User login

Impact of Psychotropic Medication Reviews on Prescribing Patterns

Due to the ever-expanding pool of psychopharmacologic agents available to treat mental health conditions, prescribers need to be vigilant about ensuring appropriate medication selection, evaluation, and monitoring. In response to this need, the Office of Mental Health Operations, Mental Health Services, and Pharmacy Benefits Management Services launched the Psychotropic Drug Safety Initiative (PDSI) to improve evidence-based psychotropic prescribing habits within the VA. Considering the large geriatric population in the VA, PDSI was particularly concerned with benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications.

Background

The management of neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) for dementia is particularly burdensome to patients, caregivers, and prescribers. When nonpharmacologic interventions fail, patients are often prescribed antipsychotic medications to target these symptoms. The FDA has issued a black box warning regarding an increased risk of death associated with the use of both first- and second-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis.1 Due to these risks, tapering or discontinuing these medications should be considered at regular intervals.

Recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded its goal to reduce antipsychotic use in nursing facilities by 25% by the end of 2015 and 30% by the end of 2016.2 A review investigated the impact of withdrawal vs continuation of antipsychotic medications in the setting of Alzheimer dementia (AD) and found that antipsychotic medications could be withdrawn without detrimental effects on patient behaviors.3 However, the study also noted that those patients with severe NPS at baseline or who had a history of positive response to an antipsychotic might be at increased risk of relapse or have a shorter time to relapse when antipsychotic medications are withdrawn.

Benzodiazepines as a class may be used for many indications, including anxiety disorders, seizure disorders, sleep disorders, or muscle spasms. However, due to known risks of cognitive impairments, sedation, falls, or dependence and addiction, these agents are typically recommended for only short-term treatment. These risks are potentially amplified in a geriatric population, because elderly patients have an increased sensitivity to the effects of these agents and may have impaired hepatic or renal function, leading to accumulation.

Due to these risks, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) recommends against the use of any benzodiazepines for the treatment of insomnia, agitation, or delirium. Additionally, the AGS recommends that use of these agents for the treatment of behavioral problems related to dementia be reserved for those who have failed nonpharmacologic options and are at risk to themselves or others.4

Growing evidence suggests that benzodiazepine use may increase the risk of developing AD. A recent casecontrol study compare records of 1,796 patients with an AD diagnosis to 7,184 patients with no cognitive deficits. This study found that patients with a history of benzodiazepine use had a 51% increase in risk for AD. Additionally, use of long-acting benzodiazepines, such as diazepam and clonazepam, was strongly associated with the development of AD.5 These data further illustrate the importance of minimizing the use of benzodiazepines.

To ensure proper use of these 2 classes of medications, clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs) at the Lexington VAMC (LVAMC) in Kentucky began conducting psychotropic medication reviews (PMRs). Each PMR contained a brief summary of evidence-based recommendations (both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) and a clinical review of the patient’s medication history, including an evaluation of the appropriateness of current therapy and supportive documentation. Patients were candidates for PMR if they met one of the following criteria: (1) use of a benzodiazepine in a patient with dementia; (2) use of a benzodiazepine in a patient aged > 75 years; and (3) use of an antipsychotic in a patient with dementia. These criteria were selected based on guidance set forth by the PDSI. The figure provides a sample of the PMR template in the electronic medical record (EMR).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of a pharmacist-conducted PMR based on prescriber response to written recommendations. Additionally, this study characterized any observed differences in prescriber response based on discipline. The results of this study will be used to evaluate the efficacy of LVAMC’s current method of clinical pharmacy intervention and identify areas for process improvement. This study was reviewed and approved by the LVAMC institutional review board and research and development committee.

Methods

Patients were included in this study if they had a PMR note entered in the EMR between September 2014 and January 2015. Baseline demographic information collected included patient age and gender. One study author manually reviewed all PMR notes and collected the type of pharmacy intervention (characterized as recommendation for medication adjustment, patient education, both medication adjustment and patient education, or no recommendation), provider discipline, provider response to intervention, and any changes to medication therapy that occurred as a result of pharmacist intervention.

When patients were not cognitively able to receive education, family members or caretakers were educated. The primary outcome of this study was prescriber response to pharmacist recommendations, which was characterized as acknowledged, ignored, accepted, or declined with justification. In instances where both medication adjustment and patient education was recommended, the recommendation was considered to be accepted only if both components of the recommendation were addressed. The secondary outcome sought to identify any difference in provider response based on discipline.

Results

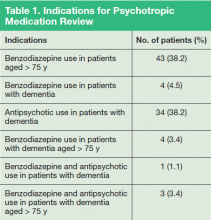

Eighty-nine patients were included in the study. Due to the nature of LVAMC, the patient population was fairly homogeneous, with an average patient age of 80 years (range 52-95 years); > 97% of patients were male. Fifty patients were noted to have prescriptions for benzodiazepines and were aged > 75 years, 11 patients had prescriptions for benzodiazepines and a diagnosis of dementia, and 38 patients had prescriptions for antipsychotics and a diagnosis of dementia. Several patients fell into more than one of the categories (Table 1).

Specific written recommendations were made for 69 (78%) patients, with 20 patients having appropriate documentation in the chart for therapy continuation. The most common documented reasons for continuation of therapy were (a) patient/caregiver educated and consent to continue therapy already documented; (b) recent dose reduction or discontinuation attempt failed; (c) recent successful dose reduction; or (d) documented risk to patient or others if medication were to be discontinued.

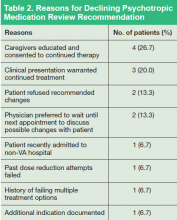

Most recommendations were for medication adjustments (n = 54; 78.3%). Six (8.7%) recommendations were for patient education only, and 9 (13%) recommendations were for both medication adjustment and patient education. Overall, 33 (48%) of recommendations were accepted, 21 (30%) were not acknowledged, and 15 (22%) were declined. The most common outcome of accepted recommendations was a dose reduction with full taper planned by provider. The most common reasons for declined recommendations were (a) caregivers were educated and consented to continued treatment; (b) clinical presentation warranted continued treatment; (c) patient refused recommended changes; and (d) prescriber preferred to wait until next appointment to discuss with patient (Table 2).

Forty-nine recommendations were made to prescribers in the Psychiatry Department, 17 to prescribers in the Home-Based Primary Care (HBPC) Department, 15 to prescribers in the Primary Care Department, and 8 to prescribers in the Neurology Department. Prescribers in the Primary Care Department accepted recommendations at the highest rate (n = 13; 69%), while Neurology Department prescribers (n = 2; 33%) accepted recommendations at the lowest rate.

Discussion

This study illustrates the impact of including a psychiatric CPS as part of the interdisciplinary care team. Through the implementation of a PMR process, CPSs were able to provide specific, unbiased recommendations for the safe use of medications. It was felt that CPSs might have a greater impact by offering patient-specific recommendations rather than providing general information about the risks of these medications, which many providers are aware of already. Because nearly half of all recommendations were accepted, the authors feel that the PMR is an effective way to deliver provider education and improve safe prescribing practices.

There will be times when the use of these agents in at-risk populations is justified and appropriately documented, as was the case for 20 patients in this study. The goals of this study were not only to improve the use of evidence-based medications, but also the process of documenting justification for the continued use of these agents. The 22% of recommendations that were declined with justification from the provider were considered successful, because the PMR note prompted the provider to document in a note clear justification for the use of the agent in question.

The majority of recommendations were made to prescribers in the Mental Health Department, which was expected given the 2 classes of medications evaluated in the study. However, primary care prescribers accepted recommendations at the highest rate. There are several possible explanations. First, mental health prescribers are more likely to have complex, treatment-resistant psychiatric patients than do other disciplines. Additionally, these prescribers have an increased level of familiarity and comfort with second-generation antipsychotics and benzodiazepines and may have been more confident in documenting justifications to continue therapy.

Neurologists were the least likely to accept PMR recommendations. Unlike other services, prescribers in the Neurology Department spend a significant amount of their time providing care to patients at a university hospital and, therefore, are not present on the VA campus on a daily basis. This location disparity can lead to less frequent contact between prescriber and CPSs and may impact the professional relationship between these departments. Also, both the Neurology Department and the home-based Primary Care Department did not have staff actively involved in the PDSI, which may have decreased prescriber familiarity with the goals and intentions of PDSI and therefore decreased provider responsiveness to PMR notes.

Sometimes PMR notes were entered in the EMR when the patient did not have an upcoming appointment with the prescriber. As a result, there were instances when recommendations could not be implemented due to time and workload constraints. Many providers acknowledged the importance of shared medical decision making and preferred to wait to make medication adjustments until patients could be seen in the clinic.

Psychotropic medication review is a continually developing process, and these results illustrate provider response to the initial 5 months of a new service. During the time frame, PMR notes had been entered for all veterans identified as using antipsychotics or benzodiazepines in the setting of dementia but for only a fraction of those identified as using benzodiazepines who were aged > 75 years. It is reasonable to expect that as prescribers become more familiar with the PMR process and its intentions, they may be more likely to acknowledge recommendations and to respond with the appropriate documentation.

Psychotropic medication reviews were initiated as part of a PGY-2 psychiatric pharmacy residency project, and as such, the impact on the CPS workflow was not evaluated. Although this study suggests that the use of PMR was effective in improving evidence-based prescribing, it does not evaluate whether this process is sustainable in the long-term for the CPS.

Conclusions

The results of this study illustrate the value of a psychiatric CPS. Through the implementation of a simple PMR service, CPSs were able to impact evidence-based prescribing and related documentation. With nearly 50% of the recommendations accepted, the authors believe that use of the PMR is an effective way to deliver provider education and improve safe prescribing practices. Further review of the PMR process will be needed to evaluate the impact and sustainability on CPS workflow.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Information for healthcare professionals: conventional antipsychotics, 2013. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. http://www. fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124830.htm. Updated August 15, 2013. Accessed February 8, 2016.

2. Sprague K. CMS sets new goals for reducing use of antipsychotic medications. Consult Pharm. 2015;30(2):3.

3. Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD007726.

4. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

5. Billioti de Gage S, Moride Y, Ducruet T, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: case-control study. BMJ. 2014;349:g5205

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

Due to the ever-expanding pool of psychopharmacologic agents available to treat mental health conditions, prescribers need to be vigilant about ensuring appropriate medication selection, evaluation, and monitoring. In response to this need, the Office of Mental Health Operations, Mental Health Services, and Pharmacy Benefits Management Services launched the Psychotropic Drug Safety Initiative (PDSI) to improve evidence-based psychotropic prescribing habits within the VA. Considering the large geriatric population in the VA, PDSI was particularly concerned with benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications.

Background

The management of neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) for dementia is particularly burdensome to patients, caregivers, and prescribers. When nonpharmacologic interventions fail, patients are often prescribed antipsychotic medications to target these symptoms. The FDA has issued a black box warning regarding an increased risk of death associated with the use of both first- and second-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis.1 Due to these risks, tapering or discontinuing these medications should be considered at regular intervals.

Recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded its goal to reduce antipsychotic use in nursing facilities by 25% by the end of 2015 and 30% by the end of 2016.2 A review investigated the impact of withdrawal vs continuation of antipsychotic medications in the setting of Alzheimer dementia (AD) and found that antipsychotic medications could be withdrawn without detrimental effects on patient behaviors.3 However, the study also noted that those patients with severe NPS at baseline or who had a history of positive response to an antipsychotic might be at increased risk of relapse or have a shorter time to relapse when antipsychotic medications are withdrawn.

Benzodiazepines as a class may be used for many indications, including anxiety disorders, seizure disorders, sleep disorders, or muscle spasms. However, due to known risks of cognitive impairments, sedation, falls, or dependence and addiction, these agents are typically recommended for only short-term treatment. These risks are potentially amplified in a geriatric population, because elderly patients have an increased sensitivity to the effects of these agents and may have impaired hepatic or renal function, leading to accumulation.

Due to these risks, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) recommends against the use of any benzodiazepines for the treatment of insomnia, agitation, or delirium. Additionally, the AGS recommends that use of these agents for the treatment of behavioral problems related to dementia be reserved for those who have failed nonpharmacologic options and are at risk to themselves or others.4

Growing evidence suggests that benzodiazepine use may increase the risk of developing AD. A recent casecontrol study compare records of 1,796 patients with an AD diagnosis to 7,184 patients with no cognitive deficits. This study found that patients with a history of benzodiazepine use had a 51% increase in risk for AD. Additionally, use of long-acting benzodiazepines, such as diazepam and clonazepam, was strongly associated with the development of AD.5 These data further illustrate the importance of minimizing the use of benzodiazepines.

To ensure proper use of these 2 classes of medications, clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs) at the Lexington VAMC (LVAMC) in Kentucky began conducting psychotropic medication reviews (PMRs). Each PMR contained a brief summary of evidence-based recommendations (both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) and a clinical review of the patient’s medication history, including an evaluation of the appropriateness of current therapy and supportive documentation. Patients were candidates for PMR if they met one of the following criteria: (1) use of a benzodiazepine in a patient with dementia; (2) use of a benzodiazepine in a patient aged > 75 years; and (3) use of an antipsychotic in a patient with dementia. These criteria were selected based on guidance set forth by the PDSI. The figure provides a sample of the PMR template in the electronic medical record (EMR).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of a pharmacist-conducted PMR based on prescriber response to written recommendations. Additionally, this study characterized any observed differences in prescriber response based on discipline. The results of this study will be used to evaluate the efficacy of LVAMC’s current method of clinical pharmacy intervention and identify areas for process improvement. This study was reviewed and approved by the LVAMC institutional review board and research and development committee.

Methods

Patients were included in this study if they had a PMR note entered in the EMR between September 2014 and January 2015. Baseline demographic information collected included patient age and gender. One study author manually reviewed all PMR notes and collected the type of pharmacy intervention (characterized as recommendation for medication adjustment, patient education, both medication adjustment and patient education, or no recommendation), provider discipline, provider response to intervention, and any changes to medication therapy that occurred as a result of pharmacist intervention.

When patients were not cognitively able to receive education, family members or caretakers were educated. The primary outcome of this study was prescriber response to pharmacist recommendations, which was characterized as acknowledged, ignored, accepted, or declined with justification. In instances where both medication adjustment and patient education was recommended, the recommendation was considered to be accepted only if both components of the recommendation were addressed. The secondary outcome sought to identify any difference in provider response based on discipline.

Results

Eighty-nine patients were included in the study. Due to the nature of LVAMC, the patient population was fairly homogeneous, with an average patient age of 80 years (range 52-95 years); > 97% of patients were male. Fifty patients were noted to have prescriptions for benzodiazepines and were aged > 75 years, 11 patients had prescriptions for benzodiazepines and a diagnosis of dementia, and 38 patients had prescriptions for antipsychotics and a diagnosis of dementia. Several patients fell into more than one of the categories (Table 1).

Specific written recommendations were made for 69 (78%) patients, with 20 patients having appropriate documentation in the chart for therapy continuation. The most common documented reasons for continuation of therapy were (a) patient/caregiver educated and consent to continue therapy already documented; (b) recent dose reduction or discontinuation attempt failed; (c) recent successful dose reduction; or (d) documented risk to patient or others if medication were to be discontinued.

Most recommendations were for medication adjustments (n = 54; 78.3%). Six (8.7%) recommendations were for patient education only, and 9 (13%) recommendations were for both medication adjustment and patient education. Overall, 33 (48%) of recommendations were accepted, 21 (30%) were not acknowledged, and 15 (22%) were declined. The most common outcome of accepted recommendations was a dose reduction with full taper planned by provider. The most common reasons for declined recommendations were (a) caregivers were educated and consented to continued treatment; (b) clinical presentation warranted continued treatment; (c) patient refused recommended changes; and (d) prescriber preferred to wait until next appointment to discuss with patient (Table 2).

Forty-nine recommendations were made to prescribers in the Psychiatry Department, 17 to prescribers in the Home-Based Primary Care (HBPC) Department, 15 to prescribers in the Primary Care Department, and 8 to prescribers in the Neurology Department. Prescribers in the Primary Care Department accepted recommendations at the highest rate (n = 13; 69%), while Neurology Department prescribers (n = 2; 33%) accepted recommendations at the lowest rate.

Discussion

This study illustrates the impact of including a psychiatric CPS as part of the interdisciplinary care team. Through the implementation of a PMR process, CPSs were able to provide specific, unbiased recommendations for the safe use of medications. It was felt that CPSs might have a greater impact by offering patient-specific recommendations rather than providing general information about the risks of these medications, which many providers are aware of already. Because nearly half of all recommendations were accepted, the authors feel that the PMR is an effective way to deliver provider education and improve safe prescribing practices.

There will be times when the use of these agents in at-risk populations is justified and appropriately documented, as was the case for 20 patients in this study. The goals of this study were not only to improve the use of evidence-based medications, but also the process of documenting justification for the continued use of these agents. The 22% of recommendations that were declined with justification from the provider were considered successful, because the PMR note prompted the provider to document in a note clear justification for the use of the agent in question.

The majority of recommendations were made to prescribers in the Mental Health Department, which was expected given the 2 classes of medications evaluated in the study. However, primary care prescribers accepted recommendations at the highest rate. There are several possible explanations. First, mental health prescribers are more likely to have complex, treatment-resistant psychiatric patients than do other disciplines. Additionally, these prescribers have an increased level of familiarity and comfort with second-generation antipsychotics and benzodiazepines and may have been more confident in documenting justifications to continue therapy.

Neurologists were the least likely to accept PMR recommendations. Unlike other services, prescribers in the Neurology Department spend a significant amount of their time providing care to patients at a university hospital and, therefore, are not present on the VA campus on a daily basis. This location disparity can lead to less frequent contact between prescriber and CPSs and may impact the professional relationship between these departments. Also, both the Neurology Department and the home-based Primary Care Department did not have staff actively involved in the PDSI, which may have decreased prescriber familiarity with the goals and intentions of PDSI and therefore decreased provider responsiveness to PMR notes.

Sometimes PMR notes were entered in the EMR when the patient did not have an upcoming appointment with the prescriber. As a result, there were instances when recommendations could not be implemented due to time and workload constraints. Many providers acknowledged the importance of shared medical decision making and preferred to wait to make medication adjustments until patients could be seen in the clinic.

Psychotropic medication review is a continually developing process, and these results illustrate provider response to the initial 5 months of a new service. During the time frame, PMR notes had been entered for all veterans identified as using antipsychotics or benzodiazepines in the setting of dementia but for only a fraction of those identified as using benzodiazepines who were aged > 75 years. It is reasonable to expect that as prescribers become more familiar with the PMR process and its intentions, they may be more likely to acknowledge recommendations and to respond with the appropriate documentation.

Psychotropic medication reviews were initiated as part of a PGY-2 psychiatric pharmacy residency project, and as such, the impact on the CPS workflow was not evaluated. Although this study suggests that the use of PMR was effective in improving evidence-based prescribing, it does not evaluate whether this process is sustainable in the long-term for the CPS.

Conclusions

The results of this study illustrate the value of a psychiatric CPS. Through the implementation of a simple PMR service, CPSs were able to impact evidence-based prescribing and related documentation. With nearly 50% of the recommendations accepted, the authors believe that use of the PMR is an effective way to deliver provider education and improve safe prescribing practices. Further review of the PMR process will be needed to evaluate the impact and sustainability on CPS workflow.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Due to the ever-expanding pool of psychopharmacologic agents available to treat mental health conditions, prescribers need to be vigilant about ensuring appropriate medication selection, evaluation, and monitoring. In response to this need, the Office of Mental Health Operations, Mental Health Services, and Pharmacy Benefits Management Services launched the Psychotropic Drug Safety Initiative (PDSI) to improve evidence-based psychotropic prescribing habits within the VA. Considering the large geriatric population in the VA, PDSI was particularly concerned with benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications.

Background

The management of neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) for dementia is particularly burdensome to patients, caregivers, and prescribers. When nonpharmacologic interventions fail, patients are often prescribed antipsychotic medications to target these symptoms. The FDA has issued a black box warning regarding an increased risk of death associated with the use of both first- and second-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis.1 Due to these risks, tapering or discontinuing these medications should be considered at regular intervals.

Recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded its goal to reduce antipsychotic use in nursing facilities by 25% by the end of 2015 and 30% by the end of 2016.2 A review investigated the impact of withdrawal vs continuation of antipsychotic medications in the setting of Alzheimer dementia (AD) and found that antipsychotic medications could be withdrawn without detrimental effects on patient behaviors.3 However, the study also noted that those patients with severe NPS at baseline or who had a history of positive response to an antipsychotic might be at increased risk of relapse or have a shorter time to relapse when antipsychotic medications are withdrawn.

Benzodiazepines as a class may be used for many indications, including anxiety disorders, seizure disorders, sleep disorders, or muscle spasms. However, due to known risks of cognitive impairments, sedation, falls, or dependence and addiction, these agents are typically recommended for only short-term treatment. These risks are potentially amplified in a geriatric population, because elderly patients have an increased sensitivity to the effects of these agents and may have impaired hepatic or renal function, leading to accumulation.

Due to these risks, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) recommends against the use of any benzodiazepines for the treatment of insomnia, agitation, or delirium. Additionally, the AGS recommends that use of these agents for the treatment of behavioral problems related to dementia be reserved for those who have failed nonpharmacologic options and are at risk to themselves or others.4

Growing evidence suggests that benzodiazepine use may increase the risk of developing AD. A recent casecontrol study compare records of 1,796 patients with an AD diagnosis to 7,184 patients with no cognitive deficits. This study found that patients with a history of benzodiazepine use had a 51% increase in risk for AD. Additionally, use of long-acting benzodiazepines, such as diazepam and clonazepam, was strongly associated with the development of AD.5 These data further illustrate the importance of minimizing the use of benzodiazepines.

To ensure proper use of these 2 classes of medications, clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs) at the Lexington VAMC (LVAMC) in Kentucky began conducting psychotropic medication reviews (PMRs). Each PMR contained a brief summary of evidence-based recommendations (both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) and a clinical review of the patient’s medication history, including an evaluation of the appropriateness of current therapy and supportive documentation. Patients were candidates for PMR if they met one of the following criteria: (1) use of a benzodiazepine in a patient with dementia; (2) use of a benzodiazepine in a patient aged > 75 years; and (3) use of an antipsychotic in a patient with dementia. These criteria were selected based on guidance set forth by the PDSI. The figure provides a sample of the PMR template in the electronic medical record (EMR).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of a pharmacist-conducted PMR based on prescriber response to written recommendations. Additionally, this study characterized any observed differences in prescriber response based on discipline. The results of this study will be used to evaluate the efficacy of LVAMC’s current method of clinical pharmacy intervention and identify areas for process improvement. This study was reviewed and approved by the LVAMC institutional review board and research and development committee.

Methods

Patients were included in this study if they had a PMR note entered in the EMR between September 2014 and January 2015. Baseline demographic information collected included patient age and gender. One study author manually reviewed all PMR notes and collected the type of pharmacy intervention (characterized as recommendation for medication adjustment, patient education, both medication adjustment and patient education, or no recommendation), provider discipline, provider response to intervention, and any changes to medication therapy that occurred as a result of pharmacist intervention.

When patients were not cognitively able to receive education, family members or caretakers were educated. The primary outcome of this study was prescriber response to pharmacist recommendations, which was characterized as acknowledged, ignored, accepted, or declined with justification. In instances where both medication adjustment and patient education was recommended, the recommendation was considered to be accepted only if both components of the recommendation were addressed. The secondary outcome sought to identify any difference in provider response based on discipline.

Results

Eighty-nine patients were included in the study. Due to the nature of LVAMC, the patient population was fairly homogeneous, with an average patient age of 80 years (range 52-95 years); > 97% of patients were male. Fifty patients were noted to have prescriptions for benzodiazepines and were aged > 75 years, 11 patients had prescriptions for benzodiazepines and a diagnosis of dementia, and 38 patients had prescriptions for antipsychotics and a diagnosis of dementia. Several patients fell into more than one of the categories (Table 1).

Specific written recommendations were made for 69 (78%) patients, with 20 patients having appropriate documentation in the chart for therapy continuation. The most common documented reasons for continuation of therapy were (a) patient/caregiver educated and consent to continue therapy already documented; (b) recent dose reduction or discontinuation attempt failed; (c) recent successful dose reduction; or (d) documented risk to patient or others if medication were to be discontinued.

Most recommendations were for medication adjustments (n = 54; 78.3%). Six (8.7%) recommendations were for patient education only, and 9 (13%) recommendations were for both medication adjustment and patient education. Overall, 33 (48%) of recommendations were accepted, 21 (30%) were not acknowledged, and 15 (22%) were declined. The most common outcome of accepted recommendations was a dose reduction with full taper planned by provider. The most common reasons for declined recommendations were (a) caregivers were educated and consented to continued treatment; (b) clinical presentation warranted continued treatment; (c) patient refused recommended changes; and (d) prescriber preferred to wait until next appointment to discuss with patient (Table 2).

Forty-nine recommendations were made to prescribers in the Psychiatry Department, 17 to prescribers in the Home-Based Primary Care (HBPC) Department, 15 to prescribers in the Primary Care Department, and 8 to prescribers in the Neurology Department. Prescribers in the Primary Care Department accepted recommendations at the highest rate (n = 13; 69%), while Neurology Department prescribers (n = 2; 33%) accepted recommendations at the lowest rate.

Discussion

This study illustrates the impact of including a psychiatric CPS as part of the interdisciplinary care team. Through the implementation of a PMR process, CPSs were able to provide specific, unbiased recommendations for the safe use of medications. It was felt that CPSs might have a greater impact by offering patient-specific recommendations rather than providing general information about the risks of these medications, which many providers are aware of already. Because nearly half of all recommendations were accepted, the authors feel that the PMR is an effective way to deliver provider education and improve safe prescribing practices.

There will be times when the use of these agents in at-risk populations is justified and appropriately documented, as was the case for 20 patients in this study. The goals of this study were not only to improve the use of evidence-based medications, but also the process of documenting justification for the continued use of these agents. The 22% of recommendations that were declined with justification from the provider were considered successful, because the PMR note prompted the provider to document in a note clear justification for the use of the agent in question.

The majority of recommendations were made to prescribers in the Mental Health Department, which was expected given the 2 classes of medications evaluated in the study. However, primary care prescribers accepted recommendations at the highest rate. There are several possible explanations. First, mental health prescribers are more likely to have complex, treatment-resistant psychiatric patients than do other disciplines. Additionally, these prescribers have an increased level of familiarity and comfort with second-generation antipsychotics and benzodiazepines and may have been more confident in documenting justifications to continue therapy.

Neurologists were the least likely to accept PMR recommendations. Unlike other services, prescribers in the Neurology Department spend a significant amount of their time providing care to patients at a university hospital and, therefore, are not present on the VA campus on a daily basis. This location disparity can lead to less frequent contact between prescriber and CPSs and may impact the professional relationship between these departments. Also, both the Neurology Department and the home-based Primary Care Department did not have staff actively involved in the PDSI, which may have decreased prescriber familiarity with the goals and intentions of PDSI and therefore decreased provider responsiveness to PMR notes.

Sometimes PMR notes were entered in the EMR when the patient did not have an upcoming appointment with the prescriber. As a result, there were instances when recommendations could not be implemented due to time and workload constraints. Many providers acknowledged the importance of shared medical decision making and preferred to wait to make medication adjustments until patients could be seen in the clinic.

Psychotropic medication review is a continually developing process, and these results illustrate provider response to the initial 5 months of a new service. During the time frame, PMR notes had been entered for all veterans identified as using antipsychotics or benzodiazepines in the setting of dementia but for only a fraction of those identified as using benzodiazepines who were aged > 75 years. It is reasonable to expect that as prescribers become more familiar with the PMR process and its intentions, they may be more likely to acknowledge recommendations and to respond with the appropriate documentation.

Psychotropic medication reviews were initiated as part of a PGY-2 psychiatric pharmacy residency project, and as such, the impact on the CPS workflow was not evaluated. Although this study suggests that the use of PMR was effective in improving evidence-based prescribing, it does not evaluate whether this process is sustainable in the long-term for the CPS.

Conclusions

The results of this study illustrate the value of a psychiatric CPS. Through the implementation of a simple PMR service, CPSs were able to impact evidence-based prescribing and related documentation. With nearly 50% of the recommendations accepted, the authors believe that use of the PMR is an effective way to deliver provider education and improve safe prescribing practices. Further review of the PMR process will be needed to evaluate the impact and sustainability on CPS workflow.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Information for healthcare professionals: conventional antipsychotics, 2013. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. http://www. fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124830.htm. Updated August 15, 2013. Accessed February 8, 2016.

2. Sprague K. CMS sets new goals for reducing use of antipsychotic medications. Consult Pharm. 2015;30(2):3.

3. Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD007726.

4. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

5. Billioti de Gage S, Moride Y, Ducruet T, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: case-control study. BMJ. 2014;349:g5205

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Information for healthcare professionals: conventional antipsychotics, 2013. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. http://www. fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124830.htm. Updated August 15, 2013. Accessed February 8, 2016.

2. Sprague K. CMS sets new goals for reducing use of antipsychotic medications. Consult Pharm. 2015;30(2):3.

3. Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD007726.

4. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

5. Billioti de Gage S, Moride Y, Ducruet T, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: case-control study. BMJ. 2014;349:g5205

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.