User login

M. Alexander Otto began his reporting career early in 1999 covering the pharmaceutical industry for a national pharmacists' magazine and freelancing for the Washington Post and other newspapers. He then joined BNA, now part of Bloomberg News, covering health law and the protection of people and animals in medical research. Alex next worked for the McClatchy Company. Based on his work, Alex won a year-long Knight Science Journalism Fellowship to MIT in 2008-2009. He joined the company shortly thereafter. Alex has a newspaper journalism degree from Syracuse (N.Y.) University and a master's degree in medical science -- a physician assistant degree -- from George Washington University. Alex is based in Seattle.

ACS: Hopkins risk score predicts need for early nutrition after cardiac surgery

CHICAGO – A few simple baseline variables predict if heart surgery patients will need early nutritional support after their operations, based on a review of more than 1,000 cardiac surgery patients from Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

Nonelective surgery and a cardiopulmonary bypass time of 100 minutes or more, plus five preop variables – previous cardiac interventions; total albumin below 4 g/dL; total bilirubin at or above 1.2 mg/dL; white blood cell counts at or above 11,000/mcL; and hematocrit below 27% – predict the need for nutrition in the first few days after cardiac surgery, they found (J Am Coll Surg. 2015 Oct: 221[4];e70).

The Hopkins team has combined those factors into a risk score, with 4 points assigned for low albumin, 6 points for nonelective surgery, 6 points for low hematocrit, and 5 points for the other four variables, yielding a maximum score of 36 points.

The researchers developed the system after discovering that it sometimes took more than a week for cardiac patients who needed postop nutrition to get it. About 40% of patients with scores of 20 or higher will need early nutritional support, and those heart patients are now the ones at Hopkins who get a nutrition consult as soon as they return from the operating room, said Dr. Rika Ohkuma, a general surgery research fellow at Johns Hopkins. “The score can be used for risk stratification and has potential quality improvement implications related to early initiation of nutritional support in high-risk patients.”

Just 2% of patients who score 10 points or below need early nutrition, so consults are less pressing. About 9% of patients who score from 10-20 points will require nutrition, so consults are at the discretion of the physician, the investigators concluded.

Those insights came from a review of 1,056 adult heart cases in 2012. Just 87 patients (8%) had a postop consult for nutritional support. Most wound up with enteral feedings, but they started an average of 5 days after surgery. The handful that needed both parenteral and enteric feedings started them an average of 7 days after surgery.

Meanwhile, those 87 patients had significantly higher hospital mortality (29% vs. 3%), ventilator time (278 vs. 20 hours), and gastrointestinal complications (32% vs. 5%), and fewer discharges to home (49% vs. 84%) than did other patients.

The team thought that the delay in feeding might have had something to do with the poor outcomes, so “we tried to improve our behavior. We know that nutrition is beneficial for critically ill patients and that we need to start early, but there was no gold standard for when to start,” Dr. Ohkuma said.

The investigators came up with the risk score after figuring out how patients who needed nutrition differed from those who did not. They found, for example, that patients who have emergent surgery were more than three times as likely to have a nutrition consult than were those who had elective procedures.

Now when patients are admitted to the ICU after cardiac surgery, “we all know their [nutrition] score; if they are likely to need support, we immediately call the nutritional support service for a consult.” Patients no longer have to wait, Dr. Ohkuma said.

The researchers launched a prospective study in January 2015. Nutritional needs were addressed sooner, at about postop day 4, for the 70 patients who have needed, and mortality seems to be dropping.

The investigators have no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – A few simple baseline variables predict if heart surgery patients will need early nutritional support after their operations, based on a review of more than 1,000 cardiac surgery patients from Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

Nonelective surgery and a cardiopulmonary bypass time of 100 minutes or more, plus five preop variables – previous cardiac interventions; total albumin below 4 g/dL; total bilirubin at or above 1.2 mg/dL; white blood cell counts at or above 11,000/mcL; and hematocrit below 27% – predict the need for nutrition in the first few days after cardiac surgery, they found (J Am Coll Surg. 2015 Oct: 221[4];e70).

The Hopkins team has combined those factors into a risk score, with 4 points assigned for low albumin, 6 points for nonelective surgery, 6 points for low hematocrit, and 5 points for the other four variables, yielding a maximum score of 36 points.

The researchers developed the system after discovering that it sometimes took more than a week for cardiac patients who needed postop nutrition to get it. About 40% of patients with scores of 20 or higher will need early nutritional support, and those heart patients are now the ones at Hopkins who get a nutrition consult as soon as they return from the operating room, said Dr. Rika Ohkuma, a general surgery research fellow at Johns Hopkins. “The score can be used for risk stratification and has potential quality improvement implications related to early initiation of nutritional support in high-risk patients.”

Just 2% of patients who score 10 points or below need early nutrition, so consults are less pressing. About 9% of patients who score from 10-20 points will require nutrition, so consults are at the discretion of the physician, the investigators concluded.

Those insights came from a review of 1,056 adult heart cases in 2012. Just 87 patients (8%) had a postop consult for nutritional support. Most wound up with enteral feedings, but they started an average of 5 days after surgery. The handful that needed both parenteral and enteric feedings started them an average of 7 days after surgery.

Meanwhile, those 87 patients had significantly higher hospital mortality (29% vs. 3%), ventilator time (278 vs. 20 hours), and gastrointestinal complications (32% vs. 5%), and fewer discharges to home (49% vs. 84%) than did other patients.

The team thought that the delay in feeding might have had something to do with the poor outcomes, so “we tried to improve our behavior. We know that nutrition is beneficial for critically ill patients and that we need to start early, but there was no gold standard for when to start,” Dr. Ohkuma said.

The investigators came up with the risk score after figuring out how patients who needed nutrition differed from those who did not. They found, for example, that patients who have emergent surgery were more than three times as likely to have a nutrition consult than were those who had elective procedures.

Now when patients are admitted to the ICU after cardiac surgery, “we all know their [nutrition] score; if they are likely to need support, we immediately call the nutritional support service for a consult.” Patients no longer have to wait, Dr. Ohkuma said.

The researchers launched a prospective study in January 2015. Nutritional needs were addressed sooner, at about postop day 4, for the 70 patients who have needed, and mortality seems to be dropping.

The investigators have no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – A few simple baseline variables predict if heart surgery patients will need early nutritional support after their operations, based on a review of more than 1,000 cardiac surgery patients from Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

Nonelective surgery and a cardiopulmonary bypass time of 100 minutes or more, plus five preop variables – previous cardiac interventions; total albumin below 4 g/dL; total bilirubin at or above 1.2 mg/dL; white blood cell counts at or above 11,000/mcL; and hematocrit below 27% – predict the need for nutrition in the first few days after cardiac surgery, they found (J Am Coll Surg. 2015 Oct: 221[4];e70).

The Hopkins team has combined those factors into a risk score, with 4 points assigned for low albumin, 6 points for nonelective surgery, 6 points for low hematocrit, and 5 points for the other four variables, yielding a maximum score of 36 points.

The researchers developed the system after discovering that it sometimes took more than a week for cardiac patients who needed postop nutrition to get it. About 40% of patients with scores of 20 or higher will need early nutritional support, and those heart patients are now the ones at Hopkins who get a nutrition consult as soon as they return from the operating room, said Dr. Rika Ohkuma, a general surgery research fellow at Johns Hopkins. “The score can be used for risk stratification and has potential quality improvement implications related to early initiation of nutritional support in high-risk patients.”

Just 2% of patients who score 10 points or below need early nutrition, so consults are less pressing. About 9% of patients who score from 10-20 points will require nutrition, so consults are at the discretion of the physician, the investigators concluded.

Those insights came from a review of 1,056 adult heart cases in 2012. Just 87 patients (8%) had a postop consult for nutritional support. Most wound up with enteral feedings, but they started an average of 5 days after surgery. The handful that needed both parenteral and enteric feedings started them an average of 7 days after surgery.

Meanwhile, those 87 patients had significantly higher hospital mortality (29% vs. 3%), ventilator time (278 vs. 20 hours), and gastrointestinal complications (32% vs. 5%), and fewer discharges to home (49% vs. 84%) than did other patients.

The team thought that the delay in feeding might have had something to do with the poor outcomes, so “we tried to improve our behavior. We know that nutrition is beneficial for critically ill patients and that we need to start early, but there was no gold standard for when to start,” Dr. Ohkuma said.

The investigators came up with the risk score after figuring out how patients who needed nutrition differed from those who did not. They found, for example, that patients who have emergent surgery were more than three times as likely to have a nutrition consult than were those who had elective procedures.

Now when patients are admitted to the ICU after cardiac surgery, “we all know their [nutrition] score; if they are likely to need support, we immediately call the nutritional support service for a consult.” Patients no longer have to wait, Dr. Ohkuma said.

The researchers launched a prospective study in January 2015. Nutritional needs were addressed sooner, at about postop day 4, for the 70 patients who have needed, and mortality seems to be dropping.

The investigators have no relevant disclosures.

AT THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Early evaluation for nutritional needs following heart surgery might prove to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Major finding: In a retrospective study, the 87 patients who received nutritional support an average of 5 or more days after surgery had significantly higher hospital mortality (29% vs. 3%), ventilator time (278 vs. 20 hours), and gastrointestinal complications (32% vs. 5%) than did other post-op patients.

Data source: Review of 1,056 heart surgery patients

Disclosures: The investigators have no relevant disclosures.

ACS: Loop ileostomy may give IBD colitis patients an alternative to urgent colectomy

CHICAGO – Diverting loop ileostomy may be a better option than urgent colectomy as the first surgical step for medically refractory severe ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Investigators from the University of California, Los Angeles, have found that ileostomy gives patients a chance to recover from their acute illness – and their colons a chance to heal – so they’re in better shape for definitive surgery further down the road, if it’s even needed (J Am Coll Surg. 2015 Oct;221[4]:S37-S38).

“Urgent colectomy is standard practice for medically refractory severe ulcerative and Crohn’s colitis. However, immunosuppression and malnutrition can result in significant morbidity. This change in management strategy does not eliminate the potential need for definitive surgery, but it does allow for the more extensive procedure to be performed in an elective setting under optimized conditions, thereby improving clinical outcomes,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Amy Lightner, formerly of UCLA but now a colorectal surgery fellow at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

There were just eight patients in the series, so the results are tentative. Six had ulcerative colitis (UC) and two had Crohn’s disease (CD). On presentation, the patients were tachycardic, febrile, malnourished, and anemic, with severe mucosal disease confirmed by endoscopy. Steroids, immunomodulators, and biologics no longer helped. Overall, the patients were too sick to go home, but not quite sick enough for the ICU. Their average age was 29 years.

They underwent a single-incision, laparoscopic diverting loop ileostomy, which took about 45 minutes. The technique, and perhaps the thinking behind it, are similar to one gaining popularity for Clostridium difficile colitis, but without the colonic lavage.

Within 24-48 hours postop, tachycardia and fevers resolved, and patients tolerated oral intake. Narcotic use dropped, and bloody stools became less frequent, and then ceased in all but one patient. Within a month, the average hemoglobin level had climbed from a baseline of 9 g/dL to 11.5 g/dL, and average albumin from 2.5 g/dL to 4 g/dL. Within 2 months, patients’ bowels looked pink and healthy on repeat endoscopy.

“It was a remarkable turnaround. Within 48 hours, they looked markedly different. We are having very good results with this, and it’s much better for patients” than is colectomy during acute illness. “It’s a good change in management,” Dr. Lightner said.

After months of follow-up, two patients, one with UC and one with CD, haven’t needed a colectomy and are maintained on biologics. The other UC patients have had ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. The other CD patient had a subsequent ileorectal anastomosis. Patients were able to undergo those procedures laparoscopically and “have done really well,” Dr. Lightner said.

It’s unclear why loop ileostomy seems so helpful. Perhaps it has something to do with shifts in bacterial populations or decompression of the colon. Maybe it’s just about giving the colon a rest, she said.

The investigators will continue to study the approach. Since the initial report, 8 more patients have joined the series, for a current total of 16. “We are still seeing good results,” Dr. Lightner said.

Dr. Lightner has no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the work.

These patients are challenging. Often, they are on multiple immunomodulators and are malnourished and anemic, with systemic manifestations of inflammatory disease. The abdomen may be hostile. None of these are favorable factors for doing a total abdominal colectomy, but that remains the standard even today.

This is truly a feasibility or pilot study, and as such, it’s difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Cost-effectiveness is unclear, and some patients are maintained on biologics when, in fact, they may have had a curative procedure with surgery. The follow-up isn’t long enough to look at recurrence of colitis. Nevertheless, it certainly is an intriguing and perhaps revolutionary approach to treating these patients.

Dr. Sean C. Glasgow is a colorectal surgeon and assistant professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis. He was not involved with the study.

These patients are challenging. Often, they are on multiple immunomodulators and are malnourished and anemic, with systemic manifestations of inflammatory disease. The abdomen may be hostile. None of these are favorable factors for doing a total abdominal colectomy, but that remains the standard even today.

This is truly a feasibility or pilot study, and as such, it’s difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Cost-effectiveness is unclear, and some patients are maintained on biologics when, in fact, they may have had a curative procedure with surgery. The follow-up isn’t long enough to look at recurrence of colitis. Nevertheless, it certainly is an intriguing and perhaps revolutionary approach to treating these patients.

Dr. Sean C. Glasgow is a colorectal surgeon and assistant professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis. He was not involved with the study.

These patients are challenging. Often, they are on multiple immunomodulators and are malnourished and anemic, with systemic manifestations of inflammatory disease. The abdomen may be hostile. None of these are favorable factors for doing a total abdominal colectomy, but that remains the standard even today.

This is truly a feasibility or pilot study, and as such, it’s difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Cost-effectiveness is unclear, and some patients are maintained on biologics when, in fact, they may have had a curative procedure with surgery. The follow-up isn’t long enough to look at recurrence of colitis. Nevertheless, it certainly is an intriguing and perhaps revolutionary approach to treating these patients.

Dr. Sean C. Glasgow is a colorectal surgeon and assistant professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis. He was not involved with the study.

CHICAGO – Diverting loop ileostomy may be a better option than urgent colectomy as the first surgical step for medically refractory severe ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Investigators from the University of California, Los Angeles, have found that ileostomy gives patients a chance to recover from their acute illness – and their colons a chance to heal – so they’re in better shape for definitive surgery further down the road, if it’s even needed (J Am Coll Surg. 2015 Oct;221[4]:S37-S38).

“Urgent colectomy is standard practice for medically refractory severe ulcerative and Crohn’s colitis. However, immunosuppression and malnutrition can result in significant morbidity. This change in management strategy does not eliminate the potential need for definitive surgery, but it does allow for the more extensive procedure to be performed in an elective setting under optimized conditions, thereby improving clinical outcomes,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Amy Lightner, formerly of UCLA but now a colorectal surgery fellow at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

There were just eight patients in the series, so the results are tentative. Six had ulcerative colitis (UC) and two had Crohn’s disease (CD). On presentation, the patients were tachycardic, febrile, malnourished, and anemic, with severe mucosal disease confirmed by endoscopy. Steroids, immunomodulators, and biologics no longer helped. Overall, the patients were too sick to go home, but not quite sick enough for the ICU. Their average age was 29 years.

They underwent a single-incision, laparoscopic diverting loop ileostomy, which took about 45 minutes. The technique, and perhaps the thinking behind it, are similar to one gaining popularity for Clostridium difficile colitis, but without the colonic lavage.

Within 24-48 hours postop, tachycardia and fevers resolved, and patients tolerated oral intake. Narcotic use dropped, and bloody stools became less frequent, and then ceased in all but one patient. Within a month, the average hemoglobin level had climbed from a baseline of 9 g/dL to 11.5 g/dL, and average albumin from 2.5 g/dL to 4 g/dL. Within 2 months, patients’ bowels looked pink and healthy on repeat endoscopy.

“It was a remarkable turnaround. Within 48 hours, they looked markedly different. We are having very good results with this, and it’s much better for patients” than is colectomy during acute illness. “It’s a good change in management,” Dr. Lightner said.

After months of follow-up, two patients, one with UC and one with CD, haven’t needed a colectomy and are maintained on biologics. The other UC patients have had ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. The other CD patient had a subsequent ileorectal anastomosis. Patients were able to undergo those procedures laparoscopically and “have done really well,” Dr. Lightner said.

It’s unclear why loop ileostomy seems so helpful. Perhaps it has something to do with shifts in bacterial populations or decompression of the colon. Maybe it’s just about giving the colon a rest, she said.

The investigators will continue to study the approach. Since the initial report, 8 more patients have joined the series, for a current total of 16. “We are still seeing good results,” Dr. Lightner said.

Dr. Lightner has no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the work.

CHICAGO – Diverting loop ileostomy may be a better option than urgent colectomy as the first surgical step for medically refractory severe ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Investigators from the University of California, Los Angeles, have found that ileostomy gives patients a chance to recover from their acute illness – and their colons a chance to heal – so they’re in better shape for definitive surgery further down the road, if it’s even needed (J Am Coll Surg. 2015 Oct;221[4]:S37-S38).

“Urgent colectomy is standard practice for medically refractory severe ulcerative and Crohn’s colitis. However, immunosuppression and malnutrition can result in significant morbidity. This change in management strategy does not eliminate the potential need for definitive surgery, but it does allow for the more extensive procedure to be performed in an elective setting under optimized conditions, thereby improving clinical outcomes,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Amy Lightner, formerly of UCLA but now a colorectal surgery fellow at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

There were just eight patients in the series, so the results are tentative. Six had ulcerative colitis (UC) and two had Crohn’s disease (CD). On presentation, the patients were tachycardic, febrile, malnourished, and anemic, with severe mucosal disease confirmed by endoscopy. Steroids, immunomodulators, and biologics no longer helped. Overall, the patients were too sick to go home, but not quite sick enough for the ICU. Their average age was 29 years.

They underwent a single-incision, laparoscopic diverting loop ileostomy, which took about 45 minutes. The technique, and perhaps the thinking behind it, are similar to one gaining popularity for Clostridium difficile colitis, but without the colonic lavage.

Within 24-48 hours postop, tachycardia and fevers resolved, and patients tolerated oral intake. Narcotic use dropped, and bloody stools became less frequent, and then ceased in all but one patient. Within a month, the average hemoglobin level had climbed from a baseline of 9 g/dL to 11.5 g/dL, and average albumin from 2.5 g/dL to 4 g/dL. Within 2 months, patients’ bowels looked pink and healthy on repeat endoscopy.

“It was a remarkable turnaround. Within 48 hours, they looked markedly different. We are having very good results with this, and it’s much better for patients” than is colectomy during acute illness. “It’s a good change in management,” Dr. Lightner said.

After months of follow-up, two patients, one with UC and one with CD, haven’t needed a colectomy and are maintained on biologics. The other UC patients have had ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. The other CD patient had a subsequent ileorectal anastomosis. Patients were able to undergo those procedures laparoscopically and “have done really well,” Dr. Lightner said.

It’s unclear why loop ileostomy seems so helpful. Perhaps it has something to do with shifts in bacterial populations or decompression of the colon. Maybe it’s just about giving the colon a rest, she said.

The investigators will continue to study the approach. Since the initial report, 8 more patients have joined the series, for a current total of 16. “We are still seeing good results,” Dr. Lightner said.

Dr. Lightner has no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the work.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Patients with refractory inflammatory bowel disease may benefit from loop ileostomy in lieu of urgent colectomy as a first surgical step.

Major finding: Within 24-48 hours after diverting loop ileostomy, tachycardia and fevers resolved, and patients tolerated oral intake. Narcotic use dropped, and bloody stools became less frequent, then ceased.

Data source: Pilot study in eight patients with refractory inflammatory bowel disease

Disclosures: The lead investigator has no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the work.

ACS: Don’t shy away from venovenous ECMO for trauma lung failure

CHICAGO – Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation will save perhaps a third of patients who – despite maximum ventilator support – go into end-stage respiratory failure after trauma, according to investigators from the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

“Institutions without the available expertise and ICU capabilities should promptly refer patients with end-stage respiratory failure secondary to trauma to a tertiary care center. Venovenous ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] life support may be their only chance for survival and should not be overlooked due to fear of complications,” they concluded.

ECMO usually requires heparin anticoagulation to prevent clots; the fear of subsequent bleeding is one of the things that prevents ECMO’s widespread use in trauma. As a result, “a lot of patients who need ECMO lung support don’t get it,” said Dr. Sarwat Ahmad, of the university.

Dr. Ahmad and her colleagues, however, found that ECMO did not lead to worse outcomes in their lung failure patients.

Their conclusions come from a review of 39 adult blunt and penetrating trauma patients who received ECMO at the university’s Level I trauma center over the past 9 years.

Thirty-two patients had venovenous ECMO mostly for acute respiratory distress; maximal ventilator support, adjunctive medications, and chest therapy did not help. ECMO outflow was from the femoral vein, and blood was returned to the internal jugular vein. Twelve patients (38%) survived, which “is good in this scenario because they otherwise would have died,” Dr. Ahmad said.

The mean pre-ECMO P/F ratio – arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen – among the survivors was 98 mm Hg. Values below 100 mm Hg indicate severe lung injury, but some patients had values approaching 200 mm Hg, meaning that ECMO was a good idea even in patients with less severe lung injury.

Seven patients received venoarterial ECMO mostly for cardiac arrest, with outflow from the femoral vein and blood returned via the femoral artery. The patients were pulseless on arrival, so bypassing the heart seemed the only option, but none of them survived. Because of that, the investigators concluded that venoarterial ECMO is “not going to help” in trauma patients, Dr. Ahmad said.

One of the 12 survivors and over half of those who died had injury severity scores above 40 points. Also, Glasgow coma scores below 8 points were far more common among patients who died.

All 12 of the survivors and 14 of the 27 who died were anticoagulated with heparin. “We didn’t see an increased incidence of complications between those who got heparin and those who did not” and, overall, there wasn’t a higher incidence of complications in ECMO patients, compared with other trauma patients. “Even traumatic brain injury patients didn’t do any worse on ECMO. We don’t think that the fear of complications should turn you away from using ECMO,” Dr. Ahmad said.

Dr. Ahmad has no disclosures; there was no external funding for the work.

CHICAGO – Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation will save perhaps a third of patients who – despite maximum ventilator support – go into end-stage respiratory failure after trauma, according to investigators from the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

“Institutions without the available expertise and ICU capabilities should promptly refer patients with end-stage respiratory failure secondary to trauma to a tertiary care center. Venovenous ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] life support may be their only chance for survival and should not be overlooked due to fear of complications,” they concluded.

ECMO usually requires heparin anticoagulation to prevent clots; the fear of subsequent bleeding is one of the things that prevents ECMO’s widespread use in trauma. As a result, “a lot of patients who need ECMO lung support don’t get it,” said Dr. Sarwat Ahmad, of the university.

Dr. Ahmad and her colleagues, however, found that ECMO did not lead to worse outcomes in their lung failure patients.

Their conclusions come from a review of 39 adult blunt and penetrating trauma patients who received ECMO at the university’s Level I trauma center over the past 9 years.

Thirty-two patients had venovenous ECMO mostly for acute respiratory distress; maximal ventilator support, adjunctive medications, and chest therapy did not help. ECMO outflow was from the femoral vein, and blood was returned to the internal jugular vein. Twelve patients (38%) survived, which “is good in this scenario because they otherwise would have died,” Dr. Ahmad said.

The mean pre-ECMO P/F ratio – arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen – among the survivors was 98 mm Hg. Values below 100 mm Hg indicate severe lung injury, but some patients had values approaching 200 mm Hg, meaning that ECMO was a good idea even in patients with less severe lung injury.

Seven patients received venoarterial ECMO mostly for cardiac arrest, with outflow from the femoral vein and blood returned via the femoral artery. The patients were pulseless on arrival, so bypassing the heart seemed the only option, but none of them survived. Because of that, the investigators concluded that venoarterial ECMO is “not going to help” in trauma patients, Dr. Ahmad said.

One of the 12 survivors and over half of those who died had injury severity scores above 40 points. Also, Glasgow coma scores below 8 points were far more common among patients who died.

All 12 of the survivors and 14 of the 27 who died were anticoagulated with heparin. “We didn’t see an increased incidence of complications between those who got heparin and those who did not” and, overall, there wasn’t a higher incidence of complications in ECMO patients, compared with other trauma patients. “Even traumatic brain injury patients didn’t do any worse on ECMO. We don’t think that the fear of complications should turn you away from using ECMO,” Dr. Ahmad said.

Dr. Ahmad has no disclosures; there was no external funding for the work.

CHICAGO – Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation will save perhaps a third of patients who – despite maximum ventilator support – go into end-stage respiratory failure after trauma, according to investigators from the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

“Institutions without the available expertise and ICU capabilities should promptly refer patients with end-stage respiratory failure secondary to trauma to a tertiary care center. Venovenous ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] life support may be their only chance for survival and should not be overlooked due to fear of complications,” they concluded.

ECMO usually requires heparin anticoagulation to prevent clots; the fear of subsequent bleeding is one of the things that prevents ECMO’s widespread use in trauma. As a result, “a lot of patients who need ECMO lung support don’t get it,” said Dr. Sarwat Ahmad, of the university.

Dr. Ahmad and her colleagues, however, found that ECMO did not lead to worse outcomes in their lung failure patients.

Their conclusions come from a review of 39 adult blunt and penetrating trauma patients who received ECMO at the university’s Level I trauma center over the past 9 years.

Thirty-two patients had venovenous ECMO mostly for acute respiratory distress; maximal ventilator support, adjunctive medications, and chest therapy did not help. ECMO outflow was from the femoral vein, and blood was returned to the internal jugular vein. Twelve patients (38%) survived, which “is good in this scenario because they otherwise would have died,” Dr. Ahmad said.

The mean pre-ECMO P/F ratio – arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen – among the survivors was 98 mm Hg. Values below 100 mm Hg indicate severe lung injury, but some patients had values approaching 200 mm Hg, meaning that ECMO was a good idea even in patients with less severe lung injury.

Seven patients received venoarterial ECMO mostly for cardiac arrest, with outflow from the femoral vein and blood returned via the femoral artery. The patients were pulseless on arrival, so bypassing the heart seemed the only option, but none of them survived. Because of that, the investigators concluded that venoarterial ECMO is “not going to help” in trauma patients, Dr. Ahmad said.

One of the 12 survivors and over half of those who died had injury severity scores above 40 points. Also, Glasgow coma scores below 8 points were far more common among patients who died.

All 12 of the survivors and 14 of the 27 who died were anticoagulated with heparin. “We didn’t see an increased incidence of complications between those who got heparin and those who did not” and, overall, there wasn’t a higher incidence of complications in ECMO patients, compared with other trauma patients. “Even traumatic brain injury patients didn’t do any worse on ECMO. We don’t think that the fear of complications should turn you away from using ECMO,” Dr. Ahmad said.

Dr. Ahmad has no disclosures; there was no external funding for the work.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Venovenous ECMO can be life saving when trauma patients go into respiratory failure.

Major finding: Thirty-two patients had venovenous ECMO, mostly for acute respiratory distress; twelve (38%) survived.

Data source: Review of ECMO in 39 trauma patients

Disclosures: The lead investigator has no disclosures, and there was no external funding for the work.

VIDEO: A better option for C. difficile toxic megacolon

CHICAGO – Last-minute colectomy isn’t the way to go for Clostridium difficile–induced toxic megacolon; outcomes are better with a timely loop ileostomy and colonic lavage.

University of Pittsburgh surgery professor Dr. Brian Zuckerbraun, a pioneer of the technique, explained the procedure and its benefits in an interview at the annual Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Last-minute colectomy isn’t the way to go for Clostridium difficile–induced toxic megacolon; outcomes are better with a timely loop ileostomy and colonic lavage.

University of Pittsburgh surgery professor Dr. Brian Zuckerbraun, a pioneer of the technique, explained the procedure and its benefits in an interview at the annual Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Last-minute colectomy isn’t the way to go for Clostridium difficile–induced toxic megacolon; outcomes are better with a timely loop ileostomy and colonic lavage.

University of Pittsburgh surgery professor Dr. Brian Zuckerbraun, a pioneer of the technique, explained the procedure and its benefits in an interview at the annual Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

ACS: Less pneumonia, fewer deaths with ketamine for rib fracture pain

CHICAGO – Ketamine is a safe and simple alternative to epidural anesthesia for pain control in the setting of multiple rib fractures, investigators from the Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx (N.Y.) concluded after reviewing their experience with the drug.

Epidural analgesia has been the standard for controlling pain after multiple rib fractures, but epidurals are sometimes contraindicated in trauma, especially with back and neck injuries. There’s also a bleeding risk, and the need for an on-call anesthesia team to place them, something not all hospitals have.

Those problems – and the success Jacobi surgeons reported with ketamine pain control after thoracotomy – led the hospital to switch to a ketamine-based rib fracture protocol in 2007.

“As far as we know, we are the only people doing this routinely for multiple rib fractures,” Dr. Joelle Getrajdman, a second-year surgery resident at the medical center, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Patients there with two or more rib fractures get a low-dose peripheral intravenous infusion of ketamine 0.05 mg/kg per hour while in the ICU and step-down unit, along with other pain medications as indicated. The hospital discontinues ketamine once patients leave the step-down unit to prevent diversion for illicit use.

To see how well the protocol has worked, the investigators reviewed all 128 adult trauma patients who received ketamine for multiple rib fractures from 2007 to 2014.

These patients were 60 years old on average, with a median of six rib fractures, many of them bilateral. Almost half had injury severity scores above 15, and most had chest Abbreviated Injury Scores of at least 3. Pneumo- and hemothoraces were common. Patients spent a mean of 6 days in the surgical ICU and 13 days in the hospital.

Along with ketamine, almost all had a morphine or hydromorphone (Dilaudid) patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps, more than half received IV ketorolac (Toradol), and about 40% IV Tylenol. Only 14% had paravertebral or intercostal blocks.

Fourteen patients (10.9%) developed pneumonia, and four (3.1%) died, which compares favorably with outcomes in patients receiving epidurals. Historically, epidural analgesia for multiple traumatic rib fractures has been associated with about an 18% pneumonia rate, and about 9% mortality.

Ketamine side effects were minimal; none of the patients had hallucinations or tachycardia, and three (2.3%) were hypotensive on the drug.

Jacobi’s database did not record how many times patients used their PCA pumps, so the study did not have a direct measure of pain control. The investigators plan to look into this question prospectively.

Even so, when patients hurt from rib fractures, they breathe shallowly, which puts them at risk for pneumonia and death. “We have lower rates” of both than with epidurals, “so you could extrapolate that we must be controlling pain better,” Dr. Getrajdman said.

Ketamine at high doses is an anesthetic, but at lower doses it’s an antagonist of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), and a mild opioid receptor agonist, “so we can give patients the same amount of morphine but achieve a higher analgesic effect,” she said.

Ketamine had been the subject of intense interest in recent years for pain control in a wide variety of settings, as well as for psychiatric and other problems. Clinicaltrials.gov currently lists 138 open investigations of the drug.

Among them is a randomized trial from the Medical College of Wisconsin pitting ketamine against placebo for rib fracture pain following blunt trauma.

Dr. Getrajdman has no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the work.

CHICAGO – Ketamine is a safe and simple alternative to epidural anesthesia for pain control in the setting of multiple rib fractures, investigators from the Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx (N.Y.) concluded after reviewing their experience with the drug.

Epidural analgesia has been the standard for controlling pain after multiple rib fractures, but epidurals are sometimes contraindicated in trauma, especially with back and neck injuries. There’s also a bleeding risk, and the need for an on-call anesthesia team to place them, something not all hospitals have.

Those problems – and the success Jacobi surgeons reported with ketamine pain control after thoracotomy – led the hospital to switch to a ketamine-based rib fracture protocol in 2007.

“As far as we know, we are the only people doing this routinely for multiple rib fractures,” Dr. Joelle Getrajdman, a second-year surgery resident at the medical center, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Patients there with two or more rib fractures get a low-dose peripheral intravenous infusion of ketamine 0.05 mg/kg per hour while in the ICU and step-down unit, along with other pain medications as indicated. The hospital discontinues ketamine once patients leave the step-down unit to prevent diversion for illicit use.

To see how well the protocol has worked, the investigators reviewed all 128 adult trauma patients who received ketamine for multiple rib fractures from 2007 to 2014.

These patients were 60 years old on average, with a median of six rib fractures, many of them bilateral. Almost half had injury severity scores above 15, and most had chest Abbreviated Injury Scores of at least 3. Pneumo- and hemothoraces were common. Patients spent a mean of 6 days in the surgical ICU and 13 days in the hospital.

Along with ketamine, almost all had a morphine or hydromorphone (Dilaudid) patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps, more than half received IV ketorolac (Toradol), and about 40% IV Tylenol. Only 14% had paravertebral or intercostal blocks.

Fourteen patients (10.9%) developed pneumonia, and four (3.1%) died, which compares favorably with outcomes in patients receiving epidurals. Historically, epidural analgesia for multiple traumatic rib fractures has been associated with about an 18% pneumonia rate, and about 9% mortality.

Ketamine side effects were minimal; none of the patients had hallucinations or tachycardia, and three (2.3%) were hypotensive on the drug.

Jacobi’s database did not record how many times patients used their PCA pumps, so the study did not have a direct measure of pain control. The investigators plan to look into this question prospectively.

Even so, when patients hurt from rib fractures, they breathe shallowly, which puts them at risk for pneumonia and death. “We have lower rates” of both than with epidurals, “so you could extrapolate that we must be controlling pain better,” Dr. Getrajdman said.

Ketamine at high doses is an anesthetic, but at lower doses it’s an antagonist of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), and a mild opioid receptor agonist, “so we can give patients the same amount of morphine but achieve a higher analgesic effect,” she said.

Ketamine had been the subject of intense interest in recent years for pain control in a wide variety of settings, as well as for psychiatric and other problems. Clinicaltrials.gov currently lists 138 open investigations of the drug.

Among them is a randomized trial from the Medical College of Wisconsin pitting ketamine against placebo for rib fracture pain following blunt trauma.

Dr. Getrajdman has no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the work.

CHICAGO – Ketamine is a safe and simple alternative to epidural anesthesia for pain control in the setting of multiple rib fractures, investigators from the Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx (N.Y.) concluded after reviewing their experience with the drug.

Epidural analgesia has been the standard for controlling pain after multiple rib fractures, but epidurals are sometimes contraindicated in trauma, especially with back and neck injuries. There’s also a bleeding risk, and the need for an on-call anesthesia team to place them, something not all hospitals have.

Those problems – and the success Jacobi surgeons reported with ketamine pain control after thoracotomy – led the hospital to switch to a ketamine-based rib fracture protocol in 2007.

“As far as we know, we are the only people doing this routinely for multiple rib fractures,” Dr. Joelle Getrajdman, a second-year surgery resident at the medical center, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Patients there with two or more rib fractures get a low-dose peripheral intravenous infusion of ketamine 0.05 mg/kg per hour while in the ICU and step-down unit, along with other pain medications as indicated. The hospital discontinues ketamine once patients leave the step-down unit to prevent diversion for illicit use.

To see how well the protocol has worked, the investigators reviewed all 128 adult trauma patients who received ketamine for multiple rib fractures from 2007 to 2014.

These patients were 60 years old on average, with a median of six rib fractures, many of them bilateral. Almost half had injury severity scores above 15, and most had chest Abbreviated Injury Scores of at least 3. Pneumo- and hemothoraces were common. Patients spent a mean of 6 days in the surgical ICU and 13 days in the hospital.

Along with ketamine, almost all had a morphine or hydromorphone (Dilaudid) patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps, more than half received IV ketorolac (Toradol), and about 40% IV Tylenol. Only 14% had paravertebral or intercostal blocks.

Fourteen patients (10.9%) developed pneumonia, and four (3.1%) died, which compares favorably with outcomes in patients receiving epidurals. Historically, epidural analgesia for multiple traumatic rib fractures has been associated with about an 18% pneumonia rate, and about 9% mortality.

Ketamine side effects were minimal; none of the patients had hallucinations or tachycardia, and three (2.3%) were hypotensive on the drug.

Jacobi’s database did not record how many times patients used their PCA pumps, so the study did not have a direct measure of pain control. The investigators plan to look into this question prospectively.

Even so, when patients hurt from rib fractures, they breathe shallowly, which puts them at risk for pneumonia and death. “We have lower rates” of both than with epidurals, “so you could extrapolate that we must be controlling pain better,” Dr. Getrajdman said.

Ketamine at high doses is an anesthetic, but at lower doses it’s an antagonist of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), and a mild opioid receptor agonist, “so we can give patients the same amount of morphine but achieve a higher analgesic effect,” she said.

Ketamine had been the subject of intense interest in recent years for pain control in a wide variety of settings, as well as for psychiatric and other problems. Clinicaltrials.gov currently lists 138 open investigations of the drug.

Among them is a randomized trial from the Medical College of Wisconsin pitting ketamine against placebo for rib fracture pain following blunt trauma.

Dr. Getrajdman has no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the work.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Patients with multiple rib fractures treated with ketamine for pain control had less risk of pneumonia and death than did patients receiving epidural for pain.

Major finding: Overall, 14 ketamine patients (10.9%) developed pneumonia, and four (3.1%) died.

Data source: Review of 128 rib fracture patients.

Disclosures: The lead investigator has no disclosures, and there was no outside funding for the work.

Essure reoperation risk 10 times higher than tubal ligation

The risk of reoperation is more than 10 times greater after hysteroscopic sterilization with the Essure device than after laparoscopic bilateral tubal ligation, according to an observational cohort study published online Oct. 13 in the BMJ.

The finding raises “a serious safety concern” about Essure, a sterilization coil approved in 2002 for hysteroscopic placement into the fallopian tube, and the subject of a recent Food and Drug Administration safety hearing following more than 5,000 adverse event reports.

“While reoperation following sterilization procedure can be related to unintended pregnancy, the similar risk of unintended pregnancy for both procedures in our study indicated that additional surgeries were performed to alleviate complications such as device migration or incompatibility after surgery,” wrote Dr. Art Sedrakyan and his colleagues from Cornell University, New York (BMJ 2015;351:h5162. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5162).

The Cornell study is believed to be the first to pit Essure against laparoscopic tubal ligation. The investigators compared outcomes of 8,048 patients who underwent hysteroscopic sterilization using the Essure device with 44,278 laparoscopic tubal ligation patients between 2005 and 2013, using a New York state database that captures hospital discharges, outpatient services, ambulatory surgeries, and emergency department records statewide.

Overall, 2.4% of Essure patients, but 0.2% of tubal ligation patients, required reoperation within a year, yielding an odds ratio for Essure of 10.16 (95% C.I., 7.47-13.81), which translates to about 21 additional reoperations per 1,000 Essure patients. Essure patients were eight times more likely to undergo reoperation within 2 years of placement, and six times more likely within 3 years.

Meanwhile, the rate of unintended pregnancy was not statistically different in the two groups, at 1.2% for Essure and 1.1% for tubal ligation within the first year. Essure was also associated with a lower risk of iatrogenic complications within 30 days after surgery, compared with laparoscopic tubal ligation (odds ratio, 0.35).

The use of Essure skyrocketed during the study, from 0.6% of sterilization procedures in 2005 to 25.9% in 2013, with a corresponding drop in tubal ligations. Essure was more likely to be used in women over 40 years old, Medicaid patients, and women with histories of pelvic inflammatory disease, abdominal surgery, and cesarean section. The analysis adjusted for such differences.

Median charges were higher for Essure than for tubal ligation – $7,832 versus $5,068 – despite shorter procedure times, fewer immediate postoperative complications, and less frequent use of general anesthesia.

Although general anesthesia was used less often with Essure, it was still used in about half of patients. “This finding is remarkable in light of the marketing and proposed benefits of avoiding general anesthesia associated with the Essure device,” the investigators wrote.

Tara DiFlumeri, a spokeswoman for Bayer, which manufacturers Essure, said the Cornell study supports the high efficacy rate of Essure. But she also noted that “detection bias” in the study could account for the high reoperation rate identified.

“A required Essure confirmation test is administered 3 months after the procedure to determine whether or not a woman’s fallopian tubes are blocked and she can rely on Essure for birth control. This follow-up test may detect unsatisfactory device placement, resulting in the need for ‘reoperation’ to remove the device and/or complete a tubal ligation if sterilization is still desired. Because there is no confirmation test that could identify potential failure of a laparoscopic tubal ligation procedure, it stands to reason that the comparative reoperation rate would be lower,” she said.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration.

The risk of reoperation is more than 10 times greater after hysteroscopic sterilization with the Essure device than after laparoscopic bilateral tubal ligation, according to an observational cohort study published online Oct. 13 in the BMJ.

The finding raises “a serious safety concern” about Essure, a sterilization coil approved in 2002 for hysteroscopic placement into the fallopian tube, and the subject of a recent Food and Drug Administration safety hearing following more than 5,000 adverse event reports.

“While reoperation following sterilization procedure can be related to unintended pregnancy, the similar risk of unintended pregnancy for both procedures in our study indicated that additional surgeries were performed to alleviate complications such as device migration or incompatibility after surgery,” wrote Dr. Art Sedrakyan and his colleagues from Cornell University, New York (BMJ 2015;351:h5162. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5162).

The Cornell study is believed to be the first to pit Essure against laparoscopic tubal ligation. The investigators compared outcomes of 8,048 patients who underwent hysteroscopic sterilization using the Essure device with 44,278 laparoscopic tubal ligation patients between 2005 and 2013, using a New York state database that captures hospital discharges, outpatient services, ambulatory surgeries, and emergency department records statewide.

Overall, 2.4% of Essure patients, but 0.2% of tubal ligation patients, required reoperation within a year, yielding an odds ratio for Essure of 10.16 (95% C.I., 7.47-13.81), which translates to about 21 additional reoperations per 1,000 Essure patients. Essure patients were eight times more likely to undergo reoperation within 2 years of placement, and six times more likely within 3 years.

Meanwhile, the rate of unintended pregnancy was not statistically different in the two groups, at 1.2% for Essure and 1.1% for tubal ligation within the first year. Essure was also associated with a lower risk of iatrogenic complications within 30 days after surgery, compared with laparoscopic tubal ligation (odds ratio, 0.35).

The use of Essure skyrocketed during the study, from 0.6% of sterilization procedures in 2005 to 25.9% in 2013, with a corresponding drop in tubal ligations. Essure was more likely to be used in women over 40 years old, Medicaid patients, and women with histories of pelvic inflammatory disease, abdominal surgery, and cesarean section. The analysis adjusted for such differences.

Median charges were higher for Essure than for tubal ligation – $7,832 versus $5,068 – despite shorter procedure times, fewer immediate postoperative complications, and less frequent use of general anesthesia.

Although general anesthesia was used less often with Essure, it was still used in about half of patients. “This finding is remarkable in light of the marketing and proposed benefits of avoiding general anesthesia associated with the Essure device,” the investigators wrote.

Tara DiFlumeri, a spokeswoman for Bayer, which manufacturers Essure, said the Cornell study supports the high efficacy rate of Essure. But she also noted that “detection bias” in the study could account for the high reoperation rate identified.

“A required Essure confirmation test is administered 3 months after the procedure to determine whether or not a woman’s fallopian tubes are blocked and she can rely on Essure for birth control. This follow-up test may detect unsatisfactory device placement, resulting in the need for ‘reoperation’ to remove the device and/or complete a tubal ligation if sterilization is still desired. Because there is no confirmation test that could identify potential failure of a laparoscopic tubal ligation procedure, it stands to reason that the comparative reoperation rate would be lower,” she said.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration.

The risk of reoperation is more than 10 times greater after hysteroscopic sterilization with the Essure device than after laparoscopic bilateral tubal ligation, according to an observational cohort study published online Oct. 13 in the BMJ.

The finding raises “a serious safety concern” about Essure, a sterilization coil approved in 2002 for hysteroscopic placement into the fallopian tube, and the subject of a recent Food and Drug Administration safety hearing following more than 5,000 adverse event reports.

“While reoperation following sterilization procedure can be related to unintended pregnancy, the similar risk of unintended pregnancy for both procedures in our study indicated that additional surgeries were performed to alleviate complications such as device migration or incompatibility after surgery,” wrote Dr. Art Sedrakyan and his colleagues from Cornell University, New York (BMJ 2015;351:h5162. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5162).

The Cornell study is believed to be the first to pit Essure against laparoscopic tubal ligation. The investigators compared outcomes of 8,048 patients who underwent hysteroscopic sterilization using the Essure device with 44,278 laparoscopic tubal ligation patients between 2005 and 2013, using a New York state database that captures hospital discharges, outpatient services, ambulatory surgeries, and emergency department records statewide.

Overall, 2.4% of Essure patients, but 0.2% of tubal ligation patients, required reoperation within a year, yielding an odds ratio for Essure of 10.16 (95% C.I., 7.47-13.81), which translates to about 21 additional reoperations per 1,000 Essure patients. Essure patients were eight times more likely to undergo reoperation within 2 years of placement, and six times more likely within 3 years.

Meanwhile, the rate of unintended pregnancy was not statistically different in the two groups, at 1.2% for Essure and 1.1% for tubal ligation within the first year. Essure was also associated with a lower risk of iatrogenic complications within 30 days after surgery, compared with laparoscopic tubal ligation (odds ratio, 0.35).

The use of Essure skyrocketed during the study, from 0.6% of sterilization procedures in 2005 to 25.9% in 2013, with a corresponding drop in tubal ligations. Essure was more likely to be used in women over 40 years old, Medicaid patients, and women with histories of pelvic inflammatory disease, abdominal surgery, and cesarean section. The analysis adjusted for such differences.

Median charges were higher for Essure than for tubal ligation – $7,832 versus $5,068 – despite shorter procedure times, fewer immediate postoperative complications, and less frequent use of general anesthesia.

Although general anesthesia was used less often with Essure, it was still used in about half of patients. “This finding is remarkable in light of the marketing and proposed benefits of avoiding general anesthesia associated with the Essure device,” the investigators wrote.

Tara DiFlumeri, a spokeswoman for Bayer, which manufacturers Essure, said the Cornell study supports the high efficacy rate of Essure. But she also noted that “detection bias” in the study could account for the high reoperation rate identified.

“A required Essure confirmation test is administered 3 months after the procedure to determine whether or not a woman’s fallopian tubes are blocked and she can rely on Essure for birth control. This follow-up test may detect unsatisfactory device placement, resulting in the need for ‘reoperation’ to remove the device and/or complete a tubal ligation if sterilization is still desired. Because there is no confirmation test that could identify potential failure of a laparoscopic tubal ligation procedure, it stands to reason that the comparative reoperation rate would be lower,” she said.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration.

FROM BMJ

Key clinical point: Laparoscopic tubal ligation is as effective as Essure at preventing pregnancy, with fewer reoperations and a lower price tag.

Major finding: Overall, 2.4% of Essure patients, but 0.2% of tubal ligation patients, required reoperation within a year (odds ratio, 10.16), translating to 21 additional reoperations per 1,000 patients.

Data source: Observational cohort study of 8,048 Essure and 44,278 tubal ligation patients between 2005 and 2013.

Disclosures: The investigators reported having no financial disclosures. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration.

VIDEO: Tomosynthesis soon to be standard of care for breast cancer screening

CHICAGO – The uptake of tomosynthesis has been fairly brisk among the nation’s breast cancer screening centers.

There are good reasons for that. In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. Sarah Friedewald, division chief of breast and women’s imaging at Northwestern University, Chicago, explained the procedure; its pluses and minuses; and why it’s likely to be the standard of care for breast cancer screening within 5 years.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – The uptake of tomosynthesis has been fairly brisk among the nation’s breast cancer screening centers.

There are good reasons for that. In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. Sarah Friedewald, division chief of breast and women’s imaging at Northwestern University, Chicago, explained the procedure; its pluses and minuses; and why it’s likely to be the standard of care for breast cancer screening within 5 years.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – The uptake of tomosynthesis has been fairly brisk among the nation’s breast cancer screening centers.

There are good reasons for that. In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. Sarah Friedewald, division chief of breast and women’s imaging at Northwestern University, Chicago, explained the procedure; its pluses and minuses; and why it’s likely to be the standard of care for breast cancer screening within 5 years.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Beta-blockers cut CAS stroke, deaths

CHICAGO – Carotid artery stenting is safer if patients have been on beta-blockers for at least a month beforehand, according to a review of 5,248 stent cases during 2005-2014.

“Compared to nonusers, patients on long-term beta-blockers are at 34% less risk of stroke and death after carotid artery stenting [odds ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.95; P = .025], and this risk reduction is amplified to 65% in patients with postop hypertension [OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.17-0.73; P = .005].

“Beta-blockers significantly reduce the stroke and death risk ... and should be investigated prospectively for potential use during” carotid artery stenting (CAS), said senior investigator Dr. Mahmoud Malas, director of endovascular surgery and associate professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore.

In the study, long-term beta-blocker use was not associated with postprocedure hypotension in the study. Among patients who developed it, however, beta-blockers were associated with a 48% reduction in the risk of stroke or death at 30 days (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28-0.98; P = .43).

“We think [the benefits are due to] up-regulation of adrenergic receptors. We think also there is better baroreceptor reflex sensitivity.” Long-term use of beta-blockers reduces heart rate variability, as well, and decreases the risk of hyperperfusion fourfold, Dr. Malas said at the meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

The researchers looked into the issue because they are trying to find a way to make CAS safer in the wake of the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stent Trial (CREST) and others that have shown increased risk compared with carotid endarterectomy.

The subjects were all captured in SVS’s Vascular Quality Initiative database; 2,152 were not on beta-blockers before CAS, 259 were on them for less than 30 days, and 2,837 were on them for more than 30 days.

There were no statistical between-group differences in lesion sites, approach (femoral in almost all the cases), or contrast volume used in surgery, a marker of case complexity.

Long-term users had more diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure, whereas short-term users were more symptomatic; those and other differences were controlled for on multivariate analysis.

Aspirin, clopidogrel, and statin use were similar between the groups. About two-thirds of the subjects were men, and the average patientage in the study was about 70 years old.

Overall, the 30-day stroke and death rate was 3.4% (minor stroke 1.5%, major 0.9%, and death 1.2%).

Predictors of postoperative stroke or death at 30 days included symptomatic status, age, diabetes, and perioperative hypotension and hypertension. Prior carotid endarterectomy and distal embolic protection were both protective.

The investigators reported that they had no disclosures.

This retrospective study by Malas et al. showed a 34% significant reduction of stroke and death in patients undergoing carotid artery stenting (CAS) who had been on beta-blockade (BB) for at least 1 month beforehand. Presumably, most of these patients were already on longstanding BB. Current cardiology guidelines recommend the continuation of established BB for surgical patients, and this may also mitigate the cardiac risk in CAS patients. The short-term use of BB has been shown to have risk during and after noncardiac surgery and, intuitively, could lead to severe hypotension during CAS. The reason for the stroke reduction seen with well-established BB is not clearly understood.

This study begs the question: Should every patient being considered for CAS be on BB at least 1 month before the intervention, even those with few or no cardiac risk factors? If so, then it would be difficult to advocate for CAS in acutely symptomatic patients not already on a BB, thus further limiting the usefulness of this procedure.

Dr. Mark L. Friedell is chairman of the department of Surgery, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine.

This retrospective study by Malas et al. showed a 34% significant reduction of stroke and death in patients undergoing carotid artery stenting (CAS) who had been on beta-blockade (BB) for at least 1 month beforehand. Presumably, most of these patients were already on longstanding BB. Current cardiology guidelines recommend the continuation of established BB for surgical patients, and this may also mitigate the cardiac risk in CAS patients. The short-term use of BB has been shown to have risk during and after noncardiac surgery and, intuitively, could lead to severe hypotension during CAS. The reason for the stroke reduction seen with well-established BB is not clearly understood.

This study begs the question: Should every patient being considered for CAS be on BB at least 1 month before the intervention, even those with few or no cardiac risk factors? If so, then it would be difficult to advocate for CAS in acutely symptomatic patients not already on a BB, thus further limiting the usefulness of this procedure.

Dr. Mark L. Friedell is chairman of the department of Surgery, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine.

This retrospective study by Malas et al. showed a 34% significant reduction of stroke and death in patients undergoing carotid artery stenting (CAS) who had been on beta-blockade (BB) for at least 1 month beforehand. Presumably, most of these patients were already on longstanding BB. Current cardiology guidelines recommend the continuation of established BB for surgical patients, and this may also mitigate the cardiac risk in CAS patients. The short-term use of BB has been shown to have risk during and after noncardiac surgery and, intuitively, could lead to severe hypotension during CAS. The reason for the stroke reduction seen with well-established BB is not clearly understood.

This study begs the question: Should every patient being considered for CAS be on BB at least 1 month before the intervention, even those with few or no cardiac risk factors? If so, then it would be difficult to advocate for CAS in acutely symptomatic patients not already on a BB, thus further limiting the usefulness of this procedure.

Dr. Mark L. Friedell is chairman of the department of Surgery, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine.

CHICAGO – Carotid artery stenting is safer if patients have been on beta-blockers for at least a month beforehand, according to a review of 5,248 stent cases during 2005-2014.

“Compared to nonusers, patients on long-term beta-blockers are at 34% less risk of stroke and death after carotid artery stenting [odds ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.95; P = .025], and this risk reduction is amplified to 65% in patients with postop hypertension [OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.17-0.73; P = .005].

“Beta-blockers significantly reduce the stroke and death risk ... and should be investigated prospectively for potential use during” carotid artery stenting (CAS), said senior investigator Dr. Mahmoud Malas, director of endovascular surgery and associate professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore.

In the study, long-term beta-blocker use was not associated with postprocedure hypotension in the study. Among patients who developed it, however, beta-blockers were associated with a 48% reduction in the risk of stroke or death at 30 days (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28-0.98; P = .43).

“We think [the benefits are due to] up-regulation of adrenergic receptors. We think also there is better baroreceptor reflex sensitivity.” Long-term use of beta-blockers reduces heart rate variability, as well, and decreases the risk of hyperperfusion fourfold, Dr. Malas said at the meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

The researchers looked into the issue because they are trying to find a way to make CAS safer in the wake of the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stent Trial (CREST) and others that have shown increased risk compared with carotid endarterectomy.

The subjects were all captured in SVS’s Vascular Quality Initiative database; 2,152 were not on beta-blockers before CAS, 259 were on them for less than 30 days, and 2,837 were on them for more than 30 days.

There were no statistical between-group differences in lesion sites, approach (femoral in almost all the cases), or contrast volume used in surgery, a marker of case complexity.

Long-term users had more diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure, whereas short-term users were more symptomatic; those and other differences were controlled for on multivariate analysis.

Aspirin, clopidogrel, and statin use were similar between the groups. About two-thirds of the subjects were men, and the average patientage in the study was about 70 years old.

Overall, the 30-day stroke and death rate was 3.4% (minor stroke 1.5%, major 0.9%, and death 1.2%).

Predictors of postoperative stroke or death at 30 days included symptomatic status, age, diabetes, and perioperative hypotension and hypertension. Prior carotid endarterectomy and distal embolic protection were both protective.

The investigators reported that they had no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Carotid artery stenting is safer if patients have been on beta-blockers for at least a month beforehand, according to a review of 5,248 stent cases during 2005-2014.

“Compared to nonusers, patients on long-term beta-blockers are at 34% less risk of stroke and death after carotid artery stenting [odds ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.95; P = .025], and this risk reduction is amplified to 65% in patients with postop hypertension [OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.17-0.73; P = .005].

“Beta-blockers significantly reduce the stroke and death risk ... and should be investigated prospectively for potential use during” carotid artery stenting (CAS), said senior investigator Dr. Mahmoud Malas, director of endovascular surgery and associate professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore.

In the study, long-term beta-blocker use was not associated with postprocedure hypotension in the study. Among patients who developed it, however, beta-blockers were associated with a 48% reduction in the risk of stroke or death at 30 days (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28-0.98; P = .43).

“We think [the benefits are due to] up-regulation of adrenergic receptors. We think also there is better baroreceptor reflex sensitivity.” Long-term use of beta-blockers reduces heart rate variability, as well, and decreases the risk of hyperperfusion fourfold, Dr. Malas said at the meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

The researchers looked into the issue because they are trying to find a way to make CAS safer in the wake of the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stent Trial (CREST) and others that have shown increased risk compared with carotid endarterectomy.

The subjects were all captured in SVS’s Vascular Quality Initiative database; 2,152 were not on beta-blockers before CAS, 259 were on them for less than 30 days, and 2,837 were on them for more than 30 days.

There were no statistical between-group differences in lesion sites, approach (femoral in almost all the cases), or contrast volume used in surgery, a marker of case complexity.

Long-term users had more diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure, whereas short-term users were more symptomatic; those and other differences were controlled for on multivariate analysis.

Aspirin, clopidogrel, and statin use were similar between the groups. About two-thirds of the subjects were men, and the average patientage in the study was about 70 years old.

Overall, the 30-day stroke and death rate was 3.4% (minor stroke 1.5%, major 0.9%, and death 1.2%).

Predictors of postoperative stroke or death at 30 days included symptomatic status, age, diabetes, and perioperative hypotension and hypertension. Prior carotid endarterectomy and distal embolic protection were both protective.

The investigators reported that they had no disclosures.

VIDEO: Take steps now to keep gram-negative resistance at bay

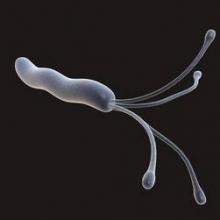

CHICAGO – Gram-negative bacteria are the new frontier of antimicrobial resistance.

Resistant Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and other organisms are increasingly common in Asia, South America, and southern Europe, but haven’t quite established themselves yet in the United States.

In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. John Mazuski, a professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis, explained what’s known so far, and the steps to take now to keep the organisms in check.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Gram-negative bacteria are the new frontier of antimicrobial resistance.

Resistant Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and other organisms are increasingly common in Asia, South America, and southern Europe, but haven’t quite established themselves yet in the United States.

In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. John Mazuski, a professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis, explained what’s known so far, and the steps to take now to keep the organisms in check.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Gram-negative bacteria are the new frontier of antimicrobial resistance.

Resistant Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and other organisms are increasingly common in Asia, South America, and southern Europe, but haven’t quite established themselves yet in the United States.

In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. John Mazuski, a professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis, explained what’s known so far, and the steps to take now to keep the organisms in check.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

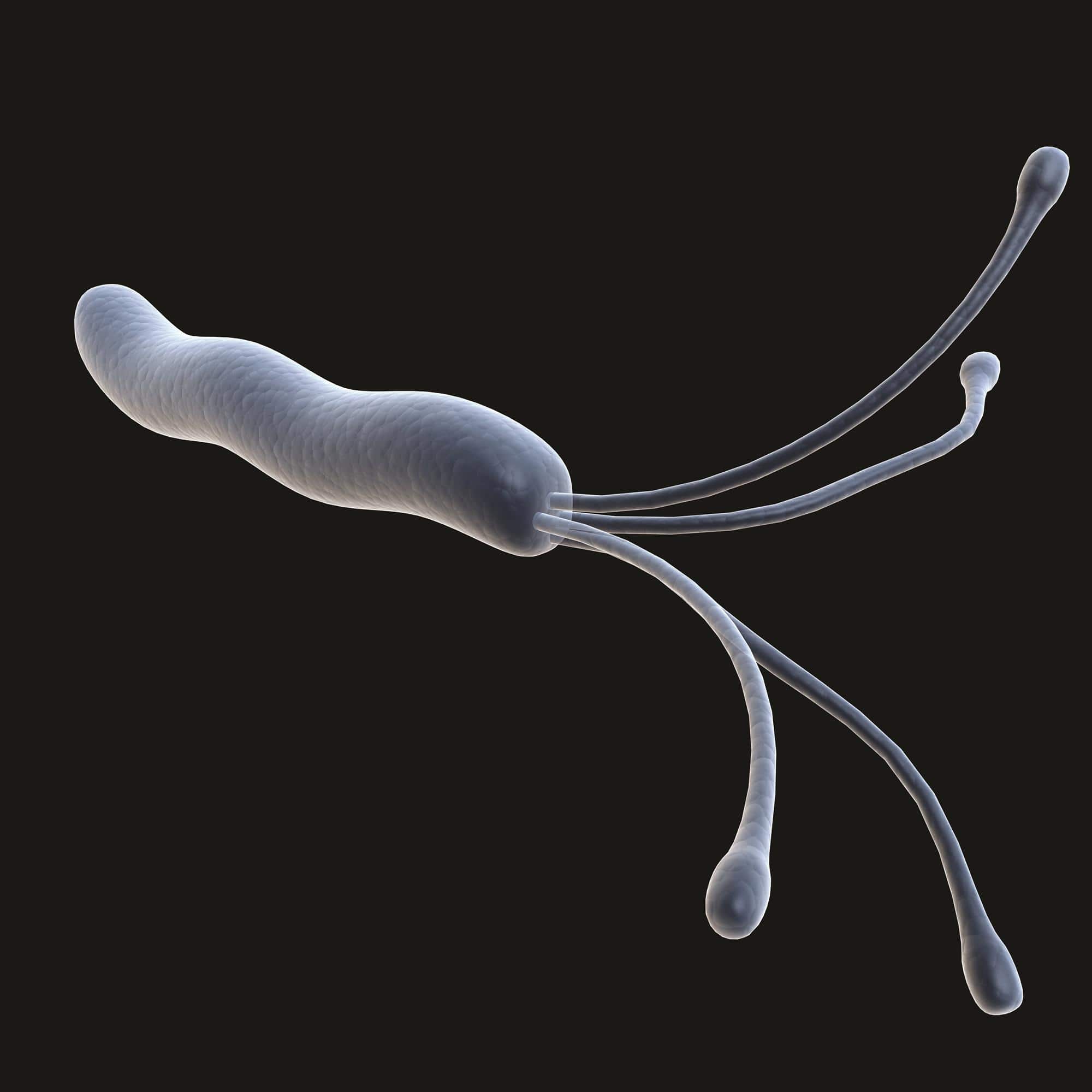

AGA: Biopsy normal gastric mucosa for H. pylori during esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Obtain gastric biopsies to check for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients undergoing routine esophagogastroduodenoscopy for dyspepsia, even if their mucosa appears normal and they’re immunocompetent, the American Gastroenterological Association advises in a new guideline for upper gastrointestinal biopsy to evaluate dyspepsia in the adult patient in the absence of visible mucosal lesions, which was published in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

The group suggests taking five biopsy specimens from the gastric body and antrum using the updated Sydney System; placing the samples in the same jar; and relying on routine staining to make the call. “Experienced GI pathologists can determine the anatomic location of biopsy specimens sent from the stomach, which obviates the need for” – and cost of – “separating specimens into multiple jars.” They can also identify “virtually all cases of H. pylori .... Therefore, routine use of ancillary special staining” needlessly adds cost, said the guideline authors, led by Dr. Yu-Xiao Yang of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia (Gastroenterology. 2015 Aug 14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.039).

The group also counsels against routine biopsies of normal-appearing esophagus and gastroesophageal junctions in patients undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for dyspepsia, regardless of their immune status.