers of our Nation’s economic success. These rules would create a new standard whereby employers can deny their employees coverage, based on their own moral objections. This interferes in the personal health care decisions of our patients, and inappropriately inserts a patient’s employer into the physician-patient relationship. In addition, these rules open the door to moral exemptions for other essential health care, including vaccinations.

These are challenging days for women’s health policy and legislation federally, and in many states. ACOG has two clear messages for politicians: Don’t turn back the clock on women’s health, and stay out of our exam rooms.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted on March 23, 2010. Controversies, complaints, and detractors have and continue to abound. But the ACA’s landmark women’s health gains are unmistakable. Contraceptive coverage, maternity coverage, Medicaid coverage of low-income women, coverage for individuals with preexisting conditions, and gender-neutral premiums are now a part of the fabric of our society. For most.

Many physicians and patients—many lawmakers, too—do not remember the serious problems people had with their insurance companies before the ACA. Maternity coverage was usually a free-standing rider to an insurance policy, making it very expensive. Insurance plans did not have to, and often did not, cover contraceptives, and none did without copays or deductibles. Women were routinely denied coverage if they had ever had a cesarean delivery, had once been the victim of domestic violence, or had any one of many common conditions, like diabetes. The many exclusionary conditions are so common, in fact, that one study estimated that around 52 million adults in the United States (27% of those younger than age 65 years) have preexisting conditions that would potentially make them uninsurable without the ACA’s protections.1

Before the ACA, it also was common for women with insurance policies to find their coverage rescinded, often with no explanation, even though they paid their premiums every month. And women with serious medical conditions often saw their coverage ended midway through their course of treatment. That placed their ObGyns in a terrible situation, too.

The insurance industry as a whole was running rough-shod over its customers, and making a lot of money by creatively and routinely denying coverage and payment for care. People were often insured, but not covered. The ACA halted many of these practices, and required insurers to meet high medical loss ratios, guaranteeing that 80% of the premiums’ for individual and small market insurers (and 85% for large insurers) are returned to patients in care payments or even in checks. In fact, nearly $4 billion in premiums have been rebated to insured individuals over the last 7 years under the ACA.2

The commitment of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to women’s health and to our members’ ability to provide the best care has centered on preserving the critical gains of the ACA for women, improving them when we can, and making sure politicians don’t turn back the clock on women’s health. We have been busy.

In this article, we will look at what has happened to these landmark gains and promises of improved women’s health, specifically preexisting condition protections and contraceptive coverage, under a new Administration. What happens when good health care policy and political enmity collide?

Preexisting coverage protections

The 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) defines a preexisting condition exclusionas a “limitation or exclusion of benefits relating to a condition based on the fact that the condition was present before the date of enrollment for the coverage, whether or not any medical advice, diagnosis, care, or treatment was recommended or received before that date.” HIPPA prohibited employer-sponsored health plans from discriminating against individuals through denying them coverage or charging them more based on their or their family members’ health problems. The ACA expanded protections to prohibit the insurance practice of denying coverage altogether to an individual with a preexisting condition.3

Continue to: Under Congress...

Under Congress

Republicans held the majority in both chambers of the 115th Congress (2017–2018), and hoped to use their majority status to get an ACA repeal bill to the Republican President’s desk for speedy enactment. It was not easy, and they were not successful. Four major bills—the American Health Care Act, the Better Care Reconciliation Act, the Health Care Freedom Act, and the Graham-Cassidy Amendment—never made it over the finish line, with some not even making it to a vote. The Health Care Freedom Act was voted down in the Senate 51-49 when Senator John McCain came back from brain surgery to cast his famous thumbs-down vote.4 These bills all would have repealed or hobbled guaranteed issue, community rating, and essential health benefits of the ACA. Of all the legislative attempts to undermine the ACA, only the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) was signed into law, repealing the ACA individual mandate.

Handling by the courts

The TCJA gave ACA opponents their opening in court. Twenty Republican state attorneys general and governors brought suit in February 2018 (Texas v Azar), arguing that because the ACA relies on the mandate, and the mandate has been repealed, the rest of the ACA also should be struck down. A federal district judge agreed, on December 15, 2018, declaring the entire ACA unconstitutional.5

That decision has been limited in its practical effect so far, and maybe it was not altogether unexpected. What was unexpected was that the US Department of Justice (DOJ) refused to defend a federal law, in this case, the ACA. In June 2018, the DOJ declined to defend the individual mandate, as well as guaranteed issue, community rating, the ban on preexisting condition exclusions, and discrimination based on health status in the ACA. The DOJ at that time, however, did not agree with the plaintiffs that without the mandate the entire ACA should be struck down. It said, “There is no reason why the ACA’s particular expansion of Medicaid hinges on the individual mandate.” Later, after the December 15 ruling, the DOJ changed its position and agreed with the judge, in a two-sentence letter to the court, that the ACA should be stricken altogether—shortly after which 3 career DOJ attorneys resigned.6