User login

NCCI agrees to change recent edits regarding reconstructive procedures done at the time of vaginal hysterectomy

On October 1, 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) implemented a number of new coding pair edits that significantly restricted the types of surgical procedures that could be billed at the same time as vaginal hysterectomy. Most importantly, the new edits did not allow for combined anterior and posterior (AP) vaginal repair (57260) and apical vaginal suspensions (57282, 57283) to be separately billed and reimbursed when performed by the same surgeon and done in the same surgical session as a vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy. I initially reported on these changes in the January 2015 issue of OBG Management (“Recent NCCI edits have significantly impacted billing and reimbursement for vaginal hysterectomy”).

AUGS, ACOG, and others responded, and were heard

As a result of an intensive effort, the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS), in conjunction with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS), and other professional societies, NCCI has agreed to change or modify a significant number of these pair edits.

As described in my earlier article, NCCI periodically reviews multiple surgical procedures performed in the same setting by a single surgeon to determine whether there is a significant overlap in services and therefore, in their opinion, redundant payment. Most significantly, CMS agreed with the argument made by the AUGS task force that it was inappropriate to bundle combined colporrhaphy with the various vaginal hysterectomy codes. These pair edits will no longer exist, and it is possible to bill separately for an AP repair performed in the same session as a vaginal hysterectomy—and expect additional payment for this procedure (subject to the multiple procedure reduction modifier -51).

Don’t miss out on reimbursement for your prior surgeries

It is important to recognize that this decision will be retroactive to October 1, 2014, which means that surgeons can resubmit charges for procedures performed between October 1, 2014, and March 31, 2015.

An exception to this rule is when the surgeon performs, and bills for, a vaginal hysterectomy code that includes enterocele repair, such as 58263. In these circumstances, the combined colporrhaphy remains bundled with the vaginal hysterectomy, unless a special modifier is used.

When can a modifier be used?

With regard to the majority of the other pair edits, CMS still contends that the edits are appropriate; however, they have modified the edits to allow for these procedures to be billed separately when the surgeon feels that substantial additional work has been performed. For example, CMS holds the position that all vaginal hysterectomies include some type of apical fixation to the surrounding tissues—such as fixation of the vaginal cuff at the time of closure to the distal uterosacral ligaments. However, it will allow for the additional billing for a more extensive vaginal apical suspension (such as a high uterosacral suspension or sacrospinous ligament suspension) as long as the surgeon documents the additional work performed and submits the claim using one of the NCCI-approved surgical modifiers. In this particular circumstance, the -59 modifier is the appropriate choice.

The AUGS task force also had objected to the bundling of a group of codes that, in the society’s opinion, were distinctly unrelated, such as a laparoscopic hysterectomy or vaginal hysterectomy combined with a sacral colpopexy performed through an open abdominal incision. CMS recognizes that these codes are used infrequently together and has therefore assumed that they may be billed in error. AUGS, however, has pointed out that, on occasion, a laparoscopic hysterectomy with an intended laparoscopic colpopexy may be converted to an open procedure due to a complication or technical difficulty, in which case the use of both codes would be appropriate.

The NCCI response was to keep the code pairs bundled but allow for billing with the -59 modifier.

We have cause for cheer, but bundling edits continue

Overall, these changes in pair edits represent a significant improvement in reimbursement for gynecologic surgeons, relative to the changes that went into effect on October 1. A more detailed explanation and list of the codes affected can be found on the AUGS Web site (http://www.augs.org). I emphasize again that these changes not only are in effect as of April 1, 2015, but also are retroactive to October 1, 2014.

Unfortunately, while AUGS and ACOG were advocating for these changes on behalf of gynecologists, NCCI recently has approved 6 additional pair edits that will go into effect on July 1. These changes specifically involve related procedures done at the time of vaginal hysterectomy with enterocele repair (58263, 58270 and 58294, 58292) and posterior vaginal repair (57250).

While these codes will be considered bundled on that date, NCCI will allow the use of the -59 modifier to override the bundle in clinically appropriate cases. The other code pairs affected are the 2 vaginal hysterectomy codes with colpourethropexy (58267, 58293) with anterior repair (57240). Again, these code pairs will be bundled, and it will require the use of a modifier to override this bundle.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

On October 1, 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) implemented a number of new coding pair edits that significantly restricted the types of surgical procedures that could be billed at the same time as vaginal hysterectomy. Most importantly, the new edits did not allow for combined anterior and posterior (AP) vaginal repair (57260) and apical vaginal suspensions (57282, 57283) to be separately billed and reimbursed when performed by the same surgeon and done in the same surgical session as a vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy. I initially reported on these changes in the January 2015 issue of OBG Management (“Recent NCCI edits have significantly impacted billing and reimbursement for vaginal hysterectomy”).

AUGS, ACOG, and others responded, and were heard

As a result of an intensive effort, the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS), in conjunction with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS), and other professional societies, NCCI has agreed to change or modify a significant number of these pair edits.

As described in my earlier article, NCCI periodically reviews multiple surgical procedures performed in the same setting by a single surgeon to determine whether there is a significant overlap in services and therefore, in their opinion, redundant payment. Most significantly, CMS agreed with the argument made by the AUGS task force that it was inappropriate to bundle combined colporrhaphy with the various vaginal hysterectomy codes. These pair edits will no longer exist, and it is possible to bill separately for an AP repair performed in the same session as a vaginal hysterectomy—and expect additional payment for this procedure (subject to the multiple procedure reduction modifier -51).

Don’t miss out on reimbursement for your prior surgeries

It is important to recognize that this decision will be retroactive to October 1, 2014, which means that surgeons can resubmit charges for procedures performed between October 1, 2014, and March 31, 2015.

An exception to this rule is when the surgeon performs, and bills for, a vaginal hysterectomy code that includes enterocele repair, such as 58263. In these circumstances, the combined colporrhaphy remains bundled with the vaginal hysterectomy, unless a special modifier is used.

When can a modifier be used?

With regard to the majority of the other pair edits, CMS still contends that the edits are appropriate; however, they have modified the edits to allow for these procedures to be billed separately when the surgeon feels that substantial additional work has been performed. For example, CMS holds the position that all vaginal hysterectomies include some type of apical fixation to the surrounding tissues—such as fixation of the vaginal cuff at the time of closure to the distal uterosacral ligaments. However, it will allow for the additional billing for a more extensive vaginal apical suspension (such as a high uterosacral suspension or sacrospinous ligament suspension) as long as the surgeon documents the additional work performed and submits the claim using one of the NCCI-approved surgical modifiers. In this particular circumstance, the -59 modifier is the appropriate choice.

The AUGS task force also had objected to the bundling of a group of codes that, in the society’s opinion, were distinctly unrelated, such as a laparoscopic hysterectomy or vaginal hysterectomy combined with a sacral colpopexy performed through an open abdominal incision. CMS recognizes that these codes are used infrequently together and has therefore assumed that they may be billed in error. AUGS, however, has pointed out that, on occasion, a laparoscopic hysterectomy with an intended laparoscopic colpopexy may be converted to an open procedure due to a complication or technical difficulty, in which case the use of both codes would be appropriate.

The NCCI response was to keep the code pairs bundled but allow for billing with the -59 modifier.

We have cause for cheer, but bundling edits continue

Overall, these changes in pair edits represent a significant improvement in reimbursement for gynecologic surgeons, relative to the changes that went into effect on October 1. A more detailed explanation and list of the codes affected can be found on the AUGS Web site (http://www.augs.org). I emphasize again that these changes not only are in effect as of April 1, 2015, but also are retroactive to October 1, 2014.

Unfortunately, while AUGS and ACOG were advocating for these changes on behalf of gynecologists, NCCI recently has approved 6 additional pair edits that will go into effect on July 1. These changes specifically involve related procedures done at the time of vaginal hysterectomy with enterocele repair (58263, 58270 and 58294, 58292) and posterior vaginal repair (57250).

While these codes will be considered bundled on that date, NCCI will allow the use of the -59 modifier to override the bundle in clinically appropriate cases. The other code pairs affected are the 2 vaginal hysterectomy codes with colpourethropexy (58267, 58293) with anterior repair (57240). Again, these code pairs will be bundled, and it will require the use of a modifier to override this bundle.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

On October 1, 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) implemented a number of new coding pair edits that significantly restricted the types of surgical procedures that could be billed at the same time as vaginal hysterectomy. Most importantly, the new edits did not allow for combined anterior and posterior (AP) vaginal repair (57260) and apical vaginal suspensions (57282, 57283) to be separately billed and reimbursed when performed by the same surgeon and done in the same surgical session as a vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy. I initially reported on these changes in the January 2015 issue of OBG Management (“Recent NCCI edits have significantly impacted billing and reimbursement for vaginal hysterectomy”).

AUGS, ACOG, and others responded, and were heard

As a result of an intensive effort, the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS), in conjunction with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS), and other professional societies, NCCI has agreed to change or modify a significant number of these pair edits.

As described in my earlier article, NCCI periodically reviews multiple surgical procedures performed in the same setting by a single surgeon to determine whether there is a significant overlap in services and therefore, in their opinion, redundant payment. Most significantly, CMS agreed with the argument made by the AUGS task force that it was inappropriate to bundle combined colporrhaphy with the various vaginal hysterectomy codes. These pair edits will no longer exist, and it is possible to bill separately for an AP repair performed in the same session as a vaginal hysterectomy—and expect additional payment for this procedure (subject to the multiple procedure reduction modifier -51).

Don’t miss out on reimbursement for your prior surgeries

It is important to recognize that this decision will be retroactive to October 1, 2014, which means that surgeons can resubmit charges for procedures performed between October 1, 2014, and March 31, 2015.

An exception to this rule is when the surgeon performs, and bills for, a vaginal hysterectomy code that includes enterocele repair, such as 58263. In these circumstances, the combined colporrhaphy remains bundled with the vaginal hysterectomy, unless a special modifier is used.

When can a modifier be used?

With regard to the majority of the other pair edits, CMS still contends that the edits are appropriate; however, they have modified the edits to allow for these procedures to be billed separately when the surgeon feels that substantial additional work has been performed. For example, CMS holds the position that all vaginal hysterectomies include some type of apical fixation to the surrounding tissues—such as fixation of the vaginal cuff at the time of closure to the distal uterosacral ligaments. However, it will allow for the additional billing for a more extensive vaginal apical suspension (such as a high uterosacral suspension or sacrospinous ligament suspension) as long as the surgeon documents the additional work performed and submits the claim using one of the NCCI-approved surgical modifiers. In this particular circumstance, the -59 modifier is the appropriate choice.

The AUGS task force also had objected to the bundling of a group of codes that, in the society’s opinion, were distinctly unrelated, such as a laparoscopic hysterectomy or vaginal hysterectomy combined with a sacral colpopexy performed through an open abdominal incision. CMS recognizes that these codes are used infrequently together and has therefore assumed that they may be billed in error. AUGS, however, has pointed out that, on occasion, a laparoscopic hysterectomy with an intended laparoscopic colpopexy may be converted to an open procedure due to a complication or technical difficulty, in which case the use of both codes would be appropriate.

The NCCI response was to keep the code pairs bundled but allow for billing with the -59 modifier.

We have cause for cheer, but bundling edits continue

Overall, these changes in pair edits represent a significant improvement in reimbursement for gynecologic surgeons, relative to the changes that went into effect on October 1. A more detailed explanation and list of the codes affected can be found on the AUGS Web site (http://www.augs.org). I emphasize again that these changes not only are in effect as of April 1, 2015, but also are retroactive to October 1, 2014.

Unfortunately, while AUGS and ACOG were advocating for these changes on behalf of gynecologists, NCCI recently has approved 6 additional pair edits that will go into effect on July 1. These changes specifically involve related procedures done at the time of vaginal hysterectomy with enterocele repair (58263, 58270 and 58294, 58292) and posterior vaginal repair (57250).

While these codes will be considered bundled on that date, NCCI will allow the use of the -59 modifier to override the bundle in clinically appropriate cases. The other code pairs affected are the 2 vaginal hysterectomy codes with colpourethropexy (58267, 58293) with anterior repair (57240). Again, these code pairs will be bundled, and it will require the use of a modifier to override this bundle.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Recent NCCI edits have significantly impacted billing and reimbursement for vaginal hysterectomy

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) to promote national correct coding methodologies and to control what it considers to be duplicative and improper coding of multiple procedures performed in a single setting in Part B claims.

Since 1996, Medicare has used NCCI edits to limit additional payments for two procedures that were thought to be similar because of anatomic and temporal considerations. For example, billing for both lysis of adhesions and total abdominal hysterectomy in the same operation has long been denied, as preoperative and postoperative care typically are the same and the intraservice times are not appreciably different. Both require opening and closing of the same incision, and so on.

The most recent set of NCCI edits, effective October 1, 2014, “bundles” procedures for high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension (also known as vaginal colpopexy—intraperitoneal approach—CPT code 57283) and combined colporrhaphy (code 57260) when they are performed at the same time as a vaginal hysterectomy. Previously, these procedures could be billed together and separately paid for by Medicare, although the additional procedures were subjected to a -51 modifier, designating multiple procedures, which reduced the payment for them by approximately 50%.

How the NCCI makes its determinations

The NCCI develops coding policies, or “edits,” by analyzing coding conventions and reviewing standard medical and surgical practices. It reviews current coding practices and guidelines developed by national societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), but the NCCI has the power to decide what surgical procedures get “bundled” with other procedures that commonly are performed in the same setting. As a general rule, the NCCI feels that procedures performed through the same incision, in close anatomic proximity, and by the same surgeon should not be billed separately. The NCCI develops and implements its coding edits on a quarterly basis, after notifying the medical societies most likely to be affected by the new bundles and soliciting feedback.

As gynecologic surgeons, we are familiar with the multitude of bundles that already exist for abdominal and laparoscopic procedures—lysis of adhesions, ureterolysis, abdominal enterocele repair, removal of both tubes and ovaries (as opposed to unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy)—which have been around for decades. However, until recently, vaginal surgical procedures were not bundled but were billed “a la carte.”

Because the October 1 edits deny separate payment when combined colporrhaphy and high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension are performed alongside vaginal hysterectomy, gynecologic surgeons now get paid only for the vaginal hysterectomy. These edits are likely to have a profound impact on practicing vaginal surgeons, especially subspecialists in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.

Procedures that can no longer be billed when performed at the same time as a vaginal hysterectomy include:

- combined anterior and posterior colporrhaphy (code 57260)

- abdominal sacrocolpopexy (57280)

- extraperitoneal vaginal colpopexy (eg, sacrospinous ligament suspension, or SSLS, 57282)

- intraperitoneal vaginal colpopexy (eg, high uterosacral ligament suspension, 57283)

- abdominal paravaginal repair (57284).

For a full version of current edits, see the CMS Web site at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/NationalCorrectCodInitEd/NCCI-Coding-Edits.html.

AUGS, ACOG, and others respond to the edits

Since implementation of the October 1 edits, both ACOG and the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) have received numerous complaints and protests from members. Both societies reviewed and strongly disagreed with the proposed edits before their implementation, but NCCI ultimately decided to implement them.

In cooperation with ACOG and several other national medical societies, such as the Society for Gynecologic Surgeons and the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction, AUGS formed a task force that already has engaged CMS in a series of communications focused on changing or reversing some of these edits.

This task force, under the leadership of AUGS, believes that CMS and NCCI do not fully understand the complexity of vaginal reconstruction performed for advanced pelvic organ prolapse, or the fact that vaginal hysterectomy is an extirpative procedure that often is required to facilitate the more time-consuming reconstructive procedures. Furthermore, the reconstructive procedures require separate entry and closure of different surgical spaces (eg, rectovaginal, vesicovaginal). In addition, the surgical risks and postoperative care often are more complex than they are when a simple vaginal hysterectomy is performed for benign gynecologic indications other than pelvic organ prolapse.

Thus far, both NCCI and CMS have listened to our objections, indicated that they understand them, and agreed to reexamine the appropriateness of the bundles. As of press time, however, CMS has not announced any plans to change or reverse any of these edits.

The October 1 edits are not the only ones that adversely affect the gynecologic surgeon. As of January 1, 2015, NCCI and CMS implemented another set of edits that no longer allow separate billing and reimbursement for cystoscopy (52000) performed at the time of pelvic surgery, when the purpose of the procedure is to assure the surgeon that the ureters and urinary bladder are free of injury. However, cystoscopy may be billed separately when the primary purpose differs from that scenario.

ACOG and AUGS intend to stay in discussion with CMS regarding the appropriateness of the most recent edits. If any edits are reversed, the decision will be retroactive to the October 1, 2014, date. Stay tuned for the final decision.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) to promote national correct coding methodologies and to control what it considers to be duplicative and improper coding of multiple procedures performed in a single setting in Part B claims.

Since 1996, Medicare has used NCCI edits to limit additional payments for two procedures that were thought to be similar because of anatomic and temporal considerations. For example, billing for both lysis of adhesions and total abdominal hysterectomy in the same operation has long been denied, as preoperative and postoperative care typically are the same and the intraservice times are not appreciably different. Both require opening and closing of the same incision, and so on.

The most recent set of NCCI edits, effective October 1, 2014, “bundles” procedures for high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension (also known as vaginal colpopexy—intraperitoneal approach—CPT code 57283) and combined colporrhaphy (code 57260) when they are performed at the same time as a vaginal hysterectomy. Previously, these procedures could be billed together and separately paid for by Medicare, although the additional procedures were subjected to a -51 modifier, designating multiple procedures, which reduced the payment for them by approximately 50%.

How the NCCI makes its determinations

The NCCI develops coding policies, or “edits,” by analyzing coding conventions and reviewing standard medical and surgical practices. It reviews current coding practices and guidelines developed by national societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), but the NCCI has the power to decide what surgical procedures get “bundled” with other procedures that commonly are performed in the same setting. As a general rule, the NCCI feels that procedures performed through the same incision, in close anatomic proximity, and by the same surgeon should not be billed separately. The NCCI develops and implements its coding edits on a quarterly basis, after notifying the medical societies most likely to be affected by the new bundles and soliciting feedback.

As gynecologic surgeons, we are familiar with the multitude of bundles that already exist for abdominal and laparoscopic procedures—lysis of adhesions, ureterolysis, abdominal enterocele repair, removal of both tubes and ovaries (as opposed to unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy)—which have been around for decades. However, until recently, vaginal surgical procedures were not bundled but were billed “a la carte.”

Because the October 1 edits deny separate payment when combined colporrhaphy and high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension are performed alongside vaginal hysterectomy, gynecologic surgeons now get paid only for the vaginal hysterectomy. These edits are likely to have a profound impact on practicing vaginal surgeons, especially subspecialists in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.

Procedures that can no longer be billed when performed at the same time as a vaginal hysterectomy include:

- combined anterior and posterior colporrhaphy (code 57260)

- abdominal sacrocolpopexy (57280)

- extraperitoneal vaginal colpopexy (eg, sacrospinous ligament suspension, or SSLS, 57282)

- intraperitoneal vaginal colpopexy (eg, high uterosacral ligament suspension, 57283)

- abdominal paravaginal repair (57284).

For a full version of current edits, see the CMS Web site at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/NationalCorrectCodInitEd/NCCI-Coding-Edits.html.

AUGS, ACOG, and others respond to the edits

Since implementation of the October 1 edits, both ACOG and the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) have received numerous complaints and protests from members. Both societies reviewed and strongly disagreed with the proposed edits before their implementation, but NCCI ultimately decided to implement them.

In cooperation with ACOG and several other national medical societies, such as the Society for Gynecologic Surgeons and the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction, AUGS formed a task force that already has engaged CMS in a series of communications focused on changing or reversing some of these edits.

This task force, under the leadership of AUGS, believes that CMS and NCCI do not fully understand the complexity of vaginal reconstruction performed for advanced pelvic organ prolapse, or the fact that vaginal hysterectomy is an extirpative procedure that often is required to facilitate the more time-consuming reconstructive procedures. Furthermore, the reconstructive procedures require separate entry and closure of different surgical spaces (eg, rectovaginal, vesicovaginal). In addition, the surgical risks and postoperative care often are more complex than they are when a simple vaginal hysterectomy is performed for benign gynecologic indications other than pelvic organ prolapse.

Thus far, both NCCI and CMS have listened to our objections, indicated that they understand them, and agreed to reexamine the appropriateness of the bundles. As of press time, however, CMS has not announced any plans to change or reverse any of these edits.

The October 1 edits are not the only ones that adversely affect the gynecologic surgeon. As of January 1, 2015, NCCI and CMS implemented another set of edits that no longer allow separate billing and reimbursement for cystoscopy (52000) performed at the time of pelvic surgery, when the purpose of the procedure is to assure the surgeon that the ureters and urinary bladder are free of injury. However, cystoscopy may be billed separately when the primary purpose differs from that scenario.

ACOG and AUGS intend to stay in discussion with CMS regarding the appropriateness of the most recent edits. If any edits are reversed, the decision will be retroactive to the October 1, 2014, date. Stay tuned for the final decision.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) to promote national correct coding methodologies and to control what it considers to be duplicative and improper coding of multiple procedures performed in a single setting in Part B claims.

Since 1996, Medicare has used NCCI edits to limit additional payments for two procedures that were thought to be similar because of anatomic and temporal considerations. For example, billing for both lysis of adhesions and total abdominal hysterectomy in the same operation has long been denied, as preoperative and postoperative care typically are the same and the intraservice times are not appreciably different. Both require opening and closing of the same incision, and so on.

The most recent set of NCCI edits, effective October 1, 2014, “bundles” procedures for high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension (also known as vaginal colpopexy—intraperitoneal approach—CPT code 57283) and combined colporrhaphy (code 57260) when they are performed at the same time as a vaginal hysterectomy. Previously, these procedures could be billed together and separately paid for by Medicare, although the additional procedures were subjected to a -51 modifier, designating multiple procedures, which reduced the payment for them by approximately 50%.

How the NCCI makes its determinations

The NCCI develops coding policies, or “edits,” by analyzing coding conventions and reviewing standard medical and surgical practices. It reviews current coding practices and guidelines developed by national societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), but the NCCI has the power to decide what surgical procedures get “bundled” with other procedures that commonly are performed in the same setting. As a general rule, the NCCI feels that procedures performed through the same incision, in close anatomic proximity, and by the same surgeon should not be billed separately. The NCCI develops and implements its coding edits on a quarterly basis, after notifying the medical societies most likely to be affected by the new bundles and soliciting feedback.

As gynecologic surgeons, we are familiar with the multitude of bundles that already exist for abdominal and laparoscopic procedures—lysis of adhesions, ureterolysis, abdominal enterocele repair, removal of both tubes and ovaries (as opposed to unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy)—which have been around for decades. However, until recently, vaginal surgical procedures were not bundled but were billed “a la carte.”

Because the October 1 edits deny separate payment when combined colporrhaphy and high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension are performed alongside vaginal hysterectomy, gynecologic surgeons now get paid only for the vaginal hysterectomy. These edits are likely to have a profound impact on practicing vaginal surgeons, especially subspecialists in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.

Procedures that can no longer be billed when performed at the same time as a vaginal hysterectomy include:

- combined anterior and posterior colporrhaphy (code 57260)

- abdominal sacrocolpopexy (57280)

- extraperitoneal vaginal colpopexy (eg, sacrospinous ligament suspension, or SSLS, 57282)

- intraperitoneal vaginal colpopexy (eg, high uterosacral ligament suspension, 57283)

- abdominal paravaginal repair (57284).

For a full version of current edits, see the CMS Web site at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/NationalCorrectCodInitEd/NCCI-Coding-Edits.html.

AUGS, ACOG, and others respond to the edits

Since implementation of the October 1 edits, both ACOG and the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) have received numerous complaints and protests from members. Both societies reviewed and strongly disagreed with the proposed edits before their implementation, but NCCI ultimately decided to implement them.

In cooperation with ACOG and several other national medical societies, such as the Society for Gynecologic Surgeons and the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction, AUGS formed a task force that already has engaged CMS in a series of communications focused on changing or reversing some of these edits.

This task force, under the leadership of AUGS, believes that CMS and NCCI do not fully understand the complexity of vaginal reconstruction performed for advanced pelvic organ prolapse, or the fact that vaginal hysterectomy is an extirpative procedure that often is required to facilitate the more time-consuming reconstructive procedures. Furthermore, the reconstructive procedures require separate entry and closure of different surgical spaces (eg, rectovaginal, vesicovaginal). In addition, the surgical risks and postoperative care often are more complex than they are when a simple vaginal hysterectomy is performed for benign gynecologic indications other than pelvic organ prolapse.

Thus far, both NCCI and CMS have listened to our objections, indicated that they understand them, and agreed to reexamine the appropriateness of the bundles. As of press time, however, CMS has not announced any plans to change or reverse any of these edits.

The October 1 edits are not the only ones that adversely affect the gynecologic surgeon. As of January 1, 2015, NCCI and CMS implemented another set of edits that no longer allow separate billing and reimbursement for cystoscopy (52000) performed at the time of pelvic surgery, when the purpose of the procedure is to assure the surgeon that the ureters and urinary bladder are free of injury. However, cystoscopy may be billed separately when the primary purpose differs from that scenario.

ACOG and AUGS intend to stay in discussion with CMS regarding the appropriateness of the most recent edits. If any edits are reversed, the decision will be retroactive to the October 1, 2014, date. Stay tuned for the final decision.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Cone biopsy: perfecting the procedure

- Cone biopsy typically includes the removal of the entire squamocolumnar junction of the cervix, generally agreed to be the site of origin of squamous cell carcinoma.

- Inject a premixed solution of 2% xylocaine and epinephrine in a concentration of 1:200,000 into the cervical stroma at 12 o’clock outside the intended margin.

- For a “cold-knife” cone, use a #11 surgical blade to begin a circular incision starting at 12 o’clock on the face of the cervix.

Cone biopsy of the cervix has been used for more than a century to rule out the presence of invasive carcinoma in women with squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL). And while less invasive techniques such as colposcopy and loop electrosurgical excision procedures (LEEP) have reduced the need for diagnostic conization dramatically, cervical cone biopsy becomes necessary when these techniques prove inadequate.

Indications

When routine screening reveals abnormal cervical cytology such as atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LGSIL), and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL), colposcopy and directed biopsy often are indicated. They help the physician rule out the presence of invasive carcinoma and determine the grade and distribution of the intraepithelial lesion. Currently, only HGSIL is considered premalignant and requires aggressive treatment via cone biopsy.1 Additional indications for the procedure are listed in Table 1.

Remove a single specimen that includes the entire transformation zone.

From a diagnostic standpoint, cone biopsy should be performed when the endocervical curettage is positive for dysplasia because it is difficult to grade the severity of dysplasia on the basis of the scant tissue fragments obtained by curettage. From a therapeutic standpoint, lesions that involve the endocervical canal are less likely to be adequately treated by destructive techniques such as cryotherapy. Thus, for most women, cone biopsy of the cervix is both diagnostic and therapeutic.

TABLE 1

Indications for cervical conization

|

Preparing for cone biopsy

Cone biopsy involves the surgical excision of a wedge-shaped portion of the ecto- and endocervix, including the removal of the entire squamocolumnar junction (SC junction) of the cervix, generally agreed to be the site of origin of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. The procedure may be performed using a scalpel, electroexcision (LEEP or fine-needle electrode), or CO2 laser. The choice between performing “cold-knife” versus “hot-knife” conization is largely one of personal preference and depends on surgical experience, the size/severity of the lesion, and the desires of the patient. In most cases, I prefer to use electrocautery because of its technical simplicity and the ability to operate with only a local anesthetic. It is particularly appropriate for patients with an obvious ectocervical lesion and in young, nulliparous women in whom I am trying to minimize the amount of healthy cervical tissue removed.

The use of colposcopy, either preoperatively or intraoperatively, allows precise evaluation of the amount of cervical tissue needed to be removed and reduces the incidence of positive margins. The geometry, i.e., width and depth, of the cone specimen will vary from patient to patient, depending on the size and location of the dysplastic lesion, as well as the location of the SC junction. Specifically, the width of the cone (ectocervical portion) is determined by the size of the transformation zone and size and location of any ectocervical lesions. The depth of the cone (endocervical portion) is determined by the location of the SC junction, the presence or absence of endocervi-cal disease, or the suspicion of a glandular lesion. When a discrete intraepithelial lesion has not been identified, it is critical to rule out a significant endocervical lesion. Therefore, the amount of tissue I plan to remove is based on the following 2 factors:

- Location of the SC junction. The more endocervical the SC junction is, the more likely the presence of a lesion higher in the canal. However, squamous intraepithelial lesions rarely extend higher than 2 cm into the canal.2

- Endocervical gland involvement. SIL frequently involves the endocervical glands, often to a depth of 5 mm or less. Several investigators have suggested that excision of endocervical glands to a depth of 7 to 10 mm produces acceptable cure rates.3

Based on these 2 principles, the endocer-vical portion of the cone should be 20 mm wide (10 mm on either side of the canal) and no more than 2 cm deep.

Technique

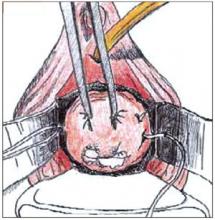

Traditionally, the first step in performing a cone biopsy is to place sutures lateral to the cervix to decrease bleeding (Figure 1). While many surgeons believe that these sutures have a beneficial effect on hemosta-sis, others have not found them to be necessary.4 And although cone biopsy typically is performed under regional or general anesthesia, I have found that IV sedation and injection of a local anesthetic are adequate for most cone biopsies.

Begin the procedure by placing either a posterior weighted speculum (for a cold-knife cone) or an insulated speculum (for electrocautery) into the vagina. Then inject a premixed solution of 2% xylocaine and epi-nephrine in a concentration of 1:200,000 into the cervical stroma at 12 o’clock outside the intended margin of the cone biopsy. Then grasp this tissue with a single-tooth tenacu-lum. Inject 5 to 10 cc of the solution para-cervically at 3 o’clock and again at 9 o’clock. I typically use a total of 20 to 30 cc to maintain hemostasis. Alternatively, the anesthetic can be infiltrated into the subepithelial stroma circumferentially around the ectocervix.

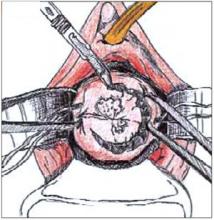

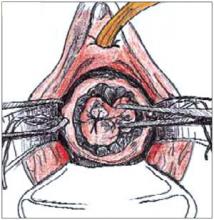

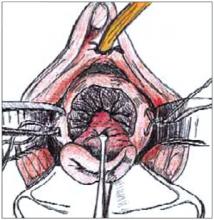

To perform a cold-knife cone, use a #11 surgical blade to begin a circular incision starting at 12 o’clock on the face of the cervix, angling the tip of the blade toward the endocervical canal (Figure 2). Use a uterine sound to mark a depth of 2 cm within the endo-cervical canal, typically the most cephalad margin of the cone. The goal is to remove a single specimen that includes the entire transformation zone and distal endocervical canal (Figure 3). After removing the cone, perform an endocervical curettage to collect an additional specimen. Apply light cautery to the edges of the cervical bed, as well as any bleeding points (Figure 4). Place 1 interrupted suture (I prefer 2-0 polyglactin) in each quadrant of the face of the cervix, starting from outside the margin of the cone and exiting near the cervical os. Then insert the suture near the cervical os and exit outside the margin of the cone. Tying these sut ures everts the cervical os to a degree and keeps the transformation zone closer to the external surface of the cervix, making it easier to find when performing future colposcopies.

Electroexcision with a fine-needle electrode is performed with a blend-1 waveform using 18 watts of power.5 Perform the excision using the “cut” button on the bovie handpiece and then use the leading edge of the electrical arc to incise the tissue. (It is best to use the arc, i.e., visible spark, to do the cutting rather than the tip of the instrument, which may “stick” to surrounding tissues.) Make a full circle to a depth of about 7 mm to outline the ectocervical cone margins. Then “pull down” the stroma on the edge of the specimen with a skin hook to continue the dissection parallel to the long axis of the endocervical canal to a depth of 1.5 to 2.0 cm. I excise the “base” of the cone with scissors to minimize any cautery effect at the endocervical margin. Achieve hemostasis by electrofulgurating the bleeding vessels using 30 to 40 watts of power in the coagulation mode. Monsel solution or paste then can be applied as needed. This technique is similar to CO2 laser conization, only it is easier to learn and quicker to perform.

FIGURE 1

Begin the cone biopsy by placing lateral sutures at the cervicovaginal junction to decrease bleeding.

FIGURE 2

Use a #11 surgical blade to make the circular incision, angling the tip of the blade toward the endocervical canal.

FIGURE 3

Grasp the specimen, including the entire transformation zone and distal endocervical canal, with an Allis clamp.

FIGURE 4

Complete the cone excision by cutting across endocervix. Apply light cautery to the edges of the cervical bed.

Follow-up

Postoperatively, patients should undergo cytologic screening every 4 months for 2 years to identify persistent or recurrent disease. Patients with positive cone biopsy margins face the highest risk of persistent or recurrent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Although there is considerable variation, studies generally have reported a 30% incidence of positive margins. The incidence of recurrent dysplasia when the margins are positive has been reported to be as high as 50%.6,7

In women with positive margins, colposcopy and cervical and endocervical cytology are an important part of the follow-up. I perform an endocervical curettage, in addition to a Pap smear, at each interval visit during the first year postoperatively and perform colposcopy at the 6- and 12- month visits. After 2 years of follow-up with normal results, cytologic screening should be performed annually, per routine care.

The author reports no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Koutsky LA, Holmes KK, Critchlow CW, et al. A cohort study of the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 in relation to the papillomavirus. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1272-1278.

2. Burke L. Evolution of therapeutic approaches to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Lower Genital Tract Disease. 1997;1:267-273.

3. Burke L, Covell L, Antonioli D. Carbon dioxide laser therapy of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: factors determining success rates. Lasers Surg Med. 1980;1:113-122.

4. Gilbert L, Saunders NJ, Stringer R, Sharp F. Haemostasis and cold knife biopsy: a prospective randomized trial comparing a suture versus nonsuture technique. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:640-643.

5. Ferenczy A. Electroconization of the cervix with a fine-needle electrode. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:152-159.

6. AbdulKarim F, Nunez C. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia after conization:a study of 522 consecutive cervical cones. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:77-81.

7. Lubicz S, Ezekwche C, Allen A, Schiffer M. Significance of cone biopsy margins in the management of patients with cervical neoplasia. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:178-184.

- Cone biopsy typically includes the removal of the entire squamocolumnar junction of the cervix, generally agreed to be the site of origin of squamous cell carcinoma.

- Inject a premixed solution of 2% xylocaine and epinephrine in a concentration of 1:200,000 into the cervical stroma at 12 o’clock outside the intended margin.

- For a “cold-knife” cone, use a #11 surgical blade to begin a circular incision starting at 12 o’clock on the face of the cervix.

Cone biopsy of the cervix has been used for more than a century to rule out the presence of invasive carcinoma in women with squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL). And while less invasive techniques such as colposcopy and loop electrosurgical excision procedures (LEEP) have reduced the need for diagnostic conization dramatically, cervical cone biopsy becomes necessary when these techniques prove inadequate.

Indications

When routine screening reveals abnormal cervical cytology such as atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LGSIL), and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL), colposcopy and directed biopsy often are indicated. They help the physician rule out the presence of invasive carcinoma and determine the grade and distribution of the intraepithelial lesion. Currently, only HGSIL is considered premalignant and requires aggressive treatment via cone biopsy.1 Additional indications for the procedure are listed in Table 1.

Remove a single specimen that includes the entire transformation zone.

From a diagnostic standpoint, cone biopsy should be performed when the endocervical curettage is positive for dysplasia because it is difficult to grade the severity of dysplasia on the basis of the scant tissue fragments obtained by curettage. From a therapeutic standpoint, lesions that involve the endocervical canal are less likely to be adequately treated by destructive techniques such as cryotherapy. Thus, for most women, cone biopsy of the cervix is both diagnostic and therapeutic.

TABLE 1

Indications for cervical conization

|

Preparing for cone biopsy

Cone biopsy involves the surgical excision of a wedge-shaped portion of the ecto- and endocervix, including the removal of the entire squamocolumnar junction (SC junction) of the cervix, generally agreed to be the site of origin of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. The procedure may be performed using a scalpel, electroexcision (LEEP or fine-needle electrode), or CO2 laser. The choice between performing “cold-knife” versus “hot-knife” conization is largely one of personal preference and depends on surgical experience, the size/severity of the lesion, and the desires of the patient. In most cases, I prefer to use electrocautery because of its technical simplicity and the ability to operate with only a local anesthetic. It is particularly appropriate for patients with an obvious ectocervical lesion and in young, nulliparous women in whom I am trying to minimize the amount of healthy cervical tissue removed.

The use of colposcopy, either preoperatively or intraoperatively, allows precise evaluation of the amount of cervical tissue needed to be removed and reduces the incidence of positive margins. The geometry, i.e., width and depth, of the cone specimen will vary from patient to patient, depending on the size and location of the dysplastic lesion, as well as the location of the SC junction. Specifically, the width of the cone (ectocervical portion) is determined by the size of the transformation zone and size and location of any ectocervical lesions. The depth of the cone (endocervical portion) is determined by the location of the SC junction, the presence or absence of endocervi-cal disease, or the suspicion of a glandular lesion. When a discrete intraepithelial lesion has not been identified, it is critical to rule out a significant endocervical lesion. Therefore, the amount of tissue I plan to remove is based on the following 2 factors:

- Location of the SC junction. The more endocervical the SC junction is, the more likely the presence of a lesion higher in the canal. However, squamous intraepithelial lesions rarely extend higher than 2 cm into the canal.2

- Endocervical gland involvement. SIL frequently involves the endocervical glands, often to a depth of 5 mm or less. Several investigators have suggested that excision of endocervical glands to a depth of 7 to 10 mm produces acceptable cure rates.3

Based on these 2 principles, the endocer-vical portion of the cone should be 20 mm wide (10 mm on either side of the canal) and no more than 2 cm deep.

Technique

Traditionally, the first step in performing a cone biopsy is to place sutures lateral to the cervix to decrease bleeding (Figure 1). While many surgeons believe that these sutures have a beneficial effect on hemosta-sis, others have not found them to be necessary.4 And although cone biopsy typically is performed under regional or general anesthesia, I have found that IV sedation and injection of a local anesthetic are adequate for most cone biopsies.

Begin the procedure by placing either a posterior weighted speculum (for a cold-knife cone) or an insulated speculum (for electrocautery) into the vagina. Then inject a premixed solution of 2% xylocaine and epi-nephrine in a concentration of 1:200,000 into the cervical stroma at 12 o’clock outside the intended margin of the cone biopsy. Then grasp this tissue with a single-tooth tenacu-lum. Inject 5 to 10 cc of the solution para-cervically at 3 o’clock and again at 9 o’clock. I typically use a total of 20 to 30 cc to maintain hemostasis. Alternatively, the anesthetic can be infiltrated into the subepithelial stroma circumferentially around the ectocervix.

To perform a cold-knife cone, use a #11 surgical blade to begin a circular incision starting at 12 o’clock on the face of the cervix, angling the tip of the blade toward the endocervical canal (Figure 2). Use a uterine sound to mark a depth of 2 cm within the endo-cervical canal, typically the most cephalad margin of the cone. The goal is to remove a single specimen that includes the entire transformation zone and distal endocervical canal (Figure 3). After removing the cone, perform an endocervical curettage to collect an additional specimen. Apply light cautery to the edges of the cervical bed, as well as any bleeding points (Figure 4). Place 1 interrupted suture (I prefer 2-0 polyglactin) in each quadrant of the face of the cervix, starting from outside the margin of the cone and exiting near the cervical os. Then insert the suture near the cervical os and exit outside the margin of the cone. Tying these sut ures everts the cervical os to a degree and keeps the transformation zone closer to the external surface of the cervix, making it easier to find when performing future colposcopies.

Electroexcision with a fine-needle electrode is performed with a blend-1 waveform using 18 watts of power.5 Perform the excision using the “cut” button on the bovie handpiece and then use the leading edge of the electrical arc to incise the tissue. (It is best to use the arc, i.e., visible spark, to do the cutting rather than the tip of the instrument, which may “stick” to surrounding tissues.) Make a full circle to a depth of about 7 mm to outline the ectocervical cone margins. Then “pull down” the stroma on the edge of the specimen with a skin hook to continue the dissection parallel to the long axis of the endocervical canal to a depth of 1.5 to 2.0 cm. I excise the “base” of the cone with scissors to minimize any cautery effect at the endocervical margin. Achieve hemostasis by electrofulgurating the bleeding vessels using 30 to 40 watts of power in the coagulation mode. Monsel solution or paste then can be applied as needed. This technique is similar to CO2 laser conization, only it is easier to learn and quicker to perform.

FIGURE 1

Begin the cone biopsy by placing lateral sutures at the cervicovaginal junction to decrease bleeding.

FIGURE 2

Use a #11 surgical blade to make the circular incision, angling the tip of the blade toward the endocervical canal.

FIGURE 3

Grasp the specimen, including the entire transformation zone and distal endocervical canal, with an Allis clamp.

FIGURE 4

Complete the cone excision by cutting across endocervix. Apply light cautery to the edges of the cervical bed.

Follow-up

Postoperatively, patients should undergo cytologic screening every 4 months for 2 years to identify persistent or recurrent disease. Patients with positive cone biopsy margins face the highest risk of persistent or recurrent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Although there is considerable variation, studies generally have reported a 30% incidence of positive margins. The incidence of recurrent dysplasia when the margins are positive has been reported to be as high as 50%.6,7

In women with positive margins, colposcopy and cervical and endocervical cytology are an important part of the follow-up. I perform an endocervical curettage, in addition to a Pap smear, at each interval visit during the first year postoperatively and perform colposcopy at the 6- and 12- month visits. After 2 years of follow-up with normal results, cytologic screening should be performed annually, per routine care.

The author reports no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

- Cone biopsy typically includes the removal of the entire squamocolumnar junction of the cervix, generally agreed to be the site of origin of squamous cell carcinoma.

- Inject a premixed solution of 2% xylocaine and epinephrine in a concentration of 1:200,000 into the cervical stroma at 12 o’clock outside the intended margin.

- For a “cold-knife” cone, use a #11 surgical blade to begin a circular incision starting at 12 o’clock on the face of the cervix.

Cone biopsy of the cervix has been used for more than a century to rule out the presence of invasive carcinoma in women with squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL). And while less invasive techniques such as colposcopy and loop electrosurgical excision procedures (LEEP) have reduced the need for diagnostic conization dramatically, cervical cone biopsy becomes necessary when these techniques prove inadequate.

Indications

When routine screening reveals abnormal cervical cytology such as atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LGSIL), and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL), colposcopy and directed biopsy often are indicated. They help the physician rule out the presence of invasive carcinoma and determine the grade and distribution of the intraepithelial lesion. Currently, only HGSIL is considered premalignant and requires aggressive treatment via cone biopsy.1 Additional indications for the procedure are listed in Table 1.

Remove a single specimen that includes the entire transformation zone.

From a diagnostic standpoint, cone biopsy should be performed when the endocervical curettage is positive for dysplasia because it is difficult to grade the severity of dysplasia on the basis of the scant tissue fragments obtained by curettage. From a therapeutic standpoint, lesions that involve the endocervical canal are less likely to be adequately treated by destructive techniques such as cryotherapy. Thus, for most women, cone biopsy of the cervix is both diagnostic and therapeutic.

TABLE 1

Indications for cervical conization

|

Preparing for cone biopsy

Cone biopsy involves the surgical excision of a wedge-shaped portion of the ecto- and endocervix, including the removal of the entire squamocolumnar junction (SC junction) of the cervix, generally agreed to be the site of origin of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. The procedure may be performed using a scalpel, electroexcision (LEEP or fine-needle electrode), or CO2 laser. The choice between performing “cold-knife” versus “hot-knife” conization is largely one of personal preference and depends on surgical experience, the size/severity of the lesion, and the desires of the patient. In most cases, I prefer to use electrocautery because of its technical simplicity and the ability to operate with only a local anesthetic. It is particularly appropriate for patients with an obvious ectocervical lesion and in young, nulliparous women in whom I am trying to minimize the amount of healthy cervical tissue removed.

The use of colposcopy, either preoperatively or intraoperatively, allows precise evaluation of the amount of cervical tissue needed to be removed and reduces the incidence of positive margins. The geometry, i.e., width and depth, of the cone specimen will vary from patient to patient, depending on the size and location of the dysplastic lesion, as well as the location of the SC junction. Specifically, the width of the cone (ectocervical portion) is determined by the size of the transformation zone and size and location of any ectocervical lesions. The depth of the cone (endocervical portion) is determined by the location of the SC junction, the presence or absence of endocervi-cal disease, or the suspicion of a glandular lesion. When a discrete intraepithelial lesion has not been identified, it is critical to rule out a significant endocervical lesion. Therefore, the amount of tissue I plan to remove is based on the following 2 factors:

- Location of the SC junction. The more endocervical the SC junction is, the more likely the presence of a lesion higher in the canal. However, squamous intraepithelial lesions rarely extend higher than 2 cm into the canal.2

- Endocervical gland involvement. SIL frequently involves the endocervical glands, often to a depth of 5 mm or less. Several investigators have suggested that excision of endocervical glands to a depth of 7 to 10 mm produces acceptable cure rates.3

Based on these 2 principles, the endocer-vical portion of the cone should be 20 mm wide (10 mm on either side of the canal) and no more than 2 cm deep.

Technique

Traditionally, the first step in performing a cone biopsy is to place sutures lateral to the cervix to decrease bleeding (Figure 1). While many surgeons believe that these sutures have a beneficial effect on hemosta-sis, others have not found them to be necessary.4 And although cone biopsy typically is performed under regional or general anesthesia, I have found that IV sedation and injection of a local anesthetic are adequate for most cone biopsies.

Begin the procedure by placing either a posterior weighted speculum (for a cold-knife cone) or an insulated speculum (for electrocautery) into the vagina. Then inject a premixed solution of 2% xylocaine and epi-nephrine in a concentration of 1:200,000 into the cervical stroma at 12 o’clock outside the intended margin of the cone biopsy. Then grasp this tissue with a single-tooth tenacu-lum. Inject 5 to 10 cc of the solution para-cervically at 3 o’clock and again at 9 o’clock. I typically use a total of 20 to 30 cc to maintain hemostasis. Alternatively, the anesthetic can be infiltrated into the subepithelial stroma circumferentially around the ectocervix.

To perform a cold-knife cone, use a #11 surgical blade to begin a circular incision starting at 12 o’clock on the face of the cervix, angling the tip of the blade toward the endocervical canal (Figure 2). Use a uterine sound to mark a depth of 2 cm within the endo-cervical canal, typically the most cephalad margin of the cone. The goal is to remove a single specimen that includes the entire transformation zone and distal endocervical canal (Figure 3). After removing the cone, perform an endocervical curettage to collect an additional specimen. Apply light cautery to the edges of the cervical bed, as well as any bleeding points (Figure 4). Place 1 interrupted suture (I prefer 2-0 polyglactin) in each quadrant of the face of the cervix, starting from outside the margin of the cone and exiting near the cervical os. Then insert the suture near the cervical os and exit outside the margin of the cone. Tying these sut ures everts the cervical os to a degree and keeps the transformation zone closer to the external surface of the cervix, making it easier to find when performing future colposcopies.

Electroexcision with a fine-needle electrode is performed with a blend-1 waveform using 18 watts of power.5 Perform the excision using the “cut” button on the bovie handpiece and then use the leading edge of the electrical arc to incise the tissue. (It is best to use the arc, i.e., visible spark, to do the cutting rather than the tip of the instrument, which may “stick” to surrounding tissues.) Make a full circle to a depth of about 7 mm to outline the ectocervical cone margins. Then “pull down” the stroma on the edge of the specimen with a skin hook to continue the dissection parallel to the long axis of the endocervical canal to a depth of 1.5 to 2.0 cm. I excise the “base” of the cone with scissors to minimize any cautery effect at the endocervical margin. Achieve hemostasis by electrofulgurating the bleeding vessels using 30 to 40 watts of power in the coagulation mode. Monsel solution or paste then can be applied as needed. This technique is similar to CO2 laser conization, only it is easier to learn and quicker to perform.

FIGURE 1

Begin the cone biopsy by placing lateral sutures at the cervicovaginal junction to decrease bleeding.

FIGURE 2

Use a #11 surgical blade to make the circular incision, angling the tip of the blade toward the endocervical canal.

FIGURE 3

Grasp the specimen, including the entire transformation zone and distal endocervical canal, with an Allis clamp.

FIGURE 4

Complete the cone excision by cutting across endocervix. Apply light cautery to the edges of the cervical bed.

Follow-up

Postoperatively, patients should undergo cytologic screening every 4 months for 2 years to identify persistent or recurrent disease. Patients with positive cone biopsy margins face the highest risk of persistent or recurrent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Although there is considerable variation, studies generally have reported a 30% incidence of positive margins. The incidence of recurrent dysplasia when the margins are positive has been reported to be as high as 50%.6,7

In women with positive margins, colposcopy and cervical and endocervical cytology are an important part of the follow-up. I perform an endocervical curettage, in addition to a Pap smear, at each interval visit during the first year postoperatively and perform colposcopy at the 6- and 12- month visits. After 2 years of follow-up with normal results, cytologic screening should be performed annually, per routine care.

The author reports no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Koutsky LA, Holmes KK, Critchlow CW, et al. A cohort study of the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 in relation to the papillomavirus. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1272-1278.

2. Burke L. Evolution of therapeutic approaches to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Lower Genital Tract Disease. 1997;1:267-273.

3. Burke L, Covell L, Antonioli D. Carbon dioxide laser therapy of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: factors determining success rates. Lasers Surg Med. 1980;1:113-122.

4. Gilbert L, Saunders NJ, Stringer R, Sharp F. Haemostasis and cold knife biopsy: a prospective randomized trial comparing a suture versus nonsuture technique. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:640-643.

5. Ferenczy A. Electroconization of the cervix with a fine-needle electrode. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:152-159.

6. AbdulKarim F, Nunez C. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia after conization:a study of 522 consecutive cervical cones. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:77-81.

7. Lubicz S, Ezekwche C, Allen A, Schiffer M. Significance of cone biopsy margins in the management of patients with cervical neoplasia. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:178-184.

1. Koutsky LA, Holmes KK, Critchlow CW, et al. A cohort study of the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 in relation to the papillomavirus. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1272-1278.

2. Burke L. Evolution of therapeutic approaches to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Lower Genital Tract Disease. 1997;1:267-273.

3. Burke L, Covell L, Antonioli D. Carbon dioxide laser therapy of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: factors determining success rates. Lasers Surg Med. 1980;1:113-122.

4. Gilbert L, Saunders NJ, Stringer R, Sharp F. Haemostasis and cold knife biopsy: a prospective randomized trial comparing a suture versus nonsuture technique. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:640-643.

5. Ferenczy A. Electroconization of the cervix with a fine-needle electrode. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:152-159.

6. AbdulKarim F, Nunez C. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia after conization:a study of 522 consecutive cervical cones. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:77-81.

7. Lubicz S, Ezekwche C, Allen A, Schiffer M. Significance of cone biopsy margins in the management of patients with cervical neoplasia. J Reprod Med. 1984;29:178-184.