User login

Role of Yoga Across the Cancer Care Continuum: From Diagnosis Through Survivorship

From the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX (Drs. Narayanan, Lopez, Chaoul, Liu, Milbury, and Cohen, and Ms. Mallaiah); the University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler (Dr. Meegada); and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, TX (Ms. Francisco).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the effects of yoga as an adjunct supportive care modality alongside conventional cancer treatment on quality of life (QOL), physical and mental health outcomes, and physiological and biological measures of cancer survivors.

- Methods: Nonsystematic review of the literature.

- Results: Yoga therapy, one of the most frequently used mind-body modalities, has been studied extensively in cancer survivors (from the time of diagnosis through long-term recovery). Yoga affects human physiology on multiple levels, including psychological outcomes, immune and endocrine function, and cardiovascular parameters, as well as multiple areas of QOL. It has been found to reduce psychological stress and fatigue and improve QOL in cancer patients and survivors. Yoga has also been used to manage symptoms such as arthralgia, fatigue, and insomnia. In addition, yoga offers benefits not only for cancer survivors but also for their caregivers.

- Conclusion: As part of an integrative, evidence-informed approach to cancer care, yoga may provide benefits that support the health of cancer survivors and caregivers.

Keywords: fatigue; cancer; proinflammatory cytokines; integrative; mind-body practices; meditation; DNA damage; stress; psychoneuro-immunoendocrine axis; lymphedema; insomnia.

A diagnosis of cancer and adverse effects related to its treatment may have negative effects on quality of life (QOL), contributing to emotional and physical distress in patients and caregivers. Many patients express an interest in pursuing nonpharmacological options, alone or as an adjunct to conventional therapy, to help manage symptoms. The use of complementary medicine approaches to health, including nonpharmacological approaches to symptom management, is highest among individuals with cancer.1 According to a published expert consensus, integrative oncology is defined as a “patient-centered, evidence-informed field of cancer care that utilizes mind and body practices, natural products, and/or lifestyle modifications from different traditions alongside conventional cancer treatments. Integrative oncology aims to optimize health, QOL, and clinical outcomes across the cancer care continuum and to empower people to prevent cancer and become active participants before, during, and beyond cancer treatment.”2 A key component of this definition, often misunderstood in the field of oncology, is that these modalities and treatments are used alongside conventional cancer treatments and not as an alternative. In an attempt to meet patients’ needs and appropriately use these approaches, integrative oncology programs are now part of most cancer centers in the United States.3-6

Because of their overall safety, mind-body therapies are commonly used by patients and recommended by clinicians. Mind-body therapies include yoga, tai chi, qigong, meditation, and relaxation. Expressive arts such as journaling and music, art, and dance therapies also fall in the mind-body category.7 Yoga is a movement-based mind-body practice that focuses on synchronizing body, breath, and mind. Yoga has been increasingly used by patients for health benefits,8 and numerous studies have evaluated yoga as a complementary intervention for individuals with cancer.9-14 Here, we review the physiological basis of yoga in oncology and the effects of yoga on biological processes, QOL, and symptoms during and after cancer treatment.

Physiological Basis

Many patients may use mind-body programs such as yoga to help manage the psychological and physiological consequences of unmanaged chronic stress and improve their overall QOL. The central nervous system, endocrine system, and immune system influence and interact with each other in a complex manner in response to chronic stress.15,16 In a stressful situation, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) are activated. HPA axis stimulation leads to adrenocorticotrophic hormone production by the pituitary gland, which releases glucocorticoid hormones. SNS axis stimulation leads to epinephrine and norepinephrine production by the adrenal gland.17,18 Recently, studies have explored modulation of signal transduction between the nervous and immune systems and how that may impact tumor growth and metastasis.19 Multiple studies, controlled for prognosis, disease stage, and other factors, have shown that patients experiencing more distress or higher levels of depressive symptoms do not live as long as their counterparts with low distress or depression levels.20 Both the meditative and physical components of yoga can lead to enhanced relaxation, reduced SNS activation, and greater parasympathetic tone, countering the negative physiological effects of chronic stress. The effects of yoga on the HPA axis and SNS, proinflammatory cytokines, immune function, and DNA damage are discussed below.

Biological Processes

Nervous System

The effects of yoga and other forms of meditation on brain functions have been established through several studies. Yoga seems to influence basal ganglia function by improving circuits that are involved in complex cognitive functions, motor coordination, and somatosensory and emotional processes.21,22 Additionally, changes in neurotransmitter levels have been observed after yoga practice. For instance, in a 12-week yoga intervention in healthy subjects, increased levels of thalamic gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the yoga group were reported to have a positive correlation with improved mood and decreased anxiety compared with a group who did metabolically matched walking exercise.23 Levels of GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, are decreased in conditions such as anxiety, depression, and epilepsy.24 Yoga therapy has been shown to improve symptoms of mood disorders and epilepsy, which leads to the hypothesis that the mechanism driving the benefits of yoga may work through stimulation of vagal efferents and an increase in GABA-mediated cortical-inhibitory tone.24,25

HPA Axis

Stress activates the HPA/SNS axis, which releases hormones such as cortisol and norepinephrine. These hormones may play a role in angiogenesis, inflammation, immune suppression, and other physiological functions, and may even reduce the effect of chemotherapeutic agents.26,27 Regular yoga practice has been shown to reduce SNS and HPA axis activity, most likely by increasing parasympathetic dominance through vagal stimulation, as demonstrated through increases in heart rate variability.28 One indicator of HPA axis dysregulation, diurnal salivary cortisol rhythm, was shown to predict survival in patients with advanced breast and renal cancer.29-33 Yoga has been shown to lead to less cortisol dysregulation due to radiotherapy and to reductions in mean cortisol levels and early morning cortisol levels in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy.34 This lends support to the hypothesis that yoga helps restore HPA axis balance.

Proinflammatory Cytokines

Cancer patients tend to have increased levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interferon-γ, and C-reactive protein. This increase in inflammation is associated with worse outcomes in cancer.35 This association becomes highly relevant because the effect of inflammation on host cells in the tumor microenvironment is connected to disease progression.26 Inflammatory cytokines are also implicated in cancer-related symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, peripheral neuropathy, and sleep disturbances.36

Yoga is known to reduce stress and may directly or indirectly decrease inflammatory cytokines. A randomized clinical trial of a 12-week hatha yoga intervention among breast cancer survivors demonstrated decreases in IL-6, IL-1β, TNF, corticotropin-releasing factor, and cognitive complaints in the yoga group compared with those in the standard care group after 3 months.37,38 Furthermore, Carlson et al showed that, after mindfulness-based stress reduction involving a combination of gentle yoga, meditation techniques, and relaxation exercises, breast and prostate cancer patients had reduced levels of proinflammatory cytokines and cortisol.39 These reductions translated into patients reporting decreased stress levels and enhanced QOL.

Immune Function

The effects of yoga practice on the immune system have been studied in both healthy individuals and individuals with cancer. The effects on T and B lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, and other immune effector cells demonstrate that meditation and yoga have beneficial effects on immune activity.40 Hormones such as catecholamines and glucocorticoids are thought to influence the availability and function of NK cells, and, as noted above, yoga has been shown to modulate stress hormones and lead to reduced immune suppression in patients with early-stage breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy.41 Additional evidence supports the ability of yoga to reduce immune suppression in the postsurgical setting, with no observed decrease in NK cell percentage after surgery for those in a yoga group compared with a control group.42 This finding is relevant to patients undergoing surgical management of their cancer and highlights the impact of yoga on the immune system.

DNA Damage

Radiation damages DNA in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients undergoing treatment.43,44 This damage is significant in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy.45 Stress additionally causes DNA damage46 and is correlated to impaired DNA repair capacity.47,48 In a study conducted by Banerjee et al, breast cancer patients were randomly assigned to a yoga group or a supportive therapy group for 6 weeks during radiotherapy.49 Prior to the intervention, patients in the study had significant genomic instability. After treatment, patients in the yoga group experienced not only a significant reduction in anxiety and depression levels, but also a reduction in DNA damage due to radiotherapy.

Yoga in Quality of Life and Symptom Management

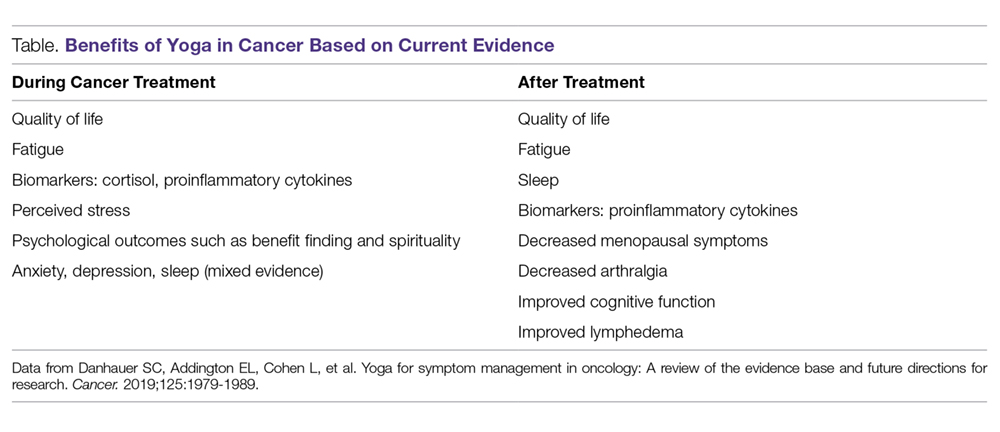

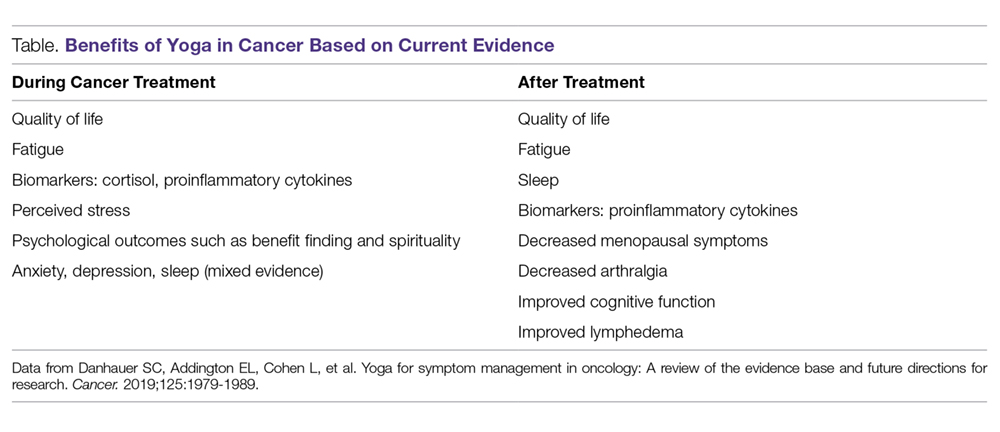

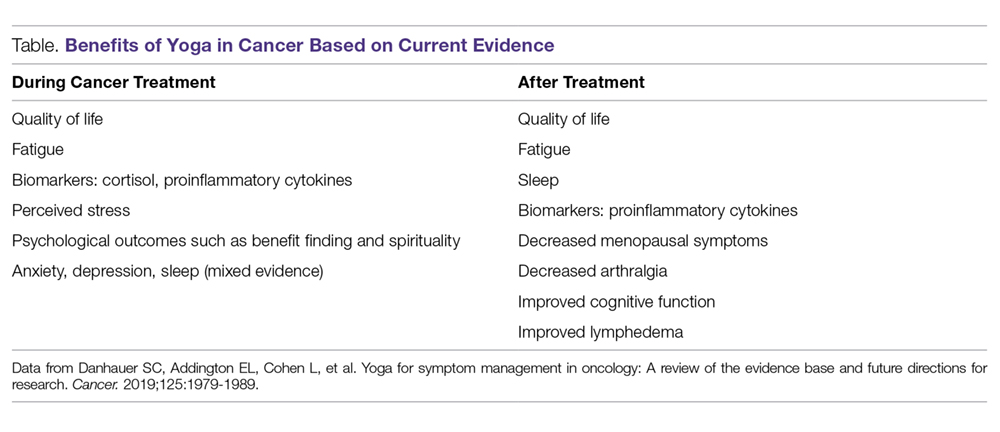

There is evidence showing that yoga therapy improves multiple aspects of QOL, including physical functioning, emotional health outcomes, and the symptoms cancer patients may experience, such as sleep disturbances, fatigue, and pain. Danhauer et al systematically reviewed both nonrandomized trials and randomized controlled trials involving yoga during cancer treatment.50 They found that yoga improved depression and anxiety as well as sleep and fatigue. Benefits of yoga in cancer based on randomized controlled trials are summarized in the Table. The role of yoga in improving QOL and managing symptoms patients experience during and after treatment is discussed in the following sections.

Quality of Life

Danhauer et al’s systematic review of trials involving yoga during cancer treatment found that yoga improved multiple aspects of QOL.50 For example, yoga has been shown to improve QOL in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. In a study by Chandwani et al, yoga (60-minute sessions twice a week for 6 weeks) was associated with better general health perception and physical functioning scores as well as greater benefit finding, or finding meaning in their experience, after radiotherapy compared with a wait-list group.51 The yoga group had an increase in intrusive thoughts, believed to be due to a more thorough processing of the cancer experience, which helps to improve patients’ outlook on life.52 The benefits of yoga extend beyond psychological measures during radiation treatment. Yoga was found to increase physical functioning compared with stretching in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy.53

Cognitive Function

Cancer-related cognitive impairment commonly occurs during cancer treatments (eg, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, hormone therapy) and persists for months or years in survivors.54 Impairment of memory, executive function, attention, and concentration are commonly reported. In a trial of a combined hatha and restorative yoga program called Yoga for Cancer Survivors (YOCAS), which was designed by researchers at the University of Rochester, patients in the yoga arm had less memory difficulty than did patients in the standard care arm.55 However, the primary aim of the trial was to treat insomnia, so this secondary outcome needs to be interpreted with caution. Deficits in attention, memory, and executive function are often seen in cancer-related cognitive impairment, and the meditative aspect of yoga may have behavioral and neurophysical benefits that could improve cognitive functions.56 More evidence is needed to understand the role of yoga in improving cognitive functioning.

Emotional Health

Psychosocial stress is high among breast cancer patients and survivors.57,58 This causes circadian rhythm and cortisol regulation abnormalities, which are reported in women with breast cancer.59-64 Yoga is known to help stress and psychosocial and physical functioning in patients with cancer.65 Yoga was also shown to be equivalent to cognitive behavioral therapy in stress management in a population of patients without cancer.66 Daily yoga sessions lasting 60 minutes were shown to reduce reactive anxiety and trait anxiety in early-stage breast cancer patients undergoing conventional radiotherapy and chemotherapy compared with patients receiving supportive therapy, highlighting the role of yoga in managing anxiety related to treatment.67 In a study done by Culos-Reed et al, 20 cancer survivors who did 75 minutes of yoga per week for 7 weeks were compared with 18 cancer survivors who served as a control group.68 The intervention group reported significant improvement in emotional well-being, depression, concentration, and mood disturbances. In a longitudinal study by Mackenzie et al, 66 cancer survivors completed a 7-week yoga program and were assessed at baseline, immediately after the final yoga session, and at 3 and 6 months after the final session.69 Participants had significantly improved energy levels and affect. They also had moderate improvement in mindfulness and a moderate decrease in stress. Breast cancer patients who underwent restorative yoga sessions found improvements in mental health, depression, positive affect, and spirituality (peace/meaning).70 This was more pronounced in women with higher negative affect and lower emotional well-being at baseline. In a study of patients with ovarian cancer receiving chemotherapy, patients were instructed to perform up to 15-minute sessions including awareness, body movement, and breathing.71 Even with just 1 session of yoga intervention, patients experienced decreased anxiety.

Fatigue

Studies on yoga show improvement in fatigue both during and after treatment. In breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, yoga was shown to benefit cognitive fatigue.72 Older cancer survivors also seem to benefit from yoga interventions.73 In a trial of a DVD-based yoga program, the benefits of yoga were similar to those of strengthening exercises, and both interventions helped decrease fatigue and improve QOL during the first year after diagnosis in early-stage breast cancer patients with cancer-related fatigue.74 Bower et al also showed that, for breast cancer survivors experiencing persistent chronic fatigue, a targeted yoga intervention led to significant improvements in fatigue and vigor over a 3-month follow-up compared with controls.75 Fatigue is commonly seen in breast cancer patients who are receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. In a study by Taso et al, women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy were assigned to 60-minute yoga sessions incorporating Anusara yoga, gentle stretching, and relaxation twice a week for 8 weeks.76 By week 4, patients with low pretest fatigue in the yoga group experienced a reduction in fatigue. By week 8, all patients in the yoga group experienced a reduction in fatigue. Four weeks after the yoga intervention, patients in the group maintained the reduction in fatigue. This study shows the feasibility of an 8-week yoga program for women undergoing breast cancer therapy by improving fatigue. Yoga recently was added to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for management of cancer-related fatigue (level 1 evidence).77 However, the evidence was based on studies in women with breast cancer and survivors; therefore, more studies are needed in men and women with other cancers.

Surgical Setting/Postoperative Distress

Distress surrounding surgery in patients with breast cancer can impact postoperative outcomes. Yoga interventions, including breathing exercises, regulated breathing, and yogic relaxation techniques, improved several postsurgical measures such as length of hospital stay, drain retention, and suture removal.78 In this study, patients who practiced yoga also experienced a decrease in plasma TNF and better wound healing. Symptoms of anxiety and distress that occur preoperatively can lead to impaired immune function in addition to decreased QOL. In a study of yoga in early-stage breast cancer patients undergoing surgery, the benefit of yoga was seen not only with stress reduction but also with immune enhancement.42

Yoga has been shown to help alleviate acute pain and distress in women undergoing major surgery for gynecological cancer. A regimen of 3 15-minute sessions of yoga, including awareness meditation, coordination of breath with movement, and relaxation breathing, was shown to reduce acute pain and distress in such patients in an inpatient setting.79

Menopausal Symptoms

Breast cancer survivors have more severe menopausal symptoms compared with women without cancer.80,81 Hot flashes cause sleep disturbances and worsen fatigue and QOL.82 Tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors significantly worsen menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes.81 Carson et al conducted a study of yoga that included postures, breathing techniques, didactic presentations, and group discussions.83 The yoga awareness regimen consisted of 8 weekly 120-minute group classes. Patients in the yoga arm had statistically significant improvements in the frequency, severity, and number of hot flashes. There were also improvements in arthralgia (joint pain), fatigue, sleep disturbance, vigor, and acceptance.

Arthralgia

Joint pain can be a major side effect that interferes with daily functions and activities in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors who receive aromatase inhibitor therapy.84 Arthralgia is reported in up to 50% of patients treated with aromatase inhibitors.84,85 It can affect functional status and lead to discontinuation of aromatase inhibitor therapy, jeopardizing clinical outcomes.86 Yoga as a complementary therapy has been shown to improve conditions such as low back pain87 and knee osteoarthritis88 in patients who do not have cancer. In a single-arm pilot trial by Galantino et al, breast cancer patients with aromatase inhibitor–related joint pain were provided with twice-weekly yoga sessions for 8 weeks. There were statistically significant improvements in balance, flexibility, pain severity, and health-related QOL.89 As noted above, improvement in arthralgia was also found in the study conducted by Carson et al.83

Insomnia

Insomnia is common among cancer patients and survivors90,91 and leads to increased fatigue and depression, decreased adherence to cancer treatments, and poor physical function and QOL.90-92 Management of insomnia consists of pharmacologic therapies such as benzodiazepines93,94 and nonpharmacologic options such as cognitive behavioral therapy.95

The first study of yoga found to improve sleep quality was conducted at MD Anderson Cancer Center in lymphoma patients.96 The effects of Tibetan yoga practices incorporating controlled breathing and visualization, mindfulness techniques, and low-impact postures were studied. Patients in the Tibetan yoga group had better subjective sleep quality, faster sleep latency, longer sleep duration, and less use of sleep medications. Mustian et al conducted a large yoga study in cancer survivors in which patients reporting chronic sleep disturbances were randomly assigned to the YOCAS program, which consisted of pranayama (breath control), 16 gentle hatha and restorative yoga postures, and meditation, or to usual care.92 The study reported improvements in global sleep quality, subjective sleep quality, actigraphy measures (wake after sleep onset, sleep efficiency), daytime dysfunction, and use of sleep medication after the yoga intervention compared with participants who received standard care.

Yoga to Address Other Symptoms

There is preliminary evidence supporting yoga as an integrative therapy for other symptoms unique to cancer survivors. For example, in head and neck cancer survivors, soft tissue damage involving the jaw, neck, shoulders, and chest results in swallowing issues, trismus, and aspiration, which are more pronounced in patients treated with conventional radiotherapy than in those treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy.97 Some late effects of radiotherapy for head and neck cancer—such as pain, anxiety, and impaired shoulder function—were shown to be improved through the practice of hatha yoga in 1 study.98 Similarly, in a randomized controlled pilot study of patients with stage I to III breast cancer 6 months after treatment, participants in an 8-week yoga program experienced a reduction in arm induration and improvement in a QOL subscale of lymphedema symptoms. However, more evidence is needed to support the use of yoga as a therapeutic measure for breast cancer lymphedema.99,100

Yoga for Caregivers

Along with cancer patients, caregivers face psychological and physical burdens as well as deterioration in their QOL. Caregivers tend to report clinical levels of anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and fatigue and have similar or in fact higher levels than those of the patients for whom they are caring.101,102 Yoga has been found to help caregivers of patients with cancer. Recently, MD Anderson researchers conducted a trial in patients with high-grade glioma and their caregivers as dyads.103,104 Each dyad attended 2 or 3 60-minute weekly Vivekananda yoga sessions involving breathing exercises, physical exercises, relaxation, and meditation. The researchers found that the yoga program was safe, feasible, acceptable, and subjectively useful for patients with high-grade glioma and their caregivers. Preliminary evidence of QOL improvement for both patients and caregivers was noted. An improvement in QOL was also demonstrated in another preliminary study of yoga in patients undergoing thoracic radiotherapy and their caregivers.105

Another study by the group at MD Anderson evaluated a couple-based Tibetan yoga program that emphasized breathing exercises, gentle movements, guided visualizations, and emotional connectedness during radiotherapy for lung cancer.106 This study included 10 patient‐caregiver dyads and found the program to be feasible, safe, and acceptable. The researchers also found preliminary evidence of improved QOL by the end of radiotherapy relative to baseline—specifically in the areas of spiritual well‐being for patients, fatigue for caregivers, and sleep disturbances and mental health issues such as anxiety and depressive symptoms for both patients and caregivers. This is noteworthy, as QOL typically deteriorates during the course of radiotherapy, and the yoga program was able to buffer these changes.

Conclusion

Yoga therapy has been used successfully as an adjunct modality to improve QOL and cancer-related symptoms. As a part of an integrative medicine approach, yoga is commonly recommended for patients undergoing cancer treatment. Danhauer et al reviewed randomized controlled trials during and after treatment and concluded that the evidence is clearly positive for QOL, fatigue, and perceived stress.107 Results are less consistent but supportive for psychosocial outcomes such as benefit finding and spirituality. Evidence is mixed for sleep, anxiety, and depression. Post-treatment studies demonstrate improvements in fatigue, sleep, and multiple QOL domains. Yoga has been included in NCCN guidelines for fatigue management. Yoga, if approved by a physician, is also included among the behavioral therapies for anticipatory emesis and prevention and treatment of nausea in the recent update of the NCCN guidelines.108 The Society for Integrative Oncology guidelines include yoga for anxiety/stress reduction as a part of integrative treatment in breast cancer patients during and after therapy, which was endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.109

Because of the strong evidence for its benefits and a low side-effect profile, yoga is offered in group-class settings for patients during and after treatment and/or for caregivers in our institution. We often prescribe yoga as a therapeutic modality for selected groups of patients in our clinical practice. However, some patients may have restrictions after surgery that must be considered. In general, yoga has an excellent safety profile, the evidence base is strong, and we recommend that yoga therapy should be part of the standard of care as an integrative approach for patients with cancer undergoing active treatment as well as for cancer survivors and caregivers.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank Bryan Tutt for providing editorial assistance.

Corresponding author: Santhosshi Narayanan, MD, Department of Palliative, Rehabilitation, and Integrative Medicine, Unit 1414, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1400 Pressler St., Houston, TX 77030; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Reports. 2008;(12):1-23.

2. Witt CM, Balneaves LG, Cardoso MJ, et al. A comprehensive definition for integrative oncology. NCI Monographs. 2017;2017(52):3-8.

3. Brauer JA, El Sehamy A, Metz JM, Mao JJ. Complementary and alternative medicine and supportive care at leading cancer centers: a systematic analysis of websites. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:183-186.

4. Lopez G, McQuade J, Cohen L, et al. Integrative oncology physician consultations at a comprehensive cancer center: analysis of demographic, clinical and patient reported outcomes. J Cancer. 2017;8:395-402.

5. Latte-Naor S, Mao JJ. Putting integrative oncology into practice: concepts and approaches. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:7-14.

6. Richardson MA, Sanders T, Palmer JL, et al. Complementary/alternative medicine use in a comprehensive cancer center and the implications for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2505-2514.

7. Chaoul A, Milbury K, Sood AK, et al. Mind-body practices in cancer care. Curr Oncol Rep. 2014;16:417.

8. Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, et al. Prevalence and patterns of adult yoga use in the United States: results of a national survey. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10:44-49.

9. Smith KB, Pukall CF. An evidence-based review of yoga as a complementary intervention for patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:465-475.

10. Buffart LM, van Uffelen JG, Riphagen II, et al. Physical and psychosocial benefits of yoga in cancer patients and survivors, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:559.

11. Cramer H, Lange S, Klose P, et al. Yoga for breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:412.

12. Felbel S, Meerpohl JJ, Monsef I, et al. Yoga in addition to standard care for patients with haematological malignancies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(6):CD010146.

13. Greenlee H, Balneaves LG, Carlson LE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the use of integrative therapies as supportive care in patients treated for breast cancer. NCI Monographs. 2014;2014:346-358.

14. Sharma M, Haider T, Knowlden AP. Yoga as an alternative and complementary treatment for cancer: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:870-875.

15. Kordon C, Bihoreau C. Integrated communication between the nervous, endocrine and immune systems. Horm Res. 1989;31:100-104.

16. Gonzalez-Diaz SN, Arias-Cruz A, Elizondo-Villarreal B, Monge-Ortega OP. Psychoneuroimmunoendocrinology: clinical implications. World Allergy Organ J. 2017;10:19.

17. Godoy LD, Rossignoli MT, Delfino-Pereira P, et al. A comprehensive overview on stress neurobiology: basic concepts and clinical implications. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:127.

18. Goldstein DS. Adrenal responses to stress. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30:1433-1440.

19. Cole SW, Nagaraja AS, Lutgendorf SK, et al. Sympathetic nervous system regulation of the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:563-567.

20. Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2009;115:5349-5361.

21. Arsalidou M, Duerden EG, Taylor MJ. The centre of the brain: topographical model of motor, cognitive, affective, and somatosensory functions of the basal ganglia. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34:3031-3054.

22. Gard T, Taquet M, Dixit R, et al. Greater widespread functional connectivity of the caudate in older adults who practice kripalu yoga and vipassana meditation than in controls. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:137.

23. Streeter CC, Gerbarg PL, Saper RB, et al. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78:571-579.

24. Brambilla P, Perez J, Barale F, et al. GABAergic dysfunction in mood disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:721-737.

25. Streeter CC, Gerbarg PL, Saper RB, et al. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78:571-579.

26. Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK. Biobehavioral factors and cancer progression: physiological pathways and mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:724-730.

27. Armaiz-Pena GN, Cole SW, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK. Neuroendocrine influences on cancer progression. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):S19-S25.

28. Tyagi A, Cohen M. Yoga and heart rate variability: A comprehensive review of the literature. Int J Yoga. 2016;9:97-113.

29. Sephton SE, Lush E, Dedert EA, et al. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of lung cancer survival. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30 (suppl):S163-S170.

30. Sephton SE, Sapolsky RM, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:994-1000.

31. Arafah BM, Nishiyama FJ, Tlaygeh H, Hejal R. Measurement of salivary cortisol concentration in the assessment of adrenal function in critically ill subjects: a surrogate marker of the circulating free cortisol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2965-2971.

32. Cohen L, de Moor C, Devine D, et al. Endocrine levels at the start of treatment are associated with subsequent psychological adjustment in cancer patients with metastatic disease. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:951-958.

33. Cohen L, Cole SW, Sood AK, et al. Depressive symptoms and cortisol rhythmicity predict survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma: role of inflammatory signaling. PloS One. 2012;7:e42324.

34. Vadiraja HS, Raghavendra RM, Nagarathna R, et al. Effects of a yoga program on cortisol rhythm and mood states in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8:37-46.

35. Wu Y, Antony S, Meitzler JL, Doroshow JH. Molecular mechanisms underlying chronic inflammation-associated cancers. Cancer Lett. 2014;345:164-173.

36. Bower JE, Lamkin DM. Inflammation and cancer-related fatigue: mechanisms, contributing factors, and treatment implications. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):S48-S57.

37. Derry HM, Jaremka LM, Bennett JM, et al. Yoga and self-reported cognitive problems in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2015;24:958-966.

38. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Christian L, Preston H, et al. Stress, inflammation, and yoga practice. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:113-121.

39. Carlson LE, Speca M, Faris P, Patel KD. One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:1038-1049.

40. Infante JR, Peran F, Rayo JI, et al. Levels of immune cells in transcendental meditation practitioners. Int J Yoga. 2014;7:147-151.

41. Rao RM, Telles S, Nagendra HR, et al. Effects of yoga on natural killer cell counts in early breast cancer patients undergoing conventional treatment. Comment to: recreational music-making modulates natural killer cell activity, cytokines, and mood states in corporate employees Masatada Wachi, Masahiro Koyama, Masanori Utsuyama, Barry B. Bittman, Masanobu Kitagawa, Katsuiku Hirokawa Med Sci Monit, 2007; 13(2): CR57-70. Med Sci Monit. 2008;14:LE3-4.

42. Rao RM, Nagendra HR, Raghuram N, et al. Influence of yoga on mood states, distress, quality of life and immune outcomes in early stage breast cancer patients undergoing surgery. Int J Yoga. 2008;1:11-20.

43. Mozdarani H, Mansouri Z, Haeri SA. Cytogenetic radiosensitivity of g0-lymphocytes of breast and esophageal cancer patients as determined by micronucleus assay. J Radiat Res. 2005;46:111-116.

44. Scott D, Barber JB, Levine EL, et al. Radiation-induced micronucleus induction in lymphocytes identifies a high frequency of radiosensitive cases among breast cancer patients: a test for predisposition? Br J Cancer. 1998;77:614-620.

45. Banerjee B, Sharma S, Hegde S, Hande MP. Analysis of telomere damage by fluorescence in situ hybridisation on micronuclei in lymphocytes of breast carcinoma patients after radiotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107:25-31.

46. Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17312-17315.

47. Glaser R, Thorn BE, Tarr KL, et al. Effects of stress on methyltransferase synthesis: an important DNA repair enzyme. Health Psychol. 1985;4:403-412.

48. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Stephens RE, Lipetz PD, et al. Distress and DNA repair in human lymphocytes. J Behav Med. 1985;8:311-320.

49. Banerjee B, Vadiraj HS, Ram A, et al. Effects of an integrated yoga program in modulating psychological stress and radiation-induced genotoxic stress in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6:242-250.

50. Danhauer SC, Addington EL, Sohl SJ, et al. Review of yoga therapy during cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1357-1372.

51. Chandwani KD, Thornton B, Perkins GH, et al. Yoga improves quality of life and benefit finding in women undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2010;8:43-55.

52. Ratcliff CG, Milbury K, Chandwani KD, et al. Examining mediators and moderators of yoga for women with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy. Integr Cancer Ther. 2016;15:250-262.

53. Chandwani KD, Perkins G, Nagendra HR, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of yoga in women with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1058-1065.

54. Janelsins MC, Kesler SR, Ahles TA, Morrow GR. Prevalence, mechanisms, and management of cancer-related cognitive impairment. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26:102-113.

55. Janelsins MC, Peppone LJ, Heckler CE, et al. YOCAS(c)(R) yoga reduces self-reported memory difficulty in cancer survivors in a nationwide randomized clinical trial: investigating relationships between memory and sleep. Integr Cancer Ther. 2016;15:263-271.

56. Biegler KA, Chaoul MA, Cohen L. Cancer, cognitive impairment, and meditation. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:18-26.

57. Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2297-2304.

58. Herschbach P, Keller M, Knight L, et al. Psychological problems of cancer patients: a cancer distress screening with a cancer-specific questionnaire. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:504-511.

59. Abercrombie HC, Giese-Davis J, Sephton S, et al. Flattened cortisol rhythms in metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:1082-1092.

60. Bower JE, Ganz PA, Aziz N. Altered cortisol response to psychologic stress in breast cancer survivors with persistent fatigue. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:277-280.

61. Bower JE, Ganz PA, Dickerson SS, et al. Diurnal cortisol rhythm and fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:92-100.

62. Giese-Davis J, Sephton SE, Abercrombie HC, et al. Repression and high anxiety are associated with aberrant diurnal cortisol rhythms in women with metastatic breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2004;23:645-650.

63. Giese-Davis J, DiMiceli S, Sephton S, Spiegel D. Emotional expression and diurnal cortisol slope in women with metastatic breast cancer in supportive-expressive group therapy: a preliminary study. Biol Psychol. 2006;73:190-198.

64. Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Smyth J, et al. Individual differences in the diurnal cycle of salivary free cortisol: a replication of flattened cycles for some individuals. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26:295-306.

65. Bower JE, Woolery A, Sternlieb B, Garet D. Yoga for cancer patients and survivors. Cancer Control. 2005;12:165-171.

66. Granath J, Ingvarsson S, von Thiele U, Lundberg U. Stress management: a randomized study of cognitive behavioural therapy and yoga. Cogn Behav Therap. 2006;35:3-10.

67. Rao MR, Raghuram N, Nagendra HR, et al. Anxiolytic effects of a yoga program in early breast cancer patients undergoing conventional treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17:1-8.

68. Culos-Reed SN, Carlson LE, Daroux LM, Hately-Aldous S. A pilot study of yoga for breast cancer survivors: physical and psychological benefits. Psychooncology. 2006;15:891-897.

69. Mackenzie MJ, Carlson LE, Ekkekakis P, et al. Affect and mindfulness as predictors of change in mood disturbance, stress symptoms, and quality of life in a community-based yoga program for cancer survivors. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:419496.

70. Danhauer SC, Mihalko SL, Russell GB, et al. Restorative yoga for women with breast cancer: findings from a randomized pilot study. Psycho-oncology. 2009;18:360-368.

71. Sohl SJ, Danhauer SC, Schnur JB, et al. Feasibility of a brief yoga intervention during chemotherapy for persistent or recurrent ovarian cancer. Explore (NY). 2012;8:197-198.

72. Stan DL, Croghan KA, Croghan IT, et al. Randomized pilot trial of yoga versus strengthening exercises in breast cancer survivors with cancer-related fatigue. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:4005-4015.

73. Sprod LK, Fernandez ID, Janelsins MC, et al. Effects of yoga on cancer-related fatigue and global side-effect burden in older cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6:8-14.

74. Wang G, Wang S, Jiang P, Zeng C. Effect of yoga on cancer related fatigue in breast cancer patients with chemotherapy [in Chinese]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2014;39:1077-1082.

75. Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, et al. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2012;118:3766-3775.

76. Taso CJ, Lin HS, Lin WL, et al. The effect of yoga exercise on improving depression, anxiety, and fatigue in women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Res. 2014;22:155-164.

77. Berger AM, Mooney K, Alvarez-Perez A, et al. Cancer-related fatigue, Version 2.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:1012-1039.

78. Rao RM, Nagendra HR, Raghuram N, et al. Influence of yoga on postoperative outcomes and wound healing in early operable breast cancer patients undergoing surgery. Int J Yoga. 2008;1:33-41.

79. Sohl SJ, Avis NE, Stanbery K, et al. Feasibility of a brief yoga intervention for improving acute pain and distress post gynecologic surgery. Int J Yoga Therap. 2016;26:43-47.

80. Gupta P, Sturdee DW, Palin SL, et al. Menopausal symptoms in women treated for breast cancer: the prevalence and severity of symptoms and their perceived effects on quality of life. Climacteric. 2006;9:49-58.

81. Canney PA, Hatton MQ. The prevalence of menopausal symptoms in patients treated for breast cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1994;6:297-299.

82. Carpenter JS, Johnson D, Wagner L, Andrykowski M. Hot flashes and related outcomes in breast cancer survivors and matched comparison women. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:E16-25.

83. Carson JW, Carson KM, Porter LS, et al. Yoga of Awareness program for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results from a randomized trial. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1301-1309.

84. Burstein HJ. Aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia syndrome. Breast. 2007;16:223-234.

85. Mao JJ, Stricker C, Bruner D, et al. Patterns and risk factors associated with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia among breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:3631-3639.

86. Presant CA, Bosserman L, Young T, et al. Aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia and/or bone pain: frequency and characterization in non-clinical trial patients. Clin Breast Cancer. 2007;7:775-778.

87. Saper RB, Sherman KJ, Cullum-Dugan D, et al. Yoga for chronic low back pain in a predominantly minority population: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Altern Ther Health Med. 2009;15:18-27.

88. Kolasinski SL, Garfinkel M, Tsai AG, et al. Iyengar yoga for treating symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knees: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:689-693.

89. Galantino ML, Desai K, Greene L, et al. Impact of yoga on functional outcomes in breast cancer survivors with aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgias. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:313-320.

90. Ancoli-Israel S. Recognition and treatment of sleep disturbances in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5864-5866.

91. Savard J, Ivers H, Villa J, et al. Natural course of insomnia comorbid with cancer: an 18-month longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3580-3586.

92. Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Janelsins M, et al. Multicenter, randomized controlled trial of yoga for sleep quality among cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3233-3241.

93. Moore TA, Berger AM, Dizona P. Sleep aid use during and following breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. Psychooncology. 2011;20:321-325.

94. Omvik S, Pallesen S, Bjorvatn B, et al. Patient characteristics and predictors of sleep medication use. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25:91-100.

95. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, et al. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:125-133.

96. Cohen L, Warneke C, Fouladi RT, et al. Psychological adjustment and sleep quality in a randomized trial of the effects of a Tibetan yoga intervention in patients with lymphoma. Cancer. 2004;100:2253-2260.

97. Kraaijenga SA, Oskam IM, van der Molen L, et al. Evaluation of long term (10-years+) dysphagia and trismus in patients treated with concurrent chemo-radiotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:787-794.

98. Adair M, Murphy B, Yarlagadda S, et al. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of tailored yoga in survivors of head and neck cancer: a pilot study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17:774-784.

99. Loudon A, Barnett T, Williams A. Yoga, breast cancer-related lymphoedema and well-being: A descriptive report of women’s participation in a clinical trial. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:4685-4695.

100. Loudon A, Barnett T, Piller N, et al. The effects of yoga on shoulder and spinal actions for women with breast cancer-related lymphoedema of the arm: A randomised controlled pilot study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:343.

101. Petruzzi A, Finocchiaro CY, Lamperti E, Salmaggi A. Living with a brain tumor: reaction profiles in patients and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1105-1111.

102. Pawl JD, Lee SY, Clark PC, Sherwood PR. Sleep characteristics of family caregivers of individuals with a primary malignant brain tumor. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:171-179.

103. Milbury K, Mallaiah S, Mahajan A, et al. Yoga program for high-grade glioma patients undergoing radiotherapy and their family caregivers. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17:332-336.

104. Milbury K, Li J, Weathers S-P, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a dyadic yoga program for glioma patients undergoing radiotherapy and their family caregivers. Neurooncol Pract. 2019;6:311-320.

105. Milbury K, Liao Z, Shannon V, et al. Dyadic yoga program for patients undergoing thoracic radiotherapy and their family caregivers: Results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2019;28:615-621.

106. Milbury K, Chaoul A, Engle R, et al. Couple-based Tibetan yoga program for lung cancer patients and their caregivers. Psychooncology. 2015;24:117-120.

107. Danhauer SC, Addington EL, Cohen L, et al. Yoga for symptom management in oncology: A review of the evidence base and future directions for research. Cancer. 2019;125:1979-1989.

108. National Comprehensive Cancer Center. Flash Update: NCCN Guidelines® and NCCN Compendium® for Antiemesis. NCCN website. Accessed August 29, 2019.

109. Lyman GH, Greenlee H, Bohlke K, et al. Integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment: ASCO endorsement of the SIO clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2647-2655.

From the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX (Drs. Narayanan, Lopez, Chaoul, Liu, Milbury, and Cohen, and Ms. Mallaiah); the University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler (Dr. Meegada); and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, TX (Ms. Francisco).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the effects of yoga as an adjunct supportive care modality alongside conventional cancer treatment on quality of life (QOL), physical and mental health outcomes, and physiological and biological measures of cancer survivors.

- Methods: Nonsystematic review of the literature.

- Results: Yoga therapy, one of the most frequently used mind-body modalities, has been studied extensively in cancer survivors (from the time of diagnosis through long-term recovery). Yoga affects human physiology on multiple levels, including psychological outcomes, immune and endocrine function, and cardiovascular parameters, as well as multiple areas of QOL. It has been found to reduce psychological stress and fatigue and improve QOL in cancer patients and survivors. Yoga has also been used to manage symptoms such as arthralgia, fatigue, and insomnia. In addition, yoga offers benefits not only for cancer survivors but also for their caregivers.

- Conclusion: As part of an integrative, evidence-informed approach to cancer care, yoga may provide benefits that support the health of cancer survivors and caregivers.

Keywords: fatigue; cancer; proinflammatory cytokines; integrative; mind-body practices; meditation; DNA damage; stress; psychoneuro-immunoendocrine axis; lymphedema; insomnia.

A diagnosis of cancer and adverse effects related to its treatment may have negative effects on quality of life (QOL), contributing to emotional and physical distress in patients and caregivers. Many patients express an interest in pursuing nonpharmacological options, alone or as an adjunct to conventional therapy, to help manage symptoms. The use of complementary medicine approaches to health, including nonpharmacological approaches to symptom management, is highest among individuals with cancer.1 According to a published expert consensus, integrative oncology is defined as a “patient-centered, evidence-informed field of cancer care that utilizes mind and body practices, natural products, and/or lifestyle modifications from different traditions alongside conventional cancer treatments. Integrative oncology aims to optimize health, QOL, and clinical outcomes across the cancer care continuum and to empower people to prevent cancer and become active participants before, during, and beyond cancer treatment.”2 A key component of this definition, often misunderstood in the field of oncology, is that these modalities and treatments are used alongside conventional cancer treatments and not as an alternative. In an attempt to meet patients’ needs and appropriately use these approaches, integrative oncology programs are now part of most cancer centers in the United States.3-6

Because of their overall safety, mind-body therapies are commonly used by patients and recommended by clinicians. Mind-body therapies include yoga, tai chi, qigong, meditation, and relaxation. Expressive arts such as journaling and music, art, and dance therapies also fall in the mind-body category.7 Yoga is a movement-based mind-body practice that focuses on synchronizing body, breath, and mind. Yoga has been increasingly used by patients for health benefits,8 and numerous studies have evaluated yoga as a complementary intervention for individuals with cancer.9-14 Here, we review the physiological basis of yoga in oncology and the effects of yoga on biological processes, QOL, and symptoms during and after cancer treatment.

Physiological Basis

Many patients may use mind-body programs such as yoga to help manage the psychological and physiological consequences of unmanaged chronic stress and improve their overall QOL. The central nervous system, endocrine system, and immune system influence and interact with each other in a complex manner in response to chronic stress.15,16 In a stressful situation, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) are activated. HPA axis stimulation leads to adrenocorticotrophic hormone production by the pituitary gland, which releases glucocorticoid hormones. SNS axis stimulation leads to epinephrine and norepinephrine production by the adrenal gland.17,18 Recently, studies have explored modulation of signal transduction between the nervous and immune systems and how that may impact tumor growth and metastasis.19 Multiple studies, controlled for prognosis, disease stage, and other factors, have shown that patients experiencing more distress or higher levels of depressive symptoms do not live as long as their counterparts with low distress or depression levels.20 Both the meditative and physical components of yoga can lead to enhanced relaxation, reduced SNS activation, and greater parasympathetic tone, countering the negative physiological effects of chronic stress. The effects of yoga on the HPA axis and SNS, proinflammatory cytokines, immune function, and DNA damage are discussed below.

Biological Processes

Nervous System

The effects of yoga and other forms of meditation on brain functions have been established through several studies. Yoga seems to influence basal ganglia function by improving circuits that are involved in complex cognitive functions, motor coordination, and somatosensory and emotional processes.21,22 Additionally, changes in neurotransmitter levels have been observed after yoga practice. For instance, in a 12-week yoga intervention in healthy subjects, increased levels of thalamic gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the yoga group were reported to have a positive correlation with improved mood and decreased anxiety compared with a group who did metabolically matched walking exercise.23 Levels of GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, are decreased in conditions such as anxiety, depression, and epilepsy.24 Yoga therapy has been shown to improve symptoms of mood disorders and epilepsy, which leads to the hypothesis that the mechanism driving the benefits of yoga may work through stimulation of vagal efferents and an increase in GABA-mediated cortical-inhibitory tone.24,25

HPA Axis

Stress activates the HPA/SNS axis, which releases hormones such as cortisol and norepinephrine. These hormones may play a role in angiogenesis, inflammation, immune suppression, and other physiological functions, and may even reduce the effect of chemotherapeutic agents.26,27 Regular yoga practice has been shown to reduce SNS and HPA axis activity, most likely by increasing parasympathetic dominance through vagal stimulation, as demonstrated through increases in heart rate variability.28 One indicator of HPA axis dysregulation, diurnal salivary cortisol rhythm, was shown to predict survival in patients with advanced breast and renal cancer.29-33 Yoga has been shown to lead to less cortisol dysregulation due to radiotherapy and to reductions in mean cortisol levels and early morning cortisol levels in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy.34 This lends support to the hypothesis that yoga helps restore HPA axis balance.

Proinflammatory Cytokines

Cancer patients tend to have increased levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interferon-γ, and C-reactive protein. This increase in inflammation is associated with worse outcomes in cancer.35 This association becomes highly relevant because the effect of inflammation on host cells in the tumor microenvironment is connected to disease progression.26 Inflammatory cytokines are also implicated in cancer-related symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, peripheral neuropathy, and sleep disturbances.36

Yoga is known to reduce stress and may directly or indirectly decrease inflammatory cytokines. A randomized clinical trial of a 12-week hatha yoga intervention among breast cancer survivors demonstrated decreases in IL-6, IL-1β, TNF, corticotropin-releasing factor, and cognitive complaints in the yoga group compared with those in the standard care group after 3 months.37,38 Furthermore, Carlson et al showed that, after mindfulness-based stress reduction involving a combination of gentle yoga, meditation techniques, and relaxation exercises, breast and prostate cancer patients had reduced levels of proinflammatory cytokines and cortisol.39 These reductions translated into patients reporting decreased stress levels and enhanced QOL.

Immune Function

The effects of yoga practice on the immune system have been studied in both healthy individuals and individuals with cancer. The effects on T and B lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, and other immune effector cells demonstrate that meditation and yoga have beneficial effects on immune activity.40 Hormones such as catecholamines and glucocorticoids are thought to influence the availability and function of NK cells, and, as noted above, yoga has been shown to modulate stress hormones and lead to reduced immune suppression in patients with early-stage breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy.41 Additional evidence supports the ability of yoga to reduce immune suppression in the postsurgical setting, with no observed decrease in NK cell percentage after surgery for those in a yoga group compared with a control group.42 This finding is relevant to patients undergoing surgical management of their cancer and highlights the impact of yoga on the immune system.

DNA Damage

Radiation damages DNA in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients undergoing treatment.43,44 This damage is significant in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy.45 Stress additionally causes DNA damage46 and is correlated to impaired DNA repair capacity.47,48 In a study conducted by Banerjee et al, breast cancer patients were randomly assigned to a yoga group or a supportive therapy group for 6 weeks during radiotherapy.49 Prior to the intervention, patients in the study had significant genomic instability. After treatment, patients in the yoga group experienced not only a significant reduction in anxiety and depression levels, but also a reduction in DNA damage due to radiotherapy.

Yoga in Quality of Life and Symptom Management

There is evidence showing that yoga therapy improves multiple aspects of QOL, including physical functioning, emotional health outcomes, and the symptoms cancer patients may experience, such as sleep disturbances, fatigue, and pain. Danhauer et al systematically reviewed both nonrandomized trials and randomized controlled trials involving yoga during cancer treatment.50 They found that yoga improved depression and anxiety as well as sleep and fatigue. Benefits of yoga in cancer based on randomized controlled trials are summarized in the Table. The role of yoga in improving QOL and managing symptoms patients experience during and after treatment is discussed in the following sections.

Quality of Life

Danhauer et al’s systematic review of trials involving yoga during cancer treatment found that yoga improved multiple aspects of QOL.50 For example, yoga has been shown to improve QOL in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. In a study by Chandwani et al, yoga (60-minute sessions twice a week for 6 weeks) was associated with better general health perception and physical functioning scores as well as greater benefit finding, or finding meaning in their experience, after radiotherapy compared with a wait-list group.51 The yoga group had an increase in intrusive thoughts, believed to be due to a more thorough processing of the cancer experience, which helps to improve patients’ outlook on life.52 The benefits of yoga extend beyond psychological measures during radiation treatment. Yoga was found to increase physical functioning compared with stretching in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy.53

Cognitive Function

Cancer-related cognitive impairment commonly occurs during cancer treatments (eg, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, hormone therapy) and persists for months or years in survivors.54 Impairment of memory, executive function, attention, and concentration are commonly reported. In a trial of a combined hatha and restorative yoga program called Yoga for Cancer Survivors (YOCAS), which was designed by researchers at the University of Rochester, patients in the yoga arm had less memory difficulty than did patients in the standard care arm.55 However, the primary aim of the trial was to treat insomnia, so this secondary outcome needs to be interpreted with caution. Deficits in attention, memory, and executive function are often seen in cancer-related cognitive impairment, and the meditative aspect of yoga may have behavioral and neurophysical benefits that could improve cognitive functions.56 More evidence is needed to understand the role of yoga in improving cognitive functioning.

Emotional Health

Psychosocial stress is high among breast cancer patients and survivors.57,58 This causes circadian rhythm and cortisol regulation abnormalities, which are reported in women with breast cancer.59-64 Yoga is known to help stress and psychosocial and physical functioning in patients with cancer.65 Yoga was also shown to be equivalent to cognitive behavioral therapy in stress management in a population of patients without cancer.66 Daily yoga sessions lasting 60 minutes were shown to reduce reactive anxiety and trait anxiety in early-stage breast cancer patients undergoing conventional radiotherapy and chemotherapy compared with patients receiving supportive therapy, highlighting the role of yoga in managing anxiety related to treatment.67 In a study done by Culos-Reed et al, 20 cancer survivors who did 75 minutes of yoga per week for 7 weeks were compared with 18 cancer survivors who served as a control group.68 The intervention group reported significant improvement in emotional well-being, depression, concentration, and mood disturbances. In a longitudinal study by Mackenzie et al, 66 cancer survivors completed a 7-week yoga program and were assessed at baseline, immediately after the final yoga session, and at 3 and 6 months after the final session.69 Participants had significantly improved energy levels and affect. They also had moderate improvement in mindfulness and a moderate decrease in stress. Breast cancer patients who underwent restorative yoga sessions found improvements in mental health, depression, positive affect, and spirituality (peace/meaning).70 This was more pronounced in women with higher negative affect and lower emotional well-being at baseline. In a study of patients with ovarian cancer receiving chemotherapy, patients were instructed to perform up to 15-minute sessions including awareness, body movement, and breathing.71 Even with just 1 session of yoga intervention, patients experienced decreased anxiety.

Fatigue

Studies on yoga show improvement in fatigue both during and after treatment. In breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, yoga was shown to benefit cognitive fatigue.72 Older cancer survivors also seem to benefit from yoga interventions.73 In a trial of a DVD-based yoga program, the benefits of yoga were similar to those of strengthening exercises, and both interventions helped decrease fatigue and improve QOL during the first year after diagnosis in early-stage breast cancer patients with cancer-related fatigue.74 Bower et al also showed that, for breast cancer survivors experiencing persistent chronic fatigue, a targeted yoga intervention led to significant improvements in fatigue and vigor over a 3-month follow-up compared with controls.75 Fatigue is commonly seen in breast cancer patients who are receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. In a study by Taso et al, women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy were assigned to 60-minute yoga sessions incorporating Anusara yoga, gentle stretching, and relaxation twice a week for 8 weeks.76 By week 4, patients with low pretest fatigue in the yoga group experienced a reduction in fatigue. By week 8, all patients in the yoga group experienced a reduction in fatigue. Four weeks after the yoga intervention, patients in the group maintained the reduction in fatigue. This study shows the feasibility of an 8-week yoga program for women undergoing breast cancer therapy by improving fatigue. Yoga recently was added to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for management of cancer-related fatigue (level 1 evidence).77 However, the evidence was based on studies in women with breast cancer and survivors; therefore, more studies are needed in men and women with other cancers.

Surgical Setting/Postoperative Distress

Distress surrounding surgery in patients with breast cancer can impact postoperative outcomes. Yoga interventions, including breathing exercises, regulated breathing, and yogic relaxation techniques, improved several postsurgical measures such as length of hospital stay, drain retention, and suture removal.78 In this study, patients who practiced yoga also experienced a decrease in plasma TNF and better wound healing. Symptoms of anxiety and distress that occur preoperatively can lead to impaired immune function in addition to decreased QOL. In a study of yoga in early-stage breast cancer patients undergoing surgery, the benefit of yoga was seen not only with stress reduction but also with immune enhancement.42

Yoga has been shown to help alleviate acute pain and distress in women undergoing major surgery for gynecological cancer. A regimen of 3 15-minute sessions of yoga, including awareness meditation, coordination of breath with movement, and relaxation breathing, was shown to reduce acute pain and distress in such patients in an inpatient setting.79

Menopausal Symptoms

Breast cancer survivors have more severe menopausal symptoms compared with women without cancer.80,81 Hot flashes cause sleep disturbances and worsen fatigue and QOL.82 Tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors significantly worsen menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes.81 Carson et al conducted a study of yoga that included postures, breathing techniques, didactic presentations, and group discussions.83 The yoga awareness regimen consisted of 8 weekly 120-minute group classes. Patients in the yoga arm had statistically significant improvements in the frequency, severity, and number of hot flashes. There were also improvements in arthralgia (joint pain), fatigue, sleep disturbance, vigor, and acceptance.

Arthralgia

Joint pain can be a major side effect that interferes with daily functions and activities in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors who receive aromatase inhibitor therapy.84 Arthralgia is reported in up to 50% of patients treated with aromatase inhibitors.84,85 It can affect functional status and lead to discontinuation of aromatase inhibitor therapy, jeopardizing clinical outcomes.86 Yoga as a complementary therapy has been shown to improve conditions such as low back pain87 and knee osteoarthritis88 in patients who do not have cancer. In a single-arm pilot trial by Galantino et al, breast cancer patients with aromatase inhibitor–related joint pain were provided with twice-weekly yoga sessions for 8 weeks. There were statistically significant improvements in balance, flexibility, pain severity, and health-related QOL.89 As noted above, improvement in arthralgia was also found in the study conducted by Carson et al.83

Insomnia

Insomnia is common among cancer patients and survivors90,91 and leads to increased fatigue and depression, decreased adherence to cancer treatments, and poor physical function and QOL.90-92 Management of insomnia consists of pharmacologic therapies such as benzodiazepines93,94 and nonpharmacologic options such as cognitive behavioral therapy.95

The first study of yoga found to improve sleep quality was conducted at MD Anderson Cancer Center in lymphoma patients.96 The effects of Tibetan yoga practices incorporating controlled breathing and visualization, mindfulness techniques, and low-impact postures were studied. Patients in the Tibetan yoga group had better subjective sleep quality, faster sleep latency, longer sleep duration, and less use of sleep medications. Mustian et al conducted a large yoga study in cancer survivors in which patients reporting chronic sleep disturbances were randomly assigned to the YOCAS program, which consisted of pranayama (breath control), 16 gentle hatha and restorative yoga postures, and meditation, or to usual care.92 The study reported improvements in global sleep quality, subjective sleep quality, actigraphy measures (wake after sleep onset, sleep efficiency), daytime dysfunction, and use of sleep medication after the yoga intervention compared with participants who received standard care.

Yoga to Address Other Symptoms

There is preliminary evidence supporting yoga as an integrative therapy for other symptoms unique to cancer survivors. For example, in head and neck cancer survivors, soft tissue damage involving the jaw, neck, shoulders, and chest results in swallowing issues, trismus, and aspiration, which are more pronounced in patients treated with conventional radiotherapy than in those treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy.97 Some late effects of radiotherapy for head and neck cancer—such as pain, anxiety, and impaired shoulder function—were shown to be improved through the practice of hatha yoga in 1 study.98 Similarly, in a randomized controlled pilot study of patients with stage I to III breast cancer 6 months after treatment, participants in an 8-week yoga program experienced a reduction in arm induration and improvement in a QOL subscale of lymphedema symptoms. However, more evidence is needed to support the use of yoga as a therapeutic measure for breast cancer lymphedema.99,100

Yoga for Caregivers

Along with cancer patients, caregivers face psychological and physical burdens as well as deterioration in their QOL. Caregivers tend to report clinical levels of anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and fatigue and have similar or in fact higher levels than those of the patients for whom they are caring.101,102 Yoga has been found to help caregivers of patients with cancer. Recently, MD Anderson researchers conducted a trial in patients with high-grade glioma and their caregivers as dyads.103,104 Each dyad attended 2 or 3 60-minute weekly Vivekananda yoga sessions involving breathing exercises, physical exercises, relaxation, and meditation. The researchers found that the yoga program was safe, feasible, acceptable, and subjectively useful for patients with high-grade glioma and their caregivers. Preliminary evidence of QOL improvement for both patients and caregivers was noted. An improvement in QOL was also demonstrated in another preliminary study of yoga in patients undergoing thoracic radiotherapy and their caregivers.105

Another study by the group at MD Anderson evaluated a couple-based Tibetan yoga program that emphasized breathing exercises, gentle movements, guided visualizations, and emotional connectedness during radiotherapy for lung cancer.106 This study included 10 patient‐caregiver dyads and found the program to be feasible, safe, and acceptable. The researchers also found preliminary evidence of improved QOL by the end of radiotherapy relative to baseline—specifically in the areas of spiritual well‐being for patients, fatigue for caregivers, and sleep disturbances and mental health issues such as anxiety and depressive symptoms for both patients and caregivers. This is noteworthy, as QOL typically deteriorates during the course of radiotherapy, and the yoga program was able to buffer these changes.

Conclusion

Yoga therapy has been used successfully as an adjunct modality to improve QOL and cancer-related symptoms. As a part of an integrative medicine approach, yoga is commonly recommended for patients undergoing cancer treatment. Danhauer et al reviewed randomized controlled trials during and after treatment and concluded that the evidence is clearly positive for QOL, fatigue, and perceived stress.107 Results are less consistent but supportive for psychosocial outcomes such as benefit finding and spirituality. Evidence is mixed for sleep, anxiety, and depression. Post-treatment studies demonstrate improvements in fatigue, sleep, and multiple QOL domains. Yoga has been included in NCCN guidelines for fatigue management. Yoga, if approved by a physician, is also included among the behavioral therapies for anticipatory emesis and prevention and treatment of nausea in the recent update of the NCCN guidelines.108 The Society for Integrative Oncology guidelines include yoga for anxiety/stress reduction as a part of integrative treatment in breast cancer patients during and after therapy, which was endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.109

Because of the strong evidence for its benefits and a low side-effect profile, yoga is offered in group-class settings for patients during and after treatment and/or for caregivers in our institution. We often prescribe yoga as a therapeutic modality for selected groups of patients in our clinical practice. However, some patients may have restrictions after surgery that must be considered. In general, yoga has an excellent safety profile, the evidence base is strong, and we recommend that yoga therapy should be part of the standard of care as an integrative approach for patients with cancer undergoing active treatment as well as for cancer survivors and caregivers.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank Bryan Tutt for providing editorial assistance.

Corresponding author: Santhosshi Narayanan, MD, Department of Palliative, Rehabilitation, and Integrative Medicine, Unit 1414, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1400 Pressler St., Houston, TX 77030; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX (Drs. Narayanan, Lopez, Chaoul, Liu, Milbury, and Cohen, and Ms. Mallaiah); the University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler (Dr. Meegada); and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, TX (Ms. Francisco).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the effects of yoga as an adjunct supportive care modality alongside conventional cancer treatment on quality of life (QOL), physical and mental health outcomes, and physiological and biological measures of cancer survivors.

- Methods: Nonsystematic review of the literature.

- Results: Yoga therapy, one of the most frequently used mind-body modalities, has been studied extensively in cancer survivors (from the time of diagnosis through long-term recovery). Yoga affects human physiology on multiple levels, including psychological outcomes, immune and endocrine function, and cardiovascular parameters, as well as multiple areas of QOL. It has been found to reduce psychological stress and fatigue and improve QOL in cancer patients and survivors. Yoga has also been used to manage symptoms such as arthralgia, fatigue, and insomnia. In addition, yoga offers benefits not only for cancer survivors but also for their caregivers.

- Conclusion: As part of an integrative, evidence-informed approach to cancer care, yoga may provide benefits that support the health of cancer survivors and caregivers.

Keywords: fatigue; cancer; proinflammatory cytokines; integrative; mind-body practices; meditation; DNA damage; stress; psychoneuro-immunoendocrine axis; lymphedema; insomnia.

A diagnosis of cancer and adverse effects related to its treatment may have negative effects on quality of life (QOL), contributing to emotional and physical distress in patients and caregivers. Many patients express an interest in pursuing nonpharmacological options, alone or as an adjunct to conventional therapy, to help manage symptoms. The use of complementary medicine approaches to health, including nonpharmacological approaches to symptom management, is highest among individuals with cancer.1 According to a published expert consensus, integrative oncology is defined as a “patient-centered, evidence-informed field of cancer care that utilizes mind and body practices, natural products, and/or lifestyle modifications from different traditions alongside conventional cancer treatments. Integrative oncology aims to optimize health, QOL, and clinical outcomes across the cancer care continuum and to empower people to prevent cancer and become active participants before, during, and beyond cancer treatment.”2 A key component of this definition, often misunderstood in the field of oncology, is that these modalities and treatments are used alongside conventional cancer treatments and not as an alternative. In an attempt to meet patients’ needs and appropriately use these approaches, integrative oncology programs are now part of most cancer centers in the United States.3-6

Because of their overall safety, mind-body therapies are commonly used by patients and recommended by clinicians. Mind-body therapies include yoga, tai chi, qigong, meditation, and relaxation. Expressive arts such as journaling and music, art, and dance therapies also fall in the mind-body category.7 Yoga is a movement-based mind-body practice that focuses on synchronizing body, breath, and mind. Yoga has been increasingly used by patients for health benefits,8 and numerous studies have evaluated yoga as a complementary intervention for individuals with cancer.9-14 Here, we review the physiological basis of yoga in oncology and the effects of yoga on biological processes, QOL, and symptoms during and after cancer treatment.

Physiological Basis

Many patients may use mind-body programs such as yoga to help manage the psychological and physiological consequences of unmanaged chronic stress and improve their overall QOL. The central nervous system, endocrine system, and immune system influence and interact with each other in a complex manner in response to chronic stress.15,16 In a stressful situation, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) are activated. HPA axis stimulation leads to adrenocorticotrophic hormone production by the pituitary gland, which releases glucocorticoid hormones. SNS axis stimulation leads to epinephrine and norepinephrine production by the adrenal gland.17,18 Recently, studies have explored modulation of signal transduction between the nervous and immune systems and how that may impact tumor growth and metastasis.19 Multiple studies, controlled for prognosis, disease stage, and other factors, have shown that patients experiencing more distress or higher levels of depressive symptoms do not live as long as their counterparts with low distress or depression levels.20 Both the meditative and physical components of yoga can lead to enhanced relaxation, reduced SNS activation, and greater parasympathetic tone, countering the negative physiological effects of chronic stress. The effects of yoga on the HPA axis and SNS, proinflammatory cytokines, immune function, and DNA damage are discussed below.

Biological Processes

Nervous System

The effects of yoga and other forms of meditation on brain functions have been established through several studies. Yoga seems to influence basal ganglia function by improving circuits that are involved in complex cognitive functions, motor coordination, and somatosensory and emotional processes.21,22 Additionally, changes in neurotransmitter levels have been observed after yoga practice. For instance, in a 12-week yoga intervention in healthy subjects, increased levels of thalamic gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the yoga group were reported to have a positive correlation with improved mood and decreased anxiety compared with a group who did metabolically matched walking exercise.23 Levels of GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, are decreased in conditions such as anxiety, depression, and epilepsy.24 Yoga therapy has been shown to improve symptoms of mood disorders and epilepsy, which leads to the hypothesis that the mechanism driving the benefits of yoga may work through stimulation of vagal efferents and an increase in GABA-mediated cortical-inhibitory tone.24,25

HPA Axis