User login

Just a Case of The Flu?

ANSWER

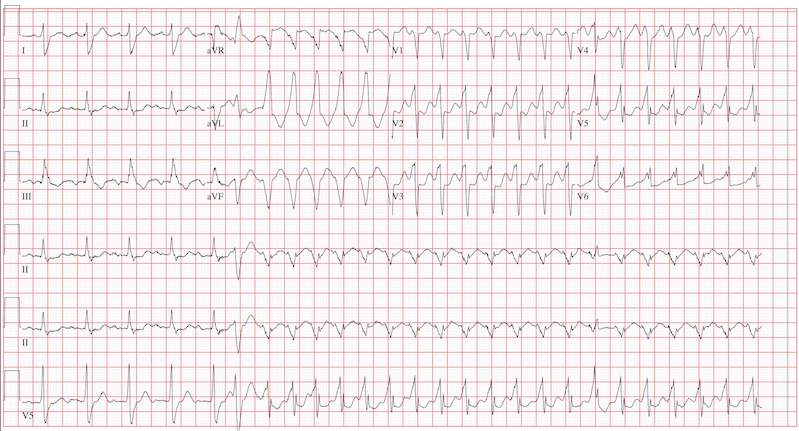

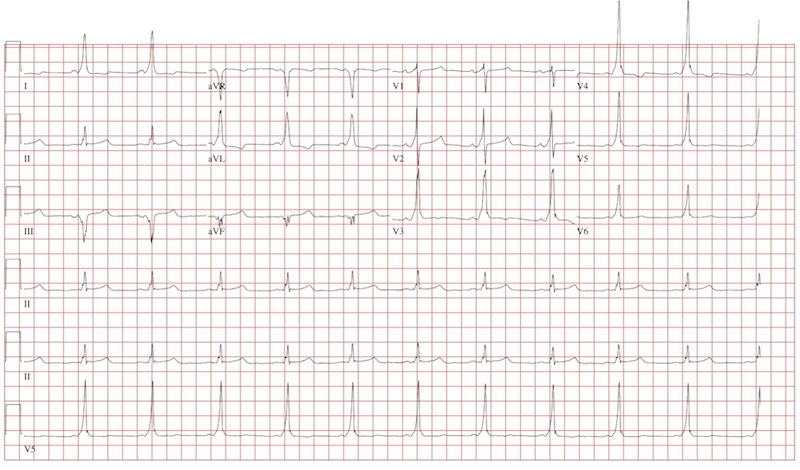

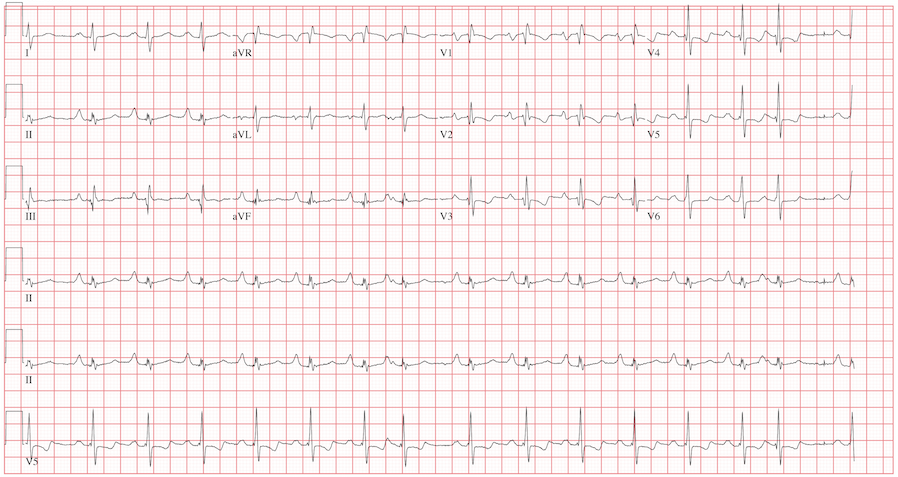

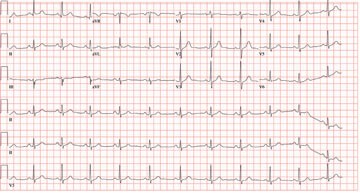

This ECG reveals sinus tachycardia transitioning to a wide complex tachycardia. A fusion complex is present, suggesting this is ventricular tachycardia. T-wave abnormalities in the inferior leads are present and suggest inferior ischemia.

There are two items of note that one must be aware of in order to accurately interpret this ECG. Normally, the computer measurements of heart rate and intervals are correct and often more accurate than a clinician can manually measure. These are typically measured as an average of all beats taken during the 12-second analysis prior to printing. However, when the rate abruptly changes during the analysis of the heart rate and rhythm, these measurements become inaccurate.

In this ECG, the computer notes the rate to be 156 beats/min; however, careful analysis of the sinus tachycardia prior to onset of ventricular tachycardia shows the rate is 107 beats/min, and the ventricular tachycardia rate is 188 beats/min.

The second item of note is that the ECG instrument measures all leads simultaneously over a 12-second period and separates them into the appropriate leads for printing. Hence, the progression from leads I to aVR to V1 to V4 represents a continuous tracing, in a similar fashion to the rhythm strip in lead II at the bottom of the page. Knowing this can help determine the presence of fusion complexes, as well as atrioventricular dissociation between QRS complexes and P waves indicative of ventricular tachycardia.

This patient developed hemodynamically significant ventricular tachycardia during the 12-second interval required for a 12-lead ECG analysis, a rare occurrence. She was treated with DC cardioversion, which resulted in a return to normal sinus rhythm.

ANSWER

This ECG reveals sinus tachycardia transitioning to a wide complex tachycardia. A fusion complex is present, suggesting this is ventricular tachycardia. T-wave abnormalities in the inferior leads are present and suggest inferior ischemia.

There are two items of note that one must be aware of in order to accurately interpret this ECG. Normally, the computer measurements of heart rate and intervals are correct and often more accurate than a clinician can manually measure. These are typically measured as an average of all beats taken during the 12-second analysis prior to printing. However, when the rate abruptly changes during the analysis of the heart rate and rhythm, these measurements become inaccurate.

In this ECG, the computer notes the rate to be 156 beats/min; however, careful analysis of the sinus tachycardia prior to onset of ventricular tachycardia shows the rate is 107 beats/min, and the ventricular tachycardia rate is 188 beats/min.

The second item of note is that the ECG instrument measures all leads simultaneously over a 12-second period and separates them into the appropriate leads for printing. Hence, the progression from leads I to aVR to V1 to V4 represents a continuous tracing, in a similar fashion to the rhythm strip in lead II at the bottom of the page. Knowing this can help determine the presence of fusion complexes, as well as atrioventricular dissociation between QRS complexes and P waves indicative of ventricular tachycardia.

This patient developed hemodynamically significant ventricular tachycardia during the 12-second interval required for a 12-lead ECG analysis, a rare occurrence. She was treated with DC cardioversion, which resulted in a return to normal sinus rhythm.

ANSWER

This ECG reveals sinus tachycardia transitioning to a wide complex tachycardia. A fusion complex is present, suggesting this is ventricular tachycardia. T-wave abnormalities in the inferior leads are present and suggest inferior ischemia.

There are two items of note that one must be aware of in order to accurately interpret this ECG. Normally, the computer measurements of heart rate and intervals are correct and often more accurate than a clinician can manually measure. These are typically measured as an average of all beats taken during the 12-second analysis prior to printing. However, when the rate abruptly changes during the analysis of the heart rate and rhythm, these measurements become inaccurate.

In this ECG, the computer notes the rate to be 156 beats/min; however, careful analysis of the sinus tachycardia prior to onset of ventricular tachycardia shows the rate is 107 beats/min, and the ventricular tachycardia rate is 188 beats/min.

The second item of note is that the ECG instrument measures all leads simultaneously over a 12-second period and separates them into the appropriate leads for printing. Hence, the progression from leads I to aVR to V1 to V4 represents a continuous tracing, in a similar fashion to the rhythm strip in lead II at the bottom of the page. Knowing this can help determine the presence of fusion complexes, as well as atrioventricular dissociation between QRS complexes and P waves indicative of ventricular tachycardia.

This patient developed hemodynamically significant ventricular tachycardia during the 12-second interval required for a 12-lead ECG analysis, a rare occurrence. She was treated with DC cardioversion, which resulted in a return to normal sinus rhythm.

An 80-year-old woman presents to the emergency department (ED) with chest tightness and palpitations over the past three hours. She called her primary care provider to make an appointment, but was prompted to go directly to the ED. She was transported by her granddaughter, who remains with her. The patient tries to downplay her symptoms as “a case of the flu”; however, the granddaughter states that for the past two weeks, her grandmother has had increased shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, a six-pound weight gain, and bilateral lower extremity edema not previously present. The patient denies fevers, chills, productive cough, syncope, or near-syncope. Medical history is remarkable for a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement (21-mm Carpentier-Edwards pericardial valve) in May 2008 for critical aortic stenosis, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation requiring cardioversion on two separate occasions (the last, six months ago). Her most recent echocardiogram (one year ago) was remarkable for bioprosthetic aortic valve dysfunction with a peak gradient of 60 mm Hg across the valve, well preserved left ventricular systolic function without segmental contraction abnormalities, and mild diastolic dysfunction with a left ventricular ejection fraction estimated to be 55%. Associated findings included mild to moderate mitral regurgitation and left atrial enlargement. Her right heart and central venous pressures were normal. Medical history is also remarkable for a recent (four months ago) episode of shingles involving her left chest and flank. The patient is a retired librarian, is self-sufficient, and lives alone. Her granddaughter lives across the street from her and checks on her daily. The patient has never smoked and has an occasional glass of wine. Her current medications include furosemide, pravastatin, metoprolol XL, a multivitamin, and sublingual nitroglycerin as needed. Of note, she did not use the sublingual nitroglycerin prior to presenting to the ED, and upon inspection, the prescription is long past its expiration date. Physical examination reveals a blood pressure of 92/66 mm Hg; pulse, 100 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min. The patient is afebrile. Pertinent physical findings include jugular venous distention to the level of the jaw, lungs that are clear to auscultation, a musical grade III/VI systolic murmur best heard at the apex with radiation to the carotid arteries bilaterally, a benign abdominal exam, and 3+ pitting edema to the level of the mid-thigh bilaterally. The neurologic exam is grossly intact. Suspecting another episode of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, you order an ECG. The ECG technician arrives, connects the electrodes to the patient, and promptly calls for help as the patient’s chest tightness returns and she becomes lightheaded and dizzy. You arrive promptly and are handed the ECG, which shows: a ventricular rate of 156 beats/min; PR interval, 190 ms; QRS duration, 138 ms; QT/QTc, 362/583 ms; P axis, –5°; R axis, 114°; and T axis, 0°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Exertional Dyspnea Forces Man to Leave Job and Gain Weight

ANSWER

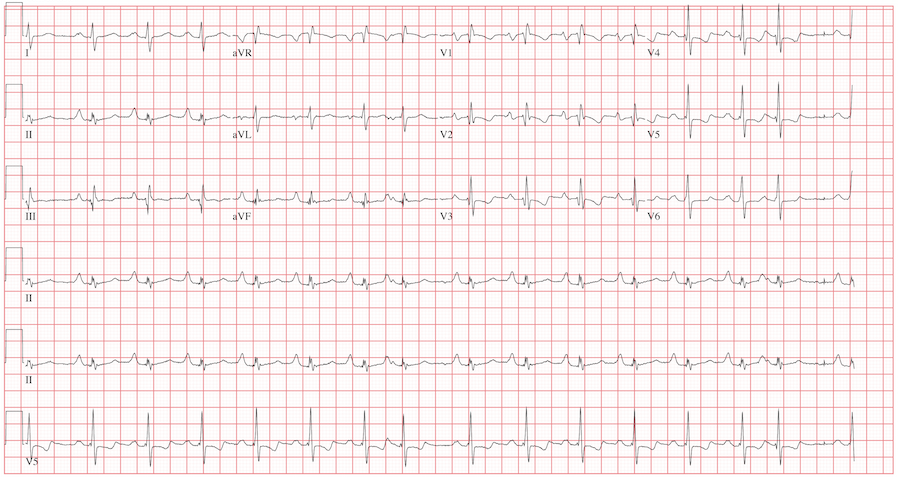

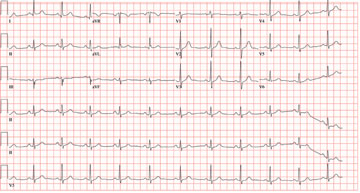

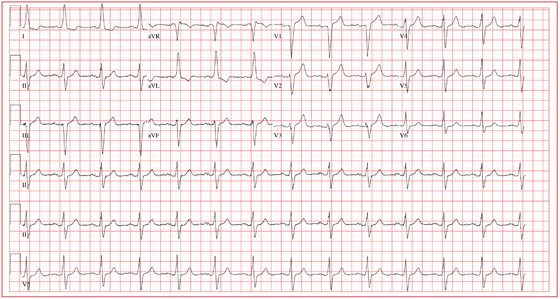

The ECG reveals sinus rhythm with a marked sinus arrhythmia, biatrial enlargement, incomplete right bundle branch block, right ventricular hypertrophy, ST and T wave abnormalities in the anterolateral precordial leads, and a prolonged QT interval.

There is a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, and each P wave is similar in its respective lead (sinus rhythm); however, the rate is irregular, hence the diagnosis of marked sinus arrhythmia. Biatrial enlargement is illustrated by the presence of notched P waves in leads I and V1 with peaked P waves in leads II, III, and aVF (right atrial enlargement) and a P wave ≥ 110 ms in lead I with a terminally negative P wave ≥ 1 mm2 in V1 (left atrial enlargement).

An incomplete right bundle branch block is illustrated by the presence of an RSR’ in lead V1 with a small R and a QRS duration which is borderline normal (< 100 ms). Right ventricular hypertrophy is demonstrated by the presence of a tall R wave in V1 (in this case, R’) that is ≥ S wave in V1, an inverted T wave in V1, borderline right-axis deviation (R axis, 90°), and right atrial enlargement.

ST and T wave changes in the lateral leads are suggestive of anterolateral ischemia; however, in this case they are indicative of repolarization changes from right ventricular enlargement and an incomplete right bundle branch block. Finally, QT prolongation is suggested by the presence of a QT interval > 400 ms in a man when corrected for rate.

The patient’s history, physical examination, and ECG are highly suspicious for right-sided heart failure with the presence of jugular venous distention, a murmur of tricuspid insufficiency, hepatic congestion, and peripheral edema, as well as ECG documentation of right atrial and ventricular enlargement (cor pulmonale). An echocardiogram subsequently confirmed the diagnosis and also revealed pulmonary hypertension, with pulmonary artery pressures of 70 mm Hg.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals sinus rhythm with a marked sinus arrhythmia, biatrial enlargement, incomplete right bundle branch block, right ventricular hypertrophy, ST and T wave abnormalities in the anterolateral precordial leads, and a prolonged QT interval.

There is a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, and each P wave is similar in its respective lead (sinus rhythm); however, the rate is irregular, hence the diagnosis of marked sinus arrhythmia. Biatrial enlargement is illustrated by the presence of notched P waves in leads I and V1 with peaked P waves in leads II, III, and aVF (right atrial enlargement) and a P wave ≥ 110 ms in lead I with a terminally negative P wave ≥ 1 mm2 in V1 (left atrial enlargement).

An incomplete right bundle branch block is illustrated by the presence of an RSR’ in lead V1 with a small R and a QRS duration which is borderline normal (< 100 ms). Right ventricular hypertrophy is demonstrated by the presence of a tall R wave in V1 (in this case, R’) that is ≥ S wave in V1, an inverted T wave in V1, borderline right-axis deviation (R axis, 90°), and right atrial enlargement.

ST and T wave changes in the lateral leads are suggestive of anterolateral ischemia; however, in this case they are indicative of repolarization changes from right ventricular enlargement and an incomplete right bundle branch block. Finally, QT prolongation is suggested by the presence of a QT interval > 400 ms in a man when corrected for rate.

The patient’s history, physical examination, and ECG are highly suspicious for right-sided heart failure with the presence of jugular venous distention, a murmur of tricuspid insufficiency, hepatic congestion, and peripheral edema, as well as ECG documentation of right atrial and ventricular enlargement (cor pulmonale). An echocardiogram subsequently confirmed the diagnosis and also revealed pulmonary hypertension, with pulmonary artery pressures of 70 mm Hg.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals sinus rhythm with a marked sinus arrhythmia, biatrial enlargement, incomplete right bundle branch block, right ventricular hypertrophy, ST and T wave abnormalities in the anterolateral precordial leads, and a prolonged QT interval.

There is a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, and each P wave is similar in its respective lead (sinus rhythm); however, the rate is irregular, hence the diagnosis of marked sinus arrhythmia. Biatrial enlargement is illustrated by the presence of notched P waves in leads I and V1 with peaked P waves in leads II, III, and aVF (right atrial enlargement) and a P wave ≥ 110 ms in lead I with a terminally negative P wave ≥ 1 mm2 in V1 (left atrial enlargement).

An incomplete right bundle branch block is illustrated by the presence of an RSR’ in lead V1 with a small R and a QRS duration which is borderline normal (< 100 ms). Right ventricular hypertrophy is demonstrated by the presence of a tall R wave in V1 (in this case, R’) that is ≥ S wave in V1, an inverted T wave in V1, borderline right-axis deviation (R axis, 90°), and right atrial enlargement.

ST and T wave changes in the lateral leads are suggestive of anterolateral ischemia; however, in this case they are indicative of repolarization changes from right ventricular enlargement and an incomplete right bundle branch block. Finally, QT prolongation is suggested by the presence of a QT interval > 400 ms in a man when corrected for rate.

The patient’s history, physical examination, and ECG are highly suspicious for right-sided heart failure with the presence of jugular venous distention, a murmur of tricuspid insufficiency, hepatic congestion, and peripheral edema, as well as ECG documentation of right atrial and ventricular enlargement (cor pulmonale). An echocardiogram subsequently confirmed the diagnosis and also revealed pulmonary hypertension, with pulmonary artery pressures of 70 mm Hg.

A 42-year-old man has a two-year history of exertional dyspnea. In the past six months, his condition has become significant enough to force him to leave his job as a general contractor. He presents today with dizziness while standing, but not while walking. He denies syncope or near-syncope, angina, or palpitations. He says he has gained weight over the past month, to the extent that his clothes no longer fit. He attributes this to not working or exercising, and he believes this may be the cause of his increased exertional dyspnea. Medical history is remarkable for pneumonia 10 years ago. Surgical history is remarkable for repair of a right femoral fracture sustained in an automobile accident at age 17. The patient has worked in construction and as a general contractor, but had to stop two months ago secondary to dyspnea and chronic fatigue. He is unmarried, is active in his church, does not smoke or drink, and denies recreational drug use. His father died at 66 of lung cancer related to smoking. His mother and three siblings are alive and in good health. He is not allergic to any known medications, and his current medications include ibuprofen as needed for muscular aches and pains and an aspirin a day “because my dad’s doctor recommended it.” The review of systems is remarkable for fatigue despite the fact that the patient has been getting plenty of sleep. His girlfriend says he has been snoring loudly for the past two weeks and has never snored in the past. The man also states that he has had vague abdominal discomfort, without change in his bowel or bladder habits, and has noticed swelling in his lower extremities. He is alarmed to find out he has gained 24 lb in the past month. The physical exam reveals an anxious, obese, white man with a weight of 298 lb. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 114/80 mm Hg; pulse, 94 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 90% on room air. He is afebrile. Pertinent physical findings include jugular venous distention to the angle of the jaw and lungs that are clear to auscultation with a few late expiratory wheezes. The cardiac exam reveals distant heart sounds with a grade III/VI holosystolic low-frequency murmur best heard at the left lower sternal border. The abdominal exam is remarkable for mild hepatomegaly, which is tender to deep palpation. The lower extremities demonstrate 2+ pitting edema to the level of the knees bilaterally. The neurologic exam is intact. Laboratory blood work, an echocardiogram, and an ECG are ordered. The ECG is performed first and reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 94 beats/min; PR interval, 186 ms; QRS duration, 98 ms; QT/QTc interval, 384/480 ms; P axis, 62°; R axis, 90°; and T axis, 48°. What is your interpretation of this ECG, and how does it correlate with the history and physical exam?

Woman with Chest Pain While in Mexico

Answer

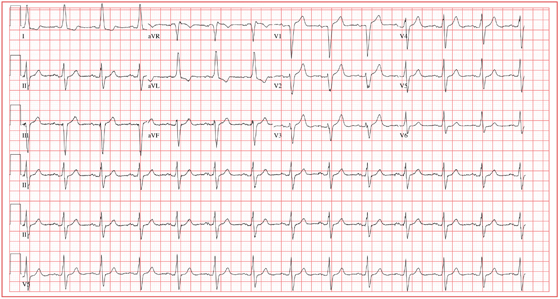

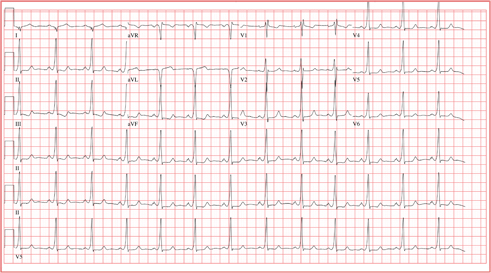

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm with left-axis deviation and left ventricular hypertrophy with QRS widening and repolarization abnormality, with no evidence of ischemia. Left-axis deviation is defined by an R-wave axis of less than –30° and is determined by examining leads III, aVF, and II. If leads III, aVF, and II are all negative, left-axis deviation is present. In this example, leads III and aVF are negative, while lead II is isoelectric or slightly negative.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is defined by high voltages in the limb leads (R wave in lead I plus S wave in lead III ≥ 25 mm) or in the precordial leads (S wave in V1 plus R wave in V5 or V6 ≥ 35 mm). The QRS duration, measured from the first deflection of the QRS from baseline to its return to baseline, is normal if ≤ 100 ms (0.10 sec). In this example, the QRS is widened (130 ms) in the absence of a bundle branch block. The delayed depolarization of both ventricles in the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy results in delayed repolarization—hence the repolarization abnormality.

This patient underwent cardiac catheterization, which revealed extensive three-vessel coronary artery disease with 99% stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. This case illustrates that severe coronary artery disease can present without ECG evidence of ischemia, particularly in women and in patients with diabetes.

Answer

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm with left-axis deviation and left ventricular hypertrophy with QRS widening and repolarization abnormality, with no evidence of ischemia. Left-axis deviation is defined by an R-wave axis of less than –30° and is determined by examining leads III, aVF, and II. If leads III, aVF, and II are all negative, left-axis deviation is present. In this example, leads III and aVF are negative, while lead II is isoelectric or slightly negative.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is defined by high voltages in the limb leads (R wave in lead I plus S wave in lead III ≥ 25 mm) or in the precordial leads (S wave in V1 plus R wave in V5 or V6 ≥ 35 mm). The QRS duration, measured from the first deflection of the QRS from baseline to its return to baseline, is normal if ≤ 100 ms (0.10 sec). In this example, the QRS is widened (130 ms) in the absence of a bundle branch block. The delayed depolarization of both ventricles in the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy results in delayed repolarization—hence the repolarization abnormality.

This patient underwent cardiac catheterization, which revealed extensive three-vessel coronary artery disease with 99% stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. This case illustrates that severe coronary artery disease can present without ECG evidence of ischemia, particularly in women and in patients with diabetes.

Answer

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm with left-axis deviation and left ventricular hypertrophy with QRS widening and repolarization abnormality, with no evidence of ischemia. Left-axis deviation is defined by an R-wave axis of less than –30° and is determined by examining leads III, aVF, and II. If leads III, aVF, and II are all negative, left-axis deviation is present. In this example, leads III and aVF are negative, while lead II is isoelectric or slightly negative.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is defined by high voltages in the limb leads (R wave in lead I plus S wave in lead III ≥ 25 mm) or in the precordial leads (S wave in V1 plus R wave in V5 or V6 ≥ 35 mm). The QRS duration, measured from the first deflection of the QRS from baseline to its return to baseline, is normal if ≤ 100 ms (0.10 sec). In this example, the QRS is widened (130 ms) in the absence of a bundle branch block. The delayed depolarization of both ventricles in the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy results in delayed repolarization—hence the repolarization abnormality.

This patient underwent cardiac catheterization, which revealed extensive three-vessel coronary artery disease with 99% stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. This case illustrates that severe coronary artery disease can present without ECG evidence of ischemia, particularly in women and in patients with diabetes.

For two weeks, a Spanish-speaking woman, 60, has experienced substernal chest pain and shortness of breath. The pain began while she was visiting family in Mexico. She was seen by a local physician, who prescribed a medication that helped but did not relieve the pain completely. She exhausted her supply of this medication shortly after returning from vacation, and her chest pain worsened. The patient’s daughter transported her to your clinic, concerned that her mother may be having a heart attack. According to the daughter, who is interpreting, the pain is described as grade IV/X, intermittent, radiating to the back, and lasting for approximately 10 minutes before subsiding. It is exacerbated with activity, particularly climbing stairs, and resolves when the woman is at rest. She has been awakened by this pain on two occasions. The patient denies fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, or syncope. Medical history is remarkable for hypertension, diabetes, and asthma. She has worked most of her life as a farm worker and as a cook. She does not use alcohol and has a 20–pack-year history of tobacco use. The patient’s medications include aspirin, metformin, pravastatin, telmisartan, verapamil, and a salmeterol inhaler. She is allergic to penicillin. Review of symptoms is remarkable for diarrhea that is resolving and headaches. Physical examination reveals a well-developed, obese woman who is comfortable, alert, and oriented. Her height is 5’3”; weight, 211 lb; blood pressure, 106/40 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; and temperature, 99.2°F. The cardiovascular exam reveals a normal rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, or extra heart sounds. There are no carotid bruits or peripheral edema. The lungs are remarkable for scattered expiratory wheezes in both bases, with the right greater than the left. The abdomen is large but soft with good bowel tones in all quadrants. There are no palpable bruits or organomegaly. The neurologic exam shows no gross neural deficits. The serum glucose level is 148 mg/dL; hemoglobin, 10.6 g/dL; and troponin, 0.02 ng/mL. All other lab values are within normal limits. An ECG shows the following: a ventricular rate of 80 beats/min; PR interval, 168 ms; QRS duration, 130 ms; QT/QTc, 384/442 ms; P axis, 29°; R axis, –34°; and T axis, 96°. What is your interpretation of this ECG, and is there any evidence of ongoing ischemia?

Basketball Player with Continuous Palpitations

ANSWER

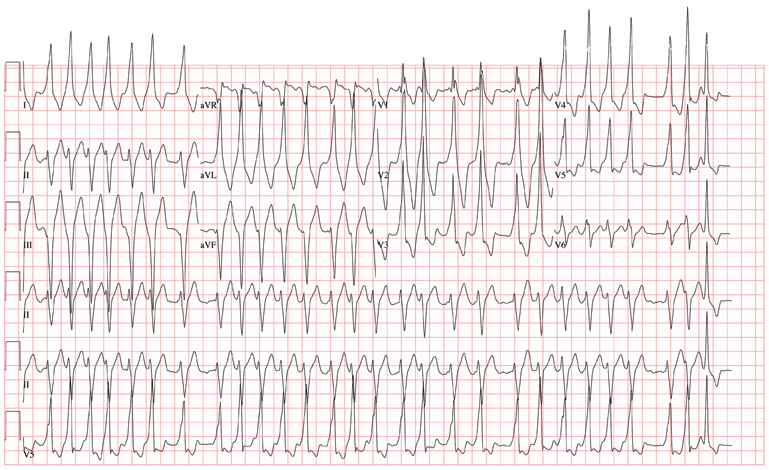

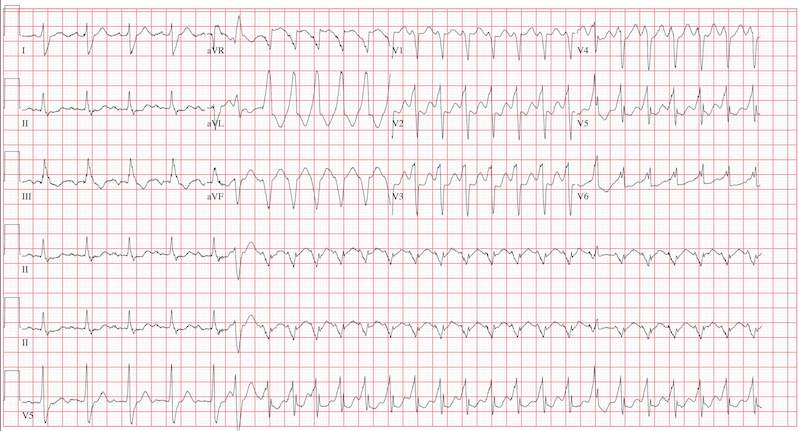

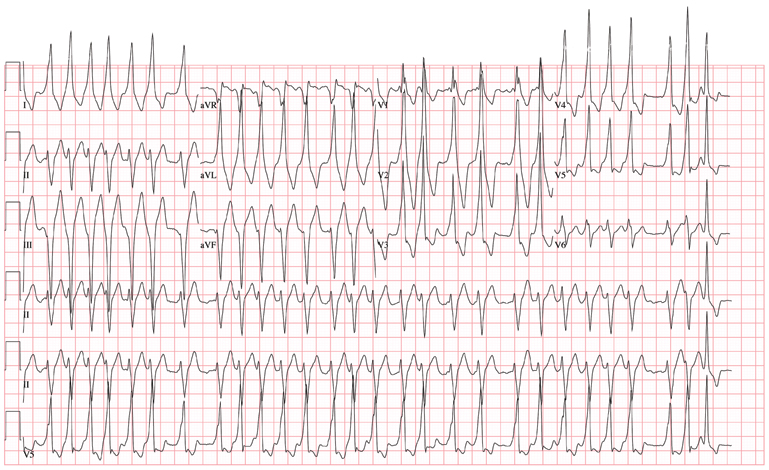

The ECG demonstrates atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response with aberrantly conducted complexes, left-axis deviation, and marked T-wave abnormality. Atrial fibrillation in the setting of WPW with antegrade conduction down the accessory pathway can be life threatening. Unlike the AV node, which can decrementally slow rapid conduction to the ventricle, the accessory pathway can conduct atrial fibrillation impulses into the ventricle in a 1:1 ratio; if uncontrolled, this can result in ventricular tachycardia and/or ventricular fibrillation.

The patient was started on a procainamide drip and converted to normal sinus rhythm. He underwent an electrophysiology study, which demonstrated a single accessory pathway capable of conducting at rates of 250 beats/min located in the lateral wall of the left atrium. It was successfully ablated, resulting in normalization of his ECG.

ANSWER

The ECG demonstrates atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response with aberrantly conducted complexes, left-axis deviation, and marked T-wave abnormality. Atrial fibrillation in the setting of WPW with antegrade conduction down the accessory pathway can be life threatening. Unlike the AV node, which can decrementally slow rapid conduction to the ventricle, the accessory pathway can conduct atrial fibrillation impulses into the ventricle in a 1:1 ratio; if uncontrolled, this can result in ventricular tachycardia and/or ventricular fibrillation.

The patient was started on a procainamide drip and converted to normal sinus rhythm. He underwent an electrophysiology study, which demonstrated a single accessory pathway capable of conducting at rates of 250 beats/min located in the lateral wall of the left atrium. It was successfully ablated, resulting in normalization of his ECG.

ANSWER

The ECG demonstrates atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response with aberrantly conducted complexes, left-axis deviation, and marked T-wave abnormality. Atrial fibrillation in the setting of WPW with antegrade conduction down the accessory pathway can be life threatening. Unlike the AV node, which can decrementally slow rapid conduction to the ventricle, the accessory pathway can conduct atrial fibrillation impulses into the ventricle in a 1:1 ratio; if uncontrolled, this can result in ventricular tachycardia and/or ventricular fibrillation.

The patient was started on a procainamide drip and converted to normal sinus rhythm. He underwent an electrophysiology study, which demonstrated a single accessory pathway capable of conducting at rates of 250 beats/min located in the lateral wall of the left atrium. It was successfully ablated, resulting in normalization of his ECG.

The charge nurse in the emergency department (ED) calls to tell you that one of your patients, a 19-year-old man, has just presented with a three-hour history of continuous palpitations. She reports the patient’s pulse as 170 beats/min and adds that although he is awake and stable, he is complaining of chest discomfort and lightheadedness. The tachycardia began abruptly while the patient was playing basketball. Witnesses said he did not lose consciousness but did sit down, complaining of dizziness. The patient admits he thought he “was going to pass out” when he sat up. As you review the patient’s chart, you recall seeing him for palpitations approximately six months ago, at which time an ECG showed Wolf-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome with a left-sided accessory pathway. His history is remarkable for palpitations beginning at age 14, with two episodes of near-syncope. None of his episodes of palpitations has lasted as long as the current one, however. Medical history is remarkable for a tonsillectomy at age 7. Family history is positive for coronary artery disease and diabetes. The patient takes no medications and has no known drug allergies. He is a college student, drinks a six-pack of beer on weekends despite being under age, and tried marijuana once. He denies any other use of illegal, illicit, or performance-enhancing drugs. The review of systems is noncontributory. The physical exam reveals a thin, anxious male. His blood pressure is 98/66 mm Hg; pulse, 170 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; temperature, 99°F; and O2 saturation, 98% on 2L of oxygen. There is no jugular venous distention, and carotid upstrokes are rapid and brisk. The chest is clear to auscultation bilaterally with good excursion. The cardiac exam reveals a rapid, regular rate with no murmurs, gallops, or rubs. There are no extra heart sounds. The abdominal, peripheral, and neurologic exams are intact without focal signs. On arrival in the ED, you are handed an ECG, which shows: a ventricular rate of 174 beats/min; PR interval, not measured; QRS duration, 164 ms; QT/QTc interval, 302/513 ms; no P axis; R axis, –46°; and T axis, 118°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Abrupt Onset Palpitations

ANSWER

The ECG reveals a short PR interval (< 120 ms), a slurred upstroke (delta wave) of the initiation of the QRS complex indicating ventricular preexcitation, a broad QRS (> 110 ms) as a result of the delta wave, and secondary ST- and T-wave changes consistent with Wolf-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. The delta wave is an indicator of an electrical impulse that bypasses normal AV nodal conduction through one or more accessory pathways that allow direct antegrade conduction between the atria and ventricles.

If the delta wave is positive in lead V1, the accessory pathway is located between the left atrium and left ventricle. If the delta wave is negative in aVF, as indicated in this ECG, the accessory pathway can be further located to the lateral wall of the left atrium. This localization aids in estimating the location of the accessory pathway prior to electrophysiology study and ablation.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals a short PR interval (< 120 ms), a slurred upstroke (delta wave) of the initiation of the QRS complex indicating ventricular preexcitation, a broad QRS (> 110 ms) as a result of the delta wave, and secondary ST- and T-wave changes consistent with Wolf-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. The delta wave is an indicator of an electrical impulse that bypasses normal AV nodal conduction through one or more accessory pathways that allow direct antegrade conduction between the atria and ventricles.

If the delta wave is positive in lead V1, the accessory pathway is located between the left atrium and left ventricle. If the delta wave is negative in aVF, as indicated in this ECG, the accessory pathway can be further located to the lateral wall of the left atrium. This localization aids in estimating the location of the accessory pathway prior to electrophysiology study and ablation.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals a short PR interval (< 120 ms), a slurred upstroke (delta wave) of the initiation of the QRS complex indicating ventricular preexcitation, a broad QRS (> 110 ms) as a result of the delta wave, and secondary ST- and T-wave changes consistent with Wolf-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. The delta wave is an indicator of an electrical impulse that bypasses normal AV nodal conduction through one or more accessory pathways that allow direct antegrade conduction between the atria and ventricles.

If the delta wave is positive in lead V1, the accessory pathway is located between the left atrium and left ventricle. If the delta wave is negative in aVF, as indicated in this ECG, the accessory pathway can be further located to the lateral wall of the left atrium. This localization aids in estimating the location of the accessory pathway prior to electrophysiology study and ablation.

An 18-year-old man has palpitations that occur with variable frequency: sometimes several times per day, and often weeks without an occurrence. The onset is typically abrupt, lasting a few seconds to several minutes before abruptly terminating. He describes them as a “rapid fluttering” sensation in his chest with a “full feeling” in his throat. Associated symptoms include lightheadedness and chest discomfort. He denies chest pain. He had an episode of near-syncope at age 14 and another approximately four weeks ago; the latter prompted him to schedule an appointment in your clinic. He has not been ill recently and has no history to suggest hypovolemia or anemia as a contributing factor for his recent episode of near-syncope. Medical history is unremarkable, with the exception of tonsillectomy at age 7. He is not taking any medications and has no known drug allergies. Family history is positive for coronary artery disease in his father, which required revascularization at age 62, and diabetes in a grandparent. Social history reveals he is a full-time undergraduate student at a local junior college. He drinks approximately one six-pack of beer on weekends despite being under age, but denies use of illegal, illicit, or performance-enhancing drugs. The review of systems is noncontributory. The physical examination reveals a thin, healthy-appearing male in no distress. His blood pressure is 104/62 mm Hg; pulse, 66 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min. The patient is afebrile. The chest is clear to auscultation bilaterally with good excursion. The cardiac exam reveals a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, gallops, or extra heart sounds. There is no jugular venous distention or peripheral edema. The remainder of the physical exam shows no abnormalities or deficits. Despite the “normal” physical, you are concerned about the patient’s history of frequent palpitations and two previous episodes of near-syncope. You order an ECG, the results of which show: a ventricular rate of 66 beats/min; PR interval, 116 ms; QRS duration, 142 ms; QT/QTc interval, 456/478 ms; P axis, 0°; R axis, –7°; and T axis, 105°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Marathon Runner Needs Preoperative Work-Up

ANSWER

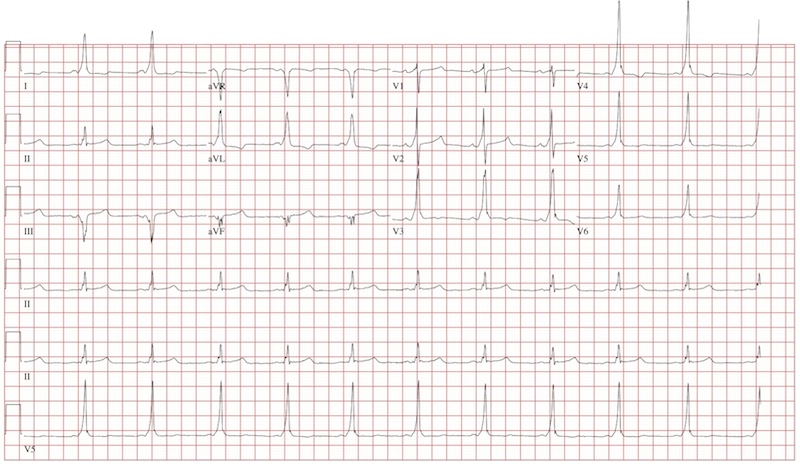

All measured intervals are within normal limits; there is a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave. There is no evidence of injury, ischemia, or infarct, and no atrial or ventricular hypertrophy. This is, in other words, a normal ECG—and is that of the author.

Perioperative ordering of ECGs based on patient age, in the absence of prior heart disease, remains controversial. In the majority of cases, identification of abnormal findings does not occur. However, as long as previously unknown anomalies are discovered, this practice will likely continue.

ANSWER

All measured intervals are within normal limits; there is a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave. There is no evidence of injury, ischemia, or infarct, and no atrial or ventricular hypertrophy. This is, in other words, a normal ECG—and is that of the author.

Perioperative ordering of ECGs based on patient age, in the absence of prior heart disease, remains controversial. In the majority of cases, identification of abnormal findings does not occur. However, as long as previously unknown anomalies are discovered, this practice will likely continue.

ANSWER

All measured intervals are within normal limits; there is a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave. There is no evidence of injury, ischemia, or infarct, and no atrial or ventricular hypertrophy. This is, in other words, a normal ECG—and is that of the author.

Perioperative ordering of ECGs based on patient age, in the absence of prior heart disease, remains controversial. In the majority of cases, identification of abnormal findings does not occur. However, as long as previously unknown anomalies are discovered, this practice will likely continue.

In celebration of his 50th birthday, a man with no prior medical problems decides to run a marathon. He has run a few 5K and 10K events in the past 10 years, and he completed a half-marathon five years ago. Approximately three weeks into his training schedule, he completes a five-mile run; the next morning, he notes significant pain in the medial compartment of the right knee. After resting for two days, he begins running again; however, the pain returns and does not resolve. The pain remains localized to the medial right knee and is exacerbated by high-impact activities, such as climbing and descending stairs, as well as any movement requiring rotation or torque around the right knee. Despite the use of NSAIDs and icing, the pain does not resolve, and the patient presents to the sports medicine clinic. Medical history is negative for any previous knee trauma. Current medications include ibuprofen 800 mg four times daily. There are no known drug allergies. Family history is positive for adult-onset diabetes and valvular heart disease in both sets of grandparents. Both parents are alive and well. Social history shows no history of tobacco or illicit drug use. The patient reports having an occasional glass of wine with dinner. A 12-point review of systems is negative, with the exception of corrective lenses for presbyopia. Physical examination reveals a white man in no distress. The blood pressure is 108/66 mm Hg; pulse, 68 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; and temperature, 98°F. The lungs are clear; the cardiac exam reveals a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. There is no jugular venous distention or peripheral edema. The abdominal exam is benign, and there are no neurologic deficits. Examination of the knee reveals very minimal swelling of the joint. The patient is able to fully extend the joint; however, flexion beyond 130° results in severe pain. The knee is stable to varus and valgus stress testing and to Lachman testing. There is fairly significant medial pain with any of the McMurray’s test maneuvers. An MRI of the right knee shows a significant tear in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus, as well as some chondromalacia of the patellofemoral joint. Given the patient’s age, an ECG is ordered as part of the preoperative workup for surgical repair of the right knee. The ECG reveals the following: pulse, 68 beats/min; PR interval, 156 ms; QRS duration, 88 ms; QT/QTc interval, 380/404 ms; P axis, 53°; R axis, –5°; and T axis, 18°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

A History of Palpitations and Dizziness

ANSWER

This ECG is diagnostic for Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. Criteria for WPW syndrome include a normal P wave with a PR interval generally (but not always) of 0.12 sec (120 ms) or greater, initial slurring of the QRS (delta wave), a wide QRS interval > 0.10 sec (100 ms), and secondary ST/T wave changes.

In WPW syndrome, one (or multiple) accessory pathway between the atria and ventricles allows conduction impulses to bypass the atrioventricular node and activate the ventricles prematurely. This premature ventricular activation is responsible for the initial slurring of the QRS complex and produces the characteristic delta wave. The presence of an accessory pathway allows a reentrant tachycardia circuit to occur and is the source of this patient’s palpitations. Subsequent electrophysiology studies identified a single left lateral accessory pathway.

ANSWER

This ECG is diagnostic for Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. Criteria for WPW syndrome include a normal P wave with a PR interval generally (but not always) of 0.12 sec (120 ms) or greater, initial slurring of the QRS (delta wave), a wide QRS interval > 0.10 sec (100 ms), and secondary ST/T wave changes.

In WPW syndrome, one (or multiple) accessory pathway between the atria and ventricles allows conduction impulses to bypass the atrioventricular node and activate the ventricles prematurely. This premature ventricular activation is responsible for the initial slurring of the QRS complex and produces the characteristic delta wave. The presence of an accessory pathway allows a reentrant tachycardia circuit to occur and is the source of this patient’s palpitations. Subsequent electrophysiology studies identified a single left lateral accessory pathway.

ANSWER

This ECG is diagnostic for Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. Criteria for WPW syndrome include a normal P wave with a PR interval generally (but not always) of 0.12 sec (120 ms) or greater, initial slurring of the QRS (delta wave), a wide QRS interval > 0.10 sec (100 ms), and secondary ST/T wave changes.

In WPW syndrome, one (or multiple) accessory pathway between the atria and ventricles allows conduction impulses to bypass the atrioventricular node and activate the ventricles prematurely. This premature ventricular activation is responsible for the initial slurring of the QRS complex and produces the characteristic delta wave. The presence of an accessory pathway allows a reentrant tachycardia circuit to occur and is the source of this patient’s palpitations. Subsequent electrophysiology studies identified a single left lateral accessory pathway.

A 20-year-old woman is involved in a motor vehicle accident. Her car was hit from behind while stopped at a light, with the force of impact sufficient to deploy the airbags in both vehicles. When the paramedics arrive, the patient is conscious and responsive but is found to have a rapid pulse (approximately 170 beats/min). During transport to the hospital, her tachycardia abruptly terminates and sinus rhythm returns at rates between 80 and 90 beats/min. In the emergency department, the patient’s physical examination and x-rays reveal no injuries. Review of the rhythm strips from the paramedics in the field shows a narrow complex tachycardia at a rate of 176 beats/min. When interviewed, the patient reveals a history of palpitations, lasting from five minutes up to two hours, over the past several years. When they occur, she says, she gets dizzy and feels a pounding sensation in her chest, but she has never had chest pain or syncope. She cannot identify any specific trigger that initiates her palpitations, but has noticed that if she holds her breath and bears down (Valsalva maneuver), her palpitations will sometimes stop. Her medical history is positive for mild asthma and an allergy to peanuts. She is taking no medications and denies tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drug use. Family history is remarkable for hypertension (father) and type 2 diabetes (mother). She is the oldest of three children, and one of her sisters experiences similar bouts of palpitations. A 14-point review of systems is negative. She denies she could be pregnant; she is currently menstruating. She is 61” tall, weighs 110 lb, and is of small stature and body habitus. She is in no acute distress. Her blood pressure is 110/72 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min and regular; and respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min. The physical exam is unremarkable, with the exception of abrasions on her hands and left forearm. Given the documentation of a tachycardia by the paramedics in the field and a history of recurring palpitations, an ECG is obtained, which reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 77 beats/min; PR interval, 128 ms; QRS duration, 116 ms; QT/QTc interval, 416/470 ms; P axis, 61°; R axis, 98°; and T axis, 5°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?