User login

The well-woman visit comes of age: What it offers, how we got here

When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in 2010, it represented an intended shift from reactive medicine, with its focus on acute and urgent needs, to a model focused on disease prevention.

OBG Management readers know about the important women’s health services ensured by the ACA, including well-woman care, as well as the key role played by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in winning this coverage. ACOG worked closely with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to help define this set of services. And the ACA ensured that women have access to these services, often without copays and deductibles.

ACOG and the National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) work closely on many issues. At first independently and then together, the 2 organizations set out to explore some fundamental issues:

- How does a woman experience the new well-woman benefit when she visits her doctor?

- Does she receive a consistent care set?

- Do some patients have copays while patients in other clinics do not for the same services?

- What does well-woman care mean from one doctor to another, from an ObGyn to an internist to a family physician?

This article explores these issues.

2 initiatives focused on components of women’s health care

During her tenure as president of ACOG, Jeanne Conry, MD, PhD, decided to tackle clinical issues associated with well-woman care. She convened a Well-Woman Task Force, led by Haywood Brown, MD, and included the NWLC among other partner organizations (TABLE).

Table. Partipating organizations of the ACOG Well-Woman Task Force

• American Academy of Family Physicians

• American Academy of Pediatrics

• American Academy of Physician Assistants

• American College of Nurse–Midwives

• American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists

• Association of Reproductive Health Professionals

• Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses

• National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health

• National Medical Association

• National Women’s Law Center

• Planned Parenthood Federation of America

• Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine

• Society of Academic Specialists in General Obstetrics and Gynecology

• Society of Gynecologic Oncology

The NWLC and Brigham and Women’s Hospital also partnered with ACOG and others to help ensure a consistent patient experience. These 2 closely related initiatives were designed to work together to help patients and physicians understand and benefit from new coverage under the ACA.

1. How does a woman experience well-woman care?

Experts associated with these 2 initiatives recognized that well-woman care includes attention to the history, physical examination, counseling, and screening intended to maintain physical, mental, and social wellbeing and general health throughout a woman’s lifespan. Experts also recognized that the ACA guarantees coverage of at least one annual well-woman visit, although not all of the recommended components necessarily would be performed at the same visit or by the same provider.

For many women who have gained insurance coverage under the ACA, the well-woman visit represents their entry into the insured health care system. These women may have limited understanding of the services they should receive during this visit.

To address this issue, the NWLC invited ACOG to participate in its initiative with Brigham and Women’s Hospital to understand the well-woman visit from the patient’s point of view. This effort yielded patient education materials in English and Spanish that help women understand:

- that their health insurance now covers a well-woman visit

- what care is included in that visit

- that there is no deductible or copay for this visit

- how to prepare for this visit

- what questions to ask during the visit.

These materials help women understand that the purpose of the well-woman visit is to provide them with a chance to:

- “receive care and counseling that is appropriate, based on age, cognitive development, and life experience

- review their current health and risks to their health with their health care professional

- ask any questions they may have about their health or risk factors

- talk about what they can do to prevent future health problems

- build a trusting relationship with their health care provider, with an emphasis on confidentiality

- receive appropriate preventive screenings and immunizations and make sure they know which screenings and immunizations they should receive in the future

- review their reproductive plan and contraceptive choices.”1

The materials also advise patients that they may be asked about:

- current health concerns

- current medications, both prescription and over the counter

- family history on both the mother’s and father’s sides

- life management, including family relationships, work, and stress

- substance use habits, including alcohol and tobacco

- sexual activity

- eating habits and physical activity

- past reproductive health experience and any pregnancy complications

- any memory problems (older women)

- screening for depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and interpersonal violence.

To view some of these materials, visit http://www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/final_well-womanbrochure.pdf.

2. Does each woman receive consistent well-woman care?

ACOG’s Well-Woman Task Force was shaped by an awareness that many medical societies and government agencies provide recommendations and guidelines about the basic elements of women’s health. While these recommendations and guidelines all may be based on evidence and expert opinion, the recommendations vary. A goal of the task force was to work with providers across the women’s health spectrum to find consensus and provide guidance to women and clinicians with age-appropriate recommendations for a well-woman visit.

In the fall of 2015, the task force’s findings were published in an article entitled “Components of the well-woman visit” in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology.2 Those findings outline a core set of well-woman care practices across a woman’s lifespan, from adolescence through the reproductive years and into maturity, and they are usable by any provider who cares for adolescent girls or women.

ACOG has summarized its well-woman recommendations, by age, on its website,3 at http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Well-Woman-Recommendations.

3. Do all women have a copay for the well-woman visit?

Because research has revealed that any type of copay or deductible for preventive care significantly lessens the likelihood that patients will seek out such care, the ACA sought to make basic preventive care available without cost sharing.4

The US Department of Health and Human Services notes that: “The Affordable Care Act requires most health plans to cover recommended preventive services without cost sharing. In 2011 and 2012, 71 million Americans with private health insurance gained access to preventive services with no cost sharing because of the law.”4

Grandfathered plans (those created or sold before March 23, 2010) are exempt from this requirement, as are Medicare, TRICARE, and traditional Medicaid plans.

4. What does well-woman care mean from one doctor to another?

Under the ACA, well-woman care can be provided by a “wide range of providers, including family physicians, internists, nurse–midwives, nurse practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, pediatricians, and physician assistants,” depending on the age of the patient, her particular needs and preferences, and access to health services.2

The ACOG Well-Woman Task Force “focused on delineating the well-woman visit throughout the lifespan, across all providers and health plans.”2

In determining the components of well-woman care, ACOG’s task force compiled existing guidelines from many sources, including the Department of Health and Human Services, the IOM, the US Preventive Services Task Force, and each member organization.

Members categorized guidelines as:

- single source (eg, abdominal examination)

- no agreement (breast cancer/mammography screening)

- limited agreement (pelvic examination)

- general agreement (hypertension, osteoporosis)

- sound agreement (screening for sexually transmitted infections)

The task force also agreed that final recommendations would rely on evidence-based guidelines, evidence-informed guidelines, and uniform expert agreement. Recommendations were considered “strong” if they relied primarily on evidence-based or evidence-informed guidelines and “qualified” if they relied primarily on expert consensus.

Guidelines were further separated into age bands:

- adolescents (13–18 years)

- reproductive-aged women (19–45 years)

- mature women (46–64 years)

- women older than 64 years.

The task force recommended that, during the well-woman visit, health care professionals educate patients about:

- healthy eating habits and maintenance of healthy weight

- exercise and physical activity

- seat belt use

- risk factors for certain types of cancer

- heart health

- breast health

- bone health

- safer sex practices and prevention of sexually transmitted infections

- healthy interpersonal relationships

- prevention and management of chronic disease

- resources for the patient (online, written, community, patient groups)

- medication use

- fall prevention.

Health care providers also should counsel patients regarding:

- recommended preventive screenings and immunizations

- any concerns about mood, such as prolonged periods of sadness, a failure to enjoy what they usually find pleasant, or anxiety or irritability that seems out of proportion to events

- what to expect in terms of effects on mood and anxiety at reproductive life transitions, including menarche, pregnancy, the postpartum period, and perimenopause

- body image issues

- what to expect in terms of the menstrual cycle during perimenopause and menopause

- reproductive health or fertility concerns

- reproductive life planning (contraception appropriate for life stage, reproductive plans, and risk factors, including risk factors for breast and ovarian cancer and cardiovascular disease)

- pregnancy planning, including attaining and maintaining a healthy weight and managing any chronic conditions before or during pregnancy

- what to expect during menopause, including signs and symptoms and options for addressing symptoms (midlife and older women)

- symptoms of cardiovascular disease

- urinary incontinence.

The task force acknowledged that not all of these recommendations can be carried out at a single well-woman visit or by a single provider.

See, again, ACOG’s specific well-woman recommendations, by age range, at http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Well-Woman-Recommendations.3

How to winnow a long list of recommendations to determine the most pressing issues for a specific patient

In an editorial accompanying the ACOG Well-Woman Task Force report, entitled “Re-envisioning the annual well-woman visit: the task forward,” George F. Sawaya, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, devised a plan to determine the most pressing well-woman needs for a specific patient.1 He chose as an example a 41-year-old sexually active woman who does not smoke.

While Dr. Sawaya praised the Well-Woman Task Force recommendations for their “comprehensive scope,” he also noted that the sheer number of recommendations might be “overwhelming and difficult to navigate.”1 One tool for winnowing the recommendations comes from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which offers an Electronic Preventive Services Selector (http://epss.ahrq.gov/PDA/index.jsp), available both online and as a smartphone app. Once the clinician plugs in the patient’s age and a few risk factors, the tool generates a list of recommended preventive services. This list of services has been evaluated by the US Preventive Services Task Force, with each recommendation graded “A” through “D,” based on benefits versus harms.

Back to that 41-year-old sexually active woman: Using the Electronic Preventive Services Selector, a list of as many as 20 grade A and B recommendations would be generated. However, only 3 of them would be grade A (screening for cervical cancer, HIV, and high blood pressure). An additional 2 grade B recommendations might apply to an average-risk patient such as this: screening for alcohol misuse and depression. All 5 services fall within the Well-Woman Task Force’s recommendations. They also have “good face validity with clinicians as being important, so it seems reasonable that these be prioritized above the others, at least at the first visit,” Dr. Sawaya says.1

Clinicians can use a similar strategy for patients of various ages and risk factors.

Reference

1. Sawaya GF. Re-envisioning the annual well-woman visit: the task forward [editorial]. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):695–696.

The bottom line

By defining and implementing the foundational elements of women’s health, we can improve care for all women and ensure, as Dr. Conry emphasized during her tenure as ACOG president, “that every woman gets the care she needs, every time.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- National Women’s Law Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Your Guide to Well-Woman Visits. http://www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/final_well-womanbrochure.pdf. Accessed December 8, 2015.

- Conry JA, Brown H. Well-Woman Task Force: Components of the well-woman visit. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):697–701.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Well-Woman Recommendations. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Well-Woman-Recommendations. Accessed December 4, 2015.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Affordable Care Act Rules on Expanding Access to Preventive Services for Women. http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts-and-features/fact-sheets/aca-rules-on-expanding-access-to-preventive-services-for-women/index.html. Updated June 28, 2013. Accessed December 4, 2015.

When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in 2010, it represented an intended shift from reactive medicine, with its focus on acute and urgent needs, to a model focused on disease prevention.

OBG Management readers know about the important women’s health services ensured by the ACA, including well-woman care, as well as the key role played by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in winning this coverage. ACOG worked closely with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to help define this set of services. And the ACA ensured that women have access to these services, often without copays and deductibles.

ACOG and the National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) work closely on many issues. At first independently and then together, the 2 organizations set out to explore some fundamental issues:

- How does a woman experience the new well-woman benefit when she visits her doctor?

- Does she receive a consistent care set?

- Do some patients have copays while patients in other clinics do not for the same services?

- What does well-woman care mean from one doctor to another, from an ObGyn to an internist to a family physician?

This article explores these issues.

2 initiatives focused on components of women’s health care

During her tenure as president of ACOG, Jeanne Conry, MD, PhD, decided to tackle clinical issues associated with well-woman care. She convened a Well-Woman Task Force, led by Haywood Brown, MD, and included the NWLC among other partner organizations (TABLE).

Table. Partipating organizations of the ACOG Well-Woman Task Force

• American Academy of Family Physicians

• American Academy of Pediatrics

• American Academy of Physician Assistants

• American College of Nurse–Midwives

• American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists

• Association of Reproductive Health Professionals

• Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses

• National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health

• National Medical Association

• National Women’s Law Center

• Planned Parenthood Federation of America

• Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine

• Society of Academic Specialists in General Obstetrics and Gynecology

• Society of Gynecologic Oncology

The NWLC and Brigham and Women’s Hospital also partnered with ACOG and others to help ensure a consistent patient experience. These 2 closely related initiatives were designed to work together to help patients and physicians understand and benefit from new coverage under the ACA.

1. How does a woman experience well-woman care?

Experts associated with these 2 initiatives recognized that well-woman care includes attention to the history, physical examination, counseling, and screening intended to maintain physical, mental, and social wellbeing and general health throughout a woman’s lifespan. Experts also recognized that the ACA guarantees coverage of at least one annual well-woman visit, although not all of the recommended components necessarily would be performed at the same visit or by the same provider.

For many women who have gained insurance coverage under the ACA, the well-woman visit represents their entry into the insured health care system. These women may have limited understanding of the services they should receive during this visit.

To address this issue, the NWLC invited ACOG to participate in its initiative with Brigham and Women’s Hospital to understand the well-woman visit from the patient’s point of view. This effort yielded patient education materials in English and Spanish that help women understand:

- that their health insurance now covers a well-woman visit

- what care is included in that visit

- that there is no deductible or copay for this visit

- how to prepare for this visit

- what questions to ask during the visit.

These materials help women understand that the purpose of the well-woman visit is to provide them with a chance to:

- “receive care and counseling that is appropriate, based on age, cognitive development, and life experience

- review their current health and risks to their health with their health care professional

- ask any questions they may have about their health or risk factors

- talk about what they can do to prevent future health problems

- build a trusting relationship with their health care provider, with an emphasis on confidentiality

- receive appropriate preventive screenings and immunizations and make sure they know which screenings and immunizations they should receive in the future

- review their reproductive plan and contraceptive choices.”1

The materials also advise patients that they may be asked about:

- current health concerns

- current medications, both prescription and over the counter

- family history on both the mother’s and father’s sides

- life management, including family relationships, work, and stress

- substance use habits, including alcohol and tobacco

- sexual activity

- eating habits and physical activity

- past reproductive health experience and any pregnancy complications

- any memory problems (older women)

- screening for depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and interpersonal violence.

To view some of these materials, visit http://www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/final_well-womanbrochure.pdf.

2. Does each woman receive consistent well-woman care?

ACOG’s Well-Woman Task Force was shaped by an awareness that many medical societies and government agencies provide recommendations and guidelines about the basic elements of women’s health. While these recommendations and guidelines all may be based on evidence and expert opinion, the recommendations vary. A goal of the task force was to work with providers across the women’s health spectrum to find consensus and provide guidance to women and clinicians with age-appropriate recommendations for a well-woman visit.

In the fall of 2015, the task force’s findings were published in an article entitled “Components of the well-woman visit” in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology.2 Those findings outline a core set of well-woman care practices across a woman’s lifespan, from adolescence through the reproductive years and into maturity, and they are usable by any provider who cares for adolescent girls or women.

ACOG has summarized its well-woman recommendations, by age, on its website,3 at http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Well-Woman-Recommendations.

3. Do all women have a copay for the well-woman visit?

Because research has revealed that any type of copay or deductible for preventive care significantly lessens the likelihood that patients will seek out such care, the ACA sought to make basic preventive care available without cost sharing.4

The US Department of Health and Human Services notes that: “The Affordable Care Act requires most health plans to cover recommended preventive services without cost sharing. In 2011 and 2012, 71 million Americans with private health insurance gained access to preventive services with no cost sharing because of the law.”4

Grandfathered plans (those created or sold before March 23, 2010) are exempt from this requirement, as are Medicare, TRICARE, and traditional Medicaid plans.

4. What does well-woman care mean from one doctor to another?

Under the ACA, well-woman care can be provided by a “wide range of providers, including family physicians, internists, nurse–midwives, nurse practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, pediatricians, and physician assistants,” depending on the age of the patient, her particular needs and preferences, and access to health services.2

The ACOG Well-Woman Task Force “focused on delineating the well-woman visit throughout the lifespan, across all providers and health plans.”2

In determining the components of well-woman care, ACOG’s task force compiled existing guidelines from many sources, including the Department of Health and Human Services, the IOM, the US Preventive Services Task Force, and each member organization.

Members categorized guidelines as:

- single source (eg, abdominal examination)

- no agreement (breast cancer/mammography screening)

- limited agreement (pelvic examination)

- general agreement (hypertension, osteoporosis)

- sound agreement (screening for sexually transmitted infections)

The task force also agreed that final recommendations would rely on evidence-based guidelines, evidence-informed guidelines, and uniform expert agreement. Recommendations were considered “strong” if they relied primarily on evidence-based or evidence-informed guidelines and “qualified” if they relied primarily on expert consensus.

Guidelines were further separated into age bands:

- adolescents (13–18 years)

- reproductive-aged women (19–45 years)

- mature women (46–64 years)

- women older than 64 years.

The task force recommended that, during the well-woman visit, health care professionals educate patients about:

- healthy eating habits and maintenance of healthy weight

- exercise and physical activity

- seat belt use

- risk factors for certain types of cancer

- heart health

- breast health

- bone health

- safer sex practices and prevention of sexually transmitted infections

- healthy interpersonal relationships

- prevention and management of chronic disease

- resources for the patient (online, written, community, patient groups)

- medication use

- fall prevention.

Health care providers also should counsel patients regarding:

- recommended preventive screenings and immunizations

- any concerns about mood, such as prolonged periods of sadness, a failure to enjoy what they usually find pleasant, or anxiety or irritability that seems out of proportion to events

- what to expect in terms of effects on mood and anxiety at reproductive life transitions, including menarche, pregnancy, the postpartum period, and perimenopause

- body image issues

- what to expect in terms of the menstrual cycle during perimenopause and menopause

- reproductive health or fertility concerns

- reproductive life planning (contraception appropriate for life stage, reproductive plans, and risk factors, including risk factors for breast and ovarian cancer and cardiovascular disease)

- pregnancy planning, including attaining and maintaining a healthy weight and managing any chronic conditions before or during pregnancy

- what to expect during menopause, including signs and symptoms and options for addressing symptoms (midlife and older women)

- symptoms of cardiovascular disease

- urinary incontinence.

The task force acknowledged that not all of these recommendations can be carried out at a single well-woman visit or by a single provider.

See, again, ACOG’s specific well-woman recommendations, by age range, at http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Well-Woman-Recommendations.3

How to winnow a long list of recommendations to determine the most pressing issues for a specific patient

In an editorial accompanying the ACOG Well-Woman Task Force report, entitled “Re-envisioning the annual well-woman visit: the task forward,” George F. Sawaya, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, devised a plan to determine the most pressing well-woman needs for a specific patient.1 He chose as an example a 41-year-old sexually active woman who does not smoke.

While Dr. Sawaya praised the Well-Woman Task Force recommendations for their “comprehensive scope,” he also noted that the sheer number of recommendations might be “overwhelming and difficult to navigate.”1 One tool for winnowing the recommendations comes from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which offers an Electronic Preventive Services Selector (http://epss.ahrq.gov/PDA/index.jsp), available both online and as a smartphone app. Once the clinician plugs in the patient’s age and a few risk factors, the tool generates a list of recommended preventive services. This list of services has been evaluated by the US Preventive Services Task Force, with each recommendation graded “A” through “D,” based on benefits versus harms.

Back to that 41-year-old sexually active woman: Using the Electronic Preventive Services Selector, a list of as many as 20 grade A and B recommendations would be generated. However, only 3 of them would be grade A (screening for cervical cancer, HIV, and high blood pressure). An additional 2 grade B recommendations might apply to an average-risk patient such as this: screening for alcohol misuse and depression. All 5 services fall within the Well-Woman Task Force’s recommendations. They also have “good face validity with clinicians as being important, so it seems reasonable that these be prioritized above the others, at least at the first visit,” Dr. Sawaya says.1

Clinicians can use a similar strategy for patients of various ages and risk factors.

Reference

1. Sawaya GF. Re-envisioning the annual well-woman visit: the task forward [editorial]. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):695–696.

The bottom line

By defining and implementing the foundational elements of women’s health, we can improve care for all women and ensure, as Dr. Conry emphasized during her tenure as ACOG president, “that every woman gets the care she needs, every time.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in 2010, it represented an intended shift from reactive medicine, with its focus on acute and urgent needs, to a model focused on disease prevention.

OBG Management readers know about the important women’s health services ensured by the ACA, including well-woman care, as well as the key role played by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in winning this coverage. ACOG worked closely with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to help define this set of services. And the ACA ensured that women have access to these services, often without copays and deductibles.

ACOG and the National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) work closely on many issues. At first independently and then together, the 2 organizations set out to explore some fundamental issues:

- How does a woman experience the new well-woman benefit when she visits her doctor?

- Does she receive a consistent care set?

- Do some patients have copays while patients in other clinics do not for the same services?

- What does well-woman care mean from one doctor to another, from an ObGyn to an internist to a family physician?

This article explores these issues.

2 initiatives focused on components of women’s health care

During her tenure as president of ACOG, Jeanne Conry, MD, PhD, decided to tackle clinical issues associated with well-woman care. She convened a Well-Woman Task Force, led by Haywood Brown, MD, and included the NWLC among other partner organizations (TABLE).

Table. Partipating organizations of the ACOG Well-Woman Task Force

• American Academy of Family Physicians

• American Academy of Pediatrics

• American Academy of Physician Assistants

• American College of Nurse–Midwives

• American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists

• Association of Reproductive Health Professionals

• Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses

• National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health

• National Medical Association

• National Women’s Law Center

• Planned Parenthood Federation of America

• Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine

• Society of Academic Specialists in General Obstetrics and Gynecology

• Society of Gynecologic Oncology

The NWLC and Brigham and Women’s Hospital also partnered with ACOG and others to help ensure a consistent patient experience. These 2 closely related initiatives were designed to work together to help patients and physicians understand and benefit from new coverage under the ACA.

1. How does a woman experience well-woman care?

Experts associated with these 2 initiatives recognized that well-woman care includes attention to the history, physical examination, counseling, and screening intended to maintain physical, mental, and social wellbeing and general health throughout a woman’s lifespan. Experts also recognized that the ACA guarantees coverage of at least one annual well-woman visit, although not all of the recommended components necessarily would be performed at the same visit or by the same provider.

For many women who have gained insurance coverage under the ACA, the well-woman visit represents their entry into the insured health care system. These women may have limited understanding of the services they should receive during this visit.

To address this issue, the NWLC invited ACOG to participate in its initiative with Brigham and Women’s Hospital to understand the well-woman visit from the patient’s point of view. This effort yielded patient education materials in English and Spanish that help women understand:

- that their health insurance now covers a well-woman visit

- what care is included in that visit

- that there is no deductible or copay for this visit

- how to prepare for this visit

- what questions to ask during the visit.

These materials help women understand that the purpose of the well-woman visit is to provide them with a chance to:

- “receive care and counseling that is appropriate, based on age, cognitive development, and life experience

- review their current health and risks to their health with their health care professional

- ask any questions they may have about their health or risk factors

- talk about what they can do to prevent future health problems

- build a trusting relationship with their health care provider, with an emphasis on confidentiality

- receive appropriate preventive screenings and immunizations and make sure they know which screenings and immunizations they should receive in the future

- review their reproductive plan and contraceptive choices.”1

The materials also advise patients that they may be asked about:

- current health concerns

- current medications, both prescription and over the counter

- family history on both the mother’s and father’s sides

- life management, including family relationships, work, and stress

- substance use habits, including alcohol and tobacco

- sexual activity

- eating habits and physical activity

- past reproductive health experience and any pregnancy complications

- any memory problems (older women)

- screening for depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and interpersonal violence.

To view some of these materials, visit http://www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/final_well-womanbrochure.pdf.

2. Does each woman receive consistent well-woman care?

ACOG’s Well-Woman Task Force was shaped by an awareness that many medical societies and government agencies provide recommendations and guidelines about the basic elements of women’s health. While these recommendations and guidelines all may be based on evidence and expert opinion, the recommendations vary. A goal of the task force was to work with providers across the women’s health spectrum to find consensus and provide guidance to women and clinicians with age-appropriate recommendations for a well-woman visit.

In the fall of 2015, the task force’s findings were published in an article entitled “Components of the well-woman visit” in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology.2 Those findings outline a core set of well-woman care practices across a woman’s lifespan, from adolescence through the reproductive years and into maturity, and they are usable by any provider who cares for adolescent girls or women.

ACOG has summarized its well-woman recommendations, by age, on its website,3 at http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Well-Woman-Recommendations.

3. Do all women have a copay for the well-woman visit?

Because research has revealed that any type of copay or deductible for preventive care significantly lessens the likelihood that patients will seek out such care, the ACA sought to make basic preventive care available without cost sharing.4

The US Department of Health and Human Services notes that: “The Affordable Care Act requires most health plans to cover recommended preventive services without cost sharing. In 2011 and 2012, 71 million Americans with private health insurance gained access to preventive services with no cost sharing because of the law.”4

Grandfathered plans (those created or sold before March 23, 2010) are exempt from this requirement, as are Medicare, TRICARE, and traditional Medicaid plans.

4. What does well-woman care mean from one doctor to another?

Under the ACA, well-woman care can be provided by a “wide range of providers, including family physicians, internists, nurse–midwives, nurse practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, pediatricians, and physician assistants,” depending on the age of the patient, her particular needs and preferences, and access to health services.2

The ACOG Well-Woman Task Force “focused on delineating the well-woman visit throughout the lifespan, across all providers and health plans.”2

In determining the components of well-woman care, ACOG’s task force compiled existing guidelines from many sources, including the Department of Health and Human Services, the IOM, the US Preventive Services Task Force, and each member organization.

Members categorized guidelines as:

- single source (eg, abdominal examination)

- no agreement (breast cancer/mammography screening)

- limited agreement (pelvic examination)

- general agreement (hypertension, osteoporosis)

- sound agreement (screening for sexually transmitted infections)

The task force also agreed that final recommendations would rely on evidence-based guidelines, evidence-informed guidelines, and uniform expert agreement. Recommendations were considered “strong” if they relied primarily on evidence-based or evidence-informed guidelines and “qualified” if they relied primarily on expert consensus.

Guidelines were further separated into age bands:

- adolescents (13–18 years)

- reproductive-aged women (19–45 years)

- mature women (46–64 years)

- women older than 64 years.

The task force recommended that, during the well-woman visit, health care professionals educate patients about:

- healthy eating habits and maintenance of healthy weight

- exercise and physical activity

- seat belt use

- risk factors for certain types of cancer

- heart health

- breast health

- bone health

- safer sex practices and prevention of sexually transmitted infections

- healthy interpersonal relationships

- prevention and management of chronic disease

- resources for the patient (online, written, community, patient groups)

- medication use

- fall prevention.

Health care providers also should counsel patients regarding:

- recommended preventive screenings and immunizations

- any concerns about mood, such as prolonged periods of sadness, a failure to enjoy what they usually find pleasant, or anxiety or irritability that seems out of proportion to events

- what to expect in terms of effects on mood and anxiety at reproductive life transitions, including menarche, pregnancy, the postpartum period, and perimenopause

- body image issues

- what to expect in terms of the menstrual cycle during perimenopause and menopause

- reproductive health or fertility concerns

- reproductive life planning (contraception appropriate for life stage, reproductive plans, and risk factors, including risk factors for breast and ovarian cancer and cardiovascular disease)

- pregnancy planning, including attaining and maintaining a healthy weight and managing any chronic conditions before or during pregnancy

- what to expect during menopause, including signs and symptoms and options for addressing symptoms (midlife and older women)

- symptoms of cardiovascular disease

- urinary incontinence.

The task force acknowledged that not all of these recommendations can be carried out at a single well-woman visit or by a single provider.

See, again, ACOG’s specific well-woman recommendations, by age range, at http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Well-Woman-Recommendations.3

How to winnow a long list of recommendations to determine the most pressing issues for a specific patient

In an editorial accompanying the ACOG Well-Woman Task Force report, entitled “Re-envisioning the annual well-woman visit: the task forward,” George F. Sawaya, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, devised a plan to determine the most pressing well-woman needs for a specific patient.1 He chose as an example a 41-year-old sexually active woman who does not smoke.

While Dr. Sawaya praised the Well-Woman Task Force recommendations for their “comprehensive scope,” he also noted that the sheer number of recommendations might be “overwhelming and difficult to navigate.”1 One tool for winnowing the recommendations comes from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which offers an Electronic Preventive Services Selector (http://epss.ahrq.gov/PDA/index.jsp), available both online and as a smartphone app. Once the clinician plugs in the patient’s age and a few risk factors, the tool generates a list of recommended preventive services. This list of services has been evaluated by the US Preventive Services Task Force, with each recommendation graded “A” through “D,” based on benefits versus harms.

Back to that 41-year-old sexually active woman: Using the Electronic Preventive Services Selector, a list of as many as 20 grade A and B recommendations would be generated. However, only 3 of them would be grade A (screening for cervical cancer, HIV, and high blood pressure). An additional 2 grade B recommendations might apply to an average-risk patient such as this: screening for alcohol misuse and depression. All 5 services fall within the Well-Woman Task Force’s recommendations. They also have “good face validity with clinicians as being important, so it seems reasonable that these be prioritized above the others, at least at the first visit,” Dr. Sawaya says.1

Clinicians can use a similar strategy for patients of various ages and risk factors.

Reference

1. Sawaya GF. Re-envisioning the annual well-woman visit: the task forward [editorial]. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):695–696.

The bottom line

By defining and implementing the foundational elements of women’s health, we can improve care for all women and ensure, as Dr. Conry emphasized during her tenure as ACOG president, “that every woman gets the care she needs, every time.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- National Women’s Law Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Your Guide to Well-Woman Visits. http://www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/final_well-womanbrochure.pdf. Accessed December 8, 2015.

- Conry JA, Brown H. Well-Woman Task Force: Components of the well-woman visit. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):697–701.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Well-Woman Recommendations. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Well-Woman-Recommendations. Accessed December 4, 2015.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Affordable Care Act Rules on Expanding Access to Preventive Services for Women. http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts-and-features/fact-sheets/aca-rules-on-expanding-access-to-preventive-services-for-women/index.html. Updated June 28, 2013. Accessed December 4, 2015.

- National Women’s Law Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Your Guide to Well-Woman Visits. http://www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/final_well-womanbrochure.pdf. Accessed December 8, 2015.

- Conry JA, Brown H. Well-Woman Task Force: Components of the well-woman visit. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):697–701.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Well-Woman Recommendations. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Well-Woman-Recommendations. Accessed December 4, 2015.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Affordable Care Act Rules on Expanding Access to Preventive Services for Women. http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts-and-features/fact-sheets/aca-rules-on-expanding-access-to-preventive-services-for-women/index.html. Updated June 28, 2013. Accessed December 4, 2015.

ACOG plans consensus conference on uniform guidelines for breast cancer screening

The Susan G. Komen Foundation estimates that 84% of breast cancers are found through mammography.1 Clearly, the value of mammography is proven. But controversy and confusion abound on how much mammography, and beginning at what age, is best for women.

Currently, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) all have differing recommendations about mammography and about the importance of clinical breast examinations. These inconsistencies largely are due to different interpretations of the same data, not the data itself, and tend to center on how harm is defined and measured. Importantly, these differences can wreak havoc on our patients’ confidence in our counsel and decision making, and can complicate women’s access to screening. Under the Affordable Care Act, women are guaranteed coverage of annual mammograms, but new USPSTF recommendations, due out soon, may undermine that guarantee.

On October 20, ACOG responded to the ACS’ new recommendations on breast cancer screening by emphasizing our continued advice that women should begin annual mammography screening at age 40, along with a clinical breast exam.2

Consensus conference plansIn an effort to address widespread confusion among patients, health care professionals, and payers, ACOG is convening a consensus conference in January 2016, with the goal of arriving at a consistent set of guidelines that can be agreed to, implemented clinically across the country, and hopefully adopted by insurers, as well. Major organizations and providers of women’s health care, including ACS, will gather to evaluate and interpret the data in greater detail and to consider the available data in the broader context of patient care.

Without doubt, guidelines and recommendations will need to evolve as new evidence emerges, but our hope is that scientific and medical organizations can look at the same evidence and speak with one voice on what is best for women’s health. Our patients would benefit from that alone.

ACOG’s recommendations, summarized

- Clinical breast examination every year for women aged 19 and older.

- Screening mammography every year for women aged 40 and older.

- Breast self-awareness has the potential to detect palpable breast cancer and can be recommended.2

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Susan G. Komen Web site. Accuracy of mammograms. http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/AccuracyofMammograms.html. Updated June 26, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- ACOG Statement on Revised American Cancer Society Recommendations on Breast Cancer Screening. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Web site. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2015/ACOG-Statement-on-Recommendations-on-Breast-Cancer-Screening. Published October 20, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

The Susan G. Komen Foundation estimates that 84% of breast cancers are found through mammography.1 Clearly, the value of mammography is proven. But controversy and confusion abound on how much mammography, and beginning at what age, is best for women.

Currently, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) all have differing recommendations about mammography and about the importance of clinical breast examinations. These inconsistencies largely are due to different interpretations of the same data, not the data itself, and tend to center on how harm is defined and measured. Importantly, these differences can wreak havoc on our patients’ confidence in our counsel and decision making, and can complicate women’s access to screening. Under the Affordable Care Act, women are guaranteed coverage of annual mammograms, but new USPSTF recommendations, due out soon, may undermine that guarantee.

On October 20, ACOG responded to the ACS’ new recommendations on breast cancer screening by emphasizing our continued advice that women should begin annual mammography screening at age 40, along with a clinical breast exam.2

Consensus conference plansIn an effort to address widespread confusion among patients, health care professionals, and payers, ACOG is convening a consensus conference in January 2016, with the goal of arriving at a consistent set of guidelines that can be agreed to, implemented clinically across the country, and hopefully adopted by insurers, as well. Major organizations and providers of women’s health care, including ACS, will gather to evaluate and interpret the data in greater detail and to consider the available data in the broader context of patient care.

Without doubt, guidelines and recommendations will need to evolve as new evidence emerges, but our hope is that scientific and medical organizations can look at the same evidence and speak with one voice on what is best for women’s health. Our patients would benefit from that alone.

ACOG’s recommendations, summarized

- Clinical breast examination every year for women aged 19 and older.

- Screening mammography every year for women aged 40 and older.

- Breast self-awareness has the potential to detect palpable breast cancer and can be recommended.2

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The Susan G. Komen Foundation estimates that 84% of breast cancers are found through mammography.1 Clearly, the value of mammography is proven. But controversy and confusion abound on how much mammography, and beginning at what age, is best for women.

Currently, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) all have differing recommendations about mammography and about the importance of clinical breast examinations. These inconsistencies largely are due to different interpretations of the same data, not the data itself, and tend to center on how harm is defined and measured. Importantly, these differences can wreak havoc on our patients’ confidence in our counsel and decision making, and can complicate women’s access to screening. Under the Affordable Care Act, women are guaranteed coverage of annual mammograms, but new USPSTF recommendations, due out soon, may undermine that guarantee.

On October 20, ACOG responded to the ACS’ new recommendations on breast cancer screening by emphasizing our continued advice that women should begin annual mammography screening at age 40, along with a clinical breast exam.2

Consensus conference plansIn an effort to address widespread confusion among patients, health care professionals, and payers, ACOG is convening a consensus conference in January 2016, with the goal of arriving at a consistent set of guidelines that can be agreed to, implemented clinically across the country, and hopefully adopted by insurers, as well. Major organizations and providers of women’s health care, including ACS, will gather to evaluate and interpret the data in greater detail and to consider the available data in the broader context of patient care.

Without doubt, guidelines and recommendations will need to evolve as new evidence emerges, but our hope is that scientific and medical organizations can look at the same evidence and speak with one voice on what is best for women’s health. Our patients would benefit from that alone.

ACOG’s recommendations, summarized

- Clinical breast examination every year for women aged 19 and older.

- Screening mammography every year for women aged 40 and older.

- Breast self-awareness has the potential to detect palpable breast cancer and can be recommended.2

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Susan G. Komen Web site. Accuracy of mammograms. http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/AccuracyofMammograms.html. Updated June 26, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- ACOG Statement on Revised American Cancer Society Recommendations on Breast Cancer Screening. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Web site. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2015/ACOG-Statement-on-Recommendations-on-Breast-Cancer-Screening. Published October 20, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- Susan G. Komen Web site. Accuracy of mammograms. http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/AccuracyofMammograms.html. Updated June 26, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- ACOG Statement on Revised American Cancer Society Recommendations on Breast Cancer Screening. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Web site. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2015/ACOG-Statement-on-Recommendations-on-Breast-Cancer-Screening. Published October 20, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

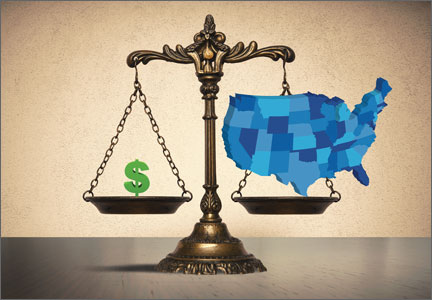

What the Supreme Court ruling in King v. Burwell means for women’s health

In a widely anticipated judgment on the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the US Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of the law on June 26, 2015. The case at hand, King v. Burwell, challenged whether individuals purchasing health insurance through federal exchanges were eligible for federal premium subsidies. This ruling cemented the ACA into law and avoided a potential calamity in the private health insurance market. Let’s take a closer look.

What the case was about

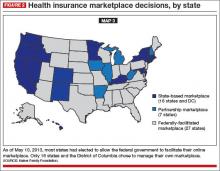

The ACA allows states to set up their own health insurance exchanges or participate in a federally run exchange. Although the drafters of the ACA had expected each state to set up its own exchange, two-thirds of the states declined to do so, many in opposition to the ACA. As a result, 7 million citizens in 34 states now purchase their health insurance through federally created exchanges.

The plaintiffs in King v. Burwell argued that, because the legislation refers to those enrolled “through an Exchange established by the State,” individuals in states with federally run exchanges are not eligible for subsidies.

The law states:

(A) the monthly premiums for such month for 1 or more qualified health plans offered in the individual market within a State which cover the taxpayer, the taxpayer’s spouse, or any dependent (as defined in section 152) of the taxpayer and which were enrolled in through an Exchange established by the State under 1311 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act…[emphasis added].

The Supreme Court was asked to decide whether to adhere to those exact words or to honor Congress’ intent to allow individuals to purchase subsidized insurance on any type of exchange.

What might have happened

We’ve explored in previous articles the interconnectedness of many sections of the ACA. Nowhere is that interconnectedness more clearly demonstrated than here. In order to ensure that private health insurers provide better coverage, the law requires them to abide by important consumer protections, including the elimination of “preexisting condition” exclusions. In order to prevent adverse selection and keep insurers solvent under these new rules, all individuals are required to have health care coverage—the individual mandate. If everyone is required to purchase health insurance, it has to be affordable, so lower-income individuals were promised subsidies, paid for 100% by the federal government, to help them cover their premiums when insurance is purchased through an exchange. Take away the subsidies and the whole thing starts to unravel.

The Urban Institute estimated that a Supreme Court ruling in favor of King, which would have eliminated the subsidies in states using a federal exchange, would have reduced federal tax subsidies by $29 billion in 2016, making coverage unaffordable for many and increasing the ranks of the uninsured by 8.2 million people.1

Louise Sheiner and Brendan Mochoruk of the Brookings Institute speculated that healthy individuals would disproportionately leave the marketplace, triggering 35% increases in insurance premiums for those remaining, as well as significant increases in premiums for those who just lost their subsidies.2 Many observers, including these experts, forecast that insurance companies would exit the federal exchanges altogether, triggering a health insurance “death spiral”: As premiums rise, the healthiest customers leave the marketplace, causing premiums to rise more, causing more healthy people to leave, and so on.

Clearly, this Supreme Court decision has had dramatic, long-term, real-world effects on millions of Americans. On the national level, 6,387,789 individuals were at risk of losing their tax credits if the Supreme Court had ruled in favor of King. That number represents more than $1.7 billion in total monthly tax credits. For a look at how a judgment in favor of King would have affected subsidies on a state-by-state basis, see TABLE 1.

What other commentators are saying about the King v. Burwell decision

In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts noted that the “meaning of the phrase ‘established by the State’ is not so clear.” And as Amy Howe articulated on SCOTUSblog: “if the phrase…is in fact not clear…then the next step is to look at the Affordable Care Act more broadly to determine what Congress meant by the phrase. And when you do that, the Court reasoned, it becomes apparent that Congress actually intended for the subsidies to be available to everyone who buys health insurance on an exchange, no matter who created it. If the subsidies weren’t available in the states with federal exchanges, the Court explained, the insurance markets in those states simply wouldn’t work properly: without the subsidies, almost all of the people who purchased insurance on the exchanges would no longer be required to purchase insurance because it would be too expensive. This would create a ‘death spiral’….”

—Amy Howe, SCOTUSblog3

“Additional court challenges to other ACA provisions are still possible, but King’s six-member majority shows little appetite for challenges threatening the Act’s core structure. Even Scalia’s dissent recognizes that the ACA may one day ‘attain the enduring status of the Social Security Act.’ Thus, the decision may usher in a new era of policy maturity, in which efforts to undermine the ACA diminish, as focus shifts to efforts to implement and improve it.”

—Mark A. Hall, JD, New England Journal of Medicine4

“With the Court upholding the administration’s interpretation of the law, the Obama administration has little reason to accede to

Republican proposals. The Court’s decision effectively puts the future of the ACA on hold until the 2016 elections, when the people will decide whether to stay the course or to chart a very different path.”

—Timothy Jost, Health Affairs5

“A case that 6 months ago seemed to offer the Court’s conservatives a low-risk opportunity to accomplish what they almost did in 2012—kill the Affordable Care Act—became suffused with danger, for the millions of newly insured Americans, of course, but also for the Supreme Court itself. Ideology came face to face with reality, and reality prevailed.”

—Linda Greenhouse, New York Times6

How premium subsidies work

Premium subsidies are actually tax credits. Individuals and families can qualify for them to purchase any type of health insurance offered on an exchange, except catastrophic coverage. To receive the premium tax credit for coverage starting in 2015, a marketplace enrollee must:

- have a household income that is 1 to4 times the federal poverty level. In 2015, the range of incomes that qualify for subsidies is $11,670 for an individual and $23,850 for a family of 4 at 100% of the federal poverty level. At 400% of the federal poverty level, it is $46,680 for an individual and $95,400 for a family of 4.

- lack access to affordable coverage through an employer (including a family member’s employer)

- be ineligible for coverage through Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or other forms of public assistance

- have US citizenship or proof of legal residency

- file taxes jointly if married.

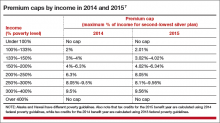

The premium tax credit caps the amount that an individual or family must spend on their monthly payments for health insurance. The cap depends on the family’s income; lower-income families have a lower cap. The amount of the tax credit remains the same, so a person who purchases a more expensive plan pays the cost difference (TABLE 2).

The ruling’s effect on women’s health

On June 26, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists President Mark S. DeFrancesco, MD, MBA, hailed the Supreme Court decision, saying, “Importantly, recent data have shown that newly insured adults under the ACA were more likely to be women. Those who did gain coverage through the ACA reported better access to health care and better financial security from medical costs.”

“Without question, many women enrollees were able to purchase health insurance coverage due, in part, to the ACA subsidies that helped make this purchase affordable. In fact, government data have suggested that roughly 85% of health exchange enrollees received subsidies,” Dr. DeFrancesco said.

“If the Supreme Court had overturned this important assistance, approximately 4.8 million women would have been unable to afford the coverage that they need. The impact also would have been widespread; as these women were forced to leave the insurance marketplace, it is likely that premiums throughout the marketplace would have risen dramatically,” he continued.

“Instead, patients—especially the low- and moderate-income American women who have particularly benefited from ACA subsidies—will continue to have the peace of mind that comes with insurance coverage.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Blumberg LJ, Buettgens M, Holahan J. The implications of a Supreme Court finding for the plaintiff in King v. Burwell: 8.2 million more uninsured and 35% higher premiums. Urban Institute. http://www.urban.org/research/publication/implications-supreme-court-finding-plaintiff-king-vs-burwell-82-million-more-uninsured-and-35-higher-premiums. Published January 8, 2015. Accessed July 2, 2015.

2. Sheiner L, Mochoruk B. King v. Burwell explained. Brookings Institute. http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/health360/posts/2015/03/03-king-v-burwell-explainer-sheiner. Published March 3, 2015. Accessed July 2, 2015.

3. Howe A. Court backs Obama administration on health care subsidies: In plain English. SCOTUSblog. http://www.scotusblog.com/2015/06/court-backs-obama-administration-on-health-care-subsidies-in-plain-english/. Published June 25, 2015. Accessed July 1, 2015.

4. Hall MA. King v. Burwell—ACA Armageddon averted. N Engl J Med. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1504077. Published July 1, 2015. Accessed July 2, 2015.

5. Jost T. Implementing health reform: The Supreme Court upholds tax credits in the federal exchange. Health Affairs blog. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/06/25/implementing-health-reform-the-supreme-court-upholds-tax-credits-in-the-federal-exchange/. Published June 25, 2015. Accessed July 1, 2015.

6. Greenhouse L. The Roberts Court’s reality check. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/26/opinion/the-roberts-courts-reality-check.html. Published June 25, 2015. Accessed July 1, 2015.

7. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Explaining health care reform: questions about health insurance subsidies. Table 2. http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/explaining-health-care-reform-questions-about-health/. Published October 27, 2014. Accessed July 2, 2015.

In a widely anticipated judgment on the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the US Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of the law on June 26, 2015. The case at hand, King v. Burwell, challenged whether individuals purchasing health insurance through federal exchanges were eligible for federal premium subsidies. This ruling cemented the ACA into law and avoided a potential calamity in the private health insurance market. Let’s take a closer look.

What the case was about

The ACA allows states to set up their own health insurance exchanges or participate in a federally run exchange. Although the drafters of the ACA had expected each state to set up its own exchange, two-thirds of the states declined to do so, many in opposition to the ACA. As a result, 7 million citizens in 34 states now purchase their health insurance through federally created exchanges.

The plaintiffs in King v. Burwell argued that, because the legislation refers to those enrolled “through an Exchange established by the State,” individuals in states with federally run exchanges are not eligible for subsidies.

The law states:

(A) the monthly premiums for such month for 1 or more qualified health plans offered in the individual market within a State which cover the taxpayer, the taxpayer’s spouse, or any dependent (as defined in section 152) of the taxpayer and which were enrolled in through an Exchange established by the State under 1311 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act…[emphasis added].

The Supreme Court was asked to decide whether to adhere to those exact words or to honor Congress’ intent to allow individuals to purchase subsidized insurance on any type of exchange.

What might have happened

We’ve explored in previous articles the interconnectedness of many sections of the ACA. Nowhere is that interconnectedness more clearly demonstrated than here. In order to ensure that private health insurers provide better coverage, the law requires them to abide by important consumer protections, including the elimination of “preexisting condition” exclusions. In order to prevent adverse selection and keep insurers solvent under these new rules, all individuals are required to have health care coverage—the individual mandate. If everyone is required to purchase health insurance, it has to be affordable, so lower-income individuals were promised subsidies, paid for 100% by the federal government, to help them cover their premiums when insurance is purchased through an exchange. Take away the subsidies and the whole thing starts to unravel.

The Urban Institute estimated that a Supreme Court ruling in favor of King, which would have eliminated the subsidies in states using a federal exchange, would have reduced federal tax subsidies by $29 billion in 2016, making coverage unaffordable for many and increasing the ranks of the uninsured by 8.2 million people.1

Louise Sheiner and Brendan Mochoruk of the Brookings Institute speculated that healthy individuals would disproportionately leave the marketplace, triggering 35% increases in insurance premiums for those remaining, as well as significant increases in premiums for those who just lost their subsidies.2 Many observers, including these experts, forecast that insurance companies would exit the federal exchanges altogether, triggering a health insurance “death spiral”: As premiums rise, the healthiest customers leave the marketplace, causing premiums to rise more, causing more healthy people to leave, and so on.

Clearly, this Supreme Court decision has had dramatic, long-term, real-world effects on millions of Americans. On the national level, 6,387,789 individuals were at risk of losing their tax credits if the Supreme Court had ruled in favor of King. That number represents more than $1.7 billion in total monthly tax credits. For a look at how a judgment in favor of King would have affected subsidies on a state-by-state basis, see TABLE 1.

What other commentators are saying about the King v. Burwell decision

In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts noted that the “meaning of the phrase ‘established by the State’ is not so clear.” And as Amy Howe articulated on SCOTUSblog: “if the phrase…is in fact not clear…then the next step is to look at the Affordable Care Act more broadly to determine what Congress meant by the phrase. And when you do that, the Court reasoned, it becomes apparent that Congress actually intended for the subsidies to be available to everyone who buys health insurance on an exchange, no matter who created it. If the subsidies weren’t available in the states with federal exchanges, the Court explained, the insurance markets in those states simply wouldn’t work properly: without the subsidies, almost all of the people who purchased insurance on the exchanges would no longer be required to purchase insurance because it would be too expensive. This would create a ‘death spiral’….”

—Amy Howe, SCOTUSblog3

“Additional court challenges to other ACA provisions are still possible, but King’s six-member majority shows little appetite for challenges threatening the Act’s core structure. Even Scalia’s dissent recognizes that the ACA may one day ‘attain the enduring status of the Social Security Act.’ Thus, the decision may usher in a new era of policy maturity, in which efforts to undermine the ACA diminish, as focus shifts to efforts to implement and improve it.”

—Mark A. Hall, JD, New England Journal of Medicine4

“With the Court upholding the administration’s interpretation of the law, the Obama administration has little reason to accede to

Republican proposals. The Court’s decision effectively puts the future of the ACA on hold until the 2016 elections, when the people will decide whether to stay the course or to chart a very different path.”

—Timothy Jost, Health Affairs5

“A case that 6 months ago seemed to offer the Court’s conservatives a low-risk opportunity to accomplish what they almost did in 2012—kill the Affordable Care Act—became suffused with danger, for the millions of newly insured Americans, of course, but also for the Supreme Court itself. Ideology came face to face with reality, and reality prevailed.”

—Linda Greenhouse, New York Times6

How premium subsidies work

Premium subsidies are actually tax credits. Individuals and families can qualify for them to purchase any type of health insurance offered on an exchange, except catastrophic coverage. To receive the premium tax credit for coverage starting in 2015, a marketplace enrollee must:

- have a household income that is 1 to4 times the federal poverty level. In 2015, the range of incomes that qualify for subsidies is $11,670 for an individual and $23,850 for a family of 4 at 100% of the federal poverty level. At 400% of the federal poverty level, it is $46,680 for an individual and $95,400 for a family of 4.

- lack access to affordable coverage through an employer (including a family member’s employer)

- be ineligible for coverage through Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or other forms of public assistance

- have US citizenship or proof of legal residency

- file taxes jointly if married.

The premium tax credit caps the amount that an individual or family must spend on their monthly payments for health insurance. The cap depends on the family’s income; lower-income families have a lower cap. The amount of the tax credit remains the same, so a person who purchases a more expensive plan pays the cost difference (TABLE 2).

The ruling’s effect on women’s health

On June 26, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists President Mark S. DeFrancesco, MD, MBA, hailed the Supreme Court decision, saying, “Importantly, recent data have shown that newly insured adults under the ACA were more likely to be women. Those who did gain coverage through the ACA reported better access to health care and better financial security from medical costs.”

“Without question, many women enrollees were able to purchase health insurance coverage due, in part, to the ACA subsidies that helped make this purchase affordable. In fact, government data have suggested that roughly 85% of health exchange enrollees received subsidies,” Dr. DeFrancesco said.

“If the Supreme Court had overturned this important assistance, approximately 4.8 million women would have been unable to afford the coverage that they need. The impact also would have been widespread; as these women were forced to leave the insurance marketplace, it is likely that premiums throughout the marketplace would have risen dramatically,” he continued.

“Instead, patients—especially the low- and moderate-income American women who have particularly benefited from ACA subsidies—will continue to have the peace of mind that comes with insurance coverage.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In a widely anticipated judgment on the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the US Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of the law on June 26, 2015. The case at hand, King v. Burwell, challenged whether individuals purchasing health insurance through federal exchanges were eligible for federal premium subsidies. This ruling cemented the ACA into law and avoided a potential calamity in the private health insurance market. Let’s take a closer look.

What the case was about

The ACA allows states to set up their own health insurance exchanges or participate in a federally run exchange. Although the drafters of the ACA had expected each state to set up its own exchange, two-thirds of the states declined to do so, many in opposition to the ACA. As a result, 7 million citizens in 34 states now purchase their health insurance through federally created exchanges.

The plaintiffs in King v. Burwell argued that, because the legislation refers to those enrolled “through an Exchange established by the State,” individuals in states with federally run exchanges are not eligible for subsidies.

The law states:

(A) the monthly premiums for such month for 1 or more qualified health plans offered in the individual market within a State which cover the taxpayer, the taxpayer’s spouse, or any dependent (as defined in section 152) of the taxpayer and which were enrolled in through an Exchange established by the State under 1311 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act…[emphasis added].

The Supreme Court was asked to decide whether to adhere to those exact words or to honor Congress’ intent to allow individuals to purchase subsidized insurance on any type of exchange.

What might have happened

We’ve explored in previous articles the interconnectedness of many sections of the ACA. Nowhere is that interconnectedness more clearly demonstrated than here. In order to ensure that private health insurers provide better coverage, the law requires them to abide by important consumer protections, including the elimination of “preexisting condition” exclusions. In order to prevent adverse selection and keep insurers solvent under these new rules, all individuals are required to have health care coverage—the individual mandate. If everyone is required to purchase health insurance, it has to be affordable, so lower-income individuals were promised subsidies, paid for 100% by the federal government, to help them cover their premiums when insurance is purchased through an exchange. Take away the subsidies and the whole thing starts to unravel.

The Urban Institute estimated that a Supreme Court ruling in favor of King, which would have eliminated the subsidies in states using a federal exchange, would have reduced federal tax subsidies by $29 billion in 2016, making coverage unaffordable for many and increasing the ranks of the uninsured by 8.2 million people.1

Louise Sheiner and Brendan Mochoruk of the Brookings Institute speculated that healthy individuals would disproportionately leave the marketplace, triggering 35% increases in insurance premiums for those remaining, as well as significant increases in premiums for those who just lost their subsidies.2 Many observers, including these experts, forecast that insurance companies would exit the federal exchanges altogether, triggering a health insurance “death spiral”: As premiums rise, the healthiest customers leave the marketplace, causing premiums to rise more, causing more healthy people to leave, and so on.

Clearly, this Supreme Court decision has had dramatic, long-term, real-world effects on millions of Americans. On the national level, 6,387,789 individuals were at risk of losing their tax credits if the Supreme Court had ruled in favor of King. That number represents more than $1.7 billion in total monthly tax credits. For a look at how a judgment in favor of King would have affected subsidies on a state-by-state basis, see TABLE 1.

What other commentators are saying about the King v. Burwell decision

In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts noted that the “meaning of the phrase ‘established by the State’ is not so clear.” And as Amy Howe articulated on SCOTUSblog: “if the phrase…is in fact not clear…then the next step is to look at the Affordable Care Act more broadly to determine what Congress meant by the phrase. And when you do that, the Court reasoned, it becomes apparent that Congress actually intended for the subsidies to be available to everyone who buys health insurance on an exchange, no matter who created it. If the subsidies weren’t available in the states with federal exchanges, the Court explained, the insurance markets in those states simply wouldn’t work properly: without the subsidies, almost all of the people who purchased insurance on the exchanges would no longer be required to purchase insurance because it would be too expensive. This would create a ‘death spiral’….”

—Amy Howe, SCOTUSblog3

“Additional court challenges to other ACA provisions are still possible, but King’s six-member majority shows little appetite for challenges threatening the Act’s core structure. Even Scalia’s dissent recognizes that the ACA may one day ‘attain the enduring status of the Social Security Act.’ Thus, the decision may usher in a new era of policy maturity, in which efforts to undermine the ACA diminish, as focus shifts to efforts to implement and improve it.”

—Mark A. Hall, JD, New England Journal of Medicine4

“With the Court upholding the administration’s interpretation of the law, the Obama administration has little reason to accede to

Republican proposals. The Court’s decision effectively puts the future of the ACA on hold until the 2016 elections, when the people will decide whether to stay the course or to chart a very different path.”

—Timothy Jost, Health Affairs5