User login

Everything We Say and Do: Discussing advance care planning

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experiences of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I empower all of my patients by giving them the opportunity to consider advance care planning.

Why I do it

Everyone deserves advance care planning, and every health care encounter, including a hospitalization, is an opportunity to better identify and document patients’ wishes for care should they become unable to express them. If we wait for patients to develop serious advanced illness before having advance care planning conversations, we risk depriving them of the care they would want in these situations. Additionally, we place a huge burden on family members who may struggle with excruciatingly difficult decisions in the absence of guidance about their loved one’s wishes.

How I do it

I start by identifying which components of advance care planning each patient needs, using a simple algorithm (see figure). All of my patients are queried about code status, and I give them the opportunity to better understand the value of having a healthcare proxy and advance directives, if they are not already in place.

For the remainder of this column, I’m going to focus on patients who have an acute and/or chronic treatable illness – those who require simpler advance-care-planning conversations.

To comfortably initiate the conversation about advance care planning, I always start by asking permission. I commonly say, “There are a couple of important items I discuss with all of my patients to make sure they get the care they want. Would it be okay for us to talk about those now?” This respectfully puts the patient in control. I then initiate a discussion of code status by saying, “It’s important that all of us on your care team know what you would like us to do if you got so sick that we couldn’t communicate with you. I’m not expecting this to happen, but I ask all my patients this question so that we have your instructions.” From there, the conversation evolves depending on whether the patient has any familiarity with this question and its implications.

To introduce the concept of a health care proxy and advance directives, I ask, “Have you ever thought about who you might choose to make medical decisions on your behalf if you became too sick to make those decisions yourself?” Then, finally, I share the following information, usually referring to the blank advance directives document they received in their admission packet: “There is a valuable way to put your wishes about specific care options in writing so others will know your wishes if you’re unable to communicate with them. Would you like to talk about that right now?” Again, this gives the patient control of the situation and an opportunity to decline the conversation if they are not interested or comfortable at that time.

It’s important to document the nature and outcome of these conversations. Keep in mind, advance care planning discussions need not occur at the time of admission. In fact, admission may be the worst time for some patients, further underscoring the importance of documentation so that subsequent providers can see whether advance care planning has been addressed during the hospital stay.

Note: For useful educational resources that address goals-of-care conversations in patients toward the end of life, the Center to Advance Palliative Care (www.capc.org) has a number of educational courses that address these important communication skills.

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash. and chair of the SHM Patient Experience Committee .

Reference

1. Moss, A.H., Ganjoo, J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3(5):1379-84. doi:10.2215/CJN.00940208.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experiences of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I empower all of my patients by giving them the opportunity to consider advance care planning.

Why I do it

Everyone deserves advance care planning, and every health care encounter, including a hospitalization, is an opportunity to better identify and document patients’ wishes for care should they become unable to express them. If we wait for patients to develop serious advanced illness before having advance care planning conversations, we risk depriving them of the care they would want in these situations. Additionally, we place a huge burden on family members who may struggle with excruciatingly difficult decisions in the absence of guidance about their loved one’s wishes.

How I do it

I start by identifying which components of advance care planning each patient needs, using a simple algorithm (see figure). All of my patients are queried about code status, and I give them the opportunity to better understand the value of having a healthcare proxy and advance directives, if they are not already in place.

For the remainder of this column, I’m going to focus on patients who have an acute and/or chronic treatable illness – those who require simpler advance-care-planning conversations.

To comfortably initiate the conversation about advance care planning, I always start by asking permission. I commonly say, “There are a couple of important items I discuss with all of my patients to make sure they get the care they want. Would it be okay for us to talk about those now?” This respectfully puts the patient in control. I then initiate a discussion of code status by saying, “It’s important that all of us on your care team know what you would like us to do if you got so sick that we couldn’t communicate with you. I’m not expecting this to happen, but I ask all my patients this question so that we have your instructions.” From there, the conversation evolves depending on whether the patient has any familiarity with this question and its implications.

To introduce the concept of a health care proxy and advance directives, I ask, “Have you ever thought about who you might choose to make medical decisions on your behalf if you became too sick to make those decisions yourself?” Then, finally, I share the following information, usually referring to the blank advance directives document they received in their admission packet: “There is a valuable way to put your wishes about specific care options in writing so others will know your wishes if you’re unable to communicate with them. Would you like to talk about that right now?” Again, this gives the patient control of the situation and an opportunity to decline the conversation if they are not interested or comfortable at that time.

It’s important to document the nature and outcome of these conversations. Keep in mind, advance care planning discussions need not occur at the time of admission. In fact, admission may be the worst time for some patients, further underscoring the importance of documentation so that subsequent providers can see whether advance care planning has been addressed during the hospital stay.

Note: For useful educational resources that address goals-of-care conversations in patients toward the end of life, the Center to Advance Palliative Care (www.capc.org) has a number of educational courses that address these important communication skills.

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash. and chair of the SHM Patient Experience Committee .

Reference

1. Moss, A.H., Ganjoo, J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3(5):1379-84. doi:10.2215/CJN.00940208.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experiences of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I empower all of my patients by giving them the opportunity to consider advance care planning.

Why I do it

Everyone deserves advance care planning, and every health care encounter, including a hospitalization, is an opportunity to better identify and document patients’ wishes for care should they become unable to express them. If we wait for patients to develop serious advanced illness before having advance care planning conversations, we risk depriving them of the care they would want in these situations. Additionally, we place a huge burden on family members who may struggle with excruciatingly difficult decisions in the absence of guidance about their loved one’s wishes.

How I do it

I start by identifying which components of advance care planning each patient needs, using a simple algorithm (see figure). All of my patients are queried about code status, and I give them the opportunity to better understand the value of having a healthcare proxy and advance directives, if they are not already in place.

For the remainder of this column, I’m going to focus on patients who have an acute and/or chronic treatable illness – those who require simpler advance-care-planning conversations.

To comfortably initiate the conversation about advance care planning, I always start by asking permission. I commonly say, “There are a couple of important items I discuss with all of my patients to make sure they get the care they want. Would it be okay for us to talk about those now?” This respectfully puts the patient in control. I then initiate a discussion of code status by saying, “It’s important that all of us on your care team know what you would like us to do if you got so sick that we couldn’t communicate with you. I’m not expecting this to happen, but I ask all my patients this question so that we have your instructions.” From there, the conversation evolves depending on whether the patient has any familiarity with this question and its implications.

To introduce the concept of a health care proxy and advance directives, I ask, “Have you ever thought about who you might choose to make medical decisions on your behalf if you became too sick to make those decisions yourself?” Then, finally, I share the following information, usually referring to the blank advance directives document they received in their admission packet: “There is a valuable way to put your wishes about specific care options in writing so others will know your wishes if you’re unable to communicate with them. Would you like to talk about that right now?” Again, this gives the patient control of the situation and an opportunity to decline the conversation if they are not interested or comfortable at that time.

It’s important to document the nature and outcome of these conversations. Keep in mind, advance care planning discussions need not occur at the time of admission. In fact, admission may be the worst time for some patients, further underscoring the importance of documentation so that subsequent providers can see whether advance care planning has been addressed during the hospital stay.

Note: For useful educational resources that address goals-of-care conversations in patients toward the end of life, the Center to Advance Palliative Care (www.capc.org) has a number of educational courses that address these important communication skills.

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash. and chair of the SHM Patient Experience Committee .

Reference

1. Moss, A.H., Ganjoo, J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3(5):1379-84. doi:10.2215/CJN.00940208.

Defining Patient Experience: 'Everything We Say and Do'

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one ormore of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “Everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings and well-being.”

As providers, how do we define the patient experience? Over the past year, I have had the pleasure of working with a dedicated group of 15 fellow members on the newly formed SHM Patient Experience Committee. One of our first goals was to define the patient experience in a way that acknowledges our role and its potential impact on patients as emotional beings and not just vessels for their disease.

To this end, we define the patient experience as “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.

Although it’s true that patients bring with them their own history and narrative that contribute to their experience, we cannot change that. We can only adjust our own behaviors and actions when we seek to elicit or respond to patients’ concerns and goals.

And although “everything we say and do” is inclusive of providing the most effective and evidence-based medical care at all times, we believe that accurate clinical decision making absolutely must be accompanied by superior communication. By offering clear explanations, listening compassionately, and acknowledging patients’ predicaments with empathy and caring statements, we can restore a degree of humanity to our care that will allow patients to trust that we have their best interests in mind at all times. This is our role in improving the patient experience.

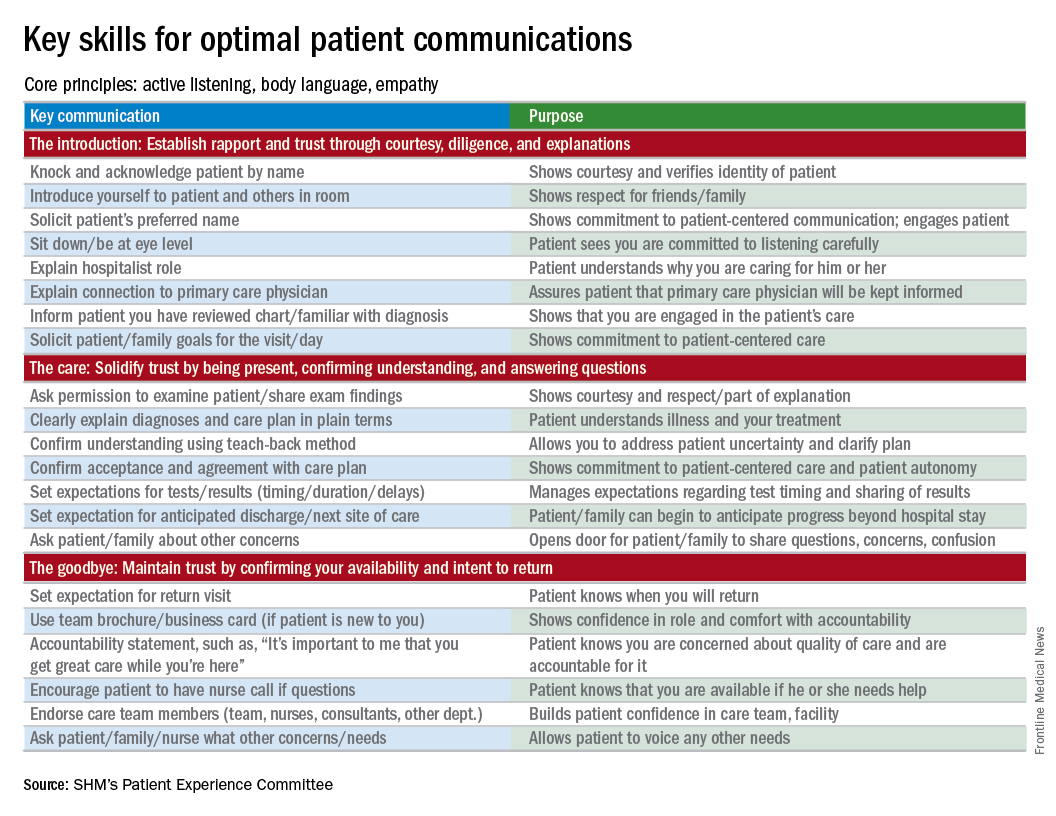

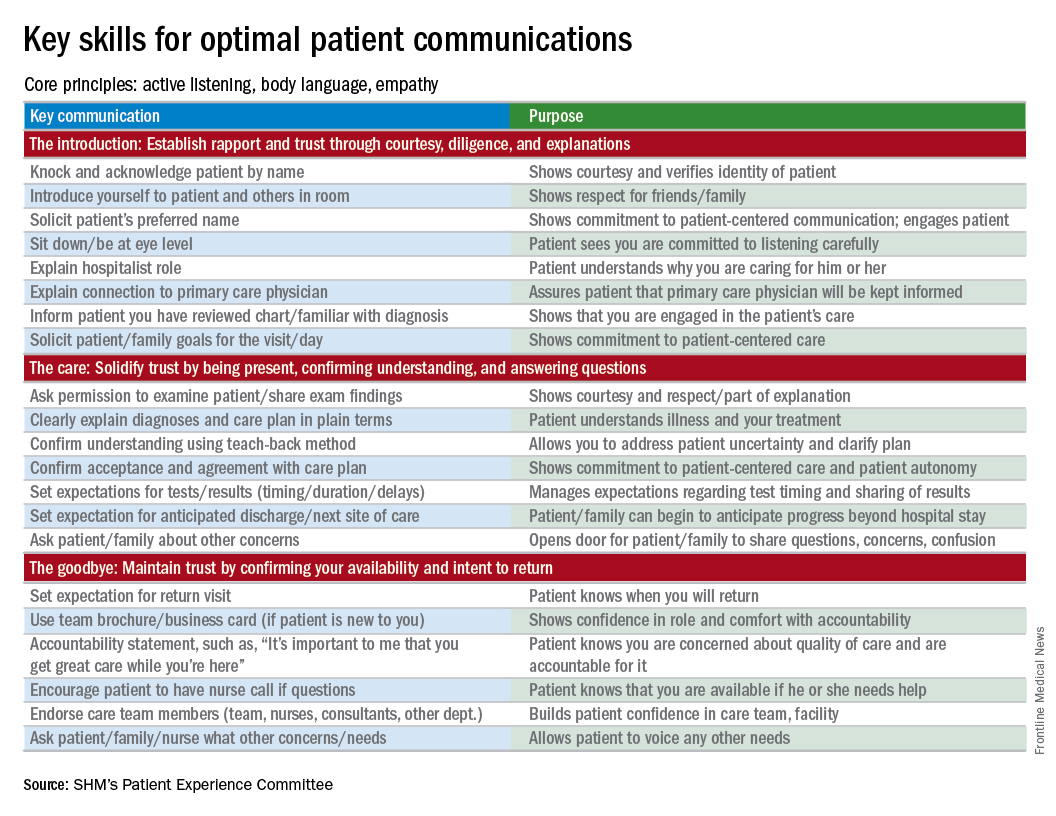

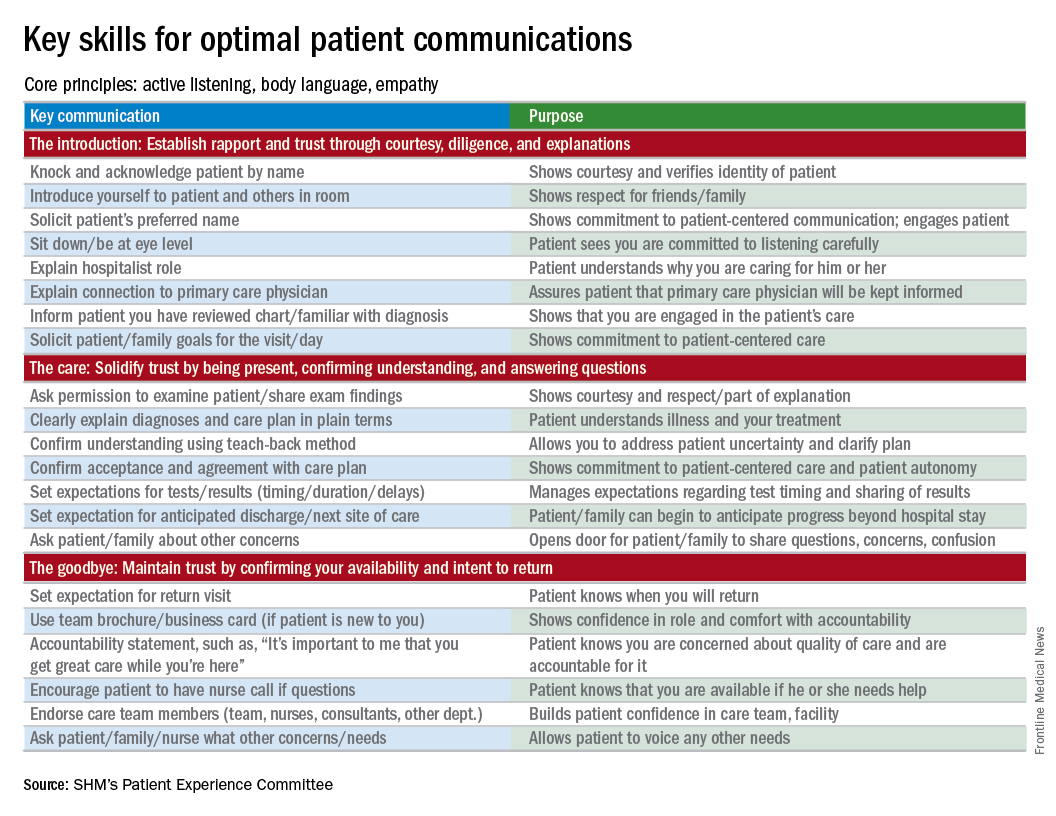

Beginning next month, members of the Patient Experience Committee will be sharing key communication skills and interventions that each of us believes to be important and effective. Each member will share what they do, why they do it, and how it can be done effectively. The items we’ll be focusing on will be taken from the “Core Principles” and “Key Communications,” as compiled by the committee (see Table 1, below). Some have evidence to back them up. Some are common sense. All of them are simply the right thing to do.

We hope you’ll reflect on “everything we say and do” each month as well as share it with your colleagues and teams. And we need look no further for a winning argument to focus on the patient experience than Sir William Osler and one of his most famous quotes: “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.”

We’re going for great. Are you with us? TH

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Tacoma, Wash.–based Sound Physicians. He is chair of SHM’s Patient Experience Committee.

Table 1.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one ormore of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “Everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings and well-being.”

As providers, how do we define the patient experience? Over the past year, I have had the pleasure of working with a dedicated group of 15 fellow members on the newly formed SHM Patient Experience Committee. One of our first goals was to define the patient experience in a way that acknowledges our role and its potential impact on patients as emotional beings and not just vessels for their disease.

To this end, we define the patient experience as “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.

Although it’s true that patients bring with them their own history and narrative that contribute to their experience, we cannot change that. We can only adjust our own behaviors and actions when we seek to elicit or respond to patients’ concerns and goals.

And although “everything we say and do” is inclusive of providing the most effective and evidence-based medical care at all times, we believe that accurate clinical decision making absolutely must be accompanied by superior communication. By offering clear explanations, listening compassionately, and acknowledging patients’ predicaments with empathy and caring statements, we can restore a degree of humanity to our care that will allow patients to trust that we have their best interests in mind at all times. This is our role in improving the patient experience.

Beginning next month, members of the Patient Experience Committee will be sharing key communication skills and interventions that each of us believes to be important and effective. Each member will share what they do, why they do it, and how it can be done effectively. The items we’ll be focusing on will be taken from the “Core Principles” and “Key Communications,” as compiled by the committee (see Table 1, below). Some have evidence to back them up. Some are common sense. All of them are simply the right thing to do.

We hope you’ll reflect on “everything we say and do” each month as well as share it with your colleagues and teams. And we need look no further for a winning argument to focus on the patient experience than Sir William Osler and one of his most famous quotes: “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.”

We’re going for great. Are you with us? TH

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Tacoma, Wash.–based Sound Physicians. He is chair of SHM’s Patient Experience Committee.

Table 1.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one ormore of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “Everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings and well-being.”

As providers, how do we define the patient experience? Over the past year, I have had the pleasure of working with a dedicated group of 15 fellow members on the newly formed SHM Patient Experience Committee. One of our first goals was to define the patient experience in a way that acknowledges our role and its potential impact on patients as emotional beings and not just vessels for their disease.

To this end, we define the patient experience as “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.

Although it’s true that patients bring with them their own history and narrative that contribute to their experience, we cannot change that. We can only adjust our own behaviors and actions when we seek to elicit or respond to patients’ concerns and goals.

And although “everything we say and do” is inclusive of providing the most effective and evidence-based medical care at all times, we believe that accurate clinical decision making absolutely must be accompanied by superior communication. By offering clear explanations, listening compassionately, and acknowledging patients’ predicaments with empathy and caring statements, we can restore a degree of humanity to our care that will allow patients to trust that we have their best interests in mind at all times. This is our role in improving the patient experience.

Beginning next month, members of the Patient Experience Committee will be sharing key communication skills and interventions that each of us believes to be important and effective. Each member will share what they do, why they do it, and how it can be done effectively. The items we’ll be focusing on will be taken from the “Core Principles” and “Key Communications,” as compiled by the committee (see Table 1, below). Some have evidence to back them up. Some are common sense. All of them are simply the right thing to do.

We hope you’ll reflect on “everything we say and do” each month as well as share it with your colleagues and teams. And we need look no further for a winning argument to focus on the patient experience than Sir William Osler and one of his most famous quotes: “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.”

We’re going for great. Are you with us? TH

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Tacoma, Wash.–based Sound Physicians. He is chair of SHM’s Patient Experience Committee.

Table 1.